Abstract

Heterotopic ossification (HO), the pathological extraskeletal formation of bone, can arise from blast injuries, severe burns, orthopedic procedures and gain-of-function mutations in a component of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway, the ACVR1/ALK2 receptor serine-threonine (protein) kinase, causative of Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP). All three ALKs (−2, −3, −6) that play roles in bone morphogenesis contribute to trauma-induced HO, hence are well-validated pharmacological targets. That said, development of inhibitors, typically competitors of ATP binding, is inherently difficult due to the conserved nature of the active site of the 500+ human protein kinases. Since these enzymes are regulated via inherent plasticity, pharmacological chaperone-like drugs binding to another (allosteric) site could hypothetically modulate kinase conformation and activity. To test for such a mechanism, a surface pocket of ALK2 kinase formed largely by a key allosteric substructure was targeted by supercomputer docking of drug-like compounds from a virtual library. Subsequently, the effects of docked hits were further screened in vitro with purified recombinant kinase protein. A family of compounds with terminal hydrogen-bonding acceptor groups was identified that significantly destabilized the protein, abolishing activity. Destabilization was pH-dependent, putatively mediated by ionization of a histidine within the allosteric substructure with decreasing pH. In vivo, nonnative proteins are degraded by proteolysis in the proteasome complex, or cellular trashcan, allowing for the emergence of therapeutics that inhibit through degradation of over-active proteins implicated in the pathology of diseases and disorders. Because HO is triggered by soft-tissue trauma and ensuing hypoxia, dependency of ALK destabilization on hypoxic pH imparts selective efficacy on the allosteric inhibitors, providing potential for safe prophylactic use.

Keywords: bone morphogenetic protein, BMP, protein kinase, allosteric, R-spine, αC-β4 loop, ACVR1, ALK2, FKBP12, BMPRII, heterotopic ossification, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, FOP, hypoxia, hypoxic pH, pharmacological chaperone, selective degrader, hydrophobic tagging, PROTACs, macrocyclic inhibitor, covalent inhibitor, kinase inhibitor

Graphical Abstract

1. Executive Summary

1.1. Background

Although structurally similar to type II counterparts, type I or activin receptor-like kinases (ALKs) are set apart by a metastable 30 amino acid helix-loop-helix (HLH) element preceding the protein kinase domain that regulates phosphorylation by altering the enzyme active site. Hence, the proteins are inherently plastic and amenable to modulation, hypothetically with stabilizing and inhibitory pharmacological chaperone-like drugs. Because protein kinases are numerous (500+) and bind ATP•Mg2+ similarly, molecules targeting sites other than the substrate-binding pocket, i.e., allosterically acting compounds, have gained attention as innovative therapeutic alternatives that are not constrained by the limitations inherent to typical ATP-competitive inhibitors, such as, for example, the AMPK and ALK inhibitor, Compound C, also known as dorsomorphin.

1.2. Results and Discussion

To test the alternative mechanism of inhibition, we targeted an ALK2 pocket formed largely by the αC-β4 loop, a key allosteric switch, through an in silico screen and tested a subset of docked compounds for inhibitory activity due to stabilization and diminished plasticity. Unexpectedly, related compounds were found that destabilized, and consequently, inhibited the enzyme, as shown by native PAGE, differential scanning fluorimetry (thermofluor) and SDS-PAGE/[γ−33P]ATP autoradiography. Two ALK2-binding partners, BMPRII and FKBP12, were resistant to destabilization, ruling against a nonspecific mechanism. Based on reliable docked poses at the targeted site, the destabilizing interaction appeared to be composed of the side chain of a single residue (Arg258) - with five H-bond donors - and terminal protophilic H-bond acceptors (“warheads”) of related hits. Destabilization was pH-dependent, putatively mediated by interaction of the ionized imidazole side chain of an ALK-specific histidine with the main chain at αC-β4, inducing distortion of the loop, and the Arg258 side chain, with decreasing pH.

1.3. Significance

Therapeutics that inhibit through degradation of over-active proteins implicated in the pathology of diseases and disorders have proven to be pharmacologically efficacious and lucrative or shown tremendous potential (e.g. Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders, SERDs; Proteolysis-targeting Chimeras, PROTACs). The initial stage preclinical studies reported here signal the addition of a newly identified category of degraders (Hypoxia-Selective ALK Allosteric Destabilizers/Degraders, H-SAAD/Ds). Importantly, because HO disorders are triggered by trauma to, and hypoxia in, soft tissues, the dependency of ALK destabilization on hypoxic pH serendipitously endows the family of preclinical compounds with selective efficacy, potentially allowing for prophylactic drugs that could be safely administered long-term or lifelong.

2. Introduction

2.1. Trauma to soft tissue can lead to heterotopic endochondral ossification

Heterotopic ossification (HO), the pathological extraskeletal formation of bone, can arise from blast injuries, severe burns, orthopedic procedures [1–7] and gain-of-function (G-O-F) mutations in a component of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway, the ACVR1/ALK2 receptor serine-threonine kinase, causative of Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva (FOP) [8–11]. In the prevailing view for all cases, soft tissue such as muscle (skeletal) and connective tissue (ligaments, tendons) become mineralized through proliferation of mesenchymal-like stem or connective tissue progenitor cells, which undergo differentiation and eventual condensation to morph into cartilaginous tissue that ossifies (endochondral ossification). In the first three cases, and frequently in FOP, trauma to soft tissues triggers the process [1, 12].

2.2. Trauma to soft tissue results in hypoxia, requisite for HO that lowers intracellular pH

At sites of trauma in soft tissues, vasculature is damaged and/or immune cells infiltrate and proliferate, resulting in reduced supply and/or increased consumption of molecular oxygen,1 the final acceptor of electrons harvested during aerobic respiration for synthesis of ATP. As a result, the tissue and cells become hypoxic, requiring upregulation of anaerobic energy production via glycolysis, which due to elevated steady-state levels of lactic acid as an electron repository, lowers the intracellular pH (pHi). A newly developed biophysical method for measuring the effect of hypoxia on pHi in pathophysiological studies showed that under increasingly hypoxic conditions (15 to 1% O2), pHi decreased from 7.1 to 6.5 [13].

Interestingly, hypoxia is not simply a side effect of soft tissue trauma, but is a requisite condition for endochondral bone formation, in acquired or genetic HO, as well as the non-traumatic, non-pathological process [14–16]. A cascade of cellular responses to low oxygen levels is set off by stabilization of a master regulator, a hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (Hif1α/HIF1α), that otherwise is marked for degradation in proteasomes due to polyubiquitylation [17]. Amongst the induced responses are (1) increased expression of glucose transporters and glycolytic enzymes [18], plus a negative regulator of oxidative degradation of pyruvate [19], and (2) stimulation of BMP signaling, which appears to play a principle role in normal and heterotopic endochondral bone formation [20]; [21], this issue.

In keeping with the metabolic shifts arising from trauma and further induced by responses to hypoxia, glucose (18F-radiolabelled) uptake was increased at sites of heterotopic bone formation in an FOP patient as shown by positron emission tomography (PET) scans [22]. By means of combined [18F]NaF PET/CT scans with the radionuclide ion alone (not 18F-glucose), high uptake was detected in muscle after three weeks in the section of a soft tissue “flare-up” that eventually formed bone [23], this issue. Given the fundamental role of cellular hypoxia in HO, scanning for metabolically perturbed soft tissue with radiolabelled glucose in flare-ups and/or after trauma might allow for diagnostic or investigative detection of earlier pre-osseous stages of genetic and acquired HO.

Because Hif1α/HIF1α levels are dramatically stabilized in both acquired and genetic HO lesions [20, 24], the cytoplasm of the cells must be hypoxic, at minimum during the initial stages following trauma to soft tissues. In tumors, due to hypoxia-induced expression of a monocarboxylate transporter that lowers the steady-state concentration of lactic acid, the pHi is restored to neutrality, whereas the pHe (extracellular pH) becomes acidic (tissue acidosis) [25]. Nevertheless, the pHi of Hif1α/HIF1α-expressing cells in HO lesions are at least transiently hypoxic, potentially as low as 6.5 [13].

2.3. Development of therapeutics for HO: manifold approaches, promise for patients

2.3.1. Strategies and targets based on hypoxia-selectivity

Consistent with the indispensible role of hypoxia in HO, inhibitors of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (e.g. PX-478) block hypoxia-induced mesenchymal condensation in three separate mouse models of injury-induced and/or genetic HO [24] and BMP signaling in cultured cells [20]. Because HO formation in animal models is also significantly reduced [20, 24], inhibition of HIF1α might serve as a means of therapeutic intervention. A related approach stems from the hypoxia-induced inflammatory response, which includes infiltration of mast cells and macrophages that combined contribute substantially to HO (~ 75% reduction upon genetic depletion) [26]. Chemical intervention with cromolyn, an anti-inflammatory, effectively stabilizes mast cells in pre-osseous lesions and dramatically reduces HO in an injury-induced mouse model of FOP [27], this issue.

Hypoxia has been exploited as a means of selectively targeting transformed cells in tumors, which like cells in HO lesions, undergo a metabolic shift from mitochondrial glucose oxidation to cytoplasmic glycolysis, known as the Warburg effect [28, 29]. Similar to HO lesions, glucose uptake by tumors is highly elevated relative to neighboring non-cancerous tissues as shown by PET scans with radiolabelled glucose [30]. The shift in metabolic profile provides a way of selectively targeting cancer cells, unlike traditional oncology drugs that target processes shared with non-transformed cells as well. Because the Warburg effect shifts the metabolic balance of transformed cells from catabolic (glucose-oxidizing) and non-proliferative, to anabolic (pentose for nucleic acids, lipids for membranes) and proliferative, components of dysregulated metabolic pathways can be selectively targeted [31].

In cancer cells, hypoxic upregulation of components of metabolic pathways (cf. 1.2) coordinately slows the normoxic flux of pyruvate toward oxidative decarboxylation in the mitochondrial matrix, resulting in increased rates of the anabolic cytoplasmic routes driving proliferation [31–35]. The master gatekeeper is a large machine-like complex, pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which links glycolysis to the tricarboxylic acid cycle and is negatively regulated via phosphorylation by a specific kinase, PDK1. Gain or loss of function of PDK1 in melanocytes and mice showed that PDH-mediated alteration of pyruvate flux could induce or suppress transformation and melanoma initiation, respectively. Hence, small molecule kinase inhibitors (SMKIs) of PDK1 currently under development for cancer patients might selectively serve as off-label inhibitors of HO.2 [36–38]. As proof of concept for both the use of hypoxia-selective and off-label repurposed drugs for HO, the SMKI imatinib, which inhibited HO in a mouse model [20] ostensibly through an array of off-targets involved in the hypoxic and inflammatory stages of the process, anecdotally decreased the intensity of flare-ups and was well-tolerated in each of the six children who took the drug [39], this issue.

2.3.2. Other strategies and targets: two clinical trials, one widespread pre-clinical effort

The majority of therapeutic avenues conceived to date have not been based on the central role of cellular hypoxia in HO. Two related examples are anti-sense [40] and mutant-specific small inhibitory [41, 42] RNAs to knockdown levels of ACVR1 transcripts. Whether either of the two molecular genetic strategies successfully emerges from preclinical evaluation for HO remains to be determined.

However, of the ever-expanding repertoire of pharmacologic (small molecule, biologic) approaches currently under development, two have advanced into clinical trials and one is vigorously pursued worldwide, warranting hope for severe trauma, surgical and FOP patients. The three main approaches, ranked in pipeline positions, are: (1) a retinoic acid receptor (RAR-γ) agonist, palovarotene (orphan drug status, Phase III, Clementia), which appears to revert induced mesenchymal stem cells [43–45]; [46], this issue, (2) a humanized, neutralizing monoclonal antibody against activin A (orphan drug status, Phase II, Regeneron), the non-canonical ligand responsible for gain-of-function BMP signal transduction through the FOP mutant receptor kinase [47–49]; [50], this issue and (3) an increasingly diverse palette of small molecule, steric inhibitors of the kinase that compete for binding the ATP•Mg2+ complex substrate within a broad, deep and narrow cleft between the two large lobes of the enzyme (cf. Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1. Surface pocket targeted by virtual screening of drug-like compound library.

(A) View of the targeted pocket of the αC-β4 loop in the N-lobe of ALK2. (B) Side-by-side view of targeted pocket and active site cleft, the binding site for the ATP•Mg2+ complex and steric (competitive) inhibitors such as dorsomorphin (DM). (C) Zoomed view of pocket with C28 docked. Dashed lines represent five potential H-bonds between the donor guanidino group of the Arg258 side chain and the sp2-hybridized nitrogen acceptor of the heterocyclic aminopyridine ring or “warhead” of C28. (D) Further zoomed and slightly tilted view to highlight the proposed role of Arg258 in destabilization of the kinase. (E) Interface of the FKBP12:ALK2 complex (crystal structure; PDB ID 3H9R). Note lack of direct interactions with or proximity to the compound. (F) Interface of the BMPRII:ALK2 complex (predicted by computational docking) adjacent to the Arg258 reside and flanking main chain, approximately one-half of the αC-β4 loop.

ALK-specific or -selective SMKIs with varying degrees of subtype selectivity (e.g. ALK2 vs. ALK1, ALK3, ALK6) remain at a range of preclinical stages in academic (Harvard, Vanderbilt), NIH (NCATS/TRND-FOP), consortium (SGC Oxford) and small biotech-pharma (La Jolla Pharmaceuticals, Blueprint Medicines) laboratories [51–59]; [60], this issue. Of note, a therapeutic in clinical development by Gilead Sciences for a blood cancer (momelotinib) is a potent inhibitor of the target Janus kinases (JAK1/2), as well as the off-target ALK2 kinase, which mediates hepatic expression of hepcidin, the main iron-regulatory hormone that acts to sequester iron stores from the plasma, suppressing erythropoiesis [61, 62]. Ironically, based on the promise shown by imatinib with a small cohort of FOP patients (cf. 1.3.1), the first SMKI ever approved (2001) might also be the first entering clinical trials for inhibition of HO, despite nearly a decade of intense screening, co-crystallization, SARS-based rational design and synthesis of small molecules worldwide.

2.4. Small molecule inhibitors of protein kinases: steric and allosteric

SMKIs have constituted a major sector of drug development by the pharmaceutical industry for decades. With few exceptions, the lead compounds are competitive inhibitors that target the ATP•Mg2+ binding cleft of protein kinases (types I, I-1/2, II; active site loop-helix conformations). However, given the number (500+ in kinome) [63], the conserved structure of the complex binding site and the high steady-state concentration of ATP•Mg2+ in cells (~ 5 mM), disproportionately few inhibitors have reached clinics and progressed through clinical trials relative to the substantial investment of time, money and effort. Less than thirty SMKIs have been FDA-approved, predominantly anti-cancer drugs targeting tyrosine kinases [64, 65]. As chemotherapeutics, all too many have serious side effects, hence cannot be administered over prolonged periods. Similar concerns are relevant for HO, in particular FOP, which ideally should be treated prophylactically but, due to drawbacks, would likely be limited to use during sporadic flare-ups. Daily dosing, to balance trade-offs and dampen swings between efficacy and off-target toxicity, is an unknown that might mirror that of cancer chemotherapeutics.

As a result of the inherent obstacles, small molecules that interact at sites other than the ATP•Mg2+ substrate-binding pocket, classified as allosteric inhibitors, have gained increasing attention as innovative alternatives that are not constrained by the limitations inherent to typical competitive inhibitors of protein kinases [66–68]. That said, in contrast to the plethora of endogenous regulators of metabolic enzymes, that bind at sites distinct from those of substrates, most allosteric inhibitors of protein kinases impart additional specificity or selectivity by interacting with small pockets on the periphery of the substrate binding cleft (type III), not with well-separated, distant sites (type IV) [69].

2.5. Hypothetical allosteric regulation by small molecules: inhibition through stabilization

Despite ongoing exploration of manifold avenues of intervention (cf. 2.3.1, 2.3.2) and reason for cautious optimism, pursuit of alternative approaches for inhibition of heterotopic ossification that are safe, efficacious and perhaps complementary (cf. 5.10, below) remains worthwhile. In addition, of particular benefit worldwide and well into the future, treatments should be neither cost-prohibitive nor perishable, that is requiring special storage and handling. Furthermore, in the case of many patients presenting with HO, a therapeutic must be administered long-term (severe trauma) or even lifelong as a prophylactic (FOP).

2.5.1. Initial paradigm of passive HLH-regulation of ALKs failed to offer insight into G-O-F

Thus we have been exploring an independent avenue with potential to meet the therapeutic criteria, foremost prophylaxis, over the last five years. Following the identification of the component of the BMP signaling pathway mutated in FOP, ACVR1/ALK2 [8], a druggable and validated target [51], we meticulously dissected the structural-functional basis for the gain-of-function of R206H ALK2 [11, 70–73]. Based on early studies with ALK5, the TGFβ type I receptor kinase, enzymatic activity of activin receptor-like kinases was postulated to be regulated through intrinsic conformational plasticity, however passively by the HLH-regulatory element due to protein-protein interaction or covalent modification [74–76]. The results of our subsequent studies with ALK2 kinase forms were inconsistent with the “inhibitor- to substrate-binding switch” hypothesis, which thus failed to provide insight into the structural-functional basis for the R206H gain-of-function mutation.

2.5.2. Subsequent more sophisticated mechanistic model: conserved, dynamic ”spines”

In contrast, our findings with the FOP mutant kinase were in keeping with seminal studies of the role of allostery in the regulation of protein kinases by Susan Taylor and coworkers, who not only determined the first protein kinase crystal structure [77–79], but also developed the concept of dynamic “spines” or ensembles of hydrophobic core elements of the structurally conserved family, a more sophisticated model than the longstanding, initial paradigm of two large, rigid-body lobes (N- and C-) joined by an ADP/ATP-exchanging hinge segment that was based on sequence alignments and static crystal structures which focused on relatively large changes in conformation [80–86].

The new paradigm for mechanisms of activation via allostery championed by Taylor et al. provided a more nuanced context for interpretation of the structural-functional consequences of mutation and variation. Thus after a rigorous and systematic process of elimination of aspects of the early ALK5-based, passive HLH-switch hypothesis and with the foundation of the later dynamic spine model, we reached the firm conclusion that FOP is an allosteric disorder, as are other pathologies [87]. A recent molecular dynamics study of mutant, variant, phosphorylated and complexed forms of the ALK2 kinase derived from a crystal structure provides support for, and calculated structural aspects of, our proposed fundamental role of allostery in FOP [88].

2.5.3. Polypeptide Substrate Accessibility Hypothesis and Pharmacological Chaperones

More specifically, based on the sum of our in vitro findings with recombinant ALK2 kinase, we concluded that perturbation of a structural element remote from the active site leads to promiscuous polypeptide substrate (BMP R-Smad) phosphorylation via aberrant conformational change. Our Polypeptide Substrate Accessibility (PSA) hypothesis further suggests that ALK receptor kinases are potential targets for restriction of conformational change, and concomitant inhibition of pathology-inducing phosphoryl group transfer, through small molecule stabilization mediated at sites other than the ATP-binding cleft or periphery.3

The broad concept, which evolved from our studies of ALK2 kinase gain-of-function mutants and variants that alter enzyme activity, has been well established for a host of proteins with loss-of-function mutations that alter folding and stability. “Pharmacological chaperones” or PCs are proteostatic modulators that, in nearly all medically relevant cases, stabilize mutant proteins that otherwise misfold and degrade or aggregate, e.g. in lysosomal storage disorders [89–92]. Note that PCs in at least one case can either stabilize or destabilize, depending on preference for interaction with native or non-native states of proteins [93].

2.5.4. Targeting the αC-β4 loop: a key stabilizing, allosteric hub linking the N- and C-lobes

To test our allosteric-PC therapeutic hypothesis, we conducted an in silico screen of a virtual library of over 640,000 small, drug-like molecules targeting a ring-like pocket flanking the regulatory HLH element in a crystal structure of ALK2 (Fig. 1A). The pocket is predominantly formed by the geometrically conserved αC-β4 loop that: (1) contains a hydrophobic residue which plays an important role in stabilizing the R-spine, (2) acts as a key allosteric communication hub relaying signals between the R-spine of the N-lobe, the ATP binding cleft and the C-lobe, and (3) is firmly anchored to the large α-helical C-lobe through a hydrogen bond linking the main chain of the loop to the side chain hydroxyl of a tyrosine common to all eukaryotic protein kinases (see review by Kornev and Taylor [82], with the exception of the activin receptor-like kinases. Intriguingly, ALKs are substituted with a histidine, the only amino acid to ionize at hypoxic pH, which could putatively induce formation of a unique, pH-dependent αC-β4 loop interaction and concomitant conformational change.

After visual evaluation of the in silico-docked poses of the calculated top 1000 interacting compounds, iteratively selected subsets of the commercially available hits and analogs were screened in vitro by orthogonal assays for effects of the small molecules on the stability and activity of recombinant ALK2 kinase protein.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. In silico screen

Two in silico screens targeting the αC-β4 loop pocket, bordered by the helix-loop-helix regulatory subdomain and opposite the ATP-binding active site cleft of ALK2 (cf. Fig. 1), were performed through a web-resource that provided controlled access to molecular docking software running on a supercomputer (Lonestar) at TACC (Texas Advanced Computing Center, University of Texas at Austin). The docking portal, originally developed by a team of researchers lead by Dr. Stanley Watowich, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston, was subsequently ported to TACC. Of the two screens performed, the principle database, the so-called “large ZINC library” of 642,759 commercially available, uncharged Lipinski rule-of-five (ROF) molecules [94], provided significantly more promising apparent hits relative to the small version. The large library is a custom subset of the ZINC database [95], filtered to contain only “clean” drug-like compounds from reliable vendors (ChemBridge, ChemDiv, Ryan Scientific, Maybridge, Sigma-Aldrich) that was generated by Dr. John Irwin (UCSF) specifically for the portal, which runs the routines of the docking software, Autodock Vina [96]. Due to upgrades at TACC, the large library can be screened against a target protein in around 6 – 12 hours, as opposed to approximately 35 hours previously. The highest scoring thousand molecules from the database were returned with docked poses (PDB file format) and calculated free energies of binding in a descending list as a test file with ZINC ID numbers.

3.2. Commercially available screening compounds

The ten docked hits selected for the initial proof-of-concept in vitro screens were purchased as 1 mg lyophilized aliquots from a single shared vendor (ChemBridge, La Jolla, CA; Moscow, Russia) listed on the ten individual ZINC database webpages and solubilized in 100% DMSO as 10 mM stocks. Compounds for the subsequent mechanism-based screen were purchased from MolPort (Riga, Latvia) and initially solubilized in 100% DMSO as 10 mM stocks. C14, C24 and the analogs for the small SAR study were from Mcule (Palo Alto, CA; Budapest, Hungary) and re-dissolved with three molar equivalents of NaOH (aqueous solutions) as 50 mM stocks of their sodium salts. For reanalysis of C28, the aminopyridine was re-dissolved in one molar equivalent of HCl (aqueous solution) as a 10 mM stock of the hydrochloride salt of the compound.

3.3. Recombinant proteins and Smad-surrogate substrate

ALK2 kinase was expressed in insect cells from a synthetic cDNA (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) and purified to near homogeneity as previously described [70]. FKBP12 was expressed in E. coli as a charge variant with a negative pI engineered through modification of a flexible N-terminal affinity tag (6xHis-TEV) that did not affect ALK2 binding but allowed for analyses by native PAGE [70]. BMPRII was expressed in E. coli as a SUMO fusion protein (8xHis-SUMO-TEV) from a synthetic cDNA and purified to near homogeneity from a cleared lysate (containing a soluble fraction of recombinant protein) by forward and reverse nickel affinity chromatography followed by S-75 size exclusion chromatography. Smad-surrogate substrates for kinase activity assays by autoradiography were partially dephosphorylated casein polypeptides purchased from SignalChem (Richmond, BC) exclusively. The unstable mixtures of intrinsically disordered proteins were divided into small aliquots and frozen for moderate durations for subsequent use.

3.4. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoreses

Nondenaturing PAGE of native proteins for analysis of complex formation and destabilization was performed as previously described [70], using the same system as for denaturing PAGE, but with omission of SDS from sample, running and loading buffers. Denaturing page was with a standard Tris-glycine system after Laemmli [97]. ALK2 kinase was radiolabeled with [γ−33P]ATP (NEN-PerkinElmer, EasyTide, NEG602K250UC) diluted into cold ATP (100 μM) and analyzed by autoradiography of air-dried SDS-polyacrylamide gels. In both systems, proteins were resolved through 12% acrylamide gels.

3.5. Differential scanning fluorimetry (thermofluor)

Samples (25 μl) contained purified proteins (2 μg), +/− H-SAAD/Ds or ATP•Mg2+, 50 mM buffer (NaHEPES or Bis-Tris), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM TCEP and 10X SYPRO Orange dye. All mixtures in a series were normalized to equal concentrations of compound solvent (DMSO, NaOH, HCl). After preparation on ice, the samples were transferred to 96-well PCR plates and covered with optically clear sealing film. A Real-Time PCR instrument (CFX96 Bio-Rad) was programmed to ramp the temperature from 4°C (or 25°C) to 95°C in increments of one degree per minute and set to a channel to excite and measure fluorescence as for Cal Gold 540 fluorophore. At the conclusion of the ramp, the instrument exported data into an Excel file for the raw fluorescence signal as a function of the temperature and for the derivative of the slope of the curve. The melting temperature (Tm) was determined from the inflection point of the derivative of the curve (nearest zero).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. A regulatory element-proximal pocket (αC-β4 loop) is a putative binding site for allosteric small molecule modulators of type I BMP receptor kinase plasticity and activity

4.1.1. Supercomputer screen of large library of drug-like compounds targeting the site

As a result of our homology-based structural studies [9, 11], combined with in vitro comparisons of wildtype, mutant and variant forms of ALK2 kinase [11, 70–73], an alternative, mechanistically novel means of inhibition by small molecules was conceptualized (cf. 2.5). Since the recurrent R206H mutation, and most of the variants, appears to perturb the structure of the helix-loop-helix (GS) regulatory subdomain (Fig. 1B, upper left, red) that in turn affects the conformational plasticity of the protein kinase domain through aberrant allosteric effects, stabilization of the structural element by small molecules bound as a form of “molecular putty” at an adjacent pocket (Fig. 1B, left) was proposed as a means of buffering the mild activation of the ALK2 receptors in FOP patients.

To test the hypothesis, an in silico screen of nearly 650,000 small molecules, filtered for drug-like properties (ZINC library, UCSF) [95, 98, 99], was conducted through a web-based supercomputer portal, targeting the ring-like pocket comprising the αC-β4 loop, a key mediator of stability and allosteric regulation of protein kinases. After inspection of the docked poses, chemical nature and availability of the top 1000 calculated hits (decreased free energy of protein:small molecule complexes), ten compounds were selected and purchased from a ZINC-annotated commercial source for initial proof-of-concept assays of inhibitory activity with recombinant (cytoplasmic) kinase in vitro.

4.1.2. In vitro assays of ten selected hits test proof-of-concept of allosteric stabilizers

As judged by an autophosphorylation assay, none of the ten compounds detectably inhibited the kinase. However, in contrast to the other nine compounds tested, which had little to no discernible effect on the ALK2 receptor kinase, incubation with compound 8 (C8; our designation; Supplementary Information Fig. 1, bottom right; SI Fig. 2) reproducibly destabilized the protein, witnessed first by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis, which requires folded, native structure for resolution (SI Fig. 1, top). Because the docked compound appeared to destabilize the protein by binding and presumably unfolding in a concentration-dependent manner as judged by gel electrophoresis, an independent assay of protein stability and unfolding was employed (SI Fig. 1, bottom left). Thermofluor, also known as differential scanning fluorimetry or fluorescence thermal shift assay, provides a quantitative measurement of thermally induced protein melting through binding of a hydrophobic dye, which fluoresces with enhanced intensity upon binding the hydrophobic interior of globular proteins (reminiscent of the enhanced fluorescence of ethidium bromide intercalated in DNA) exposed by increasing temperature. As shown by the results of incubation with a range up to 100 μM, C8 induced the concentration-dependent shift in the thermal denaturation of recombinant ALK2 kinase that paralleled the results of an SDS-PAGE autoradiography assay of autophosphorylation and stability (SI Fig. 1, middle).

After the in silico screen was conducted and the unanticipated effect of C8 observed, an allosteric inhibitor of a microtubule motor protein was reported that was also identified through an in silico screen of the virtual library (ZINC) of commercially available drug-like compounds at UCSF and also shown to induce destabilization and unfolding by thermal shift assay (ΔTm −8.0°C, EC50 ~ 0.5 mM; IC50 ~ 0.1 mM) [100]. The high-profile results from the Department of Chemistry at Cambridge provided a paradigm validating our novel hypothesis, in silico approach and albeit inverted in vitro findings toward development of a therapeutic for HO. Of note: because the compound destabilized the protein in a concentration-dependent manner prior to denaturation (as did C8), binding was viewed as site-specific, in contrast to widespread, nonspecific hydrophobic interactions simply leading to formation of dye-binding aggregates.

4.2. ALK2 kinase is destabilized in vitro by a related set of in silico-docked hits

4.2.1. Compounds with destabilization activity share related terminal “warhead” groups

The remaining three one-milligram aliquots of C8 available from the supplier failed to reproduce the robust destabilizing effects of the initial sample. Similarly, a re-synthesis by an academic medicinal chemistry core facility also failed to provide active compound. Solubility of C8, like the other compounds initially purchased and tested, was marginal in aqueous buffer at the high (sub-millimolar) concentrations tested. Hence, the set of in silico hits was re-examined by searching for functional mimics of C8, preferably with improved solubility.

Consistent with the supercomputer-docked pose, a large body of circumstantial evidence supported the hypothesis that the nitrogen atom of the isoxazole ring of C8 formed hydrogen bonds with the one or more of the five H-bond donors (one –NH, two -NH2) of the sidechain guanidino group of Arg258, inducing non-native, destabilizing effects (Fig. 1C, D). First, four compounds (C1, C2, C3, C8) of the ten tested in the initial native PAGE screen shared related carboxamide-linked scaffolds, however the remainder of each abutted the sidechain of Arg258 with unrelated ring structures, amongst which only the isoxazole of C8 had the capacity to bind through more than weak and surface-dispersed van der Waals interactions. Moreover, C4, an inactive compound, lacked the related carboxamide scaffold but contained a central isoxazole ring, which in the docked pose, was stacked against a central island residue (His284), not abutted against the guanidino of Arg258. Taken together, destabilization of ALK2 kinase by C8 was hypothesized to result from formation of at least one hydrogen bond between the side chain of Arg258, which is a key switch residue of the αC-β4 loop [82], and the isoxazole ring projected out from a terminal position.

Based on the purported destabilizing interactions between C8 and the side chain of residue 258, twenty-one additional compounds were cherry-picked for a second, mechanism-guided screen. Of the twenty-one selected, eight (~ 40%) were relatively soluble in aqueous buffer (the other thirteen only marginally so or insoluble). All but two (C12, C15) showed destabilization activity by native gel assay (SI Figs. 3, 4). Thus six of eight, or 75%, of the rationally selected compounds that were soluble, hence testable, were active. As elaborated in the next paragraph, two of the six compounds (C14, C24) appeared to be serendipitously active; hence more strictly, four of the eight (50%) were active. Even so, such a high hit rate provided strong evidence in support of the proposed αC-β4 loop/Arg258-mediated mechanism, the basis of the second focused in vitro screen. Four active, testable compounds (50% hit rate) corresponded to about 0.4% of the remaining 990 from the 1000 calculated in silico hits from the large ZINC library (~642,000).

The above-mentioned C14 and C24 were related benzoic acids, both composed of synthetic mixtures of six stereoisomers (SI Figs. 5, 6), with three each docked with the solubilizing carboxylate group forming ion pairs with the positively charged Arg258 guanidino in some cases (cf. SI Fig. 3). C17, C19 and C20 were less related, sharing only portions of scaffolds between one another, but with a common oxadiazole ring related to the putative destabilizing isoxazole group of C8 (SI Fig. 8). C28 was a racemic mixture, with one of two stereoisomers docked in silico, with a putative destabilizing amino-pyridine ring (SI Fig. 7). Serendipitously, C14 and C24, selected for the putative ion pair-forming carboxylates, have isoxazole and oxazole rings, respectively, at the opposite termini of the common scaffolds. As shown below through a small structure-activity relationship study (4.5, 4.6), destabilization was inferred as mediated by the related heterocyclic rings, not the carboxylates, indicating that the calculated in silico poses were incorrect or functionally irrelevant. All six of the active compounds (C14, C24; C17, C19, C20; C28) then share nitrogen-containing heterocyclic rings, similar to the putative destabilizing isoxazole group in C8. More specifically, the nitrogen atoms participate in double bonds within the rings, hence are sp2-hybridized, leaving a lone pair of electrons extending out in the plane of the ring to act as a strong H-bond acceptor [101, 102].

In keeping with the proposed mode of interaction, C15, which was soluble but inactive, contained an isoxazole ring with the H-bond accepting nitrogen oblique, not perpendicular to the guanidino H-bond donors of Arg258. Otherwise the compound appeared complementary to the targeted pocket of the αC-β4 loop, consistent with the modest but reproducible stabilizing effect observed and measured by native gel and thermofluor assays. Although we have not ruled out stabilization by binding in the active site cleft, an effect commonly observed for competitive inhibitors, the behavior of C15 suggests that the six soluble destabilizers might interact with ALK2 by a combination of conflicting effects: on one hand, stabilizing site-specific binding by scaffolds of the compounds throughout the allosteric pocket, and on the other, destabilizing H-bond formation with the side chain of Arg258 by structurally and functionally related “warhead” groups (terminal protophilic H-bond acceptors; cf. 1.2).

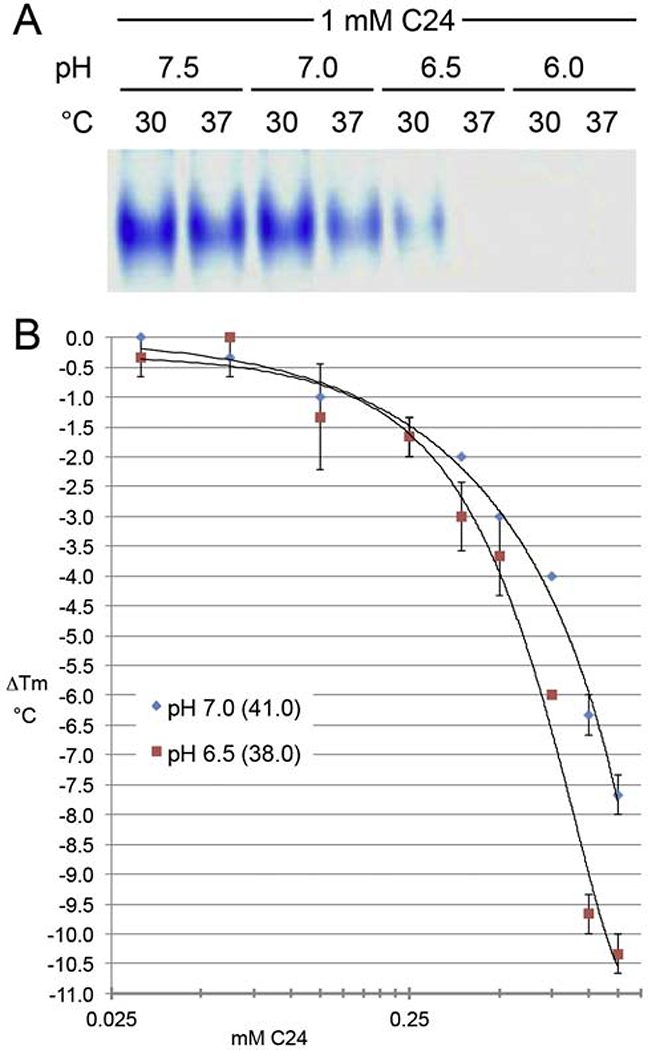

4.2.2. In vitro destabilization is temperature- and pH-dependent

As shown by native gel assay in Fig. 2A, destabilization activity was highly dependent on pH. Temperature also had an effect, consistent with the modest thermostability of ALK2 kinase (midpoint of unfolding in vitro slightly above physiological T; cf. Fig. 2B, in parentheses). At normoxic pH (~ 7.2) and above, a high concentration of compound (C24) had a marginal effect, whereas at hypoxic pH (6.5), destabilization was dramatic. Thus the efficacy of destabilizer is hypoxia-selective, whence the name, Hypoxia-Selective Allosteric ALK Destabilizer/Degrader, or H-SAAD/D (precedent for destabilization by targeted small molecules leading to proteasomal degradation; cf. 5.3). Qualitative native PAGE results obtained at a single concentration of C24 were confirmed and expanded by quantitative results from thermofluor, an orthogonal in vitro assay, over a broad range of concentrations with increasing disparity (above 0.25 mM) between destabilization efficacies at normoxic and hypoxic pH (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2. Compound 24 (C24) H-SAAD/D in vitro destabilization of ALK2 receptor kinase.

(A) pH-and temperature-dependence of loss of native structure of the recombinant type I kinase protein analyzed by nondenaturing PAGE assay after 30 min incubation with 1 mM C24 (w/o ATP•Mg2+). (B) pH-dependence of efficacy of C24 thermal denaturation of ALK2 kinase as determined by differential scanning fluorimetry, also known as thermofluor or thermal shift assay (w/o ATP•Mg2+; T ramp from 4°C; 2.5% DMSO; 10 mM C24 stock solubilized in DMSO). Midpoints of unfolding are in parentheses (°C).

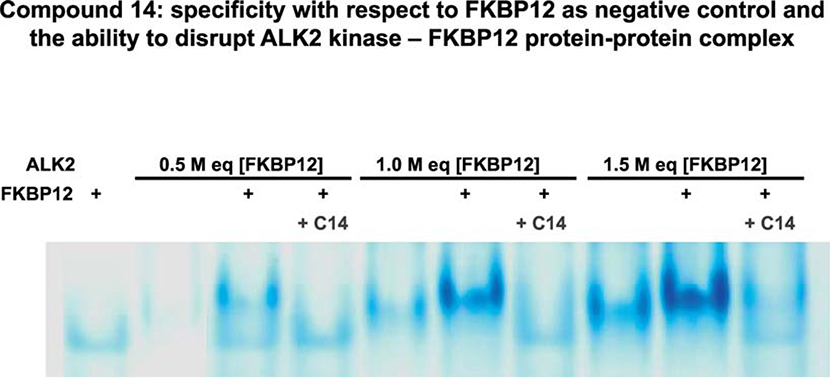

4.3. Specificity of mechanism of ALK destabilization shown with FKBP12 binding partner

4.3.1. FKBP12 is insensitive to C24-related compound 14 (C14)

Due to the concentration-dependence of unfolding observed by thermofluor assay (cf. 4.1, 4.2.2), H-SAAD/D binding was interpreted as site-specific. If indeed the case, as opposed to non-specific interactions dispersed over the surface, then the compounds should not destabilize proteins that lack the specific pocket. As a first test case, C14-sensitivity of the ALK binding partner, FKBP12, at three molar ratios of ALK2 was analyzed by native gel (Fig. 3). Since the quantity of native FKBP12 protein was unaffected by C14 at high concentration (1 mM; lanes 4, 7, 10), additional evidence was obtained in support of specificity of destabilization by H-SAAD/D. The interpretation must be tempered by the disparity in thermal unfolding midpoints for the two proteins: despite the small size (12 kDa), the Tm for FKBP12 is 66°C (calorimetric) [103], around 25°C higher than for ALK2. Unfortunately, the protein gives no signal with the thermofluor procedure, perhaps due to the small hydrophobic core, so the test case was not amenable to further analysis and the conclusion, although in agreement with other observations, could not be considered strong.

FIGURE 3. Specificity of H-SAAD/D destabilization mechanism demonstrated by the insensitivity of FKBP12 to C24-related C14.

Native PAGE analyses of ALK2 kinase at three molar equivalents (lanes 2 – 4, 5 – 7, 8 – 10) with respect to a fixed mass of FKBP12 (cf. lane 1). C14 was added to mixtures of the two proteins at 1 mM from a 10 mM stock solubilized in DMSO (lanes 4,7,10). All samples were incubated at ~ pH 7.5 and 37°C for 30 min prior to electrophoresis.

4.3.2. ALK2 kinase in complex with FKBP12 is not protected from C14 destabilization

Interestingly, by a specific effect on ALK2, C14 robustly disrupted the more slowly migrating but otherwise relatively stable complex of the two proteins. Thus FKBP12 bound to the kinase did not protect the protein from destabilization. Because the in silico-targeted pocket of the αC-β4 loop and putative C14 binding site neither overlapped with nor was even relatively close (cf. Fig. 1E), FKBP12 was unlikely to interfere sterically or with local conformational change. Hence the lack of protection from destabilization was another observation consistent with site-specific H-SAAD/D activity.

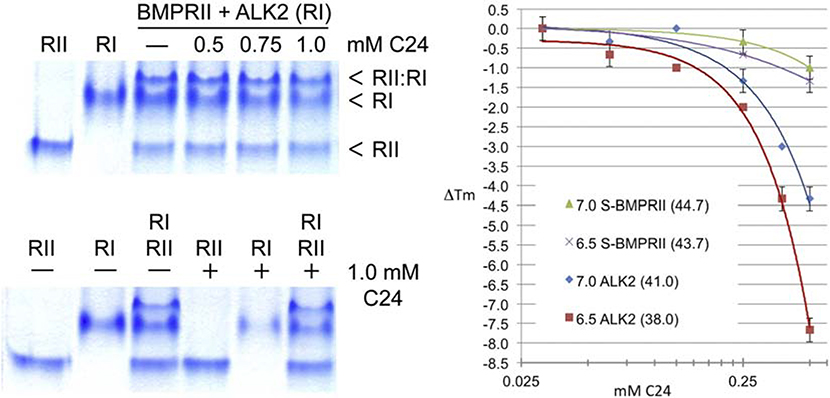

4.4. Specificity of mechanism and identity of site supported with BMPRII binding partner

4.4.1. BMPRII kinase lacks key residues of targeted site, is resistant to C24 destabilization

As a second test case, C24-sensitivity of another, albeit weaker in vitro binding partner, BMPRII kinase was analyzed both by native gel and thermofluor assays (Fig. 4). As shown on the lower left by comparison of control and plus C24 incubations (lanes 1, 4), BMPRII kinase was resistant to treatment with a high concentration (1 mM) of the compound, in contrast to the corresponding ALK2 samples, which showed the sensitivity of the type I receptor kinase (RI) to H-SAAD/D. In keeping with the results of the qualitative comparisons of the native gel assay, by thermofluor analyses over a range of concentrations and at normoxic and hypoxic pH, the type II receptor kinase was largely insensitive, whereas the ALK was significantly destabilized and nearly twice so with respect to change in Tm at the lower (hypoxic) pH.

FIGURE 4. Specificity of H-SAAD/D destabilization mechanism demonstrated by the resistance of BMPRII to C24.

Comparative analyses of C24 destabilization of type I (ALK2) and type II (BMPRII) BMP receptor kinases, qualitatively by native PAGE (left) and quantitatively by thermofluor analysis (right; w/o ATP•Mg2+; T ramp from 25°C; 5.0% DMSO; 10 mM C24 stock solubilized in DMSO. Native PAGE samples were incubated at ~ pH 7.0 and 37°C for 30 min prior to electrophoresis.

Note that type II and type I (ALK) receptor kinases likely arose from tandem duplication and remain structurally similar, excluding the 30 amino acid HLH-regulatory element of ALKs that precedes the conserved protein kinase domain. That said, BMPRII differs from ALKs at or near the putative H-SAAD/D binding site at three significant residues: (1) 258 is not arginine but glutamate, a charge inversion incapable of H-bond formation with compound warheads, (2) a pocket-forming glycine is substituted with a bulky, charged arginine that would block binding and (3) the 258-proximal histidine invoked as the source of pH-sensitivity is substituted with tyrosine, a non-ionizable steric isomer (ringed side chains) (cf. Fig. 7C,D below).

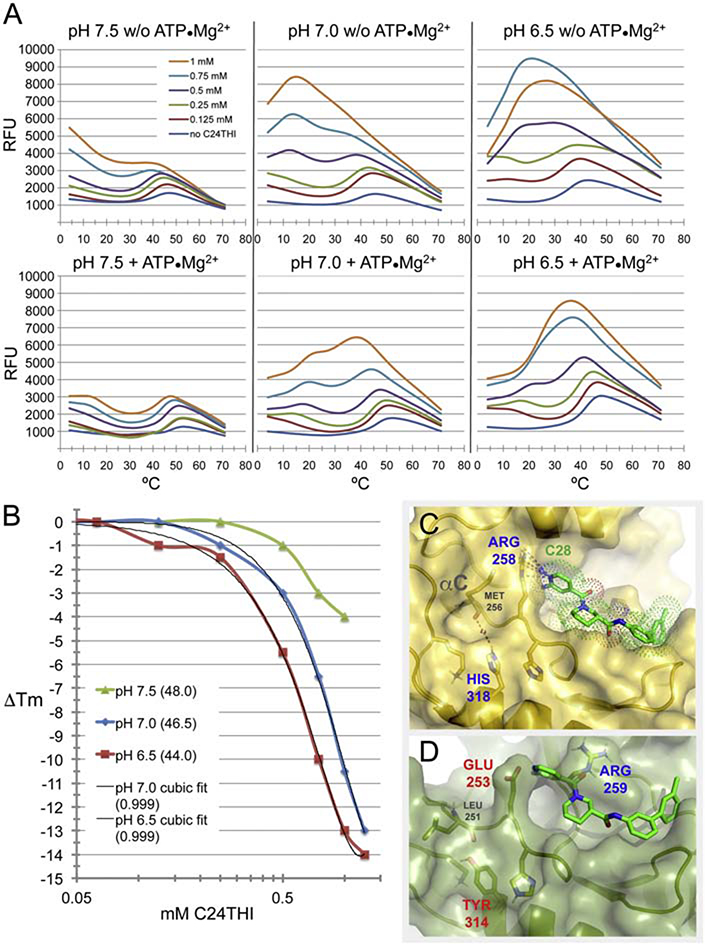

FIGURE 7. Thermofluor analyses of C24THI efficacy at three pH, with and without counter-stabilizing effects of ATP•Mg2+ binding in the active site cleft.

(A) Melting curves for a range of C24THI concentrations up to 1 mM at three pH, w/o and with ATP•Mg2+. (B) Negative shifts in Tm of ALK2 kinase protein with ATP•Mg2+ by C24THI. Values in parentheses refer to Tm without compound (at zero), or residuals (0.999) from third order curve fits. (C) Structure of ALK2 kinase, depicting the putative interacting Arg258 and ionizing His318 sidechains imparting H-SAAD/D- and pH-sensitivities, respectively, which are not shared with BMPRII (D).

BMPRII then provides a second specificity test case that can be interpreted more strongly than the first with FKBP12, since BMPRII kinase was less than four, not twenty-five, degrees more stable than ALK2 kinase and structurally similar, except for important differences at or adjacent to the targeted pocket predicted to block binding and render pH-insensitive, as observed. Thus the mechanism of destabilization can be viewed as specific to the ALK kinase, not due to promiscuous, nonspecific effects such as sequestration or partial unfolding by compound aggregates or detergent action, that can be valid concerns for flat, multi-ring, hydrophobic or “dye-like nuisance” compounds which behave as false-positives in small molecule screens for inhibitors [104–108].

4.4.2. ALK2 kinase in complex with BMPRII rendered resistant to destabilization by C24, supporting the proposed role of Arg258 as key mediator at protein:compound interface

As demonstrated in both native gel assays (Fig. 4), BMPRII and ALK2 formed a more slowly migrating species which was held together more weakly than the FKBP12:ALK2 complex, as evidenced by the residual monomers of each in equimolar mixtures. Nonetheless, a complex clearly formed that differed significantly from the one with FKBP12, in that BMPRII appeared to confer resistance to ALK2 to H-SAAD/D-induced unfolding. Although concentration-dependent destabilization of the complex and ALK2 (RI) in parallel was detectable, the effects were weak, not at all like those observed for FKBP12 bound to ALK2.

The contradictory results that a weak complex is more resistant to disruption than a strong one, could be reconciled by comparison of the locations of the protein-protein interfaces for FKBP12 (crystal structures) and BMPRII (reliable in silico docked complex) (cf. Fig. 1E, F). As mentioned (cf. 4.3.2), FKBP12 bound at a distance and was not expected to interfere with H-SAAD/D binding or activity, whereas in contrast, BMPRII appeared to bind proximal to the targeted site, abutting and constraining the side chain of Arg258, as well as the main chain of the αC-β4 loop. Thus if indeed a reliable approximation of the BMPRII:ALK2 complex interface, then the strongly diminished sensitivity to disruption of the weaker complex relative to the stronger FKBP12 counterpart provided further evidence in support of the key allosteric pocket targeted in silico as the actual specific-binding and functional site in vitro.

4.5. sp2 N atoms with H-bond accepting lone pairs of electrons in terminal heterocyclic rings are key mediators of destabilizing interaction at compound:protein interface

4.5.1. Destabilizing activities of a small set of commercially available C14/C24 analogs were compared to determine structure-activity relationships

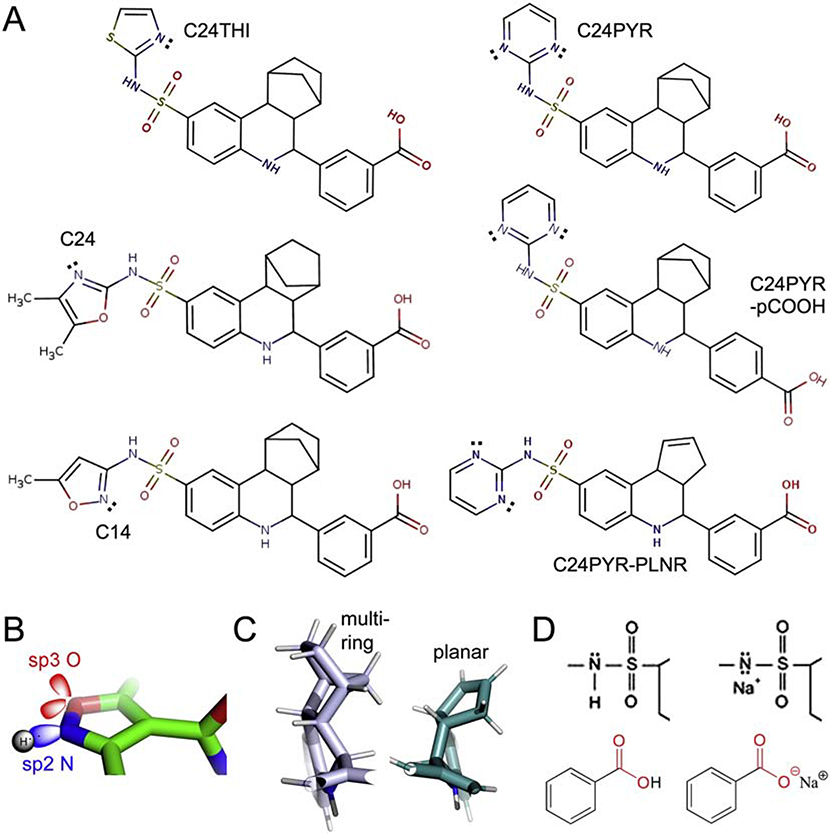

Having examined and established the hypoxia-selective and ALK-specific activities of C14 and C24 H-SAAD/Ds, we searched for commercially available analogs in order to gain insight into the pharmacophore substructures required for, and contributing to, activity, and to possibly identify compounds more active than the initial in silico leads, without resorting directly to synthesis of a library of derivatives. Four analogs were identified, and then purchased and tested that aided in dissection of the roles of substructures of the related C14/C24 pair (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5. Chemical structures of C14 and C24 virtual screen hits and four other commercially available derivatives.

(A) C14 and C24, methyl isoxazole and dimethyl oxazole warhead groups, respectively. C24THI and C24PYR, azole rings substituted with thiazole and pyrimidine. C24PYR-pCOOH, para-substituted benzoic acid ring at terminus opposite putative warhead groups. C24PYR-PLNR, substitution of a bifurcated five- and six-membered alkane basket of the central scaffold with a single planar, five-membered arene ring. Nitrogen atoms in heterocyclic aromatic rings have a single lone pair of electrons projecting out perpendicular to the ring. (B) Schematic representation of sp2 and sp3 lone pairs. (C) Lateral projection of PLNR derivative is compact and lies in plane. (D) Formation of disodium salts. C14/C24 family members have two acidic hydrogen atoms that can be neutralized with two equivalents of NaOH.

The set of six compounds shared four substructures: (1) sp2-hybridized nitrogen atoms in terminal heterocyclic rings serving as putative warhead groups [101, 102], (2) an identical sulfonamide group (-SO2NH-), which containing a weakly acidic hydrogen, (3) an interior multi-ringed scaffold, composed of a planar benzyl (C6), puckered piperidyl (C5N) and a five-membered ring extended out perpendicular to, or parallel with, the other two rings by two bonds forming a half-ring (except for C24PYR-PLNR) and (4) a benzoic acid group at the opposite terminus from the warheads.

As part of the second, mechanism-based screen (cf. 4.2.1), C14 and C24 were selected due to the shared benzoic acid groups, which as docked, were predicted to form ion pairs with the guanidino side chain of Arg258, potentially destabilizing the kinase. An additional important criterion was the enhanced aqueous solubility imparted by the benzoic acid group, which with a pKa of approximately 4.0, would be completely ionized at normoxic and even hypoxic pH. Hence only analogs with the solubilizing group were included in the small SAR study. Of primary importance was to further explore the relationship between the structure and activity of the nitrogen-containing, heterocyclic rings as warhead groups (Fig. 5B). Two more were compared: thiazole, which substituted a sulfur atom for the oxygen of the C24 ring and lacked both methyl adducts (C24THI), and pyrimidine, which solely contained nitrogen and, though a six- rather than five-membered heterocyclic ring, was isosteric (C24PYR). Furthermore, if the C24PYR analog were active, the initially predicted role of the carboxylate group could be tested with a para-position analog of the meta-position parent (C24PYR-pCOOH). Lastly, were C24PYR active, the need for the bulky, multi-ringed interior scaffold could be probed through substitution with a flatter, more planar structure (C24PYR-PLNR) (Fig. 5C).

4.5.2. Relative destabilization activities of related H-SAAD/Ds at normoxic and hypoxic pH

To compare the destabilization activities of the set of analogs, all six were solubilized with three molar equivalents of sodium hydroxide, which previously was shown to render C14 water-soluble at high concentration (50 mM) and more active than comparable dilutions from stocks in DMSO (10 mM). Two equivalents were necessary and sufficient for solubilization, consistent with the two acidic groups of the analogs that were converted to charged disodium salts (three provided more rapid dissolution)(Fig. 5D). Note that if aggregates of the H-SAAD/Ds were responsible for destabilizing ALK2 kinase by a non-specific mechanism, then activity should have gone down, not up, with the generation of mono-dispersed, water-soluble, disodium salts. Increased activity further supported the proposed site-specific mechanism of destabilization.

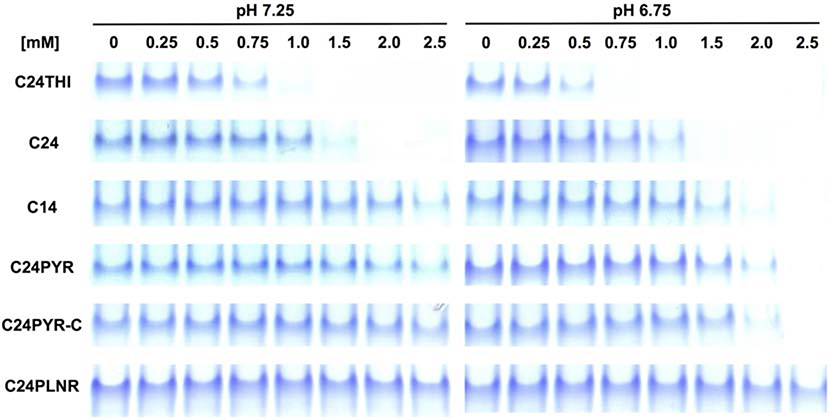

As shown by the composite results of twelve native gel analyses (Fig. 6) comparing the pH- and concentration-dependence of the six analogs, all but one of the compounds were clearly active. At the highest concentration and lower pH, destabilization by C24PLNR was barely, if at all, discernable. All five others showed markedly higher activity at the lower, hypoxic pH (6.75). As observed before, C24 was around twice as active as C14, which shared concentration-dependent profiles with the two active pyrimidine (PYR) analogs at both pH. The fourth newly tested analog, C24THI, was around twice as active as C24 at both normoxic and hypoxic pH.

FIGURE 6. Native PAGE analyses of relative destabilization activities for small SAR study.

The effects of concentration series of C14 and C24 virtual screen hits and four commercially available derivatives were compared at two pH that approximate normoxic (7.25) and hypoxic (6.75) intracellular conditions.

Despite the small size of the SARs, conclusions could be drawn and insights gained. First and foremost, the sp2 nitrogen of the heterocyclic rings appears to be the key atom inducing destabilization, since the two active pyrimidines with only such nitrogen atoms were equally as active as C14, with both sp2- and sp3-hybridized nitrogen and oxygen, respectively. Secondly, since the profiles of the two active pyrimidines were indistinguishable, regardless of the position of the carboxylate of the benzoic acid ring (meta- or ortho-), the group appears to solely serve to solubilize, not participate directly in destabilization. Hence the in silico docked poses of C14 and C24 from the second mechanism-based screen were almost certainly artifact, but fortuitous, since both were composed of azole (isoxazole, oxazole) rings at the opposite termini. Finally, since on the other hand, the pyrimidine analog with a planar, not bulky, interior scaffold was for all purposes inactive, then the projection of the third ring out from the center of the analogs played a role in binding or anchoring the destabilizers. Again, if aggregates of H-SAAD/Ds non-specifically destabilized the kinase, then a flat, dye-like compound like the planar pyrimidine more prone to aggregation would be more active, not inactive, further supporting site-specificity.

The basis for the increased activity of the C24THI analog over C24 could only be speculated. One or both methyl adducts on C24 might have interfered sterically, or the smaller radius of the C24 oxygen atom compared to the C24THI sulfur or dispersion of electrons in the oxazole versus the thiazole rings affecting H-bond formation could be factors. Regardless, the trio of analogs, C24THI, C24 and C14, prepared as high concentration, water-soluble, disodium salts, provides a small set of H-SAAD/Ds with a range of activities for further in vitro, and eventually cell-based and perhaps even animal model studies (cf. 4.5, below).

4.6. Status of the other destabilizers identified in the second, mechanism-based screens

Though all of the destabilizers identified in the second, mechanism-based in silico and in vitro screens shared terminal sp2 nitrogen-containing heterocyclic rings as putative warheads, the others were not included in the small SAR study because the structures were too dissimilar (cf. 4.2.1). Though C14 and C24 were closely related, C17, C19 and C20 were less so, sharing only portions of scaffolds between one and the other. The three oxadiazole compounds also were less active than C14 and C24, plus had no commercially available analogs for comparison to our knowledge, so were all together undesirable for further evaluation. However, the subset of compounds did contribute to the formulation of our initial hypothesis for the mechanism of destabilization by H-SAAD/Ds, since all three docked with the oxadiazole groups juxtaposed to the guanidino of Arg258, reminiscent of that of the isoxazole of C8, the initial hit.

C28 was unique in structure, and function. The terminal amino-pyridine group of C28 was reliably docked in juxtaposition to the H-bond donor side chain of Arg258, with clear potential for the lone pair electrons of the sp2 hybridized nitrogen of the heterocyclic ring to act as an acceptor (cf. Fig. 7C, below). Consistent with the ideal pose, C28 was at least twice as active as C24THI by pH- and concentration-dependent native gel assay (data not shown), thus nearly an order of magnitude more active than C14. Another benefit was that the amino adduct of the 2-aminopyridine ring (pKa = 6.86) was sufficiently basic to form a water-soluble, hydrochloride salt (one equivalent HCl), obviating the need for DMSO. However, due to inherent background fluorescence, the activity of the compound could not be quantitated or analyzed by the thermofluor method. Interestingly, though the most active destabilizer identified to date, C28 was not regarded as an H-SAAD/D, since unexpectedly, the compound did not show pH-selectivity. Destabilization over the range of concentrations was indistinguishable at normoxic and hypoxic pH. So though not a hit-to-lead compound due to the lack of hypoxia-selectivity and potential as a prophylactic, C28 might prove valuable as an investigative tool and provide insight for rational design of second-generation derivatives.

4.7. Destabilization by H-SAAD/Ds is bimodal, with two likely αC-β4 loop perturbations

4.7.1. C24THI induces a concentration dependent, partial unfolding event significantly below the Tm of ALK2 kinase that merged with global unfolding of the protein at low pH

Differential scanning fluorimetry (thermofluor), a proven, powerful method for initial screens of small molecule libraries for enzyme inhibitors based on stabilization rather than activity, has also increasingly become a valuable tool for mechanistic investigations [109]. That said, interpretation of thermal denaturation curves, in complex cases, i.e. not resulting from a simple two-state transition with an initially native, ideally responsive protein, can be difficult and subject to error [110]. Before inspections of most melt curves, two features typically require consideration. Thermally induced unfolding and dye binding yield central sigmoidal curves, which do not plateau, but instead, after reaching a peak, fall off in a linear (non-specific) manner due to precipitation of the protein as aggregates of the denatured polypeptides. In addition, if a protein is only nominally stable at low temperature or under sub-optimal in vitro conditions, a fraction of the population will bind dye and produce an elevated signal prior to initiation of the temperature ramp.

In the absence of destabilizer, melt curves for ALK2 and BMPRII kinases (recombinant cytoplasmic constructs) exhibited denaturation-induced, post-peak precipitation, but nominal pre-ramp dye binding. Thus the structurally related kinases were reasonably well suited for meaningful thermofluor analyses of protein stability, as opposed to, for example, FKBP12, which did not yield significant dye-binding fluorescent signal above background (cf. 4.3.1). In order to gain insight into the nearly indispensible contribution of hypoxic (or sub-normoxic) pH to the mechanism of destabilization by H-SAAD/Ds, we performed and analyzed six pH-, substrate- and concentration-dependent thermal denaturation series of ALK2 by C24THI, the most active H-SAAD/D identified to date (Fig. 7A).

Note that in the absence of destabilizer (Fig. 7A, blue melt curves), two parameters affected the unfolding profiles of ALK2 kinase in a combinatorial manner: pH and ATP•Mg2+ -complex substrate. As pH was incrementally decreased, the mid- or inflection-points of the sigmoidal curves (Tm) generally decreased. As commonly observed for kinases, the substrate complex stabilized the enzyme, shifting the curves upward and the Tm values positively by about 6°C on average. Of further note, at slightly basic (7.5) or neutral pH, ALK2 produced relatively weak dye-binding signal, suggesting that the protein did not unfold substantially before aggregating and precipitating out of solution. At pH 6.5 however, greater signal was observed, indicative of more unfolding, and particularly with substrate stabilization, a more extensive, cooperative event. Also noteworthy was the slight destabilization apparent without compound at hypoxic pH, 37°C and with saturating substrate, indicating that under physiological conditions in hypoxic cells, the kinase would be on the verge of destabilization, easily perturbed by compound, as opposed to ALK2 in cells in normoxic tissues, which would be less sensitive.

The destabilizing effects of C24THI were complex. At slightly basic pH, the compound had concentration-dependent effects on stability at 4°C, more so without substrate stabilization, that led to precipitation of a fraction of the protein population. Sigmoidal unfolding events shared with, but progressively shifted downward from, that of the no-compound control were also observed. At neutral pH, the compound had dramatic effects, producing an apparent distinct unfolding event with midpoints around 15°C for substrate-stabilized kinase that could not be estimated for free enzyme, but in both cases yielded high fluorescence at 0.5 – 1.0 mM C24THI. At the highest concentration of compound without the substrate complex, the signals from the two distinct unfolding events merged into one curve with an extraordinarily high peak, which then decayed linearly, indicative of non-specific aggregation and precipitation.

At hypoxic pH, effects of the H-SAAD/D concentration series were similar to those at neutrality but much more dramatic. Both with and without the ATP•Mg2+ complex, the curves for the two events began to merge at lower concentrations of compound. As an aside, the inversion of the melt curves at the two highest concentrations for both pH 6.5 series appeared to result from limited of solubility of C24THI at 1.0 mM that was both visualized and reconciled. The pKa of the sulfonamide group containing the weakly acidic (NH) hydrogen is estimated to be between pH 6 and 7, so the contribution to solubility of the sodium salt would be diminished at pH 6.5. In Fig. 7B, the apparent saturation of C24THI at the highest concentration at pH 6.5 is similarly an artifact of bordering on the limits of solubility.

With the thermofluor dissection of the mechanism of destabilization of ALK2 by H-SAAD/Ds, the essential role of hypoxic pH was revealed. At low pH, C24THI induced a second unfolding event significantly below the midpoint of global destabilization of the protein that, as a function of concentration, lowered the midpoint and also dramatically increased the extent of unfolding. At physiological temperature (37°C), the destabilizing effects at a given concentration of C24THI were shown to differ substantially between normoxic (7.5 > 7.0) and hypoxic pH (6.5) (Fig. 7B). Thus due to the induction of a second unfolding event at a lower temperature and the ensuing dramatic destabilizing effect, H-SAAD/D might be dosed at a level that would have minimal effect in cells at normoxic conditions, but would be efficacious in cells of tissues subjected to trauma that become hypoxic. Consequently, in addition to serving as therapeutics to inhibit HO long-term following blast injuries, severe burns and orthopedic procedures, H-SAAD/Ds have potential to act as prophylactic drugs that could be prescribed lifelong for FOP patients with genetic propensity for trauma-induced flare-ups that often culminate in mineralized soft tissues.

4.7.2. Ionization of an ALK-specific histidine side chain at hypoxic pH hypothesized to synergistically distorts the main chain conformation of the αC-β4 loop allosteric hub

Histidine is the only amino acid residue to ionize over the physiological pH range, hence must be responsible for the dramatic pH-dependency of destabilization of ALK2. In order to identify the structural basis for the effect of hypoxic pH, the positions of side chains were compared with those in BMPRII, which was relatively insensitive to lower pH. A single histidine residue is unique to ALK2 and the other activin receptor-like kinases, His318 (Fig. 7C,D), which conceivably could affect the conformation of the protein through interaction by the side chain. Several residues were unique to ALK2, however at those positions, the side chains projected out and away from other groups, thus with respect to stability, ionization would have little effect.

Intriguingly, ALK2 His318 is the afore-mentioned outlier residue (cf. 2.5.4), substituted for a structurally and functionally conserved tyrosine residue in other eukaryotic protein kinases that extends from the α-E helix of the N-lobe and anchors the main chain of the αC-β4 loop, the hub that relays allosteric signals between the N-lobe R-spine, the ATP-binding active site and the C-lobe [82]. As depicted in Figs. 7C and D, the side chain of the two counterparts in BMPRII and ALK2, Tyr314 and His318, respectively, protrude from the α-E helix, a rigid element of secondary structure, enabling formation of an H-bond between the hydroxyl oxygen of the tyrosyl residue and the main chain (Leu251 CO) of the αC-β4 loop, which in the ALK structure adopts a conformation which precludes formation of an H-bond between the imidazole of the histidyl residue and the juxtaposed αC-β4 main chain.

Although the relative orientations of the acceptor and donor are not conducive to formation of a bond, at pH 6.5 the imidazole side chain would become partially ionized (protonated), which would enhance H-bond formation with a partially negatively charged carbonyl oxygen of the adjacent loop (ALK2 Met256). If so, since the histidine imidazole extends from a rigid structural element (α-E helix) that serves as an anchor to the C-lobe within the allosteric hub, whereas the main chain interaction is centrally located within the αC-β4 loop, ionization at hypoxic pH could induce a change in conformation similar to that of BMPRII and other protein kinases, perturbing the loop in a synergistic manner along with compound warhead-Arg258 side chain interaction.

If indeed responsible, then the two factors required for hypoxia-selective destabilization by H-SAAD/Ds would both be mediated through the αC-β4 loop, acting just two residues apart. Both effects would be through formation of H-bonds that are postulated to contort the backbone of the allosteric hub loop. One would be direct to the main chain due to ionization at hypoxic pH (His318 ImH+- Met256 COδ−) and the other indirect through distortion of the long, flexible side chain of Arg258 due to interactions of the lone pair electrons of the sp2 nitrogen-containing warheads of the small molecules. The coincidence seems remarkable on one hand, given that a three residue segment in a 330-plus residue construct would act as the sole destabilizing switch, but logical on the other, given the synergistic nature of the two effects and the well documented role of the αC-β4 loop, which the segment is focal to, in stability and allostery.

Note that flexibility of the backbone at residue 258 is not hypothetical but can be observed by superposition of two crystal structures from SGC Oxford of ALK2 kinase in complex with either FKBP12 (PDB ID 3H9R) [10] or FKBP12.6 (PDB ID 4C02). Although the conformational difference might largely be an artifact of crystallization derived from the latter structure (4C02), nevertheless the plane of the peptide bond N-terminal to Arg258 is rotated roughly 60°, a mark of backbone flexibility generally not found throughout the kinase protein. The main chain at the residue is apparently predisposed or sensitive to disruptive forces resulting from protein-protein interactions and/or crystal packing, supporting the proposed dual destabilizing effects mediated by the long extended and conformationally diverse arginine side chain as well as via perturbations mediated by the adjacent ionizing histidine side chain. In a related note with respect to the collective kinase-inhibitor structures determined at SGC Oxford with ALK2 constructs, crystallization was achieved at pH 6.5 and below; however the proteins were held at 4°C or 25°C, well below the threshold of destabilization observed by thermofluor with ATP•Mg2+ substrate, a more modestly stabilizing ligand than the ATP-competitive inhibitors.

4.8. Destabilization by C24 concomitantly inhibited phosphorylation activity in vitro

Though the initial premise was to restrict or buffer the conformational plasticity linked to activin receptor-like kinase activation through stabilizing small molecules, destabilization by H-SAAD/Ds was similarly anticipated to lead to diminished kinase activity. To test the alternate premise, pH-dependent inhibition of ALK2 phosphotransferase activities by the C24 H-SAAD/D was assayed by SDS-PAGE/[γ−33P]ATP autoradiography of phosphorylation of ALK2 (autopALK2) and casein polypeptides (pCasein) (Fig. 8). Note that, since loss of protein observed by native gel assay due to destabilization was not detected by SDS-PAGE, H-SAAD/Ds appeared to induce only partial unfolding as opposed to complete and irreversible denaturation after incubation at 30°C (or 37°C, not shown), even at high concentration (1 mM). That is, pre-treatment with destabilizer had no effect on either mobility or staining intensity of ALK2 protein analyzed on detergent-containing gels. Such an effect, a modest destabilization as opposed to a global unfolding and irreversible aggregation, was in keeping with (1) targeting the αC-β4 loop to affect stability and allostery, (2) partial unfolding as judged by dye-binding with minimal precipitation for the initial compound-induced melt curves in thermofluor assays (4.7.1; Fig. 7A) and (3) partial renaturation of low pH, H-SAAD/D-unfolded kinase by raising the pH with alkaline buffer prior to native gel analysis (data not shown).

FIGURE 8. pH-dependent inhibition by C24 of surrogate Smad-substrate phosphorylation.

(top) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of ALK2 kinase and casein substrates with and without C24 at four pH spanning the physiological range. (bottom) [γ−33P]ATP autoradiogram of autophosphorylated ALK2 kinase and three (α/β, κ) casein polypeptides.

Dephosphorylated casein polypeptides, which are commonplace non-specific substrates for assay of protein kinase activity, serve as surrogates for the biologically relevant downstream effector R-Smads. Activin receptor-like kinases are only weakly active: compare the extent of autophosphorylation (at a single, non-relevant site) with that of phosphorylation of casein, which is composed of several polypeptides with numerous sites each. Nevertheless, like the flexible C-terminal tails of R-Smad MH2 domains, the site of the downstream phosphorylations, caseins are also unstructured. Thus, though weakly modified, the polypeptides act as mimics and provide a means of gauging the effects of inhibitors on activity of the receptor kinase enzyme.

As clearly shown by the results of autoradiography (Fig. 8, bottom), C24 inhibited phosphor-transfer to casein in a pH-dependent manner that paralleled that of C24-induced destabilization of the enzyme. Little to no effect was observed at pH 8.0, yet as the pH progressively lowered, so did the inhibitory activity of the H-SAAD/D. A similar trend, though less clear due to relatively higher activity and over-exposure, was seen for autophosphorylation. In contrast to the weak phosphotransferase activity of ALK2, the enzyme showed strong protein substrate selectivity. In addition to the propensity for autophosphorylation highlighted above, modification of casein polypeptides did not simply mirror relative abundance, hence polypeptide substrate accessibility (and complementarity) dictated by the conformation of the active site cleft likely played a role (the moderately staining, faster migrating species was a poor ATP γ-phosphoryl acceptor; the strongly staining, slower migrating form appeared to be a doublet of two species with disparate acceptor activities). Note that the partial, local unfolding effects of destabilizers, discussed in this section above, were similarly consistent with partial but progressive pH-dependent inhibition.

Therefore from the standpoint of biomedical relevance, H-SAAD/Ds did significantly more than simply destabilize the protein kinase. Phosphorylation of a surrogate Smad substrate was inhibited in a selective manner at hypoxic pH, which contingent on dosing, offered evidence of a potentially safe and efficacious means of inhibiting BMP receptor kinase signaling in soft tissues subjected to trauma that would otherwise be at substantial risk of undergoing debilitating HO.

5. Conclusions, future directions and drug development opportunities

5.1. Identification of a new approach for HO with broad therapeutic potential

The ring-like pocket comprising the αC-β4 loop, a key mediator of stability and allosteric regulation of protein kinases, has been revealed as a druggable, allosteric switch. Since the element is conserved in structure and function, the pocket formed by the αC-β4 loop offers a here-to-fore uninvestigated target for allosteric inhibition of the over 500 members of the protein kinase family encoded in the human genome. Conceivably, any protein with a crevice for small molecule binding and an adjacent multivalent H-bond donor, such as arginine or lysine, in a malleable loop might also be sensitive to small molecule destabilizers, expanding the realm of druggable targets yet further to include enzymes and non-enzymes alike.

While the newly identified avenue shares aspects with other mechanisms of action (MOAs), the basis is unique. Like other leading-edge therapeutics in development [87], H-SAAD/Ds are not ATP-competitive inhibitors but instead target an allosteric pocket. The effect at the site, partial unfolding due to destabilization, is also leading edge but mechanistically distinct (cf. 4.4, below). Our initial premise, stabilization of the dynamic structures by small molecules at allosteric sites, was a well-supported, previously established concept. Referred to as pharmacological, medical, chemical and small-molecule non-inhibitory chaperones [89–93] or even “correctors” [109], such small molecule modifiers typically act to restore loss-of-function, not diminish or quench gain-of-function, per our initial hypothesis (cf. 2.5.3, 2.5.4). On the other hand, the specific unfolding by small molecules of a target protein, as we report here, is highly sought after but uncommon. Selective estrogen receptor degraders or SERDs, which destabilize and induce degradation, are competitors of hormone binding and represent the closest, and only, example to date (cf. 5.4).

5.2. Two H-bond donor residues, the central multivalent arginine of the αC-β4 hub and the adjacent ionizable histidine of the αE helix of the C-lobe, are key mechanistic elements

Previously, structure-function analysis of variant FOP mutations of residue 258 led to the proposal that the arginine side chain, a long extended multi-valent H-bond donor, anchored the main chain, rather than the HLH autoinhibitory element, the prevailing hypothesis [111]. In other words, the HLH segment was not significantly fixed in place by, but instead contributed in the opposite sense to stabilization of, the αC-β4 loop, which in other protein kinases mediates allosteric regulation of activation [80].

In addition to our correlative studies of ALK2 variant structures and FOP phenotypes, our experimental findings reported here lend further support to the fundamental role of the loop and Arg258 in regulating the stability and activity of the type I receptor kinase. As highlighted above (cf. 2.5.4), the loop and residue were identified as a key hub in stability and allosteric regulation from pioneering and extensive studies of the substructures and dynamics of protein kinases [80]. Therefore, in light of the three independent supporting conclusions, the αC-β4 loop and centrally located Arg258 residue have moved to the fore as one of the most, if perhaps not the most, important single center of regulation in activin receptor-like kinases.

In a similar vein, our experimental results, interpreted within the comparative context of the BMPRII and ALK2 kinase crystal structures, led to the hypothesis that the adjacent ALK2-specific histidine of the αE helix (His318) was responsible for destabilization of ALK2 at hypoxic pH, due to ionization and formation of a hydrogen bond with the main chain of the αC-β4 loop. The role of the analogous residue in other protein kinases besides ALKs, a conserved tyrosine, has been recognized as a key component of propagation of allosteric signals through the core of the enzymes, similarly by formation of a side chain – main chain hydrogen bond connecting the αE helix to the αC-β4 loop [80].

5.3. Validation of H-SAAD/Ds as a family and mechanism of action via collective evidence

Although at an early stage of development, proof-of-concept has been demonstrated with respect to specificity of binding and activity (non-linear; RII-insensitivity; implication of Arg258; small SARs series) and with respect to hypoxia-selectivity (dependency on the lower range of physiological pH; pinpointing of a unique and key histidine residue). Thus, work-to-date has validated the pocket of the αC-β4 loop as an allosteric target and identified H-SAAD/Ds as a family of small molecule destabilizers, which combined, open up a new therapeutic avenue with potential for development of a prophylactic drug for HO that could be safely and efficaciously administered over prolonged periods.