Abstract

Neuropsychiatric disorders are comprised of diseases having both the neurological and psychiatric manifestations. The increasing burden of the disease on the population worldwide makes it necessary to adopt measures to decrease the prevalence. The Klotho is a single pass transmembrane protein that decreases with age, has been associated with various pathological diseases, like reduced bone mineral density, cardiac problems and cognitive impairment. However, multiple studies have explored its role in different neuropsychiatric disorders. A comprehensive search was undertaken in the Pubmed database for articles with the keywords “Klotho” and “neuropsychiatric disorders”. The available literature, based on the above search strategy, has been compiled in this brief narrative review to describe the emerging role of Klotho in various neuropsychiatric disorders. The Klotho levels were decreased in various neuropsychiatric disorders except for bipolar disorder. A suppressed Klotho protein levels induced oxidative stress and incited pro-inflammatory conditions significantly contributing to the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorder. The increasing evidence of altered Klotho protein levels in cognition-decrement-related disorders warrants its consideration as a biomarker in various neuropsychiatric diseases. However, further evidence is required to understand its role as a therapeutic target.

Keywords: Klotho, Neuropsychiatry, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, Depression

Introduction

Neuropsychiatric disorder encompasses a broad range of medical conditions that involve both neurological and psychiatric symptoms. Common neuropsychiatric disorders include; Schizophrenia, seizures, attention deficit disorders, cognitive deficit disorders, palsies, uncontrolled anger, migraine headaches, addictions, eating disorders, depression, and anxiety. Neuropsychiatry is concerned with disorders of affect, cognition, and behavior that arise from overt dysfunction in the cerebral function or the indirect effects of the extracerebral disease. The main symptoms of neuropsychiatric disorders are episodes of various psychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment as the main feature, and the occurrence of cerebral symptoms, and some of the main symptoms are anxiety, mood disturbances, diversion from normal behavior, and changes in memory [1].

The name Klotho was derived from the Greek goddess Clotho as a metaphor for the life span of the individual. Klotho, commonly known as an antiaging protein, was first reported in animal studies [2]. Mouse deficient in the klotho gene demonstrated accelerated aging and decreased life span to less than eight weeks [2, 3]. The increased expression of the klotho gene is associated with improved life span and cognition in organisms [3]. The increasing evidence points towards a crucial role that Klotho protein may play in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Structure and Regulation of Klotho Protein

The gene for Klotho protein is located on the long arm of chromosome13 (13q12). The klotho gene encodes a transmembrane protein with a smaller cytoplasmic domain and a larger extracellular domain. Metalloproteinase enzymes ADAM 10 and 17 shed Klotho from their membrane sites [4–6]. Insulin and the presence of calcium present outside the cell facilitate the process of shedding Klotho [7]. The extracellular domain, measuring 150 kDa, is the largest and undergoes enzymatic cleavage by sheddase enzyme to form soluble klotho. Further, the klotho gene, comprising three exons and two introns, undergoes alternate splicing to form 70 kDa Secretory Klotho. So, there are three distinct types of Klotho; transmembrane Klotho, secretory Klotho, and soluble Klotho protein [8].

The expression of Klotho is modulated by different factors. The klotho gene is negatively regulated by inhibition of its transcription by the transcription factor, Sp1. In renal tubules, angiotensin II suppresses the expression of the klotho gene by indirectly inhibiting the Sp1 by phosphorylation via protein kinase C [9, 10]. SP1 can activate and suppress the expression of genes involved in processes such as senescence, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. Sp1, when overexpressed, leads to increased klotho gene expression causing a decrease in oxidative stress. Similarly, a decrease in SP1 expression leads to suppressed Klotho protein levels due to decreased transcription of the klotho gene [11]. Apart from SP1, klotho mRNA production is also inhibited by Tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) by producing Nuclear factor κ-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) [12]. TNF- α causes translocation of IKB- α (inhibitor of NFkB) from NFkB-β which allows the NFkB-β to enter the nucleus [13]. Further, Klotho protein levels have also been shown to be decreased in patients with diabetic nephropathy and reduced fluid intake [14]. Vitamin D and epidermal growth factors also influence the expression of the klotho gene. Vitamin D response element present in the klotho gene activates klotho gene transcription on binding with Vitamin D [15, 16]. Other factors like peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), erythropoietin, ras homolog gene family A, rapamycin, statins, fosinopril, and losartan have also been shown to influence the expression of the klotho gene [17–23].

Fig. 1.

(A) Brain; (B) Choroid plexus; (C) Molecular mechanism of Klotho synthesis in cells of choroid plexus and different form of Klotho; (D) Circulating Klotho in blood vessels; (E) Structure of Klotho protein

Polymorphisms and epigenetics

KL-VS (Klotho variant) is a common haplotype observed in the general population. The variant had been associated with a higher incidence of dementia in the elderly population [24]. KL-VS homozygosity leads to decreased Klotho protein levels resulting in deranged intrinsic connectivity among the functional networks of the brain [25]. However, KL-VS did not affect cognition and brain structure in early life development [26]. KL-VS heterozygosity had also been found to be associated with reduced Alzheimer’s disease risk and Aβ burden in elderly individuals having APOE4. This advocates the inclusion of the KL-VS genotype in conjunction with the APOE genotype in Alzheimer’s disease prediction models [27, 28].

The klotho gene polymorphisms had been associated with aging-related outcomes and mortality in the elderly population [29]. A recent meta-analysis by Zhu et al. demonstrated an association between klotho F352 V polymorphisms and longevity [30]. Although individual studies have associated G-395 A with cognitive impairment, the meta-analysis did not find an association between G-395 A with cognitive impairment [30, 31]. The klotho gene polymorphisms were also found to have a role in inflammatory outcomes in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) patients. KL genotype (KL-VS SNPs) and methylation status at cg00129557lead to reduced chromatin binding and expression resulting in individual differences in inflammatory outcomes in PTSD patients [32].

Wolf et al. demonstrated that the rs9315202 SNP in the klotho gene showed increased peripheral inflammation and decreased white matter integrity, particularly in right-lateralized tracts connecting prefrontal to limbic regions. There is an alteration in klotho gene expression via non-coding RNA (ncRNA) due to this SNP. This reduced klotho gene expression leads to the weakened activity of synapses and neurocognitive loss, mainly in people more than 30 years of age [32]. Yin demonstrated that there is a decreased Klotho protein levels in patients with unilateral ureteric occlusion due to TGF β which leads to renal fibrosis. In conditions like inflammation, there is an increase in tumour growth factor β, which leads to epigenetic changes in klotho gene expression. TNF β leads to activation of DNA methyltransferase 1 and 3acausinghypermethylation of the klotho gene promoter region, culminating in transcriptional inhibition. So Klotho protein formation is decreased, which can lead to neurocognitive loss [33].

Role of Klotho Protein in Central Nervous System

Choroid plexus (ChP), Oligodendrocytes, and myelin

The role of Klotho protein in the brain had been elucidated with the help of memory tests that the Klotho protein-deficient mice were subjected to. A hippocampus-related cognitive function decline had been demonstrated in Klotho protein-deficient mice [34]. Klotho protein in the brain had been observed to have a significant function in ChP and neurons [35–38]. The functions of Klotho protein, which started appearing in utero, progressively increase till adulthood and then decline with age [35, 37, 39]. Cells of the epithelial lining of the choroid and neurons of Purkinje cells of the cerebellum have shown the presence of Klotho protein [36, 37]. Klotho protein present in the cells of ChP gets shed into the CSF in presence of small quantities of calcium [40, 41].

The expression of klotho changes with the progression of age, and its primary effect has been in oligodendrocytes and myelin [39, 41]. The number of oligodendrocytes had demonstrated a reduction in Klotho deficient mice [42, 43]. There have been decreased myelin-forming processes observed at low Klotho protein concentrations in white matter tracts [43]. Distinction and progression of oligodendrocytes required shed Klotho protein [43, 44]. Further, an increase in myelin formation occurs in the klotho gene overexpressing conditions. This shows that Klotho is important in oligodendrocytes and myelin formation [45].

Hippocampus and pituitary gland

Hippocampus is the central part of our brain related to cognitive functions like memory and learning ability. Short-term and long-term memories are associated with the hippocampal region. The functioning of the hippocampus declines with increasing age and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s disease. In Klotho deficiency, there is increased oxidative stress in the hippocampus and increased markers of programmed cell death [35, 46]. An animal study in mutant mice with low Klotho protein levels demonstrated decreased memory and learning (cognition) in mice at the age of 6th to 7th week of life [34]. Similarly, an increased expression of the klotho gene is associated with improved memory and learning with decreased oxidative stress [42, 47]. The Klotho protein also helps in the formation of new neurons from a neural stem cell. As a result, Klotho protein deficiency leads to the formation of immature neurons, resulting in decreased cognition. An in vitro study has observed an increase in the proliferation of neurons with shed Klotho [47].

Although Klotho does not show its expression in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, its components, i.e. shed Klotho, are circulated in the pituitary. Further, the presence of Klotho mRNA has been demonstrated in the pituitary gland [48]. The Klotho protein-deficient mouse had demonstrated a decrease in the number of pituitary cells and reduced secretion of its hormones. This leads to reduced fertility, decrease growth, and atrophy of gonads [48]. The shed Klotho has also been found to stimulate growth hormone secretion [49].

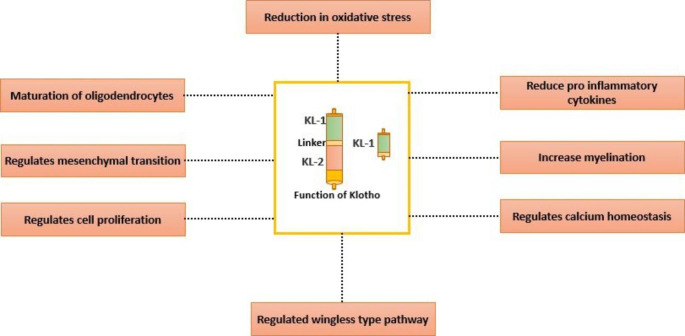

Fig. 2.

Role of Klotho in regulation of various metabolic processes in conjunction to Brain

Neuropsychiatry Disorders

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a severe neuropsychiatric disorder affecting 1% of the population worldwide. The three types of symptoms occurring in Schizophrenia are positive, negative symptoms, and cognitive decline [50–52]. Schizophrenia is characterized by redox imbalance leading to oxidative stress, resulting in the prefrontal cortex’s dysfunction and dysconnectivity. This is attributed to decreased antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase and superoxide dismutase in schizophrenia patients [53–58]. Morar et al. showed that increased levels of Klotho protein in heterozygous klotho gene variants lead to improved cognition resulting in better learning and memory. The study also demonstrated the association between the heterozygous klotho variant and an increase in the right prefrontal cortex volume, which usually decreases in size with aging [59]. Schizophrenia is also characterized by a reduction in myelin formation by oligodendrocytes leading to a more severe cognitive deficit. The maturation of oligodendrocytes from their precursor by neuronal activity is decreased in Schizophrenia [60–64]. The oxidative stress, in the brain of schizophrenia patients, occurs mainly because of dopamine metabolism, which leads to both non-enzymatic and enzymatic (monoamine oxidase) production of hydrogen peroxide in the brain. There is reduced Glutathione antioxidant and Klotho protein in genetically predisposed individuals, which leads to damage to the brain [65].

The Klotho protein has been demonstrated to affect oxidative stress and oligodendrocyte maturation. The increased Klotho protein levels accelerate the development of oligodendrocytes from its precursor. This facilitates an increased formation of myelin leading to better cognition and behavior. Further, by decreasing oxygen free radicals, Klotho protein prevents the development of oxidative stress [14–17, 19, 66]. The effect of Klotho protein on oxidative stress and maturation of oligodendrocytes indicates the possible crucial role that Klotho may have in Schizophrenia.

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE)

TLE is characterized by generalized and focal seizures, with an incidence of 10.4 per 100,000 in developed countries and slightly higher in developing countries [66]. The seizures are initiated in the brain’s temporal area and are less responsive to anticonvulsant drugs [44]. Klotho protein levels were found to be decreased in patients with TLE [60, 67]. TLE is characterized by intractable seizures due to the presence of hippocampal sclerosis [67]. Hippocampal sclerosis is the thickening or stiffening of tissues of the hippocampal area [68]. It is accompanied by an increase in astrocytes and leads to inflammation in neurons [69]. Neuroinflammation occurs due to the cytokine tumour necrosis factor (TNF), which leads to the death of neurons in the hippocampal area [11, 69–72]. An increase in glutamate to toxic levels and an increase in intracellular calcium levels are also postulated as causes of epilepsy [72, 73]. Klotho protein increases the expression of excitatory amino acid transporter (EAAT), which leads to the uptake of excitatory amino acids like glutamate from the synaptic cleft to the neurons and decreases excitation. Therefore, an increased Klotho protein level has beneficial effects in patients with TLE [73].

Apart from above mentioned, Klotho protein also decreases neuroinflammation; this occurs by reducing the activation of NF-kB, which is activated by TNF-α [74]. Further, the Klotho protein regulates calcium homeostasis through the Fibroblast growth factor 23; high levels of Klotho protein lead to a decrease in neuronal cell death in the hippocampal area [75, 76]. These aforementioned mechanisms indicate the protective role Klotho might have in patients with TLE.

Depression, psychosocial stress, and bipolar disorder

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) show a reduction in the size of the hippocampus [77]. In Klotho deficient mice, the compactness of synapses and the manifestations of oxidative stress were found to be decreased. Klotho protein decreases oxygen free radicals and prevents oxidative stress. Further, Klotho protein administration leads to the abolition of the decrease in memory due to synapses’ compactness [78]. In addition, Paroni et al. showed that patients with one mutated allele in rs1207568 of klotho showed a significantly higher response to treatment with SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake inhibitor) compared to homozygous for rs9536314 allele [79].

Environmental factors like psychosocial stress also lead to a decrease in Klotho protein levels along with aging. These low levels lead to diseases frequently found in the elderly, viz. depression, osteoporosis, and coronary artery disease. Parther et al. had shown that stress in caregiver mothers of children suffering from autistic disorder leads to lower levels of Klotho protein resulting in depression [80]. Barbosa et al. demonstrated the alteration in a pathway related to Klotho protein in bipolar disorder leading to endothelial dysfunction and decreased antioxidative mechanism [81]. In other neuropsychiatric disorders like Anorexia nervosa (AN), the effect of Klotho on IGF-1 to increased muscle mass, bone growth, and protein synthesis, as shown in an animal study, may have potential benefits [82].

Fig. 3.

Dysregulation of Klotho levels and its activity in various Neuropsychiatric disorders

Table 1.

Studies depicting the change in KLOTHO levels in various Neuropsychiatric diseases

| Sr. no. | Study organism | Disease | KLOTHO levels | Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mice and Human | Schizophrenia | Decreased | Decreased cognition | [2, 59] |

| 2 | Human | Temporal lob e epilepsy | Decreased | Increased incidence of epilepsy | [66, 67] |

| 3 | Human | Depression | Decreased | Increased depressive symptoms | [77, 78] |

| 4 | Human | Psychosocial stress | Decreased | Leads to increased aging like pathologies | [80] |

| 5 | Human | Bipolar disorder | Increased | KLOTHO levels increased with progression of disease | [80, 81] |

Klotho as a Biomarker

The role of Klotho as a prognostic biomarker has been explored in multiple diseases like Chronic Kidney disease and malignancies [83–85]. However, few studies have investigated the diagnostic and prognostic efficacy of Klotho in neuropsychiatric disorders. The ongoing search for novel biomarkers in neuropsychiatric disease is plagued with shortcomings such as the limited number of studies, smaller effect sizes, and the role of confounding factors [86–88]. The crucial mechanistic role that klotho plays in various neuropsychiatric diseases makes it an ideal candidate for exploring its relevance as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. Though, the limited number of studies on Klotho levels in neuropsychiatric diseases and the paradoxical trend observed in various neuropsychiatric diseases make it necessary to further understand the biological role of Klotho before exploring its diagnostic efficacy. The age-dependent biological variation in Klotho levels adds further complexity in delineating its prognostic power from clinical studies. However, the emerging evidence depicting the crucial role of Klotho makes it an attractive candidate for future research.

Conclusion

Neuropsychiatric disorder ranks third in disability-adjusted life years (DALY). DALY is a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill health, disability, or early death. Klotho acts as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protein and delays the process of aging. The Klotho protein level was found to be decreased in schizophrenia, depression, psychosocial stress, and TLE. This shows its association with these neuropsychiatric disorders. However, in bipolar disorder, Klotho levels were increased. This suggests a paradoxical role of Klotho in neuropsychiatric disorders, and more studies exploring the mechanism of action of Klotho protein can unravel the mysticism around this protein in neuropsychiatric disorders. Conclusively, it appears reasonable that Klotho activity could be protective in neuropsychiatric disorders and have to be explored for its therapeutic efficacy in these disorders.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miyoshi K, Morimura Y. Clinical Manifestations of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Springer;2010:3–18. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-53871-4.

- 2.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390(6655):45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309(5742):1829–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imura A, Tsuji Y, Murata M, Maeda R, Kubota K, Iwano A, et al. alpha-Klotho as a regulator of calcium homeostasis. Science. 2007;316(5831):1615–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1135901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CD, Podvin S, Gillespie E, Leeman SE, Abraham CR. Insulin stimulates the cleavage and release of the extracellular domain of Klotho by ADAM10 and ADAM17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(50):19796–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709805104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CD, Tung TY, Liang J, Zeldich E, Tucker Zhou TB, Turk BE, et al. Identification of cleavage sites leading to the shed form of the anti-aging protein klotho. Biochemistry. 2014;53(34):5579–87. doi: 10.1021/bi500409n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Loon EP, Pulskens WP, van der Hagen EA, Lavrijsen M, Vervloet MG, van Goor H, et al. Shedding of klotho by ADAMs in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309(4):F359–68. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00240.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiraki-Iida T, Aizawa H, Matsumura Y, Sekine S, Iida A, Anazawa H, et al. Structure of the mouse klotho gene and its two transcripts encoding membrane and secreted protein. FEBS Lett. 1998;424(1–2):6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito K, Ishizaka N, Mitani H, Ohno M, Nagai R. Iron chelation and a free radical scavenger suppress angiotensin II-induced downregulation of klotho, an anti-aging gene, in rat. FEBS Lett. 2003;551(1–3):58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00894-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Q, Lin S, Tang R, Veeraragoo P, Peng W, Wu R. Role of Fosinopril and Valsartan on Klotho Gene Expression Induced by Angiotensin II in Rat Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2010;33(3):186–92. doi: 10.1159/000316703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Liu Y, Wang K, Huang Y, Han W, Xiong J, et al. Klotho is regulated by transcription factor Sp1 in renal tubular epithelial cells. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12860-020-00292-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno JA, Izquierdo MC, Sanchez-Niño MD, Suárez-Alvarez B, Lopez-Larrea C, Jakubowski A, et al. The inflammatory cytokines TWEAK and TNFα reduce renal klotho expression through NFκB. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1315–25. doi: 10.1681/asn.2010101073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Regulation of NF-κB by TNF family cytokines. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(3):253–66. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asai O, Nakatani K, Tanaka T, Sakan H, Imura A, Yoshimoto S, et al. Decreased renal α-Klotho expression in early diabetic nephropathy in humans and mice and its possible role in urinary calcium excretion. Kidney Int. 2012;81(6):539–47. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi BH, Kim CG, Lim Y, Lee YH, Shin SY. Transcriptional activation of the human Klotho gene by epidermal growth factor in HEK293 cells; role of Egr-1. Gene. 2010;450(1–2):121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster RE, Jurutka PW, Hsieh JC, Haussler CA, Lowmiller CL, Kaneko I, et al. Vitamin D receptor controls expression of the anti-aging klotho gene in mouse and human renal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414(3):557–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang H, Li Y, Fan Y, Wu J, Zhao B, Guan Y, et al. Klotho is a target gene of PPAR-gamma. Kidney Int. 2008;74(6):732–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Zheng F. PPAR-gamma and aging: one link through klotho? Kidney Int. 2008;74(6):702–4. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narumiya H, Sasaki S, Kuwahara N, Irie H, Kusaba T, Kameyama H, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors up-regulate anti-aging klotho mRNA via RhoA inactivation in IMCD3 cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64(2):331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuwahara N, Sasaki S, Kobara M, Nakata T, Tatsumi T, Irie H, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibition improves anti-aging klotho protein expression and arteriosclerosis in rats with chronic inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis. Int J Cardiol. 2008;123(2):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugiura H, Yoshida T, Mitobe M, Shiohira S, Nitta K, Tsuchiya K. Recombinant human erythropoietin mitigates reductions in renal klotho expression. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32(2):137–44. doi: 10.1159/000315864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang R, Zhou QL, Ao X, Peng WS, Veeraragoo P, Tang TF. Fosinopril and losartan regulate klotho gene and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase expression in kidneys of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2011;34(5):350–7. doi: 10.1159/000326806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tataranni T, Biondi G, Cariello M, Mangino M, Colucci G, Rutigliano M, et al. Rapamycin-induced hypophosphatemia and insulin resistance are associated with mTORC2 activation and Klotho expression. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(8):1656–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almeida OP, Morar B, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Jablensky A, et al. Longevity Klotho gene polymorphism and the risk of dementia in older men. Maturitas. 2017;101:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yokoyama JS, Marx G, Brown JA, Bonham LW, Wang D, Coppola G, et al. Systemic klotho is associated with KLOTHO variation and predicts intrinsic cortical connectivity in healthy human aging. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017;11(2):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s11682-016-9598-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Vries CF, Staff RT, Noble KG, Muetzel RL, Vernooij MW, White T, et al. Klotho gene polymorphism, brain structure and cognition in early-life development. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020;14(1):213–25. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9990-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belloy ME, Napolioni V, Han SS, Le Guen Y, Greicius MD, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Association of Klotho-vs heterozygosity with risk of alzheimer disease in individuals who carry apoe4. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(7):849–62. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erickson CM, Schultz SA, Oh JM, Darst BF, Ma Y, Norton D, et al. KLOTHO heterozygosity attenuates APOE4-related amyloid burden in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2019;92(16):e1878–89. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000007323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pereira RMR, Freitas TQ, Franco AS, Takayama L, Caparbo VF, Domiciano DS, et al. KLOTHO polymorphisms and age-related outcomes in community-dwelling older subjects: The São Paulo Ageing & Health (SPAH) Study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8574. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65441-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Z, Xia W, Cui Y, Zeng F, Li Y, Yang Z, et al. Klotho gene polymorphisms are associated with healthy aging and longevity: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Mech Ageing Dev. 2019;178:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao Q, Ding X, Gao L, Yang M, Dong B. G-395A polymorphism in the promoter region of the KLOTHO gene associates with reduced cognitive impairment among the oldest old. Age (Dordr) 2016;38(1):7. doi: 10.1007/s11357-015-9869-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Zhao X, Daskalakis NP, Morrison FG, Escarfulleri S, et al. PTSD and the klotho longevity gene: Evaluation of longitudinal effects on inflammation via DNA methylation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;117:104656. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin S, Zhang Q, Yang J, Lin W, Li Y, Chen F, et al. TGFβ-incurred epigenetic aberrations of miRNA and DNA methyltransferase suppress Klotho and potentiate renal fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864(7):1207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagai T, Yamada K, Kim HC, Kim YS, Noda Y. Cognition impairment in the genetic model of aging klotho gene mutant mice: a role of oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2003;17(1):50–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0448fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao NM, Zhang YM, Zheng Q, Gu J. Klotho is a serum factor related to human aging. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004;117(5):742–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinton SM, Glover ME, Maltare A, Laszczyk AM, Mehi SJ, Simmons RK, et al. Expression of klotho mRNA and protein in rat brain parenchyma from early postnatal development into adulthood. Brain Res. 2013;1527:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li SA, Watanabe M, Yamada H, Nagai A, Kinuta M, Takei K. Immunohistochemical localization of Klotho protein in brain, kidney, and reproductive organs of mice. Cell Struct Funct. 2004;29(4):91–9. doi: 10.1247/csf.29.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.German DC, Khobahy I, Pastor J, Kuro-O M, Liu X. Nuclear localization of Klotho in brain: an anti-aging protein. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(7):1483.e25-30. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King GD, Rosene DL, Abraham CR. Promoter methylation and age-related downregulation of Klotho in rhesus monkey. Age (Dordr) 2012;34(6):1405–19. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9315-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lun MP, Monuki ES, Lehtinen MK. Development and functions of the choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(8):445–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duce JA, Podvin S, Hollander W, Kipling D, Rosene DL, Abraham CR. Gene profile analysis implicates Klotho as an important contributor to aging changes in brain white matter of the rhesus monkey. Glia. 2008;56(1):106–17. doi: 10.1002/glia.20593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laszczyk AM, Fox-Quick S, Vo HT, Nettles D, Pugh PC, Overstreet-Wadiche L, et al. Klotho regulates postnatal neurogenesis and protects against age-related spatial memory loss. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;59:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen CD, Li H, Liang J, Hixson K, Zeldich E, Abraham CR. The anti-aging and tumor suppressor protein Klotho enhances differentiation of a human oligodendrocytic hybrid cell line. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;55(1):76–90. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0336-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen CD, Sloane JA, Li H, Aytan N, Giannaris EL, Zeldich E, et al. The antiaging protein Klotho enhances oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination of the CNS. J Neurosci. 2013;33(5):1927–39. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2080-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeldich E, Chen CD, Avila R, Medicetty S, Abraham CR. The Anti-Aging Protein Klotho Enhances Remyelination Following Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;57(2):185–96. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiozaki M, Yoshimura K, Shibata M, Koike M, Matsuura N, Uchiyama Y, et al. Morphological and biochemical signs of age-related neurodegenerative changes in klotho mutant mice. Neuroscience. 2008;152(4):924–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubal DB, Zhu L, Sanchez PE, Worden K, Broestl L, Johnson E, et al. Life extension factor klotho prevents mortality and enhances cognition in hAPP transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2015;35(6):2358–71. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5791-12.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toyama R, Fujimori T, Nabeshima Y, Itoh Y, Tsuji Y, Osamura RY, et al. Impaired regulation of gonadotropins leads to the atrophy of the female reproductive system in klotho-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147(1):120–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shahmoon S, Rubinfeld H, Wolf I, Cohen ZR, Hadani M, Shimon I, et al. The aging suppressor klotho: a potential regulator of growth hormone secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307(3):E326–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00090.2014.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medalia A, Saperstein AM. Does cognitive remediation for schizophrenia improve functional outcomes. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(2):151–7. doi: 10.1097/yco.0b013e32835dcbd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lystad JU, Falkum E, Haaland V, Bull H, Evensen S, McGurk SR, et al. Cognitive remediation and occupational outcome in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A 2year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2017;185:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB, Schizophrenia Lancet. 2016;388(10039):86–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reyazuddin M, Azmi SA, Islam N, Rizvi A. Oxidative stress and level of antioxidant enzymes in drug-naive schizophrenics. Indian J Psychiatry. 2014;56(4):344–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.146516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang XY, Chen DC, Tan YL, Tan SP, Wang ZR, Yang FD, et al. The interplay between BDNF and oxidative stress in chronic schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:201–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarandol A, Sarandol E, Acikgoz HE, Eker SS, Akkaya C, Dirican M. First-episode psychosis is associated with oxidative stress: Effects of short-term antipsychotic treatment. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(11):699–707. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miyaoka T, Ieda M, Hashioka S, Wake R, Furuya M, Liaury K, et al. Analysis of oxidative stress expressed by urinary level of biopyrrins and 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(11):693–8. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dietrich-Muszalska A, Kwiatkowska A. Generation of superoxide anion radicals and platelet glutathione peroxidase activity in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:703–9. doi: 10.2147/ndt.S60034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gonzalez-Liencres C, Tas C, Brown EC, Erdin S, Onur E, Cubukcoglu Z, et al. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia: a case-control study on the effects on social cognition and neurocognition. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:268. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0268-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morar B, Badcock JC, Phillips M, Almeida OP, Jablensky A. The longevity gene Klotho is differentially associated with cognition in subtypes of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baumann N, Pham-Dinh D. Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(2):871–927. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang A, Nishiyama A, Peterson J, Prineas J, Trapp BD. NG2-positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in adult human brain and multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurosci. 2000;20(17):6404–12. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.20-17-06404.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rivers LE, Young KM, Rizzi M, Jamen F, Psachoulia K, Wade A, et al. PDGFRA/NG2 glia generate myelinating oligodendrocytes and piriform projection neurons in adult mice. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(12):1392–401. doi: 10.1038/nn.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mensch S, Baraban M, Almeida R, Czopka T, Ausborn J, El Manira A, et al. Synaptic vesicle release regulates myelin sheath number of individual oligodendrocytes in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(5):628–30. doi: 10.1038/nn.3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gibson EM, Purger D, Mount CW, Goldstein AK, Lin GL, Wood LS, et al. Neuronal activity promotes oligodendrogenesis and adaptive myelination in the mammalian brain. Science. 2014;344(6183):1252304. doi: 10.1126/science.1252304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bošković M, Vovk T, KoresPlesničar B, Grabnar I. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(2):301–12. doi: 10.2174/157015911795596595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Téllez-Zenteno JF, Hernández-Ronquillo L. A review of the epidemiology of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2012;2012:630853. doi: 10.1155/2012/630853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Teocchi MA, Ferreira A, da Luz de Oliveira EP, Tedeschi H, D’Souza-Li L. Hippocampal gene expression dysregulation of Klotho, nuclear factor kappa B and tumor necrosis factor in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:53. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Margaret M, Esiri SA, Chance J, Debarros, Tim J Crow. Psychiatric Diseases. Greenfield’s Neuropathology. 6th edition. London: Arnold; 1997. ISBN 9781498721288.

- 69.Foresti ML, Arisi GM, Shapiro LA. Role of glia in epilepsy-associated neuropathology, neuroinflammation and neurogenesis. Brain Res Rev. 2011;66(1–2):115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vezzani A, Friedman A. Brain inflammation as a biomarker in epilepsy. Biomark Med. 2011;5(5):607–14. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ravizza T, Balosso S, Vezzani A. Inflammation and prevention of epileptogenesis. Neurosci Lett. 2011;497(3):223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Delorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS. Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintainance of epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105(3):229–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Choi DW. Glutamate neurotoxicity and diseases of the nervous system. Neuron. 1988;1(8):623–34. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Almilaji A, Munoz C, Pakladok T. Klotho suppresses TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in the endothelium and attenuates NF-kappaB activation. Endocrine. 2009;35(3):341–6. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maekawa Y, Ishikawa K, Yasuda O. Klotho suppresses TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in the endothelium and attenuates NF-kappaB activation. Endocrine. 2009;35(3):341–6. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, Shimada T, Iijima K, Hasegawa H, Okawa K, et al. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature. 2006;444(7120):770–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M. Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(10):6120–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500457200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stockmeier CA, Mahajan GJ, Konick LC, Overholser JC, Jurjus GJ, Meltzer HY, et al. Cellular changes in the postmortem hippocampus in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(9):640–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kuro-o M. Klotho as a regulator of oxidative stress and senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389(3):233–41. doi: 10.1515/bc.2008.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paroni G, Seripa D, Fontana A. Klotho Gene and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors: Response to Treatment in Late-Life Major Depressive Disorder. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(2):1340–51. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9711-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prather AA, Epel ES, Arenander J. Longevity factor klotho and chronic psychological stress. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5(6):e585. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barbosa IG, Rocha NP, Alpak G. Klotho dysfunction: A pathway linking the aging process to bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:80–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rubinek T, Modan-Moses D. Klotho and the Growth Hormone/Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1 Axis: Novel Insights into Complex Interactions. Vitam Horm. 2016;101:85–118. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mao S, Wang X, Wu L, Zang D, Shi W. Association between klotho expression and malignancies risk and progression: A meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;484:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tomo S, Birdi A, Yadav D, Chaturvedi M, Sharma P. Klotho: A Possible Role in the Pathophysiology of Nephrotic Syndrome. EJIFCC. 2022;33(1):3–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu QF, Yu LX, Feng JH, Sun Q, Li SS, Ye JM. The Prognostic Role of Klotho in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dis Markers. 2019:6468729. doi:10.1155/2019/6468729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Bora E. Peripheral inflammatory and neurotrophic biomarkers of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(12):1971–9. doi: 10.1017/s0033291719001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.da Rosa MI, Simon C, Grande AJ, Barichello T, Oses JP, Quevedo J. Serum S100B in manic bipolar disorder patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]