Abstract

Direct air capture of carbon dioxide is a viable option for the mitigation of CO2 emissions and their impact on global climate change. Conventional processes for carbon capture from ambient air require 230 to 800 kJ thermal per mole of CO2, which accounts for most of the total cost of capture. Here, we demonstrate electrochemical direct air capture using neutral red as a redox-active material in an aqueous solution enabled by the inclusion of nicotinamide as a hydrotropic solubilizing agent. The electrochemical system demonstrates a high electron utilization of 0.71 in a continuous flow cell with an estimated minimum work of 35 kJe per mole of CO2 from 15% CO2. Further exploration using ambient air (410 ppm CO2 in the presence of 20% oxygen) as a feed gas shows electron utilization of 0.38 in a continuous flow cell to provide an estimated minimum work of 65 kJe per mole of CO2.

Subject terms: Carbon capture and storage, Chemical engineering

Electrochemical direct air capture (DAC) of CO2 requires air-stable redox-active materials. Here, the authors present an electrochemical DAC using air-stable redox couple of neutral red with a minimum energy requirement of 65 kJe/molCO2.

Introduction

Increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration owing to the burning of fossil fuels is considered the major factor in recent global warming and climate change1. The atmospheric CO2 concentration has increased continuously from the preindustrial level of 280 ppm to 410 ppm in 2021, induced by human activities which currently emit close to 40 billion tons of CO2 annually2. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies have been recognized as one of the important strategies to slow down changes in global climate patterns by effectively lowering CO2 discharges3. Conventional CO2 capture has addressed CO2 emissions from large point sources, such as fossil-fuel power stations and chemical plants. Since a considerable portion of CO2 emissions is derived from mobile sources (e.g., 29% from transportation), direct air capture (DAC), in which CO2 is captured directly from ambient air, is considered to be an important and viable option for reducing atmospheric CO2 levels4. While there are advantages of DAC in its potential to address emissions from distributed sources, the development and application of DAC processes have been restricted by their high operation cost. Currently, the energy requirements of the leading DAC technologies are ~500 to 800 kJ thermal per mole of CO2 using sodium hydroxide scrubbing/lime causticization systems5 and ~238 to 317 kJ thermal per mole of CO2 using amine-functionalized solid sorbents6. Recent analyses suggest that the energy requirement target should be less than 400 kJ thermal per mole of CO2 (equivalent to 120 kJ/mol of electrical energy with Carnot efficiency of 0.3) by CO2-neutral power sources to be viable in order to be CO2 negative5.

To overcome these limitations of high energy requirements encountered by the systems using thermal energy, electrochemical systems have come to be recognized as a feasible option due to their potentially lower energy consumption under milder conditions of room temperature and pressure, as highlighted in recent review articles (Supplementary Table 1)7,8. Such electrochemical systems are based on pH swing8–11 and reversible redox-active capturing agents12–21. Most systems involving redox-active capture agents suffer from oxygen sensitivity which hampers their larger-scale application9,22. In this regard, our group has been searching for oxygen-insensitive redox-active compounds that can capture CO2 under highly dilute conditions (i.e., ambient air).

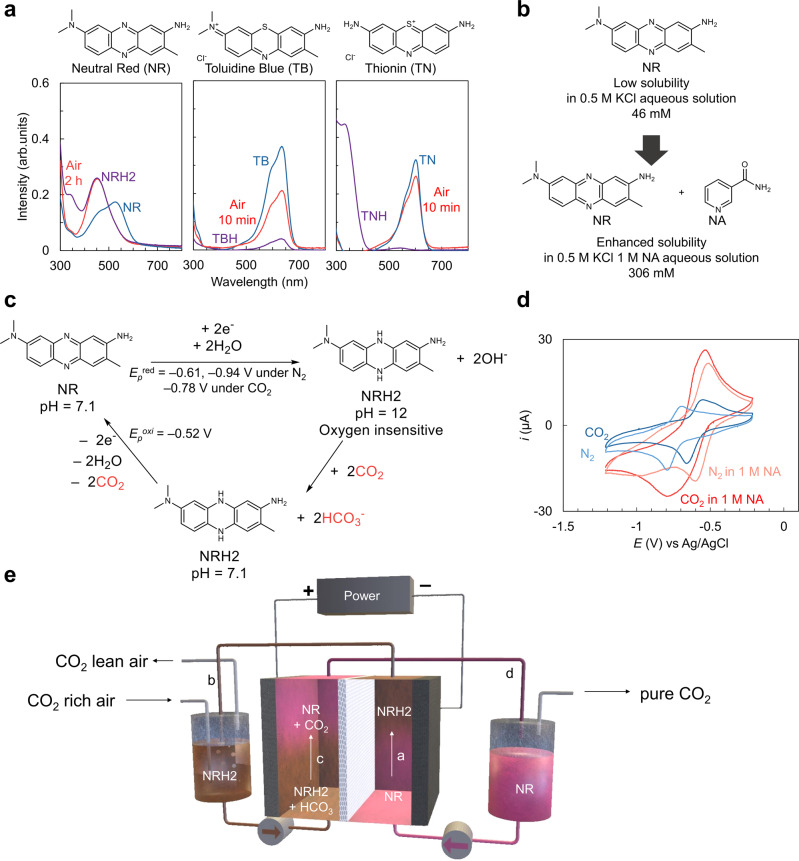

Phenazines and phenothiazines are electron-rich heterocyclic organic π-systems that often favorably fulfill the requirements of organic redox-active compounds with their reversibility in aqueous systems. In this respect, there has been extensive research employing phenazine and phenothiazine derivatives in redox-flow batteries23 and electrochemical carbon capture9,10,24 via proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) in aqueous systems. Although several efforts to engage these compounds in electrochemical direct air capture with potentially low energy consumption have been reported, these systems suffered from oxygen sensitivity and required synthetic modification to overcome low aqueous solubility9,10. For these reasons, none of the phenazine- and phenothiazine-based systems was reported to demonstrate capture of CO2 from ambient air, to the best of our knowledge. Direct air capture using a reversible electrochemical system with low energy consumption benefiting from the reversible PCET redox couples in an aqueous solution can be achieved by eliminating oxygen sensitivity of the redox-active compound and enhancing its aqueous solubility. Here, we report electrochemical direct air capture of CO2 using neutral red (NR), a commercial organic dye molecule, as an oxygen-insensitive organic redox-active compound (Fig. 1a) in the presence of nicotinamide (NA) as a hydrotropic agent to increase its solubility in the aqueous system (Fig. 1b)25. Other commercial phenothiazine compounds such as toluidine blue (TB), and thionin (TN) could not satisfy the need for oxygen insensitivity (Fig. 1a), and therefore were not considered further for this task. The minimum energy requirements are estimated to be 35 kJe/mol of CO2 with a 15% CO2 feed, and 65 kJe/mol for direct air capture.

Fig. 1. Electrochemical carbon capture using a redox pair of NR/NRH2 in an aqueous solution.

a UV–vis spectra for neutral red (NR), toluidine blue (TB), and thionin (TN) in an aqueous solution during tests for air sensitivity. Solutions containing the reduced organic dye compounds (50 mM, 1 mL) were bubbled with air for 10 min (TBH, TNH) or 2 h (NRH2) at a flow rate of 3 mL/min. NRH2 leuco-neutral red, TBH leuco-toluidine blue, TNH leuco-thionin. b NR solubility enhancement in water with the inclusion of 1 M nicotinamide (NA) as a hydrotropic agent. KCl potassium chloride. c Scheme of the reversible electrochemical CO2 capture and release using the NR/NRH2 redox system in water. Potentials are versus Ag/AgCl. d The cyclic voltammograms of 5 mM NR under nitrogen (pastel blue curve, pH 6) and CO2 (blue curve, pH 7) in water with 0.1 M lithium perchlorate (LiClO4) as a supporting electrolyte, and those of 10 mM NR under nitrogen (pastel red curve, pH 6) and CO2 (red curve, pH 7) in water with 1 M NA as a hydrotropic agent and 0.1 M LiClO4 as a supporting electrolyte. All CV curves were recorded at room temperature at a scan rate of 50 mV/s with a glassy carbon working electrode. Potentials were recorded versus Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode. e Overview of the continuous flow electrochemical cell with the NR/NRH2 redox cycle for CO2 capture and release experiments.

The proposed working scheme for electrochemical carbon capture by the NR/leuco-neutral red (NRH2) redox system is illustrated in Fig. 1c. NRH2, the reduced product from NR, was formed on application of a suitable electrochemical potential with basification of the aqueous solution to pH 12 (experimentally obtained). Then the CO2-rich gas stream was introduced to saturate and consequently acidify the solution. Subsequent electrochemical oxidation of the CO2-saturated solution regenerated NR and released free CO2. The conjugate base NR would mainly participate in the redox process because the system operates in the pH range of 6–12. The amount of hydroxide ion formed by electrochemical reduction of the NR/NRH equilibrium (pKa = 6.8)26 mixture can be estimated to be 1.2 to 1.67 equivalent depending on the pH values of the starting solutions (Supplementary equations 1–4).

Although the aqueous solubilities of phenazines and phenothiazines would be low in electrolyte solutions, the inclusion of 1 M of NA as a hydrotropic agent, which is often used to increase the water solubility of pharmaceuticals25, can increase the solubility of NR in 0.5 M potassium chloride (KCl) aqueous solution from 46 mM to 306 mM (Fig. 1b). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves recorded to compare the redox activity of NR/NRH2 in 1 M NA solution to those in the absence of NA under 1 atm N2 and 1 atm CO2 atmospheres are shown in Fig. 1c, where the first set of CV curves obtained in the absence of NA is displayed in blue curves. Under the N2 atmosphere, NR showed a cathodic peak at –0.78 V vs Ag/AgCl and an anodic peak at –0.68 V vs Ag/AgCl (pastel blue curve). When the electrolyte solution was saturated with CO2, the voltammogram showed a positively shifted single cathodic peak at –0.65 V and an anodic peak at –0.54 V (blue curve). The second set of CV curves, shown in red, were recorded in the presence of NA. Under the N2 atmosphere, two sets of cathodic and anodic peaks appeared at –0.60 V and –0.50 V and at –0.97 V and –0.82 V, respectively (pastel red curve). These are attributed to the stepwise two single-electron transfers27. When the CO2 was introduced to the electrolyte solution with adjustment of the pH value to pH 7, the two cathodic peaks merged to show a single peak at –0.78 V with slight shifts in the two anodic peaks to –0.61 V and –0.52 V, respectively (red curve). CV curves of NR show quasi-reversibility in the redox activity of NR/NRH2 in the presence and absence of NA. The electrochemical carbon capture system in this manuscript was demonstrated using a 50 mM NR solution in the presence of 1 M NA as a hydrotropic agent.

In this manuscript, we describe continuous flow electrochemical CO2 capture with the NR/NRH2 redox system (Fig. 1d). NR was reduced electrochemically to provide NRH2 with an increase in the pH of the solution (path a). The basic aqueous solution was pumped to the reservoir where an air or CO2-rich gas stream was introduced (path b). The CO2-saturated solution was then pumped to the anodic chamber where electrochemical oxidation led to regeneration of NR and release of free CO2 (path c). Then the resulting solution was transferred to the anolyte reservoir to discharge CO2 and close the flow cycle (path d). The continuous operation of the flow cell was demonstrated with 15% CO2 and ambient air.

Results

Cyclic voltammetry of NR

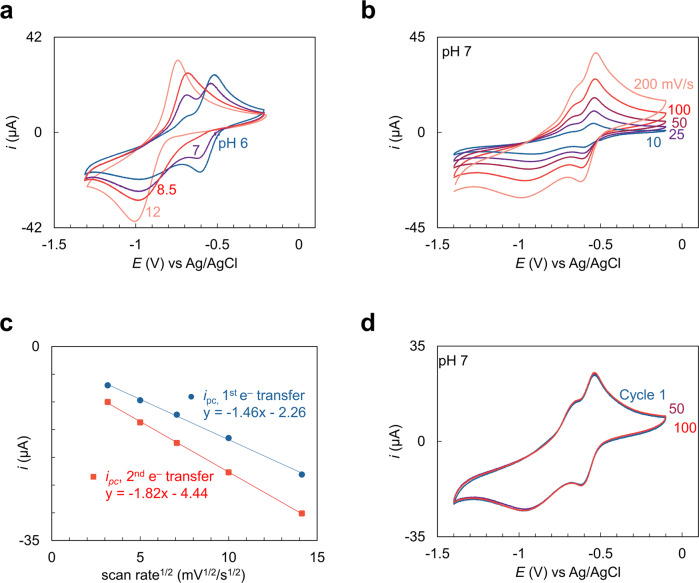

The electrochemistry of the NR aqueous solution was examined by CV at various pH levels between 6 and 12 (Fig. 2a). Two sets of peaks were observed, corresponding to the first and second single-electron transfers to NR via an H e e H mechanism27. The first single-electron reduction peak appears at –0.61 V with the second reduction peak at –0.94 V and two single-oxidation peaks at –0.68 V and –0.52 V vs Ag/AgCl at pH 6. As the solution pH increases, the first single-electron reduction peak decreases and merges with the second electron transfer peak, which is consistent with the H e e H mechanism. The peak currents (ipc) in the CVs shown in Fig. 2b for the first and second single-electron reductions vary linearly with the square root of the scan rate (Fig. 2c) at pH 7, the differences in slope indicating that the first reduction is kinetically slower than the second reduction, which also supports the H e e H mechanism at pH>pKa. Based on the experimental pH measurement at each step and results from the CV experiment in Figs. 1c, 2a the minimum potential gap for the electrochemical swing process should be 0.42 V for the first cycle without CO2 around during reduction. The minimum potential gap of 0.26 V in the cyclic system in which CO2 is dissolved in the solution is smaller based on the CV in Fig. 1c. The merging of the first and second reduction peaks in the presence of CO2 suggests that pre-association of CO2 and NR would facilitate electron transfer. The NR/NRH2 redox reaction demonstrates good reversibility and excellent redox durability, with no significant decay in the peak current after 100 CV cycles (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. Cyclic voltammetry of NR in aqueous solutions.

a The cyclic voltammograms of 10 mM NR at pH 6 (blue), 7 (purple), 8.5 (red), and 12 (pastel red) in 1 M NA and 0.1 M LiClO4 solutions under nitrogen with a glassy carbon working electrode, at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. Potentials were recorded versus Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode. b Cyclic voltammograms of NR with scan rates of 10 (blue), 25 (purple), 50 (dark red), 100 (red), and 200 mV/s (pastel red). c Analysis of NR redox reaction of peak current (ipc) versus the square root of scan rate (v1/2) for the first (blue) and second reduction peaks (red). d 100 cyclic voltammograms of NR. Cycle 1: blue, cycle 50: purple, cycle 100: red.

Electrochemical release of CO2 using the NR/NRH2 redox system

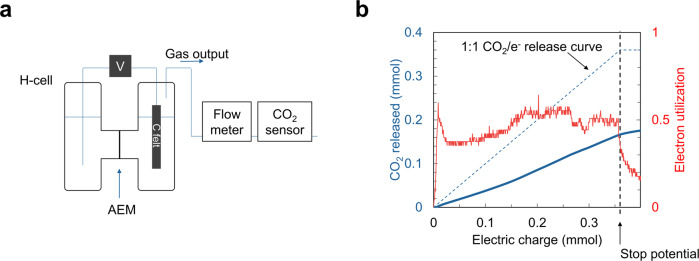

A bench-scale setup using an electrochemical H-cell was constructed for CO2 capture and release in the NR/NRH2 redox system (Fig. 3a). The system was equipped with an anion exchange membrane separating two 5 mL reaction chambers, carbon felt as a working electrode, and a stainless-steel wire electrode for an arbitrary reaction in the counter chamber. The 4 mL reaction mixture containing 50 mM NR (200 mmol) in water in the presence of 1 M NA as a hydrotropic agent and 0.5 M LiClO4 as a supporting electrolyte was electrochemically reduced in a constant current mode at 50 mA for 695 s (equivalent to 360 mmol of electrons transferred) to yield 90% reduction of the NR to NRH2. Then a 15% CO2 gas stream was introduced for 10 min to saturate the solution. The output gas flow from the CO2-saturated solution upon anodic oxidation was quantified and qualified by a CO2 flow meter and an FT-IR CO2 sensor, respectively. Plots of the amount of CO2 released by electrochemical oxidation versus electric charge are displayed in Fig. 3b. The electron utilization for the CO2 release by oxidation represents the ratio between the moles of CO2 released per mole of electrons transferred. CO2 release at an electron utilization of 0.50 was obtained, accounting for the delayed release of CO2 from the cell. Combining the voltage difference (0.42 V) between the peak potentials from the CV measurements with the electrochemical electron utilization of 0.50 during CO2 release, we estimated that the minimum energy requirement of 81 kJe/mol in batch (Supplementary equations 5 and 6).

Fig. 3. Electrochemical release of CO2 using the NR/NRH2 redox system.

a Schematic of the experimental setup for CO2 release. The electrochemical H-cell containing NRH2 solution to be oxidized by a constant current at room temperature was connected to a gas flow meter and an FT-IR CO2 sensor. AEM: anion exchange membrane. b Solution of 4 mL of 50 mM NRH2 was oxidized at a constant current of 50 mA. The amount of released CO2 (blue curve) and electron utilization (red curve) are shown versus the electric charge.

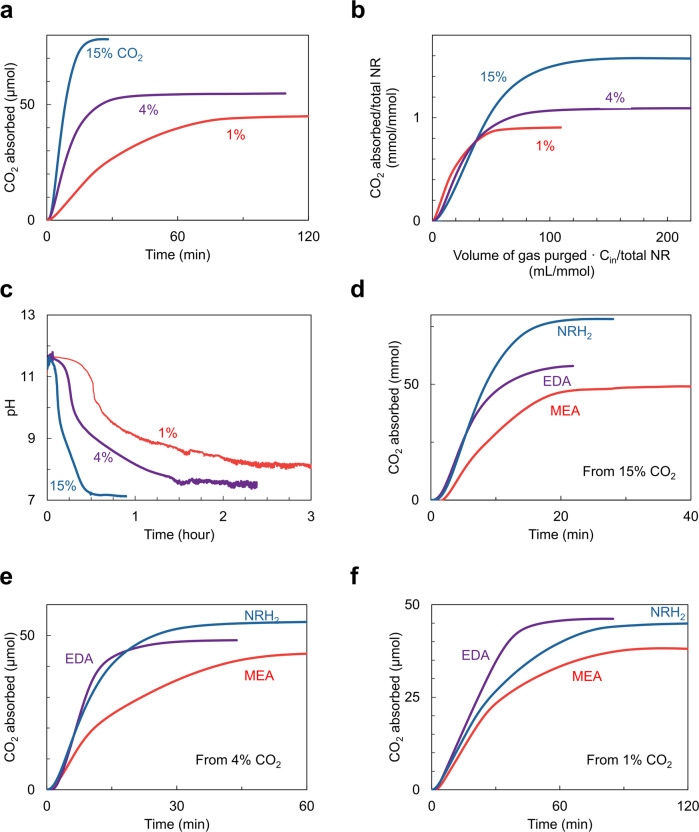

CO2 absorption dynamics of NRH2 solutions

The dynamics of CO2 absorption by 1 mL of a 50 mM NRH2 solution depended on the CO2 concentration, as shown in Fig. 4a for 1, 4, and 15% CO2 feeds. A saturation absorption of 78 µmol of CO2 in equilibrium with 15% CO2 was observed, corresponding to 1.56 equivalents to NRH2, consistent with the amount of hydroxide anion estimated (1.67 equivalent to NRH2, Supplementary equations 1–4). The CO2 absorption levels were lower with 4 and 1% CO2 gas streams, at 55 μmol (1.1 equivalents to NRH2) and 45 μmol (0.9 equivalents to NRH2), respectively. When normalized by the inlet CO2 concentration, the curves superimpose in the initial absorption period, as shown in Fig. 4b, consistent with mass transport limitations during the early stages of absorption. However, it shows lower utilization of the capacity of the solution when using lower CO2 concentrations of the inlet gas streams, as would be anticipated based on mass action kinetics. Absorption was also monitored by in situ pH measurement in 5 mL of 50 mM NRH2 solution sparged with 1, 4, and 15% CO2 stream at a flow rate of ca. 100 mL/min (Fig. 4c). The final pH value after saturation was 7.1 with 15% CO2, 7.4 with 4% CO2, and 8.1 with 1% CO2 which are consistent with the results in Fig. 4a, b. We also compared the NR CO2 absorption profiles with those of 50 mM solutions of amines ethylenediamine (EDA) and monoethanolamine (MEA), which are traditionally used for CO2 capture (Fig. 4d–f); these electrochemically inactive amines are frequently used in comparative studies of CO2 absorption28,29. The initial CO2 absorption rate in the NRH2 solution was comparable to that in EDA, but the amount of absorbed CO2 was 56% higher than that with EDA when using a 15% CO2 inlet gas stream (Fig. 4d). The absorption rate by the NRH2 solution with 4% CO2 was also as fast as that by EDA. However, the NRH2 solution shows slower absorption than EDA with the 1% CO2 gas feed. In all cases, CO2 absorption by NRH2 was faster than by the MEA solution.

Fig. 4. Dynamics of CO2 absorption by 50 mM NRH2 solutions.

a CO2 absorption profiles at CO2 inlet gas stream concentrations of 1 (red curve), 4 (purple curve), and 15% (blue curve). An aqueous 50 mM NRH2 solution was contacted with the gas at a flow rate of 3.3 mL/min at room temperature. b Normalized CO2 absorption profiles. c In situ pH measurement during CO2 bubbling. Plots of pH versus time are displayed for 5 mL of 50 mM NRH2 solution with CO2 inlet gas stream concentrations of 1 (red curve), 4 (purple curve), and 15% (blue curve) at a flow rate of 100 mL/min. d Comparison of the CO2 absorption profile with 15% CO2 for NRH2 (50 mM in 1 mL of water) to those for ethylenediamine (EDA, 50 mM in 1 mL of water) and monoethanolamine (MEA, 50 mM in 1 mL of water). A flow of 15% CO2 concentration balanced by nitrogen was used at a flow rate of 3.3 mL/min. e Comparison of the CO2 absorption profiles with 4% CO2. f Comparison of the CO2 absorption profiles with 1% CO2.

Direct air capture and stability test of NRH2 solution

Next, we investigated the potential for electrochemical direct air capture using the NR/NRH2 redox system (Fig. 5). A 45 mM NRH2 solution prepared by electrochemical reduction was contacted with non-pretreated air for 3 h at a flow rate of ca. 120 mL/min. Electrochemical oxidation of the air-contacted solution was carried out to evaluate the direct air capture efficiency (Fig. 5a). The system presented an electron utilization during CO2 release of up to 0.33, with an average value of 0.21 under the current batch conditions. On the basis of the electron utilization (0.33) during CO2 release and the potential difference obtained from the CV, the minimum work for direct air capture under the current conditions was estimated to be 123 kJe/mol (Supplementary equations 5 and 7). Although further engineering optimization is warranted, the estimated minimum energy is promising as it is in the vicinity of 400 kJ/mol thermal (equivalent to 120 kJe/mol with a Carnot efficiency of 0.3), which is considered to be the target for DAC technologies5. The absorption of CO2 during bubbling of air was monitored by in situ measurement of pH (Fig. 5b), which dropped from 12 to 9.1 in 3 h. The initial absorption rate from the ambient air was comparable to that for a 1% CO2 concentration inlet based on the pH value measurements as depicted in a normalized plot (See Supplementary Fig. 21).

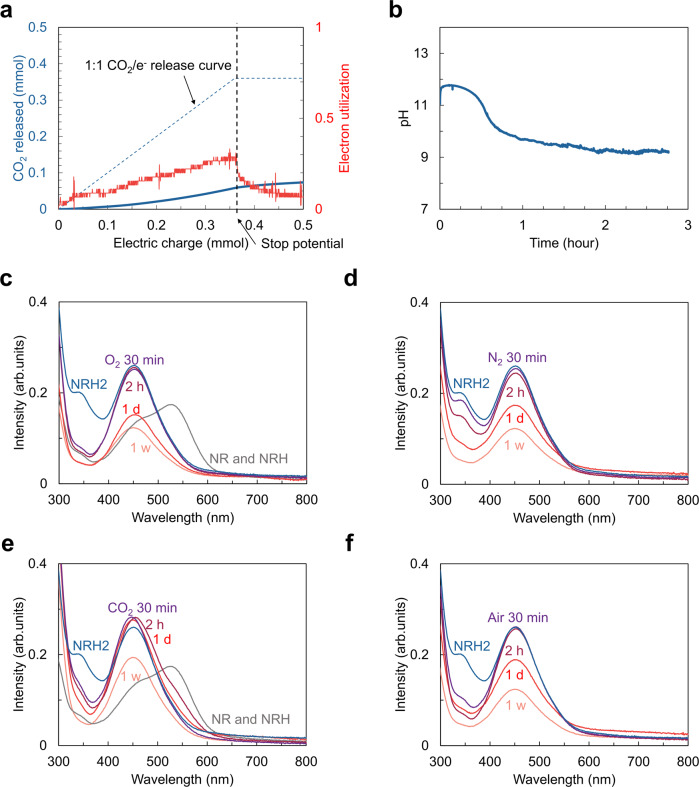

Fig. 5. Direct air capture and stability test of NRH2 solutions.

a CO2 released by electrochemical oxidation on the application of a constant current of 50 mA to the NRH2 solution (50 mM, 4 mL) bubbled with air for 3 h at a flow rate of ca. 120 mL/min. The amount of released CO2 (blue curve) and electron utilization (red curve) are shown versus electric charge. b In situ pH measurement versus time for 5 mL of 50 mM NRH2 solution bubbled with ambient air. c UV–vis spectra for the oxygen sensitivity test. The NRH2 solutions (blue curve, 50 mM, 1 mL) were bubbled with pure oxygen for 30 min (purple), 2 h (dark red), and 1 day (red) at a flow rate of 3 mL/min and sealed under oxygen for 1 week (pastel red). Gray curve represents UV–vis spectra of NR and NRH. d UV–vis spectra for the control experiment under nitrogen. The NRH2 solutions (blue curve, 50 mM, 1 mL) were bubbled with nitrogen for 30 min (purple), 2 h (dark red), and 1 day (red) at a flow rate of 3 mL/min and sealed under nitrogen for 1 week (pastel red). e UV–vis spectra for the stability test under CO2. The NRH2 solutions (blue curve, 50 mM, 1 mL) were bubbled with pure CO2 for 30 min (purple), 2 h (dark red), and 1 day (red) at a flow rate of 3 mL/min and sealed under CO2 for 1 week (pastel red). Gray curve represents UV–vis spectra of NR and NRH. f UV–vis spectra for the stability test under air. The NRH2 solutions (blue curve, 50 mM, 1 mL) were bubbled with air for 30 min (purple), 2 h (dark red), and 1 day (red) at a flow rate of 5 mL/min and sealed under air for 1 week (pastel red).

The NRH2 solution was shown to be insensitive to oxygen as observed in a set of UV–vis absorption spectroscopy experiments under various conditions (Fig. 5c–f). The 50 mM NRH2 solutions prepared by electrochemical reduction in the presence of 1 M NA and 0.5 M KCl in water were bubbled with pure oxygen, nitrogen, CO2, and ambient air for 24 h. The freshly prepared NRH2 solution showed two absorption peaks in the range of 300–800 nm by UV–vis absorption spectroscopy. The larger peak at 455 nm is attributed to the NRH2 and the smaller peak at 345 nm is presumably from the radical species27. In Fig. 5c, the peak intensity at 455 nm was maintained for 2 h when contacted with pure oxygen. Longer studies for a day and a week provided peak intensities of NRH2 lowered by 42% and 52%, respectively, in the solution sealed under an oxygen atmosphere after 24 h of bubbling with oxygen. The peak at 345 nm disappeared rapidly over 30 min on contacting oxygen. As a control experiment, we introduced nitrogen to the 50 mM NRH2 solution at the same flow rate (Fig. 5d). Initial degradation of the peak intensity at 455 nm and 345 nm was slower during the first 2 h. The peak intensity measured after 24 h and a week provided the peak intensity degradation by 33% and 53%, respectively. These results suggest that the oxygen with which the solution had been in contact did not contribute significantly to the degradation of the UV–vis peak intensity of NRH2 at 455 nm, while the 345 nm peak disappeared rapidly in reaction with oxygen. We investigated possible factors that might contribute to the 455 nm peak degradation, including decomposition, reoxidation, precipitation, and polymerization. NMR studies of the NRH2 solutions indicated that the NRH2 precipitation due to its limited solubility under the current conditions led UV–vis peak degradation (See Supplementary Fig. 22). In addition to peaks from NRH2 and NA, minor peaks potentially derived from NA were observed under O2 and N2. Although further studies are warranted on the byproduct formation pathways, we currently believe that precipitation is one of the causes of the reduced electron utilization, albeit a minor one. We believe that the solubility can be improved by the inclusion of a higher concentration of NA or a choice of supporting electrolyte. We did not observe any major decomposition, reoxidation, or polymerization products of NRH2 by NMR studies.

A third set of UV–vis absorption measurements (Fig. 5e), this time on solutions contacted with CO2, was carried out. Interestingly, no significant degradation of peak intensity at 455 nm was observed by UV–vis absorption spectroscopy after a day. These results indicated that the homogeneity of the NRH2 solution is better maintained under the CO2 atmosphere possibly due to the neutral pH of the solution. The peak at 345 nm, however, disappeared rapidly in 30 min accompanied by bumps at ~490 nm and ~550 nm, which may be due to the regeneration of NR and NRH, respectively (See Supplementary Fig. 17). Based on this result, at this point CO2 reduction by the radical species formed by electrochemical reduction under the imposed current conditions cannot be ruled out. The final set of UV–vis absorption experiments in Fig. 5f was carried out using solutions bubbled with ambient air. Although the intensities of the 455 nm peak were the same for the samples after 30 min and 2 h contact, respectively, similar levels of peak intensity degradation as observed with solutions contacted with oxygen and nitrogen were observed with longer sample storage times.

Continuous flow operation of NR/NRH2 redox system

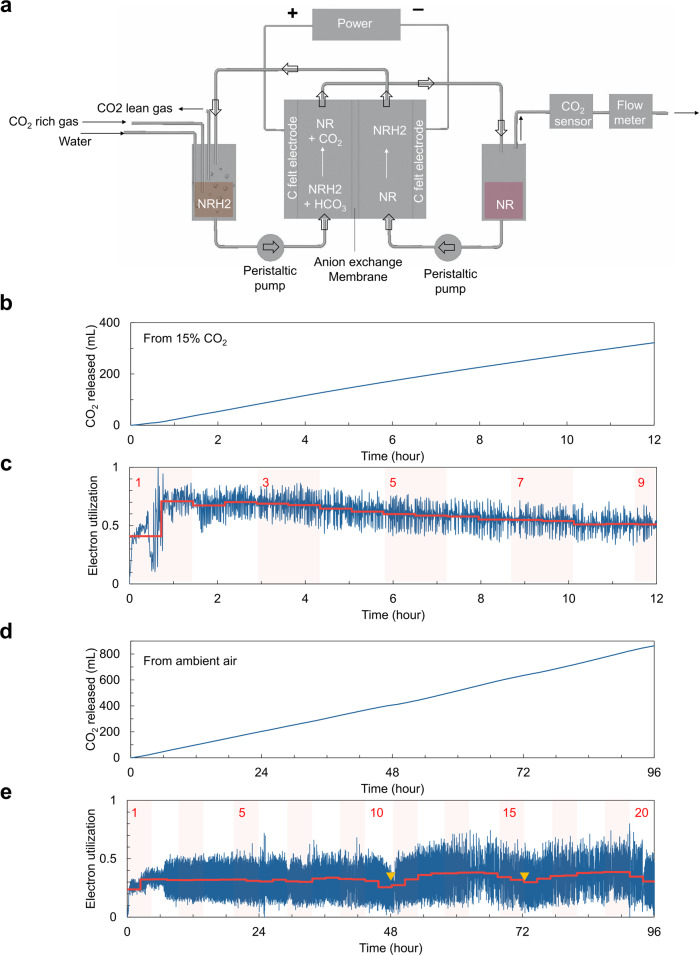

We constructed a continuous flow cell to process 50 mM NR solution in the presence of 1 M NA and 1 M KCl as a supporting electrolyte due to its better conductivity than that of LiClO4 (28.3 mS/cm in 1 M LiClO4 and 1 M NA in water vs 43.7 mS in 1 M KCl and 1 M NA in water) and higher solubility of NR in water (50 mM in 0.5 M LiClO4 and 1 M NA vs 306 mM in 0.5 M KCl and 1 M NA) to avoid potential clogging of the tubing in the flow system. A schematic of the flow cell is shown in Fig. 6a. We developed the flow cell structure with carbon-felt electrodes in both chambers and an anion exchange membrane that divides the cell into the cathodic and anodic chambers and enables the pH difference between them to be maintained. The system is equipped with two reservoirs, one for catholyte that contains NRH2, which absorbs CO2 from the CO2-rich gas stream, and one for the anolyte that contains NR from which separated CO2 would be discharged to be measured. The results of carbon capture from 15% CO2 are displayed in Fig. 6b, c. We utilized 90% of the capacity of the system to minimize undesired side reactions under the constant current mode of operation at 50 mA with 15% CO2. The liquid flow rate was 0.349 mL/min, giving 6.3 min of residence time in the 2.2 mL volume of each chamber. The gas output and CO2 fraction were recorded simultaneously during the operation to show the reproducibility of CO2 capture and release over a 12 h period, which corresponds to over eight circulations of the solution through the system. The linearity of the cumulative CO2 released over time depicted in Fig. 6b indicates steady state operation with a constant rate of CO2 capture and release, yielding a separation of ~350 mL of CO2 in 12 h. In Fig. 6c, electron utilization, calculated from the CO2 flow rate and the electric current, showed 0.41 for the first cycle and jumped to 0.71 in the second cycle with better stability. The electron utilization dropped gradually to 0.5 after 12 h. The minimum energy requirement can be estimated from the voltage gap obtained from CV experiments for the cyclic system (0.26 V) combined with the electron utility (0.71) to provide 35 kJe/mol of CO2 (Supplementary equations 8 and 9).

Fig. 6. Continuous flow operation of the NR/NRH2 redox system.

a Scheme of continuous flow electrochemical cell using the NR/NRH2 redox cycle for CO2 capture and release experiments. b Released CO2 amount over time with a feed gas composition of 15% CO2. c Electron utilization over time with a feed gas concentration of 15% CO2. Electrolytes comprised 15 mL of 50 mM NRH2 in 1 M NA and 1 M KCl and 15 mL of 50 mM NRH in 1 M NA and 1 M KCl in water. The red curve indicates the average value of electron utilization for each one-way travel (circulation time/2). The numbers in red indicate the time/circulation time. d Released CO2 amount over time using ambient air as the feed gas. e Electron utilization over time with an ambient air feed. Electrolytes comprised 30 mL of 50 mM NRH2 in 1 M NA and 1 M KCl and 30 mL of 50 mM NR in 1 M NA and 1 M KCl in water. The red curve indicates the average value of electron utilization for each one-way travel (circulation time/2). The numbers in red indicate the time/circulation time. The yellow triangle mark indicates where the air needle was replaced.

To explore the possibility of using the NR/NRH2 flow cell for direct air capture, we performed CO2 capture and release using ambient air as a feed gas (Fig. 6d, e). The scheme of the setup is the same as in Fig. 6a with a constant current mode of operation at 30 mA, a liquid flow rate of 0.218 mL/min (residence time of 10.1 min), and a flow rate of bubbling air of ca. 1000 mL/min. We used in-house supply air without any pretreatment before the experiments. We have included additional water injection at 1.5 mL/h to the catholyte to compensate for water evaporation by the rapid bubbling of the air through the solution. Figure 6d presents the amount of released CO2 over time. The system separated ~880 mL of CO2 from ambient air over 96 h. As depicted in Fig. 6e, the electron utilization was increased from 0.24 to 0.32 within the first circulation time (4.8 h). The electron utilization was maintained between 0.3–0.4 for 96 h of operation. The reduction in electron utilization after ca. 43 h was due to partial clogging of the needle used to introduce air to the catholyte solution; the high air flow rate (ca. 1000 mL/min) quickly dried water at the tip of the needle, leading to precipitation of solution components, most likely NR, NA, and KCl. Indeed, we repeatedly observed a reduction in electron utilization every 24–48 h due to this air needle clogging. On replacement of the air needle, we observed that the electron utilization increased again to the range of 0.3–0.4. The minimum energy requirement for direct air capture can be estimated from the voltage gap obtained from CV experiments for the cyclic system (0.26 V) combined with the best electron utility (0.38) to provide 65 kJe/mol of CO2 (Supplementary equations 8 and 10). After the operation of direct air capture in a continuous flow, the anolyte and catholyte solutions were analyzed by 1H-NMR to confirm no participation of NA in this redox process (See Supplementary Fig. 4).

Although further optimization and engineering efforts are required for scale-up, the NR/NRH2 redox couple meets several essential criteria for implementation in carbon capture processes, including redox stability, reasonable solubility in water, fast kinetics, and oxygen insensitivity. In addition, to operate this system with the minimum potential required on an industrial scale, it will be necessary to increase the current density and reduce the overpotential by optimizing the design of the cell structure and material.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated electrochemical CO2 capture and release from 15% CO2 and ambient air using the NR/NRH2 redox system in an aqueous electrolyte. The estimated minimum electrochemical energy requirements in continuous flow are in the range of 35 kJe/mol of CO2 using 15% CO2 and 65 kJe/mol of CO2 using air. The NRH2 solution exhibits a fast CO2 absorption rate from 1 to 15% CO2, while a higher capacity with 15% CO2 was observed. Notable stability of the NRH2 solution under O2 was demonstrated over 1 week. We demonstrated a robust, stable, reversible, and scalable continuous flow electrochemical cell operation with homogeneous aqueous solutions over 96 h under air. We were able to ascertain that the absorption unit can be improved for system stability in the future. Due to the slow absorption of CO2 from the air (410 ppm), a high flow rate of air was necessary to saturate the catholyte solution. In our lab scale demonstration, we used ca. 1000 mL/min of airflow for the operation at 30 mA current and 20–30 mL of catholyte solution. Due to the rapid bubbling of the solution, splashing of the catholyte and evaporation of water may have caused degradation in the lifetime of the cell. We believe that a better CO2 absorption unit design can improve CO2 absorption rate as well as the electrochemical cell’s operation time in future studies. The use of an aqueous solution of low-cost organic molecules that are stable to oxygen, air, and water implies that a carbon capture system based on this redox cycle has the potential for further development and wider applications.

Methods

Procedure for electrochemical reduction of NR in batch

Reactions were carried out with carbon felt (0.5 cm × 0.3 cm × 2 cm was immersed in the solution) cathode and a stainless-steel wire anode in 5 mL H-cell with #9 O-ring equipped with anion exchange membrane. In the cathodic chamber, NRH (58 mg, 0.2 mmol, 50 mM), nicotinamide (488 mg, 4 mmol, 1 M) and lithium perchlorate (212 mg, 2 mmol, 0.5 M) were added into water (4.0 mL). In the anodic chamber equipped with a needle to prevent pressurization was placed lithium perchlorate solution (212 mg, 2 mmol, 0.5 M, 4.0 mL of water). The solution was bubbled with nitrogen for 10 min, after which the electrochemical potential was applied at room temperature by a constant current of –50 mA for 696 s (0.36 mmol of electrons).

Procedure for electrochemical oxidation of NRH2 solution in batch

Reactions were carried out with carbon felt (0.5 cm × 0.3 cm × 2 cm was immersed in the solution) anode and a stainless-steel wire cathode in 5 mL H-cell with #9 O-ring equipped with anion exchange membrane. In the anodic chamber, the NRH2 solution (50 mM, 4 mL) was bubbled by 15% CO2 for 12 min. In the cathodic chamber equipped with a needle to prevent pressurization was placed lithium perchlorate solution (212 mg, 2 mmol, 0.5 M, 4.0 mL of water). The electrochemical potential was applied at room temperature by a constant current of 50 mA for 696 s (0.36 mmol of electrons). The gas output from the anodic chamber was measured by a flow meter and FT-IR CO2 sensor.

Procedure for CO2 absorption experiments of NRH2 solution

Procedure for electrochemical reduction of NR in batch was followed with an electrochemical potential of constant current of –50 mA for 773 s (0.40 mmol of electrons) to provide 50 mM NRH2 solution. A 1 mL of the solution was transferred to a 10 mL vial that was prefilled with 1, 4, and 15% CO2 (balanced by nitrogen) and bubbled at a flow rate of 3.33 mL/min. An additional experiment with 15% CO2 at a lower flow rate of 1 mL/min was carried out. The gas output from the vial was measured by a flow meter and FT-IR CO2 sensor.

Procedure for CO2 absorption experiments of EDA and MEA solutions

Aqueous solutions of EDA (50 mM in 1 mL of water) and MEA (50 mM in 1 mL of water) were transferred to a 10 mL vial that was prefilled with 1, 4, and 15% CO2 and bubbled at a flow rate of 3.33 mL/min. The gas output from the vial was measured by a flow meter and FT-IR CO2 sensor.

Procedure for CO2 absorption and release experiments using ambient air in batch

The procedure for electrochemical reduction of NR in the batch was followed to provide NRH2 solution (50 mM, 4 mL). The solution was transferred to a 20 mL vial and bubbled with air from the in-house supply at ca. 120 mL/min. After contacting to air, the solution was transferred to the anodic chamber and the procedure for electrochemical oxidation was followed. The gas output from the anodic chamber was measured by a flow meter and FT-IR CO2 sensor.

Procedure for pH measurement during CO2 absorption

Procedure for electrochemical reduction of NR in the batch was followed to provide NRH2 solution (50 mM, 5 mL). The 5 mL of solution was transferred to an 8 mL vial equipped with a pH probe and bubbled with 1, 4, and 15% CO2 (balanced by nitrogen) at a flow rate of 100 mL/min and air at a flow rate of ca. 120 mL/min.

Procedure for stability tests using UV–vis absorption spectroscopy

Procedure for electrochemical reduction of NR in the batch was followed with an electrochemical potential of constant current of at –50 mA for 773 s (0.40 mmol of electrons) to provide 50 mM NRH2 solution. A set of 1 mL of solution in an 8 mL vial was prepared and contacted with oxygen (flow rate of 3 mL/min), nitrogen (flow rate of 3 mL/min), CO2 (flow rate of 3 mL/min), and air (flow rate of 5 mL/min). The samples were measured by UV–vis after 30 min, 2 h, and 1 d. Each time 10 µL of the samples were collected and diluted with 10 mL phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.6) to provide 50 µM solutions. After 1 day, the solutions were sealed under the contracted gas and stored at room temperature for 1 week. The 10 µL samples were collected and diluted with 10 mL phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.6) to provide 50 µM solutions that were measured by UV–vis absorption spectroscopy.

Procedure for electrochemical capture and release of CO2 in a continuous flow using 15% CO2

Reactions were carried out with carbon felt (1.5 cm × 0.3 cm × 1.5 cm was immersed in the solution) cathode and a stainless-steel wire anode in 20 mL H-cell with #20 O-ring equipped with anion exchange membrane. In the cathodic chamber, NRH (289 mg, 1 mmol, 50 mM), nicotinamide (2.4 g, 20 mmol, 1 M), and potassium chloride (1.5 g, 20 mmol, 1 M) were added into water (20 mL). In the anodic chamber equipped with a needle to prevent pressurization was placed potassium chloride solution (1.5 g, 20 mmol, 1 M, 20 mL water). The electrochemical potential was applied at room temperature by a constant current of –100 mA for 1739 s (1.8 mmol of electrons) to provide 20 mL of 45 mM NRH2 solution.

The 15 mL NR solution (50 mM, 1 M NA, 1 M KCl) was added to a 50 mL round bottom flask anolyte reservoir. The 15 mL NRH2 solution was transferred to a 100 mL round bottom flask catholyte reservoir equipped with a stir bar. The solution was bubbled by 15% CO2 (balanced by nitrogen) at a flow rate of 70 mL/min for 15 min.

The peristaltic pump equipped with Masterflex® 14 tubing was set to 1.6 rpm for the liquid flow rate of 0.349 mL/min providing 6.3 min of residence time in each 2.2 mL chamber of the flow cell. After one residence time passed from pumping the solution, the electrochemical potential at a constant current mode of 50 mA was applied to the cell. During operation, a flow rate of 15% CO2 gas stream was maintained at 20 mL/min. The output gas flow from the anolyte reservoir was measured by a flow meter and CO2 sensor.

Procedure for electrochemical capture and release of CO2 in continuous flow using air

The 30 mL NR solution (50 mM, 1 M NA, 1 M KCl) was added to a 50 mL round bottom flask anolyte reservoir. The 30 mL of NRH2 solution was transferred to a 500 mL three-neck round bottom flask catholyte reservoir equipped with a stir bar. The solution was bubbled by ambient air at a flow rate of ca. 1000 mL/min for 12 h to saturate the solution. The solution pH was monitored by in situ pH probe simultaneously. The pH was maintained between 9 and 10 during the experiment.

The peristaltic pump equipped with Masterflex® 14 tubing was set to 1.0 rpm for the liquid flow rate of 0.218 mL/min providing 10.1 min of residence time in each 2.2 mL chamber of the flow cell. After one residence time passed from pumping the solution, the electrochemical potential at a constant current mode of 30 mA was applied to the cell. During operation, a flow rate of air was maintained at ca. 1000 mL/min. The output gas flow from the anolyte reservoir was measured by a flow meter and CO2 sensor. A syringe pump was used to add water into the catholyte reservoir at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/hour.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Bing Yan for the discussion on the electron transfer mechanism. This work was partially supported jointly by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Divisions of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences (CSGB), and Materials Sciences and Engineering (MSE) under FWP 76830.

Author contributions

H.S. conceived the idea, designed the research, and performed the experiments. H.S. and T.A.H. wrote the manuscript, commented on the final draft of the manuscript, and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gabriele Laudadio and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its Supplementary information files, and also are available from the corresponding authors.

Competing interests

H.S. and T.A.H. are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (No.: 63/355,701; filed on 27 June 2022).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-35866-w.

References

- 1.IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021).

- 2.Hashimoto, K. Global temperature and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration. In: Global Carbon Dioxide Recycling 5–17 (Springer Singapore, 2019). 10.1007/978-981-13-8584-1_3.

- 3.Bui M, et al. Carbon capture and storage (CCS): the way forward. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11:1062–1176. doi: 10.1039/C7EE02342A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanz-Pérez ES, Murdock CR, Didas SA, Jones CW. Direct capture of CO2 from ambient air. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:11840–11876. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.House KZ, et al. Economic and energetic analysis of capturing CO2 from ambient air. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 2011;108:20428–20433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012253108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fasihi M, Efimova O, Breyer C. Techno-economic assessment of CO2 direct air capture plants. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;224:957–980. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renfrew SE, Starr DE, Strasser P. Electrochemical approaches toward CO2 capture and concentration. ACS Catal. 2020;10:13058–13074. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c03639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharifian R, Wagterveld RM, Digdaya IA, Xiang C, Vermaas DA. Electrochemical carbon dioxide capture to close the carbon cycle. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021;14:781–814. doi: 10.1039/D0EE03382K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin S, Wu M, Gordon RG, Aziz MJ, Kwabi DG. pH swing cycle for CO2 capture electrochemically driven through proton-coupled electron transfer. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020;13:3706–3722. doi: 10.1039/D0EE01834A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie H, et al. Low-energy-consumption electrochemical CO2 capture driven by biomimetic phenazine derivatives redox medium. Appl. Energy. 2020;259:114119. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.114119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahimi M, Catalini G, Puccini M, Hatton TA. Bench-scale demonstration of CO2 capture with an electrochemically driven proton concentration process. RSC Adv. 2020;10:16832–16843. doi: 10.1039/D0RA02450C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voskian S, Hatton TA. Faradaic electro-swing reactive adsorption for CO2 capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019;12:3530–3547. doi: 10.1039/C9EE02412C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Ye H-Z, Diederichsen KM, Van Voorhis T, Hatton TA. Electrochemically mediated carbon dioxide separation with quinone chemistry in salt-concentrated aqueous media. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2278. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16150-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Apaydin DH, Głowacki ED, Portenkirchner E, Sariciftci NS. Direct electrochemical capture and release of carbon dioxide using an industrial organic pigment: quinacridone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:6819–6822. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scovazzo P, Poshusta J, DuBois D, Koval C, Noble R. Electrochemical separation and concentration of <1% carbon dioxide from nitrogen. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003;150:D91. doi: 10.1149/1.1566962. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizen MB, Wrighton MS. Reductive addition of CO2 to 9,10‐phenanthrenequinone. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989;136:941–946. doi: 10.1149/1.2096891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranjan R, et al. Reversible electrochemical trapping of carbon dioxide using 4,4′-bipyridine that does not require thermal activation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:4943–4946. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh P, et al. Electrochemical capture and release of carbon dioxide using a disulfide–thiocarbonate redox cycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1033–1036. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seo H, Rahimi M, Hatton TA. Electrochemical carbon dioxide capture and release with a redox-active amine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:2164–2170. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c10656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stern MC, Simeon F, Herzog H, Hatton TA. Post-combustion carbon dioxide capture using electrochemically mediated amine regeneration. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013;6:2505. doi: 10.1039/c3ee41165f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahimi M, et al. An electrochemically mediated amine regeneration process with a mixed absorbent for postcombustion CO2 capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:8999–9007. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmatifar, A., Kang, J. S., Ozbek, N., Tan, K. & Hatton, T. A. Electrochemically mediated direct CO2 capture by a stackable bipolar cell. ChemSusChem10.1002/cssc.202102533 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Singh V, Kim S, Kang J, Byon HR. Aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Nano Res. 2019;12:1988–2001. doi: 10.1007/s12274-019-2355-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin S, Wu M, Jing Y, Gordon RG, Aziz MJ. Low energy carbon capture via electrochemically induced pH swing with electrochemical rebalancing. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:2140. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29791-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coffman RE, Kildsig DO. Effect of nicotinamide and urea on the solubility of riboflavin in various solvents. J. Pharm. Sci. 1996;85:951–954. doi: 10.1021/js960012b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walz FG, Terenna B, Rolince D. Equilibrium studies on neutral red-DNA binding. Biopolymers. 1975;14:825–837. doi: 10.1002/bip.1975.360140411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halliday C, Matthews D. c. Some electrochemical and photoelectrochemical properties of 3-Amino-7-dimethylamino-2-methylphenazine (Neutral Red) in aqueous solution. Aust. J. Chem. 1983;36:507. doi: 10.1071/CH9830507c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barzagli F, Mani F, Peruzzini M. A comparative study of the CO2 absorption in some solvent-free alkanolamines and in aqueous monoethanolamine (MEA) Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:7239–7246. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan Y, Rochelle GT. CO2 absorption rate in semi-aqueous monoethanolamine. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018;182:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2018.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study, including experimental procedures and compound characterization, are available within the article and its Supplementary information files, and also are available from the corresponding authors.