Abstract

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction (ACLR) is often associated with pain, functional loss, poor quality of life and accelerated knee osteoarthritis development. The effectiveness of interventions to enhance outcomes for those at high risk of early-onset osteoarthritis is unknown. This study will investigate if SUpervised exercise-therapy and Patient Education Rehabilitation (SUPER) is superior to a minimal intervention control for improving pain, function and quality of life in young adults with ongoing symptoms following ACLR.

Methods and analysis

The SUPER-Knee Study is a parallel-group, assessor-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Following baseline assessment, 184 participants aged 18–40 years and 9–36 months post-ACLR with ongoing symptoms will be randomly allocated to one of two treatment groups (1:1 ratio). Ongoing symptoms will be defined as a mean score of <80/100 from four Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) subscales covering pain, symptoms, function in sports and recreational activities and knee-related quality of life. Participants randomised to SUPER will receive a 4-month individualised, physiotherapist-supervised strengthening and neuromuscular programme with education. Participants randomised to minimal intervention (ie, control group) will receive a printed best-practice guide for completing neuromuscular and strengthening exercises following ACLR. The primary outcome will be change in the KOOS4 from baseline to 4 months with a secondary endpoint at 12 months. Secondary outcomes include change in individual KOOS subscale scores, patient-perceived improvement, health-related quality of life, kinesiophobia, physical activity, thigh muscle strength, knee function and knee cartilage morphology (ie, lesions, thickness) and composition (T2 mapping) on MRI. Blinded intention-to-treat analyses will be performed. Findings will also inform cost-effectiveness analyses.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is approved by the La Trobe University and Alfred Hospital Ethics Committees. Results will be presented in peer-reviewed journals and at international conferences.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12620001164987.

Keywords: knee, rehabilitation medicine, sports medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The exercise-therapy programme was developed and piloted with patients and clinicians, aligns with American College of Sports Medicine recommendations and is described based on the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template.

Sufficiently powered trial evaluating change from baseline to 4 months (primary endpoint) and 12 months facilitating longer-term effectiveness evaluation of exercise-therapy and education.

This trial will evaluate both the illness (ie, symptoms) and disease (ie, structure) of osteoarthritis and include cost-effectiveness analysis.

While outcome assessors are blinded to group allocation and physiotherapists delivering the intervention are blinded to the control intervention, participant blinding was not possible due to the type of interventions.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is one of the most common serious knee injuries in young, healthy people participating in sports involving jumping, pivoting and cutting activities.1 Treatment success is often judged on a timely return to sport.2 Yet, 55% do not return to competitive sport,3 and half will develop post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis (OA), unacceptable persistent pain, functional loss and poor quality of life before the age of 40 years.4–7 Occupational and carer responsibilities in many of these young adults also create formidable societal and economic burden.

OA can be characterised by symptoms such as pain and functional limitations and/or structural joint changes seen on imaging. Both symptoms and structural changes are common within the first decade after ACL reconstruction (ACLR), yet they are often discordant.5 8 International government-endorsed OA initiatives recommend evaluating symptoms and structure in OA clinical trials to address the heterogeneity of the disease.9

Identifying interventions that can improve knee-related symptoms and prevent or slow structural changes in young adults following ACLR is an international priority.10 11 Exercise-therapy improves pain and function in older populations with primary (non-traumatic) knee OA,12 but effective treatments to improve structure (ie, disease-modifying interventions) have thus far proven elusive.13 Secondary prevention strategies for those with early manifestations (or at high risk) of OA, such as following ACLR, offer potential to alter the OA trajectory.14 15 Targeted exercise-therapy might slow structural worsening,16 with preliminary studies reporting improved knee cartilage composition in people at risk of OA (post-meniscectomy)17 and with non-traumatic early OA over 4 and 12 months, respectively.18 19

People who report inadequate recovery (ongoing symptoms and impaired function) 1 year after ACLR are likely to have worsening symptoms and rapidly deteriorating joint structure in the future.20–22 These young adults with inadequate recovery urgently need treatment options to alter their OA trajectory. Our feasibility study indicated that a full-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluating a physiotherapist-led, exercise-therapy and education programme for young adults with ongoing symptoms approximately 1 year after ACLR (ie, when no further improvement is likely without treatment) is feasible and likely associated with a clinically worthwhile effect for pain, function and quality of life.23

The primary aim of this RCT is to estimate the average effect of SUpervised exercise-therapy and Patient Education Rehabilitation (SUPER) compared with a minimal intervention control on knee-related pain, function and quality of life in young adults with ongoing symptoms at high risk of early-onset knee OA 9–36 months after ACLR. We hypothesise that the SUPER intervention will result in greater improvements in knee-related pain, symptoms, function and quality of life after 4 months (primary endpoint) and 12 months (secondary endpoint) compared with a minimal intervention control. Secondary aims are to assess 4-month and 12-month effectiveness of SUPER on: (1) self-reported global rating of change (GROC) and achievement of acceptable symptoms; (2) health-related quality of life; (3) physical activity; (4) kinesiophobia; (5) thigh muscle strength and function; and (6) change in knee cartilage health. Intervention and healthcare resource use will also be recorded to inform economic evaluation.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This study protocol describes a pragmatic, parallel-group assessor-blinded RCT conforming to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials statement.24 Reporting of the completed RCT will conform to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement for reporting RCTs25 in conjunction with the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR),26 and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) guidelines.27 The trial will be conducted at a single university site (La Trobe University) in Melbourne, Australia with enrolment planned to occur over 3 years (2021–2023) and 12-month follow-up completed in 2024. The primary endpoint will be at 4 months (immediately following the intensive supervised exercise-therapy phase), with additional follow-up at a minimum of 12 months (further longer-term follow-up dependent on funding). The study was prospectively registered on the Australian & New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ACTRN12620001164987).

Participants

One hundred and eighty-four young adults fulfilling the eligibility criteria (table 1) will be included.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Aged 18–40 years at the time of ACLR | Synthetic ACLR graft |

| 9–36 months following ACLR | Concomitant intra-articular knee fracture |

| Symptomatic ACLR knee: mean score of <80/100 from four Knee injury and OA Outcome Score subscales covering pain, symptoms, function in sports/recreation and quality of life | Planning to relocate interstate/internationally in following 12 months or unable to commit to study assessments |

| Willing and able to participate in exercise-therapy 2–3 times per week for at least 4 months | Any of the following in the past 3 months: knee re-injury, surgery or injection (either knee) |

| Undertaken rehabilitation in past 6 weeks (for conditions affecting either knee) | |

| Contraindications to MRI | |

| Planning knee surgery in following 12 months (eg, graft rupture, cyclops lesion (localised anterior arthrofibrosis) on MRI) | |

| Other reasons for exclusion (health condition affecting physical function, mentally unable to participate, pregnancy, unable to understand English, etc) |

ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; OA, osteoarthritis.

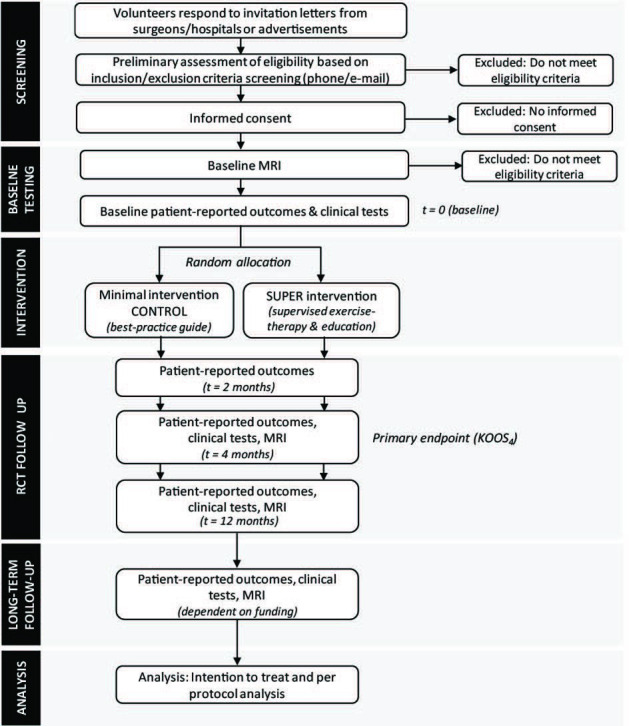

Recruitment procedure

Trial flow is outlined in figure 1. Participants will be recruited from approximately 15 collaborating private orthopaedic surgeons and 8 public hospital sites in Victoria, Australia. Consistent with our pilot work,28 29 potentially eligible participants (ie, individuals with an ACLR from our network of collaborating private orthopaedic surgeons or public hospitals) will be mailed study information inviting them to contact a member of the research team. Additional participants will be recruited from the general community via advertisements in local newspapers, community magazines and newsletters (eg, university staff bulletins, sports club newsletters), posters in the community and social media.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study. KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SUPER, SUpervised exercise-therapy and Patient Education Rehabilitation.

Volunteers responding to the invitation letter or advertisements will be screened for eligibility using a three-stage process. First, screening questions will be asked via telephone or email. Second, potentially suitable volunteers will be sent the Knee injury and OA Outcome Score (KOOS) questionnaire electronically (or hard copy if preferred) to confirm symptomatic eligibility. Third, baseline MRI scans will be assessed to confirm the absence of any pathology potentially necessitating surgery (eg, graft rupture, symptomatic cyclops lesion). If both knees are eligible, the most symptomatic knee will be considered as the index knee for the trial.

Randomisation procedure, concealment of allocation and blinding

Eligible, willing and consenting volunteers will be randomised to the SUPER or control group after baseline assessment, commencing as soon as possible. A computer-generated randomisation schedule has been developed a priori by an independent statistician in random permuted blocks of 4–8 to maintain a periodical allocation ratio of 1:1. To ensure concealed allocation, the randomisation schedule will be stored electronically in the secure Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system and only accessible to an unblinded researcher once baseline measures have been obtained. Investigators conducting study assessments will be blinded to group allocation. As the primary outcome is self-reported, participants are considered assessors; therefore, participants (and thus assessors) will be blinded to previous scores. Physiotherapists and participants cannot be blinded to group allocation owing to the type of interventions. An independent statistician, blinded to group allocation, will perform the primary RCT analysis. To reduce risk of interpretation bias, blinded results from the analyses (group A compared with group B) will be presented to all authors, who will agree on two alternative written interpretations before the data manager unblinds the randomisation code.30

Interventions

Supervised exercise-therapy and Patient Education Rehabilitation

Participants allocated to SUPER will participate in a supervised exercise programme, developed based on best available evidence for patients with ACLR and other knee injuries including OA,31–33 and with input from patients and experienced physiotherapists. An overview of the SUPER programme aligning to the CERT guidelines is contained in online supplemental file 1 and summarised as per TIDieR guidelines in table 2. The SUPER intervention aims to increase lower-limb muscle strength, endurance and power, functional performance and neuromuscular control, increase understanding of knee health, facilitate return to desired sports activity and enhance physical activity. Registered physiotherapists with ≥3 years of experience treating patients following ACLR will deliver SUPER in community settings following a 4-hour training workshop supplemented with 3 hours of online webinars. To minimise participant travel burden, study physiotherapists will be located at 12–14 private physiotherapy clinics across greater Melbourne and regional Victoria.

Table 2.

Overview of intervention delivery described according to the TIDieR guidelines

| Brief name | SUPER intervention | Minimal intervention control |

| Why | Exercise-therapy to enhance muscle strength, function and physical activity can improve pain and quality of life in older adults with OA12 and address risk factors for post-traumatic OA.72 | The booklet was produced based on information provided to patients and thus, accurately reflects usual care. |

| What materials | Participants receive an intervention handbook detailing all study details, exercises and logbook, and access to videos of all exercises. | Participants receive a ‘best-practice guide’ booklet of possible exercises with no specific exercise prescription frequency. |

| What procedures | Five priority exercises targeting: (1) weight-bearing knee extension; (2) open-chain knee extension; (3) plyometrics; (4) balance/agility; (5) knee flexion and four optional exercises targeting: (a) trunk; (b) hip abductors; (c) hip adductors; (d) calf–each with 3–6 levels of difficulty. Physiotherapists prescribe strength exercises (3×8–12 reps) with perceived exertion criteria (aim ≥7/10) and progressed as per ACSM and periodisation guidelines (1-week/month easier ~5/10 exertion). Dedicated education sessions at week 1 and week 4, supported by slides and booklets. | Booklet explained at randomisation. Exercise options provided (similar to SUPER intervention), but not prescribed. Participants expected to exercise unsupervised. Participants may contact the physiotherapist by phone once only to ask questions/get clarification. |

| Who provided | Registered physiotherapists with ≥3 years of relevant experience, trained to deliver all components (exercise and education). | One appointment with a registered physiotherapist with ≥3 years of clinical experience, not involved in delivering SUPER intervention, to explain booklet elements. |

| How | Delivered supervised in groups and individually (supported by unsupervised sessions) in phase 1, progressing to completely unsupervised in phase 2. | Delivered unsupervised. |

| Where | Supervised sessions at private physiotherapy clinics and unsupervised sessions at gym/home. | Booklet explained at La Trobe University, Melbourne. Gym and home exercise options provided. |

| When and how much | Phase 1 (0–4 months): Frequency and duration Supervised sessions (30–60 min) 2 times/week Unsupervised sessions (30–60 min) 1–2 times/week Number of sessions: 32 supervised+16 unsupervised Phase 2 (5–12 months): Frequency and duration Progress to unsupervised sessions 2–3 times weekly (dependent on meeting predefined criteria*). Two supervised (booster) sessions at 8 and 11 months post-baseline. Number of sessions: 2 supervised+108 unsupervised |

Unsupervised exercise-therapy (self-prescribed frequency) after one face-to-face appointment. |

| Tailoring | Tailored selection and progression of lower-limb muscle strength, power and neuromuscular control exercises and education based on participant preferences, goals and clinical presentation. | Standardised exercise examples and education. |

| Modifications | Modifications will be reported. If state and/or institution COVID-19 pandemic restrictions prevent face-to-face follow-up assessments, participants will be encouraged to continue assigned treatment until face-to-face assessments can be conducted. If restrictions prevent supervised rehabilitation, telerehabilitation options will be offered wherever possible. | |

| How well (planned) | Treating physiotherapists receive prior training in how to deliver and supervise the programme. Fidelity assessed by auditing. Participant adherence to supervised and unsupervised sessions assessed through logbooks, clinic attendance sheets and online (fortnightly/monthly) questionnaire. | |

| How well (actual) | This will be reported in the primary paper. | |

*Predefined criteria for ceasing supervised sessions in phase 2=participant’s goals are met, participant satisfied with current symptoms/function and global rating of change reported as at least ’better’.

ACSM, American College of Sports Medicine; OA, osteoarthritis; SUPER, SUpervised exercise-therapy and Patient Education Rehabilitation; TIDieR, Template for Intervention Description and Replication.

bmjopen-2022-068279supp001.pdf (99.1KB, pdf)

SUPER is divided into two phases:

Phase 1 (0–4 months). Participants will be provided with details of the SUPER intervention verbally and via an intervention handbook detailing all exercises and an exercise logbook, and provided access to videos of all exercises. Participants will complete their exercise programme supervised by a physiotherapist twice per week in phase 1, with at least one additional unsupervised session at a gym or home encouraged (table 2). Participants/physiotherapists will also have the option of a second opinion by a member of our clinical expert physiotherapy team if SUPER is failing to facilitate improvement (either at 2 or 4 months post-baseline). Second opinion will provide assessment and guidance on exercise-therapy and patient education needs.

Phase 2 (5–12 months). The intervention provided in phase 2 will depend on whether the following predefined criteria are met at the 4-month follow-up assessment: participant’s goals are met (ie, goals set with treating physiotherapist at start of phase 1), participant satisfied with current symptoms/function (ie, responded ‘yes’ to patient-acceptable symptom state question (see the Outcomes section for details)) and GROC reported as at least ‘better’.

For participants meeting all criteria, phase 2 will involve ongoing independent exercise-therapy sessions (approximately 30–60 min duration, two to three times per week at a gym or home). Participants may request a physiotherapy booster session if they become unsure about continuing self-management or exercise-therapy or predefined criteria are no longer met. Booster sessions can continue once per week and will focus on the priority exercises and discussion of self-management strategies.

Participants not meeting all criteria at the end of phase 1 will be offered ongoing once per week supervised exercise-therapy in phase 2. Once all criteria are met, participants will continue unsupervised exercise-therapy sessions at a gym or home with physiotherapy booster sessions as required (as per above criteria). All participants will be offered a membership to a local gym to encourage unsupervised exercise-therapy during phase 2. An additional booster session with the treating physiotherapists will occur at 8 and 11 months post-baseline.

Exercise-therapy will be tailored to each participant to match their individual preferences, goals and clinical presentation (eg, muscle strength, pain severity, and personal, sporting, work and functional needs). The exercise-therapy programme consists of five ‘priority’ exercises and four optional exercises (table 2 and online supplemental file 2). The total number of exercises prescribed (maximum number of nine) will depend on the participant’s available time and willingness, and physiotherapist clinical reasoning—but will always include the five ‘priority’ exercises.

bmjopen-2022-068279supp002.pdf (33.7MB, pdf)

Each exercise has three to six levels of difficulty. Physiotherapists will supervise and progress exercises based on defined criteria guided by American College of Sports Medicine strength training principles34 and perceived difficulty using rating of perceived exertion and minimal pain (eg, <3/10 on Numerical Pain Scale) (details in online supplemental file 1).

Patient education was co-designed with experienced physiotherapists and pilot study participants23 and aims to support the exercise-therapy programme and build motivation and capability to sustain the exercises during and after the initial 4-month supervised phase (table 2). Individualised health education regarding expectations and goals, exercise principles, improving adherence, pain/fear management, long-term outcomes, weight control, and appropriate physical, occupational and sporting activity promotion will be delivered during the physiotherapy treatment sessions. Two dedicated education sessions of 45–60 min duration will be delivered during phase 1 (week 1 and week 4). Participants will be counselled regarding physical activity levels with a targeted training programme adhering to Australian Physical Activity Guidelines and given an activity monitor (Garmin vívofit 4 activity tracker) if they do not have access to one to support measurement and attainment of physical activity goals.

Minimal intervention control

Reflecting current standard care, the minimal intervention control group will receive a ‘best-practice guide’ booklet and one face-to-face appointment with a registered physiotherapist with ≥3 years of clinical experience (not involved in treating participants in the SUPER intervention) to explain booklet elements and answer questions about its contents. The booklet outlines similar exercises and patient education as in the SUPER intervention (online supplemental file 3). However, exercise is expected to be performed unsupervised (table 2). Participants may also contact the treating physiotherapist by phone on one occasion to ask questions or get further clarification but will not be provided with information extending the scope of the booklet. The booklet was produced based on the information provided by 10 high-volume orthopaedic surgeons in Melbourne to their patients post-ACLR. Participants will be encouraged at the 4-month assessment to continue following the booklet up until the 12-month assessment.

bmjopen-2022-068279supp003.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Irrespective of group allocation, participants will be asked to refrain from other musculoskeletal therapies (eg, chiropractic care, osteopathy, myotherapy, intra-articular injections) for their knee pain during the trial. Participants will be allowed to continue care for other unrelated pre-existing conditions.

Data collection procedure

Data will be collected at baseline and 2, 4 and 12 months after randomisation, with 4 months the a priori primary endpoint as this coincides with the completion of the supervised exercise-therapy intervention in phase 1. Where possible, data will be collected and managed using a secure web-based software platform (REDCap) hosted at La Trobe University,35 which has equivalent measurement properties to paper-based completion.36 This strategy was used in our pilot study following ACLR, with demonstrated feasibility.23 Paper versions will also be available if preferred by participants.

Outcomes

Baseline characteristics

Participant characteristics including height, body mass, waist girth, leg length, knee injury and rehabilitation details, socioeconomic details (eg, education level, employment status), family history of OA, sporting history and health literacy (Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine37) will be collected. Surgical details will be recorded from surgical files including date, graft type and concomitant injuries/procedures. We will also record knee-related objective measures (table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of data collection

| Baseline | 2 months | 4 months | 12 months | |

| Participant characteristics | ||||

| Age | X | |||

| Sex | X | |||

| Height, body mass, waist girth | X | X | X | |

| Country of birth | X | |||

| Education level | X | |||

| Living situation | X | |||

| Smoking history | X | |||

| Health literacy (REALM) | X | |||

| Employment status | X | X | X | |

| Prior knee injury/treatment | X | |||

| ACL injury, surgery and rehabilitation details | X | |||

| Sport/activity participation | X | X | X | |

| Family history of osteoarthritis | X | |||

| Medication use | X | |||

| Comorbidities | X | |||

| Flexion/extension range of motion | X | X | X | |

| Joint line tenderness (medial and lateral) | X | X | X | |

| Crepitus | X | X | X | |

| Effusion (sweep test) | X | X | X | |

| Stability (Lachman’s, pivot shift) | X | |||

| Patient-reported outcomes | ||||

| Knee injury Osteoarthritis Outcome Score | X | X | X | X |

| EQ-5D-5L | X | X | X | X |

| Tegner Activity Scale | X | X | X | X |

| Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia | X | X | X | |

| Global rating of change | X | X | X | |

| Patient-acceptable symptom state | X | X | X | X |

| Health and Labour Questionnaire | X | X | X | |

| Work Limitations Questionnaire | X | X | X | |

| ACL-Quality of Life Questionnaire | X | X | X | |

| Knee pain (current and worst in last week) | X | X | X | X |

| Physical performance tests | ||||

| Hop performance (four tests) | X | X | X | |

| One-leg rise | X | X | X | |

| Isometric thigh muscle strength | X | X | X | |

| Lower-limb loading | X | X | X | |

| MRI outcomes | X | X | X | |

| Average daily steps | X | X | X |

All participants will receive either a fortnightly (during phase 1) or monthly (during phase 2) online questionnaire via the secure online platform (REDCap) (or hard copy mailed, or phone call depending on participant preference) to assess sports activity, adherence to exercise therapy and any adverse events/other treatment.

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; REALM, Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is the change in KOOS4 score from baseline to 4-month follow-up. KOOS4 is the mean score for the self-reported KOOS subscales pain, symptoms, function in sports and recreational activities and quality of life, which has been used in RCTs following ACL injury.38 The KOOS4 and all KOOS subscale scores range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). The KOOS is a valid and reliable knee-specific questionnaire for assessing patient-reported outcomes in various knee injury populations (eg, from knee injury to OA) and is widely used globally.39 40

Secondary outcomes

KOOS subscales

To allow for clinical in-depth interpretation, scores for the five KOOS subscales will be reported individually (ie, pain, symptoms, function in sports and recreational activities, activities of daily living and quality of life).39

Physical performance

Peak isometric knee extensor and flexor muscle strength and rate of force development will be assessed in sitting using reliable and valid methods at 60° of knee flexion on isokinetic equipment (Biodex Medical Systems, New York, USA).41 A battery of lower-limb functional tasks commonly used following ACLR will assess functional performance: (1) single hop for distance; (2) triple cross-over hop for distance; (3) side-hop; (4) vertical hop and (5) one-leg rise.5 42 43 Such a battery produces high reliability and sensitivity in populations following ACLR.44 Details of physical performance tests are found in online supplemental file 4.

bmjopen-2022-068279supp004.pdf (878.3KB, pdf)

Perceived global change score and patient-acceptable symptom state

GROC will be assessed for pain and function with the questions: ‘Overall, how has your knee pain changed since the start of the study?’ and ‘Overall, how has your knee function changed since the start of the study?’, and answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from ‘much worse’ to ‘much better’ and dichotomised to ‘improved’ (‘much better’, ‘better’) versus ‘not improved’ (‘a little better’ to ‘much worse’). Satisfaction with current knee function (ie, patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS)) will be assessed with the question: ‘Considering your knee function, do you feel that your current state is satisfactory? With knee function, you should take into account all activities during your daily life, sport and recreational activities, your level of pain and other symptoms, and also your knee-related quality of life.’ This will be answered by ‘yes’ or ‘no’.45 Participants not satisfied with current knee function at follow-up assessments (ie, answering ‘no’ to the PASS question) will be asked a second question relating to treatment failure: ‘Would you consider your current state as being so unsatisfactory that you think the treatment has failed?’ This will also be answered by ‘yes’ or ‘no’.45

Knee joint structure

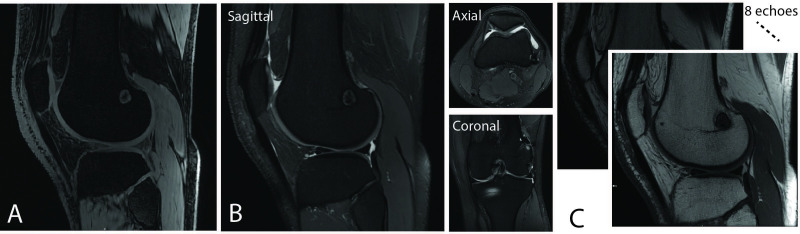

Unilateral knee MRIs will be obtained in supine with the lower-limb in neutral alignment using a 3T scanner (Signa Pioneer, General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) and 18-channel knee coil. Sequences acquired will include proton density-weighted fat-suppressed fast spin-echo sequences in the sagittal, coronal and axial planes, a T2 mapping multi-echo spin-echo sagittal sequence and a sagittal fast spoiled gradient echo sequence (figure 2 and online supplemental file 5). Changes in cartilage collagen content and orientation in extracellular matrices reflecting degeneration will be defined by quantitative changes in T2 relaxation times46 from baseline to 4-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. Knee cartilage thickness changes over 4 and 12 months will also be assessed.47 Post-processing software incorporating semiautomated registration and manual segmentation in 3D will be used for both T2 relaxation time and cartilage thickness. Knee OA features (eg, cartilage defects, meniscal tears, bone marrow lesions, osteophytes) will be scored with established scoring systems48 49 at baseline and 12-month follow-up by a trained reader blinded to clinical outcomes. Individual OA feature worsening will be defined as increase in the size or depth of lesions as previously established.50 Bone shape at the knee will also be assessed using edge-detection semiautomated segmentation with 3D triangulated meshes of bone rigidly registered on a reference template to extract the most important modes of variation of bone shape.51

Figure 2.

MRI protocol. (A) Sagittal fast spoiled gradient echo sequence; (B) sagittal, coronal and axial proton density-weighted fat-suppressed spin-echo sequence; and (C) sagittal multi-echo spin-echo sequence.

bmjopen-2022-068279supp005.pdf (60.9KB, pdf)

Other outcomes

Fear of movement

Knee-related fear of movement will be assessed with the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia.52 This scale has established reliability and validity in musculoskeletal pain populations.53 54

Physical activity

The Tegner Activity Scale will assess self-reported activity level. It is a valid and reliable numerical scale from 0 (sick leave because of knee problems) to 10 (competitive knee-demanding sports at an elite level), with each value indicating the ability to perform certain activities.55 Objective physical activity will be captured using a Garmin vívofit 4 activity tracker (Garmin International, Kansas, USA) or participant’s own device, if appropriate.

Quality of life

We will assess knee-related quality of life, with the ACL-Quality of Life Questionnaire,56 and health-related quality of life with the EQ-5D-5L.57 These measures are reliable and valid for knee pain populations.58 59

Lower-limb loading

Lower-limb loading will be assessed using ground reaction force data during unilateral and bilateral weight-bearing tasks (squat, hop and drop-jump) using force plates and ForceDecks software (Vald Performance, UK).

Knee pain

Current and worst knee pain (and how much participants are bothered by pain) in the previous week will be assessed on a 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (0=no pain/bother, 100=worst pain/bother imaginable).

Treatment-related outcomes

Adherence, exercise level/intensity and other treatments received during the trial

Adherence with the supervised exercise-therapy sessions (ie, number of sessions attended out of 32 possible phase 1 sessions) and intensity/progression of the exercises will be recorded by treating physiotherapists and participants. Inadequate adherence is defined as participating in <22 (70%) supervised sessions. Participants in both groups will record adherence to home exercises and any co-interventions received in a logbook and via fortnightly (phase 1) and monthly (phase 2) online questionnaires.

Adverse events

Any adverse events will be recorded fortnightly during phase 1 and monthly during phase 2 via questionnaires. Furthermore, open probe questioning will enquire about possible adverse events at each of the follow-ups. Healthcare use data obtained as part of cost-effectiveness analysis at final follow-up will also be checked for potential adverse events. An adverse event is defined as any undesirable experience causing participants to seek medical treatment. A serious adverse event is defined as any undesirable event/illness/injury classified as having the potential to significantly compromise clinical outcome or results in significant disability or incapacity, and those requiring inpatient hospital care. Adverse events will be categorised into index knee or other sites and will be assessed for severity by the trial management committee.

Data management

Most outcome data will be collected and managed via REDCap web-based software (hosted at La Trobe University), facilitating simultaneous data entry. For paper-based data collection, data will be entered by a single investigator with a second investigator conducting random checks of a subset of manually entered documents to ensure accuracy. For data analysis, personal data, including participant names, contact details, date of birth and MRI scans, will be stored on the La Trobe University server Research Drive Storage, separately from deidentified (numbered) data. All subsequent study data will be identified by participant number only.

Due to the minimal known risks associated with the interventions being evaluated, this study will not have a formal data monitoring committee and does not require an interim analysis. Any unexpected serious adverse events or outcomes will be discussed by the trial management committee (identical to the authors of this protocol).

Sample size calculation

This trial has been powered to detect a clinically significant between-group difference for the primary outcome of KOOS4. The overall effect size for exercise therapy on self-reported pain and disability is moderate (0.50).12 With this effect size, to achieve 85% power at a two-sided 0.05 significance level on the KOOS4, 146 participants are required. To account for a 20% drop-out, we will recruit 184 participants. This sample size will be sufficient to detect a minimal important change (MIC) in KOOS4 of 9 points in patients following ACLR (with SD of 15).38 60

Stopping rule

If the intended sample size is not reached at 36 months after recruitment commencement, the inclusion of participants will stop at 160, which will ensure a power of 80% for the primary outcome of KOOS4, anticipating up to 20% loss to follow-up. Including a minimum of 160 participants will also provide ≥90% power to detect a statistically significant difference (α=0.05) on the secondary outcome of cartilage quality on MRI (change in cartilage T2 relaxation time) between the SUPER intervention and minimal intervention control groups (anticipated effect size of 0.59).19

Statistical analyses

Analysis will be performed according to the intention-to-treat principle with the statistical analyst blinded to group allocation. Descriptive statistics and generalised linear mixed models (adjusted for baseline measure and referral source (private vs public) as fixed effects) will be used to examine the effect of group allocation on the primary and secondary outcomes. For binomial secondary outcomes (eg, cartilage defect worsening, proportion of participants ‘improved’ on the GROC scale, proportion of participants who had a KOOS4 change exceeding the MIC of 9 points), binomial (logistic) family will be selected. As this is a randomised trial, we do not plan to adjust for other potential confounders (eg, age, sex), but if notable imbalance between groups in potential confounders is observed, we will examine the effect of adjusting for potential confounders (fixed effects).61 While the primary analysis approach is intention-to-treat, per-protocol analysis will also be conducted excluding those who have inadequate adherence with the SUPER intervention to assist with clinical interpretation of findings. Planned exploratory subgroup analyses including repeating analysis by injury characteristics (eg, isolated vs combined ACL injury) will be conducted given the known risk of a combined injury (eg, concomitant meniscal/cartilage) on OA outcomes.62 Two sensitivity analyses are planned. The first will use multiple imputation for missing data, assuming these data are considered missing at random. The second will exclude participants who experienced a subsequent new acute traumatic lower-limb injury (or surgery) severe enough to require a period of non-weight-bearing assuming this may have influenced the outcomes of those participants, unless the injury was sustained while completing the trial intervention activities.

Healthcare resource use and productivity

The resources required to deliver each intervention and treatment-related healthcare resource use including co-interventions for knee-related symptoms (eg, medicines, complementary treatments and details of hospital presentations) will be recorded. This information will be collected from several sources (Medicare and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme databases (rebated and out-of-pocket costs), as well as participant logbooks and questionnaires) for the trial period. The Health and Labour Questionnaire63 and the Work Limitations Questionnaire64 will also be collected for the trial period to inform estimates of productivity losses. Methods of cost-effectiveness analysis will be reported elsewhere.

Process evaluation

Semistructured interviews will be conducted on a subset of participants (until data saturation is reached) following the intervention. Interviews will explore beliefs/experiences; knowledge and understanding of interventions received including potential benefits; acceptability and perceived effectiveness of the intervention; and reasons for adhering (or not) to exercise-therapy and education provided. Purposive sampling will be used to recruit interview participants based on characteristics and outcomes of trial. Interviews will be audio recorded, transcribed and analysed using Framework Analysis.65 Data will be coded deductively according to the code structure generated by the interview topic guide, and an inductive thematic analysis will be applied until no new themes emerge.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and clinicians are integral throughout each stage of this project. Patients and clinicians co-designed the intervention, research questions and study methods. This input was gained from: (1) discussions with leading clinicians managing ACL injuries during SUPER development; (2) collation of orthopaedic surgeon–patient education material to inform the control intervention; (3) qualitative interviews with participants and treating physiotherapists from our pilot study as part of formal process evaluation strategies23; (4) qualitative interviews with symptomatic patients with an ACLR as part of our previous studies66; and (5) patient and clinician focus groups providing feedback on study recruitment material, participant handbooks and education content. Preliminary results will be presented and discussed with patient representatives before the results are written up for peer-reviewed publication. Patients and clinicians will provide input into the dissemination of study results by assisting with the decision on what information to share and in what format.

Ethics and dissemination

This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC-19447), the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (HREC 537/19) and Services Australia External Request Evaluation Committee (RMS0879). Written informed consent will be obtained from participants prior to enrolment (online supplemental file 6).

bmjopen-2022-068279supp006.pdf (234.7KB, pdf)

Study outcomes will be widely disseminated through a variety of sources. Primary and key secondary objectives will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal. Other secondary objectives will be addressed in separate publications. Authorship will be in accordance with guidelines provided by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Our publication strategy will be complemented by submission of abstracts to key national and international conferences. Any important protocol amendments will be reported to the approving ethics committees, registered at ANZCTR and communicated in the primary RCT report.

Discussion

ACL injuries and subsequent reconstructions have increased 43% in Australia over the previous 15 years,67 with similar increases observed in the USA,68 and greater increases in England.69 Half of all patients undergoing ACLR will have a poor long-term outcome including persistent symptoms, impaired quality of life and accelerated structural decline.5–7 70 This underscores an urgent need for secondary prevention strategies to prevent symptomatic and structural OA decline—an epidemic of young people with old knees.

The current RCT will be the first to evaluate the symptomatic and structural benefits of a physiotherapist-supervised exercise-therapy and education intervention for young adults at high risk of post-traumatic knee OA. While outcome assessors are blinded to group allocation and physiotherapists delivering the intervention are blinded to the control intervention, owing to the type of interventions (ie, exercise therapy and education), blinding of participants is not possible. The difference in frequency of physiotherapy sessions between the two groups means that the contextual effects related to supervised physiotherapy treatment are also not able to be isolated. We did not include a wait-list control group as this would have reduced equipoise and increased the risk of resentful demoralisation (if used instead of our minimal intervention control) and considerably increased the required sample size (if used as a third comparator group). Furthermore, only patient-reported outcomes are collected at 2-month follow-up to minimise participant burden. We also acknowledge that the wrist-worn activity tracker (Garmin vívofit 4) or other commercial devices that participants wear may under/overestimate daily step counts; however, the differences with research-grade accelerometers appear minimal.71 This fully powered phase III trial represents an important step towards optimising management to achieve better outcomes and curtail the rapid trajectory of post-traumatic knee OA following ACL injury and reconstruction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank physiotherapists, Mick Hughes and Randall Cooper, for assistance in intervention design. We thank the orthopaedic surgeons assisting with participant recruitment: Hayden Morris, Chris Kondogiannis, Nathan White, Mark O’Sullivan, Matthew Evans, Ashley Carr, Justin Wong, Dirk van Bavel, Matthew Alexander, Ben Campbell, Altay Altuntas, Simon Talbot, Raphael Hau, Luke Spencer, David Mitchell. We thank the staff at each of the public hospitals involved in participant recruitment: Lara Kimmel & Susan Liew (Alfred Hospital), Emily Cross & Andrew Bucknill (Royal Melbourne Hospital), Jimmy Goulis & Juliette Gentle (Northern Hospital), Chris Cimoli, David Berlowitz & Andrew Hardidge (Austin Hospital), Peter Choong (St Vincent’s Hospital), Leanne Roddy & Raphael Hau (Box Hill Hospital), Libby Spiers & Phong Tran (Footscray Hospital), Peter Schoch, Katelyn Bailey, Caitlin Knee & Richard Page (Barwon Hospital), Leonie Lewis & David Mitchell (Ballarat Hospital). We thank the physiotherapists involved in treating the participants at Complete Sports Care, Clifton Hill Physiotherapy, Flex Out Physiotherapy, Lake Health Group, Melbourne Sports Physiotherapy, Mill Park Physiotherapy, Symmetry Physiotherapy, Grand Slam Physiotherapy, Melbourne Sports Medicine Centre, Southern Suburbs Physiotherapy Centre, Lifecare La Trobe.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ewa_roos, @Knee_Howells

Contributors: AC, KC, CB, ER, EO and SMM conceived the study and obtained funding. AC, KC and CB designed the study protocol with input from ER, EO and SMM. SMM provided statistical expertise and will conduct primary statistical analysis. EO, RBS and JL provided imaging expertise and will lead imaging analysis. AC drafted the manuscript with input from TJW, KC, CB, ER, EO, SMM, RBS, JL, AMB, BEP, MG, JLC and MJS. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This trial is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (ID: 1158500). AC is a recipient of an NHMRC Investigator Grant (GNT2008523), CB was a recipient of a Medical Research Future Fund Translating Research Into Practice (MRFF TRIP) Fellowship (ID: 1150439).

Disclaimer: The funders have no role in the study design and will not have any role in its execution, data management, analysis and interpretation or on the decision to submit the results for publication.

Competing interests: CB is the owner of a business providing physiotherapy treatment and exercise classes for some participants enrolled in this study. CB will have no role in the decision of which clinic participants attend for study treatment. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2000;8:141–50. 10.5435/00124635-200005000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Culvenor AG, Crossley KM. Accelerated return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a risk factor for early knee osteoarthritis? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:260–1. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, et al. Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1543–52. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culvenor AG, Cook JL, Collins NJ, et al. Is patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis an under-recognised outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A narrative literature review. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:66–70. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culvenor AG, Lai CCH, Gabbe BJ, et al. Patellofemoral osteoarthritis is prevalent and associated with worse symptoms and function after hamstring tendon autograft ACL reconstruction. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:435–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filbay SR, Culvenor AG, Ackerman IN, et al. Quality of life in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1033–41. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, et al. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1756–69. 10.1177/0363546507307396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patterson BE, Culvenor AG, Barton CJ, et al. Patient‐Reported outcomes one to five years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: the effect of combined injury and associations with osteoarthritis features defined on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Care Res 2020;72:412–22. 10.1002/acr.23854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lane NE, Brandt K, Hawker G, et al. OARSI-FDA initiative: defining the disease state of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2011;19:478–82. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery CA, Roos EM, Verhagen E, et al. OARSI clinical trials recommendations: design and conduct of clinical trials for primary prevention of osteoarthritis by joint injury prevention in sport and recreation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:815–25. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittaker JL, Culvenor AG, Juhl CB, et al. OPTIKNEE 2022: consensus recommendations to optimise knee health after traumatic knee injury to prevent osteoarthritis. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:1393–405. 10.1136/bjsports-2022-106299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, et al. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:622–36. 10.1002/art.38290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roos EM, Arden NK. Strategies for the prevention of knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016;12:92–101. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pollard TCB, Gwilym SE, Carr AJ. The assessment of early osteoarthritis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2008;90B:411–21. 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Culvenor AG, Girdwood MA, Juhl CB, et al. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament and meniscal injuries: a best-evidence synthesis of systematic reviews for the OPTIKNEE consensus. Br J Sports Med 2022;56:bjsports-2022-105495–53. 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culvenor AG, Ruhdorfer A, Juhl C, et al. Knee extensor strength and risk of structural, symptomatic, and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:649–58. 10.1002/acr.23005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roos EM, Dahlberg L. Positive effects of moderate exercise on glycosaminoglycan content in knee cartilage: a four-month, randomized, controlled trial in patients at risk of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3507–14. 10.1002/art.21415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munukka M, Waller B, Rantalainen T, et al. Efficacy of progressive aquatic resistance training for tibiofemoral cartilage in postmenopausal women with mild knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1708–17. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koli J, MULTANEN J, KUJALA UM, et al. Effects of exercise on Patellar cartilage in women with mild knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:1767–74. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20., Spindler KP, Huston LJ, et al. , MOON Knee Group . Ten-Year outcomes and risk factors after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a moon longitudinal prospective cohort study. Am J Sports Med 2018;46:815–25. 10.1177/0363546517749850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson B, Culvenor AG, Barton CJ, et al. Poor functional performance 1 year after ACL reconstruction increases the risk of early osteoarthritis progression. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:546–55. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Teichtahl AJ, Abram F, et al. Knee pain as a predictor of structural progression over 4 years: data from the osteoarthritis initiative, a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:250. 10.1186/s13075-018-1751-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson BE, Barton CJ, Culvenor AG, et al. Exercise-therapy and education for individuals one year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:64. 10.1186/s12891-020-03919-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, et al. Spirit 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586. 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. Consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1428–37. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Guermazi A, et al. Early knee osteoarthritis is evident one year following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:946–55. 10.1002/art.39005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Guermazi A, et al. Early patellofemoral osteoarthritis features one year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: symptoms and quality of life at three years. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:784–92. 10.1002/acr.22761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Järvinen TLN, Sihvonen R, Bhandari M, et al. Blinded interpretation of study results can feasibly and effectively diminish interpretation bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:769–72. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andrade R, Pereira R, van Cingel R, et al. How should clinicians rehabilitate patients after ACL reconstruction? A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines (CpGs) with a focus on quality appraisal (agree II). Br J Sports Med 2020;54:512–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skou ST, Roos EM. Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D™): evidence-based education and supervised neuromuscular exercise delivered by certified physiotherapists nationwide. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:72. 10.1186/s12891-017-1439-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skou ST, Thorlund JB. A 12-week supervised exercise therapy program for young adults with a meniscal tear: program development and feasibility study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2018;22:786–91. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American College of Sports Medicine . American College of sports medicine position stand. progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:687–708. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gudbergsen H, Bartels EM, Krusager P, et al. Test-Retest of computerized health status questionnaires frequently used in the monitoring of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized crossover trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:190. 10.1186/1471-2474-12-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med 1991;23:433–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, et al. A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med 2010;363:331–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, et al. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)--development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998;28:88–96. 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins NJ, Prinsen CAC, Christensen R, et al. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS): systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1317–29. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drouin JM, Valovich-mcLeod TC, Shultz SJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the Biodex system 3 pro isokinetic dynamometer velocity, torque and position measurements. Eur J Appl Physiol 2004;91:22–9. 10.1007/s00421-003-0933-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Culvenor AG, Collins NJ, Vicenzino B, et al. Predictors and effects of patellofemoral pain following hamstring-tendon ACL reconstruction. J Sci Med Sport 2016;19:518–23. 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patterson BE, Crossley KM, Perraton LG, et al. Limb symmetry index on a functional test battery improves between one and five years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, primarily due to worsening contralateral limb function. Phys Ther Sport 2020;44:67–74. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gustavsson A, Neeter C, Thomeé P, et al. A test battery for evaluating hop performance in patients with an ACL injury and patients who have undergone ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14:778–88. 10.1007/s00167-006-0045-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ingelsrud LH, Granan L-P, Terwee CB, et al. Proportion of patients reporting acceptable symptoms or treatment failure and their associated KOOS values at 6 to 24 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:1902–7. 10.1177/0363546515584041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oei EHG, van Tiel J, Robinson WH. Quantitative radiologic imaging techniques for articular cartilage composition: toward early diagnosis and development of disease-modifying therapeutics for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1129–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Culvenor AG, Eckstein F, Wirth W, et al. Loss of patellofemoral cartilage thickness over 5 years following ACL injury depends on the initial treatment strategy: results from the KANON trial. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:1168–73. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Lo GH, et al. Evolution of semi-quantitative whole joint assessment of knee oa: MOAKS (MRI osteoarthritis knee score). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:990–1002. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roemer FW, Frobell R, Lohmander LS, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament osteoarthritis score (ACLOAS): longitudinal MRI-based whole joint assessment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:668–82. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Runhaar J, Schiphof D, van Meer B, et al. How to define subregional osteoarthritis progression using semi-quantitative MRI osteoarthritis knee score (MOAKS). Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2014;22:1533–6. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liao Tzu‐Chieh, Jergas H, Tibrewala R, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the contribution of 3D patella and trochlear bone shape on patellofemoral joint osteoarthritic features. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 2021;39:506–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, et al. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the Tampa scale for Kinesiophobia. Pain 2005;117:137–44. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.French DJ, France CR, Vigneau F, et al. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic pain: A psychometric assessment of the original English version of the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia (TSK). Pain 2007;127:42–51. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Roelofs J, Goubert L, Peters ML, et al. The Tampa scale for Kinesiophobia: further examination of psychometric properties in patients with chronic low back pain and fibromyalgia. European Journal of Pain 2004;8:495–502. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Briggs KK, Lysholm J, Tegner Y, et al. The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm score and Tegner activity scale for anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:890–7. 10.1177/0363546508330143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mohtadi N. Development and validation of the quality of life outcome measure (questionnaire) for chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med 1998;26): :350–9. 10.1177/03635465980260030201 10.1177/03635465980260030201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-SD: a measure of health status from the EuroQol group. Ann Med 2001;33:337–43. 10.3109/07853890109002087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fransen M, Edmonds J. Reliability and validity of the EuroQol in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology 1999;38:807–13. 10.1093/rheumatology/38.9.807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lafave MR, Hiemstra L, Kerslake S, et al. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the anterior cruciate ligament quality of life measure: a continuation of its overall validation. Clin J Sport Med 2017;27:57–63. 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roos EM, Boyle E, Frobell RB, et al. It is good to feel better, but better to feel good: whether a patient finds treatment 'successful' or not depends on the questions researchers ask. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:1474–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bruder AM, et al. Let’s talk about sex (and gender) after ACL injury. A systematic review and meta-analysis of self-reported activity and knee-specific outcomes. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Risberg MA, Oiestad BE, Gunderson R, et al. Changes in knee osteoarthritis, symptoms, and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 20-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2016;44:1215–24. 10.1177/0363546515626539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Roijen L, Essink-bot M-L, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Labor and health status in economic evaluation of health care: the health and labor questionnaire. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1996;12:405–15. 10.1017/S0266462300009764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lerner D, Amick BC, Rogers WH, et al. The work limitations questionnaire. Med Care 2001;39:72–85. 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ritchie J, Spencer L, Burgess R, ed. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research, in analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Filbay SR, Crossley KM, Ackerman IN. Activity preferences, lifestyle modifications and re-injury fears influence longer-term quality of life in people with knee symptoms following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a qualitative study. J Physiother 2016;62:103–10. 10.1016/j.jphys.2016.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zbrojkiewicz D, Vertullo C, Grayson JE. Increasing rates of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000-2015. Med J Aust 2018;208:354–8. 10.5694/mja17.00974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mall NA, Chalmers PN, Moric M, et al. Incidence and trends of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the United States. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:2363–70. 10.1177/0363546514542796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abram SGF, Price AJ, Judge A, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction and meniscal repair rates have both increased in the past 20 years in England: Hospital statistics from 1997 to 2017. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:286–91. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-100195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Culvenor AG, Øiestad BE, Hart HF, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:1268–78. 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Modave F, Guo Y, Bian J, et al. Mobile device accuracy for step counting across age groups. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e88. 10.2196/mhealth.7870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whittaker JL, Roos EM. A pragmatic approach to prevent post-traumatic osteoarthritis after sport or exercise-related joint injury. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019;33:158–71. 10.1016/j.berh.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-068279supp001.pdf (99.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068279supp002.pdf (33.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068279supp003.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068279supp004.pdf (878.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068279supp005.pdf (60.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-068279supp006.pdf (234.7KB, pdf)