Abstract

Cerebral hemorrhage, a devastating subtype of stroke, is often caused by hypertension and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Pathological evidence of CAA is detected in approximately half of all individuals over the age of 70 and is associated with cortical microinfarcts and cognitive impairment. The underlying pathophysiology of CAA is characterized by accumulation of pathogenic amyloid β (Aβ) fragments of amyloid precursor protein in the cerebral vasculature. Vascular deposition of Aβ damages the vessel wall, results in blood-brain barrier (BBB) leakiness, vessel occlusion or rupture, and leads to hemorrhages and decreased cerebral blood flow that negatively affects vessel integrity and cognitive function. Currently, the main hypothesis surrounding the mechanism of CAA pathogenesis is that there is an impaired clearance of Aβ peptides, which includes compromised perivascular drainage as well as dysfunction of BBB transport. Also, the immune response in CAA pathogenesis plays an important role. Therefore, the mechanism by which Aβ vascular deposition occurs is crucial for our understanding of CAA pathogenesis and for the development of potential therapeutic options.

Keywords: CAA, BBB, inflammation, intracerebral hemorrhage, amyloid beta

Introduction

Vascular cognitive impairment is an overarching syndrome consisting of vascular lesions, which ultimately lead to dementia—the most severe subset being vascular dementia. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a cerebrovascular, small vessel disease belonging to the vascular cognitive impairment family of diseases. While CAA overlaps in clinical presentation with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), CAA is a form of vascular dementia, while AD is a separate, nonvascular dementia (Thal and others 2012). It is intriguing why these two clinically distinct diseases have several common features including their pathological hallmark, amyloid-beta (Aβ) polypeptides. Indeed, neurodegenerative diseases have many features of cerebrovascular pathology that involve blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, and cerebrovascular diseases show aspects of neurodegeneration, such as neuronal loss and demyelination (Deramecourt and others 2012). Thus, it seems evident that neurodegenerative diseases and cerebrovascular diseases are closely related (Erickson and Banks 2013; Greenberg and others 2020).

CAA is a growing problem as the population ages. CAA prevalence increases with age and is observed pathologically in over half of elderly individuals (Charidimou and others 2017). CAA is characterized by the progressive deposition of Aβ within cortical and leptomeningeal blood vessel walls. Other features include cerebral hemorrhage and progressive dementia in elderly individuals (Biffi and Greenberg 2011; Revesz and others 2003; Yamada 2015). CAA is responsible for 15% to 20% of cases of hemorrhagic stroke in the elderly (Rensink and others 2003) and is present on autopsy in 80% to 90% of patients with AD (Yamada 2015), another disease of aging. Unfortunately, while the prevalence of CAA is high in the elderly, there are no disease-modifying therapies or cures. Understanding the mechanisms underlying CAA pathology and disease progression remains crucial, as the prevalence of age-related diseases continues to rise.

The most common risk factors for CAA are advanced age and AD, but there also are both genetic and nongenetic risk factors. Many of the genes associated with CAA are related to AD pathogenesis and are amyloid-associated proteins or chaperons that lead to increased Aβ production and vascular deposition of Aβ. These genes include apolipoprotein E (APOE), presenilin-1 (PS1), presenilin 2 (PS2), amyloid precursor protein (APP), transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1), alpha1-antichymotrypsin (ACT), neprilysin (NEP), low-density lipoprotein-receptor related protein (LRP-1), and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE; Revesz and others 2003). These will be discussed in further detail in the following sections. Nongenetic risk factors include hypertension, minor head trauma, thrombolytic use, anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapies, and anti-amyloid therapies in treatment of AD (Biffi and Greenberg 2011; Revesz and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Though CAA and AD have similar pathogeneses including the Aβ species involved, there is current, ongoing work to distinguish the two diseases to make an independent CAA diagnosis.

There are few biomarkers associated with CAA that are independent of AD. A decrease in Aβ levels in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) is observed in patients with probable CAA (Charidimou and others 2018; Yamada 2015). Though AD and CAA commonly occur simultaneously, there is a distinct CSF pattern between these two pathologies. Aβ fragments can be 1–40 (Aβ40) or 1–42 (Aβ42) amino acids in length. Aβ40 is commonly associated with the vascular deposits seen in CAA while Aβ42 is observed in the parenchymal plaques of AD patients. The CSF of AD and CAA patients tend to have a lower Aβ42 concentration when compared to healthy controls, which is consistent with Aβ42 deposition in parenchymal plaques (Charidimou and others 2018). In CAA alone, Aβ40 CSF concentrations are lower than both in healthy individuals and AD patients. This is likely due to the selective vascular deposition of Aβ40 that is not seen in AD pathology, and is a distinct hallmark of CAA (Charidimou and others 2018). Aside from Aβ markers in the CSF, a recent study identified neurofilament light (NFL) as a potential biomarker of CAA, as CAA patients had higher levels of NFL compared to the control group (Banerjee and others 2020), a finding that could be useful if validated. Unfortunately, a definitive CAA diagnosis is only obtained at autopsy or via brain biopsy with histological assessment of brain tissue.

Clinically, manifestations of CAA can be hard to interpret due to the ambiguity of its pathognomonic features. The development of hemorrhagic lesions (lobar intracerebral hemorrhage, cortical microhemorrhages, ischemic lesions, and encephalopathies) without other evident cause is a defining characteristic raising concern for a CAA diagnosis. However, many patients present with only subacute cognitive decline, focal neurological deficits, headaches, or seizures rather than hemorrhagic stroke (Biffi and Greenberg 2011). With symptom variations between patients, diagnosis can be difficult and current, ongoing work is attempting to determine a gold standard for care.

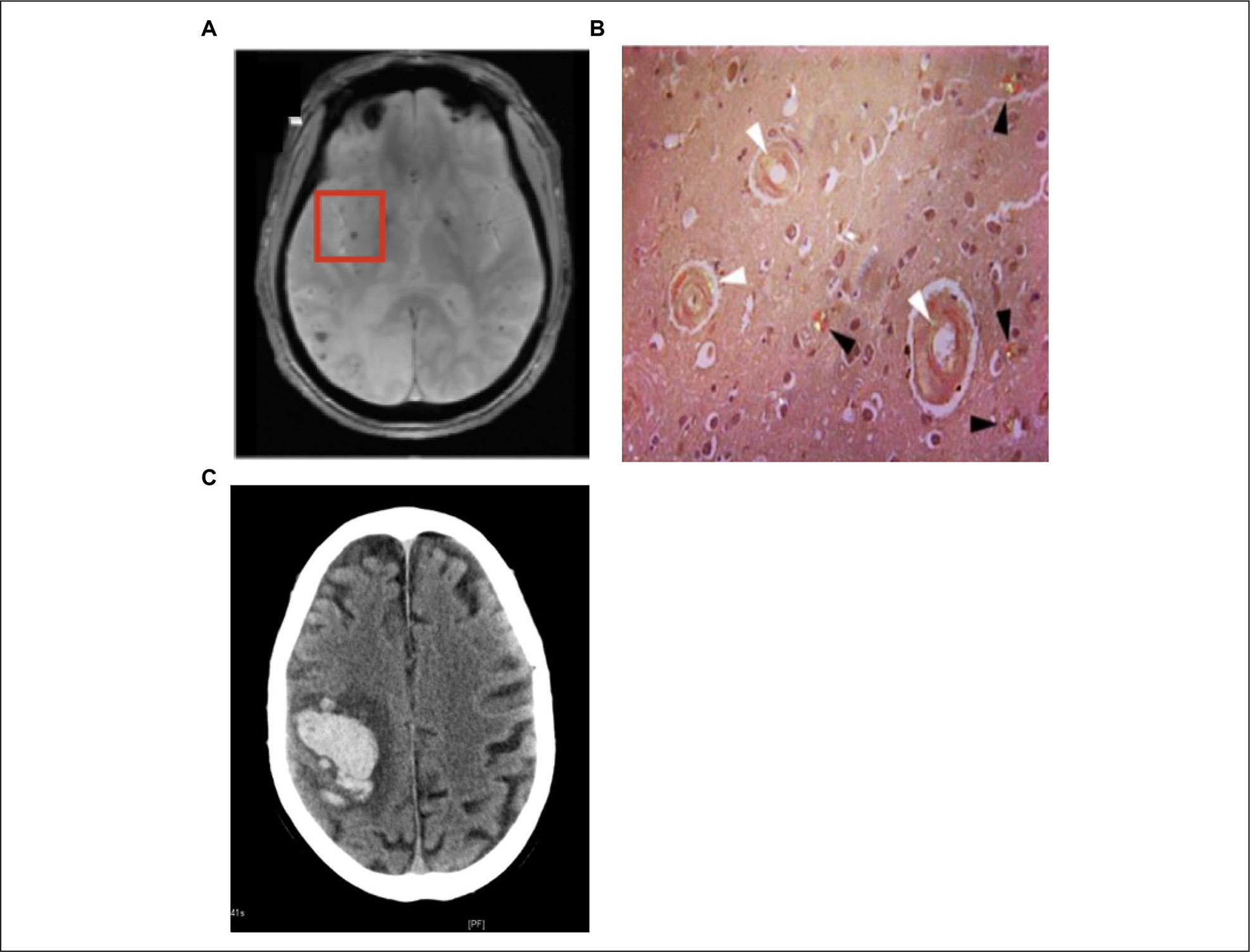

When CAA is suspected, neuroimaging remains the central component to diagnosis of CAA (Fig. 1). This may include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) to identify hemorrhagic lesions, and amyloid positron emission tomography (Amyloid PET). Amyloid PET imaging requires use of amyloid ligands like Pittsburgh compound B and florbetapir, which bind to both parenchymal and vascular amyloids. If PET is negative for parenchymal plaques but positive for vascular deposits, this could suggest a CAA diagnosis; however, lack of a standardized visual assessment protocol makes this difficult (Greenberg and Charidimou 2018; Suppiah and others 2019). Following analysis of neuroimaging results, diagnoses of CAA are made using the Boston Criteria for Diagnoses of CAA (Table 1; Greene and others 1990). Although this is the most commonly used tool for diagnosis, a definitive diagnosis can only be made on autopsy and thus this is a major limitation of these diagnostic criteria. Therefore, while premortem CAA diagnosis remains difficult, advances in neuroimaging and biomarker discovery are overcoming these limitations.

Figure 1.

Pathological findings in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. (A) MRI showing CAA with microhemorrhage (red box). (B) Postmortem tissue from a stroke patient showing diffuse amyloid plaques (black) and CAA (white). (C) This image shows a lobar intracerebral hemorrhage as shown by a CT scan.

Table 1.

Boston Criteria for Diagnoses (Greene and others 1990).

| Classical Boston Criteria for Diagnoses of CAA-Related Hemorrhage | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Definite CAA | • Lobar, cortical, or cortico/subcortical hemorrhage • Severe CAA with vasculopathy and absence of other diagnostic lesion (postmortem) |

| Probable CAA supporting pathology | • Clinical data and pathologic tissue (evacuated hematoma or cortical biopsy) ○ Lobar, cortical, or cortico/subcortical hemorrhage ○ Some degree of CAA in specimen and absence of other diagnostic lesion (does not have to be postmortem) |

| Probable CAA | • Clinical data and MRI or CT demonstrating: ○ Multiple hemorrhages restricted to lobar, cortical, or corticosubcortical regions (cerebellar hemorrhage allowed) ○ Age ≥55 years ○ Absence of other cause of hemorrhage ○ Pathological confirmation not required |

| Possible CAA | • Clinical data and MRI or CT demonstrating: ○ Single lobar, cortical, or corticosubcortical hemorrhage ○ Age ≥55 years ○ Absence of other cause of hemorrhage |

CAA = cerebral amyloid angiopathy; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; CT = computed tomography.

A CAA diagnosis can fit into two subtypes: familial CAA or sporadic CAA. Familial CAA is often more severe with an earlier age of onset, and death occurs within a decade of symptom onset in most cases (Biffi and Greenberg 2012). In AD, the amyloid cascade hypothesis, first described in 1992 and modified in 2002, describes the differences between familial and sporadic AD (Hardy and Selkoe 2002; Hardy and Higgins 1992). This hypothesis suggested that familial AD was due to missense mutations in APP or PS1, leading to increased Aβ production (Hardy and Selkoe 2002; Hardy and Higgins 1992). In contrast, sporadic AD was thought to be due to a failure of Aβ clearance (Hardy and Selkoe 2002; Hardy and Higgins 1992). Thus, similar to AD, most familial cases of CAA result from cleavage of APP and point mutations occurring within the Aβ peptide-coding region of APP (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The genetic mutations most often associated with familial CAA in APP include the Dutch, Italian, Iowa, Flemish, Icelandic, Arctic, familial British, and familial Danish types of CAA (Biffi and Greenberg 2011; Revesz and others 2003). All of these APP point mutations have their own set of symptomology, yet all lead to increased vascular Aβ deposits and the onset of CAA.

Table 2.

Gene Mutations Associated with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA).

| Gene Mutations Associated with Human CAA | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Mutations in APP Associated with Familial CAA | Neuropathology of Gene Mutation |

|

| |

| Dutch mutation (E693Q) | Severe vascular deposition of Aβ, hemorrhages, and diffuse plaques in brain parenchyma |

| Italian (E693K) | Severe vascular deposition of Aβ, multiple strokes |

| Iowa (D694N) | Severe vascular deposition of Aβ, hemorrhages, and diffuse plaques in brain parenchyma |

| Flemish (A692G) | Vascular deposition of Aβ and diffuse plaques in brain parenchyma |

| Icelandic (A673T) | Protective against amyloid deposition in plaques, but have vascular deposition |

| Arctic (E693G) | Vascular deposition of Aβ and diffuse plaques in brain parenchyma |

|

| |

| Other Gene Mutations Associated with Familial CAA | Neuropathology of Gene Mutation |

|

| |

| Presenilin 1 (L282V) | Severe vascular deposition of Aβ and diffuse plaques in brain parenchyma |

| Presenilin 2 (N141I) | Vascular deposition of Aβ and diffuse plaques in brain parenchyma |

| Transforming growth factor-β1 | Severe vascular deposition of Aβ |

| Alphal-antichymotrypsin | Vascular deposition of Aβ |

| Neprilysin | Vascular deposition of Aβ |

| Low-density lipoprotein-receptor related protein | Vascular deposition of Aβ |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme | Vascular deposition of Aβ |

|

| |

| Non-Aβ Gene Mutations Associated with Familial CAA | Neuropathology of Gene Mutation |

|

| |

| Cytstatin C | Systemic amyloidosis |

| Prion protein | Progressive cognitive decline |

| ABri/Adan | Progressive dementia, cerebellar ataxia |

| Thansthyretin | Systemic amyloidosis polyneuropathy |

| Gelsolin | Systemic amyloidosis |

| Immunoglobulin light chain amyloid | Systemic amyloidosis |

|

| |

| Gene Mutations Associated with Sporadic CAA | Neuropathology of Gene Mutation |

|

| |

| APOE ε2 | Vascular deposition of Aβ |

| APOE ε4 | Vascular deposition of Aβ including capillary vessels |

Figure 2.

APP processing mechanisms and familial mutations. A protein sequence from amino acid residue 663–720 is presented, with the amino acid sequence for Aβ shown in red. β and γ secretases are responsible for the cleavage of Aβ from APP, whereas α-secretase leads to a non-amyloidogenic cleavage product. A number of known pathogenic point mutations within APP (with the listed mutation alias if known) identified in cases of familial CAA are shown.

Early-onset familial CAA also results from a variety of loss-of-function mutations in certain functional genes previously mentioned and listed in Table 2. PS1 and PS2 genes cleave APP into Aβ fragments with mutations leading to increased production of Aβ fragments. A TGF-β1 polymorphism increases Aβ vascular affinity and deposition while decreasing Aβ load in parenchymal plaques (Wyss-Coray and others 2001). Mutations in degrading enzymes and transporters such as ACT, LRP-1, NEP, and ACE decrease the ability to clear and degrade Aβ, resulting in the failure of brain clearance of Aβ at multiple levels (Revesz and others 2003). Such loss of function mutations that lead to increased formation of Aβ deposits include both ACT, a serine-proteinase inhibitor that regulates formation of Aβ fibrils, and LRP-1, a plasma membrane receptor that mediates clearance of Aβ from the brain (Revesz and others 2003; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015). The insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) degrades the Aβ peptide, and its activity is thought to be inhibited or inactivated in CAA pathogenesis, resulting in an inability to degrade Aβ protein (Grimm and others 2013; Hemming and Selkoe 2005). The focus of this review is centered on CAA related to the processing of Aβ protein, but other genetic mutations have been identified outside of APP/Aβ processing (e.g., cystatin C, prion protein, ABri/ADan) and are listed in Table 2 (Revesz and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Cases of familial CAA are rare, and most cases are associated with sporadic CAA.

The most common genetic factors associated with sporadic CAA are the presence of polymorphisms in the APOE ε2 or ε4 alleles (Table 2; Revesz and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Apolipoproteins bind to fat-soluble molecules, such as the observed APOE interactions with both soluble and aggregated Aβ, illustrating APOE’s importance in CAA (Russo and others 1998). Depending on which allele of APOE is present, there are differences in Aβ accumulation in vessels, thus further subdividing sporadic CAA into Type 1 or Type 2. CAA Type 1 involves both capillaries and larger vessels and is observed in higher frequency in patients with the APOE ε4 allele mutation. CAA Type 2 is observed in higher frequency with the APOE ε2 allele mutation, but involves larger arteriolar vessels and lacks involvement of cortical capillaries, and is more prevalent compared to CAA Type 1 (Thal and others 2002). While CAA-laden vessels including leptomeningeal arteries and penetrating arterioles predominantly accumulate Aβ40, the composition of amyloid-beta species in capillaries is mostly Aβ42, resembling the composition in neuritic plaques and further distinguishing the capillary CAA from other vessels with amyloid deposition (Greenberg and others 2020). Though genetic research has brought different genes responsible for CAA to light, diagnosis is still difficult and the genetic cases account for only a very small subset of patients. Other nongenetic, vascular risk factors are associated with sporadic CAA and disease progression, including obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, stress, and old age (Foidl and Humpel 2019).

A unique subset of CAA patients have CAA-related inflammation (CAARI), where amyloid deposition is accompanied by vasculitis or perivasculitis. CAARI manifests as subacute neurobehavioral symptoms and cognitive decline, headaches, seizures, and stroke-like signs (Kirshner and Bradshaw 2015). Neuroimaging shows lesions in the cortex and subcortical white matter, asymmetric and multifocal white matter hyperintensity (WMH) with multiple cerebral bleeds, and an autoimmune and inflammatory response in CAA-affected vessels (Kirshner and Bradshaw 2015; Nortley and others 2019). CAARI typically responds well to immunosuppressive and corticosteroid therapies (Kirshner and Bradshaw 2015). Genetically, the homozygous APOE ε4 allele mutation is strongly associated with CAARI (Kirshner and Bradshaw 2015; Nortley and others 2019). The mechanism of the inflammation observed in CAARI is not well understood, but it is speculated that the inflammation is an autoimmune response to the vascular deposits (Kirshner and Bradshaw 2015; Nortley and others 2019). CAARI affects only a rare population and more studies are needed to determine the mechanisms of CAARI.

Pathophysiology of CAA

Clinical Pathogenesis

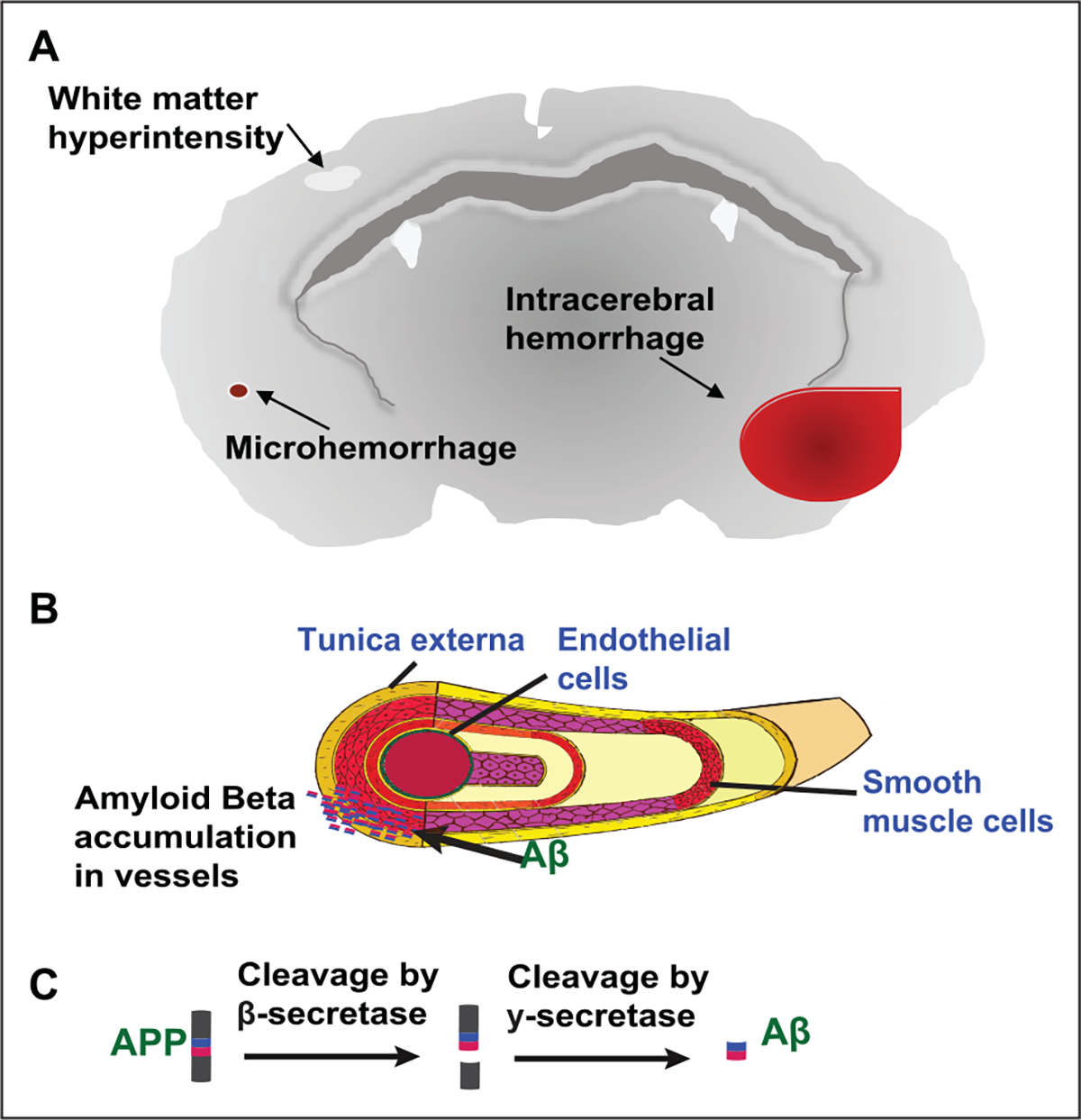

CAA pathophysiology shows Aβ deposition in small to medium-sized arteries, mainly the leptomeningeal and cortical vessels of the cerebral and cerebellar cortices with topographical distribution favoring the posterior brain regions (e.g., occipital lobes; Biffi and Greenberg 2011; Yamada 2015). In CAA Type 1, Aβ is also observed in capillaries in addition to larger arteriolar vessels (Thal and others 2002). Vascular deposits of Aβ are uncommon in other brain areas, including the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem (Rensink and others 2003; Vinters 1987; Yamada 2015). The development of CAA is progressive with advancing age, and as Aβ accumulation becomes more prominent, weakened vessel walls and blood vessel ruptures occur. The seminal clinical presentations of CAA pathology are widespread microhemorrhages, seen by MRI, and lobar cerebral hemorrhages as a result of Aβ vasculature disruption (Fig. 3A; Attems and others 2007; Biffi and Greenberg 2011). WMHs are another common manifestation of CAA (Fig. 3A). In line with the posterior preference for Aβ accumulation in CAA, WMH distribution in the posterior region of the brain is often seen on imaging studies (Gurol and Greenberg 2013; Yamada 2015; Zhu and others 2012). One study describes CAA-related WMH pattern as “multiple spots associated with lobar cerebral microbleeds” (Charidimou and others 2016). CAA is associated with white matter abnormalities, including white matter lesions, impaired cognition, and recurrent hemorrhages (Smith and others 2004). Essentially, these studies illustrate the underlying small vessel disease associated with microhemorrhages and WMH and relate the functional changes seen in the clinic with the pathophysiology of the disease.

Figure 3.

Pathophysiology of CAA. (A) CAA pathology shows the presence of microhemorrhages, lobar cerebral hemorrhage, white matter hyperintensities, dilation of perivascular spaces, and has a preference for occipital lobe. (B) Aβ deposition occurs in small leptomeningeal or cortical vessels. (C) APP is cleaved by β-secretase and γ-secretase into Aβ fragments.

One study implied that a decreased posterior cerebral artery (PCA) response to physiological stimuli is mediated by the severity of CAA (Smith and others 2008). Reduction of blood flow to the PCA is important as it supplies the occipital lobe, where vascular Aβ accumulation preferentially deposits and the temporal lobes, where Aβ accumulation can also be observed, though less common (Gurol and Greenberg 2013). The PCA also supplies the hippocampus and this altered blood flow may lead to the memory dysfunction seen in AD, CAA, and vascular dementia patients (Smith and others 2008). Overall, recent findings support the emerging theory that CAA is a result of impaired Aβ clearance and vascular flow alterations. The disruption in blood flow caused by capillary occlusion due to changes in smooth muscle cells (SMC) and Aβ deposition is supported by MRI and CT imaging where ischemic lesions and microinfarcts are observed. Additional clinical findings provide evidence for impairment in the clearance of Aβ, and to the new concept that the CNS waste drainage through perivascular spaces (PVS) may be an important mediator of CAA development (Benveniste and others 2019; Biffi and Greenberg 2011). PVS, or Virchow-Robin spaces, are microscopic pial-lined, fluid-filled structures with an assumed immunologic role including Aβ clearance. The dilation of these PVS is common with age and CAA, and these become visible on MRI due to the accumulation of Aβ in these areas (Gurol and Greenberg 2013). Additionally, the total cerebral clearance rate of Aβ in AD patients show a 25% to 30% decrease compared to age-matched controls, while Aβ production remained stable, indicating that impairment of Aβ clearance mechanisms may be critically important in the development of AD and CAA (Mawuenyega and others 2010). Thus, it is reasonable to surmise that CAA may be a disease of impaired Aβ clearance (Greenberg and others 2020).

CAA severity classification is based on a neuropathological grading system. Initially (mild CAA), Aβ deposits are restricted to the outer rim (known as the Congophilic rim due to positive staining of the Congo red stain for amyloidosis) of normal or atrophic SMCs in media of otherwise normal vessels containing an intact vessel wall (Rensink and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Deposition occurs in the outer portion of the basement membrane, at the media to adventitia junction (Fig. 3B). In moderate CAA, the media is replaced by Aβ deposition and the vessel wall is disturbed, losing the majority of the surrounding SMCs (Rensink and others 2003). Severe CAA shows extensive amyloid deposition in almost all small to medium-sized vessels. In arterioles, the amyloid deposition weakens the vessels walls by causing cracks and focal fragmentation due to degeneration of SMCs (Magaki and others 2018; Rensink and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Initial ultrastructural examination of CAA arterioles demonstrated a thinned, but relatively preserved endothelium (Vinters and others 1994); however, many recent studies now show degeneration of endothelial cells (ECs) in severe CAA (Magaki and others 2018). In capillary CAA, degeneration of ECs and decreased expression of the inter-endothelial tight junction proteins is often observed (Magaki and others 2018; Rensink and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Loss of vessel wall integrity leads to the presence of at least one site of microhemorrhage and perivascular leakage in severe CAA. While clinical studies help elicit the pathophysiology of CAA, laboratory studies are essential in finding the biochemical changes that initiate the pathogenesis of the disease.

Understanding the mechanisms of CAA pathogenesis has been advanced by the use of experimental animal models. Naturally occurring animal models develop CAA with aging, including cats, dogs, and nonhuman primates; however, there are many limitations to these animal models. These include increased variability in the extent of CAA in animals of similar age and ethical concerns raised when designing protocol approvals for studying them at advanced age, especially since they are low throughput models. Therefore, the most commonly used model systems are transgenic mice expressing human APP. Approximately 10 transgenic mouse models used to study CAA exist; however, only a few will be discussed here. The APP23 mouse model expressing human APP isoform 751 contains a double Swedish mutation under the control of neuron-specific Thy-1 promoter (Sturchler-Pierrat and others 1997). This model exhibits the extracellular deposition of Aβ plaques in brain parenchyma observed in AD and extensive vascular amyloid deposition in arterioles and capillaries with accompanying microhemorrhages (Sturchler-Pierrat and others 1997). The APP23 mouse model provides evidence for deposition of neuron-derived Aβ in vessel walls, causing vessel wall disruption and leading to parenchymal hemorrhage suggesting a transport and/or drainage pathway as the primary mechanism of vascular amyloid deposits. The Tg2576 mouse model of AD overexpresses the Swedish mutation under control of the PrP promoter (Hsiao and others 1996). These mice exhibit age-dependent amyloid deposition by 11 to 13 months of age in brain parenchyma similar to AD but also exhibit some vascular amyloid deposition (Fig. 4A). The TgSwDI mouse model of CAA contains a Dutch, Iowa, and Swedish mutation within APP (Davis and others 2004). TgSwDI mice exhibit gliosis and vascular deposits of Aβ in the neocortex and hippocampus by 6 months of age (Fig. 4B) and cognitive impairment begins as early as 3 months, becoming more severe with age. Last, mice overexpressing TGF-β1 alone or with human APP (Wyss-Coray and others 2000) have accelerated vascular deposition of human Aβ concomitant with decreased Aβ deposition in brain parenchyma (Wyss-Coray and others 2000; Wyss-Coray and others 2001). A variety of animal models exist for AD, CAA, and vascular dementia studies; however, the pathogenesis and symptomology of each transgenic model differs and should be considered in terms of the study goals.

Figure 4.

Ex vivo two-photon depiction of vascular amyloidosis using methoxy X04 amyloid dye. (A) A representative image showing a 12-month Tg2576 brain section with more punctate amyloids. (B) A representative image showing a 6-month TgSwDI brain section with vascular amyloidosis surrounding capillaries. (C) A representative image showing a 6-month TgSwDI brain section with large vessel amyloid accumulation following SMC pattern rings.

Molecular Pathogenesis

Generation of Aβ fragments occurs from the proteolytic sequential cleavage of APP by β-secretase and γ-secretase (Figs. 2 and 3C; Yamada 2015). Aβ fragments are produced by multiple types of cells and are mainly 40 or 42 amino acids in length, though the generation of several other Aβ species occurs (Selkoe 1994). The current understanding of CAA, although still controversial, indicates that Aβ42, more commonly observed in amyloid plaques seen in brain tissue of AD patients (Van Dorpe and others 2000; Weller and others 2008; Yamada 2015), acts as a “seed” and initiates the formation of the vascular Aβ deposits (McGowan and others 2005). However, Aβ40 predominates compared to Aβ42 in these deposits, and thus, Aβ40 is the major amyloid fragment present in the vessel walls (Van Dorpe and others 2000; Weller and others 2008; Yamada 2015). Differences in production of Aβ are thought to arise from different subtypes of neuronal APP and endothelial APP, both in their expression levels, and in their sequences and regulatory mechanisms (Brannstrom and others 2018). However, the cellular origin of the Aβ deposited in the abluminal surface of vessel walls is still a point of contention. There are two competing hypotheses that suggest that it is either neuronal or ECs that primarily contribute to the vascular Aβ deposits in CAA (Revesz and others 2003; Weller and others 2008), while they are not mutually exclusive. The vascular hypothesis suggests that Aβ is produced in cerebrovascular cellular elements such as ECs, SMCs, and/or pericytes that line the vessel walls (Frackowiak and others 1994; Vinters and others 1996). This hypothesis is supported by the morphological observations showing that Aβ deposits are closely associated with cerebrovascular SMCs (Fig. 4; Frackowiak and others 1994; Vinters and others 1996). The drainage hypothesis proposes that increases in Aβ production occur solely in neurons and deposition of Aβ into vessels is a result of poor clearance from the perivasculature, leading to accumulation of Aβ along vascular drainage pathways (Weller and others 2008).

Studies using the APP23 mouse model have helped the drainage hypothesis emerge as the consensus view on how Aβ accumulation occurs within cerebral vessels. The APP23 mouse model showed similar vascular Aβ deposition as that seen in human samples, with a preference for deposition in the arterioles and capillaries (Biffi and Greenberg 2011; Calhoun and others 1999). This suggests a CAA phenotype and provided evidence for deposition of neuronal-derived Aβ in vessel walls since the mutation in APP23 mice is under the control of a neuronspecific promoter. This study also showed that Aβ directly injected into the brain and/or CSF was cleared to the blood while Aβ injected into the blood was sequestered within the cerebrovasculature. This suggests that neuronderived Aβ flows into the CSF where it can accumulate within the vascular and perivascular spaces (Calhoun and others 1999). Ultimately, the pathophysiology of CAA is closely tied to AD pathology and may occur due to both the overproduction and impaired clearance of these pathogenic amyloid peptides.

The mechanism of Aβ deposition into vessel walls is poorly understood. As identified by electron microscopy studies, Aβ deposition in CAA occurs on the cerebrovascular basement membrane (CBM) of arteries and arterioles, as well as on the basal lamina of capillaries. The interstitium between the SMCs of the arterial tunica media is also a preferential region for aggregated Aβ accumulation (Weller and others 1998; Wisniewski and Wegiel 1994). The CBM is a heterogenic, specialized sheet of extracellular matrix composed of glycoproteins (collagen IV, laminin, nidogen) and proteoglycans (agrin, perlecan, fibronectin; Banerjee and Bhat 2007). The CBM surrounds the basal side of all endothelial cells and is found between ECs and SMCs in arterioles. In capillaries, the basal lamina is found between ECs and pericytes or astrocytes (Morris and others 2014). The CBM plays an important role both structurally and functionally in blood vessel health and development, and maintenance of the BBB (Banerjee and Bhat 2007). Thickening of the CBM occurs with age in both rodents and humans and appears to predominate in brain areas susceptible to CAA pathology (Hawkes and others 2013). In TGF-β1 mice, CBM thickening was shown to precede CAA onset (Wyss-Coray and others 2000), while in humans, the presence of the APOE ε4 genotype observed in CAA Type 1 patients enhanced CBM thickening and change in composition (Banerjee and Bhat 2007). These changes in CBM composition may make the vessels susceptible to accumulation of vascular Aβ deposits. Following thickening of the CBM and onset of CAA, the entire neurovascular unit (including ECs, SMCs, and mural cells) undergoes degeneration in amyloid-laden vessels (Magaki and others 2018; Morris and others 2014), an important feature of CAA pathology. Thus, Aβ toxicity at the vessel wall is attributed to this cellular degeneration that reduces vessel wall integrity and results in BBB leakiness, vessel occlusion or rupture, and leads to hemorrhages and decreased cerebral blood flow that affects cognitive function such as learning and memory (Bell and Zlokovic 2009; Smith and others 2008; van Veluw and others 2020a). Therefore, the mechanism by which Aβ vascular deposition occurs is crucial for understanding CAA pathogenesis and for the development of potential therapeutic options.

Impaired Clearance Mechanisms of Aβ May Enhance Disease Pathology

Electron microscopy studies analyzed the vascular Aβ deposits and suggested that CAA resulted from impaired clearance of Aβ (Weller and others 1998; Wisniewski and Wegiel 1994). Aβ follows the same perivascular elimination pathway as normal brain toxins in both mice and humans (Hawkes and others 2013; Morris and others 2014), suggesting that CAA follows a preexisting route for elimination of cerebral Aβ. After production in the brain, Aβ is cleared through both enzymatic and nonenzymatic pathways (Fig. 5). Enzymes such as NEP, ACE, IDE, the matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, −3, and −9), glutamate carboxypeptidase II, and others readily degrade Aβ peptides (Fig. 5B; Grimm and others 2013; Hemming and Selkoe 2005; Morelli and others 2004; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015; Yoon and Jo 2012). Many of these enzymes are impaired with aging, disease pathology, and with genetic mutations leading to decreased enzymatic activity and a failure to degrade Aβ protein (Grimm and others 2013; Hemming and Selkoe 2005; Morelli and others 2004). Alternatively, Aβ is taken up from the extracellular space by phagocytic microglia cells and astrocytes and then degraded (Fig. 5C; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015). In CAA-affected vessels, clusters of activated microglia and astrocytes surround the vascular Aβ deposits (Akiyama and others 2000; Carrano and others 2012) and glial activation helps delay disease progression by phagocytosing Aβ from the brain parenchyma (Wyss-Coray 2006). If Aβ is not degraded by enzymes or phagocytic cells, Aβ is cleared non-enzymatically. Aβ is released into the interstitial fluid (ISF), diffuses thorough the extracellular space, moves along the perivascular spaces or is transported across the BBB (Fig. 5D and E; Morris and others 2014; Revesz and others 2003; Shibata and others 2000; Weller and others 2008).

Figure 5.

Clearance mechanisms of Aβ. (A) Aβ is produced by the cleavage of APP in neurons. (B) Aβ can be enzymatically degraded. (C) Aβ can be phagocytosed by glial cells. (D) Aβ can be cleared across the BBB by transendothelial waste clearance mechanisms. (E) Aβ can be cleared through perivascular drainage pathways. (F) Aβ accumulation in vessels leads to CAA. (G) Aβ accumulation in the brain parenchyma is observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

Until recently, it was speculated that the majority (75%) of Aβ was cleared from the brain by transport across the BBB whereas only 10% of Aβ was cleared from the brain parenchyma by ISF bulk flow into the perivascular space (Shibata and others 2000; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015; Zlokovic 2008). Recent studies using two-photon imaging have suggested that the existence of perivascular drainage, which involves CSF and ISF bulk flow, in particular the glymphatic system, actually contributes to a greater portion of Aβ clearance than previously recognized (Kress and others 2014; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015). Aggregation of Aβ is initiated when the monomeric forms assemble together and then continue to progress. The physicochemical property of these monomers, including the lipid-water solubility, may influence their interactions with solutes and CBM components, which also change with aging. In the review article by Hladky and Barrand (2018), which attempted to address conflicting literature regarding efflux via the perivascular route and the transport across the BBB, the clearance rate of Aβ was considerably faster than that of the fluid space marker inulin, indicating the significance of BBB-mediated clearance of Aβ over the clearance mediated by aqueous flux along with the perivasculature (Hladky and Barrand 2018). However, both clearance mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and while it is still unclear which clearance system predominates, a failure in any part of these clearance pathways may cause enhanced accumulation of vascular amyloid. Thus, these clearance pathways have emerged as key mechanisms of CAA pathology and have been the recent focus of many CAA studies.

Perivascular Aβ Clearance Pathways

While the anatomical foundation/structure of the perivascular space requires further investigation, one plausible component is the basement membrane itself, which potentially regulates the perivascular distribution of CSF (Engelhardt and Sorokin 2009; Howe and others 2018a; Thomsen and others 2017). Perivascular fluid distribution may facilitate the clearance of waste materials from the brain parenchyma (Morris and others 2014). Solutes in the ISF reach the perivascular space and their clearance is facilitated by multiple potential pathways (Albargothy and others 2018; Iliff and others 2012). Currently, the mechanisms for CSF-ISF solute exchange are a matter of debate. The review by Hladky and Barrand (2018) summarized the possible routes of perivascular transfer of solutes as extramural paths including the brain extracellular spaces and basement membrane as well as the intramural paths through the perivascular basement membrane (Hladky and Barrand 2018). Molecular characterization of perivascular pathways have been comprehensively reviewed (Hannocks and others 2018), including the spatial localizations of several types of CBM with specific laminin-α subtypes.

There are at least four different mechanisms involved in perivascular clearance that have been postulated: (1) para-arterial influx of the CSF occurs followed by a mixing of CSF with ISF in the brain parenchyma driven by convection, and then paravenous efflux (Dickstein and others 2016; Iliff and others 2012; Iliff and others 2013; Kress and others 2014; Xie and others 2013); (2) peri-arterial CSF influx through the vascular CBM and peri-arterial ISF efflux (Albargothy and others 2018; Hawkes and others 2012); (3) CSF retention in the paravascular spaces occurs on the surface of the brain (Ma and others 2019); and (4) CSF distribution through all vessel types (Lochhead and others 2015; Pizzo and others 2018). Thus, while all of the above-mentioned studies support the observation that perivascular solute distribution occurs, the kinetics and physiological mechanisms that produce this phenomenon remain unclear. However, compelling evidence for vasomotor-driven paravascular drainage of solutes, including Aβ, was very recently shown by van Veluw and others (2020b), who used two-photon microscopy to visualize low-frequency arteriolar oscillations that mediate clearance (van Veluw and others 2020b).

Recent identification of the glymphatic clearance (glial lymphatics) system (Mader and Brimberg 2019) provides an attractive explanation for cerebral waste clearance beyond enzymatic degradation in the brain and transporter-mediated efflux across the BBB. The glymphatic clearance system consists of perivascular influx of CSF, subsequent ISF bulk-flow, which drives removal of brain extracellular solutes, including secreted Aβ. ISF solutes move through the brain parenchyma and the perivascular drainage at the venous vasculature facilitates the efflux out from brain. These are mediated through convective fluid fluxes with rapid interchanges of CSF and ISF due to arterial pulsatility, respiration, and CSF pressure gradients (Greenberg and others 2020; Jessen and others 2015; van Veluw and others 2020b). Here, solutes are cleared by CSF bulk flow into the peri-arterial space along the CBM and SMCs and then exported into the ISF space by the astroglial water channel, aquaporin-4 (AQP4), across astrocytic endfeet into brain parenchyma. The waste solutes are transported toward the perivenous compartment of veins where it exits into lymphatic vessels and the systemic circulation (Charidimou and others 2012; Iliff and others 2012; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015).

The glial water channel, AQP4, is found in perivascular astrocytic end feet and plays an important role in glymphatic function (Jessen and others 2015), regulates brain water homeostasis, and is upregulated in reactive astrocytes during brain injury, including AD (Mader and Brimberg 2019; Smith and others 2019; Xu and others 2015). CSF recirculation is driven by active fluid transport of its water component across AQP4 channels from the peri-arterial space into the brain parenchyma, across the interstitium where it mixes with ISF, and into perivenous spaces for either recirculation with CSF or eventual absorption into the lymphatic system (Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015). During this circulation, AQP4 is responsible for the clearance of Aβ and preventing its aggregation (Mader and Brimberg 2019). The importance of AQP4 in the glymphatic system in Aβ clearance was supported by a study using AQP4 knockout mice (Iliff and others 2012). AQP4 knockout mice had significantly reduced Aβ clearance compared to wild-type mice (Iliff and others 2012), suggesting a possible role of the glymphatic system in Aβ clearance. Newer work has found more evidence supporting AQP4 as a mediator of astrocytic and microglial recruitment to periplaque areas (Smith and others 2019). In this study, the AD mouse mice 5xFAD (APP and PSEN1 overexpression model) was bred with an AQP4 knockout (KO) mice. When compared to control, increased amyloid deposition was found in the 5xFAD/AQP4 KO pups and 5xFAD/AQP4 KO pups had a lower density of astrocytic processes and less microglial activation in the periplaque area (Smith and others 2019). This suggests a novel mechanism behind AQP4 where depletion of AQP4 works to alter periplaque astrocytes and microglial recruitment resulting in reduced Aβ clearance (Smith and others 2019).

In CAA and normal aging, the perivascular drainage pathway moves the solutes into the peri-arterial space along the CBM in capillary walls and SMCs in the direction opposite to blood flow (Charidimou and others 2012; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015) and is known to be impaired, especially in the presence of the APOE ε4 allele (Revesz and others 2003; Yamada 2015). Similar to perivascular drainage pathways, glymphatic clearance is reduced in aging (Kress and others 2014). Considering the CBM remodeling and hypertrophy observed in AD and CAA, additional studies to identify therapeutic targets of the clearance pathways are highly warranted in treatment of CAA.

Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in CAA

Aβ Clearance across the BBB

The BBB is formed by the ECs, which are interconnected by tight junctions and adherence junctions to seal paracellular clefts. Other cell types in the neurovascular unit also contribute to maintenance of BBB function. For example, astrocytes project their end-feet to capillary blood vessels while pericytes ensheathe the ECs. Both astrocytes and pericytes contribute to regulating the EC response including barrier function and mechanical contractile action. The transendothelial waste clearance across the BBB depends on many factors, including solubility, size of the molecules, the presence of active transporters, and adsorption mediated membrane transport. Given the small size of the Aβ protein, it can move freely through the astrocytic end-feet of the glial barrier; however, the endothelial tight junctions at the BBB prevent the free passage of Aβ into the blood (Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015).

Transport of Aβ across the BBB is mediated mainly through the LDL receptor family (such as the LRP-1 receptor) or the ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC transporters, most common being ABCB1; Erdo and Krajcsi 2019; Pereira and others 2018; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015). Age-related changes in transport across the BBB and decreased expression of the blood efflux transporters, LRP-1 and ABCB1, in CAA, reduces clearance of Aβ and enhances vascular deposition (Erdo and Krajcsi 2019; Pereira and others 2018; Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015). Interestingly, the rate of LRP-1 transport of Aβ40 across the BBB occurs more efficiently than Aβ42, suggesting an isoform specific degradation mechanism that may affect vascular deposition when LRP-1 expression is decreased (Yoon and Jo 2012). Further affecting clearance of Aβ by the transporters is the presence of the APOE ε4 allele in CAA. Normally, APOE (a cholesterol transporter) helps mediate clearance of Aβ by competing with Aβ for efflux by LRP-1. The presence of the ε4 allele reduces efficiency of APOE in mediating clearance and likely contributes to enhancement of vascular deposition (Tarasoff-Conway and others 2015).

The ABC transporters are affected by aging under both physiological and pathological conditions (Erdo and Krajcsi 2019; Jia and others 2020). The main ABC transporter responsible for Aβ efflux is ABCB1, or P-glycoprotein1 (Hartz and others 2010; Jia and others 2020). In humans, ABCB1 expression and function decreases with aging, leading to enhanced permeability and potentially, toxicity (Erdo and Krajcsi 2019; Jia and others 2020; Silverberg and others 2010). In AD studies, the expression of Aβ decreases expression of ABC transporters, further exacerbating the accumulation of Aβ (Erdo and Krajcsi 2019; Pereira and others 2018). The decrease in expression of ABCB1 was recently attributed to Aβ40 induced degradation of ABCB1 through the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway in brain capillaries isolated from AD patient samples (Hartz and others 2016; Hartz and others 2018). The reduction in efficacy and age-related changes in transport across the BBB leads to enhanced vascular deposition of Aβ in the elderly.

The main transporter responsible for influx of Aβ across the BBB into the brain parenchyma is Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (Deane and others 2003; Deramecourt and others 2012). In contrast to the decreased expression of the blood efflux transporters, LRP-1 and ABCB1, in CAA, RAGE transport capacity increases with aging (Pascale and others 2011; Silverberg and others 2010), and in AD (Donahue and others 2006) causing an increased amyloid burden in the aging brain. Overall, while the efflux transport across the BBB reduces with aging, influx transport increases, which suggests that age-dependent net clearance capacity shifts toward the containment of Aβ in the brain.

In addition to the changes in BBB permeability observed through altered transendothelial waste clearance, the paracellular barrier function plays a critical role in the integrity and composition of the BBB in CAA. A mechanistic understanding of how vascular Aβ deposition induces changes in BBB permeability is crucial. A complex network of tight junction proteins regulates integrity and paracellular permeability of the ECs. When looking at expression levels of tight junction proteins in CAA, many were found to have decreased expression levels in CAA-laden vasculature compared to healthy controls (Marco and Skaper 2006; Tai and others 2010). In human ECs, the tight junction proteins claudin-5 and zona-occluden-2 (ZO-2) were mislocalized to the cytoplasm after exposure to exogenous Aβ (Marco and Skaper 2006). Similarly, after exposure to exogenous Aβ, human ECs showed decreased expression of occludin levels, although there was no change in claudin-5 and ZO-1 in this study (Tai and others 2010). These results suggest that the tight junctional properties in human BBB is significantly affected by Aβ exposure. In Tg2576 mice, the BBB integrity is compromised as early as four months of age, prior to plaque formation and cognitive impairment (Dickstein and others 2006). Tg2576 mice demonstrated increased BBB leakage and decreased expression of tight junction proteins (claudin-5 and claudin-1), but also increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9, which can degrade the CBM and tight junction proteins and lead to increased BBB permeability as similarly seen in human patient studies. Loss of expression of occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1 was observed in brain microvessels from postmortem CAA patient brain slices (Carrano and others 2011). Another mouse model, TgSwDI, also shows loss of BBB integrity and thus these mice show spontaneous hemorrhages, a major consequence of CAA APP (Davis and others 2004). Understanding how vascular Aβ deposition induces changes in BBB integrity and permeability is critical in developing treatments for CAA.

BBB dysregulation may also be mediated through mural cell responses as well as infiltrated peripheral immune cells. Oligomeric Aβ disturbs the homeostatic regulation of the BBB by disrupting tight junctions and increasing “leakiness” allowing the movement of molecules to enter and exit the brain in a very different way than normal (Yamazaki and Kanekiyo 2017). This also constricts human capillaries in AD via pericyte signaling pathways, suggesting its potential impact in CAA, particularly in CAA-type 1 (Nortley and others 2019). Soluble Aβ40 leads to tight junction redistribution in the BBB and decreased transendothelial electric resistance, causing an inflammatory response that includes monocyte transmigration through ECs, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Hartz and others 2012). The cytokines secreted by these cells can then attract blood-derived immune cells that can infiltrate the brain due to increased permeability of the BBB and can induce expression of MMP-9 (Hartz and others 2012; Zipfel and others 2009). MMP-9 can further degrade the CBM, promoting cerebral hemorrhage and further disrupting the BBB (Hartz and others 2012; Zipfel and others 2009). Moreover, the release of inflammatory mediators following the progressive build-up of Aβ in vessels may trigger a secondary cascade of metabolic events that further compromise BBB integrity (Ghiso and others 2014). These changes can include generation of free radicles and ROS, disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and activation of apoptotic pathways (Ghiso and others 2014). The inflammatory response and cytokine profile may serve as potential biomarkers for CAA, as has been suggested previously (Howe and others 2018b). Based on these studies, vascular deposition of Aβ may result from, or contribute to, BBB dysfunction within the neurovascular unit (Zipfel and others 2009). Understanding the mechanisms that promote BBB integrity may be key in slowing the progression of CAA.

The Inflammatory Response in CAA

The importance of the immune system response in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, has been established for many years. Unfortunately, the inflammatory response associated with CAA has been vastly understudied even though it has been suggested that CAA-affected vessels are affected by inflammation (Wyss-Coray and Rogers 2012). The inflammatory response is triggered by the morphological changes observed in vessels of CAA patients including loss of SMCs, loss of BBB integrity, and thickening of CBM. In addition, the inflammatory response may have a feedback role in promoting altered vessel function and can significantly affect the pathogenesis of CAA. Thus, understanding the role the inflammatory response plays in CAA is crucial to understanding the pathogenesis of CAA.

The immune response typically occurs in two broad categories: innate immunity (nonspecific first line of defense) and adaptive immunity (specific-to-pathogen second line of defense). The innate immune response is most often associated with the Aβ pathology as it appears to drive neuroinflammation. In CAA-affected capillary vessels, clusters of activated microglia and astrocytes have been observed around vascular Aβ deposits (Fig. 6A; Akiyama and others 2000; Carrano and others 2012). Microglia are known to have impaired phagocytosis with aging (Ritzel and others 2015) and this may affect phagocytosis of Aβ. Additionally, upon phagocytosis of Aβ, an inflammatory response occurs leading to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased ROS production (Fig. 6B; Schreibelt and others 2007). In vitro, the increase in ROS leads to loss of endothelial cell-to-cell interactions and loss of BBB integrity through tight junction disruption (Carrano and others 2012; Schreibelt and others 2007). These results are similar to what has been observed previously in AD, where activated glial cells are recruited to Aβ plaques in the brain of an AD mouse model (Meyer-Luehmann and others 2008; Wyss-Coray and others 2003; Wyss-Coray and Rogers 2012). Other innate immune cells that may play a role in CAA are the monocyte/macrophage lineage cells, although the exact mechanism they play is unclear (Yamada 2015). Brain perivascular macrophages are found in the PVS, a major site of brain Aβ trafficking and accumulation (Park and others 2017). A study by Park and colleagues in Tg2576 mice found that brain perivascular macrophages contribute to ROS production, induce oxidative stress, and alter neurovascular function through its receptors, CD36 and Nox2 (Park and others 2017). Much less is known about the adaptive immune response in CAA, as T-cells have only occasionally been observed in vascular deposits with increasing age in the Tg2576 and the APP/PS1 mouse models (Ferretti and others 2016). However, antigen-exposed T cell subsets circulate in the CSF of AD patients, suggesting that T cells may exist at the surface of the brain where CAA-prone leptomeningeal vessels are located (Gate and others 2020). Nonetheless, the immune response in CAA pathogenesis likely plays a critical role in the clinical manifestations of CAA and disease progression.

Figure 6.

Depiction of CAA-laden vessel microenvironment and immunologic response. (A) Aβ deposits surrounded by innate immune cells such as astrocytes, activated microglia, and macrophages. (B) Phagocytosis of Aβ results in increased ROS production and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines expression (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukins, and transforming growth factor beta-1) resulting in altered BBB integrity, leakage, and infiltration.

The inflammatory response induced by Aβ and disruption of the BBB leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Cytokines are a heterogeneous group of polypeptides that are important mediators of inflammation. In AD pathology, expression levels of several cytokines are altered, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukins (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-23), CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL2, CCR2, and transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-β1; Akiyama and others 2000; Wyss-Coray and Rogers 2012). Microvessels isolated from AD patient brains compared to age-matched controls had significantly higher levels of TNFα, TGF-β1, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (Grammas and Ovase 2001). Although the role of these inflammatory cytokines is not clearly defined, they are associated with the development and progression of AD pathology and are now considered a driving force in AD (Ghiso and others 2014). In AD studies, the inflammation-driven mechanisms are centered on the role of microglia cells, while in CAA, the focus of the inflammatory response has centered on both ECs and SMCs in vessels due to their potent inflammatory potential. Treatment of cerebral ECs with exogenous Aβ evoked a pro-inflammatory response with increased expression of IL-1 and IL-6, suggesting a similar mechanism to AD pathology and a role in CAA disease progression (Ghiso and others 2014). Thus, ECs and SMCs can release many of the pro-inflammatory cytokines that are upregulated in AD and these may also play a role in CAA disease progression. Unfortunately, the specific mechanisms of these pro-inflammatory cytokines in CAA-related pathology have not been clearly defined and further studies are needed to delineate the role of inflammation in CAA.

Genetically, the homozygous APOE ε4 genetic mutation is strongly associated with CAARI. Patients who harbor this mutation presented with evidence of CAA-related vasculitis or perivascular inflammation upon pathological examination (Auriel and Greenberg 2012). This is similar to the prognosis of the APOE mutation observed in AD, where patients with this mutation have an increased risk of developing AD with exacerbated inflammation. Another mutation in AD, the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) is strongly linked to regulation of the inflammatory response (Li and Zhang 2018). TREM2 is a receptor on migroglia cells that regulates phagocytosis and a polymorphism observed in AD leads to TREM2 loss-of-function, reducing the capacity of microglial cells to phagocytose and clear Aβ (Li and Zhang 2018). The role of TREM2 in CAA is not clear but likely plays a similar role. Understanding the role of the immune system in CAA pathology will likely lead to increased therapeutic targets that may slow the progression of CAA.

Conclusion

The underlying mechanisms of CAA pathology are unclear and more studies are needed if we hope to develop novel therapeutic approaches. Currently, the main hypothesis surrounding the mechanism of CAA progression is focused on the impaired clearance systems of Aβ peptides, but BBB dysfunction and the role of the immune response on CAA pathogenesis are also important components. The prevalence of CAA will only continue to rise as humans are living longer, but without any disease-modifying therapies or cures for CAA the economic burden of this disease will continue to increase. Thus, understanding the mechanisms underlying CAA development and progression is crucial.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We would like to thank our funding sources: (1) The American Heart Association Postdoctoral Research Fellow, AHA-20POST35180054 (to MGG); (2) The National Institute of Aging, NIH/NIA RF1AG057576 (to AU); and (3) the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke NIH/NINDS NS094543, and NIH/NIA 1RF1AG058463 (to LDM).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Akiyama H, Kondoh T, Kokunai T, Nagashima T, Saito N, Tamaki N. 2000. Blood-brain barrier formation of grafted human umbilical vein endothelial cells in athymic mouse brain. Brain Res 858(1):172–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albargothy NJ, Johnston DA, MacGregor-Sharp M, Weller RO, Verma A, Hawkes CA, and others. 2018. Convective influx/glymphatic system: tracers injected into the CSF enter and leave the brain along separate peri-arterial basement membrane pathways. Acta Neuropathol 136(1):139–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attems J, Quass M, Jellinger KA, Lintner F. 2007. Topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and its effect on cognitive decline are influenced by Alzheimer disease pathology. J Neurol Sci 257(1–2):49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auriel E, Greenberg SM. 2012. The pathophysiology and clinical presentation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Curr Atheroscler Rep 14(4):343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee G, Ambler G, Keshavan A, Paterson RW, Foiani MS, Toombs J, and others. 2020. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Alzheimers Dis 74(4):1189–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S, Bhat MA. 2007. Neuron-glial interactions in blood-brain barrier formation. Annu Rev Neurosci 30:235–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RD, Zlokovic BV. 2009. Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 118(1):103–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste H, Liu X, Koundal S, Sanggaard S, Lee H, Wardlaw J. 2019. The glymphatic system and waste clearance with brain aging: a review. Gerontology 65(2):106–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffi A, Greenberg SM. 2011. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol 7(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannstrom K, Islam T, Gharibyan AL, Iakovleva I, Nilsson L, Lee CC, and others. 2018. The properties of amyloid-beta fibrils are determined by their path of formation. J Mol Biol 430(13):1940–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun ME, Burgermeister P, Phinney AL, Stalder M, Tolnay M, Wiederhold KH, and others. 1999. Neuronal overexpression of mutant amyloid precursor protein results in prominent deposition of cerebrovascular amyloid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(24):14088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrano A, Hoozemans JJ, van der Vies SM, Rozemuller AJ, van Horssen J, de Vries HE. 2011. Amyloid beta induces oxidative stress-mediated blood-brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal 15(5):1167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrano A, Hoozemans JJ, van der Vies SM, van Horssen J, de Vries HE, Rozemuller AJ. 2012. Neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Neurodegener Dis 10(1–4):329–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Gurol ME, Ayata C, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, and others. 2017. Emerging concepts in sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain 140(7):1829–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Haley K, Auriel E, van Etten ES, Fotiadis P, and others. 2016. White matter hyperintensity patterns in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and hypertensive arteriopathy. Neurology 86(6):505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Friedrich JO, Greenberg SM, Viswanathan A. 2018. Core cerebrospinal fluid biomarker profile in cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a meta-analysis. Neurology 90(9):e754–e762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charidimou A, Gang Q, Werring DJ. 2012. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy revisited: recent insights into pathophysiology and clinical spectrum. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 83(2):124–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Xu F, Deane R, Romanov G, Previti ML, Zeigler K, and others. 2004. Early-onset and robust cerebral microvascular accumulation of amyloid beta-protein in transgenic mice expressing low levels of a vasculotropic Dutch/Iowa mutant form of amyloid beta-protein precursor. J Biol Chem 279(19):20296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, and others. 2003. RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med 9(7):907–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deramecourt V, Slade JY, Oakley AE, Perry RH, Ince PG, Maurage CA, and others. 2012. Staging and natural history of cerebrovascular pathology in dementia. Neurology 78(14):1043–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DL, Biron KE, Ujiie M, Pfeifer CG, Jeffries AR, Jefferies WA. 2006. Abeta peptide immunization restores blood-brain barrier integrity in Alzheimer disease. FASEB J 20(3):426–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue JE, Flaherty SL, Johanson CE, Duncan JA 3rd, Silverberg GD, Miller MC, and others. 2006. RAGE, LRP-1, and amyloid-beta protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 112(4):405–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt B, Sorokin L. 2009. The blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: function and dysfunction. Semin Immunopathol 31(4):497–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdo F, Krajcsi P. 2019. Age-related functional and expressional changes in efflux pathways at the blood-brain barrier. Front Aging Neurosci 11:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MA, Banks WA. 2013. Blood-brain barrier dysfunction as a cause and consequence of Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33(10):1500–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti MT, Merlini M, Spani C, Gericke C, Schweizer N, Enzmann G, and others. 2016. T-cell brain infiltration and immature antigen-presenting cells in transgenic models of Alzheimer’s disease-like cerebral amyloidosis. Brain Behav Immun 54:211–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foidl BM, Humpel C. 2019. Chronic treatment with five vascular risk factors causes cerebral amyloid angiopathy but no Alzheimer pathology in C57BL6 mice. Brain Behav Immun 78:52–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frackowiak J, Zoltowska A, Wisniewski HM. 1994. Nonfibrillar beta-amyloid protein is associated with smooth muscle cells of vessel walls in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 53(6):637–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gate D, Saligrama N, Leventhal O, Yang AC, Unger MS, Middeldorp J, and others. 2020. Clonally expanded CD8 T cells patrol the cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 577(7790):399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiso J, Fossati S, Rostagno A. 2014. Amyloidosis associated with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: cell signaling pathways elicited in cerebral endothelial cells. J Alzheimers Dis 42 Suppl 3:S167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammas P, Ovase R. 2001. Inflammatory factors are elevated in brain microvessels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 22(6):837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Pruzin J, Sperling R, van Veluw SJ. 2020. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer disease—one peptide, two pathways. Nat Rev Neurol 16(1):30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SM, Charidimou A. 2018. Diagnosis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: evolution of the Boston criteria. Stroke 49(2):491–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene GM, Godersky JC, Biller J, Hart MN, Adams HP Jr. 1990. Surgical experience with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke 21(11):1545–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm MO, Mett J, Stahlmann CP, Haupenthal VJ, Zimmer VC, Hartmann T. 2013. Neprilysin and abeta clearance: impact of the APP intracellular domain in NEP regulation and implications in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 5:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurol ME, Greenberg SM. 2013. A physiologic biomarker for cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 81(19):1650–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannocks MJ, Pizzo ME, Huppert J, Deshpande T, Abbott NJ, Thorne RG, and others. 2018. Molecular characterization of perivascular drainage pathways in the murine brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 38(4):669–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. 2002. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297(5580):353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA. 1992. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256(5054):184–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, Bauer B, Soldner EL, Wolf A, Boy S, Backhaus R, and others. 2012. Amyloid-beta contributes to blood-brain barrier leakage in transgenic human amyloid precursor protein mice and in humans with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Stroke 43(2):514–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, Miller DS, Bauer B. 2010. Restoring blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein reduces brain amyloid-beta in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Pharmacol 77(5):715–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AM, Zhong Y, Wolf A, LeVine H 3rd, Miller DS, Bauer B. 2016. Abeta40 reduces P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Neurosci 36(6):1930–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz AMS, Zhong Y, Shen AN, Abner EL, Bauer B. 2018. Preventing P-gp ubiquitination lowers abeta brain levels in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Front Aging Neurosci 10:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes CA, Gatherer M, Sharp MM, Dorr A, Yuen HM, Kalaria R, and others. 2013. Regional differences in the morphological and functional effects of aging on cerebral basement membranes and perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the mouse brain. Aging Cell 12(2):224–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes CA, Sullivan PM, Hands S, Weller RO, Nicoll JA, Carare RO. 2012. Disruption of arterial perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the brains of mice expressing the human APOE epsilon4 allele. PLoS One 7(7):e41636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming ML, Selkoe DJ. 2005. Amyloid beta-protein is degraded by cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and elevated by an ACE inhibitor. J Biol Chem 280(45):37644–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hladky SB, Barrand MA. 2018. Elimination of substances from the brain parenchyma: efflux via perivascular pathways and via the blood-brain barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS 15(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe MD, Atadja LA, Furr JW, Maniskas ME, Zhu L, McCullough LD, and others. 2018a. Fibronectin induces the perivascular deposition of cerebrospinal fluid-derived amyloid-beta in aging and after stroke. Neurobiol Aging 72:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe MD, Zhu L, Sansing LH, Gonzales NR, McCullough LD, Edwards NJ. 2018b. Serum markers of blood-brain barrier remodeling and fibrosis as predictors of etiology and clinicoradiologic outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol 9:746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, and others. 1996. Correlative memory deficits, Abeta elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274(5284):99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, and others. 2012. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med 4(147):147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Zeppenfeld DM, Venkataraman A, Plog BA, Liao Y, and others. 2013. Cerebral arterial pulsation drives paravascular CSF-interstitial fluid exchange in the murine brain. J Neurosci 33(46):18190–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen NA, Munk AS, Lundgaard I, Nedergaard M. 2015. The glymphatic system: a beginner’s guide. Neurochem Res 40(12):2583–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Wang N, Zhang Y, Xue D, Lou H, Liu X. 2020. Alteration in the function and expression of SLC and ABC transporters in the neurovascular unit in Alzheimer’s disease and the clinical significance. Aging Dis 11(2):390–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshner HS, Bradshaw M. 2015. The inflammatory form of cerebral amyloid angiopathy or “cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation” (CAARI). Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 15(8):54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei HS, Zeppenfeld D, and others. 2014. Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol 76(6):845–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JT, Zhang Y. 2018. TREM2 regulates innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 15(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochhead JJ, Wolak DJ, Pizzo ME, Thorne RG. 2015. Rapid transport within cerebral perivascular spaces underlies widespread tracer distribution in the brain after intranasal administration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35(3):371–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Ries M, Decker Y, Muller A, Riner C, Bucker A, and others. 2019. Rapid lymphatic efflux limits cerebrospinal fluid flow to the brain. Acta Neuropathol 137(1):151–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mader S, Brimberg L. 2019. Aquaporin-4 water channel in the brain and its implication for health and disease. Cells 8(2):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaki S, Tang Z, Tung S, Williams CK, Lo D, Yong WH, and others. 2018. The effects of cerebral amyloid angiopathy on integrity of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Aging 70:70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco S, Skaper SD. 2006. Amyloid beta-peptide1–42 alters tight junction protein distribution and expression in brain microvessel endothelial cells. Neurosci Lett 401(3):219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega KG et al. 2010. Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science 330: 1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan E, Pickford F, Kim J, Onstead L, Eriksen J, Yu C, and others. 2005. Abeta42 is essential for parenchymal and vascular amyloid deposition in mice. Neuron 47(2):191–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Luehmann M, Spires-Jones TL, Prada C, Garcia-Alloza M, de Calignon A, Rozkalne A, and others. 2008. Rapid appearance and local toxicity of amyloid-beta plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 451(7179):720–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli L, Llovera RE, Mathov I, Lue LF, Frangione B, Ghiso J, and others. 2004. Insulin-degrading enzyme in brain microvessels: proteolysis of amyloid {beta} vasculotropic variants and reduced activity in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Biol Chem 279(53):56004–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AW, Carare RO, Schreiber S, Hawkes CA. 2014. The cerebrovascular basement membrane: role in the clearance of beta-amyloid and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Front Aging Neurosci 6:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nortley R, Korte N, Izquierdo P, Hirunpattarasilp C, Mishra A, Jaunmuktane Z, and others. 2019. Amyloid beta oligomers constrict human capillaries in Alzheimer’s disease via signaling to pericytes. Science 365(6450):eaav9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park L, Uekawa K, Garcia-Bonilla L, Koizumi K, Murphy M, Pistik R, and others. 2017. Brain perivascular macrophages initiate the neurovascular dysfunction of Alzheimer Abeta peptides. Circ Res 121(3):258–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascale CL, Miller MC, Chiu C, Boylan M, Caralopoulos IN, Gonzalez L, and others. 2011. Amyloid-beta transporter expression at the blood-CSF barrier is age-dependent. Fluids Barriers CNS 8:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira CD, Martins F, Wiltfang J, da Cruz ESOAB, Rebelo S. 2018. ABC transporters are key players in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 61(2):463–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo ME, Wolak DJ, Kumar NN, Brunette E, Brunnquell CL, Hannocks MJ, and others. 2018. Intrathecal antibody distribution in the rat brain: surface diffusion, perivascular transport and osmotic enhancement of delivery. J Physiol 596(3):445–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensink AA, de Waal RM, Kremer B, Verbeek MM. 2003. Pathogenesis of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 43(2):207–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revesz T, Ghiso J, Lashley T, Plant G, Rostagno A, Frangione B, and others. 2003. Cerebral amyloid angiopathies: a pathologic, biochemical, and genetic view. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62(9):885–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzel RM, Patel AR, Pan S, Crapser J, Hammond M, Jellison E, and others. 2015. Age- and location-related changes in microglial function. Neurobiol Aging 36(6):2153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo C, Angelini G, Dapino D, Piccini A, Piombo G, Schettini G, and others. 1998. Opposite roles of apolipoprotein E in normal brains and in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95(26):15598–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreibelt G, Kooij G, Reijerkerk A, van Doorn R, Gringhuis SI, van der Pol S, and others. 2007. Reactive oxygen species alter brain endothelial tight junction dynamics via RhoA, PI3 kinase, and PKB signaling. FASEB J 21(13):3666–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. 1994. Cell biology of the amyloid beta-protein precursor and the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Annu Rev Cell Biol 10:373–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Yamada S, Kumar SR, Calero M, Bading J, Frangione B, and others. 2000. Clearance of Alzheimer’s amyloid-ss(1–40) peptide from brain by LDL receptor-related protein-1 at the blood-brain barrier. J Clin Invest 106(12):1489–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg GD, Messier AA, Miller MC, Machan JT, Majmudar SS, Stopa EG, and others. 2010. Amyloid efflux transporter expression at the blood-brain barrier declines in normal aging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69(10):1034–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Duan T, Verkman AS. 2019. Aquaporin-4 reduces neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by remodeling peri-plaque astrocyte structure. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Gurol ME, Eng JA, Engel CR, Nguyen TN, Rosand J, and others. 2004. White matter lesions, cognition, and recurrent hemorrhage in lobar intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 63(9):1606–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EE, Vijayappa M, Lima F, Delgado P, Wendell L, Rosand J, and others. 2008. Impaired visual evoked flow velocity response in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology 71(18):1424–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturchler-Pierrat C, Abramowski D, Duke M, Wiederhold KH, Mistl C, Rothacher S, and others. 1997. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94(24):13287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppiah S, Didier MA, Vinjamuri S. 2019. The who, when, why, and how of PET amyloid imaging in management of Alzheimer’s disease—review of literature and interesting images. Diagnostics (Basel) 9(2):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai LM, Holloway KA, Male DK, Loughlin AJ, Romero IA. 2010. Amyloid-beta-induced occludin down-regulation and increased permeability in human brain endothelial cells is mediated by MAPK activation. J Cell Mol Med 14(5):1101–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, and others. 2015. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 11(8):457–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Yamaguchi H, Del Tredici K, Braak H. 2002. Two types of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 61(3):282–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal DR, Grinberg LT, Attems J. 2012. Vascular dementia: different forms of vessel disorders contribute to the development of dementia in the elderly brain. Exp Gerontol 47(11):816–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen MS, Birkelund S, Burkhart A, Stensballe A, Moos T. 2017. Synthesis and deposition of basement membrane proteins by primary brain capillary endothelial cells in a murine model of the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem 140(5):741–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]