Abstract

Anopheles mating is initiated by the swarming of males at dusk followed by females flying into the swarm. Here, we show that mosquito swarming and mating are coordinately guided by clock genes, light, and temperature. Transcriptome analysis shows up-regulation of the clock genes period (per) and timeless (tim) in the head of field-caught swarming Anopheles coluzzii males. Knockdown of per and tim expression affects Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles stephensi male mating in the laboratory, and it reduces male An. coluzzii swarming and mating under semifield conditions. Light and temperature affect mosquito mating, possibly by modulating per and/or tim expression. Moreover, the desaturase gene desat1 is up-regulated and rhythmically expressed in the heads of swarming males and regulates the production of cuticular hydrocarbons, including heptacosane, which stimulates mating activity.

The malaria parasite, transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes, infects more than 200 million people and causes nearly half a million deaths annually (1). In the absence of an effective vaccine, mosquito control using insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying remains the most effective means of combating the disease (2). However, mosquito control is being affected by resistance to commonly used insecticides (3, 4). Thus, there is an urgent need to develop alternative tools to control mosquito populations (5). Male mating behavior is a key aspect of the mosquito life cycle, and targeting this behavior has shown promise for vector control (6).

Males of numerous dipteran species, including many anopheline and culicine mosquitoes, form flight swarms that contain tens to thousands of males as a prerequisite for mating (7–13). Females fly into the swarm, where they select a male for copulation (14). After insemination, the female is generally not receptive to copulation for the remainder of the female’s life (15).

Day-night cycle, light intensity, and temperature regulate the circadian rhythmicity of behavior and physiology of most organisms (16–18). For example, Anopheles mosquitoes swarm and mate daily at dusk (8). However, the molecular mechanisms that modulate mosquito swarming and mating behavior have yet to be clarified. Understanding mating biology is necessary to guide the development and implementation of vector control programs by means of the release of either conventional sterile or genetically engineered males (19). In this work, we undertook experiments in the laboratory and in near-field conditions to identify components of the circadian clock apparatus that regulate male swarming and mating behavior in Anopheles mosquitoes.

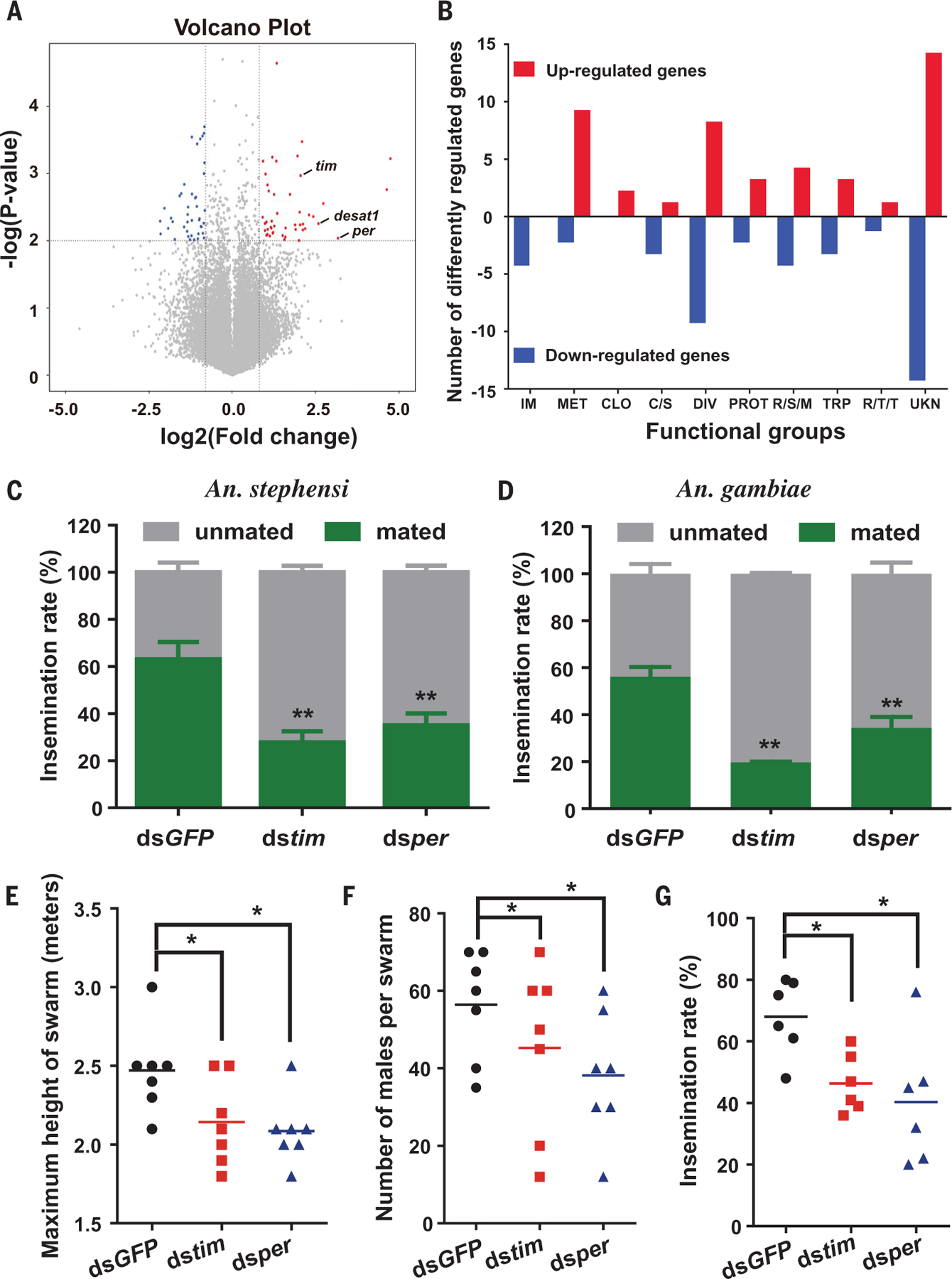

To identify genes involved in swarming and mating behaviors, we collected Anopheles coluzzii males at dusk from swarms and from houses (resting, nonswarming) in Vallée du Kou, Burkina Faso, and isolated RNA from their heads. Anopheles gambiae s.s. genome microarray analysis showed that 87 genes significantly differed (≥1.75-fold change, Student’s t test, P < 0.01) between the two groups, including 45 up-regulated and 42 down-regulated genes in the heads of swarming versus nonswarming males (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). Notably, up-regulated genes in swarming males were overrepresented in the functional categories of circadian clock and metabolism, including two canonical clock genes— period (per) (AGAP001856) and timeless (tim) (AGAP006376)—and nine genes involved in carbohydrate, amino acid, or lipid metabolism (Fig. 1B). By contrast, all four differentially expressed genes (DEGs) encoding immunity were down-regulated in swarming male heads compared with nonswarming male heads (Fig. 1B). We used quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to validate DEGs associated with circadian clock and metabolism. Most genes tested had the expected directional changes (table S1). Collectively, global transcription analysis indicates that circadian clock and metabolism genes are associated with male swarming behavior.

Fig. 1. Mosquito swarming and mating are regulated by the clock genes per and tim.

(A and B) Transcriptome analysis of An. coluzzii head gene expression between swarming and non-swarming male mosquitoes. (A) Volcano plot of DEGs. Significantly up-regulated and down-regulated genes are marked with red and blue spots, respectively. (B) DEGs by gene ontology category in swarming male heads compared with non-swarming males. Differential gene expression was considered significant when the expression fold change (swarming versus nonswarming) was ≥0.75 on a log2 scale (P < 0.01). IM, immunity; MET, metabolism; CLO, clock; C/S, cytoskeletal and structural; DIV, diverse; PROT, proteolysis; R/S/M, oxidoreductive, stress-related, and mitochondrial; TRP, transport; R/T/T, replication, transcription, and translation; UKN, unknown function. (C and D) Silencing of tim and per in virgin An. stephensi (C) or An. gambiae s.s. (D) males causes a reduction in the rate of female insemination, as determined by light microscopy examination for the presence of sperm in the dissected female spermatheca (fig. S3). A total of 60 virgin males were injected with double-stranded RNA for each treatment. Error bars indicate SEMs. Similar results were obtained from two biological repeats. (E to G) Knockdown of tim or per in virgin An. coluzzii males affects the swarm maximum height (E), swarm size (number of swarming males per swarm) (F), and mating frequency (G) under semifield conditions (Burkina Faso). Each symbol denotes the result of an independent experiment (n = 7). Horizontal lines represent the means. Statistics were performed with Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

To address the hypothesis that clock genes influence male swarming and mating activity, we silenced per and tim in Anopheles stephensi virgin males by systemic injection of double-stranded RNA (dsper or dstim) (fig. S2). Injected males were allowed to mate with virgin females, and the presence of sperm in the female spermatheca was used as a mating indicator (fig. S3). Although swarming is not a common behavior in laboratory small cages, male Anopheles mosquitoes still exhibit swarm-like mating flight activity (14, 20). We confirmed that Anopheles males display evening peak flight activity in laboratory cages and that knockdown of per or tim gene expression in An. stephensi males significantly reduces flying activity (fig. S4). Silencing of per or tim significantly affected male mating flight activity around Zeitgeber time (ZT) ZT13 to ZT15, when peak mating activity of double-stranded green fluorescent protein gene (dsGFP)–treated mosquitoes (control) occurs in small cages (fig. S4 and movies S1 and S2). Reduction in flight activity correlated with significant reduction of mating (female insemination rate) (Fig. 1, C and D). These results suggest that the two core clock genes per and tim regulate mating activity in Anopheles mosquitoes.

To determine the role of per and tim in mosquito swarming and mating activity in a semifield setting, we performed experiments in a large outdoor mosquito sphere in the Vallée du Kou in Burkina Faso. Locally captured and reared An. coluzzii virgin male mosquitoes were injected with double-stranded RNA encoding per, tim, or GFP as control. Three days later, the injected males and virgin females were released before sunset in compartments with a swarming marker (1-m2 black cloth) (21), and swarming behavior was monitored for 1 hour. We observed a significant reduction in swarm maximum height and swarm size (number of swarming males) in male mosquitoes injected with dsper or dstim (Fig. 1, E and F). Moreover, mating was significantly reduced in males injected with dsper (40% insemination) or dstim (47% insemination) compared with male mosquitoes injected with dsGFP (70% insemination) (Fig. 1G). These reductions are consistent with those observed in a laboratory setting (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results indicate that the circadian genes per and tim regulate male Anopheles swarming and mating activity.

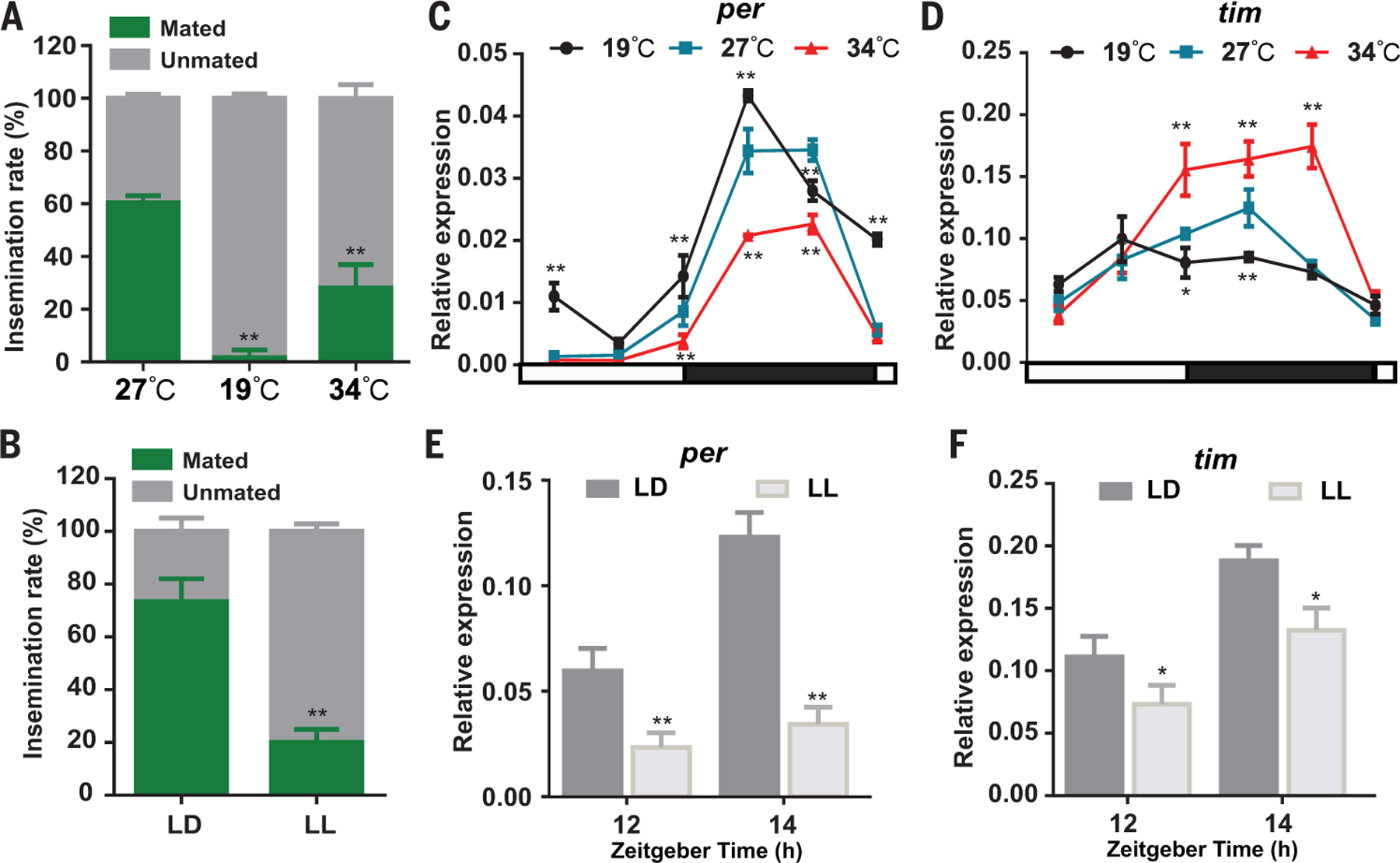

The circadian clock is intimately regulated by temperature and light fluctuations (22). To investigate the effect of temperature on mosquito mating, 3-day-old virgin male and female An. stephensi mosquitoes were pooled and kept overnight at 27°, 19°, or 34°C. We found that low temperature (19°C) and high temperature (34°C) significantly inhibited mosquito mating activity compared with the optimum temperature of 27°C (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Temperature and light affect mating activity.

Newly emerged male and female mosquitoes were kept separately for 3 days at 27°C under 12-hour–12-hour LD cycling before performing the experiment. (A) Temperature affects mosquito mating activity. Males and females were pooled; kept overnight at 19°, 27°, or 34°C; and female insemination rates were determined. (B) Light inhibits mosquito mating activity. Males and females were pooled, kept in LD or LL conditions, and female insemination rates were determined. (C and D) Effect of temperature on per (C) and tim (D) transcript abundance in male An. stephensi heads under LD cycling. Mosquitoes were kept under LD cycles at 19°, 27°, or 34°C. per and tim transcript rhythm in male heads was measured by qRT-PCR. The housekeeping gene RPS7 (AsS7) was used as an internal reference in qRT-PCR assays. (E and F) Effect of prolonged light on per (E) and tim (F) transcript abundance in male An. stephensi heads. Male mosquitoes were maintained for 3 days at 27°C under LD cycling and then either kept in the LD condition or switched to the LL condition. Mosquitoes were collected at ZT12 (lights off) and ZT14 (2 hours after lights off) for detection of per and tim expression levels. Error bars indicate SEMs. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). Similar results were obtained from two biological repeats.

We next examined whether light influences mosquito mating activity by comparing mating frequencies of mosquitoes that were maintained either in light-dark (LD) conditions (lights off at night) or light-light (LL) conditions (lights on at night). The mating frequency of mosquitoes in the LL condition was significantly lower than that of mosquitoes in the LD condition (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that adverse temperatures and continuous light strongly affect mosquito mating. Moreover, the rhythm of per and tim transcripts in An. stephensi male heads is strongly affected by changes in ambient temperature. Peak levels of per mRNA were higher at 19°C and lower at 34°C compared with those at 27°C (Fig. 2C). Contrastingly, the highest levels of tim expression were observed at 34°C with successive reduction at lower temperatures (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the transcription abundance of per and tim in male heads was significantly lower under the continuous-light condition (Fig. 2, E and F), which indicates that prolonged exposure to LL conditions reduces the expression of per and tim in the evening.

Of 86 DEGs, one unknown gene (AGAP002588) and a cuticular protein gene CPR30 (AGAP006009) were among the most up-regulated genes (~25-fold) in the heads of swarming males compared with nonswarming males (table S1). Additionally, an ortholog to the Drosophila desaturase 1 (desat1) gene required for pheromone production (desat1, AGAP001713) and a P450 gene CYP325G1 (AGAP002196) were also highly up-regulated in swarming male heads (table S1). The expression of desat1, the AGAP002588 gene homolog, and CPR30—but not CYP325G1—exhibited robust, high-amplitude rhythm in synchrony with the two canonical clock genes per and tim (fig. S5). The expression patterns of these DEGs in different mosquito tissues is presented in fig. S6.

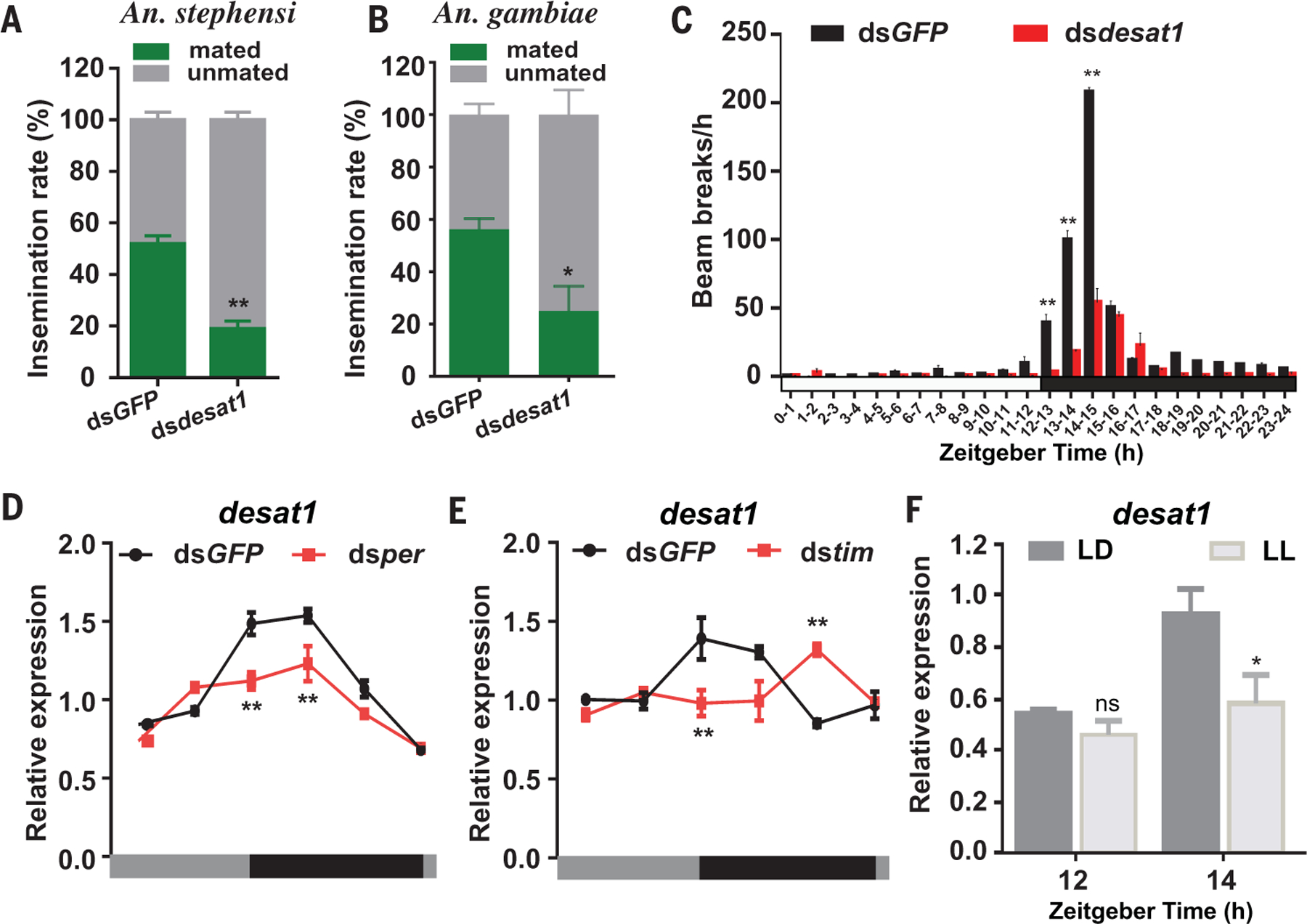

We next determined whether these genes play any role in mosquito mating. Knockdown of desat1 expression in An. stephensi and An. gambiae s.s. virgin males significantly reduced female insemination rates (Fig. 3, A and B) and markedly reduced male mating flight activity (Fig. 3C and movie S3), whereas silencing of the AGAP002588 gene homolog, CPR30, and CYP325G1 did not affect female insemination rate (fig. S7). Moreover, we found that knockdown of per or tim significantly altered the amplitude or rhythm of desat1 expression in An. stephensi male heads under a dark-dark (DD) (constant dark) condition (Fig. 3, C and D), which indicates that desat1 is a clock-controlled gene.

Fig. 3. Desat1 regulates male flight activity and mating.

(A and B) Silencing desat1 expression in An. stephensi (A) and An. gambiae s.s. (B) virgin males causes reduction of female insemination. (C) Flight activity of An. stephensi virgin male mosquitoes injected with dsGFP (black) or dsdesat1(red) and maintained under 12-hour–12-hour LD cycles. Values show the total activity within each hourly time bin (mean ± SEM) of 16 mosquitoes in one treatment. The white and black bar below the graph denotes when lights were on and off, respectively. Lights on occurred at ZT0 and lights off occurred at ZT12. (D and E) Silencing per (D) or tim (E) influences the expression pattern of destal1 in An. stephensi male heads maintained under DD (constant dark) condition. The housekeeping gene RPS7 (AsS7) was used as the internal control for qRT-PCR. Data were normalized to median fold change. Circadian day and night are indicated by the horizontal gray and black (indicating subjective day and subjective night, respectively) bars below the charts. (F) Effect of prolonged light on desat1 transcript abundance in male An. stephensi heads. After being maintained at 27°C under LD cycling for 3 days, male mosquitoes were either kept in the LD condition or switched to the LL condition. Mosquitoes were collected at ZT12 (lights off) and ZT14 (2 hours after lights off) for detection of desat1 expression levels. Error bars indicate SEMs. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (Student’s t test). Similar results were obtained from three experimental repeats.

We next investigated whether temperature and light affect the expression of desat1. We found that desat1 transcript rhythm in the An. stephensi male heads is not affected by changes in ambient temperature (fig. S8), but under prolonged light exposure, desat1 transcript abundance decreases significantly (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that light exposure in the evening inhibits desat1 expression, which may be related to the inhibition of mosquito mating by light (Fig. 2B).

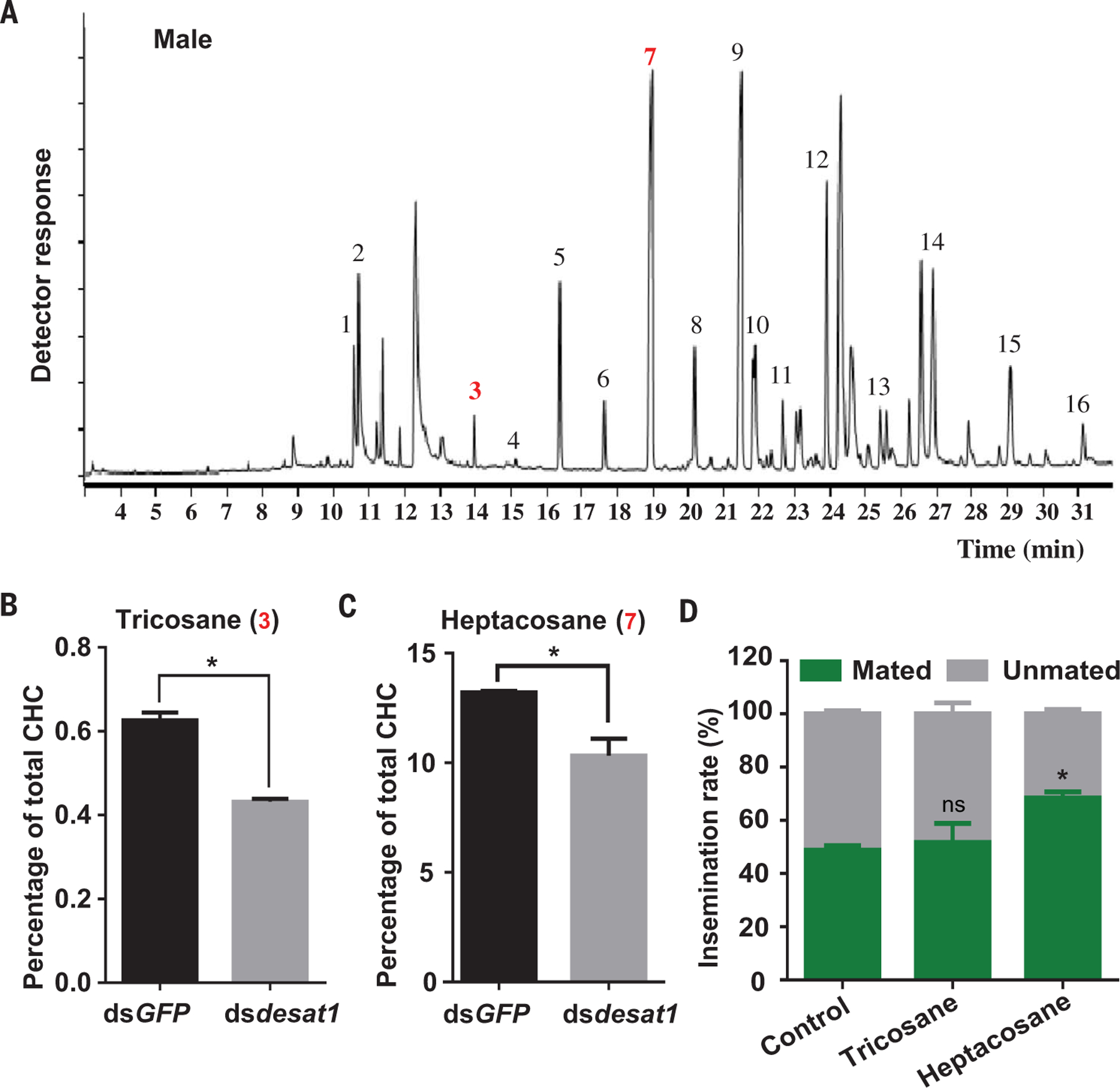

Many dipterans use cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) as sex pheromones for species and sex recognition and courtship (23–25), but little is known about the possible role of CHCs in mosquito mating and chemical communication. In Drosophila, desat1 regulates the biosynthesis of CHCs (26), several of which function as sex pheromones (27). To examine whether desat1 regulates the biosynthesis of Anopheles CHCs, we determined the hydrocarbon profile by gas chromatography of cuticular extracts of virgin male An. stephensi whole body. Sixteen major CHCs were identified (Fig. 4A and table S2). Silencing of desat1 resulted in significant reduction of tricosane and heptacosane representation (Fig. 4, B and C), which indicates that desat1, a circadian regulated gene, is involved in the production of Anopheles CHCs. We next examined the role of tricosane and heptacosane in Anopheles mating activity and found that perfuming Anopheles males with tricosane did not alter mating activity, whereas perfuming males with heptacosane lead to a significant increase in the rate of female insemination (Fig. 4D and fig. S9). These results suggest that heptacosane enhances the interaction between males and courting females.

Fig. 4. Silencing of desat1 changes the CHC profile of male mosquitoes.

(A) Representative CHC profile of virgin male An. stephensi mosquitoes. Numbers above the peaks correspond to peak numbers given in table S2. (B and C) Comparison of CHCs between mosquitoes injected with dsGFP and dsdesat1. Silencing of desat1 resulted in a significant reduction of the relative percentage of tricosane (peak 3) (B) and heptacosane (peak 7) (C). (D) Effect of the CHCs tricosane and heptacosane on mosquito mating activity. Perfuming Anopheles virgin males with tricosane did not alter mating activity, whereas perfuming males with heptacosane significantly increased female insemination. Error bars indicate SEMs. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

Understanding mosquito mating biology is central to any successful genetic-control strategies. Our transcriptome analysis showed enrichment of up-regulated metabolism and circadian clock genes and down-regulated immune genes in swarming mosquitoes, as swarming is an energy-consuming process accompanied by increased metabolic activity that occurs at dusk.

The circadian clock is cell-autonomous and consists of a series of interlocking transcriptional feedback loops requiring per and tim. Our work shows that these core clock genes are markedly up-regulated in swarming male mosquitoes compared with nonswarming males, and knocking down their expression affects male swarming (lowering swarm height and size) and mating in the laboratory and in semifield conditions.

Light has been shown to influence mosquito blood feeding, gene expression, fecundity, and reproductive barrier (14, 28–33). Our study shows that adverse temperature (lower or higher) and increased light exposure during dark periods inhibit mating activity and influence the expression of per and tim, which indicates that the two factors interact to regulate the timing of male swarming. In Drosophila, temperature regulates the levels and activity of PER and TIM by modulating the genes’ splicing patterns (34, 35). Similarly, our study shows that the per and tim transcript levels in mosquitoes are affected by ambient temperatures. Therefore, light and temperature together entrain the circadian clock, influencing the programming of mosquito swarming and mating (fig. S10).

In many dipteran species, sex pheromones—together with visual, tactile, and acoustic cues—play important roles in courtship behavior preceding mating (36–38). CHCs act as sex pheromones in mate recognition and chemical communication for many insect genera (23, 27). In Drosophila, these CHC pheromones are synthesized by desat1 in secretory cells called oenocytes in the abdominal epidermis, and they are then deposited on the cuticle (23, 26). No Anopheles pheromone has been identified (39). Notably, we found in mating bioassays that perfuming virgin males with the C27 linear heptacosane promotes mosquito mating activity. Heptacosane is known to be a contact sex pheromone that facilitates mating activity of the tea weevil Myllocerinus aurolineatus (40). We found that desat1 is a clock-controlled gene in mosquitoes and that light inhibits its transcription in the evening, reducing the production of CHCs and mating activity. A previous study has shown that the abundance of CHCs, including heptacosane (nC27), in male Drosophila varies in response to light and time of day (41), which indicates that male CHC profiles are a dynamic trait.

This work provides mechanistic insights on the molecular, chemical, and environmental factors regulating Anopheles swarming and mating behaviors. It contributes to a better understanding of mating mechanisms, which might lead to vector control strategies that target insect reproductive behavior.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Zhan and Y. Lai for heatmap analysis, W. Hu for gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis, and H. Liu and Y. Zhang for discussions. We thank N. C. Manoukis for comments on the manuscript.

Funding:

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 32021001, 31830086, and 31772534), the National Key R&D Program of China (grants 2020YFC1200100, 2018YFA0900502, 2017YFD0200400, and 2017YFD0201202), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant XDB11010500), NIH grant R01AI031478, the NIH Distinguished Scholars Program and the Division of Intramural Research AI001250-01, NIAID, and the Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data and code to understand and assess the conclusions of this research are available in the main text, supplementary materials, and via the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession no. GSE150971.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

science.sciencemag.org/content/371/6527/411/suppl/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO), World malaria report 2018 (2018); www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2018/report/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanda E, Ameneshewa B, Bagayoko M, Govere JM, Macdonald MB, Trends Parasitol 33, 30–41 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ranson H, Lissenden N, Trends Parasitol 32, 187–196 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison G, Mosquitos, Malaria, and Man: A History of the Hostilities Since 1880 (Dutton, 1978)

- 5.Cui C et al. , Nat. Commun 10, 4298 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diabate A, Tripet F, Parasit. Vectors 8, 347 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diabaté A et al. , BMC Evol. Biol 11, 184 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawadogo PS et al. , Acta Trop 132, S42–S52 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butail S et al. , J. R. Soc. Interface 9, 2624–2638 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downes JA, Annu. Rev. Entomol 14, 271–298 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaindoa EW et al. , Wellcome Open Res 2, 88 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manoukis NC et al. , J. Med. Entomol 46, 227–235 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assogba BS et al. , Acta Trop 132, S53–S63 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlwood JD, Jones MDR, Physiol. Entomol 5, 315–320 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabrieli P et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 111, 16353–16358 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurley JM, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Trends Biochem. Sci 41, 834–846 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Emery P, in Insect Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Gilbert L, Ed. (Academic Press, 2012), pp. 513–551. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakai T, Ishida N, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 98, 9221–9225 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knols BGJ, Bossin HC, Mukabana WR, Robinson AS, Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 77, 232–242 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facchinelli L et al. , Malar. J 14, 271 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niang A et al. , Parasit. Vectors 12, 446 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamba P, Bilodeau-Wentworth D, Emery P, Zhang Y, Cell Rep 7, 601–608 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wicker-Thomas C, Guenachi I, Keita YF, BMC Biochem 10, 21 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polerstock AR, Eigenbrode SD, Klowden MJ, J. Med. Entomol 39, 545–552 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blomquist GJ, Tillman-Wall JA, Guo L, Quilici DR, Gu P, Schal C, in Insect Lipids: Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology, Stanley-Samuelson DW, Nelson DR, Eds. (Univ. Nebraska Press, 1993), pp. 317–351. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bousquet F et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 249–254 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anholt RRH, O’Grady P, Wolfner MF, Harbison ST, Genetics 214, 49–73 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das S, Dimopoulos G, BMC Physiol 8, 23 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheppard AD et al. , Parasit. Vectors 10, 255 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honnen AC, Kypke JL, Holker F, Monaghan MT, Sustainability 11, 6220 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rund SS, Gentile JE, Duffield GE, BMC Genomics 14, 218 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawadogo SP et al. , Parasit. Vectors 6, 275 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rund SS, Lee SJ, Bush BR, Duffield GE, J. Insect Physiol 58, 1609–1619 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin Anduaga A et al. , eLife 8, e44642 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Majercak J, Sidote D, Hardin PE, Edery I, Neuron 24, 219–230 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wicker-Thomas C, J. Insect Physiol 53, 1089–1100 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cator LJ, Arthur BJ, Harrington LC, Hoy RR, Science 323, 1077–1079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Su MP, Andrés M, Boyd-Gibbins N, Somers J, Albert JT, Nat. Commun 9, 3911 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gendrin M, Cell Host Microbe 22, 577–579 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun X et al. , J. Chem. Ecol 43, 557–562 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kent C, Azanchi R, Smith B, Chu A, Levine J, PLOS ONE 2, e962 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.