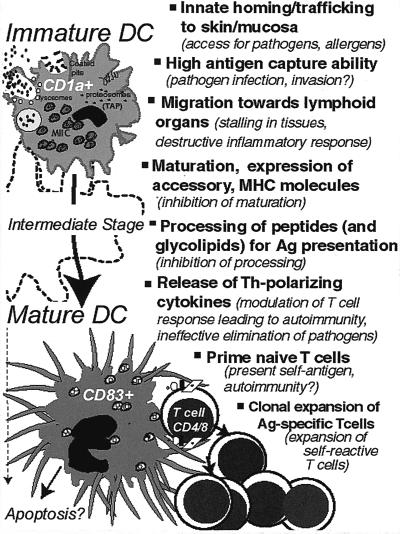

Dendritic cells (DCs) consist of a family of antigen-presenting cells (APC) that patrol all tissues of the body with the possible exceptions of the brain and testes. DCs function to capture bacteria and other pathogens for processing and presentation to T cells in the secondary lymphoid organs (2, 3). They serve as an essential link between innate and adaptive immune systems and induce both primary and secondary immune responses (59). DCs possess the unique ability to prime naive helper and cytotoxic T cells; thus, much interest has been fostered in their possible use in immune response modulation of infectious diseases, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. A number of excellent recent reviews present a comprehensive overview of DCs and their subset diversity (2, 3, 37, 59). Here, we focus on the interaction of DCs with bacteria and other pathogens. We emphasize the key features that distinguish DCs as “immune saviors,” starting with a brief mention of the in vitro systems for studying DC biology and techniques for DC expansion in vivo. We discuss the mechanisms that enable DCs to arrive at the skin and mucosa, to internalize bacteria and other antigens (Ag), to migrate to the T-cell-rich region of lymphoid organs, to process and present bacterial Ag to T cells, and to modulate the adaptive immune response (Fig. 1). This evidence is countered, where noted, with the “Achilles' heel” premise that many of these same activities represent a weakness, subject to exploitation by bacterial pathogens. Finally, we develop a conceptual overlap between infectious diseases and cancers, emphasizing how knowledge of the interactions of DCs with bacteria may lead to advancement of cancer therapy.

FIG. 1.

Positive and negative aspects of DC function.

HUMAN DC SUBSETS, TECHNOLOGY FOR DC CULTURE, EXPANSION, AND ISOLATION

The study of DCs has long been hampered by their rarity in vivo and by the lack of a cell marker expressed by all members of the DC family (3, 59). In humans, DCs comprise three distinct subsets: two in the myeloid lineage, Langerhans cells (LCs) and interstitial DCs (also known as dermal DCs), and the third being lymphoid DCs. LCs, identified by expression of CD1a, Lag (46), and langerin (92), are localized in the basal and suprabasal layers of the epidermis (47). Interstitial DCs are identified by expression of CD14, CD68, and factor XIIIa and are present in the dermis and most organs, including the lungs and heart (42, 57). Lymphoid DCs are CD4+, CD11c−, CD13− CD33−, and CD123+ and are present in blood and lymphoid organs (34).

The development of in vitro DC culture systems has enabled researchers to generate large numbers of highly pure DCs. They have been cultured from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors present in the bone marrow or peripheral blood (7, 8) and also from three blood precursors differentiated from CD34+ progenitors: CD14+ monocytes (77), CD11c+ precursors, and CD11c− precursors (28, 89). The ability of cytokines such as Flt3 ligand (52, 66), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (19, 68), and G-CSF (1, 65) to expand DC subpopulations in vivo has also been an important development in this regard.

CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors cultured in the presence of GM-CSF and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) differentiate along two independent pathways: CD1a+ derived DCs, related to LCs, and CD14+-derived DCs, closely related to interstitial DCs and/or peripheral blood DCs (7, 8). Whereas both DC subpopulations are equally potent in stimulating naive T-cell proliferation, CD14+-derived DCs are 10-fold-more efficient in Ag uptake and have the unique capacity to induce naive B cells to differentiate into immunoglobulin M-secreting cells. Immature monocyte-derived DCs display high levels of endocytic activity compared to that of immature CD11c− DCs. Maturation of DCs in these culture systems is achieved by inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and/or the T-cell analogue CD40 ligand (CD40L), as well as bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Other microbial products such as bacterial DNA and double-stranded RNA can also induce maturation (45, 73, 77, 94). During maturation DCs undergo major changes in phenotype and function. There is a loss of endocytic and phagocytic receptors, whereas there are high levels of surface expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II), upregulation of costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) required for T-cell stimulation, and expression of CD83, a unique marker of matured DCs (3, 101). Several other molecules are also upregulated, including CD40 and adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and LFA-3. In contrast, Fc receptor expression involved in endocytosis decreases substantially during DC maturation (3). Further progress has come from the study of DCs isolated from the secondary lymphoid organs of mice; such studies revealed the existence of multiple subpopulations of DCs that differ in phenotype, function, and microenvironmental localization (48, 67, 79).

FUNCTIONAL ASPECTS OF DCS, “IMMUNE SAVIORS”

Territorial positioning and trafficking.

LCs are among the most-studied immature DCs, serving as sentinels for pathogen entry (i.e., danger) at the epithelia of the skin or mucosa (47). The territory of immature DCs within the mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) extends from the oral cavity (38) through the respiratory (53, 54, 87), gastrointestinal (GI) (48), and genitourinary tracts (41). Recent reports indicate an increased trafficking of DCs into mucosal tissues in response to bacteria, including Moraxella spp., Bordetella spp., and Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) (54). The trafficking of DCs to and from the epithelium involves the tight regulation of selectins, chemoattractants and inflammatory chemokines, and integrins. Immature DCs in vitro express B1 integrins VLA-4 and VLA-5 and B2 integrins LFA-1, Mac-1, and p150,95 (15, 80). DCs express receptors for classic chemotactic factors found at inflamed tissue, including platelet-activating factor (PAF), fMLP, and C5a (81). Immature DCs also express the chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR5, and CCR6. CCR6 has specificity for the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 3α (MIP-3α). The constitutive expression of MIP-3α by keratinocytes may explain the positioning of LCs in the epidermis (80). The production of defensins, which bind to and activate CCR6, may also be a homing signal for DCs in the skin and mucosa (98). TNF-α and IL-1β, produced by DCs after they encounter bacteria and bacterial products or by other cells in the local environment, can activate and mobilize LCs. The mobilization of LCs involves downregulation of surface expression of E-cadherin, resulting in a loosening of their interaction with keratinocytes. This is accompanied by downregulation of chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR5, and CCR6 on DCs and upregulation of chemokine receptor CCR7 upon activation or maturation of DCs. MIP-3β is a ligand for CCR7, which is preferentially expressed within the paracortex of secondary lymphoid organs where mature DCs home (15, 80). Thus, coordinated expression of chemokines plays an important role in DC migration.

Ag capture and recognition.

The phagocytic activity of DCs has long been questioned because of the unavailability of in vitro systems capable of obtaining immature DCs (72). However, immature DCs have now been obtained in vitro and are known to efficiently internalize a diverse array of Ag, including soluble Ag (76), latex beads (69), apoptotic bodies, and live bacteria, among which are BCG (44), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (39), Bordetella bronchisepticum (35), Chlamydia trachomatis (58), Porphyromonas gingivalis (13, 14), and Borrelia burgdorferi (26), and the parasites Trypanosoma cruzi (93) and Leishmania major (6). Most of the bacteria are internalized by DCs via conventional phagocytosis and delivered in membrane-bound phagosomes. According to one study, DCs are less efficient phagocytic cells than macrophages (MΦ) (27). However, immature DCs utilize diverse pathways for internalization, such as macropinocytosis, receptor-mediated endocytosis through C-type lectin receptors (mannose receptor or DEC-205), and receptor-mediated endocytosis through Fc receptors FcγRI, -II, and -III and complement receptor CR3 (72, 76). Ag uptake receptors specific to DCs have not yet been identified; however, mannose receptors (69) and possibly langerin, a protein expressed by LC, might be involved in internalization (92). Recently discovered on MΦ is a class of receptors, the Toll-like receptors (TLR), which enable the innate immune system to discriminate gram-negative bacterial cell wall products (TLR4) from gram-positive bacterial and yeast cell wall products (TLR2) and appear to provide a link between innate and adaptive immune responses (88, 99). Apparently, DCs also express TLRs 2, 3, 4, and 9 (56, 90); however, the question of whether different TLRs are DC subset restricted is a subject of much speculation. Moreover, the role of TLRs in bacterial uptake by DCs and the effect on outcome of the immune response need further investigation.

DC maturation and Ag processing and presentation.

Regardless of the pathogenicity of the bacterial species or strain, whole bacteria appear to be universally potent in activating DC maturation. Bacterial Ag, including LPS, lipoteichoic acid, and lipoarabinomannan, are sufficient to induce an effect similar to that of bacteria (45, 71, 73, 94). DC maturation involves upregulation of MHC I and II, costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, and CD40), and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VLA4) and, as previously mentioned, downregulation of molecules involved in Ag capture (2, 3, 37, 59). The DCs thus become transformed from Ag capture cells to APC.

The processing of Ag within late endosomes involves the degradation of foreign cells and infectious microorganisms into short peptides that are bound to membrane protein of MHC II. To maximize their Ag-presenting potential, mature DCs transiently increase the biosynthesis of MHC II molecules, and most strikingly, MHC molecules are massively exported to the cell membrane, where their half-life is prolonged as the rate of endocytosis is lowered (9, 61, 70). The accumulation of high numbers of MHC II molecules on the cell membrane, together with increased expression of costimulatory molecules, allows for highly efficient Ag presentation to T lymphocytes. At the cell surface, these molecules remain stable for days and are available for recognition by CD4+ T cells. To generate CD8+ cytotoxic killer cells, DCs present Ag peptides on MHC 1 molecules, which can be loaded through both endogenous and exogenous pathways. The exogenous pathway is thought to be involved in immune responses against particulate bacterial Ag. DCs are the only APC that have developed a unique membrane transport pathway of Ag delivery from endosome to cytosol (74). Thus, in DCs, internalized Ag gain access to the cytosolic Ag-processing machinery and to the conventional MHC I presentation pathway.

The classical system for Ag presentation to T cells via MHC I and II molecules is complemented by CD1 molecules. CD1 molecules, a hallmark of the DC phenotype and a family of β-2 microglobulin-associated glycoproteins, constitute a third distinct lineage of antigen presentation molecules (63). This pathway performs the unique function of presenting nonpeptide lipid Ag to T cells. They have been shown to present glycolipids such as lipoarabinomannan, phosphatidylinositol mannosides, and mycolic acids to a distinct group of T cells (4, 55, 82). These glycolipids are abundant constituents of the cell wall of mycobacterial species including M. tuberculosis. Human T cells that recognize mycobacterial glycolipids in conjunction with CD1 produce gamma interferon, kill infected target cells, and also kill mycobacteria directly (84, 85). These findings suggest an important role for CD1 molecules in immunity to tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections. In human leprosy, a correlation between the expression of CD1 by DC and effective host immunity has been observed (83).

Cytokine milieu and immune response regulation.

For many pathogens, the outcome of the immune response to infection depends on the pattern of cytokines produced by T cells, which in part is directed by the balance of cytokines produced by cells of the innate immune system. There is striking evidence suggesting that human monocyte-derived DCs secrete IL-12 but no or little IL-10 after interaction with some gram-negative pathogens, thus skewing T-cell reactivity toward the Th1 pattern (10, 45, 49). It has been found that IL-10, a Th2-biasing cytokine, inhibits the release of IL-12 and also their effects on T cells, thus downregulating the Th1 responses. Evidence from our laboratory indicates that some LPS moieties stimulate lower levels of IL-12 and higher levels of the Th2-biasing cytokine, IL-10, from murine DCs. This results in strikingly different cytokine profiles in the T cells (B. Pulendran, C. W. Cutler, P. Kumar, M. Mohamad z adeh, T. E. Van Dyke, and J. Banchereau, submitted for publication). Somewhat paradoxically, the presence of IL-4, another Th2 cytokine, markedly increases IL-12 expression by both immature and mature DCs (23). These observations may be encouraging for the design of clinical immunotherapy strategies in which predominant Th1 (or Th2) responses are desired.

DCS, THE ACHILLES' HEEL OF THE HOST?

The negative aspects of DCs have received far less attention than their role as “immune saviors,” likely due to enthusiasm for their immunotherapeutic potential. Microorganisms have evolved strategies to suppress or subvert the immune system at every turn, and DCs may also be susceptible. Very few studies have investigated the ability (or inability) of various DC subsets to kill bacteria, although the well-developed lysosomal killing systems of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMNs) and MΦ have not been observed in DCs (71, 72). This has led to speculation that DCs might convey bacterial infection further into the body, although proof of this concept is lacking for bacteria but not for viruses (see below). Our studies suggest that the anaerobic oral pathogen P. ginaivalis survives for over 24 h within CD34+ derived DCs, while PMNs kill P. gingivalis within 60 min (13). Most studies have focused on the immunostimulatory capacity of DCs after infection. Infection of DCs by Yersinia enterocolitica diminishes the T-cell-priming capacity of DCs, which might impair or delay the elimination of bacteria (78). Immature human DCs were not able to limit the intracellular growth M. tuberculosis. Moreover, CD1 expression on DCs was downregulated by M. tuberculosis, preventing presentation of lipid Ag to cytolytic T cells (86). The silver lining of this cloud for DCs might be the ability of DCs to pick up effete MΦ and PMNs that have degraded whole bacteria, to store the predigested Ags in special acidic compartments (50), and to process them for stable MHC I/II-peptide complexes. One recent study shows that pathogenic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infects MΦ and induces their apoptosis; however, DCs capture the apoptotic MΦ and present the bacterial Ag to T cells at a much higher efficiency than that of bystander MΦ or DCs that have phagocytosed nonapoptotic MΦ (100). The parasite Plasmodium falciparum prevents the maturation of DCs (91), reducing T-cell proliferative responsiveness to the malaria parasite and to other Ag. T. cruzi was found to produce soluble factors that prevent DC maturation (93). Viruses may be particularly problematic in this regard. Vaccinia virus abortively infects both mature and immature DCs and blocks their maturation; hence, T-cell activation is impaired (24). By inhibiting the maturation pathway of DCs and inducing their death, vaccinia virus can subvert the development of efficient antiviral T-cell immunity. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is capable of replication in DCs and transmitting virus to T cells (33, 62). Recently, a new DC-restricted molecule, DC-SIGN, has been identified (29). This molecule is a specific viral receptor, promoting the binding and transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to T cells. Skin DCs have been shown to be the likely initial target of dengue virus infection in arthropod transmission of dengue virus to humans. Blood-derived DCs are 10-fold-more permissive for dengue virus infection than monocytes or macrophages (97).

In this context the potential for autoimmunity induction by DCs, particularly in response to persistent viral infection, should be noted (60). DCs can present self-Ag as well as foreign Ag; moreover, the T-cell response associated with autoimmunity (Th1) is favored by DC cytokines (22). Preliminary results, however, suggest that concerns about autoimmunity in DC-based cancer therapy may be overstated (11, 32). DCs have also been implicated in chronic inflammatory diseases, including contact dermatitis (25), periodontitis (13, 14), leprosy (83), and psoriasis (43).

INTERACTIONS OF DC WITH BACTERIA: THE KEY TO CANCER THERAPY?

Given their central role in the immune system, DCs can be an important target for vaccine development, while bacteria that induce their maturation may be logical vectors for delivering vaccine Ag. Bacteria can be engineered to express gene products of interest at the cell surface, in the cytosol, or as secreted protein (51, 75, 95) and can also serve as carriers for introducing Ag-encoding DNA into DCs (18, 20). Recombinant Streptococcus gordonii expressed on the surface the C fragment of tetanus toxin has demonstrated an extremely high capacity to deliver Ag into human monocyte-derived DCs (12). This results in DC maturation, secretion of T-cell chemoattractants and stimulation of specific CD4+ T cells. However, targeting of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, the “holy grail” of tumor immunotherapy, requires that Ag access the cytosol of APCs for loading onto MHC I. This is within the modus operandi of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes, which produces listeriolysin, enabling it to lyse the phagolysomal membrane and gain access to the cytosol (21, 30, 64). Owing to this ability, L. monocytogenes has become a highly attractive vaccine vector and has been exploited for the expression of a wide range of viral as well as tumor Ag (96). In an alternative approach, listeriolysin has also been expressed in a wide variety of vaccines composed of live bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis (5) or Mycobacterium bovis BCG (40), to promote access to the cytosol of APCs for delivery of Ag on MHC I. Coadministration of listeriolysin with soluble Ag such as OVA or nucleoprotein of influenza virus or galactosidase elicits strong CD8+ T-cell responses and weak CD4+ T-cell reactivity in mice (16, 17). In addition, the potential of several other bacterial toxins that naturally translocate into the cytosol has also been studied. Modified nontoxic versions of diptheria, pertussis, and anthrax toxins as well as Pseudomonas exotoxin A translocate peptides or whole proteins into the cytosolic processing pathway (31). In one recent study of mice, the β subunit of Shiga toxin was shown to target DCs by binding to their glycolipid Gb3 receptor. This nontoxic β subunit, fused to a tumor peptide derived from the mouse mastocytoma P815, induced specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes without the use of adjuvant (36).

Thus, a number of reports on the use of recombinant bacteria or bacterial products as vectors for proper delivery of Ag to DCs are emerging. It is tempting to speculate that in the future, this approach may lead to the cure of certain types of cancers and infectious diseases. Enthusiasm for DCs is somewhat tempered by emerging data that DCs may serve as a conveyance for pathogen invasion, in inhibition of T-cell priming, and as inducers of chronic inflammatory diseases or autoimmune phenomena.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of NIH/NIDCR grants DE13154-01 and DE14160-01 (to C.W.C. and R.J.) and DK57665-01 and AI48638-01 (to B.P.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arpinati M, Green C L, Heimfeld S, Heuser J E, Anasetti C. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilizes T helper 2-inducing dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95:2484–2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu Y T, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau J, Steinman R M. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckman E M, Porcelli S A, Morita C T, Behar S M, Furlong S T, Brenner M B. Recognition of a lipid antigen by CD1-restricted αβ+ T cells. Nature. 1994;372:691–694. doi: 10.1038/372691a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bielecki J, Youngman P, Connelly P, Portnoy D A. Bacillus subtilis expressing a haemolysin gene from Listeria monocytogenes can grow in mammalian cells. Nature. 1990;345:175–176. doi: 10.1038/345175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blank C, Fuchs H, Rappersberger K, Rollinghoff M, Moll H. Parasitism of epidermal Langerhans cells in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis with Leishmania major. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:418–425. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caux C, Massacrier C, Vanbervliet B, Dubois B, Durand I, Cella M, Lanzavecchia A, Banchereau J. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent dendritic cell pathways in response to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus tumor necrosis factor alpha. II. Functional analysis. Blood. 1997;90:1458–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caux C, Vanbervliet B, Massacrier C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, de Saint-Vis B, Jacquet C, Yoneda K, Imamura S, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors from human cord blood differentiate along two independent pathways in response to GM-CSF and TNF-α. J Exp Med. 1996;184:695–706. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cella M, Engering A, Pinet V, Pieters J, Lanzavecchia A. Inflammatory stimuli induce accumulation of MHC class II complexes on dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:782–787. doi: 10.1038/42030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehmann K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, Alber G. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:747–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colaco C A. DC-based cancer therapy: the sequel. Immunol Today. 1999;20:197–198. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corinti S, Medaglini D, Cavani A, Rescigno M, Pozzi G, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Girolomoni G. Human dendritic cells very efficiently present a heterologous antigen expressed on the surface of recombinant gram-positive bacteria to CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1999;163:3029–3036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler C W, Jotwani R, Palucka A K, Burkeholder S, Kraus E T, Banchereau J. Antigen-capture of the phagocytosis-resistant pathogen by dendritic cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 1998;(Suppl 2):60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutler C W, Jotwani R, Palucka K A, Davoust J, Bell D, Banchereau J. Evidence and a novel hypothesis for the role of dendritic cells and Porphyromonas gingivalis in adult periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 1999;34:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Amico G, Bianchi G, Bernasconi S, Bersani L, Piemonti L, Sozzani S, Montovani A, Allavena P. Adhesion, transendothelial migration and reverse transmigration of in vitro cultured dendritic cells. Blood. 1998;92:207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darji A, Chakraborty T, Wehland J, Weiss S. Listeriolysin generates a route for the presentation of exogenous antigens by major histocompatibility complex class I. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2967–2971. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darji A, Chakraborty T, Wehland J, Weiss S. TAP-dependent major histocompatibility complex class I presentation of soluble proteins using listeriolysin. Eur J Immunol. 1997;6:1353–1359. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darji A, Guzmán C A, Gerstel B, Wachholz P, Timmis K N, Wehland J, Chakraborty T, Weiss S. Oral somatic transgene vaccination using attenuated S. typhimurium. Cell. 1997;91:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daro E, Pulendran B, Brasel K, Teepe M, Pettit D, Lynch D H, Vremec D, Robb L, Shortman K, McKenna H J, Maliszewski C R, Maraskovsky E. Polyethylene glycol modified GM-CSF expands CD11b(high)CD11c(high) but not CD11b(low)CD11c(high) murine dendritic cells in vivo: a comparative analysis with Flt3 ligand. J Immunol. 2000;165:49–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich G, Bubert A, Gentschev I, Sokolovic Z, Simm A, Catic A, Kaufmann S H E, Hess J, Szalay A A, Goebel W. Delivery of antigen-encoding plasmid DNA into the cytosol of macrophages by attenuated suicide Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Biotechol. 1998;16:181–185. doi: 10.1038/nbt0298-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dietrich G, Hess J, Gentschev I, Knapp B, Kaufmann S H, Goebel W. From evil to good: a cytolysin in vaccine development. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drakesmith H, Chain B, Beverly P. How can dendritic cells cause autoimmune disease? Immunol Today. 2000;21:214–217. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebner S, Ratzinger G, Krosbacher B, Schmuth M, Weiss A, Reider D, Kroczek R A, Herold M, Heufler C, Fritsch P, Romani N. Production of IL-12 by human monocyte-derived dendritic cells is optimal when the stimulus is given at the onset of maturation and is further enhanced by IL-4. J Immunol. 2001;166:633–641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelmayer J, Larsson M, Subklewe M, Chahroudi A, Cox W I, Steinman R M, Bhardwaj N. Vaccinia virus inhibits the maturation of human dendritic cells: a novel mechanism of immune evasion. J Immunol. 1999;163:6762–6768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enk A H. Allergic contact dermatitis: understanding the immune response and potential for targeted therapy using cytokines. Molec Med Today. 1997;3:423–428. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(97)01087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Filgueira L, Nestle F O, Rittig M, Joller H I, Groscurth P. Human dendritic cells phagocytose and process Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 1996;157:2998–3005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fortsch D, Rollinghoff M, Stenger S. IL-10 converts human dendritic cells into macrophage-like cells with increased antibacterial activity against virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2000;165:978–987. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freudenthal P S, Steinman R M. The distinct surface of human blood dendritic cells, as observed after an improved isolation method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7698–7702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geijtenbeek T B, Kwon D S, Torensma R, van Vliet S J, van Duijnhoven G C, Middel J, Cornelissen I L, Nottet H S, KewalRamani V N, Littman D R, Figdor C G, van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goebel W, Kreft J. Cytolysins and the intracellular life of bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:86–88. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(96)30044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goletz T J, Klimpel K R, Leppla S H, Keith J M, Berzofsky J A. Delivery of antigens to the MHC class I pathway using bacterial toxins. Hum Immunol. 1997;54:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(97)00081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong J, Chen D, Kashiwaba M, Li Y, Chen L, Takeuchi H, Qu H, Rowse G J, Gendler S J, Kufe D. Reversal of tolerance to human MUC1 antigen in MUC1 transgenic mice immunized with fusions of dendritic and carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6279–6283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granelli-Piperno A, Delgado E, Finkel V, Paxton W, Steinman R M. Immature dendritic cells selectively replicate (M-tropic) human immunodeficiency virus type 1, while mature cells efficiently transmit both M- and T-tropic virus to T cells. J Virol. 1998;72:2733–2737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2733-2737.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grouard G, Rissoan M C, Filgueira L, Durand I, Banchereau J, Liu Y J. The enigmatic plasmacytoid T cells develop into dendritic cells with interleukin (IL)-3 and CD40-ligand. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1101–1111. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guzman C A, Rohde M, Bock M, Timmis K N. Invasion and intracellular survival of Bordetella bronchiseptica in mouse dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5528–5537. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5528-5537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haicheur N, Bismuth E, Bosset S, Adotevi O, Warnier G, Lacabanne V, Regnault A, Desaymard C, Amigorena S, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Goud B, Fridman W H, Johannes L, Tartour E. The B subunit of Shiga toxin fused to a tumor antigen elicits CTL and targets dendritic cells to allow MHC class I-restricted presentation of peptides derived from exogenous antigens. J Immunol. 2000;165:3301–3308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hart D N J. Dendritic cells: unique leukocyte populations, which control the primary immune response. Blood. 1997;90:3245–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasseus B, Jontell M, Bergenholtz G, Elkund C, Dahlgren U I. Langerhans cells from oral epithelial cells are more effective in stimulating allogeneic T cells in vitro than Langerhans cells from skin epithelium. J Dent Res. 1999;78:751–758. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780030701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson R A, Watkins S C, Flynn J L. Activation of human dendritic cells following infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1997;159:635–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hess J, Miko D, Catic A, Lehmensiek V, Russell D G, Kaufmann S H. Mycobacterium bovis Bacille Calmette-Guérin strains secreting listeriolysin of Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5299–5304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hladik F, Lentz G, Akridge R E, Peterson G, Kelley H, McElroy A, McElrath M J. Dendritic cell–T-cell interactions support coreceptor-independent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in the human genital tract. J Virol. 1999;73:5833–5842. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5833-5842.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holt PG. Pulmonary dendritic cell populations. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;329:557–562. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2930-9_93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Homey B, Dieu-Nosjean M C, Wiesenborn A, Massacrier C, Pin J J, Oldham E, Catron D, Buchanan M E, Muller A, deWaal Malefyt R, Deng G, Orozco R, Ruzicka T, Lehmann P, Lebecque S, Caux C, Zlotnik A. Upregulation of macrophage inflammatory protein-3 α/CCL20 and CC chemokine receptor 6 in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2000;164:6621–6632. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inaba K, Inaba M, Naito M, Steinman R M. Dendritic cell progenitors phagocytose particulates, including bacillus Calmette-Guerin organisms, and sensitize mice to mycobacterial antigens in vivo. J Exp Med. 1993;178:479–488. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakob T, Walker P S, Krieg A M, Udey M C, Vogel J C. Activation of cutaneous dendritic cells by CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides: a role for dendritic cells in the augmentation of Th1 responses by immunostimulatory DNA. J Immunol. 1998;161:3042–3049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashihara M, Ueda M, Horiguchi Y, Furukawa F, Hanaoka M, Imamura S. A monoclonal antibody specifically reactive to human Langerhans cells. J Invest Dermatol. 1986;87:602–607. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12455849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katz S I, Tamaki K, Sachs D H. Epidermal Langerhans cells are derived from cells originating in bone marrow. Nature. 1979;282:324–326. doi: 10.1038/282324a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelsall B L, Strober W. Distinct populations of dendritic cells are present in the subepithelial dome and T cell regions of the murine Peyer's patch. J Exp Med. 1996;183:237–247. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koch F, Stanzl U, Jennewein P, Janke K, Heufler C, Kampgen E, Romani N, Schuler G. High level IL-12 production by murine dendritic cells: up-regulation via MHC class II and CD40 molecules and down-regulation by IL-4 and IL-10. J Exp Med. 1996;184:741–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lutz M B, Rovere P, Kleijmeer M J, Rescigno M, Assmann C U, Oorschot V M, Gueze H J, Trucy J, Demandolx D, Davoust J, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Intracellular routes and selective retention of antigens in mildly acidic cathepsin D/lysosome-associated membrane protein-1/MHC class II-positive vesicles in immature dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:3707–3716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maggi T, Oggioni M R, Medaglini D, Bianchi Bandinelli M L, Soldateschi D, Wiesmuller K H, Muller C P, Valensin P E, Pozzi G. Expression of measles virus antigens in Streptococcus gordonii. New Microbiol. 2000;23:119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marakovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, Roux E R, Lyman S D, Shortman K D, McKenna H J. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1953–1961. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McWilliam A S, Napoli S, Marsh A M, Pemper F L, Nelson D J, Pimm C L, Stumbles P A, Wells T N, Holt P G. Dendritic cells are recruited into the airway epithelium during the inflammatory response to a broad spectrum of stimuli. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2429–2432. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McWilliam A S, Nelson D, Thomas J A, Holt P G. Rapid dendritic cell recruitment is a hallmark of the acute inflammatory response at mucosal surfaces. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1331–1336. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moody D B, Reinhold B B, Guy M B, Beckman E M, Frederique D E, Furlong S T, Ye S, Reinhold V N, Sieling P A, Modlin R L, Besra G S, Porcelli S. Structural requirements for glycolipid antigen recognition by CD1b-restricted T cells. Science. 1997;278:283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muzio M, Bosisio D, Polentarutti N, D'amico G, Stoppacciaro A, Mancinelli R, van't Veer C, Penton-Rol G, Ruco L P, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Differential expression and regulation of toll-like receptors (TLR) in human leukocytes: selective expression of TLR3 in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:5998–6004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nestle F O, Filgueira L, Nickoloff B J, Burg G. Human dermal dendritic cells process and present soluble protein antigens. J Investig Dermatol. 1998;110:762–766. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ojcius D M, Bravo de Alba Y, Kanellopoulos J M, Hawkins R A, Kelly K A, Rank R G, Dautry-Varsat A. Internalization of Chlamydia by dendritic cells and stimulation of Chlamydia-specific T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1297–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palucka K A, Banchereau J. Dendritic cells: A link between innate and adaptive immunity. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:12–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1020558317162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paroli M, Schiaffella E, Di Rosa F, Barnaba V. Persisting viruses and autoimmunity. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;107:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pierre P, Turley S J, Gatti E, Hull M, Meltzer J, Mirza A, Inaba K, Steinman R M, Mellman I. Developmental regulation of MHC class II transport in mouse dendritic cells. Nature. 1997;388:787–792. doi: 10.1038/42039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pope M, Betjes M G H, Romani N, Hirmand H, Cameron P U, Hoffman L, Gezelter S, Schuler G, Steinman R M. Conjugates of dendritic cells and memory T lymphocytes from skin facilitate productive infection with HIV-1. Cell. 1994;78:389–398. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Porcelli S A. The CD1 family: a third lineage of antigen-presenting molecules. Adv Immunol. 1995;59:1–98. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60629-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Portnoy D A, Chakraborty T, Goebel W, Cossart P. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1263–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1263-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pulendran B, Banchereau J, Burkeholder S, Karus E, Guinet E, Chalouni C, Caron D, Maliszewski C, Davoust J, Fay J, Palucka K. Flt3-ligand and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilize distinct human dendritic cell subsets in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:566–572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pulendran B, Lingappa J, Kennedy M, Smith J, Teepe M, Rudensky A, Maliszewski C R, Maraskovsky E. Developmental pathways of dendritic cells in vivo: distinct function, phenotype and localization of dendritic cell subsets in FLT3-ligand treated mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:2222–2231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pulendran B, Maraskovsky E, Banchereau J, Maliszewski C. Modulating the immune response with dendritic cells and their growth factors. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01794-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pulendran B, Smith J L, Caspary G, Brasel K, Pettit D, Maraskovsky E, Maliszewski C R. Distinct dendritic cell subsets differentially regulate the class of an immune response in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1036–1041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reis e Sousa C, Stahl P D, Austyn J M. Phagocytosis of ags by Langerhans cells in vitro. J Exp Med. 1993;178:509–519. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rescigno M, Citterio S, Thèry C, Rittig M, Medaglini D, Pozzi G, Amigorena S, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Bacteria-induced neo-biosynthesis, stabilization, and surface expression of functional class I molecules in mouse dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5229–5234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rescigno M, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Molecular events of bacterial-induced maturation of dendritic cells. J Clin Immunol. 2000;20:161–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1006629328178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rescigno M, Rittig M, Citterio S, Matyszak M K, Foti M, Granucci F, Martino M, Fascio U, Rovere P, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Interaction of dendritic cells with bacteria, P. 403–419. In: Lotzer M T, editor. Dendritic cells: biology and clinical applications. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riva S, Nolli M L, Lutz M B, Citterio S, Girolomoni G, Winzler C, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Bacteria and bacterial cell wall constituents induce the production of regulatory cytokines in dendritic cell clones. J Inflamm. 1996;46:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez A, Regnault A, Kleijmeer M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Amigorena S. Selective transport of internalized antigens to the cytosol for MHC class I presentation in dendritic cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:362–368. doi: 10.1038/14058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rüssmann H, Shams H, Poblete F, Fu Y, Galán J E, Donis R O. Delivery of epitopes by the Salmonella type III secretion system for vaccine development. Science. 1998;281:565–568. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5376.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sallusto F, Cella M, Danieli C, Lanzavecchia A. Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment: down-regulation by cytokines and bacterial products. J Exp Med. 1995;182:389–400. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and down regulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schoppet M, Bubert A, Huppertz H I. Dendritic cell function is perturbed by Yersinia enterocolitica infection in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;122:316–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shortman K. Burnet oration: dendritic cells: multiple subtypes, multiple origins, multiple functions. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:161–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Mantovani A. Chemokines and dendritic cell traffic. J Clin Immunol. 2000;20:151–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1006659211340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sozzani S, Luini W, Borsatti A, Ploentarutti N, Zhou D, Piemonti L, D'Amico G, Power C A, Wells T N, Gobbi M, Allavana P, Mantovani A. Receptor expression and responsiveness of human dendritic cells to a defined set of CC and CXC chemokines. J immunol. 1997;159:1993–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sieling P A, Chatterjee D, Porcelli S A, Prigozy T I, Mazzaccaro R J, Soriano T, Bloom B R, Brenner M B, Kronenberg M, Brennan P J, et al. CD1-restricted T cell recognition of microbial lipoglycan antigens. Science. 1995;269:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.7542404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sieling P A, Jullien D, Dahlem M, Tedder T F, Rea T H, Modlin R L, Porcelli S A. CD1 expression by dendritic cells in human leprosy lesions: correlation with effective host immunity. J Immunol. 1999;162:1851–1858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stenger S, Hanson D A, Teitelbaum R, Dewan P, Niazi K R, Froelich C J, Ganz T S, Thoma-Uszynski S, Melian A, Bogdan C, Porcelli S A, Bloom B R, Krensky A M, Modlin A M. An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science. 1998;282:121–125. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stenger S, Mazzaccaro R J, Uyemura K, Cho S, Barnes P F, Rosat J P, Sette A, Brenner M B, Porcelli S A, Bloom B R, Modlin R L. Differential effects of cytolytic T cell subsets on intracellular infection. Science. 1997;276:1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stenger S, Niazi K R, Modlin R L. Down-regulation of CD1 on antigen-presenting cells by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1998;161:3582–3588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stumbles P A, Thomas J A, Pimm C L, Lee P T, Vanaill T J, Proskch S, Holt P G. Resting respiratory tract dendritic cells preferentially stimulate T helper cell type 2 (Th2) responses and require obligatory cytokine signals for induction of Th1 immunity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2031–2036. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Takada H, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 1999;11:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomas R, Davis L S, Lipsky P E. Isolation and characterization of human peripheral blood dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:821–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thoma-Uszynski S, Kiertscher S M, Ochoa M T, Abouis D, Norgard M V, Miyake K, Godowski P J, Roth M D, Modlin R L. Activation of toll-like receptor 2 on human dendritic cells triggers induction of IL-12, but not IL-10. J Immunol. 2000;165:3804–3810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Urban B C, Ferguson D J P, Pain A, Willcox N, Plebansky M, Austyn J M, Roberts D J. Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes modulate the maturation of dendritic cells. Nature. 1999;400:73–77. doi: 10.1038/21900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Valladeau J, Ravel O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Moore K, Kleijmeer M, Liu Y, Duvert-Frances V, Vincent C, Schmitt D, Davoust J, Caux C, Lebecque S, Saeland S. Langerin, a novel C-type lectin specific to Langerhans cells, is an endocytic receptor that induces the formation of Birbeck granules. Immunity. 2000;12:71–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Van Overtvelt L, Vanderheyde N, Verhasselt V, Ismaili J, De Vos L, Goldman M, Willems F, Vray B. Trypanosoma cruzi infects human dendritic cells and prevents their maturation: inhibition of cytokines, HLA-DR, and costimulatory molecules. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4033–4040. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4033-4040.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Verhasselt V, Buelens C, Willems F. F, De Groote D, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Goldman M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide stimulates the production of cytokines and the expression of costimulatory molecules by human peripheral blood dendritic cells: evidence for a soluble CD14-dependent pathway. J Immunol. 1997;158:2919–2925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Verjans G M G M, Janssen R, UytdeHaag F G C M, van Doornik C E M, Tommassen J. Intracellular processing and presentation of T cell epitopes, expressed by recombinant Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, to human T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:405–410. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Weiskirch L M, Paterson Y. Listeria monocytogenes: a potent vaccine vector for neoplastic and infectious disease. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:159–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wu S J, Grouard-Vogel G, Wellington S, Mascola J R, Brachtel E, Putvatana R, Louder M K, Filgueira L, Marovich M A, Wong H K, Blauvelt A, Murphy G S, Robb M L, Innes B L, Birx D L, Hayes C G, Frankel S S. Human skin Langerhans cells are targets of dengue virus infection. Nat Med. 2000;6:816–820. doi: 10.1038/77553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang D, Chertov O, Bykovskala S N, Chen Q, Buffo M J, Anderson M, Schroeder J M, Wang J M, Howard O M Z, Oppenhein J J. Beta-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yang R B, Mark M R, Gray A, Huang A, Xie M H, Zang M, Goddard A, Wood W I, Gurney A L, Godowski P J. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signaling. Nature. 1998;395:284–288. doi: 10.1038/26239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yrlid U, Wick M J. Salmonella-induced apoptosis of infected macrophages results in presentation of a bacteria-encoded antigen after uptake by bystander dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:613–623. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhou L J, Tedder T F C D. CD14 + blood monocytes can differentiate into functionally mature CD83+ dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2588–2592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]