Key Points

Question

What is known about the frequency, nature, and consequences of care partners’ uptake and use of the patient portal?

Findings

This scoping review including 41 studies noted that few care partners are formally registered for the patient portal but that informal portal use, with patient identity credentials, is common. Patients and care partners identified the need for and potential benefits of care partner engagement in the patient portal.

Meaning

The findings of this scoping review suggest that health care systems have directed limited effort toward engaging care partners in the patient portal, despite identified potential benefits.

Abstract

Importance

Family and other unpaid care partners may bridge accessibility challenges in interacting with the patient portal, but the extent and nature of this involvement is not well understood.

Objective

To inform an emerging research agenda directed at more purposeful inclusion of care partners within the context of digital health equity by (1) quantifying care partners’ uptake and use of the patient portal in adolescent and adult patients, (2) identifying factors involving care partners’ portal use across domains of the System Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety model, and (3) assessing evidence of perceived or actual outcomes of care partners’ portal use.

Evidence Review

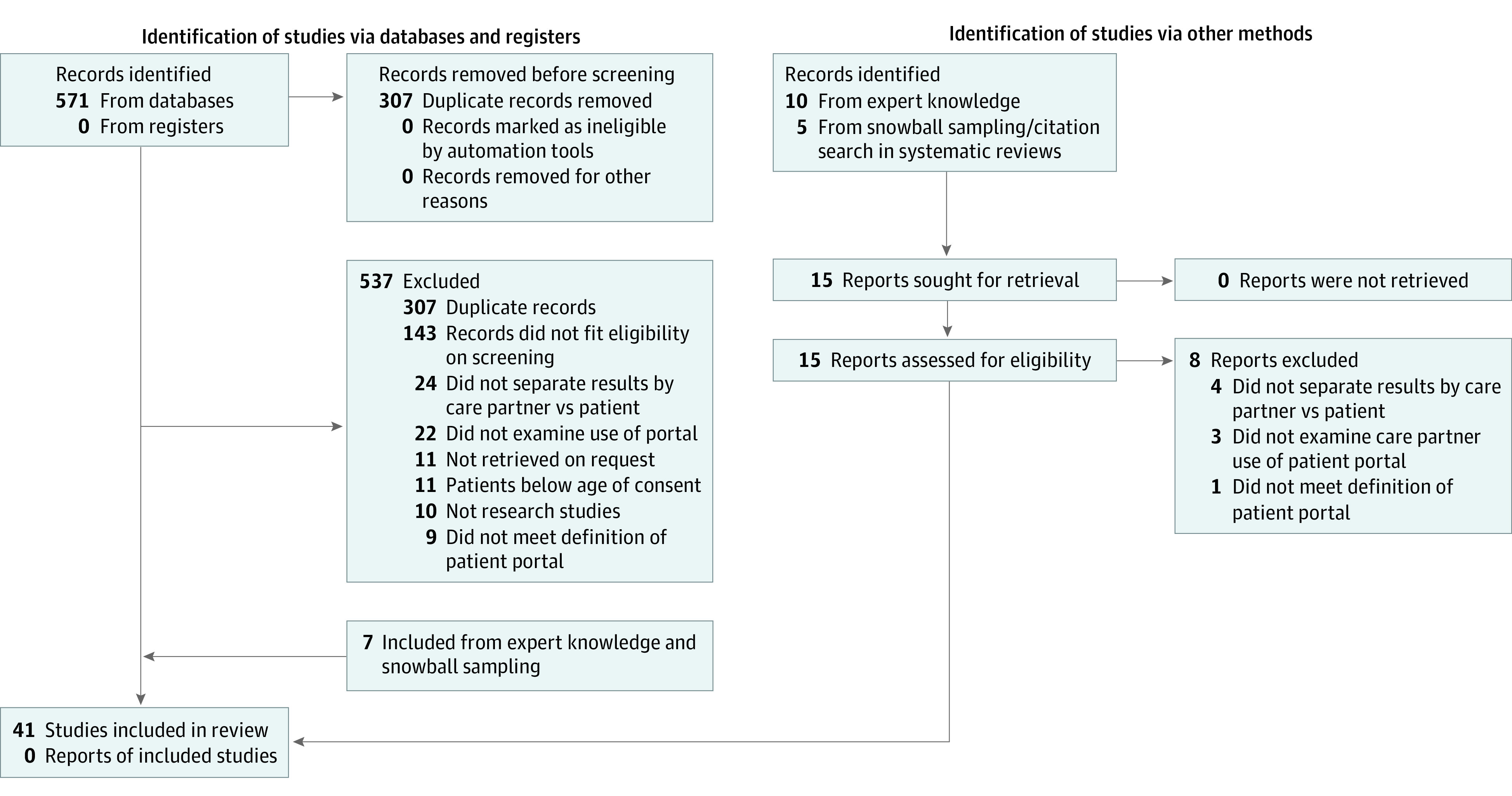

Following Arksey and O’Malley’s methodologic framework, a scoping review of manuscripts published February 1 and March 22, 2022, was conducted by hand and a systematic search of PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase, and Web of Science. The search yielded 278 articles; 125 were selected for full-text review and 41 were included.

Findings

Few adult patient portal accounts had 1 or more formally registered care partners (<3% in 7 of 7 articles), but care partners commonly used the portal (8 of 13 contributing articles reported >30% use). Care partners less often authored portal messages with their own identity credentials (<3% of portal messages in 3 of 3 articles) than with patient credentials (20%-60% of portal messages in 3 of 5 articles). Facilitators of care partner portal use included markers of patient vulnerability (13 articles), care partner characteristics (15 articles; being female, family, and competent in health system navigation), and task-based factors pertaining to ease of information access and care coordination. Environmental (26 articles) and process factors (19 articles, eg, organizational portal registration procedures, protection of privacy, and functionality) were identified as influential to care partner portal use, but findings were nuanced and precluded reporting on effects. Care partner portal use was identified as contributing to both patient and care partner insight into patient health (9 articles), activation (7 articles), continuity of care (8 articles), and convenience (6 articles).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this scoping review, care partners were found to be infrequently registered for the patient portal and more often engaged in portal use with patient identity credentials. Formally registering care partners for the portal was identified as conferring potential benefits for patients, care partners, and care quality.

This scoping review describes the use of patient portals by patient care partners.

Introduction

The patient portal has assumed a prominent role in efforts to engage patients in their care through facilitating information access, health care management, and communication with the care team.1,2,3,4,5,6 Systematic reviews suggest that use of the patient portal may be associated with improved patient decision-making, self-efficacy, and behavioral outcomes, such as treatment adherence,7,8,9 through varied pathways involving convenience, continuity in care, activation, and understanding.10,11,12 However, individuals who are older, less educated, and with less technology experience are less likely to use a patient portal,13,14 less able to perform health management tasks electronically,15,16 and more reliant on others to navigate health system demands.17

Care partner engagement may bridge digital literacy demands of patients who have difficulty accessing the patient portal.18,19 Many health systems allow patients to authorize a family member or trusted friend shared access to their patient portal account using the designee’s own identity credentials.20 Preliminary studies suggest that shared access may facilitate improved patient and family satisfaction with communication, agreement about treatments, and confidence in managing care21,22 and that it is commonly desired by patients and valued by families.23

To our knowledge, national information enumerating uptake of shared access does not exist, but implementation of this functionality by health systems has been variable,20,24 and anecdotal evidence suggests it is limited.25,26 In the absence of straightforward processes to access patient health information with their own credentials, care partners may access the portal using patient credentials.7,26,27 Having a stronger understanding of the extent and nature of care partners’ portal use could benefit efforts to support safe and clinically appropriate care that is respectful of and responsive to patient preferences and promote learning health system initiatives28,29 to monitor care quality and outcomes in populations with greater vulnerability.30,31

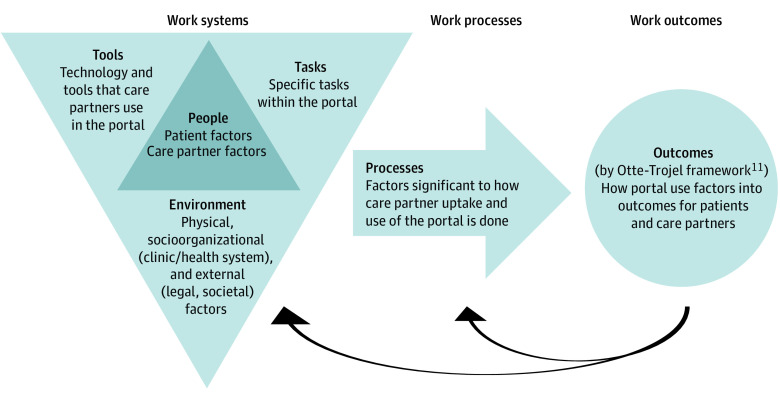

Consistent with the nascent and diffuse nature of available evidence, we undertook a scoping review to consolidate studies that have examined care partner use of patient portals in adolescent and adult patient populations. We had 3 aims: (1) to identify studies that have quantified the extent of care partner uptake and use of the patient portal; (2) to assess the extent and type of evidence identifying factors affecting care partner use of the patient portal, drawing on the System Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model; and (3) to map findings from studies that have examined perceived or actual effects of care partner use of the patient portal on care partner capacity and patient outcomes. The overall objective of our study was to inform an emerging research agenda directed at more purposeful inclusion of care partners within the context of digital health equity.

Methods

Our methods align with the scoping review typology in supporting systematic, transparent, and replicable results and consolidating evidence that pertains to an emerging topic of inquiry.32,33 We followed Arksey and O’Malley’s34 methodologic framework for scoping reviews and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) extension for a scoping review checklist. Our definition of care partners encompasses nonclinicians other than the patient who access or use the patient portal on the patient’s behalf, including family members, trusted friends, and legal guardians. We defined the patient portal as a patient-facing, web-based technology offered by health care organizations to provide patients with access to their medical records.

Study Identification

We iteratively developed the search strategy in consultation with an experienced medical librarian (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and PsycInfo using search terms and MeSH headings that included key words related to patient portal in combination with care partner, (informal) caregiver, family, parent, proxy, and legal guardian. We conducted our search between February 1 and March 2, 2022. No date, language, or location limits were imposed. We included peer-reviewed qualitative and quantitative articles describing care partner use of the patient portal. We additionally conducted a hand search of the literature using expert knowledge and drawing on reference lists of relevant literature reviews. Reviews and nonempirical articles, such as commentaries, and articles using the term caregiver but describing professional health care professionals or clinicians were excluded. Articles were excluded that did not meet our definition of a patient portal or did not separate care partner use from patient use of the portal. We excluded studies of pediatric populations under the age of consent due to the well-accepted legal authority of parents and guardians. The PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) summarizes our search and screening process.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Flow Diagram of Scoping Review Search.

Article Selection

Our 2-step screening process, facilitated by Covidence 2022 literature review software, consisted of title and abstract scan, followed by full-text review by 2 independent screeners (K.T.G., D.P., and A.W.) to confirm article eligibility. During the full-text review, reviewers applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to the remaining articles and discussed discrepancies as a group to reach consensus.

Charting the Data and Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

A data extraction tool from the Joanna Briggs Institute33 was adapted (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The approach to summarizing and reporting on findings from identified articles varied by research question (RQ). We first compiled articles that quantitatively assessed care partners’ uptake and use of patient portals (RQ1) by focusing on key parameters, such as year, setting, population, and identity credentials (patient vs care partner), including use of direct messaging,18,35 which is uniquely able to determine sender identity. We then performed a thematic analysis to synthesize information from articles that reported on factors associated with care partner engagement (RQ2) and outcomes resulting from care partner portal use (RQ3). Analyses pertaining to RQ2 involved mapping each factor to the components described in the SEIPS model36,37 and categorizing findings by whether each factor was a facilitator, barrier, nonsignificant (quantitative analyses), or did not specify directionality with respect to motivating care partner uptake and use of the patient portal. Analyses pertaining to RQ3 involved mapping findings to consequences of care partner use of the portal following the Otte-Trojel framework,11 which we adapted to reflect care partner involvement.

Results

Characteristics of included articles are summarized in Table 1 and individually presented in eTable 3 in Supplement 1. Of the 41 articles included in this review, 24 used quantitative methods, 10 used qualitative methods, and 7 used mixed methods. All but 4 studies were conducted in the US, and nearly half (19 [46.3%]) were published in 2020-2022. Most of the studies examined adults (23 [56.1%]); fewer studies examined adolescents (7 [17.1%]) or older adults (5 [12.2%]).

Table 1. Characteristics of 41 Included Studies.

| Variable | Studies, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1a | RQ2b | RQ3c | Total | |

| Country | ||||

| US | 18 (100) | 20 (83.3) | 12 (92.3) | 37 (90.2) |

| Otherd | 0 | 4 (16.7) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (9.8) |

| Year published | ||||

| 2020-2022 | 10 (55.6) | 11 (45.8) | 6 (46.2) | 19 (46.3) |

| 2015-2019 | 7 (38.9) | 10 (41.7) | 6 (46.2) | 17 (41.5) |

| 2014 or earlier | 1 (5.6) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (12.2) |

| Data collection | ||||

| Focus groups/interviews | 0 | 10 (41.7) | 6 (46.2) | 10 (24.4) |

| Survey | 5 (27.8) | 8 (33.3) | 1 (7.7) | 12 (29.3) |

| EMR/portal data | 11 (61.1) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) | 13 (31.7) |

| Multiple | 2 (11.1) | 3 (12.5) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (14.6) |

| Approach | ||||

| Quantitative | 15 (83.3) | 11 (45.8) | 4 (30.8) | 24 (58.5) |

| Qualitative | 0 | 10 (41.7) | 6 (46.2) | 10 (24.4) |

| Mixed methods | 3 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (23.1) | 7 (17.1) |

| Setting | ||||

| Health system | 11 (61.1) | 11 (45.8) | 6 (46.2) | 17 (41.5) |

| Multiple health systems | 1 (5.6) | 6 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | 8 (19.5) |

| Clinical practice site | 2 (11.1) | 8 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) | 10 (24.4) |

| Outside health care delivery | 4 (22.2) | 4 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 6 (14.6) |

| Sample size | ||||

| <50 | 0 | 8 (33.3) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (19.5) |

| 50-99 | 0 | 5 (20.8) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (14.6) |

| 100-499 | 4 (22.2) | 8 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) | 9 (22.0) |

| ≥500 | 14 (77.8) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (23.1) | 18 (43.9) |

| Age group | ||||

| Adolescents | 4 (22.2) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (7.7) | 7 (17.1) |

| Adults | 12 (66.7) | 12 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) | 23 (56.1) |

| Older adults | 1 (5.6) | 5 (20.8) | 4 (30.8) | 5 (12.2) |

| All ages | 1 (5.6) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (7.3) |

| NA or unknown | 0 | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 3 (7.3) |

| Sample characteristics | ||||

| General patient population | 12 (66.7) | 11 (45.8) | 7 (53.8) | 24 (58.5) |

| Illness specific | 6 (33.3) | 13 (54.2) | 6 (46.2) | 17 (41.5) |

Abbreviations: EMR, electronic medical record; NA, not available; RQ, research question.

What is the extent and nature of evidence quantifying care partners’ use of the patient portal in adolescent and adult patient populations, and to what extent does available evidence differentiate between the use of care partner vs patient identity credentials?

To what extent has prior evidence identified people, environmental, tools, and task-specific factors drawn from the System Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety model, affecting care partner access and use of the patient portal?

What is the extent of available evidence describing perceived or actual effects of care partner use of the patient portal on care partner capacity (knowledge and behaviors) and patient outcomes?

Two studies were conducted in Canada, 1 in Germany, and 1 in Ireland.

Care Partner Registration and Use of the Patient Portal

Seven articles described care partner registration for adolescent (n = 1) or adult (n = 6) portal accounts from date/time-stamped electronic health record data (Table 2). Analyses were primarily conducted at academic medical centers (n = 4) or integrated managed care consortiums (n = 2) and about evenly divided between examining all registered users (n = 4) or cohorts of disease-specific populations (n = 3). All 6 studies of adult patients found less than 3% of portal accounts to have a formally registered care partner. The 1 study of adolescent patients reported 25.7% of portal accounts belonged to the adolescent, 0.8% belonged to a delegate (eg, parent or guardian of an adult for adolescents aged ≥18), and 73.5% belonged to a surrogate (eg, parent or guardian of a child).

Table 2. Articles Examining Care Partner Access and Use of the Patient Portal.

| Study characteristic | Adolescents | Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: care partner registration for the portal | ||

| No. of articles | 1 | 6 |

| Health care professional | ||

| Academic medical center | 1 | 3 |

| Integrated managed care consortium | 0 | 2 |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 |

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Registered users | 1 | 3 |

| Cohort defined by health condition | 0 | 3 |

| Care partner registration, % | ||

| <1 | 1a | 1 |

| 1-3 | 0 | 5 |

| >3 | 1a | 0 |

| Panel B: care partner use of the portal | ||

| No. of articles | 3 | 10 |

| Data source | ||

| Electronic medical record | 3 | 4 |

| Survey | 0 | 6 |

| Health care professional | ||

| Academic medical center | 3 | 3 |

| Integrated managed care consortium | 0 | 2 |

| Not reported | 0 | 5 |

| Proportion of care partners using the portal, % | ||

| <10 | 0 | 2 |

| 10-30 | 0 | 3 |

| >30 | 3 | 5 |

| Panel C: care partner engagement in direct messaging through the portal | ||

| No. of articles | 1 | 5 |

| Health care professional | ||

| Academic medical center | 0 | 2 |

| Integrated managed care consortium | 0 | 1 |

| Other/not reported | 1 | 2 |

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Registered users | 1 | 3 |

| Cohort defined by health condition | 0 | 2 |

| Care partner direct messaging | ||

| Using own identity credentials, % | ||

| <1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1-3 | 0 | 2 |

| Using patient identity credentials, % | ||

| <5 | 0 | 1 |

| 5-20 | 0 | 1 |

| 21-60 | 1 | 2 |

Steitz et al38 differentiated delegates from surrogates. Delegates were defined as proxies for adults; surrogates were defined as proxies for children or adolescents younger than 18 years.

Thirteen articles described care partner portal use among adolescent (n = 3) or adult (n = 10) patients (Table 2). These analyses were about evenly split between survey-based (n = 6) and electronic medical record–based (n = 7) data. About half were conducted at academic medical centers (n = 6) or integrated managed care consortiums (n = 2). Among adult samples, 2 of 10 articles reported less than 10% of care partners used the portal, 3 of 10 articles reported 10% to 30% of care partners used the portal, and half (5 of 10 articles) reported greater than 30% of care partners used the portal. All 3 articles on adolescents reported greater than 30% of care partners used the portal.

Six articles examined secure messaging content to determine care partner authorship of messages sent through adolescent (n = 1) or adult (n = 5) patient portal accounts (Table 2). Half of these analyses were conducted at academic medical centers or integrated managed care consortiums (n = 3). Two-thirds of articles (n = 4) examined all registered users and 1 of 3 of articles (2 of 6 articles) examined cohorts of specific populations (persons with diabetes and adults aged ≥85 years). The 3 studies that examined care partner messaging with their own identity credentials found these messages comprised less than 3% of adult patient messages. Of the 4 studies examining care partner messaging with patient identity credentials, 1 article reported that care partners authored less than 5% of messages, 1 article reported care partners authored 5% to 20% of messages, and half (2 of 4 articles, which studied persons with diabetes and adults aged ≥85 years) reported that care partners authored 20% to 60% of messages. The 1 study of adolescents reported 20% to 60% of messages were sent by care partners using the adolescent’s identity credentials.

Factors Associated With Care Partner Use of the Patient Portal

Thirty-two articles reported on factors associated with care partner uptake or use of the portal (Table 3). These factors were categorized by domains of the SEIPS model, differentiating person factors (reporting on patients and care partners separately), environment, tasks, and organization (Figure 2).

Table 3. Factors Associated With Care Partner Uptake and Use of the Patient Portal by the SEIPS Model.

| SEIPS factor | No. of identified studies by study design | Total studies, No. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Quantitative | |||||||

| Facilitator | Barrier | Neither | Facilitator | Barrier | NS | Neither | ||

| Work system factors (person-patient) | ||||||||

| Need for assistance with health system navigation | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Illness severity | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Adolescents: younger age | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Adults: older age | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Mental health condition | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| White race | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Work system factors (person-care partner) | ||||||||

| Health literacy level/educational level | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| Female gender | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Relationship to patient: family vs nonfamily | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| White race | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Household income | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Technology experience | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Work system factors: environment (physical, socioorganizational, external) | ||||||||

| Organizational policy and functionality to enable proxy access | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Clinic staff awareness of proxy access | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| State laws | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Internet access | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Work system factors (tasks) | ||||||||

| Access to information | 5 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Coordination of care | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Processes factors: how work is done and how it flows (care processes) | ||||||||

| Privacy and security | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Review of proxy access status | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| Convenience of access type | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviations: NS, nonsignificant; SEIPS, System Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety.

Figure 2. Factors Affecting Care Partner Uptake and Use of the Patient Portal Applied to the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety Simplified Model.

People: Patient Factors

Need for assistance with health system navigation was consistently found to facilitate care partner use of the portal (7 articles)26,39,40,41,42,43,44 due to gaps in technology literacy,44 English proficiency,39 and illness severity.21,39,45,46,47,48,49 Younger adolescent age (2 of 4 articles)20,38 and older age among adults (3 of 4 articles)26,39,50 facilitated care partner use of the patient portal. Findings regarding race and ethnicity were limited and mixed (2 articles).39,51

Care Partner Factors

Greater health literacy and educational level (5 of 8 articles),25,26,45,52,53 female gender (5 articles),25,45,47,48,54 and being a family member (6 articles)25,26,42,45,47,53 were facilitators of care partner use of the portal. Evidence regarding care partner race (5 articles)25,45,53,54,55 and household income (5 articles)21,25,45,53,55 was mixed. Two articles26,54 examined care partners’ use of their own portal and both found it to be a facilitator.

Environmental Factors

Organizational factors were most often reported as impeding care partner portal use (3 of 5 articles)47,52,56 or spoke to relevance without specifying directionality (3 of 5 articles).46,57,58 For example, 1 study56 found 7% of hospital personnel did not know about proxy access and nearly half (45%) endorsed patient sharing of credentials with care partners. Two articles57,58 describing organizational policies and procedures described the value of graduated proxy access in which the patient controls levels of information access and use of specific functionality. One article46 highlighted the importance of state information privacy laws.

Tasks

The ability to access patient health information was consistently identified as facilitating care partner portal use (8 of 12 articles),22,26,42,44,45,59,60,61 with the remaining 4 articles49,50,52,62 emphasizing importance without specifying directionality and identifying care coordination (eg, messaging, appointment scheduling, and filling prescriptions) as facilitating care partner portal use (8 articles).30,40,42,45,50,52,59,61

Care Processes

Findings relating to care process factors were nuanced and complex. In the 8 articles20,40,41,44,46,49,60,62 that reported on privacy and security, 240,44 found privacy and security considerations were a facilitator, 246,60 found them to be a barrier, and 420,41,49,62 did not specify directionality. For example, 2 articles40,44 reported that privacy and security facilitated care partners’ portal use by explicitly granting permission. However, 2 articles46,60 reported that privacy and security was a perceived barrier to care partner portal use as patients were concerned about another person accessing their personal health and billing information.

Seven articles20,44,57,58,59,62,63 reported on health care system processes for proxy access review, although little insight could be gleaned regarding specific practices. In 1 article,44 patients voiced that both giving and removing care partner access made them feel in control of health information sharing. In 2 articles,46,59 patients expressed the desire to differentiate graduated access to care partners for specific functionality.

Consequences of Care Partner Use of the Patient Portal by the Otte-Trojel Framework

Thirteen articles,21,25,41,42,44,45,52,59,61,62,64,65,66 primarily qualitative (8 of 13 articles),41,42,44,45,59,63,64,66 reported on consequences of care partner portal use (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Care partner use of the portal was found to contribute insight into patient health and personhood ( 9 of 16 articles).21,41,42,44,59,61,62,64,65 Care partners were described as an interpreter of health information in the portal,42,64 thereby enhancing patient understanding.41 Care partner portal access was reported to benefit continuity of care (8 of 16 articles)21,25,41,44,59,61,65,66 by improving recall of the plan of care61 and understanding reasons for referrals.65 Seven articles42,44,45,61,64,65,66 reported that care partner portal use affected activation of health information by, for example, promoting desired health behaviors.44,64 Six articles25,42,52,60,61,66 reported on convenience of care partner use of the patient portal, for example, to “pull-up” the portal when the patient was unavailable66 or in the event of an emergency.42

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assemble evidence describing the prevalence and consequences of care partner uptake and use of the patient portal and systematically evaluate factors that facilitate or impede this involvement. We found that formal registration for proxy (shared) portal access is low and that care partners more often rely on patient identity credentials. Care partner characteristics, including female gender, family relationship, and greater capacity to engage in health system navigation, were identified as potentially associated with portal use, as was assisting patients with markers of greater vulnerability. Environmental and process factors, including transparency of registration procedures and graduated access type, were identified as important to patients and care partners yet were rarely reported at a health system level. Both patients and care partners reported utility in access to information and coordination of care made possible through the portal, and care partner use of the portal was overwhelmingly associated with positive consequences through mechanisms involving insight into patient health and personhood, activation of information, continuity of care, and convenience.

By compiling available evidence regarding care partner involvement in the patient portal, our study contributes new knowledge in an area that has been only anecdotally recognized to date. The patient portal has been embraced as a mainstream strategy to engage patients in their care,9,18 yet care partners have been largely excluded from accumulating knowledge and interventional efforts,9,18,19,67 despite their essential role in managing and coordinating care alongside patients who are most vulnerable.68,69,70 One small study21 suggests the feasibility of systems-level strategies to increase care partner registration and use of portal, although further work is needed to understand prospects for broader scaling. We observed similar issues across the age span from adolescents through older adults, with care partners (from parents of adolescents to adult children of older adults) primarily accessing the patient portal using patient log-in credentials.51,71 Both patients and care partners were found to express preferences for improved functionality around proxy access.46

Our findings suggest the relevance of organizational factors in care partner uptake of the patient portal but do not indicate specific health system policy, technology, or workflows that facilitate proxy access and instead demonstrate inconsistent policies, features, and awareness surrounding proxy access. Sharing credentials can lead to data security and privacy problems by revealing more information than desired by the patient30,42,56 and contribute to confusion and mistakes when clinicians do not know with whom they are interacting electronically30 or when legal documents submitted through the patient portal by someone other than the patient must be retracted.72,73 Findings from our study suggest the need for stronger evidence regarding best practices in clinician- and electronic medical record vendor–initiated efforts to raise awareness of proxy access and simplify proxy registration. Despite patients wanting greater control over their health information, few health systems afford graduated portal access allowing patients to limit specific portal features available to a care partner; other systems limit patients to 1 registered care partner at a time.20

Nearly half of the articles in this review were published between 2020 and 2022, perhaps reflecting increased interest and use of the patient portal during the pandemic.74,75 However, we found no temporal difference in care partners’ use of the patient portal in more recent years. Our results suggest that, despite expanded functionality and use of the patient portal, shared and proxy portal registration and use remain limited. Strategies used to increase patient portal access among patients, including targeting both patients and clinicians or staff,76 could be adapted to increase proxy access.

Patient portals have been widely scaled throughout care delivery (as many as 90% of health care systems and professionals offer portal access),77 yet just 38% of individuals reported they accessed the portal in a national survey conducted in 2020.78 For patients who could most benefit from transparent information access and bidirectional communication with clinicians, the patient portal is more often out of reach due to lower health literacy, limited technology access and experience, or cognitive impairment.19,67,76 While training could be a valuable step in systems-level strategies that respect patients’ preferences in managing their care,29 such efforts are limited in mainstream care.28 Our review extends observations supporting the role of care partners as both an underused and underevaluated aspect of patient engagement76 by assembling the available but diffuse evidence base regarding their role and its consequences in attenuating patient barriers with health system navigation through patient portal access.

Limitations

This scoping review has limitations. The review was limited to studies that explicitly examined care partner use of portals. Studies were excluded that examined portal use among both patients and care partners without specifically differentiating between the 2 user groups. Factors influencing patient uptake of the portal would directly affect care partner uptake, but these studies were outside of the scope of this review. Most studies did not identify the relationship of the care partner to the patient. As care partner relationship may affect legal access to the patient’s health information, it is an important consideration that merits interrogation in future studies. Several of the studies in this review were conducted at the same institution and on the same data set or were qualitative studies with rich data but small sample sizes. Thus, there are limitations on our ability to generalize the findings of this review to the larger population. Studies were overwhelmingly observational, we did not appraise the quality of the evidence, and it was not possible to conclusively determine whether and which use of portal functionality (eg, messaging, scheduling, or prescription refills) directly increased care partner uptake.

Conclusions

The patient portal is increasingly a prerequisite to accessing and coordinating care by enabling asynchronous patient-clinician interaction, facilitating broader access to health information, and affording greater convenience in managing health tasks, such as scheduling appointments and filling prescriptions.9,11 This review noted that care partners commonly use the patient portal but that their interactions more often occur informally through sharing of patient identity credentials and that health care systems have to date devoted limited attention toward clarifying and facilitating appropriate involvement. Study findings link to ongoing practice initiatives focused on creating learning health systems,79,80 particularly for at-risk subgroups (eg, persons with dementia), and embedded pragmatic trials that leverage health information technology to scale best practices.81 Organizations tasked with motivating care quality, such as the Joint Commission and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, must drive transparency and accountability in health systems’ reporting on shared access uptake and ways they promote functionality for user-friendly shared access, particularly for subgroups in which care partners play a large role in care management. For example, electronic health records have, so far, fallen short on serving the specific needs of older adults,28 and shared access is highly aligned with such initiatives as the age-friendly health system.29,82 This scoping review provides a grounding for the current state of proxy access and suggests the need for greater attention to relevant policy and organizational practices.

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Data Extraction Table

eTable 3. Detailed Characteristics of Studies Included in Scoping Review

eTable 4. Consequences of Care Partner Use of the Patient Portal by the Otte-Trojel Framework

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Lum HD, Brungardt A, Jordan SR, et al. Design and implementation of patient portal-based advance care planning tools. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(1):112-117.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan SR, Brungardt A, Phimphasone-Brady P, Lum HD. Patient perspectives on advance care planning via a patient portal. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(8):682-687. doi: 10.1177/1049909119832820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brungardt A, Daddato AE, Parnes B, Lum HD. Use of an ambulatory patient portal for advance care planning engagement. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32(6):925-930. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2019.06.190016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nittas V, Lun P, Ehrler F, Puhan MA, Mütsch M. Electronic patient-generated health data to facilitate disease prevention and health promotion: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(10):e13320. doi: 10.2196/13320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demiris G, Iribarren SJ, Sward K, Lee S, Yang R. Patient generated health data use in clinical practice: a systematic review. Nurs Outlook. 2019;67(4):311-330. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mafi JN, Gerard M, Chimowitz H, Anselmo M, Delbanco T, Walker J. Patients contributing to their doctors’ notes: insights from expert interviews. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(4):302-305. doi: 10.7326/M17-0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM, et al. Electronic patient portals: evidence on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):677-687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Hoerbst A. The impact of electronic patient portals on patient care: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e162. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han HR, Gleason KT, Sun CA, et al. Using patient portals to improve patient outcomes: systematic review. JMIR Hum Factors. 2019;6(4):e15038. doi: 10.2196/15038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e148. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Otte-Trojel T, de Bont A, Rundall TG, van de Klundert J. How outcomes are achieved through patient portals: a realist review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):751-757. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lusignan S, Mold F, Sheikh A, et al. Patients’ online access to their electronic health records and linked online services: a systematic interpretative review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e006021. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborn CY, Mayberry LS, Wallston KA, Johnson KB, Elasy TA. Understanding patient portal use: implications for medication management. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(7):e133. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palen TE, Ross C, Powers JD, Xu S. Association of online patient access to clinicians and medical records with use of clinical services. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2012-2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taha J, Czaja SJ, Sharit J, Morrow DG. Factors affecting usage of a personal health record (PHR) to manage health. Psychol Aging. 2013;28(4):1124-1139. doi: 10.1037/a0033911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czaja SJ, Sharit J, Lee CC, et al. Factors influencing use of an e-health website in a community sample of older adults. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(2):277-284. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-000876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JL, Boyd CM. A look at person- and family-centered care among older adults: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1497-1504. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3359-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonio MG, Petrovskaya O, Lau F. The state of evidence in patient portals: umbrella review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(11):e23851. doi: 10.2196/23851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossman LV, Masterson Creber RM, Benda NC, Wright D, Vawdrey DK, Ancker JS. Interventions to increase patient portal use in vulnerable populations: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):855-870. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff JL, Kim VS, Mintz S, Stametz R, Griffin JM. An environmental scan of shared access to patient portals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(4):408-412. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolff JL, Aufill J, Echavarria D, et al. A randomized intervention involving family to improve communication in breast cancer care. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):14. doi: 10.1038/s41523-021-00217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff JL, Aufill J, Echavarria D, et al. Sharing in care: engaging care partners in the care and communication of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177(1):127-136. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05306-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zulman DM, Nazi KM, Turvey CL, Wagner TH, Woods SS, An LC. Patient interest in sharing personal health record information: a web-based survey. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(12):805-810. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epic Patient Portal Use by Proxies. Health Information Technology Policy Committee, Privacy and Security Tiger Team; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reed ME, Huang J, Brand R, et al. Communicating through a patient portal to engage family care partners. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):142-144. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolff JL, Berger A, Clarke D, et al. Patients, care partners, and shared access to the patient portal: online practices at an integrated health system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(6):1150-1158. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zulman DM, Piette JD, Jenchura EC, Asch SM, Rosland AM. Facilitating out-of-home caregiving through health information technology: survey of informal caregivers’ current practices, interests, and perceived barriers. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(7):e123. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adler-Milstein J, Raphael K, Bonner A, Pelton L, Fulmer T. Hospital adoption of electronic health record functions to support age-friendly care: results from a national survey. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27(8):1206-1213. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The age-friendly health system imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):22-24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolff JL, Darer JD, Larsen KL. Family caregivers and consumer health information technology. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):117-121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3494-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montori VM, Hargraves I, McNellis RJ, et al. The care and learn model: a practice and research model for improving healthcare quality and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):154-158. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4737-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020:487. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds TL, Ali N, Zheng K. What do patients and caregivers want? a systematic review of user suggestions to improve patient portals. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2021;2020:1070-1079. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(suppl 1):i50-i58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holden RJ, Carayon P. SEIPS 101 and seven simple SEIPS tools. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(11):901-910. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2020-012538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steitz B, Cronin RM, Davis SE, Yan E, Jackson GP. Long-term patterns of patient portal use for pediatric patients at an academic medical center. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(3):779-793. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2017-01-RA-0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semere W, Crossley S, Karter AJ, et al. Secure messaging with physicians by proxies for patients with diabetes: findings from the ECLIPPSE study. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2490-2496. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05259-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Longacre ML, Keleher C, Chwistek M, et al. Developing an integrated caregiver patient-portal system. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(2):193. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strudwick G, Booth RG, McLean D, et al. Identifying indicators of meaningful patient portal use by psychiatric populations. Inform Health Soc Care. 2020;45(4):396-409. doi: 10.1080/17538157.2020.1776291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latulipe C, Quandt SA, Melius KA, et al. Insights into older adult patient concerns around the caregiver proxy portal use: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e10524. doi: 10.2196/10524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barron J, Bedra M, Wood J, Finkelstein J. Exploring three perspectives on feasibility of a patient portal for older adults. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;202:181-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgson J, Welch M, Tucker E, Forbes T, Pye J. Utilization of EHR to improve support person engagement in health care for patients with chronic conditions. J Patient Exp. Published online February 9, 2022. doi: 10.1177/23743735221077528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson SL, Shucard H, Liao JM, et al. Care partners reading patients’ visit notes via patient portals: characteristics and perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(2):290-296. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharko M, Wilcox L, Hong MK, Ancker JS. Variability in adolescent portal privacy features: how the unique privacy needs of the adolescent patient create a complex decision-making process. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(8):1008-1017. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocy042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Seltzer A, Xiong L, Morse L, Lindquist LA. Use of electronic health records by older adults, 85 years and older, and their caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):1078-1082. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner K, Nguyen O, Hong YR, Tabriz AA, Patel K, Jim HSL. Use of electronic health record patient portal accounts among patients with smartphone-only internet access. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2118229. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crotty BH, Mostaghimi A, O’Brien J, Bajracharya A, Safran C, Landon BE. Prevalence and risk profile of unread messages to patients in a patient web portal. Appl Clin Inform. 2015;6(2):375-382. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2015-01-CR-0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis SE, Pigford M, Rich J. Improving informal caregiver engagement with a patient web portal. Electr J Health Inform. 2012;7(1):e10. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pecina J, Duvall MJ, North F. Frequency of and factors associated with care partner proxy interaction with health care teams using patient portal accounts. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(11):1368-1372. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2019.0208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Latulipe C, Gatto A, Nguyen HT, et al. Design considerations for patient portal adoption by low-income, older adults. Proc SIGCHI Conf Hum Factor Comput Syst. 2015;2015:3859-3868. doi: 10.1145/2702123.2702392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta V, Raj M, Hoodin F, Yahng L, Braun T, Choi SW. Electronic health record portal use by family caregivers of patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation: United States national survey study. JMIR Cancer. 2021;7(1):e26509. doi: 10.2196/26509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raj M, Iott B. Evaluation of family caregivers’ use of their adult care recipient’s patient portal from the 2019 Health Information National Trends Survey: secondary analysis. JMIR Aging. 2021;4(4):e29074. doi: 10.2196/29074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iott B, Raj M, Platt J, Anthony D. Family caregiver access of online medical records: findings from the Health Information National Trends Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(10):3267-3269. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06350-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Latulipe C, Mazumder SF, Wilson RKW, et al. Security and privacy risks associated with adult patient portal accounts in US hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):845-849. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Steitz BD, Wong JIS, Cobb JG, Carlson B, Smith G, Rosenbloom ST. Policies and procedures governing patient portal use at an academic medical center. JAMIA Open. 2019;2(4):479-488. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Osborn CY, Rosenbloom ST, Stenner SP, et al. MyHealthAtVanderbilt: policies and procedures governing patient portal functionality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(suppl 1):i18-i23. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weis A, Pohlmann S, Poss-Doering R, et al. Caregivers’ role in using a personal electronic health record: a qualitative study of cancer patients and caregivers in Germany. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01172-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nippak PMD, Isaac WW, Geertsen AJ, Ikeda-Douglas C. Family attitudes towards an electronic personal health record in a long term care facility. J Hosp Adm. 2015;4(3). doi: 10.5430/jha.v4n3p9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolff JL, Darer JD, Berger A, et al. Inviting patients and care partners to read doctors’ notes: OpenNotes and shared access to electronic medical records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(e1):e166-e172. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bergman DA, Brown NL, Wilson S. Teen use of a patient portal: a qualitative study of parent and teen attitudes. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2008;5:13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dickman Portz J, Powers JD, Casillas A, et al. Characteristics of patients and proxy caregivers using patient portals in the setting of serious illness and end of life. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(11):1697-1704. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tieu L, Sarkar U, Schillinger D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to online portal use among patients and caregivers in a safety net health care system: a qualitative study. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(12):e275. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chimowitz H, Gerard M, Fossa A, Bourgeois F, Bell SK. Empowering informal caregivers with health information: OpenNotes as a safety strategy. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2018;44(3):130-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mayberry LS, Kripalani S, Rothman RL, Osborn CY. Bridging the digital divide in diabetes: family support and implications for health literacy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(10):1005-1012. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Antonio MG, Petrovskaya O, Lau F. Is research on patient portals attuned to health equity? a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):871-883. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Freedman VA, Patterson SE, Cornman JC, Wolff JL. A day in the life of caregivers to older adults with and without dementia: comparisons of care time and emotional health. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(9):1650-1661. doi: 10.1002/alz.12550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Wolff JL. The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1642-1649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):126-137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.P126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ip W, Yang S, Parker J, et al. Assessment of prevalence of adolescent patient portal account access by guardians. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2124733. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bute JJ, Petronio S, Torke AM. Surrogate decision makers and proxy ownership: challenges of privacy management in health care decision making. Health Commun. 2015;30(8):799-809. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.900528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.DesRoches CM, Walker J, Delbanco T. Care partners and patient portals—faulty access, threats to privacy, and ample opportunity. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):850-851. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh S, Polavarapu M, Arsene C. Changes in patient portal adoption due to the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic. Inform Health Soc Care. 2022:1-14. doi: 10.1080/17538157.2022.2070069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang M, Khurana A, Mastorakos G, et al. Patient portal messaging for asynchronous virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective analysis. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(2):e35187. doi: 10.2196/35187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lyles CR, Nelson EC, Frampton S, Dykes PC, Cemballi AG, Sarkar U. Using electronic health record portals to improve patient engagement: research priorities and best practices. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(11)(suppl):S123-S129. doi: 10.7326/M19-0876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.US Government Accountability Office . Health information technology: HHS should assess the effectiveness of its efforts to enhance patient access to and use of electronic health information. March 15, 2017. Accessed August 1, 2022. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-305

- 78.Johnson CRC, Patel V. Individuals’ Access and Use of Patient Portals and Smartphone Health Apps, 2020. ONC Data Brief. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Horwitz LI, Kuznetsova M, Jones SA. Creating a learning health system through rapid-cycle, randomized testing. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1175-1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1900856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: from concept to action. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(3):207-210. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tuzzio L, Hanson LR, Reuben DB, et al. Transforming dementia care through pragmatic clinical trials embedded in learning healthcare systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(suppl 2):S43-S48. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Borson S, Chodosh J. Developing dementia-capable health care systems: a 12-step program. Clin Geriatr Med. 2014;30(3):395-420. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Data Extraction Table

eTable 3. Detailed Characteristics of Studies Included in Scoping Review

eTable 4. Consequences of Care Partner Use of the Patient Portal by the Otte-Trojel Framework

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement