Abstract

The agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is an obligate intracellular bacterium with a tropism for neutrophils; however, the mechanisms of bacterial dissemination are not yet understood. Interleukin-8 (IL-8) is a chemokine that induces neutrophil migration to sites of infection for host defense against pathogens. We now show that HGE bacteria, and the HGE-44 protein, induce IL-8 secretion in a promyelocytic (HL-60) cell line that has been differentiated along the neutrophil lineage with retinoic acid and in neutrophils. Infected HL-60 cells also demonstrate upregulation of CXCR2, an IL-8 receptor, but not CXCR1. Human neutrophils migrate towards Ehrlichia sp.-infected cells in a chemotaxis chamber assay, and this movement can be blocked with antibodies to IL-8. Finally, immunocompetent and severe combined immunodeficient mice administered CXCR2 antisera, and CXCR2−/− mice that lack the human IL-8 receptor homologue, are much less susceptible to granulocytic ehrlichiosis than are control animals. These results demonstrate that HGE bacteria induce IL-8 production by host cells and, paradoxically, appear to exploit this chemokine to enhance infection.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is a tick-borne infectious disease that is becoming increasingly recognized in North America and Europe (7, 15, 24, 47). The HGE agent preferentially persists within host neutrophils and often causes an acute febrile illness with headache, myalgia, and cytopenias, among other symptoms (57). Although the disease is generally self-limiting, severe complications and fatalities have been reported elsewhere (1, 3, 21, 27). The HGE bacterium is closely related, if not identical, to Ehrlichia equi and Ehrlichia phagocytophila, agents of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in horses and sheep, and a workshop group has recently suggested that these organisms should be renamed Anaplasma phagocytophila, based on taxonomic considerations (J. S. Dumler, Y. Rikihisa, G. A. Daesch, A. F. Barbet, G. M. Palmer, and S. C. Ray, Am. Soc. Rickettsiol. 15th Sesquiannu. Meet. Abstr. Book, p. 52, 2000). For clarity, this pathogen will be referred to as the HGE agent or simply Ehrlichia sp. throughout this text.

Propagation of the HGE agent in a promyelocytic (HL-60) tumor cell line (6, 18, 32) and a murine model of granulocytic ehrlichiosis (8, 23) have increased our understanding of Ehrlichia pathogenesis. The tropism of Ehrlichia sp. for neutrophils can be partially explained by the use of sialylated Lewis X (CD15s) (19) and the leukocyte P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 to attach to and invade polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) (22). The persistence of Ehrlichia sp. within membrane-bound morulae that do not fuse with lysosomes (42, 58) and the ehrlichial suppression of the respiratory burst (43) by downregulating gp91phox (5) then facilitate intracellular survival. Immunocompetent, but not severe combined immunodeficient (SCID), mice generally clear Ehrlichia sp. after several weeks, and Ehrlichia antisera or antibodies to the P44 (or HGE-44) family of proteins afford partial immunity (29, 49), demonstrating that the host response alters the course of infection. Furthermore, gamma interferon production during early murine infection also helps control the levels of HGE bacteria (2, 37). Despite these advances, the mechanisms that Ehrlichia sp. uses to attract and transfer between neutrophils in vivo are not yet known.

Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines that are classified according to their molecular structures. Interleukin-8 (IL-8) is a potent neutrophil attractant and a member of the α-chemokine (CXC chemokine) family (35). Human neutrophils respond to IL-8 through CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors. In addition to IL-8, other CXC chemokines, including growth-related oncogene α (GRO-α), neutrophil-activating peptide 2 (NAP-2), epithelial-cell-derived activating peptide 78 (ENA-78), and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor 2 (GCP-2), bind to CXCR2. Only IL-8 and GCP-2 bind CXCR1 (35). Murine homologues of human IL-8 have not yet been identified; however, mice possess a receptor that resembles human CXCR2 and that mediates neutrophil chemotaxis by binding to chemokine KC or macrophage-inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) (9). Bacteria have been shown previously to induce IL-8 from host cells, and this can be associated with the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1α, IL-1β, or IL-17 (13, 17, 34, 53). The importance of IL-8 in HGE infection is, however, not known. One report recently showed that infection of HL-60 cells or human bone marrow cells with the HGE agent induced IL-8 but not proinflammatory cytokines (31). In contrast, others have demonstrated that ehrlichial infection of human neutrophils induces IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 without an increase in IL-8 (30). Finally, in vivo studies have shown that the HGE agent does not affect TNF-α and IL-1β levels in mice or humans (37, 52).

The migration of neutrophils to the site of infection is an important first-line defense against bacteria, resulting in phagocytosis and microbial eradication. Nevertheless, neutrophil-specific receptor-mediated adhesion (19, 22), lysosomal evasion (32, 58), and NADPH oxidase repression (5, 43) help the HGE agent to invade and persist within cells. Therefore, recruitment of neutrophils to the location of Ehrlichia infection may paradoxically facilitate dissemination, rather than elimination, of this bacterium. We have now investigated the influence of the HGE agent on host cell IL-8 secretion and its role in Ehrlichia pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation of the HGE agent.

The HGE isolate NCH-1 (50) was cultured in HL-60 cells (240-CCL; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) at 37°C with 5% CO2. To induce neutrophilic differentiation, HL-60 cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were incubated with 1 μM retinoic acid for 4 days. Differentiated HL-60 cells were designated rHL-60 cells. Infection of rHL-60 cells was effected by adding 105 Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells (over 75% of the cells were infected with the HGE agent) to rHL-60 cells.

SCID mice develop a persistent infection with the HGE agent, and blood from these animals can also be used to uniformly infect naive mice (2). One hundred microliters of blood from Ehrlichia sp.-infected SCID mice was therefore used to challenge inbred immunocompetent BALB/c, C3H-scid, or IL-8 receptor-deficient (CXCR2−/−) mice with the HGE agent. C3H-scid mice were obtained from the Frederick Cancer Research Center (Frederick, Md.) and initially challenged with Ehrlichia sp. by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 100 μl of Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells. Blood from infected SCID mice with morulae in 8% of the peripheral neutrophils was then used for infection—instead of infected HL-60 cell culture—to avoid the possible antigenic influence of human cells introduced into the mice.

In vitro infection of human neutrophils and mouse splenocytes with Ehrlichia sp.

Human neutrophils were isolated from 10 ml of fresh human blood drawn in tubes containing 0.25 ml of anticoagulant (1,000 U of heparin/ml). Blood was mixed with 3% dextran at a 1:3 (blood-to-dextran) ratio and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatant containing PMNs was collected and centrifuged at 750 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The supernatant was then discarded, and 5 ml of Kreb's-Ringer's phosphate-buffered solution with glucose was added in resuspending the cells. Residual red blood cells were removed by hypotonic lysis and centrifugation at 4°C. After three washings with Kreb's-Ringer's phosphate-buffered solution with glucose, 2 × 106 cells/ml were incubated with isolated Ehrlichia sp. Splenocytes isolated from uninfected BALB/c mice were washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution (Gibco BRL) containing 10% FCS and suspended at 6 × 106 cells/ml in six-well culture plates (Corning, Corning, N.Y.). Ehrlichias were isolated from 10 ml of infected HL-60 cells (106 cells/ml) that were mechanically lysed by multiple passages through a 25½-gauge needle. Ten milliliters of uninfected HL-60 cells (106 cells/ml) was treated the same way to obtain HL-60 cell products that would be used as controls. Disrupted HL-60 cell suspensions were centrifuged at 750 × g for 10 min to spin down unbroken HL-60 cells. Free ehrlichias were collected by centrifuging the supernatants at 2,300 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Free ehrlichias were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and washed twice before resuspending the pellets in 4 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 10% FCS. Ehrlichias were added to 2 × 106 human PMNs or 6 × 106 mouse splenocytes suspended in 1 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution (Gibco BRL) containing 10% FCS. Ehrlichias were incubated with human PMNs or mouse splenocytes in six-well culture flasks for up to 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Measurement of culture supernatant and chemokines and cytokines in serum.

Culture supernatant and serum or peritoneal lavage cytokine and chemokine levels were measured using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Biotin-labeled and unlabeled goat antibodies against human GRO-α, IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-17 and mouse KC and MIP-2 were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.) and R&D Laboratories (Minneapolis, Minn.). Recombinant human GRO-α, IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, NAP-2, ENA-78, IL-17, and GCP-2 and mouse KC and MIP-2 were used to plot a standard curve for each cytokine or chemokine. Antibody-coated ELISA plates were blocked with 200 μl of 1.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS (blocking buffer) for 2 h at room temperature. Serially diluted culture supernatants or sera were applied to the wells and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. Known concentrations of recombinant cytokines or chemokines were also included to develop standard curves for ELISA. Wells were washed with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS before adding 100 μl of biotinylated antibodies, diluted 1:4,000, in blocking buffer. Following incubation for 45 min at room temperature, 1:1,000-diluted peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) was used to detect bound antibodies. Peroxidase developing solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used to induce the chromogenic reaction of peroxidase, and the resulting absorbency was read at 450 nm following the addition of stop solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Human serum samples.

Stored human sera, collected from patients with HGE during an active surveillance study designed to assess the incidence of HGE in a 12-town area in Connecticut (24), were used to examine IL-8 levels during ehrlichiosis. Sera were obtained from patients with confirmed cases of HGE in which the patients had fevers, headache, and/or myalgia and were PCR positive for Ehrlichia sp. Control sera were from healthy volunteers and from individuals in the surveillance study with fever and/or myalgia but without serologic or PCR evidence of HGE. Detection of IL-8 was performed in an ELISA as described above.

Determination of IL-8 mRNA in rHL-60 cells.

Ehrlichia sp.-infected and uninfected rHL-60 cells were harvested, and total RNA was extracted by using the Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) RNA isolation kit. The ProSTAR first-strand reverse transcription-PCR kit (Stratagene) was used to reverse transcribe 5 μg of RNA in a 50-μl reaction mixture. IL-8-specific primers 5′-ATG ACT TCC AAG CTG GCC GTG GCT-3′ and 5′-TCT CAG CCT TCT TCA AAA ACT TCT C-3′ were used to amplify IL-8 cDNA. Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) primers were used to assess and normalize the cDNA concentrations among samples from Ehrlichia sp.-infected and uninfected HL-60 cells.

Measurement of IL-8 receptor expression.

The levels of infected and uninfected HL-60 cell IL-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 were analyzed by flow cytometry. Retinoic acid-treated HL-60 cells (rHL-60 cells; 6 × 106) were incubated for 5 days with 6 × 105 infected HL-60 cells. Fluorescein-conjugated monoclonal antibody to human CXCR1 (Pharmingen) and R-phycoerythrin-conjugated CXCR2 (Pharmingen) were incubated with 106 Ehrlichia sp.-infected or uninfected control rHL-60 cells suspended in 10% FCS in PBS. Biotin-labeled mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2b antibodies (Pharmingen) were used as isotype-specific control immunoglobulins. Surface-bound antibodies were detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

Neutrophil chemotaxis assay.

Freshly isolated PMNs (2.4 × 106) suspended in 50 μl of Hanks' balanced salt solution (Gibco) were added to the upper compartment of a 96-well ChemoTx System chemotaxis chamber (Neuro Probe, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.). Three hundred microliters of culture supernatants or recombinant IL-8 (Pharmingen), at 350 ng/ml, was added to the lower compartment. Ehrlichia sp.-infected cell culture supernatant contained 276 ng of IL-8/ml, and uninfected HL-60 cell culture supernatant contained 12 ng of IL-8/ml. After 30 min of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, cells that did not migrate were rinsed from the upper compartment of a 3-μm-pore-size filter. Cells attached under the filter were released by washing the filters with PBS containing 2 mM EDTA and by centrifugation. The migrated live cells in the wells were quantified by reading the absorbency at 490 nm following the addition of 20 μl of CellTiter 96 AQueus assay reagent (Promega, Madison, Wis.). To assess the role of IL-8 in the induction of chemotaxis, neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to human IL-8 (R&D Laboratories) were added to the lower compartment of the chamber at a concentration of 20 μg/ml. Uninfected pooled murine sera were used as negative controls. Control wells containing serially diluted cells were also treated with 20 μl of CellTiter 96 AQueus assay reagent to obtain a standard curve of optical density readings. The optical density values of the samples were expressed relative to the standard curve values, yielding an index of cells that migrated across the membrane.

Infection of mice with the HGE agent.

Both the BALB/c mice and IL-8 receptor (CXCR2−/−) knockout mice (BALB/c-Cmkar2tm1Mwm) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine). C3H-scid mice were purchased from the Frederick Cancer Research Center. HGE was induced in three BALB/c and three CXCR2−/− mice by i.p. injection of 100 μl of ehrlichia-containing blood from donor SCID mice (2). EDTA-treated peripheral blood and sera were collected from each mouse on days 2, 7, 15, and 30. Bacterial infection was assessed by determining the percentage of ehrlichia-containing (morulae) cells among at least 200 granulocytes examined in each peripheral blood smear. Slides were stained with Diff-Quick (Baxter Healthcare Corp., Miami, Fla.) and examined for morulae by light microscopy. The donor mice had morulae in 8% of the peripheral neutrophils. All mice were maintained in barrier-filtered cages, received a standard laboratory diet, and were given water ad libitum.

One hundred microliters of peripheral blood collected in anticoagulant (1 mM EDTA) was incubated twice with 900 μl of erythrocyte lysis buffer (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 1 mM EDTA) prior to extraction of blood DNA. Cells deprived of erythrocytes were suspended in 200 μl of PBS, pH 7.2, and DNA was extracted with the QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification of HGE agent DNA was done by using 16S ribosomal DNA primers detecting the bp 497 to 521 (5′-TGT AGG CGG CGG TTC GGT AAG TTA AAG-3′) and bp 747 to 727 (5′-GCA CTC ATC GTT TAC AGC GTG-3′) regions. Pooled DNA samples were subjected to PCR amplification using HPRT primers, and DNA from each group was equalized prior to Ehrlichia PCR amplification. Blood Ehrlichia DNA was also assessed by using a quantitative competitive PCR method as described previously (2). Briefly, predetermined increasing amounts of a competitor DNA fragment with external Ehrlichia primers were mixed with a series of tubes containing a constant amount of target mouse blood DNA in a 50-μl PCR mixture. Specific primers for Ehrlichia 16S ribosomal DNA were added to the reaction mix, and the DNA was allowed to compete with the competitor DNA for the primers in a thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc., Waltham, Mass.). Amplified products were run on a 2% agarose gel, and ethidium bromide-stained gels were analyzed for the PCR band intensity where the competitor and Ehrlichia DNA molecules were equivalent. At this point, the Ehrlichia DNA concentration was considered equal to the competitor DNA concentration since they both competed for the same primers. Experiments were repeated at least twice.

The effect of in vivo inhibition of CXCR2 on Ehrlichia infection was investigated by using neutralizing antisera to murine CXCR2 (a kind gift of R. Strieter, UCLA School of Medicine). Normal goat serum (NGS) (Sigma Biochemicals) was used as a control antibody. The effect of CXCR2 antisera was tested with BALB/c mice and C3H-scid mice. BALB/c mice were used because this is the strain on which the CXCR2−/− mice were generated. C3H-scid mice were assessed because infection with the HGE agent has been extensively studied with these animals, and the scid mutation results in a more severe infection (2, 23, 49). Groups of three mice were injected i.p. with 500 μl of CXCR2 antisera or NGS 2 h prior to challenge with ehrlichia-containing SCID mouse blood. Mice were injected with the same amount of antisera two more times, on days 2 and 4 of infection. On day 7, blood samples of control and test animals were analyzed for Ehrlichia burden by PCR and for the percentage of peripheral neutrophils with morulae.

The effect of CXCR2 antiserum on mice that had been previously infected with Ehrlichia sp. was also explored. Eight mice were inoculated with ehrlichias as described above. The level of infection was determined 10 days after bacterial challenge by counting the peripheral neutrophils with morulae. Four mice were then injected (i.p.) with 500 μl of CXCR2 antisera four times at 36-h intervals. The remaining four mice (controls) received the same amount of NGS. Ehrlichia infections were compared before and after treatment with CXCR2 antisera.

Analysis of neutrophil chemoattraction to the site of Ehrlichia inoculation.

To explore the in vivo effect of Ehrlichia sp. on the chemoattraction of neutrophils, three BALB/c mice were i.p. infected with Ehrlichia sp. as described above. Four hours after bacterial challenge, mice were euthanatized with CO2 inhalation and the peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage. Three milliliters of sterile PBS was injected into the peritoneal cavity. The injected fluid was dispersed throughout the cavity and was recovered using a syringe. Lavage fluids from three animals were pooled, and cells were collected by centrifugation at 300 × g. Supernatant KC and MIP-2 levels were determined in an ELISA. The number of neutrophils in the lavage material was assessed by flow cytometry by using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-Gr-1 antibodies (Pharmingen). Flow cytometry was performed as described above. Background peritoneal neutrophil counts were done with three naive mice that did not receive an Ehrlichia inoculum. To address the role of CXCR2 in Ehrlichia sp.-induced in vivo neutrophil migration, groups of three mice were administered (i.p.) 500 μl of CXCR2 antisera or NGS 2 h before bacterial challenge. Four hours later, peritoneal neutrophil counts were performed as described above. Experiments were repeated at least twice.

Measurement of antibodies against Ehrlichia antigens.

IgG antibodies to Ehrlichia sp. were measured by ELISA in Ehrlichia sp.-challenged CXCR2−/− and wild-type BALB/c mice. Ehrlichia bacteria were purified from HL-60 cells as described above and kept at −20°C until use in ELISA. Wells were coated with 100 ng of ehrlichias/well and blocked with 1.5% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Serially diluted serum samples were added to wells and incubated for 4 h. Wells were washed with washing buffer, and peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Sigma) diluted 1:4,000 in 0.05% Tween 20-containing blocking buffer were added. After 1 h of incubation and washing, the chromogenic reaction was induced by adding peroxidase developing solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). The reaction was terminated using stop solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories), and the absorbency was read at 450 nm.

Statistical methods.

Data are presented as the means ± standard errors. In figures where the results of two experiments are shown, at least three replicates were included in each experiment. Comparisons between the means of controls and those of infected replicates were made by the two-sample Student t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

IL-8 secretion and IL-8 mRNA expression by Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells.

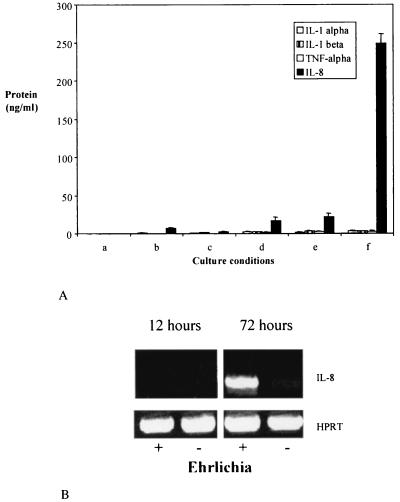

IL-8 is a potent chemokine that induces neutrophil chemotaxis and could play a role in enabling Ehrlichia sp. to maintain infection in PMNs or in their precursors. We examined the effect of Ehrlichia sp. on the induction of IL-8 in undifferentiated HL-60 cells and HL-60 cells that had been terminally differentiated along the neutrophil lineage with retinoic acid. Levels of TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β were also examined, since these proinflammatory cytokines may induce IL-8 secretion (14, 38). IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β were not detectable in culture supernatants of undifferentiated control HL-60 cells or Ehrlichia sp.-infected undifferentiated HL-60 cells at 6 days (Fig. 1A, columns a and b). Furthermore, uninfected (control) or infected HL-60 cells that were differentiated with retinoic acid did not have statistically different levels (P > 0.05) of these molecules (Fig. 1A, columns c and d). The interaction of Ehrlichia sp. with molecules that are expressed after treatment of HL-60 cells with retinoic acid may be important in secretion of cytokines and chemokines. Therefore, experiments were performed in which HL-60 cells were first differentiated with retinoic acid (rHL-60) and then incubated with HL-60 cells alone (control) or ehrlichia-containing HL-60 cells (Fig. 1A, columns e and f). In contrast to the previous results, HGE bacteria induced high levels of IL-8 (P < 0.0001) in rHL-60 cells (Fig. 1A, column f). TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β were not detected.

FIG. 1.

IL-8 and inflammatory cytokine secretion by HL-60 cells in response to Ehrlichia sp. (A) In columns a to d, 2 × 106 undifferentiated HL-60 cells were given 105 HL-60 cells (control) (a and c) or 105 Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells (b and d). In columns c and d, the cells were subsequently treated with retinoic acid. In columns e and f, 2 × 106 HL-60 cells were first treated with retinoic acid (rHL-60) and then administered 105 uninfected HL-60 cells (e) or Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells (f). In each case, 6 days after the additions, culture supernatants were assayed for IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α. The means ± standard errors of triplicate samples are presented. Results from one of two similar experiments are shown. (B) IL-8 mRNA expression was determined at 12 and 72 h after exposure of 2 × 106 rHL-60 cells to 105 Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells (+). rHL-60 cells (2 × 106) exposed to 105 HL-60 cells served as a control (−). All samples demonstrated equivalent levels of HPRT mRNA (control). Results from one of three representative studies are shown.

IL-8 mRNA was then examined in Ehrlichia sp.-infected and uninfected rHL-60 cells to further explore the increased IL-8 levels. Reverse transcription-PCR was performed, and mRNA was measured at 12 and 72 h after the addition of 105 infected or uninfected HL-60 cells to 2 × 106 rHL-60 cells. At 72 h, Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 cells had strong expression of IL-8 mRNA, while uninfected rHL-60 cells manifested a faint band that can barely be seen on the gel (Fig. 1B).

Kinetics of IL-8 secretion from Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 cells.

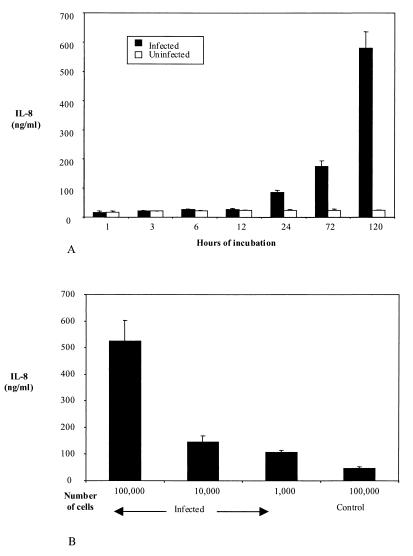

In order to determine the kinetics of Ehrlichia sp.-induced IL-8 secretion from rHL-60 cells, culture supernatants were collected at seven time points (1 to 120 h) after the addition of Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells to rHL-60 cells. A significant increase in IL-8 concentration was detected 24 h after addition of the HGE agent (P < 0.01), compared to the concentration at 12 h. IL-8 levels then continued to increase until the last time point tested, 120 h (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Kinetics of IL-8 secretion from Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 cells and the effect of the amount of ehrlichias on IL-8 secretion. (A) IL-8 levels were measured until 5 days after the addition of 105 Ehrlichia sp.-infected or uninfected (control) HL-60 cells to 2 × 106 rHL-60 cells. The means ± standard errors of three experiments are shown. (B) Culture supernatant IL-8 levels after the addition of 105, 104, or 103 Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells or 105 uninfected (control) HL-60 cells to rHL-60 cells. The means ± standard errors of three experiments are shown.

We then assessed the influence of the Ehrlichia inoculum size on the induction of IL-8 from rHL-60 cells. Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells (103, 104, or 105) were added to 2 × 106 rHL-60 cells. The secretion of IL-8 was dependent on the relative amount of HGE bacteria. rHL-60 cells inoculated with 105 Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells had much higher levels of IL-8 (523 ng/ml) than did rHL-60 cells inoculated with 104 (146 ng/ml) or 103 (105 ng/ml) Ehrlichia sp.-infected HL-60 cells (Fig. 2B). All these values were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those in control studies in which rHL-60 cells were exposed to uninfected (control) HL-60 cells (46.5 ng/ml).

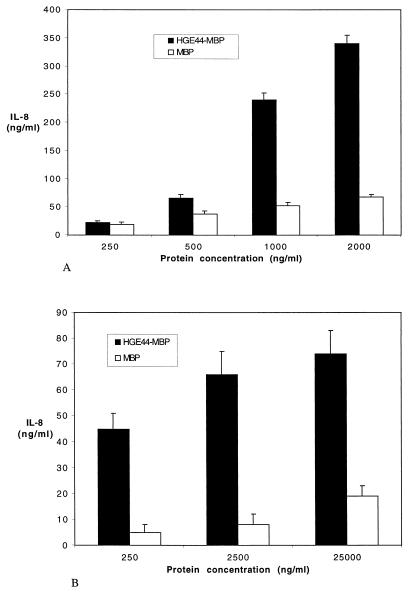

Induction of IL-8 from rHL-60 cells and neutrophils by HGE-44, a major 44-kDa antigen on the HGE agent.

A group of genes designated the HGE-44 (or P44) gene family encode a large number of proteins that elicit prominent immune responses during early infection (25, 45, 61, 62). HGE-44 and P44 are individual proteins that are expressed by members of this gene cluster (25, 61, 62). These antigens may play roles in immunity and pathogenesis because monoclonal antibodies to P44 partially protect mice from infection (29), and electron microscopy demonstrates that these antibodies bind the surface of morulae (29). The HGE-44 antigen has been expressed and purified elsewhere as a recombinant fusion protein with maltose-binding protein (MBP) (26). In order to assess the role of HGE-44 in IL-8 secretion, increasing concentrations of HGE-44–MBP fusion protein were incubated with rHL-60 cells or human neutrophils. As a control, rHL-60 cells were exposed to recombinant MBP that had been made in the identical fashion as the HGE-44–MBP protein. After 5 days of incubation, culture supernatants of rHL-60 cells containing HGE-44–MBP had a dose-dependent induction of IL-8 that was markedly higher at 500 (P < 0.01), 1,000 (P < 0.001), and 2,000 (P < 0.0001) ng/ml than that of rHL-60 cells incubated with MBP (Fig. 3A). IL-8 secretion by human PMNs was determined after 12 h of incubation with HGE-44–MBP or MBP (control) alone. Neutrophils that were incubated with HGE-44–MBP secreted higher levels (P < 0.02) of IL-8 than did controls (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

The effect of HGE-44 on the induction of IL-8 from rHL-60 cells and PMNs. (A) rHL-60 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of HGE-44–MBP fusion protein or MBP (control), and culture supernatant IL-8 levels were measured 5 days later. The molar ratio of HGE-44 to MBP in HGE-44–MBP fusion protein is approximately 2:3. Results from one of two experiments with similar results are shown as means ± standard errors. (B) PMNs were incubated with increasing concentrations of HGE-44–MBP fusion protein or MBP (control), and culture supernatant IL-8 levels were measured 24 h later. The results of three independent experiments are expressed as means ± standard errors.

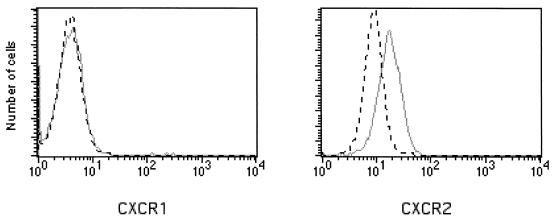

IL-8 receptor CXCR2 expression in Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 cells.

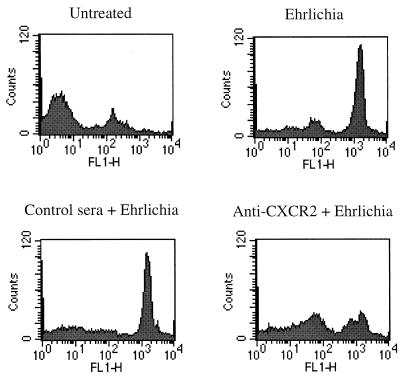

Levels of the cell surface IL-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 were then examined by flow cytometry to determine whether infection with HGE bacteria alters receptor expression. rHL-60 cells incubated with Ehrlichia sp.-infected cells or control cells were analyzed 5 days after the onset of infection. The expression of CXCR2 was upregulated in cultures containing Ehrlichia sp. compared to that of uninfected rHL-60 cells. In contrast, CXCR1 expression was not affected. Results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 4. Since CXCR2 is a receptor for other ligands such as GRO-α, NAP-2, ENA-78, and GCP-2 (10, 36), we determined the levels of these molecules in the culture supernatants of Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 cells and found that they were not increased (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Flow cytometric analysis of IL-8 receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 on rHL-60 cells. rHL-60 cells (106) that were infected with Ehrlichia sp. (solid gray line) or incubated with HL-60 cells (black dashed line) were analyzed for surface expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2. Results of one of three representative experiments are shown.

Induction of IL-8 secretion from Ehrlichia sp.-infected human neutrophils.

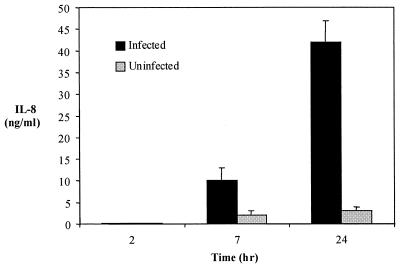

Studies with ehrlichias and human neutrophils were then performed to extend our observations beyond HL-60 cells. Incubation of isolated ehrlichias with human PMNs resulted in the induction of IL-8 secretion. By 7 and 24 h, IL-8 levels increased to 10.5 and 40 ng/ml, respectively (Fig. 5), in the infected PMN cultures, which were higher at both time points (P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001, respectively) than were controls. None of the other cytokines and chemokines tested, including IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17, GRO-α, NAP-2, ENA-78, and GCP-2, increased after Ehrlichia infection (data not shown). Culture supernatant IL-8 levels were not measured after 24 h, as the viability of PMNs diminished significantly after this time point.

FIG. 5.

IL-8 secretion by human neutrophils in response to the HGE agent. IL-8 levels were measured at 2, 7, and 24 h following infection of human PMNs with isolated ehrlichias. The means ± standard errors of three studies are shown.

Chemotactic activity of culture supernatants from Ehrlichia sp.-infected cells.

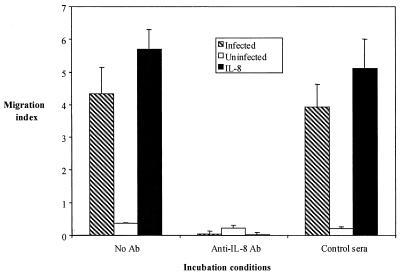

The functional effect of IL-8 induction by the HGE agent was examined using a chemotaxis assay to help determine its role in Ehrlichia pathogenesis. Freshly isolated human neutrophils were incubated with culture supernatants from Ehrlichia sp.-infected or uninfected (control) rHL-60 cells. Recombinant IL-8 served as the positive control. The effect of the Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 culture supernatants on the migration of neutrophils was comparable to that of recombinant (350 μg/ml) IL-8 (P < 0.001, compared with no antibody) (Fig. 6). In contrast, uninfected rHL-60 cell culture supernatant did not induce chemotaxis (Fig. 6). In order to assess the contribution of Ehrlichia sp.-induced IL-8 to neutrophil migration, we then performed blocking experiments using neutralizing antibodies against IL-8. Twenty micrograms of IL-8 antibody per milliliter prevented the neutrophil migration induced by Ehrlichia sp.-infected cell culture supernatant or recombinant IL-8 (control), indicating that IL-8 was the major contributor to the chemotaxis induced by the HGE agent (P <0.001). Sera from normal mice had no effect.

FIG. 6.

Measurement of chemotaxis-induced Ehrlichia sp.-infected rHL-60 cell culture supernatants and the effect of neutralizing antibodies to IL-8 on chemotaxis. Culture supernatants from infected and uninfected rHL-60 cells were used as chemoattractants in 96-well Neuro Probe TX chambers together with recombinant IL-8 (20 μg/ml) as a positive control and medium as a negative control. In other wells, mouse anti-human IL-8 monoclonal antibodies or normal murine sera (negative control) were added to culture supernatants to determine the effect of neutralizing antibodies to IL-8 on chemotaxis. Migrated cells were determined by optical density reading after the addition of a tetrazolium compound as a color development reagent. Readings recorded with medium alone were considered as background, and the migration index was calculated after the subtraction of background values. The means ± standard errors of three independent studies are shown. Ab, antibody.

Ehrlichia sp. induces neutrophil chemotactic molecules in mice.

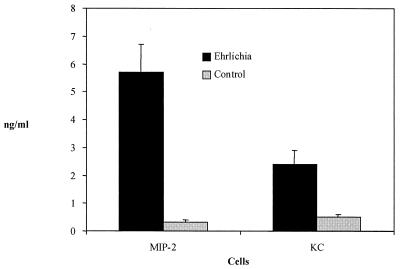

Although mice have a homologue of the human CXCR2 receptor, the murine equivalent of IL-8 has not yet been identified. Nevertheless, murine MIP-2 and KC have been shown to bind CXCR2 and facilitate neutrophil chemotaxis. Therefore, the ability of Ehrlichia sp. to stimulate these molecules was assessed. Splenocytes from BALB/c mice were incubated with free ehrlichias. After 24 h of incubation, culture supernatants of infected mouse splenocytes contained significantly higher amounts of MIP-2 (P < 0.001) and KC (P < 0.002) (Fig. 7) than did controls. These experiments demonstrate that, following Ehrlichia infection, mice secrete high levels of neutrophil chemotactic molecules that are known to bind CXCR2.

FIG. 7.

Levels of the murine neutrophil chemokines, MIP-2 and KC, from splenocytes exposed to Ehrlichia sp. Splenocytes from BALB/c mice were incubated for 24 h with free ehrlichias that were extracted from infected HL-60 cells or supernatants from uninfected HL-60 cells that were treated in an identical fashion (control). The means ± standard errors of three studies are shown.

HGE infection in CXCR2−/− mice and mice treated with CXCR2 antiserum.

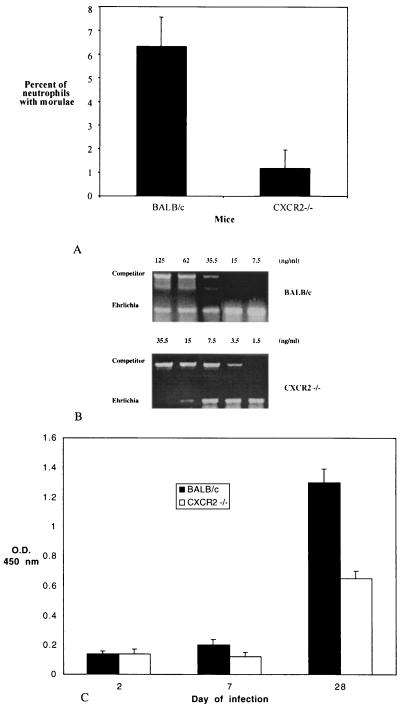

To explore the importance of CXCR2-induced migration of neutrophils for granulocytic ehrlichiosis, we infected CXCR2−/− mice generated on a BALB/c background and wild-type BALB/c mice (controls) with the HGE agent. Control mice manifested infection kinetics similar to those of C3H and B6 mice that have been reported earlier (2, 23, 49). The bloodstream infection peaked at approximately 1 week and cleared by 3 weeks. Ehrlichia infection was markedly diminished in the CXCR2−/− mice. All three CXCR2−/− mice had lower numbers of infected neutrophils than did the control mice at the peak of infection (day 7). On day 7, the percentages of neutrophils with morulae were 4.5, 8, and 6.5 in the three BALB/c mice and 2, 0, and 1.5 in the three CXCR2−/− mice. The mean number of morulae in the three CXCR2−/− mice was significantly lower (P < 0.01) than that in the wild-type BALB/c mice (Fig. 8A). The difference in the morulae counts between the two groups of mice was also reflected in the blood Ehrlichia DNA profiles. On day 7, representing the peak infection, the Ehrlichia DNA concentration in pooled DNA from the BALB/c mice was higher than that in the CXCR2−/− mice (Fig. 8B). In accordance with the decreased bacterial load in CXCR2−/− mice, a serum ELISA performed on day 28 showed that CXCR2−/− mice also had significantly (P < 0.002) lower levels of mean serum IgG antibodies to Ehrlichia sp. than did BALB/c mice (Fig. 8C).

FIG. 8.

Ehrlichiosis in CXCR2−/− mice. (A) Groups of three mice were infected with the HGE agent, and the percentage of peripheral neutrophils with morulae containing ehrlichias was assessed. (B) DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of Ehrlichia sp.-infected CXCR2−/− and BALB/c mice (n = 3). In the representative experiment shown, Ehrlichia DNA was quantified using a competitive PCR construct. As a control, HPRT DNA was amplified in all cases. (C) Anti-Ehrlichia sp. IgG antibody levels in CXCR2−/− and BALB/c mice. The means ± standard errors of two groups of three mice are shown.

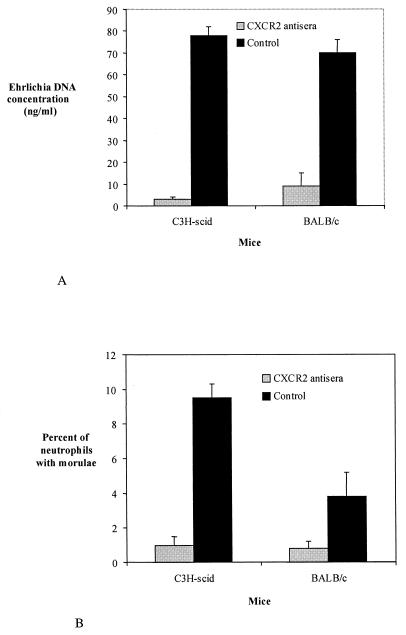

To extend these observations, BALB/c mice and C3H-scid mice were administered CXCR2 antisera and then challenged with Ehrlichia sp. BALB/c mice were used because they represent the same background that was used to generate the CXCR2−/− mice. C3H-scid mice were used because these animals have previously been shown to develop a persistent infection with the HGE agent (23). BALB/c and C3H-scid mice that received CXCR2 antisera had significantly lower levels of Ehrlichia infection than did mice that were given control antiserum (NGS). On day 7, the mean Ehrlichia DNA concentration in CXCR2 antiserum-treated BALB/c mice was 8.7 ng/ml while control BALB/c mice had 71 ng/ml (P < 0.015) (Fig. 9A). On the same day, the mean Ehrlichia DNA concentration of three CXCR2 antiserum-treated C3H-scid mice was 3 ng/ml compared to 76 ng/ml for the three control C3H-scid mice (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the mean percentage of neutrophils with morulae was lower (P < 0.025) in CXCR2 antiserum-treated BALB/c mice (0.6%) than it was in controls (3.6%) (Fig. 9B). Similarly, CXCR antiserum-treated C3H-scid mice also had fewer morulae than did control animals (P < 0.02). In vivo treatment of mice with CXCR2 antisera did not result in a significant change in the systemic neutrophil count (data not shown).

FIG. 9.

Ehrlichia DNA concentrations in BALB/c and C3H-scid mice that were administered CXCR2 antisera. Control mice were given NGS. DNA levels were measured on day 7, the peak of infection. (A) Mouse blood DNA was quantified by quantitative PCR using a competitor construct, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) The mean percentage of peripheral neutrophils with ehrlichia-containing morulae is seen in mice administered CXCR2 antisera or control. The means ± standard errors obtained for three mice in each group are shown. Results of one of two representative experiments are presented.

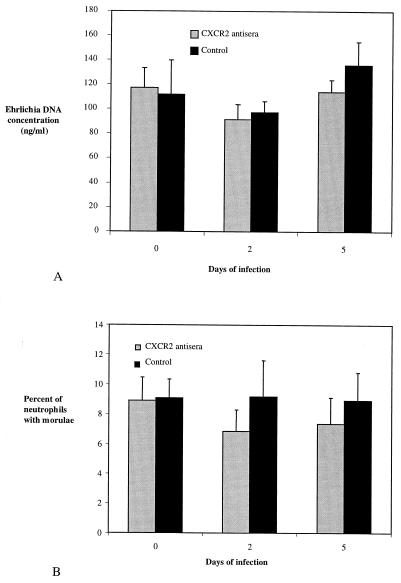

We next explored whether the inhibition of neutrophil migration following (rather than prior to) challenge with Ehrlichia sp. would alter infection. For this purpose, eight C3H-scid mice were i.p. infected with Ehrlichia sp., and 10 days later, groups of four mice were given three doses of CXCR2 antiserum or control serum (NGS) every 36 h. The level of infection was monitored by determining the number of neutrophils with morulae and PCR amplification of blood Ehrlichia DNA, before and after injections of antisera. In contrast to CXCR2−/− mice or mice that received CXCR2 antisera prior to Ehrlichia challenge, administration of CXCR2 antisera to previously infected mice did not modify the level of infection. The mean percentages of neutrophils containing morulae on days 0, 2, and 5 after antiserum administration were 8.8, 6.8 (P = 0.1 compared to day 0), and 7.3 (P = 0.2 compared to day 0), respectively (Fig. 10A). The mean blood Ehrlichia DNA concentration values for the same days were 117, 91.3 (P = 0.1 compared to day 0), and 114 (P = 0.4 compared to day 0) ng/ml, respectively (Fig. 10B). As expected, control sera did not affect the level of infection.

FIG. 10.

The effect of CXCR2 antisera on HGE infection in C3H-scid mice previously infected with Ehrlichia sp. Ten days after the inoculation of C3H-scid mice with Ehrlichia sp., CXCR2 antisera or control sera were administered i.p., the Ehrlichia DNA content was assessed by semiquantitative PCR (A), and the percentage of peripheral blood neutrophils containing morulae was determined (B). Values obtained for four mice in each group are expressed as means ± standard errors. Results from one of two experiments with similar results are shown.

Assessment of in vivo neutrophil chemotaxis induced by Ehrlichia sp.

To further examine whether Ehrlichia sp. induces the chemoattraction of neutrophils in vivo, we analyzed the neutrophil counts in lavage fluid after injection of ehrlichias into the murine peritoneal cavity. At 4 h after the inoculation of ehrlichias, the influx of neutrophils into the peritoneal cavity was readily detected by flow cytometry by using anti-Gr-1 antibodies (Fig. 11). Ehrlichia sp.-induced neutrophil migration to the peritoneal cavity was significantly decreased when CXCR2 antisera were injected prior to Ehrlichia inoculation (Fig. 11). Injection of control antisera did not inhibit the migration of neutrophils to the peritoneal cavity following Ehrlichia inoculation. Peritoneal lavage fluid from Ehrlichia sp.-inoculated mice also contained higher KC and MIP-2 levels than did fluid from control mice that received blood from uninfected C3H-scid mice. The levels of these chemokines remained high in mice that received CXCR2 antisera (data not shown).

FIG. 11.

The effect of systemically administered antisera against CXCR2 on neutrophil migration to the site of Ehrlichia inoculation. Two groups of three BALB/c mice were i.p. injected with antisera to CXCR2 or control sera prior to i.p. Ehrlichia inoculation. Four hours later, peritoneal lavage fluids from these mice were analyzed by flow cytometry by using fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibodies to Gr-1 molecule. Peritoneal lavage neutrophil counts for these mice were compared with counts for those that did not receive antisera or bacteria and those that received only Ehrlichia sp. Results from one of two representative studies are shown.

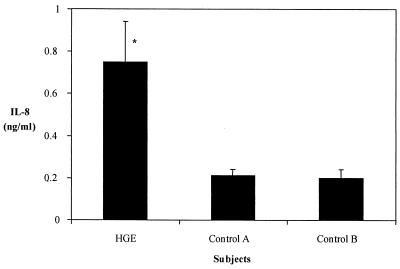

IL-8 levels in sera of patients with HGE.

IL-8 levels were then determined in sera from patients with HGE, collected during a surveillance study for ehrlichiosis in Connecticut (24). Patients with HGE marked by fevers, myalgias, and/or headache and who were PCR positive for the HGE agent in blood samples were considered to be confirmed cases. Control sera were obtained from healthy individuals and from persons who were enrolled in the surveillance study with symptoms that were initially suggestive of HGE (fevers and myalgia) but who did not have laboratory-based evidence of HGE (serology, PCR, or morulae) (Fig. 12). Patients with confirmed HGE had significantly higher levels of IL-8 than did the control groups (P < 0.01). The two control groups had similar levels of IL-8.

FIG. 12.

IL-8 levels in the sera of patients with HGE. HGE, patients with confirmed HGE, based on the clinical history and PCR. Control A, individuals who were clinically suspected of having HGE but who did not have laboratory-based evidence (serology, PCR, or morulae) of infection. Control B, healthy individuals. ∗, IL-8 levels were significantly higher in patients with HGE than in individuals in control group A or B (P < 0.02). Sera from five individuals were examined in each group (HGE, control A, and control B), and results are expressed as means ± standard errors.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate that the HGE agent induces IL-8 production by host cells, which may then paradoxically help promote infection. The results showing that ehrlichias induce IL-8 secretion are consistent with recent data from Klein and colleagues (31) indicating that several chemokines, including IL-8, monocyte chemotactic protein 1, macrophage inflammatory proteins 1α and 1β, and RANTES, were produced by HL-60 cells and normal bone marrow cells in response to HGE bacteria. We now show that peripheral neutrophils also secrete IL-8 upon infection with Ehrlichia sp. Our results further show that IL-8 secretion is accompanied by upregulation of CXCR2, a receptor for IL-8 on HL-60 cells. We also demonstrate that IL-8 is responsible for the chemotaxis of naive neutrophils towards Ehrlichia sp.-infected cells because neutrophil migration to infected cells can be completely blocked with IL-8 antibodies. Moreover, the presence of Ehrlichia DNA in the blood of patients with HGE correlated with increased IL-8 levels, and Ehrlichia infection of murine splenocytes induced high levels of neutrophil chemokines, MIP-2 and KC (the murine homologue for IL-8 has not yet been identified).

Given that the HGE agent survives in neutrophils, migration of neutrophils towards the pathogen results in infection of the newly recruited PMNs, or of their precursors, rather than the elimination of bacteria. We further tested this hypothesis in vivo and demonstrated that CXCR2−/− mice (9) or mice administered CXCR2 antisera prior to Ehrlichia challenge are less susceptible to infection with the HGE agent than are controls. However, scid mice that were previously infected with Ehrlichia sp. remained bacteremic after treatment with CXCR2 antisera, suggesting that neutrophil migration may not play a significant role in bacterial dissemination at this stage, since ehrlichias can continue to spread through the bloodstream. On the other hand, during the initial stages of infection neutrophil propagation to the site of inoculation may be important for the establishment of infection. Indeed, i.p. inoculation of mice with Ehrlichia sp. resulted in an increase in peritoneal KC and MIP-2 levels as well as a neutrophilic influx. Moreover, administration of CXCR2 antisera prior to Ehrlichia challenge of mice blocked the neutrophilic migration to the peritoneal cavity. Decreased migration of PMNs to the initial site of infection may have resulted in the inhibition of systemic HGE infection in mice that received CXCR2 antisera before challenge with Ehrlichia sp.

Neutrophils are critical for the elimination of extracellular and intracellular bacteria. Depletion of neutrophils with antibodies has been shown previously to cause the death of mice infected with sublethal doses of Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, or Salmonella dublin (12, 20, 55, 56). Moreover, the death of E. coli-infected mice deficient in integrin-associated protein was associated with diminished neutrophil migration (33). The role of CXCR2-mediated neutrophil migration in resistance to infection has been further addressed in studies using neutralizing antibodies to murine CXCR2 or in CXCR2−/− mice. Administration of CXCR2 antibodies to mice resulted in decreased resistance to Nocardia asteroides, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Aspergillus spp. (39, 40, 54). CXCR2−/− mice were also more susceptible to gastric or systemic candidiasis after challenge with Candida albicans than were control mice (4). Similarly, in the absence of CXCR2, mice developed severe disease in an E. coli-induced urinary tract infection model while control mice did not develop disease (16). These combined studies clearly demonstrated a role for IL-8 and CXCR2 in resistance to infection.

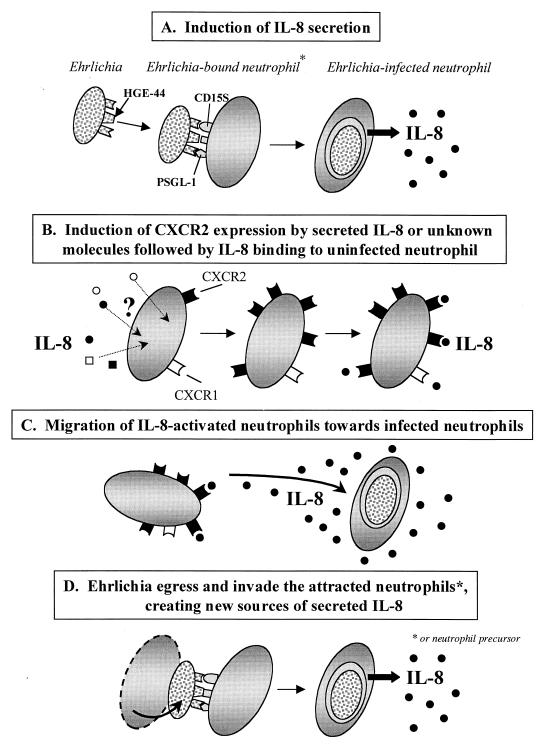

The tropism of Ehrlichia sp. for neutrophils is facilitated by unique mechanisms. Ehrlichias use CD15s (19) and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 to invade neutrophils (22). Once within the neutrophil, HGE bacteria then avoid innate immune responses by residing in morulae that do not fuse with lysosomes (42, 58) and by inhibiting the respiratory burst (43) through downregulation of gp91phox, a critical component of NADPH oxidase (5). Ehrlichias may also partially inhibit neutrophil apoptosis, thereby increasing the duration of survival within the cell (60). Since Ehrlichia sp. is an obligate intracellular pathogen, dissemination is dependent on timely transfer of bacteria to naive neutrophils or neutrophil precursors. Our results suggest that Ehrlichia sp. usurps the induction of IL-8, a host chemokine, and its receptors to attract neutrophils or neutrophil precursors and promote infection (Fig. 13).

FIG. 13.

Schematic model for IL-8-facilitated Ehrlichia dissemination. Host cell IL-8 secretion and the surface expression of CXCR2 on neutrophils or their precursors are induced by Ehrlichia sp. Ehrlichia sp. orchestrates chemotaxis of uninfected neutrophils towards the infected cells, thereby enhancing pathogen transmission. PSGL-1, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1.

Recruitment of neutrophils by microorganisms that have evolved to survive in phagocytic cells can be a model of dissemination for other pathogens. A role for IL-8-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis in the spread of cytomegalovirus has been suggested by Craigen and colleagues (11). Cytomegalovirus induces IL-8 secretion from host cells (11), and neutrophils play a major role in viral dissemination throughout the body (51). Furthermore, the addition of IL-8 to cytomegalovirus-infected cells increases the production of infectious virus (44).

Bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharides (13), Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein OspA (41), listeriolysin O of L. monocytogenes (28), and Shiga toxin (53) have been shown elsewhere to activate neutrophils through induction of IL-8 secretion from host cells. Our data now show that HGE-44 is capable of stimulating IL-8 secretion from rHL-60 cells and from PMNs in a dose-dependent manner. It is not known whether HGE-44 alone or various members of this family of proteins are the sole bacterial products that induce IL-8 secretion. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides are potent IL-8-inducing molecules, but although the HGE bacterial membrane may have characteristics consistent with gram-negative organisms (46), there is at present no evidence of lipopolysaccharide in HGE bacteria. Indeed, our experiments showed that Ehrlichia sp. does not induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β) that are typically associated with lipopolysaccharide stimulation of IL-8. It is also noteworthy that none of the other human CXCR2 ligand molecules that can be associated with IL-8 secretion during other infections were increased during Ehrlichia infection (48, 59).

In summary, we have shown that infection with the HGE agent induces the secretion of human IL-8 and upregulates expression of the CXCR2 receptor on host cells. HGE-44 is one of the ligands that contribute to the generation of IL-8. The production of this chemokine is important for Ehrlichia infectivity because Ehrlichia sp.-induced IL-8 results in neutrophil chemotaxis, and granulocytic ehrlichiosis is diminished in CXCR2−/− mice or animals administered CXCR2 antisera. The HGE agent appears, therefore, to paradoxically exploit the response of host IL-8, a chemokine normally used for microbial eradication, to facilitate infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Mathers Foundation, and the Eshe Foundation and a gift from SmithKline Beecham Biologicals. E. Fikrig is the recipient of a Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

We thank Rita Palmarozza and Debbie Beck for technical assistance and Isabelle Coppens for her help in the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, McKenna D F, Nowakowski J, Munoz J, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: a case series from a medical center in New York State. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:904–908. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-11-199612010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akkoyunlu M, Fikrig E. Gamma interferon dominates the murine cytokine response to the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and helps to control the degree of early rickettsemia. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1827–1833. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1827-1833.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken J S, Erlemeyer S A, Kanoff R J, Silvestrini T C, Goodwin D D, Dumler J S. Demyelinating polyneuropathy associated with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1323–1324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balish E, Wagner R D, Vazquez-Torres A, Jones-Carson J, Pierson C, Warner T. Mucosal and systemic candidiasis in IL-8Rh-/- BALB/c mice. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:144–150. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee R, Anguita J, Roos D, Fikrig E. Infection by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis prevents the respiratory burst by down-regulating gp91phox. J Immunol. 2000;164:3946–3949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behl R, Klein M B, Dandelet L, Bach R R, Goodman J L, Key N S. Induction of tissue factor procoagulant activity in myelomonocytic cells inoculated by the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Thromb Haemostasis. 2000;83:114–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belongia E A, Reed K D, Mitchell P D, Chyou P H, Mueller-Rizner N, Finkel M F, Schriefer M E. Clinical and epidemiological features of early Lyme disease and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1472–1477. doi: 10.1086/313532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunnell J E, Trigiani E R, Srinivas S R, Dumler J S. Development and distribution of pathologic lesions are related to immune status and tissue deposition of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent-infected cells in a murine model system. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:546–550. doi: 10.1086/314902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cacalano G, Lee J, Kikly K, Ryan A M, Pitts-Meek S, Hultgren B, Wood W I, Moore M W. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265:682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chuntharapai A, Kim K J. Regulation of the expression of IL-8 receptor A/B by IL-8: possible functions of each receptor. J Immunol. 1995;155:2587–2594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craigen J L, Yong K L, Jordan N J, MacCormac L P, Westwick J, Akbar A N, Grundy J E. Human cytomegalovirus infection up-regulates interleukin-8 gene expression and stimulates neutrophil transendothelial migration. Immunology. 1997;92:138–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czuprynski C J, Brown J F, Maroushek N, Wagner R D, Steinberg H. Administration of anti-granulocyte mAb RB6-8C5 impairs the resistance of mice to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1994;152:1836–1846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeForge L E, Kenney J S, Jones M L, Warren J S, Remick D G. Biphasic production of IL-8 in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human whole blood. Separation of LPS- and cytokine-stimulated components using anti-tumor necrosis factor and anti-IL-1 antibodies. J Immunol. 1992;148:2133–2141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denney C F, Eckmann L, Reed S L. Chemokine secretion of human cells in response to Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1547–1552. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1547-1552.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumler J S, Bakken J S. Human ehrlichiosis: newly recognized infections transmitted by ticks. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:201–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frendeus B, Godaly G, Hang L, Karpman D, Lundstedt A C, Svanborg C. Interleukin 8 receptor deficiency confers susceptibility to acute experimental pyelonephritis and may have a human counterpart. J Exp Med. 2000;192:881–890. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gewirtz A T, Rao A S, Simon P O, Jr, Merlin D, Carnes D, Madara J L, Neish A S. Salmonella typhimurium induces epithelial IL-8 expression via Ca(2+)-mediated activation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J Clin Investig. 2000;105:79–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI8066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman J L, Nelson C, Vitale B, Madigan J E, Dumler J S, Kurtti T J, Munderloh U G. Direct cultivation of the causative agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601253340401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman J L, Nelson C M, Klein M B, Hayes S F, Weston B W. Leukocyte infection by the granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent is linked to expression of a selectin ligand. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:407–412. doi: 10.1172/JCI4230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haraoka M, Hang L, Frendeus B, Godaly G, Burdick M, Strieter R, Svanborg C. Neutrophil recruitment and resistance to urinary tract infection. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1220–1229. doi: 10.1086/315006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardalo C J, Quagliarello V, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Connecticut: report of a fatal case. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:910–914. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herron M J, Nelson C M, Larson J, Snapp K R, Kansas G S, Goodman J L. Intracellular parasitism by the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis bacterium through the P-selectin ligand, PSGL-1. Science. 2000;288:1653–1656. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodzic E, Ijdo J W, Feng S, Katavolos P, Sun W, Maretzki C H, Fish D, Fikrig E, Telford S R, Barthold S W. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the laboratory mouse. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:737–745. doi: 10.1086/514236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ijdo J W, Meek J I, Cartter M L, Magnarelli L A, Wu C, Tenuta S W, Fikrig E, Ryder R W. The emergence of another tickborne infection in the 12-town area around Lyme, Connecticut: human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1388–1393. doi: 10.1086/315389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ijdo J W, Sun W, Zhang Y, Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E. Cloning of the gene encoding the 44-kilodalton antigen of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis and characterization of the humoral response. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3264–3269. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3264-3269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ijdo J W, Wu C, Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E. Serodiagnosis of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by a recombinant HGE-44-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3540–3544. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3540-3544.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahangir A, Kolbert C, Edwards W, Mitchell P, Dumler J S, Persing D H. Fatal pancarditis associated with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a 44-year-old man. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1424–1427. doi: 10.1086/515014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayal S, Lilienbaum A, Poyart C, Memet S, Israel A, Berche P. Listeriolysin O-dependent activation of endothelial cells during infection with Listeria monocytogenes: activation of NF-kappa B and upregulation of adhesion molecules and chemokines. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1709–1722. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H Y, Rikihisa Y. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies to the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3278–3284. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3278-3284.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H Y, Rikihisa Y. Expression of interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-6 in human peripheral blood leukocytes exposed to human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent or recombinant major surface protein P44. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3394–3402. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3394-3402.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein M B, Hu S, Chao C C, Goodman J L. The agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis induces the production of myelosuppressing chemokines without induction of proinflammatory cytokines. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:200–205. doi: 10.1086/315641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klein M B, Miller J S, Nelson C M, Goodman J L. Primary bone marrow progenitors of both granulocytic and monocytic lineages are susceptible to infection with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1405–1409. doi: 10.1086/517332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindberg F P, Bullard D C, Caver T E, Gresham H D, Beaudet A L, Brown E J. Decreased resistance to bacterial infection and granulocyte defects in IAP-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:795–798. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luzza F, Parrello T, Monteleone G, Sebkova L, Romano M, Zarrilli R, Imeneo M, Pallone F. Up-regulation of IL-17 is associated with bioactive IL-8 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. J Immunol. 2000;165:5332–5337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahalingam S, Karupiah G. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in infectious diseases. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77:469–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manna S K, Bhattacharya C, Gupta S K, Samanta A K. Regulation of interleukin-8 receptor expression in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:883–893. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin M E, Bunnell J E, Dumler J S. Pathology, immunohistology, and cytokine responses in early phases of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a murine model. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:374–378. doi: 10.1086/315206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsushima K, Oppenheim J J. Interleukin 8 and MCAF: novel inflammatory cytokines inducible by IL 1 and TNF. Cytokine. 1989;1:2–13. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(89)91043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehrad B, Strieter R M, Moore T A, Tsai W C, Lira S A, Standiford T J. CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligands are necessary components of neutrophil-mediated host defense in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Immunol. 1999;163:6086–6094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore T A, Newstead M W, Strieter R M, Mehrad B, Beaman B L, Standiford T J. Bacterial clearance and survival are dependent on CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligands in a murine model of pulmonary Nocardia asteroides infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:908–915. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrison T B, Weis J H, Weis J J. Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein A (OspA) activates and primes human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1997;158:4838–4845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mott J, Barnewall R E, Rikihisa Y. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and Ehrlichia chaffeensis reside in different cytoplasmic compartments in HL-60 cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1368–1378. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1368-1378.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mott J, Rikihisa Y. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits superoxide anion generation by human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6697–6703. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6697-6703.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murayama T, Kuno K, Jisaki F, Obuchi M, Sakamuro D, Furukawa T, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Enhancement of human cytomegalovirus replication in a human lung fibroblast cell line by interleukin-8. J Virol. 1994;68:7582–7585. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7582-7585.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy C I, Storey J R, Recchia J, Doros-Richert L A, Gingrich-Baker C, Munroe K, Bakken J S, Coughlin R T, Beltz G A. Major antigenic proteins of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis are encoded by members of a multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3711–3718. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3711-3718.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogden N H, Woldehiwet Z, Hart C A. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis: an emerging or rediscovered tick-borne disease? J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:475–482. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-6-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petrovec M, Furlan S L, Zupanc T A, Strle F, Brouqui P, Roux V, Dumler J S. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic ehrlichia species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1556–1559. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1556-1559.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimoyama T, Everett S M, Dixon M F, Axon A T, Crabtree J E. Chemokine mRNA expression in gastric mucosa is associated with Helicobacter pylori cagA positivity and severity of gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:765–770. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.10.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun W, Ijdo J W, Telford S R, Hodzic E, Zhang Y, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Immunization against the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in a murine model. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:3014–3018. doi: 10.1172/JCI119855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Telford S R, Lepore T J, Snow P, Warner C K, Dawson J E. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Massachusetts. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:277–279. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-4-199508150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The T H, Van Den Berg A P, Harmsen M C, Van Der Bij W, Van Son W J. The cytomegalovirus antigenemia assay: a plea for standardization. Scand J Infect Dis. 1995;99(Suppl.):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas V, Anguita J, Barthold S W, Fikrig E. Coinfection with Borrelia burgdorferi and the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis alters murine immune responses, pathogen burden, and the severity of Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3359–3371. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3359-3371.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thorpe C M, Hurley B P, Lincicome L L, Jacewicz M S, Keusch G T, Acheson D W. Shiga toxins stimulate secretion of interleukin-8 from intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5985–5993. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5985-5993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai W C, Strieter R M, Mehrad B, Newstead M W, Zeng X, Standiford T J. CXC chemokine receptor CXCR2 is essential for protective innate host response in murine Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4289–4296. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4289-4296.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vassiloyanakopoulos A P, Okamoto S, Fierer J. The crucial role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in resistance to Salmonella dublin infections in genetically susceptible and resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7676–7681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verdrengh M, Tarkowski A. Role of neutrophils in experimental septicemia and septic arthritis induced by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2517–2521. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2517-2521.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker D H, Dumler J S. Human monocytic and granulocytic ehrlichioses. Discovery and diagnosis of emerging tick-borne infections and the critical role of the pathologist. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Webster P, IJdo J W, Chicoine L M, Fikrig E. The agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis resides in an endosomal compartment. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:1932–1941. doi: 10.1172/JCI1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wyrick P B, Knight S T, Paul T R, Rank R G, Barbier C S. Persistent chlamydial envelope antigens in antibiotic-exposed infected cells trigger neutrophil chemotaxis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:954–966. doi: 10.1086/314676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshiie K, Kim H Y, Mott J, Rikihisa Y. Intracellular infection by the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits human neutrophil apoptosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1125–1133. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1125-1133.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y. Multiple p44 genes encoding major outer membrane proteins are expressed in the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17828–17836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhi N, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, Hechemy K. Cloning and expression of the 44-kilodalton major outer membrane protein gene of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and application of the recombinant protein to serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1666–1673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1666-1673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]