Abstract

Objective

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause for non-elective infant hospitalization in the US with increasing utilization of high flow nasal cannula (HFNC). We standardized initiation and weaning of HFNC for bronchiolitis and quantified the impact on outcomes. Our specific aim was to reduce hospital and intensive-care-unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS) by 10% between two bronchiolitis seasons after implementation.

Design

A quality improvement (QI) project using statistical process control methodology.

Setting

Tertiary care children’s hospital with 24 PICU and 48 acute care pediatric beds.

Patients

Children <24 months old with bronchiolitis without other respiratory diagnoses or underlying cardiac, respiratory, or neuromuscular disorders between December 2017-November 2018 (baseline) and December 2018-February 2020 (post-intervention).

Interventions

Interventions included development of a HFNC protocol with initiation and weaning guidelines, modification of protocol and respiratory assessment classification, education, and QI rounds with a focus on efficient HFNC weaning, transfer, and/or discharge.

Measurements and Main Results

A total of 223 children were included (96 baseline, 127 post-intervention). The primary outcome metric, average LOS per patient, decreased from 4.0 to 2.8 days, and the average ICU LOS per patient decreased from 2.8 to 1.9 days. The secondary outcome metric, average HFNC treatment hours per patient, decreased from 44.0 to 36.3 hours. Primary and secondary outcomes met criteria for special cause variation. Balancing measures included ICU readmission rates, 30-day readmission rates, and adverse events, which were not different between the two periods.

Conclusion

A standardized protocol for HFNC management for patients with bronchiolitis was associated with decreased hospital and ICU LOS, less time on HFNC, and no difference in readmissions or adverse events.

Keywords: bronchiolitis, oxygen saturation, noninvasive ventilation, intensive care unit, length of stay, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants <1 year old1 accounting for approximately 100,000 United States hospitalizations annually with estimated cost of $734 billion.2 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends supportive treatment with suctioning and supplemental oxygen targeting oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≥90%.1 For children with severe illness, respiratory support beyond nasal cannula such as high flow nasal cannula (HFNC), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), and/or intubation may be necessary. Data from a critical care database showed that HFNC therapy has been increasingly used in bronchiolitis management and associated with decreased intubation comparing initial HFNC therapy vs CPAP/BiPAP.3 Randomized controlled trials comparing HFNC with standard oxygen therapy showed decreased treatment failure and escalation of care compared to those on standard oxygen therapy.4,5 HFNC is still primarily utilized in the intensive care unit (ICU) across North America6 despite studies demonstrating safety of HFNC use outside the ICU7,8 with significantly decreased average admission cost.9 However, as the availability of HFNC expands, it is imperative that it does not become used when medically unnecessary.10,11

Prior to this initiative, patients at our institution with bronchiolitis requiring HFNC were exclusively managed in the emergency department (ED) or ICU where initiation flow level and subsequent flow titration were at the discretion of individual providers. We observed a longer mean length of stay (LOS) for bronchiolitis compared to other academic medical centers,12 identifying an opportunity to reduce our bronchiolitis LOS by standardizing HFNC management through quality improvement (QI) interventions. The primary aim of this collaborative QI project was to reduce hospital and ICU LOS by 10% (to bring our LOS closer to that of other institutions)12 within two bronchiolitis seasons after implementation of standardized HFNC management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Context and Settings

With approval from the University of California, Davis, Institutional Review Board (IRB #1219188–2), children <24 months old with a primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis were identified by ICD codes (ICD9: 466.1, 466.11, 466.19, 516.34; ICD10: J21.0, J21.1, J21.8, J21.9, J84.115). Exclusion criteria included diagnoses of co-bacterial pneumonia or steroid treatment, anatomic/acquired airway anomalies, hemodynamically significant cardiac conditions, chronic respiratory diseases with baseline oxygen requirement, apnea/bradycardia requiring intervention, or neuromuscular disorders. The baseline period was defined as December 2017-November 2018 with data collected retrospectively. The HFNC protocol was implemented in December 2018 in the ED and ICU. The post-intervention period was defined as December 2018-February 2020 with data collected prospectively. No other medication or equipment changes were introduced throughout the study period.

QI team and HFNC protocol

We created a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists (RT), and QI experts from the pediatric hospitalist, emergency medicine, and ICU departments to develop a protocol standardizing the initiation and management of patients requiring HFNC. The protocol defined initial oxygen flow rate, assessment frequency, and flow rate weaning if fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) was <0.5 (eFigure 1). Titration and initiation flow rates were based on the Respiratory Assessment Classification (RAC, eFigure 2), a new assessment tool created based on expert consensus at our institution and adapted from another protocol.13 Titration of FIO2 was based on SpO2 targeting SpO2 ≥88% while asleep and ≥90–95% while awake. The protocol promoted enteral nutrition within six hours with RAC-based criteria for types of feeds (i.e. oral, nasogastric or nasoduodenal tube). For patients ≥4 months of age receiving HFNC therapy, the protocol defined out-of-ICU transfer criteria based on the consensus of the multidisciplinary QI team, which required meeting all of the following for ≥6 hours: 1) suctioning ≤every 2 hours, 2) HFNC flow rate ≤1L/kg/min (or ≤10 L/min for patients >10 kg), and 3) FIO2 <0.5. Out-of-ICU transfer while receiving HFNC started in November 2019.

Study of the Intervention

Following an improvement science model, interventions were tested using Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles.14 eTable 1 provides a description of each PDSA cycle, and a summary of the key practice changes adopted, which include RAC and protocol modifications, QI rounds focusing on protocol implementation and efficiency, and education for residents, nurses, and RTs. The PDSA process allowed for protocol refinement and addressed identified practice barriers.

Measures

Primary outcome measures were average LOS per patient in days per month ((total LOS for all bronchiolitis patients receiving HFNC that month)/(total number of bronchiolitis patients receiving HFNC that month)) and average ICU LOS per patient in days per month ((total ICU LOS for all bronchiolitis patients receiving HFNC that month)/(total number of bronchiolitis patients receiving HFNC that month)). The secondary outcome measures were average HFNC hours per patient per month ((total HFNC hours for all bronchiolitis patients that month)/(total number of bronchiolitis patients receiving HFNC that month)), and highest flow rate at which feeds were permitted. The process measure was protocol adherence, defined as appropriate adjustment of both flow and FIO2 per protocol ≥75% of the time as determined by an external reviewer. The LOS and HFNC duration were extracted from electronic health record (EHR) in minutes, which were converted to hours (HFNC duration) and days (LOS). We measured ICU-readmission rates, 30-day readmission rates, and adverse events (escalation of respiratory support to CPAP/BiPAP/intubation and death) as balancing measures. We also utilized EHR data to compare hours of HFNC therapy over the SpO2 target of 95% while the FiO2>0.21 as another indirect way to evaluate for adherence to the FIO2 part of the protocol.

Analysis

We monitored the impact of implementation through statistical process control (SPC). Primary and secondary outcomes were tracked monthly with x-bar-s-charts and established rules for differentiating special cause variation were followed, including ≥8 consecutive points on one side of the mean and ≥4 of 5 consecutive points >1 sigma from the mean.14 Months containing <3 patients meeting inclusion criteria were omitted. Time of admission, transfer orders in/out of ICU, highest flow rate, and highest flow rate at which enteral feeding was permitted were manually extracted from the EHR and stored in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).15 Continuous respiratory support settings, FIO2, and SpO2 were extracted from EHR data. SPC for Excel, version 5 was used to create the x-bar-s-charts. Using Stata 16.1,16 descriptive statistics and group differences were computed using t-tests. The t test for equality of means was computed by linear regression using the regress command and the t test for equality of medians was computed by median regression using the greg command.

For the patients in the baseline and intervention groups who had clinical information available, we extracted data from Virtual Pediatric System (VPS) to derive a severity of illness score using Pediatric Infant Mortality (PIM) 3 for baseline and intervention groups.17

RESULTS

A total of 223 patients were included (baseline: 96, intervention: 127). The age, gender, viral etiology, presenting ED, starting respiratory support (for patients who presented to our ED), initial admission level of care, and distribution of severity of illness measured by PIM-318 were similar in both timeframes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Baseline (N = 96) | Post-intervention (N = 127) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in months, median (IQR) | 7.5 (4–13.5) | 8 (3–14) | 0.99 |

| < 4 months, N (%) | 23 (24) | 33 (26) | 0.73 |

| Female, N (%) | 33 (34) | 39 (31) | 0.65 |

| Weight < 10 kg, N (%) | 67 (70) | 85 (67) | 0.65 |

| Respiratory Viral Illnesses a | |||

| Rhino/enterovirus, N (%) | 34 (44) | 57 (55) | 0.14 |

| RSV, N (%) | 34 (44) | 35 (34) | 0.17 |

| Adenovirus, N (%) | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | 0.09 |

| Coronavirus (not COVID-19), N (%) | 7 (9) | 4 (4) | 0.15 |

| Influenza, N (%) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | 0.76 |

| Parainfluenza, N (%) | 1 (1) | 6 (6) | 0.12 |

| Starting respiratory support b | 0.59 | ||

| None, N (%) | 4 (11) | 6 (11) | |

| LFNC or mask, N (%) | 5 (14) | 4 (7) | |

| HFNC, N (%) | 27 (75) | 44 (79) | |

| NIPPV, N (%) | 0 | 2 (4) | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, N (%) | 0 | 0 | |

| First emergency department location | 0.32 | ||

| Local institution, N (%) | 36 (38) | 56 (44) | |

| Referring ED, N (%) | 60 (63) | 71 (56) | |

| Admission location | 0.35 | ||

| Wards, N (%) | 12 (13) | 11 (9) | |

| PICU, N (%) | 84 (88) | 116 (91) | |

| PIM3, median (IQR) c | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | 1.00 |

Respiratory viral data was not available for all patients so baseline N=78 patients, post-intervention =105 and the respective N’s were used as demonimators in calculating frequency. Total percentage ≥100% because some patients were positive for more than one virus.

Starting support shown for patients that presented to our ED first so baseline N=36, post-intervention N=56 and the respective N’s are used as denominatiors for calculating frequencies.

PIM3 data was not available for all patients so baseline N=80, post-intervention N=114

PIM3 = Pediatric Index of Mortality 3, ED = Emergency department, PICU = pediatric intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, LFNC = low flow nasal cannula defined as < 4L/min, NIPPV = non-invasive positive pressure such as continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation

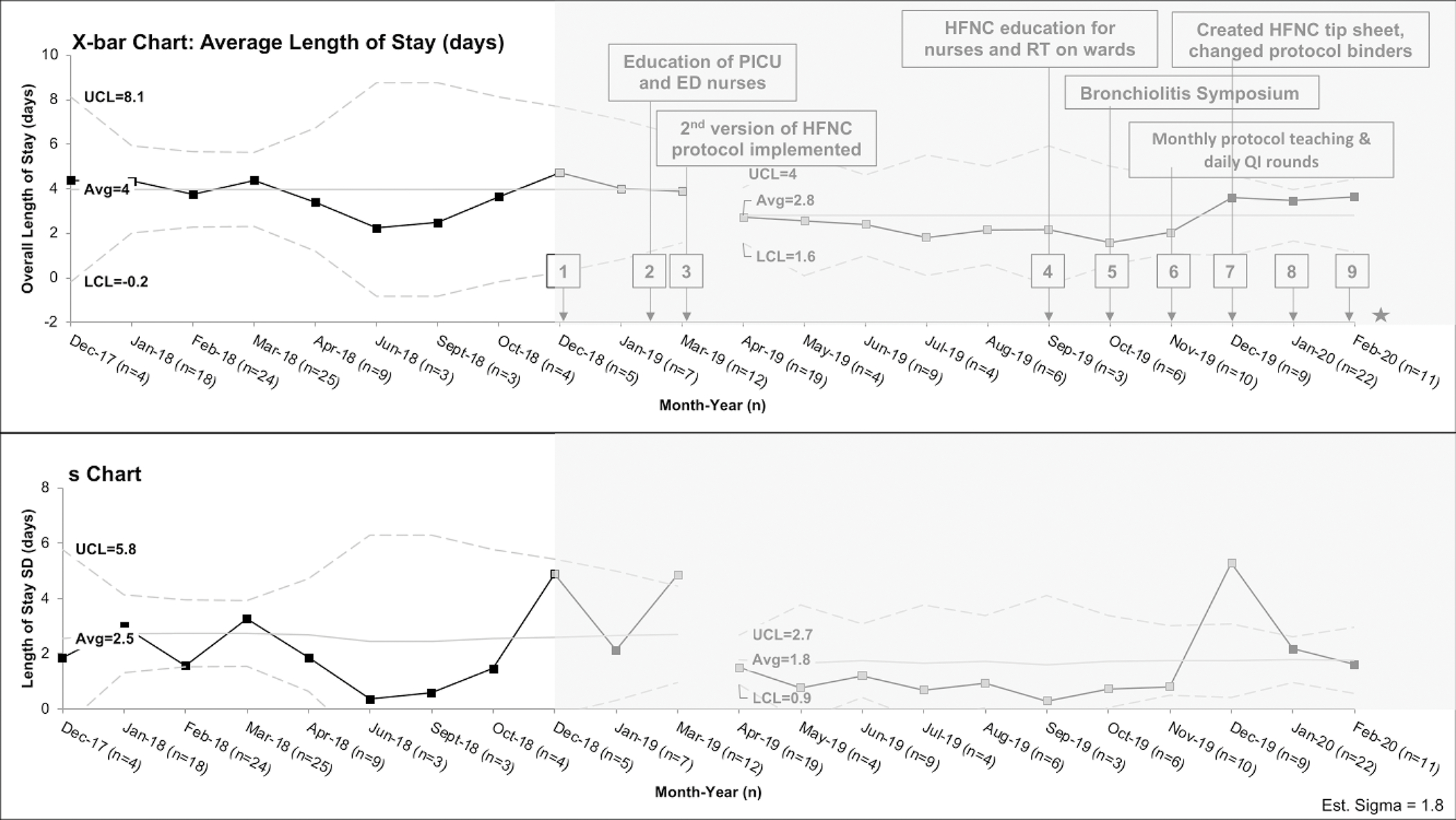

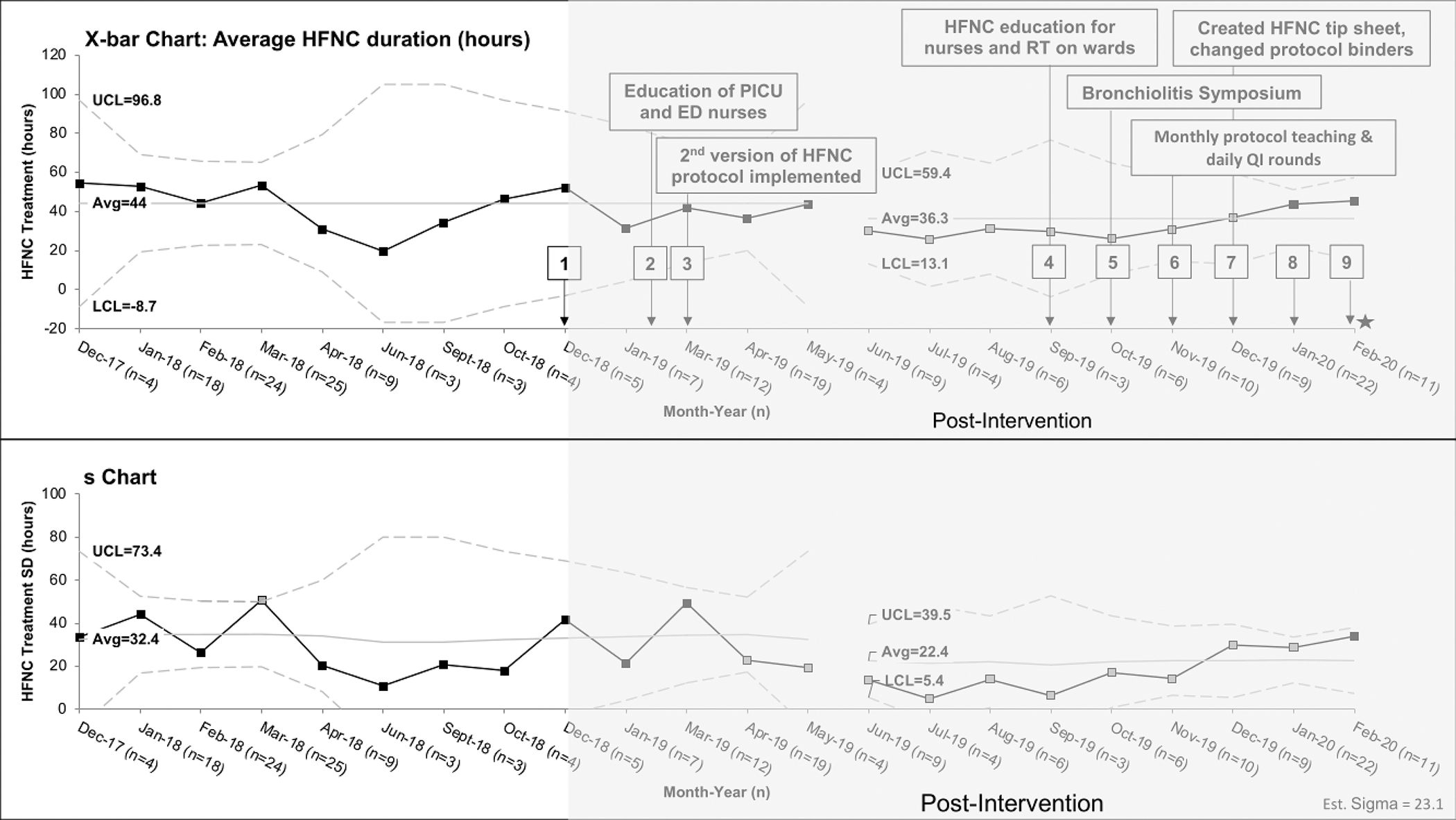

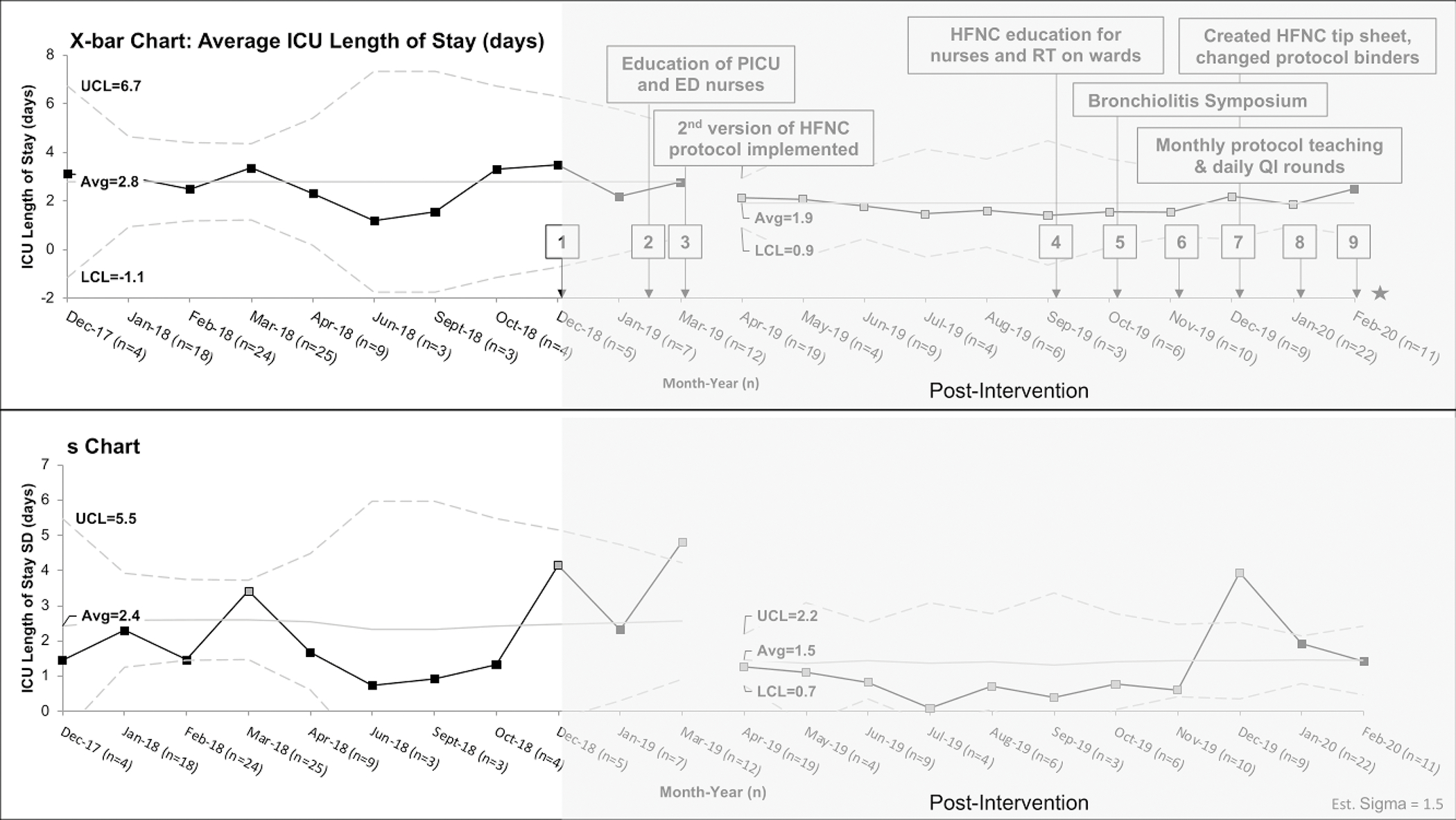

Primary and secondary outcomes are shown in x-bar-s-charts in Figures 1 through 3. The breaks in centerline and control limits were introduced based on the identification of special cause variation for each outcome. In each figure, the post-intervention period is shaded in gray and key PDSA cycle numbers are shown in black boxes.

Figure 1: X-bar-s-chart of Hospital Length of Stay.

X-bar-s-chart showing average hospital length of stay per patient, the upper and lower limit are derived from the subgroup standard deviation. The interventions in each PDSA cycle are listed in eTable 1 but the most effective interventions are shown in the figure. Monthly periods containing less than 3 patients meeting inclusion criteria were omitted (May 2018, July 2018, Aug 2018, November 2018, February 2019) from analysis. The post-intervention period is shaded in gray and key PDSA cycle numbers are shown in black boxes. The grey boxes are the points that meet special cause variation and the gap between March and April 2019 represent the shift from baseline. The star refers to interruption of QI project due to COVID19 pandemic. PICU=pediatric intensive care unit, ED=emergency department, HFNC=high flow nasal cannula, RT=respiratory therapist, and QI=quality improvement

Figure 3: X-bar-s-chart of high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) duration in hours.

X-bar-s-charts of the average HFNC treatment hours per patients, the upper and lower limit are derived from the subgroup standard deviation. The interventions in each PDSA cycle are listed in eTable 1 but the most effective interventions are shown in the figure. Monthly periods containing less than 3 patients meeting inclusion criteria were omitted (May 2018, July 2018, Aug 2018, November 2018, February 2019) from analysis. The post-intervention period is shaded in gray and key PDSA cycle numbers are shown in black boxes. The grey boxes are the points that meet special cause variation and the gap between May and June 2019 represent the shift from baseline. The star refers to interruption of QI project due to COVID19 pandemic. PICU=pediatric intensive care unit, ED=emergency department, HFNC=high flow nasal cannula, RT=respiratory therapist, and QI=quality improvement

Average hospital LOS per patient declined from 4.0 days in the baseline period to 2.8 days in the post-intervention period, meeting criteria for special cause variation (Figure 1). There is a significant downward shift from April-November 2019 with an accompanying decrease in LOS variability. We were in our 6th PDSA cycle in November 2019, when we started transferring patients out of ICU while still receiving HFNC (eTable 1). Average ICU LOS per patient declined from 2.8 days in the baseline period to 1.9 days in the post-intervention period, also meeting criteria for special cause variation (Figure 2). There is a significant shift from April 2019-January 2020 with accompanying decrease in variability through November 2019. The downward trend and decreased variation for these outcomes correlate with increased education to nurses, RTs, and other members of the care team.

Figure 2: X-bar-s-chart of intensive care unit (ICU) Length of Stay.

X-bar-s-charts of the average ICU length of stay per patients, the upper and lower limit are derived from the subgroup standard deviation. The interventions in each PDSA cycle are listed in eTable 1 but the most effective interventions are shown in the figure. Monthly periods containing less than 3 patients meeting inclusion criteria were omitted ((May 2018, July 2018, Aug 2018, November 2018, February 2019) from analysis. The post-intervention period is shaded in gray and key PDSA cycle numbers are shown in black boxes. The grey boxes are the points that meet special cause variation and the gap between March and April 2019 represent the shift from baseline. The star refers to interruption of QI project due to COVID19 pandemic.

PICU=pediatric intensive care unit, ED=emergency department, HFNC=high flow nasal cannula, RT=respiratory therapist, and QI=quality improvement

Average HFNC duration per patient also decreased by 7 hours (Baseline: 44.0 hours vs Post-intervention: 36.3 hours, Figure 3) with significant downward shift from June-December 2019 with accompanying decrease in variability. Median hours of respiratory support were less in the post-intervention group for all devices except mechanical ventilation (Table 2). The post-intervention group had higher maximum flow rate on the protocol (Baseline: 12L/min for ≥10kg vs Post-intervention: 15L/min, p=0.07), but was also allowed to feed on higher flow rate (Baseline: 6L/min for ≥10kg vs Post-intervention: 14L/min, p<0.001) (Table 2). There was no difference between groups in ICU-readmission after transfer to wards, 30-day hospital readmission, escalation to NIPPV/intubation, or death (Table 2). Average protocol adherence to flow and FIO2 titration throughout the intervention period was 66%. The baseline group had 30 hours of HFNC therapy over-SpO2 target of 95% compared with 16 hours in the post-intervention group.

Table 2:

Secondary Outcomes, Balancing Measures and Median Hours of Respiratory Support

| Outcomes | Baseline N = 96 | Post-intervention N = 127 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest HFNC in patients >=10 kg, L/min, median (IQR) | 12 (9–15) | 15 (14–20) | 0.07 |

| Highest HFNC allowed to PO in patients >=10 kg, L/min, median (IQR) | 6 (3.5–12) | 14 (12–15) | <0.001 |

| Highest HFNC in patients <10 kg, L/min/kg, median (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 1.6 (1.1–1.9) | 0.04 |

| Highest HNFC allowed to PO in patients <10 kg, L/min/kg, median (IQR) | 1 (0.7–1.2) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Median hours of respiratory support (IQR) | |||

| Room air | 22.5 (18.5–29) | 17.5 (10.6–24.4) | 0.001 |

| LFNC | 8.6 (3.8–21.5) | 4.2 (1.7–11.5) | 0.09 |

| HFNC | 32.6 (23.9–54.9) | 27.8 (20.8–48.2) | 0.17 |

| HFNC (FiO2 = 0.21) | 11.8 (4.2–23.2) | 16.0 (9.2–23.1) | 0.20 |

| HFNC (FiO2 > 0.21) | 31.0 (17.7 – 45.1) | 16.9 (5.3–36.2) | <0.001 |

| Over SpO2-target (95%) | 27.7 (19.1–50) | 15.1 (5–26.6) | <0.001 |

| NIPPV | 13.9 (3.1–40.3) | 27.2 (10.6–36.8) | 0.23 |

| Mechanical Ventilation | 56.8 (50.2–78) | 129.6 (82.9–170.9) | 0.28 |

| ICU readmission, N (%) | 7 (7) | 6 (5) | 0.42 |

| 30-day readmission, N (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | >0.9 |

| Escalation to NIPPV/intubation, N (%) | 17 (18) | 21 (16) | 0.82 |

HFNC = high flow nasal cannula, IQR = interquartile range, PO = oral feeding, LFNC = low flow nasal cannula defined as < 4L/min, SpO2 = oxygen saturation, NIPPV = non-invasive positive pressure such as continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway pressure, ICU = intensive care unit

DISCUSSION

A QI initiative to standardize HFNC management for patients with bronchiolitis decreased average hospital and ICU LOS with decreased HFNC duration. There was no increase in adverse events. ICU and hospital readmission rates were similar between timeframes.

Our multidisciplinary QI methodology with completion of nine PDSA cycles allowed for successful implementation of protocolized HFNC management for bronchiolitis. Challenges to protocol adherence included varying patient volume related to bronchiolitis seasonality, lack of protocol familiarity, and duplicated paper documentation. The most effective interventions addressing these challenges included education, QI rounds focusing on protocol adherence/efficiency with real-time education to increase protocol familiarity and reinforcing paper charting. To ensure sustainability of educational interventions, hospitalists provided monthly education on bronchiolitis and the standardized HFNC protocol to residents rotating through wards. Faster wean, shorter HFNC duration, allowing PO feeds on higher flow, and efforts for timely transfer/discharge of eligible patients may have contributed to the significantly shorter PICU LOS in the post-intervention group. Interestingly, decreased hospital and ICU LOS were observed prior to decrease in HFNC duration suggesting that other factors (i.e., higher initiation flow rate, promoting earlier feeds) may have contributed to shorter LOS. Implementation of the 2nd version with simplified RAC and protocol highlighting FIO2 weaning in March 2019 may also have facilitated the shorter LOS in April 2019. Given that the magnitude of the decrease HFNC duration was less than that of the decrease LOS, the decrease HFNC duration may not be the main driver for the observed decreased LOS.

The success of a multidisciplinary QI initiative to cause a practice change resulting in decreased ICU LOS is particularly important given the cost differences associated with ICU vs ward-level care.9 Others have found a $2,920 median hospital charges reduction when initiating HFNC therapy on wards vs ICU.19 A multicenter database study found PICU admission cost for bronchiolitis has doubled from $1.01 billion in 2009–10 to $2.07 billion in 2018–19.20 The subgroup with the largest relative cost increase are those who were not mechanically ventilated, suggesting use of HFNC or CPAP/BiPAP may be contributing to the rising cost.20 A review highlighted decline in bronchiolitis admissions during a period when hospital charges had been increasing and allowing HFNC on wards could help reduce cost.21 This is further supported by findings that increased HFNC use, a noninvasive modality mostly utilized in the PICU, coincided with rising PICU admission worldwide in the last two decades.22 Beside hospital/ICU admission related costs, families are significantly burdened by hospitalization with work disruption, meals/parking costs, and/or need for additional caregivers. While we did not directly measure costs, our work improved hospital LOS and in-hospital resource allocation, therefore, likely reduced both direct and indirect costs of care.20,21,23–25

Our results are in line with previous studies that found reduced LOS,26,27 but both prior studies initiated HFNC on wards without including initiation/weaning guidelines. Our protocol included children ≥18 months, applied maximal flow of 2L/kg/min and still found decreased HFNC time with no increased PICU transfer or adverse events, demonstrating higher initiation flow rates can be safely utilized. Noelck et al. allowed HFNC flow rates up to 2 L/kg/min, but their intervention focused on reducing lower flow rates duration without change in total HFNC duration.26 The criteria for HFNC initiation in our protocol was intended to help ensure HFNC was not the first-line therapy, a limitation that has been identified in other institutional guidelines.10 However, interestingly HFNC was used as the starting support in a similar frequency in the post-intervention group, thus warranting further evaluation on the ideal initiation recommendation. Another RT-driven HFNC QI protocol with age group-based recommendations for flow and FIO2 titration to target SpO2 ≥92% found similar reduction in HFNC duration, hospital/PICU LOS.28 They had higher protocol compliance ≥80%, which may be related to RT involvement and more specific guidelines regarding types of cannula to use and frequency of assessment during titration. Another HFNC study introducing a “holiday” wean resulted in 70% success rate of patients being weaned to low-flow nasal cannula during first attempts, suggesting faster weaning may be achieved.29 We have adopted a similar HFNC “holiday” since completion of our study and are currently evaluating this approach.

There are no national HFNC guidelines for bronchiolitis, thus, substantial variability in how HFNC is initiated/weaned and permitted to feed among institutions.30,31 Our rationale to initiate flow up to 2L/kg/min in our protocol is based on studies demonstrating no adverse effects in patients with bronchiolitis treated with HFNC at 2 L/kg/min.32 Our institution lacked specific SpO2 target range for HFNC monitoring and weaning, and in our literature search, SpO2 target range was often not published in many institutional bronchiolitis clinical guidelines. 7–9,19,33 We targeted a lower limit for SpO2 ≥90% per AAP guidelines1 but also allowed lower saturation ≥88% while asleep based on work that supports the safety of lower saturation.34,35 Although more research is needed to determine the optimal SpO2 range for bronchiolitis management in the PICU, prior works have shown that SpO2 is a primary determinant of LOS and cautioned against targeting too high SpO2 goals, thus, our rationale for including an upper limit on our SpO2 range.36–38 We noted decrease durations for HFNC with FIO2 >21% use and time spent over-SpO2 target (>95%) while receiving FIO2 >21% during our post-intervention phase, an improvement that support the need for guideline with specific SpO2 target that are more in line with bronchiolitis guidelines. Regarding our rationale for our feeding protocol, previous studies demonstrated low incidence of feeding-related adverse events while on HFNC with delayed/interrupted feeding being associated with longer LOS.39,40

The large variability of institutional HFNC guidelines6 contributes to difficulty in comparing findings from different institutions, which may explain the mixed results of large systematic reviews regarding HFNC efficacy for bronchiolitis.41,42 43 While direct comparisons are challenging, our findings contribute to the growing literature that protocolized initiation, titration/weaning of HFNC can reduce ICU and hospital LOS without compromising safety.

Limitations

Our QI protocol had several limitations. Notably, we had a relatively low protocol adherence of 66%, likely related to the need for paper charting when the RAC and protocol were not yet embedded into the EHR. The additional work of paper charting for nurses and RTs added to the challenges of completing the protocol and proper documentation. The low adherence may increase the likelihood that the results were due to chance. The fewer hours over-SpO2 target of 95% while FIO2>0.21 in the post-intervention group is an improvement compared to a period without clinical guidelines, but still suggest a need for better protocol adherence. Since the conclusion of this project, RAC and the HFNC protocol have been embedded into the EHR, which improved charting efficiency and may improve adherence.

Our RAC score is limited by lack of validity and subjectivity of work of breathing and mental status. Since conceptualizing this study, a new critical bronchiolitis score (CBS) was developed based on VPS data and outperformed other scores including PIM-3 in predicting ICU LOS.44 Advantages of CBS include objective data, bronchiolitis-specific variables, and may be a better predictor of illness severity for bronchiolitis given the low mortality. However, the inclusion of laboratory values (i.e., blood gas, chemistry, and viral) in the CBS is contrary to best practice guidelines to limit laboratory testing in patients with bronchiolitis. While CBS will serve as a good research tool going forward, a score like RAC may have more clinical utility.

While we tried to minimize confounding results by having no other medication or equipment changes, it is possible that the development of the QI team and HFNC protocol created more streamlined care for bronchiolitis that may have impacted outcomes even before our first PDSA cycle. It is possible that patients in the post-protocol group were less likely to have HFNC started for a mild RAC and thus our post-protocol patients may have been sicker for those in which HFNC was initiated, which would have biased our findings towards the null hypothesis. Unfortunately, we also were not able to compare the degree of illness at time of HFNC initiation between the two groups.

Our QI effort was limited to a relatively small sample size predominately from a single respiratory season in the intervention timeframe, due to the COVID19 pandemic that decreased bronchiolitis admissions nationally.45,46 Notably, we had small monthly samples and there are months in which we had few patients with bronchiolitis, but these were excluded in the SPC charts. Generally, the smaller sample size would bias the results towards the null given the high degree of heterogeneity in bronchiolitis. However, we were still able to identify statistically significant benefits from our interventions. Lastly, adherence to social distancing prevented the ability to conduct QI rounds after March 2020. However, there continued to be decrease in mean LOS for patients with bronchiolitis after the intervention period through 202212, suggesting that the effects of this project were sustained.

Conclusions

Implementation of an evidence based HFNC protocol with standardized initiation/weaning flow rates and SpO2 target range was associated with decreased hospital LOS and ICU LOS and, months later, a shorter duration of HFNC treatment without an increase in ICU readmission or escalation of respiratory support. QI interventions facilitated improved adherence to recommended bronchiolitis SpO2 targets.

Supplementary Material

Information Boxes.

“Research in Context”

Bronchiolitis is the most common cause of non-elective US pediatric hospitalizations in children <1 year old.

HFNC therapy is becoming a more common non-invasive modality for treatment of bronchiolitis.

Increased utilization of HFNC therapy for bronchiolitis necessitates implementation of standardized management with clear initiation and weaning guidelines to minimize overuse and unnecessary healthcare utilization.

“At the Bedside”

A QI initiative to standardize HFNC initiation and weaning practices for patients with bronchiolitis resulted in decreased hospital and ICU LOS and HFNC duration.

QI interventions facilitated improved adherence to recommended bronchiolitis guidelines.

Targeted oxygen saturation for management of bronchiolitis reduces excessive oxygen therapy, although more research on the optimal range of oxygen saturation is still indicated.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank other members that played a role in developing and implementing the HFNC protocol: Alexis Toney, Courtney Welch, Elizabeth Wood, Eunice Kim, Kendra Leigh Grether-Jones, Tisha Yeh, Su-Ting Li, and Nicki Campbell; our PICU nurse practitioners; and Jason Y. Adams and other members of the UC Davis Health Data Provisioning Core.

Funding/Support:

This project was made possible due to a UC Davis Children’s Hospital Employee and Donor Gift fund to the PICU and an institution resident research grant. Dr. Siefkes was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), through grant number UL1 TR001860 and linked award KL2 TR001859. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The NIH had no role in the design or oversight of the study. The project described was supported by the NCATS, NIH, through grant UL1 TR000002.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures (includes financial disclosures)

The authors have indicated that they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ralston SL, Lieberthal AS, Meissner HC, et al. Clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis, management, and prevention of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):e1474–e1502. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujiogi M, Goto T, Yasunaga H, et al. Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States: 2000–2016. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton JA, McKee B, Slain KN, Rotta AT, Shein SL. Outcomes of children with bronchiolitis treated with high-flow nasal cannula or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(2):128–135. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kepreotes E, Whitehead B, Attia J, et al. High-flow warm humidified oxygen versus standard low-flow nasal cannula oxygen for moderate bronchiolitis (HFWHO RCT): an open, phase 4, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):930–939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30061-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franklin D, Babl FE, Schlapbach LJ, et al. A Randomized Trial of High-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Infants with Bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1121–1131. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1714855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalburgi S, Halley T. High-Flow Nasal Cannula Use Outside of the ICU Setting. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-4083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bressan S, Balzani M, Krauss B, Pettenazzo A, Zanconato S, Baraldi E. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen for bronchiolitis in a pediatric ward: A pilot study. Eur J Pediatr. 2013;172(12):1649–1656. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2094-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davison M, Watson M, Wockner L, Kinnear F. Paediatric high-flow nasal cannula therapy in children with bronchiolitis: A retrospective safety and efficacy study in a non-tertiary environment. EMA - Emerg Med Australas. 2017;29(2):198–203. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins C, Chan T, Roberts JS, Haaland WL, Wright DR. High-Flow Nasal Cannula in Bronchiolitis: Modeling the Economic Effects of a Ward-Based Protocol. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(8):451–459. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyenaar JAK, Ralston SL. Widespread Adoption of Low-Value Therapy: The Case of Bronchiolitis and High-Flow Oxygen. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-021188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treasure JD, Hubbell B, Statile AM. Enough Is Enough : Quality Improvement to Deimplement High-Flow Nasal Cannula in Bronchiolitis. 2021. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-005306 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Vizient Clinical Data Base®, Vizient Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn M, Zorc J, Tyler L, Devon E, McAndrew L, Leach K. Inpatient Clinical Pathway for Evaluation/Treatment of Children with Bronchiolitis, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/bronchiolitis-inpatient-treatment-clinical-pathway. Published 2013.

- 14.Provost L, Murray S. The Health Care Data Guide: Learning from Data for Improvement. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture ( REDCap )— A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, et al. Paediatric index of mortality 3: An updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(7):673–681. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829760cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, et al. Paediatric index of mortality 3: an updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(7):673–681. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829760cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riese J, Fierce J, Riese A, Alverson BK. Effect of a Hospital-wide High-Flow Nasal Cannula Protocol on Clinical Outcomes and Resource Utilization of Bronchiolitis Patients Admitted to the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(12). doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2014-0220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slain KN, Malay S, Shein SL. Hospital Charges Associated With Critical Bronchiolitis From 2009 to 2019. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2022;23(3):171–180. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franklin D, Schibler A. Rising Intensive Care Costs in Bronchiolitis Infants-Is Nasal High Flow the Culprit? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2022;23(3):218–222. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linssen RS, van Woensel JBM, Bont L, et al. Are changes in practice a cause of the rising burden of bronchiolitis for paediatric intensive care units? Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(10):1094–1096. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00367-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Cleve WC, Christakis DA. Unnecessary care for bronchiolitis decreases with increasing inpatient prevalence of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ralston SL, Garber MD, Rice-Conboy E, et al. A multicenter collaborative to reduce unnecessary care in inpatient bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralston S, Comick A, Nichols E, Parker D, Lanter P. Effectiveness of quality improvement in hospitalization for bronchiolitis: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):571–581. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noelck M, Foster A, Kelly S, Arehart A, Rufener C, Wagner T. RESEARCH ARTICLE SCRATCH Trial : An Initiative to Reduce Excess Use of High-Flow Nasal Cannula. 2021;11(4). doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-003913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charvat C, Jain S, Orenstein EW, Miller L, Edmond M, Sanders R. Quality Initiative to Reduce High-Flow Nasal Cannula Duration and Length of Stay in Bronchiolitis. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(4):309–318. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-005306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson RJ, Hassumani DO, Hole AJ, Slaven JE, Tori AJ, Abu-Sultaneh S. Implementation of a High-Flow Nasal Cannula Management Protocol in the Pediatric ICU. Respir Care. 2021;66(4):591–599. doi: 10.4187/RESPCARE.08284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betters KA, Hebbar KB, Mccracken C, Heitz D, Sparacino S, Petrillo T. A Novel Weaning Protocol for High-Flow Nasal Cannula in the PICU. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001181 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Turnham H, Agbeko RS, Furness J, Pappachan J, Sutcliffe AG, Ramnarayan P. Non-invasive respiratory support for infants with bronchiolitis: A national survey of practice. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1). doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0785-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sokuri P, Heikkilä P, Korppi M. National high-flow nasal cannula and bronchiolitis survey highlights need for further research and evidence-based guidelines. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 2017;106(12):1998–2003. doi: 10.1111/apa.13964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franklin D, Babl FE, Schlapbach LJ, et al. A Randomized Trial of High-Flow Oxygen Therapy in Infants with Bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1121–1131. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1714855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riese J, Porter T, Fierce J, Riese A, Richardson T, Alverson BK. Clinical Outcomes of Bronchiolitis After Implementation of a General Ward High Flow Nasal Cannula Guideline. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(4):197–203. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuh S, Freedman S, Coates A, et al. Effect of Oximetry on Hospitalization in Bronchiolitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2014;312(7):712–718. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2014.8637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jetty R, Harrison MA, Momoli F, Pound C. Practice variation in the management of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis: A Canadian perspective. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;24(5):306–312. doi: 10.1093/PCH/PXY147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unger S, Cunningham S. Effect of Oxygen Supplementation on Length of Stay for Infants Hospitalized With Acute Viral Bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):470–475. doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2007-1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunningham S, McMurray A. Observational study of two oxygen saturation targets for discharge in bronchiolitis. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(4):361–363. doi: 10.1136/ADC.2010.205211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroeder AR, Marmor AK, Pantell RH, Newman TB. Impact of pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy on length of stay in bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(6):527–530. doi: 10.1001/ARCHPEDI.158.6.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sochet AA, McGee JA, October TW. Oral Nutrition in Children With Bronchiolitis on High-Flow Nasal Cannula Is Well Tolerated. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(5):249–255. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slain KN, Martinez-Schlurmann N, Shein SL, Stormorken A. Nutrition and High-Flow Nasal Cannula Respiratory Support in Children With Bronchiolitis. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(5):256–262. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayfield S, Jauncey-Cooke J, Hough JL, Schibler A, Gibbons K, Bogossian F. High-flow nasal cannula therapy for respiratory support in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(3). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009850.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beggs S, Wong ZH, Kaul S, Ogden KJ, Walters JAE. High-flow nasal cannula therapy for infants with bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(1). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009609.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clayton JA, McKee B, Slain KN, Rotta AT, Shein SL. Outcomes of children with bronchiolitis treated with high-flow nasal cannula or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(2):128–135. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mount MC, Ji X, Kattan MW, et al. Derivation and Validation of the Critical Bronchiolitis Score for the PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2022;23(1):E45–E54. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Partridge E, McCleery E, Cheema R, et al. Evaluation of Seasonal Respiratory Virus Activity Before and After the Statewide COVID-19 Shelter-in-Place Order in Northern California. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2035281. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilder Jayne L.; Parsons Chase R.; Growdon Amanda S.; Toomey Sara L.; Mansach JM. Pediatric Hospitalizations During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.