Abstract

Objective

Increased apoptotic shedding has been linked to intestinal barrier dysfunction and development of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). In contrast, physiological cell shedding allows the renewal of the epithelial monolayer without compromising the barrier function. Here, we investigated the role of live cell extrusion in epithelial barrier alterations in IBD.

Design

Taking advantage of conditional GGTase and RAC1 knockout mice in intestinal epithelial cells (Pggt1b iΔIEC and Rac1 iΔIEC mice), intravital microscopy, immunostaining, mechanobiology, organoid techniques and RNA sequencing, we analysed cell shedding alterations within the intestinal epithelium. Moreover, we examined human gut tissue and intestinal organoids from patients with IBD for cell shedding alterations and RAC1 function.

Results

Epithelial Pggt1b deletion led to cytoskeleton rearrangement and tight junction redistribution, causing cell overcrowding due to arresting of cell shedding that finally resulted in epithelial leakage and spontaneous mucosal inflammation in the small and to a lesser extent in the large intestine. Both in vivo and in vitro studies (knockout mice, organoids) identified RAC1 as a GGTase target critically involved in prenylation-dependent cytoskeleton dynamics, cell mechanics and epithelial cell shedding. Moreover, inflamed areas of gut tissue from patients with IBD exhibited funnel-like structures, signs of arrested cell shedding and impaired RAC1 function. RAC1 inhibition in human intestinal organoids caused actin alterations compatible with arresting of cell shedding.

Conclusion

Impaired epithelial RAC1 function causes cell overcrowding and epithelial leakage thus inducing chronic intestinal inflammation. Epithelial RAC1 emerges as key regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics, cell mechanics and intestinal cell shedding. Modulation of RAC1 might be exploited for restoration of epithelial integrity in the gut of patients with IBD.

Keywords: actin cytoskeleton, IBD, epithelial barrier, intestinal epithelium, tight junction

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Epithelial barrier function contributes to maintenance of gut tissue homeostasis and avoids intestinal inflammation.

Pathological cell shedding is associated to alterations of epithelial integrity in the context of chronic intestinal inflammation.

Although physiological cell shedding controls epithelial cell numbers in order to maintain epithelial integrity, little is known about its involvement in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathogenesis.

What are the new findings?

Epithelial intrinsic alterations in GGTase and/or RAC1-deficient epithelium cause barrier breakdown and intestinal inflammation.

Cytoskeleton rearrangement and altered cell mechanics in GGTase and RAC1-deficient epithelium lead to arresting of cell shedding and cell overcrowding.

Signs of arresting of physiological cell shedding and overcrowding in intestinal tissue from patients with IBD on inflammation.

Epithelial RAC1 function is modulated specifically in the epithelial surface of intestinal tissue from patients with IBD.

Significance of this study.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

RAC1 function within intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) might be exploited in the context of epithelial restoration for the diagnosis and/or treatment of patients with IBD.

Epithelial cell mechanics alterations could be used for the identification of epithelial leakage in IBD and even for the prediction of flares.

Pharmacological inhibition of RAC1 in patients with IBD could have a deleterious effect on epithelial integrity.

Introduction

In inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), chronic gut inflammation is due to an exacerbated response against the microbiota.1 2 Thus, epithelial leakage is a hallmark feature in patients with IBD.3 4 Increased intestinal permeability in patients in remission5 and relatives,6 7 and IBD-like phenotypes in monogenic diseases affecting epithelial proteins,8 9 evoke epithelial disruption as aetiological factor in IBD pathogenesis.

The renewal of the intestinal epithelium requires a tight regulation between cell extrusion and proliferation, controlling cell numbers and barrier integrity.10 Cell shedding is intimately connected to cell death; caspase activation occurs prior to shedding in apoptotic cell extrusion,11 or on loss of survival signals due to the detachment of live cells.12 Also, cell shedding acts as a defence mechanism to get rid of infected13 or mutated14 cells. Defective apical extrusion contributes to aggressive tumour hallmarks,15 and basal extrusion leads to tumour dissemination and metastasis.16

Confocal endomicroscopy studies demonstrated the correlation between excessive apoptotic cell shedding, permeability defects and intestinal inflammation.4 17 18 However, little is known about the role of physiological cell shedding in IBD. On Piezo1-driven mechanosensations,19–21 S1PR2-mediated Rho-dependent acto-myosin contractility causes single live cell extrusion.22 23 Readjustment of tight junctions (TJs) restricts the temporary epithelial leakage in physiological24 and pathological11 cell shedding. Thus, TJ assembly and cytoskeleton dynamics control intestinal permeability,25 and their alterations may favour barrier disruption and inflammation. Accordingly, changes in the continuity/number of TJ strands have been observed in Crohn’s disease26 and ulcerative colitis.27 Also, mice with an epithelial deficiency of proteins involved in cytoskeleton function elicited increased susceptibility to colitis.28 29

Intimately associated to the cytoskeleton, small Rho GTPases regulate epithelial barrier function30 and are critically involved in epithelial gap closure.22 31–33 Post-translational prenylation allows the anchoring of small GTPases to the cell membrane and their function. We previously demonstrated a link between GGTase1-prenylation of Rho proteins, epithelial integrity and inflammation.34 In this study, we found that abrogated expression of GGTase1 within IECs, primary resulted in cytoskeleton rearrangement and apical junction complex (AJC) protein redistribution causing cell shedding arresting, leading to epithelial leakage and activation of local immune responses. RAC1 emerged as a GGTase-target critically involved in epithelial cytoskeleton dynamics and cell mechanics, whose alterations in IBD play a key role in arrested cell shedding and barrier dysfunction. These findings open new avenues for therapeutic modulation of epithelial restoration in IBD.

Methods

Methods are outlined in the online supplemental material 1.

gutjnl-2021-325520supp001.pdf (207.3KB, pdf)

Results

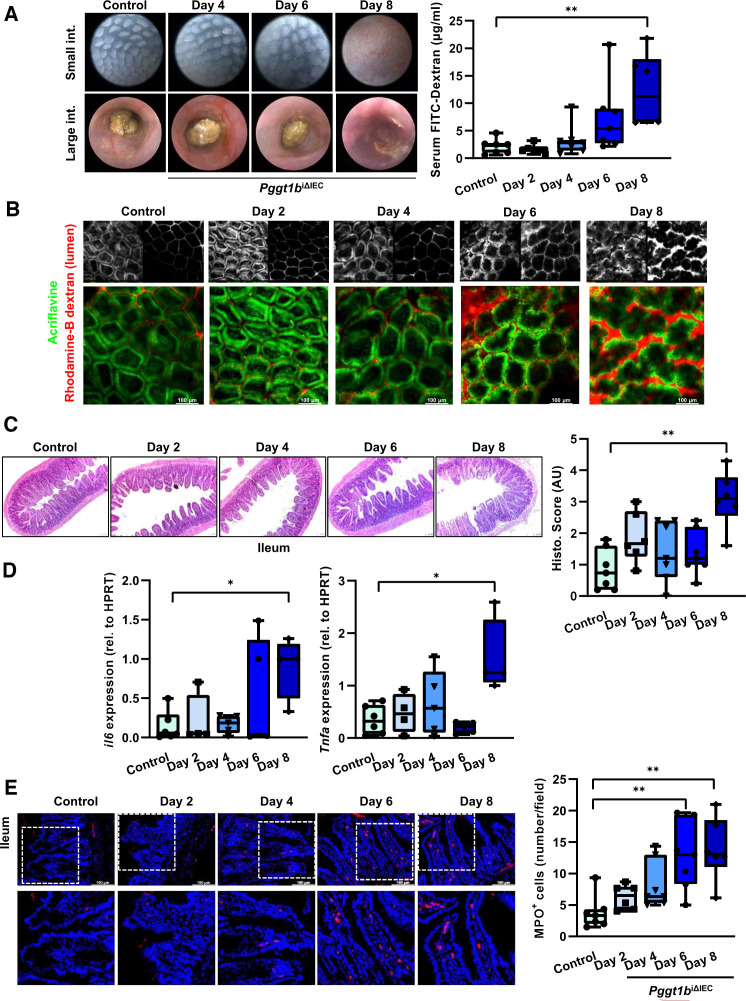

Kinetics of barrier alterations and intestinal pathology in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice

To determine the functional effects and sequence of molecular events of inducible inhibition of prenylation within IECs, we analysed intestinal pathology in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice over time. Deletion of Pggt1b gene occurred 2 days on tamoxifen treatment, leading to decreased GGTase1 expression, and accumulation of non-prenylated proteins in ileum tissue and isolated IECs (online supplemental figure 1). Although we could not detect any macroscopic sign of intestinal tissue alteration at day 6 (high resolution endoscopy), we could observe a trend to increased intestinal permeability occurring between days 4 and 6 (figure 1A). Accordingly, passage of luminal dextran in the small intestine could be detected via intravital microscopy already at day 4 (figure 1B). In contrast, complete mucosal architecture destruction in ileum and duodenum could only be seen at later time points leading to marked suppression of barrier function (day 8), while only mild alterations could be observed in the large intestine (figure 1C; online supplemental figure 1). Concerning the potential inflammatory response in the intestine of Pggt1b iΔIEC mice, we could observe increased IL-6 and TNF-α expression in ileum and duodenum only at late time points (day 8), but not in the colon (figure 1D; online supplemental figure 1), while infiltration of MPO+ neutrophils was evident already at day 6 in ileum (figure 1E; online supplemental figure 1). These data demonstrated epithelial intrinsic phenomena on Pggt1b deletion leading to permeability defects and early infiltration of neutrophils and supported the initial hypothesis of epithelial barrier defects as cause of intestinal pathology due to abolished GGTase-mediated prenylation within IECs. Based on the severity, we focused in subsequent studies on the phenotype affecting the small intestine of Pggt1b iΔIEC mice.

Figure 1.

Intestinal disease due to inhibition of prenylation within IECs over time. (A) Assessment of tissue integrity in vivo/ ex vivo and intestinal permeability in vivo. Endoscopy pictures of colon and small intestine tissue (left); transmucosal passage of orally administered FITC-Dextran (4 KDa); serum concentration (µg/mL) (right). (B) Representative pictures of intravital microscopy analysis of barrier function of small intestine using luminal acriflavine (green) and rhodamineB-dextran (red). (Control, n=8; day 2, n=6; day 4, n=5; day 6, n=5; day 8, n=2). (C) Histology analysis of ileum tissue using H&E staining. Representative pictures (left), and corresponding score (right). (D) Gene expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in ileum tissue (RT-qPCR; six independent experiments). (E) MPO immunofluorescence staining in cross-sections from ileum. Representative pictures (left), and corresponding quantification (right). Data are expressed as box-plots (Min to Max); seven independent experiments, except where indicated. One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *P≤0.050; ** P≤0.001. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

gutjnl-2021-325520supp002.pdf (34.1MB, pdf)

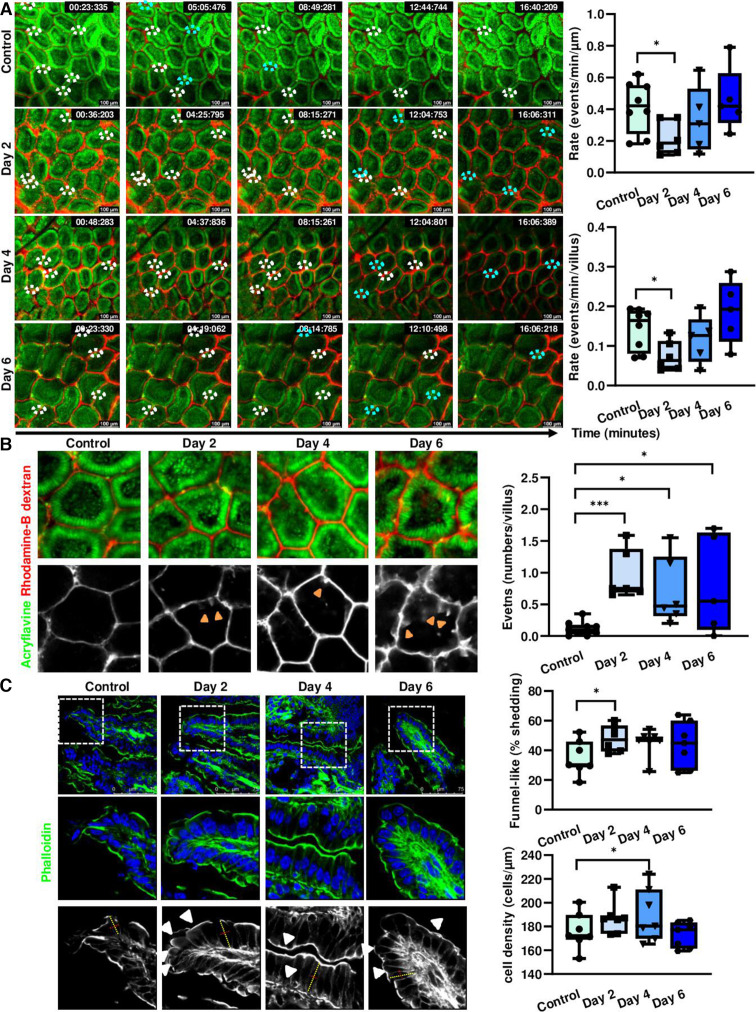

Arresting of cell shedding and cell overcrowding in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice

Considering the previously described intestinal phenotype observed in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice,34 we analysed cell shedding on tamoxifen-induced pggt1b-deletion over time, to identify early epithelial intrinsic alterations. Taking advantage of intravital microscopy,35 we could demonstrate that cell shedding rate in small intestine was significantly decreased at early time points after Pggt1b deletion (Day 2) (figure 2A), coinciding with the initial accumulation of ‘permeable IECs’ (figure 2B). These data supported that early cell shedding alterations critically contribute to the intestinal phenotype in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice and pointed towards impaired or ‘arrested’ cell shedding. As previous publications described the appearance of funnel-like shaped cells as an early event during cell extrusion occurring due to the basolateral pressure of neighbouring cells,24 the accumulation of these funnel-like structures can be interpreted as a surrogate of impaired cell extrusion. In addition to E-cadherin and/or ZO-1 redistribution,24 funnel-like structures could be identified by actin redistribution (phalloidin staining) (online supplemental figure 2). Interestingly, funnel-like structures showing partially extruded IECs accumulated in ileum tissue on day 2 on Pggt1b deletion (figure 2C), correlating to a shift between arrested and completed cell shedding events (days 2 and 4) (online supplemental figure 2). The accumulation of partially extruded cells could lead to cell overcrowding, causing squeezing and altered cell shape due to increased pressure from neighbouring cells.36 We thus wondered whether we could observe overcrowding in the epithelium of Pggt1b iΔIEC mice. Increased cell density (cells/length of basement membrane) could be observed on inhibition of GGTase-mediated prenylation within IECs in ileum (figure 2C). This went along with significantly increased cell length (day 2) and length/diameter ratio (day 4) consistent with cell squeezing due to overcrowding (online supplemental figure 2). To confirm the shape alterations in GGTase-deficient IECs, we performed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of ileum tissue. Elongated (increased length) and squeezed (decreased diameter) cells could be observed 2 days on tamoxifen deletion (figure 3). This is associated with enlarged apical actin network and altered AJC (figure 3). Taking together, these data suggest an early arresting of cell shedding on deletion of Pggt1b within IECs, leading to cell overcrowding.

Figure 2.

Cell shedding alterations and overcrowding in GGTase-deficient small intestine (time course study). (A, B) Intravital microscopy analysis of cell shedding using luminal acriflavine (green) and rhodamineB-dextran (red). (Control, n=8; day 2, n=6; day 4, n=5; day 6, n=5). Multiple unpaired t-test (A) Representative pictures of time sequences; white ellipses indicate cell shedding events in progress; turquoise ellipses indicate completed cell shedding events, cell is shown to be in the lumen, out of the epithelial layer. In some cases, the Z-position has been corrected based on changes in the focus plane during image acquisition due to tissue contraction or peristalsis. Quantification of cell shedding rate considering exclusively events which are completed during the duration of the image acquisition; (number of cell shedding events/time/length) (top), and in a single villus (events/minute) (bottom), at a determined focus plane near the lumen (five villi/video; two videos/mouse). (B) Representative pictures of single villus from intravital microscopy experiment (left); orange arrows indicate permeable cells. Quantification of permeable cells (dextran is detected inside the cell) (events/villus; 10 villi/picture; two pictures/mouse). (C) F-actin fibre staining using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin in ileum tissue (green). Seven independent experiments. Mixed effect analysis. Representative pictures (left); quantification of funnel-like structures, indicated by white arrows (top right); quantification of cell density (number of cells/µm of basement membrane length) (bottom right). Data are expressed as box-plots (Min to Max). *P≤0.050; ***P≤0.0001.

Figure 3.

TEM analysis of ileum tissue from control and Pggt1b iΔIEC mice (days 2 and 4). Quantification of cell diameter and cell length/diameter ratio (left); representative pictures (right). Cell shape is indicated by dotted turquoise lines; red arrows indicate cell diameter (between two lateral membranes) and yellow arrows indicate cell length (between basal and apical membrane). Within the AJC, tight junction zone is indicated by red asterisks, while yellow asterisks indicate Adherens junction zone. One sample/group. Data are expressed as box-plots (Min to Max). *P≤0.050. AJC, apical junction complex; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

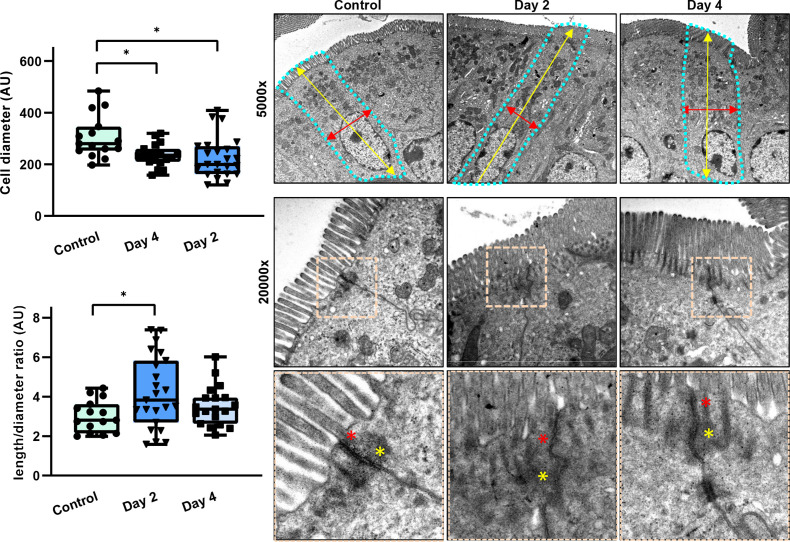

Cytoskeleton rearrangement and altered cell mechanics in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice

We then aimed at the description of the molecular mechanism behind this impaired cell shedding. Completion of physiological cell shedding depends on S1P-mediated cell communication.22 Since expression of S1P2R was not significantly altered in ileum tissue from Pggt1b iΔIEC mice (online supplemental figure 3), we assumed that this signalling checkpoint is not impaired on prenylation inhibition. Next, the closure of epithelial gaps depends on acto-myosin contractility, involving actin purse-string and cell crawling from the neighbouring cells.37 In accordance with the TEM analysis (figure 3), high resolution Stellaris confocal microscopy confirmed the alteration of actin cytoskeleton within IECs located at the villus tip in ileum from Pggt1b iΔIEC mice: enlarged apical actin network and redistribution of fibres (figure 4A). We then analysed myosin structure and could observe that MyosinIIA signal is typically stronger in ileum IECs located at the villus tip in control mice (figure 4B), where physiological cell shedding occurs. However, early on deletion of Pggt1b (days 2–4), this signal was equally distributed throughout the villus down to the crypt base (figure 4B). Together, we detected an early acto-myosin redistribution on inhibition of prenylation within IECs.

Figure 4.

Cytoskeleton rearrangement and altered cell mechanics in small intestine on deletion of Pggt1b. (A) F-actin fibre staining using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin in ileum tissue (green). High resolution confocal microscopy (Leica Stellaris). Representative pictures of a maximum projection (system optimised z-stack). Yellow arrows indicate apical actin network; orange arrows indicate redistribution of actin fibres. Three independent experiments. (B) Representative pictures of Myosin IIA staining (red) in ileum tissue (five independent experiments). Confocal microscopy (Leica SP8). (C) RT-FDC analysis from small intestine IECs (n=4/group). (D) Expression and redistribution of selected candidate AJC proteins in ileum tissue (claudin-1, claudin-2 and E-cadherin). Immunostaining (top, red signal) and western blot (bottom). Band densitometry quantification (right). Minimum five independent experiments. Data are expressed as box-plots (Min to Max). One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *P≤0.050. AJC, apical junction complex; ANOVA, analysis of variance; RT-FDC, real time fluorescence deformability cytometry.

As cytoskeleton rearrangement and ‘squeezed’ cell shape suggested that GGTase-deficient IECs have also altered cell mechanics, we analysed freshly isolated IECs from the small intestine via real time fluorescence deformability cytometry (RT-FDC).38 We found that shortly on Pggt1b deletion (day 3), GGTase-deficient IECs (EpCAM+CD45-) are characterised by a decreased Young’s modulus, indicative of an increased deformability (figure 4C; online supplemental figure 3). These observations are in agreement with cell-intrinsic phenomena (cytoskeleton alterations) leading to alterations of mechanical properties of individual cells (RT-FDC data), potentially contributing to epithelial leakage in mice carrying GGTase-deficient epithelium.

Redistribution of TJs proteins significantly contributes to the sealing of the epithelial layer on cell extrusion.11 Alterations on the AJC could be observed in GGTase-deficient epithelium via TEM (figure 3), In order to describe alterations on intercellular junction proteins impairing completion of cell shedding, we screened for the expression of up to 25 proteins in ileum tissue. Regulated expression of genes encoding for claudin proteins (-1 to -2, and -8), occludin and ZO-1; as well as E-cadherin and β-catenin (online supplemental figure 3) suggested potential changes of TJ and AJ on deletion of Pggt1b. Intercellular junction protein function is critically determined by their subcellular localization and interaction with the cytoskeleton.39 Indeed, at early time points (days 2–4) we could detect redistribution of claudin-2, claudin-8, claudin-18, E-cadherin and β-catenin (increased signal) at the villus tip, as well as diminished staining for claudin-1 and ZO-1 in ileum cross-sections; regulated protein expression could be confirmed via WB for claudin-2, claudin-8 and ZO1 (day 3) (figure 4D; online supplemental figure 3). Among alterations within the AJC occurring shortly on Pggt1b deletion, some changes can be reverted (days 4–6), such as the downregulation of ZO1 or upregulation of claudin-2, while other changes persisted over time, such as decreased claudin-1 or increased expression of claudin-18, E-cadherin or β-catenin. In fact, redistribution of E-cadherin confirmed the accumulation of funnel-like structures (online supplemental figure 2). Together, our data showed cytoskeleton rearrangement, cell shape and mechanics alterations and AJC protein redistribution in IECs from Pggt1b iΔIEC mice.

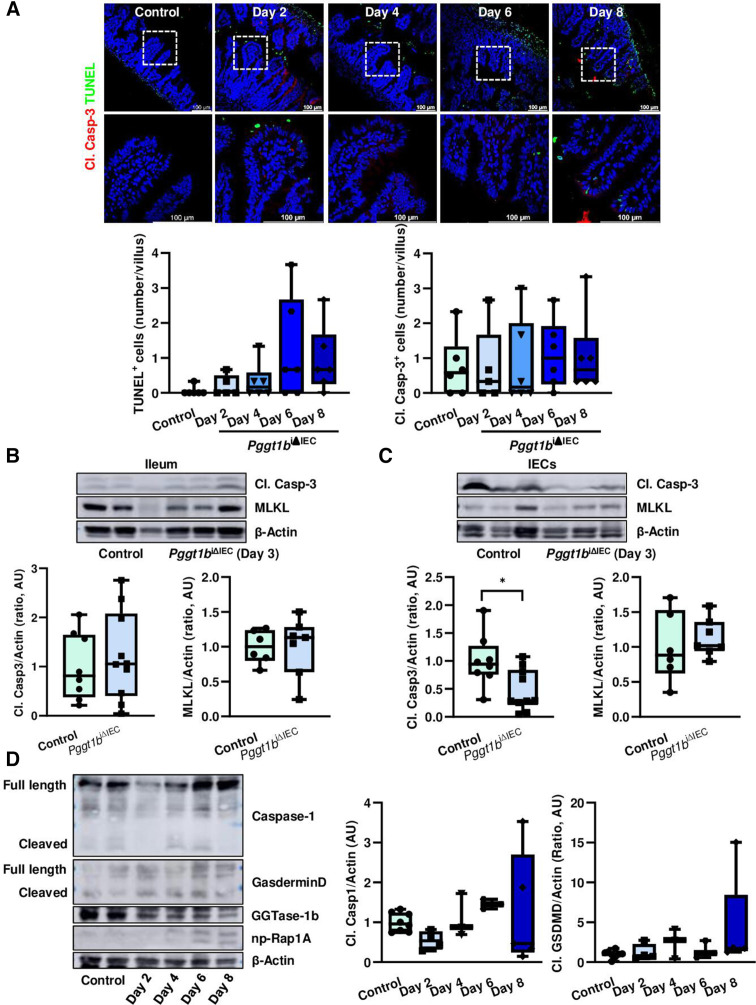

Intestinal pathology in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice is not primarily caused by caspase-mediated pathological cell shedding

Epithelial leakage in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice can be considered as a consequence of cytoskeleton rearrangement and TJ disassembly. However, the appearance of permeable IECs could be caused by cell death.40 41 To determine whether arresting of cell shedding in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice is associated to modulation of cell death, we studied its kinetics on Pggt1b deletion. No significant changes in total cell death (TUNEL+ cells) or cleaved caspase-3+ cells were observed in the ileum of Pggt1b iΔIEC mice over time (figure 5A). Despite this, a clear trend towards accumulation of dead cells could be observed at late time points, when epithelial integrity was disrupted. Moreover, the analysis of cleaved caspase-3 activation within dying cells indicated a potential shift between apoptosis (TUNEL+ Casp3+) and non-apoptotic death (TUNEL+ Casp3-) (online supplemental figure 4). Accordingly, we could observe decreased cleavage of caspase-3 in small intestine IECs early on Pggt1b deletion (day 3) (figure 5B, C). These observations suggested that induction of cell death (pathological cell extrusion) might not be involved in the initial events leading to the intestinal phenotype and cell shedding alterations on inhibition of GGTase-prenylation, but might occur as an amplifying event which further aggravates tissue damage at late time points. We then wondered whether necroptosis, as an alternative cell death pathway is operating in the absence of GGTase within IECs. However, despite induced gene expression of mlkl in the ileum of Pggt1b iΔIEC mice over time (online supplemental figure 4), we could not detect increased MLKL protein expression at early time points (figure 5B, C). It has been recently suggested that Gasdermin-E-dependent pyroptotic cell death plays a relevant role on cell extrusion.42 Considering other alternative cell death pathways linked to membrane integrity disruption, we have also analysed activation of pyroptosis41 in small intestine from Pggt1b iΔIEC mice. Regulated gene expression of Gasdermin-D and Gasdermin-E could not be detected at any time point on GGTase deletion (online supplemental figure 4). However, small intestine tissue destruction at late time is associated with cleavage of Caspase-1 and Gasdermin-D within IECs, indicating activation of pyropototic cell death as a secondary mechanism (figure 5D). Thus, impaired caspase-3 expression or direct inhibition of apoptosis as well as the potential activation of an alternative cell death pathway (necroptosis and/or pyroptosis) might be considered as a secondary mechanism on cytoskeleton rearrangement in GGTase-deficient epithelium. Considering the intimate regulation between cell death and extrusion, further studies are needed in order to decipher the link between cytoskeleton rearrangement and altered cell mechanics and modulation of apoptosis and/or pyroptosis.

Figure 5.

Cell death activation on inhibition of prenylation within small intestinal epithelium. (A) TUNEL (green) and cleaved caspase-3 (red) staining in ileum cross-sections from control and Pggt1b iΔIEC mice at different time points. Representative pictures (top) and quantification (bottom) of TUNEL+ (left) and Cl. Casp-3+/villus (right). Six independent experiments. (B, C) Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3 and MLKL. Representative blots (top) and band densitometry quantification (bottom). (B) Ileum tissue (Cl. Casp-3; n=8, control; n=10, Pggt1b iΔIEC) (MLKL; n=6, control; n=7, Pggt1b iΔIEC). (C) Small intestine isolated IECs (Cl. Casp-3; n=8, control; n=10, Pggt1b iΔIEC) (MLKL; n=6, control; n=7, Pggt1b iΔIEC). (D) Detection of Caspase-1 and Gasdermin-D cleavage in small intestine IECs (western blot analysis). Representative blots (left) and band densitometry quantification (right). Four independent experiments. Data are expressed as box-plots (Min to Max). One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (A, D). Unpaired t test (B, C). *P≤0.050.

Besides cell death and extrusion, gut epithelial turnover is determined by stem cell proliferation in crypts and migration of IECs along the crypt/villus axis. Similar to cell death activation and inflammation, decreased proliferation in ileum indicated by significant downregulation of Ki67 expression, could only be observed when tissue destruction is patent (online supplemental figure 4). Taking advantage of BrdU incorporation assays, we could not observe a different migration behaviour of IECs in ileum from Control and Pggt1b iΔIEC mice (online supplemental figure 4). These data confirmed that alteration of cell death, proliferation and migration do not represent primary mechanisms leading to the breakdown of intestinal homeostasis in mice lacking GGTase within IECs.

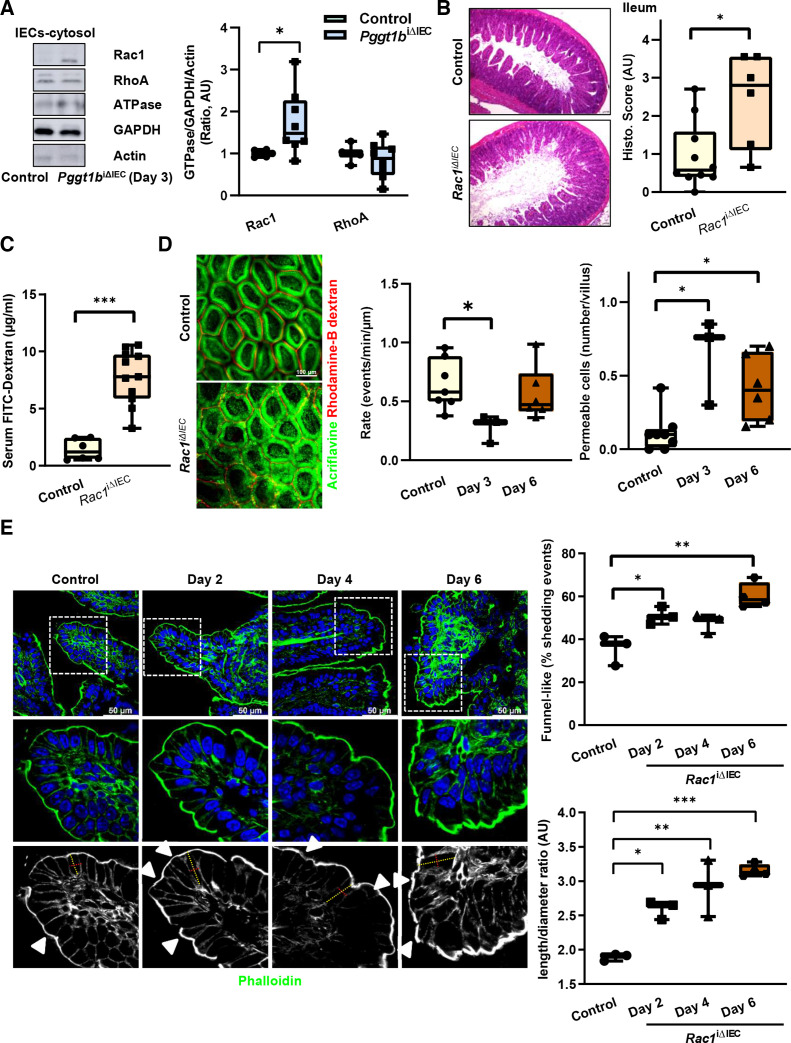

Prenylation targets in cytoskeleton/epithelial cell shedding regulation

Aiming at the identification of prenylation targets whose function is regulated on inactivation of epithelial GGTase, we analysed membrane-bound proteins via MS (day 6). Various prenylated GTPases were downregulated in the membrane fraction from small intestine IECs from Pggt1b iΔIEC mice, such as RAP1A, RHOG, RAP1B and RAC1 (table 1). Based on its function as cytoskeleton regulator and the tight connection to RHOA in the context of epithelial wound closure,43 RAC1 appeared as an attractive candidate for our study. Interestingly, despite unaltered protein expression, an accumulation of RAC1 within the cytosol was noted shortly on deletion of Pggt1b (day 3), suggesting an early dysfunction of this protein in small intestine IECs (figure 6A; online supplemental figure 5). In contrast, no alteration on RHOA at early time points could be observed.

Table 1.

Mass spectrometry analysis of membrane-bound proteins in GGTase-deficient IECs (day 6) (Proteins belonging to small GTPases)

| Symbol | Name | Ratio | Log2ratio (Control/KO) | P value (t-test) |

| Rap1A | Ras-related protein Rap-1a | 4.51474933 | 2.174645888 | 9.0826E−09 |

| RhoG | Rho-related GTP-binding protein RhoG | 2.87985853 | 1.525997941 | 4.4012E−15 |

| Rap1B | Ras-related protein Rap-1b | 1.94032413 | 0.956297677 | 4.4201E−10 |

| Rac1 | Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 | 1.94010883 | 0.95613758 | 1.3254E−07 |

Figure 6.

RAC1 function within small intestine IECs is crucial for the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. (A) Subcellular localisation of RAC1 and RHOA within small intestine IECs from control and Pggt1b iΔIEC mice at day 3 on tamoxifen treatment. Cytosolic proteins are separated via centrifugation gradient and small GTPases are detected via western blotting. Representative blots (left) and band densitometry quantification (right). Three experiments (n=6, control; n=8, Pggt1b iΔIEC). (B–E). Phenotype of Rac1 iΔIEC mice. (B–D) Intestinal pathology and cell shedding alterations in Rac1 iΔIEC mice. (B) Histology analysis of ileum tissue using H&E staining (day 7). Representative pictures (left) and histology score (right) (n=10, control; n=6, Rac1 iΔIEC). (C) Assessment of intestinal permeability in vivo. Transmucosal passage of orally administered FITC-Dextran; serum concentration (µg/mL) (n=6, Control; n=11, Rac1 iΔIEC). (D) Intravital microscopy analysis of cell shedding using luminal acriflavine (green) and rhodamineB-dextran (red) in small intestine. Representative pictures (left); and quantification of cell shedding rate (number of cell shedding events occurring over time in a single villus at a determined focus plane (events/minute/µm), and permeable cells (dextran is detected inside the cell) (events/villus). (n=8, Control; n=3, day 3; n=6, day 6). (E) Time course study. Three independent experiments. F-actin fibre staining using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (green) in ileum tissue. Representative pictures (left); and quantification of funnel-like structures, indicated by white arrows (% of total cell shedding events) (top right); quantification of cell length/diameter ratio (bottom right). One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test or unpaired t test. *P≤0.050; **P≤0.001; ***P≤0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

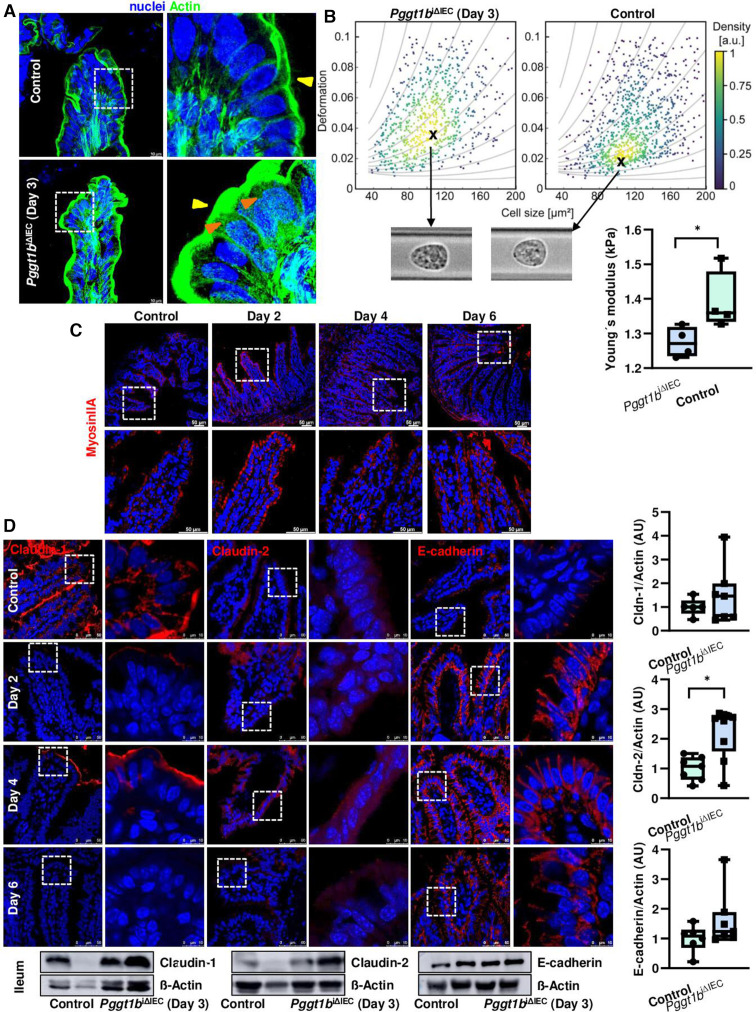

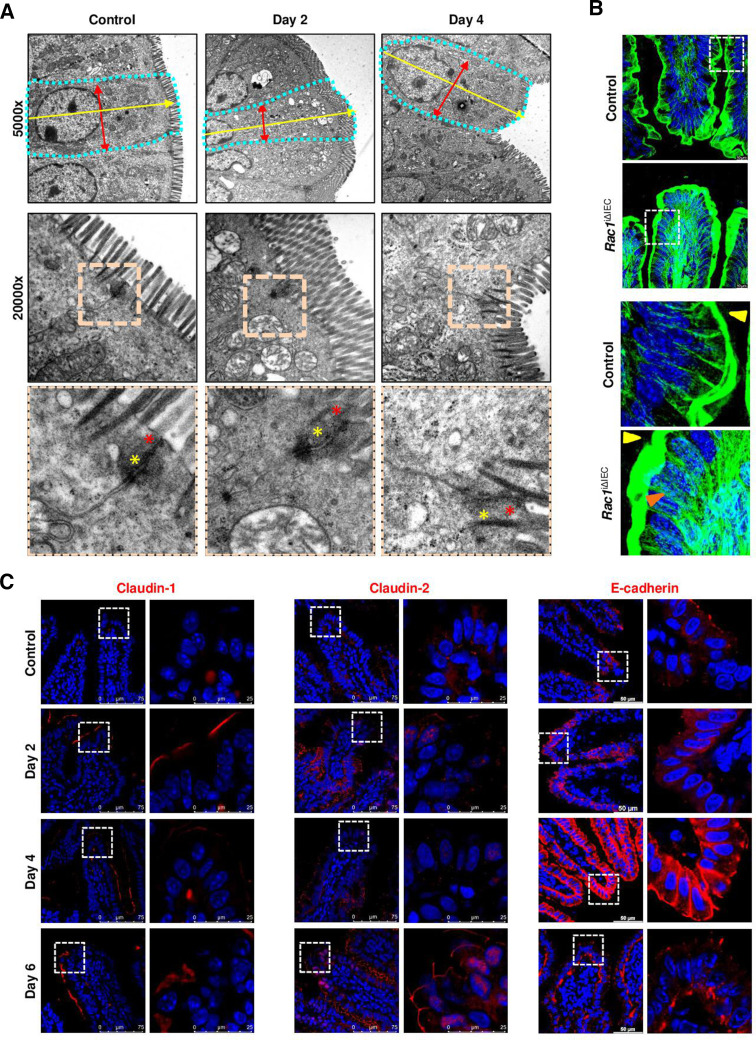

In order to identify the role of RAC1 as GGTase target in the context of epithelial integrity, we generated inducible conditional knockout mice of RAC1 in IECs (Rac1 iΔIEC mice) (online supplemental figure 5). Strikingly, these newly generated mice showed a similar phenotype than Pggt1b iΔIEC mice with intestinal pathology, body weight loss and tissue architecture destruction, affecting specially the small intestine, and being much milder in the case of colon (figure 6B; online supplemental figure 5). Rac1 iΔIEC mice exhibited barrier function breakdown (figure 6C, D), deregulated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in ileum tissue (ie, TNF-α) (online supplemental figure 5), an early decreased cell shedding rate and accumulation of permeable cells in the small intestine (figure 6D). Mechanistically, cell death activation, decreased proliferation or altered cell migration along the crypt-villus axis in ileum could be excluded as primary key mechanisms on inhibition of Rac1 expression within IECs (online supplemental figure 5). Remarkably, we could also observe a decreased cleavage of caspase-3 in Rac1 iΔIEC mice (Day 3), but no regulation of MLKL expression within ileum and small intestine IECs (online supplemental figure 5). We could not detect signs of pyroptotic cell death in RAC-1 deficient IECs over time (online supplemental figure 5). In contrast, signs of cell shedding arresting and overcrowding could be observed in the ileum from Rac1 iΔIEC mice (figure 6E; online supplemental figure 5). TEM analysis of IECs from the ileum confirmed the elongated epithelial cell shape and alterations of AJC (figure 7A). We observed as well a redistribution of actin fibres (figure 7B) and cytosolic accumulation and redistribution of MyosinIIA from the villus tip downwards to the crypt bottom (online supplemental figure 5), mimicking the cytoskeleton rearrangement observed in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice. According to the AJC alterations, early on deletion of rac1, expression of claudin-1, claudin-2, claudin-8, E-cadherin, ZO-1 and β-catenin increased, while claudin-18 shifted from the membrane to the nucleus in ileum IECs (figure 7C; online supplemental figure 5). Altogether, RAC1 is an important target of GGTase within IECs for early cytoskeletal alterations leading to cell shedding arresting.

Figure 7.

Cytoskeleton rearrangement in RAC1-deficient intestinal epithelium. (A) Electron microscopy analysis of ileum tissue. Representative pictures. Cell shape is indicated by dotted turquoise lines; red arrows indicate cell diameter (between two lateral membranes) and yellow arrows indicate cell length (between basal and apical membrane). Within the AJC, tight junction zone is indicated by red asterisks; while yellow asterisks indicate Adherens junction zone. One sample/group. (B) F-actin fibre staining using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (green). High resolution confocal microscopy (Leica Stellaris). Maximum projection (system optimised z-stack). Yellow arrows indicate apical actin network; orange arrows indicate actin fibres. (C) Detection of selected candidate AJC proteins in ileum tissue (claudin-1, claudin-2, E-cadherin). Immunostaining (red signal). Three independent experiments. AJC, apical junction complex.

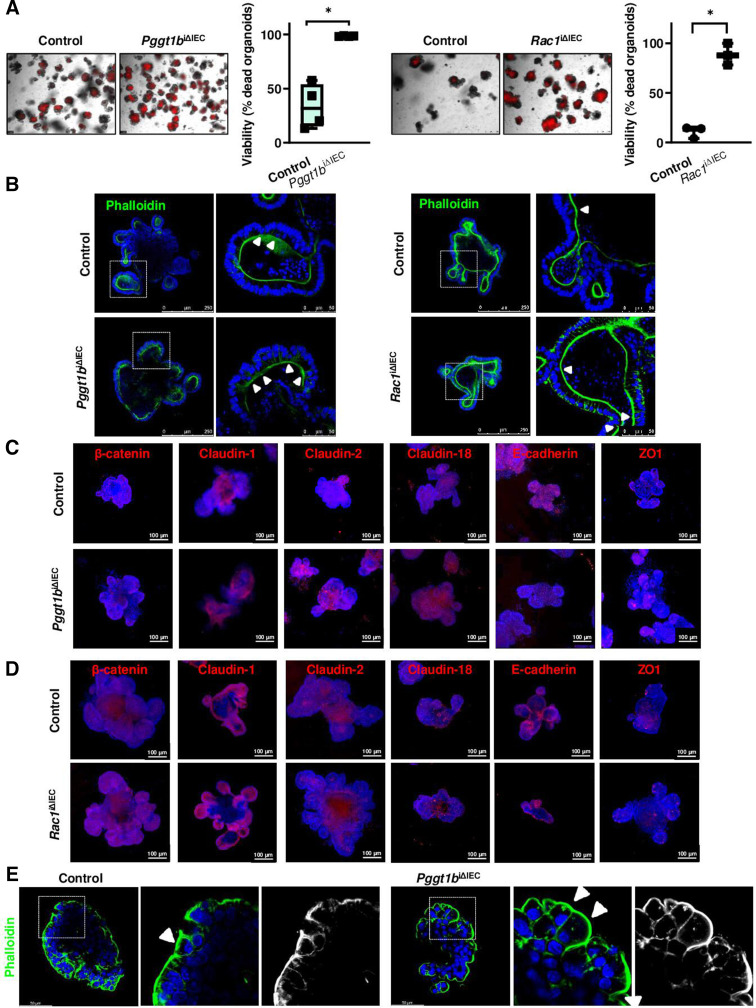

RAC1-dependent epithelial intrinsic mechanisms

To characterise RAC1-dependent epithelial intrinsic mechanisms, we took advantage of small intestinal organoid cultures. Both GGTase-deficient and RAC1-deficient organoids (online supplemental figure 6) showed decreased cell viability (figure 8A), indicating epithelial disruption despite the absence of epithelial-extrinsic mediators. We wondered whether interfering with cell death might impair epithelial disruption in vitro. Epithelial damage was delayed but not fully rescued on treatment with a combination of caspase and necroptosome inhibitors (Z-VAD+Necrostatin-1) in GGTase and RAC1-deficient organoids, while the latter also responded to those inhibitors separately. No effect could be observed on treatment with the pyroptosis inhibitor Disulfiram (online supplemental figure 6). According to our data in vivo (figure 5), these results confirmed the involvement of cell death induction (apoptosis and/or necroptosis) as a contributing but not a major mechanism in epithelial disruption due to GGTase or RAC1 inhibition. Strikingly, cytoskeleton rearrangement on inhibition of GGTase-prenylation or RAC1 also occurred in organoids. Actin fibre redistribution to the lateral and basal membrane goes along with accumulation of funnel-like structures (figure 8B). Moreover, Myosin IIA was shifted towards the cytosol in the absence of GGTase or RAC1 in organoids (online supplemental figure 6). We observed that claudin-2, claudin-18 and β-catenin expression were increased, while E-cadherin was decreased on prenylation inhibition (figure 8C). In RAC1-deficient organoids, we also confirmed increased expression of claudin-2 and β-catenin as well as decreased E-cadherin and ZO-1 expression, while claudin-1 and claudin-18 were not altered (figure 8D). Redistribution of actin fibres was also observed in apical-out organoids, as well as the accumulation of funnel-like structures in GGTase-deficient organoids (figure 8E; online supplemental figure 6). We then wondered whether cell mechanics is changed in those organoids as well. We took advantage of 3D traction force microscopy to quantify organoid-generated contractile forces (contractility or contractile pressure) in collagen-1 gels, measuring the force-induced matrix deformations.44 45 Representative control organoid shows steadily increasing inward-directed matrix deformation, indicative of force increase; whereas representative Pggt1b iΔIEC and Rac1 iΔIEC organoids show outward-directed deformations, indicative of force relaxation (figure 9A–C; online supplemental figure 6). This diverging behaviour started approximately 48 hours after tamoxifen treatment, when the targeted protein is absent and the cell phenotype begins to change (online supplemental figure 6). Together, these data demonstrated altered cell mechanics within GGTase- and RAC1-deficient epithelium (organoid cultures).

Figure 8.

Epithelial intrinsic mechanisms in small intestine organoids. GGTase-deficient and RAC1-deficient organoids generated from small intestinal crypts. (A) Cell viability measured by PI incorporation (red). Representative pictures (left), and corresponding quantification (% of dead organoids) (right). (Pggt1b, four experiments; Rac1, 3 experiments). (B) F-actin fibre staining using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (green) (Pggt1b, five experiments; Rac1, four experiments). White arrows indicate funnel-like structures or arrested cell shedding events. (C, D). Analysis of candidate AJC proteins by immunostaining. Maximum projection from z-stacks (system optimised). (C) GGTase-deficient organoids. Four experiments; except for β-catenin and Claudin-1, three experiments. (D) RAC1-deficient organoids. Three experiments; except for claudin-2, five experiments. (E) Apical-out GGTase-deficient organoids, representative pictures of Phalloidin staining. One experiment. Data are expressed as box-plots (Min to Max). Paired t-test. *P≤0.050. AJC, apical junction complex.

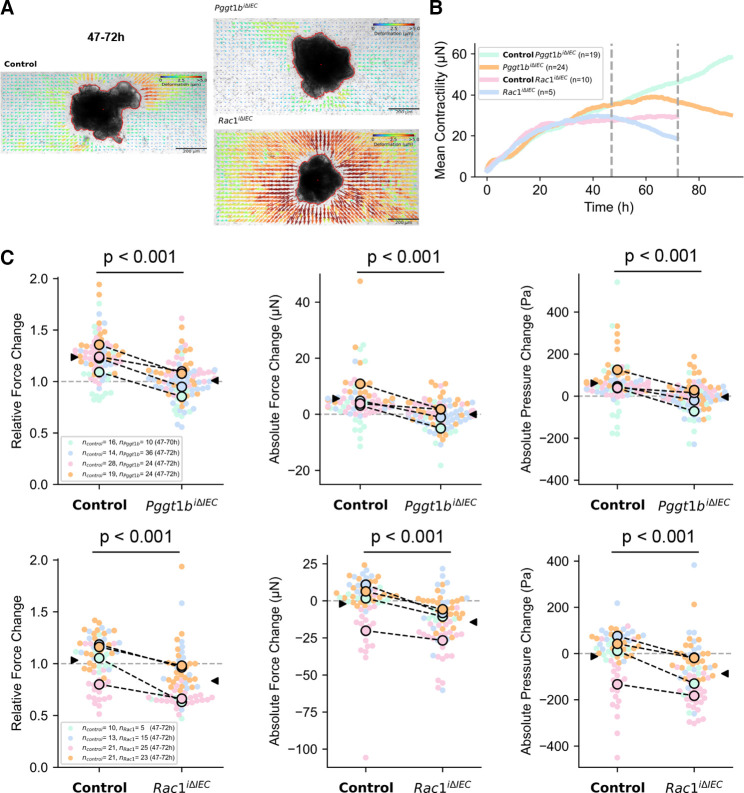

Figure 9.

3D traction-force microscopy in control, GGTase and RAC1-deficient small intestine organoids. (A) Organoid-generated matrix deformations between 47 hours and 72 hours of time-lapse imaging (48–73 hours after completion of collagen polymerisation). Representative control organoid shows inward-directed matrix deformation, indicative of force increase, whereas representative Pggt1b iΔIEC and Rac1 iΔIEC organoids show outward-directed deformations, indicative of force relaxation. (B) Mean contractility over time for control, Pggt1b iΔIEC and Rac1 iΔIEC organoids, each pair from the same replicate experiment. Grey lines indicate the 47 hours and 72 hours time point for which force development is reported in the figures below. The measurement of the Pggt1b iΔIEC and corresponding control organoids was carried out over 90 hours to demonstrate that the force trends continue. (C) Relative and absolute changes in contractile force and absolute changes in contractile pressure between 47 hours and 72 hours. Each point represents the data from an individual organoid, colours represent four biological replicates. Black circles represent the mean value for each biological replicate, and black arrows represent the mean value of all organoids. P values are calculated from a two-sided Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances. Paired t-test. *P≤0.050.

Our organoid data showed that epithelial intrinsic alterations on GGTase or RAC1 deletion in a system devoid of non-epithelial factors lead to cytoskeleton rearrangement and alterations of epithelial integrity. In order to have a closer look into these epithelial alterations, we performed an RNASeq analysis in RAC1-deficient small intestine organoids and compared them to wild-type organoids (online supplemental figure 6). In RAC1-deficient organoids, 137 genes were differentially expressed. Regulated expression of candidate genes was confirmed via RT-qPCR analysis (Adm2, Hif3a, Cxcl10, Klf2), in RAC1-deficient and GGTase-deficient organoids. Gene ontology annotation suggested that transcriptome changes on epithelial RAC1 deletion are associated to alterations of the response to bacterium and mechanical stimulus and immune response. Focusing on cellular components, cell surface, cell membrane, actin cytoskeleton and apical intercellular junctions are altered in RAC1-deficient organoids (online supplemental figure 6). At the pathway level (KEGG annotation), several inflammation-related pathways were regulated in RAC1-deficient epithelium, such as TNF, NFkB, MAPK, TLR and IL17 signalling, cell adhesion and leucocyte migration or tight junctions. Moreover, GSEA demonstrated that cell adhesion, chemokine activity and TNF/IL17 signalling are modulated in RAC1-deficient epithelium. The RNASeq analysis confirmed our suggested mechanism: cytoskeleton alterations leading to apical actin rearrangement and AJC redistribution would cause epithelial leakage and an altered immune response against components of the microbiota or mechanical stimulation.

Cell shedding alterations in IBD

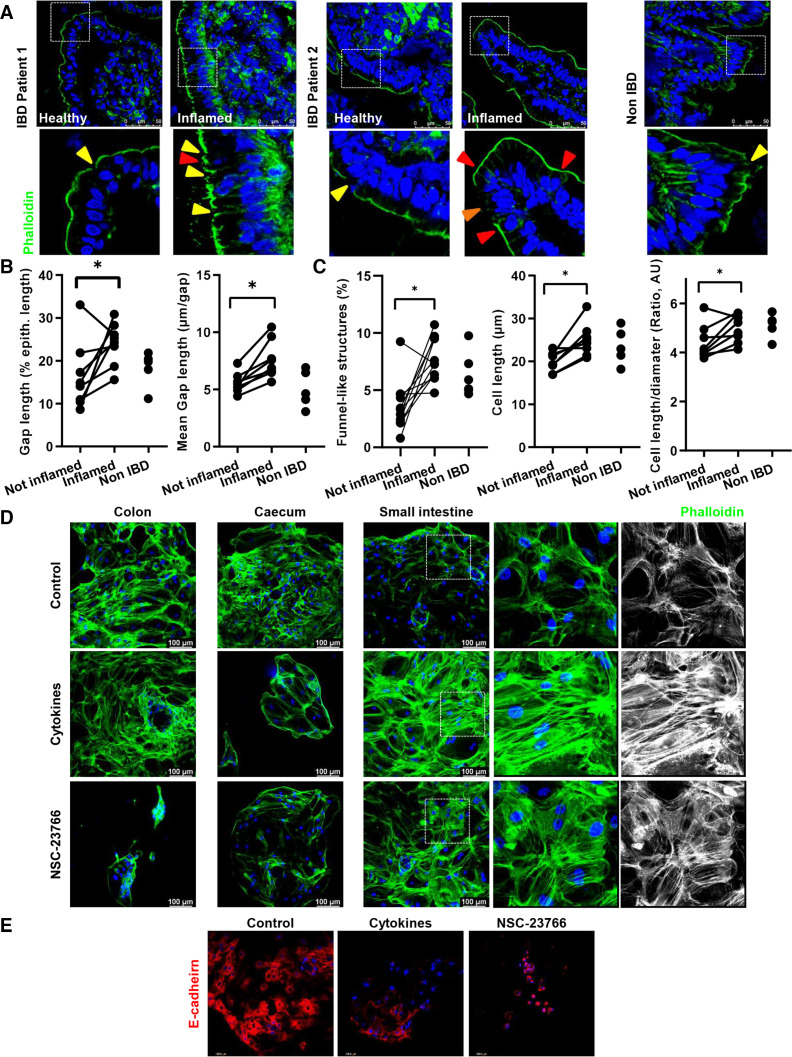

To provide further information about the role of cell shedding for human intestinal inflammation, we analysed cell shedding in small intestine samples from patients with IBD (active and non-active disease) and patients without IBD. We correlated alteration of barrier function, as determined by Watson scoring4 17 with signs of cell shedding arresting and/or overcrowding (figure 10). Inflammation went along with significantly increased epithelial gap density (% gap/total epithelial length) and gap length (mean length, µm) (figure 10A, B), confirming the epithelial leakage on inflammation. Along with this, the epithelium from inflamed areas showed a significant accumulation of funnel-like structures (online supplemental figure 2) and a trend to accumulated early cell shedding events (figure 10A, C; online supplemental figure 7); moreover, cell shape alterations in IECs from patients with IBD was demonstrated by significantly increased cell length and length/diameter ratio (figure 10A, C) (online supplemental figure 7). We then wondered whether this is associated with epithelial leakage and/or dysfunction. To test this, we then selected patients out of another human cohort featured for a correlation between FABP2 serum concentration and E-cadherin alterations (epithelial damage),46 and the appearance of funnel-like structures, as a surrogate of arrested cell shedding. Interestingly, despite the small number of samples, we could observe a positive correlation between FABP2/funnel-like structures, while E-cadherin expression negatively correlated to the FABP2 concentration (online supplemental figure 7). Together, these data indicated a potential association between arresting of cell shedding and epithelial leakage in IBD.

Figure 10.

Analysis of cell shedding and overcrowding in small intestine sections from human patients with IBD. (A–C) F-actin fibre staining using AlexaFluor488-phalloidin (green) (n=13, total; n=5, Control; n=8, CD). (A) Representative pictures (top); yellow arrows indicate epithelial gaps; orange arrow indicates microerosions. (B, C) Quantification. (B) Gap length (% of epithelial length), and mean gap length (µm/gap). (C) Funnel-like structures (red triangles) (% of total cells) and calculated length/diameter ratio (AU). (D, E) 2D/monolayer organoids generated from human intestinal crypts (three patients), and treated with NSC-23766 (100 µM) or a cytokine cocktail (IL-1β 10 ng/mL, IL-6 10 ng/mL and TNF-α; 20 ng/mL). (D) Phalloidin staining. (E) E-cadherin staining. Paired t-test. *P≤0.050. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Next, we aimed at establishing a link between RAC1-mediated cytoskeleton rearrangement and epithelial leakage. Interestingly, human two-dimension organoids47 depicted morphological changes and TJ alterations on treatment with a cytokine cocktail (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), mimicking the proinflammatory milieu in the inflamed gut,48 but profound actin redistribution could only be observed in the case of small intestine organoids (figure 10D, E) (online supplemental figure 7). Strikingly, similar epithelial alterations could be observed on treatment with the RAC1 inhibitor NSC-23766 (figure 10D). On a functional level, transepithelial resistance was significantly decreased when Caco2 or HT29 cells were treated with NSC-23766 or GGTI-298, respectively, and this correlated with actin redistribution (online supplemental figure 7). Hence, we could confirm that RAC1-dependent epithelial alterations (cytoskeleton rearrangement) induces a similar breakdown of epithelial barrier function to that occurring in the inflamed gut, underscoring the role of epithelial intrinsic mechanisms, such as cytoskeleton rearrangement due to inhibition of prenylation or RAC1.

Our data collected in human tissue samples and organoids support the link between arresting of cell shedding and overcrowding due to epithelial cytoskeleton/cell mechanics defects and chronic intestinal inflammation in IBD, demonstrating the clinical relevance of the identified mechanism in mouse studies.

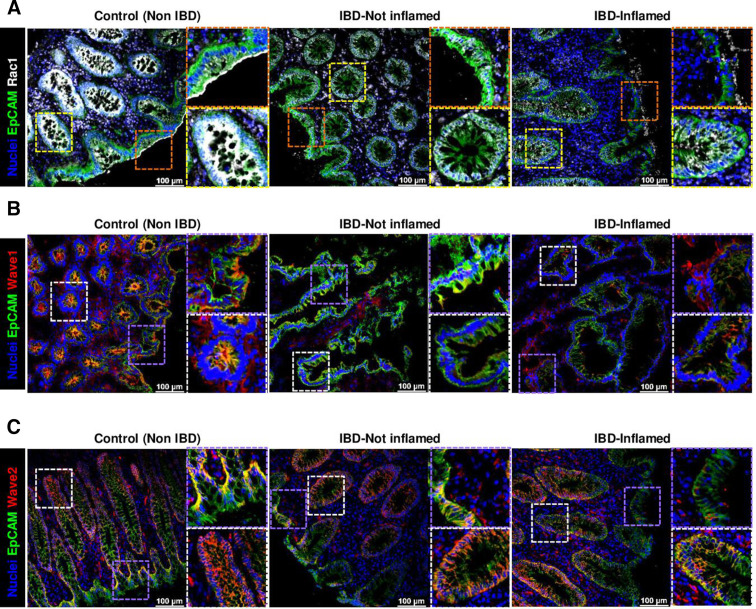

Alterations of the epithelial RAC1 pathway in IBD

Analysis of RAC1 subcellular localisation showed that apical membrane localization within IECs in the epithelial surface shifted towards the cytosol and/or nucleus in cells located at the crypt bottom in non-IBD tissue (figure 11A). This suggested a potential different RAC1 function for the regulation of epithelial extrusion (surface epithelium) and cell proliferation (crypt bottom). Interestingly, we could observe a shift in the RAC1 apical localization in patients with IBD, both in those in remission or with active disease and a decreased expression on inflammation, both indicative of RAC1 dysfunction (figure 11A).

Figure 11.

Analysis of RAC1 pathway in human IBD. (A) RAC1 immunostaining (white), counterstained with EpCAM (green) and Hoechst (blue). Representative pictures, showing expression and subcellular localisation at the epithelial surface (top) and crypts (bottom) (n=20, total; n=9, Control; n=11, IBD). Wave1 (B) and Wave2 (C) immunostaining (red) (Wave1, n=13, total; n=5, Control; n=8, IBD); (Wave2, n=17, total; n=6, Control; n=11, IBD).

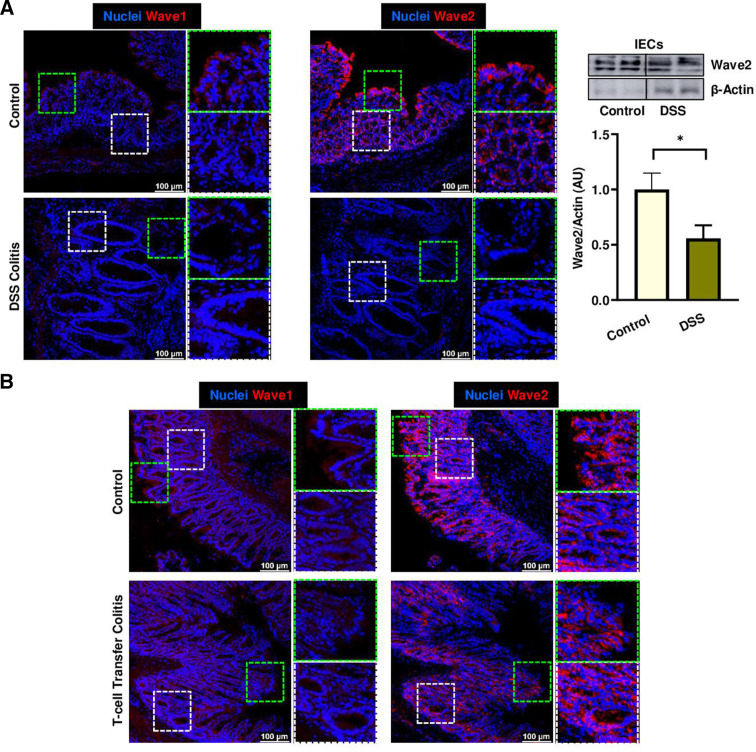

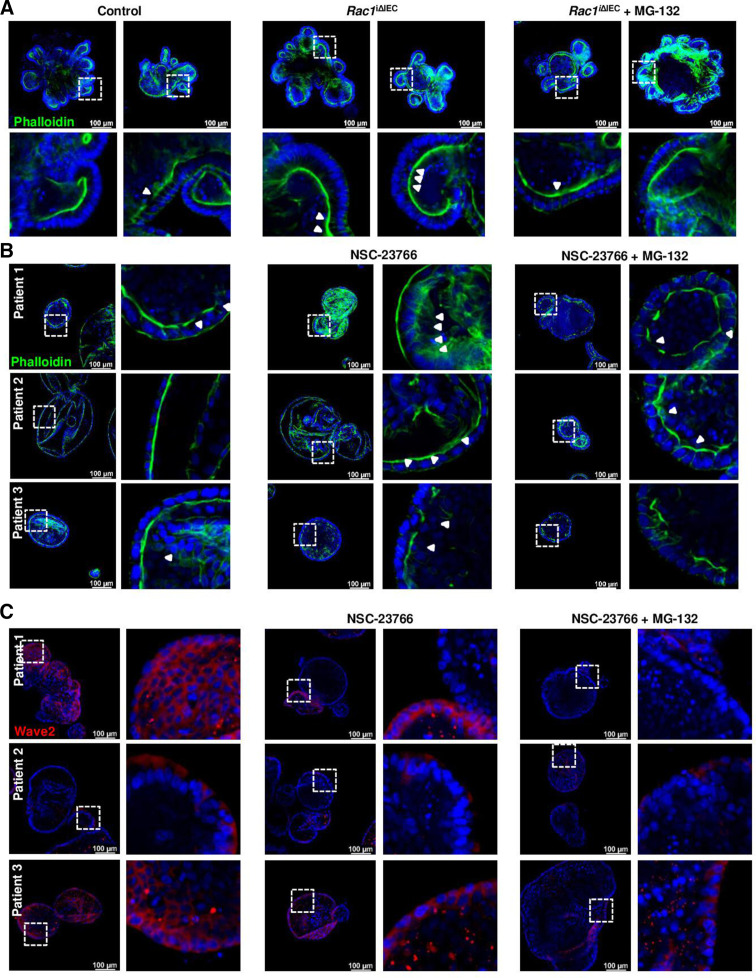

To confirm the potential relevance of RAC1-dependent pathway for the maintenance of gut epithelial integrity, we analysed WAVE proteins and RAC1-downstream pathway activation. In vivo, specially WAVE2 and also WAVE1 expression were significantly reduced in ileum tissue early on Rac1 deletion in IECs from Rac1 iΔIEC mice (online supplemental figure 5), suggesting that the presence of RAC1 is indispensable for the expression and/or stability of WAVE proteins. Strikingly, alterations in WAVE proteins could also be observed in the epithelium of patients with IBD. Patients with IBD showed decreased epithelial WAVE1 expression (figure 11B). Moreover, homogenous epithelial WAVE2 expression was absent at the surface of the epithelium on inflammation, while no change could be observed downwards the villus/crypt axis and in the crypts, indicating specific RAC1 dysfunction at the epithelial surface (figure 11C). Interestingly, we could observe WAVE2 decreased expression in large intestine epithelium from animals suffering from experimental colitis, such as dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) (figure 12A) or adoptive lymphocyte transfer colitis (figure 12B); this correlated with the inflammation degree and was mainly observed at the epithelial surface. Western blot analysis confirmed the downregulation of WAVE2 in IECs isolated from mice suffering from DSS-induced colitis (figure 12A). Since Wasf1 and Wasf2 gene expression was not altered in colon IECs from DSS or TC mice, nor in small intestine GGTase- or RAC1-deficient organoids (online supplemental figure 8), we assumed that RAC1-dependent regulation of Wave proteins is mediated via protein stability and/or post-translational mechanisms. Since WAVE protein stability is regulated via proteasomic degradation,49 we then tested the effect of inhibition of proteasome (MG-132) on WAVE degradation and the impact on cell shedding alterations. The accumulation of arrested cell shedding events in RAC1-deficient small intestine organoids was partially rescued on MG132 proteasome inhibition (figure 13A). Similarly, accumulation of funnel-like structures on treatment with the RAC1 inhibitor NSC-23766 was associated with decreased WAVE2 expression in human organoids (figure 13B, C). This actin alteration was only partially rescued on MG132 treatment, which is in agreement with the fact that proteasome inhibition did not rescue WAVE2 expression on NSC23766-mediated RAC1 inhibition in human organoids (figure 13B, C). Together, these data demonstrated that RAC1 function and downstream pathway can contribute to cytoskeleton rearrangement within IECs, specially at the epithelial surface and/or villus tip, for maintenance of epithelial integrity in the gut of patients with IBD, in a mechanism related to cell shedding alterations.

Figure 12.

Analysis of RAC1 pathway in experimental colitis. WAVE1 and WAVE2 expression in mouse experimental colitis models. (A) DSS-induced colitis. Representative pictures from immunostaining in colon samples (left), and WB from isolated IECs (right). Immunostaining (n=10, total; n=5, Control; n=5); WB (n=13, total; n=6, Control; n=7, DSS). (B) Adoptive lymphocyte TC. Representative pictures from immunostaining in colon samples (n=14, total; n=6, Control; n=8). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Unpaired t-test. *P≤0.050. TC, transfer colitis.

Figure 13.

Interfering with RAC1 pathway in organoids. (A) RAC1-deficient small intestine organoids treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (1 µM). Phalloidin staining. Three experiments. (B, C) Human organoids treated with the RAC1 inhibitor NSC-23766 (100 µM) with or without the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (n=3). (B) Phalloidin staining. (C) Wave2 staining.

Discussion

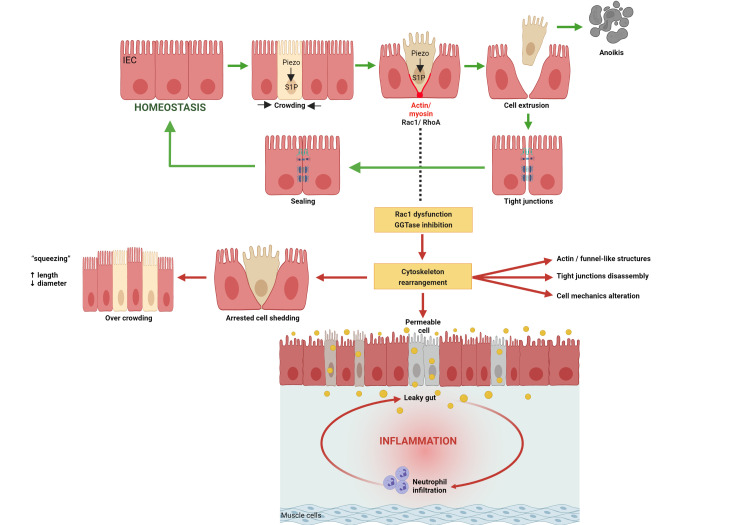

Here, we demonstrated that cytoskeleton rearrangement and cell shedding disturbances represent causative phenomena triggering increased permeability, finally resulting in intestinal inflammation and destruction of tissue architecture. Thus, epithelial leakage on arresting of physiological cell shedding triggers intestinal inflammation. Early cytoskeleton rearrangement on inhibition of epithelial GGTase-prenylation in Pggt1b iΔIEC mice34 impaired completion of cell extrusion, causing arresting of cell shedding, overcrowding and the appearance of ‘permeable’ cells (figure 14). This phenotype mainly affected the small intestine and to a lesser extent the colon. The novelty of our study lies on the fact that epithelial changes in GGTase-deficient and RAC1-deficient epithelium are triggered exclusively by cell intrinsic phenomena, nevertheless, also resulting in intestinal inflammation. Like TNF-induced epithelial alterations,50 intestinal tissue from Pggt1b iΔIEC and Rac1 iΔIEC mice showed cytoskeleton/TJ alterations and subsequent epithelial destruction and barrier breakdown. RAC1 and GGTase-deficient organoids showed cytoskeleton rearrangement and loss of epithelial integrity, indicative of primary epithelial alterations in the absence of extrinsic factors. Interestingly, AJC protein redistribution on prenylation inhibition or RAC1 deficiency mirrored epithelial dysfunction in human intestinal inflammation, that is, changes in claudin-1,51 claudin-2,52 claudin-826 to claudin-18,53 E-cadherin,54 β-catenin and ZO-1.55 Together, our data highlight RAC1 as a GGTase-target contributing to epithelial integrity and intestinal homeostasis.

Figure 14.

Mechanism behind intestinal inflammation induced by inhibition of GGTase1 or RAC1 within intestinal epithelial cells. Figure has been created with BioRender.com.

Translationally, our study revealed a potential correlation between alteration of physiological cell shedding and epithelial RAC1 pathway and intestinal inflammation in IBD. In our human cohort, signs of barrier dysfunction (epithelial gaps) go along with the accumulation of funnel-like structures and elongated cell shapes in inflamed areas of the gut of patients with IBD, suggesting an association between inflammation in IBD and arrested shedding and cell overcrowding. Strikingly, this could also be linked to epithelial leakage, as indicated by elevated serum FABP2 levels and alterations of E-cadherin. Furthermore, the fact that NSC-23766-induced RAC1 inhibition caused cytoskeleton rearrangement and TJ disassembly (human organoids) and impaired transepithelial resistance (human epithelial cell lines) confirmed the breakdown of epithelial barrier function on epithelial intrinsic mechanisms, such as altered cell mechanics due to inhibition of prenylation or RAC1. Notably, our analysis of patient material for the first time showed that, beyond pathological cell shedding, control of live cell extrusion might play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation and should be further explored in the context of IBD.

The segregation between physiological and pathological cell shedding is tightly connected to apoptosis.56 Since TJs expression regulates caspase activity and apoptotic cell death,57 we hypothesised that cytoskeleton rearrangement and TJs redistribution might cause the observed decreased caspase-3 cleavage both in GGTase1B- and RAC1-deficient epithelium on arrested cell shedding. Moreover, the shift between apoptosis and caspase-independent cell death suggested the potential activation of alternative cell death pathways in GGTase- or RAC1-deficient epithelium. Our findings are in agreement with the contribution of cell death activation to the intestinal damage in GGTase and/or RAC1-deficient mice, but our data demonstrate that this should be considered as additional mechanism contributing to further epithelial damage and tissue destruction.

Transcriptomic changes in RAC1-deficient intestinal organoids were associated with a modulated response to mechanical stimulus, proposing a key function for mechanobiology in RAC1-mediated epithelial integrity. Actually, GGTase-deficient and RAC1-deficient IECs showed alterations of cell shape (TEM), while inhibition of prenylation correlated with changes in IEC deformability (RT-FDC). 3D traction force microscopy analysis suggested the existence of an interplay between changes in epithelial cytoskeleton and ECM mechanics. In contrast to WT organoids, those generated from Pggt1b iΔIEC and Rac1 iΔIEC mice showed outward-directed matrix deformations, indicative of force relaxation. Thus, cytoskeleton rearrangement in GGTase- and RAC1-deficient epithelium impacts on IEC and/or ECM mechanics. Furthermore, cytoskeleton dynamics can also directly impact on gene transcription.58 In our RNASeq analysis, several chemokines promoting immune cell recruitment appeared among the most regulated genes in RAC1-deficient organoids (CXCL-1, CXCL-2 and CXCL-10). Together, RAC1-dependent epithelial cell mechanics emerged as a crucial epithelial-intrinsic mechanism to understand the interplay between IECs and its extracellular environment and how this impacts on epithelial-immune communication. Contributing to gut tissue homeostasis, epithelial cell mechanics should be further studied in the context of human diseases, such as IBD.

The difference in severity of intestinal disease in Pggt1b iΔIEC and RhoA ΔIEC mice34 suggested the existence of a compensatory functional overlapping between RHOA and other prenylation targets. Accordingly, impaired RAC1 function mimicked epithelial alteration on inhibition of prenylation. Several studies aimed at deciphering the contribution of RHOA/RAC1/CDC42-dependent acto-myosin ‘purse string’ and RAC1-mediated cell crawling to epithelial gap closure.31 37 Considering the gap geometry, negative curvature promotes RHOA-dependent actin ring closure, while positive curvatures dictates RAC1-mediated cell crawling.59 In agreement with our data, epithelial cell extrusion would be rather regulated by RAC1 function due to convex geometry at the villus tip. Also, it has been shown that RAC1-dependent cytoskeleton rearrangement controls crypt/villus compartmentalisation in mouse small intestine, while the absence of RAC1 lead to disturbed intestinal architecture.60 These observations concurred with our data on RAC1-dependent epithelial integrity and maintenance of gut tissue structure in vivo.

Along the villus/crypt axis, ubiquitous RAC1 appears at the crypt bottom and transient- amplyifing area (TAA), while membrane/cytosol protein is restricted to the villus. Interestingly, the subcellular shift of RAC1 as well as the downregulation of epithelial WAVE2 expression on inflammation in IBD is also restricted to the epithelial surface, and potentially associated to specific alterations of membrane RAC1. RAC1 can also translocate to the nucleus and participate in cell cycle regulation and nuclear cytoskeletal features,61 thereby controlling cancer progression.62 Still unknown is how prenylation can differentially affect membrane/nuclear localisation of activated RAC1 and regulate epithelial barrier in inflammation or hyperproliferation in cancer, respectively.

Validating the relevance of RAC1 in intestinal homeostasis, alterations on genes encoding for Rac proteins63 64 and RAC1 signalling65 have been associated to IBD. Also, azathioprine-dependent Vav/RAC1 targeting induces T cell apoptosis, and is therefore currently used as a treatment for patients with IBD.66 Despite specific RAC1 inhibitors,67 68 others69 and our data postulate RAC1 activation can contribute to protect epithelial integrity. Thus, modulation of RAC1 function can pave the way to the identification of biomarkers for diagnosis, prediction and/or prevention of flares in IBD,70 and be exploited for epithelial restoration.71 72 Nevertheless, potentially opposite effects in IECs and immune cells underscores the relevance of cell-specific studies to optimise pharmacological targeting of Rho GTPases.34 73 74

Acknowledgments

The present work was performed in (partial) fulfilment of the requirements for obtaining the degree Dr rer. nat. for Luz del Carmen Martínez Sánchez, Phuong A Ngo and Rashmita Pradhan.In some cases, microscopy/Image analysis was performed with the support of the Optical Imaging Centre Erlangen (OICE) and Philipp Tripal. Confocal microscopy was performed on a Leica Stellaris 8 system, funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project 441 730 715.

Footnotes

Twitter: @AlastairWatson3

MFN and RL-P contributed equally.

Contributors: RP, LdCMS, PAN and L-SB performed the majority of the experiments. RP, TK, VT, LE, IS, CBe, CG and BW contributed and/or supported us for some experiments. DB and BF performed 3D traction force microscopy measurements. DS, MKu, CS and JG performed RT-FDC experiments. MKl, CD and KA performed electron microscopy experiments. ST performed mass spectrometry experiments. RA provided human material/samples. AJMW and IA read the manuscript and contributed to the finalised version. MB and CBr provided mouse lines. MFN and RP designed the study and wrote the manuscript. RLP is responsible for the overall content as guarantor. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG); Grant numbers (LO-2465/1-1, SPP-1782-LO-2465/2-1, TRR241-A07, TRR-SFB225 (A01), Emerging Fields Initiative of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg) and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research (IZKF) at the University Hospital of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (ELAN).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Ethics Committee of the Department of Medicine of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (Erlangen, Germany) (Reference number 440_20 B). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Turner JR. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:799–809. 10.1038/nri2653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011;474:298–306. 10.1038/nature10208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kiesslich R, Goetz M, Angus EM, et al. Identification of epithelial gaps in human small and large intestine by confocal endomicroscopy. Gastroenterology 2007;133:1769–78. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim LG, Neumann J, Hansen T, et al. Confocal endomicroscopy identifies loss of local barrier function in the duodenum of patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:892–900. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vivinus-Nébot M, Frin-Mathy G, Bzioueche H, et al. Functional bowel symptoms in quiescent inflammatory bowel diseases: role of epithelial barrier disruption and low-grade inflammation. Gut 2014;63:744–52. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Munkholm P, Langholz E, Hollander D, et al. Intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis and their first degree relatives. Gut 1994;35:68–72. 10.1136/gut.35.1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peeters M, Geypens B, Claus D, et al. Clustering of increased small intestinal permeability in families with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1997;113:802–7. 10.1016/S0016-5085(97)70174-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ussar S, Moser M, Widmaier M, et al. Loss of Kindlin-1 causes skin atrophy and lethal neonatal intestinal epithelial dysfunction. PLoS Genet 2008;4:e1000289. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sivagnanam M, Mueller JL, Lee H, et al. Identification of EpCAM as the gene for congenital tufting enteropathy. Gastroenterology 2008;135:429–37. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Williams JM, Duckworth CA, Burkitt MD, et al. Epithelial cell shedding and barrier function: a matter of life and death at the small intestinal villus tip. Vet Pathol 2015;52:445–55. 10.1177/0300985814559404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marchiando AM, Shen L, Graham WV, et al. The epithelial barrier is maintained by in vivo tight junction expansion during pathologic intestinal epithelial shedding. Gastroenterology 2011;140:e1-2:1208–18. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grossmann J. Molecular mechanisms of "detachment-induced apoptosis--Anoikis". Apoptosis 2002;7:247–60. 10.1023/A:1015312119693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sellin ME, Müller AA, Felmy B, et al. Epithelium-intrinsic NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome drives infected enterocyte expulsion to restrict Salmonella replication in the intestinal mucosa. Cell Host Microbe 2014;16:237–48. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kajita M, Fujita Y. EDAC: epithelial defence against cancer-cell competition between normal and transformed epithelial cells in mammals. J Biochem 2015;158:15–23. 10.1093/jb/mvv050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gu Y, Shea J, Slattum G, et al. Defective apical extrusion signaling contributes to aggressive tumor hallmarks. Elife 2015;4:e04069. 10.7554/eLife.04069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Slattum GM, Rosenblatt J. Tumour cell invasion: an emerging role for basal epithelial cell extrusion. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:495–501. 10.1038/nrc3767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kiesslich R, Duckworth CA, Moussata D, et al. Local barrier dysfunction identified by confocal laser endomicroscopy predicts relapse in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2012;61:1146–53. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu JJ, Kay TM, Davis EM, et al. Epithelial cell extrusion zones observed on confocal laser endomicroscopy correlates with immunohistochemical staining of mucosal biopsy samples. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:1895–902. 10.1007/s10620-016-4154-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eisenhoffer GT, Loftus PD, Yoshigi M, et al. Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia. Nature 2012;484:546–9. 10.1038/nature10999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marinari E, Mehonic A, Curran S, et al. Live-cell delamination counterbalances epithelial growth to limit tissue overcrowding. Nature 2012;484:542–5. 10.1038/nature10984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. Feeling the squeeze: live-cell extrusion limits cell density in epithelia. Cell 2012;149:965–7. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gu Y, Forostyan T, Sabbadini R, et al. Epithelial cell extrusion requires the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 pathway. J Cell Biol 2011;193:667–76. 10.1083/jcb.201010075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madara JL. Maintenance of the macromolecular barrier at cell extrusion sites in intestinal epithelium: physiological rearrangement of tight junctions. J Membr Biol 1990;116:177–84. 10.1007/BF01868675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guan Y, Watson AJM, Marchiando AM, et al. Redistribution of the tight junction protein ZO-1 during physiological shedding of mouse intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2011;300:C1404–14. 10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laukoetter MG, Nava P, Lee WY, et al. Jam-A regulates permeability and inflammation in the intestine in vivo. J Exp Med 2007;204:3067–76. 10.1084/jem.20071416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn's disease. Gut 2007;56:61–72. 10.1136/gut.2006.094375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heller F, Florian P, Bojarski C, et al. Interleukin-13 is the key effector Th2 cytokine in ulcerative colitis that affects epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and cell restitution. Gastroenterology 2005;129:550–64. 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Naydenov NG, Feygin A, Wang D, et al. Nonmuscle myosin IIA regulates intestinal epithelial barrier in vivo and plays a protective role during experimental colitis. Sci Rep 2016;6:24161. 10.1038/srep24161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma Y, Yue J, Zhang Y, et al. ACF7 regulates inflammatory colitis and intestinal wound response by orchestrating tight junction dynamics. Nat Commun 2017;8:15375. 10.1038/ncomms15375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arnold TR, Stephenson RE, Miller AL. Rho GTPases and actomyosin: partners in regulating epithelial cell-cell junction structure and function. Exp Cell Res 2017;358:20–30. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.03.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tamada M, Perez TD, Nelson WJ, et al. Two distinct modes of myosin assembly and dynamics during epithelial wound closure. J Cell Biol 2007;176:27–33. 10.1083/jcb.200609116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kuipers D, Mehonic A, Kajita M, et al. Epithelial repair is a two-stage process driven first by dying cells and then by their neighbours. J Cell Sci 2014;127:1229–41. 10.1242/jcs.138289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenblatt J, Raff MC, Cramer LP. An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism. Curr Biol 2001;11:1847–57. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00587-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. López-Posadas R, Becker C, Günther C, et al. Rho-A prenylation and signaling link epithelial homeostasis to intestinal inflammation. J Clin Invest 2016;126:611–26. 10.1172/JCI80997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martínez-Sánchez LD, Pradhan R, Ngo PA, et al. An intravital microscopy-based approach to assess intestinal permeability and epithelial cell shedding performance. J Vis Exp 2020;166. 10.3791/60790. [Epub ahead of print: 03 12 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eisenhoffer GT, Loftus PD, Yoshigi M, et al. Crowding induces live cell extrusion to maintain homeostatic cell numbers in epithelia. Nature 2012;484:546–9. 10.1038/nature10999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Begnaud S, Chen T, Delacour D, et al. Mechanics of epithelial tissues during gap closure. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2016;42:52–62. 10.1016/j.ceb.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosendahl P, Plak K, Jacobi A, et al. Real-time fluorescence and deformability cytometry. Nat Methods 2018;15:355–8. 10.1038/nmeth.4639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rahner C, Mitic LL, Anderson JM. Heterogeneity in expression and subcellular localization of claudins 2, 3, 4, and 5 in the rat liver, pancreas, and gut. Gastroenterology 2001;120:411–22. 10.1053/gast.2001.21736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Flores-Romero H, Ros U, Garcia-Saez AJ. Pore formation in regulated cell death. Embo J 2020;39:e105753. 10.15252/embj.2020105753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 2015;526:660–5. 10.1038/nature15514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan G, Huang C, Chen J. An IRF1-dependent pathway of TNFalpha-induced shedding in intestinal epithelial cells. J Crohns Colitis 2021;16. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Desai LP, Aryal AM, Ceacareanu B, et al. Rhoa and Rac1 are both required for efficient wound closure of airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;287:L1134–44. 10.1152/ajplung.00022.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mark C, Grundy TJ, Strissel PL. Collective forces of tumor spheroids in three-dimensional biopolymer networks. Elife 2020. 10.7554/eLife.51912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cóndor M, Steinwachs J, Mark C, et al. Traction force microscopy in 3-dimensional extracellular matrix networks. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2017;75:10.22.1-10.22.20. 10.1002/cpcb.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schellekens DH, Hundscheid IH, Leenarts CA, et al. Human small intestine is capable of restoring barrier function after short ischemic periods. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:8452–64. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Altay G, Larrañaga E, Tosi S, et al. Self-organized intestinal epithelial monolayers in crypt and villus-like domains show effective barrier function. Sci Rep 2019;9:10140. 10.1038/s41598-019-46497-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Arnauts K, Verstockt B, Ramalho AS, et al. Ex Vivo Mimicking of Inflammation in Organoids Derived From Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1564–7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Joseph N, Biber G, Fried S, et al. A conformational change within the WAVE2 complex regulates its degradation following cellular activation. Sci Rep 2017;7:44863. 10.1038/srep44863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Su L, Nalle SC, Shen L, et al. TNFR2 activates MLCK-dependent tight junction dysregulation to cause apoptosis-mediated barrier loss and experimental colitis. Gastroenterology 2013;145:407–15. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Poritz LS, Harris LR, Kelly AA, et al. Increase in the tight junction protein claudin-1 in intestinal inflammation. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2802–9. 10.1007/s10620-011-1688-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Luettig J, Rosenthal R, Barmeyer C, et al. Claudin-2 as a mediator of leaky gut barrier during intestinal inflammation. Tissue Barriers 2015;3:e977176. 10.4161/21688370.2014.977176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zwiers A, Fuss IJ, Leijen S, et al. Increased expression of the tight junction molecule claudin-18 A1 in both experimental colitis and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14:1652–9. 10.1002/ibd.20695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. UK IBD Genetics Consortium, Barrett JC, Lee JC, et al. Genome-Wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet 2009;41:1330–4. 10.1038/ng.483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kucharzik T, Walsh SV, Chen J, et al. Neutrophil transmigration in inflammatory bowel disease is associated with differential expression of epithelial intercellular junction proteins. Am J Pathol 2001;159:2001–9. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63051-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Frisch SM, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, et al. Control of adhesion-dependent cell survival by focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol 1996;134:793–9. 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kuo W-T, Shen L, Zuo L, et al. Inflammation-Induced occludin downregulation limits epithelial apoptosis by suppressing caspase-3 expression. Gastroenterology 2019;157:1323–37. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Németh ZH, Deitch EA, Davidson MT, et al. Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton results in nuclear factor-kappaB activation and inflammatory mediator production in cultured human intestinal epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol 2004;200:71–81. 10.1002/jcp.10477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ravasio A, Cheddadi I, Chen T, et al. Gap geometry dictates epithelial closure efficiency. Nat Commun 2015;6:7683. 10.1038/ncomms8683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sumigray KD, Terwilliger M, Lechler T. Morphogenesis and compartmentalization of the intestinal crypt. Dev Cell 2018;45:183–97. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Michaelson D, Abidi W, Guardavaccaro D, et al. Rac1 accumulates in the nucleus during the G2 phase of the cell cycle and promotes cell division. J Cell Biol 2008;181:485–96. 10.1083/jcb.200801047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mendoza-Catalán MA, Cristóbal-Mondragón GR, Adame-Gómez J, et al. Nuclear expression of Rac1 in cervical premalignant lesions and cervical cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2012;12:116. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Muise AM, Walters T, Xu W, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms that increase expression of the guanosine triphosphatase Rac1 are associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011;141:633–41. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Muise AM, Xu W, Guo C-H, et al. NADPH oxidase complex and IBD candidate gene studies: identification of a rare variant in NCF2 that results in reduced binding to Rac2. Gut 2012;61:1028–35. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Guo Y, Xiong J, Wang J, et al. Inhibition of Rac family protein impairs colitis and colitis-associated cancer in mice. Am J Cancer Res 2018;8:70–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tiede I, Fritz G, Strand S, et al. CD28-dependent Rac1 activation is the molecular target of azathioprine in primary human CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest 2003;111:1133–45. 10.1172/JCI16432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ferri N, Corsini A, Bottino P, et al. Virtual screening approach for the identification of new Rac1 inhibitors. J Med Chem 2009;52:4087–90. 10.1021/jm8015987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cardama GA, Comin MJ, Hornos L, et al. Preclinical development of novel Rac1-GEF signaling inhibitors using a rational design approach in highly aggressive breast cancer cell lines. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2014;14:840–51. 10.2174/18715206113136660334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zheng X-B, Liu H-S, Zhang L-J, et al. Engulfment and cell motility protein 1 protects against DSS-induced colonic injury in mice via Rac1 activation. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:100–14. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Irvine EJ, Marshall JK. Increased intestinal permeability precedes the onset of Crohn's disease in a subject with familial risk. Gastroenterology 2000;119:1740–4. 10.1053/gast.2000.20231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Arrieta MC, Madsen K, Doyle J, et al. Reducing small intestinal permeability attenuates colitis in the IL10 gene-deficient mouse. Gut 2009;58:41–8. 10.1136/gut.2008.150888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Graham WV, He W, Marchiando AM, et al. Intracellular MLCK1 diversion reverses barrier loss to restore mucosal homeostasis. Nat Med 2019;25:690–700. 10.1038/s41591-019-0393-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pradhan R, Ngo PA, Martínez-Sánchez LD, et al. Rho GTPases as key molecular players within intestinal mucosa and Gi diseases. Cells 2021;10. 10.3390/cells10010066. [Epub ahead of print: 04 01 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. López-Posadas R, Fastancz P, Martínez-Sánchez LDC, et al. Inhibiting PGGT1B disrupts function of RhoA, resulting in T-cell expression of integrin α4β7 and development of colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2019;157:1293–309. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2021-325520supp001.pdf (207.3KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2021-325520supp002.pdf (34.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.