Abstract

Dark tourists experience negative and positive feelings in Holocaust places, suggesting emotional ambivalence. The research question of this study is, “is feeling well-being, as a consequence of dark tourism, a way of banalizing the horror?”. The purpose of this study is threefold: to provide an updated systematic literature review (SLR) of dark tourism associated with Holocaust sites and visitors' well-being; to structure the findings into categories that provide a comprehensive overview of the topics; and to identify which topics are not well covered, thus suggesting knowledge gaps. Records to be included should be retrievable articles in peer-reviewed academic journals, books, and book chapters, all focused on the SLR's aims and the research question; other types of publications were outrightly excluded. The search was performed in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases with three keywords and combinations: “dark tourism”, “Holocaust”, and “well-being”. Methodological decisions were based on the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS). This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. During the process, 144 documents were included, of which 126 were journal articles, 8 were books, and 10 were book chapters. The results point out a hierarchical structure with the main category (Dark tourism - Holocaust - Well-being) and three second-order categories (Dark tourism - Holocaust, Dark tourism - Well-being, and Holocaust - Well-being), from which different subcategories emerge: motivations for visiting places and guiding; ambivalent emotional experience that leads to the transformation of the self; and intergenerational trauma. The gaps identified were the trivialization of horror in Holocaust places; dark tourist profile; motivations and constraints behind visiting dark places; Holocaust survivors and their descendants' well-being; how dark tourism associated with the Holocaust positively or negatively impacts well-being. Major limitations included: lack of randomized allocation; lack of standard outcome definitions; and suboptimal comparison groups. Positive and negative impacts on the well-being of the Holocaust dark tourist were sought, as they are associated with the marketing and management, promotion, digital communication, guiding, or storytelling design of such locations.

Keywords: Dark tourism, Holocaust, Well-being, Thanatourism, Systematic review

1. Introduction

For a long time, places that have been the scene of wars, disasters, deaths, and atrocities have always fascinated people, motivating them to travel [1,2], giving rise to a type of tourism that has been addressed in different ways, namely, as negative sightseeing [3], black spots tourism [4], thanatourism [5], tragic tourism [6], atrocity tourism [7,8], morbid tourism [9], and dark tourism [10]. The term dark tourism, the most profusely used by the scientific community and the general public [11], was first introduced by Foley and Lennon [10], who refer to these phenomena as embracing “the presentation and consumption (by visitors) of real and commodified death and disaster sites” and the “commodification of anxiety and doubt” [12]. According to Stone [13], dark tourism is “an old concept in a new world”, and the novelty lies in the growing commodification of dark tourism sites; it “refers to visits, intentional or otherwise, to purposeful/non-purposeful sites which offer a presentation of death or suffering as the raison d'être” [13]. Dark tourism involves traveling to sites related to death, suffering and the macabre, a generally accepted definition [1], and disgrace [14,15]. Tarlow [16] suggests the phenomenon is complex by describing it as “visits to places where noteworthy historical tragedies or deaths have occurred that continue to impact our lives”, which raises the question about the inherent motives to consume dark tourism.

Stone's conception of dark tourism goes beyond its related attractions [14]. From his perspective, various well-visited tourist sites may become places of dark tourism due to their history associated with death – e.g., the Eiffel Tower (suicides), the pyramids of Egypt or the Valley of the Kings (tombs), the Cairo Museum (funeral art), the Taj Mahal (tomb), or Ground Zero (terrorist attacks) [17]. Ashworth and Isaac [18] also suggest that a tourist site has a higher or lower potential to be perceived as dark, evoking different experiences in different visitors (e.g., a site one visitor sees as “dark” may not be for another). Thus, the authors argue that no site is intrinsically, automatically, and universally “dark” as, although they may be labeled as dark, they are not always perceived as such by all visitors. According to Stone [14], the dark tourism offers fall within a spectrum whose intensity is positioned on a continuum between the darkest and the lightest, given the characteristics and perceptions of the dark tourism product. The offer ranked as the darkest in the dark tourism spectrum corresponds to sites where death, or another event involving suffering, occurred on a closer timescale. Those places hold greater symbolic meaning due to a stronger ideological and political influence, as they are evocative and focused on the conservation, preservation, and celebration of memory, and have serve pedagogical purposes. On the contrary, the lighter dark tourism attractions correspond to places that were originally conceived as tourist attractions, which explore the romanticized and commodified association or representation of death and suffering that occurred on an older temporal scale and, therefore, with a weaker emotional impact [14]. Light [19] posits that the existence of the “dark tourist” is questionable, in contrast to Seaton [5], who considers it central. Museums, memorials, cemeteries, prisons, battlefields, concentration camps, scenes of attacks and other tragedies, slums, and sites that intentionally recreate death and suffering can be considered places of dark tourism with different intensity levels of dark [14]. Whereas in some places there were, in reality, deaths and atrocities, other places are intentionally built to recreate dark events. Dale and Robinson [20] discussed the internationalization of the dark with the ‘Disneyization’ and ‘McDonaldization’ of dark tourism attractions. The growth in dark tourism demand [21] does not forget that death and suffering are increasingly transformed into a spectacle, largely due to the role played by the media and cultural industries, such as cinema, television, music, or literature [4,22]. Related exhibitions, museums, memorials, and television documentaries can be seen as edutainment; the “dead may be encountered for educational purposes” [22].

Dark tourism has become a field of interest and a subsequent debate, around the offer (supply) and demand sides, has focused on definitions and typologies, ethical issues, the political role of these sites, motivations, behaviors, and experiences of visitors, management, interpretation, and marketing [19]. Although some authors consider dark tourism as one of the oldest forms of tourism, it only gained popularity amongst academics from the 1990s onwards [23], confirmed by the growing amount of literature published ever since, which includes an increasing number of empirical studies on the reasons for visiting those sites [11,24,25], although still underdeveloped [13]. However, the understanding of the demand for this type of tourism remains an understudied area, poorly defined and theoretically fragile [23,24,26,27]. However, “a fresh academic wave, recently emerged, redefines dark tourism from the pilgrimage-based paradigm arguing that societies often elaborate shared discourses and narratives to placate the negative psychological effects of trauma” [28]. Biran and Hyde [29] moved beyond a discussion of classifications of dark tourism to the recognition of dark tourism as both an individual experience and a complex socio-cultural phenomenon, thus moving from a purely descriptive to an experiential and critical investigation of dark tourism.

Despite death being a part of the history of many dark tourism sites, it is not always the primary or explicitly recognized motivation behind a visit. Walter [22] states that most dark tourism is not specifically motivated, constituting only parallel visits inserted in a trip with a wider reach. The intentions to visit dark tourism sites could be related to dark tourism as an “anthropological attempt to domesticate death”, in contrast with the morbid nature of dark consumption [30]. Nevertheless, the literature suggests that tourists who visit dark sites are not a homogeneous group, and the factors inherent to the visitation are also not the same. Furthermore, the “darker” nature of the motivation can assume different levels of intensity. As such, in addition to the fascination and interest in death [5,18,31], the visit to this type of site is also motivated by personal, cultural, and psychological reasons [24]. Educational experience, the desire to learn and understand past events, and historical interest have been mentioned [19,26,[32], [33], [34]], as well as self-discovery [32], identity [26], memory, remembrance, celebration, nostalgia, empathy, contemplation, and homage [16,32,34], curiosity [32–35], the search for novelty, authenticity, and adventure [1,34], leisure [26], convenience when visiting other places [33], and also status, prestige, affirmation, and recognition that these visits provide [36]. To a lesser extent, the literature also mentions religious and pilgrimage reasons, feelings of guilt, search for social responsibility, or heritage experience. A death site is often viewed from the perspectives of religion and spirituality; dark tourists identify with the “belief, comfort, reflection, ethics, and awe on God and their relationships with other people”, allowing them to “understand the meaning of life, love, and living” [30]. Iliev [24] concludes that although tourists visit places related to death, they may not necessarily be considered dark tourists; as already acknowledged, those sites may not be experienced as “dark” by each visitor. It is, therefore, imperative that the so-called dark tourists are considered as such based on their experience. Some visitors may show a strong desire for an emotional experience and connection to their heritage, engaging, in the words of Slade [37], in a “profound heritage experience”; other visitors may be knowledge seekers, who are more interested in a knowledge-enriching experience [38] than an emotional one and look for gaining a deeper understanding. This latter perspective relates to eudemonic well-being, which takes place when one experiences meaning and self-fulfillment in life [39] and long-term life satisfaction and positive functioning [40].

Holocaust-related places attract many visitors and constitute a specific segment of dark tourism, referred to as Holocaust tourism by Griffiths [41], and are often seen as the darkest dark tourism [14]. For example, Tarlow [16] considered the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, a site that reached 2.2 million visitors in 2018 [42], as the pinnacle of European dark tourism. However, that site holds different meanings to people of different ethnicities and religious beliefs [26], which is reflected in the wide appeal of this site to a variety of people. All tourists to Auschwitz are usually seen as dark tourists [26], an approach that overlooks the possibility that the reasons for visiting and the experiences sought might be completely devoid of interest in death. In a study of visitors to Auschwitz, Biran et al. [26] reported that interest in death was the least common reason for visiting and that the main reasons were the desire to ‘see it to believe it’, learning and understanding, showing empathy for victims, and a desire for a connection with one's personal heritage [43]. Visitors to Holocaust-related sites may experience positive or negative impacts on their well-being [e.g., 44, 45], and positive and negative emotions may play a role as motivators behind visiting those sites [46]. A study by Magano et al. [47] found that people who visit more dark places and have more pronounced negative personality characteristics present higher values of tourist wellbeing.

Three main theories have been preponderant in studying the psychological well-being associated with dark tourism in the context of the Holocaust: i) Attention Restoration Theory (ART), ii) Stress Reduction Theory (SRT), and iii) Biophilia Hypothesis (BH). Attention Restoration Theory (ART) was used to elucidate the potential cognitive benefits of nature immersion. Ulrich's Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) focuses on restoration, which pertains to cognitive and behavioral functioning and physiological activity levels. Ulrich (1993) argues that humanity has historically spent most of its time in nature and that, despite modernization, humans have an inherent love of nature (i.e., biophilia). Consistent with this prominent theory, a systematic review by Shaffee and Shukor [48] established consistencies between research findings and the claims of the SRT. As with the previous theoretical frameworks, the Biophilia Hypothesis suggests nature immersion generates positive emotions.

A better understanding of the positive and negative impacts on the dark tourist's well-being could be helpful for the marketing and management of Holocaust memorial sites, as the promotion, digital communication, guiding, or storytelling design efforts could trigger visitors' interest and motivation for visiting the sites, thus increasing the number of visitors, and improving their satisfaction and well-being.

Is feeling well-being, as a consequence of dark tourism, a way of banalizing the horror? To answer our research question, we hypothesized that although dark tourism generates negative emotions, it also creates positive emotions that contribute to well-being.

The purpose of this study is threefold. Firstly, we intended to provide an updated SLR of dark tourism associated with Holocaust sites and visitors’ well-being. The second goal is to structure the findings into categories that provide a comprehensive overview of the topics. Lastly, the third goal is to identify which topics are not well covered, thus suggesting knowledge gaps.

The SLR includes contributions from 1985 to February 2022, namely, peer-review journals and books from reputable publishers. The paper includes a description of the applied methodology in Section 2, followed by the presentation of findings in Section 3, the analysis and discussion in Section 4, and the concluding aspects, including a summary of gaps and possible approaches for future research.

2. Methods

2.1. Systematic literature review

A literature review is a fundamental component of any research study. It can generally be described as a systematic way of collecting and synthesizing previous research [49]; a systematic literature review can be seen as a research method and process for identifying and critically analyzing relevant research, as well as for collecting and processing the respective data [50,51]. Literature reviews “play an important role as a foundation for all types of research”; a systematic literature review could “serve as the grounds for future research and theory” [51]. An SLR is specifically helpful in pinpointing and assessing arising tendencies within multi/inter-disciplinary research, and it is more suitable for framing and synthesizing a considerable volume of literature [52]. From the relevant literature assessment and analysis, possible research gaps may be identified [49].

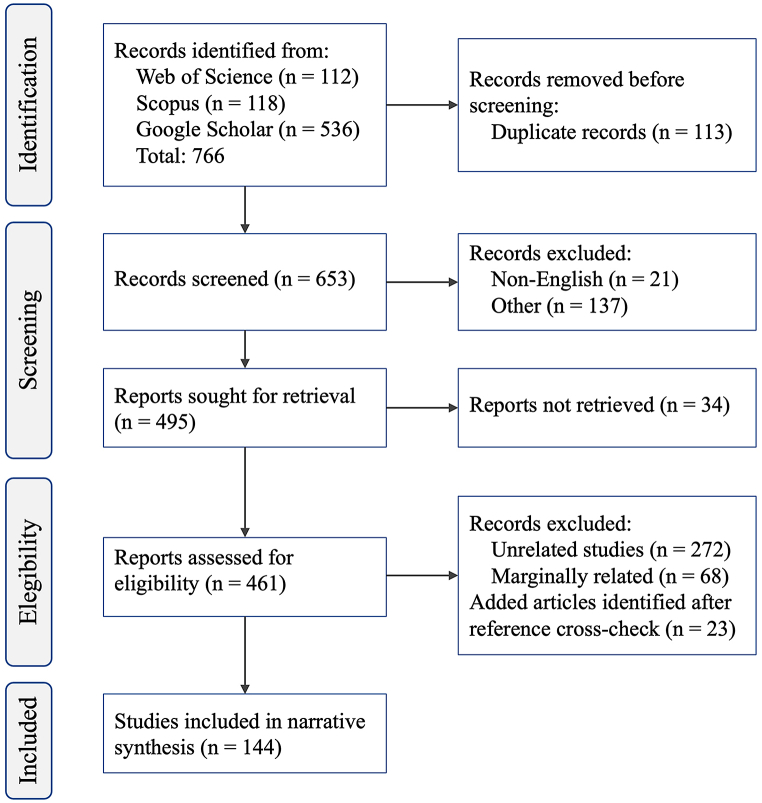

The “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) presents guidelines that allow for a “more transparent, complete, and accurate reporting of systematic reviews” in a way that the methods and results of the systematic reviews should provide enough “detail to allow users to assess the trustworthiness and applicability of the review findings” [53]. The PRISMA statement consists of a checklist of 27 items and a flow diagram made up of four phases (Identification, Screening, Eligibility, and Inclusion); it aims to help authors improve the reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [54].

2.2. Eligibility criteria

This systematic review adheres to the PRISMA guidelines [54], consisting of the mapping, analysis, and synthesis of the existing literature on Holocaust-related dark tourism and well-being. The criteria for the literature selection included articles in peer-reviewed academic journals, books, and book chapters written in English, published from 1985 to February 2022. The inclusion of records was not restricted based on when or where studies were developed; records that did not meet the inclusion criteria (Table 1) were outrightly excluded. Methodological decisions were based on the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS) [55]. The seven domains of bias addressed in the ROBINS-I assessment tool are: Confounding (selection bias, allocation bias, case-mix bias, channeling bias); Selection bias (inception bias, lead-time bias, immortal time bias); Bias in measurement classification of interventions (misclassification bias, information bias, recall bias, measurement bias, observer bias); Bias due to deviations from intended interventions (related terms: performance bias, time-varying confounding); Bias due to missing data (attrition bias, selection bias); Bias in the measurement of outcomes (detection bias, recall bias, information bias, misclassification bias, observer bias, measurement bias); and Bias in the selection of the reported result (outcome reporting bias, analysis reporting bias). Studies identified as meeting inclusion criteria were graded using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, generating a quality rating for each article [56] the components of which are: problem; values and preferences; quality of the evidence; benefits and harms and burden; resource implications; equity; acceptability; and feasibility.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria.

| Language: Publications written in English. |

|---|

| Types of publication: Journal articles, books, and book chapters. |

| Availability: Retrievable publications. |

| Eligibility: Focus on the aims and the research question the review addresses. |

The primary objective of this review was to provide an updated SLR of dark tourism associated with Holocaust sites and visitors’ well-being. The studies had to include at least two of the following three aspects: i) dark tourism, ii) the Holocaust, and iii) well-being.

Dark tourism was defined as visits or traveling, intentional or otherwise, to locations related to death, suffering, the macabre, and disgrace [1,[13], [14], [15]]. Holocaust tourism includes the description of sites related to World War II and the atrocities perpetrated against Jewish and other people. Well-being is defined as the emotional, psychological, and cognitive aspects of a person's life [57].

2.3. Information sources and search strategy

Carrying out the Identification stage of the PRISMA process, literature was identified by searching within the following databases: Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and Google Scholar. The searches were carried out by two researchers (JM and AL) who carried out the tasks independently. Three keywords were used in the search: “dark tourism”, “Holocaust”, and “well-being” (and the derivative “wellbeing”). Firstly, the researchers searched for the keywords together on Google Scholar's website, using the query string “dark tourism” and “Holocaust” and “wellbeing”/“well-being”, yielding 536 records. The same procedure was repeated on the scholarly database platforms of WoS and Scopus, searching abstracts, titles, and keywords, resulting in only one record from each database. For this reason, subsequent searches in WoS and Scopus databases combined any two of the referred three keywords. Keyword combinations are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Database search queries (key word combinations used).

| Query string | No. of records | |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | ||

| “DARK TOURISM” AND “HOLOCAUST” AND (“WELLBEING” OR “WELL-BEING”) | 536 | |

| Web of Science | Scopus | |

| “DARK TOURISM” AND “HOLOCAUST” AND (“WELLBEING” OR “WELL-BEING”) | 1 | 1 |

| “DARK TOURISM” AND (“WELLBEING” OR “WELL-BEING”) | 6 | 6 |

| “HOLOCAUST” AND (“WELLBEING” OR “WELL-BEING”) | 75 | 76 |

| “DARK TOURISM” AND “HOLOCAUST” | 30 | 35 |

2.4. Study selection

Search results were downloaded and to increase consistency and confirmation, each researcher, using a complete list, removed any duplicates. The resulting lists were compared and consolidated into one main list. Ordered alphabetically, the list of articles was divided into two sets (A-K and L-Z). Two researchers (JM and AL) independently and thoroughly scanned the records by title, abstract and full text to avoid personal bias while ensuring consistency with the review objectives. The motives for exclusion of records at the full-text screening stage were in accordance with the GRADE framework. At the full-text level, article eligibility was decided collaboratively. A database of information, based on the data extracted from each article, included type of record, language, authors, title, abstract, keywords, number of citations, year, URL, and DOI (if available).

As a result, a total of 766 records were identified. Duplicates were flagged by comparing DOI identifiers and document titles. Each potential duplicate was manually compared, removed, and merged when necessary. As a result, 113 duplicate records were removed. The Identification phase resulted in the screening of 653 records. Then, 21 non-English documents identified were removed. The remaining documents were re-checked for isolating and all publications other than peer-reviewed academic articles, books, and book chapters (e.g., conference papers/proceedings, book reviews, editorial notes, reports, bibliography lists, no full-text publications, and theses) were excluded to ensure a consistent standard for analysis; 495 documents were considered for retrieval, of which 34 were not retrieved. Consequently, the eligibility of 461 retrieved records was assessed. After discussion and resolution of eventual discrepancies between the researchers, by consensus, 189 publications were considered eligible. The subsequent step of full-text reading led to the exclusion of another 68 documents, although they would have been useful to contextualize the review (these records are referred to in the Introduction section). The last step allowed the inclusion of 23 articles identified after the record references had been cross-checked. Finally, 144 records were included (each cited) in the review for subsequent classification and analysis (Table 3). Fig. 1 depicts the PRISMA flowchart of the process carried out to identify the studies to be included in narrative synthesis.

Table 3.

Included publications.

| Number of records | Type of publication |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal article | Book | Book chapter | Other | ||

| Identification | |||||

| Google Scholar | 536 | 189 | 121 | 86 | 140 |

| Web of Science | 112 | 109 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Scopus | 118 | 98 | 2 | 8 | 11 |

| Total identified | 766 | 396 | 122 | 96 | 152 |

| - Duplicates | 113 | 81 | 12 | 8 | 12 |

| Screening | |||||

| Records screened | 653 | 315 | 110 | 88 | 140 |

| - non-English records | 21 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| - Records excluded | 137 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 137 |

| Records considered for retrieval | 495 | 303 | 104 | 88 | 0 |

| - Records not retrieved | 34 | 13 | 5 | 16 | 0 |

| Eligibility | |||||

| Reports assessed for eligibility | 461 | 290 | 99 | 72 | 0 |

| - Records out of focus | 272 | 138 | 88 | 46 | 0 |

| Eligible records | 189 | 152 | 11 | 26 | 0 |

| - Marginally related records (used in the Introduction) | 68 | 41 | 7 | 20 | 0 |

| + Articles identified after references cross-checked | 23 | 15 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Included | |||||

| Records included | 144 | 126 | 8 | 10 | 0 |

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of data identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process.

2.5. Study risk of bias assessment

This primary aim of the review was to determine the psychological impact on participants who visit Holocaust dark tourism sites from quantitative and qualitative studies. Secondary outcomes include other measures indirectly related to psychological well-being (depression, anxiety, positive and negative emotions) included in the studies. Quality was assessed using the GRADE system that provides a quality rating for each article [56] concerning consistency, precision, publication bias, risk of bias, and directedness. Of the 144 eligible studies (Table 4), we assessed 59.72% (86 of 144) as weak (high risk of bias), 21.53% (31 of 144) as moderate (moderate risk of bias) and 18.75% (27 of 144) as strong (low risk of bias). Only six studies did not fall under any category and scored 3 (high risk of bias).

Table 4.

Studies by type of outcome.

| Construct | Number of studies | Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dark tourism, Holocaust, and Well-being | 33 | Abraham et al. [58]; Bauer [59]; Buntman [60]; Christou [61]; Douglas [62]; Farmaki [15]; Farmaki and Antoniou [63]; Ioannides and Ioannides [64]; Kelly and Nkabahona [65]; Kidron [66]; Knudsen and Waade [67]; Lacanienta et al. [45]; Lee and Jeong [68]; Lennon [69]; Lin and Nawijn [70]; Lin et al. [71]; Liyanage et al. [72]; Mitas et al. [73]; Nawijn and Fricke [74]; Nawijn et al. [75]; Nørfelt et al. [76]; Oren et al. [44]; Prayag et al. [77]; Seaton [78]; Seraphin and Korstanje [79]; Sharpley and Stone [1]; Smith and Diekmann [80]; Stone and Sharpley [81]; Tarlow [16]; Wight [82]; Zhang et al. [83]; Zhang [84]; Zheng et al. [85] |

| Dark tourism and Holocaust | 43 | Applboim and Poria [86]; Ashworth and Hartmann [8]; Ashworth [35]; Beech [7]; Blankenship [87]; Brown [88]; Cohen [2]; Cole [89]; Commane and Potton [90]; Dalziel [91]; Duerden et al. [92]; Fisher and Schoemann [93]; Golańska [94]; Griffiths [41]; Heidelberg [95]; Isaac et al. [34]; Krisjanous [96]; Lennon and Foley [97], Leshem [98]; Lewis et al. [99]; Light [19]; Mionel [100]; Mostafa et al. [101]; Nawijn et al. [46]; Oren and Shani [102]; Oren et al. [103]; Petrevska et al. [104]; Phelan [105]; Pine and Gilmore [106]; Podoshen and Hunt [107]; Podoshen et al. [108]; Podoshen [36]; Podoshen [109]; Reynolds [110]; Richardson [111]; Richardson [112]; Rozite and van der Steina [113]; Sendyka [114]; Smith [115]; Wright [116]; Yan et al. [117]; Zhang et al. [118]; Zhang et al. [83] |

| Dark tourism and Well-being | 25 | Azevedo [119]; Barsalou [120]; Best [121]; Cave and Buda [122]; Collins [123]; Iliev [124]; Jordan and Prayag [125]; Jovanovic et al. [126]; Lamers et al. [127]; Laing and Frost [128]; Lv et al. [129]; Magee and Gilmore [130]; Martini and Buda [131]; Martini and Buda [11]; Maslova [132]; Nawijn and Biran [133]; Sharma and Nayak [134]; Sharma and Nayak [135]; Sharpley and Stone [136]; Sheldon [137]; Soulard et al. [138]; Sun and Lv [139]; Wang et al. [140]; Wang et al. [141]; Zheng et al. [142] |

| Holocaust and Well-being | 43 | Amir and Lev-Wiesel [143]; Bachner et al. [144]; Bar-Tur and Levy-Shiff [145]; Bar-Tur et al. [146]; Barel et al. [147]; Ben-Zur and Zimmerman [148]; Bezo and Maggi [149]; Bilewicz and Wojcik [150]; Braga et al. [151]; Canham et al. [152]; Carbone [153]; Carmel et al. [154]; Cohen and Shmotkin [155]; Corley [156]; Dalgaard and Montgomery [157]; Dashorst et al. [158]; Diamond and Ronel [159]; Elran-Barak et al. [160]; Felsen [161]; Fňašková et al. [162]; Glicksman [163]; Harel et al. [164]; Isaacowitz et al. [165]; Jaspal and Yampolsky [166]; Kahana et al. [167]; Kalmijn [168]; Keilson et al. [169]; Kidron et al. [170]; Letzter-Pouw and Werner [171]; Lev-Wiesel and Amir [172]; O'Rourke et al. [173]; Ohana et al. [174]; Oren and Shavit [175]; Raalte et al. [176]; Shemesh et al. [177]; Vollhardt et al. [178]; Shmotkin and Lomranz [179]; Shmotkin et al. [180]; Shrira and Shmotkin [181]; Shrira et al. [182]; Weinberg and Cummins [183]; Weinstein et al. [184]; Zeidner and Aharoni-David [185] |

Note. Multiple types of outcomes were found within individual studies. Categories were measured once within each study. Well-being included subjective self-report measures based on positive and negative affect, and mood. Dark Tourism included the description of the dark places where the study took place. Holocaust included the description of the places associated with World War II.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

3.1.1. Year wise publications

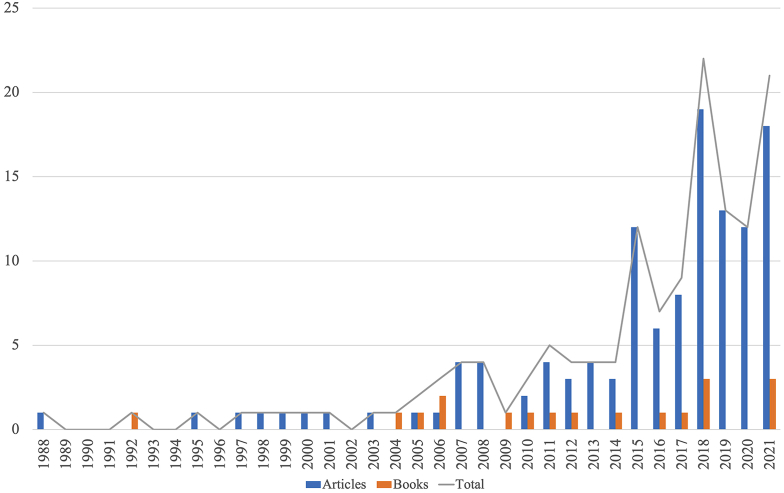

Fig. 2 depicts the publications spanning from 1988 to 2021, revealing a clear increase in recent years. About 77% of the publications included in the SLR were published in the last ten years, whereas 51% were published in the last five years, which signals the growing interest of researchers in the fields of dark tourism, the Holocaust, and well-being.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of included publications in the period 1988–2021.

3.1.2. Contributions from journals

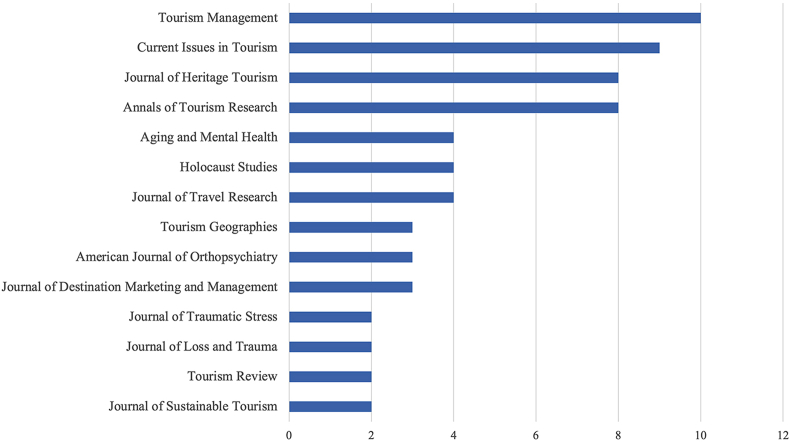

The articles included in the SLR were published in 76 journals, 14 of which published more than one article, as seen in Fig. 3. The journals Tourism Management (10), Current Issues in Tourism (9), and Journal of Heritage Tourism and Annals of Tourism Research (8) made the top-4 publishing journals, as nine journals were predominantly in the field of tourism, travel, and the Holocaust.

Fig. 3.

–Number of publications by journal. Note. The chart in the figure only includes journals (14) with more than one article.

3.2. Categorization

To answer our research question, we hypothesized that although dark tourism generates negative emotions, it also creates positive emotions that contribute to well-being. As such, we carried out our SLR to summarize the link between dark tourism, the Holocaust, and well-being.

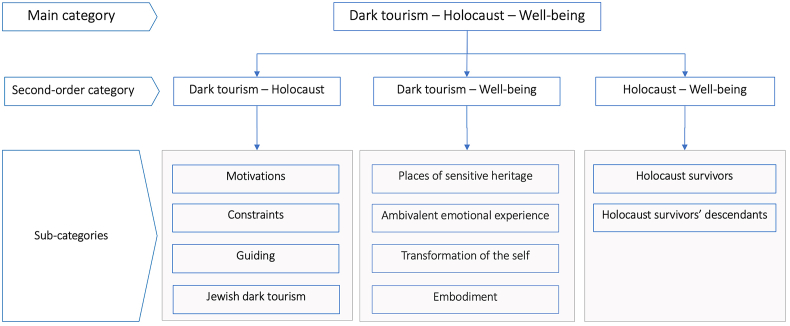

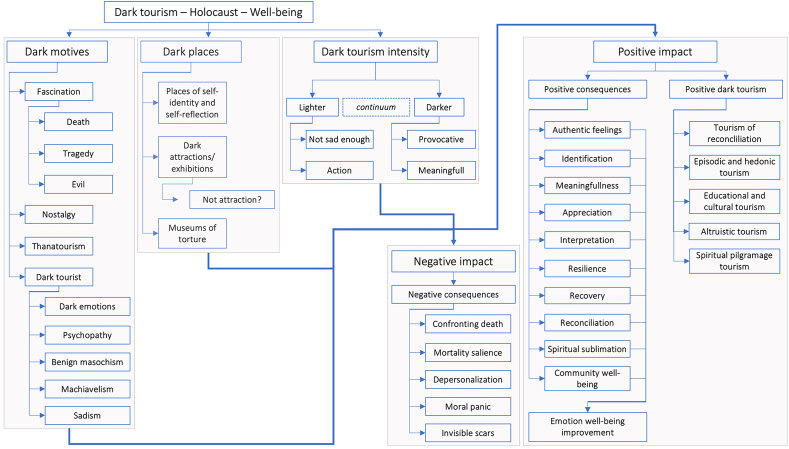

The results of the systematic literature review carried out globally point out a hierarchical structure of the following categories identified: the main category (Dark tourism - Holocaust - Well-being) and three second-order categories (Dark tourism - Holocaust, Dark tourism - Well-being, and Holocaust - Well-being). Furthermore, from these three second-order categories, different subcategories emerge that represent the most discussed topics in the respective second-order categories (Fig. 4). Therefore, we will analyze the main category and each second-order category separately.

Fig. 4.

SLR results: categories and sub-categories.

Regarding the second-order category “Dark tourism – Holocaust”, the sub-themes that deserve more attention from the authors are the motivations behind visiting such places and guiding. Concerning the second-order category “Dark tourism - Well-being”, the emphasis is on the ambivalent emotional experience that leads to the transformation of the self. Regarding the second-order category “Holocaust - Well-being”, the populations studied are mainly Holocaust survivors and their descendants, pointing toward intergenerational trauma.

3.2.1. Main category: dark tourism - holocaust - well-being

The main category resulting from this literature review is “Dark Tourism - Holocaust - Well-being”. Two major themes emerge from it: dark motives, dark places [82], dark tourism intensity [81], and another one related to the impact on well-being (negative and positive). Concerning dark motives [61], dark fascination [69], nostalgia [16], thanatourism [67], and the existence of the dark tourist [121] stand out, whose characteristics (possibly psychopathological) bring the tourist/person closer to this type of tourism. Dark tourism occurs in dark places (places alluding to the Holocaust), which are places of self-identity and self-reflection [82] but are also dark attractions in a continuum of intensity that promotes action (lighter dark tourism) or meaning (darker dark tourism) [81]. Moreover, this dark experience negatively impacts well-being, highlighting depersonalization [83] and moral panic [82]. However, it still also has positive consequences on well-being, especially recovery [186] and reconciliation [65]. Those positive consequences allow us to view dark tourism as being positive in its educational [2,80], cultural [15,62,80], and spiritual aspects [44,80,85,130,141], constituting tourism of reconciliation [65], episodic and hedonic [80] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Main category: Dark tourism – Holocaust – Well-being.

3.2.2. Second-order categories

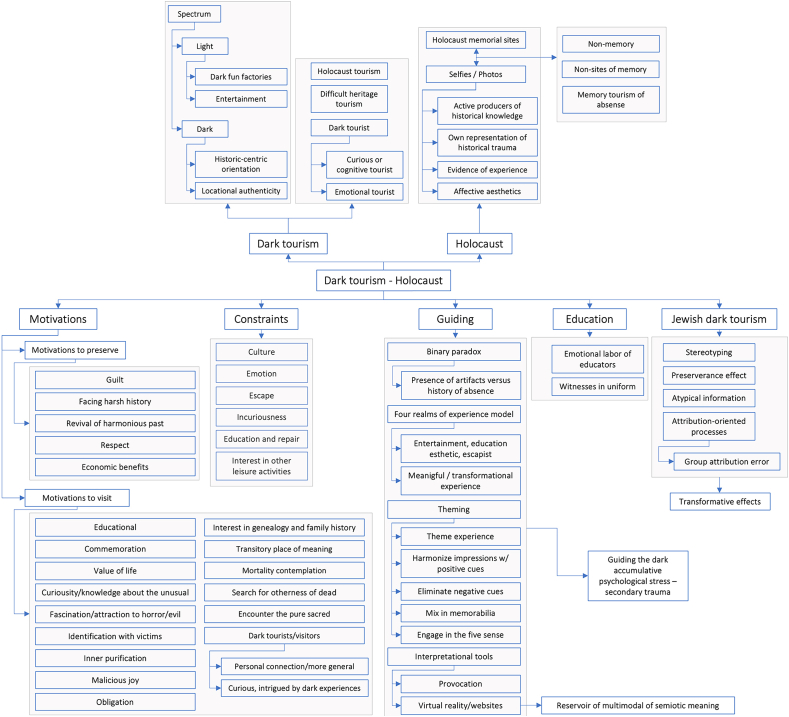

3.2.2.1. Dark tourism – holocaust

In this second-order category, “Dark tourism – Holocaust”, the different types of tourism according to intensity (lighter/darker) [14,187] stand out. It is also worth noting the different nomenclature used to refer to dark tourism (Holocaust tourism [19], difficult heritage tourism [94]), as well as the characterization of the dark tourist [7,26,117,121]. In relation to the Holocaust, its memory is preserved in places (or non-sites of memory) [114] and tourists appropriate this memory not only emotionally but also cognitively. Moreover, the literature highlights the controversy concerning taking photographs/selfies [91,110,115] in these places, either considering this practice disrespectful and inappropriate [115], or an active production of historical knowledge [110]. As a whole, this second-order category presents motivations, constraints, guiding, and Jewish dark tourism as subcategories. There is abundant literature on the motivations that lead people to visit Holocaust-related places [8,34,35,142], and some literature on the motivations for preserving those places [e.g., 104]. While the former is very different from the latter, from curiosity to the search for meaning, looking at the specific characteristics of dark tourists, the motivations for preserving this heritage are reduced to guilt, respect for victims, and economic benefits (Petrevska et al., 2018). With regards to the constraints suggested by the literature for not visiting these places (much fewer constraints than motivations), incuriousness and escapism stand out [83,118].

One of the subcategories of this second-order category is guiding, which analyzes the instruments available for contact between the visitor and the places. Essentially, the authors refer to the four realms of the experience model (entertainment, education, esthetic, and escapist) [106], theming [102], and interpretational tools [93,187]. Furthermore, the literature also discusses the roles of communication and information technologies in this activity. However, the binary paradox seems more salient in this subcategory [41], occurring in these Holocaust places, which often constitute repositories of artifacts in contrast with a history of absence [89].

Guiding is an activity that can lead to secondary trauma; educators [112] and guiding people [98], as well as Israeli soldiers (witnesses in uniform [86]) visiting sites of the Holocaust, can suffer from this secondary trauma. Dark tourism carried out by Jewish people often has a transformative effect [109], despite the negative emotional impact it can have on these dark tourists [87,107,108] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Second-order category: Dark tourism – Holocaust.

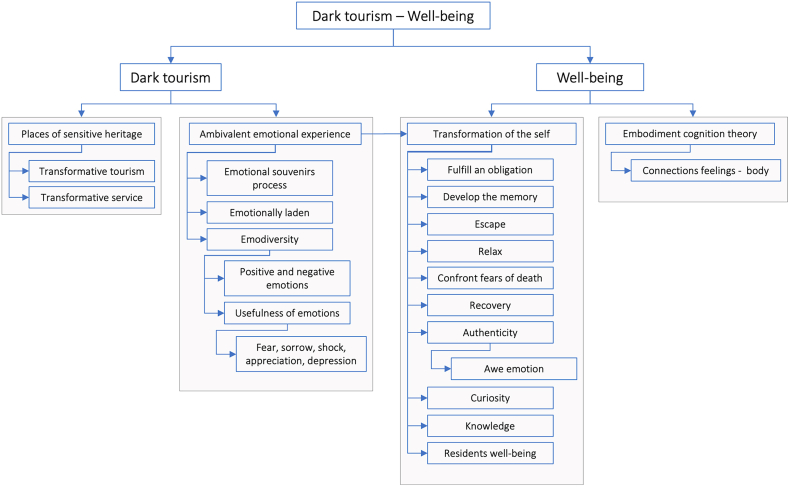

3.2.2.2. Dark tourism – well-being

From the articles selected to be included in the first category of secondary dimension, Dark tourism - Well-being, two subcategories emerged. On the one hand, dark tourism and, on the other hand, well-being. With regards to dark tourism, two themes were found, namely: characterization of dark tourism as a type of transformational tourism [138] and the ambivalent emotional experience [85] translated by expressions such as: “emotional souvenirs process” [122], “emotionally laden” [131], and “emodiversity” [140]. Concerning the second subcategory, Well-being stems from the ambivalent emotional experience of dark tourism as a driver of the transformation of the self [133], as well as the “embodiment” [139] that allows the relationship between feelings and the body (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Second-order category: Dark tourism – Well-being.

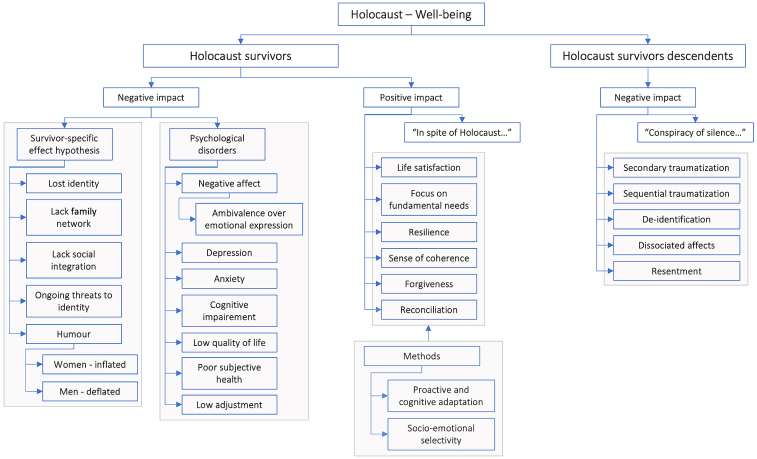

3.2.2.3. Holocaust – well-being

From the articles selected to be included in the second category of secondary dimension, Holocaust and Well-being, two themes stand out: Holocaust survivors and Holocaust survivors' descendants and their well-being. While the literature presents the Holocaust survivors’ well-being as being both positively and negatively impacted, the descendants of Holocaust survivors only show negative impact on well-being. The negative impact on the well-being of Holocaust survivors is consistent with the survivor-specific effect hypothesis [154], marked by loss and lack [143,163,167]. This impact manifests itself through cognitive deterioration [184], worse quality of life, worse health perception [174], and mood changes [143,173]. However, these survivors also show well-being, despite the Holocaust, through proactive and cognitive adaptation [160] and socio-emotional selectivity [165]. In turn, the descendants of Holocaust survivors seem to receive intergenerationally [158], secondary [150,168] and sequential trauma [169]; above all, the negative impact on well-being following a conspiracy of silence [151] (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Second-order category: Holocaust – Well-being.

4. Discussion

Most people have never heard the term dark tourism, also known as “difficult heritage tourism” and “Holocaust tourism” [94]. However, they may have been to dark tourist sites where they fulfill their curiosity and have an authentic experience that is communicated by interpreting the place and context [101]. Also, these transitory spaces may act as important moments in dark tourism experience [36]. The dark tourism spectrum in dark tourism sites is a continuum of less dark to most dark [14]; according to Stone [14], the darkest tourist sites have a history-centric educational orientation and locational authenticity; the ‘lightest’ sites ‘dark fun factories’ are places where “death and suffering are the backdrop for tourism sites with a strong entertainment component” [187]. In fact, “it is difficult to interpret these impulses as more than the simple gratification of curiosity or (…) a more profound metaphysical gloss on it, for the purposes of considering their own mortality. Dark tourism has always existed in some form or other. What did not exist was the term itself [188]. Richardson [112], through the lens of ‘emotional labor’, studied how educators manage their emotions in situ, finding a “complex interplay of emotion work and self-preservation that results in educators variously altering the extent to which they are ‘present’ and how they choose to withdraw themselves emotionally” (p. 247). Tourist guides are subjected to a form of secondary trauma (guiding tourists across themes and sites of death, horror, and genocide); Leshem [98] coined this phenomenon as Guiding the Dark Accumulative Psychological Stress. Richardson [111] also studied the emotional experience of teenage visitors and found that young people experience their visit as “an incomplete and ongoing process in their learning” (p. 77). Applboim and Poria [86] studied a heritage tourism experience – ‘Witnesses in Uniform’ (a trip to concentration camps in Poland for Israeli Defense Forces personnel), having found that this journey was a reward for their subordinates' good behavior, with the aim of affecting their functioning as military personnel and as citizens. Despite all criticism, Oren and Shani [102] referred to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum as an example of a well-conducted theming with potential for dark tourism sites by reaching broad audiences and emotionally engaged visitors. Also, “participants' evaluations of seminars for European teachers at Yad Vashem indicate that the location is an important aspect of a meaningful encounter with the subject” [2]. Griffiths [41] identified a binary paradox of the guided group tours offered by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum: “the tours assert presence through artifacts, which diminishes a history characterized by absence; they are presented as vehicles of fact when they rely on fictional mechanisms for their narrative constructions; they claim to represent victims, yet employ problematic models of representation; and they assert the significance of the Judecoide, yet downplay the importance of the Birkenau site” (p. 195). The Four Realms of the Experience model (entertainment, education, esthetic, and escapist) [106] supposes that the more guests are engaged in the experience, the more likely it is that the experience is meaningful or transformational [92]. Theming consists of five principles: Theme the experience; Harmonize impressions with positive cues; Eliminate negative cues; Mix in memorabilia; and Engage the five senses - THEME [106,187]. The THEME Model [106] is based on a framework to develop a particular theme or motif for a site, a dominant idea or organizing principle that influences every staged element of an experience. Ward and Hill [187] stated that some interpretational tools enhance the visitor experience, as provocation is particularly well-suited to Holocaust tourism experiences because it allows visitors to think deeply about the experience. Fisher and Schoemann [93] proposed that visits to dark tourism sites with virtual reality should accompany current models of dark tourism and “utilize the affordances of the medium to facilitate new opportunities for ethical compassion and understanding in the mediation of mortality” (p. 577). Also, Krisjanous [96] stated that “websites are a reservoir of multimodal semiotic meaning” (p. 348).

“The attitude of locals towards dark heritage sites (…)” cannot be perceived “without understanding the attitude towards death sites and cemeteries in the cultural context” [113]. However, including places of death and tragedy in tourism product promotions creates many problems. Phelan [105] studied the relationship between dark tourism consumption and mortality within contemporary society and considered mortality contemplation a major motivation to visit dark places. Smith [115] identified three troubling features: the pre-internet phenomenon of dark tourism, the post-internet trope of ‘selfies at Auschwitz’, and genealogy websites. In contrast, Reynolds [110] stated that “tourists to Holocaust memorial sites become active producers of historical knowledge as they generate their own representations of historical trauma” (p. 334), reflecting on the authentic and inauthentic dimensions of their experiences. Also, Dalziel [91] revealed that numerous pictures taken at the Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial site are not taken mindlessly and enumerated the reasons why individuals take photographs in those dark places: (i) visitors photograph recognizable sights as evidence of their experience, confirming they were there; (ii) aesthetically “pleasing” pictures that provide a distance between the photographer and the horrific views; (iii) educational role as they are records of the experience; (iv) celebrate the victims by apprehending other scenes of remembering: the placing of stones, according to the custom in Jewish culture; flowers and garlands left at locations like the Wall of Death; Jewish youth groups carrying Israeli flags, assembling to pray or celebrate the continuation of Jewish life; (v) express the value of life and survival through their pictures, standing as a testament; and (vi) visitors attempted to position themselves as prisoners and feel the emotions they may have had. Sendyka [114] considered that Susan Silas (photographer) problematizes the memory and identified various types of non-memory, whereas her camera is driven to places that are “the non-sites of memory” (p. 1). Also, Cole [89] explained the concept of memory tourism of absence (directing visitors to see the places where Jews lived before the Holocaust) and considered that it can and needs to be historicized. Lennon and Foley [97] reported that the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., contains more than 5000 artifacts (photographs, uniforms, letters, and a rail car used to take Jewish prisoners to the death camps), as this concern with replication is central to Holocaust memory. Hodgkinson [189] identified the moral dilemmas of Holocaust representation, such as its commodification for entertainment and tourism. However, according to Wright [116], if the brutal and murderous nature of humans continues, the potential for tourism in which death is a product of entertainment for a wealthy elite is a reality in the future. Auschwitz-Birkenau is the main example provided by researchers of the darkest tourism sites and was used to distinguish dark tourism and thanatourism; however, Mionel [100] found that dark tourism comprises thanatourism, but it does not constitute a distinctive form of tourism. Also, Light [19] considered that research had not yet demonstrated that dark tourism and thanatourism are distinct forms of tourism, and they appear to be little different from heritage tourism.

4.1. Dark tourists’ trivialization of the holocaust dark tourism

Our working hypothesis raised the question as to whether the positive impact of dark tourism on well-being is a way of banalizing the horror? The results of the systematic literature review do not allow the hypothesis to be confirmed, as the positive impact is almost always seen as the result of something transformative [92,109,127,133,138]. The trivialization of horror is not a new concept in the scope of dark tourism. In fact, and according to Heidelberg [95], dark tourism “commodification of death and suffering could lead to a trivialization of the dark event itself, a ‘Disneyfication’ of tragedy“ (p. 76). Also, concerning the Holocaust, Commane and Potton [90] stated that “the hint of pleasure in trivializing trauma and horror shows how generic narratives about the Holocaust are neutralized and mocked, even if the user (…) is fully aware of the cultural conditions, ethics, and conscience that shape appropriate response and respect” (p. 175). However, most authors approach the trivialization of horror from the perspective of the promoter of the tourist event or site and not from the point of view of the dark tourist, the only exceptions being those visitors who address the role of selfies and photographs in the context of dark places [62,82,115]. There seems to be a gap in the literature regarding the trivialization of horror in the context of dark tourism related to the Holocaust from the perspective of the dark tourist. Indeed, there are not many studies about dark tourists.

4.2. The impact of tourists’ personality dimensions on the ability to banalize the horror

According to Lewis et al. [99], dark tourists are “curious, interested, and intrigued by dark experiences with paranormal activity, resulting in travel choices made for themselves based on personal beliefs and preferences, with minimal outside influence from others” (p. 1); those that exist [e.g., 76, 126] focus on dimensions of the tourist's personality, per se, but do not establish the relationship between these characteristics and the ability to vulgarize or even neutralize horror. Beech [7] found two distinct types of visitors: those with personal connections to the site and those more general visitors. For the first type, a concentration camp is not comparable with other tourism products, but, with the progression of time, it is most likely that it will become a more conventional tourist attraction; for this type of visitor, a concentration camp such as Buchenwald exists in an ethical dimension. Also, Yan et al. [117] identified two types of dark tourists: the curious one that engages cognitively by learning about the issue and the emotional one that reacts emotionally to the “dark” space influence. Based on Deleuze and Guattari's work on aesthetics, Golańska [94] developed the concept of ‘affective aesthetics’ which refers to a “bodily process, a vital movement that triggers the subject's passionate becoming-other, where ‘becoming’ stands for an intensive flow of affective (micro)perceptions” (p.773). Those who are interested in experiencing the death and suffering of others [61] for enjoyment, pleasure, and satisfaction are dark tourists [121]. Furthermore, the notion of benign masochism describes a person's tendency to embrace and seek pleasure through safely playing with a stimulating level of physical pain and negative emotions [76]. Jovanovic et al. [126] found that Machiavellianism was positively related to the preference for dark exhibitions; psychopathy to a preference for visiting conflict/battle sites; and sadism was negatively related to the preference for fun factories as an additional type of dark tourism site. However, do these personality dimensions precede the ability to trivialize the horror? Another gap in the literature concerns the personality dimensions of the tourist who does not visit dark places, in light of what has already been studied with dark tourists.

4.3. Understanding the constraints to visiting dark tourism places

There are several reasons for tourist fascination with sites associated with death and tragedy [61], namely, the interest in specific macabre exhibitions and museums out of curiosity and interest in death [190]; the entertainment-based museums of torture [121]; the fascination towards evil [69]; the nostalgia [16]; educational purposes [2]; the interest in genealogy [60]; cultural interests [63]; and ‘pilgrimage’ tourism [64]. However, Sharpley's model [191], that integrated dark tourism’ supply and demand, stated that not all ‘dark tourism attractions’ are intended to be ‘attractions’, and not all tourists who visit these attractions are strongly interested in death. Ashworth [35] and Ashworth and Hartmann [8] suggested three main reasons for visiting dark sites: curiosity about the unusual, attraction to horror, and a desire for empathy or identification with the victims of atrocity. Other authors presented other reasons: secular pilgrimage; a desire for inner purification; schadenfreude or malicious joy; “ghoulish titillation”; a search for the otherness of death; an interest in personal genealogy and family history; nostalgia; a search for ‘authentic’ places in a commodified world; a fascination with evil; and a desire to encounter the pure/impure sacred [19]. Petrevska et al. [104] also found several motivations for dark tourism, such as guilt, interest in national history, the revival of a glorious past, economic benefits, display of sympathy, and dark tourism development. Zheng et al. [142] also found three motivational factors, the most important being the respondents' obligation to visit the site. The motivations found by Isaac et al. [34] were memory, gaining knowledge and awareness, and exclusivity. Also, Petrevska et al. [104] stated that the motivations for preserving such dark sites are guilt, facing harsh history, emphasis on dark tourism, the revival of a harmonious past, respect, and economic benefits. Brown [88] considered that “retail operations of dark tourism sites are highly complex and fraught with potential issues relating to taste and decency” (p. 272). However, there is not the same number of studies on the constraints to visiting dark places. Zhang et al. [118] studied the intrapersonal constraints to visiting dark sites and found four sub-dimensions: culture, emotion, escape, and incuriousness. Zheng et al. [142] found seven dimensions of constraints with the most important being an interest in other leisure activities. This asymmetry in the (greater) interest in the motivations behind visiting dark places to the (lesser) detriment of constraints raises some questions, namely, whether it is more difficult to access tourists who do not visit dark places than those who visit them. This gap in the literature (the need to better understand the constraints that prevent tourists from visiting dark places) prevents a broader knowledge of the true dark tourist.

4.4. Holocaust survivors and their descendants’ well-being

Holocaust survivors (HSs) (direct and indirect) presented worse well-being than the control groups. Fňašková et al. [162] found that the psychological and neurobiological changes across the life of people who outlived severe stress were identified more than seven decades after the Holocaust; severe stress in children and young adults has an irreparable lifelong effect on the brain. Also, Ben-Zur and Zimmerman [148] found that the Holocaust groups scored higher than the comparison group on ambivalence and negative affect above emotional expression and scored lower on psychosocial adjustment; the authors also found that the consequences of the Holocaust are unmistakable sixty years later, emphasizing the role of ambivalence over emotional expression in the Holocaust survivors' well-being. Amir and Lev-Wiesel [143] studied post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, subjective quality of life, and psychological distress in a group of adults who were child Holocaust survivors and who were not aware of their identity. Results showed that survivors unaware of their origin had a lower psychological, physical, and social quality of life (QoL) and higher somatization, depression, and anxiety scores than survivors with a known identity. Jaspal and Yampolsky [166] studied how a group of young Israeli Jews understood and defined their ethnonational identities, focusing on the role of social representations of the Holocaust in the construction of Israeli-Jewish identity; three themes were reported: perceptions of the Holocaust as a personal and shared loss; re-conceptualizing the Holocaust and its impact on intra/intergroup relations; and the Holocaust as a heuristic lens for understanding the Israeli-Arab conflict. Shmotkin et al. [180] found that women were more likely to be Inflated (high happiness and high suffering) whereas men were more likely to be Deflated (low happiness and low suffering); it was more probable that Holocaust survivors would be Deflated and Unhappy in the negative though not in the positive moments. Weinstein et al. [184] found that concentration camp/ghetto survivors had poorer global cognitive performance and attention compared to individuals who were not exposed to Holocaust conditions. Isaacowitz et al. [165] discovered that socioemotional selectivity related to positive mental health in all groups besides the Holocaust survivors, who usually exhibit high negative affect, and social networks of other survivors also undergoing distress. Ohana et al. [174] found that the Holocaust survivors' subjective health was significantly lower and associated with decreased quality of life. O'Rourke et al. [173] found that levels of depressive symptoms reported by HSs were significantly greater than other Israelis and older Canadians. Canham et al. [152] found a higher level of subjective well-being among Canadians in comparison to both comparative Israeli groups HS vs. non-HS; also, depressive symptoms were significantly more elevated among female survivors than in the other two groups; the Israeli women groups had higher levels of anxiety than Canadians. Glicksman [163] examined the experience of Holocaust survivors in community-based and facility-based long-term care and found differences in certain aspects of mental health and emotional well-being and also found that these differences are associated with the lack of a network of family members as compared to American-born Jews. Shemesh et al. [177] found that elderly survivors were significantly more distressed than the comparison group. People in hiding, ghettos, labor, or death camps scored higher than survivors in countries occupied by the Nazis that bypassed those experiences; sleep disorders were more frequent among survivors than their counterparts. In addition, among survivors, social activities contributing to well-being were more confined. Podoshen and Hunt [107] studied why many Jewish tourists avoid tourism to historical heritage sites and found that some tourists avoid travel because of the paucity of Jewish life in the areas surrounding sacred sites, leading to the perception that anti-Semitism is still there. Podoshen et al. [108] studied the psychological processes of global Jewish tourists and local hosts surrounding historic Holocaust sites in Europe; they found the following processes: stereotyping, the perseverance effect, and the role of atypical information with consequences for collective memory and narrative. Podoshen et al. [108] feared that current Holocaust tourism and its marketing strategies might bring a disconnect between tourists and hosts in Eastern Europe. Podoshen [109] explored how Jewish Holocaust tourists organized discourses, made sense of meanings, and engaged with material geographies in an environment of renewed global anti-Semitism and found that certain happenings have a transformative effect. Blankenship [87] stated that many Jews feel apprehension about visiting Germany; however, numerous memorials and museums dedicated to the Holocaust assure Jewish tourists that the nation is devoted to educating and repairing their relationship with the global Jewish community.

Shmotkin and Lomranz [179] found that the long-term effects of the Holocaust on the survivors' subjective well-being are traceable but require a differential approach to the study groups and the facets of subjective well-being. Nevertheless, although Kahana et al. [167] stated that holocaust survivors living in Hungary experienced several postwar periods as highly stressful in addition to the trauma of the Holocaust, they also found that survivors living in the United States, particularly those living in Israel, portray better family life and social and psychological outcomes; on the other hand, survivors living in Hungary point to a lack of social integration and ongoing threats to identity, along with fears about the rise of anti-Semitism, as factors that may adversely impact the maintenance of psychosocial well-being. Bar-Tur et al. [146] found that past traumatic losses had an impact on well-being in the aging; however, while Holocaust losses had a negative impact, traumatic personal losses had a positive impact. Zeidner and Aharoni-David [185] found no evidence for the moderating or “buffering” effect of survivors’ sense of coherence (SOC), but supported indirect impacts of SOC on the relationship between memory traces of precise traumatic experiences and adaptive effects; it is very likely that survivors who had painful experiences throughout the Holocaust had to use their strength and coping ability and that prevailing during those horrific years, might have led to a more powerful feeling of meaning and coherence, leading to a greater sense of mental health as they grew old.

However, HSs present high life satisfaction; Bachner et al. [144] found that it may be not despite but because of experiencing early life trauma, juxtaposing early years with the comparatively good conditions of their lives today. Cohen and Shmotkin [155] found that Holocaust survivors reported significantly lower happiness in their anchor periods than the comparison groups; happiness and suffering in Holocaust periods (i.e., anchor periods during the Holocaust), when juxtaposed with happiness and suffering in non-Holocaust anchor periods (i.e., anchor periods which occurred before or after the Holocaust), significantly related to the survivors' present happiness and suffering. Elran-Barak et al. [160] argued that aging Holocaust survivors leaned to concentrate on more vital necessities (e.g., health); in contrast, their peers tended to focus on a broader range of needs (e.g., enjoyment). Aging people in Israel employ proactive (e.g., health) and cognitive (e.g., abiding by the present) adaptation processes, no matter what their known history during the war. Harel et al. [164] concluded that better health, lower emotional coping, higher instrumental coping, and lesser social concern were important predictors of psychological well-being in survivors and control groups. Amidst survivors, those four variables, together with being married, having more infrequent life crises, contact with co-workers, and not being surrendered to fate, explained 52% of the psychological well-being variance. Among control groups, these four variables, along with an easygoing personality style and good communication with one's spouse, explained 36% of the psychological well-being variance. Bar-Tur and Levy-Shiff [145] and Shrira and Shmotkin [181] found that even after immense trauma and rush decline related to old age, the past can hold life agreeable, as suggested by the more powerful relation of past happiness, compared to past grief, with life satisfaction. Nonetheless, past suffering was related to life satisfaction among the Holocaust survivors and displayed a more substantial effect among most old parties. Canham et al. [152] indicated that perseverance, survival, and resilience were essential to participants across the war and how these topics explained their choices and understanding of their lives. Resilience and remembrance are continuous and interconnected processes through which survivors adjust their previous lives to the present. O'Rourke et al. [173] found that early life trauma does not appear to fundamentally affect associations between reminiscence and health, as these findings underscore the resilience of Holocaust survivors. Barel et al. [147] studied the long-term sequelae of genocide and found that Holocaust survivors were less well adjusted; in particular, they showed substantially more posttraumatic stress symptoms yet remarkable resilience; also, the coexistence of stress-related signs and adequate adaptation in other areas of functioning may be attributed to the distinctive characteristics of the symptoms of the Holocaust survivors, who combine resilience with defensive processes. Finally, living in Israel instead of elsewhere can be a protective factor regarding psychological well-being [147]. Corley [156] discussed the intersection of the creativity and resilience of artists who survived the Holocaust and how these creative expressions have enhanced personal and community well-being.

The Holocaust disrupted the generational transmission of family health, and daily efforts are needed to invert the consequences of the Holocaust and establish relations with succeeding generations. Shrira et al. [182] noted that transgenerational impacts of the Holocaust may be more substantial among middle-aged OHS as they once suffered from early turbulent natal and postnatal conditions and now confront age-related decline. Nevertheless, middle-aged OHS may successfully preserve the strength they presented at a younger age. OHS, specifically those with two survivor parents, conveyed a more elevated sense of well-being but more physical health issues than the comparison group. Parental trauma incidents could evolve into family secrets, promoting the intergenerational transmission of behavioral patterns and suffering similar to the patterns seen in families where incest and violence have been transmitted across generations [172]. Dalgaard and Montgomery [157] carried out a systematic review of trauma communication in refugee families and found that a “conspiracy of silence” was the cause of suffering within the families of Holocaust survivors [151]. Bezo and Maggi [149] investigated the perceived intergenerational impact of the forced starvation-genocide and reported adverse physical health outcomes and adverse well-being across three generations. Primarily survivors' descendants declared that the mass trauma generated psychological, biological, and social processes that have negatively impacted physical health throughout generations. Dashorst et al. [158] studied the intergenerational consequences of the Holocaust on offsprings' mental health and found that parent and child characteristics and their interaction contributed to the development of psychological symptoms and biological and epigenetic variations; also, parental mental health issues, attachment quality, perceived parenting, and parental gender impacted the mental well-being of their descendants. Moreover, bearing two survivor parents led to more mental health issues than holding one parent. At last, Dashorst et al. [158] found that Holocaust survivor offspring showed a heightened vulnerability to stress in the face of actual danger. Letzter-Pouw and Werner [171] found that survivors' intrusive memories were related to the loss of parents in the Holocaust and their symptoms of distress. The latter was related to the offspring's perceived transmission of the trauma of the mothers, which was associated with more symptoms of distress among offspring. According to Letzter-Pouw and Werner [171], due to female survivors' uncompleted mourning processes and subsequent suffering from intrusive memories, the emotional burden of the Holocaust was transmitted to the eldest offspring and caused them more symptoms of distress. Kalmijn [168] stated that the hypothesis of secondary traumatization supposes that youngsters brought up by parents who were traumatized by warfare show more mental health issues than other children. Adults whose parents suffered from World War II held poorer mental health and underwent more negative life circumstances. Furthermore, traumatized parents have more unsatisfactory relationships with their children when they become adults. Bilewicz and Wojcik [150] concluded that the syndrome of secondary traumatic strain was observed among 13.2% of high school visitors to the Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial museum. Furthermore, empathic responses to the visit to Auschwitz (e.g., more prominent inclusion of victims into the self) were related to increased secondary traumatic stress one month after the visit.

Felsen [161] stated that adult children of Holocaust survivors presented “accentuated sibling differentiation and de-identification, manifested in the respective family roles of each sibling, their relationships vis a vis the parents, and also in the siblings' general adaptation styles” (p. 1), accompanied by a negative quality of the sibling relationships. Felsen [161] proposed that “(dissociated) affects and enactments of un-synthesized parental trauma infuse implicit and explicit interactions in family life with survival themes and with intense concerns for the parents' emotional well-being and polarize normative processes of sibling differentiation” (p.1). Felsen [161] stated that resentments cause dissolution of ties between siblings and their families in adulthood as these processes are an “intergenerational transmission of effects related to parental trauma that extend beyond the parent-child dyad, influencing the matrix of relationships in the family-as-a-system, and damaging the siblings' bond” (p.1). Raalte et al. [176] found that the quality of postwar care arrangements and existing physical health alone forecasted a lack of well-being at an old age. Moreover, the lack of fine care after the ending of World War II is related to lower youngest Holocaust child survivors' well-being, even after an intervening time span of six decades, validating Keilson's idea of sequential traumatization [169] enhancing after-trauma care in lowering the consequence of early childhood trauma. Weinberg and Cummins [183] found that offspring of Holocaust survivors (with two survivor parents) reported lower general positive mood than non-OHS. Oren and Shavit [175] examined how the Subjective Holocaust Influence Level (SHIL) of Holocaust survivors' offspring (OHS) is reflected in their daily life, habits, and well-being and found that higher SHIL correlated with increased worry, as they are more suspicious of others, have higher anxiety concerns about the future, feel the need to survive, risk aversion, self-rated health, and unwillingness to discard food. Kidron et al. [170] questioned the pathologized and vulnerable descendants of the Holocaust and found unique local configurations of emotional vulnerability and strength in these descendants. “Respondents normalize and valorize emotional wounds describing them as a “scratch” and as a “badge of honor” (…). Results point to ways that resilience and vulnerability may interact, qualifying one another in the process of meaning-making” (p. 1). Diamond and Ronel [159] started from the principle that forgiveness is effective in helping to reduce anger, stress, and despair and in cultivating an overall sense of well-being following man-made traumatic experiences and studied the case of Eva Mozes-Kor, a child Holocaust survivor and a “Mengele twin,” who extended forgiveness to her direct perpetrators. Findings indicate a life-changing conversion with the lasting effects of high interpersonal, intrapersonal, and spiritual integration levels. Carbone [153] questioned the causal relationship between the representation of war and the promotion of peace and suggested the use of the ‘the forgiveness model’ to give rise to a different kind of war museum narrative along with a “theoretical model on tourism and peace based on the conception of war-related attractions as local infrastructures for peace” (p. 565). Vollhardt et al. [178] carried out four experiments in the context of dark events (namely, the Holocaust) and studied the consequences of experiencing acknowledgment (as opposed to the lack of acknowledgment) of documented ingroup victimization on psychological well-being and intergroup concerns. Players in the acknowledgment condition noted higher psychological well-being and remarkable readiness to reconcile with the former perpetrator group compared to participants in the no acknowledgment condition and a neutral baseline control condition. In short, although some authors found a negative impact on the well-being of Holocaust survivors, others managed to find positive aspects despite the negative ones. However, when addressing the well-being of the survivors' descendants, most authors find a negative impact of this transgenerationality on well-being. This “apparent” contradiction may constitute another gap in the literature, with the need to study the few survivors that remain and their own descent.

4.5. Holocaust dark tourism's positive and negative impacts on well-being

Dark tourism's negative impact on well-being is well documented. The literature presents the negative impact of dark tourism on well-being; the negative and positive aspects; and, finally, the positive aspects.

Sharpley and Stone [1] identified five factors that ensure the effectiveness of heritage sites (the nature of the cruelty perpetrated; the nature of the victims; the nature of the perpetrators; the high-profile visibility of the original event; and the survival of the record), by ensuring emotional impact. Liyanage et al. [72] showed that the feelings of sadness, depression, anger, and existential questions could haunt visitors for some time after visiting a concentration camp. Abraham et al. [58] studied the emotions of the victims' descendants in visiting dark tourism sites and found that the image of these sites was a mediator between emotions of animosity and grief. Bauer [59] studied the impact of death as an attraction of travelers whose scars remain invisible, especially on those with a diagnosed mental illness. Moreover, Prayag et al. [77] apprised mortality salience and significance in life for locals visiting dark tourism sites. Finally, Zhang et al. [83] stated that self-categorization was evident in visitors' experience of disaster sites, as depersonalizing statements tended to be other-focused. According to Knudsen and Waade [67], thanatourism is a means of producing ‘authentic feelings’, as visiting thanatouristic sites triggers certain emotions [192], namely, ‘dark’ emotions [e.g., pain, horror, sadness; [193]]. Wight [82] stated that besides emotions typically identified in studies of dark tourism (e.g., sadness, empathy), there is some moral panic towards ‘other’ tourists at Holocaust heritage sites and anxieties towards the Holocaust spaces as tourist attractions. Wight [82] discussed the selfies at Holocaust memorial sites, considering them an offense and a normalized form of self-expression; Wight [82] also considered that museums are places of ‘self-identity work’ and profound self-reflection. However, simplistic interpretations of dark selfies deny the complexity of the “trauma selfie as a cultural practice and what this act might reveal about new modes of witnessing stemming from new technologies” [62].

However, Kidron [66] found that “co-presence in sites of atrocity enables the performance of survivor emotions tacitly present in the home, thereby evoking descendant empathy and identification” (p. 175). Also, Nawijn and Fricke [74] showed that visitor emotions in a concentration camp are more intensely negative than positive emotions, despite certain negative emotions also having the power to broaden and build. Liyanage et al. [72] also found that other forms of existential self-reflection were common, including a sense of appreciation for the value of life, freedom, and quality of life. Oren et al. [103] reported the co-existence of positive/ pleasant and negative/ unpleasant emotions such as pride, satisfaction, frustration, sadness, and anger that emerge at a heritage site, yet expressed the centrality of negative emotions. Oren et al. [44] found that negative emotions contribute to visitors’ satisfaction, and the perceived benefits derived from the visit. Furthermore, it is important to “reveal how the balance between fear and loathing, and laughter and liking are reconciled in the dark tourism experience” [78]. Nawijn et al. [75] stated that the effects of personality on meaning in life were marginal; only emotion of interest positively contributes to finding positive meaning in life. Also, Nawijn et al. [46] found that although most respondents expect to feel disgust, shock, compassion, and sadness, individuals close to the Holocaust expect to feel most emotions more intensely (mainly positive emotions, such as pride, love, joy, inspiration, excitement, and affection); from the viewpoint of the offenders, they mainly expect to feel negative emotions, whereas from the point of view of the victims, they also expect positive emotions. Concerning the positive impact of dark tourism on well-being, Smith and Diekmann [80] demonstrated the complexity of the relationship between well-being and tourism with a diversity of experiences: (i) episodic, hedonic forms of tourism; (ii) educational, cultural tourism; (iii) spiritual pilgrimage trips that enhance a sense of existential authenticity; and (iv) trips that imply altruistic or ethical dimensions (e.g., volunteer tourism).

Several authors tried to answer the question of how dark tourism can convey well-being: some see dark tourism as a mechanism of resilience that helps a community to recover after a disaster; others see the pedagogical functions of dark tourism as a way to develop empathy with the Other's pain [79]. Other authors considered that dark tourism improves tourists' emotional and spiritual well-being [44,130]. Reconciliation is the common aim of the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, based on the Holocaust, the New York Tolerance Center, and the Jerusalem Centre for Human Dignity, as it improves well-being, as interpretation is central to reconciliation [65]. According to Wang et al. [194], interpretation quality is essential for tourists to appreciate the benefits of dark tourism sites; besides, dark tourists' interpretation satisfaction and benefits gained will positively impact their overall satisfaction. Some criteria must be observed in the tourism of reconciliation, namely, location (a site to which visitors are attracted), presentation (should ensure a sense of place), development and maintenance (especially through donation), and collaboration with non-tourism interests [65]. Wang et al. [194] also identified some benefits of dark tourism: individual spiritual sublimation and thoughts and feelings for the collective and the country. Social capital happens through social interaction and ultimately contributes to community well-being [Bowdin, 2011, cit in 186]. According to Wang et al. [194], interpretation quality is an important antecedent for tourists to appreciate the benefits they obtained from dark tourism sites; in addition, their interpretation satisfaction and benefits gained will positively impact their overall satisfaction.

Lacanienta et al. [45] found that lighter dark tourism experiences (e.g., execution square and the ghost tour) were more affectively pleasing and raised a stronger sense of agency (inclination to act) than darker tourism experiences; the latter (e.g., Auschwitz and Schindler's Factory) were more provocative, valued, and meaningful. Also, Lee and Jeong [68] found that a sense of sadness contributes to establishing meaning [46]; some tourists reported less satisfaction when a visit is not ‘sad enough’ [118]. “Indeed, consuming dark tourism may allow the individual a sense of meaning and understanding of past disaster and macabre events that have perturbed life projects” [1]. Human identity could become salient during the Holocaust [195], contributing to the psychological shift [84]. Zheng et al. [85] stated that positive emotional experiences (i.e., appreciation) have a direct positive effect on spiritual meaning, but not negative emotional experiences: sorrow, shock, and depression only indirectly create meaning. Lin and Nawijn [70] stated that positive emotions fluctuate during the tourist experience, peaking during vacation [73]; negative emotions remain less intense and constant throughout vacations [71], except in specific contexts, such as in darker forms of dark tourism [74].