Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), has led to an unprecedented public health emergency worldwide. While common cold symptoms are observed in mild cases, COVID‐19 is accompanied by multiorgan failure in severe patients. Organ damage in COVID‐19 patients is partially associated with the indirect effects of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (e.g., systemic inflammation, hypoxic‐ischemic damage, coagulopathy), but early processes in COVID‐19 patients that trigger a chain of indirect effects are connected with the direct infection of cells by the virus. To understand the virus transmission routes and the reasons for the wide‐spectrum of complications and severe outcomes of COVID‐19, it is important to identify the cells targeted by SARS‐CoV‐2. This review summarizes the major steps of investigation and the most recent findings regarding SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism and the possible connection between the early stages of infection and multiorgan failure in COVID‐19. The SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic is the first epidemic in which data extracted from single‐cell RNA‐seq (scRNA‐seq) gene expression data sets have been widely used to predict cellular tropism. The analysis presented here indicates that the SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism predictions are accurate enough for estimating the potential susceptibility of different cells to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; however, it appears that not all susceptible cells may be infected in patients with COVID‐19.

Keywords: cell entry factors, cellular tropism, infection, multiorgan failure, SARS‐CoV‐2, scRNA‐seq

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID‐19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), primarily involves the respiratory tract and varies from mild respiratory disease similar to the common cold to interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome, which can result in death (B. Hu et al., 2021). In severe cases, COVID‐19 can be accompanied by damage to multiple organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and heart (N. Chen et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Lopes‐Pacheco et al., 2021; D. Wang, Hu, et al., 2020). Multiorgan failure in COVID‐19 patients seems to depend on indirect systemic consequences of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, such as hypoxemia due to severe pneumonia, dysregulated immune responses, blood vessel injury, coagulopathy, and tissue fibrosis. However, the primary effects of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, that is, transmission into the body and the early stages of disease, depend on the viral infection of cells.

Obtaining reliable and complete information about cellular tropism is time‐consuming; therefore, in the initial stage of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, advanced in silico methods were used to predict the cells susceptible to viral infection. The expression of proteins necessary for viral entry into cells was investigated in numerous studies that were published during the first few months of the pandemic. These analyses were based on data that were extracted from single‐cell RNA‐seq (scRNA‐seq) data sets of gene expression that were obtained from healthy organs. Such data made it possible to generate assumptions about the possible mechanisms of multiorgan failure in COVID‐19 patients and substantially sped up SARS‐CoV‐2 studies (Murgolo et al., 2021).

2. SARS‐COV‐2 ENTRY FACTORS

Coronaviruses are single‐stranded positive‐strand (+) RNA viruses named after the solar corona, which they resemble in electron micrographs (“Virology: Coronaviruses,” 1968). SARS‐CoV‐2 carries one of the largest RNA genomes (~30 kilobases) among all RNA virus families. The packaging of the RNA genome into the 80‐nm‐diameter viral lumen is provided by the nucleocapsid (N) protein. Mature SARS‐CoV‐2 virions are surrounded by a membrane, which contains three structural proteins: spike (S), envelope (E), and membrane (M) proteins. Similar to other coronaviruses, SARS‐CoV‐2 uses the S protein for viral entry into the target cell.

SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors have been intensively studied (Baggen et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021). However, at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020, only scarce, very preliminary data were available, and many assumptions were made by analogy with other coronaviruses, especially SARS‐CoV, the sequences of which shares 79% sequence identity with SARS‐CoV‐2 (R. Lu, Zhao, et al., 2020).

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) was originally identified in 2003 as the main receptor for SARS‐CoV (W. Li et al., 2003) and it was shown that novel coronavirus uses the same cell entry receptor (Hoffmann, Kleine‐Weber, Schroeder et al., 2020; Letko et al., 2020; P. Zhou, Yang, et al., 2020). The general lack of permissiveness to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in lung‐derived cell lines can be rescued by ectopic expression of ACE2 (Blanco‐Melo et al., 2020). Similarly, the expression of human ACE2 in mice led to the development of an animal system for the investigation of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Jiang et al., 2020).

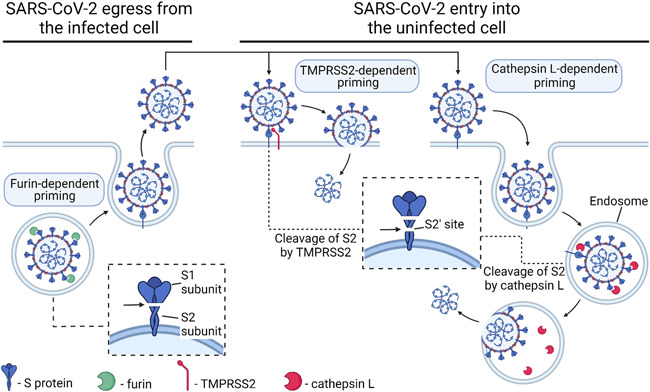

The S protein of some coronaviruses, that is, MERS‐CoV, is cleaved into S1 and S2 subunits during biosynthesis inside infected cells (Park et al., 2016). Similarly, the S protein of SARS‐CoV‐2 is cleaved by the host protease furin in virus‐producing cells (Hoffmann, Kleine‐Weber, Pöhlmann, 2020; Shang et al., 2020). Furin is localized within the trans‐Golgi network/endosomal system (Molloy et al., 1999; Thomas, 2002); thus, S protein cleavage occurs during viral particle egress from the cell (Figure 1). As a result, the S protein on the mature virion consists of two noncovalently associated subunits: the N‐terminal S1 subunit, which is responsible for ACE2 recognition, and the C‐terminal transmembrane S2 subunit, which is responsible for membrane fusion.

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into cells. The SARS‐CoV‐2 S protein binds to its receptor, ACE2, on the cell surface, but viral entry occurs only after specific digestion by priming proteases (furin, TMPRSS2, cathepsin L). Furin digests S protein into S1 and S2 subunits during viral egress from the infected cell in the trans‐Golgi network/endosomal system. TMPRSS2 or cathepsin L additionally digest the S2 subdomain at the S2′ cleavage site either at the cell surface or inside the endosome, but it seems that the TMPRSS2‐dependent pathway is the major pathway for SARS‐CoV‐2 entry. Omicron variant of SARS‐CoV‐2 enters cells in a TMPRSS2‐independent manner via the endosomal route. Created with BioRender.com. ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TMPRSS2, transmembrane protease, serine 2.

SARS‐CoV‐2 entry additionally depends on S protein priming by host cell transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) (Hoffmann, Kleine‐Weber, Schroeder et al., 2020) and lysosomal protease cathepsin L, encoded by the CTSL gene (Shang et al., 2020) (Figure 1). A second cleavage within the S2 subdomain (S2′ cleavage site) by TMPRSS2 and/or cathepsin L may further enhance infectivity, modifying the S protein conformation (Cai et al., 2020).

ACE2 expression was analyzed in all works in which SARS‐CoV‐2 cell tropism was investigated; the expression of priming proteases (furin, TMPRSS2, and/or cathepsins) was also analyzed in some papers. Cleavage with furin is essential for S protein‐mediated SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into human cells (Hoffmann, Kleine‐Weber, Pöhlmann, 2020; Johnson et al., 2021), but furin acts during viral egress from infected cells; therefore, theoretically, cells without furin expression can be infected by virus particles produced by furin‐expressing cells. As a result, furin is not the best choice for the analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors, but FURIN expression seems to be a possible indicator of productive infection. The coexpression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (Lukassen et al., 2020; Muus et al., 2021) and/or the coexpression of ACE2 and CTSL (Muus et al., 2021) should be considered reliable markers of cells that can potentially be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2. SARS‐CoV‐2 is more dependent on TMPRSS2 (Hoffmann, Kleine‐Weber & Schroeder et al., 2020; Ou et al., 2021), but if the target cell expresses insufficient TMPRSS2, ACE2‐bound virus is internalized via clathrin‐mediated endocytosis into the late endolysosome, where the S2′ site is cleaved by cathepsins (Koch et al., 2021). TMPRSS2 is expressed with a broader distribution than that of ACE2, suggesting that ACE2, rather than TMPRSS2, may be a limiting factor for viral entry in the initial stage of infection (Sungnak et al., 2020). It should be noted that the Omicron variant of SARS‐CoV‐2 enters cells in a TMPRSS2‐independent manner via the endosomal route (Meng et al., 2022; Peacock et al., 2022; Willett et al., 2022; H. Zhao et al., 2022), which is in good correlation with the reduced cell entry efficiency into TMPRSS2‐expressing cells for Omicron in comparison to Delta viruses (Meng et al., 2022; H. Zhao et al., 2022).

Studies of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry have focused on ACE2 and priming proteases, which are expressed at extremely low levels in, for example, respiratory epithelial cells. This raises the possibility that cofactors are required to facilitate SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into cells with low ACE2 expression. Indeed, several molecules have been suggested to serve as alternative receptors or coreceptors for SARS‐CoV‐2. For example, CD147 (basigin), a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed ubiquitously in epithelial and immune cells, was identified as a receptor involved in SARS‐CoV‐2 entry independently of ACE2 (K. Wang, Chen, et al., 2020); however, it was later shown that CD147 does not bind the S protein directly (Ragotte et al., 2021; Shilts et al., 2021). Additionally, tyrosine‐protein kinase receptor UFO (AXL) was identified as a candidate receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2 that promotes the infection of pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells (S. Wang, Qiu, et al., 2021). ACE2‐dependent entry can also be realized via C‐type lectin receptors, which recognize glycans on the virion surface (Amraei et al., 2021; Lempp et al., 2021; Thépaut et al., 2021). The S protein can also bind to sialylated glycans, especially glycolipids, to facilitate viral entry (Nguyen et al., 2021). Finally, heparan sulfate facilitates ACE2‐dependent SARS‐CoV‐2 entry (Clausen et al., 2020; Shiliaev et al., 2021; R. Wang, Simoneau, et al., 2021). Some indications of possible involvement as coreceptor molecules facilitating SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry were obtained for KIM1/TIM1 (Mori et al., 2022; C. Yang et al., 2021), neuropilin 1 (NRP1) (Cantuti‐Castelvetri et al., 2020; Daly et al., 2020), and nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA (MYH9) (J. Chen et al., 2021). It seems that the list of possible SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors will grow, and some of them might be useful for SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism prediction.

Thus, data regarding the expression of ACE2 or the coexpression of ACE2 with TMPRSS2 and/or CTSL can be regarded as the most reliable instrument for SARS‐CoV‐2 tropism prediction. sc/snRNA‐seq based prediction methods using additional (co)receptor molecules have not yet been developed.

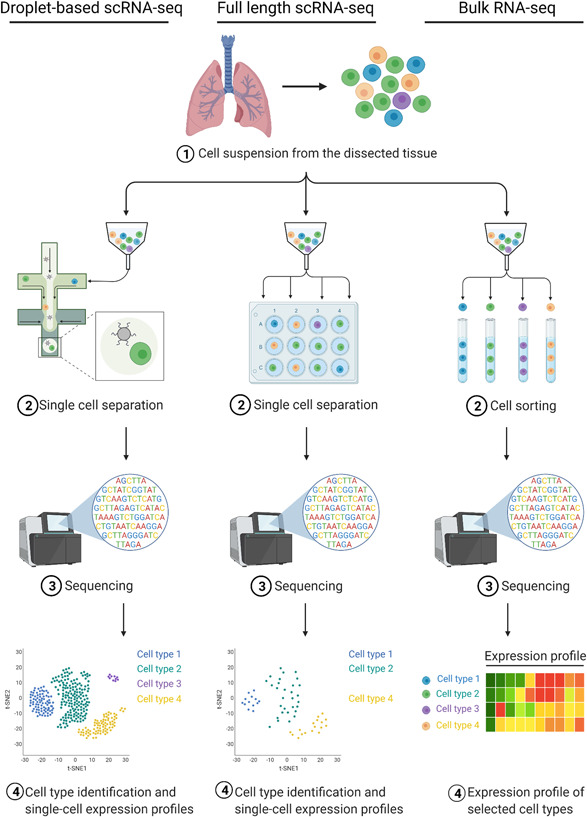

3. BULK RNA‐SEQ AND SCRNA‐SEQ METHODS

The high‐throughput analysis of gene expression by RNA‐seq revolutionized modern biology and medicine. Organ‐specific RNA‐seq data are available in several databases (EMBL‐EBI Expression Atlas, Human Protein Atlas, FANTOM5, and GTEx), but these data describe the expression of specimens that include a highly heterogeneous cell population. scRNA‐seq refers to a group of methods that enable the analysis of transcriptomes of individual cells. scRNA‐seq analysis allows us to estimate the size of the cell population that expresses the gene(s) of interest and estimate the expression level of these genes in these cell populations. scRNA‐seq approaches can be divided into two groups (Figure 2).

-

(i)

The first group of scRNA‐seq methods includes droplet‐based approaches (Zheng et al., 2017). These approaches are used to process thousands of cells per sample but with considerably low sequencing depth (~20,000 reads/cell). The high number of captured cells makes it possible to identify and characterize rare cell types (X. Wang, He, et al., 2021). However, the sensitivity of these methods is generally low, and transcripts with low or moderate expression can remain undetected (Ding et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the majority of publicly available data were obtained using this group of approaches, and below, we will preferentially discuss such data unless otherwise specified.

-

(ii)

The second group comprises relatively low‐throughput approaches that are plate‐based and are mainly used for full‐length transcriptome profiling in single cells (full‐length scRNA‐seq). These methods are usually applied for examining a few hundred cells but with a larger number of reads per cell (usually 350,000−500,000 reads/cell). This leads to more accurate identification of gene expression levels, as well as to a higher number of detected genes (Ding et al., 2020). However, the limited cell number makes capturing and profiling rare cell types highly unlikely.

Figure 2.

Major strategies for analyzing individual cell transcriptomes (single‐cell RNA‐seq [scRNA‐seq] approaches) that were used for the analysis of entry factors during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Droplet‐based (left column) and plate‐based (full‐length) RNA‐seq (central column) protocols enable the analysis of transcriptomes of individual cells. The bulk RNA‐seq protocol (right column) captures information about transcriptomes of cells selected by any mechanical methods, most often by fluorescence‐activated cell sorting. This approach does not provide information on gene expression in individual cells but allows the assessment of gene expression in cell types of interest. Thus, the usefulness of this method is intermediate between the scRNA‐seq methods and the conventional RNA‐seq of tissue samples. Created with BioRender.com. SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The standard (bulk) RNA‐seq protocol (bulk RNA‐seq) can be applied to profile transcriptomes of cell populations enriched for specific cell types (Figure 2). In this case, the cells of interest are physically selected and accumulated (e.g., by fluorescence‐activated cell sorting [FACS]) to ensure sufficient starting material for RNA purification and sequencing. However, this approach cannot be applied for estimating the expression level in individual cells or the proportion of cells expressing the gene of interest.

Protocols in which isolated nuclei are used for the analysis have enabled the investigation of gene expression in individual cells taken from biopsy or autopsy specimens (single nucleus RNA‐seq, snRNA‐seq) (Ding et al., 2020). In particular, snRNA‐seq has been successfully used to study the composition and processes at the single‐cell level in patients who died of COVID‐19 (Delorey et al., 2021; Melms et al., 2021; S. Wang, Yao, et al., 2021).

scRNA‐seq data from different tissues and organs assembled into single‐cell transcriptomics atlases were already available at the start of the pandemic and were immediately used to analyze the cellular factors involved in SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into cells (SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors) and to predict the cell types susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 and to hypothesize possible transmission routes (Supporting Information: Table S1).

4. DROPOUT EFFECT AND DETECTION OF CELLS SUSCEPTIBLE TO SARS‐COV‐2 INFECTION

The first investigations of SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism based on scRNA‐seq data sets cautioned against possible drawbacks of scRNA‐seq, as the technology itself suffers from a low signal‐to‐noise ratio and a high percentage of technical dropouts (Sungnak et al., 2020). Indeed, some scRNA‐seq analysis results were not in good agreement with the characteristics of the pathological processes typically seen in the lungs of COVID‐19 patients. For example, in the alveolar epithelium, ACE2 expression was found only in a small subset (1%−7%) of alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells (Hikmet et al., 2020; Lukassen et al., 2020; Ortiz et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Sungnak et al., 2020; Y. Zhao et al., 2020; Ziegler et al., 2020), although the severity of the disease suggests a more widespread distribution. The expression of ACE2 and other SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors might be underestimated due to the presence of dropout events, that is, a gene is detected in one cell but not in another cell, usually due to extremely low mRNA input and/or the stochastic nature of gene expression (Grün et al., 2014; Kharchenko et al., 2014; Mereu et al., 2020; Stegle et al., 2015).

The methods of full‐length scRNA‐seq allow obtaining a larger number of reads from one cell but at the cost of a smaller number of cells being read. In contrast, droplet‐based scRNA‐seq methods process a larger number of cells but with lower reads per cell. The comparison of data sets obtained by Montoro and coauthors for murine trachea using two different methods, droplet‐based and full‐length scRNA‐seq (23,000 and 396,000 reads/cell, respectively) (Montoro et al., 2018), demonstrated that the proportion of cells expressing Ace2 and the priming proteases was substantially higher in the full‐length scRNA‐seq data (Valyaeva et al., 2020). For example, the proportions of Ace2 + basal cells were 0.60% and 9.38% in the droplet‐based scRNA‐seq and full‐length scRNA‐seq data sets, respectively (Valyaeva et al., 2020). This indicates that the population of epithelial cells potentially sensitive to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection might be underestimated by droplet‐based scRNA‐seq, that is, by the method by which the majority of results were obtained.

It seems probable that the dropout effect can also influence the results of snRNA‐seq data obtained from autopsy specimens from individuals who died from COVID‐19 (such data sets can provide direct evidence of which cells can actually be infected). The profiling of viral RNA signals identified infected cells, however, excitingly, these viral RNA‐positive cells did not coexpress any of the actual or hypothesized viral entry factors (Delorey et al., 2021). The absence of a supposed correlation between viral RNA and viral entry factor expression is disappointing but could be explained by the high dropout rate, which is a notable feature of high‐throughput sc/snRNA‐seq methods.

5. EXPERIMENTAL DETECTION OF SARS‐COV‐2 CELLULAR TROPISM

The analysis of scRNA‐seq data led to predictions of cells that were susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2; however, the major aim of the current review was to describe real SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism. Therefore, when analyzing the published data, we focused on methods that allow us to identify infected cells and, at the same time, to accurately establish the nature of these cells. These conditions are met by analysis of autopsies using modern analytical methods—immunochemical detection of viral proteins, detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA by in situ hybridization methods, and snRNA‐seq of postmortem material (Jonigk et al., 2022). Electron microscopy is widely used to detect viral particles; however, some cellular organelles can be misinterpreted as coronavirus particles, especially in autopsy specimens; as a result, some observations have been criticized (Dittmayer et al., 2020; Goldsmith et al., 2020; Hopfer et al., 2021; Miller & Brealey, 2020). We included electron microscopy studies for only some of the most accurate cases.

Additionally, we took into account investigations in which cultured cells or tissue fragments were infected in vitro, especially if there was insufficient data on the infection of cells in the human body. Of special importance are data obtained using embryonic stem/induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived 3D models, such as organoids. For example, brain organoids were successfully used for the detection of the cellular tropism of Zika virus during the 2016 epidemic (Cugola et al., 2016; Dang et al., 2016; Qian et al., 2016), and were also widely used during SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic (Luo et al., 2021). We did not take into account the results of RT‐PCR or bulk RNA‐seq that were obtained through the analysis of tissue specimens because the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA detected by these methods could be a consequence of either infection of stromal cells or the presence of infected blood cells (Solomon et al., 2020). Hence, these approaches lead to the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 organ or tissue tropism, but, in most cases, cannot be used for the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism. We also analyzed data obtained using laboratory animals successible to SARS‐CoV‐2 (Muñoz‐Fontela et al., 2020). These data are extremely useful for studying the SARS‐CoV‐2 biology and intervention development, but cellular tropism in animals may differ from that in humans, and such data should be used and interpreted with caution.

6. SARS‐COV‐2 INFECTION IN THE RESPIRATORY TRACT

Respiratory failure is the leading cause of death in patients with severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection; therefore, the expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors has been often investigated and described (Hikmet et al., 2020; Lukassen et al., 2020; Muus et al., 2021; Ortiz et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Sungnak et al., 2020; Y. Zhao et al., 2020; Ziegler et al., 2020). To understand the mechanism of viral entry into the human body and the transmission of the virus between people, it was highly important to understand whether the virus could enter cells of the upper respiratory tract. It was established that nasal epithelial cells were more susceptible to viral infection than epithelial cells in the lower airway or alveoli because they showed the highest expression of viral entry factors among all investigated cells in the respiratory tract (Ortiz et al., 2020; Sungnak et al., 2020).

These predictions were corroborated by high‐sensitivity RNA in situ mapping (Hou et al., 2020). By detecting subgenomic SARS‐CoV‐2 transcripts, which indicate active SARS‐CoV‐2 replication, it was shown that infection spreads from the airway to the lungs over time (Bhatnagar et al., 2021). Histological studies of human donor tissues demonstrated that ACE2 localizes predominantly to respiratory ciliated cells and that SARS‐CoV‐2 preferentially infects ciliated cells in the respiratory epithelium (Ahn et al., 2021; Hou et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2021; I. T. Lee, Nakayama, et al., 2020). ACE2 localizes within the motile cilia of airway epithelial cells, which likely represents the initial or early subcellular site of SARS‐CoV‐2 viral entry during host respiratory transmission (I. T. Lee, Nakayama, et al., 2020).

Lung tissue damage is one of the most striking features of COVID‐19, but as noted by many authors, the expression of entry factors in lung tissue is extremely low. The pulmonary alveolar epithelium is composed of two types of differentiated epithelial cells: alveolar type 1 (AT1) cells, which mediate gas exchange, and AT2 cells, which secrete surfactant. Only a small fraction of AT2 cells (1%−7%) express SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors, as demonstrated by scRNA‐seq (Lukassen et al., 2020; Ortiz et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020; Sungnak et al., 2020) and immunohistochemistry analysis (Ortiz et al., 2020). However, it seems that this fraction might be substantially underestimated due to the dropout effect, as discussed in detail above (Valyaeva et al., 2020). Nevertheless, even accounting for the dropout effect, both the proportion of ACE2 + cells and the level of ACE2 expression are substantially lower than those in, for example, the nasal cavity. However, the highest viral loads were detected in patients' lungs (Deinhardt‐Emmer et al., 2021; Schurink et al., 2020), but viral presence became sporadic with an increased disease course (Schurink et al., 2020). It seems probable that pathological (El Jamal et al., 2021; Müller et al., 2021; Schaefer et al., 2020) or snRNA‐seq (Delorey et al., 2021; Melms et al., 2021) observations of an absent or low viral load in lung specimens are specifically related to the later stages of the disease. It was suggested that SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of epithelial cells and direct viral tissue damage are transient phenomena that are generally not sustained throughout disease progression (El Jamal et al., 2021; Schaefer et al., 2020).

AT2 cells express SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors and play an important role in lung function and the renewal of the alveolar epithelium under normal conditions. However, most of the alveolar surface (~95%) is lined with AT1 cells. The death of AT1 cells has been associated with the indirect effects of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, but some evidence suggests that AT1 cells can become infected, similar to AT2 cells. For example, SARS‐CoV‐2 can infect both AT1 and AT2 cells ex vivo (Chu, Chan, Wang et al., 2020) and in infected macaques (Rockx et al., 2020). Both the AT1 and AT2 cells were also infected with a SARS‐CoV‐2 pseudovirus in the human alveolar epithelium model in vitro (J.‐W. Yang et al., 2022). SARS‐CoV‐2 was also detected in both AT1 and AT2 cells by immunohistochemical detection of viral proteins inside infected cells in human autopsy lungs (Schurink et al., 2020). Contradictory data have been obtained when detecting SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in autopsy lungs from fatal COVID‐19 cases. Some papers report that SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA or proteins were found only in AT2 cells (Acheampong et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Ortiz et al., 2020), others state that SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA is most frequently detected in AT1 cells (Schuler et al., 2021) or in both AT2 cells and AT1 cells (Hou et al., 2020).

There are two explanations for the lack of ACE2 expression in AT1 cells. First, if ACE2 expression is low, it might not be detected due to the dropout effect. Indeed, in the most complete single‐cell meta‐analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry genes, both AT1 and AT2 cells were found to coexpress ACE2 and CTSL (Muus et al., 2021). The second explanation is that there might be as‐yet unidentified pathways of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into AT1 cells. Such an alternative mechanism of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry was described for H522 lung adenocarcinoma cells. Infection of these ACE2‐negative cells requires surface heparan sulfates and seems to occur via clathrin‐mediated endocytosis (Puray‐Chavez et al., 2021). In any case, predictions and experimental observations indicate that AT1 cell susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is plausible. However, AT2 cells function as alveolar stem cells and can undergo transition to AT1 cells (Nabhan et al., 2018; Zacharias et al., 2018); this transient cell state might be mistaken for differentiated AT1 cells (Hou et al., 2020). It seems that only a more rigorous analysis of postmortem specimens using cutting‐edge technologies could definitively determine the tropism in the epithelium of the lung.

7. IMPAIRMENT OF RESPIRATORY EPITHELIUM REGENERATION IN COVID‐19

The airway and alveolar epithelia are characterized by relatively slow renewal but can be rapidly reconstituted by multipotent stem cells after episodes of infection, inflammation or injury, which are commonly observed in respiratory diseases (Basil et al., 2020). It seems probable that infection of stem cells can lead to disturbances in the processes of regeneration of the epithelium during COVID‐19. An analysis of published scRNA‐seq data sets from mouse respiratory epithelium demonstrated that cells of different lung epithelial stem cell types express SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors, including Ace2, and thus can potentially be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2 (Valyaeva et al., 2020). The analysis of mouse cells resulted from a lack of data obtained from human tissues.

A subpopulation of AT2 cells serves as alveolar stem cells that can differentiate into either AT1 or AT2 cells (Nabhan et al., 2018; Zacharias et al., 2018). Lung injury can induce alveolar regeneration via AT2 cell‐derived transient alveolar epithelial progenitors (Choi et al., 2020; Kobayashi et al., 2020; Strunz et al., 2020). AT2 cell hyperplasia was documented in cases of early‐phase COVID‐19 pneumonia in which samples were collected during surgical procedures or lung biopsies (Doglioni et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2020; Z. Zeng, Xu, et al., 2020). However, it seems that this hyperplasia did not lead to the effective regeneration of damaged epithelium. Single‐cell atlases of autopsy lung samples have demonstrated that AT2 fails to undergo full transition to AT1 cells in COVID‐19 lungs but is arrested in an intermediate progenitor cell state (Delorey et al., 2021; Melms et al., 2021; S. Wang, Yao, et al., 2021). This dysregulated epithelial cell differentiation can lead to impaired regeneration of the alveolar epithelium.

8. SARS‐COV‐2 ENTRY FACTOR EXPRESSION IN DIFFERENT ORGANS AND COMPLICATIONS OF SARS‐COV‐2 INFECTION

Although COVID‐19 is primarily a respiratory disease, ACE2 is widely expressed in various tissues and organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, heart muscle, and other organs, suggesting the potential capacity of SARS‐CoV‐2 to develop systemic infections in patients. In the early stage of the pandemic, the identification of tissues that can be infected was important for understanding how the virus enters the body and for planning epidemiological restrictions and developing interventions. Information about papers published between February and April 2020 (in the majority of cases, as preprints) is presented in Supporting Information: Table S1.

8.1. Ocular surface

Some respiratory viruses are known to possess ocular tropism and are capable of inducing ocular complications in infected patients (Belser et al., 2013). In a report published in the Lancet on February 6, 2020, a case of COVID‐19 was described in which eye redness preceded pneumonia. Because the patient wore an N95 mask but did not protect eyes, it was speculated that ocular surfaces might be a potential portal through which SARS‐CoV‐2 can infect the body (C. Lu, Liu, et al., 2020). The suggestion that the ocular surface can be a potential route of SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission led to the WHO recommendation that frontline medical workers wear ocular protective equipment (Bacherini et al., 2020).

Single‐cell analysis indicated that the cells of the outer epithelium of the eye coexpress ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and, potentially, could be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2 (Collin et al., 2021; Sungnak et al., 2020). ACE2 was detected by immunohistochemistry in the cornea and conjunctiva of the eye (Hikmet et al., 2020). Conjunctivitis is common in COVID‐19, and SARS‐CoV‐2 has been detected in tear samples (Colavita et al., 2020; Mastropasqua et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2020).

The presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 proteins in the ocular tissues (primarily in the epithelial layer of the cornea) of COVID‐19 patients was reported, indicating possible infection of the surface epithelial cells of eyes (Eriksen et al., 2021; Sawant et al., 2021; S. Singh et al., 2022). Additionally, SARS‐CoV‐2 was able to infect human cornea cells ex vivo (Maurin et al., 2022). Productive viral replication in postmortem samples and eye organoid cultures was reported, and, importantly, limbal cells were found to be more permissive than corneal cells to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Eriksen et al., 2021). Consistent with this, Sasamoto et al. (2022) showed that limbal stem cells express high levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2. The expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors on corneal and limbal cells is likely to be modulated in an age‐dependent manner, in agreement with the increased susceptibility to COVID‐19 in the elderly (Tisi et al., 2022). Together, these data indicate that eye cells can be directly infected by SARS‐CoV‐2 and implicate the limbus as a portal for viral entry.

Because the eye is connected with the nasal cavity, one can assume that the nasolacrimal duct might represent a possible transmission route of SARS‐CoV‐2 to the upper respiratory tract. Ocular inoculation of rhesus macaques with SARS‐CoV‐2 resulted in mild interstitial pneumonia, indicating that infection via the conjunctival route is possible in nonhuman primates (Deng et al., 2020). Ocular inoculation also resulted in lung infection in golden hamsters (Hoagland et al., 2021). There is no direct evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 transmission via the eye surface in humans, but the proportion of patients with COVID‐19 who wear glasses for extended daily periods (>8 h/day) is smaller than that in the general population (W. Zeng, Wang, et al., 2020).

Thus, as the ocular surface is an area susceptible to contamination, the possible transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 via the eye surface is still controversial. Further studies are needed to evaluate the cellular tropism of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the eyes and to develop appropriate precautions for high‐risk groups and for the general public, especially with the spread of new variants of the virus with increased infectivity.

8.2. Heart

Acute cardiac injury has been reported as a common complication associated with severe COVID‐19 (T. Guo, Fan, et al., 2020; J.‐W. Li et al., 2020; Lindner et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020). Several scRNA‐seq studies of healthy and compromised adult human heart revealed that ACE2 expression is highest in pericytes, followed by fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes (J. Guo, Wei, et al., 2020; Litviňuková et al., 2020; Sungnak et al., 2020). Notably, a higher ACE2‐positive rate was observed in cardiomyocytes of failed hearts than in those of normal hearts (J. Guo, Wei, et al., 2020; Vukusic et al., 2022). Almost no coexpression of the ACE2 and TMPRSS2 genes was detected in cardiac cells (Litviňuková et al., 2020; M. Singh et al., 2020; Sungnak et al., 2020). Instead of the TMPRSS2‐dependent viral entry mechanism, SARS‐CoV‐2 might use other viral entry factors, such as cathepsin L, that are relatively highly expressed in cardiomyocytes (Litviňuková et al., 2020; M. Singh et al., 2020).

A comparison of hearts from COVID‐19 patients and healthy individuals revealed changes in cell composition, including a significant loss of cardiomyocytes and pericytes and a prominent increase in the proportion of vascular endothelial cells; however, no viral RNA was detected in any of these cell types in COVID‐19 heart tissue (Delorey et al., 2021). It was reported that heart muscle in COVID‐19 patients contained infected nonmuscle (interstitial) cells within the cardiac tissue (Bräuninger et al., 2022; Lindner et al., 2020). However, in another published report, the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 antigen was found in cardiomyocytes from a COVID‐19 patient autopsy specimen, suggesting the possibility of direct myocardial injury by the virus (Nakamura et al., 2021).

The ability of SARS‐CoV‐2 to productively infect cardiomyocytes was shown using human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)‐derived heart cells (Y. Li et al., 2021; Marchiano et al., 2021; Navaratnarajah et al., 2021; Perez‐Bermejo et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2020; Siddiq et al., 2022). SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of hiPSC‐derived cardiomyocytes led to myofibrillar fragmentation and nuclear disruption, possibly through the dysregulation of genes associated with the linker of the nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex (Perez‐Bermejo et al., 2021). Similar alterations were identified in postmortem cardiac tissues from patients with COVID‐19 regardless of diagnosed myocarditis; however, no signal of the viral nucleocapsid protein was detected in any autopsy sample (Perez‐Bermejo et al., 2021).

Thus, direct evidence of cardiomyocyte infection is not conclusive, although cardiomyocytes seem to be susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2.

8.3. Gastrointestinal tract

COVID‐19 is primarily a respiratory disease, but approximately half of all patients experience gastrointestinal disorders (L. Yang & Tu, 2020). Some patients do not have any imaging features of COVID‐19 pneumonia but only show gastrointestinal symptoms (Lin et al., 2020). Using scRNA‐seq data from different gastrointestinal segments, it was shown that different cells of the gastrointestinal tract expressed SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors. Small intestinal enterocytes show one of the highest ACE2 expression levels (Venkatakrishnan et al., 2020). In general, the proportion of cells with ACE2 expression was found to be more than 10 times higher in the lower gastrointestinal tract (ileum, colon, rectum) than in the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, duodenum), and coexpression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 is more prevalent in the lower gastrointestinal tract (J. J. Lee, Kopetz, et al., 2020).

Direct evidence of gastrointestinal tract infection is sparse. The SARS‐CoV‐2 N protein has been detected in gastrointestinal biopsies (Liu et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2020), and by analyzing intracellular viral subgenomic messenger RNA, it was shown that active SARS‐CoV‐2 replication occurs in the gastrointestinal tract (F. Hu et al., 2020). Approximately half of all COVID‐19 patients have detectable SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in fecal specimens, also suggesting that the digestive tract might be a site of viral replication and activity (Xiao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

Some cultured enterocytes can be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2. For example, cultured colorectal adenocarcinoma cells Caco‐2 can be infected in vitro and were used for investigation of SARS‐CoV‐2 replication (Bojkova et al., 2020; Chu, Chan, Yuen et al., 2020; S. Lee, Yoon, et al., 2020; Mautner et al., 2022). Several studies using human small intestinal organoids have shown that SARS‐CoV‐2 can infect enterocytes (Lamers et al., 2020; J. Zhou, Li, et al., 2020). Moreover, enterocytes in these organoids produce infectious viral particles, indicating that the intestinal epithelium can support SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Lamers et al., 2020). Additionally, SARS‐CoV‐2 can target the human intestinal epithelium ex vivo and induce cytopathic effects in infected epithelial cells (Chu et al., 2021).

8.4. Pancreas

Preexisting diabetes increases the risk of severe disease and mortality, and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection might lead to new‐onset diabetes or aggravation of preexisting metabolic disorders; these outcomes might be a result of virus‐associated β‐cell destruction (Scherer et al., 2022; Steenblock, Schwarz, et al., 2021). Contradictory results have been reported concerning the expression of ACE2 and other SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors in the pancreas. An analysis of scRNA‐seq data sets demonstrated the robust expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors in pancreatic ductal and acinar cells (J. J. Lee, Kopetz, et al., 2020) and in pancreatic ductal epithelium and microvasculature (Coate et al., 2020), while ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in endocrine cells was minimal or undetectable. The bulk RNA‐seq of α‐cells and β‐cells enriched by FACS, however, demonstrated relatively low but detectable expression of the ACE2 and TMPRSS2 genes (Coate et al., 2020). The expression of ACE2 and other entry factors was clearly demonstrated in β‐cells at the protein level (Fignani et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2021; Steenblock, Richter, et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). The susceptibility of these cell types to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection has also been supported by experimental data. After the infection of isolated human primary islets with SARS‐CoV‐2, both α‐cells and β‐cells stained positive for the SARS‐CoV‐2 S protein, demonstrating that, at least in vitro, pancreatic cells can be infected (L. Yang, Han, Nilsson‐Payant, et al., 2020). Infection of β‐cells in isolated human primary islets was also demonstrated in other papers (Müller et al., 2021; Steenblock, Richter, et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Single‐cell analyses of in vitro SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected human pancreatic islets demonstrated that productive infection is strictly dependent on the SARS‐CoV‐2 entry receptor ACE2 and targets practically all pancreatic cell types (van der Heide et al., 2022). At last, SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of human pancreatic β‐cells was confirmed in patients who succumbed to COVID‐19 (Müller et al., 2021; Steenblock, Richter, et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). The replication of SARS‐CoV‐2 in β‐cells can lead to suppressed insulin production (Müller et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021).

8.5. Kidney

In SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, the kidney is one of the most commonly affected extrapulmonary organs, and acute kidney injury frequently occurs in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 (Hassler et al., 2021; Hirsch et al., 2020; Legrand et al., 2021). scRNA‐seq data indicate that ACE2 is highly expressed in the kidney tubule, collecting duct principal cells, and glomerular parietal epithelial cells, but it has not been observed in immune cells (J. Song et al., 2020). Hence, kidney cells are potential targets of COVID‐19 and infection.

Autopsy reports have provided evidence that the virus can directly infect the kidney cells of COVID‐19 patients (Bradley et al., 2020; Diao et al., 2021; Jansen et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021; Menter et al., 2020; Müller et al., 2021; Odilov et al., 2021; Puelles et al., 2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 particles were isolated from an autopsied kidney and subsequently shown to infect Vero cells, thus confirming the presence of infective virus in the kidney, even under postmortem conditions (Braun et al., 2020). In another study, SARS‐CoV‐2 was unable to infect human kidney ex vivo (Chu et al., 2021).

8.6. Olfactory epithelium

A sudden loss of olfactory function in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals (anosmia) was reported worldwide at the onset of the pandemic as one of the more common symptoms of COVID‐19. scRNA‐seq revealed that ACE2 is expressed in support cells, stem cells, and perivascular cells, but not in neurons, suggesting that SARS‐CoV‐2 infection of nonneuronal cell types leads to anosmia and related disturbances in odor perception in COVID‐19 patients (Brann et al., 2020). ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are coexpressed in supporting sustentacular cells (Fodoulian et al., 2020). Infection of the olfactory epithelium has been studied in humans using microscopic techniques. One study found that multiple cell types of the olfactory epithelium could be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2, including olfactory sensory neurons, sustentacular (supporting) cells, and immune cells (de Melo et al., 2021). It was shown that sustentacular (nonneuronal) cells are the main target cell type in the olfactory epithelium; at the same time, the infection of olfactory sensory neurons was not detected (Khan et al., 2021). Additionally, transmission electron microscopy results revealed the presence of viral particles in the cytoplasm of a cell of the olfactory bulb (Morbini et al., 2020).

The SARS‐CoV‐2 S protein was also found in neural/neuronal cells of the olfactory mucosa and even in distinct regions of the central nervous system in patients with COVID‐19 (Meinhardt et al., 2021). It appears that the olfactory complex may be a major route of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into the central nervous system (Meinhardt et al., 2021; Morbini et al., 2020), as was previously shown in animal studies with the human coronavirus OC43 (Dubé et al., 2018).

It should be also noted that the anosmia is common in patients infected with the SARS‐CoV‐2 original WA1 and later Delta strains. Omicron rarely causes the loss of the sense of smell, probably, due to a transition in SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism from olfactory to respiratory epithelium as the SARS‐CoV‐2 evolved (M. Chen et al., 2022).

8.7. Brain

Neurological manifestations such as headache, mental confusion, psychiatric disorders, strokes, and encephalitis are among the most striking symptoms of COVID‐19 (Maiese et al., 2021). The majority of early studies in which different organs were analyzed did not identify the brain as a possible target of SARS‐CoV‐2 (Supporting Information: Table S1). However, a diligent investigation of ACE2 expression in the brain that analyzed data from publicly available brain transcriptome databases showed that ACE2 was relatively highly expressed in some brain locations, such as the choroid plexus, paraventricular nuclei of the thalamus, as well as in many neurons (both excitatory and inhibitory neurons) and in some nonneuronal cells (mainly astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and endothelial cells) in the human middle temporal gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex (R. Chen et al., 2021). These results indicated that brain infection by SARS‐CoV‐2 is possible exclusively in some restricted anatomical locations and in a limited number of cell types.

The data on SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in the human brain are controversial (Veleri, 2022; Verkhratsky et al., 2020). A snRNA‐seq study found no detectable SARS‐CoV‐2 in the brain at the time of death, although significant and persistent neuroinflammation in patients with acute COVID‐19 was detected (Fullard et al., 2021). In contrast, other study detected SARS‐CoV‐2 in the brains of 53% of patients who died of COVID‐19, and SARS‐CoV‐2 viral proteins were found in cranial nerves originating from the lower brainstem and in isolated cells of the brainstem (Matschke et al., 2020). The presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 in the central nervous system has not been associated with the presence or severity of neuropathological changes, suggesting that central nervous system damage is not directly caused by neural cell infection (Cosentino et al., 2021; Matschke et al., 2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 neuroinvasion was also demonstrated in vitro using human brain organoids, in vivo using mice overexpressing human ACE2, and in patients who died of COVID‐19 (E. Song et al., 2021). In the case of autopsies, SARS‐CoV‐2 was detected in cortical neurons, and, remarkably, all the regions of positive viral staining showed no lymphocyte or leukocyte infiltration (E. Song et al., 2021). The authors of this study noted that autopsy samples from only a small number of patients were examined, and future studies are needed.

The absence or low levels of infection in the central nervous system might be due to SARS‐CoV‐2 being unable to enter the brain or to penetrate the blood‐brain barrier. The first proposed neuroinvasive pathway of SARS‐CoV‐2 was anterograde axonal transport via olfactory neurons in which the virus penetrated defined neuroanatomical areas, including the primary respiratory and cardiovascular control center in the medulla oblongata (Meinhardt et al., 2021).

The human brain is one of the most difficult objects for studying viral tropism because the brain consists of anatomically distinct regions, and different locations can have different susceptibility to infection. Embryonic stem/induced pluripotent stem cell‐derived 3D models, such as organoids and assembloids, provide an opportunity to analyze viral infection of human cells (Marton & Pașca, 2020). Using brain organoids, it was shown that SARS‐CoV‐2 infected choroid plexus epithelial cells but hardly infected neurons or glial cells (Jacob et al., 2020; Pellegrini et al., 2020). Other studies have indicated that SARS‐CoV‐2 can infect neurons of brain organoids, and the preferred tropism to mature neurons was found (Ramani et al., 2020; E. Song et al., 2021; Tiwari et al., 2021).

Thus, SARS‐CoV‐2 can infect neural cells, but, at least, substantial part of the neural damage is more likely due to systemic inflammation, hypoxic‐ischemic damage, and coagulopathy, leading to harmful indirect effects on the central nervous system (Cosentino et al., 2021; Veleri, 2022; Verkhratsky et al., 2020).

9. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE STUDIES

The high morbidity and mortality of COVID‐19 patients are caused by direct infection of the affected organs and indirect effects mediated by systemic inflammation, hypoxic‐ischemic damage, and coagulopathy. To ascertain the role of direct infection on disease progression and on the induction of indirect effects, it is necessary to gain a better understanding of the tropism of the virus, that is, which tissues and cell types can be infected by SARS‐CoV‐2. The analysis of molecules involved in SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into cells is the simplest method of predicting cellular tropism. The key molecules were identified in the first months after the onset of the pandemic. Work carried out during the first 2 years after the appearance of SARS‐CoV‐2 identified a large number of molecules involved in the processes of virus entry into the cell. However, methods for predicting SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism on the basis of analyzing different entry factors have not yet been fully developed, although attempts have been made (M. Singh et al., 2020).

Analyzing the expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors has not led to an exact determination of which cells can be infected and which cannot, but it has allowed us to make a risk map indicating the probable vulnerability of different organs to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The tissue reservoirs for SARS‐CoV‐2 replication in organs remain to be fully elucidated, partly due to difficulties in accessing biopsy samples from patients during the short window of active virus infection.

The cellular entry mechanism and cellular tropism might differ among SARS‐CoV‐2 variants (Stolp et al., 2022) resulting in a different clinical presentation and organ involvement. Therefore, an analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry factors using sc/snRNA‐seq data sets might be useful for predicting the pathological properties of novel viruses. The approach suffers from low transcript capture efficacy and cannot be successfully used to profile genes with low expression levels, which has led to underestimating the percentage of cells susceptible to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The further development of RNA‐seq technologies and the refinement of cell atlases, such as the Human Cell Atlas (Rozenblatt‐Rosen et al., 2017), as well as studies elucidating the exact mechanisms of viral entry into different cell types and the role of different receptors and coreceptors may be useful for the development of interventions. The study of proteomes and interactomes can also provide new data for more accurate predictions, than predictions based on the analysis of gene expression. Recently, an approach to identify the cellular‐level tropism of SARS‐CoV‐2 using human proteomics, virus−host interactions, and enrichment analysis was described (Ortega‐Bernal et al., 2022). Additionally, the development of atlases integrating protein localization data, such as the Human Protein Atlas (Uhlén et al., 2015), could lead to much more accurate predictions.

Elucidating the cell populations susceptible to virus infection is important for understanding the virus transmission routes and disease pathogenesis, as well as for developing interventions. Novel proteomic and histological methods to investigate and predict viral tropism would help us to be better prepared for any future outbreaks.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in the literature search, generation of figures, and writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. E. Khrameeva, D. M. Potashnikova, T. V. Lipina, and E. S. Vassetzky for stimulating discussion and criticism. We apologize that we could not acknowledge all relevant work due to space constraints. This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant 21‐74‐20134).

Valyaeva, A. A. , Zharikova, A. A. , & Sheval, E. V. (2023). SARS‐CoV‐2 cellular tropism and direct multiorgan failure in COVID‐19 patients: Bioinformatic predictions, experimental observations, and open questions. Cell Biology International, 47, 308–326. 10.1002/cbin.11928

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Acheampong, K. K. , Schaff, D. L. , Emert, B. L. , Lake, J. , Reffsin, S. , Shea, E. K. , Comar, C. E. , Litzky, L. A. , Khurram, N. A. , Linn, R. L. , Feldman, M. , Weiss, S. R. , Montone, K. T. , Cherry, S. , & Shaffer, S. M. (2022). Subcellular detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in human tissue reveals distinct localization in alveolar type 2 pneumocytes and alveolar macrophages. mBio, 13, e0375121. 10.1128/mbio.03751-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J. H. , Kim, J. , Hong, S. P. , Choi, S. Y. , Yang, M. J. , Ju, Y. S. , Kim, Y. T. , Kim, H. M. , Rahman, M. T. , Chung, M. K. , Hong, S. D. , Bae, H. , Lee, C. S. , & Koh, G. Y. (2021). Nasal ciliated cells are primary targets for SARS‐CoV‐2 replication in the early stage of COVID‐19. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 131(13), e148517. 10.1172/JCI148517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amraei, R. , Yin, W. , Napoleon, M. A. , Suder, E. L. , Berrigan, J. , Zhao, Q. , Olejnik, J. , Chandler, K. B. , Xia, C. , Feldman, J. , Hauser, B. M. , Caradonna, T. M. , Schmidt, A. G. , Gummuluru, S. , Mühlberger, E. , Chitalia, V. , Costello, C. E. , & Rahimi, N. (2021). CD209L/L‐SIGN and CD209/DC‐SIGN act as receptors for SARS‐CoV‐2. ACS Central Science, 7(7), 1156–1165. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacherini, D. , Biagini, I. , Lenzetti, C. , Virgili, G. , Rizzo, S. , & Giansanti, F. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic from an ophthalmologist's perspective. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 26(6), 529–531. 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggen, J. , Vanstreels, E. , Jansen, S. , & Daelemans, D. (2021). Cellular host factors for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Nature Microbiology, 6(10), 1219–1232. 10.1038/s41564-021-00958-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basil, M. C. , Katzen, J. , Engler, A. E. , Guo, M. , Herriges, M. J. , Kathiriya, J. J. , Windmueller, R. , Ysasi, A. B. , Zacharias, W. J. , Chapman, H. A. , Kotton, D. N. , Rock, J. R. , Snoeck, H. W. , Vunjak‐Novakovic, G. , Whitsett, J. A. , & Morrisey, E. E. (2020). The cellular and physiological basis for lung repair and regeneration: Past, present, and future. Cell Stem Cell, 26(4), 482–502. 10.1016/j.stem.2020.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser, J. A. , Rota, P. A. , & Tumpey, T. M. (2013). Ocular tropism of respiratory viruses. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 77(1), 144–156. 10.1128/MMBR.00058-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, J. , Gary, J. , Reagan‐Steiner, S. , Estetter, L. B. , Tong, S. , Tao, Y. , Denison, A. M. , Lee, E. , DeLeon‐Carnes, M. , Li, Y. , Uehara, A. , Paden, C. R. , Leitgeb, B. , Uyeki, T. M. , Martines, R. B. , Ritter, J. M. , Paddock, C. D. , Shieh, W. J. , & Zaki, S. R. (2021). Evidence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 replication and tropism in the lungs, airways, and vascular endothelium of patients with fatal coronavirus disease 2019: An autopsy case series. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 223(5), 752–764. 10.1093/infdis/jiab039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco‐Melo, D. , Nilsson‐Payant, B. E. , Liu, W.‐C. , Uhl, S. , Hoagland, D. , Møller, R. , Jordan, T. X. , Oishi, K. , Panis, M. , Sachs, D. , Wang, T. T. , Schwartz, R. E. , Lim, J. K. , Albrecht, R. A. , & tenOever, B. R. (2020). Imbalanced host response to SARS‐CoV‐2 drives development of COVID‐19. Cell, 181(5), 1036–1045. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojkova, D. , Klann, K. , Koch, B. , Widera, M. , Krause, D. , Ciesek, S. , Cinatl, J. , & Münch, C. (2020). Proteomics of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature, 583(7816), 469–472. 10.1038/s41586-020-2332-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, B. T. , Maioli, H. , Johnston, R. , Chaudhry, I. , Fink, S. L. , Xu, H. , Najafian, B. , Deutsch, G. , Lacy, J. M. , Williams, T. , Yarid, N. , & Marshall, D. A. (2020). Histopathology and ultrastructural findings of fatal COVID‐19 infections in Washington state: A case series. The Lancet, 396(10247), 320–332. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31305-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann, D. H. , Tsukahara, T. , Weinreb, C. , Lipovsek, M. , Van den Berge, K. , Gong, B. , Chance, R. , Macaulay, I. C. , Chou, H. J. , Fletcher, R. B. , Das, D. , Street, K. , de Bezieux, H. R. , Choi, Y. G. , Risso, D. , Dudoit, S. , Purdom, E. , Mill, J. , Hachem, R. A. , … Datta, S. R. (2020). Non‐neuronal expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID‐19‐associated anosmia. Science Advances, 6(31), eabc5801. 10.1126/sciadv.abc5801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, F. , Lütgehetmann, M. , Pfefferle, S. , Wong, M. N. , Carsten, A. , Lindenmeyer, M. T. , Nörz, D. , Heinrich, F. , Meißner, K. , Wichmann, D. , Kluge, S. , Gross, O. , Pueschel, K. , Schröder, A. S. , Edler, C. , Aepfelbacher, M. , Puelles, V. G. , & Huber, T. B. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 renal tropism associates with acute kidney injury. The Lancet, 396(10251), 597–598. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31759-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bräuninger, H. , Stoffers, B. , Fitzek, A. D. E. , Meißner, K. , Aleshcheva, G. , Schweizer, M. , Weimann, J. , Rotter, B. , Warnke, S. , Edler, C. , Braun, F. , Roedl, K. , Scherschel, K. , Escher, F. , Kluge, S. , Huber, T. B. , Ondruschka, B. , Schultheiss, H. P. , Kirchhof, P. , … Lindner, D. (2022). Cardiac SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is associated with pro‐inflammatory transcriptomic alterations within the heart. Cardiovascular Research, 118(2), 542–555. 10.1093/cvr/cvab322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y. , Zhang, J. , Xiao, T. , Peng, H. , Sterling, S. M. , Walsh, R. M., Jr. , Rawson, S. , Rits‐Volloch, S. , & Chen, B. (2020). Distinct conformational states of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein. Science, 369(6511), 1586–1592. 10.1126/science.abd4251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantuti‐Castelvetri, L. , Ojha, R. , Pedro, L. D. , Djannatian, M. , Franz, J. , Kuivanen, S. , van der Meer, F. , Kallio, K. , Kaya, T. , Anastasina, M. , Smura, T. , Levanov, L. , Szirovicza, L. , Tobi, A. , Kallio‐Kokko, H. , Österlund, P. , Joensuu, M. , Meunier, F. A. , Butcher, S. J. , … Simons, M. (2020). Neuropilin‐1 facilitates SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry and infectivity. Science, 370(6518), 856–860. 10.1126/science.abd2985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Fan, J. , Chen, Z. , Zhang, M. , Peng, H. , Liu, J. , Ding, L. , Liu, M. , Zhao, C. , Zhao, P. , Zhang, S. , Zhang, X. , & Xu, J. (2021). Nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA facilitates SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in human pulmonary cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(50), e2111011118. 10.1073/pnas.2111011118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. , Pekosz, A. , Villano, J. S. , Shen, W. , Zhou, R. , Kulaga, H. , & Lane, A. P. (2022). Evolution of nasal and olfactory infection characteristics of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants. bioRxiv: The Preprint Server for Biology. 10.1101/2022.04.12.487379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. , Zhou, M. , Dong, X. , Qu, J. , Gong, F. , Han, Y. , Qiu, Y. , Wang, J. , Liu, Y. , Wei, Y. , Xia, J. , Yu, T. , Zhang, X. , & Zhang, L. (2020). Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. The Lancet, 395(10223), 507–513. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. , Wang, K. , Yu, J. , Howard, D. , French, L. , Chen, Z. , Wen, C. , & Xu, Z. (2021). The spatial and cell‐type distribution of SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor ACE2 in the human and mouse brains. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 573095. 10.3389/fneur.2020.573095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. , Park, J.‐E. , Tsagkogeorga, G. , Yanagita, M. , Koo, B.‐K. , Han, N. , & Lee, J.‐H. (2020). Inflammatory signals induce AT2 cell‐derived damage‐associated transient progenitors that mediate alveolar regeneration. Cell Stem Cell, 27(3), 366–382. 10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H. , Chan, J. F.‐W. , Wang, Y. , Yuen, T. T.‐T. , Chai, Y. , Hou, Y. , Shuai, H. , Yang, D. , Hu, B. , Huang, X. , Zhang, X. , Cai, J. P. , Zhou, J. , Yuan, S. , Kok, K. H. , To, K. K. W. , Chan, I. H. Y. , Zhang, A. J. , Sit, K. Y. , … Yuen, K. Y. (2020). Comparative replication and immune activation profiles of SARS‐CoV‐2 and SARS‐CoV in human lungs: An ex vivo study with implications for the pathogenesis of COVID‐19. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71, 1400–1409. 10.1093/cid/ciaa410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H. , Chan, J. F.‐W. , Wang, Y. , Yuen, T. T.‐T. , Chai, Y. , Shuai, H. , Yang, D. , Hu, B. , Huang, X. , Zhang, X. , Hou, Y. , Cai, J. P. , Zhang, A. J. , Zhou, J. , Yuan, S. , To, K. K. W. , Hung, I. F. N. , Cheung, T. T. , Ng, A. T. L. , … Yuen, K. Y. (2021). SARS‐CoV‐2 induces a more robust innate immune response and replicates less efficiently than SARS‐CoV in the human intestines: An ex vivo study with implications on pathogenesis of COVID‐19. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 11(3), 771–781. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2020.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H. , Chan, J. F. W. , Yuen, T. T. T. , Shuai, H. , Yuan, S. , Wang, Y. , Hu, B. , Yip, C. C. Y. , Tsang, J. O. L. , Huang, X. , Chai, Y. , Yang, D. , Hou, Y. , Chik, K. K. H. , Zhang, X. , Fung, A. Y. F. , Tsoi, H. W. , Cai, J. P. , Chan, W. M. , … Yuen, K. Y. (2020). Comparative tropism, replication kinetics, and cell damage profiling of SARS‐CoV‐2 and SARS‐CoV with implications for clinical manifestations, transmissibility, and laboratory studies of COVID‐19: An observational study. The Lancet Microbe, 1(1), e14–e23. 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30004-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, T. M. , Sandoval, D. R. , Spliid, C. B. , Pihl, J. , Perrett, H. R. , Painter, C. D. , Narayanan, A. , Majowicz, S. A. , Kwong, E. M. , McVicar, R. N. , Thacker, B. E. , Glass, C. A. , Yang, Z. , Torres, J. L. , Golden, G. J. , Bartels, P. L. , Porell, R. N. , Garretson, A. F. , Laubach, L. , … Esko, J. D. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 infection depends on cellular heparan sulfate and ACE2. Cell, 183(4), 1043–1057. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coate, K. C. , Cha, J. , Shrestha, S. , Wang, W. , Gonçalves, L. M. , Almaça, J. , Kapp, M. E. , Fasolino, M. , Morgan, A. , Dai, C. , Saunders, D. C. , Bottino, R. , Aramandla, R. , Jenkins, R. , Stein, R. , Kaestner, K. H. , Vahedi, G. , Brissova, M. , & Powers, A. C. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry factors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed in the microvasculature and ducts of human pancreas but are not enriched in β cells. Cell Metabolism, 32(6), 1028–1040. 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colavita, F. , Lapa, D. , Carletti, F. , Lalle, E. , Bordi, L. , Marsella, P. , Nicastri, E. , Bevilacqua, N. , Giancola, M. L. , Corpolongo, A. , Ippolito, G. , Capobianchi, M. R. , & Castilletti, C. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 isolation from ocular secretions of a patient with COVID‐19 in Italy with prolonged viral RNA detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(3), 242–243. 10.7326/M20-1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin, J. , Queen, R. , Zerti, D. , Dorgau, B. , Georgiou, M. , Djidrovski, I. , Hussain, R. , Coxhead, J. M. , Joseph, A. , Rooney, P. , Lisgo, S. , Figueiredo, F. , Armstrong, L. , & Lako, M. (2021). Co‐expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry genes in the superficial adult human conjunctival, limbal and corneal epithelium suggests an additional route of entry via the ocular surface. The Ocular Surface, 19, 190–200. 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, G. , Todisco, M. , Hota, N. , Della Porta, G. , Morbini, P. , Tassorelli, C. , & Pisani, A. (2021). Neuropathological findings from COVID‐19 patients with neurological symptoms argue against a direct brain invasion of SARS‐CoV‐2: A critical systematic review. European Journal of Neurology, 28(11), 3856–3865. 10.1111/ene.15045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cugola, F. R. , Fernandes, I. R. , Russo, F. B. , Freitas, B. C. , Dias, J. L. M. , Guimarães, K. P. , Benazzato, C. , Almeida, N. , Pignatari, G. C. , Romero, S. , Polonio, C. M. , Cunha, I. , Freitas, C. L. , Brandão, W. N. , Rossato, C. , Andrade, D. G. , Faria, D. P. , Garcez, A. T. , Buchpigel, C. A. , … Beltrão‐Braga, P. C. B. (2016). The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature, 534(7606), 267–271. 10.1038/nature18296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly, J. L. , Simonetti, B. , Klein, K. , Chen, K. ‐E. , Williamson, M. K. , Antón‐Plágaro, C. , Shoemark, D. K. , Simón‐Gracia, L. , Bauer, M. , Hollandi, R. , Greber, U. F. , Horvath, P. , Sessions, R. B. , Helenius, A. , Hiscox, J. A. , Teesalu, T. , Matthews, D. A. , Davidson, A. D. , Collins, B. M. , … Yamauchi, Y. (2020). Neuropilin‐1 is a host factor for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Science, 370(6518), 861–865. 10.1126/science.abd3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang, J. , Tiwari, S. K. , Lichinchi, G. , Qin, Y. , Patil, V. S. , Eroshkin, A. M. , & Rana, T. M. (2016). Zika virus depletes neural progenitors in human cerebral organoids through activation of the innate immune receptor TLR3. Cell Stem Cell, 19(2), 258–265. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt‐Emmer, S. , Wittschieber, D. , Sanft, J. , Kleemann, S. , Elschner, S. , Haupt, K. F. , Vau, V. , Häring, C. , Rödel, J. , Henke, A. , Ehrhardt, C. , Bauer, M. , Philipp, M. , Gaßler, N. , Nietzsche, S. , Löffler, B. , & Mall, G. (2021). Early postmortem mapping of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in patients with COVID‐19 and the correlation with tissue damage. eLife, 10, e60361. 10.7554/eLife.60361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorey, T. M. , Ziegler, C. G. K. , Heimberg, G. , Normand, R. , Yang, Y. , Segerstolpe, Å. , Abbondanza, D. , Fleming, S. J. , Subramanian, A. , Montoro, D. T. , Jagadeesh, K. A. , Dey, K. K. , Sen, P. , Slyper, M. , Pita‐Juárez, Y. H. , Phillips, D. , Biermann, J. , Bloom‐Ackermann, Z. , Barkas, N. , … Regev, A. (2021). COVID‐19 tissue atlases reveal SARS‐CoV‐2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature, 595(7865), 107–113. 10.1038/s41586-021-03570-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W. , Bao, L. , Gao, H. , Xiang, Z. , Qu, Y. , Song, Z. , Gong, S. , Liu, J. , Liu, J. , Yu, P. , Qi, F. , Xu, Y. , Li, F. , Xiao, C. , Lv, Q. , Xue, J. , Wei, Q. , Liu, M. , Wang, G. , … Qin, C. (2020). Ocular conjunctival inoculation of SARS‐CoV‐2 can cause mild COVID‐19 in rhesus macaques. Nature Communications, 11(1), 4400. 10.1038/s41467-020-18149-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao, B. , Wang, C. , Wang, R. , Feng, Z. , Zhang, J. , Yang, H. , Tan, Y. , Wang, H. , Wang, C. , Liu, L. , Liu, Y. , Liu, Y. , Wang, G. , Yuan, Z. , Hou, X. , Ren, L. , Wu, Y. , & Chen, Y. (2021). Human kidney is a target for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Nature Communications, 12(1), 2506. 10.1038/s41467-021-22781-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J. , Adiconis, X. , Simmons, S. K. , Kowalczyk, M. S. , Hession, C. C. , Marjanovic, N. D. , Hughes, T. K. , Wadsworth, M. H. , Burks, T. , Nguyen, L. T. , Kwon, J. Y. H. , Barak, B. , Ge, W. , Kedaigle, A. J. , Carroll, S. , Li, S. , Hacohen, N. , Rozenblatt‐Rosen, O. , Shalek, A. K. , … Levin, J. Z. (2020). Systematic comparison of single‐cell and single‐nucleus RNA‐sequencing methods. Nature Biotechnology, 38(6), 737–746. 10.1038/s41587-020-0465-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmayer, C. , Meinhardt, J. , Radbruch, H. , Radke, J. , Heppner, B. I. , Heppner, F. L. , Stenzel, W. , Holland, G. , & Laue, M. (2020). Why misinterpretation of electron micrographs in SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected tissue goes viral. The Lancet, 396(10260), e64–e65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32079-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni, C. , Ravaglia, C. , Chilosi, M. , Rossi, G. , Dubini, A. , Pedica, F. , Piciucchi, S. , Vizzuso, A. , Stella, F. , Maitan, S. , Agnoletti, V. , Puglisi, S. , Poletti, G. , Sambri, V. , Pizzolo, G. , Bronte, V. , Wells, A. U. , & Poletti, V. (2021). Covid‐19 interstitial pneumonia: Histological and immunohistochemical features on cryobiopsies. Respiration, 100(6), 488–498. 10.1159/000514822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, M. , Le Coupanec, A. , Wong, A. H. M. , Rini, J. M. , Desforges, M. , & Talbot, P. J. (2018). Axonal transport enables neuron‐to‐neuron propagation of human coronavirus OC43. Journal of Virology, 92(17), e00404‐18. 10.1128/JVI.00404-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Jamal, S. M. , Pujadas, E. , Ramos, I. , Bryce, C. , Grimes, Z. M. , Amanat, F. , Tsankova, N. M. , Mussa, Z. , Olson, S. , Salem, F. , Miorin, L. , Aydillo, T. , Schotsaert, M. , Albrecht, R. A. , Liu, W. C. , Marjanovic, N. , Francoeur, N. , Sebra, R. , Sealfon, S. C. , … Westra, W. H. (2021). Tissue‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 detection in fatal COVID‐19 infections: Sustained direct viral‐induced damage is not necessary to drive disease progression. Human Pathology, 114, 110–119. 10.1016/j.humpath.2021.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, A. Z. , Møller, R. , Makovoz, B. , Uhl, S. A. , tenOever, B. R. , & Blenkinsop, T. A. (2021). SARS‐CoV‐2 infects human adult donor eyes and hESC‐derived ocular epithelium. Cell Stem Cell, 28(7), 1205–1220. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.04.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fignani, D. , Licata, G. , Brusco, N. , Nigi, L. , Grieco, G. E. , Marselli, L. , Overbergh, L. , Gysemans, C. , Colli, M. L. , Marchetti, P. , Mathieu, C. , Eizirik, D. L. , Sebastiani, G. , & Dotta, F. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor angiotensin I‐converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2) is expressed in human pancreatic β‐cells and in the human pancreas microvasculature. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 11, 596898. 10.3389/fendo.2020.596898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodoulian, L. , Tuberosa, J. , Rossier, D. , Boillat, M. , Kan, C. , Pauli, V. , Egervari, K. , Lobrinus, J. A. , Landis, B. N. , Carleton, A. , & Rodriguez, I. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 receptors and entry genes are expressed in the human olfactory neuroepithelium and brain. iScience, 23(12), 101839. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullard, J. F. , Lee, H.‐C. , Voloudakis, G. , Suo, S. , Javidfar, B. , Shao, Z. , Peter, C. , Zhang, W. , Jiang, S. , Corvelo, A. , Wargnier, H. , Woodoff‐Leith, E. , Purohit, D. P. , Ahuja, S. , Tsankova, N. M. , Jette, N. , Hoffman, G. E. , Akbarian, S. , Fowkes, M. , … Roussos, P. (2021). Single‐nucleus transcriptome analysis of human brain immune response in patients with severe COVID‐19. Genome Medicine, 13(1), 118. 10.1186/s13073-021-00933-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, C. S. , Miller, S. E. , Martines, R. B. , Bullock, H. A. , & Zaki, S. R. (2020). Electron microscopy of SARS‐CoV‐2: A challenging task. The Lancet, 395(10238), e99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31188-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grün, D. , Kester, L. , & van Oudenaarden, A. (2014). Validation of noise models for single‐cell transcriptomics. Nature Methods, 11(6), 637–640. 10.1038/nmeth.2930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J. , Wei, X. , Li, Q. , Li, L. , Yang, Z. , Shi, Y. , Qin, Y. , Zhang, X. , Wang, X. , Zhi, X. , & Meng, D. (2020). Single‐cell RNA analysis on ACE2 expression provides insights into SARS‐CoV‐2 potential entry into the bloodstream and heart injury. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 235(12), 9884–9894. 10.1002/jcp.29802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T. , Fan, Y. , Chen, M. , Wu, X. , Zhang, L. , He, T. , Wang, H. , Wan, J. , Wang, X. , & Lu, Z. (2020). Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiology, 5, 811. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassler, L. , Reyes, F. , Sparks, M. A. , Welling, P. , & Batlle, D. (2021). Evidence for and against direct kidney infection by SARS‐CoV‐2 in patients with COVID‐19. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 16(11), 1755–1765. 10.2215/CJN.04560421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide, V. , Jangra, S. , Cohen, P. , Rathnasinghe, R. , Aslam, S. , Aydillo, T. , Geanon, D. , Handler, D. , Kelley, G. , Lee, B. , Rahman, A. , Dawson, T. , Qi, J. , D'Souza, D. , Kim‐Schulze, S. , Panzer, J. K. , Caicedo, A. , Kusmartseva, I. , Posgai, A. L. , … Homann, D. (2022). Limited extent and consequences of pancreatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Cell Reports, 38(11), 110508. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikmet, F. , Méar, L. , Edvinsson, Å. , Micke, P. , Uhlén, M. , & Lindskog, C. (2020). The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Molecular Systems Biology, 16(7), e9610. 10.15252/msb.20209610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J. S. , Ng, J. H. , Ross, D. W. , Sharma, P. , Shah, H. H. , Barnett, R. L. , Fishbane, S. , Jhaveri, K. D. , Abate, M. , Andrade, H. P. , Barnett, R. L. , Bellucci, A. , Bhaskaran, M. C. , Corona, A. G. , Chang, B. F. , Finger, M. , Fishbane, S. , Gitman, M. , Halinski, C. , … Ng, J. H. , Northwell Nephrology COVID‐19 Research Consortium . (2020). Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID‐19. Kidney International, 98(1), 209–218. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland, D. A. , Møller, R. , Uhl, S. A. , Oishi, K. , Frere, J. , Golynker, I. , Horiuchi, S. , Panis, M. , Blanco‐Melo, D. , Sachs, D. , Arkun, K. , Lim, J. K. , & tenOever, B. R. (2021). Leveraging the antiviral type I interferon system as a first line of defense against SARS‐CoV‐2 pathogenicity. Immunity, 54(3), 557–570. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M. , Kleine‐Weber, H. , & Pöhlmann, S. (2020). A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS‐CoV‐2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Molecular Cell, 78, 779–784. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, M. , Kleine‐Weber, H. , Schroeder, S. , Krüger, N. , Herrler, T. , Erichsen, S. , Schiergens, T. S. , Herrler, G. , Wu, N. H. , Nitsche, A. , Müller, M. A. , Drosten, C. , & Pöhlmann, S. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell, 181, 271–280. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfer, H. , Herzig, M. C. , Gosert, R. , Menter, T. , Hench, J. , Tzankov, A. , Hirsch, H. H. , & Miller, S. E. (2021). Hunting coronavirus by transmission electron microscopy—A guide to SARS‐CoV‐2‐associated ultrastructural pathology in COVID‐19 tissues. Histopathology, 78(3), 358–370. 10.1111/his.14264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y. J. , Okuda, K. , Edwards, C. E. , Martinez, D. R. , Asakura, T. , Dinnon, K. H., 3rd , Kato, T. , Lee, R. E. , Yount, B. L. , Mascenik, T. M. , Chen, G. , Olivier, K. N. , Ghio, A. , Tse, L. V. , Leist, S. R. , Gralinski, L. E. , Schäfer, A. , Dang, H. , Gilmore, R. , … Baric, R. S. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 reverse genetics reveals a variable infection gradient in the respiratory tract. Cell, 182(2), 429–446. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. , Wang, Y. , Li, X. , Ren, L. , Zhao, J. , Hu, Y. , Zhang, L. , Fan, G. , Xu, J. , Gu, X. , Cheng, Z. , Yu, T. , Xia, J. , Wei, Y. , Wu, W. , Xie, X. , Yin, W. , Li, H. , Liu, M. , … Cao, B. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet, 395(10223), 497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. , Guo, H. , Zhou, P. , & Shi, Z.‐L. (2021). Characteristics of SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 19(3), 141–154. 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F. , Chen, F. , Ou, Z. , Fan, Q. , Tan, X. , Wang, Y. , Pan, Y. , Ke, B. , Li, L. , Guan, Y. , Mo, X. , Wang, J. , Wang, J. , Luo, C. , Wen, X. , Li, M. , Ren, P. , Ke, C. , Li, J. , … Li, F. (2020). A compromised specific humoral immune response against the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor‐binding domain is related to viral persistence and periodic shedding in the gastrointestinal tract. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 17(11), 1119–1125. 10.1038/s41423-020-00550-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C. B. , Farzan, M. , Chen, B. , & Choe, H. (2021). Mechanisms of SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 23, 3–20. 10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, F. , Pather, S. R. , Huang, W.‐K. , Zhang, F. , Wong, S. Z. H. , Zhou, H. , Cubitt, B. , Fan, W. , Chen, C. Z. , Xu, M. , Pradhan, M. , Zhang, D. Y. , Zheng, W. , Bang, A. G. , Song, H. , Carlos de la Torre, J. , & Ming, G. (2020). Human pluripotent stem cell‐derived neural cells and brain organoids reveal SARS‐CoV‐2 neurotropism predominates in choroid plexus epithelium. Cell Stem Cell, 27(6), 937–950. 10.1016/j.stem.2020.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, J. , Reimer, K. C. , Nagai, J. S. , Varghese, F. S. , Overheul, G. J. , de Beer, M. , Roverts, R. , Daviran, D. , Fermin, L. A. S. , Willemsen, B. , Beukenboom, M. , Djudjaj, S. , von Stillfried, S. , van Eijk, L. E. , Mastik, M. , Bulthuis, M. , Dunnen, W. , van Goor, H. , Hillebrands, J. L. , … Pai, R. (2022). SARS‐CoV‐2 infects the human kidney and drives fibrosis in kidney organoids. Cell Stem Cell, 29(2), 217–231. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.‐D. , Liu, M.‐Q. , Chen, Y. , Shan, C. , Zhou, Y.‐W. , Shen, X.‐R. , Li, Q. , Zhang, L. , Zhu, Y. , Si, H. R. , Wang, Q. , Min, J. , Wang, X. , Zhang, W. , Li, B. , Zhang, H. J. , Baric, R. S. , Zhou, P. , Yang, X. L. , & Shi, Z. L. (2020). Pathogenesis of SARS‐CoV‐2 in transgenic mice expressing human angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2. Cell, 182(1), 50–58. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]