Abstract

Ehrlichia canis, an obligatory intracellular bacterium of monocytes and macrophages, causes canine monocytic ehrlichiosis. E. canis immunodominant 30-kDa major outer membrane proteins are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family consisting of more than 20 paralogs. In the present study, we analyzed the mRNA expression of 14 paralogs in experimentally infected dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks by reverse transcription-PCR using gene-specific primers followed by Southern blotting. Eleven out of 14 paralogs in E. canis were transcribed in increasing numbers and transcription levels, while the mRNA expression of the 3 remaining paralogs was not detected in blood monocytes of infected dogs during the 56-day postinoculation period. Three different groups of R. sanguineus ticks (adult males and females and nymphs) were separately infected with E. canis by feeding on the infected dogs. In these pools of acquisition-fed ticks as well as in the transmission-fed adult ticks, the transcript from only one paralog was detected, suggesting the predominant transcription of that paralog or the suppression of the remaining paralogs in ticks. Expression of the same paralog was higher whereas expression of the remaining paralogs was lower in E. canis cultivated in dog monocyte cell line DH82 at 25°C than in E. canis cultivated at 37°C. Analysis of differential expression of p30 multigenes in dogs, ticks, or monocyte cell cultures would help in understanding the role of these gene products in pathogenesis and E. canis transmission as well as in designing a rational vaccine candidate immunogenic against canine ehrlichiosis.

Ehrlichia canis is the causative agent of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME) with tropism for monocytes and macrophages. CME was originally described in Algeria in 1935 (4) and is currently reported throughout the world, with a higher frequency in tropical and subtropical regions. E. canis has been shown to be transstadially transmitted by the nymph and adult stages of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus, and by the adult stage of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (7, 9, 12, 13).

Eight to 20 days following tick transmission (acute phase), CME may be manifested by fever, depression, dyspnea, anorexia, and slight weight loss, with laboratory findings of thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, mild anemia, and hypergammaglobulinemia. A subclinical phase follows the acute phase and is associated with persistent E. canis infection and mild thrombocytopenia that may last 40 to 120 days or years. The chronic phase is characterized by hemorrhages, epistaxis, and edema in addition to the clinical signs and laboratory findings of the acute phase, which are often complicated by superinfection with other microorganisms (2, 3, 6, 8, 11). Once dogs are infected with E. canis, they may remain infected for life, even after 1 year of treatment with doxycycline (31).

E. canis 30-kDa proteins (P30s) were found to be immunodominant antigens and highly cross-reactive with 28-kDa antigens (OMP-1s) of E. chaffeensis, the agent of human monocytic ehrlichiosis, by Western blot analysis of sera from experimentally and clinically infected dogs (15, 21, 29). E. chaffeensis is closely related to E. canis on the basis of 16S rRNA gene sequence comparison (1). P30s and OMP-1s are encoded by a single polymorphic multigene family (14, 15, 16), and immunization of mice with recombinant OMP-1 protected the mice from ehrlichial infection (14).

Recent characterization and expression analyses of the E. canis multigene family have revealed 22 polymorphic genes which are homologous but not identical to p30 (71.8 to 19.2% amino acid identity) and which are tandemly arranged as a cluster on the 28-kb locus as well as a repeat of three tandem genes on the 6.7 kb locus of the E. canis genome (16). The 5′ end of the 28-kb locus consists of paralogs linked by short intergenic spaces, while the paralogs at the 3′ end are connected by longer intergenic spaces. All p30 paralogs have also been reported to be transcriptionally active in DH82 cells, a canine monocyte cell line, when analyzed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (16). The transcriptional activity of E. canis p30 paralogs during infection of mammalian and arthropod hosts is, however, unknown. In the present study, we analyzed the expression of p30 paralogs in experimentally infected dogs and ticks by RT-PCR followed by Southern blotting. Furthermore, we compared the transcription of p30 paralogs in E. canis cultivated at 37 and 25°C. The present study is expected to facilitate understanding of the role of these genes in pathogenesis and transmission and to provide information with respect to a vaccine candidate immunogen for the prevention of canine ehrlichiosis.

(Part of this study was presented at the 100th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Los Angeles, Calif., 22 May 2000 [A. Unver, T. Tajima, N. Ohashi, Y. Rikihisa, and R. W. Stich, abstr. no. D-74, p. 242, 2000].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism and culture.

The Oklahoma isolate of E. canis was cultivated in DH82 cells and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl-piperazine)-N′-(4-butanesulfonic acid) buffer in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2–95% air as previously described (21). E. canis was purified by Sephacryl S-1000 column chromotography to extract genomic DNA (21).

Experimental infection of dogs.

Four specific-pathogen-free female dogs (1 to 2 years old) were used. Two dogs, 10184 and 9673, were mixed-breed hounds that weighed 18 and 20 kg, respectively (Kaiser Lake Kennels, St. Paris, Ohio). Dogs CBT7 and FAV7 were beagles that each weighed 13 kg (Batelle, Columbus, Ohio). All dogs were determined to be free of E. canis infection by indirect fluorescent-antibody (IFA) and PCR tests. Dogs 10184 and 9673 were intravenously inoculated with 5 × 106 (high-dosage dog) and 5 × 104 (low-dosage dog) E. canis-infected DH82 cells in 5 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, respectively. Heparinized blood samples (30 ml) were collected from the cephalic vein every 3 days between 0 and 21 days postinoculation (p.i.) and once a week between 21 and 56 days p.i. for the IFA test, RT-PCR, complete blood count, and PCR. Rectal temperature, appetite, attitude, and any clinical changes were recorded daily.

Tick attachment.

Uninfected laboratory-reared R. sanguineus ticks were obtained from the Medical Entomology Laboratory, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, and maintained by the method of Patrick and Hair (19). Ticks were placed within feeding cells made with orthopedic stockinettes attached to the dogs with a water-based adhesive (3 M, St. Paul, Minn.). Ticks were allowed to acquisition feed on dogs 10184 and 9673 beginning on day 72 after inoculation with E. canis. One hundred adult males, 100 adult females, and 500 nymphs were placed into each of three separate feeding cells on dog 10184. On dog 9673, 100 males, 100 females, and 250 nymphs were placed in a similar manner. Attachment to the host and engorgement of ticks were monitored daily. All adult ticks were removed from dogs 7 days after attachment and kept in humidified chambers at room temperature. Adult ticks were kept for 10 days for blood meal digestion, and engorged nymphs were incubated for 2 months to allow molting. For transmission feeding, 30 male and 22 female ticks infected as adults on dog 10184 and 10 male and 20 female ticks infected as adults on dog 9673 were attached to the uninfected hosts, dogs CBT7 and FAV7, respectively. Female ticks failed to reattach and were removed from the feeding cells on the next day. Male ticks reattached and were allowed to feed for 10 days; they were then removed and dissected immediately. One group of uninfected laboratory-reared ticks was used as a negative control for PCR and RT-PCR.

IFA test.

IFA testing of serially collected dog plasma samples was performed as described elsewhere (21). DH82 cells infected with the Oklahoma isolate of E. canis were used for the preparation of antigen slides, and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-dog immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, Pa.) was used at a 1:200 dilution as a secondary antibody (29).

DNA isolation from specimens and PCR.

After centrifugation of heparinized blood samples from experimentally infected dogs, plasma was collected and saved for serologic analysis. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by overlaying the buffy coat on Histopaque 1077 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and the interface fractions containing mononuclear cells were collected. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (137 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.2]), and DNA was isolated from 107 PBMCs with a QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Ticks were dissected with a sterile razor blade by dividing the body along the median plane under a dissecting microscope. Salivary glands, midguts, and body halves were pooled from five or six ticks and used for DNA or RNA extraction. DNA was purified from tick tissues with DNAzol reagent (Life Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nested PCR was carried out to detect E. canis DNA in canine PBMCs and tick tissues as previously described with primers ECC-ECB (outside pairs) and HE3-ECA (nested pairs) specific for the 16S rRNA gene of E. canis (31).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from 107 PBMCs from experimentally infected dogs and pools of tissues from five or six ticks (body halves, salivary glands, and midguts) with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The final RNA pellet was resuspended in Tris-Mg buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 10 mM MgCl2) and treated with 3 U of RNase-free DNase I (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.) at 37°C for 30 min. DNase I was removed from the RNA samples with an RNeasy mini column kit (Qiagen according to the manufacturer's instructions. Half of the total cellular RNA eluted from the column with diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated distilled deionized sterile water was heated at 70°C for 10 min and reverse transcribed in a 20-μl reaction mixture (10 mM random hexamer, 0.5 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1 U of RNase inhibitor [Life Technologies], 200 U of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase [Life Technologies]) at 42°C for 50 min. PCR was performed separately for each paralog with a 50-μl reaction mixture including 1 μl of the cDNA product, 10 pmol of a gene-specific primer pair (16), 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 1.5 mM MgCl2; 3 min of denaturation at 94°C was followed by 40 cycles consisting of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1 min of annealing at 54°C, and 1 min of extension at 72°C. For p30-5 and p30-4, PCR and RT-PCR utilized slightly different regions as targets (nucleotides [nt] 14445 to 14616 and nt 16963 to 17359, respectively), based on the 28-kb omp locus of E. canis (16). The final extension was allowed to continue for 7 min.

The other half of the total RNA was processed using the same procedures but without reverse transcriptase, and PCR was carried out with the same reaction mixture as a negative control to rule out DNA contamination in the RNA preparation. As a positive control, PCR was performed separately for each paralog with a gene-specific primer pair and 0.5 ng of purified E. canis DNA as a template (Fig 1B). To estimate ehrlichial RNA in each specimen, the one-step PCR was performed with a primer pair (HE3-ECA) specific for the 16S rRNA gene of E. canis, reaction mixture and PCR conditions identical to those described for RT-PCR, 2 μl of the cDNA template, 60°C annealing, and 27 cycles. PCR products were elecrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide (EtBr).

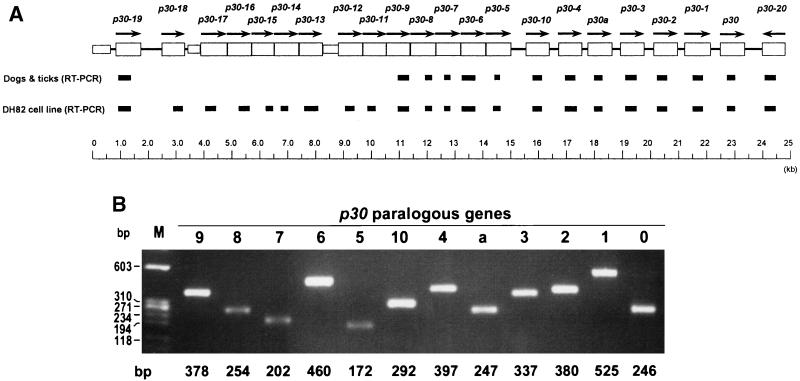

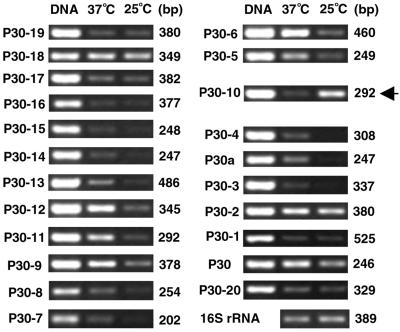

FIG. 1.

(A) Region of the p30 multigene cluster of E. canis tested by RT-PCR. Open boxes and arrows show p30 paralogs and their orientations. Closed boxes indicate the amplified RT-PCR region (see Materials and Methods). (B) PCR utilizing purified E. canis DNA (0.5 ng) as a template and gene-specific primer pairs, showing the strength and specificity of each reaction. The amplified products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. p30 paralogous genes are identified on the top. Lane M, molecular size markers (φX174 replicative-form DNA HaeIII fragments [Life Technologies]). Sizes of markers and amplified products are indicated on the left and bottom, respectively.

To investigate the effect of low temperature on p30 gene expression, E. canis-infected cells cultivated at 37 or 25°C were harvested when ∼60% of the cells were infected. To make sure that mRNA produced at 37°C was turned over, E. canis was grown in DH82 cells at 25°C for 8 days. Total RNA was prepared from 5 × 106 E. canis-infected DH82 cells using the RNeasy mini column kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. A 5-μg RNA sample was treated with 10 U of DNase I (Epicentre). The removal of DNase I, cDNA synthesis from 2.5 μg of isolated RNA, and PCR were performed as described above, except that 0.5 μl of the cDNA product was used as the template for amplifications consisting of 28 thermal cycles.

Estimation of RT-PCR sensitivity.

The sensitivity of RT-PCR was estimated by using p30 gene-specific RNA by a modification of the procedure described by Shaw et al. (27). Two paralogs, p30-5 and p30-10, were selected as representatives for the sensitivity assay based on the results of PCR with DNA from purified E. canis as a template (Fig. 1B) and expression analyses shown in Fig. 3 and 4. In order to create in vitro transcripts specific for p30-5 and p30-10, PCR fragments were produced with forward primers designed based on the upstream sequences of the forward primers used in RT-PCR with the addition of the T7 RNA polymerase binding site sequence at the 5′ ends and reverse primers designed based on the downstream sequences of the reverse primers used in RT-PCR. For p30-5, the forward and reverse primers were (T7 binding site is underlined) 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGCTAAAAAGTACTACGGAT-3′ and 5′-ATCTTGCAAGTTCAGCAAC-3′, respectively. These primers were located 217 bp upstream and 319 bp downstream from the 5′ end (14445 bp) and the 3′ end (14616 bp) of the RT-PCR region (Fig. 1), respectively. For p30-10, the forward and reverse primers were 5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTCAAGAACTAATGATAACAAAG-3′ and 5′-AGCATCATTTAATACTACTCC-3′, respectively. These primers were located 178 bp upstream and 208 bp downstream from the 5′ end (16963 bp) and the 3′ end (17359 bp) of the RT-PCR region, respectively.

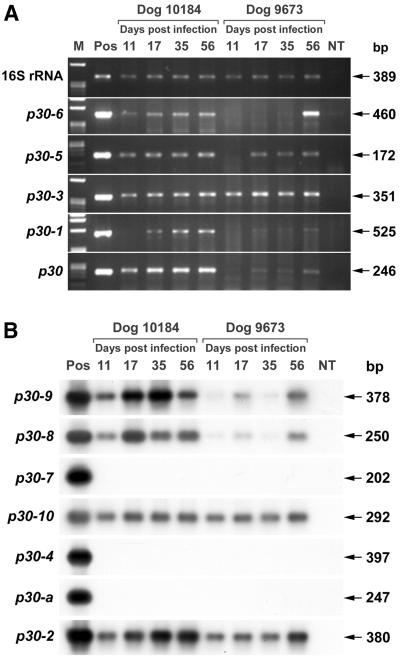

FIG. 3.

(A) mRNA expression of five p30 paralogs (p30-6, p30-5, p30-3, p30-1, and p30) and 16S rRNA of E. canis in PBMCs of two experimentally infected dogs at different days p.i. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. The amplified products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr. p30 paralogs are identified on the left. Lane M, molecular size markers (φX174 replicative-form DNA HaeIII fragments); lane Pos, product amplified by PCR with DNA from purified E. canis as a template and respective primer pairs, used as a positive control for each PCR and as a determinant of amplicon size on the gel; lane NT, no template. Sizes of amplified products are indicated on the right. Dog 10184, high dosage; dog 9673, low dosage. (B) Transcriptional profiles of seven p30 paralogs (p30-9, p30-8, p30-7, p30-10, p30-4, p30-a, and p30-2) in PBMCs of two experimentally infected dogs at different days p.i., determined by RT-PCR followed by Southern blot analysis. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the amplified products were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe specific for each p30 paralog. Lane Pos, positive control with purified E. canis DNA as a template; lane NT, no template. Sizes of amplified products are indicated on the right. Dog 10184, high dosage; dog 9673, low dosage.

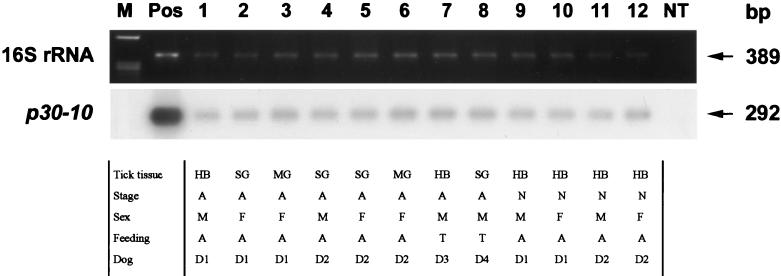

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional profiles of p30-10 in 12 different pools of ticks, determined by RT-PCR followed by Southern blotting. Total tick RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. After agarose gel electrophoresis, the amplified products were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with a radioactively labeled probe specific for p30-10. The top panel shows EtBr-stained RT-PCR products of E. canis 16S rRNA. Lane M, molecular size markers (φX174 replicative-form DNA HaeIII fragments); lane Pos, positive control with E. canis DNA as a template; lanes 1 to 12, different pools of tick specimens; lane NT, no template. Sizes of amplified products are indicated on the right. Samples in lanes 9 to 12 were from nymphs after molting. Tick tissue: HB, half body; SG, salivary gland; MG, midgut. Stage, when attached: A, adult; N, nymph. Sex: M, male; F, female. Feeding: A, acquisition; T, transmission. Dog: D1, dog 10184; D2, dog 9673; D3, dog FAV7, D4, dog CBT7.

After PCR was performed with these primers and genomic DNA, the amplicon was purified and used as a template for generating specific in vitro runoff transcripts with an AmpliScribe T7 transcription kit (Epicentre). The transcripts were treated with 1.5 U of DNase I from the kit for 30 min at 37°C, and DNase I was removed by the RNeasy column method as described above. The transcripts were enumerated by measuring the A260 with a GeneQuant II RNA and DNA calculator (Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Cambridge, England). In the sensitivity assay, cDNAs were synthesized as previously described from 10-fold-diluted transcripts. Each dilution of transcripts was spiked with total RNA (corresponding to 5 × 106 PBMCs) from PBMCs from an uninfected dog. From 20 μl of cDNA, 1 μl was used for PCR with primers and conditions identical to those described above for RT-PCR.

Southern blot analysis.

For preparation of probes, DNA fragments were amplified from E. canis genomic DNA with the respective primer pairs used for PCR and RT-PCR. Amplicons purified from gels with a QIAEX II kit (Qiagen) were labeled with [α-32P]dATP by the random primer method with a multiprime DNA labeling system (Amersham International Plc., Amersham, United Kingdom) and used as DNA probes. RT-PCR products were electrophoresed and transferred to Hybond-N+ nylon membranes (Amersham) as described elsewhere (24). Hybridizations were performed separately with 32P-labeled DNA probes in rapid hybridization buffer (Amersham) at 65°C for 20 h. The blots were washed twice at 55°C for 30 min with 1× SSC (0.15 M sodium chloride plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and with 0.1× SSC, both including 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. The membranes were exposed to Hyperfilm at −80°C and PhosphorImager cassettes (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.) at room temperature.

RESULTS

Experimental infection of dogs with E. canis.

Dog 10184 (high dosage) and dog 9673 (low dosage) developed mild clinical signs and laboratory findings of CME starting on day 14 p.i. and continuing through day 56 p.i. Both dogs developed transient fever (40°C from 12 to 14 days p.i.) and more than a 50% reduction in platelet counts relative to the inoculation-day counts from day 14 p.i. through day 56 p.i.. Both dogs seroconverted at 1 week p.i., and the titer of E. canis in IFA tests reached 1:2,560 at 2 weeks p.i.. IFA titers remained at 1:5,120 to 1:10,240 through day 56 p.i., and E. canis DNA was detected in PBMCs by nested PCR starting on day 7 p.i. and continuing through day 56 p.i..

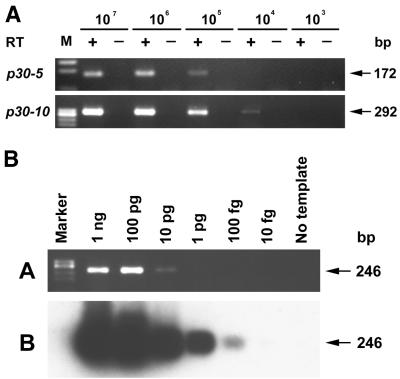

Sensitivity of RT-PCR and Southern blotting.

p30-5 and p30-10 were selected as representatives to estimate the sensitivity of RT-PCR, because p30-5 was most weakly detected by the gene-specific primer (Fig. 1B) and p30-10 was universally expressed in both dogs and ticks (Fig. 3 and 4). In vitro-generated specific transcripts of p30-5 and p30-10 were 10-fold serially diluted and used in RT-PCR against a background of total RNA from 2.5 × 106 uninfected dog PBMCs to mimic the experimental conditions (Fig. 2A). Under our standard RT-PCR conditions, 172- and 292-bp cDNA fragments of p30-5 and p30-10, respectively, were detected to the levels of 105 and 104 transcripts, respectively. The detection limit of the nested PCR based on the 16S rRNA gene was 0.2 pg (in the PCR tube) of purified E. canis DNA, corresponding to 1,000 E. canis genomes in 2.5 × 106 PBMCs. All dog and tick specimens examined in the present study were 16S rRNA gene-based nested PCR positive. This means that at least 1,000 E. canis genomes were present in each specimen. Therefore, when p30 transcripts were not detectable in these specimens by RT-PCR, the transcript number was less than 100 per E. canis genome. Because the sensitivity of Southern blot hybridization was 100 times that of RT-PCR (Fig. 2B), the lack of detection of an RT-PCR product by Southern blot hybridization indicates that the transcript number was less than 1 per E. canis genome, i.e., not transcribed. Therefore, the lack of detection of RT-PCR products was not due to a low sensitivity of our assay or to small numbers of organisms in the specimens.

FIG. 2.

(A) Estimation of RT-PCR sensitivity in detecting transcripts of p30 paralogs. +, RT-PCR analysis was performed using decreasing amounts of in vitro-generated transcripts as templates; −, identical reactions without the addition of reverse transcriptase as a control for DNA contamination. Numbers of transcripts are shown on the top. p30 paralogs are identified on the left. Lane M, molecular size markers (φX174 replicative-form DNA HaeIII fragments). Sizes of amplified product are indicated on the right. (B) Determination and comparison of sensitivities of PCR (a) and Southern blotting (b) in detecting representative p30 paralogs. Amounts of E. canis DNA used as templates for amplification are indicated on the top. The amplified products were resolved on agarose gels containing EtBr (a). After agarose gel electrophoresis, the amplicons were transferred to nylon membranes and hybridized with a 32P-labeled probe specific for p30 (b). The membranes were exposed to Hyperfilm for 17 h at −80°C. Lane Marker, molecular size markers (φX174 replicative-form DNA HaeIII fragments). Sizes of amplified or hybridized products are indicated on the right

Transcriptional profiles of p30 paralogs in infected dogs.

Figure 3A shows the results of RT-PCR of total RNA from PBMCs from the two experimentally infected dogs over the time course of infection. The PCR products with DNA from purified E. canis as a template are shown as a positive control for the sensitivity and specificity of the gene-specific primer pairs. The RT-PCR products visualized by EtBr staining revealed a single distinct band of the expected size for every pair used. As another control, to determine the levels of ehrlichial RNA present in the PBMCs at every time point in each dog, E. canis 16S rRNA in the PBMCs was amplified by RT-PCR in the linear range with the same cDNA template. E. canis 16S rRNA levels were almost constant in both dogs during the 11- to 56-day p.i. period (Fig. 3A). Several negative controls were used in this study. Half of each total RNA preparation from dog and tick samples was processed with the same procedure but without the addition of reverse transcriptase, and PCR was carried out to rule out DNA contamination in the RNA preparation. Preinfection dog blood specimens were processed in the same manner as infected specimens and used as negative controls. Total RNA was purified, and cDNA was analyzed for the expression of p30 paralogs. None of the negative controls in the RT-PCR and Southern blotting analyses amplified or hybridized with any of the targets, 16S rRNA, or p30 paralogs of E. canis (data not shown).

Eleven out of 14 paralogs examined by RT-PCR were found to be transcribed by E. canis in PBMCs of both experimentally infected dogs. Five p30 paralogs are shown in Fig. 3A. Southern blot hybridization was used to confirm the specificity of RT-PCR products of the p30-9, -8, -10, and -2 genes due to the observation of multiple bands after RT-PCR and to augment the assay sensitivity to confirm that p30-7, -4, and -a were below the detection limit (Fig. 3B). In addition to the p30 paralogs shown in Fig. 3, two paralogs at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the locus, p30-19 and p30-20, respectively, were also analyzed by RT-PCR and found to be transcriptionally active in both dogs on day 17 p.i. (on other days p.i., expression was not determined) (data not shown). The expression of p30-2, p30-3, and p30-10 did not differ significantly between the two dogs (Fig. 3). These three paralogs were consistently expressed in both dogs at similar levels during the 56-day infection period. However, the remaining eight p30 paralogs were expressed much more strongly in the high-dosage dog, 10184, than in the low-dosage dog, 9673. Overall, mRNA expression levels increased over the time course of infection in both dogs. The expression of three paralogs, p30-7, p30-4, and p30-a, was not detected in either dog throughout the 56-day infection period. Table 1 summarizes the transcribed or undetectable mRNAs of p30 paralogs at four different time points during infection in the two dogs.

TABLE 1.

Summary of RT-PCR and Southern blotting results for dogs tested at different time points

| Days p.i. | Doga | Expression of the following p30 paralogsb:

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 4 | a | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 20 | ||

| 11 | 10184 | NP | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | NP |

| 9673 | NP | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | NP | |

| 17 | 10184 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| 9673 | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 35 | 10184 | NP | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | NP |

| 9673 | NP | + | + | − | +c | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | NP | |

| 56 | 10184 | NP | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | NP |

| 9673 | NP | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | NP | |

Dog 10184, high dosage; dog 9673, low dosage.

+, detectable level of expression; −, undetectable level of expression; NP, testing was not performed.

Extremely weak level of expression.

Tick infection and mRNA expression of p30 paralogs in infected ticks.

DNA and total RNA were extracted from 12 groups of pooled infected tick tissues (Fig. 4) and 1 uninfected tick tissue pool as a negative control. The presence of E. canis RNA in all 12 groups of infected tick tissues was confirmed by RT-PCR using 16S rRNA as the target (Fig. 4). No ehrlichial 16S rRNA or transcripts of p30 paralogs were detected in uninfected tick tissue. Without reverse transcriptase, all of these tick tissues were negative in RT-PCR using 16S rRNA or p30 paralog primers. A transcript of p30-10 was the only p30 transcript detected in all 12 groups of infected tick tissues by Southern blot hybridization, regardless of whether ticks were being acquisition or transmission fed, whether ticks were male, female, or nymphs, whether salivary glands, midguts, or body halves were used for RNA extraction, or which dog the ticks fed on. The level of p30-10 expression relative to the level of 16S rRNA expression was lower in tick tissues than in dog PBMCs.

Transcription of p30 paralogs of E. canis in DH82 cells cultured at 25°C.

Because E. canis is transferred from warm dogs to cooler ticks, temperature may be one of the factors in the transcriptional regulation of p30 paralogs. In order to test this hypothesis, we analyzed the mRNA expression of p30 paralogs of E. canis in DH82 cells cultured at 25 and 37°C. We previously showed by RT-PCR that all p30 paralogs of E. canis were transcribed at different levels in DH82 cells cultivated at 37°C (16). The infectivity levels of E. canis and cell numbers in two different culture conditions were adjusted and confirmed by RT-PCR using primers specific for the 16S rRNA gene of E. canis (Fig. 5). A comparison of the transcription of p30 paralogs in E. canis cultivated at 25 and 37°C relative to the levels of 16S rRNA transcripts showed (Fig. 5) that in a culture at 25°C, the mRNA expression level was elevated for only one gene (p30-10), whereas the remaining genes were downregulated or undetectable. This result may account for the detectable p30-10 transcript and the undetectable other transcripts in E. canis-infected ticks.

FIG. 5.

RT-PCR of p30 paralogs at 25 or 37°C. All amplicons were detected as a single band on an agarose gel stained with EtBr. Numbers on the right indicate amplicon sizes. An arrow indicates p30-10.

DISCUSSION

Various ehrlichial agents, such as E. canis, E. platys, E. phagocytophila, Cowdria ruminantium, and Anaplasma marginale, cause persistent infections in the presence of an active immune response (2, 5, 6, 20, 21); the polymorphic multigene family of major outer membrane proteins has been suspected to have a role in immune evasion in chronically infected hosts. The study of A. marginale major surface protein 2 gene (msp2) expression in cattle revealed that during each peak of rickettsemia, the expression of several msp2 genes occurs while the antibody response is directed to previously expressed msp2 genes, indicating that the mechanism of persistent infection of A. marginale in cattle may be antigenic variation (5). However, in the present study, unlike the results for A. marginale, we did not find any clear peak of rickettsemia or drastic changes in the compositions of expressed p30 paralogs of E. canis in PBMCs from dogs during the 56-day infection period. Rather, the same nine paralogs were transcriptionally active at increasing levels. Both high- and low-dosage dogs developed the same levels of antibody titers against E. canis. Despite the presence of the same levels of 16S rRNA in high- and low-dosage dogs, E. canis in the high-dosage dog showed greater overall levels of expression of these nine p30 paralogs than E. canis in the low-dosage dog. More studies are needed to clarify low- and high-dosage differences in p30 gene expression. Since the antibodies that developed did not appear to have cleared E. canis which expressed a particular set of p30 paralogs and since E. canis expressing new p30 paralogs did not emerge after the development of the antibodies, p30 gene expression by E. canis in dogs does not appear to be related to evasion of the humoral immune response.

Little is known about the localization and development of E. canis in the vector tick. However, the development of A. marginale in D. andersoni ticks is well documented (10). A. marginale and E. canis are taxonomically closely related, and their arthropod vectors are ixodid ticks that belong to the same tribe, Rhipicephalinae. It has been reported that A. marginale is acquired by D. andersoni through the blood meal and infects and multiplies in the midgut epithelium, followed by muscle cells lining the visceral side of the midgut and eventually the salivary glands, from where it is transmitted in the saliva (10, 28). Therefore, we isolated total RNA from the salivary glands, midguts, or whole bodies of R. sanguineus ticks to analyze transcription of p30 paralogs in the arthropod vector. A recent report on an analysis of the population structure of Borrelia burgdorferi in terms of outer surface protein A (OspA) and OspC and vlsE gene expression in salivary glands and midguts of Ixodes scapularis ticks (17) showed that spirochetes are a homogeneous population in ticks before the blood meal and become heterogeneous during transmission feeding. However, in the present study, only one p30 gene was expressed in E. canis in tick salivary gland, midgut, or whole-body samples of R. sanguineus adults infected as nymphs or adults after both acquisition feeding and transmission feeding.

Ten active p30 genes of E. canis in dogs became undetectable in ticks. Differential p30 expression between vectors and mammalian hosts may be important for ehrlichial tick transmission and adaptation to different hosts. Differential expression of major surface proteins of tick-borne bacteria in mammals and ticks was previously reported with A. marginale (22), B. burgdorferi (25), and B. hermsii (26). Rurangirwa et al. (22) reported that only two closely related msp2 gene products, SGV1 and SGV2, are expressed by the South Idaho strain of A. marginale in the salivary glands of adult male D. andersoni ticks during both acquisition feeding and transmission feeding on cattle. Midgut-expressed antigens were not examined. On the contrary, in the St. Maries (Idaho) strain of A. marginale, more diverse msp2 genes were expressed in tick salivary glands (23). B. burgdorferi switches from mammalian host-specific OspC to tick-specific OspA in the midguts of nymphal I. scapularis (25). A similar apparent switch occurs in variable major proteins (Vmps) during the transmission of B. hermsii. After nymphal Ornithodoros hermsii fed on BALB/c mice infected with serotype 7 or 8 B. hermsii, Vmp7 or Vmp8 was replaced by Vmp33 in the tick salivary glands; this pattern was reversed after tick transmission of B. hermsii back to mice (26). Even though p30-10 was expressed by E. canis in ticks, the levels of expression were lower than those of E. canis in canine PBMCs relative to the 16S rRNA expression levels. Therefore, it does not seem that p30-10 is upregulated in ticks; rather, overall p30 paralogs appear to be downregulated in E. canis in ticks while p30-10 continues to be expressed.

16S rRNA was used to normalize the input RNA in the current study. No adustment was necessary, since the levels of 16S rRNA actually did not change much in dogs and tick tissues once infection was established. Since 16S rRNA is involved in protein synthesis and is relatively stable under stress in Ehrlichia spp. (32), it is expected to reflect the growth of ehrlichiae in general. Not many other genes are known to be used as alternative “housekeeping genes” for Ehrlichia spp. at this time. DNA is not an appropriate housekeeping gene, since it is purified by a different procedure and thus cannot be used as an RNA recovery and RT reaction control. We assume that RT-PCR detected mRNA and rRNA primarily from live ehrlichiae in this study, since once ehrlichiae are killed, whole bacteria are rapidly degradated in lysosomes (18, 30). However, if 16S rRNA persists much longer than mRNA of p30 paralogs in dead bacteria, then a more dynamic pattern of gene expression may be masked.

Fourteen p30 paralogs at the 5′ end of the 28-kb locus of E. canis were linked by short intergenic spaces, while the 8 remaining paralogs at the 3′ end were connected by longer intergenic spaces (16). The active or silent state of p30 paralogs may be related to their structure and localization. p30-10, the only p30 paralog expressed in ticks, is localized downstream of the first group, after the longest intergenic space (550 bp), and this gene product has the most acidic pI value, 4.2, among the P30s. These characteristics could explain why p30-10 continues to be expressed in ticks.

All 22 p30 paralogs were transcriptionally active in the DH82 monocyte cell line, and the paralogs with short intergenic spaces were cotranscribed with their adjacent genes, including respective intergenic spaces, at both 5′ and 3′ ends (16). Three p30 paralogs, including, p30-7 in the polycistronic region, were undetectable in monocytes from both dogs, suggesting that transcriptional regulation in canine PBMCs differs from that in the DH82 dog cell culture system. In the present study, we compared the transcription of p30 paralogs in E. canis cultivated at 37 and 25°C to serve as a temperature model for dog and tick infections, respectively. Downregulation of the p30 paralogs, except for p30-10, in ticks as well as in DH82 cells grown at 25°C suggests that temperature may be one of the factors regulating the mRNA expression of p30 paralogs. Whether pathogenicity is different between E. canis expressing only p30-10 and E. canis expressing multiple p30 paralogs remains to be determined. Analysis of expression profiles for p30 paralogs in dogs and ticks under different conditions will facilitate understanding of the role of the p30 multigene family in the pathogenesis of CME and the tick transmission of E. canis. Future studies on the regulation of p30 gene expression and genes abundantly expressed in ticks could lead to the development of a vaccine against CME.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants R01AI40934 and R01AI47407 from the National Institutes of Health. A. Unver is the recipient of a scholarship from the National Ministry of Education in Turkey. T. Tajima is the recipient of a scholarship from the Japanese Ministry of Education.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson B E, Dawson J E, Jones D C, Wilson K H. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2838–2842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2838-2842.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buhles W C, Huxsoll D L, Ristic M. Tropical canine pancytopenia: clinical, haematologic, and serologic, and serologic response of dogs to Ehrlichia canis infection, tetracycline therapy, and challenge inoculation. J Infect Dis. 1974;130:358–367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Codner E C, Farris-Smith L L. Characterization of the subclinical phase of ehrlichiosis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;189:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donatein A, Lestoquard F. Existence and algerie d'une rickettsia du chien. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1935;28:418–419. [Google Scholar]

- 5.French D M, McElwain T F, McGuire T C, palmer G H. Expression of Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 2 variants during persistent cyclic rickettsemia. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1200–1207. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1200-1207.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene C E, Harvey J W. Canine ehrlichiosis. In: Greene C E, editor. Clinical microbiology and infectious diseases of dog and cat. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1990. pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groves M G, Dennis G L, Amyx H L, Huxsoll D L. Transmission of Ehrlichia canis to dogs by ticks (Rhiphicephalus sanguineus) Am J Vet Res. 1975;36:937–940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iqbal Z, Chaichanasiriwithaya W, Rikihisa Y. Comparison of PCR and Western immunoblot analysis in early diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1658–1662. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1658-1662.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson E M, Ewing S A, Barker R W, Fox J C, Crow D W, Kocan K M. Experimental transmission of Ehrlichia canis (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) by Dermacentor variabilis (Acari: Ixodidae) Vet Parasitol. 1998;74:277–288. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kocan K M, Stich R W, Claypool P L, Ewing S A, Hair J A, Barron S J. Intermediate site of development of Anaplasma marginale in feeding adult Dermacentor andersoni ticks that were infected as nymphs. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehn N F, Gaunt S D. Clinical and hematologic findings in canine ehrlichiosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;186:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis G E, Ristic M, Smith R D, Lincoln T, Stephenson E H. The brown dog tick Rhiphicephalus sanguineus and the dog as experimental hosts of Ehrlichia canis. Am J Vet Res. 1977;38:1953–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathew J S, Ewing S A, Barker R W, Fox J C, Dawson J E, Warner C K, Murphy G L, Kocan K M. Attempted transmission of Ehrlichia canis by Rhiphicephalus sanguineus after passage in cell culture. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:1594–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohashi N, Zhi N, Zhang Y, Rikihisa Y. Immunodominant major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:132–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.132-139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohashi N, Unver A, Zhi N, Rikihisa Y. Cloning and characterization of multigenes encoding the immunodominant 30-kilodalton major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia canis and application of the recombinant protein for serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2671–2680. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2671-2680.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y, Unver A. Analysis of transcriptionally active gene clusters of major outer membrane protein multigene family in Ehrlichia canis and E. chaffeensis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2083–2091. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2083-2091.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnishi J, Piesman J, de Silva A M. Antigenic and genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi populations transmitted by ticks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:670–675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J, Rikihisa Y. l-Arginine-dependent killing of intracellular Ehrlichia risticii by macrophages treated with gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3504–3508. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3504-3508.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick C D, Hair J A. Laboratory rearing procedures and equipment for multi-host ticks (Acarina:Ixodidae) J Med Entomol. 1975;12:389–390. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/12.3.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rikihisa Y. The tribe Ehrlichiae and ehrlichial diseases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:286–308. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fox J C. Western blot analysis of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. canis, or E. ewingii infections in dogs and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2107–2112. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2107-2112.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rurangirwa F R, Stiller D, French D M, Palmer G H. Restriction of major surface protein 2 (MSP2) variants during tick transmission of the ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3171–3176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rurangirwa F R, Stiller D, Palmer G H. Strain diversity in major surface protein 2 expression during tick transmission of Anaplasma marginale. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3023–3027. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.3023-3027.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwan T G, Piesman J, Golde W T, Dolan M C, Rosa P A. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2909–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwan T G, Hinnebusch B J. Bloodstream- versus tick-associated variants of a relapsing fever bacterium. Science. 1998;280:1938–1940. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw E I, Dooley C A, Fischer E R, Scidmore M A, Fields K A, Hackstadt T. Three temporal classes of gene expression during the Chlamydia trachomatis developmental cycle. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:913–925. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stich R W, Sauer J R, Bantle J A, Kocan K M. Detection of Anaplasma marginale (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in secretagogue-induced oral secretions of Dermacentor andersoni (Acari: Ixodidae) with the polymerase chain reaction. J Med Entomol. 1993;30:789–794. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/30.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unver A, Rikihisa Y, Ohashi N, Cullman L C, Buller R, Storch G A. Western and dot blotting analysis of Ehrlichia chaffeensis indirect fluorescent-antibody assay-positive and -negative human sera by using native and recombinant E. chaffeensis and E. canis antigens. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3888–3895. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.3888-3895.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells M Y, Rikihisa Y. Lack of lysosomal fusion with phagosomes containing Ehrlichia risticii in P388D1 cells: abrogation of inhibition with oxytetracycline. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3209–3215. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3209-3215.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wen B, Rikihisa Y, Mott J M, Greene R, Kim H Y, Zhi N, Couto G C, Unver A, Bartsch R. Comparison of nested PCR with immunofluorescent-antibody assay for detection of Ehrlichia canis infection in dogs treated with doxycycline. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1852–1855. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1852-1855.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Ohashi N, Rikihisa Y. Cloning of the heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) gene of Ehrlichia sennetsu and differential expression of HSP70 and HSP60 mRNA after temperature upshift. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3106–3112. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3106-3112.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]