Abstract

Sterubin, a flavanone is an active chemical compound that possesses neuroprotective activity. The current investigation was intended to assess the sterubin effect in scopolamine-activated Alzheimer's disease. The rats were induced with scopolamine (1.5 mg/kg) followed by treatment with sterubin (10 mg/kg) for 14 days. Behavioural analysis was predictable by the Y-maze test and Morris water test. Biochemical variables like nitric oxide acetylcholinesterase, Choline acetyltransferase, antioxidant markers like superoxide dismutase, glutathione transferase, malondialdehyde, catalase, and myeloperoxidase activity, neuroinflammatory markers such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, nuclear factor kappa B, interferon-gamma, interleukin (IL-1β), and IL-6 were measured. The result stated that sterubin reversed the oxidative stress parameters, increased motor performance, and lowered the inflammatory markers in scopolamine-induced rats. The study demonstrated that sterubin possesses neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties which can be used as a beneficial medication in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Neuroprotective, Neuroinflammatory markers, Oxidative stress, Scopolamine, Sterubin

Abbreviations: Alzheimer’s disease, AD; Scopolamine, SCOP; reactive oxygen species, ROS; interleukin, IL; acetylcholinesterase, ACh; interferon, IFN; tumor necrosis factor, TNF; Morris water maze, MWM; Acetylcholinesterase, AChE; Choline acetyltransferase, ChAT; Reduced glutathione, GSH; Catalase, CAT; Myeloperoxidase, MPO

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an advanced neurological brain condition that harms cognitive brain functions including coordination, impression, logistics, and opinion (Raskin et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2020). About 40 million population are affected by AD globally and estimated rates will rise to 120 million by 2050 (Brookmeyer et al., 2007). The underlying pathogenetic features of AD include fragments of amyloid protein and the intertwining of tau protein in the neurons and cerebral cortex (Penke et al., 2020). The beta amyloids prevent synaptic neuronal communication while the tau proteins intervene in the passage of essential nutrients to the neurons causing neuronal loss (Huang and Jiang, 2009, Ali et al., 2015). Memory loss is linked with the cholinergic system which involves dysfunction in the neurons, receptors, and neurotransmitters affecting the hippocampus and forebrain (Drever et al., 2011). The beta amyloids also increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) including lipid peroxidation which causes oxidative injury resulting in loss of hippocampal tissue plasticity (Walsh and Selkoe, 2004, Sharma et al., 2016).

Scopolamine (SCOP), an alkaloid is a widely used animal model for studying dementia-related disorders. Generally, SCOP antagonizes the memory involved in muscarinic acetylcholine receptors due to its structural resemblance, eventually slowing down cognitive abilities leading to cause AD-like symptoms (Pezze et al., 2017). Several neurobehavioral findings in rodents were studied by using SCOP to induce learning and memory deficits (Klinkenberg and Blokland 2010). SCOP when injected intraperitoneally elevated the ROS by altering the antioxidant enzymes, causing accumulation of amyloid plaques, suppressing the trophic factors, and increased neuroinflammation resulting in atrophy and degeneration of neurons (Bloom, Arce-Varas et al., 2017). SCOP has a direct effect on brain in acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity (Vickers 2017). The current pharmacological therapies include AchE inhibitors namely donepezil and rivastigmine that focus on a single factor i.e., reduce the AChE enzyme levels (Schelterns and Feldman, 2003, Ghumatkar et al., 2015). However, AD is a multifactorial condition involving various factors which should be considered while selecting a drug. Several plants and their phytoconstituents are known to be natural antioxidants that work multi-functionally by reducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction thereby improving neuronal functions (Chen and Decker, 2013, Samodien et al., 2019).

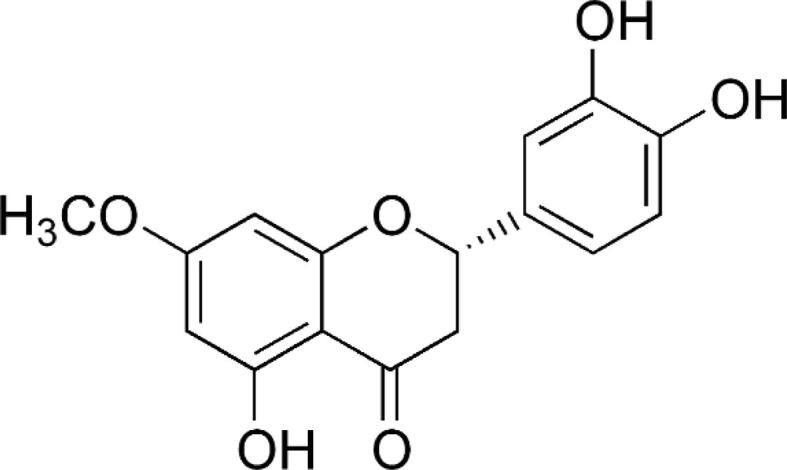

Sterubin, a flavanone is obtained from Eriodictyon californicum belongs to Boraginaceae family. Sterubin is an analogue of eriodictyol having an O-methyl group attached to the ring which increases the penetrability through the tissues (Fischer et al., 2019). Sterubin, the main active component has been evidenced to be neuroprotective against toxicities of the brain, mainly in AD (Fischer et al., 2019). Sterubin is a good candidate for AD when studied in-vitro and in vivo study in a mouse model of AD (Hofmann et al., 2020a, Hofmann et al., 2020b) but pharmacological action on SCOP-induced AD paradigm has not been studied yet. So, the research aims to assess the neuroprotective effects by estimating behavioural, and biochemical aspects of terubin in the SCOP-activated AD paradigm in Wistar rats.

2. Methodology

2.1. Chemicals

SCOP, biochemical analysis kits for nuclear factor kappa (NF-ƘB), interleukin (IL-6), IL-1β, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF-α) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Sterubin (Fig. 1) was purchased from SK Lab, Maharashtra, India (Ref-01–001883; World Chemical Supplier, India). The experiment was performed using standard reagents and chemicals.

Fig. 1.

Structure of sterubin.

2.2. Animals

Male Wistar rats (200 ± 20 g) were housed in propylene cages. As standard conditions, the rats were caged on 23°Celsius, with 50–70 % humidity, a 12:12hr light–dark cycle, and free water and pellets. Following the guidelines of the CPCSEA, the research was permitted by the official ethical committee for the animal (IAEC/TRS/PT/021/005).

2.3. Experimental

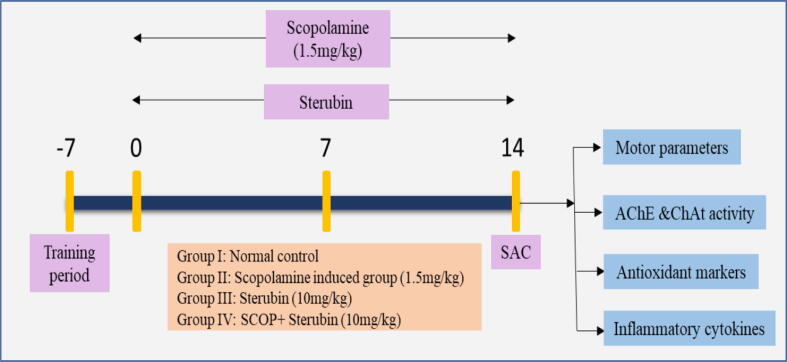

Total of 24 rats were randomized into four clusters after acclimatization for a week to laboratory conditions.

Cluster I: Control (saline)

Cluster II: SCOP (1.5 mg/kg)

Cluster III: Received only sterubin (10 mg/kg) perse

Cluster IV: SCOP + sterubin (10 mg/kg)

Cluster I received normal saline and disease cluster II was intraperitoneally injected daily by SCOP (1.5 mg/kg) was administered (Fig. 2). The third cluster rats was administered with sterubin alone and the last cluster was induced with SCOP and then given sterubin (10 mg/kg) for 14 days (Bejar et al., 1999, Hoang et al., 2020).

Fig. 2.

Experimental protocol. SAC- Sacrifice, AChE- Acetylcholinesterase, ChAt- Choline acetyltransferase, SCOP- Scopolamine.

2.4. Acute toxicological study

Acute toxicity study was performed based on OECD guideline no. 423. The rats were assessed for signs of toxicity throughout the next 14 days. Sterubin was given orally in accordance with the previously published safe dose (Hofmann et al., 2020a, Hofmann et al., 2020b). Clinical symptoms like behavioural alterations, changes in the eyes, body weight, skin and fur were noted (Schlede, 2002, Afzal et al., 2022).

2.5. Behavioural functional tests

2.5.1. Y-maze test

The test was assessing latitudinal memory which consists of a three-armed maze (40 cm H, 4 cm W). The floor and walls facing each other were made up of polyvinyl plastic. The rats were placed in one of the arms and their movement was recorded for 8–10 mins. The alternation into the different arms i.e., the number of entries was calculated once all forepaws are on the floor. The maze walls and the floor were cleaned properly after each animal trial. (Mamiya and Ukai, 2001, Souza et al., 2010, Zaki et al., 2014).

2.5.2. Morris water maze (MWM) test

The experiment was based on assessing remembrance and spatial learning by placing a hidden floor. The objective of the test was to orient the animal and memorize the position of the platform. The MWM round tank was divided into four equally spaced quadrants. Escape platform for retains 2 cm below any one quadrant for 5 days. During the learning activity, one animal was placed in a randomly selected position in the tank (four trials per event). Animals were brought further into the tank to begin the experiment. The animal found the platform and stepped out, the experiment ended, and mean escape latency was calculated. A maximum exposure time of 60 s was recorded. After 60 s of pushing, if the animal failed to reach the platform, another 60 s of escape latency was observed. After each session, the animal remained on the stand for 20 s. Each time the test was conducted, the animals were gently cleaned and placed in cages. The last trial (exploration) was executed without placing the platform. The animals which did not find the platform were guided toward the submerged base. The latency time is the interval used by each rat to treasure the concealed base was prominent (Kwon et al., 2010, Jang et al., 2013).

2.6. Antioxidant enzymes

2.6.1. Dissection and homogenization

After behavioural assessments, on the 15th day, animals were revealed to biochemical analysis and analysis of proinflammatory markers. The brains of the animals were isolated, cut transversely into thin sections and centrifuged for 15 mins in phosphate buffer at 2000–3000 rpm. For enzymatic evaluation the supernatant was segregated and refrigerated at 4˚C in formalin solution.

2.6.2. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)

Determination of AChE was conducted via using following process detailed by Ellman et al (1961). 0.5 ml of supernatant, 0.10 ml acetylthiocholine iodide, 0.10 ml Ellman’s reagent and 3 ml phosphate buffer (0.01 mol/l) were mixed to the reaction tube. Spectrometrically the absorbance was determined at 412 nm (Gutierres et al., 2014). AChE activity was measured in nmol/mg protein and calculated by the given formula:

Where, δOD = Change in absorbance, R = rate of enzyme activity, E = Extinction coefficient i.e., 13600/M/cm.

2.6.3. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) estimation

In order to determine ChAT activity, 5 % tissue homogenates were prepared in ice-cold 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) and kept frozen at −20 °C overnight. They were thawed on the following day and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. Using the method of Chao and Wolfgram (1972), the supernatant was tested for ChAT activity (Chao and Wolfgram 1972). Preincubation of the reaction mixtures (0.4 ml) in centrifuge tubes containing 25 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 0.31 mM acetyl-CoA, 50 mM choline chloride, and 38 mM neostigmine sulfate was conducted for 5 min at 37 °C. In addition to the homogenate, 100 µl of the reaction mixture were added to the tubes and kept at 37 °C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by boiling for 2 min, and 1 ml of distilled water was added to the tubes. From the centrifugation, denatured protein was removed. One milliliter of supernatant was added to a tube containing 30 μl of 1 mM 4,4′-dithiopyridine. After a 15-min incubation, the absorbance was measured at 324 nm with a spectrophotometer. ChAT activity was accessed in Units/ gram of tissue protein.

The SOD method was performed according to Kono et.al. The main concept of this test is based on inhibiting the lessening of nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) by superoxide dismutase. The reaction mixture contains brain homogenate or supernatant and NBT to which hydroxylamine hydrochloride was added. Spectrometrically the mixture was recorded at 560 nm. SOD activity was accessed in Units/ milligram of tissue protein (Nandi and Chatterjee, 1988, Bihaqi et al., 2011).

2.6.4. Estimation of lipid peroxidation

The mixture contains 0.5 ml homogenate which was incubated for 10mins. To that, 15 % trichloroacetic acid (TCA), thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and HCL (5 N) and were mixed and blend was incubated at 90˚C for 20 mins. Tubes were cooled and centrifugated at 2000 rpm for 15 mins. The absorbance was estimated spectrophotometrically at 512 nm. The activity was represented as nM/mg tissue of wet tissue (Öztürk-Ürek et al., 2001, Jain et al., 2015, Bhuvanendran et al., 2018).

2.6.5. Reduced glutathione (GSH) estimation

The reaction mixture consists of 0.5 ml supernatant and 0.25 M sodium phosphate buffer maintained at 7.4 pH. To this, 0.04 % 5,5′-dithio-bis-[2-nitrobenzioc acid]) (DTNB) solution was added. At 412 nm, spectrophotometric measurements were performed to determine the absorbance of the blend. It was dignified in nmg GSH/g tissue (Owens and Belcher, 1965, Rajashri et al., 2020, Ajayi et al., 2021).

2.6.6. Catalase (CAT) estimation

The CAT estimation was defined as the rate of H2O2 decomposition into water and molecular oxygen. This method includes 10 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7), to which supernatant was added. The absorbance was measured at 240 nm for at least 2 mins. The activity was measured in units of CAT / wet gm of tissue (Hadwan 2016).

2.6.7. Nitric oxide assessment

The colorimetric analysis procedure given by Green et al (1982) was performed for the determination of nitric oxide in the brain tissues. This mixture includes an equal proportion of Griess reagent (Naphthyl ethylene diamine and sulphanilamide in H3PO4) and brain homogenate. After incubating for 15 mins, the absorbance change was recorded spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. The agglomeration was estimated by calibration curve and measured by nmol/mg protein (Ishola et al., 2019).

2.6.8. Myeloperoxidase activity (MPO) estimation

The mixture contains cold potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM), 0.5 % hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (HETAB) and l0 mM Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The mixture was subjugated to cycles of icing and defrosting, sonicated for 15 sec. The mixture was centrifugated at 20000 × g for 20mins. The activity was estimated at 460 nm spectrophotometrically. The MPO activity was presented by U/mg tissue (Aykac et al., 2019, San Tang, 2019).

2.7. Neuroinflammatory parameters

Quantifications of cytokines namely as nuclear factor-κB (NF-ƙB), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and IFN-γ were assessed by commercial immunoassay (ELISA) kits by following the manufacturer’s procedure. Monoclonal antibodies were pre-coated onto the wells of the microtiter plates. Samples were added to microtiter wells, washed, antibody was added and incubated. The absorbance was estimated and reported as pg/mg of protein.

2.8. Statistical investigation

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc test used for biochemical variables, except for the Morris water test by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni's post hoc test. Data presented as mean ± SEM using GraphPad Prism software version 8.0. P < 0.05 was considered as the significance of the data.

3. Results

3.1. Acute toxicity

No mortality or other abnormalities were seen during acute toxicity period. On the basis of acute toxicity study, we conducted the experiment with 10 mg/kg of sterubin (Table 1).

Table 1.

Behavioral observations after treatment with an oral dose of sterubin in acute oral toxicity study.

| Observations | Acute toxicity |

|---|---|

| Skin and Fur | Normal |

| Eyes | Normal |

| Respiration | Normal |

| Somatomotor activity | Normal |

| Tremors | Not seen |

| Convulsions | Not seen |

| Salivation | Not seen |

| Diarrhea | Not seen |

| Lethargy | Not seen |

| Sleep | Normal |

| Coma | Not seen |

| Mortality | Not seen |

3.2. Behavioural parameters

3.2.1. Morris water test

During training days, a sharp decline in escape latency was noticed in all the clusters. SCOP-treated cluster took a longer (p < 0.001) emission expectancy period from the 2-day as associated to controls. From day 2, sterubin-treated cluster lowered the duration of emission expectancy in contrast with SCOP-induced cluster (Fig. 3A). Two-way ANOVA showed that SCOP-treated rats less time was spent in the target quadrant in comparison to the control rats and sterubin enhanced time to spent in the target quadrant in comparison to SCOP-treated rats (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). No significant changes in the sterubin per se group.

Fig. 3.

Effect of sterubin on behavioural activity by using Y-maze test and Morris water maze (MWM) test. A. Escape latency, B. Time spent in target quadrant C. % Spontaneous alterations, D. Total arm entries, All values are presented as mean ± SEM. Correlation among the groups Y-maze test was done using one- way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test and Morris water test done using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. P value < 0.05, 0.001 were expressed as *, *** respectively # Significant as correlated to control group (P < 0.001).

3.2.2. Y-maze test

Y-maze experiment was executed to monitor the associative learning function in SCOP rats. The SCOP cluster showed a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in % spontaneous alteration and total entries as correlated to the control group. In the sterubin + SCOP cluster showed a substantial rise (P < 0.05) in the percentage of spontaneous alteration and total arm entries when associated to the SCOP-induced group (Fig. 3 C-D). No significant changes in the sterubin alone group.

3.3. Biochemical estimation

3.3.1. AChE and ChAT

The diseased cluster showed a noticeable hike (P < 0.001) in the AChE level correlated with the control. SCOP + sterubin showed a marked decline (P < 0.01) correspondingly in AChE level as collated with the disease control cluster indicating a reduction in acetylcholine (Fig. 4A). No significant changes were observed in the sterubin alone group.

Fig. 4.

Effect of sterubin on A. AChE and B. ChAT activity, All values are presented as mean ± SEM. Correlation among the groups was done using Tukey’s post hoc test by one- way ANOVA. P value < 0.05, 0.01 was expressed as *, ** respectively, # Significant as correlated to control group (P < 0.001).

ChAT level was reduced (P < 0.001) in SCOP- treated animals when correlated with the normal control groups. While SCOP + sterubin was significantly elevated (P < 0.01) the ChAT level in comparison with the SCOP cluster (Fig. 4B). No significant changes in the sterubin alone group.

3.4. Antioxidant parameters

The level of MDA and MPO in the SCOP cluster significantly elevates (P < 0.001) once correlated with normal control cluster. SCOP + sterubin (P < 0.05; P < 0.01) markedly lessened the lipid peroxidation (MDA) and MPO level as correlated to the SCOP group. A significant reduction (P < 0.001) in GSH, SOD, and CAT were experiential in the SCOP cluster when compared with the control cluster. SCOP + sterubin were significantly increased (P < 0.05) in the GSH, SOD, and CAT as compared to the SCOP-treated group (Fig. 5A-E). No significant changes in the sterubin per se group.

Fig. 5.

Effect of sterubin on antioxidant enzyme activities. A. GSH, B. MDA, C. Catalase, D. SOD, E. MPO, All values are presented as mean ± SEM. Correlation among the groups was done using Tukey’s post hoc test by one- way ANOVA. P value < 0.05, 0.001 were expressed as *, ** respectively, # Significant as correlated to control group (P < 0.001).

3.5. Nitrite assay

The SCOP cluster displayed a marked increase in the nitrite level as compared to the controls. While SCOP + sterubin restored (p < 0.05) nitric oxide level as correlated to the SCOP treated cluster (Fig. 6). No significant changes in the sterubin per se group.

Fig. 6.

Effect of sterubin on nitric oxide level. All values are presented as mean ± SEM. Correlation among the groups was done using Tukey’s post hoc test by one- way ANOVA. P value < 0.05 were expressed as * # Significant as correlated to control group (P < 0.001).

3.6. Neuroinflammatory markers

The proportion of neuroinflammatory markers (TNF-α, IFN-γ, NF-ƙB, IL-6, IL-1β) in the SCOP cluster elevated (P < 0.001) significantly as collated to the controls. While SCOP + sterubin exhibited a noticeable decrease in the IL-6 (P < 0.05), IL-1β (P < 0.01), TNF-α (P < 0.05), IFN-γ (P < 0.01), and NF-ƙB (P < 0.05) when correlated to the SCOP treated group (Fig. 7 A-E). Sterubin 10 mg/kg alone group shows no significant changes.

Fig. 7.

Effect of sterubin on neuroinflammatory cytokine levels. A. IL-1β, B. IL-6, C. IFN-γ, D. NF-ƘB, E. TNF-α, All values are presented as mean ± SEM. Correlation among the groups was done using Tukey’s post hoc test by one- way ANOVA., P value < 0.05, 0.01 were expressed as *, ** respectively # Significant as correlated to control group (P < 0.001).

4. Discussion

AD inflicts neurobehavioral dysfunction causing damage to the brain neurons. Though its pathology is unclear, AD is known to be related to risk factors including oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and damage to the cholinergic neurons (Canter et al., 2016). The current treatment primarily focuses on improving cholinergic neurons or impeding NMDA receptors and refinement of symptoms (Verma and Singh 2020). SCOP-activated rats resulted in spatial memory impairments, cholinergic dysfunction, and oxidative damage which are the major reasons of AD. In this study, we assessed the behavioural, biochemical, and neuroinflammatory alterations caused by SCOP and favourable effects of sterubin.

In the present investigation, sterubin was carried out to evaluate the toxicity study in animals. We found that sterubin was safe and no mortality or clinical signs of toxicity were observed in rats (Hofmann et al., 2020a, Hofmann et al., 2020b).

We assessed the behavioural performance by performing motor functional tests. The deprivation of cholinergic neurons leads to memory and functional deficiency. The Y-maze activity was measured by monitoring the entry of rats in the arms and working memory (Mamiya and Ukai 2001). Through the outcomes, a noticeable decrease in impulsive variation activity was recognized in the SCOP-induced cluster compare to the controls which presented behavioural toxicity, the same as earlier reported (Foyet et al., 2015, Imam et al., 2016, Ionita et al., 2018). In the Y-maze behavioral task, the SCOP-treated groups showed the lowest levels of locomotion in terms of the percentage of spontaneous alternations and total arm entries when compared to the control group. When treated with sterubin (cluster IV), the percentage spontaneous alterations were increased remarkably by enhancing the cognitive functions. The reminiscence functions can also be evaluated by performing the Morris water maze test. The study data indicated that the SCOP-induced cluster delayed the time to latency, decreased the crossing time on the platform, and lessened the time taken by rats in each quadrant which was in line with the previous studies (Goverdhan et al., 2012, Saba et al., 2017, Lee et al., 2018). The rats orient in the same direction interpret that rats have memorized the path to the platform. The results showed that SCOP caused cognitive decline while sterubin reversed SCOP-induced motor deficits by increasing the total arms entries in the Morris water test, thereby enhancing learning ability. However, sterubin decline the time to find the hidden platform significantly and also, improved the time spent in the target quadrant in SCOP-treated rats.

AChE enzyme halts the effect of acetylcholine on the synapse, which inhibits cholinergic transmission (Giacobini 2004). Acetylcholine is transported in large amounts throughout the brain which is crucial for the efficient functioning of the nervous system. SCOP was found to increase the AChE and decrease the ChAT level which will affect the Ach levels as earlier reported (Sharma et al., 2010, Goverdhan et al., 2012, Sun et al., 2019). These results showed a marked decline in AChE and ChAT activity when treated by sterubin, thereby regulating the cholinergic system.

The brain consumes the highest amount of oxygen which is a cause of oxidative damage resulting in increased lipid peroxidation and decline in other antioxidant markers. The increased lipid peroxidation generates metabolites such as MDA which initiates oxidative damage by targeting the cell membrane permeability. Like previous studies, SCOP induces oxidative stress in rats by altering the antioxidant defense system (Hritcu et al., 2015, Mostafa et al., 2021). Our study results indicate that treatment with sterubin significantly restored the antioxidant level in SCOP-induced oxidative injury by lowering the tissue peroxidation and nitric oxide levels along with the rise in SOD, GSH, and CAT activities.

Neuronal damage is caused due to dysfunction of inflammatory cytokines, preceding the advancement of AD. Excessive cytokine release is linked to the activation of microglial cells aggravating symptoms of AD (Alam et al., 2016). In accordance with previous reports, SCOP administration in rats significantly elevated the neuroinflammatory markers leading to neuronal injury (El-Marasy et al., 2012, Steinfeld et al., 2015, Abdel-Latif et al., 2019). In the present study, sterubin displayed a noticeable decline in cerebral inflammatory markers in SCOP-induced rats. The results shown that sterubin regulating the behavioural parameters, suppressing neuroinflammatory pathway, as well as neuroinflammatory markers and improving cholinergic function in the brain. Study limitations include the short duration and the use of a small number of animals.

5. Conclusion

The results conclude that sterubin might be an effective treatment option for Alzheimer’s disease. Sterubin improved behaviuoral activity, altered oxidative stress, lowered down neuroinflammatory markers in SCOP-induced rats. The study was limited to low dose range groups of sterubin. Further studies will be required to determine the mechanism of action of sterubin using immunohistochemistry and molecular mechanism.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (G: 116-130-1442). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Author Contributions Statement

I,K. designed, performed study and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; F.A.A.-.A., M.A., M.S.N. H..N.A, critically revised manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Imran Kazmi, Email: ikazmi@kau.edu.

Fahad A. Al-Abbasi, Email: fabbasi@kau.edu.sa.

Muhammad Afzal, Email: afzalgufran@gmail.com.

Muhammad Shahid Nadeem, Email: mhalim@kau.edu.sa.

Hisham N. Altayb, Email: hdemmahom@kau.edu.sa.

References

- Abdel-Latif M.S., Abady M., Saleh S.R., et al. Effect of berberine and ipriflavone mixture against scopolamine-induced alzheimer-like disease. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Phytopharmacological Research (eIJPPR). 2019;9:48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal M., Alzarea S.I., Alharbi K.S., et al. Rosiridin Attenuates Scopolamine-Induced Cognitive Impairments in Rats via Inhibition of Oxidative and Nitrative Stress Leaded Caspase-3/9 and TNF-α Signaling Pathways. Molecules. 2022;27:5888. doi: 10.3390/molecules27185888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi A.M., Ben-Azu B., Godson J.C., et al. Effect of Spondias Mombin fruit extract on scopolamine-induced memory impairment and oxidative stress in mice brain. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2021;27:24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Alam Q., Zubair Alam M., Mushtaq G., et al. Inflammatory process in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's diseases: central role of cytokines. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016;22:541–548. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666151125000300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali T., Yoon G.H., Shah S.A., et al. Osmotin attenuates amyloid beta-induced memory impairment, tau phosphorylation and neurodegeneration in the mouse hippocampus. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–17. doi: 10.1038/srep11708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arce-Varas N., Abate G., Prandelli C., et al. Comparison of extracellular and intracellular blood compartments highlights redox alterations in Alzheimer's and mild cognitive impairment patients. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017;14:112–122. doi: 10.2174/1567205013666161010125413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aykac A., Ozbeyli D., Uncu M., et al. Evaluation of the protective effect of Myrtus communis in scopolamine-induced Alzheimer model through cholinergic receptors. Gene. 2019;689:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar C., Wang R.-H., Weinstock M. Effect of rivastigmine on scopolamine-induced memory impairment in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;383:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuvanendran S., Kumari Y., Othman I., et al. Amelioration of cognitive deficit by embelin in a scopolamine-induced Alzheimer’s disease-like condition in a rat model. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:665. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihaqi S.W., Singh A.P., Tiwari M. In vivo investigation of the neuroprotective property of Convolvulus pluricaulis in scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in Wistar rats. Indian journal of pharmacology. 2011;43:520. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.84958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R., Johnson E., Ziegler-Grahamm K., et al. O1–02–01: Forecasting the global prevalence and burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:S168–S. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canter R.G., Penney J., Tsai L.-H. The road to restoring neural circuits for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016;539:187–196. doi: 10.1038/nature20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao L.-P., Wolfgram F. Spectrophotometric assay for choline acetyltransferase. Anal. Biochem. 1972;46:114–118. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Decker M. Multi-target compounds acting in the central nervous system designed from natural products. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:1673–1685. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320130007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drever B.D., Riedel G., Platt B. The cholinergic system and hippocampal plasticity. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;221:505–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Marasy S.A., El-Shenawy S.M., El-Khatib A.S., et al. Effect of Nigella sativa and wheat germ oils on scopolamine-induced memory impairment in rats. Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University. 2012;50:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W., Currais A., Liang Z., et al. Old age-associated phenotypic screening for Alzheimer's disease drug candidates identifies sterubin as a potent neuroprotective compound from Yerba santa. Redox Biol. 2019;21 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2018.101089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyet H.S., Ngatanko Abaïssou H.H., Wado E., et al. Emilia coccinae (SIMS) G Extract improves memory impairment, cholinergic dysfunction, and oxidative stress damage in scopolamine-treated rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0864-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghumatkar P.J., Patil S.P., Jain P.D., et al. Nootropic, neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects of phloretin in scopolamine induced amnesia in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2015;135:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini E. Cholinesterase inhibitors: new roles and therapeutic alternatives. Pharmacol. Res. 2004;50:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goverdhan, P., A. Sravanthi and T. Mamatha, 2012. Neuroprotective effects of meloxicam and selegiline in scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment and oxidative stress. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gutierres J.M., Carvalho F.B., Schetinger M.R.C., et al. Neuroprotective effect of anthocyanins on acetylcholinesterase activity and attenuation of scopolamine-induced amnesia in rats. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2014;33:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadwan M.H. New method for assessment of serum catalase activity. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016;9:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang T.H.X., Ho D.V., Van Phan K., et al. Effects of Hippeastrum reticulatum on memory, spatial learning and object recognition in a scopolamine-induced animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharm. Biol. 2020;58:1107–1113. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2020.1841810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann J., Fayez S., Scheiner M., et al. Sterubin: Enantioresolution and Configurational Stability, Enantiomeric Purity in Nature, and Neuroprotective Activity in Vitro and in Vivo. Chemistry – A. European Journal. 2020;26:7299–7308. doi: 10.1002/chem.202001264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann J., Fayez S., Scheiner M., et al. Sterubin: Enantioresolution and Configurational Stability, Enantiomeric Purity in Nature, and Neuroprotective Activity in Vitro and in Vivo. Chemistry (Weinheim an der Bergstrasse, Germany). 2020;26:7299–7308. doi: 10.1002/chem.202001264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hritcu L., Bagci E., Aydin E., et al. Antiamnesic and antioxidants effects of Ferulago angulata essential oil against scopolamine-induced memory impairment in laboratory rats. Neurochem. Res. 2015;40:1799–1809. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1662-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H. and Z. Jiang, 2009. Accumulated amyloid-β peptide and hyperphosphorylated tau protein: Relationship and links in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer Dis. 16, 15–27. doi: 10.3233. JAD. 960, [DOI] [PubMed]

- Imam A., Ajao M., Ajibola M., et al. Black seed oil ameliorated scopolamine-induced memory dysfunction and cortico-hippocampal neural alterations in male Wistar rats. Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University. 2016;54:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ionita R., Postu P.A., Mihasan M., et al. Ameliorative effects of Matricaria chamomilla L. hydroalcoholic extract on scopolamine-induced memory impairment in rats: A behavioral and molecular study. Phytomedicine. 2018;47:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2018.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishola I.O., Osele M.O., Chijioke M.C., et al. Isorhamnetin enhanced cortico-hippocampal learning and memory capability in mice with scopolamine-induced amnesia: role of antioxidant defense, cholinergic and BDNF signaling. Brain Res. 2019;1712:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S., Sangma T., Shukla S.K., et al. Effect of Cinnamomum zeylanicum extract on scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment and oxidative stress in rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 2015;18:210–216. doi: 10.1179/1476830514Y.0000000113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.J., Kim J., Shim J., et al. Decaffeinated coffee prevents scopolamine-induced memory impairment in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;245:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkenberg I., Blokland A. The validity of scopolamine as a pharmacological model for cognitive impairment: a review of animal behavioral studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010;34:1307–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S.-H., Lee H.-K., Kim J.-A., et al. Neuroprotective effects of chlorogenic acid on scopolamine-induced amnesia via anti-acetylcholinesterase and anti-oxidative activities in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;649:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.C., Park J.H., Ahn J.H., et al. Effects of chronic scopolamine treatment on cognitive impairment and neurofilament expression in the mouse hippocampus. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018;17:1625–1632. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamiya T., Ukai M. [Gly14]-Humanin improved the learning and memory impairment induced by scopolamine in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1597–1599. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa N.M., Mostafa A.M., Ashour M.L., et al. Neuroprotective effects of black pepper cold-pressed oil on scopolamine-induced oxidative stress and memory impairment in rats. Antioxidants. 2021;10:1993. doi: 10.3390/antiox10121993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A., Chatterjee I. Assay of superoxide dismutase activity in animal tissues. J. Biosci. 1988;13:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Owens C., Belcher R. A colorimetric micro-method for the determination of glutathione. Biochem. J. 1965;94:705. doi: 10.1042/bj0940705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk-Ürek R., Bozkaya L.A., Tarhan L. The effects of some antioxidant vitamin-and trace element-supplemented diets on activities of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px and LPO levels in chicken tissues. Cell Biochemistry and Function: Cellular biochemistry and its modulation by active agents or disease. 2001;19:125–132. doi: 10.1002/cbf.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penke B., Szűcs M., Bogár F. Oligomerization and conformational change turn monomeric β-amyloid and tau proteins toxic: Their role in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Molecules. 2020;25:1659. doi: 10.3390/molecules25071659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezze M.-A., Marshall H.J., Cassaday H.J. Scopolamine impairs appetitive but not aversive trace conditioning: Role of the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2017;37:6289–6298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3308-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajashri K., Mudhol S., Serva Peddha M., et al. Neuroprotective effect of spice oleoresins on memory and cognitive impairment associated with scopolamine-induced alzheimer’s disease in rats. ACS Omega. 2020;5:30898–30905. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c03689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin J., Cummings J., Hardy J., et al. Neurobiology of Alzheimer’s disease: integrated molecular, physiological, anatomical, biomarker, and cognitive dimensions. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2015;12:712–722. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150701103107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saba E., Jeong D.-H., Roh S.-S., et al. Black ginseng-enriched Chong-Myung-Tang extracts improve spatial learning behavior in rats and elicit anti-inflammatory effects in vitro. J. Ginseng Res. 2017;41:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samodien E., Johnson R., Pheiffer C., et al. Diet-induced hypothalamic dysfunction and metabolic disease, and the therapeutic potential of polyphenols. Molecular metabolism. 2019;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Tang K. The cellular and molecular processes associated with scopolamine-induced memory deficit: A model of Alzheimer's biomarkers. Life Sci. 2019;233 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelterns P., Feldman H. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease; current status and new perspectives. The Lancet Neurology. 2003;2:539–547. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlede E. Oral acute toxic class method: OECD Test Guideline 423. Rapporti Istisan. 2002:32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D., Puri M., Tiwary A.K., et al. Antiamnesic effect of stevioside in scopolamine-treated rats. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;42:164. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.66840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Verma S., Kapoor M., et al. Alzheimer’s disease like pathology induced six weeks after aggregated amyloid-beta injection in rats: increased oxidative stress and impaired long-term memory with anxiety-like behavior. Neurol. Res. 2016;38:838–850. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1209337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza A.C.G., Brüning C.A., Leite M.R., et al. Diphenyl diselenide improves scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 2010;21:556–562. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833befcf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld B., Scott J., Vilander G., et al. The role of lean process improvement in implementation of evidence-based practices in behavioral health care. J. Behav. Heal. Serv. Res. 2015;42:504–518. doi: 10.1007/s11414-013-9386-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun K., Bai Y., Zhao R., et al. Neuroprotective effects of matrine on scopolamine-induced amnesia via inhibition of AChE/BuChE and oxidative stress. Metab. Brain Dis. 2019;34:173–181. doi: 10.1007/s11011-018-0335-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma V., Singh D. Sinapic acid alleviates oxidative stress and neuro-inflammatory changes in sporadic model of Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Brain Sci. 2020;10:923. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10120923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, N. J., 2017. Animal communication: when i’m calling you, will you answer too? Current biology. 27, R713-R715. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walsh D.M., Selkoe D.J. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2004;44:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zhao F., Ma X., et al. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020;15:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki H.F., Abd-El-Fattah M.A., Attia A.S. Naringenin protects against scopolamine-induced dementia in rats. Bulletin of Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University. 2014;52:15–25. [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.