Abstract

Background

Comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is increasingly common and may have an adverse impact on outcomes in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) of lower extremity. The purpose of this meta-analysis is to compare the postoperative complications between COPD and non-COPD patients undergoing primary TJA including total hip and knee arthroplasty.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library were systematically searched for relevant studies published before December 2021. Postoperative outcomes were compared between patients with COPD versus those without COPD as controls. The outcomes were mortality, re-admission, pulmonary, cardiac, renal, thromboembolic complications, surgical site infection (SSI), periprosthetic joint infection (PJI), and sepsis.

Results

A total of 1,002,779 patients from nine studies were finally included in this meta-analysis. Patients with COPD had an increased risk of mortality (OR [odds ratio] = 1.69, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.42–2.02), re-admission (OR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.38–1.71), pulmonary complications (OR = 2.73, 95% CI 2.26–3.30), cardiac complications (OR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.15–1.69), thromboembolic complications (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.15–1.28), renal complications (OR = 1.50, 95% CI 1.14–1.26), SSI (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.18–1.30), PJI (OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.15–1.38), and sepsis (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.22–1.52).

Conclusion

Patients with comorbid COPD showed an increased risk of mortality and postoperative complications following TJA compared with patients without COPD. Therefore, orthopedic surgeons can use the study to adequately educate these potential complications when obtaining informed consent. Furthermore, preoperative evaluation and medical optimization are crucial to minimizing postoperative complications from arising in this difficult-to-treat population.

Level of evidence

Level III.

Registration

None.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43465-022-00794-2.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Total knee arthroplasty, Total hip arthroplasty, Total joint arthroplasty, Postoperative complications, Systematic reviews, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA) of the lower extremity, including total hip and knee arthroplasty (THA and TKA), is one of the most successful orthopedic operations to reduce joint pain and improve quality of life [1]. However, patients undergoing TJA tend to have more comorbidities than the general population [2, 3]. Furthermore, comorbidities in patients undergoing TJA impact its (TJA) safety with increased rates of medical complications, re-admission rates, and mortality [4–7].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by a progressive airflow limitation and tissue destruction caused by chronic inflammation and structural lung changes [8]. COPD is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality and is the third leading cause of death worldwide [9, 10]. With the rising life expectancy, the number of patients with COPD is increasing in the aging population of patients undergoing TJA.

Additionally, several previous studies have investigated the impact of COPD on the postoperative prognosis for patients undergoing TKA and THA, and the risk was markedly higher for pulmonary, cardiac, thromboembolic complications, infection, and mortality in patients with COPD than in those without COPD [11–15]. However, the impact of COPD on postoperative outcomes after primary TJA of the lower extremity is still not well established. Although the literature increasingly focused on the influence of COPD and various outcomes, there is no comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to the best of our knowledge.

Therefore, this meta-analysis compared the postoperative complications between COPD and non-COPD patients who underwent primary TJA. Furthermore, the results of this study should be beneficial for orthopedic surgeons to optimize treatment strategies and improve outcomes for patients with COPD undergoing primary TJA.

Methods

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16]. This study is registered with the ResearchRegistry and the unique identifying number is: reviewregistry1448. Additionally, the study’s design did not require patient consent or ethical review. Data were extracted, cross-checked, and reviewed separately by two independent authors. Disagreements were, however, resolved through discussion with a third independent author. Using the kappa statistic (κ), inter-reviewer reliability was evaluated for study screening and selection, quality evaluation, data extraction, and result pooling. With a value ranging from 0.92 to 1.00, the inter-reviewer reliability was satisfactory for the screening and selection of studies, quality evaluation, data extraction, and result pooling.

Search Strategy

For studies addressing comorbidities and postoperative complications in patients receiving elective primary TKA or THA, with or without COPD, major literature databases were searched, including MEDLINE/PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, and Scopus (Supplementary file 1). The search was done for publications that were released before December 2021. The [Title/Abstract] field of the search engines was searched using the terms “hip,” “knee,” “arthroplasty,” “replacement,” “pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive,” and “chronic obstructive airway disease,” as well as their corresponding Medical Subject Headings terms. There were no other limitations, not even linguistic ones. To find the relevant articles that were omitted during the database search, relevant eligible references in the selected articles were examined.

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

Two independent authors screened all the titles and abstracts. The initial selected studies were further reviewed for inclusion according to the following uniform criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) prospective or retrospective studies comparing outcomes after TJA between patients with underlying COPD as case group versus non-COPD as control group, (2) patients undergoing TJA of lower extremities, including THA or TKA, (3) at least one postoperative outcome of interest reported, (4) accessible full-text articles, and (5) studies reporting sufficient information to extract and calculate risk estimate and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) case reports, review articles, and conference abstract, (2) studies without a control group, (3) data unable to be extracted. The list of excluded manuscripts from the full-text review was provided (Supplementary file 2).

Data Extraction and Outcomes of Interest

From all selected studies, two independent authors extracted the data. With the help of a third author, disagreements were settled through discussion and consensus. According to the following descriptive information, the data were extracted: (1) study characteristics, such as the first author’s name, the year the study was published, the data source, the study’s design, and its location; (2) patient demographics, including the number of patients, sex, and age; (3) the type of TJA, such as TKA and THA; (4) follow-up period; and (5) outcomes of interest.

Outcomes of Interest

For this meta-analysis, the outcomes of interest included the following: (1) all-cause mortality (at the end of follow-up), length of stay (LOS), revision surgery, re-admission, unplanned return to the operating room, pulmonary complications (including pneumonia, re-intubation, and prolonged use of ventilator > 48 h), cardiac complications (including acute myocardial infarction [AMI], and cardiac arrest), thromboembolic complications (including cerebrovascular accident [CVA], deep vein thrombosis [DVT], and pulmonary embolism [PE]), renal complications (including progressive renal insufficiency [PRI], acute kidney injury [AKI], and urinary tract infection [UTI]), surgical site infection (SSI) (including superficial, deep and organ/space SSI, and periprosthetic joint infection [PJI]), perioperative transfusion rate, and sepsis (including systemic sepsis and septic shock). Revision surgery was defined as removing or replacing the implant during postoperative 1 year. Surgical wound infection was defined as superficial or deep SSI, whereas the organ/space SSI was categorized into PJI.

Quality Assessment

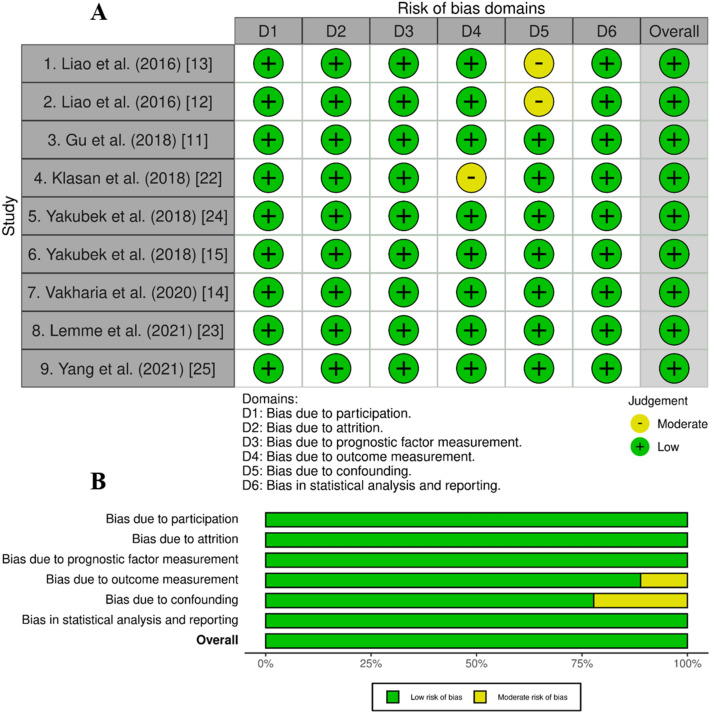

All included studies were evaluated for quality by two independent authors, and any discrepancies were settled through discussion and agreement with a third author. Any included study’s bias was evaluated using the Quality in Prognosis Studies tool, as previously mentioned [17]. This test assesses bias across six domains, including study participants, study attrition, prognostic factor measurement, outcome measurement, study confounding, and statistical analysis and reporting.

Certainty of Evidence

Using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, two independent authors assessed the degree of certainty of the evidence. Certainty of evidence could be high, moderate, low, or very low [18, 19].

Statistical Analysis

The odds ratio (OR) was extracted with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. Adjusted data were maximally used when available. For continuous outcomes, the standardized mean difference (SMD), defined as the intergroup difference in mean outcomes divided by the standard deviation of the difference in the outcome, was calculated at 95% CI. Meta-analyses were conducted to pool the effects and associated 95% CIs. A χ2-based test of homogeneity was performed, and the inconsistency index (I2) and Q statistics were determined. If I2 statistics were < 50%, the fixed-effected model (Mantel–Haenszel method) was used because of the low heterogeneity. I2 ≥ 50% was considered a significant heterogeneity. A “leave-one-out” sensitivity analysis was performed by sequentially deleting one study to determine the heterogeneity source. After excluding each study, an analysis was performed to determine whether heterogeneity existed; if so, the random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird method) was used [20]. Subgroup analyses based on the type of TJA including TKA and THA were performed to investigate the risk of postoperative complications in each subgroup. Publication bias was examined using Egger’s regression symmetry test [21]. All statistical analyses were performed using Rstudio v.1.0.143 (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA) and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Search Results

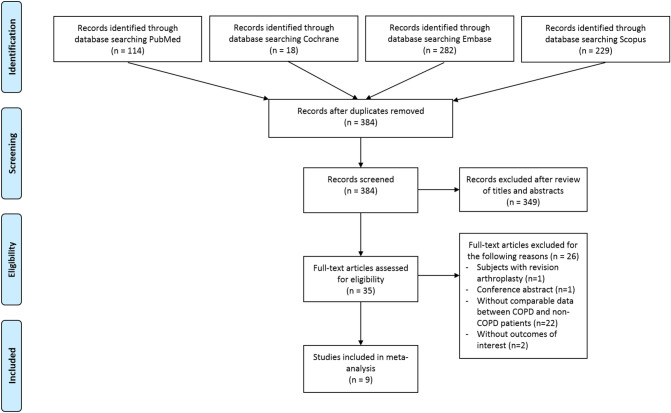

Figure 1 summarizes the details of the study identification and selection process. Six hundred and forty-three articles were yielded after the initial search. Then, two hundred and fifty-nine duplicates were eliminated, and three hundred and forty-nine articles were removed based on their titles and abstracts. Next, among 35 articles that underwent full-text review, 26 without access to the inclusion criteria were excluded. Finally, nine articles were included in the meta-analysis [11–15, 22–25].

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

The characteristics of included studies are described in Table 1. Seven studies [11–13, 15, 23–25] are retrospective cohort studies, whereas two studies [14, 22] are retrospective case–control studies. In total, 1,002,779 cases of lower extremity TJA, including 187,241 patients with COPD and 815,538 patients without COPD, were reported. The nine identified articles described patients who underwent primary THA or TKA. Specifically, three studies [13, 24, 25] investigated primary THA, five studies [11, 12, 14, 15, 23] investigated primary TKA, and one study [22] investigated primary TKA and THA. The quality assessment results for the included studies are shown in Fig. 2. All the included studies were considered low-risk in terms of overall risk of bias. Two studies [12, 13] had a moderate risk of bias in study confounding, while one [22] had a moderate risk of bias in outcome measurement.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author (year) | Data source | Design | Sample size (n) | Type of TJA | Anesthesia mode (%) (general/regional) (COPD vs. non-COPD) | Number of patients (COPD/non-COPD) | Mean age (y) (COPD/non-COPD) | Male (%) (COPD/non-COPD) | Length of follow-up (months) | DM (%) (COPD/Non-COPD) | CAD/MI/CHF (%) (COPD/Non-COPD) | CKD (%) (COPD/Non-COPD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liao et al. (2016) [12] | NHIRD of Taiwan | Retrospective cohort study | 2426 | THA | NA | 335/2091 | 75.88/68.92 | 53.4/41.9 | 1 month | 27.8/24.8 | CAD; 17.9/7.7 | 13.7/9.6 |

| Liao et al. (2016) [13] | NHIRD of Taiwan | Retrospective cohort study | 3431 | TKA | NA | 358/3073 | 72.56/69.78 | 38.0/24.0 | 3 months | 25.7/26.2 | CAD; 17.9/6.9 | 11.7/7.5 |

| Gu et al. (2018) | ACS NSQIP | Retrospective cohort study | 6159 | Bilateral TKA | 60.7/32.1 vs. 59.1/32.1 | 140/6019 | NA | 39.3/57.0 | 1 month | 25.7/15.1 | CHF; 0.7/0.1 | 0/0 |

| Klasan et al. (2018) [22] | Institutional database | Retrospective case–control study | 448 | TKA and THA | Regional; 62.9/63.6 | 224/224 | 70.6/69.5 | 36.6/40.4 | In-hospital | 21.8/15.2 | CHF; 36.1/19.3 | 25.4/18 |

| Yakubek et al. (2018) [15] | ACS NSQIP | Retrospective cohort study | 64,796 | THA | General; 55/55 | 2426/62,370 | 70/65.2 | 39.9/44.2 | 1 month | 16.0/11.3 | CHF; 1.8/0.2 | NA |

| Yakubek et al. (2018) [24] | ACS NSQIP | Retrospective cohort study | 111,168 | TKA | General; 56/53 | 3975/107,193 | 68.7/66.8 | 38.7/37.1 | 1 month | 25.1/17.6 | CHF; 1.2/0.2 | NA |

| Vakharia et al. (2020) [14] | PearlDiver Patient Records Database | Retrospective case–control study | 211,378 | TKA | NA | 35,230/176,148 | NA | 34.2/34.2 | 3 months | 58.3/58.3 | CAD; 66.4/66.4 | NA |

| Lemme et al. (2021) [23] | PearlDiver Patient Records Database | Retrospective cohort study | 166,946 | TKA | NA | 46,769/120,177 | NA | 32.6/43.0 | 3 months | 64.2/53.5 | CHF; 28.3/15.1 | 0.3/0.2 |

| Yang et al. (2021) [25] | PearlDiver Patient Records Database | Retrospective cohort study | 436,027 | THA | NA | 97,784/338,243 | NA | 38.2/45.0 | 1 month | 48.1/36.8 | CHF; 19.3/9.3 | 22.5/16.1 |

TJA total joint arthroplasty, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DM diabetes mellitus, CAD coronary artery disease, MI myocardial infarction, CHD chronic heart disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, NHIRD National Health Insurance Research Database, THA total hip replacement; Registry, ACS NSQIP American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, NIS National Inpatient Sample

Fig. 2.

A, B Quality assessment

Meta-Analysis Results

Complications

Meta-analysis results for postoperative complications between patients with or without COPD are summarized in Table 2. The pooled results demonstrated that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of mortality (OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.42–2.02, I2 = 38%), re-admission (OR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.38–1.71, I2 = 96%), unplanned return to operating room (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.14–1.62, I2 = 0%), revision surgery (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.01–1.46, I2 = 92%), and a prolonged LOS (SMD = 0.16, 95% CI 0.11–0.21, I2 = 60%). For pulmonary complications, the pooled results showed that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of overall pulmonary complications (OR = 2.73, 95% CI 2.26–3.30, I2 = 64%), pneumonia (OR = 2.70, 95% CI 2.13–3.43, I2 = 75%), re-intubation (OR = 3.07, 95% CI 2.18–4.31, I2 = 31%), and ventilator use > 48 h (OR = 3.47, 95% CI 2.16–5.56, I2 = 8%). Furthermore, the heterogeneity could not be ignored for the summary analysis of re-admission, revision surgery, LOS, pulmonary complications, and pneumonia.

Table 2.

Summary of prognostic evidence of complications after total joint arthroplasty in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

| OR or SMD | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | P value | Heterogeneity (%) | Analysis model | Egger’s test (P value) | Grading of recommendation assessment, development, and evaluation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other consideration | Certainty of evidence with explanations for downgrading of evidence | ||||||||

| Mortality | 1.69 | 1.42 | 2.02 | < 0.01 | 38 | Fixed | 0.07 | 5 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Length of stay | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.21 | < 0.01 | 60 | Random | 0.99 | 4 | Observational studies | Not serious | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | None |

Low aStatistical heterogeneity and inconsistency in direction of effect |

| Re-admission | 1.54 | 1.38 | 1.71 | < 0.01 | 96 | Random | 0.23 | 7 | Observational studies | Not serious | Seriousb | Not serious | Not serious | None |

Low aStatistical heterogeneity and inconsistency in direction of effect |

| Return to operating room | 1.36 | 1.14 | 1.62 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.34 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Perioperative transfusion | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 0.95 | 11 | Fixed | 0.05 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Revision | 1.21 | 1.01 | 1.46 | 0.04 | 92 | Random | NA | 2 | Observational studies | Not serious | Seriousc | Not serious | Seriousd | None |

Very low cStatistical heterogeneity and inconsistency in direction of effect dTwo studies with small sample size and wide confidence interval |

| Overall pulmonary complication | 2.73 | 2.26 | 3.30 | < 0.01 | 64 | Random | 0.01 | 7 | Observational studies | Not serious | Seriouse | Not serious | Not serious | None |

Low eStatistical heterogeneity and inconsistency in direction of effect |

| Pneumonia | 2.70 | 2.13 | 3.43 | < 0.01 | 75 | Random | 0.01 | 7 | Observational studies | Not serious | Seriousf | Not serious | Not serious | None |

Low fStatistical heterogeneity and inconsistency in direction of effect |

| Re-intubation | 3.07 | 2.18 | 4.31 | < 0.01 | 31 | Fixed | NA | 2 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousg | None |

Low gTwo studies with small sample size and wide confidence interval |

| Prolonged use of ventilator > 48 h | 3.47 | 2.16 | 5.56 | < 0.01 | 8 | Fixed | 0.79 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Overall cardiac complication | 1.40 | 1.15 | 1.69 | < 0.01 | 37 | Fixed | 0.09 | 4 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.41 | 0.95 | 2.10 | 0.09 | 49 | Fixed | 0.20 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Cardiac arrest | 2.61 | 1.55 | 4.39 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.36 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Overall thromboembolic complication | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.28 | < 0.01 | 13 | Fixed | 0.02 | 6 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1.67 | 1.14 | 2.46 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.18 | 4 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1.20 | 1.14 | 1.26 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.88 | 4 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2.73 | 2.31 | 3.23 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.81 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Overall renal complication | 1.50 | 1.14 | 1.26 | 0.02 | 35 | Fixed | 0.01 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Serioush | Not serious | Not serious | None |

Low hStatistical heterogeneity and inconsistency in direction of effect |

| Acute kidney injury | 2.23 | 1.11 | 4.50 | 0.02 | 0 | Random | NA | 2 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousi | None |

Low iTwo studies with small sample size and wide confidence interval |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 4.17 | 0.92 | 18.92 | 0.06 | 79 | Random | NA | 2 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousj | None |

Low jTwo studies with small sample size and wide confidence interval |

| Urinary tract infection | 1.35 | 1.10 | 1.65 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.93 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Surgical site infection | 1.24 | 1.18 | 1.31 | < 0.01 | 29 | Fixed | 0.11 | 8 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Wound infection (superficial and deep) | 1.22 | 1.15 | 1.30 | < 0.01 | 24 | Fixed | 0.35 | 5 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Periprosthetic joint infection | 1.26 | 1.15 | 1.38 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.53 | 5 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Sepsis | 1.36 | 1.22 | 1.52 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.16 | 4 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

| Septic shock | 2.23 | 1.27 | 3.93 | < 0.01 | 0 | Fixed | 0.02 | 3 | Observational studies | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | Moderate |

OR odds ratio, SMD standardized mean difference, LL lower limit, CI confidence interval, UL upper limit

For cardiac complications, the pooled results demonstrated that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of overall cardiac complications (OR = 1.40, 95% CI 1.15–1.69, I2 = 37%) and cardiac arrest (OR = 2.61, 95% CI 1.55–4.39, I2 = 0%). For thromboembolic complications, the pooled results demonstrated that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of overall thromboembolic complications (OR = 1.21, 95% CI 1.15–1.28, I2 = 13%), CVA (OR = 1.67, 95% CI 1.14–2.46, I2 = 0%), DVT (OR = 1.20, 95% CI 1.14–1.26, I2 = 0%), and PE (OR = 2.73, 95% CI 2.31–3.23, I2 = 0%). Additionally, for renal complications, the pooled results demonstrated that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of overall renal complications (OR = 1.50, 95% CI 1.14–1.26, I2 = 35%), AKI (OR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.11–4.50, I2 = 0%), and UTI (OR = 1.35, 95% CI 1.10–1.65, I2 = 0%). Furthermore, the pooled results demonstrated that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of overall SSI (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.18–1.30, I2 = 34%), surgical wound infection (OR = 1.22, 95% CI 1.15–1.30, I2 = 24%), and PJI (OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.15–1.38, I2 = 0%). The pooled results showed that patients with COPD were associated with increased risk of sepsis (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.22–1.52, I2 = 0%) and septic shock (OR = 2.23, 95% CI 1.27–3.93, I2 = 0%). Our GRADE certainty of evidence judgements is included in Table 2. The most common reasons for downgrading certainty of evidence were inconsistency and imprecision.

Subgroup Analyses

The results of the subgroup analyses are summarized in Supplementary table 1. Subgroup analyses found significant statistical differences in risk of various postoperative complications. The results demonstrated that patients with THA were associated with higher risk of mortality, overall pulmonary complications, re-intubation, prolonged use of ventilator, UTI, PJI, and sepsis, while the patients with TKA showed higher risk of return to operating room, cardiac arrest, CVA, DVT, PE, overall renal complications, surgical wound infection, and septic shock. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution because only one study was included to estimate the risk of return to operating room, re-intubation, prolonged use of ventilator, cardiac arrest, DVT, PE, UTI, surgical wound infection, and septic shock (Supplementary table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses and Publication Bias

Sensitivity analyses were performed using the leave-one-out approach to assess whether individual studies would affect the overall results of each meta-analysis. The meta-analysis was reliable and no single study had a significant impact on the results, as shown by the fact that the direction of combined estimates did not change significantly when the studies were eliminated. However, two studies by Vahkaria et al. [14] and Yakubek et al. [24] strongly affected the pooled results of overall thromboembolic complications and surgical wound infection, respectively, and they were discarded from each meta-analysis (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2).

Discussion

This review and meta-analysis investigated whether COPD adversely impacted the postoperative outcomes of TJA with data of over one million patients. The most important findings are that patients with COPD had a significantly increased mortality risk compared with those without COPD. In addition, patients with COPD showed longer LOS and had an increased risk of re-admission, unplanned return to the operating room, and 1-year revision surgery. Furthermore, COPD was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing postoperative complications, including pulmonary, cardiac, thromboembolic, renal complications, SSI, PJI, and sepsis in patients undergoing TJA.

Patients with COPD are in a state of chronic systemic/vascular inflammation and hypercoagulation with an upregulated C-reactive protein, increased production of inflammatory cytokines and tissue factors, higher fibrinogen levels [26, 27]. COPD also shares several risk factors or comorbidities with cardiac or thromboembolic complications including older age, cigarette smoking, and ischemic heart disease [28–30]. Studies included in the present review also reported higher incidence of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disorders (Table 1). This exaggerated inflammatory response and comorbidities associated with COPD may predispose patients to venous thromboembolic complications, CVA, and cardiovascular complications. Previous studies suggested that patients with COPD had an increased risk of postoperative cardiac complications following cardiac and non-cardiac surgeries [28, 31]. COPD patients also have high prevalence of venous thromboembolism including DVT and PE [32, 33]. Similarly, the pooled results of this study demonstrated that COPD was independently associated with postoperative cardiac and thromboembolic complications including cardiac arrest, DVT, PE, and CVA. However, the results from the present study does not qualify as a statistical significant risk factor for myocardial infarction. This apparent discrepancy in the results could be explained by the fact that the increased risk of myocardial infarction in previous studies [34, 35] was restricted to within 1–5 days, whereas the current analysis encompassed 30 days of postoperative data.

Additionally, impaired gas exchange and mucociliary clearance of aspirated bacteria can predispose COPD patients to postoperative pulmonary complications [8, 36]. The present study demonstrated that COPD was significantly associated with overall pulmonary complications, pneumonia, and respiratory failure, including re-intubation or failure to wean from the ventilator within 48 h. However, our findings concerning overall pulmonary complications and pneumonia should be interpreted with caution because of their high heterogeneity. For example, anesthesia mode is a crucial factor associated with postoperative pulmonary complications [37, 38]. However, only four studies reported that anesthesia mode and regional anesthesia rates vary, contributing to heterogeneity [11, 15, 22, 24].

For renal complications, the pooled analyses of this study determined COPD to be a risk factor after TJA, consistent with previous studies regarding cardiac or non-cardiac surgeries [28, 39]. Rodrigues et al. [39] found COPD to be a risk factor for AKI after cardiac surgery; Gupta et al. [28] found the association between COPD and postoperative renal insufficiency and AKI requiring dialysis in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. The components of smoke, including nicotine and several heavy metals, are risk factors for kidney disease, and various comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, CKD, and cardiovascular disease, are highly prevalent in patients with COPD [28–30, 40–42] (Table 1). Therefore, these may be contributing factors to postoperative renal complications.

Additionally, our study showed that patients with COPD have an increased risk of UTI, SSI, PJI, and sepsis. A potential explanation for these complications is related to immune system derangements secondary to the chronic inflammatory state observed in patients with COPD, leading to bacterial retention, biofilm formation, increased risk of various infectious complications, and sepsis [26, 27, 43, 44]. Chronic hypoxia resulting from obstructed ventilation also results in poor wound healing, increased risk of SSI by poor tissue oxygenation, and increased reactive oxygen species [45, 46]. Furthermore, using corticosteroids to manage COPD may increase the risk of infection [47]. The reported incidence of sepsis following TJA was 0.34%, and sepsis is associated with a high-risk mortality [48]. The most common sources of sepsis were UTI, SSI, and pneumonia, which are postoperative complications with increased risk in patients with COPD [48]. Therefore, these results further explain the importance of immaculate sterile technique, safely tapering systemic steroids preoperatively, and good respiratory management in the postoperative recovery period.

In this study, patients with COPD had a significantly increased mortality compared with those without, which agrees with findings in the literature from other surgical subspecialties [28, 49, 50]. Although studies included did not report the specific causes of mortality, patients experiencing postoperative adverse events have a high postoperative mortality rate [28, 51, 52]. The increased risk of postoperative complications, such as cardiac arrest, pulmonary embolism, CVA, and sepsis, may contribute to the increased mortality in the present study.

Re-admission, LOS, return to the operating room, and revision surgeries are related to the increased costs of care. Of all medical comorbidities, performing a TKA on a patient with COPD has the highest cost, averaging $26,299 per patient [53]. Consistent with previous studies regarding cardiac and non-cardiac surgeries, this study found that patients with COPD had an increased risk of LOS, re-admission, and return to the operating room following TJA [28, 50, 54]. No included studies except one by Vakharia et al. [14] reported the exact causes of increased LOS, re-admission, or return to the operating room. Vakharia et al. [14] reported that the leading causes of re-admission in descending order were SSI, pulmonary, and cardiac causes. However, our results on LOS and re-admission should be interpreted with caution because of their moderate to high heterogeneity.

The causes of revision surgery include infection, dislocation, osteolysis, or loosening of the component. Furthermore, dislocation and mechanical loosening are the main causes after THA, and a systematic review reported that risk factors for THA included younger age, more comorbidities, and avascular necrosis [55]. For TKA, infection and mechanical loosening were reportedly the primary etiology for revision, associated mainly with demographic and surgical factors, such as uncemented procedure, implant malalignment, and longer operative times [56]. This study found that patients with COPD had an increased risk of 1-year revision surgery. However, data from only two studies, including each THA and TKA cohort, were pooled, and both studies have not adjusted for the aforementioned confounding risk factors [23, 25]. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution, and future studies are needed to determine the risk and causes of revision surgery accounting for various risk factors in patients with comorbidities, including COPD.

According to this study’s results, comorbid COPD significantly adversely impacted the safety of TJA. Therefore, recognizing COPD and its associated comorbidities is crucial to optimizing these high-risk patients for surgery perioperatively [57, 58]. This study has strengths and limitations. The first study on concomitant COPD and outcomes following elective TJA was conducted, and that study is this review and meta-analysis. Additionally, the analysis was reinforced by using data from 1,002,779 patients throughout the nine trials that were included. Furthermore, the findings in this meta-analysis were centered on the most current research; as all of the clinical reports it included had only been published during the previous five years.

Nevertheless, the following limitations of this review should be noted. First, only retrospective studies with a low level of evidence were included. However, most of the included studies used national claims or registry databases to provide reliable postoperative outcomes [59]. Second, the studies were heterogeneous regarding the baseline characteristics of the cohorts, comorbidities, and outcome measurements. COPD was commonly associated with various comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, CKD, and cardiovascular diseases that impact postoperative outcomes after lower extremity arthroplasty. Therefore, the potential influence of these confounding factors can be a source of heterogeneity of the results and have exaggerated our results. Third, subgroup analyses were performed based on the type of TJA because these patients may have various indications for surgery, different comorbidities, and levels of mobility, as well as be exposed to different surgical burdens and postoperative protocols. However, there is serious concern about the certainty of estimates because most of the results were based on one included study. Fourth, the definition of COPD varied among studies because of the inherent limitations of the national claims or registry database in which the diagnoses are based on disease codes. Furthermore, it was unable to assess the severity of COPD and its impact on the dependent variables measured. Two studies by Yakubek et al. only included patients with COPD and the following criteria: a functional disability due to COPD, chronic bronchodilator therapy, an exacerbation requiring hospitalization, or a forced expiratory volume in 1 s less than 75% of the expected [15, 24]. Therefore, it could not explain the sources of substantial heterogeneity in several outcomes, such as pulmonary complications, pneumonia, LOS, and re-admission. Future prospective studies are highly warranted to more accurately investigate COPD’s impact on TJA and address the prognostic roles of different severities of COPD.

Conclusively, patients with comorbid COPD showed an increased risk of mortality and postoperative complications following TJA compared with patients without COPD. Therefore, orthopedic surgeons can use the study to adequately educate these potential complications when obtaining informed consent. Furthermore, preoperative evaluation and medical optimization are crucial to minimizing postoperative complications from arising in this difficult-to-treat population.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary figure 1. Sensitivity analyses for overall thromboembolic complications Supplementary file1 (TIFF 747 KB)

Supplementary figure 2. Sensitivity analyses for surgical wound infection Supplementary file2 (TIFF 747 KB)

Abbreviations

- TJA

Total joint arthroplasty

- THA

Total hip arthroplasty

- TKA

Total knee arthroplasty

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- PRISMA

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- LOS

Length of stay

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

- CVA

Cerebrovascular accident

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- PE

Pulmonary embolism

- PRI

Progressive renal insufficiency

- AKI

Acute kidney injury

- UTI

Urinary tract infection

- SSI

Surgical site infection

- PJI

Periprosthetic joint infection

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

Author contributions

KHS was the project leader and participated in all aspects of the study, including planning, design, literature searches, data screening and extraction, quality appraisal, and management of all aspects of manuscript preparation and submission. JUK, ITJ, SBH, and SBK contributed to literature searches, data screening and extraction, quality appraisal, and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding source was applicable to any part of this study.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kyun-Ho Shin, Email: kyunho.shin@gmail.com.

Jin-Uk Kim, Email: ultralex@mfnanoori.co.kr.

Il-Tae Jang, Email: nanoori_research@naver.com.

Seung-Beom Han, Email: oshan@korea.ac.kr.

Sang-Bum Kim, Email: luckymd@naver.com.

References

- 1.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu SS, Della Valle AG, Besculides MC, Gaber LK, Memtsoudis SG. Trends in mortality, complications, and demographics for primary hip arthroplasty in the United States. International Orthopaedics. 2009;33:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0549-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memtsoudis SG, Della Valle AG, Besculides MC, Gaber L, Laskin R. Trends in demographics, comorbidity profiles, in-hospital complications and mortality associated with primary knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2009;24:518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.01.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim CW, Kim HJ, Lee CR, Wang L, Rhee SJ. Effect of chronic kidney disease on outcomes of total joint arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2020;32:12. doi: 10.1186/s43019-020-0029-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulshrestha V, Sood M, Kumar S, Sood N, Kumar P, Padhi P. Does risk mitigation reduce ninety-day complications in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty? A cohort study. Clin Orthop Surg. 2021;13:e70. doi: 10.4055/cios20234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park BY, Lim KP, Shon WY, Shetty YN, Heo KS. Comparison of functional outcomes and associated complications in patients who underwent total hip arthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in relation to their underlying medical comorbidities. Hip Pelvis. 2019;31:232–237. doi: 10.5371/hp.2019.31.4.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podmore B, Hutchings A, van der Meulen J, Aggarwal A, Konan S. Impact of comorbid conditions on outcomes of hip and knee replacement surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal Open. 2018;8:e021784. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Respirology. 2017;22:575–601. doi: 10.1111/resp.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quaderi SA, Hurst JR. The unmet global burden of COPD. Glob Health Epidemiol Genom. 2018;3:e4. doi: 10.1017/gheg.2018.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rycroft CE, Heyes A, Lanza L, Becker K. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A literature review. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2012;7:457–494. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S32330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu A, Wu S, Mancino F, Liu J, Ast MP, Abdel MP, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on postoperative complications following simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2018;34:322–327. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1695766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao KM, Lu HY. Complications after total knee replacement in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A nationwide case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4835. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao KM, Lu HY. A national analysis of complications following total hip replacement in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3182. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vakharia RM, Adams CT, Anoushiravani AA, Ehiorobo JO, Mont MA, Roche MW. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with higher rates of venous thromboemboli following primary total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2020;35(2066–2071):e9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakubek GA, Curtis GL, Khlopas A, Faour M, Klika AK, Mont MA, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with short-term complications following total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2623–2626. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;158:280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, Alba C, Lang E, Burnand B, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: Rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015;350:h870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: An emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klasan A, Dworschak P, Heyse TJ, Ruchholtz S, Alter P, Vogelmeier CF, et al. COPD as a risk factor of the complications in lower limb arthroplasty: A patient-matched study. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2018;13:2495–2499. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemme NJ, Glasser JL, Yang DS, Testa EJ, Daniels AH, Antoci V. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with prolonged opiate use, increased short-term complications, and the need for revision surgery following total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2021 doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1733883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yakubek GA, Curtis GL, Sodhi N, Faour M, Klika AK, Mont MA, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with short-term complications following total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33:1926–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang DS, Glasser J, Lemme NJ, Quinn M, Daniels AH, Antoci V., Jr Increased medical and implant-related complications in total hip arthroplasty patients with underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59:574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomsen M, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Inflammatory biomarkers and comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;186(10):982–988. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1113OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta H, Ramanan B, Gupta PK, Fang X, Polich A, Modrykamien A, et al. Impact of COPD on postoperative outcomes: Results from a national database. Chest. 2013;143:1599–1606. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;33:1165–1185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corsonello A, Antonelli Incalzi R, Pistelli R, Pedone C, Bustacchini S, Lattanzio F. Comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2011;17(Suppl 1):S21–S28. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000410744.75216.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertges DJ, Goodney PP, Zhao Y, Schanzer A, Nolan BW, Likosky DS, et al. The Vascular Study Group of New England Cardiac Risk Index (VSG-CRI) predicts cardiac complications more accurately than the revised cardiac risk index in vascular surgery patients. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2010;52:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunen H, Gulbas G, In E, Yetkin O, Hacievliyagil SS. Venous thromboemboli and exacerbations of COPD. European Respiratory Journal. 2010;35:1243–1248. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00120909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein PD, Beemath A, Meyers FA, Olson RE. Pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in hospitalized adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine (Hagerstown, Md.) 2007;8:253–257. doi: 10.2459/01.JCM.0000263509.35573.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donaldson GC, Hurst JR, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Wedzicha JA. Increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke following exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2010;37:1091–1097. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothnie KJ, Yan R, Smeeth L, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and death following MI in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal Open. 2015;5:e007824. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smetana GW, Lawrence VA, Cornell JE, College A, of Physcians, Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: Systematic review for the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144:581–595. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Lier F, van der Geest PJ, Hoeks SE, van Gestel YR, Hol JW, Sin DD, et al. Epidural analgesia is associated with improved health outcomes of surgical patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:315–321. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318224cc5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hausman MS, Jr, Jewell ES, Engoren M. Regional versus general anesthesia in surgical patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Does avoiding general anesthesia reduce the risk of postoperative complications? Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2015;120:1405–1412. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodrigues AJ, Evora PR, Bassetto S, Alves Júnior L, Scorzoni Filho A, Araujo WF, et al. Risk factors for acute renal failure after heart surgery. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular. 2009;24:441–446. doi: 10.1590/s0102-76382009000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen J, Zhang F, Liu CY, Yuan QM, Di XS, Long SW, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on outcomes after total joint arthroplasty: A meta-analysis and systematic review. International Orthopaedics. 2020;44:215–229. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Incalzi RA, Corsonello A, Pedone C, Battaglia S, Paglino G, Bellia V, et al. Chronic renal failure: A neglected comorbidity of COPD. Chest. 2010;137:831–837. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin W, Huang X, Yang H, Shen M. The influence of diabetes mellitus on patients undergoing primary total lower extremity arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Research International. 2020;2020:6661691. doi: 10.1155/2020/6661691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhat TA, Panzica L, Kalathil SG, Thanavala Y. Immune dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S169–S175. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-126AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shin KH, Han SB, Song JE. Risk of periprosthetic joint infection in patients with total knee arthroplasty undergoing colonoscopy: A nationwide propensity score matched study. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2022;37:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. Journal of Dental Research. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perotin JM, Adam D, Vella-Boucaud J, Delepine G, Sandu S, Jonvel AC, et al. Delay of airway epithelial wound repair in COPD is associated with airflow obstruction severity. Respiratory Research. 2014;15:151. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0151-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD, INFORM Team Patient-related risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection after total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bohl DD, Sershon RA, Fillingham YA, Della Valle CJ. Incidence, risk factors, and sources of sepsis following total joint arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty. 2016;31:2875–2879.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta PK, Mactaggart JN, Natarajan B, Lynch TG, Arya S, Gupta H, et al. Predictive factors for mortality after open repair of paravisceral abdominal aortic aneurysm. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2012;55:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saleh HZ, Mohan K, Shaw M, Al-Rawi O, Elsayed H, Walshaw M, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity on surgical outcomes in patients undergoing non-emergent coronary artery bypass grafting. European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2012;42:108–113. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Devereaux PJ, Goldman L, Cook DJ, Gilbert K, Leslie K, Guyatt GH. Perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: A review of the magnitude of the problem, the pathophysiology of the events and methods to estimate and communicate risk. CMAJ. 2005;173:627–634. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Temgoua MN, Tochie JN, Noubiap JJ, Agbor VN, Danwang C, Endomba FTA, et al. Global incidence and case fatality rate of pulmonary embolism following major surgery: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Systematic Reviews. 2017;6(1):240. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0647-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabeh KG, Rosas S, Buller LT, Freiberg AA, Emory CL, Roche MW. The impact of medical comorbidities on primary total knee arthroplasty reimbursements. The Journal of Knee Surgery. 2019;32:475–482. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1651529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manganas H, Lacasse Y, Bourgeois S, Perron J, Dagenais F, Maltais F. Postoperative outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Canadian Respiratory Journal. 2007;14:19–24. doi: 10.1155/2007/378963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prokopetz JJ, Losina E, Bliss RL, Wright J, Baron JA, Katz JN. Risk factors for revision of primary total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2012;13:251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jasper LL, Jones CA, Mollins J, Pohar SL, Beaupre LA. Risk factors for revision of total knee arthroplasty: A scoping review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2016;17:182. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1025-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Licker M, Schweizer A, Ellenberger C, Tschopp JM, Diaper J, Clergue F. Perioperative medical management of patients with COPD. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2007;2:493–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kulshrestha V, Sood M, Kumar S, Sood N, Kumar P, Padhi PP. Does risk mitigation reduce 90-day complications in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty?: A cohort study. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery. 2022;14:56–68. doi: 10.4055/cios20234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kimm H, Yun JE, Lee SH, Jang Y, Jee SH. Validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in korean national medical health insurance claims data: The korean heart study (1) Korean Circulation Journal. 2012;42:10–15. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figure 1. Sensitivity analyses for overall thromboembolic complications Supplementary file1 (TIFF 747 KB)

Supplementary figure 2. Sensitivity analyses for surgical wound infection Supplementary file2 (TIFF 747 KB)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.