Abstract

Background

Celiac disease has an increasing incidence worldwide and is treated with lifelong adherence to a gluten-free diet. We aimed to describe gluten-free diet adherence rates in children with screening-identified celiac disease, determine adherence-related factors, and compare adherence to food records in a multinational prospective birth cohort study.

Methods

Children in The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young study with celiac disease were included. Subjects had at least annual measurement of adherence (parent-report) and completed 3-day food records. Descriptive statistics, t-tests, Kruskal-Wallis tests and multivariable logistic and linear regression were employed.

Results

Two hundred ninety (73%) and 199 (67%) of subjects were always adherent to a gluten-free diet at 2 and 5 years post celiac disease diagnosis respectively. The percentage of children with variable adherence increased from 1% at 2 years to 15% at 5 years. Children with a first-degree relative with celiac disease were more likely to be adherent to the gluten-free diet. Gluten intake on food records could not differentiate adherent from nonadherent subjects. Adherent children from the United States had more gluten intake based on food records than European children (P < .001 and P = .007 at 2 and 5 years respectively).

Conclusion

Approximately three-quarters of children with screening-identified celiac disease remain strictly adherent to a gluten-free diet over time. There are no identifiable features associated with adherence aside from having a first-degree relative with celiac disease. Despite good parent-reported adherence, children from the United States have more gluten intake when assessed by food records. Studies on markers of gluten-free diet adherence, sources of gluten exposure (particularly in the United States), and effects of adherence on mucosal healing are needed.

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) affects up to 1.4% of the world’s population [1] has a rising incidence and prevalence, particularly in Europe [2, 3], and is one of the most common childhood gastrointestinal diseases [4]. While there are limited studies in non-Western countries, the incidence of CD is likely increasing worldwide [5–7]. A strict gluten-free diet (GFD) is the only treatment for CD [8, 9], yet there are few longitudinal studies on adherence to a GFD and no international studies comparing adherence. Because inadequately treated CD is associated with growth stunting [10], nutritional deficiencies [11], neurologic and psychiatric disorders [12, 13], and impaired quality of life [14–16], understanding GFD adherence is critical in the care of CD patients.

There is currently no universal method of assessing adherence to a GFD. Gastroenterologists frequently use a combination of self and parent-reported adherence, presence of symptoms, assessment by a dietitian (if available), or serological markers. While numerous gastrointestinal societies have recommended routine assessment of GFD adherence [8, 17, 18], no standardized method of assessment exists. Moreover, children with CD are frequently lost to follow-up [19, 20] and those that are lost to follow-up are suspected to be more nonadherent [21, 22]. The aims of this study are to measure longitudinal rates of parent-reported adherence in children with screening-identified CD, determine factors related to adherence, and compare parent-reported adherence to food records in a multinational cohort of children with CD.

Materials and methods

Study population

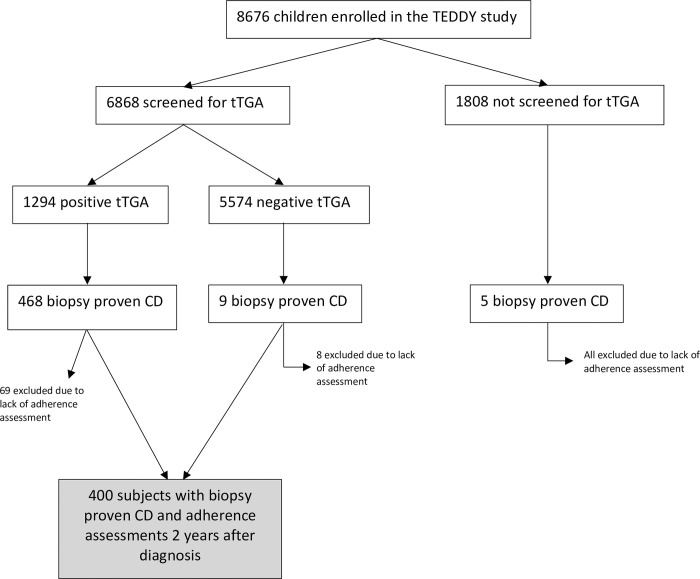

The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study is a multinational prospective observational birth cohort study that aimed to identify environmental factors associated with type 1 diabetes and CD in children at genetic risk. Subjects in the TEDDY study were followed from birth until the age of 15 years at 1 of 6 clinical research centers located in both the United States (Colorado, Georgia, and Washington) and Europe (Finland, Germany, and Sweden). Between September 2004 and February 2010, 424,788 newborns were screened with 21,589 having 1 of 9 targeted HLA genotypes. Of the infants carrying a permissive HLA genotype, 8,676 were enrolled in the prospective follow-up. Details of the study design, eligibility, and methods have been published previously [23–26]. The study was approved by local Institutional Review Boards and is monitored by an External Advisory Board formed by the National Institutes of Health. For the current study, subjects were included if they had biopsy-proven CD, were followed by the study for at least 2 years after CD diagnosis, and completed annual adherence questionnaires for at least 2 years after CD diagnosis. A detailed flowchart depicting inclusion and exclusion criteria is depicted in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the current TEDDY study. Abbreviations: Celiac disease (CD); The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY); tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies (tTGA).

CD diagnosis

Serum samples were obtained from all children enrolled in TEDDY every 3 months until the age of 4 years and every 6 months thereafter. Annual screening for CD with serum tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies (tTGA) started at 2 years of age. If a child tested positive at 2 years, earlier blood samples were also analyzed. Guardians of children with a positive test result of tTGA were informed, and if tTGA remained positive on the next sample, were advised to consult a pediatric gastroenterologist for additional evaluation of CD. Subjects were defined as having CD if they had an intestinal biopsy with Marsh score of 2 or greater.

Questionnaires and adherence definition

A specific questionnaire evaluating children for signs and symptoms associated with CD (abdominal discomfort, anemia, chronic constipation, dental enamel defects, fatigue, frequent loose stools, irritability, neurologic symptoms, vomiting, skin irritation, and poor growth) was obtained every 6 months until the age of 2 and annually thereafter. A GFD form was administered to all subjects diagnosed with CD at their next follow-up visit and annually thereafter. Subjects were considered to be “adherent” if parents reported their child ate gluten “never” or “less than once per month” in each annually-submitted questionnaire form at every follow-up until 2 years or 5 years from the diagnosis of CD. Subjects were considered to be “nonadherent” if parents reported they ate gluten “once per month,” “several times per month,” “several times per week,” or “nearly every day” in any questionnaire form during follow-up of 2 years or 5 years post the diagnosis of CD.

Dietary assessment

The dietary assessment method used in this study has been described in detail in other publications [27, 28]. Gluten intake was estimated from 3-day food records (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day). Primary caretakers were trained on how to keep the food records during their 3-month visit. Food records were completed every 3 months for the first year of life and then biannually thereafter until 10 years of age. A harmonized food-grouping system was used to facilitate a comparison and quantification of food consumption between individual countries [29]. Mean gluten intake (grams/day) was calculated from total gluten-containing flours (wheat, rye, and barley) reported during the 3-day recording period. Protein content was obtained from the daily intake of gluten-containing flours and converted to amount of gluten using a conversion factor of 0.8 (the gluten content in wheat protein). Data regarding gluten consumption was included in this study if food records were submitted within 2–3 years after the diagnosis of CD (for the 2-year analysis) and 5–6 years after the diagnosis of CD (for the 5-year analysis).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to determine the percentage of adherent and nonadherent subjects at 2 and 5 years post diagnosis of CD. Quantitative comparison of gluten intake was then performed using t-tests and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Multivariate logistic regression was used to confirm the association between parent-reported adherence with gluten intake, adjusting for country and the duration of time between measurements of parent-reported adherence and gluten intake.

Results

Parent-reported adherence

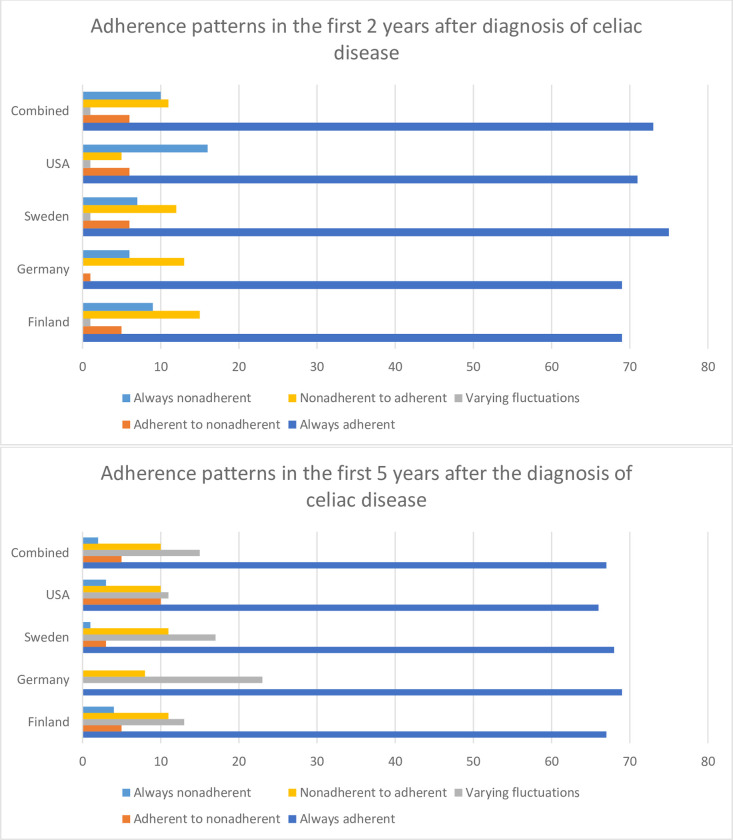

Parent/guardian-reported adherence to GFD was available for 400 subjects at 2 years post diagnosis of CD and 296 subjects at 5 years post diagnosis of CD (Fig 2). The average number of forms submitted per subject was 1.87 (at 2 years) and 4.47 (at 5 years). The majority of subjects were always adherent to a GFD at 2 and 5 years after the diagnosis of CD (73% and 67% respectively). Ten percent of subjects were always nonadherent at 2 years post diagnosis of CD while only 3% of subjects were always nonadherent at 5 years post diagnosis. One percent of subjects had with variable adherence at 2 years while 15% had variable adherence at 5 years. At 2 years post CD diagnosis, adherent subjects did not differ from nonadherent subjects with regards to sex, country of origin, community type, age at diagnosis, age at form submissions, comorbidities, and parental characteristics (Table 1). Adherent subjects were more likely to have a first degree relative with CD (21% versus 13%, P = .04 at 2 years and 24% versus 13%, P = .04 at 5 years). Nonadherent subjects were more likely to endorse gastrointestinal symptoms at 2 years only (52% versus 36%, P = .03).

Fig 2. Country variations in adherence.

Gluten-free diet adherence patterns stratified by country at 2 and 5 years post the diagnosis of celiac disease.

Table 1. Subject characteristics.

Subject characteristics at 2 and 5 years post the diagnosis of celiac disease stratified by self-reported gluten-free diet adherence.

| 2 years post CD diagnosis | 5 years post CD diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Adherent (N = 290) | Nonadherent (N = 110) | p-value | Adherent (N = 199) | Nonadherent (N = 97) | p-value |

| Sex (%) | 0.27 | 0.23 | ||||

| Female | 187 (65) | 65 (59) | 132 (66) | 58 (60) | ||

| Male | 103 (36) | 45 (41) | 67 (34) | 39 (40) | ||

| Country (%) | 0.79 | 0.98 | ||||

| Finland | 51 (18) | 23 (21) | 37 (19) | 18 (19) | ||

| Germany | 11 (4) | 5 (5) | 9 (5) | 4 (4) | ||

| Sweden | 148 (51) | 50 (45) | 101 (51) | 48 (49) | ||

| United States | 80 (28) | 32 (29) | 52 (26) | 27 (28) | ||

| Location (%) | 0.61 | 0.54 | ||||

| Big city | 30 (10) | 16 (15) | 25 (13) | 17 (18) | ||

| Suburb | 110 (38) | 36 (33) | 25 (13) | 15 (15) | ||

| Small city/village | 113 (39) | 44 (40) | 76 (38) | 35 (36) | ||

| Rural area | 34 (12) | 14 (13) | 71 (37) | 30 (31) | ||

| Mean child age at diagnosis in months (±SD) | 55.5 (±23.5) | 60.4 (±23.5) | 0.22 | 47.9 (±18.5) | 48.6 (±18.6) | 0.99 |

| Mean child age at first form submission (±SD) | 62.7 (±23.2) | 65.2 (±22.9) | 0.49 | 56.7 (±18.2) | 55.0 (±18.7) | 0.52 |

| Mean maternal age at diagnosis in years (±SD) | 35.9 (±4.9) | 35.7 (±5.3) | 0.49 | 35.3 (±4.9) | 34.7 (±4.9) | 0.28 |

| Mean paternal age at diagnosis in years (±SD) | 38.8 (±5.4) | 38.8 (±8.0) | 0.96 | 37.8 (±5.7) | 38.8 (±7.2) | 0.48 |

| Highest degree of maternal education (%) | 0.10 | 0.17 | ||||

| Primary education–some trade school | 51 (18) | 22 (20) | 34 (17) | 18 (19) | ||

| Graduated trade school or some college | 49 (17) | 26 (24) | 29 (15) | 22 (23) | ||

| Graduated college or higher degree | 188 (65) | 58 (52) | 56 (58) | 134 (67) | ||

| Missing Data | 2 (1) | 4 (4) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Highest degree of paternal education | 0.33 | 0.27 | ||||

| Primary education–some trade school | 76 (26) | 35 (32) | 49 (25) | 30 (31) | ||

| Graduated trade school or some college | 68 (24) | 21 (19) | 48 (24) | 17 (18) | ||

| Graduated college or higher degree | 142 (49) | 47 (43) | 99 (50) | 46 (47) | ||

| Missing Data | 4 (1) | 7 (6) | 3 (2) | 4 (4) | ||

| Comorbid Type 1 DM (%) | 6 (2) | 5 (5) | 0.16 | 2 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.24 |

| First degree relative with celiac disease (%) | 60 (21) | 14 (13) | 0.04 | 47 (24) | 13 (13) | 0.04 |

| Presence of GI symptoms (%) | 104 (36) | 57 (52) | 0.03 | 74 (37) | 39 (40) | 1 |

| Presence of non-GI symptoms (%) | 10 (3) | 3 (3) | 1 | 6 (3) | 3 (3) | 1 |

Association of adherence with food records

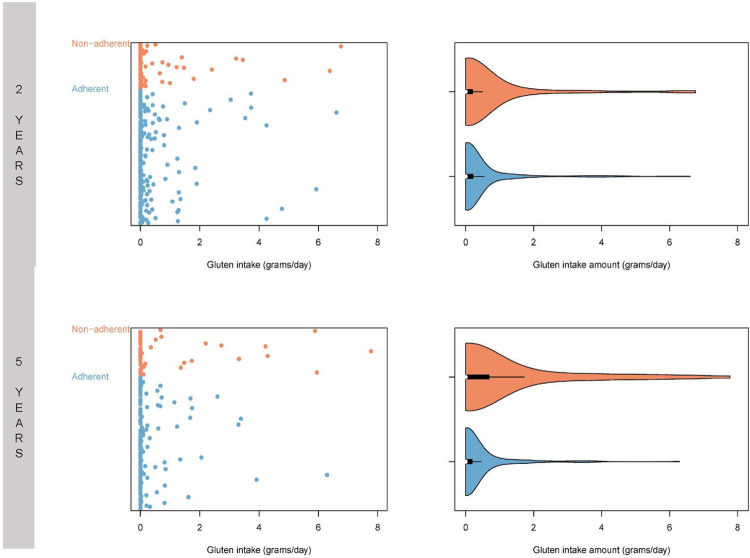

Fig 3 depicts distributions of gluten intake based on 3-day food records at 2 and 5 years post CD diagnosis. There was a skewed distribution of gluten intake. Nonadherent subjects had higher gluten intake using linear regression at 2 years (P < .001) and 5 years (P < .001). At 2 years post CD diagnosis, food records were available for 294 subjects. The 222 adherent subjects had a mean gluten intake of 0.36 ± 0.95 g/day and the 72 nonadherent subjects had a mean intake of 0.55 ±1.35 g/day with median intake of 0.00 (IQR 0.00, 0.22) and 0.00 (IQR 0.00, 0.20) respectively. At 5 years post CD diagnosis, food records were available for 185 subjects. The 138 adherent subjects had a mean gluten intake of 0.32 ± 0.84 g/day and the 47 nonadherent subjects had a higher mean intake of 0.93 ±1.85 g/day with median intake of 0.00 (IQR 0.00, 0.19) and 0.00 (IQR 0.00, 0.69) respectively.

Fig 3. Gluten intake.

Mean gluten-intake based on 3-day food records in subjects adherent and nonadherent to a gluten-free diet at 2 and 5 years post the diagnosis of celiac disease. One slice of white bread is roughly equivalent to 2 grams of gluten [30].

Variations by country

Mean gluten intake among countries differed in both adherent and nonadherent subjects at 2 years post CD diagnosis (P < .001 and P < .001 respectively) with subjects from the US having higher gluten intake (Table 2). This persisted after removing Germany from the analysis due to small sample size (P < .001 and P = .004 respectively). At 5 years post diagnosis of CD, there were significant differences in gluten intake among countries in adherent subjects (P = .007) with subjects from the US having higher gluten intake (Table 2). This was not noted in nonadherent subjects (P = .19). This persisted if Germany was removed from the analysis due to small sample size (P = .03 for adherent subjects and P = .16 in nonadherent subjects).

Table 2. Country level gluten-intake.

Gluten-intake based on 3-day food records, stratified by country and parent-reported adherence.

| 2 years post diagnosis of celiac disease | |||

| Country | Mean gluten intake in g/day (±SD) | Median gluten intake in g/day (IQR) | |

| Adherent | Finland (N = 27) | 0.13 (±0.29) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.11) |

| Germany (N = 1) | 2.27 (±2.83) | 1.30 (0.08, 3.91) | |

| Sweden (N = 121) | 0.26 (±0.77) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.09) | |

| United States (N = 67) | 0.42 (±0.87) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.36) | |

| Nonadherent | Finland (N = 9) | 0.38 (±1.07 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Germany (N = 7) | 0.65 (NA) | 0.65 (0.65, 0.65) | |

| Sweden (N = 38) | 0.16 (±0.80) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | |

| United States (N = 24) | 1.22 (±1.87) | 0.45 (0.10, 1.41) | |

| 5 years post diagnosis of celiac disease | |||

| Country | Mean gluten intake in g/day (±SD) | Median gluten intake in g/day (IQR) | |

| Adherent | Finland (N = 15) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Germany (N = 4) | 2.75 (2.90) | 2.36 (0.61, 4.51) | |

| Sweden (N = 81) | 0.21 (0.46) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.11) | |

| United States (N = 38) | 0.41 (0.87) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.22) | |

| Nonadherent | Finland (N = 6) | 0.12 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.09) |

| Germany (N = 1) | 1.36 (NA) | 1.36 (1.36, 1.36) | |

| Sweden (N = 25) | 0.68 (1.45) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.35) | |

| United States (N = 15) | 1.65 (2.59) | 0.12 (0.00, 2.85) | |

Discussion

Lifelong adherence to a GFD is the only available treatment for CD yet little is known regarding long-term dietary patterns of people with CD. In this study, we aimed to describe long-term adherence rates in children with screening-detected CD, explore factors related to adherence, and determine the association between parent-reported adherence and gluten intake based on food records. We found that nearly three-quarters of children with screening-detected CD reported maintaining strict adherence to a GFD, clinical characteristics did not distinguish adherent from nonadherent subjects, and children from the US had higher gluten intake based on 3-day food records.

Adherence rates

Adherence to a GFD varies between 23% to 98% depending on the definition of adherence used and method of assessment [14] with comparable adherence rates found in screening detected CD patients [31, 32]. GFD adherence in screening detected patients has been a source of controversy with some arguing that universal screening for CD may lead to poorer adherence rates [33–36]. In this study, we found relatively high rates of long-term GFD adherence with only one-quarter and one-third of subjects reporting any major lapses in adherence at 2 and 5 years post the diagnosis of CD. In fact, our findings support previous research showing that earlier childhood diagnosis may in fact lead to improved GFD adherence [37, 38]. Children with a first-degree family member with CD were more likely to be adherent, perhaps due to easily accessible gluten-free foods at home. On the contrary, nonadherent subjects were more likely to report gastrointestinal symptoms which may be reflective of ongoing gluten exposure. Finally, we noted that the percentage of children with variable adherence rates increased from 1% at 2 years to 15% at 5 years. There evidence suggesting that dietary habits established in childhood will persist into to adulthood [39, 40], and that lifestyle patterns in childhood are also persistent [41]. Although 5 years is a relatively short time in the lifespan of a child, we are hopeful that the 5 year adherence data in this study may reflect eating habits and lifestyle choices such as reading labels and eating out, and thus may be representative of future adherence patterns in children. While there is limited data on longitudinal adherence rates in celiac disease specifically, it is important to note that studies examining adherence to healthy diets in weight loss have found increasing difficulty in sustained adherence [42]. Because pediatric patients with celiac disease are frequently lost to follow up [43], and those that are lost to follow have poorer GFD adherence [21, 22], our findings reinforce that not only is regular follow up throughout childhood and adolescence is needed but also that there should be continued assessment of evolving barriers to GFD adherence.

Gluten exposure based on food records

Although nonadherent subjects had more gluten intake than adherent subjects, gluten intake was minimal in most individuals based on median values. The data once again was skewed (Fig 3) with some individuals taking 6 to 7 grams of gluten per day (approximately 3–3.5 slices of white bread per day) [30]. This may be due to intentional intake or an inadequate understanding of the diet [44]. While our study did not measure cross-contamination, the recently published DOGGIE BAG study showed that unintentional gluten intake is common and frequently measured noninvasive measures of gluten intake such as tTGA levels do not correlate with gluten-exposure in individuals with self-reported strict adherence [45]. Prior literature has also shown that self-report or other standardized measures of adherence do not always correlate well with histologic healing [46, 47]. Thus our findings in conjunction with the literature suggest that current adherence assessments and disease monitoring guidelines for children inadequately assess gluten exposure and disease activity.

Country variations in gluten exposure

While no country level differences in reported adherence rates were noted, subjects from the US had significantly more gluten intake from food records. This may be due to several reasons. First, visits with a dietitian are not universally covered by insurances in the US. While the National Institute of Health Consensus on CD recommends consultation from a skilled dietitian [48], studies have shown that many patients with CD have not seen a dietitian or have only seen a dietitian once [49, 50]. Second, GFD foods are more costly than their counterparts [51] and countries have varying approaches to allocating resources to people with CD [52] which may affect people’s ability to buy gluten-free foods. For example, some children in Sweden are provided a $5,000 stipend to help offset food-associated costs of CD [53]. Third, European countries enacted gluten-free labeling laws earlier than the United States [54, 55]. Finally, cultural differences in eating habits such as food content of a traditional diet, frequency of dining out [56] and reliance on processed foods [57] may play a role.

There are several limitations to this study. All subjects in this study are considered to have screening-detected celiac disease. While it is possible that some tTGA positive children would have developed symptoms and likely be diagnosed shortly after seroconversion, prior work has shown that over 50% of children with screening detected celiac disease have symptoms [31] and that severity of symptoms prior to diagnosis do not affect adherence [58]. Twenty-six percent of subjects dropped out of the study between 2 and 5 years after diagnosis. This is common in prospective cohort studies and may be due to subject factors (such moving etc.) or due to the burden placed on subjects in the TEDDY study (frequent blood draws, questionnaires, and research visits) [59]. While there is potential to have a biased sample due to this, this is still the largest prospective study measuring adherence to a GFD in screening-identified children with CD and the only study to directly compare intake across countries. Second, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all children with comorbid CD and type 1 diabetes. Subjects in the TEDDY study are withdrawn from TEDDY when they develop diabetes. Thus, the subjects in our study with diabetes developed it after CD onset. Because type 1 diabetes usually precedes the diagnosis of CD [60, 61], our population is not representative of the typical population of children with comorbid diabetes and CD. Third, we did not quantify and compare tTGA levels of all subjects. All TEDDY studies use Bristol tTGA RIA levels which includes both tissue transglutaminase IgA and IgG. RIA has been shown to remain positive in over 50% of children 5 years after initiating a GFD [62] and levels can remain high even in treated children with normal intestinal mucosa [63]. Furthermore, with the exception of IgA deficiency, IgG autoantibodies are not routinely recommended in the diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease [18]. Because negative serology is not correlated with adherence assessment by a registered dietitian [64], symptomatology [65], or indicative of mucosal healing [18], we do not feel this detracts from the study. The 3-day food records that were used to determine the gluten content of foods were based on parent-report. Although subjects were trained on these and were advised to report 2 weekdays and 1 weekend, we cannot be sure they are representative of normal eating patterns. Finally, we relied on parent report for adherence assessments. While it may not be an accurate reflection of child intake, this is what is commonly done in clinical practice, no standardized adherence measure exists for the pediatric population, and validated adult indices are not applicable internationally.

Conclusions

In this large multinational prospective cohort study of screening-identified children with CD, we found that 73% and 67% of subjects reported strict adherence to a GFD at 2 and 5 years after the diagnosis of CD, the proportion of subjects with variable adherence increased over time, and that there were no distinguishing features of adherent and nonadherent subjects aside from having a first degree family member with CD. We also found that both adherent and nonadherent subjects had portions of subjects eating large quantities of gluten, suggesting that better markers of adherence are needed. Determination of sources of gluten exposure, particularly in the US, is warranted. Finally, future studies regarding the effects of adherence on mucosal healing and diseases outcomes are needed.

Acknowledgments

The TEDDY Study Group

Colorado Clinical Center: Marian Rewers, M.D., Ph.D., PI1,4,6,9,10, Aaron Barbour, Kimberly Bautista11, Judith Baxter8,911, Daniel Felipe-Morales, Brigitte I. Frohnert, M.D.2,13, Marisa Stahl, M.D.12, Patricia Gesualdo2,6,11,13, Michelle Hoffman11,12,13, Rachel Karban11, Edwin Liu, M.D.12, Alondra Munoz, Jill Norris, Ph.D.2,3,11, Holly O’Donnell, Ph.D.8, Stesha Peacock, Hanan Shorrosh, Andrea Steck, M.D.3,13, Megan Stern11, Kathleen Waugh6,7,11. University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes.

Finland Clinical Center: Jorma Toppari, M.D., Ph.D., PI¥^1,4,10,13, Olli G. Simell, M.D., Ph.D., Annika Adamsson, Ph.D.^11, Sanna-Mari Aaltonen^, Suvi Ahonen*±§, Mari Åkerlund*±§, Leena Hakola*±, Anne Hekkala, M.D.μ¤, Henna Holappaμ¤, Heikki Hyöty, M.D., Ph.D.*±6, Anni Ikonenμ¤, Jorma Ilonen, M.D., Ph.D.¥¶3, Sanna Jokipuu^, Leena Karlsson^, Jukka Kero M.D., Ph.D.¥^3, 13, Jaakko J. Koskenniemi M.D., Ph.D.¥^, Miia Kähönenμ¤11,13, Mikael Knip, M.D., Ph.D.*±, Minna-Liisa Koivikkoμ¤, Katja Kokkonen*±, Merja Koskinen*±, Mirva Koreasalo*±§2, Kalle Kurppa, M.D., Ph.D.*±12, Salla Kuusela, M.D.* ±, Jarita Kytölä*±, Jutta Laiho, Ph.D.*6, Tiina Latva-ahoμ¤, Laura Leppänen^, Katri Lindfors, Ph.D.*12, Maria Lönnrot, M.D., Ph.D.*±6, Elina Mäntymäki^, Markus Mattila*±, Maija Miettinen§2, Katja Multasuoμ¤, Teija Mykkänenμ¤, Tiina Niininen±*11, Sari Niinistö§2, Mia Nyblom*±, Sami Oikarinen, Ph.D.*±6, Paula Ollikainenμ¤, Zhian Othmani¥, Sirpa Pohjola μ¤, Jenna Rautanen±§, Anne Riikonen*±§2, Minna Romo^, Satu Simell, M.D., Ph.D.¥12, Päivi Tossavainen, M.D.μ¤, Mari Vähä-Mäkilä¥, Eeva Varjonen^11, Riitta Veijola, M.D., Ph.D.μ¤13, Irene Viinikangasμ¤, Suvi M. Virtanen, M.D., Ph.D.*±§2. ¥University of Turku, *Tampere University, μUniversity of Oulu, ^Turku University Hospital, Hospital District of Southwest Finland, ±Tampere University Hospital, ¤Oulu University Hospital, §Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland, ¶University of Kuopio.

Georgia/Florida Clinical Center: Desmond Schatz, M.D.*4,7,8, Diane Hopkins11, Leigh Steed11,12,13, Jennifer Bryant11, Katherine Silvis2, Michael Haller, M.D.*13, Melissa Gardiner11, Richard McIndoe, Ph.D., Ashok Sharma, Stephen W. Anderson, M.D.^, Laura Jacobsen, M.D.*13, John Marks, DHSc.*11,13, P.D. Towe*. Center for Biotechnology and Genomic Medicine, Augusta University. *University of Florida, Pediatric Endocrinology. ^Pediatric Endocrine Associates, Atlanta.

Germany Clinical Center: Anette G. Ziegler, M.D., PI1,3,4,10, Ezio Bonifacio Ph.D.*, Cigdem Gezginci, Anja Heublein, Eva Hohoff¥2, Sandra Hummel, Ph.D.2, Annette Knopff7, Charlotte Koch, Sibylle Koletzko, M.D.¶12, Claudia Ramminger11, Roswith Roth, Ph.D.8, Jennifer Schmidt, Marlon Scholz, Joanna Stock8,11,13, Katharina Warncke, M.D.13, Lorena Wendel, Christiane Winkler, Ph.D.2,11. Forschergruppe Diabetes e.V. and Institute of Diabetes Research, Helmholtz Zentrum München, Forschergruppe Diabetes, and Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität München. *Center for Regenerative Therapies, TU Dresden, ¶Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Ludwig Maximillians University Munich, ¥University of Bonn, Department of Nutritional Epidemiology.

Sweden Clinical Center: Åke Lernmark, Ph.D., PI1,3,4,5,6,8,9,10, Daniel Agardh, M.D., Ph.D.6,12, Carin Andrén Aronsson, Ph.D.2,11,12, Rasmus Bennet, Corrado Cilio, Ph.D., M.D.6, Susanne Dahlberg, Ulla Fält, Malin Goldman Tsubarah, Emelie Ericson-Hallström, Lina Fransson, Thomas Gard, Emina Halilovic, Gunilla Holmén, Susanne Hyberg, Berglind Jonsdottir, M.D., Ph.D.11, Naghmeh Karimi, Helena Elding Larsson, M.D., Ph.D.6,13, Marielle Lindström, Markus Lundgren, M.D., Ph.D.13, Marlena Maziarz, Ph.D., Maria Månsson Martinez, Jessica Melin11, Zeliha Mestan, Caroline Nilsson, Yohanna Nordh, Kobra Rahmati, Anita Ramelius, Falastin Salami, Anette Sjöberg, Carina Törn, Ph.D.3, Ulrika Ulvenhag, Terese Wiktorsson, Åsa Wimar13. Lund University.

Washington Clinical Center: William A. Hagopian, M.D., Ph.D., PI1,3,4,6,7,10,12,13, Michael Killian6,7,11,12, Claire Cowen Crouch11,13, Jennifer Skidmore2, Luka-Sophia Bowen, Mikeil Metcalf, Arlene Meyer, Jocelyn Meyer, Denise Mulenga11, Nole Powell, Jared Radtke, Shreya Roy, Davey Schmitt, Preston Tucker. Pacific Northwest Research Institute.

Pennsylvania Satellite Center: Dorothy Becker, M.D., Margaret Franciscus, MaryEllen Dalmagro-Elias Smith2, Ashi Daftary, M.D., Mary Beth Klein, Chrystal Yates. Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC.

Data Coordinating Center: Jeffrey P. Krischer, Ph.D., PI1,4,5,9,10, Rajesh Adusumali, Sarah Austin-Gonzalez, Maryouri Avendano, Sandra Baethke, Brant Burkhardt, Ph.D.6, Martha Butterworth2, Nicholas Cadigan, Joanna Clasen, Kevin Counts, Laura Gandolfo, Jennifer Garmeson, Veena Gowda, Christina Karges, Shu Liu, Xiang Liu, Ph.D.2,3,8,13, Kristian Lynch, Ph.D. 6,8, Jamie Malloy, Lazarus Mramba, Ph.D.2, Cristina McCarthy11, Jose Moreno, Hemang M. Parikh, Ph.D.3,8, Cassandra Remedios, Chris Shaffer, Susan Smith11, Noah Sulman, Ph.D., Roy Tamura, Ph.D.1,2,11,12,13, Dena Tewey, Michael Toth, Ulla Uusitalo, Ph.D.2, Kendra Vehik, Ph.D.4,5,6,8,13, Ponni Vijayakandipan, Melissa Wroble, Jimin Yang, Ph.D., R.D.2, Kenneth Young, Ph.D. Past staff: Michael Abbondondolo, Lori Ballard, Rasheedah Brown, David Cuthbertson, Stephen Dankyi, Christopher Eberhard, Steven Fiske, David Hadley, Ph.D., Kathleen Heyman, Belinda Hsiao, Francisco Perez Laras, Hye-Seung Lee, Ph.D., Qian Li, Ph.D., Colleen Maguire, Wendy McLeod, Aubrie Merrell, Steven Meulemans, Ryan Quigley, Laura Smith, Ph.D. University of South Florida.

Project scientist: Beena Akolkar, Ph.D.1,3,4,5,6,7,9,10. National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Autoantibody Reference Laboratories: Liping Yu, M.D.^5, Dongmei Miao, M.D.^, Kathleen Gillespie*5, Kyla Chandler*, Ilana Kelland*, Yassin Ben Khoud*, Matthew Randell *. ^Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes, University of Colorado Denver, *Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, UK.

HLA Reference Laboratory: William Hagopian3, M.D., Ph.D., Jared Radtke, Preston Tucker. Pacific Northwest Research Institute, Seattle WA. (Previously Henry Erlich, Ph.D.3, Steven J. Mack, Ph.D., Anna Lisa Fear. Center for Genetics, Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute.)

Repository: Sandra Ke, Niveen Mulholland, Ph.D. NIDDK Biosample Repository at Fisher BioServices.

Other contributors: Thomas Briese, Ph.D.6, Columbia University. Todd Brusko, Ph.D.5, University of Florida. Suzanne Bennett Johnson, Ph.D.8,11, Florida State University. Eoin McKinney, Ph.D.5, University of Cambridge. Tomi Pastinen, M.D., Ph.D.5, The Children’s Mercy Hospital. Eric Triplett, Ph.D.6, University of Florida.

Committees:

1Ancillary Studies, 2Diet, 3Genetics, 4Human Subjects/Publicity/Publications, 5Immune Markers, 6Infectious Agents, 7Laboratory Implementation, 8Psychosocial, 9Quality Assurance, 10Steering, 11Study Coordinators, 12Celiac Disease, 13Clinical Implementation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the NIDDK Central Repository at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/studies/teddy. 1. There are no legal or ethical restrictions on the data. 2. The data has been submitted to the NIDDK Central Repository. 3. All data inquires will be handled by NIDDK staff (NIDDK-CRsupport@niddk.nih.gov).

Funding Statement

The TEDDY Study is funded by U01 DK63829, U01 DK63861, U01 DK63821, U01 DK63865, U01 DK63863, U01 DK63836, U01 DK63790, UC4 DK63829, UC4 DK63861, UC4 DK63821, UC4 DK63865, UC4 DK63863, UC4 DK63836, UC4 DK95300, UC4 DK100238, UC4 DK106955, UC4 DK112243, UC4 DK117483, U01 DK124166, U01 DK128847, and Contract No. HHSN267200700014C from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and JDRF. This work is supported in part by the NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Awards to the University of Florida (UL1 TR000064) and the University of Colorado (UL1 TR002535). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Singh P, Arora A, Strand TA, Leffler DA, Catassi C, Green PH, et al. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(6):823–36 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts SE, Morrison-Rees S, Thapar N, Benninga MA, Borrelli O, Broekaert I, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: the incidence and prevalence of paediatric coeliac disease across Europe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(2):109–28. doi: 10.1111/apt.16337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahin Y. Celiac disease in children: A review of the literature. World J Clin Pediatr. 2021;10(4):53–71. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v10.i4.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, Laurila K, Collin P, Rissanen H, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(9):1217–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03502.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King JA, Jeong J, Underwood FE, Quan J, Panaccione N, Windsor JW, et al. Incidence of Celiac Disease Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(4):507–25. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makharia GK, Catassi C. Celiac Disease in Asia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2019;48(1):101–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makharia GK, Singh P, Catassi C, Sanders DS, Leffler D, Ali RAR, et al. The global burden of coeliac disease: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(5):313–27. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00552-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill ID, Fasano A, Guandalini S, Hoffenberg E, Levy J, Reilly N, et al. NASPGHAN Clinical Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gluten-related Disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63(1):156–65. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabo I, Kurppa K, Mearin ML, Ribes-Koninckx C, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70(1):141–56. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen MA, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Gaillard R, Escher JC, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW, et al. Growth trajectories and bone mineral density in anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody-positive children: the Generation R Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(5):913–20 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wierdsma NJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, Berkenpas M, Mulder CJ, van Bodegraven AA. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are highly prevalent in newly diagnosed celiac disease patients. Nutrients. 2013;5(10):3975–92. doi: 10.3390/nu5103975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lionetti E, Francavilla R, Pavone P, Pavone L, Francavilla T, Pulvirenti A, et al. The neurology of coeliac disease in childhood: what is the evidence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(8):700–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butwicka A, Lichtenstein P, Frisen L, Almqvist C, Larsson H, Ludvigsson JF. Celiac Disease Is Associated with Childhood Psychiatric Disorders: A Population-Based Study. J Pediatr. 2017;184:87–93 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myleus A, Reilly NR, Green PHR. Rate, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Nonadherence in Pediatric Patients With Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(3):562–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nikniaz Z, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Abbasalizad Farhangi M, Shirmohammadi M, Nikniaz L. Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with celiac disease: a structural equation modeling. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12955-021-01842-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moller SP, Apputhurai P, Tye-Din JA, Knowles SR. Quality of life in coeliac disease: relationship between psychosocial processes and quality of life in a sample of 1697 adults living with coeliac disease. J Psychosom Res. 2021;151:110652. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bai JC, Ciacci C. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines: Celiac Disease February 2017. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(9):755–68. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Monitoring of Celiac Disease-Changing Utility of Serology and Histologic Measures: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):885–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herman ML, Rubio-Tapia A, Lahr BD, Larson JJ, Van Dyke CT, Murray JA. Patients with celiac disease are not followed up adequately. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(8):893–9 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mozer-Glassberg Y, Zevit N, Rosenbach Y, Hartman C, Morgenstern S, Shamir R. Follow-up of children with celiac disease—lost in translation? Digestion. 2011;83(4):283–7. doi: 10.1159/000320714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnea L, Mozer-Glassberg Y, Hojsak I, Hartman C, Shamir R. Pediatric celiac disease patients who are lost to follow-up have a poorly controlled disease. Digestion. 2014;90(4):248–53. doi: 10.1159/000368395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiepatti A, Maimaris S, de Queiros Mattoso Archela Dos Santos C, Rusca G, Costa S, Biagi F. Long-Term Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet and Quality of Life of Celiac Patients After Transition to an Adult Referral Center. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(8):3955–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Group TS. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study: study design. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(5):286–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Group TS. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1150:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vehik K, Fiske SW, Logan CA, Agardh D, Cilio CM, Hagopian W, et al. Methods, quality control and specimen management in an international multicentre investigation of type 1 diabetes: TEDDY. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2013;29(7):557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rewers M, Hyoty H, Lernmark A, Hagopian W, She JX, Schatz D, et al. The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study: 2018 Update. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(12):136. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1113-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andren Aronsson C, Lee HS, Koletzko S, Uusitalo U, Yang J, Virtanen SM, et al. Effects of Gluten Intake on Risk of Celiac Disease: A Case-Control Study on a Swedish Birth Cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(3):403–9 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang J, Lynch KF, Uusitalo UM, Foterek K, Hummel S, Silvis K, et al. Factors associated with longitudinal food record compliance in a paediatric cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(5):804–13. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joslowski G, Yang J, Aronsson CA, Ahonen S, Butterworth M, Rautanen J, et al. Development of a harmonized food grouping system for between-country comparisons in the TEDDY Study. J Food Compost Anal. 2017;63:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2017.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andren Aronsson C, Lee HS, Hard Af Segerstad EM, Uusitalo U, Yang J, Koletzko S, et al. Association of Gluten Intake During the First 5 Years of Life With Incidence of Celiac Disease Autoimmunity and Celiac Disease Among Children at Increased Risk. JAMA. 2019;322(6):514–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.10329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kivela L, Kaukinen K, Huhtala H, Lahdeaho ML, Maki M, Kurppa K. At-Risk Screened Children with Celiac Disease are Comparable in Disease Severity and Dietary Adherence to Those Found because of Clinical Suspicion: A Large Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2017;183:115–21 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webb C, Myleus A, Norstrom F, Hammarroth S, Hogberg L, Lagerqvist C, et al. High adherence to a gluten-free diet in adolescents with screening-detected celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(1):54–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popp A, Kivela L, Fuchs V, Kurppa K. Diagnosing Celiac Disease: Towards Wide-Scale Screening and Serology-Based Criteria? Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:2916024. doi: 10.1155/2019/2916024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludvigsson JF, Card TR, Kaukinen K, Bai J, Zingone F, Sanders DS, et al. Screening for celiac disease in the general population and in high-risk groups. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3(2):106–20. doi: 10.1177/2050640614561668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fabiani E, Taccari LM, Ratsch IM, Di Giuseppe S, Coppa GV, Catassi C. Compliance with gluten-free diet in adolescents with screening-detected celiac disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Pediatr. 2000;136(6):841–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kivela L, Kurppa K. Screening for coeliac disease in children. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107(11):1879–87. doi: 10.1111/apa.14468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogberg L, Grodzinsky E, Stenhammar L. Better dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease diagnosed in early childhood. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(7):751–4. doi: 10.1080/00365520310003318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charalampopoulos D, Panayiotou J, Chouliaras G, Zellos A, Kyritsi E, Roma E. Determinants of adherence to gluten-free diet in Greek children with coeliac disease: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(6):615–9. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mikkila V, Rasanen L, Raitakari OT, Pietinen P, Viikari J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: the cardiovascular risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(6):923–31. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Movassagh EZ, Baxter-Jones ADG, Kontulainen S, Whiting SJ, Vatanparast H. Tracking Dietary Patterns over 20 Years from Childhood through Adolescence into Young Adulthood: The Saskatchewan Pediatric Bone Mineral Accrual Study. Nutrients. 2017;9(9). doi: 10.3390/nu9090990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lioret S, Campbell KJ, McNaughton SA, Cameron AJ, Salmon J, Abbott G, et al. Lifestyle Patterns Begin in Early Childhood, Persist and Are Socioeconomically Patterned, Confirming the Importance of Early Life Interventions. Nutrients. 2020;12(3). doi: 10.3390/nu12030724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(1):183–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blansky BA, Hintze ZJ, Alhassan E, Leichtner AM, Weir DC, Silvester JA. Lack of Follow-up of Pediatric Patients With Celiac Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(12):2603–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silvester JA, Weiten D, Graff LA, Walker JR, Duerksen DR. Is it gluten-free? Relationship between self-reported gluten-free diet adherence and knowledge of gluten content of foods. Nutrition. 2016;32(7–8):777–83. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silvester JA, Comino I, Kelly CP, Sousa C, Duerksen DR, Group DBS. Most Patients With Celiac Disease on Gluten-Free Diets Consume Measurable Amounts of Gluten. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1497–9 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biagi F, Andrealli A, Bianchi PI, Marchese A, Klersy C, Corazza GR. A gluten-free diet score to evaluate dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(6):882–7. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509301579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gladys K, Dardzinska J, Guzek M, Adrych K, Malgorzewicz S. Celiac Dietary Adherence Test and Standardized Dietician Evaluation in Assessment of Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in Patients with Celiac Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(8). doi: 10.3390/nu12082300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Celiac Disease, June 28–30, 2004. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Suppl 1):S1–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mahadev S, Simpson S, Lebwohl B, Lewis SK, Tennyson CA, Green PH. Is dietitian use associated with celiac disease outcomes? Nutrients. 2013;5(5):1585–94. doi: 10.3390/nu5051585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faye AS, Mahadev S, Lebwohl B, Green PHR. Determinants of Patient Satisfaction in Celiac Disease Care. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(1):30–5. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh J, Whelan K. Limited availability and higher cost of gluten-free foods. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24(5):479–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson LD, Idler WW, Zhou XM, Roop DR, Steinert PM. Structure of a gene for the human epidermal 67-kDa keratin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(7):1896–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.7.1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ludvigsson JF, Card T, Ciclitira PJ, Swift GL, Nasr I, Sanders DS, et al. Support for patients with celiac disease: A literature review. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3(2):146–59. doi: 10.1177/2050640614562599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gluten-Free Food: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/food/food/labelling-and-nutrition/foods-specific-groups/gluten-free-food_en. Accessed July 9, 2021.

- 55.USDA Gluten and Food Labeling. https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-education-resources-materials/gluten-and-food-labeling. Accessed July 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saad L. American’s Dining-Out Frequency Little Changed from 2008. https://news.gallup.com/poll/201710/americans-dining-frequency-little-changed-2008.aspx. Accessed June 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weaver CM, Dwyer J, Fulgoni VL 3rd, King JC, Leveille GA, MacDonald RS, et al. Processed foods: contributions to nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1525–42. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.089284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kurppa K, Lauronen O, Collin P, Ukkola A, Laurila K, Huhtala H, et al. Factors associated with dietary adherence in celiac disease: a nationwide study. Digestion. 2012;86(4):309–14. doi: 10.1159/000341416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Szklo M. Population-based cohort studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20(1):81–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cerutti F, Bruno G, Chiarelli F, Lorini R, Meschi F, Sacchetti C, et al. Younger age at onset and sex predict celiac disease in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: an Italian multicenter study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1294–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pham-Short A, Donaghue KC, Ambler G, Phelan H, Twigg S, Craig ME. Screening for Celiac Disease in Type 1 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):e170–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Candon S, Mauvais FX, Garnier-Lengline H, Chatenoud L, Schmitz J. Monitoring of anti-transglutaminase autoantibodies in pediatric celiac disease using a sensitive radiobinding assay. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54(3):392–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318232c459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Agardh D, Dahlbom I, Daniels T, Lorinc E, Ivarsson SA, Lernmark A, et al. Autoantibodies against soluble and immobilized human recombinant tissue transglutaminase in children with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41(3):322–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000174845.90668.fa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mehta P, Pan Z, Riley MD, Liu E. Adherence to a Gluten-free Diet: Assessment by Dietician Interview and Serology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(3):e67–e70. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leffler D, Schuppan D, Pallav K, Najarian R, Goldsmith JD, Hansen J, et al. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut. 2013;62(7):996–1004. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the NIDDK Central Repository at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/studies/teddy. 1. There are no legal or ethical restrictions on the data. 2. The data has been submitted to the NIDDK Central Repository. 3. All data inquires will be handled by NIDDK staff (NIDDK-CRsupport@niddk.nih.gov).