Abstract

Objective

To develop a set of patient and family engagement indicators (PFE-Is) for measuring engagement in health system improvement for a Canadian provincial health delivery system through an evidence-based consensus approach.

Design

This mixed-method, multiphase project included: (1) identification of existing measures of patient and family engagement through a review of the literature and consultations with a diverse provincial council of patients, caregivers, community members and researchers. The Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET) was selected; (2) consultations on relevance, acceptability and importance with patient and family advisors, and staff members of Alberta Health Services’ Strategic Clinical Networks. This phase included surveys and one-on-one semi-structured interviews aimed to further explore the use of PPEET in this context. Findings from the survey and interviews informed the development of PFE-Is; (3) a Delphi consensus process using a modified RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method to identify and refine a core set of PFE-Is.

Participants

The consensus panel consisted of patients, family members, community representatives, clinicians, researchers and healthcare leadership.

Results

From an initial list of 33 evidence-based PFE-Is identified, the consensus process yielded 18 final indicators. These PFE-Is were grouped into seven themes: communication, comfort to contribute, support needed for engagement, impact and influence of engagement initiative, diversity of perspectives, respectful engagement, and working together indicators.

Conclusions

This group of final patient, family and health system leaders informed indicators can be used to measure and evaluate meaningful engagement in health research and system transformation. The use of these metrics can help to improve the quality of patient and family engagement to drive health research and system transformation.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, COVID-19

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The consensus process used a participatory approach, by engaging diverse groups of experienced stakeholders, including patient and community advisors and health system staff and leadership.

We used a modified Delphi consensus process to co-develop a set of indicators to measure patient engagement in health research and system transformation for a provincial health system.

This particular specific set of indicators has not yet been validated or implemented.

Background

Person-centred health system improvement and transformation requires the involvement of patients and families to shape system priorities and inform care delivery and outcomes.1 Recent evidence has shown that engaging patients in health system transformation can enhance service delivery and drive system improvement.2

While there have been efforts to advance patient engagement in health research and health system transformation, there are currently few co-developed, system-embedded sets of indicators to evaluate patient engagement and its impact on this transformation.

Alberta Health Services (AHS) is the largest province-wide health delivery system authority in the Canadian province of Alberta.3 Within AHS, the Strategic Clinical Networks (SCNs) address system-wide gaps in care, work together to get evidence into practice, improve patient outcomes and experience and to support continuous quality improvement.4 The SCNs are multistakeholder teams that are comprised of clinicians, patient and family advisors (PFAs), operational leaders, researchers, policymakers and community partners.4 5

As of June 2022, the 11 SCNs aim to advance improvements in specific areas of health: (1) Bone and Joint Health, (2) Cancer, (3) Cardiovascular Health and Stroke, (4) Critical Care, (5) Diabetes, Obesity and Nutrition, (6) Digestive Health, (7) Emergency, (8) Maternal Newborn Child and Youth, (9) Medicine, (10) Neurosciences, Rehabilitation and Vision and (11) Surgery; and within 5 Integrated Provincial programmes: (1) Addiction and Mental Health, (2) Seniors and Continuing Care, (3) Primary Healthcare, (4) Population and Public Health and (5) Indigenous Wellness Core.

Each SCN works to actively engage patients and families in priority setting and co-designing solutions to improve patient experiences and quality of care. The Patient Engagement Reference Group (PERG) includes patients and public that engaged regularly in quality improvement and research projects within the 11 SCNs and the 5 Provincial Integrated Programmes.6 The current annual survey, deployed by the SCN Patient and Family Engagement team, does not measure patient engagement but rather the overall performance or satisfaction of participation. Additionally, engagement efforts are inconsistent across networks and often uncoordinated.7 Developing indicators will enable AHS and the SCNs to be able to effectively measure patient engagement across networks. These measures will lend themselves to assessing impact with respect to effective engagement of PFAs.

Our objective for this project was to address this gap by developing a set of evidence-based patient and family engagement indicators (PFE-Is) that were informed and prioritised by PFAs in the context of a large and complex fully integrated provincial health system to measure meaningful patient engagement at the system level.

Methods

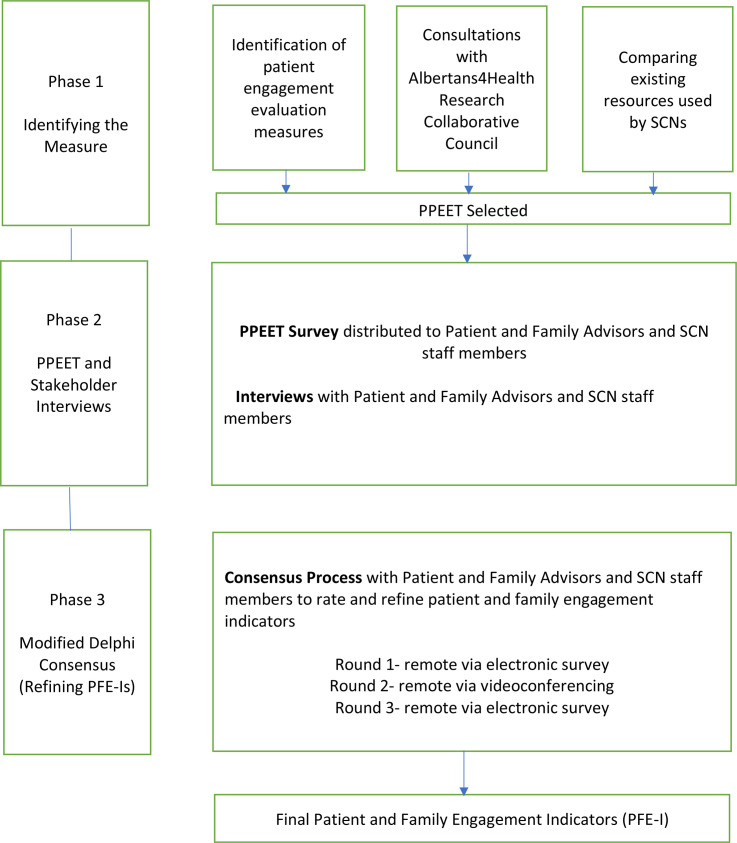

This mixed-method study is a multiphased patient-oriented research study that was informed by recent literature on patient engagement in health systems,8 9 consultations with our provincial network of Albertans (Albertans4HealthResearch Collaborative Council),10 a survey and interviews with AHS SCN staff, leadership and PFAs, followed by a modified Delphi consensus generating process11 to identify indicators to be used by the AHS SCNs to measure patient and family engagement in their initiatives to transform healthcare system in Alberta (figure 1).

Figure 1.

An overview of the programme of research on the development of patient and family engagement indicators. PPEET, Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool; SCN, Strategic Clinical Network.

Patient and public involvement

This study is informed by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Patient Engagement Framework, which states that patients are active partners in health research.12 The four guiding principles of the framework are inclusiveness, support, mutual respect and co-build.12 We consulted with patients and family advisors with diverse lived experience as active collaborators through a participatory approach—doing research ‘with’ rather than ‘on’ them.12 The team included two patient partners, people living with chronic conditions (GW and SZ), both of whom are graduates of the Patient and Community Engagement Research programme13 from the University of Calgary that trains citizens with lived experiences of a health condition how to conduct research projects by, for and with patients. GW and SZ also lead patient engagement groups and have extensive experience working on healthcare research and quality improvement projects and at governance level in the healthcare system.6 14 GW and SZ were involved in the planning of the project through working with the team members, SCN leadership and PERG to design the rollout of the project, providing feedback on the study proposal, co-conducting the project and co-developing the manuscript.

Study participants and recruitment

The study population includes a diverse group of SCN leadership (individuals responsible for the organisational requirements for engagement activities—Scientific Directors, Senior Provincial Directors, Senior Provincial Officers, Senior Medical Directors), SCN Staff (Assistant Scientific Directors, Executive Directors, Managers, Staff Liaisons, Senior Consultants) and PFAs within the SCNs.

Recruitment was supported by members of the research team (GW, MM, JP and TW), working with and leading the AHS SCNs. Participants were invited to complete a survey and semi-structured interview. SCN leadership, SCN staff and PFAs were also invited to participate in a modified Delphi consensus process. Participants are drawn from the same pool for all the phases, however since the survey is anonymous we did not confirm with all interview respondents or Delphi consensus participants whether they completed the survey.

Patient and public involvement: a multiphase approach

The development of these indicators occurred over three phases, each involving significant patient and public engagement.

Phase 1: Selecting the patient and family engagement tool

Phase 2: Stakeholder consultations including a survey and follow-up with interviews

Phase 3: Modified Delphi panel

Phase 1: selecting the measure

This phase includes three steps.

Step 1

We identified patient engagement evaluation measures. A recently published Systematic Review15 identified a number of validated patient engagement evaluation survey tools including; PEIRS (Patient Engagement In Research Scale),16 PPEET (Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool)17 and WE-ENACT (Ways of Engaging- ENgagement ACtivity Tool).18

Step 2

We presented the identified patient engagement evaluation measures to our provincial council, the Albertans4HealthResearch Collaborative Council. Members of the council appreciated the scope and depth of the PPEET, as it captured the evaluation of patient and family engagement from the perspectives of different stakeholders (PFAs, staff members and organisation leaders).17

Step 3

After identifying and selecting the measure, the PPEET was compared with existing PFA engagement measures used by SCNs. This step ensured that existing efforts aligned with the development of the final core of indicators.

PPEET17 includes three types of questionnaires that can be used to assess public and patient engagement in health research and at health system level. The three questionnaires are:

A participant questionnaire for patient partners and staff members on their experiences working together in engagement initiatives. There are two versions available: one evaluating one-time engagements and another evaluating ongoing/long-term engagements.

A project questionnaire that reviews and assesses three components of the process of engagement at health system level including the planning, execution, and impact of the engagement.

An organisation questionnaire assesses how engagement is conducted within organisations.

Questionnaires 1 and 3 of the PPEET were chosen for phase 2 as they aligned best with the purposes of evaluating patient and family engagement within the SCNs.

Phase 2: stakeholder consultations

This phase included two steps, an electronic PPEET survey, and semi-structured interviews with SCN staff, leadership and PFAs.

Step 1

Individuals from SCNs were contacted and invited to complete the PPEET as an anonymous online survey. This survey was populated into Qualtrics software19 for ease of use and widespread distribution. The aim was to assess the use of the PPEET in capturing the experiences of participants in working together within their SCNs; as well as gathering potential barriers and facilitators in engagement in health research and system transformation.

Survey results were descriptively summarised and categorised according to the key areas of engagement: communication and support for participation, sharing your views and perspectives and impacts and influence of the engagement initiative. Frequencies were also reported.

Step 2

After completing the online survey, respondents were invited to a semi-structured interview. Interviews were conducted with a select number of SCN PFAs, leadership and staff members via a video-conferencing platform (eg, Zoom) or by telephone. The purpose of conducting the interviews was for participants to expand on their patient engagement experiences working within the SCNs, and to gain an in-depth understanding of the barriers and facilitators to engagement in health research and system transformation. The interview guide was co-developed with patient and family partners and research team members (online supplemental appendix 1). The semi-structured interviews were conducted by members of the research team (conducted by SZ, GW, SA, TLM, qualitative research background).

bmjopen-2022-067609supp001.pdf (78.9KB, pdf)

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and thematically analysed, with deductive and inductive coding strategies.20 Qualitative researcher (SA) followed the six-step thematic analysis Braun and Clarke method,21 and had peer debriefing sessions at different stages of the analysis with MJS to discuss themes and subthemes identified. After organising codes into themes, they were presented back to the research team for feedback.

PFE-Is were drafted from the PPEET survey and qualitative interviews for the consensus process.

Phase 3: Delphi consensus process

Consensus methods are considered an effective tool for facilitating decision-making when there is insufficient information or when there is contradictory information.22 The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method was used as a guide for the consensus process.11 A consensus panel consisted of a diverse group of 8 PFAs, 5 Scientific Directors and 10 Assistant Scientific Directors/Managers/Staff liaisons.

The consensus process included three rounds. Round 1 was conducted via an electronic survey, round 2 via videoconference and round 3 was completed via an electronic survey.

Round 1

Using a modified Delphi technique,11 panellists ranked each of the PFE-Is criteria according to a 9-point scale scoring as not relevant/to be discarded (1–3); consider more discussion (4–6) and relevant/accepted (7–9). Panellists were also given the opportunity to provide written comments and suggestions. Results from this phase were compiled and shared prior to the virtual face-to face Round 2.

Round 2

The panel and moderators convened over 2 hours via zoom. Moderators shared the results of the first round and facilitated a workshop noting any areas of disagreement indicated by the ratings and answered any questions about the process. The group deliberated, until agreement on the patient and family engagement indicators was achieved. Two research team members took notes to capture modifications made to the indicators and discussions from the consensus meeting. The indicators (after modifications) were presented to the panellists for a final round of voting.

Round 3

The discussed PFE-Is were refined based on the discussions and consensus that happened during Round 2. These PFE-Is were voted on ‘overall importance’ as keep or discard using an electronic survey.

Scale

Panellists used a 9-point rating scale. Ratings of 1–3 indicated not relevant/to be discarded; 4–6 if more discussion was needed; and 7–9 as relevant/accepted. PFE-Is were accepted when 75% of the panellist’s ratings were 7, 8, 9 without disagreement on the scale. Disagreement was declared when five or more than five panellists rated the indicator in the top and bottom parts of the scale (1–3 or 7–9).

The rating criteria provided to the panellists is displayed in table 1. Panellists used these criteria to rate PFE-Is through the Delphi process.

Table 1.

Rating criteria

| Criteria | Definition |

| Overall importance | This overall rating will be used to determine how important it is to measure and track this indicator for patient and family engagement within the SCNs. A high score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, this indicator is very important for measurement of patient and family engagement within the SCNs. A low score on this criterion indicates that the indicator is not as important compared with the other indicators for measuring patient and family engagement within the SCNs. When rating this indicator, consider how important is this indicator to you or your organisation in promoting meaningful patient and family engagement. |

| Impact on patient and family engagement | This rating will be used to determine whether this indicator will have a big impact on the engagement of patients and families within the SCNs. A high score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, this indicator has a big impact on the engagement of patients and families within the SCNs. A low score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, this indicator does not have a big impact on the engagement of patients and families within the SCNs. Improvements on this indicator will mean improved engagement of patient and family advisors. |

| Actionable by SCNs | This indicator reflects an area where improvements can be made. It can provide information to improve the engagement of patient and family advisors. A high score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, there is a big opportunity to change the results for this indicator within the SCNs. A low score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, there is not a big opportunity to change the results for this indicator within the SCNs. This indicator could be measured to improve patient and family engagement within the SCNs, without too much difficulty. |

| Interpretability | This indicator provides clear information that is easy to communicate to stakeholder groups, including patient and family advisors. A high score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, this indicator is easy to communicate to different audiences, with little explanation. A low score on this criterion indicates that compared with other indicators, this indicator is more difficult to communicate to different audiences with little explanations. |

| Relevance | This indicator addresses areas of major importance or concern related to patient and family engagement within the SCNs. A high score on this criterion indicates that the indicator is very relevant to patient and family advisors, and the strategic clinical networks. A low score on this criterion indicates that the indicator is not as relevant as other indicators to patient and family advisors, and the strategic clinical networks. |

SCNs, Strategic Clinical Networks.

Results

The results of the three phases are described by phase.

Phase 1

The Albertans4HealthResearch council members were consulted on which tool to use for measuring patient and family engagement. The criteria for selecting the initial tool was that the tool had to be free to use, relevant, actionable, measure engagement prospectively and from all members of the team and important to assess the engagement in health research and other initiatives informed by patients and family advisors. The council members completed the PPEET to provide their feedback on what was being asked within the survey, and council members found the PPEET met all the criteria.

Phase 2a

The online survey was emailed to 175 PFAs, 69 SCN staff members and 49 SCN leadership members. Among them 96 participants responded, including 51 PFAs, 31 SCN staff and 14 SCN leadership. PFE-Is were then drafted based on the questions from the PPEET survey.

In general, there was some consistency in the responses. Most PFAs agreed/strongly agreed that they:

Have a clear understanding of the purpose of the SCNs they are involved in (94%).

Have supports available to contribute to the SCNs projects (92%)

Have enough information to be able to carry out their role in the specific projects (81%)

Can express their views freely when working in projects (96%)

Are confident the SCNs take the feedback provided by PFAs into consideration (81%)

Similarly, most or all SCN staff agreed/strongly agreed that they:

Have a clear understanding of the purpose of engaging PFAs in the SCNs (100%).

Have supports and information available to effectively engage with PFAs (87%)

Are able to express their views freely (86%)

SCNs take the feedback of PFAs into consideration (100%)

Felt the involvement of PFAs make a difference in the work of the SCNs (100%)

SCN leadership responded to a different module of the PPEET that focused on policy and practices that support PFA engagement, participatory culture, influence and impact and collaboration and common purpose.

Most SCN leadership agreed:

That the SCNs have an explicit strategy and framework for PFA engagement (86%)

The SCNs have explicit strategies for recruiting PFAs, depending on the engagement initiative (79%)

A commitment to the principles and values of PFA engagement is found in key SCN documents (eg, transformational roadmaps) (93%)

However, there were some mixed responses on the following:

50% of the respondents were neutral on the statement that the resources available for PFA engagement is adequate (43% agreed/strongly agreed and 7% disagreed).

43% of the respondents agreed/strongly agreed to SCNs preparing reports that summarise the contributions from PFA engagement initiatives (36% of respondents were neutral and 21% disagreed).

The statement ‘Comprehensive patient and family engagement training and materials are available to support staff who are leading and supporting these activities’ had 42% responding neutral, 41% agreeing/strongly agreeing and 17% disagreeing.

Some of the SCN leadership that responded neutral for some statements indicated in the comments that this was due to lack of awareness on specific activities and resources. The results indicate variation among the 11 SCNs and 5 Provincial Programmes in how patient and family engagement is conducted and reported.

Phase 2b

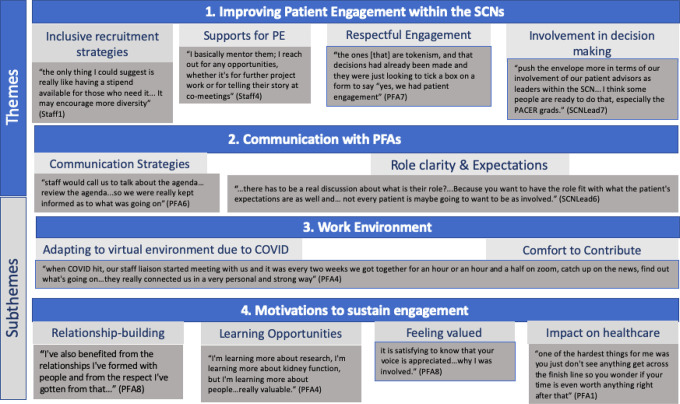

Interviews were conducted with 26 individuals including 13 PFAs, 6 SCN staff and 7 SCN leadership. Interviews ranged from 25 to 94 mins. Figure 2 displays an overview of the themes and subthemes, and table 2 provides more details on the themes, subthemes and associated quotes. The identified themes highlighted additional considerations in patient and family engagement and additional PFE-Is, such as mentorship for PFAs, capacity building opportunities for PFAs and SCN staff members in patient-oriented research (training/orientation) and virtual engagement of PFAs.

Figure 2.

Overview of themes and subthemes identified from interviews with PFAs and SCN staff. Patient and Community Engagement Research; PE, patient engagement; PFAs, patient and family advisors; SCNs, Strategic Clinical Networks.

Table 2.

Themes, subthemes and selected quotes.

| Theme and subthemes | Quote |

|

Improving patient engagement within the SCNs Inclusive recruitment strategies Supports for engagement Views on respectful engagement involvement in decision-making |

“I sent a letter in about 2 years ago to Dr. and I said, “you know, I've really enjoyed being involved but, you know, you need to get more members of the public involved, more than just me.” …, not 20 but you know, maybe- they probably have two or three now, members of the SCN, or maybe more…part of the core committee, so I think…those are the things that I would potentially change” (PFA3) “We have a real passionate group, right? And after 2 years I feel like a little bit of momentum has dropped. But I mean it was COVID-19 for goodness sakes, right? … we did recruit four new advisors in January so we tried anyways. But we still—we want to get a sweet spot of about 15 where at last half of them attend a meeting, right, whereas right now if we have 11 then we only have five or six attending… And I mean not that that’s bad it’s just, you want more voices, right? And people aren't responding, they're not great at responding to emails. Even though we send out lots of opportunities sometimes it’s just that reach out directly to the person that works best.” (Staff4) “One of the first things I did was develop a resource for Skype because our—I think AHS either was in the process of or didn't have one that I felt was kind of user friendly. So I developed that and actually shared that among the networks to say hey, here I have this Skype for patients and families to use. We developed an orientation PowerPoint, so it really—once they've been fully onboarded then we do this orientation and it’s probably 45 min presentation and discussion and questions. And it really talks about all the three areas in the network …and it introduces who the network is all this kind of main subject areas… The other thing we did was a resource, it’s like a dictionary…a glossary of terms for our network.” (Staff4) “The ones [that] are tokenism, and that decisions had already been made and they were just looking to tick a box on a form to say “yes, we had patient engagement”. And although there was some effort…I can spot a project to nowhere and I'm just a bobblehead as a patient advisor after one meeting,…At the beginning had more of those type of experiences, and as you gain experience and knowledge of how AHS works, you know to pick and choose what projects you think are realistic and that will actually move forward.” (PFA7) “The other place I think that I want to get to is, as an SCN and not just me personally, is to really kind of really push the envelope more in terms of our involvement of our patient advisors as leaders within the SCN. So to really try to get them to be a bit more leading in terms of bringing their ideas forward and getting sort of at the end of that IAP2 spectrum really coming up with the ideas and being able to run with them and work on it from that perspective. And I think some people are ready to do that, especially the PACER grads. But I think I'd like to see the whole community move that way.” (SCNLead7) |

|

Communication with PFAs Role clarity and expectations Communication strategies |

“There was a long-time patient or family advisor who wanted the network to work on something that he was interested in. But it didn't align with operational priorities so it never rose to the top…We can't do everything and for him to be meaningfully engaged… we and he decided that how he contributed to the network would change. And he came more focused on other contributions to research and to providing inputs occasionally to surveys that we would do, and certainly continuing to receive communications, etc. But when there isn't that alignment, we can't force it.” (SCNLead2) “Staff would call us to talk about the agenda… review the agenda…so we were really kept informed as to what was going on” (PFA6) |

|

Work environment Comfort to contribute Adapting to virtual involvement due to COVID-19 |

“I remember when I went to my very first meeting, I was so nervous because I thought like they would be like “you interlopers, what are you doing here,” kind of thing. I thought we would stand out and be like really weird, and it was completely the opposite. It was incredibly welcoming” (PFA2) “I was on a side project…the person who was leading the project, …would ask a question. And one time – one question, the physician would answer first…high up EMS people would answer, and then she would ask us as family patient advisors. The next question: she’d flip it and she’d ask the EMS guys first, then the family patient advisors, then the physician…Never have I felt more like an equal than I did on that project.” (PFA11) “It depends on the meeting, like once it’s too big, you kind of lose people and everybody is drifting off, but for smaller engagement it’s- it’s actually very effective. It’s good for the environment, because there’s less travel, and it’s good for infection control, because before the pandemic, if we were getting people together face-to-face, if one person decided to go with a cold, they probably would leave some of that virus behind. So, it’s the future” (SCNLead4) |

|

Motivations to sustain engagement Relationship-building Feeling valued Learning opportunities Having an impact on the healthcare system |

“I've also benefited from the relationships I've formed with people and from the respect I've gotten from that… it is satisfying to know that your voice is appreciated and that really is – really is the way – why I was involved and why I keep being involved with the research.” (PFA8) “I wanted to commend the SCNs in their ability to make patients feel like superstars. You know, to help us recognise that we are as important as the head of Nephrology. And there’s a huge ego boost in that and that ego boost is necessary in order to give people the confidence to speak up.” (PFA5) “That’s been the joy of the SCN as well. Is really learning. The physician and medical experience which I want more of, as well as hearing other patient partners and building that network. I've had this opportunity and I've always been a lifelong learner, so every time I attend a presentation, every time I’m part of an event, I'm learning more about research, I'm learning more about kidney function, but I'm learning more about people even more important to me, so it has been really valuable.” (PFA4) ‘I’ll admit, I was a little—not suspicious, but fatalistic at first, thinking, yeah, will it make any difference? But the more I found that they really took patient complaints or suggestions positively, and I saw things actually being enacted that made a difference. It kept me going and eager to do more.” (PFA12) |

AHS, Alberta Health Services; EMS, Emergency Medical Services; PFA, patient and family advisor; SCNs, Strategic Clinical Networks.

Improving patient engagement within the SCNs

Both PFAs and SCN staff recognised the need for inclusive strategies for recruitment and retainment, to involve various other patients in health research and within SCNs. Some SCN staff expressed difficulties with recruiting new PFAs, and retaining current advisors. Strategies mentioned by some staff included the importance of reaching out to clinical, special interest and non-profit groups for support in recruiting PFAs, bringing awareness to what a patient advisor is and using social media.

Some staff also noted some barriers to recruitment including the:

Onboarding process for the organisation, which can be extensive for engagement especially those required for one-time or for a limited time.

COVID-19 pandemic and how it impacted the time people have available.

Lack of compensation available for patient advisors which may exclude some advisors who represent marginalised and hard to reach communities (eg, unhoused individuals).

Most PFAs who had felt supported in the engagement activities, mentioned having a strong relationship with their SCN team. SCN Leadership and staff also discussed their patient engagement strategy and how it evolved over time. Staff and Leadership felt supported in being able to carry out patient engagement in their work. To improve patient engagement within the SCN, participants highlighted various supports for patient engagement that are required to be consistent within the SCNs: resources about how to engage with patients and working together, mentorship for PFAs, capacity building opportunities for both SCN staff and PFAs such as training and/or orientation. Some participants also discussed whether compensation for engagement would be needed as an acknowledgement of the time and contributions of PFAs. Finally, participants indicated a vital component for working together successfully included respectful engagement and the sincerity of those engaging patients. In various committees, participants indicated excellent partnerships were key to feeling respected and accordingly that they felt like they could contribute to the SCN.

Some participants highlighted the need for PFAs to be involved in decision-making processes through early engagement at the conception of the project and including PFAs in more leadership positions such as co-chairing or co-leading committees.

Communication with PFAs

Some PFAs emphasised needing clear and timely communication about the status of projects, for example, when projects were being implemented, whether projects were moving forward and updates on the general work of the SCN. Participants emphasised the importance of setting clear expectations for engagement activities and for the role of a PFA. Some PFAs described their role within the SCNs as advising on projects, acting as leaders or members in patient advisory groups, being invited to share their stories/perspectives on their healthcare experiences and providing input on meeting agendas. However, there were also some PFAs who mentioned lacking clarity on their role within the SCN when they had initially joined the network.

Some SCN staff discussed some challenges in managing expectations of PFAs (regarding timeline of the project, or the priorities of the network), which may have not aligned with the expectations of the PFAs. Some staff expressed how they had to communicate to patients the difference between advisor versus advocate as the roles are different within the SCNs, and have the potential to lead to differing priorities. One staff member discussed developing a ‘parking lot’ to provide a safe space in bringing up topics of concern and interest to PFAs, but not aligning with current priorities of the SCN. The aim of this idea is to ensure that PFAs’ ideas are not lost but recognised for the potential to be address at a later date.

Work environment

Most PFAs described feeling comfortable in being able to contribute in meetings with other stakeholders and still feeling engaged in virtual meetings and projects, and adapting well to working in a virtual setting. There were few PFAs who expressed frustration with lack of patient engagement in the SCNs during COVID-19, and some who had stepped down from their PFA position as a result.

Almost all SCN staff also mentioned working virtually with SCN teams including PFAs have been a positive experience (such as alleviating burden from travel or facilitating engagement). However, both SCN staff and PFAs mentioned missing the personal connection and networking aspect of in-person meetings. Other concerns with virtual engagement were that it would be more difficult for new advisors to be engaged in a virtual environment, and some advisors may be uncomfortable with technology and encounter connection issues.

Motivations to sustain engagement

Most PFAs mentioned their reason for joining and staying was to have an impact on the healthcare system, and to feel like their contributions mattered.

There were mixed responses from PFAs on whether they felt acknowledged for their contributions and valued as team members. Some PFAs felt valued as members of their SCNs, and detailed ways in which they felt acknowledged for their contributions. There were also some PFAs who spoke about instances in which they felt they were of low priority for the SCNs, or felt their involvement was tokenistic. Some PFAs also described how they valued learning from their SCN teams, learning about research, their conditions and the healthcare system. For some PFAs, meeting people and building relationships was valuable in their engagement within the SCNs, and a reason for them to continue to stay involved.

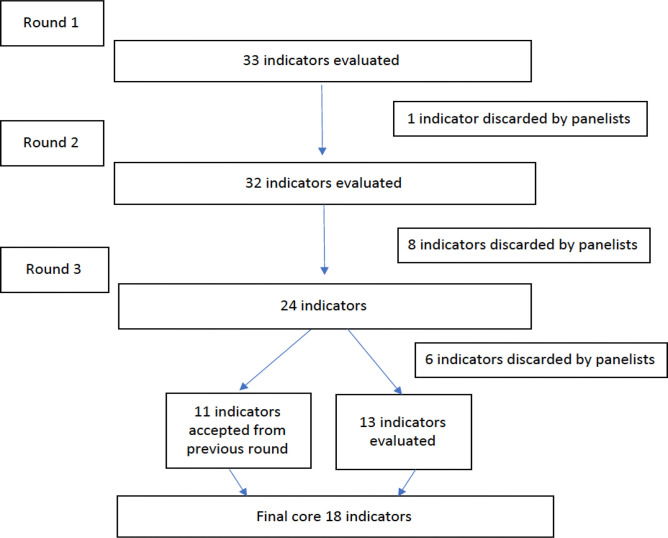

Phase 3

During phase 3, 23 participants (8 PFAs and 15 SCN staff members) arrived at consensus on the core PFE-Is over three rounds of discussions. They rated each indicator based on the following criteria: overall importance, impact on patient and family engagement, actionable by SCNs, interpretability and relevance (figure 3).

Figure 3.

A flow chart of the patient and family engagement indicators modified Delphi process.

At the end of the third round, seven different categories of PFE-Is were developed, including:

Communication: Assess whether enough information has been provided to PFAs to have an overall understanding of the SCNs and specifically their role.

Comfort to contribute: Assess whether PFAs are comfortable in contributing within their SCNs, through expressing their views freely.

Supports for engagement: Assess whether there are necessary supports available for patient and family engagement within the SCNs for PFAs and SCN staff.

Impact and influence of engagement initiative: Assess whether PFAs and SCN staff agree that involvement of PFAs make a difference in the work of the SCNs, and that SCNs take the feedback provided by PFAs into consideration.

Diversity of perspectives: Assess whether individuals engaging in SCN teams represent a broad range of perspectives.

Respectful engagement: Assess whether individuals engaging in SCN teams perceive the engagement as respectful and sincere to working together

Working together: Assess whether PFAs work together with SCN staff to design, conduct and disseminate SCN projects

Specifically, 33 PFE-Is were developed through phase 1 and phase 2 of this work. These 33 drafted indicators were presented to the panel for rating using the rating criteria: overall importance, impact on patient and family engagement, actionable by SCNs, interpretability, and relevance.

During the first round and based on final ratings, one indicator was discarded: Each SCN prepares reports that summarise the contributions from PFA engagement initiatives, as the overall importance was rated low.

During round 2, eight indicators were discarded by the panellists as these PFE-Is were perceived by the panellists as too broad and difficult to measure including: PFAs being meaningfully engaged virtually; PFAs have a supportive working environment to contribute to the engagement initiative; SCNs have mentorship opportunities for PFAs; each SCN has an explicit strategy or framework for patient engagement; each SCN is at the stage of established/making some progress in engagement with PFAs; each SCN has explicit strategies for recruiting PFAs, depending on the engagement initiative; there are resources (documents and guidelines) available to SCN Staff for PFA engagement; the SCN is achieving its stated objectives.

Slight modifications were made to some of the indicators that were considered ‘keep’ such as clarity in the wording. For instance, the indicator ‘Clear understanding of the purpose of the SCN’ was modified to include ‘SCN that I am a part of’ to make it clear to respondents that the indicator is measuring the purpose of a specific SCN that the PFA belongs to, and not all the SCNs. Panellists also recommended breaking the ‘working together’ indicator into separate indicators to reflect the many ways PFAs work together with the SCNs. For instance, in the design of projects, conducting projects and in the dissemination of projects.

Of the 24 indicators from round 2, 11 indicators were accepted by the panellists and 13 indicators needed to be refined by the panellists at the third round of voting. From round 3 of voting, six indicators were discarded by panellists: PFAs have received training on patient engagement (eg, orientation to patient-oriented research); SCN staff have received training on patient engagement (eg, orientation to patient-oriented research); the responsibilities related to patient engagement are clearly articulated in my job description; there are dedicated patient and family engagement leadership positions; AHS resources for patient engagement are useful for partnering with PFAs (answered by SCN staff); SCN staff work together with PFAs to disseminate SCN projects (eg, co-presenting at conferences, sharing work widely) (answered by SCN staff).

A final core group of 18 indicators were accepted. The final indicators from this Delphi consensus generating process are displayed in table 3. Certain indicators were developed based on previous indicators (eg, indicators 14–17), some indicators were developed after round 2, and then introduced again for voting in round 3. Details of the final indicators (numerator and denominator) are included in online supplemental appendix 2.

Table 3.

Summary of consensus panel ratings on overall importance for the final 18 patient and family engagement indicators

| Patient and family engagement indicators | Round 1 remote panel rating (median score on 9-point scale and (IQR)) |

Round 2 online consensus meeting decision |

Round 3 remote panel decision (% of panellists voting to keep indicator) |

Indicator source (PPEET I=interviews C=consensus) |

| 1. Enough Information about the role | 8 (7–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 2. Clear understanding of the purpose of the SCN that I am a part of | 7 (6–9) | Keep, with edits | Keep (90) | PPEET, C |

| 3. Able to express views freely | 8 (8–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| Supports for engagement indicators (n=2) | ||||

| 4. PFAs have supports available for engagement (eg, technology, travel) | 8 (7–9) | Keep, with edits | Keep (80) | PPEET, I, C |

| 5. AHS resources for patient engagement are useful for partnering with patient and family advisors | No rating (not developed yet) | Newly developed derived from previous ‘Resources for Patient Engagement Indicator’ | Keep (80) | C |

| 6. Involvement of PFAs make a difference in the work of SCNs (answered by PFAs) | 9 (8–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 7. Involvement of PFAs make a difference in the work of SCNs (answered by SCN staff) | 9 (8–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 8. SCNs take the feedback provided by PFAs into consideration (answered by PFAs) | 8 (7–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 9. SCNs take the feedback provided by PFAs into consideration (answered by SCN staff) | 8 (7–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 10. Individuals engaging in SCN teams represent a broad range of perspectives (answered by PFAs) | 8.5 (7.25–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 11. Individuals engaging in SCN teams represent a broad range of perspectives (answered by SCN staff) | 8.5 (7.25–9) | Keep | N/A | PPEET, I |

| 12. Individuals engaging in SCN teams perceive the engagement as respectful and sincere to working together (answered by PFAs) | 9 (8–9) | Keep | N/A | I |

| 13. Individuals engaging in SCN teams perceive the engagement as respectful and sincere to working together (answered by SCN staff) | 9 (8–9) | Keep | N/A | I |

| 14. PFAs work together with SCN staff to design SCN projects (eg, in priority setting and planning, development of proposals) (answered by PFAs) | No rating (not developed yet) | Newly developed derived from previous ‘Working Together Indicator’ |

Keep (95) | C |

| 15. SCN staff work together with PFAs to design SCN projects (eg, in priority setting and planning, development of proposals) (answered by SCN staff) | No rating (not developed yet) | Newly developed derived from previous ‘Working Together Indicator’ |

Keep (95) | C |

| 16. PFAs work together with SCN staff to conduct SCN projects (eg, collaborate in data collection, analysis/interpretation, advising on project as it is carried out) (answered by PFAs) | No rating (not developed yet) | Newly developed derived from previous ‘Working Together Indicator’ |

Keep (79) | C |

| 17. SCN staff work together with PFAs to conduct SCN projects (eg, collaborate in data collection, analysis/interpretation, advising on project as it is carried out) (answered by SCN staff) | No rating (not developed yet) | Newly developed derived from previous ‘Working Together Indicator’ |

Keep (90) | C |

| 18. PFAs work together with SCN staff to disseminate SCN projects (eg, co-presenting at conferences, sharing work widely) | No rating (not developed yet) | Newly developed derived from previous ‘Working Together Indicator’ |

Keep (75) | C |

N/A=voting not required/applicable as PFE-I accepted in the previous round.

AHS, Alberta Health Services; PFA, patient and family advisor; PFE-I, patient and family engagement indicator; PPEET, Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool; SCN, Strategic Clinical Network.

bmjopen-2022-067609supp002.pdf (137.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

Working in partnership with the AHS SCN teams, their advisors in the Patient Engagement Reference Group, and the Albertans4HealthResearch Collaborative Council, we co-developed PFE-Is to measure engagement in health system transformation. Through an initial synthesis of the evidence and a consensus approach using the PFE-Is we were able to develop 18 indicators that reflect meaningful patient engagement. The findings align with the core principles highlighted in the CIHR SPOR Patient Engagement framework: Inclusiveness, Support, Mutual Respect and Co-Build.12

The final 18 evidence-based and patient, family and stakeholder informed indicators are ready to be used to measure and evaluate meaningful engagement in health system transformation. The use of these indicators promotes the changes needed to improve the quality of health research and health system improvement that is informed by patients and families. The use of the indicators within the healthcare system to learn from and evaluate health policy and practice related to what matters to patients and families is a critical next step.

The strength of this study is the participatory approach used to develop PFE-Is, which ensures that engagement was evaluated from the perspective of those who provide and receive care. We aimed to adhere to the guiding CIHR principles for patient engagement. Our process was inclusive—we engaged PFAs from different SCNs who bring diverse healthcare experiences and conditions. Support—financial compensation was provided to the patient partners in our team, and flexibility given to PFAs engaged in the consensus process (survey to rate indicators could be completed at own pace, feedback encouraged over Zoom using chat features and during meetings). Mutual respect—acknowledging and valuing expertise and experiential knowledge of all members of the research team and members of the consensus. Co-build—working with our patient partners to design, review, conduct and disseminate the findings of the project. To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop a set of PFE-Is using a rigorous evidence-based and person-centred approach and involving patients and caregivers throughout the research process—from inception of the project to manuscript development including dissemination activities.

Using a highly participatory approach, we sought to ensure that the study was guided by the perspective of individuals with lived experiences, and that diverse perspectives were reflected in the development of the PFE-Is. Consensus methods have been used in patient and family engagement research with PFAs. For instance, the study by Anderson et al23 identified 32 recommendations for optimising patient engagement in hospital planning and improvement. Their recommendations align with the findings identified from our interviews with SCN members, such as inclusive recruitment strategies, providing PFAs supports for engagement and respectful engagement.

While measures of engagement were identified in Boivin et al review,15 these were not considered indicators as per the definition of indicators suggested by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality—as units of measurement, such as percentage or proportion.24 The measure, PPEET,17 was identified by patients, caregivers and other individuals from diverse communities in Alberta as the measure to use given it was relevant and addressed important domains measuring patient engagement.

These newly developed indicators present an opportunity to improve meaningful engagement ensuring that the voices of the individuals with lived experiences are incorporated into health systems supporting the transformation of healthcare. To drive changes in healthcare policy and practice, there is a need to develop and implement standardised ongoing mechanisms to measure and evaluate healthcare incorporating the patients’ perspectives. In doing so, the effectiveness of engagement practices can be strengthened and advanced across the system.

The findings from the survey and interviews reflected priorities that focused on the process of patient engagement as they were from the perspectives of PFAs and SCN staff members working together within the SCNs. Impact of patient engagement on PFAs and SCN staff members on themselves are captured in some of the PFE-Is. However, indicators assessing impact of patient engagement on the organisation were not developed (such as changes in policies, procedures and resources), which may be a limitation of this work. Similarly, the review by Boivin et al15 and Dukhanin et al25 found most evaluation tools assessing context and process of evaluation. Dukhanin et al25 notes that measuring outcomes of engagement is needed, such as documented changes in policies, procedures or programmes, however current measures do not sufficiently capture these aspects. Another limitation of this project is that these set of indicators have not been evaluated. However, a future direction of this work is to evaluate and implement the indicators within the current healthcare system. We have started consultations with AHS SCNs stakeholders to assess the feasibility of data collection processes. Only by attempting real-world data collection can we determine whether the indicators meet the traditional standards of ‘good-quality measures’, to be acceptable, reliable and valid.26 Moreover, studying the implementation of the PFE-Is could shed light into their effectiveness for promoting improvements in patient engagement across the SCNs for specific projects (health research and quality improvement). It is also important to identify any unintended consequences as a result of the implementation of these PFE-Is, of their use for benchmarking and other issues that may arise, such as implications on staff workload and their cost-effectiveness.

Additionally, while this method has generated these 18 PFE-Is using a validated consensus method, they may not necessarily be universally applicable in all settings and countries due to differing healthcare systems. Different cultural settings in different healthcare regulatory environments may mean that different measures may be more appropriate for certain settings. Further work can be done to tailor and adapt these PFE-Is, recognising that a consideration of the local context will ensure a more universal relevance. Future steps for this work include the evaluation of implementing these indicators within the SCNs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Ana Flechas and Dr Sumedh Bele for their support in phase 2 of data collection. We would also like to acknowledge our Albertans4Health Research Collaborative Council, the Alberta Health Services Strategic Clinical Networks and patient and family advisors for their participation.

Footnotes

Twitter: @MariaJ_Santana, @Sadiaahmed1221

Contributors: MJS and TW conceived and designed the study. TLM, GW, SZ and SA conducted data collection. SA and MJS worked on the analysis and interpretation of findings, with feedback from TW, PF, GW, SZ, MM, JP, TLM. MJS, SA and PF drafted the article, and all authors (TW, GW, SZ, PF, MM, JP) provided critical feedback and approved the manuscript to be published. MJS accepts full responsibility for the work and conduct of the study.

Funding: This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) (Grant Number: N/A).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. This study analyses qualitative data and the participants did not consent to have their full transcripts made publicly available. Other additional data available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB) has approved this project (REB20-1822). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Santana M-J, Manalili K, Zelinsky S, et al. Improving the quality of person-centred healthcare from the patient perspective: development of person-centred quality indicators. BMJ Open 2020;10:e037323. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2018;13:98. 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veitch D. One Province, one healthcare system: a decade of healthcare transformation in Alberta. Healthc Manage Forum 2018;31:167–71. 10.1177/0840470418794272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasylak T, Strilchuk A, Manns B. Strategic clinical networks: from pilot to practice change to planning for the future. CMAJ 2019;191(Suppl):S54–6. 10.1503/cmaj.191362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yiu V, Belanger F, Todd K. Alberta’s strategic clinical networks: enabling health system innovation and improvement. CMAJ 2019;191(Suppl):S1–3. 10.1503/cmaj.191232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mork M, Laxdal G, Wilkinson G. Patient and family engagement in Alberta’s strategic clinical networks. CMAJ 2019;191(Suppl):S4–6. 10.1503/cmaj.190596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manns BJ, Strilchuk A, Mork M, et al. Alberta’s strategic clinical networks: a roadmap for the future. Healthc Manage Forum 2019;32:313–22. 10.1177/0840470419867344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarron TL, Moffat K, Wilkinson G, et al. Understanding patient engagement in health system decision-making: a co-designed scoping review. Syst Rev 2019;8:97. 10.1186/s13643-019-0994-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarron TL, Noseworthy T, Moffat K, et al. A co-designed framework to support and sustain patient and family engagement in health-care decision making. Health Expect 2020;23:825–36. 10.1111/hex.13054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit . Patient engagement. 2022. Available: https://absporu.ca/patient-engagement/

- 11.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method user’s manual. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canadian Institute for Health Research . Canadian strategy for patient-oriented research (SPOR). 2014. Available: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html

- 13.Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit . PaCER-patient and community engagement research. 2022. Available: https://absporu.ca/patient-engagement/pacer/

- 14.IMAGINE SPOR . IMAGINE patient research partners 2022. 2022. Available: https://absporu.ca/patient-engagement/pacer

- 15.Boivin A, L’Espérance A, Gauvin F-P, et al. Patient and public engagement in research and health system decision making: a systematic review of evaluation tools. Health Expect 2018;21:1075–84. 10.1111/hex.12804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton CB, Hoens AM, McQuitty S, et al. Development and pre-testing of the patient engagement in research scale (PEIRS) to assess the quality of engagement from a patient perspective. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206588. 10.1371/journal.pone.0206588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abelson J, Li K, Wilson G, et al. Supporting quality public and patient engagement in health system organizations: development and usability testing of the public and patient engagement evaluation tool. Health Expect 2016;19:817–27. 10.1111/hex.12378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute . Ways of engaging-engagement activity tool (WE-ENACT) – patients and stakeholders 3.0 item pool. 2016. Available: https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-WE-ENACT-3-0-Patients-Stakeholders-Item-Pool-080916.pdf

- 19.Qualtrics . Online survey software. 2021. Available: https://www.qualtrics.com/core-xm/survey-software

- 20.Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:77–84. 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anderson NN, Baker GR, Moody L, et al. Consensus on how to optimise patient/family engagement in hospital planning and improvement: a Delphi survey. BMJ Open 2022;12:e061271. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) . AHRQ quality indicator tools for data analytics. 2022. Available: https://www.ahrq.gov/data/qualityindicators/index.html

- 25.Dukhanin V, Topazian R, DeCamp M. Metrics and evaluation tools for patient engagement in healthcare organization- and system-level decision-making: a systematic review. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:889–903. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in health care. In: Improving patient care. John Wiley & Sons, 20 May 2013. 10.1002/9781118525975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-067609supp001.pdf (78.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-067609supp002.pdf (137.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. This study analyses qualitative data and the participants did not consent to have their full transcripts made publicly available. Other additional data available upon reasonable request.