Abstract

Background:

An estimated 21 million children worldwide would benefit from palliative care input and over 7 million die each year. For parents of these children this is an intensely emotional and painful time through which they will need support. There is a lack of synthesised research about how parents experience the care delivered to their child at the end of life.

Aim:

To systematically identify and synthesise qualitative research on parents’ experiences of end-of-life care of their child.

Design:

A qualitative evidence synthesis was conducted. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021242946).

Data sources:

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Web of Science databases were searched for qualitative studies published post-2000 to April 2020. Studies were appraised for methodological quality and data richness. Confidence in findings was assessed by GRADE-CERQual.

Results:

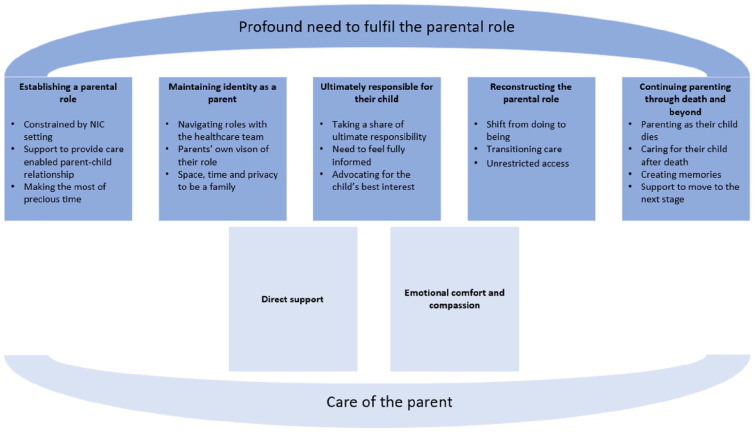

About 95 studies met the eligibility criteria. A purposive sample of 25 studies was taken, of good-quality papers with rich data describing the experience of over 470 parents. There were two overarching themes: parents of children receiving end-of-life care experienced a profound need to fulfil the parental role; and care of the parent. Subthemes included establishing their role, maintaining identity, ultimate responsibility, reconstructing the parental role, and continuing parenting after death.

Conclusions:

Services delivering end-of-life care for children need to recognise the importance for parents of being able to fulfil their parental role and consider how they enable this. What the parental role consists of, and how it’s expressed, differs for individuals. Guidance should acknowledge the need to enable parents to parent at their child’s end of life.

Keywords: End-of-life care, palliative care, child, parents, qualitative research, systematic review

What is already known about the topic?

The availability and access to end-of-life care for children differs across countries, and the role of specialist paediatric palliative care services and hospices varies considerably internationally.

Whilst it is recognised that parents need support, little is known about how parents experience care delivered to their child at the end of their lives, or what type of support they need to do this.

There is no recent international review of qualitative studies of parents’ experiences of end-of-life care for children across settings.

What this paper adds?

Parents of children receiving end-of-life care experienced a profound and continuing need to fulfil the parental role, and what this role consisted of, and how it was expressed, differed for individual parents.

In order to enact their preferred roles, parents need direct care in terms of physical and emotional support from healthcare professionals.

Parents not able to fulfil their expectation of the parental role can feel excluded, this will have an impact on both short and long-term outcomes.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

End-of-life care provision for children needs to include individually negotiated and tailored practical and emotional support for parents to establish and fulfil their parental role through death and beyond.

Policy and guidance should acknowledge the importance of parents being able to parent their child at end-of-life.

There is a paucity of research that considers parental experiences of end-of-life in different settings, and a lack of understanding of the impact of different personal and family circumstances on parents’ ability to fulfil their preferred role.

Background

It is estimated that nearly 21 million children worldwide would benefit from palliative care input1 and over 7 million babies and children die each year.2 The availability and access to end-of-life care for these children differs across countries, and while provision in many places is advancing, the way care is organised is often still inconsistent and incoherent.3–5

Despite differences in delivery models across cultures and countries, the need to support parents through this intensely painful and emotionally demanding experience, is recognised and should be a common key component of care whatever the setting.6 In addition to their own distress, parents often bear the heavy responsibility for the personal and nursing care of their child, and are involved in making extremely difficult decisions such as the withholding or withdrawal of treatments.7

The quality of care that is provided around the time of a child’s death will shape parents’ experiences, not just as they attempt to navigate and cope with such a devastating event, but also during the years afterwards.8 This review focuses on parental experiences of end-of-life care, which is usually defined as support for people who are in the last years or months of their life.9 Together for Short Lives, an internationally renowned children’s palliative care charity, describes the end-of-life stage for children as beginning when a judgement is made that death is imminent, although this can be difficult to make.7 End-of-life care is one component of paediatric palliative care which is provided from the point of diagnosis and throughout a child’s illness.

There is an acknowledged need to prioritise more research on paediatric end-of-life care,10 and there have been a number of primary qualitative studies published in recent years that report on parents’ experiences. However, there is no up-to-date review that draws the evidence across countries and settings together. Synthesising the available qualitative research can provide new insight from primary studies and is particularly important in palliative care, as it maximises the value from studies that have focused on sensitive subjects,11 and makes sense of the evidence in order to deepen understanding of families’ experiences.12

This review therefore aims to systematically identify and conduct a qualitative evidence synthesis of the existing research to understand parents’ experiences of end-of-life care of their child.

Methods

A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis, following Thomas and Harden’s methodology for thematic synthesis,13 was conducted and reported according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines.14 The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021242946).

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of five electronic databases was conducted in April 2020. Databases searched were MEDLINE (1946 to current), EMBASE (1974 to current), CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO, and Web of Science: Social Science Citation Index. A search strategy was developed with a health sciences information specialist and used MeSH terms and synonyms for three search concepts: ‘child’, ‘end-of-life’ and ‘qualitative’. Results were limited to English language reports from 2000 onwards. See Supplemental Table 1 for complete MEDLINE search strategy. Reference lists of identified relevant reviews were also manually searched.

Eligibility criteria

Two authors independently screened each article using Covidence.15 Articles were reviewed against the inclusion/exclusion criteria over two stages: title and abstracts were screened and then the full text was retrieved. Conflicts were resolved though discussion and referral to other authors if required. At full text screening stage, reasons for exclusion were recorded.

Studies were included if they were peer reviewed, qualitative, and examined parents’ experiences of care during the end of life phase of their child (Table 1). To keep the search broad, there were no limits on the child’s condition or diagnosis, or the care setting within which end-of-life care was provided. Studies were only included if there was focus on care provided at the child’s end-of-life specifically rather than palliative care more generally. Only studies conducted in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries were included as it was believed that parents’ experiences would be very different to those in low or middle-income countries. Qualitative studies with mixed samples of parents and healthcare professionals were only included if parent data had been analysed and presented separately.

Table 1.

Full inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Included | Excluded | |

|---|---|---|

| Study type | • Qualitative studies • Mixed methods studies with separate qualitative analysis • Peer reviewed |

• Quantitative studies • Quantitative analysis of qualitative data • Reviews • Evaluations of specific tools • Case studies • Thesis & book chapters |

| Population | • Parents of children who are receiving or have received end of life care ○ Parents: mothers, fathers, step-parents, adoptive parents, long-term foster carers, legal guardians Mixed samples ○ including other relatives if the vast majority (over 70%) of sample are parents ○ including Healthcare Professionals only if parents’ experiences are analysed and presented separately |

• Other relatives or care givers • Health care professionals |

| Focus | • Parents’ experiences of end-of-life care • Parents’ experience of end-of-life decision making |

• Only covering parents’ experiences of palliative care before child had reached the end of life • Only focused on parents’ experiences in the period after a child’s death |

| Setting | • All settings and services • OECD countries: Austria, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States |

• Non-OECD countries |

| Language | • English Language | • Non-English language |

| Date range | • 1 Jan 2000 – date of search |

Quality appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool was used to understand the strengths and limitations of the methodology of all included studies.16 The CASP tool has endorsement from the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group and is the most commonly used tool for quality appraisal in health related evidence synthesis.17 The assessment was conducted on all identified studies by one author with a second author independently checking the ratings. While there was no a priori cut-off threshold for inclusion, quality was considered a factor in the sampling framework.

Purposive sampling strategy

It was anticipated a large number of studies would be identified, and to avoid being overwhelmed by data and undermining the ability to conduct a thorough analysis, a decision was made to take a purposive sample.18 Informed by Ames et al. a two stage sampling framework was used to sample methodologically robust studies, with rich data that was relevant to the synthesis and that captured parents’ experiences across a broad range of settings, countries and child diagnoses.18

Stage 1: Each report was assessed for data richness and relevance to the review objectives, using a scale adapted by France et al.19 The CASP assessment was used to measure methodological quality. Studies were selected that were post-2010 (to give most contemporary practice), that had minor or no methodological concerns, and were assessed to have thick or very thick qualitative findings that related to the synthesis objectives.

Stage 2: Studies were mapped by country, setting of care and by diagnosis of the child. If any of these phenomena of interest were not well represented in the sample from stage 1 then additional studies were added. A decision was made to continue to focus on quality, richness and relevance and so older papers that filled the gaps were added.

Data extraction and synthesis

The characteristics of all included studies were extracted, including title, authors, year of publication, year of data collection, country, care setting, sample population, study design, methods of data collection and approach for analysis.

The articles for the sampled reports were uploaded to Nvivo.20 The results sections, author interpretations and participant quotes were data for synthesis. Several reported findings from the same study, these were treated as one study for study characteristics, but data was extracted from each.

Thomas and Harden’s three stage method of thematic synthesis was followed.13 The first step was line-by-line coding of the data. These codes were then organised, refined, and similarities identified from which descriptive themes were developed. Analytical themes and sub-themes were then generated through discussion and reflection within the team.

Assessing confidence in review findings

To assess the confidence in review findings, GRADE-CERQual was applied, this is a systematic and transparent framework for assessing confidence in individual review findings, based on consideration of four components: (1) methodological limitations, (2) coherence, (3) adequacy of data and (4) relevance.21

Reflexivity

In keeping with quality standards for rigour in qualitative research, researcher views and opinions on parents’ experiences of end-of-life care of children were considered as possible influences on the decisions made in the design and conduct of this review. The review team had diverse professional backgrounds with a range of personal and research experiences and expertise (Clinical Academic; Clinical academic doctor and children’s nurse, researcher; two applied health services researchers and a qualitative researcher) that provided a good platform for engaging and understanding the complexities and nuances of qualitative research of parents’ experiences.

Patient and public involvement

The findings for this review were presented to the Martin House Research Centre Family Advisory Board (a patient and public involvement group). First, parents helped shape how the review was scoped, re-enforcing that parents’ experiences needed to be separated out from those of healthcare professionals. Second, parents also reflected on how the analysis was presented, ensuring that both positive and negative experiences were represented.

Findings

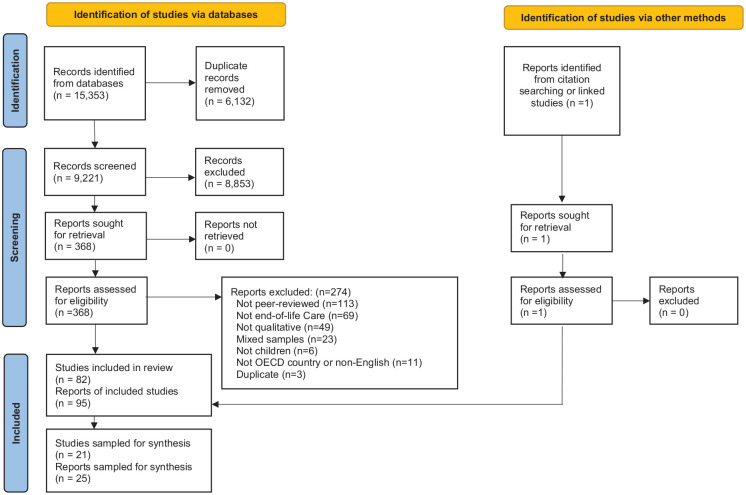

The study selection process is presented in Figure 1. PRISMA Flowchart. After de-duplication 9221 titles and abstracts were screened and 368 full text reports were assessed for eligibility, of which 94 reports met our inclusion criteria. The references of 15 reviews identified in the databases were also manually searched but no further studies were added.22–35 One further report was identified as a linked study giving a total of 95 included reports from 82 studies.

Figure 1.

Prisma flowchart.

Applying the sampling framework to 95 eligible reports, resulted in 19 reports included from the first stage that were found to be of good quality, post-2010, with rich and relevant data. The second stage mapping showed a lack of studies from the UK, and few studies focused on care delivered in the home or a hospice. There was a good range of child diagnoses covered. Six further reports were added to fill those gaps, giving a sample of 25 reports, reporting on 21 studies (Table 2). Supplemental Table 2 gives details of the 70 reports that met the search criteria but were not included in the synthesis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of sampled reports.

| Author | Child characteristics | Summary methodological assessment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Setting | Condition | Age | Parents participants | Study Design | Analysis methodology | Aim | ||

| Abraham and Hendriks43 | Switzerland | Delivery room Neonatal intensive care unit |

All pre-term | Range: Gestational age: 22–27 weeks. |

30 Parents − 12 Mothers − 8 Fathers |

Symbolic interactionism | Hermeneutically oriented qualitative content analysis | Illustrate the perspectives of parents whose extremely premature babies died within a few hours or days of birth. | No or very minor concerns |

| Baughcum et al.39 | United States | Neonatal intensive care unit | Mixed conditions | Mean: 40 days |

45 Parents − 29 Mothers − 16 Fathers |

Mixed methods | Content analysis | To examine parent perceptions of their infants’ care at EOL, 3 months to 5 years after their infant’s death in the neonatal intensive care unit | Minor concerns |

| Brooten et al.8 | United States | Paediatric intensive care unit Neonatal intensive care unit |

Mixed conditions | Mean: 43.4 months |

63 Parents − 44 Mothers − 19 Fathers |

Longitudinal mixed methods survey | Thematic approach | To describe parents’ perspectives of what health care providers did that helped or did not help around the time of their infant/child’s death | Minor concerns |

| Butler et al.44 | Australia | Paediatric intensive care unit | Mixed conditions | Range: <1 years–>13 years |

26 Parents − 18 Mothers − 8 Fathers |

Constructivist grounded theory | Constant comparative analysis | To explore bereaved parents’ perspectives of parent and staff roles in the paediatric intensive care unit when their child was dying, and their relationships with healthcare staff during this time. | No or very minor concerns |

| Butler et al.50 | Australia | Paediatric intensive care unit | Mixed conditions | Range: <1 year–>13 years |

26 Parents − 18 Mothers − 8 Fathers |

Constructivist grounded theory | Constant comparative analysis | To explore bereaved parents’ judgements of healthcare providers, as part of a larger study examining their perceptions of the death of a child in the paediatric intensive care unit. | No or very minor concerns |

| Currie et al.38 | United States | Neonatal intensive care unit | All neonatal | Mean: 109 days Range: 1–223 days |

10 Parents − 7 Mothers − 3 Fathers |

Descriptive qualitative study | Content analysis | To explore parent experiences related to their infant’s neonatal intensive care unit hospitalisation, end-of-life care, and palliative care consultation. | No or very minor concerns |

| Davies57 | United Kingdom | Mixed | Mixed - life limiting conditions |

Range: 3 months– 14 years |

10 Mothers | Hermeneutic phenomenology | Thematic approach | To explore the loss of a child from parents’ perspectives | No or very minor concerns |

| Falkenburg et al.40 | Netherlands | Paediatric intensive care unit | Mixed conditions | Range: 2 weeks– 14 years |

36 Parents − 19 Mothers − 17 Fathers |

Qualitative interview study | Thematic analysis | To explore in what sense physical aspects, influence the parent-child relationship in end-of-life care in the paediatric intensive care unit. | No or very minor concerns |

| Falkenburg et al.42 | Netherlands | Paediatric intensive care unit | Mixed conditions | Range: 2 weeks –14 years |

36 Parents − 19 Mothers − 17 Fathers |

Qualitative interview study | Thematic analysis | To learn what interactions of grieving parents with medical and nursing staff remain meaningful on the long term when facing the existential distress of their child’s death in the paediatric intensive care unit | No or very minor concerns |

| Hannan and Gibson51 | United Kingdom | Hospital Home |

Cancer | Range: 1–19 years |

5 families | Interpretive phenomenological analysis | Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis | To explore retrospectively the decisions made by parents regarding their choice of place of care at time of death for their child with advanced cancer. | Minor concerns |

| Heller and Solomon37 | United States | Hospital | Mixed conditions | Range: 7 days–18 years |

33 Parents − 23 Mothers −10 Fathers |

Qualitative interview study |

Thematic analysis | To better understand what bereaved parents themselves identified as their child’s and their family’s major needs when facing life-threatening illness, particularly at the end of life, and how they thought healthcare providers might best address those needs | No or very minor concerns |

| Hendricks-Ferguson46 | United States | Hospice programme | Mixed conditions | Not reported | 29 Parents − 19 Mothers − 9 Fathers |

Retrospective, descriptive study | Semantic content analysis | To examine parents’ perspectives of: (1) the timing and method used by HCPs to introduce EOL options for their child; and (2) what their preference would have been regarding time and method of introduction of EOL option | Minor concerns |

| Hendriks and Abraham55 | Switzerland | Neonatal intensive care unit | Preterm (<28wks) | Range: Gestational age: 22–28 weeks |

20 Parents − 12 Mothers − 8 Fathers |

Hermeneutically oriented qualitative research | Content analysis | To explore parental attitudes and values in the end-of-life decision-making process of extremely preterm infants (gestational age <28 weeks). | No or very minor concerns |

| Lamiani et al.54 | Italy | Paediatric intensive care unit | Mixed Conditions | Range: 2 months–13 years |

12 Parents − 7 Mothers − 5 Fathers |

Not reported | Hermeneutic phenomenology method | To explore parents’ experience of EOL care in a Paediatric Intensive Care Unit in Italy. | No or very minor concerns |

| Lord et al.52 | Canada | Mixed | Children with medical complexity | Range: 7 months–12 years |

13 Parents −12 Mothers − 1 Father |

Qualitative study | Inductive thematic analysis | To explore the experiences of bereaved family caregivers with ACP for CMC | No or very minor concerns |

| Mitchell et al.47 | United Kingdom | Paediatric intensive care unit | Mixed conditions | Range: 7–23 months |

17 Parents −11 Mothers − 6 Fathers |

Qualitative interview study | Thematic analysis | To provide an in-depth insight into the experience and perceptions of bereaved parents who have experienced end of life care decision-making for children with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions in the paediatric intensive care unit. | No or very minor concerns |

| Monterosso and Kristjanson48 | Australia | Palliative care service | Cancer | Range: 2–17 years |

24 Parents − 16 Mothers − 8 Fathers |

Qualitative study | Thematic analysis | To obtain feedback from parents of children who died from cancer about their understanding of palliative care, their experiences of palliative and supportive care received during their child’s illness, and their palliative and supportive care needs. | Minor concerns |

| Papadatou et al.49 | Greece | Home Hospital |

Mixed conditions | Range: 2.5 months–16 years |

36 Parents − 20 Mothers − 16 Fathers |

Grounded theory | Grounded theory | To (1) develop a theoretical framework grounded in empirical data to explain how parents in Greece decide on the location of their child’s end-of-life care and death, and (2) to explore how choices and service delivery affect bereavement | No or very minor concerns |

| Rapoport et al.53 | Canada | Hospital | Genetic or suspected genetic conditions | Range: 1 month–15 years. |

11 Parents − 6 Mothers − 5 Fathers |

Qualitative study | Interpretive description methodology | (1) to explore the experiences of bereaved parents when a decision had been made to FANH during EOL care for their child and (2) to describe the perceived quality of death in these children, as reported by their parents. | No or very minor concerns |

| Sedig et al.36 | United States | Hospital | Cancer | Range: 1–24 years |

12 Parents − 11 Mothers − 1 Father |

Qualitative focus group study | Constant comparative analysis | To identify what is most helpful, what is least helpful, and what is lacking in EOL care from the perspective of bereaved parents. | Minor concerns |

| Snaman et al.45 | United States | Hospital | Cancer | Range: 1.5–14 years |

12 Parents | Not reported | Semantic content analysis | To explore the communication between hospital staff members and patients and families at the time of patients’ health decline near the end of life | No or very minor concerns |

| Sullivan et al.58 | Australia | Not reported | Mixed conditions | Range: 3 months–12 years |

25 Parents − 19 Mothers − 5 Father |

Exploratory descriptive study | Thematic analysis | To explore the views and experiences of bereaved parents in end-of-life decision-making for their child. | No or very minor concerns |

| Thornton et al.59 | Australia | Neonatal unit | Neonatal | Range: 2 hours–13 weeks. |

18 Parents − 13 Mothers − 5 Fathers |

Grounded theory approach | Grounded theory analysis | To explore the significance of memory-making activities for parents experiencing the death of a neonate, and the impact that these activities have on parents’ experience of bereavement | No or very minor concerns |

| Thornton et al.41 | Australia | Neonatal unit | Neonatal | Range: 2 hours–13 weeks |

18 Parents − 13 Mothers − 5 Fathers |

Grounded theory approach | Grounded theory analysis | To explore the significance of memory-making activities for parents experiencing the death of a neonate, and the impact that these activities have on parents’ experience of bereavement | No or very minor concerns |

| Vickers and Carlisle56 | United Kingdom | Home | Cancer | Range: 2–14 years |

16 Parents − 10 Mothers − 6 Fathers |

Exploratory descriptive design | Thematic content analysis | To explore the parents’ perspective and experiences when caring for a dying child at home. | No or very minor concerns |

Study characteristics

Nineteen out of the 21 studies used interviews, with individual parents or couples, to collect data about parents’ experiences, with the remaining two using focus groups. A range of methods had been used for the data analysis: seven studies used thematic analysis, five used content analysis, three used comparative analysis, two used grounded theory, two used hermeneutic phenomenology, one used interpretive phenomenological analysis and one used thematic content analysis.

The studies were conducted across eight countries: seven in the United States, four in the UK, four in Australia, two in Canada and one from each of Greece, Italy, Netherlands and Switzerland. The studies reported parents’ experiences of end-of-life care for their child delivered across a range of settings and services: seven studies covered a mix of settings, four were based in paediatric intensive care units, four in neonatal intensive care units, two in other hospital settings, two focused on hospice and palliative care services and one covered parents’ experiences of care delivered in a child’s home. One study did not specify the setting.

The diagnosis of the children receiving end-of-life care varied, with the majority (sixteen) of the studies including children with a range of conditions of which four studies were conducted in neonatal units. Five studies reported the experiences of parents of children with cancer. The children aged from pre-term babies to 24 years (only one study had children over 18).36 All the studies were carried out retrospectively after the children had died.

In total the studies collected data from 471 bereaved parents of which 306 were mothers, 148 were fathers and 17 were referred to as parents. Only one study included other participants – an aunt and two grandmothers.37

Supplemental Table 3 gives details of the CASP appraisal of the sample reports.

Overview of themes

The synthesis of the sampled reports identified two overarching themes: the parents of children receiving end-of-life care experienced a profound need to fulfil the parental role; and care of the parent. These are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of themes.

Profound need to fulfil the parental role

Parents experienced a profound need to fulfil the parental role and to be able to ‘be there’ for their child at the end of their life. What the parental role consisted of, and how it was enabled or constrained by the care being delivered, differed for individual parents. However, there were common elements including: spending as much time as possible with their child; actively providing physical and emotional care; and representing and advocating for their child’s best interests.

All 25 reports contributed data to this overarching theme. Five themes, with 15 sub-themes, emerged regarding how parents fulfilled their role. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Profound need to fulfil the parental role: summary of sub-themes.

| • Parents with babies in neonatal intensive care units needed to establish themselves as parents. |

| • Those with older children in intensive care and other hospital settings needed to navigate maintaining their ‘normal’ parental role while their child’s health needs were also met. |

| • For most parents there was a fundamental need to feel fully informed and to represent the child and their best interests, and ultimately be responsible for their child. |

| • Some parents reconstructed their role when they realised their child had reached the end of their life, moving from actively focusing on medical treatments and their child’s survival to ‘being there’ and emotionally supporting their child as they died. Taking their child home, or just the removal of medical equipment enabled parents to reclaim their child. |

| • Finally, it was important that parents were able to continue to enact their role after a child had died. |

Establishing a parental role

Seven study reports contributed to this theme. Three sub-themes were found: constrained by the neonatal intensive care unit setting, support to provide care enabled the enactment of parent-child relationship and making the most of precious time.

Constrained by the neonatal intensive care setting

Parents with babies receiving neonatal intensive care needed to establish themselves as parents. The surroundings of a neonatal intensive care unit presented unique challenges,38 making it difficult to step into their role, in a natural and instinctive way.38–42 Some parents found it hard to make an immediate bond with their child.40,42,43

But then you are actually labelled as the parent. Sure, you have a very important role, but it doesn’t feel like that. Because everybody is saying: You are the mother. But still. . .And then you start doubting yourself, like is something wrong with me then?. . .For in the beginning you feel like, let’s say, I am a perverted mother because I don’t have that feeling, which I should have. And everybody: you are the mother! (N14) 42

Several factors constrained parents, the first often being distress of physical separation from their child, as their baby was taken immediately away at birth to the intensive care unit. This could be further hampered for some mothers if they were recovering from a difficult birth or if their child was in a different hospital, with fathers acting as go-betweens or messengers.41,43

I only got up there once. And I couldn’t actually hold them while they were. . .because they were so small. And I couldn’t actually touch them, because I couldn’t actually reach my hand up to get in, because I couldn’t get out of the wheelchair. (P1) 41

I just gave birth to him, they’d just sewed me up, I got five minutes to see him, and he got taken to a different hospital and I was in a ward filled with mothers and babies crying. So, when they are in NICU, you are not with them. But you sort of feel. . ..What just happened? You feel really empty. (P10) 41

If a baby was very unstable medically, sometimes they could not be held, or were sensitive to contact. For parents, this was stressful and could lead to hesitation or a lack of confidence.41,43 One study reported that fathers in particular, felt some discomfort and fear handling such fragile infants.39

“In a certain way, he never really was our child, because you haven’t been able to do normal things with him. You couldn’t hold him; you couldn’t tend to him. We had started with baby massage. Only once. Then he got worse again and didn’t like the touch anymore”.(Father) 40

“I didn’t go and mess around with him too much…So that was hard for me…I’d look at him mostly. I didn’t feel comfortable enough to touch him for fear of shaking something loose. So, I’d talk to him, and I’d look at him and let him know I was there. I felt that was the most I could do.” (Father, 1 year after death)39

Support to provide care enabled the enactment of parent-child relationship

Parents were clear physical closeness, touching, being able to provide warmth and support to their child were basic parental expressions and were absolutely vital to establish a bond with their child and create positive memories.40,41,43 ‘When I held her to my chest for the first time, my body started to react! Then I thought: yes this is really my baby’.40 Those parents who were supported by staff to actively participate in ‘normal’ or ‘typical’ caregiving activities for their child, such as feeding, bathing, or changing, found this helped them establish their role, make connections, and begin to feel like parents.38,39,41,42

I’m really glad that they consistently put me under pressure to take him (Mother) 43

We bathed him, it was just a sponge, but she was really good. She allowed me. . .you know, she helped me to do all that, but gave me that mothering. Because when your baby’s being looked after by others all the time, you don’t get much of that chance. (P7) 41

I wanted as much as possible. I changed his diaper, I helped give him baths, I fed him when I could. I was the mom. (mother, 3 years after death) 39

Some parents felt excluded, made to feel like a ‘babysitter’ or ‘visitor’44 when they were not able to hold their child and were disappointed if staff did not encourage involvement in their child’s care.39,43,44

I wish we had washed her. I mean I don’t know if they made the call not to do that because I was in an ICU. I guess I feel like I missed the chance to mother her. (crying). . .. I would have liked to have done something like that.(P12) 41

Being encouraged to bond and interact with their baby through song, reading and talking to their child was highlighted as important.39,41,43

She could tell that we just didn’t know what to do, and she said, “well, why don’t you read to him?” and so that then became our thing. And that is a really important memory. . .(P15) 41

I had a big list and we chatted about everything. That was. . . saying all those things that you don’t get to say later. He adds: For me, making that list of everything that I would like to say to my daughter and would have done. . . you know, walk her down the aisle, I can’t walk her down the aisle, but I can talk to her about it. (P8) 41

Making the most of precious time

For parents of babies who only lived for a short time, it was particularly crucial that as much time was spent with their child as possible. Not only was this time incredibly precious, it enabled them to get to know their baby as a person and create an identity for them.38,39,41,43

I got to feel like they were mine, rather than just something that happened. . . They were real people. And they even had personalities and um. . . yeah. . .. They were real. It was very real thing that I did. And yeah, it made them a real part of our lives, and not just this bad thing that happened in hospital one time. (P1) 41

The five days, which were five regular days for others, were the five days of my daughter’s life. (Mother) 43

Maintaining identity as a parent

Twenty-three study reports contributed to this theme. Those parents with children in intensive care and other hospital settings needed to navigate maintaining their parental role while their child’s health needs were also met. Three sub-themes: navigating roles with the healthcare team, parents’ vision of their role, and space and privacy to be a family; also emerged.

Navigating roles with the healthcare team

Maintaining their parental role relied on developing a collaborative and trusting relationship with healthcare professionals and then working together as a team.36,37,39,42,44–52 Trust between parents and the healthcare team was based on parents’ confidence in their capabilities, open communication, staff engaging with the child, and a sense of common purpose.8,44,52,53 There also needed to be shared understanding of each other’s roles and contributions each made towards care of the child, with healthcare professionals providing guidance, support and space for parents to maintain their role.44

We all worked together for the common cause, which was my son. (Alice, hospital 3) 44

Collaboration was enhanced by continuity in the healthcare team, enabling parents to be consistent in their involvement, as staff understood and trusted parents.36,38,44,47 Parents valued staff that had been with them throughout the course of a child’s illness,8,36,45,48 and felt anxious about a change of service or the introduction of a new team, such as the palliative care team.48

I know it’s such a moving world of people changing, but I was grateful for the people that started that process and who were there at the end of the process, because we had developed a relationship. They learned who I was. I learned who they were and you could count on them because my support was from these people here. 36

So, then you worried about not having dealt with these people before but you’ve dealt with all these other ones and you’re more comfortable and then all of a sudden you’re told palliative care and you think whoa, what’s palliative care? (Mother) 48

Parent and professional relationships could be fragile, with trust easily compromised.47 Tensions particularly arose when parents felt healthcare professionals had different priorities, provided conflicting information or insisted on sticking to protocol/rules. It was also hard when parents did not feel listened too, or their expertise and knowledge of their child and their condition were not recognised.8,36,38,47,53

When we were at home, we used to clean his peritoneal catheter but when we were in the PICU the clinicians would say: “You don’t do anything, and please go out of the room. (Father and Mother, INT7) 54

I feel like they wanted to put their agenda on us and it’s just like, ‘This family’s not getting it. They don’t seem to understand their child is going to die’. That’s how we got treated. I’m like, ‘Honey, this is my child. No one understands more than I do that my child isn’t going to survive. Please hear what I’m saying’. 36

One study reported that some families whose child had previously been in a neonatal intensive care environment were particularly resentful when the collaborative relationships they had formed with staff were not continued in the paediatric intensive care unit and so their expectations for their role were not met.44

She commented that in NICU, “they were like, you need to know how to do this, you’re his mum, not us”, but then “as soon as Lucas went in [to PICU], it was a case of you’re not allowed to do that, you’re not allowed to do this”. (Mother) 44

Parents’ own vision of their role

Parents had their own view of what their role should look like, and as with parents of babies in neonatal intensive care, one of the fundamental ways they continued to express their role, was to be involved in caregiving and actively providing comfort to their child. They wanted their role in hospital to ‘mirror’ their normal parental role44,54 and when staff trusted parents’ to provide care to their child, this helped them maintain autonomy.50

What I missed the most was doing the daily things that moms do. I know that it’s not easy to do these things in a PICU but even the possibility of staying there longer and holding his hand was something. (Mother, INT4) 54

I think [to] maintain the existing relationship, the existing dynamic that we had, was important to me (Isabelle, hospital 1). 44

The age of a child and their medical condition influenced parents desired levels of involvement in providing care for their child. Some parents felt their role was maintained by providing basic non-medical care such as hair brushing and massage, whilst others, particularly of chronically ill children, were accustomed to performing more nursing care and so were keen to continue that.44 For parents of older children, where they had naturally moved away from intimate physical care, caregiving was not always seem as a fundamental part of parenting.44

I’d already had that sort of break of not caring for her as a full-on carer [caregiver], so it didn’t really faze me that I hadn’t had that role within PICU. (Mother of a teenager) 44

When a parent was not able to provide care and this role was not facilitated, they reported a loss of control and feeling detached or becoming a ‘watcher’.36,39,40,42,44,55 One study described how parents felt like they were on the side-lines and estranged from events, with fathers in particular feeling at a loss and unclear how to act.42

I wasn’t a mum. I wasn’t even a parent. It just felt like I was a visitor. (Layla (hospital 4)) 44

I felt like a bystander, watching everything (mother, 2 years after death) 39

Space, time and privacy to be a family

Parents described a need for a supportive physical environment for themselves and their child that gave them space and privacy,39,41,43,56 so they could spend as much time as possible together,38–41,43,51,53,57,58 including with siblings if appropriate. This helped parents to feel like a family, ‘preserve their family intimacy’, thus enabling the parental role.51,54 Open and unrestrictive visiting policies encouraged parents to be present,41,57 whereas units that had strict visiting hours in place limited access.38

The most important thing to me was being able to sit with her and talk to her and sort of experience some time with her. (Mother) 48

That was the nice thing. It wasn’t like they were “come on, we’ve got to go home sometime today” sort of thing. It’s like they really showed such a caring nature that I was very impressed by. (P11) 41

Finding privacy varied across the different care settings. Families described the need to be able to escape the noise, overwhelming, and sometimes ‘chaotic’ environment of the intensive care units.36,38,47 Private space in local hospitals was often limited, with few places for parents set aside from busy open wards.56,57 A curtain did not feel adequate, as while it may offer some visual privacy, it was still noisy.43,57 Supportive hospital settings tried hard to ensure that parents were able to remain in close proximity to their child with private rooms or providing large beds that can be shared.40

Under these circumstances there should be the opportunity to be by ourselves. We were always interrupted because if you do not have your private space and clinicians have to intervene on a child who is not yours, they make you go out of the PICU. So, you go in and out. . . If we had our own room, we could always stay with him.(Mother, INT6) 54

It was important for healthcare professionals to balance between being on hand to offer support and leaving the family in peace.39,43 Families found the endless ‘parade’ of staff disruptive and some felt ‘on display’.39 Sometimes it was as simple as staff asking permission to enter the room or approach a child.36

There was also a need to be mindful of privacy when making any transfers or moving patients, particularly right at the end of a child’s life, and it was important to realise that this is a difficult journey for parents – essentially walking towards their child’s death.

I remember that the walk down the hall was very burdensome. (Father) 43

The delivery of end-of-life care itself could impose barriers to the family spending time together such as taking a child for medical treatments or tests. Parents found these interruptions frustrating and could become resentful when denied access to their child.8,44,57

Why are you tipping him up on his bed or bringing this X-ray in, taking me out when I just want to spend time with him? (Zara, Hospital 1) 44

The night before she died, the nurse kicked me out of the room and told me I was doing more damage to her—because I was holding her and touching her. She said I shouldn’t stimulate her and she took her away from me—she took my last night that I had with my daughter away.8

Responsibility for their child

Twenty-one study reports contributed to this theme. Three sub-themes, compelled to take ultimate responsibility, the need to feel fully informed and advocating for their child’s best interests, were identified.

Taking a share of ultimate responsibility

When making difficult end-of-life care decisions, some parents, while allowing themselves to be guided by clinicians, were compelled to take a share of the ultimate responsibility and felt that this was ‘central to their identity as parents’.39,55

I did not experience this moment as a freedom but rather as a responsibility of course because this baby cannot decide for herself. We are her parents, and we should make this decision. And we should decide what is best for our baby. Now in retrospect, I regard that as a great act of love. But in those hours, I thought I would die. But you do not die, and you go on and you have to decide. (Mother) 55

It’s the hardest role I’ve ever had. I did not like having to do it. But I wouldn’t trust anyone else with that decision. (Mother, 2 years after death) 39

Need to feel fully informed

Parents wanted healthcare professionals to provide complete, honest and understandable information, while also listening to parents’ views and concerns.8,36,39,40,48–50,55 Avoiding jargon, using non-medical terminology and (patiently) repeating explanations helped parents to make sense of the situation.8,39,50,55 Upfront and direct communication was often key to parents being able to balance the need for hope, with the seriousness of a situation.36,38,48,50

They explained very clearly the negative and positive aspects of care. This was very helpful because they were straightforward. In other words, they did not leave us with ‘yes, but’, ‘may be’, or ‘it could turn out this or that way’. (F7) 49

I think the best thing is to be really upfront and honest about the medical condition of the child, don’t sugar coat anything. (Father, 2 years after death). 39

Advance care planning and introducing end-of-life options sensitively and at appropriate times was important. Although not all parents agreed at when then time should be, often depending on the medical condition of the child.8,46,47,53,58 One study in particular, found some parents wanted to discuss end of life only when treatment had failed, while others wanted a fuller picture of potential outcomes and felt information should be shared earlier.46

Father recalled a pivotal moment when a surgeon said “‘We will do anything that you want us to do. We will fight and do everything tooth and nail, do everything in our grasp and power; but unfortunately, we don’t think we’re going to succeed. We will do what you want; but if it was my child, I would take him home and love him”(Father) 46

He was very good at explaining things, he was and he would answer any questions . . . from my perspective when he was telling us ‘I’m very sorry. There’s nothing else that we can do’. And then it was believable, I didn’t feel like we’re being fobbed off, or anything like that. (Father 4) 47

Parents were clear that these conversations needed to involve clinicians who they trusted and who knew their child.52 They appreciated professionals who also included their child in discussions about their care and made sure, if appropriate, they understood what was happening.36,42,45,46

For some parents, incomplete or vague information led to uncertainty and anxiety46,49,50 and left them feeling unprepared or not understanding the severity of the situation.8,45 Parents found it particularly difficult if healthcare professionals provided conflicting information38,47,49,51,53 and a few parents suggested that it would be helpful to have one consultant or co-ordinator to liaise with.39,47 Healthcare professionals who didn’t listen or dismissed parents’ concerns, inhibited parents’ ability to protect their child38,47,50 and compromised trust.47

It’s a great idea to have one consultant that will oversee because there’s so many doctors in-out, in-out, in-out, you know, and obviously everybody’s got different opinions as to how things should be done. I think for (Child 10) she would have really benefited from having one person that had one say. (Mother 10) 47

He never said, ‘This is going to take your son’s life’. She strongly believed that the neurosurgeon did not inform them that their son may die.(Mother) 46

Advocating for their child’s best interests

Some parents felt keenly their duty to ensure that end-of-life care plans took account of the child’s best interests, that quality of life was the priority, and that they didn’t suffer unnecessarily.36,39,43,44,46,47,51,53,55,58 There were times when this felt at odds with parents’ own needs or sometimes with the views of clinicians.36

You feel hopeless but they’re still there that day and the next day and you as a mom has to decide how much they are suffering? Are they still surviving? Are they doing okay? (Mother) 36

As much as it did hurt us to let him go, we were thinking what was best for him to be comfortable and not in pain (Mother 2) 47

I had to be the one advocating for quality of life. I will say that was an uncomfortable conversation to have because it feels like as the mother in a weird messed up way you’re advocating for your child’s death, like they care more. (Mother) 36

For other parents, the circumstances were completely overwhelming47; they could not think straight enough to be involved in planning, or they didn’t want the burden of responsibility for such a complicated decision and therefore welcomed clinicians taking control.38,43,46,49,54,55 Two studies highlighted the experiences of some fathers who had relied on their wives to make decision as they felt they were more involved and better informed.39,49

I pretty much left it up to my wife. I mean, she knew more and did more stuff there than I did (Father, 3 years after death). 39

For many, an important part of being a parent and advocating for their child was ensuring that no-one ‘gave-up’.44 Therefore, underpinning the ability to be part of decisions, particularly around end-of-life care, was a need to know that both healthcare professionals and parents themselves had done everything they could,8,42,44–47,55,56 and to remain hopeful until all options had been explored.44,50

He’s [our] responsibility. I know [the hospital] cares about him but I need to know that I’m doing everything as a parent.45

Reconstructing the parental role

Thirteen of the 25 studies contributed to this theme. Three sub-themes emerged: shift from ‘doing’ to ‘being’, transitioning care and unrestricted access to their child.

Shift from ‘doing’ to ‘being’

For some parents there was a point when they understood and accepted their child had reached the end of their lives, this led to a shift, a reconstruction, of their perceptions of their parental role. They moved from a role of ‘doing’ – actively focusing on medical treatments and fighting for their child’s survival, to ‘being’ – spending time together, caring for and emotionally supporting their child.43,44,48,57

Transitioning care

A move from active treatment to comfort care meant for some parents a feeling that they had got their child ‘back’46 – that they were able to reclaim their child. For parents who were able to take a child home or move into hospice care for the end of a child’s life, this meant being in a place where in some sense family life and parenting could return.48,51,56 For example being able to maximise time with siblings and as a family, have friends and relatives to visit and being able to provide comfort in a more accessible and natural environment.46,48,51,56,57

When you are at home you can shut the door and no-one is telling you that your child is ill, when we brought Sally home that was our time. (Family 10, Mother) 56

I did everything as normal for B. We put her on the settee and I chatted away to her. (Mother) 57

Parents regained a sense of control and independence when they left hospital.40,56 It was important that they ensured their child’s wishes were heard. If a child expressed the choice to die at home, they tried to make this happen.48,49,51,56

He perceived the hospital as a prison for the sick, so we decided to return home. If we would keep him in the hospital, he would have felt deserted by us, and we didn’t want this to happen. (F-M17) 49

We’d have been told what to do instead of we telling what to do; we had the choice of whether we had the nurse or not . . . I think we’d done enough living by hospital rules (family 7, mother). 56

However not all parents felt that being at home was the right environment for child. Family and housing circumstances, confidence about meeting their child’s medical needs and the availability of support services were also factors that influenced where parents felt was the best place for their child to die.47,49 Others wanted their child to stay in hospital so medics could prolong their life as long as possible.47 A transition was not easy, and some parents were never ready to make it. They resisted speaking about or engaging with palliative care services. For these parents, palliative care was negatively associated with ‘giving up’ and losing hope.38

So when I heard palliative care, I heard hospice, I knew we were teetering on the edge of life. Instead of looking at the positives that it could do, I was just looking at, you know, I’m not ready to transition to that. We’re still fighting, I still want aggressive care. (mother #8) 38

Unrestricted access

For some children, end-of-life care meant being released from the constraints of equipment, and so parents had free access to hold them, sometimes, for the first time.40,41,54 Despite being intensely emotional, parents described the experience of holding their child, free of medical devices as they died as central to being a parent.41 Others had this experience only after their child had died, yet it remained profound.54

We actually took away all his tubes and stuff and we actually got to hold him for that last couple of hours. (P9) 41

We washed her ourselves and put on her clothes. It was wonderful. We finally had her without tubes. Free..(Mother) 40

Once they ceased treatment, he was really just handed to us like a normal baby.(P7) 41

When you are ready, we are ready.” . . .[.] . . . and then, slowly, they extubated the baby. First, they removed the catheters and then the tubes. . .she had a lot of stuff on. We were there with her- we have been always close to her. They let me hold her and then they left us alone. That’s it. (Mother INT2) 54

Continuing parenting through death and beyond

Nineteen study reports contributed to this theme. Four sub-themes, parenting as their child dies, caring for their child after death, creating memories and support to move to the next stage also emerged.

Parenting as their child died

Being prepared as far as possible, enabled parents to be with their child as they died, and to say goodbye.38,41,50,53,58 For many there was a need to understand what would happen as their child died.36,39,47,50,53–55

I needed someone to sit down with me and say, ‘This is what her death is probably going to look like. This is what you need to be prepared for and how you can best help her through it’. 36

Staff explained “the process of how they take out his tubes and all those little intimate details that you’ve obviously never thought of before because you’ve never been in this circumstance. All the little things like that can make a big difference” (Jessica – hospital 4)50

. . .not knowing what death is and what it’s going to look like. . . when you’re seeing it for the first time, when you’re kind of dealing with it, both as an experience of death but also as your baby. . . I would like to have known that. . .sorry . . . Not everybody would. . . (Mother 6) 47

Parents wanted their dying child to be held either by themselves or the other parent40,41,43 and described this as central to their role of being a parent.41

In the end he died quietly. On daddy’s lap. I said: He was born from my womb, he may go from daddy’s lap.(Mother) 40

Those who believed conversations around prognosis came too late or that they were not given all the information, were left unprepared and rushed.39,57 It was deeply distressing for those parents whose child died when they were not there, or in traumatic circumstances.8,54,57

[Angrily] But one thing I wish they had told me [is] that I could’ve brought him home. I wouldn’t have wanted him to die in hospital. But someone should have said, ‘Look if you want to bring him home, you can’. Because I would have. (Mother, W5) 57

The fact that they called us when the child was already dead was horrible. I had accepted the thought that my son could die. I couldn’t see him anymore in that condition. But not being able to be there in that moment it was devastating. (Mother) 54

Caring for their child after death

For those who were able to, spending time with their child’s body after they had died was important and helped some parents ‘take leave’.39–41,43,54 Parents found comfort in bathing, dressing and holding their child’s body. Those who may have been initially hesitant often appreciated being encouraged to have this time.38–40,43,57

I’m really glad that they consistently put me under pressure to take him. Because one memory about him is his weight: I took him out of the basket on the little cloth which was wrapped around him, and that’s something which I felt long after: his weight. And this was so beautiful. (Mother) 43

I changed him. It was nice to do that, because he. . . I wasn’t able to put clothes on him much while he had all the wires on him. So to be able to do that was nice. But I think it also helped me understand that he was dead, if that makes sense. (P10) 41

Those parents that has access to special cold bedrooms, usually in hospices, particularly cherished the extension of time together, to become ‘aware’ of their death. These facilities were not available to everyone.43,57 Some parents did not feel comfortable being with the child’s after they had died, finding it stressful and wanting to preserve memories of them alive,43 while others regretted not doing more and wished they had been invited or encouraged more actively.43

The only decision I absolutely regret is that after she passed away, the nurses asked me and my wife if we we’d like to help clean her up and put new clothes on her. I said “No”. In hindsight, I feel that was the worst decision I ever made (Father, 3 years after death). 39

I wish we had washed her. I mean I don’t know if they made the call not to do that because I was in an ICU. I guess I feel like I missed the chance to mother her. (crying). . .. I would have liked to have done something like that.(P12) 41

Parents also felt a strong need to understand that someone would be caring for their child until the time of the funeral, and for some the thought of the body being left alone in a morgue or harmed in a post-mortem was distressing.43,54

Creating memories

Nurses helped families create memories of the living, dying and in some cases dead children, through photos and videos, hand and footprints, making memory books and collecting special clothes and toys. These efforts were appreciated8,38,40,57 and the memories were deeply cherished,39 helping parents to remember and tell the story of their child’s life and identity and their time together as a family.41,43 For parents of babies, photos served as evidence of their child’s existence and that their grief was real.59 Some parents experienced discomfort during the process at the time, but appreciated the efforts retrospectively.43

The most powerful photo that we’ve got is one where my wife is holding (baby). And you can just see the heartbreak on her face. At the time I felt bad taking that photo. But I’m very glad we did, because as I said, it kind of reminds you that it did really happen. The pain was real. And her existence was real. (P8) 59

And I mean, for me, I can go back and look at that. And see that my baby did exist. I have proof that he lived.(P2) 59

That’s something I particularly regret as well. The fact that we don’t have a huge amount of photos, or a huge number of photos of (baby) when he was alive in the hospital. We’ve got a few, but certainly you can never have enough. (P16) 59

Support to move to the next stage

Parents acknowledged the need for bereavement support both before and after death,39,52 and the need for this support for siblings was highlighted.39 Parents with children with complex medical conditions felt it would be helpful to have support groups with other families who understood the unique challenges they had faced.52

After a child had died, some parents experienced a loss of the relationships with the teams who had cared for their child39 and in some cases, a sense of abandonment added to their grief.37 Some staff reached out to parents after a child had died, including attending the child’s funeral and this continued contact was a source of comfort8,37,45 and reinforced that the professionals had cared about their child.37 Maintaining a relationship with those that had cared for their child served as a reminder of their identity as a parent and in some cases helped adjust to their loss.48

I had such strong relationship with the people that I had met when I was there, it was difficult after I left and to not have those people in my life (mother, 3 years after death) 39

Once your child dies, that team of doctors, that whole [hospital] was our home. It’s gone. All of a sudden, now, you’ve lost 2 families. And that’s, and then the third being your, the nurses that were in your home. It’s just empty. Everything’s gone. Your child’s gone. Your family, your, your medical family is gone.. . . And your community’s medical family is gone. And you’re alone. It’s like waking up, and it’s like everyone’s dead” (ACP028) 52

Care of the parent

A second overarching theme was care of the parent which split into two themes: direct support and emotional comfort and compassion. Providing end-of-life care for a child often included ‘care of the parents’ in the form of both practical and emotional support.38,39,42,50 Parents that were well cared for were better able to cope and look after themselves and thus felt better enabled to be a parent.50

Looking after us, so we could better look after Ethan. (Edward – hospital 2) 50

Direct support

Four study reports contributed to this theme. Parents valued professionals who provided direct and practical support such as giving them toiletries, organising transport, ensuring they had cups of tea, food and somewhere to sleep.38,42,50,57 They helped to orientate parents, encouraged breaks, and let them know what facilities were available for them to use.

They were really helpful and then they don’t let you forget to take care of yourself. . . (nurses said) It might be time for you to go home, your nodding off over here [participant laughing] . . .so they make sure I wasn’t like (sic) passing out, and make sure, that you go eat, ‘cause (sic) we tend to forget those things when we’re sitting there. (mother #5) 38

The nurses were just fantastic, they left us alone but at the same time they were there when we needed them, making us tea’ (Mother, W1) 57

Emotional comfort and compassion

Seventeen study reports contributed to this theme. The emotional support offered, by nurses in particular, was acknowledged and appreciated. Being present and providing comfort, especially at very difficult points was important.38,42,50 Other support provided directly to parents included spiritual and pastoral support.38,55,59

[Good staff] sat there and held me while I cried. (Abigail – hospital 2) 50

Many parents were touched when staff showed compassion and sensitivity8,36,38,39,42,43,45,46,48–50,55 and felt comforted by demonstrations of kindness, empathy and emotional responses.8,37,41,42,45,50

There are so many little things you guys have done and really means a lot. We had amazing nurses who really care. I think it was just a phenomenal experience from [the] depths of tragedy (mother, 3 years after death) 39

The ones that helped us through and made a difference were the ones that will remain in our hearts. The ones who took that extra couple of minutes to talk to us, or you know tried to help us believe that there was hope and then when things showed what they were they told us in a compassionate way and I think that separates the good nurse from the bad nurse and the good doctor from the bad doctor those that can cry with you, those that feel for you—but they still have their head on straight. 8

Parents experienced a sense of comfort and even parental pride when healthcare professionals demonstrated a particular or ‘special’ connection with their child.37,47,50 This manifested in several ways, going ‘above and beyond’ such as staying beyond their shifts,37,48,50 or providing non-clinical care such as braiding hair, decorating rooms and reading stories.37,47,48

It was almost comforting to know that [my daughter] had made that much of an impression on them so that [voice breaking] her little short life affected people. (Mother) 37

They told me to go home, get some sleep. My partner couldn’t sleep knowing that our daughter was awake there and we were not there so he went down and the nurse was reading a Winnie the Pooh story to her at 2 o’clock in the morning. You can’t ask for better than that. (Mother) 48

For some parents this level of emotional support meant that it felt like nurses had become part of the family, ‘another mum’42,44 and that they understood them and the situation they were facing better than other friends and relatives.42 Parents were able to have confidence that the nurses would be there for their child when the parents could not be present.44,49

“staff are there for us when we can’t be there” (Imogen, hospital 2) 44

However, some parent’s experiences were made harder when they perceived healthcare staff to be insensitive and lacking empathy. Parents were particularly upset if they did not feel that staff cared about their child.8,39,42,45,50 Particularly distressing was when parents felt that their child’s ‘worth’ was being judged or their lives not valued and treatment decisions were made accordingly.8,50

[the doctor] was just like ‘well, I’ve got more important people to deal with, doesn’t look like Amelia is going to survive, how about we take our resources and put it somewhere else’. (Abigail – hospital 2) 50

He told me there are 6 people working on him, “what do you want”—he kind of led me to believe that it was too much— people working on him. 8

They gave me the impression it was a cost to keep Liam. . . it was like an expense to keep Liam. . . to try again. (Zoe - hospital 4) 50

Confidence in the synthesised findings

Summary GRADE-CERQual review findings are presented in Table 4. The GRADE-CERQual assessments of high or moderate confidence suggest a reasonable representation of parents’ experiences of end-of-life care for their child. For the full GRADE-CERQual assessment table see Supplemental Table 4.

Table 4.

GRADE-CERQual Summary of findings table.

| Summarised review finding | GRADE-CERQual Assessment of confidence | Explanation of GRADE-CERQual Assessment | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROFOUND NEED TO FULFIL PARENTAL ROLE – ESTABLISHING THE PARENTAL ROLE | ||||

| 1 | It was important that new parents of infants receiving end-of-life care established themselves in a parental role and the surroundings of a Neonatal intensive care unit setting can present challenges to this. Physical separation and medical instability of their child was distressing and constraining for parents. For some, this led to hesitation or lack of confidence, with fathers in one study, particularly reporting discomfort at handling such fragile infants. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.40, Thornton et al.41, Falkenburg et al.42, Abraham and Hendriks43 |

| 2 | Encouragement and practical support from staff to hold their baby and provide caregiving enabled parents to establish and enact the parent-child relationship. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.40, Thornton et al.41, Falkenburg et al.42, Abraham and Hendriks43, Butler et al.44 |

| 3 | For parents of Neonatal intensive care unit babies who only lived a short time, it was particularly crucial to maximise time together as this allowed parent to get to know their child and create an identity for them. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Thornton et al.41, Abraham and Hendriks43 |

| PROFOUND NEED TO FULFIL PARENTAL ROLE – MAINTAINING IDENTITY AS A PARENT | ||||

| 4 | Parents with children receiving end-of-life care needed to navigate maintaining their parental role. This relied on developing a collaborative and trusting team relationship with healthcare professionals based on a sense of common purpose and an understanding of each other’s roles. This relationship was fragile and when broken could lead to parents feeling excluded. | High confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, Minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Brooten et al.8, Sedig et al.36, Heller and Solomon37, Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.42, Butler et al.44, Snaman et al.45, Hendricks-Ferguson46, Mitchell et al.47, Monterosso and Kristjanson48, Papadatou et al.49, Butler et al.50, Hannan and Gibson51, Lord et al.52, Rapoport et al.53 |

| 5 | Parents had their own vision of how to express their role in terms of continued levels of involvement in the physical care of their child. Desired levels of involvement varied between parents, with some parents of older children expressing less of a need to be intimately involved in physical care. Parents of chronically ill children more accustomed to providing nursing care were keen to continue this role. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Sedig et al.36, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.40, Falkenburg et al.42, Butler et al.50, Lamiani et al.54 |

| 6 | Parents highlighted a need for space and privacy in order to preserve the family intimacy. Busy wards and unfamiliar intensive care settings provided little escape. Having unrestricted visiting hours and private family spaces enabled families to spend time together. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Brooten et al.8, Sedig et al.36, Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.40, Thornton et al.41, Abraham and Hendriks43, Butler et al.44, Mitchell et al.47, Monterosso and Kristjanson48, Papadatou et al.49, Hannan and Gibson51, Lamiani et al.54, Vickers and Carlisle56, Davies57, Sullivan et al.58 |

| PROFOUND NEED TO FULFIL PARENTAL ROLE – RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR CHILD | ||||

| 7 | Parents were compelled to take some share of the ultimate responsibility for their child’s end-of-life care planning and that this was central to their identity as parents. | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, Moderate concerns regarding adequacy (only two studies contributed to the finding), and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Baughcum et al.39, Abraham and Hendriks43 |

| 8 | Parents wanted healthcare professionals to provide complete, honest and understandable information, while also listening to parents’ views and concerns. Parents openness to planning and discussing end-of-life care varied and it was important that this was handled sensitively and tailored to parents’ needs. | High confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Brooten et al.8, Sedig et al.36, Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.42, Snaman et al.45, Hendricks-Ferguson46, Mitchell et al.47, Monterosso and Kristjanson48, Papadatou et al.49, Butler et al.50, Hannan and Gibson51, Lord et al.52, Rapoport et al.53, Hendriks and Abraham55, Sullivan et al.58 |

| 9 | Most parents wanted to advocate for their child and represent their best interests, and to be absolutely sure that both the healthcare professionals and the parents themselves had done everything they could. Others were overwhelmed and welcomed clinicians taking control, while a few fathers reported relying on their wives/partners to make decisions as they felt they were more involved and better informed. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Brooten et al.8, Sedig et al.36, Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.42, Butler et al.44, Snaman et al.45, Hendricks-Ferguson46, Mitchell et al.47, Papadatou et al.49, Butler et al.50, Hannan and Gibson51, Rapoport et al.53, Lamiani et al.54, Hendriks and Abraham55, Vickers and Carlisle56, Sullivan et al.58 |

| PROFOUND NEED TO FULFIL PARENTAL ROLE – RECONSTRUCTING THE PARENTAL ROLE | ||||

| 10 | Parents’ view of how to express their role could shift with the trajectory of their child’s illness and for some parents, accepting their child had reached the end of their lives, involved moving from a state of ‘doing’ to ‘being’, placing more emphasis on spending time together and supporting their child. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, Minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Abraham and Hendriks43, Butler et al.44, Monterosso and Kristjanson48, Davies57 |

| 11 | For some parents taking their child home or moving into hospice care for end-of-life care, meant regaining control and being in a place where some sense of family life and parenting could return | Moderate confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, Minor concerns regarding coherence, Minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Currie et al.38, Falkenburg et al.40, Hendricks-Ferguson46, Mitchell et al.47, Monterosso and Kristjanson48, Papadatou et al.49, Hannan and Gibson51, Vickers and Carlisle56, Davies57 |

| 12 | For some children, end-of-life comfort care meant being released from the constraints of medical equipment, and so parents had unrestricted access to hold them, sometimes, for the first time. | Moderate confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, Minor concerns regarding coherence, Moderate concerns regarding adequacy (only three studies contributed to the finding), and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Falkenburg et al.40, Thornton et al.41, Lamiani et al.54 |

| PROFOUND NEED TO FULFIL PARENTAL ROLE – CONTINUING PARENTING THROUGH DEATH AND BEYOND | ||||

| 13 | Being prepared for their child’s death as far as was possible, enabled parents to be with their child as they died, to hold them and to say goodbye. | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Brooten et al.8, Sedig et al.36, Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.40, Thornton et al.41, Abraham and Hendriks43, Mitchell et al.47, Butler et al.50, Rapoport et al.53, Lamiani et al.54, Hendriks and Abraham55, Davies57, Sullivan et al.58 |

| 14 | The need to fulfil the parental role did not end when a child died and for those who were able to, spending time with their child’s body was important and helped parents ‘take leave’. Parents who were initially reluctant reflected that they were grateful that this was encouraged by the nursing staff | High confidence | No/Very minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, No/Very minor concerns regarding coherence, No/Very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and No/Very minor concerns regarding relevance | Currie et al.38, Baughcum et al.39, Falkenburg et al.40, Thornton et al.41, Abraham and Hendriks43, Lamiani et al.54, Davies57 |