Abstract

Membrane lipids control the cellular activity of kinases containing the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain through direct lipid-SH2 domain interactions. Here we report development of novel non-lipidic small molecule inhibitors of the lipid-SH2 domain interaction that block the cellular activity of their host proteins. As a pilot study, we evaluated the efficacy of lipid-SH2 domain interaction inhibitors for spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), which is implicated in hematopoietic malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML). An optimized inhibitor (WC36) specifically and potently suppressed oncogenic activities of Syk in AML cell lines and patient-derived AML cells. Unlike ATP-competitive Syk inhibitors, WC36 was refractory to de novo and acquired drug resistance due to its ability to block not only the Syk kinase activity but also its non-catalytic scaffolding function that is linked to drug resistance. Collectively, our study shows that targeting lipid-protein interaction is a powerful approach to developing novel small molecule drugs.

Keywords: Lipid-protein interaction, Src homology 2 domains, Syk inhibitors, acute myeloid leukemia, drug resistance, scaffolding function

INTRODUCTION

Lipid-protein interaction (LPI) plays key regulatory roles in diverse biological processes, including cell signaling 1,2, and dysregulated LPI has been linked to numerous human diseases 3,4. Thus, LPI is an attractive target for novel drug development 5–7. Nevertheless, LPI-targeting drug discovery has been hampered for various reasons. It was initially thought that only those proteins containing canonical lipid-binding domains or motifs, such as pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-containing Akt, specifically interact with membrane lipids 1,8 and that these proteins must be modulated by lipid-like inhibitors that are often difficult to prepare and have undesirable properties, such as low water solubility 7. Structural similarity of these domains within each family1,8 has also made it difficult to design and develop specific inhibitors. Other challenges include lack of full mechanistic understanding of LPI in the natural membrane environment 1,9, the absence of proper small molecule libraries covering the chemical space of LPI interfaces, and a dearth of robust and versatile high-throughput LPI assays 2. This study was designed to address these technical issues and explore the possibility of developing a new class of potent and specific LPI inhibitors.

Our primary strategy is targeting lipid binding of non-canonical membrane binding proteins. Most cell signaling proteins are modular proteins containing one or more protein interaction domain(s) for protein target recognition and regulation 10. The Src homology 2 (SH2) domain is a prototypal protein interaction domain that specifically recognizes the phosphotyrosine (pY) motif of diverse target molecules 11–13. Through genome-wide screening we recently showed that ≈90% of tested human SH2 domains tightly bind lipids in the plasma membrane (PM) 14. Many of them specifically bind a phosphoinositide (PtdInsP), a family of phosphorylated phosphatidylinositol, using the sites that are separate from their pY-binding pockets and can thus bind a PtdInsP and a pY motif coincidently14. Lipid binding of SH2 domains has been shown to be crucial for the enzymatic activity and scaffolding function of their host proteins 14–16.

A large number of tyrosine kinases contain the SH2 domain and these kinases are implicated in diverse human diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and immune disorders and are thus targets for active drug development 17. To date most small molecule kinase inhibitors have been designed to target their ATP-binding pockets 18,19. Many of these ATP-competitive inhibitors have shown clinical benefits but they often suffer from two major drawbacks: low specificity caused by the structural similarity among the ATP-binding sites and the acquired resistance caused by multiple mechanisms, including mutation(s) of the target kinases and activation of alternate signaling pathways 20. As an alternative approach for improved specificity ands potency, we explored the possibility of targeting lipid binding of their SH2 domains, based on the findings that lipid-SH2 domain binding is functionally crucial 14–16 and that lipid binding sites of SH2 domains are highly variable 14.

As a pilot study, we selected as a target spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) that plays a key role in regulation of signaling activities in B and myeloid cells and is implicated in hematologic malignancies21. A number of small molecule ATP-competitive inhibitors of Syk, such as fostamatinib (R788), cerdulatinib (PRT062070), and TAK-659, have thus been developed and evaluated 22. However, they did not produce promising results in the clinical trials due to low specificity and significant cytotoxicity 22. Entospletinib is a second generation Syk inhibitor with higher Syk specificity that showed a promise in treating hematologic malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and chronic lymphoid leukemia 23. However, rapidly acquired drug resistance to entospletinib during the treatment rendered it ineffective 24. Therefore, development of a new type of resistance-defying Syk inhibitor is still an unmet need. In this study, we developed a novel inhibitor for Syk targeting lipid binding of its SH2 domain. It was not only more specific and potent against AML cells than currently available ATP-competitive Syk inhibitors but also suppressed all reported de novo and acquired resistance to Syk inhibitors. This unprecedented inhibitory activity derives from its ability to block both the catalytic activity and the non-catalytic scaffolding function, the latter of which is crucial for AML cell’s resistance to Syk inhibitors.

RESULTS

SH2 domains specifically bind PIP3 using variable sites

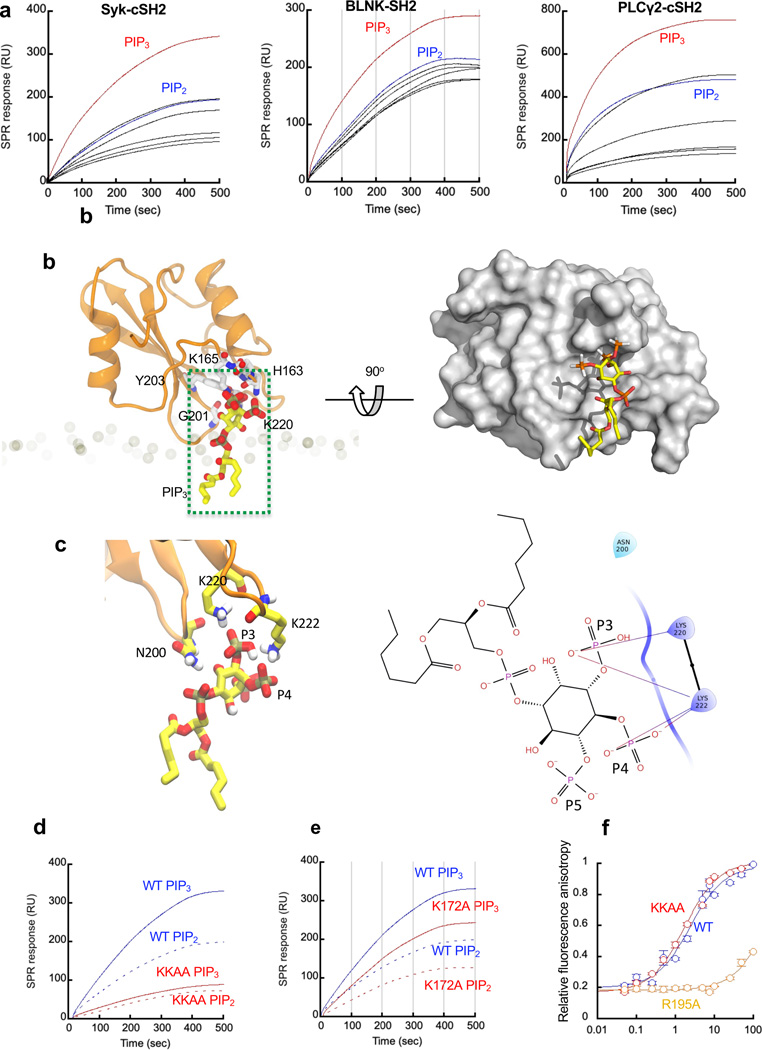

We determined the PtdInsP specificity of SH2 domains of three B cell receptor (BCR) signaling proteins, Syk, B-cell linker (BLNK), phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2) by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis. For Syk and PLCγ2 with two SH2 domains, we only focused on their membrane-binding C-terminal SH2 domains (cSH2) 14. SPR sensorgrams showed that all three SH2 domains preferentially bind phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) over other PtdInsPs, including phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2) (Fig. 1a). Despite numerous studies, the detailed mechanisms of cellular LPI remain elusive 1,9,25 because current technologies do not allow high-resolution structural determination of cytosolic proteins bound to natural lipid bilayers. As a result, it is difficult to rationally design LPI inhibitors based on the available structural information and to validate the mode of their inhibitory actions by structural determination. Molecular dynamic simulations have been employed to fill the gap but most approaches neither fully incorporate the essential features of LPI nor allow rapid survey of the conformational space 9. To overcome these obstacles, we employed advanced membrane-binding simulations using a highly mobile membrane mimetic (HMMM) membrane that allows for rapid lipid diffusion and spontaneous membrane insertion of soluble proteins 26,27. Starting from the free configuration of Syk-cSH228, we simulated its binding to the HMMM membrane containing PIP3 (Extended Data Fig. 1a) and quantified the Syk-cSH2-PIP3 interaction by calculating the localization of each Syk-cSH2 residue with respect to the phosphate moieties of PIP3. We consistently observed multiple interfaces of the Syk-cSH2-PIP3 including various protein residues and multiple PIP3 molecules (Extended Data Fig. 1b, 1c).

Fig. 1. The membrane binding mechanisms of SH2 domains.

a. PtdInsP selectivity of Syk-cSH2, BLNK-SH2, and PLCγ2-cSH2 determined by SPR analysis using POPC/POPS/PtdInsP (77:20:3 in mole ratio) LUVs coated on the L1 sensor chip. The protein concentration was 100 nM for all SPR measurements. PIP3 and PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2) data are shown in red and blue, respectively. Other PtdInsPs (all black) from top are PI(3,4)P2, PI(3,5)P2, PI(3)P, PI(4)P, and PI(5)P (for Syk-cSH2); PI(3,5)P2, PI(3,4)P2, PI(3)P, PI(5)P, and PI(4)P (for BLNK-SH2); PI(3,5)P2, PI(3,4)P2, PI(5)P, PI(3)P, and PI(3)P (for PLCγ2-cSH2). b. A representative binding mode of Syk-cSH2 to a PIP3 molecule in the membrane. Left panel: Syk-cSH2 residues (C and O, N atoms are shown in white, red and blue, respectively) interacting with a PIP3 molecule (C and O, N atoms are shown in yellow, red and blue, respectively) via their side chains (H165, K165, Y203 and K220) or the peptide backbone (G201) are shown in stick presentation and labeled. Phosphorous atoms are shown in tan-colored sticks. Right panel: the structure is rotated 90° for the top of the protein surface to face the membrane. The protein is shown in surface representation to better illustrate the shape of the primary lipid binging site. Notice that Syk-cSH2 can interact with multiple PIP3 molecules when its concentration is high (see Extended Data Fig. 1). c. Expanded view of the PIP3-Syk-cSH2 domain interaction near the 3’ phosphate moiety (P3) of PIP3 (a green box in Fig. 1b). Right panel: Schematic view of predicted hydrogen bonds in this binding mode. Polar and charged (positive) are colored light blue and violet, respectively. H-bonds are shown as arrows. Notice that K220 and K222 are critically involved in P3 recognition, hence PIP3 specificity. d. Selectivity of Syk-cSH2 WT (blue) and K172A (red) for POPC/POPS/PIP3 (77:20:3) (solid lines) over POPC/POPS/PI(4,5)P2 (77:20:3) (broken lines) vesicles determined by SPR analysis. e. The same as c except that K220A/K222A (KKAA) is used in lieu of K172A. f. Affinity of Syk-cSH2 WT (blue), K220A/K222A (KKAA; red) and R195A (orange) for the Igα-derived fluorescent peptide determined by fluorescence anisotropy. Fig. 1a, 1d, and 1e show representative SPR sensorgrams from 3 independent measurements. Each data in Fig. 1f is mean ± SD from 3 independent measurements.

To gain further atomic-level insight, we analyzed the last 50 ns of trajectories obtained from membrane-binding simulations. The analysis showed that Syk-cSH2 remained associated with different phosphate moieties of PIP3 molecules via distinct hotspots (Extended Data Fig. 1d, 1e). Among these hot spots, a shallow cationic cavity composed of H163, K165, Y203, K220, and K222 nicely accommodates the head group of a single PIP3 molecule and make specific contacts with three phosphate moieties (Fig. 1b). In particular, K220 and K222 primarily form hydrogen bonds with the 3’-phosphate group (Fig. 1c), suggesting their essential role in PIP3 specificity. The residues in other hot spots do not make specific contact with the 3’-phosphate group but rather non-specifically interact with other phosphate groups (Extended Data Fig. 1d). For instance, K172, interacts with both 4’- and 5’-phosphate groups of PIP3 (Extended Data Fig. 1f and 1g). Thus, their binding to PIP3 is considered non-specific electrostatic interaction, which does not contribute to PIP3 specificity. Interestingly, we observed no interaction of PIP3 with R195 in the pY-binding pocket, indicating that Syk-cSH2 has distinct binding sites for PIP3 and the pY motif. It should be stressed that the local conformations of the putative PIP3 binding cavity of Syk-cSH2 in the simulated structures (e.g., Fig. 1b) are significantly different from that in the reported solution NMR structure 28, again underscoring the difficulty in predicting the lipid binding site and designing inhibitors targeting the site using solution or crystal structures.

To experimentally validate the predicted Syk-cSH2-PIP3 interaction, we performed mutational analysis. Our SPR analysis showed that the K220A/K222A mutation reduced binding to PIP3-containing vesicles much more significantly than that to PI(4,5)P2 vesicles, causing the mutant to lose PIP3 specificity (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 1h and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, the K172A mutation lowered the affinity of Syk-cSH2 for both vesicles to similar degrees, thereby not altering its PIP3 selectivity (Fig 1e, Extended Data Fig. 1h, and Supplementary Table 1). Lastly, mutation of R195 in the pY-binding pocket to Ala had little effect on membrane binding of Syk-cSH2 (Extended Data Fig. 1h and Supplementary Table 1). We also determined the affinity of Syk-cSH2 WT and these mutants for a fluorescein-labeled pY-containing peptide derived from a B cell co-receptor, Igα, by fluorescence anisotropy as reported previously 14. Results showed that the K220A/K222A mutation did not alter the pY-peptide affinity of Syk-cSH2 whereas the mutation of the pY site (i.e., R195A) lowered the peptide affinity by two orders of magnitude (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Table 1). Collectively, this unprecedented level of consistency between computational and experimental data demonstrates the power and accuracy of our computational prediction of LPI for Syk-cSH2.

PIP3 binding of Syk-cSH2 is important for Syk function

To evaluate the importance of Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding in the cellular function of Syk, we measured the effects of transfecting Syk−/− DT40 B cells29 with full-length (FL) Syk WT and K220A/K222A, respectively. Upon BCR stimulation Syk is thought to be recruited to the BCR signaling complex through interaction of its tandem SH2 domains with phosphorylated B cell co-receptors, Igα and Igβ21. When Syk−/− DT40 cells co-transfected with EGFP-Syk WT and a PIP3 biosensor, mCherry-eMyoX-tPH 30 were stimulated with IgM to phosphorylate Igα and Igβ, both proteins were spontaneously co-localized at the PM (Extended Data Fig. 2a). PM translocation of EGFP-Syk WT was greatly suppressed either by elimination of IgM or by a Class I PI3K inhibitor, GDC-0941 (Extended Data Fig. 2b, 2c), showing that it requires both Igα/β phosphorylation and PIP3 at the PM. Importantly, EGFP-Syk-K220A/K222A largely remained in the cytosol even in stimulated cells (Extended Data Fig. 2d), verifying the importance of Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding for PM recruitment of Syk.

We also measured the increase in cellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) as a readout of BCR signaling activity (Extended Data Fig. 2e). IgM stimulation did not raise [Ca2+]i in Syk−/− DT40 cells. whereas it sharply enhanced [Ca2+]i in Syk−/− DT40 cells stably expressing. Under the same conditions, a much higher [Ca2+]i response was observed in Syk−/− DT40 cells stably expressing Syk WT than in those expressing K220A/K222A although their expression levels were comparable. Collectively, these results show that Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding is pivotal for both PM recruitment and BCR signaling activity of Syk and suggest that inhibition of Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding should have strong biological effects.

SH2 domain-lipid binding can be specifically inhibited

We also computationally predicted and experimentally validated the PIP3-binding sites of BLNK and PLCγ2 (Extended Data Fig. 3, 4). The PIP3-binding sites of the three SH2 domains are highly variable in terms of the location and morphology but also share common properties: i.e., they are in general shallower and wider than those from canonical PIP3-binding PH domains 31. This finding hinted that some non-lipidic small molecule scaffolds may efficiently bind these pockets and inhibit SH2-PIP3 binding. Using the PIP3-binding pockets of the SH2 domains as templates, we thus performed high-throughput molecular docking of a series of candidate compounds with different scaffolds. At least twelve different scaffolds partially occupy the primary PIP3 binding groove of Syk-cSH2 (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting small molecules containing these moieties may block the Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding at the membrane. Guided by this computational analysis, we constructed a library of ≂600 molecules derived from these scaffolds as potential inhibitors of PIP3-SH2 domain binding by modular synthetic approaches 32,33.

We also optimized our fluorescence quenching-based lipid-binding assay 34 for high-throughput screening of these molecules. The clear separation of positive and negative control data and the average Z’-factor of 0.7 supported the robustness of our system for high-throughput screen of PIP3-SH2 interaction inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). Multiple rounds of screening yielded lead compounds for each SH2 domain (Supplementary Fig. 3). Unlike competitive inhibitors of enzymes, these molecules caused varying degrees of maximal inhibition (Imax) at saturating concentrations. It is because the membrane binding sites of soluble proteins typically contain a specific lipid-binding pocket surrounded by the non-specific membrane-contact surface 35, which also contributes to the overall membrane affinity of these proteins 35 but would not be blocked by inhibitors targeting specific lipid pockets. We thus defined two parameters to assess their inhibitory efficacy: Imax and the concentration required for half-maximal inhibition (IC50). The lead compounds (VG354, VG594, and VG370 (1–3)) had IC50 values around 500 nM and achieved 40–50% Imax and showed a high degree of specificity even before optimization (Supplementary Fig. 3). We further tested their specificity in Raji B lymphocytes by measuring their effects on the BCR signaling axis (i.e., Syk-BLNK-PLCγ2) by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2a, an inhibitor of Syk (VG354), which acts at the top of the signaling axis, suppressed phosphorylation of Syk (pY525/pY526), BLNK (pY96) and PLCγ2 (pY759). Furthermore, the BLNK-SH2 inhibitor (VG594) blocked the phosphorylation of BLNK and PLCγ2 without a significant effect on Syk whereas the inhibitor for downstream PLCγ2 (VG370) only suppressed PLCγ2 phosphorylation. These results verify the specificity of these SH2 domain inhibitors under physiological conditions.

Fig. 2. Small molecule inhibition of the cellular activity of Syk, BLNK, and PLCγ2.

a. Specific inhibition of Syk, BLNK, and PLCγ2 by VG354, VG594, and VG370, respectively, in Raji B cells. VG354 inhibits phosphorylation of Syk (pSyk: pY525/pY526), BLNK (pBLNK; pY96), and PLCγ2 (pPLCγ2; pY759), VG594 suppresses pBLNK and pPLCγ2, while VG370 blocks only pPLCγ2. b. Inhibition of Syk by three optimized Syk inhibitors, WC35, WC36, and WC38, respectively, in Raji B cells. For Fig 2a and 2b, each image is a representative of 3 independent experiments. For each protein, both the phosphorylated (pX = pSyk, pBLNK, and pPLCγ2) and total protein (X = Syk, BLNK, and PLCγ2) were immunoblotted and their band density quantified. The ratios of the gel density of the pX band to that of the total X band (pX/X) were then normalized against the value for no treatment (−) and shown below the immunoblotting data. Error bars indicate SD. For pSyk/Syk, p = 0.79 (DMSO), 0.0053 (VG354), 0.44 (VG594), 0.96 (VG370), 0.0047 (WC36), 0.0054 (WC35), 0.0041 (WC38). For pBLNK/BLNK, p = 0.81 (DMSO), 0.00053 (VG354), 0.00047 (VG594), 0.75 (VG370), 0.00039 (WC36), <0.0001 (WC35), 0.00062 (WC38). For pPLCγ2/pPLCγ2, p = 0.92 (DMSO), 0.0037 (VG354), <0.0001 (VG594), <0.0001 (VG370), <0.0001 (WC36), 0.00017 (WC35), 0.00023 (WC38). Cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml IgM. The inhibitor concentration was 5 μM for all measurements. DMSO was used as a negative control for inhibitors and GAPDH as a gel loading control. c. Superimposition of PIP3 and WC36 docked into the primary lipid binding groove of Syk-cSH2 in the membrane environment. In its binding mode, WC36 snuggles deeper into the groove than the PIP3 headgroup, leading to tight binding and effective inhibition of PIP3 binding. Both enantiomers of WC36 were able to bind to the same PIP3 pocket but only one enantiomer is shown for illustration. d. Schematic view of the Syk-cSH2–WC36 interactions. Polar, charged (positive), and hydrophobic residues are colored light blue, violet, and green, respectively. H-bonds are shown as arrows, with the arrowhead that indicates the H-bond acceptor portion.

For Syk-cSH2, we optimized VG354 by the structure-activity relationship analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Out of 39 derivatives of VG354, we found three structurally related compounds, WC35, WC36, and WC38 (4–6), with greatly improved inhibitory activity (Supplementary Fig. 4b). These compounds inhibited binding of neither BLNK-SH2 nor PLCγ2-cSH2 to PIP3-containing vesicles, underscoring their specificity (Supplementary Table 3). In Raji B cells, WC35, WC36, and WC38 effectively suppressed phosphorylation of all BCR signaling proteins (Fig. 2b). Their Imax and IC50 values (Extended Data Fig. 5a, 5b, Supplementary Table 3) show that they potently block BCR-mediated activation of Syk in B cells. Molecular docking calculations suggested that WC36 might tightly bind to the primary PIP3 pocket of Syk-cSH2 in an orientation that would block the entry of PIP3 to the pocket (Fig. 2c). In this binding mode, WC36 makes multiple hydrogen bonds with the residues in the pocket (Fig. 2d).

ZAP-70 is another Syk family kinase primarily found in T cells and is structurally and functionally similar to Syk36. In the vesicle binding assay, WC35, WC36, and WC38 did not inhibit binding of ZAP-70-cSH2 to PIP3-containing vesicles, showing their selectivity for Syk-cSH2 over ZAP-70-cSH2 (Supplementary Table 3). We also treated Jurkat T cells that contain Zap70 in lieu of Syk. Immunoblotting showed that WC35, WC36, and WC38 did not inhibit phosphorylation of ZAP-70 (Extended Data Fig. 5c, Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, entospletinib, which is currently the most potent and specific ATP-competitive Syk inhibitor22, significantly inhibited ZAP-70 phosphorylation. As far as the off-target toxicity is concerned, our inhibitors thus offer an important therapeutic advantage over entospletinib. This also underscores the major advantage of targeting highly variable lipid binding sites of the SH2 domains over targeting structurally similar ATP binding sites of kinase domains.

Syk inhibitors are potent against AML cells and drug-resistant

Clinical efficacy of Syk inhibitors for hematologic malignancies has been evaluated as either monotherapy or combined therapy with other kinase inhibitors or chemotherapy agents 22. AML is a cancer of the myeloid line of blood cells, characterized by the rapid proliferation of poorly differentiated myeloid cells that build up in the bone marrow and blood and inhibit normal hematopoiesis 37,38. AML had been typically treated with chemotherapy but new therapy targeting tyrosine kinases has been introduced in past few years 39,40. This therapy is based on the finding that in up to one third of AML cells FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor (FLT3) is constitutively activated through mutation, leading to proliferation and survival of AML cells 40,41. Syk inhibition has recently emerged as a promising targeted approach for AML patients with the hyperactivated FLT3 42 based on the report that hyperactivated FLT3 in AML cells still depends on Syk for driving myeloid neoplasia in mice 43 (Extended Data Fig. 6). As with targeted therapy for other kinases 20, however, Syk-targeted therapy for AML is associated with the rapid emergence of resistance with alternate activation of the RAS–RAF-MEK–ERK signaling pathway as a primary mechanism 24. Thus, RAS-mutated AML cells show de novo resistance to Syk inhibitors whereas AML cells with WT RAS quickly develop acquired resistance through mutation(s) of RAS or other proteins regulating RAS activity 24.

We first assessed the efficacy of our Syk LPI inhibitors against MV4-11 AML cells that harbor WT RAS and oncogenic FLT3 mutation 44. As with other AML cells, oncogenic signaling by the mutated FLT3 in MV4-11 cells still requires Syk activation43. The mechanism of Syk activation in AML cells is not fully understood but it has been reported that stimulation of Fcγ receptor I (FcγRI) or integrin receptor activates Syk in several AML cells lines and induces cell survival and proliferation 41 (Extended Data Fig. 6). We thus activated Syk signaling in MV4-11 with the FcγRI-specific antibody, IgG2, which strongly induced phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3/5, and ERK1/2 (Fig 3a). WC36 and WC38 suppressed their phosphorylation as potently as entospletinib while WC35 was modestly less active. When the effects of the inhibitors on the cell proliferation activity were measured by the XTT assay, WC35 and WC36 were modestly more active than WC38 and entospletinib (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 3). Overall, against MV4-11 cells these compounds showed potency comparable to entospletinib.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of the signaling activity and proliferation of MV4-11 AML cells by Syk-cSH2 inhibitors.

a. Western blot analysis of IgG2-stimulated (10 ng/ml for 10 min) phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3/STAT5 and ERK1/2 after MV4-11 cells were pre-treated with 5 μM of WC35, WC36, WC38, and entospletinib (ENTO) overnight. b. Dose dependent inhibition of the proliferation of MV4-11 cells by WC35 (open triangles), WC36 (open circles), WC38 (open squares), and entospletinib (closed circles) measured by the XTT assay. Imax and IC50 values were determined by non-linear least-squares analysis of data using the equation: I = Imax / (1 + IC50 / [inhibitor]) where I indicates % inhibition at a given inhibitor concentration ([inhibitor]). c. Inhibition of IgG2-stimulated phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3/STAT5 and ERK1/2 in entospletinib-resistant MV-4–11 cells by 5 μM of WC35, WC36, and WC38. For Fig. 3a and 3c, each image is a representative of 3 independent experiments. For each protein, both the phosphorylated (pX = pSyk, pSTAT5, pSTAT3, and pERK1/2) and total protein (X) were immunoblotted and their band density values quantified. The ratios of the gel density of the pX band to that of the total X band (pX/X) were then normalized against the value for DMSO treatment (a) or no treatment (−) (c) and shown below immunoblotting data. Error bars indicate SD’s. DMSO was used as a negative control for inhibitors and GAPDH as a gel loading control. Naïve cells (a): For pSyk/Syk, p = 0.00081 (WC35), 0.00078 (WC36), 0.00084 (WC38), 0.00082 (ENTO). For pSTAT5/STAT5, p = 0.00064 (WC35), 0.00065 (WC36), 0.00065 (WC38), 0.00063 (ENTO). For pSTAT3/STAT3, p = 0.0012 (WC35), 0.0012 (WC36), 0.0011 (WC38), 0.0012 (ENTO). For pERK1/2/ERK1/2, p = 0.00081 (WC35), 0.0012 (WC36), 0.00016 (WC38), 0.00055 (ENTO). Resistant cells (c): For pSyk/Syk, p = 0.15 (DMSO), 0.0024 (WC35), 0.0020 (WC36), 0.0031 (WC38). For pSTAT5/STAT5, p = 0.24 (DMSO), 0.0017 (WC35), 0.0013 (WC36), 0.0016 (WC38). For pSTAT3/STAT3, p = 0.23 (DMSO), 0.00060 (WC35), 0.0023 (WC36), 0.023 (WC38). For pERK1/2/ERK1/2, p = 0.592 (DMSO), 0.0040 (WC35), 0.0018 (WC36), 0.19 (WC38). d. Dose dependent inhibition of the proliferation of entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells by WC36 and entospletinib. Data in Fig. 3b and 3d are means ± SD’s from triplicate measurements.

We then put selection pressure on MV4-11 cells by growing them under chronic treatment of inhibitors with gradually increasing concentrations from 0.5 to 5 μM over 10 weeks according to the reported protocol 24. Entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells started to emerge after 4 weeks under these conditions and those surviving cells were able to proliferate in the presence of 5 μM entospletinib. It was reported that ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 in entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells were activated by alternate signaling pathways bypassing Syk kinase activity 24. Consistent with this notion, immunoblotting analysis showed that 5 μM entospletinib could not inhibit phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 in resistant MV4-11 cells (Supplementary Fig. 5a, 5b). In contrast, 5 μM WC36 potently suppressed the phosphorylation and activation of Syk, ERK1/2, and STAT3/5 in entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells (Fig. 3c). WC35 and WC38 were significantly less active than WC36 in these cells. The XTT assay also showed that entospletinib could not effectively suppress the proliferation of these cells (Imax ≤ 50%) even at high concentrations (i.e., ≥20 μM) whereas WC36 potently inhibited proliferation of these cells (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table 3). We then checked if MV4-11 cells could acquire resistance to WC36. Interestingly, we could not detect any surviving MV4-11 cells under the same conditions in which they developed resistance to entospletinib, indicating that MV4-11 cells could not develop resistance to WC36. This was not due to non-specific cytotoxicity of WC36 because 0.5–5 μM of WC36 showed a minimal effect on cell viability of Raji B cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c). These results demonstrate that WC36 potently inhibits the signaling pathways leading to acquired resistance to entospletinib. They also suggest that Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding is still crucial for the Syk kinase-independent signaling pathways leading to entospletinib resistance.

High efficacy of WC36 against entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells also suggested that it might be active against other RAS-mutated AML cells. We thus measured the efficacy of our inhibitors and entospletinib against RAS-mutated HL60 cells. As reported previously 24, entospletinib could not suppress phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 in HL60 cells (Fig. 4a, 4b). However, WC36 was potent against phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and STAT3 under the same conditions. Also, WC36 potently suppressed the proliferation of HL60 cells while entospletinib was ineffective (Fig. 4c), indicating that WC36 is also refractory to de novo resistance.

Fig. 4. Suppression of HL-60 and patient-derived AML cells by Syk-cSH2 inhibitors.

a. Inhibition of IgG2-stimulated (10 ng/ml for 10 min) phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3, STAT5 and ERK1/2 in HL-60 cells by entospletinib (ENTO), WC36, WC35, and WC38 (5 μM each). DMSO was used as a negative control and GAPDH as a gel loading control. The image is a representative of 3 independent experiments. b. Quantification of immunoblotting data in Fig. 4a. See Fig. 3a for data analysis. Error bars indicate SD. For pSyk/Syk, p = 0.96 (DMSO), 0.16 (ENTO), 0.0040 (WC36), 0.0095 (WC35), 0.034 (WC38). For pSTAT5/ STAT5, p = 0.94 (DMSO), 0.146 (ENTO), 0.0011 (WC36), 0.0016 (WC35), 0.0007 (WC38). For pSTAT3/STAT3, p = 0.47 (DMSO), 0.62 (ENTO), 0.0022 (WC36), 0.016 (WC35), 0.060 (WC38). For pERK1/2/ERK1/2, p = 0.55 (DMSO), 0.80 (ENTO), 0.0083 (WC36), 0.0094 (WC35), 0.018 (WC38). c. Dose dependent inhibition of the proliferation of HL-60 cells by WC36 and entospletinib measured by the XTT assay. See Fig. 3b for data analysis. Data represent means ± SD’s from triplicate measurements. d. Inhibition of phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3/5 and ERK1/2 in patient-derived primary AML cells by WC36 (5 μM). Cells were cultured overnight in the presence of CD34+ cytokine supplement. DMSO was used as a negative control. Data are from single experiments with four independent patient samples. e. Quantification of immunoblotting data in Fig. 4d. (pX/totalX) data for each protein were normalized against the average value of DMSO controls. Means ± SD’s from 4 patients were shown for each protein. p = 0.01, 0.0014, 0.03, 0.0046 for Syk, STAT5, STAT3 and ERK1/2. f. Inhibition of the proliferation of four patient AML cells by WC36 measured by the colony growth assay. The number of colonies after WC36 treatment was normalized to the enumerated colonies after DMSO treatment. Means ± SD’s from 4 patients were shown. p <0.0001.

To test the clinical benefit of these desirable inhibitory properties of WC36, we tested its efficacy against primary myeloid cells collected from AML patients with different genetic backgrounds (Supplementary Table 4). WC36 potently inhibit phosphorylation of Syk, ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 in AML cells from 4 patients refractory or relapsed following standard AML therapies (Fig. 4d and 4e) and also suppressed colony formation of these cells (Fig. 4f). Collectively, these results demonstrate that our new inhibitor targeting Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding not only is specific and potent in suppressing diverse AML cells but also offers major clinical advantages over conventional Syk inhibitors targeting the kinase domain in that it suppresses both de novo and acquired drug resistance by AML cells.

Scaffolding function of Syk is essential for drug resistance.

To understand why WC36 is refractory to the acquired drug resistance response by AML cells while entospletinib is highly susceptible, we performed two lines of experiments. First, shRNA-mediated suppression of Syk in entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells abrogated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and STAT3/5, demonstrating that Syk is still required for their activation in these cells (Fig. 5a). Both WT and Y525A/Y526A, a kinase-inactive mutant 45, rescued phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 when reintroduced into Syk-deficient MV4-11 cells whereas K220A/K222A could not (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding is involved in and essential for non-catalytic activation of ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 by Syk in these cells.

Fig. 5. Signaling function of Syk in entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells determined by genetic modulation.

a. Effect of shRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous Syk in MV4-11 cells on phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3/STAT5 and ERK1/2. A scrambled RNA was used as negative control (NC) and three shRNA’s (1–3) were used for knockdown. b. Entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells were treated with shRNA to suppress the expression of endogenous Syk (4 right lanes). These cells were then transfected (knock-in: KI) with exogenous Syk-WT, Syk-Y525A/Y526A (kinase-inactive mutant), and Syk-K220A/K222A (PIP3 binding-deficient mutant) genes that carry silent mutations to avoid gene suppression by Syk ShRNA. Phosphorylation of Syk, STAT3/5, and ERK1/2 in these cells was then monitored before and after stimulation with IgG2 (10 ng/ml for 10 min). The expression level of each protein in all analyzed cells was comparable as shown in total protein blotting data. GAPDH was used as a gel loading control. c. Scaffolding function of Syk and its inhibition by WC36. Immunoprecipitation (IP) with the anti-Syk antibody showed that Syk interacted with STAT3/5 and ERK1/2, which was potently inhibited by 5 μM WC36, but not by 5 μM entospletinib in both entospletinib (ENTO)-resistant and naïve MV4-11 cells. The expression level of RAS was much lower in naïve MV4-11 cells than in entospletinib-resistant cells (see input). Also, RAS was included in the Syk complex only in entospletinib-resistant cells. All shown gel images are representative of 3 independent measurements. For Fig. 5a and 5b, immunoblotting data were quantified as described in Fig. 3a, normalized against no treatment (⏤) (a) and IgG2 treatment only (b), and displayed below immunoblotting data. Error bars indicate SD’s. p values were calculated against negative control (a) and negative control + IgG2 (b), respectively. Fig. 5a: For pSTAT5/STAT5, p = 0.28 (NC), 0.00023 (1), 0.00029 (2), <0.0001 (3). For pSTAT3/STAT3, p 0.18 (NC), 0.00039 (1), 0.00068 (2), 0.00058 (3). For pERK1/2/ERK1/2, p = 0.49 (NC), 0.0035 (1), 0.0039 (2), <0.0032 (3). Fig. 5b: For pSyk/Syk, p = 0.32 (WT), 0.00097 (Y525/526A), 0.0017 (K220/222A). For pSTAT5/STAT5, p = 0.077 (WT), 0.34 (Y525/526A), 0.0015 (K220/222A). For pSTAT3/STAT3, p = 0.17 (WT), 0.15 (Y525/526A), 0.00082 (K220/222A). For pERK1/2/ERK1/2, p = 0.53 (WT), 0.48 (Y525/526A), 0.0012 (K220/222A).

We then performed immunoprecipitation of Syk in entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells to test if Syk serves as a scaffolding protein. Immunoblotting analysis showed that STAT3/5, RAS, ERK1/2, and FLT3 were co-precipitated with Syk (Fig. 5c). These co-immunoprecipitation signals were not due to non-specific backgrounds as demonstrated by control experiments with beads (Supplementary Fig. 6). Most importantly, 5 μM WC36 greatly suppressed co-precipitation whereas 5 μM entospletinib did not. We also found that FLT3, ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 were co-precipitated with Syk in naïve MV4-11 cells. However, RAS was not found in the immuno-precipitated complex and the RAS expression level was much lower in these cells than in entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells (see input in Fig. 5c). Again, 5 μM WC36 greatly suppressed the scaffolding function of Syk whereas 5 μM entospletinib had little to no effect in naïve MV4-11 cells. Collectively, these data show that Syk serves as a scaffold protein that interacts with FLT3, ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 directly or via an adaptor protein(s) and suggest that this scaffolding activity might be essential for acquired resistance to ATP-competitive Syk inhibitors. WC36 is uniquely refractory to acquired resistance because it effectively blocks the scaffolding function of Syk, which entospletinib could not.

WC36 specifically inhibits Syk in AML cells.

To prove that WC36 directly binds and specifically inhibits Syk in AML cells, we performed two independent experiments. First, we generated Syk-cSH2 mutants that might have the same membrane binding activity as WT but might not be inhibited by WC36. Our computation suggested that WC36 binds deeper to the primary lipid pocket than PIP3 and that some residues, most notably E164, in the pocket are exclusively involved in WC36 binding (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 7a). We thus prepared four mutants of E164 and measured their membrane binding activity by the fluorescence quenching assay. Among these mutants, E164D had the same affinity as WT (Extended Data Fig. 7b) but unlike WT was not inhibited by up to 5 μM WC36 (Extended Data Fig. 7c). E164Q was also refractory to WC36 inhibition although it had slightly lower membrane affinity than WT. When the full-length E164D and E164Q, respectively, were introduced into Syk-deficient MV4-11 cells, WC36 did not inhibit phosphorylation of these mutants and ERK1/2 (Fig. 6a and 6b). In contrast, WC36 potently suppressed phosphorylation of Syk WT and ERK1/2 when Syk WT was added back to the Syk-deficient AML cells.

Fig. 6. Cellular target validation of WC36.

a. Inhibition of Syk WT and WC36-binding site mutants by WC36. Entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 cells were treated with shRNA to suppress the expression of endogenous Syk and then transfected with exogenous Syk-WT and four Syk mutant genes, respectively. These constructs harbor silent mutations to avoid gene suppression by Syk shRNA. Phosphorylation of Syk and ERK1/2 in these cells was then monitored before and after treatment with 5 μM WC36 overnight. The expression level of each protein in all analyzed cells was comparable as shown in total protein blotting data. b. The immunoblotting data were quantified as described in Fig. 3a and normalized against no inhibitor control (⏤) for WT. Error bars indicate SD’s. For pSyk/Syk, p = 0.034 (WT), 0.00062 (E164K), 0.026 (E164A), 0.65 (E164D), 0.93 (E164Q). For pERK1/2/ERK1/2, p = 0.036 (WT), 0.00099 (E164K), 0.028 (E164A), 0.63 (E164D), 0.93 (E164Q). c. Left panel: Western blot analysis of WC36B-binding proteins captured by streptavidin beads pull-down. Biotin was used as a negative control. Right panel: Western blot analysis of WC36B-binding proteins captured by streptavidin beads pull-down in the presence of WC36 (10 μM), entospletinib (10 μM), and ATP (1 mM), respectively. GAPDH was used as a gel loading control. All shown gel images are representative of 3 independent measurements.

We also prepared a biotinylated derivative of WC36 (WC36B) (43) (Extended Data Fig. 7d) and incubated MV4-11 cells with 5 μM WC36B for 24 h, enriched the WC36B-bound proteins by pulldown with streptavidin beads, and analyzed the captured proteins by immunoblotting. Clearly, the Syk band was visible in the blot (Fig. 6c), demonstrating that WC36B targets Syk in MV4-11 cells. We also performed the WC36B-streptavidin pull down assay in the presence of WC36, entospletinib, and ATP, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6c (right panel), only WC36 was able to compete with WC36B for Syk binding, displacing Syk from the immobilized WC36B. This shows that WC36 binds specifically to the lipid-binding pocket, but not to the ATP-binding pocket, of Syk. This competition result also precludes the possibility that WC36 binds to Syk covalently due to the presence of α-diazo ester functionality (see Fig. 2d).

To verify the specificity of WC36B-Syk binding, we then performed mass spectrometry-based proteomics analysis of WC36B-binding cellular proteins captured by streptavidin beads using biotin as a negative control. Comparative analysis of WC36B- and biotin-bound proteins showed that Syk is the single major protein that is captured by the WC36 pharmacophore (Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 5). Although several other proteins were also identified in the WC36B-captured mixture, they were found in much lower levels than Syk. Altogether, these results verify the cellular specificity of WC36-Syk interaction.

DISCUSSION

Despite their potentials, developing LPI inhibitors as drugs remain elusive. The present study takes a new approach of targeting the lipid binding sites of SH2 domains. The SH2 domains of key B cell signaling proteins, Syk, BLNK, and PLCγ2, tightly bind PIP3 in the PM, which is crucial for their B cell signaling activity. Our computational approach rapidly samples a large number of membrane-bound protein conformations in a realistic membrane environment, thereby yielding the atomic-level insight into how these SH2 domains interact with PIP3 in the membrane. Importantly, unlike PIP3-binding PH domains that have similar deep cationic pockets 1,8, the SH2 domains possess highly variable, shallower and wider PIP3-binding grooves, suggesting that they may be specifically targeted by non-lipidic small molecules. The computational analysis also enabled us to generate a new small molecule library for LPI inhibitors and optimize them through the structure-activity relationship analysis. Despite its relatively small size, the utility of our new library is validated by the successful identification of selective inhibitors for all three tested SH2 domains. Furthermore, optimization of the lead compound for Syk yielded WC36 with exceptional inhibitory activity.

Dysregulation of Syk in different hematologic cells leads to various diseases, including cancer and autoimmune diseases and thus Syk has been an attractive target for drug development 22. Most of currently available Syk inhibitors, including entospletinib, target its ATP-binding site in the kinase domain 22. WC36 is modestly more potent than entospletinib in Raji B cells and AML myeloblast cells but it is much more specific than entospletinib as demonstrated by its specificity for Syk over ZAP-70. Most importantly, WC36 is superior to entospletinib in terms of invulnerability to both de novo and acquired drug resistance. First, WC36 is effective against RAS-mutated HL-60 AML cells that shows de novo resistance to entospletinib. Second, MV4-11 AML cells do not develop acquired resistance to WC36 under the same conditions they readily develop resistance to entospletinib 24. Furthermore, WC36 can potently inhibit those AML cells that have already developed resistance to entospletinib. Entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 AML cells have acquired an ability to activate ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 and proliferate independently of the Syk kinase activity, thereby making Syk kinase inhibitors ineffective. Our results show that entospletinib-resistant MV4-11 AML cells still depend on the presence of Syk for their survival as their proliferative signaling activity is abrogated by shRNA-based Syk knockdown. Importantly, the fact that this Syk knockdown can be fully rescued by a kinase-inactive Syk mutant, but not by a PIP3 binding-deficient Syk mutant, shows that the PIP3-mediated non-catalytic activity of Syk is crucial for a new signaling pathway leading to activation of ERK1/2 and STAT3/5 and resistance to entospletinib. In the resting state, Syk is autoinhibited by intramolecular tethering by interdomain regions which occludes the kinase domain and prohibits the scaffolding function by the SH2 domains (Extended Data Fig. 6). Our results show that PIP3-dependent membrane binding of Syk is necessary and sufficient for inducing conformational changes of Syk to activate its scaffolding function even when its active site is blocked (Extended Data Fig. 6). They also suggest that non-catalytic scaffolding activity of Syk coordinates MAP kinase and STAT signaling networks that lay the foundation for the acquired resistance mechanism to entospletinib (Extended Data Fig. 6). It is well known that many non-receptor tyrosine kinases, most of which contain the SH2 domain, serve as scaffolding proteins11–13. Based on our previous and current studies showing that lipids coordinate and regulate SH2 domain-mediated scaffolding function of kinases 14–16, we speculate that it is common for cells to take advantage of their lipid-mediated scaffolding function to develop resistance to their active site-directed inhibitors. Most importantly, our study shows that blocking SH2-lipid interaction is a highly efficient approach to suppressing all cellular deregulation caused by SH2 domain-containing proteins. The fundamental and essential roles of SH2 domain-lipid interaction in diverse signaling cascades would make it difficult for cells to develop resistance to SH2 domain-lipid binding inhibitors because any escape mutation or alternate mechanism would lead to cell dysfunction and death.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates that targeting lipid binding of SH2 domain-containing kinases is a promising new approach to developing novel small molecule drugs. Our Syk inhibitor represents the first successful development of a non-lipidic LPI inhibitor for kinases. We expect that our new approach of targeting drug resistance at the source will yield potent, specific, and resistance-proof inhibitors for many other kinases harboring the SH2 domain. A comprehensive study on these kinases is currently under way to test this notion.

METHODS

Materials

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids.1,2-dipalmitoyl derivatives of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2), phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-bisphosphate (PIP3), and other phosphoinositides were from Cayman Chemical Co. N-dimethylaminoazo-benzenesulfonyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (dabsyl-PE) was synthesized as described 34. The custom designed peptide was purchase from AlanScientific. shRNA’s for human Syk were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and the transfection reagent JetPRIME was from Polyplus transfection. Antibodies against phospho-Syk (pS465/pS467), STAT3, phospho-STAT3 (pY705), STAT5, phospho-STAT5 (pY694), ERK1/2, and phospho-ERK1/2 (pT202/Y204) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. Syk and BLNK antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The GAPDH antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. Entospletinib and GDC-0941 were purchased from MedChemPress and Selleckchem, respectively. Jurkat, MV4-11, and HL60 cells were purchased from ATCC.

Protein expression and purification

All SH2 domain constructs were cloned into the pRSET-B vector, were expressed as soluble proteins in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS (Novagen) cells with an N-terminal polyhistidine and a C-terminal EGFP tag. Cells were grown at 37 °C in 2 L of Luria broth containing either 100 μg/ml ampicillin or 50 μg/ml kanamycin, and protein was induced with 1 mM isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside at 18 °C for 12 h when the OD600 reached ~0.6. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 × g at 4 °C, and the pellets were stored at −80 °C. Frozen pellets were thawed and resuspended in ice-cold 50 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The suspension was sonicated on ice to disrupt cells. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, an insoluble pellet was discarded and the clear supernatant was filtered using a 0.45-μm syringe filter. The supernatant was gently shaken with 2 ml of Ni-NTA resin (50% slurry) (Marvelgent Biosciences) at 4 °C for 1 h, and the resin was then packed into a column. The resin was washed with 50 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 160 mM NaCl, and 40 mM imidazole, pH 7.4. The protein was eluted with 10 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 160 mM NaCl, and 300 mM imidazole, pH 7.4. Protein was stored at 4°C.

Lipid vesicle preparation

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) with 100-nm diameter were prepared by mixing the lipid solutions in chloroform according to the final lipid composition and the solvent was evaporated under the gentle stream of nitrogen gas. 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 M NaCl was added to the lipid film to adjust the final lipid concentration, and the mixture was vortexed for 1 min, and sonicated in a sonicating bath for 1 min to break multilamellar vesicles. LUVs were prepared by multiple extrusion through a 100-nm polycarbonate filter (Avanti) using a Mini Extruder (Avanti).

Surface plasmon resonace analysis

All SPR measurements were performed at 23°C in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 M NaCl using a lipid-coated L1 chip in the BIACORE X-100 system (GE Healthcare) as described previously 30,46. LUVs of POPC/POPS/PtdInsP (77:20:3) and POPC were used as the active surface and the control surface, respectively. Sensorgrams were collected for both membrane association and dissociation but the only the association phases were further analyzed because the dissociation phases were often too slow for analysis. All steady-state SPR measurements were carried out for more than 10 different concentrations within a 10-fold range of the Kd of the proteins, while maintaining the slow flow rate of injection of protein (i.e., at 5–10 μl/min) to provide enough time to reach the RU values of the association phase to the nearest its equilibrium value (Req). For Kd determination, sensorgrams obtained at varying protein concentrations were analyzed assuming a Langmuir-type binding between the protein (P) and protein binding sites (M) on vesicles (that is, P + M↔PM). The Req values were plotted against the protein concentrations (Po), and the Kd was established by nonlinear least squares analysis of the binding isotherm using the equation, Req = Rmax /(1 + Kd/Po) where Rmax indicates the maximal Req value. The average and standard deviation values of Kd were obtained from three or more measurements.

Fluorescence quenching assay and small molecule inhibitor screening

The membrane-binding assay is based on fluorescence quenching of EGFP fused to a SH2 domain by a dark quencher containing lipid, dabsyl-PE, incorporated in lipid vesicles. The plate reader assay was performed using the Synergy™ Neo spectrofluorometer at 25°C. Nontreated black polystyrene 96-well plates (Corning) were used. Protein (10–50 nM) with the increasing concentration of vesicles with a given lipid composition in 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 M NaCl was added to each row of wells and the EGFP fluorescence emission at 516 nm was measured with excitation set at 485 nm. Z’ factor for the assay system was determined as described 47. Imax and IC50 values of inhibitors were determined using the equation, I = Imax /(1 + IC50 / [I]) where I and [I] indicate %inhibition and inhibitor concentration, respectively. The average and standard deviation values were obtained from triplicate determinations.

Fluorescence anisotropy assay for SH2-pY peptide binding

The fluorescein-6-aminohexanoyl (F-Ahx)-labeled Igα peptide (F-Ahx-YDMTTpSGpSGpSGLPLL) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to yield 1 mg/ml stock solution. The peptide solution was diluted to 1–10 μM with 20 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.9, containing 160 mM NaCl for binding studies. 300 μl of the Syk-cSH2 (WT or mutants) solution (0–250 μM) was added to a series of 1.5 ml microcentrifuge containing the peptide solution (2.5 μM). After 10-min incubation in the dark, the mixture was transferred to a quartz cuvette with 2-mm path length and fluorescence anisotropy (r) was measured with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 485 and 535 nm, respectively using Horiba Flurolog-3 spectrofluorometer. Since Po >> Pepo under our conditions, the Kd for the Syk-cSH2-peptide binding was determined by the non-linear least-squares analysis of the binding isotherm using the equation:

where Pepbound, Pepo, and Po indicate the concentration of bound peptide, total peptide and total Syk-cSH2, respectively, and Δr and Δrmax are the anisotropy change for each Po and the maximal Δr, respectively.

Cell Culture

DT40 cell WT and DT40-Syk−/− cells were puchased from Riken, Japan. Both cell types were maintained in the Gibco RPMI 1640 medium (ThermoFisher), supplimented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma), 1% chicken serum (Sigma), 50 μM β-mercaptathenol (ThermoFisher) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFisher). Jurkat cells were maintained in the RPMI 1640 medium supplimented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 mM HEPES, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. MV4-11 AML cells were maintained in the Gibco IMDM nedium (ThermoFisher), supplimented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. HL-60 AML cells were maintained in IMDM supplimented with 20% heat-inactivated FBS.

Cell transfection

DT40-Syk−/− cells were maintained at a cell density of 5.0 × 106 cells/ml before transfection. Cells harvested by centrifugation were resuspended in 100 μl Nucleofector T-Kit containing 3 μg of EGFP-Syk WT (or K220/K222A) and 2 μg of mCherry-mCherry-eMyoX-tPH in a microcentrifuge tube. The mixture was then transferred to the cuvette provided with the kit and cells were electroporated by placing the cuvette in the nucleofector 2b platform (Lonza) and selecting the program B-009. Immediately after the electroporation, 500 μl of the growth media was added and the mixture was transferred in 100 mm plate. MV4-11 cells were transfected with different shRNA’s (300 pmol) for Syk knockdown using the Nucleofector L–kit and program Q-023. After 72 h of transfection, the cells were activated using IgG2 (Sigma-Aldrich) to stimulate the human Fc-γ receptor I and harvested for western blot analysis.

Subcellular localization analysis

DT40-Syk−/− cells transfected with EGFP-Syk WT (or K220/K222A) and mCherry-mCherry-eMyoX-tPH were imaged under 100× magnification with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope using the NIS element software. For IgM stimulation, cells were dropped on the IgM-coated surface (10 ng/ml) covered with the imaging buffer (HBSS pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% FBS) and incubated for 10 min before imaging. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (γ) was calculated using Coloc 2, which is a Fiji’s plugin for colocalization analysis. The PM was selected as the region of interest for calculation of the coefficient. Averages ± s.d.’s of γ values were calculated from triplicate determinations.

Cellular calcium assay

Ca2+ flux in DT40 cells was measured under 40× magnification with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope and accompanying NIS element software. Briefly, cells were loaded with 5 μM Fura-2 AM (ThermoFisher) in the presence of 5 μM Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich) in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS: ThermoFisher) for 45 min at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with HBSS and kept for an additional 30 min at room temperature before the Ca2+ measurement. Cells were dropped on the IgM-coated surface (10 ng/ml) covered with the imaging buffer (HBSS pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% FBS), and the ratiometric images (F340/F380: ratio of fluorescence emission intensity at 340/380 nm) were acquired every 30 msec for 10 min. All quantifications were performed using the Fiji software.

Co-immunoprecipitation

MV-4–11 cells were collected by centrifugation, washed twice with phosphate phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in the immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.25 mM GTP) with 0.2–0.5% Triton X-100 and a protease inhibitor mix (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were prepared after 5 min of incubation on ice by repeated pipetting and centrifugation for 10 min at 12,000 g and at 4°C. For immunoprecipitation, the SYK-specific antibody was immobilized onto 100 μl Dynabeads/protein A (ThermoFisher) and the excess antibody was washed away by placing the tube in a DynaMag magnet and removing the supernatant. The resuspended beads were then incubated with the cell extract supernatant containing 500 μg of proteins for 1 h at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were rinsed three times with the IP buffer and eluted with 30 μl of the sample buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). For detection of proteins in total extracts (i.e., Input), 30 μg of the sample was loaded in each gel lane for western blot analysis.

Streptavidin Pull down assay

Streptavidin-coated beads (Dynabeads TM M280 streptavidin beads; ThermoFisher) were washed twice with 1 ml of PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20) and resuspended in 100 μl of PBST. WC36B (or biotin) (10 mM) was added to 100 μl of the bead suspension and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min with gentle shaking. The mixture was then vortexed for 5 s and the tube was placed on a magnet for 1 min. After discarding the supernatant, the beads were resuspended in the same volume of the washing buffer. Washing is repeated three times to remove excess WC36B. WC36B-coated beads were then incubated with the cell lysate (MV-4-11) for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking. Protein-coated beads were separated with a magnet for 2–3 min and washed 4–5 times with PBS containing 0.1% BSA. The protein was then removed from the beads by boiling the beads in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) application buffer. Samples were concentrated for the mass spectrometry analysis and the western blot assay.

Western blot Analysis

Cells were seeded at a density of 3.0 × 105 cells/well prior to incubation with inhibitors. Cells were incubated with 1–5 μM of Syk inhibitors overnight and stimulated with different antibodies: IgG2 for AML cells, IgM for Raji B cells, and OKT3 (Biolegend) for Jurkat cells. The cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 10% glycerol, 10 mM NaF,10 mM Na3VO4, and the protease inhibitor cocktail) at 4°C and the cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were separated and transferred to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore Sigma). The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4°C with various antibodies (1:1000 dilution for all antibodies). After the unbound antibodies were removed by washing with 0.1% Tris buffer saline with 0.1% Tween20, the membranes were incubated with the horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (1:5000 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed three more times with 0.1% Tris buffer saline with 0.1% Tween20 to remove the unbound horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody before imaging. The chemiluminescence intensity of protein bands in the gel was analyzed and documented by the Azure 500Q Imaging System. Quantified data were shown in terms of average ± s.d. P values were calculated by the Student t tests.

Generation of entospletinib (or WC36)-resistant cells

MV4-11 cells were treated with entospletinib (or WC36) to induce drug-resistance cells as reported previously24. MV4-11 cells were incubated first with 500 nM entospletinib (or WC36) for the first week, then the drug concentration was increased 0.5 μM per week until it reached 5 μM (i.e., 10 weeks). Then the concentration was maintained at 5 μM. When the cells remained >90% viable in the presence of 5 μM (i.e., 10 × IC50) entospletinib, they were considered entospletinib-resistant.

Cell proliferation assay

MV4-11 or HL-60 cells were seeded into a clear-bottom 96-well plate containing varying concentrations of inhibitors in the optimal growth media described above and the mixtures were incubated for 16 h. Cells were then treated with a mixture of XTT-labeling reagents and the electron coupling reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche). After 4 h, the absorbance values at 475 nm and at 660 nm were simultaneously measured by Synergy™ Neo spectrofluorometer at 25 °C. Cells with the growth media was used for background correction.

Isolation and treatment of patient-derived AML cells.

Primary samples were obtained from an existing HEMBANK at UIC under an IRB approved research protocol (protocol #2021–0723). Cells were processed and treated with inhibitors as reported previously 48. For primary AML samples, mononuclear cells isolated by Ficoll density centrifugation were utilized. mononuclear cells were treated in culture at a density of 0.5 × 106/ml in StemSpan with CD34 expansion supplement (Stemcell Technologies) for 24 h and then harvested for immunoblotting assays. In parallel 2 × 104 cells were plated in triplicate for each treatment condition in Methoccult H4434 (Stem Cell Technologies) in the presence of drug. At days 12–14, colonies were manually enumerated under light microscopy and normalized to DMSO control for each individual sample due to interpatient variability in colony forming activity. Normalized colony forming units for pooled treated and untreated samples (n = 4) were compared using unpaired 2-tailed Student t test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Cell viability assay

All cell viability assays were conducted in a white, flat-bottom, 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning). The Raji cells were seeded at a density of 3.0 × 105 cells/well 24 h prior to the incubation with the inhibitor. Varying concentrations of WC36 (or DMSO) was then added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C and at 5% CO2 for 72 h. Cell viability was quantified with the CellTiter-Glo reagent. Growth media were removed by aspiration and replaced with 100 μl fresh media and 100 μl CellTiter-Glo reagent. The plates were then gently shaken for 2 min and incubated at 25 C° for additional 8 min. The luminescence was measured using Synergy™ Neo spectrofluorometer at 25 C°. The luminescence value at each WC36 concentration was normalized against that without WC36. DMSO with the same volume as the WC36 solution was used as negative controls.

Molecular dynamics simulation system setup

The simulation system for each SH2 domain (Syk-cSH2, BLNK-SH2, and PLCγ2-cSH2) was constructed using the NMR structure of Syk-cSH2 (PDB: 1CSY), the NMR structure of BLNK-SH2 (PDB: 2EO6), and a homology model of PLCγ2-cSH2 built using the crystal structure of C-terminal SH2 domain of PLCγ1 (PDB: 4EY0) as the template, respectively. The homology modeling was carried out using Prime in the Schrödinger Suite (release 2019–4). PSFGEN plugin of VMD (Visual Molecular Dynamics) was employed to add a C-terminal carboxylate capping group, an N-terminal ammonium capping group, and hydrogen atoms.

For ensemble docking of compounds, each SH2 domain was solvated in a TIP3P water box with a 20 Å padding and neutralized with 150 mM NaCl. To capture the membrane association phenomenon of SH2 domains, we performed membrane-binding simulations by employing a highly mobile membrane mimetic (HMMM) model described as below.

All the independent HMMM membranes were constructed using HMMM BUILDER in CHARMM-GUI. Due to the presence of short-tailed lipids and organic solvent, DCLE, which mimics the hydrophobic core of the membrane, HMMM models significantly enhance lipid diffusion and membrane reorganization thereby allowing spontaneous insertion of peripheral protein. This approach has been extensively used to study variety of peripheral and integral membrane proteins With the aid of this accelerated membrane model, we were able to perform multiple membrane-binding simulations of each SH2 domain in the presence of mixed lipid membrane containing 1,2-dihexanoyl derivatives of PC, PS, and PIP3 in the ratio of 74:20:6. Considering the possible protonation states of PIP3, three variants of PIP3 headgroup were employed in the simulations. Out of six PIP3 in each leaflet, two PIP3 molecules were protonated at P3 position, two at P4 position, and the other two at P5. The entire membrane/protein system was solvated with TIP3P water and buffered in 150 mM NaCl to keep the system neutral.

All the membrane-binding simulations started by placing each SH2 domain in the aqueous solution at least 10 Å away from the membrane. To ensure the final membrane-bound conformation of the protein is not biased due to its initial placement, we generated different initial configurations by varying the orientation of each SH2 domain with respect to the membrane normal (Z axis).

Molecular dynamics simulation Protocols

All molecular dynamics simulations were performed in NAMD2 employing CHARMM36m protein and lipid force fields and TIP3P water. Non-bonded interactions were calculated with 12 Å cutoff and a switching distance of 10 Å. Long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method. The temperature was maintained at 310 K by Langevin dynamics with a damping coefficient of 1.0 ps-1. For the ensemble docking systems, NPT ensemble was used with the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston method. In HMMM simulations, short tailed HMMM lipid membranes were simulated with a constant x-y area corresponding to a 10% increase in the average area per lipid to enhance lipid lateral diffusion and protein insertion to the membrane. The pressure was therefore maintained at 1 atm only along the membrane normal (NPAT) using the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston method. All the simulations were performed with a 2 fs timestep.

All constructed systems were first energy minimized for 10,000 steps by employing steepest descent algorithm. For the systems prepared for ensemble docking, each SH2 domain was equilibrated for 300 ns. For all membrane systems, the energy minimized system was then simulated for 10 ns with harmonic restraints (k = 0.5 kcal mol−1 Å−2) on Cα atoms of the protein, followed by a restraint-free production run of 100 ns. To prevent the escape of the short-tail lipids into the aqueous phase, a harmonic restraint with a force constant of k = 0.05 kcal mol−1 Å−2 was applied to the phospholipid tail atoms C21 C31, along the Z axis of the simulation box. To prevent the diffusion of the DCLE molecules out of the membrane core, we subjected them to a grid-based restraining potential, applied using the gridForce 49 module of NAMD 50.

Ensemble docking

To identify a potential drug binding site in each SH2 domain, the Schrödinger Suite (release 2019–4) was used for docking each compound to an ensemble of the SH2 structures extracted from the equilibrium MD simulation. Each inhibitor molecule was first prepared and generated using the LigPrep with OPLS3e forcefield 51. We extracted protein snapshots for every ns from the 300-ns equilibrated simulation to account for protein structural dynamics, totaling 300 protein snapshots. The grid files for each protein snapshot were generated using the cross docking XGlide script (xglide.py) in the Schrödinger Suite, by which Protein Preparation Wizard 52 was first called to prepare and refine all protein structures, SiteMap 53 was then performed to identify potential ligand binding sites and set up the grid center accordingly, and the OPLS3e forcefield was used to generate the docking search grid. To dock each inhibitor to the grid files for each potential binding site, the Virtual Screening Workflow (VSW) in Maestro was used for carrying out Glide 54 extra precision docking runs with post-docking minimization. For each binding site, up to five poses were generated and the best scoring one was kept for each ligand state.

Analysis of Syk-cSH2-PIP3 interactions

All the analysis was performed in VMD using in-house tcl scripts. The localization of Syk-cSH2 on the membrane surface, more-specifically its interaction with PIP3 was gauged by monitoring the ensemble-averaged Z positions of all the residues (heavy atoms) with respect to the P4 plane, over the last 50 ns of HMMM membrane binding simulations. This analysis allowed us to understand which region of the SH2 domain comes close to the membrane and interacts with PIP3. The total number of PIP3 molecules that interact with the protein was monitored by counting any PIP3 that localizes within 5 Å of the protein during the MD trajectories. As these coarse metrics may not provide sufficient details on the nature of protein–lipid interactions and the information of the binding site, we also quantified specific interactions between lipid headgroups and the SH2 domain. Based on our previous experience 55, a 3.5 Å heavy-atom cutoff was chosen to define lipid–protein contacts. We have calculated specific contacts between the protein and the phosphate groups at position 3, 4, and 5 of the inositol ring.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

MS analysis was performed to identify proteins captured by WC36B and biotin. Briefly, the eluant containing proteins from each capture were diluted to a final concentration of 5% SDS, reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol at 55°C for 15 min, alkylated with 30 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature for 20 min in the dark and enzymatically digested via trypsin at 37°C overnight using the S-Trap protocol. Peptides from each capture were subsequently eluted, dried in vacuo and resuspended in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. Peptide separation and mass detection occurred using an Agilent 1260 liquid chromatography (LC) system and Thermo Q-Exactive mass spectrometer. Raw data for the LC-MS analysis was searched against the Swiss Protein Homosapien database using the Proteome Discoverer (v2.3, Thermo Fisher, Carlsbad, CA) software. Here, trypsin was set as the protease with two missed cleavages and searches were performed with precursor and fragment mass error tolerances set to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. Peptide variable modifications allowed during the search were oxidation (M), whereas carbamidomethyl (C) and was set as a fixed modification.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was calculated by the unpaired Student’s t-test. The number of independent experiments, the number of total cells analyzed, and p values are reported in the figure legends. Sample sizes for cellular imaging and assays were chosen as the minimum number of independent observations required for statistically significant results.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. PIP3-dependent membrane binding of Syk-cSH2.

a. A representative simulation box for the HMMM membrane binding simulations of Syk-cSH2, which is initially placed at least 10 Å away from the membrane surface. 1,2-dihexanoyl derivatives of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylserine (PS) are shown in gray and purple lines, respectively, and PIP3 (6 in each leaflet) in space-filling representation (carbon, oxygen, and phosphorous atoms in yellow, red and tan, respectively). The hydrophobic core of the membrane is filled with an organic solvent (DCLE), shown in transparent surface representation. Bulk water molecules and ions are not shown for clarity. b. Ensemble-averaged residue profile of the Syk-cSH2, calculated during last the 50 ns of HMMM simulations. The gray bars denote the standard deviation in the residue distances. The pY-interacting residue (R195) is highlighted in black star. The representative PIP3-interacting conformations captured at the end of membrane binding simulations are shown at the bottom panel. c. Probability histogram of the number of PIP3 within 5 Å of Syk-cSH2, calculated over last 50 ns of all the HMMM membrane binding simulations, highlights that the protein can simultaneously interact with multiple PIP3 interacting which might help in its effective recruitment. d. Histograms of the protein residues in contact (within 3.5 Å) with the 3’, 4’ and 5’ phosphate moieties (P3 (red), P4 (green), and P5 (blue)) of the PIP3 headgroup are calculated over last 50 ns of all the HMMM membrane binding simulations. Notice that K220 and K222 make contact primarily with P3 whereas H163 and K165 interact with both P3 and P4. Many other residues primarily interact with P5. e. All the residues that form contacts with PIP3 for more than 10% of the time are highlighted and those that make the closest contact with PIP3 are labeled. All the basic residues are colored in blue and polar residues in green. f. Enlarged view of interaction between K172 of the Syk-cSH2 domain and the P4 and P5 moieties of PIP3. g. A schematic representation of predicted hydrogen bonds in this binding mode. H-bonds are shown as arrows. Notice that K172 interacts with both P4 and P5, but not with P3. It is thus expected to be involved in non-specific interaction with non-3’ P-containing PtdInsPs, such as PI(4,5)P2. h. Determination of Kd for binding of Syk-cSH2 WT (blue) and mutants (K220A/K222A (red), K172A (green), and R195A (orange) to 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC)/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS)/PIP3 (77:20:3) large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs). The protein concentration was varied from 0 to 500 nM. Each data is average ± SD from 3 independent measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Role of Syk-cSH2-PIP3 binding in plasma membrane translocation of Syk.

a. Subcellular localization of EGFP-Syk-WT and a PIP3 sensor, mCherry-eMyoX-tPH co-expressed in Syk-null DT40 cells after IgM stimulation. b. Subcellular localization of EGFP-Syk-WT and mCherry-eMyoX-tPH expressed in Syk-null DT40 cells before IgM stimulation. c. The effect of depleting cellular PIP3 on IgM-stimulated membrane translocation of EGFP-Syk-WT and mCherry-eMyoX-tPH was measured by treating cells with a Class I PI3K inhibitor, GDC-0941 (10 nM, overnight). d. Subcellular localization of EGFP-Syk-K220A/K222A and mCherry-eMyoX-tPH expressed in Syk-null DT40 cells after IgM stimulation. IgM stimulation was performed by dropping cells on the IgM-coated surface (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. r values indicate Pearson’s correlation coefficients (average ± SD from 3 independent measurements). r was not determined (ND) for Extended Data Fig. 2c because localization of neither EGFP-Syk-WT nor mCherry-eMyoX-tPH was observed in the plasma membrane. Scale bars indicate 2.5 μm. e. IgM-stimulated (10 ng/ml for 10 min) Ca2+ release in Syk-null DT40 cells (black line) stably transfected with Syk-WT (blue line) and Syk-K220A/K222A (red line). Ca2+ levels were ratiometrically (F340/F380: the ratio of fluorescence emission intensity at 380 nm to that at 340 nm) estimated using Fura-2. Each data is a representative curve of 3 independent measurements. Inset: expression levels of transfected Syk-WT and K220A/K222A were comparable as seen in the similar density of immunoblot bands. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a gel loading control. The image is representative of 3 independent measurements.

Extended Data Fig. 3. PIP3-dependent membrane binding of BLNK-SH2.

a. A representative simulation box for the HMMM membrane binding simulations of BLNK-SH2, which is initially placed at least 10 Å away from the membrane surface. See Extended Data Fig. 1 for details. b. A predicted mode of binding of BLNK-SH2 to a PIP3 molecule in the membrane. Left panel: a PIP3 molecule (C and O, N atoms are shown in yellow, red and blue, respectively) and BLNK-SH2 residues (C and O, N atoms are shown in white, red and blue, respectively) interacting with it are shown in stick presentation and labeled. Gray circles indicate PC and PS molecules. This representative structure is one of multiple low energy conformations obtained from the simulation and docking and not all of residues predicted for PIP3 binding are shown. Right panel: the structure is rotated 90° for the top of the protein surface to face the membrane. The protein is shown in surface representation to better illustrate the shape of the primary lipid binging site. c. Superimposition of PIP3 and VG594 docked into the primary lipid binding groove of BLNK-SH2 in the membrane environment. In its lowest energy binding mode, VG594 binds deeper to the groove than the PIP3 headgroup, leading to tight binding and effective inhibition of PIP3 binding. d. Determination of Kd for binding of BLNK-SH2 WT (circles) and K411A/K412A/K413A (triangles) to POPC/POPS/PIP3 (77:20:3) LUVs. The protein concentration was varied from 0 to 500 nM. Each data is average ± SD from 3 independent measurements. e. Selectivity of BLNK-SH2 WT (red) and K411A/K412A/K413A (blue) for POPC/POPS/ PIP3 (77:20:3) (solid lines) over POPC/POPS/PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2) (77:20:3) (broken lines) vesicles determined by SPR analysis. The protein concentration was 100 nM.

Extended Data Fig. 4. PIP3-dependent membrane binding of PLCγ2-cSH2.

a. A representative simulation box for the HMMM membrane binding simulations of PLCγ2-cSH2, which is initially placed at least 10 Å away from the membrane surface. See Extended Data Fig. 1 for details. b. A predicted mode of binding of PLCγ2-cSH2 to a PIP3 molecule in the membrane. Left panel: a PLCγ2-cSH2 residues (C and O, N atoms are shown in white, red and blue, respectively) interacting with a PIP3 molecule (C and O, N atoms are shown in yellow, red and blue, respectively) are shown in stick presentation and labeled. Gray circles indicate PC and PS molecules. This representative structure is one of multiple low energy conformations obtained from the simulation and docking and not all of residues predicted for PIP3 binding are shown. Right panel: the structure is rotated 90° for the top of the protein surface to face the membrane. The protein is shown in surface representation to better illustrate the shape of the primary lipid binging site. c. Superimposition of PIP3 and VG370 docked into the primary lipid binding groove of PLCγ2-cSH2 in the membrane environment. In its lowest energy binding mode, VG370 binds deeper to the groove than the PIP3 headgroup, leading to tight binding and effective inhibition of PIP3 binding. d. Determination of Kd for binding of PLCγ2-cSH2 WT (circles) and K727A/K728A (triangles) to POPC/POPS/PIP3 (77:20:3) LUVs. The protein concentration was varied from 0 to 500 nM. Each data is average ± SD from 3 independent measurements. (e) Selectivity of PLCγ2-cSH2 WT (red) and K727A/K728A (blue) for POPC/POPS/PIP3 (77:20:3) (solid lines) over POPC/POPS/PI(4,5)P2 (PIP2) (77:20:3) (broken lines) vesicles determined by SPR analysis. The protein concentration was 100 nM.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Efficacy and specificity of Syk inhibitors.