Abstract

The symptoms of major-depressive-disorder include psychic pain and anhedonia, i.e. seeing the world through an “aversive lens”. The neurobiology underlying this shift in worldview is emerging. Here these data are reviewed, focusing on how activation of subgenual cingulate (BA25) induces an “aversive lens”, and how higher prefrontal cortical (PFC) areas (BA46/10/32) provide top-down regulation of BA25 but are weakened by excessive dopamine and norepinephrine release during stress exposure, and dendritic spine loss with chronic stress exposure. These changes may generate an attractor state, which maintains the brain under the control of BA25, requiring medication or neuromodulatory treatments to return connectivity to a more flexible state. In line with this hypothesis, effective anti-depressant treatments reduce the activity of BA25 and restore top-down regulation by higher circuits, e.g. as seen with SSRI medications, ketamine, deep brain stimulation of BA25, or rTMS to strengthen dorsolateral PFC. This research has special relevance in an era of chronic stress caused by the COVID19 pandemic, political unrest and threat of climate change.

Keywords: anhedonia, BA25, depression, dopamine, ketamine, major depressive disorder, norepinephrine, prefrontal cortex, primate, rTMS, serotonin, SSRIs, stress, threat, working memory

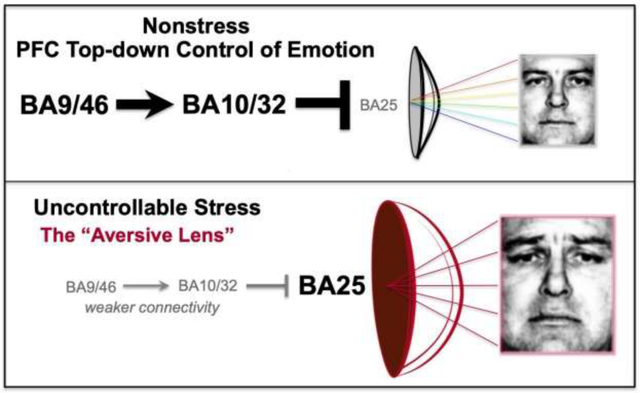

Graphical Abstract

Graphical illustration of how overactivity of BA25 alters brain state to create an “Aversive Lens”, e.g. where a neutral face is seen as sad. A. Under nonstressful conditions, higher PFC areas (BA46, BA10, BA32) provide top-down control of BA25, allowing accurate assessments of the world. B. Exposure to uncontrollable stress weakens the function of higher PFC areas, decreasing top-down regulation of BA25, creating an “Aversive Lens”, e.g. with heightened response to threat and anhedonia (see text). Faces are from (Ekman and Friesen, 1976).

1. Introduction

Our experience of ourselves, and the world around us, can be altered by changes in our brains caused by exposure to uncontrollable stress. Under healthy conditions we are able to process events with appropriate “top-down” regulation and optimism governed by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Wu et al., 2015). However, with exposure to uncontrollable stress, the orchestration of brain circuit connections shifts such that we can lose perspective and experience our universe through an “Aversive Lens” (see Graphical Abstract), (Disner et al., 2011). This can be seen most clearly in patients with major depressive disorder, who focus on negative events, even experiencing a neutral stimulus as sad (Cheeta et al., 2021; Gur et al., 1992), and who lose pleasure in rewarding events, a condition known as anhedonia (Wang et al., 2021b). Recent research in nonhuman primates has begun to illuminate the neural bases for this phenomenon, where activation of Brodmann Area 25 (BA25), a major output of the PFC to the subcortical structures that mediate emotion, increases responses to threat and induces anhedonia (Alexander et al., 2019a; Alexander et al., 2022). These data are consistent with the over-activation of BA25 in patients with depression, and the relief of symptoms when BA25 activity is normalized (Mayberg et al., 2005; Morris et al., 2020). Research in monkeys has also discovered the PFC circuits that normally provide “top-down” regulation of BA25 (Joyce et al., 2020), and how these circuits are weakened by stress exposure (Arnsten et al., 2021).

The current review brings these three sets of findings together to provide a parsimonious account of how uncontrollable stress can simultaneously weaken PFC top-down control while strengthening the amygdala, to maintain the brain in an aversive state. The review highlights the importance of these mechanisms to the etiology and treatment of depression, and also to more global changes arising from the prolonged stress of living through current challenges such as a global pandemic, war and the threat of climate change.

2. The primate PFC

Overview

The primate PFC is a large, complex area of brain where there are major differences between species, and multiple terminologies to describe subregions within the PFC. As this continues to be a source of confusion in the field, we begin this section with a summary of the terms used in this review. This is particularly important for the circuits that regulate and/or generate emotion, where the common use of general terms such as “ventromedial PFC”, has been used to signify widely different subregions (Roberts and Clarke, 2019). Indeed, there are frequent arguments about what cortex even qualifies as PFC, as there are gradients of cytoarchitectonic elaboration within the frontal lobe with few simple boundaries. Thus it is important to define terms to ensure clear communication. For the purposes of this review, we use the term PFC to refer collectively to all regions of polymodal association cortex in the primate that lie rostral to the premotor cortices of the frontal lobes, including not only the granular regions (those regions with a defined granular layer IV) but also the dysgranular and agranular regions on the orbital and medial surfaces, the latter extending into the anterior cingulate cortex. Whilst the term PFC was traditionally used in primates to refer selectively to regions innervated by the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (for discussion, see (Preuss, 1995)), or exclusively granular regions of PFC (Brodmann, 1909), it has been re-defined on a number of occasions since and is more often used now to refer to this extended region (Preuss and Wise, 2022). However, we will primarily refer to specific regions within this area based on their cytoarchitectural characterization as outlined in Figure 1 e.g. areas 46 and 32, which are relatively comparable across monkeys, apes and humans. We will refer to areas 24, 25 and 32 as cingulate cortex, though there is significant individual variability in human BA32 classification and we refer the reader to (Vogt et al., 2013) for more detailed description. Many in vivo studies rely on regional descriptors, e.g. anterior cingulate, but these can often include multiple areas with heterogeneous connections and functions. When possible, we will also try to describe the subregion or subarea more precisely, e.g. BA24 perigenual, subgenual or dorsal to the genu of the corpus callosum. We will use perigenual cingulate to refer to the area 24 and 32 cortices directly anterior to the genu of the corpus callosum, and subgenual cingulate to refer to all the cingulate cortices below the genu. It is hoped that the field in general will understand the importance of more specific terminology given the complexity of these important circuits, and that these terms will be better clarified as subregional functions are discovered.

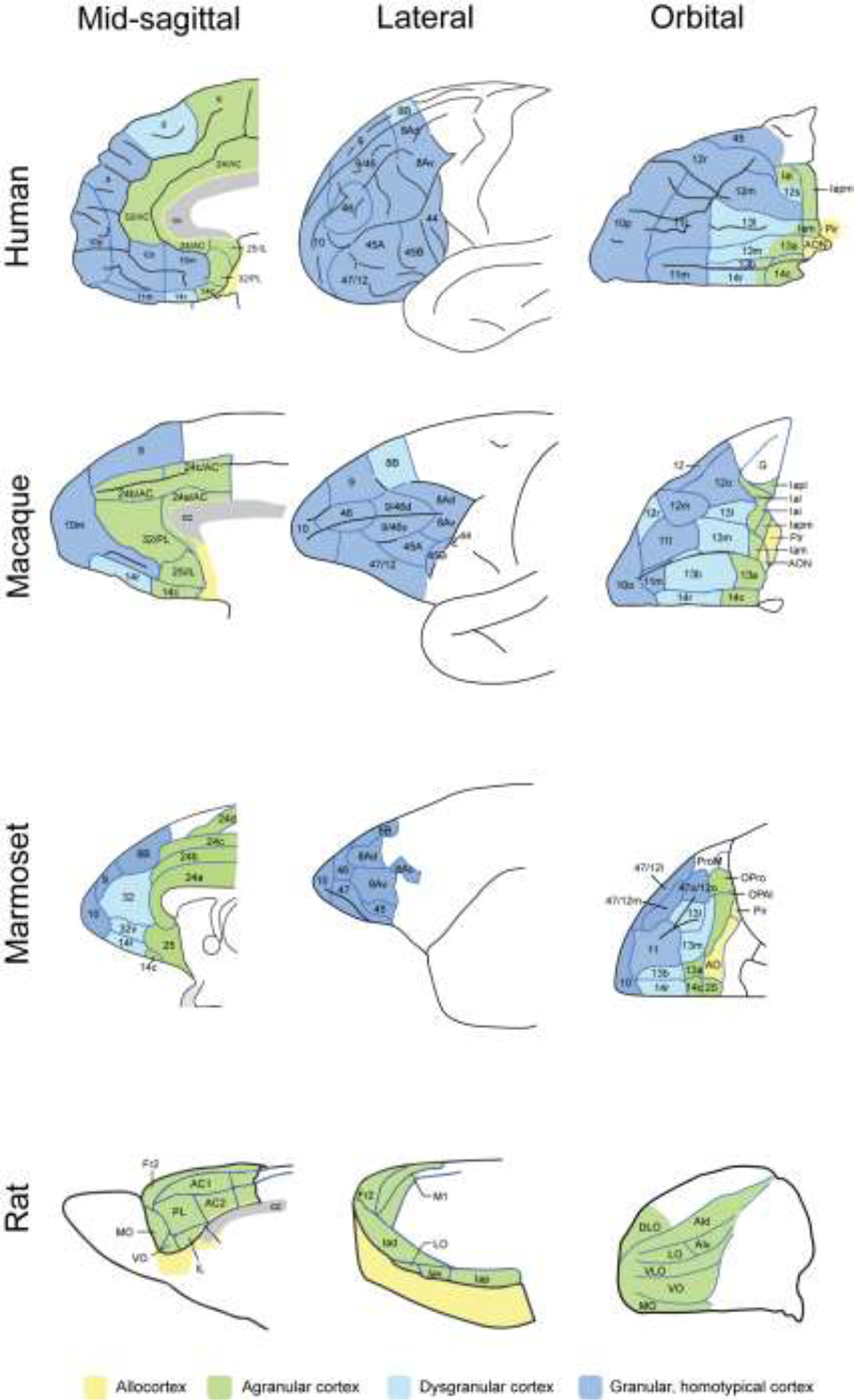

Figure 1-.

The PFC expands greatly from rodents to primates, including expansions from New World monkeys (marmosets) to Old World monkeys (macaques) to humans. The numbering of areas can be particularly confusing, especially in the more caudal PFC areas that include the cingulate cortices. Figure redrawn with permission from (Roberts, 2020).

The PFC expands greatly in primates, and provides “top-down” control of emotion (Roberts, 2020), e.g. based on goals and insights, through connections to the cingulate cortices, which are the major outputs of the frontal lobe to the circuits that generate emotion (Joyce et al., 2020). In particular, the subgenual cingulate (i.e. BA25) can influence many of the subcortical structures that generate emotion, such as the amygdala (emotional associations), the nucleus accumbens (emotional actions and habits, reward encoding, incentive motivation), the hypothalamus (emotional drives), and the brainstem (arousal/stress and autonomic responses). These cingulate pathways are key components of the brain circuits mediating the emotional aspects of pain (Kragel et al., 2018; Opler et al., 2016). As described below, connections from higher levels of the PFC can regulate the activity of BA25, either to activate these pathways (e.g. this restaurant may look safe and welcoming, but given these unmasked diners, it is likely full of a potentially deadly virus), or to inhibit them (e.g. don’t be discouraged, we can make it through this trying time). Thus, healthy, neurotypical functioning requires competing functions to be balanced so behavior and emotion can flexibly adapt as events unfold. Top-down regulation by the PFC provides perspective, insight and optimism, helping us persevere through challenges (Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2009; Dolcos et al., 2016; Hecht, 2013; Hilgenstock et al., 2014; Kuzmanovic et al., 2018; Sharot et al., 2007; Szczepanski and Knight, 2014; Wise, 2008; Wu et al., 2015). In contrast, in mood disorders, activity in emotion-related structures encoding negative affect can become elevated outside appropriate contextual situations, producing symptoms such as overgeneralized anxiety, anhedonia (Alexander et al., 2019a; Alexander et al., 2022), and even psychomotor paralysis (see Section 5 below). Indeed, overactivation of the brain circuits that mediate the emotional aspects of pain can produce a mental anguish that is all-encompassing, disconnecting individuals from their lives and loved ones (Opler et al., 2016). The following sections will discuss the topographic organization of the primate PFC, and how axonal connections between cognition and emotion-related areas in PFC can regulate the activity of BA25 to influence the subcortical brain structures that generate emotion. Understanding these connections helps to explain the mechanisms underlying some of the new treatments for depression, as described at the end of this article.

PFC functions

PFC circuits have the remarkable ability to represent information in the absence of sensory stimulation, and to dynamically alter neuronal firing patterns based on changing rules or goals (Goldman-Rakic, 1996). There is a general, topographic organization whereby the dorsal and lateral PFC (dlPFC) receives sensory inputs about the external world (i.e. visual and auditory inputs), while the ventral and medial PFC receives information about our internal world (somatosensory, olfactory/taste, pain) (Goldman-Rakic, 1987; Ongür and Price, 2000), creating a topography of circuits mediating cognitive to emotional control (Dias et al., 1996). In addition to a dorsolateral to ventromedial gradient, there is also a caudal to rostral gradient, where representations become increasingly abstract more rostrally, i.e. creating representations of representations (Badre and D’Esposito, 2007). As illustrated in Figure 1, the PFC has greatly expanded and differentiated over brain evolution, where the dlPFC and frontal pole do not exist in rodents, and expand from New World monkeys (e.g. marmosets) to Old World macaques (e.g. rhesus monkeys) to apes and humans (Roberts, 2020).

In humans, there is also hemispheric specialization of the PFC, with language production situated in the left PFC for many right-handed individuals, while the right PFC is more specialized for behavioral inhibition. Particularly relevant to the current discussion, the left hemisphere appears specialized for optimism (Hecht, 2013) and appetitive motivation (Pizzagalli et al., 2005), and lesions to the left dlPFC often produce symptoms of depression (Robinson and Lipsey, 1985) suggesting that the left dlPFC in humans may be particularly important for inhibiting the outputs of BA25 that activate an aversive state. Conversely, lesions to the right dlPFC produce disinhibition, and deactivation of the right lateral PFC impairs stopping of a behavioral response (Aron et al., 2004; Chambers et al., 2006). The following is a brief summary of the functions of each of these PFC subregions.

The dlPFC areas (BA9, BA46) are associated with cognition and abstract thought (Goldman-Rakic, 1996; Szczepanski and Knight, 2014). As described in more detail below, neurons in dlPFC are known to continue firing after a visual stimulus is removed, a phenomenon thought to be a substrate for working memory and temporary information storage for later use (Goldman-Rakic, 1995). This neurophysiological signature is part of a dynamic and flexible recurrent network associated with top-down regulation of thought, decision-making and ultimately action (Arnsten et al., 2012), including the regulation of emotion through pathways to more medial PFC regions. Human imaging studies show that PFC circuits have flexible connectivity within large-scale cortical networks that contribute to cognitive control and executive functions (Menon and D’Esposito, 2022). As described below, monkey research shows that this property may arise from the unusual molecular regulation of dlPFC dendritic spines that allows for very rapid changes in the strength of synaptic connectivity (termed “Dynamic Network Connectivity”), but also renders these circuits especially vulnerable to stress and inflammation (Arnsten et al., 2012). Lesions to the dlPFC can produce impaired working memory, concrete thinking, deficits in executive function such as planning, attention regulation and rule learning, and poor motivation (Szczepanski and Knight, 2014). Severe working memory deficits can contribute to thought disorder, where patients are even unable to complete sentences, often evident in disorganized speech.

The more rostral frontal pole region (BA10) mediates metacognitive functions, such as “remembering to remember” (metamemory). This region expands in humans compared to nonhuman primates (Koechlin, 2011; Semendeferi et al., 2001; Tsujimoto et al., 2011) (Roberts, 2020), and subserves functions such as insight about oneself and others (introspection and self-judgment), prospection (imagining the future), reality monitoring, and mentalizing (Szczepanski and Knight, 2014; Tsujimoto et al., 2011). Lesions to the frontal pole also often impact the rostral aspect of the orbital (ventral) PFC, which can impair social behavior and social conscience.

The ventral (orbital) and medial PFC areas generate flexible representations of reward and our internal state (Rudebeck et al., 2017), e.g. activating in response to initial ingestion of chocolate, and then deactivating when eating chocolate to the point when it becomes sickening (Small et al., 2001). These circuits interact with the dlPFC to perform flexible, informed decision-making (e.g. (Seo et al., 2014)), allowing us, for example, to choose healthy over unhealthy (but tempting) food options (Hare et al., 2009), and are also critical to appropriate social behavior (Szczepanski and Knight, 2014). The medial PFC expands, differentiates and reorganizes from rodents to primates, with important species differences (Wallis et al., 2017). As described below, BA32, within vmPFC, is a key relay “hub” between high order cognitive and more primitive cingulate circuits (Tang et al., 2019).

3. The cingulate cortices BA24 and BA25 are part of the emotional pain pathway

The more caudal aspects of the medial frontal lobe contain the cingulate cortices, which lie along the corpus callosum. Particularly relevant to the current review, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex which sits above the corpus callosum (containing parts of BA24 and alternatively called anterior mid cingulate cortex (Vogt and Paxinos, 2014)) is the target of the medial pain pathway, which governs the emotional aspects of pain processing (Opler et al., 2016). This pain pathway contains crude information about the site of origin of the painful stimulus, and mediates the suffering aspects of the pain response. It emanates from the medial thalamus and projects to the insular and anterior cingulate cortices, which in turn project to BA25, which then mediates the visceral response to pain (reviewed in (Opler et al., 2016)). For example, the dorsal ACC is overactive under conditions of chronic pain and is a target of surgical removal for the treatment of intractable pain (Viswanathan et al., 2013). The ACC also activates to cognitive errors, e.g. in response to conflicting information in the Stroop interference task (Barch et al., 2001), and responds differentially to environmental uncertainty and volatility (Monosov et al., 2020).

The dorsal ACC is strongly interconnected with the subgenual or subcallosal cingulate cortex, that includes area BA25 and parts of area BA24 and BA32. In humans and macaques non-cingulate regions BA10 and BA14 extend into this subgenual region as well (Fig. 1). BA25, in particular, serves as the major output from the frontal lobe for control of our emotional and visceral state (Joyce et al., 2020; Ongür and Price, 2000), producing somatic and autonomic responses to stress (Alexander et al., 2020). BA25 is associated with both positive and negative emotional states (Myers-Schulz and Koenigs, 2012; Rudebeck et al., 2014). Accordingly, neurons in rostroventral portion of BA25/BA14 are activated by appetitive stimuli, while neurons in the caudodorsal portion of BA25 are activated by aversive stimuli (Monosov and Hikosaka, 2012). As described in detail below, excessive activity of BA25 is associated with anxiety and anhedonia in marmosets, and with symptoms of depression in humans (Alexander et al., 2019a; Alexander et al., 2020; Mayberg et al., 2005). Thus, depression can be viewed as overactivation of the emotional pain pathway in the absence of a physical, painful stimulus (Opler et al., 2016).

Connections

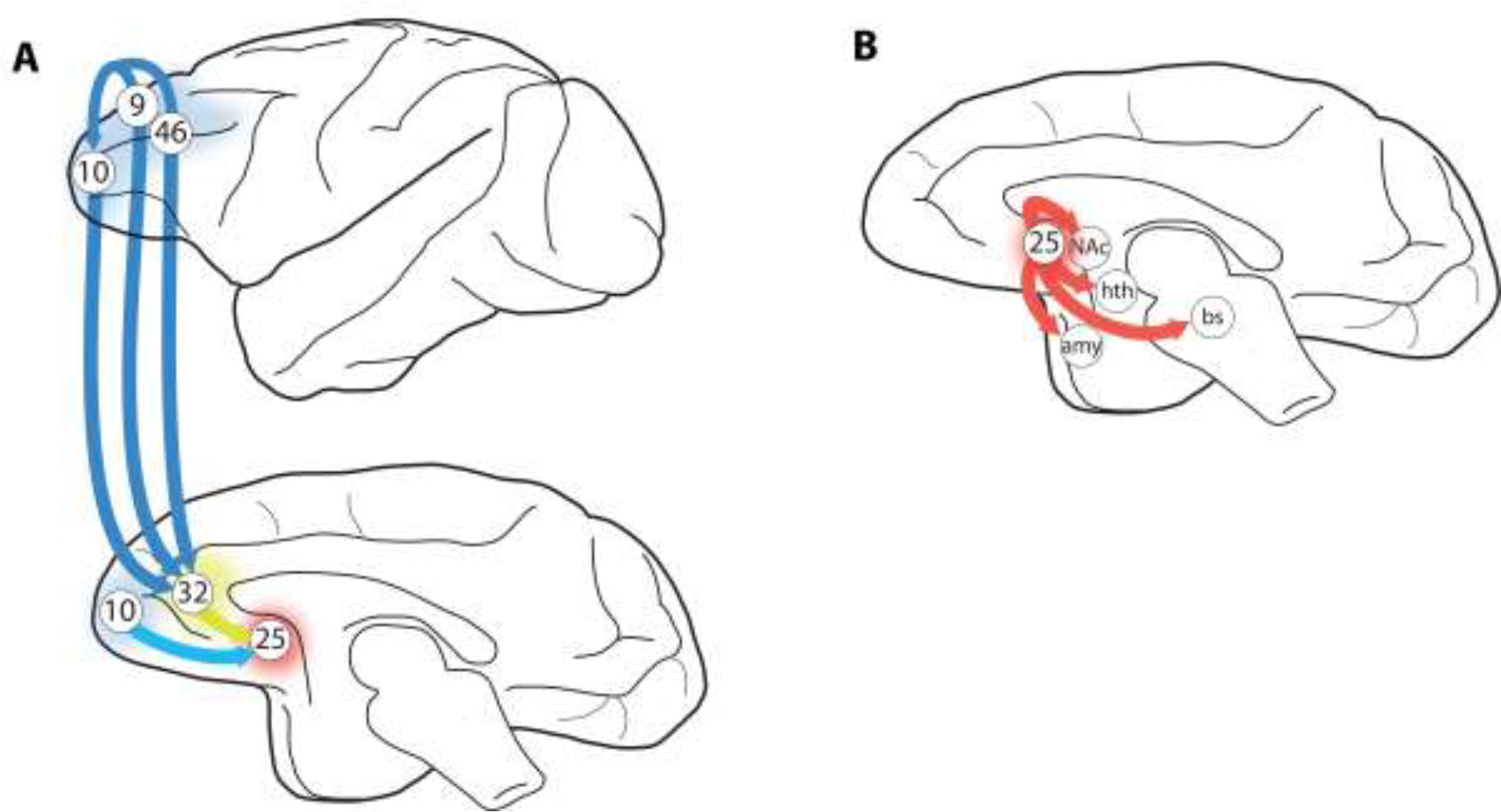

As summarized in Figure 2, anatomical tracing studies in macaques have detailed the connections that mediate emotion generation and regulation. The ACC and particularly BA25 have extensive connections to the subcortical structures that generate and coordinate emotional state. The outputs of these cingulate areas are regulated by connections from more rostral areas of the PFC, where the dlPFC and frontal pole (BA10) connect through the BA32 to influence BA25 outputs (Fig. 2A). There are also direct interconnections between BA10 and BA25, and from the dlPFC to the ACC. The details of BA25 connections, including their laminar origins and targets, are described in this section, while the “top-down” connections that regulate BA25 are described in the following section. Note that, in addition to its many connections to subcortical areas, BA25 also has reciprocal connections back to the cortical areas that project to BA25, including dense projections back to BA32 (Joyce and Barbas, 2018). Thus, BA25 may influence both higher cortical areas, and the subcortical structures that activate the stress response.

Figure 2-.

The pathways from the dlPFC to BA25 to the subcortical areas that generate emotion have been examined in detail in studies of the rhesus macaque. A. The PFC circuits that provide top-down control of BA25. dlPFC BA46 projects to BA10m and BA32; BA10m also projects to BA32, and both BA10m and BA32 project to BA25 to regulate emotion. B. BA25 projects to a large number of subcortical structures that generate our emotional state, including visceral responses such as changes in heart rate. These projections include reciprocal connections with amygdala (amy), and projections to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), hypothalamus (hth) and brainstem (bs). Note that BA25 also projects back to BA32, but this is not shown. Figure based on research from the Barbas lab (Joyce et al., 2020).

Subcortical connections of BA25- BA25 has many subcortical projections important for emotional expression (Fig. 2B). Direct projections to brainstem structures may elicit somatic and visceral responses to stress, including cardiovascular effects (An et al., 1998; Chiba et al., 2001; Freedman et al., 2000). These descending connections likely subserve the role of BA25 in generating negative somatic states as discussed below (Alexander et al., 2019a). BA25 also innervates the hypothalamus, lateral habenula and amygdala, structures also known for effecting negative emotional arousal (Chiba et al., 2001; Freedman et al., 2000; Ghashghaei et al., 2007; Ongür et al., 1998). Finally, BA25 also has dense projections to the nucleus accumbens, a structure necessary for reward and motivated behavior (Chiba et al., 2001; Heilbronner et al., 2016; Heimer and Van Hoesen, 2006).

BA25 has a bidirectional relationship with the amygdala, an integral structure associated with negative emotions (Duvarci and Pare, 2014; Ghashghaei et al., 2007). BA25, (and parts of BA32 and BA24), are known to innervate the basal complex in amygdala (Ghashghaei et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2021), where fear associations are established, with many connections onto excitatory cells (connections onto inhibitory neurons remains an important, open question). BA25 sits at the intersection of the cingulate gyrus and the posterior orbital PFC, systems which each have distinct innervation patterns in the amygdala, with the cingulate targeting the basal complex and the posterior orbital PFC targeting the intercalated masses (Zikopoulos et al., 2017). The intercalated masses are thought to be involved in fear inhibition and extinction, or learning that a previously dangerous association is now safe (Arruda-Carvalho and Clem, 2015). BA25 also receives a dense innervation from the hippocampus (Wang et al., 2021a), that may provide contextual information (Duvarci and Pare, 2014), which may combine with information about internal state to flexibly promote or inhibit the amygdala as appropriate.

The bidirectional connectivity between BA25 and the basal amygdalar complex (Ghashghaei et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2020) may create a positive feedback loop that contributes to their overactivation and the generation of anxious behaviors (Alexander et al., 2019a; Alexander et al., 2020). Indeed, with chronic stress and depression, connections between the dorsomedial BA25 and amygdala may sustain a high level of reverberant activity in both structures, maintaining the brain in an aversive mode. As described below, novel, rapid-acting antidepressants like ketamine may quiet this heightened activity in BA25 and amygdala just enough for dlPFC and/or BA10 to promote emotional regulation through their projections to BA25 (Yang et al., 2021).

4. PFC connections provide top-down control of emotion

The activity of BA25 activity can be regulated by BA32 and higher order PFC connections. BA32 is connectionally suited to balance competing PFC processes like cognition and emotion (Barbas and Pandya, 1989; Joyce et al., 2020). As illustrated in Figure 2A, connections from BA32 to BA25 are strong, and they involve superficial and deep layers at both origin (BA32 layers II-III, V-VI) and termination (BA25 layers I-VI) (Joyce et al., 2020; Joyce and Barbas, 2018). In BA25, BA32 terminations interact with excitatory targets and functionally distinct inhibitory neurons, positioning it to flexibly recruit or dampen BA25 activity if needed (Joyce et al., 2020). Metabolic activity in the ACC region including BA32 predicts effective medication response in depression (Pizzagalli et al., 2001), and a recent study showed alterations in microRNAs in BA32 related to anxiety-associated 5-HTT polymorphism in marmosets (Popa et al., 2022). There are also direct connections from the frontal pole BA10 to BA25 (Fig. 2A) that may regulate BA25 activity (Joyce and Barbas, 2018). We will also see below that BA10 and 32 in the vmPFC are a major focus of gray matter loss with chronic stress exposure, eroding the corridor for top-down control. Thus, understanding the connections of the PFC with BA32 and BA25 has immediate relevance to our understanding and treatment of mood disorders, as does understanding if and how BA25 overactivity can generate an aversive state.

Whilst there is a small, direct projection from the dlPFC to BA25, the most likely pathways by which the dlPFC may be able to influence BA25 are indirect, via its connections to BA10 (Barbas and Pandya, 1989) and to BA32 (Joyce et al., 2020) (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the indirect pathway from dlPFC to BA32 to BA25 arises from superficial layers of dlPFC (Joyce et al., 2020), the laminar compartment where the cognition-associated delay-related firing is known to occur (Goldman-Rakic, 1995). In humans, this indirect pathway from the left dlPFC may be a substrate for therapeutic effects of rTMS in treating depression, restoring regulation of emotion, as discussed below.

5. BA25 activates the “Aversive Lens”-

It is notoriously difficult to image within subgenual cingulate cortex as the nearby air-filled spaces of the frontal sinuses make the signal prone to artifacts that can affect spatial localizability (Du et al., 2007). Thus, it has proven difficult to parcellate out the specific function of BA25 within this heterogeneous region using neuroimaging alone (but see Palomero-Gallagher et al, 2015). Moreover, neuroimaging studies do not provide evidence of causation, making it important to assess the specific functional role of BA25 in a nonhuman primate. Intervention studies in the marmoset show that overactivation of BA25, as reported in depression, produces an overall negative affective state, not only enhancing reactivity to threat but also blunting responsivity to reward. In this section we will consider the evidence for this.

Increased activation within BA25 can be achieved pharmacologically using dihydrokainic acid, a blocker of the glutamate uptake transporter, GLT1. When infused into the brain it increases the overall excitability of the targeted region by prolonging the actions of glutamate release, for approx. 15 minutes. As shown in Figure 3, this alters basal cardiovascular activity, including increases in heart rate, alongside reductions in heart rate variability and a change in sympatho-vagal balance towards the sympathetic system (Alexander et al., 2020); related to increased fight and flight behaviours. Heart rate variability is a measure of the flexibility of the heart rate to changing physiological demands and reductions in heart rate variability reflect reduced flexibility, commonly seen in psychiatric disorders. It should be noted, that, so far, of the many regions within prefrontal and mid cingulate regions investigated, including orbitofrontal areas 11 and 13 (Stawicka et al., 2021), ventromedial area 14 (Stawicka et al., 2020) and rostral and caudal mid-cingulate area 24 (Rahman et al., 2021), only BA25 appears to regulate basal cardiovascular activity. Thus, BA25 appears to have privileged control over the cardiovascular system.

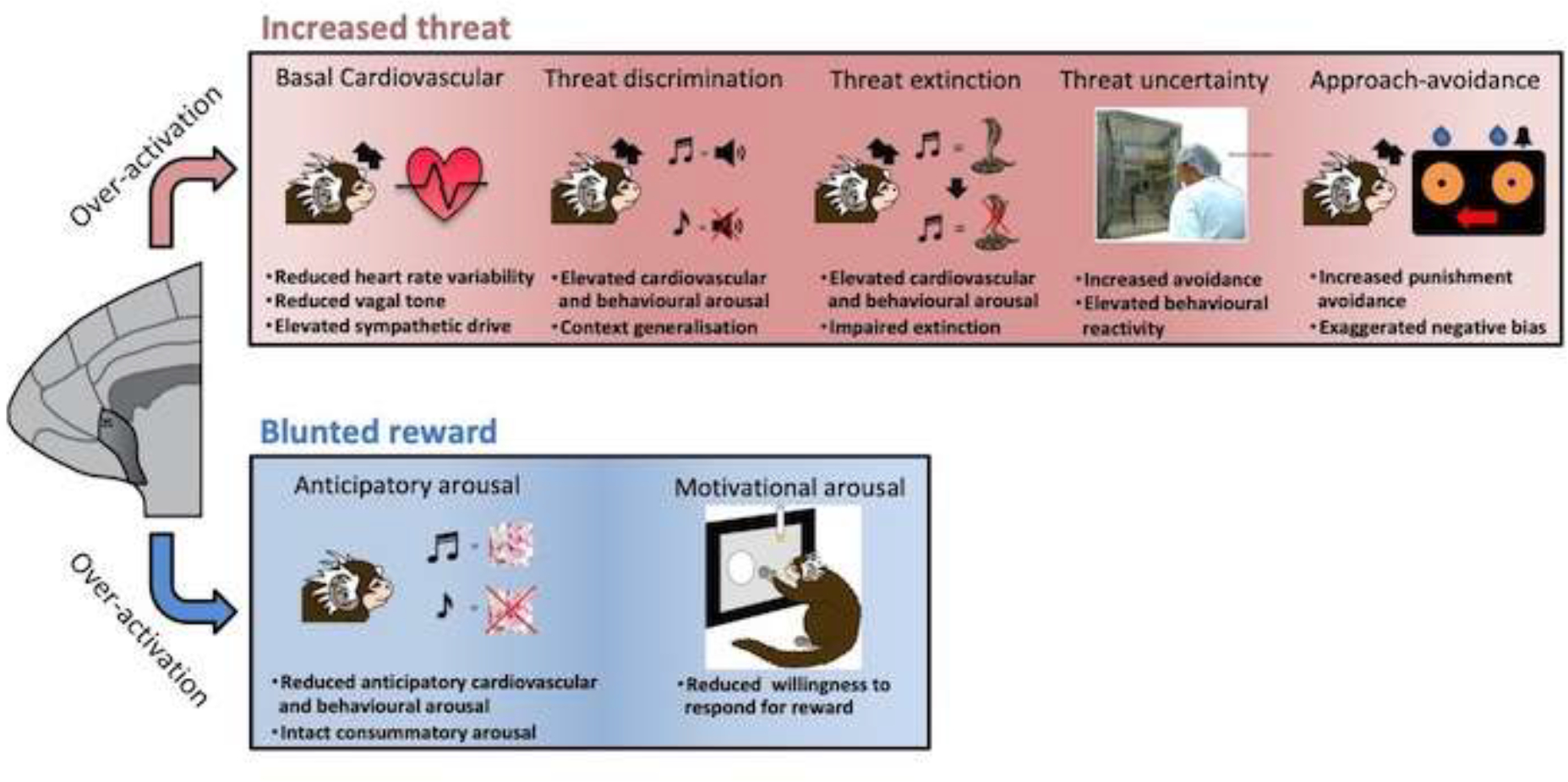

Figure 3-.

Overactivation of BA25enhances basal cardiovascular arousal, increases behavioral and physiological reactivity to environmental threat and blunts reward-induced anticipatory and motivational arousal to reward, consistent with anhedonia.

BA25 over-activation also heightens cardiovascular and behavioral reactivity to acute threat, both certain and uncertain (Fig. 3). In response to certain threat (often considered akin to acute fear), as measured in a Pavlovian discriminative threat paradigm, area 25 overactivation caused generalization of the conditioned threat response such that heightened cardiovascular and behavioral arousal was displayed not only in response to an auditory cue associated with threat (darkness and intermittent white noise) but also to a ‘safety’ cue that signalled that no threat would be presented. It also retarded/blocked the reduction of cardiovascular and behavioural arousal to conditioned threat when the conditioned stimuli were repeatedly presented in the absence of threat (commonly known as extinction). In the latter, this maintained threat response following extinction was accompanied by increased levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Similarly, BA25 overactivation heightens the broad range of threat-related behaviours, including avoidance as well as attentional and alarm vocalisations emitted by marmosets in response to uncertain threat in the form of an unknown human; responsivity to uncertain or more distal threat being likened to anxiety (Alexander et al., 2019b; Alexander et al., 2020).

Consistent with an overall negative emotional state, BA25 overactivation also blunts reward-related arousal (Fig. 3), specifically anticipatory cardiovascular and behavioral arousal to conditioned stimuli associated with food reward (marshmallow), leaving responsiveness to the marshmallow itself, called the unconditioned or consummatory response, relatively intact (Alexander et al., 2019b). It also retards the motivation to gain access to reward as measured by the willingness of marmosets to make more and more responses to gain reward. Such overactivation also disrupts appetitive and aversive decision making where animals adapt their responding for reward either in response to the opportunity to gain more reward or alternatively in response to the occasional concomitant punishment. Here, overactivation reduces their sensitivity to increased reward but heightens their sensitivity to punishment such that they bias their responding away from punishment more so than controls, whilst failing to bias their responding towards increased reward (Wallis et al., 2019). Together these effects of BA25 overactivation to blunt reward processing, induce a negative bias in decision making and enhance threat responsivity, parallel the symptoms of anhedonia, negative bias in decision making and co-morbid anxiety in depression (Pizzagalli and Roberts, 2022), supporting the hypothesis that the heightened overactivity reported in depression may underlie these particular symptoms.

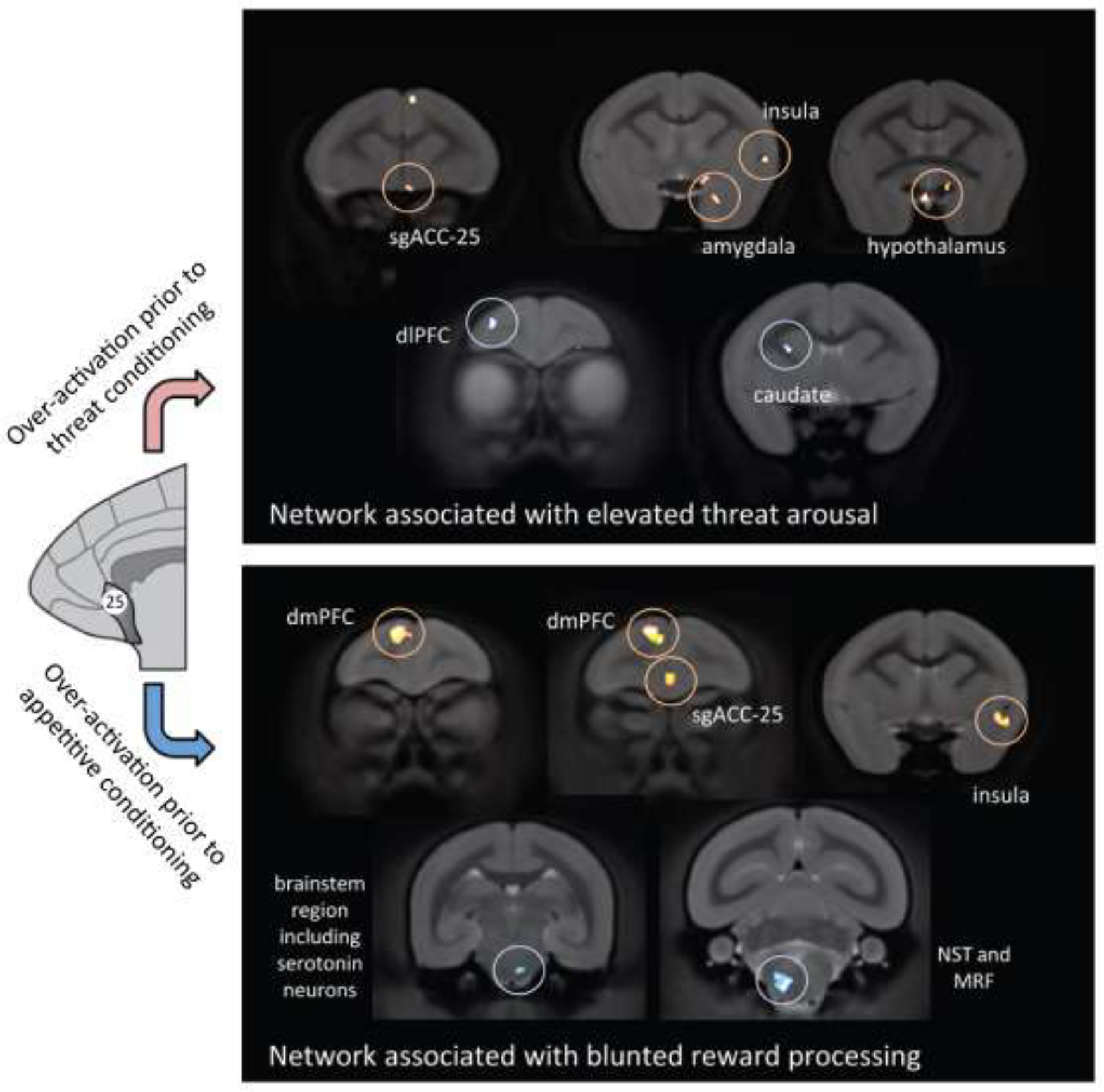

Network analysis suggests that BA25 overactivation engages distinct neural circuits depending on the context, as summarized in Figure 4. In threatening contexts, PET neuroimaging has identified BA25-induced increases in activity in the amygdala, hypothalamus and anterior insula alongside decreases in the dlPFC (consistent with the inverse correlations in activity between these regions reported in human psychiatric neuroimaging studies, see above), OFC and anterior caudate nucleus (Alexander et al., 2020), and consistent with acute stress impairing dlPFC function in macaques, as described below. In contrast, BA25-induced blunting of anticipatory arousal for reward is associated with increases in activation within dorsal anterior cingulate/medial prefrontal regions alongside anterior insula and reductions in the brainstem in the vicinity of the dorsal raphe nucleus (Alexander et al., 2019b). An additional region implicated in the blunting of reward processing in MDD is the nucleus accumbens (Pizzagalli et al., 2009), supported by findings in marmosets using viral-mediated pathway-specific DREADDs whereby the DREADD activator, CNO, blunted anticipatory arousal when targeting the BA25 pathway to the nucleus accumbens but not the amygdala, with the converse being the case for heightening of reactivity to uncertain threat (Wood et al., 2022).

Figure 4-.

Activation of BA25 produces different patterns of brain activity depending on the context. Under conditions of uncertain threat when the subject is presented with novel stimuli it increases the activity of stress-related regions (e.g. amygdala and hypothalamus) but decreases the activity of the dlPFC and the corresponding region in the caudate nucleus. In contrast, activation of BA25 during appetitive conditioning, when the subject is anticipating a reward, blunts the activity of the network associated with reward processing, including reduced activity in the region of the serotonergic raphe nucleus. Based on (Alexander et al., 2020), and (Alexander et al., 2019b). Re-drawn with permission from (Alexander et al, 2022).

It is possible that differential activation of distinct BA25 connections to subcortical structures contributes to the heterogeneity of symptoms seen in depression, e.g. as detected by subtypes of brain connectivity patterns in patients which correlate with symptom clusters (Drysdale et al., 2017). As just described, recent data from marmosets shows that increases in anxiety/threat are mediated by BA25 activation of the amygdala, while an anhedonic profile is generated by BA25 projections to the nucleus accumbens (Wood et al., 2022). It is possible that differential activity of one pathway vs. the other may underlie differences in the degree of anxiety vs. anhedonia in patients. One could speculate that additional efferent projections from BA25 may contribute to other symptom clusters, e.g. with BA25 projections to hypothalamus contributing to altered sleep and appetite, and connections to the periaqueductal gray (An et al., 1998) and/or subthalamic nucleus (Haynes and Haber, 2013) mediating psychomotor paralysis. It should be noted that it is highly likely that there are also additional circuits, independent of BA25, which contribute to depressive symptom heterogeneity.

BA25 activation during depression may also entrain the neural circuits that contribute to the default mode network (DMN), a constellation of areas that are activated together in resting states. The DMN is normally associated with internal states, e.g. daydreaming, (Raichle, 2015), but also with rumination (Berman et al., 2011). Disruption of the DMN occurs in depression, where BA25 becomes coupled to the network (Berman et al., 2011; Broyd et al., 2009; Greicius et al., 2007), a coupling that is associated with duration of current depressive episode (Greicius et al., 2007) and depressive rumination scores (Hamilton et al., 2015). This “capture” of the DMN by BA25 may occur through increased activity in the dense connections from BA25 to BA32 (Joyce and Barbas, 2018) during depression-related BA25 hyperactivity. A recent study also demonstrated strong BA25 connections to the anterior medial thalamus (Joyce et al., 2022), which may be another entrant for BA25 to couple with the DMN, as the anterior thalamus has also been found to couple with the DMN in depression (Greicius et al., 2007).

It can be challenging to test these hypotheses in rodents due to species differences in the PFC and cingulate cortices. In rodents, the structurally analogous structure to BA25 is infralimbic cortex (IL) (Vogt and Paxinos, 2014) but whether it’s functionally analogous is less clear. For example, discrepancies arise between primate and rodent studies with regards reactivity to threat. Activity in rodent IL is implicated in the inhibition of conditioned threat responses during Pavlovian threat extinction (Milad and Quirk, 2012) in marked contrast to the involvement of primate BA25 in the prolongation of conditioned threat responses and in the retardation of extinction (Alexander et al., 2020). This discrepancy may be explained in part by the anatomical finding that the intercalated neurons of the amygdala, shown to be involved in threat inhibition, are innervated by IL in rats but by posterior OFC (Zikopoulos et al., 2017) and more ventral BA25 in monkeys (Joyce et al., under review). On the other hand, similar to primate BA25, rodent IL has been implicated in the blunting of reward processing. Of particular relevance to the current discussion are the findings that IL activation reduces dopamine neuron activity in the ventral tegmental area (Patton et al., 2013) and suppresses striatal responses to dopamine (Ferenczi et al., 2016) whilst IL inactivation restores dopamine activity levels following their reduction in a chronic mild stress model of depression (Moreines et al., 2017). Accumbens and its dopamine innervation have been especially implicated in the anticipation and motivation for rewarding outcomes, and the findings that BA25 overactivation blunts this reward-associated pathway is consistent with the blunting of reward responsivity in depression.

An important question is what activates BA25, leading to heightened reactivity to threat and blunted reward responsivity? Since heightened activity in this region is associated with the stress-related disorder of depression, a likely trigger is stress. Indeed, BA25/24 metabolic activity, as measured with FDG-PET in macaque monkeys, consistently predicts individual differences in the plasma concentration of the stress hormone, cortisol, regardless of the context in which cortisol and brain activity are assessed (Jahn et al., 2010). This relationship may be the result of cortisol activating BA25 through its high density of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors (Patel et al., 2000), although the converse cannot be ruled out, - that BA25 activates cortisol release, either directly, via its projections into the hypothalamus, or indirectly, via its projections to e.g. the amygdala, which result in heightened responsivity to stress. It may also arise from increased catecholamine actions in BA25 during stress, but this is not known. Whilst there have been many studies of rodent prelimbic PFC alterations with stress, there have been far fewer studies focusing specifically on IL (Wellman et al., 2020). In primates, the focus has been on the microcircuitry and neuromodulation of the dlPFC, which will be described in the following sections.

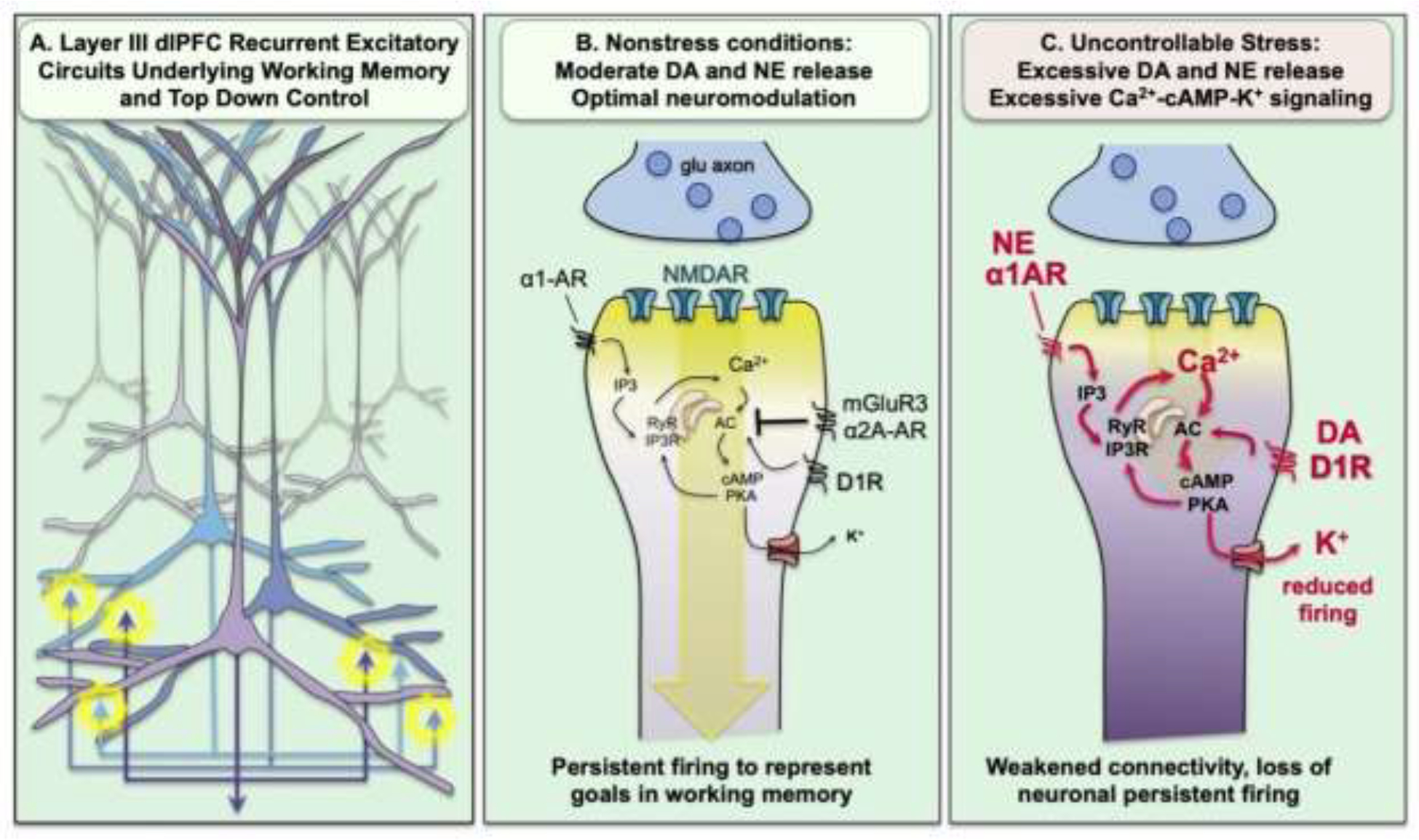

6. The cellular basis for dlPFC top-down control-

The dlPFC generates mental representations needed for top-down control of thought, action and emotion through extensive recurrent excitatory circuits in deep layer III ((Goldman-Rakic, 1995); Fig. 5A). These excitatory circuits rely extensively on NMDAR (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor) neurotransmission, with little dependence on AMPARs (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors), to generate the persistent firing across the delay period in working memory tasks ((Wang et al., 2013); Fig 5B). These circuits also have unusual neuromodulation, with cAMP (adenosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate) magnification of calcium signaling in spines ((Arnsten et al., 2021); Fig. 5B), likely needed to maintain NMDAR neurotransmission across a long delay epoch without sensory stimulation. Calcium-cAMP signaling also opens potassium (K+) channels on spines to provide negative feedback in a recurrent excitatory circuit, and to allow dynamic changes in network connectivity, e.g based on arousal state (Arnsten et al., 2021). Dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE) play a large role in modulating network connectivity, enhancing strong but flexible connectivity under optimal, nonstress conditions, but rapidly disconnecting dlPFC networks under conditions of uncontrollable stress ((Arnsten et al., 2021); Fig. 5C).

Figure 5-.

Recurrent excitatory circuits in the dlPFC generate the persistent neuronal firing needed for top-down control, which is weakened by stress exposure. A. Graphical illustration of the recurrent excitatory circuits in deep layer III of the macaque dlPFC that generate persistent firing. B. Recurrent excitatory synapses on spines depend on NMDAR neurotransmission,with relatively little AMPAR contribution. Under optimal arousal conditions, there is sufficient feedforward, cAMP-calcium signaling to depolarize the synapse and support NMDAR neurotransmission. cAMP-calcium signaling can also open nearby K+ channels to weaken connectivity and allow dynamic changes in network strength. This process is tightly regulated, e.g. by phosphodiesterases (not shown) and by α2A-AR and mGluR3 inhibition of cAMP production. C. Under conditions of uncontrollable stress, there are high levels of catecholamine release in PFC that engage α1-AR and D1R to drive calcium-cAMP opening of K+ channels, weakening synaptic efficacy and reducing the neuronal firing needed for top-down control of emotion.

7. Catecholamines have an inverted-U dose response on dlPFC physiology and function-

NE neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC) and DA neurons in the midbrain project to the dlPFC, and exhibit differing levels of activity based on arousal state, and in response to environmental events. Most research on DA has focused on its role in reward, where DA “Value” cells projecting to the striatum increase their firing to unexpected rewards, or to stimuli that predict rewards, but decrease their firing to the loss of an expected reward (Tobler et al., 2005). The habenula plays a key role in relaying information about aversive events to DA neurons, e.g. inhibiting the firing of DA Value cells (Hikosaka, 2010).

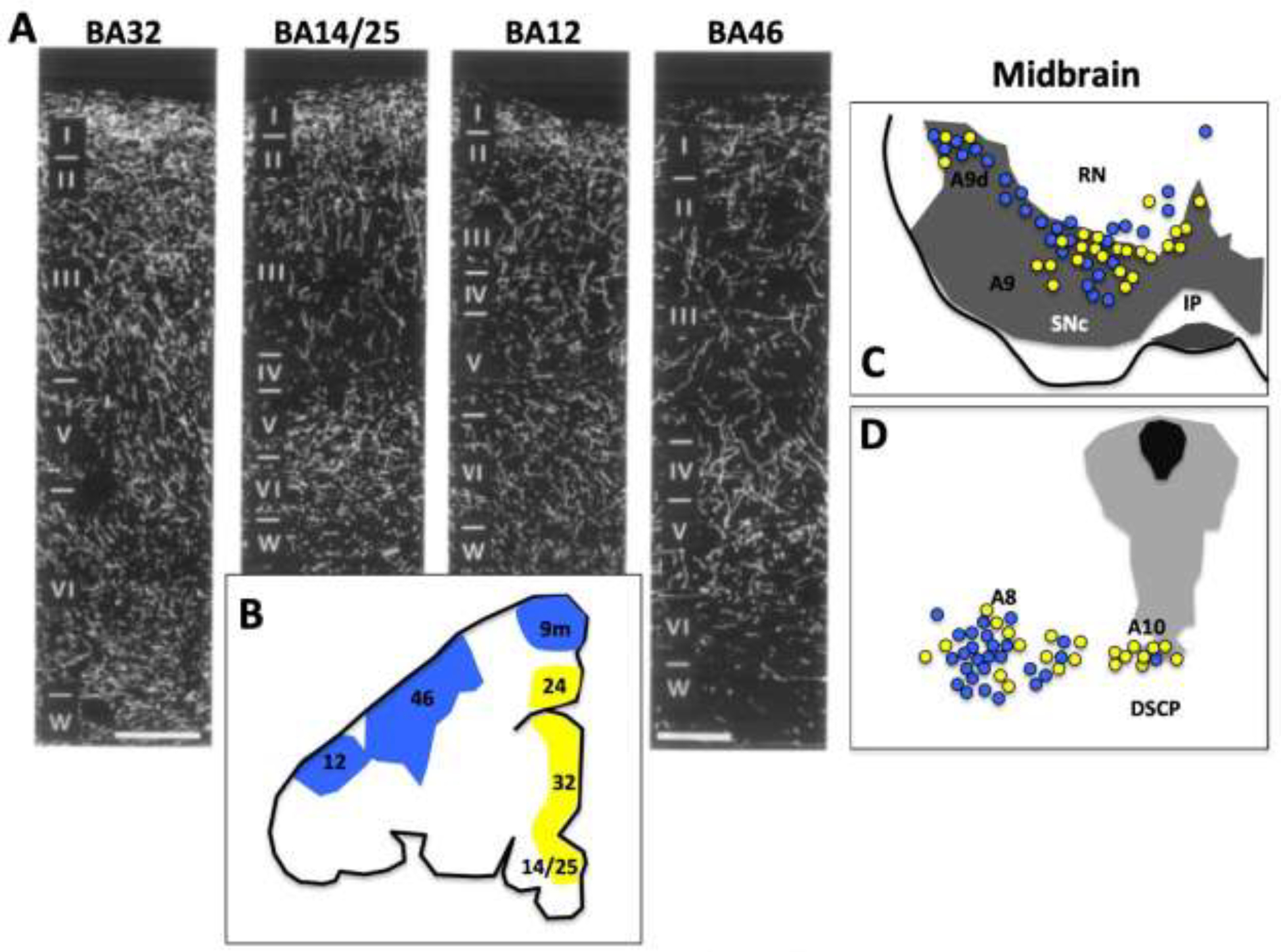

In contrast, the DA cells projecting to the PFC appear to be DA “Salience cells” that fire to both rewarding and aversive events (Bromberg-Martin et al., 2010; Lammel et al., 2011). For example, DA release in the dlPFC increased not only in response to cues predicting reward, but to the unexpected loss of juice (Kodama et al., 2014). The DA projections to the macaque PFC are summarized in Figure 6. While many of the cells arise from the substantia nigra (A9) and ventral tegmental area (A10), many also arise from a more ventral group in A8 that also project to the amygdala (reviewed in (Arnsten et al., 2015)). NE cells in the LC also respond to salient events, with low tonic firing and enhanced stimulus-related firing under conditions of safety, but high tonic firing under conditions of stress (Aston-Jones et al., 2000; Rajkowski et al., 1998). Studies in rodents indicate that there are specific NE neurons that target the mPFC but not more posterior cortical areas (Chandler et al., 2014), indicating an unexpected heterogeneity in LC connectivity. Both DA and NE are needed for PFC function, and moderate levels of catecholamine release under alert, safe conditions enhances dlPFC physiology and function (Chandler et al., 2014), with excitatory effects of mild D1R stimulation (Wang et al., 2019), and NE stimulation of α2A-adrenoceptors on dendritic spines (Wang et al., 2007) (Fig. 5B). These beneficial effects contribute to the therapeutic effects of stimulant and nonstimulant medications for treating PFC disorders such as ADHD (Arnsten, 2020; Gamo et al., 2010).

Figure 6-.

DA Projections to the macaque PFC. A. DA innervation of BA32, BA25, BA12, and BA46 in the rhesus macaque. B. Illustration of locations of PFC subfields, with dlPFC projections shown in blue, and medial PFC projections shown in yellow. C (rostral) and D (caudal) midbrain showing the DA cell groups (A8, 9, 10) sites from which DA neurons project to dlPFC (blue) or mPFC (yellow). Abbreviations: IP interpeduncular nucleus; DSCP decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle; ML medial lemniscus; RN red nucleus; SNc (dark gray shaded area) substantia nigra pars compacta. Adapted from Arnsten et al., 2015.

In contrast, high levels of catecholamine release during stress exposure weaken connectivity and impair PFC function (Fig. 5C). Studies in rodents have documented increased DA and NE release in the mPFC with uncontrollable stress exposure (Finlay et al., 1995), activated by the amygdala in response to a psychological stress (Goldstein et al., 1996), but also found with physiological stressors such as traumatic brain injury (Kobori et al., 2006). Studies in rodents, monkeys and humans indicate that these high levels of catecholamine release during uncontrollable stress play a key role in taking dlPFC and BA10/32 circuits “off-line” during stress exposure (Arnsten, 2015), as described in the following sections.

8. Stress effects on PFC circuits produce an aversive state-

As introduced above, stress exposure is a risk factor for multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression, and is causal for PTSD (Mazure, 1998; Southwick et al., 2005). Thus, understanding how stress impacts the PFC circuits that govern emotion has particular clinical relevance. Besides its possible contribution to BA25 overactivity, evidence from both animals and humans indicate that the PFC is particularly vulnerable to uncontrollable stress, and that acute as well as chronic stress exposure weakens the recently evolved circuits that provide top-down regulation of emotion.

Acute stress exposure

Exposure to an uncontrollable stressor impairs the working memory and executive functions of the PFC in animals and humans (Arnsten, 2009). The controllability of the stressor is a key factor (Arnsten, 2009; Jackson et al., 1980), and data from rodents indicate that the medial PFC can control its own neuromodulatory inputs, inhibiting stress-induced monoamine release when the subjects experiences itself as being in control of the stressor (Amat et al., 2005; Amat et al., 2008; Bland et al., 2003). With uncontrollable stress, there are high levels of catecholamine (Finlay et al., 1995; Murphy et al., 1996) and serotonin (Bland et al., 2003) release in the rodent mPFC. The role(s) of serotonin on PFC functioning during stress are still a mystery, as some studies find mPFC serotonin release protective (Ren et al., 2018) and others detrimental (Amat et al., 2005) to behavioral output. However, these studies used differing behavioral assays, and neither tested working memory, instead testing behaviors that may rely more on subcortical circuits. Viral-genetic manipulations indicate that dorsal raphe neurons that project to the amygdala promote anxiety, while those projecting to medial PFC promote active coping (Ren et al., 2018). Importantly, there is little known about how serotonin alters neuronal function in the PFC through actions on its multiple receptors, an important area for future research.

In contrast, there has been a great deal learned about the roles of catecholamines on PFC cognitive function, with both NE and DA having an inverted-U dose response on working memory function (Arnsten et al., 2021). As illustrated in Figure 5C, exposure to an uncontrollable stressor induces high levels of DA and NE release in the PFC, which drive calcium-cAMP opening of K+ channels to take dlPFC offline, reducing top-down control of emotion (Arnsten, 2009; Arnsten et al., 2021). The detrimental effects of NE occur at low affinity α1-AR, which are only activated when there are high levels of NE release (Arnsten, 2000). Physiological recordings in macaques show that high levels of DA D1R or NE α1-AR stimulation markedly reduce dlPFC persistent firing via opening of K+ channels ((Datta et al., 2019; Gamo et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019); Fig. 5C), while infusions of D1R or α1-AR agonists into dlPFC impair working memory performance (Mao et al., 1999; Vijayraghavan et al., 2017). It is not known if there are parallel effects of catecholamines in BA10 or BA32 mPFC in primates, but infusions of D1R or α1-AR agonists into rat mPFC similarly impair working memory (Arnsten et al., 1999; Zahrt et al., 1997), and may help to orchestrate the response to aversive stimuli (Vander Weele et al., 2019). For example, in mouse, DA increases the firing of brainstem-projecting mPFC neurons to an aversive stimulus, but not to rewarding stimuli (Vander Weele et al., 2018), activating circuits in the periaqueductal gray that coordinate autonomic and behavioral responses to stress (Bandler and Shipley, 1994). Thus, mPFC neurons that orchestrate the stress response in brainstem and amygdala may be activated by high levels of DA (Vander Weele et al., 2019), while PFC neurons that mediate top-down goal-directed behavior are suppressed by high levels of DA D1R stimulation (Arnsten et al., 2015). The impairments in working memory with stress exposure in animals appear to be directly relevant to humans, as dlPFC BOLD activity is reduced by exposure to an uncontrollable stressor in subjects performing a working memory task (Qin et al., 2009), a finding that is related to elevated catecholamines (Qin et al., 2012). Loss of “top-down” control by dlPFC would disinhibit BA25 which in turn can potentiate the amygdala response to threat, and reduce the nucleus accumbens DA response to reward, creating an “aversive lens”, as illustrated in the Graphical Abstract.

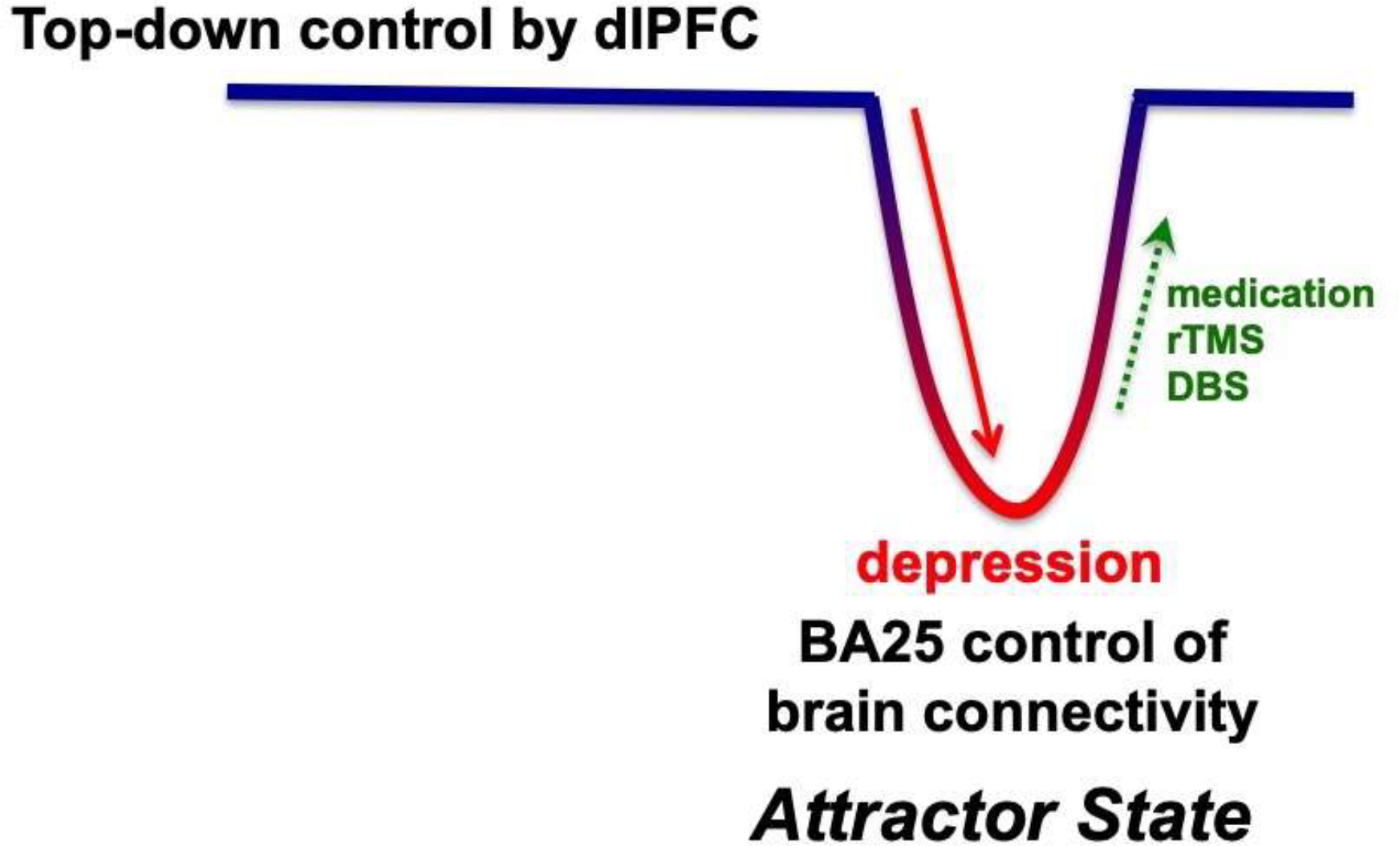

Stress exposure can also activate the amygdala directly. Studies in rodents indicate that there are high levels of catecholamine release in the amygdala during stress that strengthen emotional responding (Cahill and McGaugh, 1996; Yokoyama et al., 2005). NE α1-AR and β-AR stimulation enhances the consolidation of emotional memories through actions in the basolateral amygdala (Cahill and McGaugh, 1996; Ferry et al., 1999; Roozendaal and McGaugh, 2011), and the NE neurons that project to the central nucleus of the amygdala become more excitable with stress, and cause increased anxiety (Borodovitsyna et al., 2020). DA can accentuate fear and anxiety through direct actions in the BLA or central nuclei (de la Mora et al., 2010; Nader and LeDoux, 1999), or through indirect actions, disinhibiting neurons in the central and basolateral complexes by inhibiting the intercalated GABAergic neurons (Aksoy-Aksel et al., 2021; Marowsky et al., 2005), and by diminishing PFC inhibitory actions in the amygdala (Rosenkranz and Grace, 2001). Anatomical studies of the primate amygdala are consistent with these data in rodents, and suggest parallel actions in primate (Zikopoulos et al., 2016). The amygdala in turn can drive catecholamine release in the PFC (Goldstein et al., 1996), thus keeping the dlPFC “offline”. This would create an attractor state (Fig. 7), where the brain would flip from top-down control by higher PFC regions BA9/46, BA10 and BA32, to a more primitive, emotional state controlled by BA25 and its alteration of subcortical limbic structures.

Figure 7-.

A schematic illustration of how BA25 activation may create an “attractor state” that maintains brain connectivity in an aversive state with impaired “top-down” control by higher PFC circuits. This would explain why pharmacological or neuromodulatory treatments are often necessary to return the brain to healthier connectivity, with top-down control by the dlPFC and interconnected vmPFC circuits.

Brain imaging of how the human brain responds to stress is consistent with this model. A study by Sinha and colleagues examined dynamic brain changes in response to an acute stressor using fMRI, and found that BA32 deactivated in the initial response to stress, and then reactivated in correspondence with active coping and functional connectivity with the dlPFC (Sinha et al., 2016). In contrast, increases in cortisol correlated with activation of an area including BA25 (Sinha et al., 2016). Stress has also been shown to reduce functional connectivity between dlPFC and a region overlapping with BA32, and was associated with levels of perceived stress, cortisol release, and impaired self-control (Maier et al., 2015). These imaging data are consistent with a study showing that human subjects with greater working memory capacity are better able to regulate the stress response (Otto et al., 2013). Thus, insults to the dlPFC, BA10, and/or BA32 would reduce resilience.

Chronic stress exposure

With chronic stress exposure, there are additional architectural changes in brain, where PFC pyramidal cells lose spines and dendrites. Most of this work has been performed in rodent models, but the results are consistent with changes seen with human brain imaging. In rats, chronic stress exposure leads to a loss of spines and dendrites from pyramidal cells in layer II/III mPFC that correlates with impaired cognition (Hains et al., 2009; Liston et al., 2006). Loss of spines involves increases in cAMP-PKA (protein kinase A) and calcium-PKC (protein kinase C) signaling (Hains et al., 2009; Hains et al., 2015), where calcium dysregulation initiates inflammatory changes that lead to phagocytosis of spines (Woo et al., 2021). Similar changes appear to occur in PFC with physiological stressors such as hypoxia (Kauser et al., 2013) and traumatic brain injury to the posterior cortex (Kobori et al., 2006; Kobori et al., 2011; Kobori et al., 2015). In contrast to the mPFC, mixed effects (increases and decreases) have been reported in the orbital PFC with psychological stressors (Dias-Ferreira et al., 2009; Gourley et al., 2013; Liston et al., 2006) which may relate to the hyper- and hypo-activations reported in different regions of orbital PFC in humans with depression (Rolls et al., 2020).

The effects of chronic stress exposure on the brain in humans show similar findings. Even a relatively mild chronic stressor reduced functional connectivity with the dlPFC (Liston et al., 2009), and the number of serious adverse life events correlates with the loss of gray matter in BA32 and BA10m (Ansell et al., 2012). As these medial PFC areas are the “corridor” for top-down regulation of BA25, gray matter loss in this region may be particularly harmful to the regulation of emotion and increase risk of mood disorders. Synaptic loss in the dlPFC itself also appears to play a key role, as a recent study shows that symptoms of depression correlate strongly with lower numbers of synapses in the dlPFC (Holmes et al., 2019). The loss of connectivity in higher PFC areas would leave BA25 activation of the “aversive lens” in predominant control of brain state, helping to explain why medication or other treatments that weaken BA25 and/or strengthen PFC top-down mechanisms are necessary to flip the brain back to a more normal balance (Fig. 7).

9. Relevance to treatment-

Understanding the neural circuits that regulate or generate emotion helps to explain the efficacy of medications and procedures currently used to treat depression (Fig. 8). The findings from nonhuman primate studies provide a supportive foundation for those in humans, which initially discovered the importance of overactivity in subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, including BA25 in depression (Drevets et al., 1997; Mayberg et al., 2005), and that all effective treatments for depression –including psychotherapy and even placebo effects- reduce and normalize the activity in and around BA25 (Mayberg et al., 2005). These findings led to the development of deep brain stimulation (DBS) to try to reduce the activity of BA25 in treatment-resistant patients (Mayberg et al., 2005). The following briefly reviews how anti-depressant treatments may impact BA25 and the top-down PFC circuits that regulate emotion. Much of the basic work has been done in rodent models, where chronic stress is used to induce a “depressive response” i.e. a passive rather than active response in a forced swim test, an assay that has been controversial (Commons et al., 2017). Rodent models are also problematic because the medial PFC expands and differentiates in primates in ways that can be challenging for cross-species comparisons (Roberts, 2020; Wallis et al., 2017). However, these studies have been invaluable in beginning to understand the potential neurobiological underpinnings of anti-depressant treatments.

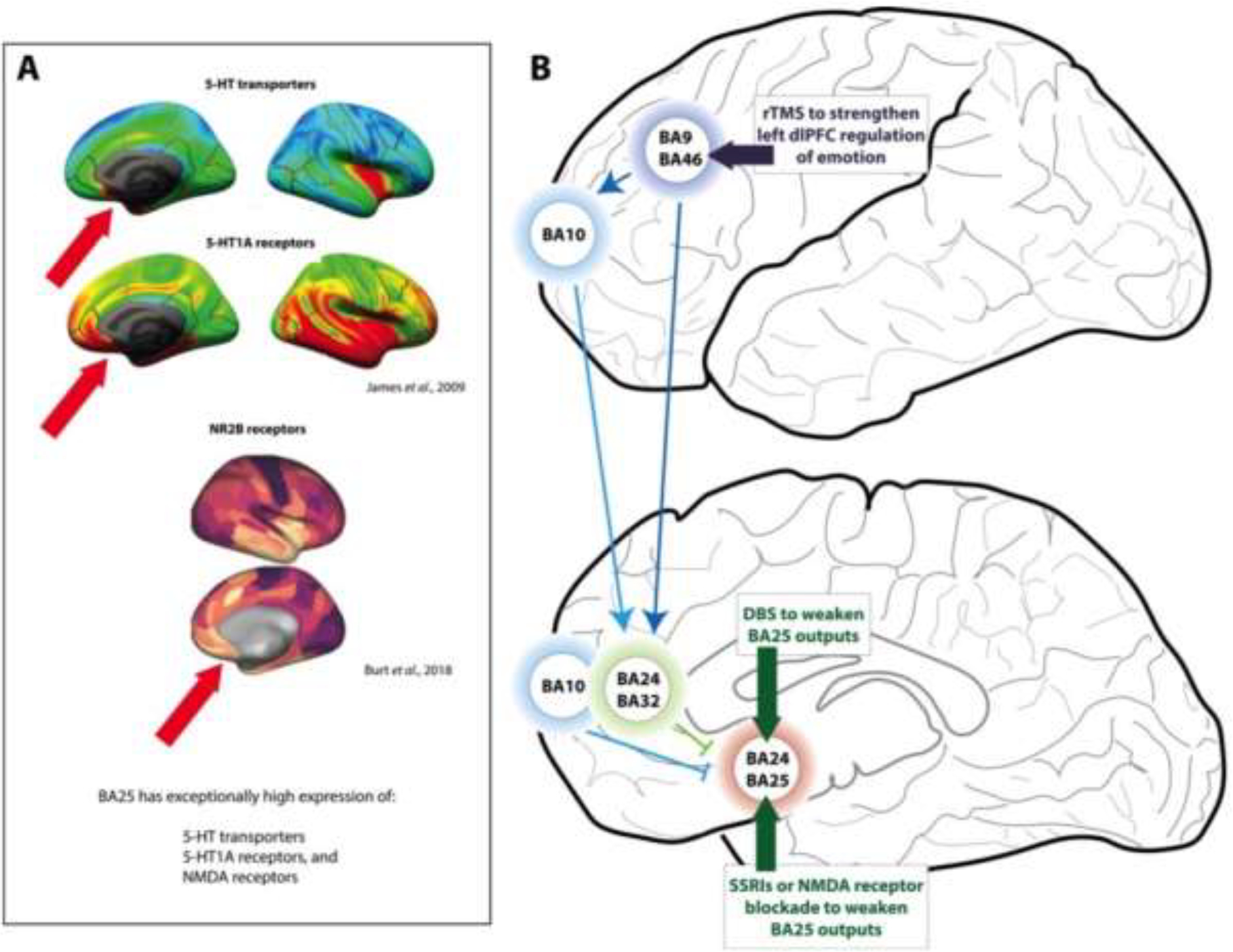

Figure 8-.

Hypotheses regarding how treatments for depression may directly or indirectly reduce the activity of BA25. A. PET neuroreceptor imaging of the healthy human brain shows that BA25 expresses exceptionally high levels of serotonin (5-HT) transporters and 5-HT1A receptors (red arrows), the former being remarkably selective for BA25 within the frontal lobe. Images are from Open Access article (James et al., 2019). BA25 also expresses exceptionally high levels of NMDA receptors (Burt et al., 2018; Palomero-Gallagher et al., 2009); image from Burt et al, 2018. B. Schematic diagram of how treatments for major depressive disorder may normalize the patterns of brain activity, either by directly reducing BA25 activity or by enhancing dlPFC regulation of BA25. The activity of BA25 is reduced with deep brain stimulation (DBS), by increasing serotonin’s inhibitory actions in this region (SSRI’s, psilocybin), or by ketamine blockade of NMDAR. Rapid transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) over the left dlPFC is also an approved treatment for depression, and has been shown to reduce the activity of BA25 e.g. (Cardenas et al., 2021).

Anti-depressant medications

BA25 shows distinctive molecular expression patterns that may help to explain the efficacy of serotonergic and glutamatergic medications in the treatment of depression. As shown in Fig. 8A, BA25 in the human brain is especially enriched in serotonin transporters (James et al., 2019; Varnäs et al., 2004) and 5HT1A receptors (James et al., 2019; Palomero-Gallagher et al., 2009). The elevated level of serotonin transporters in BA25 compared to surrounding areas is particularly striking. BA25 also expresses much higher levels of NMDA receptors Fig. 8A, (Burt et al., 2018; Palomero-Gallagher et al., 2009), which may be relevant to ketamine’s anti-depressant actions. These expression patterns are suggestive of drug actions within BA25, although it is not yet known how medications that act at these sites influence BA25 neuronal activity and function.

SSRIs and psilocybin- It is long-established that serotonin is important for orbital PFC function (Clarke et al., 2007; Roberts, 2011), and many of the compounds used to treat depression impact the serotonergic system. For example, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) that block serotonin transporters, are the most commonly used anti-depressant treatments, with efficacy developing with chronic, but not acute, usage (Gabriel et al., 2020). SSRI efficacy is related to their binding in BA25 (Baldinger et al., 2014), and the striking pattern of expression in serotonin transporters in this region suggests that there may be key serotonin actions in this region that lead to BA25 deactivation when they effectively treat depression (Mayberg et al., 2005). There is speculation that SSRIs may act by increasing serotonin stimulation of 5HT1A receptors, which may hyperpolarize neurons (Béïque et al., 2004) to reduce the activity of BA25 (Ramirez-Mahaluf et al., 2017). However, data from acute infusion studies in marmosets shows that it is 5HT1A receptor blockade rather than stimulation that mimics the reductions in basal and threat-induced cardiovascular activity caused by inactivation of BA25 via GABA agonists (Wallis et al., 2019), indicating that much is still to be learned about neuromodulatory actions, both acute and chronic, in this important brain structure. Serotonin actions in the amygdala may also contribute to the antidepressant effects of SSRIs, as a recent study has also shown that increased serotonin transporter mRNA expression in the right amygdala is associated with high trait anxiety in marmosets, and can be normalized by SSRI infusion (Quah et al., 2020). Thus, the therapeutic effects of SSRIs may be mediated in multiple structures.

There is also renewed interest in 5HT2A receptors given the findings that psilocybin, as well as other 5HT2A agonists, can have rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects (Pearson et al., 2021), including a recent, large Phase 2 study (Goodwin et al., 2022). The mechanisms underlying these anti-depressant effects are not known, including whether these agonists may actually have their beneficial effects through internalization of 5HT2A receptors, e.g. by β-arrestin signaling (Slocum et al., 2021). Thus, learning more about serotonin actions in BA25 will be a critical area for future research. Serotonin also has important actions in the amygdala, e.g. where 5HT1A receptor stimulation reduces, and 5HT2 receptor stimulation increases, the fear response (de Paula and Leite-Panissi, 2016). These data may provide insight as to why atypical antipsychotics, which block 5HT2 receptors, can be an effective augmentation therapy with SSRIs for treatment-resistant depression (Nuñez et al., 2022).

Ketamine- One compelling hypothesis is that BA25 may have excessive glutamate stimulation of NMDAR in patients with depression, and that the NMDAR antagonist, ketamine, may act in part by blocking NMDA receptors in this cortical region. This hypothesis is based on the idea that depression may cause reduced glutamate uptake into astrocytes (Ramirez-Mahaluf et al., 2017), thus elevating glutamate stimulation of NMDA receptors that have particularly high expression in this region (Palomero-Gallagher et al., 2009). The NMDAR antagonist, ketamine, can have rapid anti-depressant actions, reducing symptoms of depression after a single i.v. infusion, with results lasting for multiple days (Berman et al., 2000; Krystal et al., 2013). Recent data with intranasal administration have even shown ultra-rapid anti-depressant effects, e.g. within minutes of administration (Lapidus et al., 2014). As illustrated in Figure 9, we have speculated that the ultra-rapid antidepressant effects of intranasal ketamine may be due to its direct delivery onto BA25 neurons, where NMDAR blockade would reduce the activity of BA25 neurons to produce immediate relief (Opler et al., 2016). In contrast, the more long-lasting anti-depressant effects may evolve from restored spine connections in higher PFC areas (Opler et al., 2016), as discussed below. Ketamine administration also reduces the activity of the habenula (Cui et al., 2019), which may help to ameliorate an aversive brain state, including a reduction in stress-induced DA release.

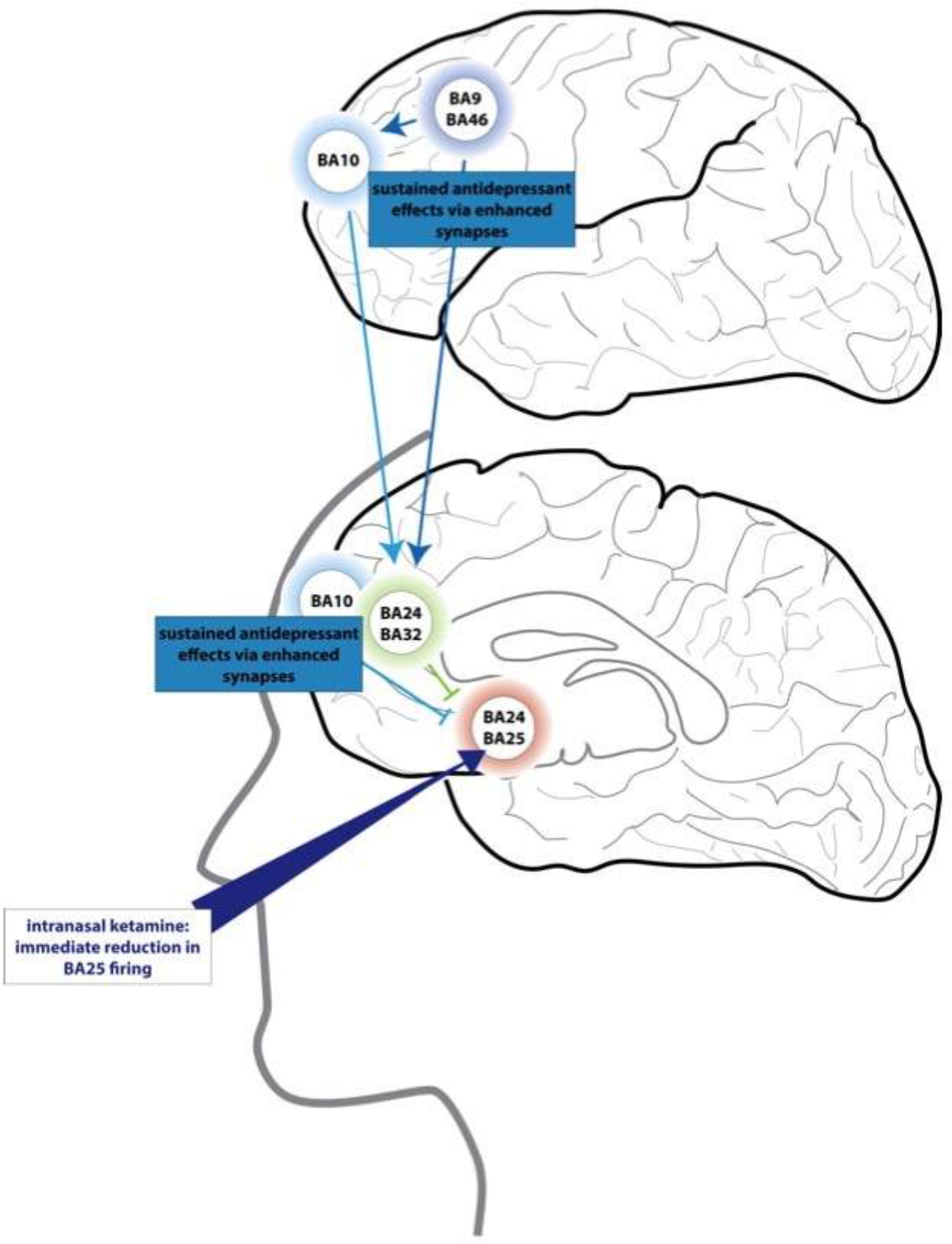

Figure 9 – Hypothesis regarding ketamine’s therapeutic actions in prefrontal circuits.

Intranasal ketamine has an ultra-rapid antidepressant effect within 5–10 minutes (Lapidus et al., 2014). We have proposed that some of these actions may arise from ketamine passing through the cribriform plate directly to BA25, where it could reduce BA25 and provide a “foot-in-the door” for more healthy regulation of brain state (Opler et al., 2016). Repeated treatments may have more sustained antidepressant effects by restoring connectivity in dlPFC, BA10 and BA32, where spines are subject to atrophy from chronic stress.. Based on (Opler et al., 2016).

Importantly, research in rodent models has shown that all of these anti-depressant medications have the shared property of restoring dendritic spines in the mPFC following chronic stress exposure (Duman and Aghajanian, 2012; Hare et al., 2017). Chronic stress induces mPFC spine loss and depressive-like behavior on the forced swim test in rodents (Duman and Aghajanian, 2012; Moda-Sava et al., 2019), and both the behavioral and anatomical effects of chronic stress are reversed by chronic SSRI treatment (Duman and Aghajanian, 2012), acute treatment with ketamine (Duman and Aghajanian, 2012; Moda-Sava et al., 2019), or acute treatment with psilocybin (Shao et al., 2021). Interestingly, direct calcium imaging of spine changes allowed researchers to see that the ultra-rapid anti-depressant effects of ketamine occurred before spine emergence, while the more prolonged anti-depressant effects were related to spine restoration (Moda-Sava et al., 2019). These results from rodents suggest that anti-depressant treatments have long-term efficacy by restoring connectivity in the top-down PFC circuits that regulate BA25. However, the exact circuits affected are not yet known. Intriguingly though, ketamine given 24 hours earlier in marmosets only prevents the effects of BA 25 overactivation to blunt anticipatory arousal to conditioned appetitive stimuli - but not to heighten responsivity to threat-related stimuli (Alexander et al., 2019b; Alexander et al., 2020), consistent with ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy in treatment resistant patients in which anhedonia predominates (Uher et al., 2012), and to ketamine’s blunting of BA25 hyperactivation to positive incentives but not negative incentives in MDD (Morris et al., 2020). This suggests that there are distinct downstream pathways underlying the anxiety- and anhedonia-like symptoms induced by BA25 overactivation which are differentially sensitive to ketamine. Based on the information reviewed above, we would speculate that restoration of spines (and thus connectivity) in BA46, and/or BA10/BA32 would help restore long-term, top-down regulation of emotion. There is some evidence that this occurs in humans, e.g. where ketamine’s antidepressant efficacy is associated with increased functional connectivity between the dlPFC/BA10 and subgenual cortex (Gärtner et al., 2019). Understanding how anti-depressant medications influence the connectivity of identified circuits is an important area for future research.

Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) uses electrical stimulation within the brain to try to decrease the activity of circuits that have become overactive in the diseased or stressed state (Gardner, 2013; Limousin et al., 1997). Mayberg and colleagues developed DBS of BA25 based on the observations that this region is overactive in depression, and that reduced BA25 activity is associated with anti-depressant efficacy (Mayberg, 2009; Mayberg et al., 2005). It is hypothesized that DBS predominately acts by reducing the white matter tract outputs of BA25, which is challenging given the complex wiring in the region of the subgenual cingulate (Riva-Posse et al., 2014). In addition to targeting BA25, DBS is being tested in additional brain structures, e.g. the nucleus accumbens, and a recent meta-analysis of the shared connectomics of these sites suggests that they may share altered activity of BA10 and the amygdala (Zhu et al., 2021), key nodes in the pathways outlined in Figures 2 and 8B. Thus, experimentally-reducing BA25 activity through DBS may provide a “foot-in-the-door” that allows the restoration of top-down control by rostral PFC circuits, allowing the return of regulation of structures such as the amygdala.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is now in clinical use to alter the strength of neural activity, where rapid sequences strengthen, and slow sequences weaken, neural activity. Research has shown that rapid TMS over the left dlPFC (Fig. 8B), or slow TMS over the right dlPFC can lessen symptoms of depression (George et al., 2013). Imaging studies have shown that the efficacy of TMS in treating symptoms of depression is related to its ability to alter the activity and functional connectivity of the circuits described in this review, and the ability of “top-down” PFC areas to regulate BA25 (Cash et al., 2021). For example, rapid TMS over the left dlPFC increases blood flow over this region as measured by SPECT imaging, as well as increasing activity of the vmPFC (Kito et al., 2008). Functional connectivity fMRI measures showed that the rTMS site over dlPFC most clinically effective in reducing depression had the greatest anti-correlated connectivity to BA25 (Fox et al., 2012), consistent with dlPFC top-down regulation of BA25. The efficacy of rTMS to the left dlPFC is most effective in patients with overactivation of BA25 (Baeken et al., 2015), and is related to functional connectivity of BA10 and BA32 with BA25 (Baeken et al., 2014). Conversely, the anti-depressant activity of slow TMS over the right dlPFC correlated with increased activity in BA32 (Kito et al., 2012). In support of these data, rapid TMS over the dorsomedial PFC (dmPFC) improved symptoms of depression in patients whose left dlPFC was strongly connected to the vmPFC, but not in those where the right dlPFC was the more strongly connected to this region (Downar et al., 2014). These nonresponders also had greater symptoms of anhedonia (Downar et al., 2014), consistent with activation of the right dlPFC evoking an “aversive lens”. Research in marmosets also supports a role for the dmPFC in anhedonia, as pharmacological activation of the pathway through BA25 that induces anhedonia increases activity in a caudal portion of dmPFC (Alexander et al., 2019b). However, it is challenging to determine homology between species given the great expansion and differentiation of the dmPFC in humans. Taken together, all of these studies suggest that strengthening left dlPFC or weakening right dlPFC normalizes top-down regulation of emotion in patients with major depressive disorder. Recent developments in this field include personalized focus on strengthening the top-down regulatory pathways described in this review (Cardenas et al., 2021), highlighting how understanding the basic neuroanatomy can have direct therapeutic implications.

10. Relevance to global changes in emotional regulation during stress of the pandemic

Understanding how brain circuits are altered by stress exposure also helps to explain why there have been global changes in human behavior from the stress of the COVID19 pandemic, and the continued threats of climate change. Researchers have documented symptoms consonant with weaker top-down control that have increased over the pandemic including increased depression and anxiety (Hampshire et al., 2022; Hampshire et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021; Vanderlind et al., 2021), increased violence and aggression (Ramzi et al., 2022), and increased substance abuse (Ross et al., 2022). There has also been extensive “burnout” in overworked healthcare workers, a syndrome associated with affective and cognitive changes, including emotional exhaustion, depersonalization or cynicism, diminished feelings of personal efficacy, and increased risk of depression and cardiovascular disease (Arnsten and Shanafelt, 2021). Research on occupational stress (i.e. “burnout”) has shown that overworked subjects had reduced thickness in the right lateral and right ventromedial PFC that correlated with their perceived stress and with their impaired ability to down-modulate negative emotions (Savic et al., 2018). As noted above, chronic stress exposures, unrelated to occupational workload, has also been shown to decrease gray matter in the vmPFC corridor (BA10m, BA32, BA14)(Ansell et al., 2012), the regions that regulate BA25 (Fig. 2), suggesting an anatomical explanation for weaker top-down control under conditions of chronic stress. Interestingly, subjects with lesions to this same vmPFC region (due to stroke, resection or physical trauma) were shown to be more vulnerable to misleading information (Asp et al., 2012), suggesting that chronic stress exposure may make us more susceptible to disinformation, an aggravating factor that has widened social divisions. Thus, widespread erosion in PFC connectivity may lead to an “Aversive Lens” at the societal level. This may worsen outcomes, as top-down control is essential to survival when abstract thinking is needed to understand the presence of danger, e.g. an invisible virus, or the threat of future climate events. Indeed, research has shown that working memory capacity correlated with social distancing capabilities during the Pandemic (Xie et al., 2020), emphasizing the importance of PFC top-down control to a healthy society.

11. Remaining questions:

We have learned a great deal about the neural circuits involved in PFC top-down regulation of emotion and their vulnerability to stress exposure, and are beginning to understand how BA25 can activate visceral, somatic and emotional responses through its connections to subcortical structures. However, we still have insufficient knowledge about the molecular regulation of these circuits needed to develop superior treatments. It is known how global catecholamine or serotonin depletion alters the general functioning of the dlPFC vs. orbital PFC in primates (Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic, 1985; Brozoski et al., 1979; Clarke et al., 2014; Clarke et al., 2005; Clarke et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 1994), and there is accumulating, detailed information on the role of catecholamines and their receptors in primate dlPFC (Arnsten et al., 2021), vlPFC (Puig and Miller, 2012, 2015) and nearby frontal eye fields (Lee et al., 2020; Mueller et al., 2020; Soltani et al., 2013). There is also limited research indicating beneficial effects of 5HT2A receptor activation in lateral PFC (Axelsson et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2002). However, there is almost nothing known about discrete catecholamine or serotonin receptor actions in primate BA10, BA32 or BA25. The sole study of serotonin receptor actions in marmoset BA25 indicates that 5HT1A receptor actions are essential to BA25 function (Wallis et al., 2019), but it is not known if high levels of 5HT1A receptor stimulation would also reduce BA25 activity. And given the intriguing effects of psilocybin, how do 5HT2A receptors influence BA25 functions? Given the importance of these cortical regions to the etiology and treatment of depression, there is great need for this research, but it is challenging to carry out, e.g. given the depth of many structures that are beyond the reach of iontophoretic electrodes, and the complexity of serotonin receptor pharmacology. It will be particularly important to learn how anti-depressant treatments alter the functioning of BA25 and the PFC circuits that provide top-down regulation of emotion. Is the uniquely high expression of serotonin transporters in BA25 key to their being an effective target for anti-depressant medications, and if so, what changes occur in BA25 over time with chronic SSRI treatment, and what receptor(s) mediate these effects? Are there changes in serotonin receptor actions that reduce the overactivity of BA25, and restore emotional balance? How do SSRI actions differ from those of SNRI’s? Is the latter more effective in boosting top-down PFC control?

There has been progress uncovering DA actions in the mouse mPFC, where genetic methods allow manipulation of identified PFC circuits, e.g. from the mPFC to BLA vs. the brainstem (Vander Weele et al., 2019). However, the vast expansion and differentiation of the PFC in primates, including the expansion of the medial PFC, makes it challenging to translate this information across species (Wallis et al., 2017). This can be further complicated by species differences in neuromodulation, e.g. where D1Rs have high expression on interneurons in the mouse cortex but not in macaque or human cortex (Krienen et al., 2020). These details, and whether a pathway targets excitatory vs. inhibitory cells in subcortical targets, will be needed to ultimately learn the functional consequences of activating vs. inhibiting specific circuits in the mPFC. Precise understanding of the circuits regulating and generating emotion, and behavioral assays with immediate relevance to symptoms in humans, will be essential to translating relevance to mood disorders.

12. Summary

We have begun to make progress in learning how BA25 activates and coordinates emotional responses, how more rostral PFC circuits provide top down regulation of BA25, and how weakening of higher circuits with stress exposure can alter brain connectivity in ways that increase risk of depression and seeing the world through an “aversive lens”. Although we need to learn much more about how these circuits are modulated at the molecular level, knowledge of the circuitry has already helped to illuminate the mechanisms underlying rTMS treatment of depression, restoring top-down regulation of emotion.

Highlights.

The brain circuits that generate a depressive state are being illuminated in primates

New data show that activating BA25 can induce anhedonia and increased threat response

This brain state may be maintained when stress weakens prefrontal top-down regulation

These data are particularly timely due to the chronic stress of a global pandemic

Acknowledgements-

This work was funded in part by NIH RO1 MH108643-01 and NSF 2015276 to AFTA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures-

None

Links to relevant websites:

At the Yale Medical School YouTube channel:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aksoy-Aksel A, Gall A, Seewald A, Ferraguti F, Ehrlich I, 2021. Midbrain dopaminergic inputs gate amygdala intercalated cell clusters by distinct and cooperative mechanisms in male mice. Elife 10, e63708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L, Clarke HF, Roberts AC, 2019a. A Focus on the Functions of Area 25 Brain Sci. 9, 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L, Gaskin PLR, Sawiak SJ, Fryer TD, Hong YT, Cockcroft GJ, Clarke HF, Roberts AC, 2019b. Fractionating Blunted Reward Processing Characteristic of Anhedonia by Over-Activating Primate Subgenual Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Neuron 101, 307–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L, Wood CM, Gaskin PLR, Sawiak SJ, Fryer TD, Hong YT, McIver L, Clarke HF, Roberts AC, 2020. Over-activation of primate subgenual cingulate cortex enhances the cardiovascular, behavioral and neural responses to threat. Nat Commun. 11, 5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander L, Wood CM, Roberts AC, 2022. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex and emotion regulation: lost in translation?. J Physiol May 30, Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat J, Baratta MV, Paul E, Bland ST, Watkins LR, Maier SF, 2005. Medial prefrontal cortex determines how stressor controllability affects behavior and dorsal raphe nucleus. Nat Neurosci 8, 365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amat J, Paul E, Watkins LR, Maier SF, 2008. Activation of the ventral medial prefrontal cortex during an uncontrollable stressor reproduces both the immediate and long-term protective effects of behavioral control. Neuroscience 154, 1178–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An X, Bandler R, Ongür D, Price JL, 1998. Prefrontal cortical projections to longitudinal columns in the midbrain periaqueductal gray in macaque monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 401, 455–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Rando K, Tuit K, Guarnaccia J, Sinha R, 2012. Cumulative adversity and smaller gray matter volume in medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insula regions. Biol Psychiatry 72, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, 2015. Stress weakens prefrontal networks: molecular insults to higher cognition. Nat Neurosci. 18, 1376–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, 2000. Through the looking glass: Differential noradrenergic modulation of prefrontal cortical function. Neural Plasticity 7, 133–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, 2009. Stress signaling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 10, 410–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, 2020. Guanfacine’s mechanism of action in treating prefrontal cortical disorders: Successful translation across species. Neurobiol Learning and Memory 176, 107327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, Datta D, Wang M, 2021. The Genie in the Bottle- Magnified calcium signaling in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Molecular Psychiatry 26, 3684–3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, Goldman-Rakic PS, 1985. Alpha-2 adrenergic mechanisms in prefrontal cortex associated with cognitive decline in aged nonhuman primates. Science 230, 1273–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]