Abstract

While initial encoding of contextual memories involves the strengthening of hippocampal circuits, these memories progressively mature to stabilized forms in neocortex and become less hippocampus dependent. Although it has been proposed that long-term storage of contextual memories may involve enduring synaptic changes in neocortical circuits, synaptic substrates of remote contextual memories have been elusive. Here we demonstrate that the consolidation of remote contextual fear memories in mice correlated with progressive strengthening of excitatory connections between prefrontal cortical (PFC) engram neurons active during learning and reactivated during remote memory recall, whereas the extinction of remote memories weakened those synapses. This synapse-specific plasticity was CREB-dependent and required sustained hippocampal signals, which the retrosplenial cortex could convey to PFC. Moreover, PFC engram neurons were strongly connected to other PFC neurons recruited during remote memory recall. Our study suggests that progressive and synapse-specific strengthening of PFC circuits can contribute to long-term storage of contextual memories.

Subject terms: Long-term memory, Neural circuits, Long-term potentiation, Fear conditioning, Consolidation

Lee et al. show that the long-term storage of remote contextual memories involves progressive and synapse-specific strengthening of excitatory connections between memory engram neurons in the prefrontal cortex.

Main

The acquisition of contextual memories requires hippocampal circuits. For instance, encoding of contextual fear memories involves synapse-specific plasticity in hippocampal CA3–CA1 and hippocampal–amygdala circuits1,2. Once acquired, contextual memories gradually mature to stabilized forms in the neocortex during systems-level memory consolidation3–5. The standard consolidation model proposes that the long-term storage of contextual memories may involve enduring synaptic changes in neocortical circuits6,7 such that remote memory recall depends less on the hippocampus8. However, synapse-specific substrates of remote contextual memories have not been identified.

Previous studies suggest that neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) have a pivotal role in the consolidation of remote but not recent contextual memories9–11. These prefrontal cortex (PFC) memory engram neurons are rapidly generated during learning, gradually mature with time and are reactivated during remote memory recall12. Although these studies identified neuronal correlates of remote contextual memories, how PFC engram neurons contribute to remote memory consolidation at the synaptic level remains poorly understood. Connections between PFC engram neurons may be strengthened during memory consolidation, synchronizing the activity of PFC engram neurons and facilitating their reactivation during remote memory recall. However, it remains to be determined whether and how the synaptic strength of neocortical circuits changes during systems consolidation. It is also unknown how PFC engram neurons are connected to other PFC neurons recruited during remote memory recall and those projecting to subcortical engram neurons or how systems consolidation affects these synapses. The transformation theory of systems consolidation proposes that an initially formed memory with contextual details remains dependent on the hippocampus and supports the development of a schematic memory with few contextual details in the neocortex13,14. However, how signals of hippocampal engram are conveyed to PFC for the maturation of neocortical engram remains incompletely understood. In this study, we demonstrated that remote memory consolidation involves progressive and synapse-specific strengthening of excitatory connections between PFC engram neurons, which requires sustained signals of hippocampal engram.

Results

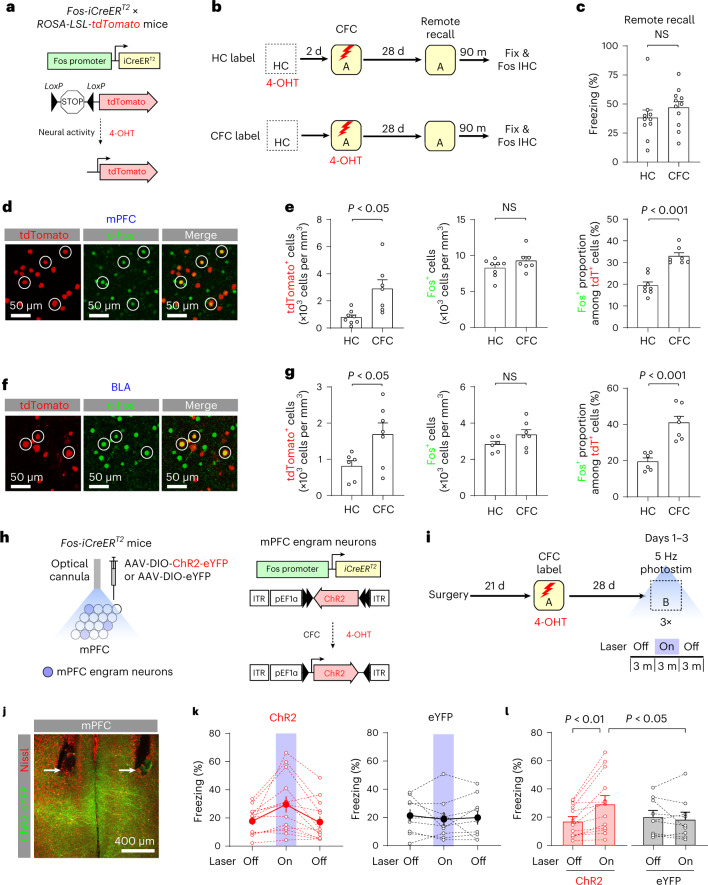

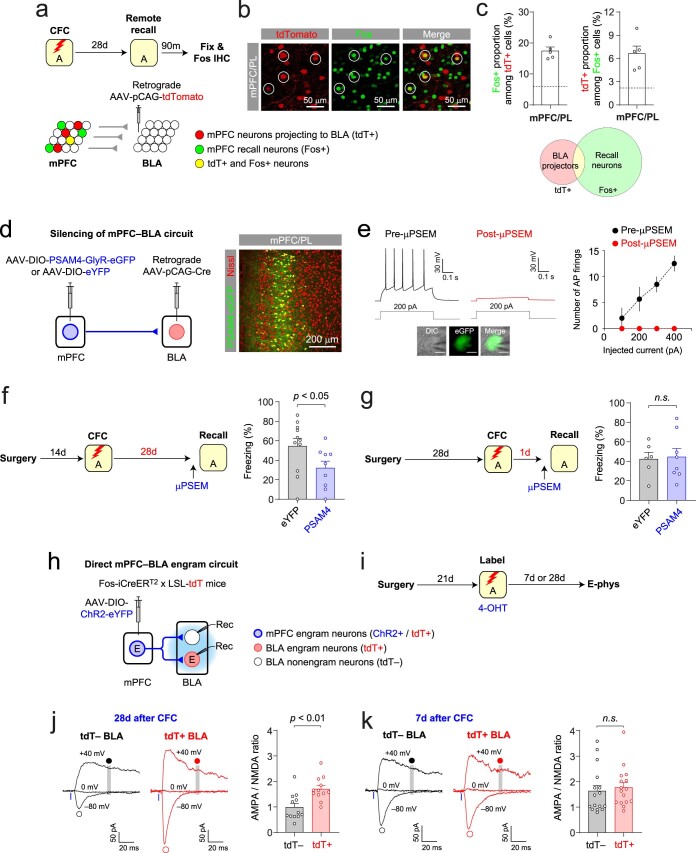

Reactivation of mPFC engram neurons and remote memory recall

We used heterozygous Fos-iCreERT2 knock-in mice15 to label neurons recruited during contextual fear conditioning (CFC), in which the mice learn to associate a neutral context with aversive unconditioned stimuli (US; electric footshock) and display fear to the context. Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice in the CFC group received the US in Context A and received 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) injection (Fig. 1a,b). Neurons active during CFC expressed iCreERT2 under the control of c-Fos promoter, which induced the recombination of LoxP-STOP-LoxP sequence in the presence of 4-OHT, resulting in tdTomato (tdT) expression (Fig. 1a and Extended Data Fig. 1c). In the home cage (HC) group, neurons active in the HC were labeled with tdT and the mice were fear conditioned 2 d later. Four weeks after CFC, the mice displayed robust freezing behavior in Context A (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Neurons active during remote memory recall were immunolabeled for c-Fos. In the prelimbic (PL) division of the mPFC and basolateral amygdala (BLA), both tdT+ cell density and c-Fos+ proportion among all tdT+ neurons were higher in the CFC group than in the HC group, whereas c-Fos+ cell density did not differ between groups (Fig. 1d–g and Supplementary Table 1). These results suggest that CFC recruited mPFC/PL and BLA neurons, which were more likely reactivated during remote memory recall than neurons active in the HC. In the CFC group, tdT expression was highest in mPFC layer 2/3 and detected in 2.8 ± 0.5% of CaMKII+ neurons, while 6.5 ± 1.0% of tdT+ mPFC neurons projected to the BLA (mean ± s.e.m., five mice, Extended Data Fig. 1d–i).

Fig. 1. Activity-dependent labeling identified mPFC engram neurons, whose reactivation resulted in memory recall.

a,b, Experimental setup for c–g. Active neurons expressed tdT in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. Neurons active in the HC were labeled in the HC group (10 mice), whereas neurons active during CFC were labeled in the CFC group (11 mice). After remote memory recall test, brain tissues were immunolabeled for c-Fos. c, Freezing behavior during remote memory recall. NS, not significant. d, Images showing mPFC/PL neurons labeled with tdT (red) or c-Fos (green). Neurons labeled with both tdT and c-Fos are circled. e, Comparisons of the tdT+ cell density, c-Fos+ cell density and c-Fos+ proportion among all tdT+ neurons in the mPFC/PL. Unpaired t test (HC group: eight mice, CFC group: seven mice). f, Images showing BLA neurons labeled with tdT (red) or c-Fos (green). g, Comparisons of the tdT+ cell density, c-Fos+ cell density and c-Fos+ proportion among all tdT+ neurons in the BLA. Unpaired t-test (HC group: six mice, CFC group: seven mice). h, Experimental setup for (i–l). mPFC neurons active during CFC expressed ChR2-eYFP or eYFP. i, Four weeks after CFC, the mice received 5 Hz photostimulation in Context B. j, Image showing optical cannula tips (arrows) and ChR2-eYFP+ mPFC neurons (green). k,l, Summary plot showing the average freezing time in the presence and absence of photostimulation in the ChR2 (13 mice) and eYFP groups (nine mice). Repeated measures two-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons (group × behavioral session interaction, P < 0.01). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

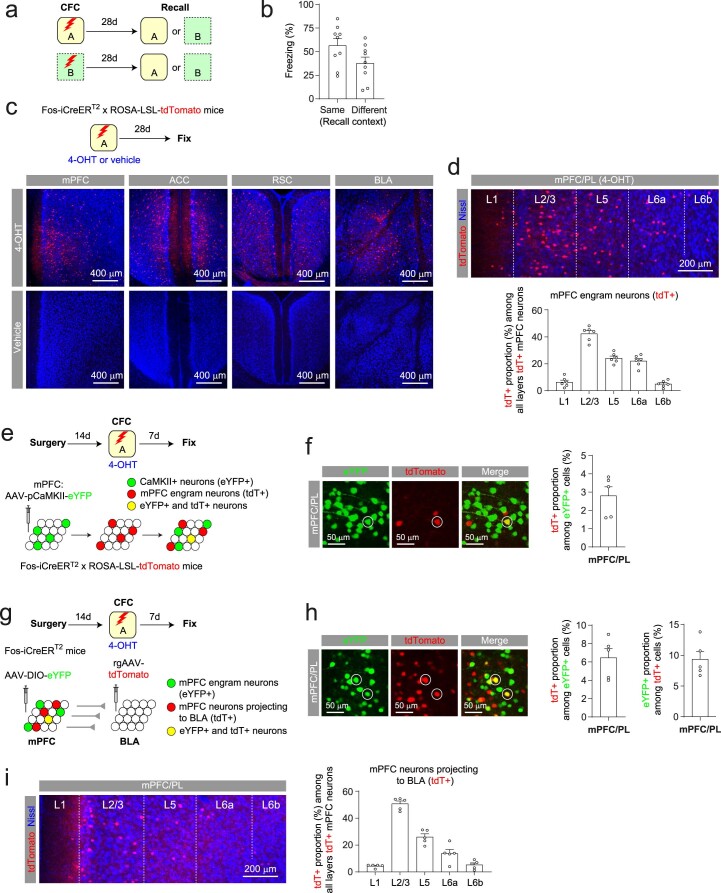

Extended Data Fig. 1. Labeling of mPFC engram neurons and their proportions among all CaMKII+ neurons and among all BLA projectors.

(a) Mice were fear conditioned in Context A or B and tested for remote memory recall in the same (9 mice) or different context (9 mice). (b) Quantification of freezing behavior during remote memory recall as in (a). Mice tested in the same contexts tended to display more freezing behavior than mice tested in different contexts (p = 0.07, unpaired t-test). (c) Neurons active during CFC (engram neurons) were labeled with tdTomato (tdT). Images show tdT+ neurons (red) in mPFC, caudal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), retrosplenial cortex (RSC), and basolateral amygdala (BLA) in mice that received 4-OHT but not vehicle injection after CFC (Blue: Nissl stain). (d) Top: tdT+ neurons (red) in different mPFC/PL layers in 4-OHT-injected mice in (c). Bottom: proportion of tdT+ neurons in each mPFC/PL layer among all tdT+ neurons (6 mice). (e) Experimental setup for (f). CaMKII+ mPFC pyramidal neurons expressed eYFP, whereas neurons active during CFC expressed tdT. (f) Left: eYFP+ (green) or tdT+ (red) mPFC/PL neurons. A both eYFP+ and tdT+ neuron is circled. Right: proportion of tdT+ neurons among all eYFP+ mPFC neurons (5 mice). (g) Experimental setup for (h)-(i). mPFC neurons projecting to BLA (BLA projectors) were retrogradely labeled with tdT. mPFC neurons active during CFC expressed eYFP. (h) Left: tdT+ (red) or eYFP+ (green) mPFC/PL neurons. Both tdT+ and eYFP+ neurons are circled. Middle: proportion of tdT+ neurons among all eYFP+ mPFC neurons. Right: proportion of eYFP+ neurons among all tdT+ mPFC neurons (5 mice). (i) Left: BLA projectors (tdT+, red) in different mPFC/PL layers. Right: proportion of BLA projectors in each mPFC/PL layer among all BLA projectors in mPFC (5 mice). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

We examined whether the reactivation of mPFC neurons active during CFC induced memory recall. After surgery for virus injection and optical cannula implantation, mice were fear conditioned in Context A to induce ChR2-eYFP or eYFP expression in mPFC neurons active during CFC (Fig. 1h–j). Four weeks after CFC, the mice were placed in Context B and received 5 Hz photostimulation, which substantially increased freezing behavior in the ChR2 group (laser off, 17.4 ± 2.9%; laser on, 29.6 ± 5.7%; mean ± s.e.m, 13 mice) but not in the eYFP group (laser off, 20.6 ± 4.2%; laser on, 18.7 ± 4.9%; 9 mice; Fig. 1k, l and Supplementary Table 2). Thus, the reactivation of mPFC neurons active during CFC induced fear in an irrelevant context. Our results suggest that a subset of mPFC neurons active during CFC was reactivated during remote memory recall, and optogenetic reactivation of these neurons induced memory recall. Thus, we termed these labeled mPFC neurons ‘mPFC engram neurons’16.

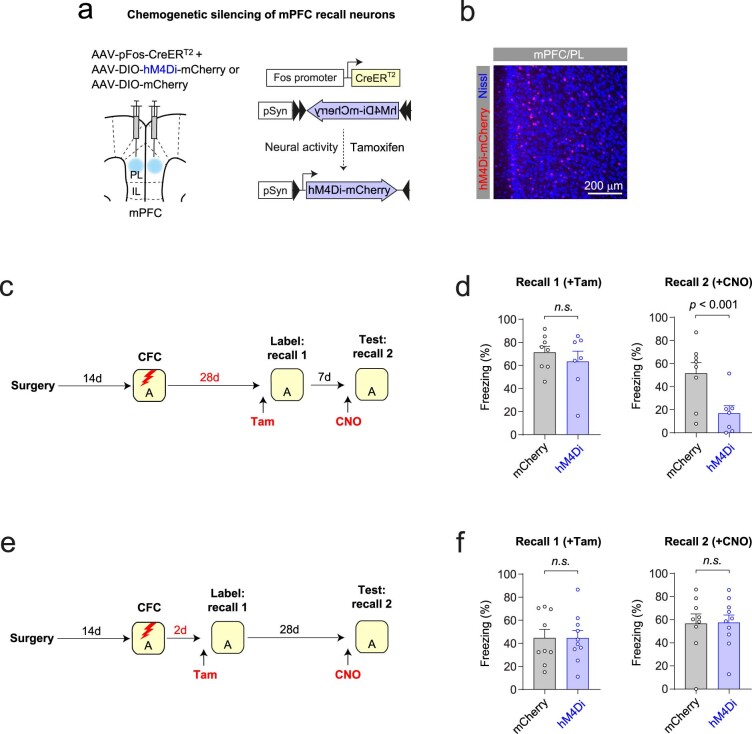

Strengthening of PFC engram circuit in systems consolidation

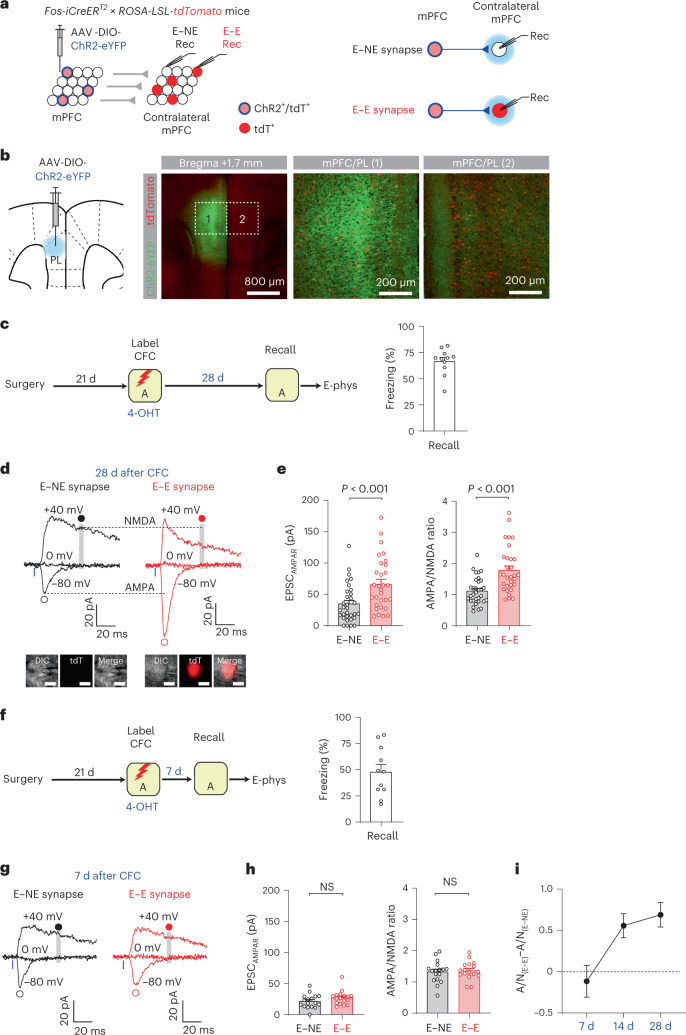

We next examined if remote memory consolidation might strengthen connections between mPFC engram neurons to store remote contextual memories. AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was unilaterally injected into the mPFC/PL in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice (Fig. 2a,b). Four weeks after CFC, the mice were tested for remote memory recall and brain slices were prepared for electrophysiological recordings (Fig. 2c). Engram neurons in the AAV-injected mPFC expressed ChR2-eYFP and tdT, whereas engram neurons in the contralateral mPFC expressed only tdT (Fig. 2b). ChR2-eYFP+ axons of mPFC engram neurons, which we termed ‘mPFC engram inputs’, were sparsely distributed in the contralateral mPFC (Fig. 2b). Photostimulation of ChR2+ interhemispheric mPFC engram inputs induced excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) recorded in mPFC layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. EPSCs recorded in tdT+ engram neurons and tdT- nonengram (NE) neurons reflected synaptic responses in engram inputs to engram neurons (E–E synapses) and those inputs to nonengram neurons (E–NE synapses), respectively (Fig. 2a). Compared with E–NE synapses, E–E synapses displayed larger AMPA receptor (AMPAR)-mediated EPSCs (Fig. 2d,e). To compare synaptic strength, we recorded both AMPAR and NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-mediated EPSCs in the same mPFC neurons and calculated the AMPA/NMDA ratio17,18, which was also higher in E–E synapses than in NE–E synapses (Fig. 2d,e). Thus, interhemispheric mPFC engram inputs were more strongly connected to mPFC engram neurons than to nonengram neurons 28 d after CFC. Such synaptic changes were also observed 14 d but not 7 d after CFC (Fig. 2f–i and Extended Data Fig. 2f–h), suggesting that mPFC E–E synapses were gradually strengthened during systems consolidation. The strengthening of mPFC E–E synapses was not induced by remote memory recall because the same temporal pattern of synaptic changes was observed without memory recall before recordings (Extended Data Fig. 2a–e,i–m). Consistent with this, silencing of mPFC engram neurons inhibited memory recall 28 d but not 7 d after CFC (Extended Data Fig. 3), suggesting that remote memory recall requires the activity of mPFC engram neurons.

Fig. 2. Progressive strengthening of interhemispheric excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons during remote memory consolidation.

a, Photostimulation activated ChR2+ engram inputs. Postsynaptic responses recorded in tdT− nonengram (E–NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E–E synapses). b, Engram neurons in the AAV-injected mPFC (1) expressed ChR2-eYFP (green) and tdT (red). ChR2-eYFP+ axons and tdT+ engram neurons were detected in the contralateral mPFC (2). c, Experimental setup for d and e. Four weeks after CFC, mice were tested for remote fear memory recall (11 mice) and recording experiments were performed. d, Traces of EPSCs in E–NE (black) and E–E synapses (red). Blue light (blue bars) activated ChR2+ engram inputs and induced EPSCs recorded in a tdT− nonengram neuron and an adjacent tdT+ engram neuron (red, inset; scale bar, 10 μm). EPSCs were recorded at –80, 0, and +40 mV in voltage-clamp mode in the presence of SR-95531. AMPAR EPSCs were recorded at –80 mV (open circles). NMDAR EPSCs were recorded at +40 mV (gray vertical lines and closed circles). e, Left: comparison of AMPAR EPSC (EPSCAMPAR) induced by the photostimulation of the same intensity (20.5 mW mm–2). Right: comparison of the AMPA/NMDA ratios. n = 32 (E–NE) and 31 (E–E). Two-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons was used to analyze combined data in e and h. f, Experimental setup for g and h. Seven days after CFC, mice were tested for fear memory recall (11 mice), and recording experiments were performed. g, Traces of EPSCs in E–NE (black) and E–E synapses (red) induced and recorded as in d. h, Comparison of EPSCAMPAR (left) and the AMPA/NMDA (right) ratios. n = 17 neurons/group. i, Comparison of difference in the AMPA/NMDA (A/N) ratio between E–NE and E–E synapses in mice examined 7 d (10 pairs), 14 d (15 pairs) and 28 d (30 pairs) after CFC. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

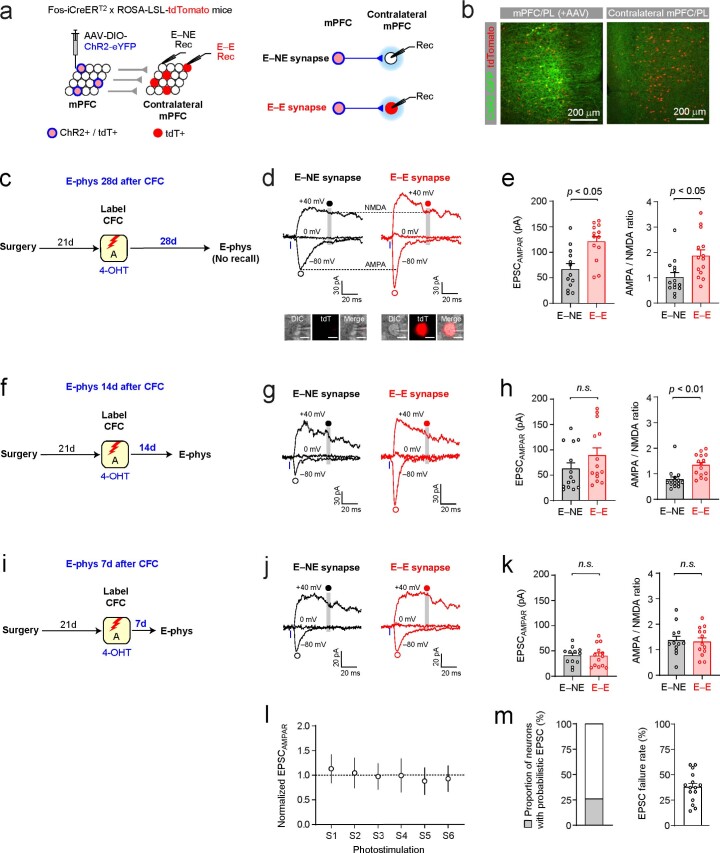

Extended Data Fig. 2. Progressive strengthening of interhemispheric excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons during remote memory consolidation.

(a) Photostimulation activated ChR2+ engram inputs. EPSCs were recorded in tdT− nonengram (E−NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E−E synapses) in contralateral mPFC. (b) Left: ChR2-eYFP+ (green) and tdT+ (red) engram neurons in AAV-injected mPFC. Right: ChR2-eYFP+ axons and tdT+ engram neurons in contralateral mPFC. (c) Experimental setup for (d, e). Four weeks after CFC, electrophysiological experiments (E-phys) were performed without memory recall (4 mice). (d) Traces of EPSCs in E−NE and E−E synapses. EPSCs were induced and recorded as in Fig. 2d. (e) Left: comparison of EPSCAMPAR induced by 20.5 mW/mm2 photostimulation in tdT− and tdT+ neurons (13 pairs). Right: comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratios (14 pairs). Paired t-test. (f) Experimental setup for (g, h). Two weeks after CFC, recording experiments were performed (4 mice). (g) Traces of EPSCs in E−NE and E−E synapses. (h) Comparison of EPSCAMPAR (14 pairs of tdT− and tdT+ neurons) and AMPA/NMDA ratios (15 pairs). Paired t-test. (i) Experimental setup for (j)-(k). Seven days after CFC, recording experiments were performed without memory recall (4 mice). (j) Traces of EPSCs in E−NE and E−E synapses. (k) Comparison of EPSCAMPAR (12 pairs of tdT− and tdT+ neurons) and AMPA/NMDA ratios (12 pairs). Paired t-test. (l) Quantification of peak amplitudes of EPSCAMPAR induced by 6 photostimulations (S1-S6, 20 s interval) and normalized to average peak amplitude in each neuron (57 neurons, data from (i–k) and Fig. 2f–h). (m) In 26.3% of 57 neurons examined in (l), photostimulation did not induce EPSC at least once (left), and EPSCs were probabilistic with an average failure rate of 37.8 ± 4.8%. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM in (e), (h), (k), and (m) or as the mean ± standard deviation in (l).

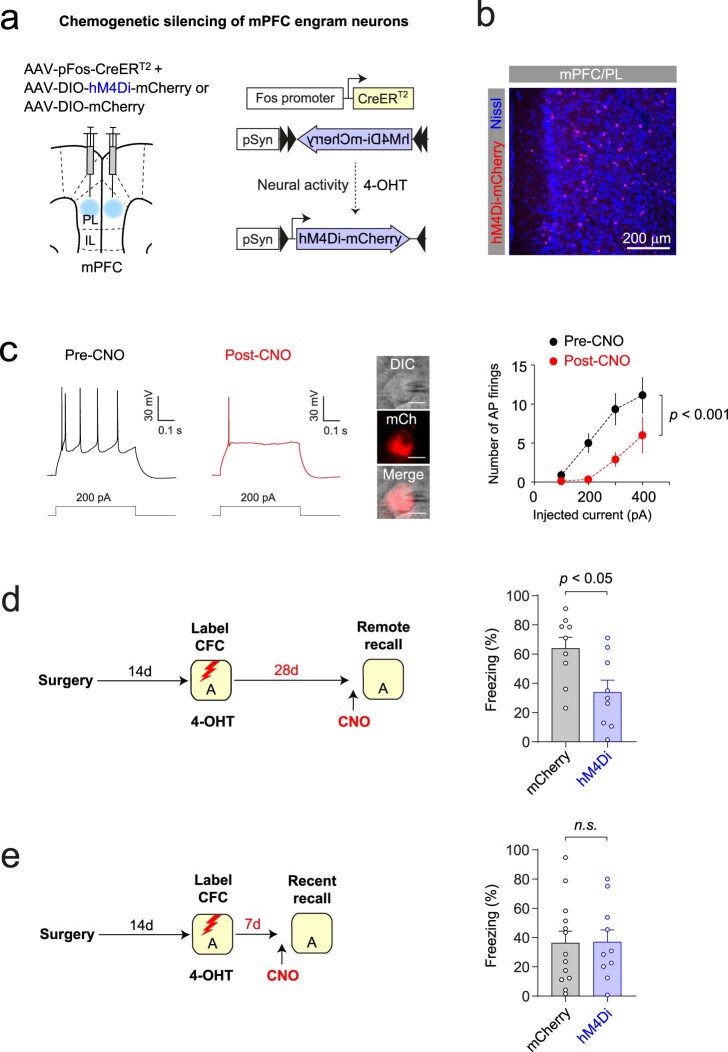

Extended Data Fig. 3. Chemogenetic silencing of mPFC engram neurons inhibited remote but not recent memory recall.

(a) Experimental setup. A mixture of AAV-pFos-CreERT2 and AAV-DIO- hM4Di-mCherry (hM4Di group) or AAV-DIO-mCherry (mCherry group) was bilaterally injected to the mPFC. mPFC engram neurons active during CFC expressed hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry. (b) Image showing mPFC engram neurons expressing hM4Di-mCherry (red). Blue fluorescence indicates Nissl stain. (c) Left: traces of AP firing before (pre-CNO) and 5 minutes after CNO application (10 μM, post-CNO). AP firing was induced by depolarizing current injection (500 ms long) and recorded in the same hM4Di-mCherry (mCh)-expressing mPFC neuron (inset; scale bar, 10 μm) in current-clamp mode. Right: summary plot of AP firing in 9 mPFC neurons expressing hM4Di-mCherry. *** p < 0.001 (pre-CNO versus post-CNO, repeated measures two-way ANOVA). (d) Left: mPFC engram neurons active during CFC in Context A were labeled with hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry. Four weeks after CFC, the mice received a CNO injection and were tested for fear memory recall in the same context 45–60 minutes later. Right: summary plot showing the average freezing time in the hM4Di (9 mice) and mCherry groups (9 mice). Unpaired t-test. (e)Left: mPFC engram neurons active during CFC in Context A were labeled with hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry. Seven days after CFC, the mice received a CNO injection and were tested for fear memory recall in the same context 45–60 minutes later. Right: summary plot showing the average freezing time in the hM4Di (10 mice) and mCherry groups (13 mice). Unpaired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

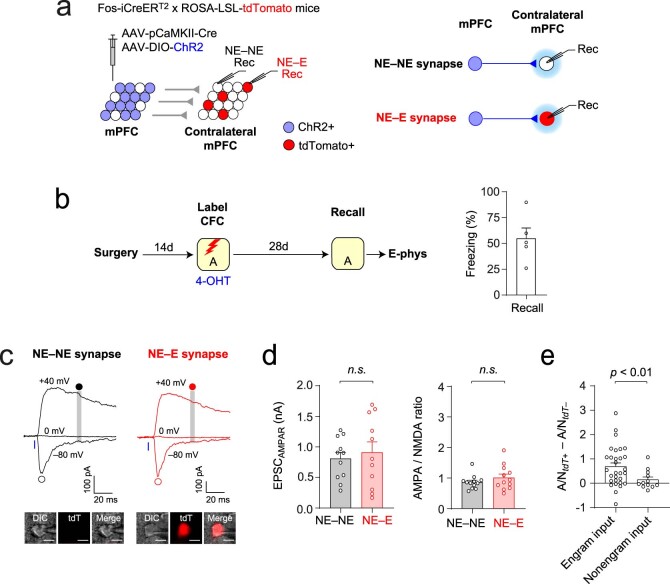

We also examined whether synaptic strengthening associated with systems consolidation was input specific. ChR2-eYFP was globally expressed in CaMKII+ pyramidal neurons in the AAV-injected mPFC (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). As engram neurons constitute only a small subset of CaMKII+ mPFC neurons (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f), most ChR2-eYFP+ axons were nonengram inputs. Four weeks after CFC, photostimulation of ChR2-eYFP+ axons induced EPSCs in tdT+ engram (NE–E synapses) and tdT− nonengram neurons (NE–NE synapses) in the contralateral mPFC. AMPAR-mediated EPSCs or the AMPA/NMDA ratio did not differ between NE–E and NE–NE synapses (Extended Data Fig. 4c–e), suggesting that nonengram inputs to mPFC engram neurons were not strengthened. Thus, remote memory consolidation involves synapse-specific strengthening of excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons, which we termed the ‘mPFC engram circuit’.

Extended Data Fig. 4. mPFC nonengram inputs to mPFC engram neurons were not strengthened after remote memory consolidation.

(a) Left: AAV-pCaMKII-Cre and AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP were unilaterally injected into the mPFC/PL in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. ChR2-eYFP was globally expressed in CaMKII+ pyramidal neurons of the AAV-injected mPFC (blue), whereas mPFC engram neurons expressed tdT (red). Right: in the contralateral mPFC, photostimulation activated ChR2+ axons of nonengram mPFC neurons. Postsynaptic responses recorded in nonengram (NE, tdT−) and engram neurons (E, tdT+) reflected those in nonengram inputs to nonengram neurons (NE−NE synapses) and to engram neurons (NE−E synapses), respectively. (b) Left: mice were fear conditioned in Context A and received a 4-OHT injection to label mPFC engram neurons with tdT. They were tested for contextual memory recall 28 days later. Right: quantification of freezing behavior during memory recall (5 mice). (c) Representative traces of EPSCs in NE−NE (black) and NE−E synapses (red). EPSCs were induced by the photostimulation (blue bars) of nonengram mPFC inputs and recorded in a pair of tdT− nonengram (NE−NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (NE−E synapses). AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs were recorded and quantified as in Fig. 2d. Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). (d) Left: comparison of the peak amplitude of AMPAR EPSC (EPSCAMPAR) induced by photostimulation of the same intensity (20.5 mW/mm2) and recorded in 11 pairs of nonengram (NE−NE synapses) versus engram neurons (NE−E synapses). Right: comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratios in 12 pairs of nonengram (NE−NE synapses) versus engram neurons (NE−E synapses). n.s., nonsignificant. Paired t-test. (e) Comparison of difference in AMPA/NMDA (A/N) ratio between E−NE and E−E synapses (engram inputs; 30 pairs, data from Fig. 2e) with difference in AMPA/NMDA ratio between NE−NE and NE−E synapses (nonengram inputs; 12 pairs, data from (d)). Unpaired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

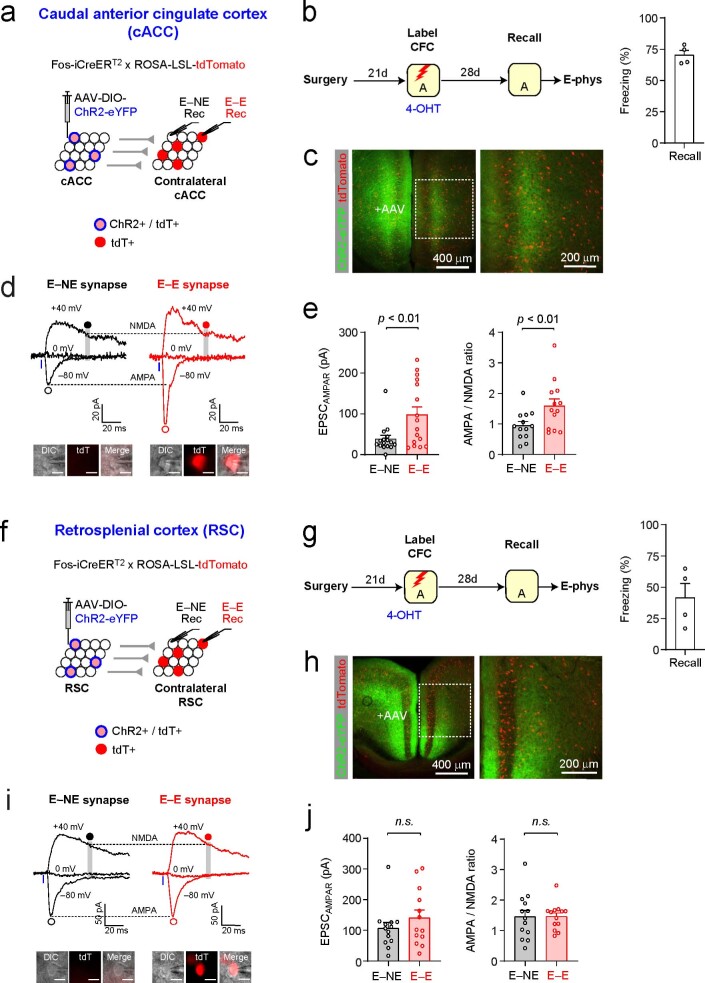

We next examined whether systems consolidation also strengthened engram circuits in the caudal ACC (cACC) and retrosplenial cortex (RSC) implicated in the consolidation and retrieval of remote contextual memories9,19,20 (Extended Data Fig. 5). In the cACC, both AMPAR EPSCs and the AMPA/NMDA ratio were substantially larger in E–E synapses than in E–NE synapses 28 d after CFC, whereas such differences were not detected in the RSC. These results suggest that certain neocortical engram circuits are more likely to undergo synaptic changes during systems consolidation.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Remote memory consolidation strengthened interhemispheric excitatory connections between engram neurons in the cACC, but not in the RSC.

(a) Experimental setup for (b–e). AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was unilaterally injected into caudal ACC (cACC) in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. Photostimulation of ChR2+ engram inputs induced postsynaptic responses in nonengram (tdT−, E−NE synapses) and engram neurons (tdT+, E−E synapses) in contralateral cACC. (b) Mice were tested for memory recall 28 days after CFC (4 mice). (c) Engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP (green) and tdT (red) in AAV-injected cACC (left). Contralateral cACC indicated by a dotted square is magnified in the right panel, showing tdT+ engram neurons and ChR2-eYFP+ axons. (d)Traces of EPSCs induced and recorded as in Fig. 2d. Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). (e) Left: comparison of the amplitude of AMPAR EPSC induced by 20.5 mW/mm2 photostimulation and recorded in tdT− and tdT+ neurons (16 pairs). Right: comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratio (13 pairs). Paired t-test. (f) Experimental setup for (g–j). AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was unilaterally injected into retrosplenial cortex (RSC) in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. Photostimulation of ChR2+ engram inputs induced postsynaptic responses in nonengram (tdT−, E−NE synapses) and engram neurons (tdT+, E−E synapses) in contralateral RSC. (g) Mice were tested for memory recall 28 days after CFC (4 mice). (h) Engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP (green) and tdT (red) in AAV-injected RSC (left). Contralateral RSC indicated by a dotted square is magnified in the right panel, showing tdT+ engram neurons and ChR2-eYFP+ axons. (i) Traces of EPSCs induced and recorded as in Fig. 2d. Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). (j) Left: comparison of the amplitude of AMPAR EPSC induced by 20.5 mW/mm2 photostimulation and recorded in tdT− and tdT+ neurons (13 pairs). Right: comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratio (13 pairs). Paired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

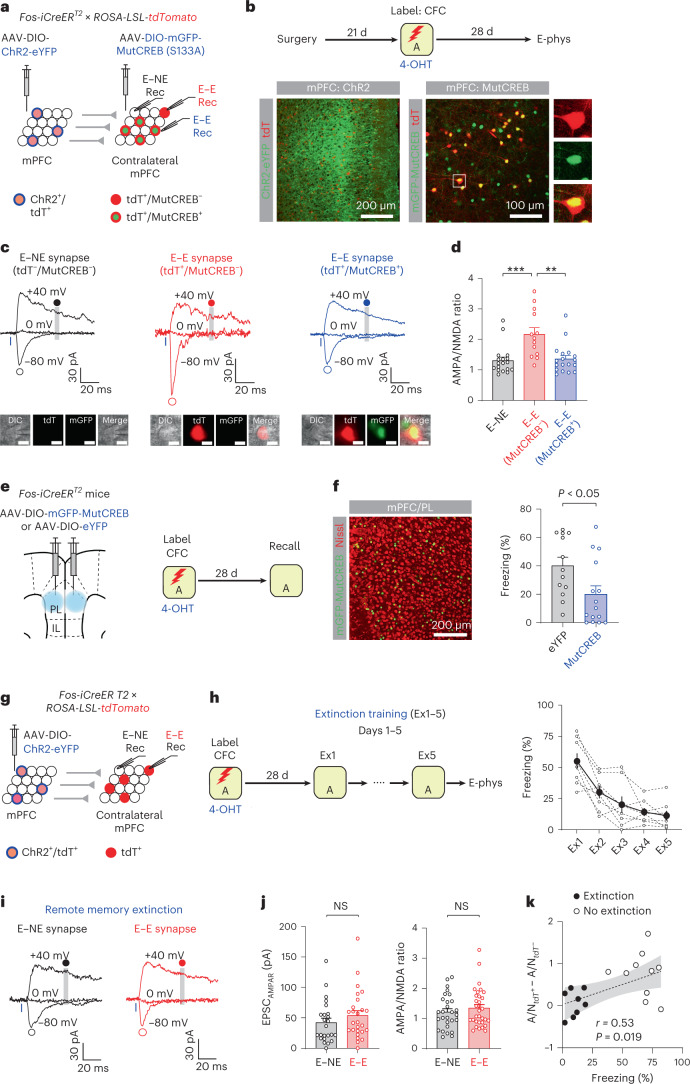

CREB-dependent strengthening of mPFC engram circuit

In a previous study, the inhibition of CREB in mPFC engram neurons prevented remote memory consolidation10. Since CREB is essential for neuronal plasticity21, CREB inhibition may block the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit, thereby preventing systems consolidation. To test this, we inhibited CREB in mPFC engram neurons with dominant-negative mutant CREB(S133A) or MutCREB10 after CFC and examined how this affected the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit. mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP and tdT, while some tdT+ engram neurons in the contralateral mPFC expressed mGFP-MutCREB (Fig. 3a,b). Photostimulation of ChR2+ engram inputs induced EPSCs in tdT+/MutCREB− engram neurons (E–E synapses), tdT+/MutCREB+ engram neurons (E–E synapses) and tdT−/MutCREB− nonengram neurons (E–NE synapses) (Fig. 3c). The AMPA/NMDA ratio was substantially larger in tdT+/MutCREB− engram neurons than in tdT+/MutCREB+ engram neurons or tdT−/MutCREB− nonengram neurons and did not differ between tdT+/MutCREB+ neurons and tdT−/MutCREB− neurons (Fig. 3c,d), indicating that MutCREB expression in postsynaptic mPFC neurons prevented the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit. Thus, CREB in mPFC engram neurons is indispensable for the strengthening of the mPFC circuit during systems consolidation. Moreover, overexpression of MutCREB in mPFC engram neurons after CFC also inhibited remote memory recall (Fig. 3e,f), suggesting the critical role of CREB in remote memory consolidation and/or recall.

Fig. 3. Strengthening of mPFC engram circuit required CREB and remote memory extinction weakened mPFC engram circuit.

a, Experimental setup for b–d. Photostimulation of ChR2+ engram inputs induced EPSCs in nonengram (tdT−/MutCREB−, E–NE synapses) and engram neurons (tdT+/MutCREB− or tdT+/MutCREB+, E–E synapses). b, Top: 28 d after CFC, recording experiments were performed. Bottom: images showing ChR2-eYFP+ (green) and/or tdT+ (red) mPFC engram neurons (left) and those labeled with mGFP-MutCREB (green) and/or tdT+ (red) in contralateral mPFC (right). c, Traces of EPSCs in E–NE (tdT−/MutCREB−, black), E–E (tdT+/MutCREB−, red) and E–E synapses (tdT+/MutCREB+, blue). AMPAR EPSCs and NMDAR EPSCs were recorded as in Fig. 2d. Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). d, Comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratios between E–NE (18 cells), E–E (tdT+/MutCREB−, 13 cells) and E–E synapses (tdT+/MutCREB+, 18 cells). One-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). e, Experimental setup for f. mPFC engram neurons expressed mGFP-MutCREB or eYFP. Mice were tested for memory recall 28 d after CFC. f, Left: image showing mGFP-MutCREB+ mPFC neurons (green). Right: freezing behavior during memory recall in MutCREB (15 mice) and eYFP groups (13 mice). Unpaired t-test. g, Experimental setup for h–j. Photostimulation of mPFC engram inputs induced EPSCs in tdT− nonengram (E–NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E–E synapses). h, Left: 28 d after CFC, mice received extinction training for 5 d (Ex1-5). Right: freezing behavior during extinction training (eight mice). i, Traces of EPSCs in E–NE (black) and E–E synapses (red). j, Comparison of EPSCAMPAR (24 cells for E–NE, 26 cells for E–E synapses) and AMPA/NMDA ratio (28 cells for E–NE, 32 cells for E–E synapses). Unpaired t-test. k, Average difference in AMPA/NMDA ratio between tdT+ and tdT– neurons in each mouse positively correlated with freezing behavior (Pearson correlation test). In the extinction group (eight mice), freezing scores during the last extinction session were used. In the no extinction group (11 mice), data in Fig. 2c–e were used. Gray shaded area indicates 95% confidence bands on the best-fitting regression line. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Extinction of remote memories weakened mPFC engram circuit

After CFC, repeated exposure to the threat-predictive context without the US induces the extinction of contextual fear memories. We examined how remote memory extinction affected mPFC engram circuit. Four weeks after CFC, extinction training for 5 d gradually decreased freezing behavior in Context A (Fig. 3g,h). After extinction training, neither AMPAR EPSCs nor the AMPA/NMDA ratio differed between E–E and E–NE synapses in the mPFC (Fig. 3i,j), suggesting that remote memory extinction weakened E–E synapses previously strengthened during systems consolidation. Overall, the average difference in the AMPA/NMDA ratio between E–E and E–NE synapses in each mouse correlated with freezing behavior during the last recall session (Fig. 3k), suggesting that systems consolidation strengthens mPFC engram circuit, while remote memory extinction weakens the engram circuit.

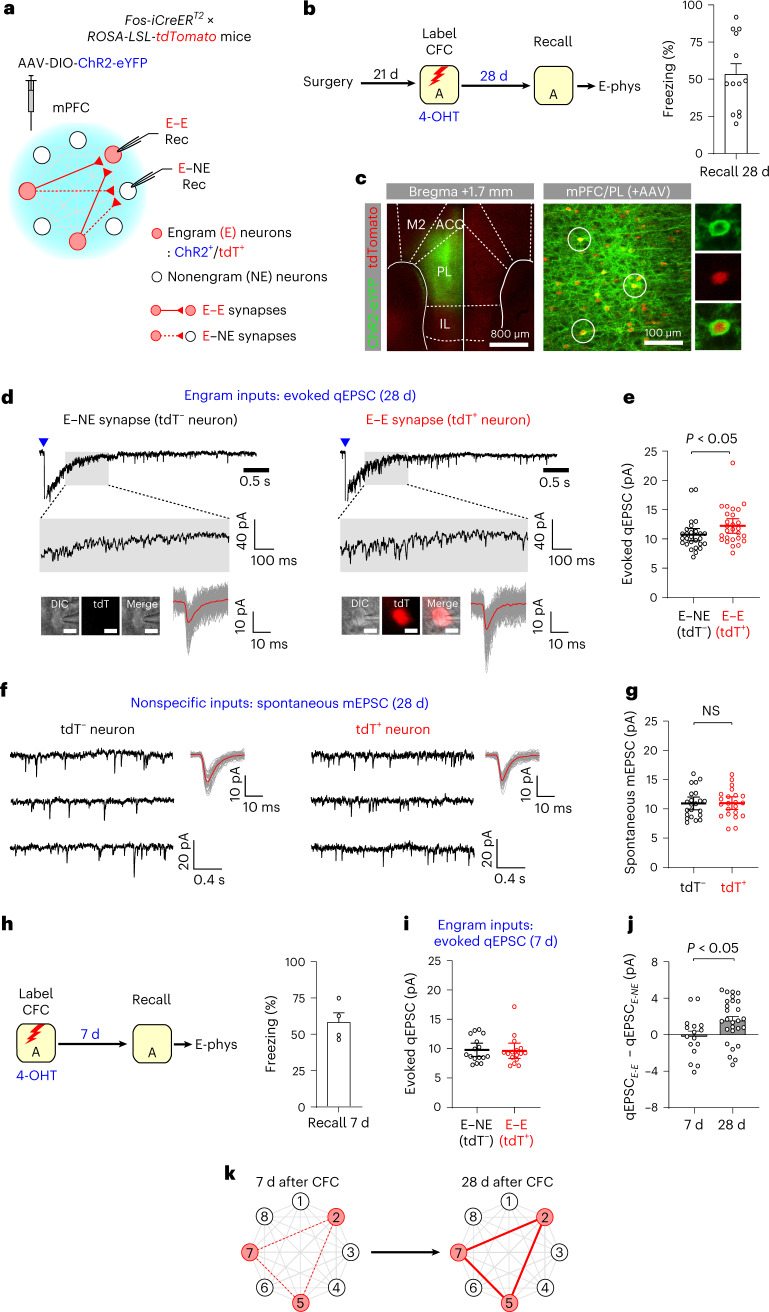

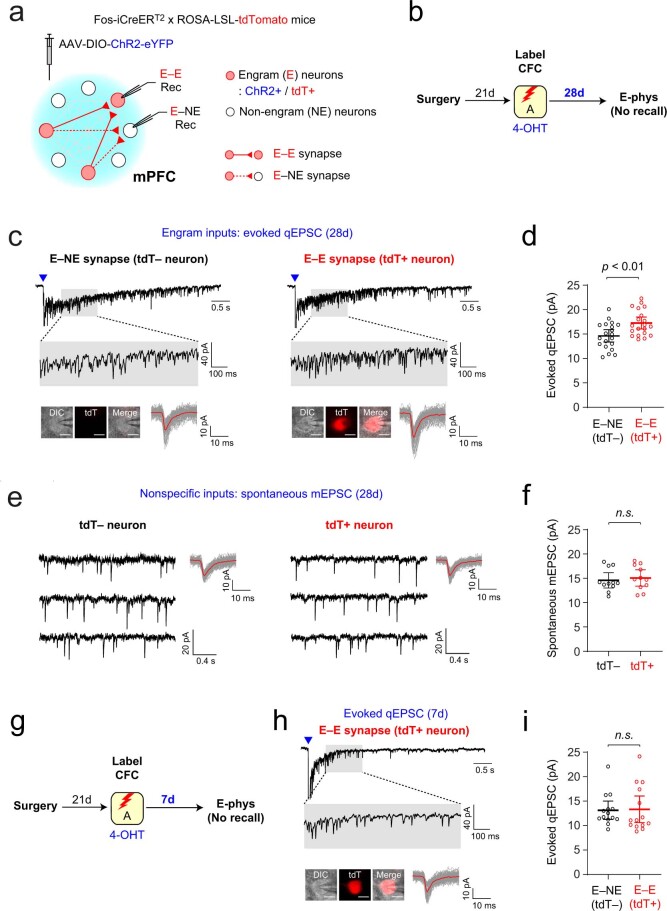

Strengthening of local mPFC circuit in systems consolidation

Our results suggest that remote memory consolidation involves the strengthening of interhemispheric connections between mPFC engram neurons. We next examined whether local excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons were also strengthened after systems consolidation. Four weeks after CFC, mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2 and tdT (Fig. 4a–c). Photostimulation of ChR2+ engram neurons induced EPSCs recorded in adjacent engram and nonengram neurons in the ipsilateral mPFC. In engram neurons, we isolate EPSCs from ChR2-mediated photocurrents by inducing asynchronous glutamate release from presynaptic engram inputs in Ca2+-free and 4 mM Sr2+-containing extracellular solution22, which also contained tetrodotoxin (TTX, 1 μM) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 1 mM) to prevent postsynaptic EPSCs23 (Fig. 4d). Evoked quantal EPSCs (qEPSCs) were recorded in tdT+ engram and tdT− nonengram neurons at −80 mV in voltage-clamp mode and calculated the average peak amplitude of all detected qEPSCs in each neuron as an index of synaptic strength24. qEPSCs amplitude was substantially larger in engram neurons than in nonengram neurons (Fig. 4e), indicating stronger local excitatory connections in E–E synapses than in E–NE synapses 28 d after CFC. To compare synaptic strength in nonspecific inputs to mPFC engram versus nonengram neurons, we also recorded spontaneous miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs), whose amplitude did not differ between engram and nonengram neurons (Fig. 4f,g), suggesting that systems consolidation did not alter synaptic strength in nonspecific inputs to engram neurons.

Fig. 4. Progressive strengthening of local recurrent excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons during remote memory consolidation.

a, Photostimulation activated local recurrent axons of ChR2+ engram neurons and induced postsynaptic responses recorded in engram (tdT+, E–E synapses) and nonengram neurons (tdT−, E–NE synapses). b, Experimental setup for c–g. Four weeks after CFC, the mice were tested for remote memory recall (13 mice). c, Images showing ChR2-eYFP+ (green) and tdT+ (red) mPFC engram neurons. d, Traces of evoked qEPSCs induced by the photostimulation (blue triangles) of local recurrent engram inputs and recorded in tdT− nonengram (E–NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E–E synapses). The average qEPSC (red) was overlaid onto individual qEPSCs (gray). Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). e, Comparison of the average peak amplitude of evoked qEPSCs recorded in 27 pairs of nonengram (E–NE synapses) and engram neurons (E–E synapses). Two-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons was used to analyze combined data in e and g. f, Traces of spontaneous mEPSCs in nonspecific inputs to tdT– nonengram and tdT+ engram neuron. mEPSCs were recorded at −80 mV in the presence of TTX. Average mEPSCs (red) were overlaid onto individual mEPSCs (gray). g, Comparison of the peak amplitude of spontaneous mEPSCs recorded in 22 pairs of nonengram and engram neurons. h, Experimental setup for i. Seven days after CFC, the mice were tested for memory recall (four mice). i, Comparison of the peak amplitude of evoked qEPSCs recorded in 16 pairs of nonengram (E–NE synapses) and engram neurons (E–E synapses) 7 d after CFC. j, Comparison of difference in evoked qEPSC amplitude between E–NE and E–E synapses in mice examined 7 d (16 pairs) versus 28 d after CFC (27 pairs). Unpaired t-test. k, Local recurrent excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons were gradually strengthened during systems consolidation. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. in b, h and j, whereas data are presented as the mean ± 95% confidence interval in e, g and i. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

We also recorded evoked qEPSC 7 d after CFC and found no difference in qEPSC amplitude between E–E and E–NE synapses (Fig. 4h–j), indicating that local mPFC engram circuit was not yet strengthened 7 d after CFC (Fig. 4k). The strengthening of local mPFC engram circuit was not induced by remote memory recall as the same temporal pattern of synapse-specific strengthening was observed without memory recall before recordings (Extended Data Fig. 6). As mPFC GABAergic interneurons are involved in encoding conditioned fear memories25,26, we next examined synaptic changes in inhibitory engram inputs to mPFC pyramidal neurons. CFC induced ChR2-eYFP and tdT expression in both excitatory and inhibitory engram neurons (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). After 28 d, we photostimulated ChR2+ mPFC engram inputs and recorded inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) in tdT− or tdT+ pyramidal neurons at 0 mV in the voltage-clamp mode in the presence of Sr2+, TTX, 4-AP and NBQX. qIPSC amplitude was substantially smaller in tdT+ neurons than in tdT− neurons (Extended Data Fig. 7c,d), indicating weaker GABAergic engram inputs to mPFC engram neurons than those inputs to nonengram neurons. Thus, mPFC engram neurons receive weaker inhibitory engram inputs than other neurons.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Strengthening of local recurrent excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons during remote memory consolidation.

(a) Photostimulation activated local recurrent axons of ChR2+ engram neurons and induced postsynaptic responses recorded in engram (tdT+, E−E synapses) and nonengram neurons (tdT−, E−NE synapses). (b) Experimental setup for (c–f). Four weeks after CFC, electrophysiological experiments (E-phys) were performed without memory recall (5 mice). (c) Traces of evoked qEPSCs induced by photostimulation (blue triangles) of local recurrent engram inputs and recorded in tdT– nonengram (E−NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E−E synapses) as in Fig. 4d. Average qEPSC (red) was overlaid onto individual qEPSCs (gray). Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). (d) Comparison of peak amplitude of evoked qEPSCs recorded 20 pairs of tdT– nonengram (E−NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E−E synapses). Paired t-test. (e) Traces of spontaneous mEPSCs in nonspecific inputs to tdT– nonengram and tdT+ engram neuron. mEPSCs were recorded at −80 mV in the presence of TTX as in Fig. 4f. Average mEPSCs (red) was overlaid onto individual mEPSCs (gray). (f) Comparison of peak amplitude of spontaneous mEPSCs recorded in 11 pairs of tdT– nonengram and tdT+ engram neurons. Paired t-test. (g) Experimental setup for (h, i). Seven days after CFC, electrophysiological experiments (E-phys) were performed without memory recall (4 mice). (h) Traces of evoked qEPSCs induced by photostimulation (blue triangles) of local recurrent engram inputs and recorded in a tdT+ engram neurons (E−E synapses) as in Fig. 4d. Average qEPSC (red) was overlaid onto individual qEPSCs (gray). Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). (i) Comparison of peak amplitude of evoked qEPSCs recorded qEPSCs recorded in 14 pairs of tdT– nonengram (E−NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E−E synapses) 7 days after CFC. Paired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± 95% confidence interval.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Comparison of synaptic strength in local inhibitory engram inputs to mPFC engram versus nonengram pyramidal neurons.

(a) Top: AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP was injected into the mPFC/PL in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP and tdT. Photostimulation activated axons of local GABAergic engram neurons and induced inhibitory postsynaptic responses recorded in engram (E−E synapses) and nonengram pyramidal neurons (E−NE synapses). (b) Left: 28 days after CFC, the mice were tested for the recall of remote contextual fear memories, and electrophysiological experiments were performed. Right: quantification of freezing behavior during memory recall (11 mice). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. (c) Representative traces of quantal IPSCs (qIPSCs) induced by the photostimulation of local GABAergic engram inputs and recorded in a tdT− nonengram pyramidal neuron (E−NE synapses) and a tdT+ engram pyramidal neuron (E−E synapses) in the mPFC. Photostimulation (blue triangles) activated local GABAergic inputs of ChR2+ engram neurons and induced IPSCs in postsynaptic pyramidal neurons. qIPSCs were recorded at 0 mV in voltage-clamp mode. Presynaptic GABA release was desynchronized in Ca2+-free and 4 mM Sr2+-containing extracellular solution. In each neuron, peak amplitudes of well-separated qIPSCs recorded 0.5–1.5 s after photostimulation (gray areas) were calculated and averaged. The average qIPSC (red) was overlaid onto individual qIPSC traces (gray). TTX (1 μM) and 4-AP (1 mM) were added in the extracellular solution to block polysynaptic IPSCs. NBQX (10 μM) was also added to block excitatory glutamatergic transmission. Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). (d) Comparison of the peak amplitude of evoked qIPSCs in GABAergic engram inputs to 24 pairs of nonengram neurons (E−NE synapses) versus engram neurons (E−E synapses). Paired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± 95% confidence interval.

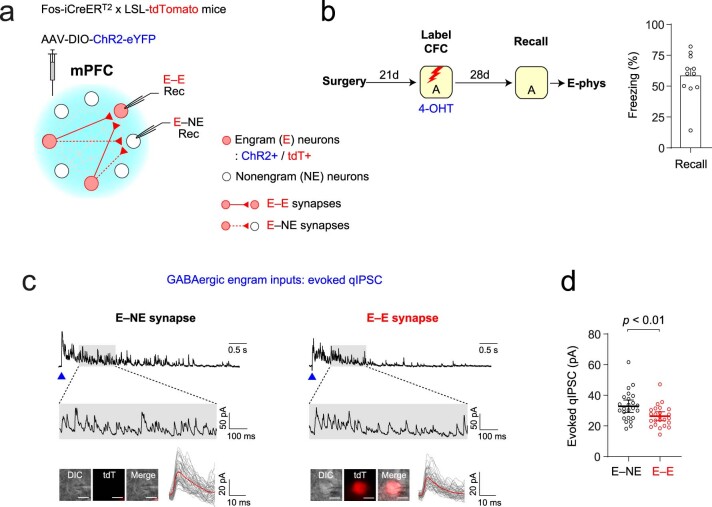

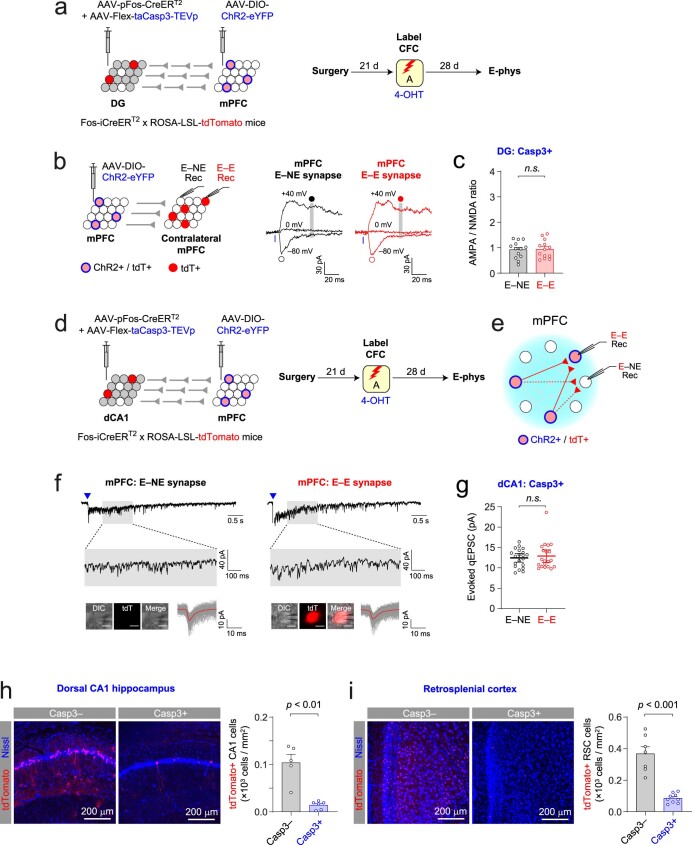

Maturation of mPFC engram requires hippocampal dentate gyrus activity

The dorsal dentate gyrus (DG) has a critical role in mPFC engram maturation during systems consolidation12. To determine how DG contributes to systems consolidation, we genetically ablated DG engram neurons active during CFC and examined how this affected the reactivation of mPFC engram during remote memory recall and the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit. In the Casp3+ group, AAV-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp and AAV-pFos-CreERT2 were bilaterally injected into the dorsal DG in Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice (Fig. 5a). In this group, DG engram neurons expressed tdT and taCasp3-TEVp and underwent taCaspase-3-mediated cell death27, resulting in efficient ablation of DG engram neurons 28 d but not 3 d after CFC (Fig. 5b,c). One day after CFC, mice showed robust freezing behavior in Context A, while mice in the Casp3+ group displayed much less freezing behavior than mice in no Caspase3 (Casp3−) control group 28 d after CFC (Fig. 5d). This suggests that the ablation of DG engram neurons inhibited the consolidation and/or retrieval of remote contextual memories. In both groups, engram neurons were labeled with tdT, whereas neurons active during remote memory recall were immunostained for c-Fos. In both the mPFC/PL and BLA, the proportion of c-Fos+ neurons among all tdT+ engram neurons was substantially lower in the Casp3+ group than in the Casp3− group (Fig. 5e,f), indicating reduced reactivation of engram neurons during remote memory recall when DG engram neurons were ablated.

Fig. 5. Ablation of DG engram neurons after learning inhibited the reactivation of mPFC engram neurons during memory recall and the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit.

a, Experimental setup for b–f. b, Top: mice were tested for memory recall 1 and 28 d after CFC. Brain tissues were immunolabeled for c-Fos (Fos-IHC) after remote memory recall. Bottom: in Casp3+ group, DG engram neurons expressed tdT and taCasp3-TEVp (red circles), resulting in cell death (open circles). c, Left: Casp3-mediated cell death resulted in lower tdT+ DG cell density in Casp3+ group than in Casp3− group 28 d but not 3 d after CFC. Right: tdT+ DG cell density in Casp3+/28 d (10 mice) versus Casp3−/28 d groups (11 mice). Unpaired t-test. d, Freezing behavior during memory recall in Casp3+ (17 mice) and Casp3− groups (nine mice). Repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc comparisons. e, Left: images showing tdT+ and/or c-Fos+ mPFC/PL neurons. Both tdT+ and c-Fos+ neurons are circled. Right: c-Fos+ proportion among all tdT+ mPFC/PL neurons in Casp3− (eight mice) and Casp3+ groups (nine mice). Unpaired t-test. f, Left: images showing tdT+ and/or c-Fos+ BLA neurons. Right: c-Fos+ proportion among all tdT+ BLA neurons in Casp3− (eight mice) and Casp3+ groups (nine mice). Unpaired t-test. g, Experimental setup for h–j. DG engram neurons underwent cell death in Casp3+ group. mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP and tdT. h, Mice in Casp3+ (five mice) and Casp3− groups (four mice) were tested for memory recall 28 d after CFC. i, Left: photostimulation activated local recurrent axons of ChR2+ engram neurons and induced qEPSCs in nonengram (E–NE synapses) and tdT+ engram neurons (E–E synapses) as in Fig. 4d. Right: trace of evoked qEPSCs in E–E synapses. Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). j, Comparison of qEPSC amplitude between nonengram (E–NE synapses) and engram neurons (E–E synapses) in Casp3+ group (20 pairs, left) and in Casp3− group (16 pairs, right). Paired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. in c, d, e, f and h or as the mean ± 95% confidence interval in j. Details of statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

These results raise the possibility that sustained activity of DG engram neurons may strengthen mPFC engram circuit and facilitate mPFC engram maturation during systems consolidation. To test this, we examined how the ablation of DG engram neurons affected the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit. In the Casp3+ group, DG engram neurons underwent Casp3-mediated cell death, and mice showed very weak freezing behavior during remote memory recall (Fig. 5g,h). Photostimulation of local ChR2+ mPFC engram inputs induced qEPSCs, which were recorded in tdT+ engram (E–E synapses) and tdT− nonengram neurons (E–NE synapses) in the presence of Sr2+, TTX and 4-AP (Fig. 5i). In the Casp3+ group, the peak amplitude of evoked qEPSCs did not differ between engram versus nonengram neurons (Fig. 5i,j), indicating the absence of strengthening of local mPFC engram circuit. However, in the Casp3− group, we observed the strengthening of local mPFC engram circuit (Fig. 5j). The ablation of DG engram neurons also inhibited the strengthening of interhemispheric mPFC engram circuit (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c). These results indicate the critical role of DG engram in the strengthening of mPFC engram circuits. Thus, sustained activity of DG engram after learning can contribute to remote memory consolidation possibly by strengthening mPFC engram circuits.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Ablation of dorsal DG or CA1 hippocampal engram neurons inhibited the strengthening of mPFC engram circuits.

(a) Experimental setup for (b, c). DG engram neurons underwent Casp3-mediated cell death. Engram neurons in AAV-injected mPFC expressed ChR2-eYFP and tdTomato (tdT). Recordings experiments were performed 28 days after CFC (4 mice). (b) Left: photostimulation activated ChR2+ interhemispheric engram inputs and induced EPSCs in tdT− nonengram (E−NE) and tdT+ engram neurons (E−E). Right: traces of EPSCs recorded as in Fig. 2d in tdT− and tdT+ neurons. (c) Comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratios (right) in 13 pairs of mPFC nonengram (E−NE) and engram neurons (E−E). Paired t-test. (d) Experimental setup for (e–g). Engram neurons in dorsal CA1 underwent Casp3-mediated cell death. mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP and tdT. Recording experiments were performed 28 days after CFC (5 mice). (e) Photostimulation activated local recurrent axons of ChR2+ engram neurons and induced EPSCs in mPFC nonengram (E−NE) and tdT+ engram neurons (E−E). (f) Traces of evoked qEPSCs recorded as in Fig. 4d in E−NE and E−E synapses. Scale bar, 10 μm. (g) Comparison of peak amplitude of evoked qEPSCs recorded in 20 pairs of mPFC nonengram (E−NE) and engram neurons (E−E). Paired t-test. (h) AAVs were injected to dCA1 as in Fig. 6j in ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. Left: Casp3-mediated cell death in Casp3+ group resulted in lower tdT+ dCA1 cell density compared with Casp3− group. Right: tdT+ dCA1 cell density in Casp3+ (6 mice) and Casp3− groups (5 mice) 28 days after CFC. Unpaired t-test. (i) AAVs were injected to RSC as in Fig. 6j in ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice. Left: Cell death in Casp3+ group resulted in lower tdT+ RSC cell density compared with Casp3− group. Right: tdT+ RSC cell density in Casp3+ (9 mice) and Casp3− groups (7 mice) 28 days after CFC. Unpaired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM in (c), (h), and (i) or as the mean ± 95% confidence interval in (g).

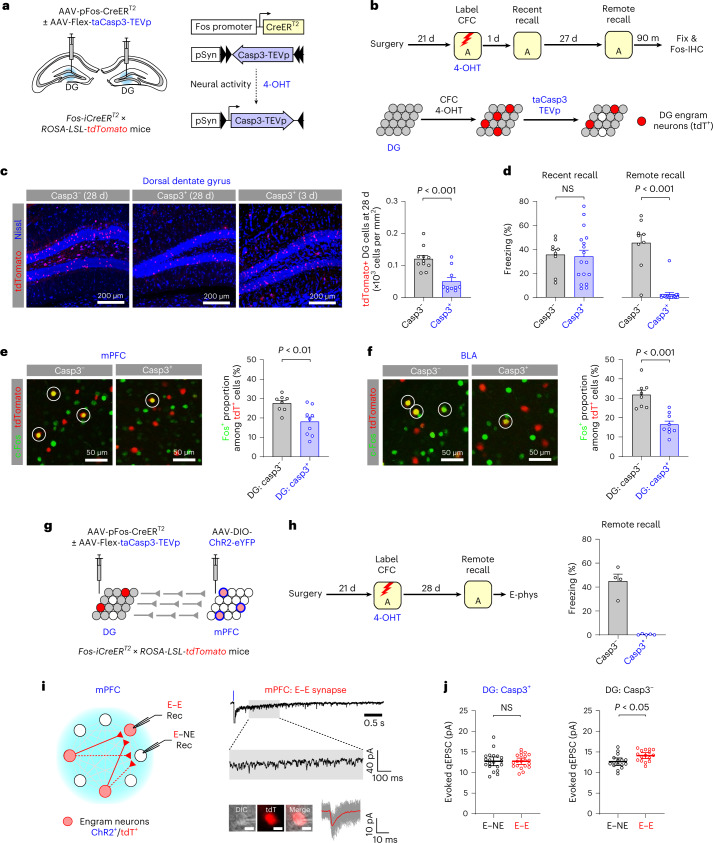

RSC relays hippocampal signal to PFC engram

Dorsal DG engram can contribute to systems consolidation by modulating mPFC activity possibly through the dorsal CA1 hippocampus (dCA1), the major output of the hippocampus. Consistent with this, the ablation of dCA1 engram neurons active during CFC prevented the strengthening of local mPFC engram circuit (Extended Data Fig. 8d–g). As the dCA1 weakly projects to the mPFC28, dCA1 signals may be conveyed to mPFC engram through intermediary areas during systems consolidation. To identify these areas, we examined presynaptic inputs to mPFC engram neurons, using rabies virus (RV)-mediated retrograde (rg) trans-synaptic tracing29. mPFC engram neurons expressed TVA-G-GFP and were infected with EnvA-expressing and G-deficient RV-mCherry, resulting in mCherry expression in neurons monosynaptically projecting to mPFC engram neurons (Fig. 6a–d). mCherry+ neurons were detected in the cACC, RSC, lateral entorhinal cortex (EC), ventral CA1 hippocampus and BLA, while few mCherry+ neurons were found in the dCA1 (Fig. 6e). As the RSC has been implicated in systems consolidation20, we examined whether the RSC might relay signals of dCA1 engram neurons to mPFC engram neurons. dCA1 engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP, while RSC neurons projecting to mPFC engram neurons were labeled with mCherry (Fig. 6f,g). Within the RSC, photostimulation of ChR2-eYFP+ dCA1 engram inputs induced monosynaptic EPSCs in mCherry+ RSC neurons (Fig. 6h), indicating that RSC neurons projecting to mPFC engram neurons received monosynaptic dCA1 engram inputs. These results suggest that a subset of RSC neurons could convey the signal of dCA1 engram to mPFC engram during remote memory consolidation (Fig. 6i). Consistent with this, the ablation of engram neurons in the dCA1 or RSC inhibited remote memory recall (Fig. 6j,k and Extended Data Fig. 8h,i), suggesting that the role of the dCA1−RSC−mPFC circuit in systems consolidation.

Fig. 6. RSC connected hippocampal CA1 engram neurons to mPFC engram neurons.

a, Experimental setup for b–e. mPFC engram neurons expressed TVA-G-GFP, whereas neurons monosynaptically projecting to mPFC engram neurons expressed mCherry. b, After the injection of AAV-pFos-CreERT2 and AAV-DIO-TVA-G-GFP into mPFC, mice underwent CFC and received 4-OHT injection. After 1 week, EnvA-ΔG-RV-mCherry was injected into mPFC. c, Images showing TVA-G-GFP + mPFC neurons (green) and RV-infected mCherry+ mPFC neurons (red). d, TVA-G-GFP (green) was expressed in mPFC engram neurons in mice that received 4-OHT but not vehicle injection after CFC. e, Images showing mCherry+ neurons in cACC, RSC, lateral EC, ventral CA1 and BLA. Note few mCherry+ neurons in dorsal CA1. f, Experimental setup for g–h. mPFC engram neurons expressed TVA-G-GFP, whereas dCA1 engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP. RSC neurons projecting to mPFC engram neurons expressed mCherry. g, Top: after injection of AAVs into mPFC and dCA1, mice underwent CFC and received RV injection into mPFC. Bottom: images showing ChR2-eYFP+dCA1 engram neurons (green, left) and TVA-G-GFP+ mPFC engram neurons (green, right). Middle panel shows mCherry+ RSC neurons (red) and ChR2-eYFP+ dCA1 axons (green). h, Left: traces of EPSCs induced by photostimulation of dCA1 engram inputs and recorded in mCherry+ RSC neurons at −80 mV (red). TTX completely blocked EPSCs (black). Subsequent 4-AP application in the presence of TTX rescued EPSCs (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm (inset). Right: plot of EPSC amplitudes in dCA1 engram inputs to mCherry+ RSC neurons. i, RSC connects dCA1 engram neurons to mPFC engram neurons. dCA1−RSC−mPFC engram circuit can contribute to remote memory consolidation. j, Experimental setup for k. dCA1 or RSC engram neurons active during CFC underwent Casp3-mediated cell death in Casp3+ but not Casp3− group. Mice were tested for memory recall 28 d after CFC. k, Comparison of freezing behavior during remote memory recall between Casp3+ and Casp3− groups for the ablation of dCA1 (left, six mice per group) and RSC engram (right, 10 mice for Casp3+ and 9 mice for Casp3−). Unpaired t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

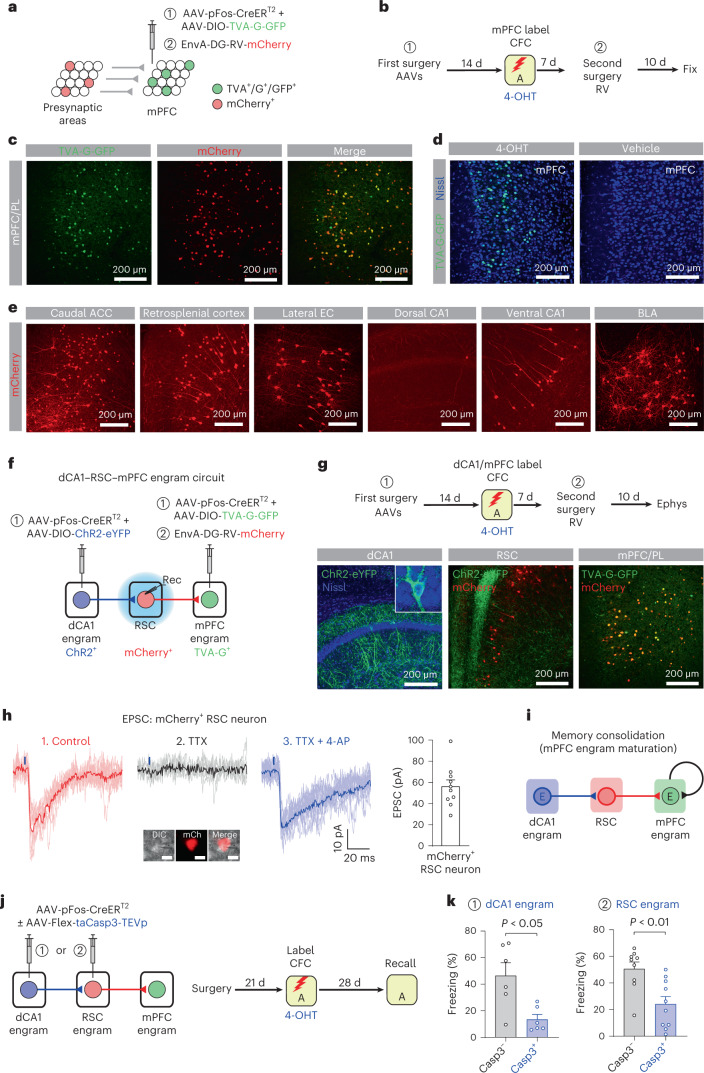

mPFC–BLA engram circuits for remote fear memory recall

A previous study suggests the critical role of the mPFC–BLA pathway in the recall of remote contextual fear memories12. Consistent with this, we found that 17.5 ± 1.3% of mPFC neurons projecting to the BLA were activated during remote fear memory recall, while 6.6 ± 1.0% of mPFC neurons active during memory recall projected to the BLA (mean ± s.e.m., five mice; Extended Data Fig. 9a–c). Moreover, silencing of mPFC neurons projecting to the BLA prevented the recall of remote but not recent contextual fear memory30 (Extended Data Fig. 9d–g), suggesting that activity in the mPFC–BLA pathway is required for remote fear memory recall.

Extended Data Fig. 9. BLA−mPFC circuit was involved in remote fear memory recall, and mPFC−BLA engram circuit was strengthened during systems consolidation.

(a) Experimental setup for (b, c). mPFC neurons projecting to BLA (BLA projectors) expressed tdTomato (tdT), while mPFC recall neurons were immunostained for c-Fos. (b) Images show tdT+ or Fos+ mPFC/PL neurons. Both tdT+ and Fos+ neurons are circled. (c) Left: proportion of mPFC recall neurons among BLA projectors (5 mice). Right: proportion of BLA projectors among mPFC recall neurons (5 mice). Dotted lines indicate the chance that randomly selected cells were Fos+ (left) or tdT+ (right). (d) Left: experimental setup for (e–g). BLA projectors in bilateral mPFC expressed PSAM4-GlyR-eGFP or eYFP. Right: image showing PSAM4-GlyR-eGFP-labeled mPFC neurons (green). (e) Left: AP firings before and after μPSEM application (10 μM) in the same PSAM4-GlyR-eGFP-expressing mPFC neuron (scale bar, 10 μm). Right: summary plot of AP firing (3 neurons). (f) Left: 28 days after CFC, mice were tested for memory recall after μPSEM injection. Right: freezing behavior during remote memory recall in PSAM4 (9 mice) and eYFP groups (11 mice). Unpaired t-test. (g) Left: a day after CFC, mice were tested for memory recall after μPSEM injection. Right: freezing behavior in PSAM4 (8 mice) and eYFP groups (6 mice). Unpaired t-test. (h) Experimental setup for (i–k). Photostimulation activated ChR2+ mPFC engram inputs and induced EPSCs in tdT− nonengram and tdT+ engram BLA neurons. (i) Electrophysiological experiments were 7 or 28 days after CFC without memory recall test. (j, k) Left: EPSCs in mPFC engram inputs to tdT− and tdT+ BLA neurons were recorded 28 days (j) or 7 days after CFC (k). Right: AMPA/NMDA EPSC ratio in tdT− and tdT+ BLA neurons (12 pairs in (j) and 16 pairs in (k), paired t-test). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

We next examined how mPFC engram could activate BLA engram to induce remote fear memory recall31. mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP, and BLA engram neurons expressed tdT (Fig. 7a–c). Four weeks after CFC, photostimulation of ChR2+ mPFC engram inputs induced EPSCs in tdT+ BLA neurons (Fig. 7d), indicating that mPFC engram neurons monosynaptically projected to BLA engram neurons. Moreover, both AMPAR EPSC amplitude and the AMPA/NMDA ratio were substantially larger in tdT+ BLA neurons than in tdT– neurons (Fig. 7d,e), suggesting stronger connections of mPFC engram inputs to BLA engram neurons than those inputs to nonengram neurons. The strengthening of the mPFC–BLA engram circuit was also observed without memory recall before recording, indicating that it was not induced by memory recall (Extended Data Fig. 9h–j). Moreover, synapse-specific strengthening of the mPFC–BLA engram circuit was not detected 7 d after CFC, suggesting that the engram circuit was progressively strengthened during systems consolidation (Extended Data Fig. 9k). With these synaptic changes, mPFC engram neurons can efficiently reactivate BLA engram neurons during remote fear memory recall.

Fig. 7. mPFC engram neurons were connected to BLA engram neurons through direct and indirect pathways for remote fear memory recall.

a, Experimental setup for b–e. Photostimulation activated mPFC engram inputs and induced EPSCs in tdT− nonengram and tdT+ engram BLA neurons. b, Mice were tested for memory recall 28 d after CFC. c, Left: freezing behavior during memory recall (eight mice). Middle: image showing ChR2-eYFP+/tdT+ mPFC neurons (squares). Right: image showing ChR2-eYFP+ mPFC axons (green) and tdT+ BLA neurons (red). d, Traces of EPSCs induced by photostimulation of mPFC engram inputs and recorded in tdT− and tdT+ BLA neurons. AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs were recorded as in Fig. 2d. Scale bar, 10 μm. e, Left: comparison of EPSCAMPAR in 20 pairs of tdT– versus tdT+ BLA neurons. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA. Right: comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratios of EPSCs in tdT− (19 cells) versus tdT+ BLA neurons (20 cells). Unpaired t-test. f, Experimental setup for g–j. mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP, whereas BLA engram neurons expressed TVA-G-GFP. mPFC relay neurons (R, red) were labeled with mCherry. Photostimulation activated ChR2+ mPFC engram inputs and induced EPSCs in mPFC relay neurons. g, After AAV injection, mice underwent CFC and received RV injection. h, Left: freezing behavior during memory recall (six mice). Middle: BLA engram neurons were labeled with TVA-G-GFP and/or mCherry. TVA-G-GFP+/mCherry+ neurons are circled. Right: image showing mCherry+ mPFC relay neurons. i, Left: EPSCs were induced by photostimulation of mPFC engram inputs and recorded in mCherry+ mPFC relay neurons (red). TTX blocked EPSCs (black), which were rescued by 4-AP (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. Right: comparison of EPSC amplitude in mCherry+ versus mCherry− mPFC neurons (11 pairs) in the presence of TTX, 4-AP and SR-95531. j, Photostimulation (blue) of mPFC engram inputs induced AP firings (red) in mCherry+ mPFC relay neurons in cell-attached mode in the presence of SR-95531. k, mPFC engram neurons project to BLA engram neurons monosynaptically (1) or are connected to BLA engram neurons through mPFC relay neurons (2). Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

As only a small fraction of mPFC engram neurons projected to the BLA (Extended Data Fig. 1g,h), we examined whether mPFC engram might indirectly activate BLA engram by recruiting mPFC neurons projecting to BLA engram neurons, which we termed ‘mPFC relay neurons’. We labeled mPFC relay neurons with mCherry using RV-mediated trans-synaptic tracing, while mPFC engram neurons expressed ChR2-eYFP (Fig. 7f–h). Photostimulation of ChR2+ mPFC engram neurons induced monosynaptic EPSCs and action potential firings in 88% and 40% of mPFC relay neurons examined, respectively (33 and 20 cells examined, respectively, Fig. 7i–j). Although mPFC relay neurons did not receive stronger mPFC engram inputs than other mPFC neurons (Fig. 7i), these results indicate that mPFC engram neurons can activate BLA engram neurons through mPFC relay neurons and contribute to remote fear memory recall (Fig. 7k).

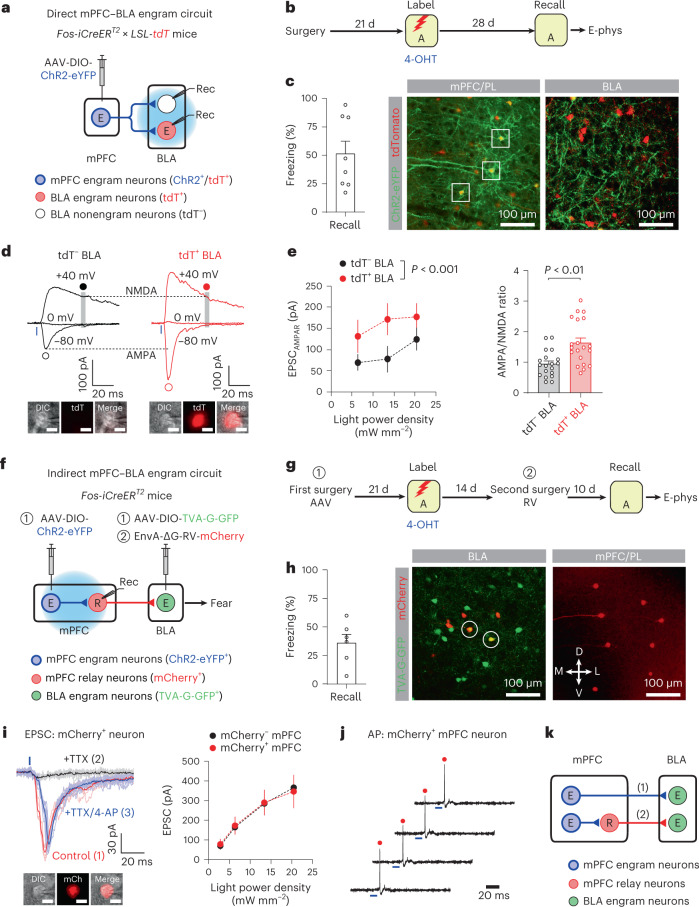

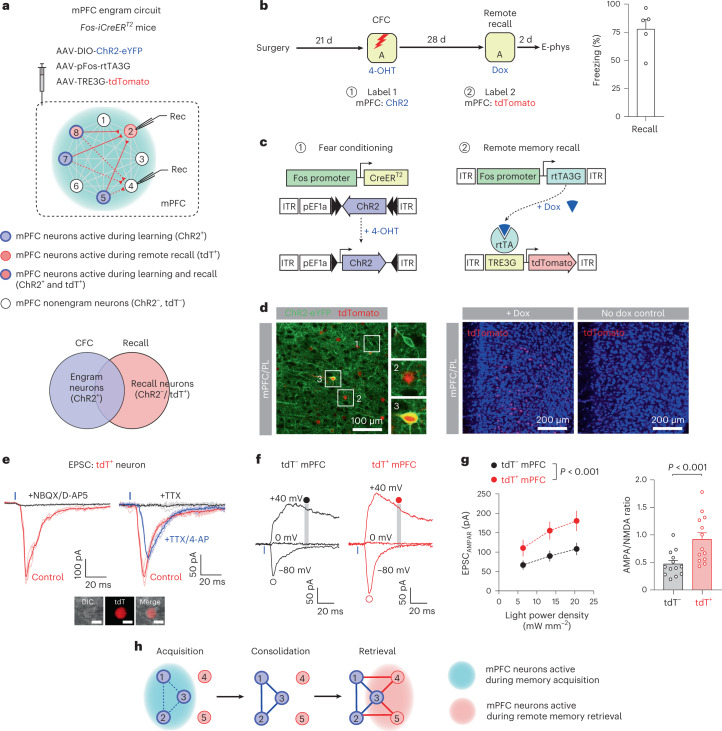

Strong connections between mPFC engram and recall neurons

While a substantial proportion (~30%) of mPFC engram neurons were reactivated during remote memory recall, other mPFC neurons were also recruited during memory recall (Fig. 1d). During remote memory recall, reactivated mPFC engram neurons may recruit other mPFC neurons that were not active during CFC, which termed ‘mPFC recall neurons’. To test this, we examined whether mPFC engram neurons were monosynaptically connected to mPFC recall neurons. Using dual independent labeling2, we independently labeled mPFC neurons active during CFC and those recruited during remote memory recall. After CFC and 4-OHT injection, mPFC engram neurons active during CFC expressed ChR2-eYFP (Fig. 8a–d). After 4 weeks, the mice received doxycycline (Dox) injection and were tested for remote memory recall, resulting in tdT expression in mPFC neurons active during recall (Fig. 8b–d). Thus, ChR2+ neurons represent mPFC engram neurons, whereas tdT+/ChR2– neurons were mPFC recall neurons. Photostimulation of ChR2+ engram inputs induced glutamatergic and monosynaptic EPSCs in tdT+/ChR2– mPFC neurons (Fig. 8e), indicating that mPFC recall neurons received excitatory inputs of mPFC engram neurons. Moreover, both AMPAR EPSCs and the AMPA/NMDA ratio were substantially larger in tdT+/ChR2– mPFC neurons than in tdT–/ChR2– neurons (Fig. 8f,g), indicating that mPFC recall neurons received stronger mPFC engram inputs than other neurons did. Thus, during remote memory recall, reactivated mPFC engram neurons can efficiently recruit mPFC recall neurons (Fig. 8h). Consistent with this, silencing of mPFC neurons active during remote but not recent memory recall inhibited subsequent remote memory recall (Extended Data Fig. 10).

Fig. 8. mPFC neurons active during initial learning were strongly connected to mPFC neurons recruited during remote memory recall.

a, Experimental setup. mPFC engram neurons active during CFC expressed ChR2-eYFP (blue). mPFC recall neurons active during remote memory recall expressed tdT (red). b, Left: mice received 4-OHT injection after CFC (label 1). After 28 d, they received Dox injection and were tested for memory recall (label 2). Right: freezing behavior during remote memory recall (five mice). c, Left: mPFC neurons active during CFC expressed iCreERT2, resulting in 4-OHT-dependent recombination and ChR2 expression. Right: mPFC neurons active during remote memory recall expressed rtTA3G, resulting in tdT expression in the presence of Dox. d, Left: images showing mPFC neurons expressing ChR2-eYFP (green, 1), tdT (red, 2) or both (3). Right: mPFC recall neurons expressed tdT in Dox-injected mice. e, Traces of EPSCs induced by photostimulation of ChR2+ axons and recorded in tdT+/ChR2− mPFC neurons (red) at −80 mV. Left: EPSCs were inhibited by NBQX and D-AP5 (black). Right: TTX blocked EPSCs (black), which were rescued by 4-AP (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. f, Traces of EPSCs induced by photostimulation and recorded in tdT–/ChR2– mPFC neuron (black) and tdT+/ChR2− mPFC recall neurons (red). AMPAR EPSCs and NMDAR EPSCs were recorded as in Fig. 2d. TTX and 4-AP were added to isolate monosynaptic EPSCs. g, Left: comparison of the amplitude of EPSCAMPAR recorded in tdT–/ChR2– versus tdT+/ChR2– neurons (15 pairs). Repeated measures two-way ANOVA. Right: comparison of AMPA/NMDA ratio between tdT–/ChR2– versus tdT+/ChR2– neurons (13 pairs). Paired t-test. h, Left: some mPFC neurons (neurons 1–3) are recruited during learning (memory acquisition). These engram neurons are weakly connected to one another. Middle: excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons are strengthened during systems consolidation (blue lines). Right: remote memory recall reactivates some mPFC engram neurons (neuron 3), while it also activates mPFC recall neurons (neurons 4 and 5), which receive stronger inputs of mPFC engram neurons (red lines) than other mPFC neurons. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Details of the statistical analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Remote memory recall was inhibited by chemogenetic silencing of mPFC neurons active during remote but not recent memory recall.

(a) Experimental setup. A mixture of AAV-pFos-CreERT2 and AAV-DIO- hM4Di-mCherry (hM4Di group) or AAV-DIO-mCherry (mCherry group) was bilaterally injected to the mPFC. mPFC neurons active during memory recall expressed hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry. (b) Image showing mPFC neurons expressing hM4Di-mCherry (red). Blue fluorescence indicates Nissl stain. (c) Four weeks after CFC, the mice receive a tamoxifen injection (Tam) to label mPFC neurons active during remote memory recall (recall 1) with hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry. A week after the recall 1 session, the mice received a CNO injection and were tested for memory recall in the same context (recall 2). (d) Summary plots showing the average freezing time during recall 1 and recall 2 sessions in the hM4Di (7 mice) and mCherry groups (8 mice). Repeated measures two-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons. (e) Two days after CFC, the mice receive a tamoxifen injection to label mPFC neurons active during recent memory recall (recall 1) with hM4Di-mCherry or mCherry. Four weeks after recall 1 session, the mice received a CNO injection and were tested for remote memory recall in the same context (recall 2). (f) Summary plots showing the average freezing time during recall 1 and recall 2 sessions in the hM4Di (10 mice) and mCherry groups (9 mice). Repeated measures two-way ANOVA with post hoc comparisons. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Once acquired, contextual memories gradually mature to a stabilized form in the neocortex3. After systems consolidation, the retrieval of remote contextual memories requires neocortical activity and depends less on hippocampal activity8,11,32–34 (but see also refs. 35,36) as the standard consolidation model proposes. During systems consolidation, mPFC engram neurons slowly undergo enduring neuronal and synaptic changes for long-term memory storage. Although a previous study suggests that dendritic spine density is globally increased in mPFC engram neurons after systems consolidation12, synapse-specific substrates of remote contextual memories have not been identified. In this study, we demonstrate that the long-term storage of remote contextual memories involves progressive and synapse-specific strengthening of excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons.

Previous studies suggest that learning rapidly generates neocortical memory engram37,38. Using activity-dependent labeling39, we tagged mPFC neurons recruited during CFC, which were more readily reactivated during remote memory recall than other mPFC neurons. Consistent with previous reports10,12, optogenetic activation of mPFC neurons active during CFC induced memory recall, suggesting that mPFC engram is generated early during learning. However, another study suggests that mPFC engram is more dynamic and continues to evolve after learning40.

Previous studies implicated neocortical synaptic plasticity in remote memory consolidation41–43. A subset of new dendritic spines induced by learning is preserved in neocortical neurons throughout life, supporting enduring memories44. Consistent with this, our study suggests that remote memory consolidation correlates with the strengthening of mPFC engram circuits. When examined 28 d after CFC, both interhemispheric and local excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons displayed higher synaptic efficacy than those between engram and nonengram neurons or those between nonengram neurons, suggesting synapse-specific strengthening of mPFC engram circuits during systems consolidation. The strengthening of the engram circuit was also observed in the ACC but not in the RSC, although both areas are involved in remote memory consolidation9,20. The extent of BLA inputs conveying US signals during CFC may determine which neocortical area undergoes enduring synaptic changes during systems consolidation.

The strengthening of mPFC engram circuits was not detected 7 d after CFC, indicating that the engram circuits were progressively strengthened during systems consolidation. Moreover, silencing of mPFC engram neurons inhibited the retrieval of remote but not recent contextual memory, consistent with previous reports10,12. Progressive strengthening of mPFC engram circuits may account for the time-dependent role of mPFC engram in contextual memory recall. Moreover, the inhibition of CREB in mPFC engram neurons inhibited remote memory recall10. As the same manipulation also prevented the strengthening of mPFC engram circuit, neuronal and/or synaptic plasticity in mPFC engram neurons is likely involved in remote memory consolidation. The extinction of remote contextual memories weakened mPFC engram circuit, further supporting the correlation between remote memory recall performance and synaptic strength of mPFC engram circuit. As mPFC engram neurons are crucial for remote memory recall, the weakening of mPFC engram circuit after extinction can inhibit the retrieval of remote contextual memory. Our finding that the original engram is modified by extinction learning is consistent with previous reports45,46.

Our study highlights the role of sustained hippocampal activity in mPFC engram maturation. As mPFC activity is modulated during hippocampal sharp-wave ripples47, hippocampal signals can be conveyed to the mPFC, facilitating hippocampal–neocortical interactions during sleep for memory consolidation48. Consistent with this, both the hippocampus and mPFC show the replay of activity patterns representing memories during sleep49,50. In our study, ablation of DG engram neurons inhibited both remote memory recall and the reactivation of mPFC and BLA engram during recall. These findings suggest that sustained activity of DG engram may contribute to remote memory consolidation by facilitating mPFC engram maturation. Notably, the ablation of DG engram neurons also prevented the strengthening of mPFC engram circuits. Our study also demonstrates that RSC neurons projecting to mPFC engram neurons receive monosynaptic inputs from dCA1 engram neurons, forming the dorsal hippocampal–RSC–mPFC engram circuit. Moreover, the ablation of dCA1 or RSC engram neurons inhibited remote memory recall. Thus, the RSC can convey hippocampal signals to mPFC engram for systems consolidation. Consistent with this, a previous study suggests that the stimulation of RSC engram neurons facilitated systems consolidation by modulating mPFC activity20, highlighting the role of the RSC in remote memory consolidation.

Then, how does the strengthening of mPFC engram circuits contribute to the consolidation and retrieval of remote contextual memories? Although the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) is necessary for mPFC engram generation, activity in the MEC–mPFC pathway is not required for remote memory recall12. As mPFC engram generated by the MEC is reactivated by distinct inputs during remote memory recall, these inputs likely activate only a fraction of mPFC engram neurons. In our study, excitatory connections between mPFC engram neurons were strengthened during remote memory consolidation, while mPFC engram neurons received weaker inhibitory engram inputs than other mPFC neurons. These synaptic mechanisms can facilitate the reactivation of mPFC engram during remote memory recall, even if only a fraction of mPFC engram neurons are directly reactivated by extrinsic inputs. This is analogous to the role of the strengthening of recurrent hippocampal CA3–CA3 synapses in pattern completion51,52. Moreover, the strengthening of mPFC engram circuits can also promote synchronized activity of mPFC engram neurons for remote memory recall53,54.

In our study, some mPFC neurons projecting to the BLA were reactivated by remote memory recall, and their silencing inhibited remote but not recent memory recall, indicating that the mPFC–BLA pathway is necessary for the recall of remote contextual fear memories12. Our results also suggest that mPFC engram neurons are connected to BLA engram neurons through monosynaptic and disynaptic pathways. Moreover, mPFC engram neurons were more strongly connected to BLA engram neurons than to BLA nonengram neurons when examined 28 d but not 7 d after CFC. With this strong connectivity, mPFC engram can efficiently activate BLA engram to generate defensive behaviors in a threat-predictive context during remote fear memory recall. Synapse-specific strengthening of the mPFC–BLA engram circuit may support the development of a schematic memory with few contextual details in extrahippocampal areas as the transformation theory proposes13,14.

While a subset of mPFC engram neurons was reactivated during remote memory recall, other mPFC neurons that were not active during initial learning were also recruited during remote memory recall. These mPFC recall neurons received stronger excitatory inputs of mPFC engram neurons than other mPFC neurons. Thus, mPFC engram neurons reactivated during memory recall can efficiently recruit mPFC recall neurons, contributing to remote memory recall. Consistent with this, silencing of mPFC neurons recruited during remote but not recent memory recall inhibited subsequent memory retrieval, highlighting the role of mPFC recall neurons in remote memory recall. Thus, the retrieval of remote contextual fear memory can be suppressed by inhibiting a subset of mPFC neurons tagged even after the contextual memory is consolidated in neocortical circuits, suggesting clinical implications in attenuating chronic maladaptive fear memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Together, our study elucidates fundamental mechanisms by which remote contextual memories are consolidated in the neocortex.

Methods

Subjects

We obtained heterozygous Fos-iCreERT2 (TRAP2) mice by crossing wild-type C57BL6/J (Jackson Laboratory Stock, 000664) and Fos-iCreERT2(+/+) mice (Jackson Laboratory Stock, 030323). We obtained Fos-iCreERT2(+/−) × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato(+/−) mice by crossing Fos-iCreERT2(+/+) and Ai14 ROSA-LSL-tdTomato(+/+) mice (Jackson Laboratory Stock, 007914). The mice were housed in home cages on a 12-h light/dark cycle at 23–25 °C with food and water continuously available. Humidity range was 30–70%. The light cycle was from 8 AM to 8 PM. Eight- to 12-week-old mice of both sexes were used for experiments. All of the animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Riverside.

Virus constructs

The recombinant adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) were packaged by Addgene, Vectorbuilder, the Vector Core at the University of North Carolina (UNC). The AAV titers were 1.7–3.0 × 1013 genome copies (GC) ml–1 for AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP (Addgene, 20298-AAV5), 0.9 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-eYFP (UNC), 0.9 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-mGFP-MutCREB(S133A) (Vectorbuilder; Addgene plasmid,194642), 2.8–5.5 × 1011 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pFos-CreERT2 (Vectorbuilder; Addgene plasmid,194643), 4.6 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pEF1α-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp (UNC), 3.9–5.9 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV1-pSyn-DIO-TVA-G-GFP (UNC), 5.9 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pFos-rtTA3G (Vectorbuilder; Addgene plasmid,120309), and 5.0 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-TRE3G-tdTomato (Vectorbuilder; Addgene plasmid,194644), 4.3 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pCaMKII-eYFP (UNC), 3.8 × 1012 GC ml–1 for rg AAV2-pCAG-tdTomato (UNC), 5.0 × 1010 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pCaMKII-Cre-GFP (UNC), 2.4–3.1 × 1013 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pSyn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry (Addgene,44362-AAV5), 1.0 × 1012 GC ml–1 for AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-mCherry (UNC), 2.5 × 1013 for AAV5-pSyn-DIO-PSAM4-GlyR-eGFP (Addgene,119741-AAV5), and 4.1 × 1012 GC ml–1 for rg AAV2-pCAG-Cre (UNC). RV (EnvA-ΔG-RV-mCherry) was obtained from the gene transfer, targeting and therapeutics core of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and the titer was 1.5–2.7 × 108 transducing units per milliliter.

Surgery

Before surgery, general anesthesia was induced by placing the mice in a transparent anesthetic chamber filled with 5% isoflurane. The anesthesia was maintained during surgery with 1.5% isoflurane applied to the nostrils of the mice using a precision vaporizer. Mice were checked for the absence of the tail-pinch reflex as a sign of sufficient anesthesia. The mice were then immobilized in a stereotaxic frame with nonrupture ear bars (David Kopf Instruments), and ophthalmic ointment was applied to prevent eye drying. After an incision was made along the midline of the scalp, unilateral or bilateral craniotomies were performed using a microdrill with 0.5 mm burrs. The tips of glass capillaries loaded with virus-containing solution were placed into the prelimbic division of the mPFC (mPFC/PL) (1.9 mm rostral to bregma, 0.4 mm lateral to the midline and 1.2 mm ventral to the pial surface), cACC (0.5 mm rostral to bregma, 0.4 mm lateral to the midline and 0.9 mm ventral to the pial surface), RSC (2.2 mm caudal to bregma, 0.5 mm lateral to the midline and 0.6 mm ventral to the pial surface), BLA (1.5 mm caudal to bregma, 3.3 mm lateral to the midline and 3.4 ventral to the pial surface), DG (2.0 mm caudal to bregma, 1.1 mm lateral to the midline and 2.0 mm ventral to the pial surface) or dCA1 (2.0 mm caudal to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the midline and 1.2 mm ventral to the pial surface). Virus-containing solution was injected at a rate of 0.1 μl min−1 using a 10 μl Hamilton microsyringe and a syringe pump.

The total volume of injected virus-containing solution was 1.0 μl for AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP, 0.3–1.0 μl for AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-eYFP, 1.0 μl for AAV-pEF1α-DIO-mGFP-MutCREB(S133A), 0.5–1.0 μl for AAV1-pSyn-DIO-TVA-G-GFP, 0.5 μl for AAV5-pCaMKII-GFP and 1.0 μl for rg AAV2-pCAG-tdTomato. In Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 8a–c, a mixture of AAV5-pFos-CreERT2 (0.25 μl) and AAV5-pEF1α-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp (0.25 μl) was bilaterally injected into the dorsal DG. In Fig. 6a–h, a mixture of AAV5-pFos-CreERT2 (0.5 μl) and AAV1-pSyn-DIO-TVA-G-GFP (0.5 μl) into the mPFC/PL during the first virus injection surgery. In Fig. 6f–h, a mixture of AAV5-pFos-CreERT2 (0.5 μl) and AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP (0.5 μl) was also injected into the dorsal CA1 during the first virus injection surgery. In Fig. 6j,k and Extended Data Fig. 8h,i, a mixture of AAV5-pFos-CreERT2 (0.25 μl) and AAV5-pEF1α-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp (0.25 μl) was bilaterally injected into the dCA1 or RSC. In Fig. 8, a mixture of AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP (0.33 μl), AAV5-pFos-rtTA3G (0.33 μl) and AAV5-TRE3G-tdTomato (0.33 μl) was injected into the mPFC/PL. In Extended Data Fig. 4, a mixture of AAV5-pEF1α-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-eYFP (0.4 μl) and AAV5-pCaMKII-Cre-GFP (0.2 μl) was injected into the mPFC/PL. In Extended Data Fig. 8d–g, a mixture of AAV5-pFos-CreERT2 (0.25 μl) and AAV5-pEF1α-Flex-taCasp3-TEVp (0.25 μl) was bilaterally injected into the dCA1. After injection, the capillary was left in place for an additional 5 min to allow diffusion of the virus solution and then withdrawn. The scalp incision was closed with surgical sutures, and the mice were given a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine-containing saline (1 ml, 0.12 mg buprenorphine per kilogram body weight) for postoperative analgesia and hydration.

For the experiments described in Fig. 1h–l, AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP (ChR2 group) or AAV-DIO-eYFP (eYFP group) was bilaterally injected into the mPFC/PL in Fos-iCreERT2 mice, and a dual fiberoptic cannula (200 μm in diameter, numerical aperture of 0.53; Doric Lenses, DFC_200/245-0.53_3mm_DF0.9_FLT) was implanted dorsal to the mPFC/PL (1.7 mm rostral to bregma and 0.8 mm ventral to the pial surface) and secured with dental cement. To minimize light leakage during photostimulation, which can act as a visual cue, we painted all optical pathways, including the dental cement securing the cannula, with black nail polish. We verified the cannula implantation site in each animal.

Contextual fear conditioning

Mice were singly housed in their HCs a day before CFC. On the training day, mice were placed in Context A (dimension, 30 cm × 24 cm × 21 cm; stainless steel grid floor, white acrylic flat wall with black vertical stripes, white light illumination and benzaldehyde odor) within a fear conditioning chamber (Med Associates) between 9:30 AM and 10:30 AM. After 3 min, the mice received the first US (electric footshock, 0.5 mA, 2 s duration) and were given four more US with a 2-min interval except in Fig. 3e,f, in which the mice received total of two USs for CFC. The temperature in the fear conditioning chamber was 23–25 °C. One day after CFC, the mice were group-housed until 2 d before remote memory recall test. For the recall of contextual fear memories, the mice were exposed to Context A for 5 min between 9:30 AM and 10:30 AM after 1 min of acclimatization in Context A. Freezing behavior was quantified as the percentage of time immobile. Immobility for more than 2 s was counted as freezing behavior. The movement of the mice in the fear conditioning chamber was recorded using a near-infrared camera and analyzed with EthoVision XT 11 software (Noldus). In Extended Data Fig. 1a,b, some mice were trained and tested for freezing behavior in Context B (dimension, 30 cm × 24 cm × 21 cm; stainless steel grid floor, white acrylic curved wall with black horizontal stripes, white illumination and acetic acid odor).

Extinction training

In Fig. 3g–j, the mice underwent memory extinction training 28 d after CFC and were exposed to Context A for 6 min once a day for 5 d (days 1–5). For each extinction training session, freezing behavior was quantified as the percentage of time immobile in Context A after 1 min of acclimatization. Electrophysiological recordings were performed within 1 h after the last (fifth) session of the extinction training on day 5.

Activity-dependent neuronal labeling

To label neurons active during CFC, we fear conditioned Fos-iCreERT2 mice, Fos-iCreERT2 × ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice or ROSA-LSL-tdTomato mice 2–3 weeks after virus injection surgery as described above. In some experiments (Figs. 5 and 6 and Extended Data Figs. 3, 8 and 10), we injected AAV-pFos-CreERT2 into the mPFC, DG, dCA1 or RSC to increase labeling efficiency. To open labeling window, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 4-OHT (H6278, Sigma-Aldrich; 50–75 mg kg–1 of body weight) under brief anesthesia with 5% isoflurane in the anesthesia chamber 10 min after CFC. 4-OHT was dissolved in DMSO (40 mg ml–1) and further dissolved in saline containing 2% TWEEN 80 in a water bath at 40–42 °C, resulting in 1 mg ml–1 4-OHT solution. To minimize neuronal labeling by background noise, mice were kept in their HCs in a quiet place for 8 h before and after 4-OHT injection.

To independently labeled mPFC neurons active during CFC and those recruited during remote memory recall in Fig. 8, we injected a mixture of AAV-DIO-ChR2-eYFP (0.33 μl), AAV-pFos-rtTA3G (0.33 μl) and AAV-TRE3G-tdTomato (0.33 μl) into the mPFC/PL in Fos-iCreERT2 mice. After CFC, the mice received a 4-OHT injection (50 mg kg–1 of body weight) to label mPFC engram neurons with ChR2-eYFP. Four weeks after CFC, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of doxycycline hyclate (Dox; D9891, Sigma-Aldrich; 50–100 mg kg–1 of body weight) dissolved in saline at 5 mg ml–1 under brief anesthesia with 5% isoflurane and returned to the HCs. One hour after Dox injection, the mice were exposed to Context A for the recall of remote fear memories for 5 min.

In Extended Data Fig. 10, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of tamoxifen (100 mg kg–1 of body weight, Sigma-Aldrich, T5648). Tamoxifen was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich, C8267) at 20 mg ml–1 with nutation for 6 h in the dark at room temperature (23–25 °C). Sixteen hours after tamoxifen injection, the mice were tested for the recall of recent or remote contextual fear memory in Context A for 2 min.

In vivo optogenetic stimulation of mPFC engram neurons