Abstract

Aging is a major risk factor for many human diseases, including cognitive impairment, which affects a large population of the elderly. In the past few decades, our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the changes associated with aging and age-related diseases has expanded greatly, shedding light on the potential role of these changes in cognitive impairment. In this article, we review recent advances in understanding of the mechanisms underlying brain aging under normal and pathological conditions, compare their similarities and differences, discuss the causative and adaptive mechanisms of brain aging, and finally attempt to find some rules to guide us on how to promote healthy aging and prevent age-related diseases.

Keywords: Healthy aging, Pathological aging, Cognitive impairment

Introduction

As we age, our bodies undergo many changes [1–3] that can be physiological and pathological. Just like other organs, the brain is susceptible to aging and it undergoes a series of structural and functional changes during aging [2, 4]. In the context of brain biology aging is a major risk factor for developing cognitive impairment like Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common dementia that affects ~55 million people worldwide and 15 million in China [5]. Thus, the development of new drugs or treatments to prevent or reverse cognitive impairment requires a comprehensive understanding of the biological events associated with the aging process in the brain.

In the past decades, our understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying the modulation of aging has been greatly expanded. Most remarkably, several signaling pathways have been identified as key aging modulators in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans), flies, and mammals, suggesting that the biology of aging is conserved across species and the rate of aging is plastic [6, 7]. Nine common age-related molecular and cellular alterations have been proposed as hallmarks of aging [3]. Most of these hallmarks occur in aging neurons, except for cellular senescence and telomere attrition (both of which usually occur in proliferative peripheral tissues), which remain to be established [8]. A myriad of evidence has implied that these hallmarks also occur in pathological aging brains at a more severe level [9]. However, although brain atrophy and cognitive decline appear both in normal and pathological aging brains, the mechanisms underlying these phenomena are not exactly the same. Cognitive decline in normal aging is attributed to the disruption of circuits and synapses, without significant neuron loss, and this is in contrast to AD and related dementias, which are associated with extensive neuronal death [10, 11].

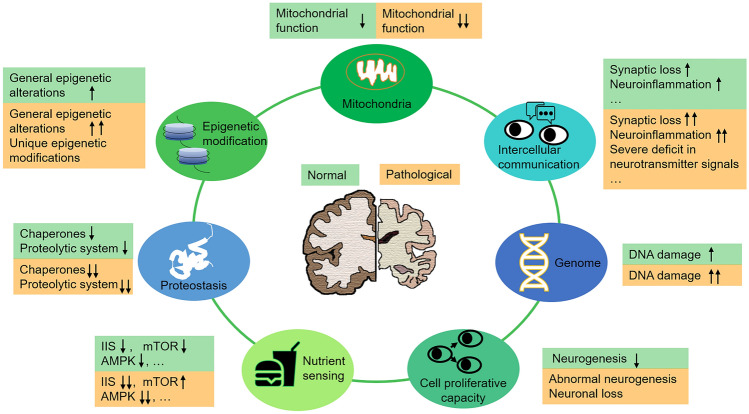

In this review, we mainly focus on several molecular and cellular events (genomic instability, epigenetic alteration, mitochondrial dysfunction, deregulated nutrient sensing, altered cell proliferative capacity, altered intercellular communication, and loss of proteostasis; Fig. 1) to review the mechanisms of normal aging and how those processes interface with pathological aging of the brain.

Fig. 1.

Molecular and cellular events occur in aging brains under normal and pathological conditions. Molecular and cellular alterations in genomic stability, mitochondrial function, nutrient sensing, epigenetic modification, cell proliferative capacity, intercellular communication, and proteostasis can be similar or different in aging brains under normal and pathological conditions.

Genomic Instability

One common feature of aging is the accumulation of genetic damage throughout life [12]. Genomic DNA is regularly damaged by radiation, reactive oxygen species (ROS), DNA replication errors, and other exogenous or endogenous threats, and damaged DNAs are progressively accumulated during the normal course of aging. Such accumulation is more serious in aging neurons because excitatory synaptic activity produces more ROS, causing more DNA damage. Furthermore, neurons are post-mitotic cells and can not repair double-strand breaks by the more accurate homologous recombination pathway. Indeed, analyses of tissue samples from human and rodent brains have revealed that the amount of damaged nuclear and mitochondrial DNA increases and the capacity for DNA repair decreases during aging [8]. In the cortex of the aging human brain, promoter regions of a considerable proportion of genes are damaged, resulting in reduction of expression of a subset of genes associated with synaptic plasticity, mitochondrial function, and neuronal survival [13]. Interestingly, a similar pattern of DNA damage in vulnerable genes has also been found in C. elegans, Drosophila, and mouse [14–17], suggesting that selective DNA damage to gene promoter sequences is a conserved mechanism underlying age-related cognitive impairment.

Compared with the moderate DNA damage occurring in normal aging brains, the damage to genomic DNA in aging brains under pathological conditions is much more severe. Studies have shown that in human brains with AD, the genomic DNA is evidently disrupted, and the extensive DNA damage may eventually lead to the death of a large number of neurons [18]. Aggregated β-amyloid peptide (Aβ), a major pathological hallmark of AD, worsens the DNA damage by inducing aberrant synaptic activity, which elicits more ROS [19]. Similarly, enhanced oxidative DNA lesions and damage to mitochondrial DNA have been reported in the neurons of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson disease (PD) patients, respectively [20–22].

Genomic instability is a key cause of age-related cognitive impairment. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that impairment of DNA repair is sufficient to accelerate aging phenotypes and induce neurodegeneration [23]. Central dogma states that DNA transfers genetic information to RNA and produces functional proteins. Thus, DNA damage eventually affects the function of proteins, and therefore accumulation of DNA damage is a likely major cause of chronic systemic failures, which are further worsened under pathological conditions. This inevitably confers insults on the aging brain, consequently impairing cognitive function, and may drive the onset or progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondrial impairment has been regarded as one of the hallmarks of aging [3]. Neurons are more susceptible to mitochondrial impairment as they need high energy to be functional. In the aging brain, mitochondria exhibit a myriad of structural and functional changes, including morphological enlargement or fragmentation, membrane depolarization, an impaired electron transport chain, and increased oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) [3, 24]. The molecular mechanism underlying age-related dysfunction of mitochondria remains controversial. It has been suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction is due to the gradual accumulation of somatic mtDNA mutations. However, this hypothesis has been challenged by the fact that a cell has multiple mitochondrial genomes, which can tolerate the coexistence of wild-type and some mutant genomes [25]. Clearly, dysfunction of the mitochondrion is at least partially attributable to the age-related decline in the expression of mitochondrial proteins [13]. A recent study provides evidence that epigenetic changes contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction in the aging brain. The age-related upregulation of bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain 2B (BAZ2B) and euchromatic histone lysine methyltransferase 1 (EHMT1) underlie the down-regulation of genes involving core metabolism (mainly ribosome and oxidative phosphorylation), which have been consistently reported in patients with AD and mild cognitive impairment [26].

Pathological aging brains show more severe dysfunction of mitochondria. Many lines of evidence have suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a central role in the onset and development of neurodegenerative diseases. The age-related reductions in oxidative phosphorylation and accumulation of mtDNA damage are aggravated in the brains of AD patients [27–29]. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and fission–fusion balance, as well as decreased mitophagy, have also been reported in AD patients’ brains [30, 31]. When it comes to the relationship between mitochondria and pathological brain aging, PD should not be ignored [32, 33]. Although the exact cause of the disease is not clear, aberrant mitochondrial clearance by autophagy is a major factor in the death of dopaminergic neurons. The protein kinase PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) accumulates on the outer membrane of the mitochondria, and then phosphorylates and activates the E3 ligase activity of Parkin, which ubiquitinates outer mitochondrial membrane proteins to trigger selective autophagy [34]. Healthy neurons effectively remove damaged mitochondria through mitochondrial phagocytosis; while in PD neurons, excessive mitochondrial damage causes a failure in the clearance of damaged mitochondria, resulting in extensive neuronal death.

Mitochondria establish and maintain the aging rate of the entire organism [24], but the effect of mitochondrial damage on the aging phenotypes is not simply linear. Previously, it was supposed that an energetic crisis in aging brains caused by accumulating damaged mitochondria accelerates functional deterioration and triggers neurodegenerative diseases. However, recent genetic and pharmacological evidence has discovered that, although severe mitochondrial dysfunction may cause cell death, mild respiratory defects extend the lifespan. Down-regulating the function of the electron transport chain in neurons has been reported to extend the lifespan of C. elegans [24]. On the other hand, several reports have demonstrated that caloric restriction, genetic/pharmacological restoration of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), or manipulation of a glia-neuron signal can increase mitochondrial function and activation of the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) to mitigate many of the detrimental effects of aging and/or prolong the healthspan [35–39]. Perhaps maintaining mitochondrial function at the proper level, not too low or too high, is most beneficial for promoting healthy aging.

Deregulated Nutrient Sensing

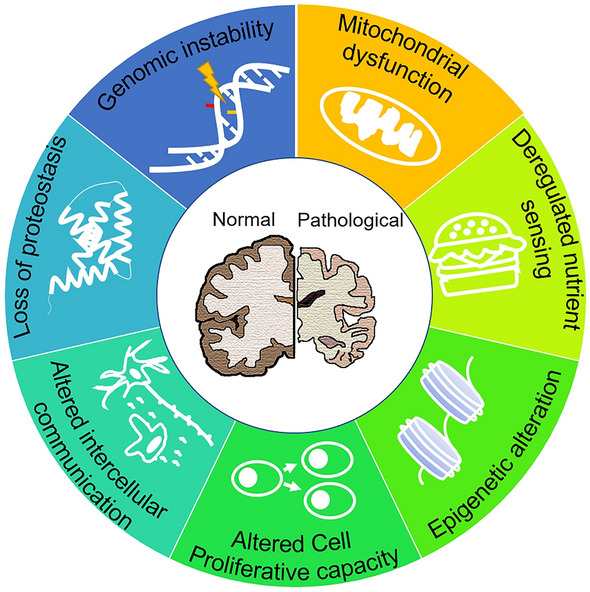

The function of the nutrient-sensing system changes with age. Previous studies have shown that several nutrient-sensing pathways play a role in regulating longevity and aging [40]. As shown in Fig. 2, these pathways include insulin and the insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling (IIS) pathway, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, the adenosine 5′ monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, and the sirtuin signaling pathway.

Fig. 2.

Nutrient-sensing pathways and aging. Molecules proposed to favor aging and prevent aging are shown in orange and green, respectively. IR, insulin receptor; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R, IGF-1 receptor; IRS, IR substrates; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; Akt, AKT serine/threonine kinase; FOXO, forkhead box O; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase-3; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; AMPK, adenosine 5′ monophosphate-activated protein kinase; ULK1, Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1; Sirt1, sirtuin 1; PGC1ɑ, PPARG coactivator 1 alpha; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydride.

The IIS pathway, which represents nutrient abundance and anabolism, is the most conserved aging-modifying pathway in the process of evolution, and its downstream targets, forkhead box O (FOXO) family transcription factors, are also highly conserved in regulating longevity across species: inhibiting the activity of the IIS pathway extends the lifespan of yeast, worms, flies, and mammals [40]. Brain IIS plays a key role in sensing and regulating body metabolism, as well as regulating synaptic plasticity, learning, and neural development [41]. It is worth noting that, although the IIS pathway plays a small role in glucose metabolism in the brain, it is essential for maintaining a healthy brain metabolism [42]. The IIS pathway sends signals of the body's energy status to the brain and regulates eating behavior: excessive insulin inhibits eating, while a decreased insulin level causes overeating through the IIS pathway in the hypothalamus [43, 44]. Interestingly, growth hormone and IGF-1 levels decrease during normal aging, and this phenomenon has also been reported in mouse models of premature aging [45]. One possible explanation for this is that cells compensate for aging and age-related declines by downregulating the function of IIS pathways. mTOR kinase, another highly-conserved factor for sensing and responding to nutrient signals (including signals related to the availability of amino-acids), also plays a key role in modulating aging, and administration of the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is considered to be one of the most effective approaches to increasing the lifespan in mammals [46, 47]. Of note, the activity of the mTOR signaling pathway also decreases during normal brain aging [48], but in AD patients, the mTOR pathway is hyperactivated [49]. Some other pathways (like AMPK and sirtuins) sense nutrient scarcity and catabolism, and they act in an opposite way to modulate aging. Studies have shown that the responsiveness of AMPK signaling decreases with age and enhancing AMPK activity delays aging [50]. In general, the available evidence has demonstrated that anabolic signaling accelerates the rate of aging and reduced nutritional signaling increases longevity [51].

In aging brains, reduced glucose metabolism is found in many brain regions, particularly marked in the temporal and parietal lobes, and the motor cortex [52]. This alteration is much more profound in these regions of elderly patients with dementia [53]. In patients with neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and PD, reduced brain glucose consumption and energy production are associated with altered IIS, mTOR, and AMPK signaling. Studies have shown that brain insulin resistance accelerates aging, while maintaining brain insulin sensitivity delays aging [54]. An abnormal distribution and cellular localization of insulin receptors (IR and IGF1R) have been reported in AD neurons, suggesting possible insulin resistance in the AD brain [55]. The dysfunction of insulin and IGF-1 signaling may also contribute to the progress of AD, as insulin signaling plays a critical role in the clearance of Aβ and inhibiting Tau aggregation [56]. Disruption of insulin receptor substrates 2 (IRS2) promotes Tau phosphorylation by activating glycogen synthase kinase-3β in the Irs2−/− mouse brain [57]. Interestingly, other lines of evidence support the idea that inhibition of IIS alleviates AD-related phenotypes [58]. Neuron-specific knockout of IRS2 (but not IR or IGF1R) delays Aβ accumulation in a mouse model of AD [59], suggesting that the role of IIS in AD pathology is distinct in different cell types. Inconsistent changes in the AMPK pathway have also been reported in the AD brain. Generally, AMPK activity decreases in the AD brain, but it is abnormally activated in neurons bearing neurofibrillary pre-tangles and tangles; activated AMPK accumulates near Aβ plaques and tau tangles instead of in the nucleus, where AMPK usually functions [60]. Thus, moderating the sensitivity of AMPK pathways rather than simply inhibiting or activating them (which may cause resistance) may be more effective for relieving AD symptoms [54].

The manipulation of nutritional signaling pathways may provide effective approaches to alleviate brain aging and prevent age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Dietary restriction is probably the best known way to extend the lifespan and the healthspan [61–63]. A reduced inflammatory response and improved capacity of DNA repair are found in dietary-restricted mice and rats, as a result of upregulation of genes associated with inhibition of the inflammatory response and DNA synthesis/repair [64–66]. In animal models of AD and stroke, dietary restriction protects neurons in the brain from degeneration [67]; however, no benefit of dietary restriction on alleviation of the disease has been reported in an animal model of ALS [68]. Recently, studies on intermittent fasting (IF) are gaining increasing interest [69]. Studies suggest that IF has no positive short-term effects on cognition in healthy subjects, but has benefits in relieving the symptoms of epilepsy, AD, and multiple sclerosis [70]. Although the exact mechanism of IF in healthy aging is still unclear, the process is thought to be associated with the IIS pathway, the mTOR pathway, and the like [71].

Epigenetic Alteration

Epigenetics is the best choice for organisms to adapt to a changeable environment: heritable changes in gene expression occur while the DNA sequence does not change. Epigenetic changes include alterations in DNA methylation patterns, post-translational modification of histones, chromatin remodeling, and expression of non-coding RNAs [72]. Generally, diversity of modification helps individuals adapt to their environment; however, studies have shown that as individuals age, heterogeneity of DNA modifications in the brain decreases at both the individual and tissue levels, and convergence of neighboring DNA modifications suggests that there exist some rules of age-related alteration in DNA modifications during brain aging [73]. Interestingly, changes in the levels of DNA methylation at 353 CpG sites have been proposed as an epigenetic clock (known as DNA methylation age) to predict the biological age of human tissues including the brain [74]. Generally, histone methylation levels in the promoter regions of many synaptic function-related genes increase, while histone acetylation levels decrease in aging brains [75]. These epigenetic changes ultimately affect gene expression, leading to cognitive decline during aging.

Epigenetic alterations have also been widely reported in pathological brain aging [76], and these alterations may be different from those that occur in normal aging. For example, the methylation level in the promotor region of many AD risk genes (such as APP, PS1, and BACE1) changes significantly in AD patients’ brains compared with that of age-matched normally aging brains [77]. However, the global changes in DNA methylation under AD conditions is controversial: a decreased DNA methylation level has been found in the cell model of AD, but an increased DNA methylation level has been reported in a mouse model of AD [78]. Normal aging results in significant accumulation, while AD entails a marked loss, of H4K16ac in the proximity of genes associated with the aging process and AD, suggesting that the marker H4K16ac plays a distinct role in normal aging and age-associated neurodegeneration [79].

On the other hand, some epigenetic changes could be a continuous regulatory mechanism for normal and pathological brain aging. Studies have reported an increase in the levels of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 in aging brains of aged mice, mouse models of AD and Huntington’s disease (HD), as well as AD and HD patients [80, 81]. Pharmacological inhibition of the histone methyl transferases SUV39H1 and EHMT1/EHMT2 decreases the levels of H3K9me3 in the hippocampus and improves cognitive function in aged mice and a mouse model of AD, respectively [82, 83]. Strikingly, a recent study found that the expression levels of EHMT1 and an epigenetic reader BAZ2B increase with age, and are positively correlated with the progress of AD in the prefrontal cortex of human brains. Ablation of Baz2b enhances mitochondrial function in the brain and improves cognitive function in aged mice by affecting the H3K9 methylation level in the promotor regions of genes associated with core metabolism [26].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) provide another epigenetic mechanism for regulating brain aging. Although dysfunction of miRNAs affects neuroinflammation, cognitive decline, and other age-related deteriorations, currently little is known about functional changes in brain miRNAs during aging [84]. Microarray data indicate that some miRNAs, including miR-139-5p, miR-342-3p, and miR-204, exhibit increased expression levels in the hippocampus of aged mice, and they may suppress the surface expression of neurotransmitter receptors and contribute to age-related cognitive decline [85, 86]. Recent evidence suggests that miRNAs can be packed into exosomes, which can be transported cross tissues and probably coordinate the ageing rate of different organs. Astrocytic apolipoprotein E3 (APOE3) vesicles have been reported to carry diverse regulatory miRNAs, which specifically silence genes involved in neuronal cholesterol biosynthesis, and ultimately promote histone acetylation and activate gene expression in neurons. In contrast, APOE4, a risk factor for AD, carries fewer miRNAs and thus down-regulates the acetylation level of histone in the promoter regions of synapse-related genes, ultimately leading to repressed expression of these genes and a decline in cognitive ability [87].

Overall, the potential reversibility of epigenetic alterations provides exciting chances to alter the trajectory of brain aging under both normal and pathological conditions. Studies have shown that some epigenetic factors regulate healthy aging, such as BAZ2B and EHMT1, and they may be targets for slowing brain aging and treating age-related diseases [26]. Expression of octamer-binding transcription factor 3/4, SRY-Box transcription factor 2 (Sox2), Kruppel-like factor 4, and the proto-oncogene c-Myc (OSKM, also known as Yamanaka factors) in cells reshapes epigenetic markers and reprograms cells to a pluripotent state, as well as erasing cellular markers of senescence [88–90]. Periodic expression of OSKM for a short period of time improves the aging phenotypes of aged mice and prolongs the life span of progeroid mice [90], and the effect on delaying aging increases with the cumulative time of partial reprogramming in aged mice, suggesting that epigenetic changes occur early during aging and that earlier interventions may get better results [91]. Notably, despite controversy, reprogramming glial cells into neurons is an exciting and challenging approach to treating neurodegenerative diseases [92, 93]. However, more work remains to be done to understand epigenetic regulation in aging brains under both normal and pathological conditions.

Altered Cell Proliferative Capacity

In most organs, one of the most obvious age-related hallmarks is the decline in the regenerative potential of tissues, which is a result of telomere attrition, stem cell exhaustion, and cellular senescence [94, 95]. Evidence shows that telomere alteration affects the rate of aging. It has been demonstrated that mice with shortened and lengthened telomeres show decreased and increased lifespan, respectively. Pathological dysfunction of telomeres accelerates aging, while experimental stimulation of telomerase delays aging [96, 97]. However, neurons are permanently postmitotic and neuronal telomeres do not shorten in aging brains. Interestingly, changes in the telomere have shown an opposite role in different studies of pathological brain aging. Telomere lengths are shorter in AD patients, and telomerase-deficient mice showed signs of neurodegeneration [98, 99]. However, another study in the APP23 transgenic mouse have shown that, although telomere shortening disrupts adult neurogenesis and the maintenance of neurons after mitosis, it reduces the formation of amyloid plaques and alleviates the deficits in learning and memory [100].

In the adult brain, neurogenesis only occurs in a few regions, including the hippocampal dentate gyrus, sub-ventricular zone (SVZ), and olfactory bulb [101, 102]. Age-related changes in neurogenesis have been found in both normal and pathological aging brains. During normal and pathological aging, a decrease of neurogenesis in the hippocampus, SVZ, and olfactory bulb may lead to cognitive and olfactory deficits [103]. Neural stem cell transplantation has been considered as a potential treatment for some age-related neurodegenerative diseases associated with neuronal loss [104]. However, aberrant neurogenesis has been reported in aging brains with neurodegenerative disorders, including AD, PD, and HD [105]. For example, the human HD brain exhibits greater neural progenitor cell (NPC) proliferation that is proportional to the severity of the disease, and modifies the pathology of the disease [106]. Both increased and decreased neurogenesis have been reported in the brains of AD model mice and AD patients [105, 107]. Some studies on postmortem brain tissue from AD patients found a higher level of neurogenesis in the hippocampus [108], while other studies found that neurogenic markers like Musashi-1, Sox2, and doublecortin are downregulated in the brains of AD patients [109, 110]. This discrepancy may be explained by difference in the animal model used and the stage of the disease. Overall, the capacity for neurogenesis may change differently in normal and pathological brain aging, despite the fact that their states are both abnormal and may contribute to the cognitive impairments.

NPCs and proliferation-competent glial cells can undergo senescence. Cells with features of senescence have been found in aging brains under both normal and pathological conditions [111]. Senescence alters cellular morphology and proteostasis, decreases autophagy-lysosome function, and enhances the secretory activity of cells, which leads to a pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype [112]. Senescent cells accumulate during aging and negatively influence a heathy lifespan. In AD model mice, the telomeres in microglia shorten during continuous replication, leading to replicative senescence and contributing to AD pathology [113]. Although neurons no longer undergo mitosis, they show some features of senescence in aging brains; the level of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity increases in neurons in the CA3 region of aged rat brains, and a DNA damage-induced senescence-like phenotype has also been reported in aging neurons [114, 115]. Removal of senescent cells in the brain by pharmacological intervention, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, or genetic/antibody-mediated depletion alleviates the inflammation and cognitive impairment in naturally aging mice, and prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases [116–119].

Altered Intercellular Communication

Maintaining connections with other cells is critical for preserving the functions of neurons. With increasing age, the communication between neuronal cells changes significantly, causing decreased synaptic connections, increased inflammation, and degenerated neurovascular units (NVUs) [3, 8].

The fidelity of neural networks within and between brain regions is disturbed with age. Functional imaging studies have revealed a global loss of integrative function in aging human brains. Age-related dysfunction of neural networks is not due to a loss of neurons (which is minimal in normal aging brains), but to abnormal synaptic connections that form the basis of neural circuits in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex [120]. The expression levels of most synaptic function-related genes are down-regulated [13] and the integrity of the white matter (which is composed of bundles of axons) is compromised during normal aging of the human brain [121]. Not surprisingly, these alterations may render neurons more vulnerable to degeneration under pathological conditions [122], reinforcing the importance of maintaining synaptic function to achieve healthy aging of the brain. In support of this notion, recent studies have demonstrated that improving synaptic function by enhancing neurotransmitter levels alleviates the age-related deterioration of cognitive function in old people and animal models [123, 124]. However, other lines of evidence have shown that inhibition of neuronal excitability delays aging. Mutations that cause defects in specific sensory neurons extends the lifespan in C. elegans, and ablation of RE1 silencing transcription factor causes abnormal neural excitation in the aged mouse brain and accelerates aging through the IIS pathway [125, 126]. These findings suggest that higher neural activity is not always better, and the changes of neural connections may also be an adaptive mechanism in response to aging.

In addition to synaptic connections, factors such as neurotrophic and inflammation factors from other cells influence neuronal survival. In neurodegenerative diseases, synaptic inputs may be altered by inhibiting anterograde axonal transport and/or axonal degeneration, resulting in reduced release of transmitters and neurotrophic peptides [127]. During aging, glial cells, particularly microglia, often exhibit an activated state, causing long-term and chronic inflammation in the nervous system [128], which may lead to cognitive impairments as evidenced by the findings that in both normal and pathological brain aging, inhibition of the inflammatory responses has been reported to improve learning and cognition [129, 130]. For example, activating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, inhibiting the activation of microglia, or restoring the metabolic levels of myeloid cells in aging mice alleviates inflammation in the nervous system and restores cognitive function [131–133].

NVUs also degenerate with age [134]. Changes of NVUs in aging usually result in impaired integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and infiltration of blood-derived proteins, affecting the blood oxygen supply to nerve cells. The degeneration of NVUs eventually impairs cognitive function and increases the risk of stroke and cerebral small-vessel disease, among others [135, 136]. Interestingly, unique changes in NVUs occur in some neurodegenerative diseases. For example, Aβ42 has been reported to disturb the organization of junctional complexes containing tight and adherent junctions between endothelial cells, causing leakage of plasma protein and more severe damage in brains with AD [137]. The deposition of α-synuclein and matrix metallopeptidase 3 damages the BBB and exacerbates inflammation in PD patients’ brains [138–140]. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that protecting the functions of NVUs is a promising strategy for preventing some neurodegenerative diseases.

Loss of Proteostasis

The proteostasis network regulates cellular protein homeostasis and it consists of the protein biosynthetic machinery, the molecular chaperone system, and protein clearance pathways including the proteasome and autophagy systems. The loss of proteostasis, a failure of aging cells in responding to proteotoxic challenges, has been considered a hallmark of organismal aging [3]. A recent study has proposed that age-related changes in translational efficiency initially drive the deterioration of proteostasis [141]. Genetic and pharmacological strategies to improve proteostasis promote healthy aging in animal models and delay the onset of age-related pathologies associated with protein aggregation [142].

In aged brains, the functions of protein chaperones and proteolytic systems decrease significantly [143]. Once the capacity of these systems decreases below a threshold level, some aggregation-prone proteins aggregate and exist in an insoluble state. The threshold is lowered in some stress conditions, such as the presence of disease-associated mutations in genes encoding aggregation-prone proteins [142]. Indeed, in age-related neurodegenerative diseases, loss of protein homeostasis often shows more severe pathological features. For example, aggregation of Aβ and hyperphosphorylation of Tau are the most obvious pathological features of AD; and a large amount of α-synuclein aggregates in dopaminergic neurons in PD patients [144]. Stress response pathways shape the proteostasis network, affecting the process of aging and the onset/progress of neurodegeneration. The aggregation of unfolded proteins perturbs the homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and triggers ER stress-induced activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR), an initially adaptive mechanism that restores cellular proteostasis [145, 146]. However, studies have demonstrated that chronic activation of the UPR in the ER is associated with neuronal degeneration in post-mortem brain tissues from patients with neurodegenerative diseases [145, 146]. Thus, activation of the UPR in the ER has distinct and even opposite effects on the progress of neurodegeneration, probably depending on the stage of disease.

It is worth noting that the relation between cognitive impairment and toxic protein aggregation remains controversial. In about a quarter of patients diagnosed as having AD-like diseases, the level of Aβ plaques and tau tangles does not reach the diagnostic threshold of AD [147, 148]. Many old people who exhibit extensive Aβ plaque accumulation only have minimal neuronal loss and a marginal decline in cognitive function [149, 150]. These suggest that there may be neuroprotective mechanisms that we have not yet found that influence the role of proteostasis during brain aging.

Conclusions and Perspective

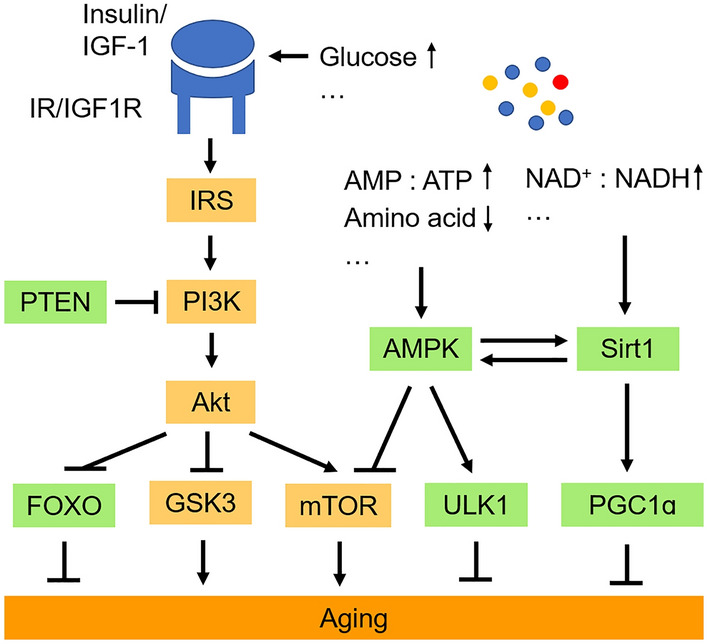

Brain aging is a major risk factor for many neurodegenerative diseases, but the mechanisms underlying the transition from normal aging to neurodegenerative disorders are complex and remain to be fully elucidated. The hallmarks of brain aging have been associated with the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, which are quite common among older populations, leading to the hypothesis that neurodegeneration is accelerated brain ageing [151]. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 3, some hallmarks of brain aging occur in both normal and pathological brain aging, but they are more exacerbated in a pathological state. These are genomic instability, deregulated nutrient sensing, loss of proteostasis, and mitochondrial dysfunction. However, some unique molecular and cellular processes occur in normal aging or neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, some changes in intercellular communication (such as NUV damage caused by Aβ in AD [137]) and epigenetic modifications (such as methylation level in the promotor region of many AD risk genes [77]) specifically occur in aging brains under pathological conditions. Strikingly, other molecular and cellular changes (such as alteration in telomeres and stem cells) in the brain are distinct between normal aging and neurodegeneration, showing an antagonistic mechanism. It is worth noting that the opposite changes that occur in neurodegenerative diseases ultimately exacerbate the pathological phenotype rather than alleviate the aging phenotype.

Fig. 3.

Similar and different molecular and cellular changes in aging brains under normal and pathological conditions. Changes occurring in normal and pathological aging brains are shown in green and in orange, respectively. These changes are only examples, not the full range of changes during normal and pathological brain aging. IIS, the insulin and IGF-1 signaling pathway; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin.

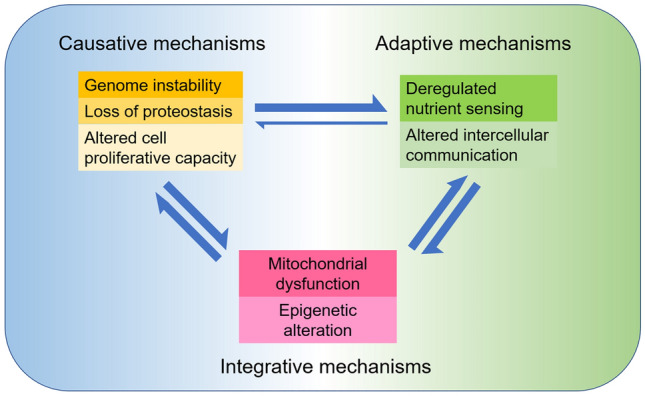

Brain aging is a key regulator of longevity and functional deterioration. Molecular and cellular alterations associated with the aging process in the brain could be adaptive factors for maintaining neural function or causative factors for deteriorating systemic functions [3]. Generally speaking, as shown in Fig. 4, genome instability, loss of proteostasis, and altered cell proliferative capacity are causative mechanisms for cognitive impairment [23, 95, 142]; while deregulated nutrient sensing and altered intercellular communication are mainly considered to be adaptive mechanisms for brain aging because down-regulation of nutrient sensing and neuronal excitability have been reported to extend lifespan [45, 125]. Mitochondrial dysfunction and epigenetic changes could be both causative and adaptive mechanisms for brain aging [24, 25, 72]. For example, mild downregulation of mitochondrial function promotes longevity, while severe impairment of mitochondria leads to neuronal death and neurodegeneration. Yet, the causative and adaptive mechanisms are not absolutely inconvertible; the adaptive molecular and cellular changes in the aging brain may also contribute to the decline of some subsets of behaviors. Future comprehensive studies on single-cell transcriptomics [152] of normal, protected, and pathological aging human brains may help to further clarify the causative and adaptive age-related molecular and cellular events in a cell type-specific pattern.

Fig. 4.

Functional interconnections between the molecular and cellular events occurring in aging brains under normal and pathological conditions. The seven molecular and cellular events occurring in aging brains can be divided into three categories. Genome instability, loss of proteostasis, and altered cell proliferative capacity are supposed to be causative mechanisms; deregulated nutrient sensing and altered intercellular communication are mostly adaptive mechanisms; while mitochondrial dysfunction and epigenetic alteration could be both causative and adaptive for brain aging and neurodegeneration.

It is worth noting that the hallmarks of brain aging are interrelated and interdependent, and none of them occur in isolation. For example, age-related accumulation of DNA damage and epigenetic aberrations alters gene expression, resulting in dysfunction of mitochondria, deregulation of nutrient sensing, and loss of proteostasis; all of which in turn lead to more severe cytotoxicity and genomic instability, finally causing pathological changes in intercellular communication and transforming physiological changes into pathological changes in the whole brain. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that caloric restriction protects aging brains from deterioration by stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis and neural signaling pathways in neurons [8], supporting a link between nutrient sensing and mitochondrial function in modulating aging of the brain.

Given that normal and pathological brain aging are closely linked, approaches that promote healthy aging are worth trying to treat aging-related diseases. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure of an aged animal to young blood improves the aging phenotypes, and plasma replacement has also been reported to be beneficial for treating AD [153–155]. A combination of removal of senescent cells with transient somatic reprogramming synergistically extends lifespan and improves health [156]. On the other hand, brain aging is a complex and integral process, therefore future development of therapeutic approaches for treating neurodegenerative diseases needs a greater understanding of not only the distinct molecular changes occurring in pathological aging brains, but also the biological context of normal aging of the brain. Many mouse models of AD develop disease symptoms too early, which may not be suitable for the search for the true pathogenesis of the disease [157, 158]. Researchers must take these questions into account when using these model mice.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC2000400), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31925022 and 91949206), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB32020100), the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2018SHZDZX05), and the Innovative Research Team of High-level Local Universities in Shanghai (SHSMU-ZDCX20212501).

References

- 1.de Almeida A, Ribeiro TP, de Medeiros IA. Aging: Molecular Pathways and Implications on the Cardiovascular System. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:7941563. doi: 10.1155/2017/7941563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eikelboom WS, Bertens D, Kessels RPC. Cognitive rehabilitation in normal aging and individuals with subjective cognitive decline. Cognitive Rehabilitation and Neuroimaging. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020: 37–67.

- 3.López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nouchi R, Taki Y, Takeuchi H, Sekiguchi A, Hashizume H, Nozawa T, et al. Four weeks of combination exercise training improved executive functions, episodic memory, and processing speed in healthy elderly people: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. AGE. 2014;36:787–799. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9588-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia L, Du Y, Chu L, Zhang Z, Li F, Lyu D, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e661–e671. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenyon CJ. The genetics of ageing. Nature. 2010;464:504–512. doi: 10.1038/nature08980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gems D, Partridge L. Genetics of longevity in model organisms: Debates and paradigm shifts. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:621–644. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mattson MP, Arumugam TV. Hallmarks of brain aging: Adaptive and pathological modification by metabolic states. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1176–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:565–581. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumitriu D, Hao J, Hara Y, Kaufmann J, Janssen WGM, Lou W, et al. Selective changes in thin spine density and morphology in monkey prefrontal cortex correlate with aging-related cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7507–7515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6410-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke SN, Barnes CA. Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrn1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moskalev AA, Shaposhnikov MV, Plyusnina EN, Zhavoronkov A, Budovsky A, Yanai H, et al. The role of DNA damage and repair in aging through the prism of Koch-like criteria. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:661–684. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu T, Pan Y, Kao SY, Li C, Kohane I, Chan J, et al. Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature. 2004;429:883–891. doi: 10.1038/nature02661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopes AFC, Bozek K, Herholz M, Trifunovic A, Rieckher M, Schumacher BAC. elegans model for neurodegeneration in Cockayne syndrome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:10973–10985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaposhnikov M, Proshkina E, Shilova L, Zhavoronkov A, Moskalev A. Lifespan and stress resistance in Drosophila with overexpressed DNA repair genes. Sci Rep. 2015;5:15299. doi: 10.1038/srep15299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberdoerffer P, Michan S, McVay M, Mostoslavsky R, Vann J, Park SK, et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135:907–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher B, Pothof J, Vijg J, Hoeijmakers JHJ. The central role of DNA damage in the ageing process. Nature. 2021;592:695–703. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adamec E, Vonsattel JP, Nixon RA. DNA strand breaks in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 1999;849:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merlo D, Cuchillo-Ibañez I, Parlato R, Rammes G. DNA damage, neurodegeneration, and synaptic plasticity. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:1206840. doi: 10.1155/2016/1206840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, et al. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:515–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzmaurice PS, Shaw IC, Kleiner HE, Miller RT, Monks TJ, Lau SS, et al. Evidence for DNA damage in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:797–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraytsberg Y, Kudryavtseva E, McKee AC, Geula C, Kowall NW, Khrapko K. Mitochondrial DNA deletions are abundant and cause functional impairment in aged human substantia nigra neurons. Nat Genet. 2006;38:518–520. doi: 10.1038/ng1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madabhushi R, Pan L, Tsai LH. DNA damage and its links to neurodegeneration. Neuron. 2014;83:266–282. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durieux J, Wolff S, Dillin A. The cell-non-autonomous nature of electron transport chain-mediated longevity. Cell. 2011;144:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan J, Chang SY, Yin SG, Liu ZY, Cheng X, Liu XJ, et al. Two conserved epigenetic regulators prevent healthy ageing. Nature. 2020;579:118–122. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonda DJ, Wang X, Lee HG, Smith MA, Perry G, Zhu X. Neuronal failure in Alzheimer's disease: A view through the oxidative stress looking-glass. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:243–252. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1424-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, Zhong C. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Bull. 2014;30:271–281. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1423-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang W, Zhao F, Ma X, Perry G, Zhu X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: Recent advances. Mol Neurodegeneration. 2020;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Su B, Lee HG, Li X, Perry G, Smith MA, et al. Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai Q, Tammineni P. Alterations in mitochondrial quality control in Alzheimer's disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:24. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirsch E, Graybiel AM, Agid YA. Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson's disease. Nature. 1988;334:345–348. doi: 10.1038/334345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galvan A, Wichmann T. Pathophysiology of Parkinsonism. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1459–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2015;85:257–273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nisoli E, Tonello C, Cardile A, Cozzi V, Bracale R, Tedesco L, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science. 2005;310:314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1117728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Civitarese AE, Carling S, Heilbronn LK, Hulver MH, Ukropcova B, Deutsch WA, et al. Calorie restriction increases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanza IR, Zabielski P, Klaus KA, Morse DM, Heppelmann CJ, Bergen HR, III, et al. Chronic caloric restriction preserves mitochondrial function in senescence without increasing mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 2012;16:777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mouchiroud L, Houtkooper RH, Moullan N, Katsyuba E, Ryu D, Cantó C, et al. The NAD+/sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through activation of mitochondrial UPR and FOXO signaling. Cell. 2013;154:430–441. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin JA, Gao G, Liu XJ, Hao ZQ, Li K, Kang XL, et al. Genetic variation in glia–neuron signalling modulates ageing rate. Nature. 2017;551:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nature24463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span—from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akintola AA, van Heemst D. Insulin, aging, and the brain: Mechanisms and implications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;6:13. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heni M, Kullmann S, Preissl H, Fritsche A, Häring HU. Impaired insulin action in the human brain: Causes and metabolic consequences. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:701–711. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz MW, Sipols AJ, Marks JL, Sanacora G, White JD, Scheurink A, et al. Inhibition of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y gene expression by insulin. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3608–3616. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1597158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brüning JC, Gautam D, Burks DJ, Gillette J, Schubert M, Orban PC, et al. Role of brain insulin receptor in control of body weight and reproduction. Science. 2000;289:2122–2125. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schumacher B, van der Pluijm I, Moorhouse MJ, Kosteas T, Robinson AR, Suh Y, et al. Delayed and accelerated aging share common longevity assurance mechanisms. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, et al. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papadopoli D, Boulay K, Kazak L, Pollak M, Mallette F, Topisirovic I, et al. mTOR as a central regulator of lifespan and aging. F1000Res 2019, 8: F1000FacultyRev–F1000Faculty998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Romine J, Gao X, Xu XM, So KF, Chen J. The proliferation of amplifying neural progenitor cells is impaired in the aging brain and restored by the mTOR pathway activation. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1716–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Alafuzoff I, Soininen H, Winblad B, Pei JJ. Levels of mTOR and its downstream targets 4E-BP1, eEF2, and eEF2 kinase in relationships with tau in Alzheimer's disease brain. FEBS J. 2005;272:4211–4220. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) controls the aging process via an integrated signaling network. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barzilai N, Huffman DM, Muzumdar RH, Bartke A. The critical role of metabolic pathways in aging. Diabetes. 2012;61:1315–1322. doi: 10.2337/db11-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goyal MS, Vlassenko AG, Blazey TM, Su Y, Couture LE, Durbin TJ, et al. Loss of brain aerobic glycolysis in normal human aging. Cell Metab. 2017;26:353–360.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato T, Inui Y, Nakamura A, Ito K. Brain fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET in dementia. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;30:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masternak MM, Panici JA, Bonkowski MS, Hughes LF, Bartke A. Insulin sensitivity as a key mediator of growth hormone actions on longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A:516–521. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moloney AM, Griffin RJ, Timmons S, O’Connor R, Ravid R, O’Neill C. Defects in IGF-1 receptor, insulin receptor and IRS-1/2 in Alzheimer's disease indicate possible resistance to IGF-1 and insulin signalling. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:224–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gasparini L, Xu H. Potential roles of insulin and IGF-1 in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:404–406. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schubert M, Brazil DP, Burks DJ, Kushner JA, Ye J, Flint CL, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-2 deficiency impairs brain growth and promotes tau phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7084–7092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-18-07084.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Candeias E, Duarte AI, Carvalho C, Correia SC, Cardoso S, Santos RX, et al. The impairment of insulin signaling in Alzheimer's disease. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:951–957. doi: 10.1002/iub.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freude S, Hettich MM, Schumann C, Stöhr O, Koch L, Köhler C, et al. Neuronal IGF-1 resistance reduces Abeta accumulation and protects against premature death in a model of Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2009;23:3315–3324. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-132043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vingtdeux V, Davies P, Dickson DW, Marambaud P. AMPK is abnormally activated in tangle- and pre-tangle-bearing neurons in Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:337–349. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0759-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caprara G. Diet and longevity: The effects of traditional eating habits on human lifespan extension. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2018;11:261–294. [Google Scholar]

- 62.McCay C, Crowell MF. Prolonging the life span. Science Monthly. 1934;39:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hansen M, Kennedy BK. Does longer lifespan mean longer healthspan? Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:565–568. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vermeij WP, Dollé MET, Reiling E, Jaarsma D, Payan-Gomez C, Bombardieri CR, et al. Restricted diet delays accelerated ageing and genomic stress in DNA-repair-deficient mice. Nature. 2016;537:427–431. doi: 10.1038/nature19329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Green CL, Lamming DW, Fontana L. Molecular mechanisms of dietary restriction promoting health and longevity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23:56–73. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morgan TE, Wong AM, Finch CE. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of dietary restriction in slowing aging processes. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2007;35:83–97. doi: 10.1159/000096557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prolla TA, Mattson MP. Molecular mechanisms of brain aging and neurodegenerative disorders: Lessons from dietary restriction. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:S21–S31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01957-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pedersen WA, Mattson MP. No benefit of dietary restriction on disease onset or progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase mutant mice. Brain Res. 1999;833:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01471-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Varady K. Intermittent fasting is Gaining interest fast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:587. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gudden J, Arias Vasquez A, Bloemendaal M. The effects of intermittent fasting on brain and cognitive function. Nutrients. 2021;13:3166. doi: 10.3390/nu13093166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Longo VD, di Tano M, Mattson MP, Guidi N. Intermittent and periodic fasting, longevity and disease. Nat Aging. 2021;1:47–59. doi: 10.1038/s43587-020-00013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bollati V, Baccarelli A. Environmental epigenetics. Heredity. 2010;105:105–112. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oh G, Ebrahimi S, Wang SC, Cortese R, Kaminsky ZA, Gottesman II, et al. Epigenetic assimilation in the aging human brain. Genome Biol. 2016;17:76. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0946-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maity S, Farrell K, Navabpour S, Narayanan SN, Jarome TJ. Epigenetic mechanisms in memory and cognitive decline associated with aging and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:12280. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tecalco-Cruz AC, Ramírez-Jarquín JO, Alvarez-Sánchez ME, Zepeda-Cervantes J. Epigenetic basis of Alzheimer disease. World J Biol Chem. 2020;11:62–75. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v11.i2.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chouliaras L, Rutten BPF, Kenis G, Peerbooms O, Visser PJ, Verhey F, et al. Epigenetic regulation in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;90:498–510. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sanchez-Mut JV, Gräff J. Epigenetic alterations in Alzheimer's disease. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:347. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nativio R, Donahue G, Berson A, Lan Y, Amlie-Wolf A, Tuzer F, et al. Dysregulation of the epigenetic landscape of normal aging in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:497–505. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0101-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ryu H, Lee J, Hagerty SW, Soh BY, McAlpin SE, Cormier KA, et al. ESET/SETDB1 gene expression and histone H3 (K9) trimethylation in Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19176–19181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606373103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walker MP, LaFerla FM, Oddo SS, Brewer GJ. Reversible epigenetic histone modifications and Bdnf expression in neurons with aging and from a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. AGE. 2013;35:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9375-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snigdha S, Prieto GA, Petrosyan A, Loertscher BM, Dieskau AP, Overman LE, et al. H3K9me3 inhibition improves memory, promotes spine formation, and increases BDNF levels in the aged Hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2016;36:3611–3622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2693-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zheng Y, Liu A, Wang ZJ, Cao Q, Wang W, Lin L, et al. Inhibition of EHMT1/2 rescues synaptic and cognitive functions for Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2019;142:787–807. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Danka Mohammed CP, Park JS, Nam HG, Kim K. microRNAs in brain aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;168:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cosín-Tomás M, Alvarez-López MJ, Sanchez-Roige S, Lalanza JF, Bayod S, Sanfeliu C, et al. Epigenetic alterations in hippocampus of SAMP8 senescent mice and modulation by voluntary physical exercise. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:51. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mohammed CPD, Rhee H, Phee BK, Kim K, Kim HJ, Lee H, et al. miR-204 downregulates EphB2 in aging mouse hippocampal neurons. Aging Cell. 2016;15:380–388. doi: 10.1111/acel.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li X, Zhang J, Li D, He C, He K, Xue T, et al. Astrocytic ApoE reprograms neuronal cholesterol metabolism and histone-acetylation-mediated memory. Neuron. 2021;109:957–970.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Jaenisch R. Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:427–439. doi: 10.1038/nrg3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ocampo A, Reddy P, Martinez-Redondo P, Platero-Luengo A, Hatanaka F, Hishida T, et al. In vivo amelioration of age-associated hallmarks by partial reprogramming. Cell. 2016;167:1719–1733.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Browder KC, Reddy P, Yamamoto M, Haghani A, Guillen IG, Sahu S, et al. In vivo partial reprogramming alters age-associated molecular changes during physiological aging in mice. Nat Aging. 2022;2:243–253. doi: 10.1038/s43587-022-00183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang F, Cheng L, Zhang X. Reprogramming glial cells into functional neurons for neuro-regeneration: Challenges and promise. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:1625–1636. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00751-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jiang Y, Wang Y, Huang Z. Targeting PTB as a one-step procedure for in situ astrocyte-to-dopamine neuron reprogramming in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Bull. 2021;37:430–432. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00630-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sousounis K, Baddour JA, Tsonis PA. Aging and regeneration in vertebrates. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2014;108:217–246. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391498-9.00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rando TA, Jones DL. Regeneration, rejuvenation, and replacement: Turning back the clock on tissue aging. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2021;13:a040907. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a040907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Calado RT, Dumitriu B. Telomere dynamics in mice and humans. Semin Hematol. 2013;50:165–174. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu J, Wang L, Wang Z, Liu JP. Roles of telomere biology in cell senescence, replicative and chronological ageing. Cells. 2019;8:54. doi: 10.3390/cells8010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hochstrasser T, Marksteiner J, Humpel C. Telomere length is age-dependent and reduced in monocytes of Alzheimer patients. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Whittemore K, Derevyanko A, Martinez P, Serrano R, Pumarola M, Bosch F, et al. Telomerase gene therapy ameliorates the effects of neurodegeneration associated to short telomeres in mice. Aging. 2019;11:2916–2948. doi: 10.18632/aging.101982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rolyan H, Scheffold A, Heinrich A, Begus-Nahrmann Y, Langkopf BH, Hölter SM, et al. Telomere shortening reduces Alzheimer's disease amyloid pathology in mice. Brain. 2011;134:2044–2056. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J Comp Neurol. 1965;124:319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis. I. A longitudinal investigation of the kinetics, migration and transformation of cells incorporating tritiated thymidine in neonate rats, with special reference to postnatal neurogenesis in some brain regions. J Comp Neurol 1966, 126: 337–389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Lazarov O, Mattson MP, Peterson DA, Pimplikar SW, van Praag H. When neurogenesis encounters aging and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lunn JS, Sakowski SA, Hur J, Feldman EL. Stem cell technology for neurodegenerative diseases. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:353–361. doi: 10.1002/ana.22487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liszewska E, Jaworski J. Neural stem cell dysfunction in human brain disorders. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2018;66:283–305. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93485-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Curtis MA, Penney EB, Pearson AG, van Roon-Mom WMC, Butterworth NJ, Dragunow M, et al. Increased cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult human Huntington's disease brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9023–9027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532244100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu H, Song N. Molecular mechanism of adult neurogenesis and its association with human brain diseases. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2016;8:5–11. doi: 10.4137/JCNSD.S32204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ghosal K, Stathopoulos A, Pimplikar SW. APP intracellular domain impairs adult neurogenesis in transgenic mice by inducing neuroinflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Crews L, Adame A, Patrick C, Delaney A, Pham E, Rockenstein E, et al. Increased BMP6 levels in the brains of Alzheimer's disease patients and APP transgenic mice are accompanied by impaired neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12252–12262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1305-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Perry EK, Johnson M, Ekonomou A, Perry RH, Ballard C, Attems J. Neurogenic abnormalities in Alzheimer's disease differ between stages of neurogenesis and are partly related to cholinergic pathology. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;47:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sikora E, Bielak-Zmijewska A, Dudkowska M, Krzystyniak A, Mosieniak G, Wesierska M, et al. Cellular senescence in brain aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:646924. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.646924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gorgoulis V, Adams PD, Alimonti A, Bennett DC, Bischof O, Bishop C, et al. Cellular senescence: Defining a path forward. Cell. 2019;179:813–827. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hu Y, Fryatt GL, Ghorbani M, Obst J, Menassa DA, Martin-Estebane M, et al. Replicative senescence dictates the emergence of disease-associated microglia and contributes to Aβ pathology. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109228. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Geng YQ, Guan JT, Xu XH, Fu YC. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity expression in aging hippocampal neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:866–869. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jurk D, Wang C, Miwa S, Maddick M, Korolchuk V, Tsolou A, et al. Postmitotic neurons develop a p21-dependent senescence-like phenotype driven by a DNA damage response. Aging Cell. 2012;11:996–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bussian TJ, Aziz A, Meyer CF, Swenson BL, van Deursen JM, Baker DJ. Clearance of senescent glial cells prevents tau-dependent pathology and cognitive decline. Nature. 2018;562:578–582. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0543-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jin WN, Shi K, He W, Sun JH, van Kaer L, Shi FD, et al. Neuroblast senescence in the aged brain augments natural killer cell cytotoxicity leading to impaired neurogenesis and cognition. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:61–73. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00745-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jin JL, Liou AK, Shi Y, Yin KL, Chen L, Li LL, et al. CART treatment improves memory and synaptic structure in APP/PS1 mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10224. doi: 10.1038/srep10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Amor C, Feucht J, Leibold J, Ho YJ, Zhu C, Alonso-Curbelo D, et al. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies. Nature. 2020;583:127–132. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2403-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bishop NA, Lu T, Yankner BA. Neural mechanisms of ageing and cognitive decline. Nature. 2010;464:529–535. doi: 10.1038/nature08983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cox SR, Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM, Liewald DC, Hagenaars SP, Davies G, et al. Ageing and brain white matter structure in 3, 513 UK Biobank participants. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13629. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bennett IJ, Madden DJ. Disconnected aging: Cerebral white matter integrity and age-related differences in cognition. Neuroscience. 2014;276:187–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chowdhury R, Guitart-Masip M, Lambert C, Dayan P, Huys Q, Düzel E, et al. Dopamine restores reward prediction errors in old age. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:648–653. doi: 10.1038/nn.3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yin JA, Liu XJ, Yuan J, Jiang J, Cai SQ. Longevity manipulations differentially affect serotonin/dopamine level and behavioral deterioration in aging Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3947–3958. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4013-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zullo JM, Drake D, Aron L, O’Hern P, Dhamne SC, Davidsohn N, et al. Regulation of lifespan by neural excitation and REST. Nature. 2019;574:359–364. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1647-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Apfeld J, Kenyon C. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402:804–809. doi: 10.1038/45544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Garden GA, la Spada AR. Intercellular (mis)communication in neurodegenerative disease. Neuron. 2012;73:886–901. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Norden DM, Godbout JP. Review: Microglia of the aged brain: Primed to be activated and resistant to regulation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2012.01306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ownby RL. Neuroinflammation and cognitive aging. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Colonna M, Butovsky O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:441–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Minhas PS, Latif-Hernandez A, McReynolds MR, Durairaj AS, Wang Q, Rubin A, et al. Restoring metabolism of myeloid cells reverses cognitive decline in ageing. Nature. 2021;590:122–128. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03160-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Jang S, Dilger RN, Johnson RW. Luteolin inhibits microglia and alters hippocampal-dependent spatial working memory in aged mice. J Nutr. 2010;140:1892–1898. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Benfante R, Lascio SD, Cardani S, Fornasari D. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors targeting the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: A new therapeutic perspective in aging-related disorders. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:823–834. doi: 10.1007/s40520-019-01359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Li Y, Xie L, Huang T, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Qi B, et al. Aging neurovascular unit and potential role of DNA damage and repair in combating vascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:778. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yousufuddin M, Young N. Aging and ischemic stroke. Aging. 2019;11:2542–2544. doi: 10.18632/aging.101931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.De Silva TM, Faraci FM. Contributions of aging to cerebral small vessel disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2020;82:275–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021119-034338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Carrano A, Hoozemans JJM, van der Vies SM, Rozemuller AJM, van Horssen J, de Vries HE. Amyloid Beta induces oxidative stress-mediated blood-brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1167–1178. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Chung YC, Kim YS, Bok E, Yune TY, Maeng S, Jin BK. MMP-3 contributes to nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuronal loss, BBB damage, and neuroinflammation in an MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:370526. doi: 10.1155/2013/370526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Jangula A, Murphy EJ. Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood brain barrier permeability is enhanced by alpha-synuclein expression. Neurosci Lett. 2013;551:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Dohgu S, Takata F, Matsumoto J, Kimura I, Yamauchi A, Kataoka Y. Monomeric α-synuclein induces blood-brain barrier dysfunction through activated brain pericytes releasing inflammatory mediators in vitro. Microvasc Res. 2019;124:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Stein KC, Morales-Polanco F, van der Lienden J, Rainbolt TK, Frydman J. Ageing exacerbates ribosome pausing to disrupt cotranslational proteostasis. Nature. 2022;601:637–642. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04295-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hipp MS, Kasturi P, Hartl FU. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:421–435. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0101-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Powers ET, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW, Balch WE. Biological and chemical approaches to diseases of proteostasis deficiency. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:959–991. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.114844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Jahanshahi M, Krack P, Litvan I, Macias R, Bezard E, et al. Initial clinical manifestations of Parkinson's disease: Features and pathophysiological mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1128–1139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Stranahan AM, Mattson MP. Recruiting adaptive cellular stress responses for successful brain ageing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:209–216. doi: 10.1038/nrn3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Hetz C, Saxena S. ER stress and the unfolded protein response in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:477–491. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Mattson MP. Late-onset dementia: A mosaic of prototypical pathologies modifiable by diet and lifestyle. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2015;1:15003. doi: 10.1038/npjamd.2015.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Geddes JW, Tekirian TL, Soultanian NS, Ashford JW, Davis DG, Markesbery WR. Comparison of neuropathologic criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S99–S105. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly JF, Aggarwal NT, Shah RC, et al. Neuropathology of older persons without cognitive impairment from two community-based studies. Neurology. 2006;66:1837–1844. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219668.47116.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Kok E, Haikonen S, Luoto T, Huhtala H, Goebeler S, Haapasalo H, et al. Apolipoprotein E-dependent accumulation of Alzheimer disease-related lesions begins in middle age. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:650–657. doi: 10.1002/ana.21696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wyss-Coray T. Ageing, neurodegeneration and brain rejuvenation. Nature. 2016;539:180–186. doi: 10.1038/nature20411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Ximerakis M, Lipnick SL, Innes BT, Simmons SK, Adiconis X, Dionne D, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of the aging mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1696–1708. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ding XL, Lei P. Plasma replacement therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:89–90. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00394-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Sha SJ, Deutsch GK, Tian L, Richardson K, Coburn M, Gaudioso JL, et al. Safety, tolerability, and feasibility of young plasma infusion in the plasma for alzheimer symptom amelioration study: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:35–40. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Villeda SA, Plambeck KE, Middeldorp J, Castellano JM, Mosher KI, Luo J, et al. Young blood reverses age-related impairments in cognitive function and synaptic plasticity in mice. Nat Med. 2014;20:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nm.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Kaur P, Otgonbaatar A, Ramamoorthy A, Chua EHZ, Harmston N, Gruber J, et al. Combining stem cell rejuvenation and senescence targeting to synergistically extend lifespan. bioRxiv 2022, DOI:10.1101/2022.04.21.488994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 157.King A. The search for better animal models of Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2018;559:S13–S15. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Hall AM, Roberson ED. Mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Bull. 2012;88:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]