Abstract

The gut comprises the largest body interface with the environment and is continuously exposed to nutrients, food antigens, and commensal microbes, as well as to harmful pathogens. Subsets of both macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) are present throughout the intestinal tract, where they primarily inhabit the gut-associate lymphoid tissue (GALT), such as Peyer’s patches and isolated lymphoid follicles. In addition to their role in taking up and presenting antigens, macrophages and DCs possess extensive functional plasticity and these cells play complementary roles in maintaining immune homeostasis in the gut by preventing aberrant immune responses to harmless antigens and microbes and by promoting host defense against pathogens. The ability of macrophages and DCs to induce either inflammation or tolerance is partially lineage imprinted, but can also be dictated by their activation state, which in turn is determined by their specific microenvironment. These cells express several surface and intracellular receptors that detect danger signals, nutrients, and hormones, which can affect their activation state. DCs and macrophages play a fundamental role in regulating T cells and their effector functions. Thus, modulation of intestinal mucosa immunity by targeting antigen presenting cells can provide a promising approach for controlling pathological inflammation. In this review, we provide an overview on the characteristics, functions, and origins of intestinal macrophages and DCs, highlighting the intestinal microenvironmental factors that influence their functions during homeostasis. Unraveling the mechanisms by which macrophages and DCs regulate intestinal immunity will deepen our understanding on how the immune system integrates endogenous and exogenous signals in order to maintain the host’s homeostasis.

Keywords: Small intestine, Colon, Environmental Immunomodulators, Microbiota, Diet-derived antigens

1. Introduction

Intestinal macrophages and DCs are immersed in a unique and complex microenvironment that constitutes the largest collection of leukocytes and represents the richest antigen source in the organism [1]. The gut mucosa is characterized by the continuous exposure to nutrients, food antigens, commensal microbes, but also to harmful pathogens [2]. Intestinal macrophages and DCs are directly involved in the maintenance of immune homeostasis, or “tolerance” to unharmful substances and microbes as well as in the vigilance against infections. At steady state, these cells prevent overt inflammation by (i) phagocytosing dead and dying cells during normal cell turnover; (ii) taking up and killing bacteria that have breached the intestinal mucosa; and (iii) producing regulatory cytokines to maintain the balance between regulatory and effector T and B cells. In contrast, during pathogen invasion, inflammatory monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and effector T and B cells are induced by activated DCs and attracted to the sites of infection to provide host defense. The delicate balance between these regulatory and inflammatory states of monocytes, macrophages, and DCs is under tight control, and when disrupted, contributes to the development of intestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and hyper-reactivity to food components [3,4].

The adaptability of intestinal macrophage and DC functions to maintain immune homeostasis and provide host defense depends on accurate molecular sensors that activate or suppress appropriate pathways according to microenvironmental cues [5–7]. The environmental factors that “educate” intestinal macrophages and DCs include exposure to a vast array of molecules and metabolites from the diet [8] and from the trillions of commensal bacteria [9], as well as to a diverse conjunct of other host-derived bioactive molecules [2]. In addition, the different physical niches along the small intestine and colon create specific microenvironments for the differentiation of macrophage and DC populations with specialized functions to respond to the local requirements. These subpopulations of macrophages and DCs are present in niches throughout the intestine, but are primarily located in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), which are inductive sites for inflammatory or tolerogenic immune responses, comprising the Peyer’s patches (PPs) and isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs) [1]. Both PPs and ILFs are covered by the follicle associated epithelium (FAE), which contains microfold (M) cells that sample antigens from the intestinal lumen of the small intestine and deliver them to DCs, which then activate cognate naïve T and B lymphocytes at segregated T (interfollicular areas) and B cell regions (follicles with germinal centers), respectively [10–12].

In this review, we provide an overview on the characteristics, origins, and functions of intestinal macrophages and DCs, highlighting the intestinal microenvironmental factors that influence their development and functions during homeostasis.

2. Intestinal macrophages

The intestine contains the largest pool of macrophages in the body [13]. The intestinal macrophage pool is comprised of different subpopulations that occupy distinct niches with a variety of compartmentalized functions and morphologies. Three major populations were initially identified in murine and human intestines: the lamina propria macrophages (LpMs), the Peyer’s patches macrophages (PpMs), and the muscularis macrophages (MMs), although other functionally distinct populations have also been described in the submucosal and serosal layers [14–17].

2.1. Populations of Intestinal Macrophages

2.1.1. Lamina propria macrophages

LpMs are the most abundant and characterized population in the gut. They are located underneath the epithelial layer and within the villi, where some LpMs are in close proximity to the gut lumen. At steady state, the majority of LpMs in the small intestine, and a large proportion in the colon are characterized as F4/80+CD64+CX3CR1hiMHCIIhiCD11chi cells [13,18–22]. F4/80+CD64+CX3CR1hiMHCIIhiCD11clo cells make up approximately 50% of LpMs in the colon [21]. LpMs play a critical role in regulating intestinal homeostasis and immune defense. In addition to maintaining both epithelial barrier integrity and the intestinal stem cell niche, LpMs phagocytose apoptotic and senescent cells, clear pathogenic bacteria and contribute to tolerance to commensal microbiota and dietary antigens [23–27].

The homeostatic and immune defense functions of CD11chi LpMs are associated with their strategic position underneath the epithelial layer, as mentioned above, which allow these cells to capture dead and dying epithelial cells and invading pathogens, and to sample luminal antigens and microbes after transcytosis across the epithelium or via transepithelial dendrites (primarily in the small intestine) under physiological conditions. However, the ability of LpMs to sample antigens through transepithelial dendrites under physiological conditions has been challenged by a number of studies that have reported that transepithelial dendrites increase after Toll-like receptor (TLR)-stimulation and following intestinal infection, which may represent a mechanism of antigen sampling during infectious/inflammatory conditions [28–30]. Furthermore, subepithelial macrophages in the distal colon were described as having “balloon-like” protrusions (BLPs) that penetrate at the base of the epithelium, occupying the intercellular space, where they sample fungal metabolites/toxins in the fluids absorbed through epithelial cells rather than directly in the lumen [31].

Despite their phagocytic and bactericidal properties, LpMs do not elicit an overt inflammatory response to commensals or dietary antigens. Instead, they produce anti-inflammatory cytokines, which contribute to immune tolerance to oral antigens and commensal microbes [24,27,32,33]. This feature is mainly attributed to the anti-inflammatory IL10/IL10R axis in both humans and mice [32,34], since LpMs release high levels of IL-10 in the presence of microbiota, which promotes the expansion of Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells in the lamina propria (LP). As a result, IL-10 produced by both Treg cells and LpMs work together to prevent aberrant intestinal inflammation in mice [35–38] and in humans [39,40]. Furthermore, LpMs contribute to oral tolerance by transferring antigens to CD103+ DCs, which then migrate to mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) to induce antigen-specific Treg cells [25,41–43].

Two subtypes of LpMs have been recently identified in the colon. One subtype locates near the tip of the crypt and is characterized by the expression of CD11c and by having pro-inflammatory functions; the other subtype resides close to the base of the crypt and is characterized by the expression of CD206 and CD169 and by possessing tissue repair functions. Importantly, due to their perivascular location, both LpM subtypes can sample antigens from the blood. The CD206+CD169+ LpMs may be similar to, or overlap with submucosal CX3CR1+ perivascular macrophages, which are cells that adhere to the mucosal vasculature and form a network to help maintain vascular barrier integrity and repair and prevent bacterial translocation to the blood [44].

Finally, a recent study has shown a detailed characterization of LpMs from adult human colon by applying single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) and multicolor immunostaining in situ. It was shown that the LpM population contains multiple transcriptionally stable macrophage subtypes that coexist in the tissue. LpM subtypes are clustered into two groups: those with pro-inflammatory properties due to the upregulation of inflammatory genes including IL1B, IL1A, IL6, IL23A, CXCL2, CXCL3, CXCL8 and IFNG-inducible genes; and those with high phagocytic and antigen-presenting properties with high expression levels of HLA class II, wound healing, receptor-mediated endocytosis, and apoptotic cell clearance related genes. These functions are consistent with their strategic position in the subepithelial region of the gut [45].

2.1.2. Peyer’s patches’ macrophages

PpMs are a heterogeneous population of macrophages found at an immune inductive site and that have different phenotypes and functions as compared to the broad population of intestinal macrophages located in effector areas such as the LP and epithelial layer [46]. PpMs lack the expression of classic intestinal macrophage markers including F4/80, CD169, CD206, and CD64 [17] but share key markers with conventional DCs (cDCs) such as CD11c, MHCII [17,47], CD11b, and SIRPα [48].

PpMs are found in PPs’ dome and dome-associated villus areas. Dome PpMs are large, long-lived and autofluorescent cells, that express CX3CR1, MerTK, CD4, SIRPα, BST2 and lysozyme. BST2 and lysozyme are hallmarks of dome macrophages, since their dome-associated villus counterparts express little or none of these molecules [17,49]. Furthermore, dome PpMs are divided into three subtypes with distinct functions and anatomic localizations, suggesting an important regional specialization within the PPs.

Two of these dome PpM subtypes are characterized by the expression of CX3CR1hiCD11chiMHCIIloCD11b+CD4+MerTk+BST2+Lysozyme+ and are named LysoMacs. Unlike LpMs, LysoMacs do not play a role in tolerance induction in the small intestine likely because of their inability to secrete IL-10 even upon stimulation and because their decreased expression of the IL-10 receptor (Il10ra) [17]. LysoMacs are further subdivided into LysoMacTIM4− and LysoMacTIM4+ [17,49,50]. LysoMacs TIM-4− are primarily located in the upper part of the dome at the subepithelial region (SED), where they interact with M cells to sample antigens to present and induce T cell activation, and to promote antimicrobial defense [17,49,51,52]. LysoMacs TIM-4+ are predominantly present in the lower dome’s interfollicular region (IFR), where they are involved in the control of adaptive immune responses via apoptotic T cell clearance [17].

Finally, the third population of dome PpMs are the tingible-body macrophages (TBM), located in the germinal center of PPs, representing the only phagocytes in these sites. TBMs do not express CD11c, CD11b or MHCII and are characterized by the expression of CX3CR1, SIRPα, lysozyme and CD4 in addition to the apoptotic cell receptors MerTk and TIM-4, making them important cells to clear apoptotic B cells and to promote immune regulation [17,49,53].

2.1.3. Muscularis macrophages

MMs are characterized as CX3CR1hiCD163hiMHCIIhiCD11clo cells [20,54], and are located in the myenteric plexus, where they adopt either a stellate or bipolar morphology. They are also present, though at lower numbers, in other layers of the muscularis externa such as the circular and longitudinal muscle layers and within the serosal layer [15,16]. MMs display a tissue-protective phenotype with an upregulation of M2 genes including Arg1 and Cd163 [16] to establish a reciprocal functional crosstalk with enteric neurons that ultimately leads to the regulation of intestinal motility at steady state [15,54–57]. Specifically, MMs secrete the bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2) that binds to its receptor BMPR expressed on enteric neurons to regulate gastrointestinal motility. In a positive feedback loop, following BMP2-BMPR signaling, enteric neurons secrete colony stimulatory factor 1 (CSF1), a growth factor required for macrophage development, that also stimulates BMP2 secretion by MMs [16,54]. Moreover, the production of BMP2 by MMs and CSF1 by enteric neurons are regulated by the gut microbiota [54,55].

The crosstalk between MMs and enteric neurons is also important during enteric infections. By using different mouse models of intestinal bacterial infection, Matheis et al. have demonstrated that a neuroprotective program involving the arginase 1-polyamine axis in MMs was upregulated through β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) signaling [58]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that parasitic infections also lead to polarization of MMs towards a protective phenotype to prevent neuronal loss [59].

Human MM subtypes are evenly distributed throughout the muscular compartment, but they are primarily located near neurons and vessels. Single cell RNA-seq analyses have revealed that most MMs can be divided into two groups: one that upregulates genes associated with immune activation and angiogenesis, such as IL1A, IL1B, CXCL chemokines, type I– and IFNG– mediated signaling pathways, and MHC class I and class II– mediated antigen processing and presentation; and another that upregulates genes associated with neuronal homeostasis, including receptor-mediated endocytosis, synaptic pruning, apoptotic cell clearance, and the Schwann cell-associated proteins PMP22 and EMP1 [45].

2.2. Origin of resident intestinal macrophages

Until recently, it was widely assumed that intestinal macrophages, initially derived from embryonic cells, were replaced by incoming monocytes at around 3 weeks of age, and that the intestinal macrophage pool relies solely on the replenishment by circulating monocytes. In fact, LpMs, including those that populate the villi, and intestinal macrophages within the submucosa, as well as the two subsets of PpMs Lyso Macs require a high level of constant replenishment by circulating monocytes in adult mice during homeostasis and inflammation. Unlike LpMs and LysoMac, the origin and lifespan of TBM remain unknown [13,17,22,24,44,60]. However, based on studies using flow cytometric and cell fate-mapping analyses, it is now clear that the gut also harbors a significant population of macrophages derived from embryonic tissue- or early bone marrow-derived precursors that are long-lived and self-maintained throughout adulthood [44,61–64]. These embryonically derived macrophage populations inhabit specific intestinal niches, distant from the lumen, such as the muscularis externa (circular muscle, myenteric plexus and longitudinal muscle), and the submucosa. It has been demonstrated that a large proportion of MMs are constituted by these early-seeded macrophages [15,63]. Moreover, in a recent study, Grainger and colleagues used TIM-4 and CD4 markers to characterize three subtypes of LpMs with different replenishment rates from blood monocytes. They found that TIM-4+CD4+ LpMs are locally maintained independently of monocytes, but TIM-4−CD4+ LpMs are slowly replenished by monocytes. Together, these two subtypes account for the vast majority of macrophages in the gut. The TIM-4−CD4− macrophages were the only subtype with a substantial turnover from monocytes [63]. Finally, like for mice, similar ontological heterogeneity of intestinal resident macrophages and the concept that long-lived macrophages occupy specific niches and may be functionally distinct from blood-derived cells have been also found in human studies [14].

2.3. Influence of intestinal niches on resident macrophage phenotype and function

Although having incontestable influence, cellular ontogeny and cell-intrinsic factors are not sufficient to explain the differences in transcriptional profiles and functions displayed by tissue-resident macrophages [6,65]. Instead, there has been experimental evidence showing that the local microenvironment is crucial for imprinting tissue-specific macrophage functions [66], providing signals necessary for the maturation into a functional macrophage population from any precursor [6,67]. While the specific factors in the intestinal that influence macrophage differentiation and identity are not completely understood, it is clear that differences between the small and large intestine vilus/crypt-lumen microenvironments can affect the functional specialization of these macrophages [68]. This includes differences in mucus thickness, pH, cytokine concentrations, apoptotic cell frequency, dietary metabolites, and microbial loads. Furthermore, a recent study that investigated human intestinal macrophages at a single cell level has suggested that circulating monocytes enter the crypt area via postcapillary venules, and some cells rapidly differentiate into different types of pro-inflammatory macrophages whereas others migrate to the subepithelial region. There, macrophages downregulate pro-inflammatory genes and upregulate the expression of genes related to endocytosis, antigen presentation, and wound healing, to maintain mucosal barrier integrity with minimal collateral damage [45].

2.3.1. Immunologic regulation of macrophages in the gut

The most studied immunomodulatory factor in intestinal LP is the IL-10. Despite the often reported importance of IL-10 produced by macrophages in the regulation of intestinal immune homeostasis, IL-10Rα signaling in CX3CR1hi macrophages is critical for their anti-inflammatory profile during homeostasis. It has been reported that the lack of the IL-10-IL-10R tolerogenic axis resulted in the expression of an array of pro-inflammatory cytokines by intestinal macrophages that ultimately led to deleterious T cell responses and to the development of spontaneous colitis in mice [38,40,69]. Likewise, impaired differentiation and induction of anti-inflammatory functions in monocyte-derived macrophages were observed in a very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in patients harboring loss of function mutations in IL10RA and IL10RB [40]. Exacerbated inflammatory responses in the absence of IL-10R signaling may be due to a failure in downregulating STAT3, TREM-1, and STAT1 pathways that control macrophage activation, and also by an increase in chromatin accessibility to pro-inflammatory genes, which is normally controlled by IL-10-dependent epigenetic remodeling [38,70]. Conversely, PP LysoMacs have a distinctive transcriptome with a lack of IL-10 production [17] and downregulation of Il10ra gene [38,71] and IL-10 signaling-dependent genes including those involved in arachidonic acid metabolism and in extracellular matrix modeling, binding, or degradation [17]. As a result, PP LysoMacs are not involved in anti-inflammatory responses, but rather retain the ability to respond to infection and to promote inflammation. These findings suggest an important role of the microenvironment in modulating macrophage phenotype and function, since PP LysoMac subtypes are derived from the same monocytic lineage, as confirmed by the use of parabiosis in mice [17].

TGFβR signaling has also been reported to be indispensable to monocyte-macrophage differentiation and tolerogenic functional adaptation during intestinal lamina propria homeostasis, due to their role in modulating the expression of CX3CR1, IL-10, and αvβ5 integrin. In addition, TGFβR signaling on macrophages limits monocyte recruitment to the mucosa, which is mechanistically independent of IL-10 [72]. Accordingly, another study has demonstrated that TGF-β regulates Runt-related transcription factor 3 (RUNX3) expression, specifically in intestinal macrophages [6]. Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (efferocytosis) also induces TGF-β secretion by macrophages, which then inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory mediators through an autocrine/paracrine mechanism in vitro [73]. Indeed, it has been shown that two distinct populations of CD11b+ LpMs from the small intestine cleared apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), which resulted in the upregulation of cell-type-specific anti-inflammatory gene signatures and in the downregulation of TLR2. Some of the induced genes overlap with susceptibility genes for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), suggesting that efferocytosis by intestinal macrophages helps prevent unwanted inflammatory or autoimmune responses [74] (Figure 1).

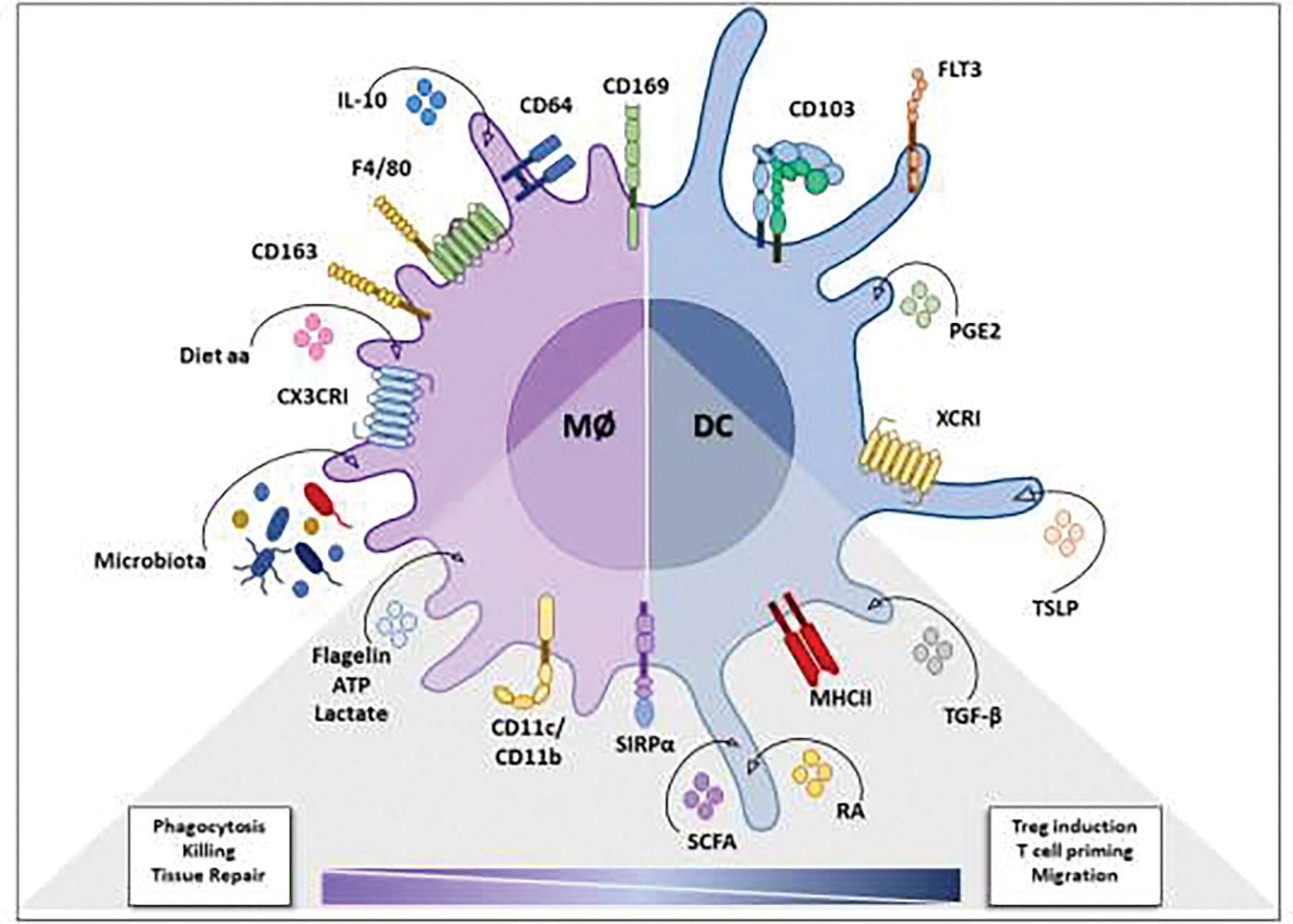

Figure 1. Microenvironmental factors affecting intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells under homeostatic conditions.

Identifying surface molecules and local mediators that drive the differentiation and/or maintain the phenotype and function of intestinal macrophages (microbiota, IL-10, and amino acids from the diet; receptors: CX3CRI, CD163, F4/80, CD64, CD169) and dendritic cells (TLSP and PGE2; receptors: CD103, FLT3, XCRI). The gray triangle identifies molecules (flagellin, ATP, lactate, SCFA, RA and TGF-β) and receptors (CD11c, CD11b, SIRPα and MHC-II) common to the effector and tolerogenic functional modulation of intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells. TGF-β: transforming growth factor β; SIRPα: signal regulatory protein α; RA: retinoic acid, SCFA: short-chain fatty acids; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; Diet aa: Diet derived-amino acids; IL-10: interleukin 10; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; TSLP: thymic stromal lymphopoietin protein.

2.3.2. Dietary-dependent regulation of macrophages in the gut

The intestinal microenvironment is enriched in diet-derived antigens and microbiota-secreted metabolites that play an important role in maintaining host homeostasis by modulating the immune system [75]. The luminal concentration of diet-derived immunomodulators depends on dietary intake and on metabolic degradation, which is spatially restricted to many nutrients, contributing to the regional specialization of macrophages. For example, LpMs can sample luminal contents directly, which makes them less dependent on nutrient absorption and availability in the LP [76]. Moreover, the small intestine has a higher capacity to absorb nutrients and has a reduced density of microbiota compared to the colon. Thus, due to these spatial particularities, diet-derived nutrients and microbial metabolites may be particularly important exogenous modulators of macrophage functions [77,78].

Some key nutrients have been described as immunomodulators of macrophage function, including amino acids, vitamin A, aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands, and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [77]. Accordingly, in a murine model of enteral nutrient deprivation, by giving mice total parenteral nutrition (TPN), a reduction in the frequency and replenishment of a population of monocyte-derived F4/80+CD11b+ macrophages, but not of non-monocytic precursor-derived CD103+ DCs was observed in the small intestine. Furthermore, the authors found a significant decrease in IL-10-producing macrophages in the TPN-fed mice. In contrast to colonic macrophages, the reduction in frequency and replenishment of and IL-10 production by these macrophages in the small intestine were dependent on the diet, but independent of the microbiota [78]. Consistent with this, the dietary administration of the amino acid histidine reduced colitis in IL-10−/− mice [79] and inhibited the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 through the suppression of NF-κB activation [79,80]. Finally, it has been reported that arginine, glutamine and tryptophan can increase macrophage phagocytic activity [81].

Vitamin A metabolites such as retinoic acid (RA) are absorbed and maintained at high concentrations in the small intestine [82], where they function as immunomodulators to imprint and maintain tolerogenic properties of macrophages. Particularly, a recent study has shown that dietary intake of vitamin A/RA was required to downmodulate pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-12 and TNF-α and to upregulate the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. In addition, RA increased dectin-1 expression on macrophages from the small intestine. Importantly, activation of dectin-1 can provide a rapid functional switch of macrophages from a tolerogenic to a pro-inflammatory and antimicrobial profile [83].

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is widely expressed in the intestinal microenvironment, and its activation by dietary components and microbiota-derived products results in barrier-protective effects as well as in the modulation of immune cells in the gut [84–86]. A recent study has shown that the deletion of AhR in macrophages increased mouse susceptibility to TNBS-induced irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and that decreased AhR expression in macrophages of IBS patients was associated with the disease severity [87]. Mechanistically, the conditional depletion of AhR in CD11c+ intestinal macrophages/DCs resulted in a dysfunctional epithelial barrier, which was associated with a more aggressive chemically-induced colitis in mice, suggesting that luminal ligands of AhR have an important role in modulating macrophage functions and mucosal immunity and homeostasis [88].

The colonic lumen is abundant in microbes and colonic macrophages are modulated by the microbiota and their products. SCFAs, such as butyrate, are produced during fermentation of indigestible dietary fiber by the colonic microbiota and have important effects in macrophage function [89]. It has been demonstrated that butyrate and niacin induced IL-10 secretion by murine intestinal macrophages via GPR109a receptor activation [90]. Moreover, Powrie and co-workers have found that butyrate imprints a non-inflammatory antimicrobial program in intestinal macrophages, which is associated with a reduction in mTOR kinase activity, through histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) inhibition. In addition, oral administration of butyrate increased microbicidal activity of intestinal macrophages, which increases resistance to enteropathogens, suggesting that butyrate may represent a strategy to reinforce intestinal host defense while minimizing tissue damaging inflammation [91]. Consistent with this, it has been reported that low amounts of SCFA are associated with several inflammatory diseases [89]. Indeed, depletion of SCFAs during antibiotic treatment led to hyperresponsiveness of murine colonic macrophages along with a long-term increase in inflammatory T helper 1 (Th1) cell responses and sustained dysbiosis. Importantly, this effect was prevented by supplementing mice with butyrate following antibiotic treatment [92]. Lastly, another study has reported that the intake of SCFAs induced long-lived Tim4+CD4+ colonic macrophages [92] (Figure 1).

2.3.3. Microbiota-dependent regulation of macrophages in the gut

The immune system-microbiota interactions are crucial to the gastrointestinal tract, playing a role in tissue length, fecal pellet frequency and consistency, villus thickness, cellular proliferation, Paneth cell granule’s development, and the production of mucus and antimicrobial peptides [93–97]. In addition, the gut microbiota modulates the development of the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue, which contributes to homeostatic numbers of innate and adaptive immune cells in the gut [98]. Likewise, intestinal immune cells modulate the microbiota composition [99]. Recently, Chikina and co-workers found that during homeostasis, CD11chigh subepithelial macrophages in the distal colon have BLPs that penetrate at the base of the epithelium to sample fluids absorbed through epithelial cells in the intercellular space. This subset of macrophages instructs epithelial cells to stop absorption when fungal metabolites/toxins are overloaded in fluids, which prevents epithelial cell poisoning and death that might compromise epithelium barrier integrity [31].

The knowledge obtained from germ-free (GF) mice has been pivotal to understanding the importance of the interplay between the gut microbiota and the host immune system on shaping macrophage populations. It has been reported that GF mice have a reduction in both monocyte-derived and self-replicating macrophages as compared to specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice [13,21,63]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that the microbiota is critical for the development of two colonic macrophage populations – CD11c+CD121b+ and CD11c−CD206hi, in which frequencies were restored 6 weeks following the co-housing with SPF mice. By investigating CD11c+ and CD11c− colonic macrophage transcriptomes at a single-cell level, Kelsall and co-workers found that the microbiota modulated several gene pathways, including those involved in metabolism, host defense, and adaptive immunity [100]. Depletion of the microbiota by antibiotic treatment or by using GF mice has been shown to be crucial to imprint a pro-inflammatory signature in colonic macrophages from IL10R deficient mice [69], and to reduce IL-10 production by macrophages, which led to an increase in Th1 cells [37,101]. Interestingly, the spatial distribution of perivascular macrophages has been reported to be modified in GF and antibiotic-treated mice in both the small intestine and colon, independently of the TLR/MyD88/TRIF pathway [19].

The diversity of the microbiota changes throughout the extension of the gut with microbial loads increasing from the small intestine to the colon [102]. Thus, several distinct niches with different microenvironments harbor different members of the microbiota in murine and human GI tract [102–105], which, in turn, can modulate the differentiation and development of macrophages. Consistent with this, it has been reported that the adherent bacterium Clostridium butyricum suppresses the antimicrobial program by inducing IL-10 production by macrophages [101] (Figure 1).

3. Dendritic cells

In vertebrates, the immune system contains differential traits such as the improved ability to recognize and respond to a variety of antigenic determinants due to the rearrangement of genes encoding the antigen binding receptor in lymphocytes [106]. Besides this sophisticated mechanism of acquired immunity, DCs emerged as a new class of mononuclear phagocytes that ensure the synergic activity of both arms of the immune system. Through efficient presentation of peptides in MHC molecules, DCs became the crucial bridge between innate and adaptive immunity by initiating and guiding T cell responses [107]. DCs are professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) that play a critical role in regulating tolerance and immunity by restraining pathological autoreactivity and by stimulating T cells to eliminate pathogens and tumors. During antigen presentation, DCs release cytokines and provide co-stimulatory signals that activate naïve T cells and license their effector capabilities [108].

3.1. Populations of Intestinal Dendritic Cells

Mononuclear phagocytes are heterogeneous cell populations that share many phenotypic and functional features. However, new genetic tools and the identification of novel biomarkers have allowed DCs to be distinguished from resident macrophages and monocyte-derived cells [109]. There are two major DC populations: cDCs and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) [110], both of which emerge from bone marrow progenitors [111,112]. In the bone marrow, the monocyte/DC progenitor give rise to the common DC progenitor [113], which then originates the pDCs or the cDC precursors such as the pre-cDC1 and the pre-cDC2 [114]. Pre-cDCs give rise to fully developed DCs within the tissues, where they acquire specialized features and functions [115]. The signaling pathways involved in DC ontogeny and differentiation remain under debate. Using a combination of techniques, Dress and coworkers concluded that pDCs developed in the bone marrow from a lymphoid progenitor and differentiate independently of the myeloid cDC lineage [116]. Conversely, a recent study proposes a common origin for pDCs and cDCs, and suggests a novel development pathway in which pDCs and cDC1s share a clonal relationship [117].

DCs from different intestinal compartments are related to distinct T cell differentiation and cytokine secretion, and there are distinct tolerogenic DC subsets in small intestine and colon [118]. Moreover, each DC subtype expresses different transcription factors, has different activation states, and plays distinct functional roles in the GALT and gut-draining MLN. pDCs can be identified by the expression of B220, Siglec-H, and Bst2 on CD11c+MHCIIint cells [119] whereas cDCs are characterized by the expression of high levels of MCHII, CD11c and sometimes CD26, and by the lack of CD64 and F4/80 markers [120].

One cDC1 and two major cDC2 subtypes are found in intestinal tissues: cDC1 are CD11chiMHCIIhiCD103+CD11b−XCR1+, and cDC2s are CD11chiMHCIIhiCD11b+ SIRPα+ and either CD103−, or CD103+ [114]. cDC1s are dependent on the transcription factors IRF8, BATF3, and ID2 [121] and cDC2s on IRF4 and ZEB2 [122]. LP cDC2s that express CD103 and CD11b are prominent in the small intestine, but less so in the colon [123,124]. The cDC subtypes also exhibit differential molecular and functional signatures. cDC1s express higher levels of several tolerogenic factors, including retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH2) and β8 integrin, which is involved in TGF-b activation, than cDC2s [125]. Both LP cDC1s and cDC2s can induce Foxp3+ Treg cells, however, while CD103+CD11b+ cDC2s are more efficient in this task, CD103− cDC2s prime T cells to a more immunogenic phenotype [126,127]. Many functions and characteristics of cDCs in vivo have been demonstrated using constitutive knockout strains, however cDC2 are a functional and phenotypically heterogeneous population and results obtained from some of these models should be interpreted with caution. Some strategies used for this purpose have been recently described and reviewed elsewhere [128,129].

In the gut, cDC subtypes are distributed along the intestinal epithelium, throughout the intestinal LP, and within niches in PPs and ILFs [130]. In PPs, for example, cDC1s are mostly found in the interfollicular areas, whereas cDC2s are found in both the subepithelial dome and in the interfollicular regions, depending on their maturation status. Immature cDC2s are mostly found in the subepithelial dome, where they are prone to acquiring luminal antigens. Fully mature cDC2s however, are primarily found in the interfollicular area, where they are perfectly positioned to deliver antigens to interfollicular naïve T cells [130].

Additional functionally specialized monocyte-derived cells are present in the gut within unique niches and, during active inflammation, can activate naïve T cells though to a less extent than bona-fide cDCs. For example, in the PPs, monocyte-derived cells that express lysozyme, and thus termed LysoDCs, reside in the subepithelial dome of PPs, where they sample intestinal microorganisms and trigger T cell responses in addition to expressing CX3CR1, a typical macrophage marker. However, these cells do not express F4/80, CD64, or Zbtb46, a transcription factor specific to cDCs [46]. Upon stimulation, DCs are believed to mature and change their functions, reducing antigen uptake, improving antigen processing and presentation and improving migration. The specialized PP-DC subtype is primarily located in the SED at steady state and does not have its phagocytic ability impaired after TLR7 stimulation. In fact, TLR7 activation triggers CCR7 upregulation and the migration of PP-DCs to the periphery of the IFR, where they strongly interact with T helper cells [131]. In addition, during active intestinal inflammation, monocyte-derived cells with the capacity to present antigen to naïve T cells referred to as inflammatory monocytes and macrophages and are distinguished by their expression of CD11c, CD64, MerTk, and by high levels of MHCII [21,126,127].

The dynamics of lymphatic drainage in the small intestine and colon has been recently clarified and demonstrates a high level of anatomical adaptation with functional implications to the immunological activity of cDCs [132]. The balance between tolerance and inflammation in the gut is shaped in part by the preferential distribution of each cDC lineage to different portions of the gut. It is important to highlight that lymph nodes that drain the duodenum harbor cDCs with higher expression of tolerogenic factors and lower expression of inflammatory cytokine receptors than cDCs from lymph nodes that drain the ileum and colon [125]. Conversely, the lymph nodes that drain the distal colon and rectum - caudal and iliac lymph nodes - contain CD103−CD11b+ cDC2 capable of producing PGE2 and favoring tolerance in the gut [133].

A hallmark of cDCs is their ability to migrate to the MLN after taking up antigens in the intestinal LP. The CCR7 chemokine receptor and its ligands CCL19 and CCL21 produced by the lymphatic endothelium and by the MLN stroma direct the migration of tissue DCs both at steady state and during inflammation [134]. A classic demonstration of the dependence of this physiological migration of DCs from the intestinal LP to the draining lymph nodes is the triggering of the fundamental phenomenon of oral tolerance [43]. During this migration, dendrite elongation occurs, which is followed by increased antigen processing as a result of elevated expression of MHC, costimulatory and adhesion molecules. Once in the lymph node, fully matured cDCs prime naïve T cells into differentiated subtypes [135]. All cDC subpopulations from the small intestine have been shown to migrate to the MLNs, although CD103+ cDC1s appear to have the highest capacity. PP LysoDCs, on the other hand, once activated, express CCR7 and migrate to IFR to interact with T cells, similarly to dome-associated villus cDCs [125]. Stimulation of cDCs by orally administered TLR agonists induces a high recruitment of LP cDCs to the MLN. This effect depends on an indirect activation via type I interferon or TNF-α released by pDCs. In contrast, at steady state, TNF-α is not required for migration of CD103+cDCs [136]. Interestingly, the impaired TLR signaling in MyD88−/− mice interferes with the proper migration of LP cDCs to MLN. Despite the attractive hypothesis that continuous low-level activation by bacterial components is necessary for steady state cDC migration, MyD88-mediated migration is microbiota-independent [137].

Intestinal cDC populations appear to have both common and unique functions when compared to cDCs from other tissues. While cDC2s can drive Th2 and Th17 differentiation both in vitro and in vivo, cDC1s are specialized in driving Th1 responses and are the most capable cDC population to cross-present soluble or epithelial cell derived antigens to CD8+ T cells, a phenomenon that can lead to either regulatory or effector responses [138,139]. Unique to intestinal cDCs is their ability to direct Treg differentiation [140] and to drive the expression of intestinal homing markers on T cells [141,142]. In this regard, both CD103+ cDC1 and cDC2 populations and CD103− cDC2s in the LP and MLN can promote Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation and induce the intestinal homing receptor CCR9 due to their ability to secrete TGF-β and RA [143–146]. Furthermore, studies using mice lacking specific cDC subpopulations [see 111] have indicated that cDC1s have specific effects on the differentiation and/or survival of Th1 cells in vivo (as seen in vitro) likely because of their ability to secrete IL-12. In addition, it has recently been demonstrated that cDC1s are involved in the induction of Foxp3+CD8+ Tregs and local cross-tolerance to IEC-derived tissue-specific antigens in the gut mucosa via PD-L1 expression as well as TGF-β and RA production [138]. Moreover, cDC1 deficient mice also have deficiencies in CD4+ and CD8+ LP T cells and CD8αα and CD8αβ intraepithelial cell lymphocytes (IEL), consistent with their proposed roles in cross-presentation and possibly in driving homing receptors on T cells due to their high production of RA. In contrast, mice lacking cDC2 populations have fewer Th17 cells in the gut, which is consistent with their production of IL-6, IL-23 and TGF-β, crucial cytokines involved in Th17 differentiation. cDC2s have been also shown to be important for Th2 cell responses in vivo following helminth infections [147]. Finally, unique to intestinal cDCs is their ability to induce IgA-producing B cell differentiation in PPs that helps restrict microbial penetration in the mucosa [148].

In the small intestine, an intriguing division of labor between cells has been proposed. Goblet cells were shown to act as passages, delivering soluble antigens from the intestinal lumen to underlying LP-DCs. The subset of LP-DC initially identified was the CD103+ DCs [149], but now, goblet cell associated passages are recognized as a common route for dietary antigen delivery to LP-APCs to facilitate oral tolerance development and maintenance [150].

In contrast to cDCs, pDCs have a plasma cell-like morphology and do not migrate via lymph and, unless activated, are not believed to contribute significantly to antigen presentation and T cell priming [116]. They are innate effector cells that, upon activation by pathogen-derived nucleic acids, produce large amounts of type I interferon (IFN), release inflammatory cytokines [151,152] and recruit cytotoxic NK cells [153]. Most tissues, at steady state, contain a very low frequency of pDCs, though these cells are relatively abundant in the gut, where they represent up to 1% of total intraepithelial and LP cells [154]. However, the limitations of the isolation techniques applied to the separation of LP and intraepithelial cells make it difficult to determine their exact location since they could originally come from isolated lymphoid follicles. In PPs, pDCs occupy sites of initial antigen uptake and are found close to T cell zones [155]. Intestinal pDCs have unique traits, including the reported ability to drive Treg differentiation [156] and to induce IgA production in a T cell-independent fashion [157]. Finally, pDCs in the liver have been shown to contribute to oral tolerance induction likely by promoting T cell anergy and deletion [158].

3.2. Influence of intestinal niches on DC phenotype and function

The phenotype and function of different cDC populations depend on cell lineage, but also on factors in the intestinal microenvironment. cDC populations from different lineages within a common microenvironment can share certain functions, and yet differ in others. Overall cDC populations have some degree of functional plasticity to allow them to respond appropriately to changes in or threats to their ecosystem [159,160]. Although most of the knowledge on DC conditioning is related to sensing signals through specific pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokine/chemokine receptors [161–163], new endogenous and exogenous factors such as metabolic products of commensal microbiota, as well as vitamins, hormones and host metabolites can remodel immune activity, including cDC function.

An immune-mediated mechanism of nutrient absorption involves lymphotoxin-β receptor signaling in the population of CD11c+ mononuclear phagocytes in cryptopatches and ILFs. These cells are believed to be an unique subtype of intestinal cDCs, closely related to cDC2 (CIA-DCs) that, upon ILC3 conditioning by lymphotoxin-α1β2 signals, express genes associated with immunoregulation and become the major cellular source of IL-22 binding protein (IL-22BP). As the IL-22:IL-22BP module controls the expression of epithelial lipid transporters, it may constitute an unconventional function of mononuclear phagocytes at barrier surfaces to control nutrient balance [164]. The microenvironment established in the PP SED region favors he expression of IL-22BP protein by DCs. IL-22BP expressed by SED-DCs (CD11chighCD11b+CD8α−) is important to facilitate antigen uptake to the PPs, such as internalization of pathogenic and commensal bacteria, by negatively regulating IL-22 signaling in follicle-associated epithelium [165].

Among endogenous local factors that influence intestinal cDC differentiation and function is the RA [35]. IECs, stromal cells and even DCs produce RA from vitamin A (retinol), using retinol metabolizing enzymes, including the rate limiting RALDHs. RA induces the upregulation of RALDH2 in CD103+ cDC1s and cDC2s, drives the expression of the gut homing α4β7 integrin on T and B cells [7,166], and contributes to Treg cell differentiation [140,143,144,167]. In addition to RA, endogenous IL-4 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) support the expression of RALDH2 in LP-DCs [168].

Dietary glucose is also critically required to establish RALDH2 activity in CD103+CD11b+ cDCs from the small intestine [169]. Curiously, a previous study has shown that exposure of cDCs to different glucose concentrations can suppress cDC inflammatory cytokine responses to LPS and can suppress DC-induced T cell activation [170], though how this relates specifically to the gut remains unclear. As nutrient levels vary in intestinal microenvironments and with different diets, glucose and other dietary factors likely have significant roles in affecting overall immune cell function.

Stromal cell populations have an important influence on cell function in the gut at least in part by releasing RA, but also by producing TGF-β and PGE2. Notably, PGE2 has been shown to inhibit IL-12 production by cDC as well as type 1 interferon production by pDCs [171]. PGE2 also acts as a RALDH repressor and thus suppresses the differentiation of RA-producing DCs in both mice and humans [172], though the overall effect of PGE2 on mucosal cDC function is not yet clear. On the other hand, TGF-β signaling is essential for driving the differentiation of CD103+ cDC2s from CD103− cDC2s, resulting in the ability of small intestine LP cDC2s to drive Foxp3+ Treg and Th17 cell differentiation [173]. Cellular sources of TGF-β includes epithelial cells, stromal cells, and intestinal macrophages, as well as Foxp3+ Treg cells [174].

Another endogenous factor that influences cDC function in the gut is the exposure to mucin glycoproteins, particularly mucin 2 (MUC2). Uptake of MUC2 by cDCs in the intestinal LP has been shown to affect their expression of inflammatory but not regulatory cytokines through effects on β-catenin signaling and inhibition of NFkB activation [175]. Similarly, a subpopulation of CD103+CD11b+ cDC2s has been shown to migrate into the intraepithelial cell compartment where they maintain an immature phenotype with limited ability to activate T cells, an effect caused by the exposure of these cells to MUC2 [176].

Recent findings have highlighted the role of the metabolism and the endocrine status on immune cell function and homeostasis. One clear example of this regulation is the immunoregulatory properties triggered by the binding of vitamin D to its receptor VDR, which is expressed on numerous cell subtypes, including cDCs [177]. The active form of vitamin D - 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VD3) - can shape cDC programs related to anti-inflammatory T cell responses [178]. Vitamin D deficiency in mice leads to exacerbated Th1 and Th17 responses [179] and to reduced frequencies of tolerogenic DCs and Foxp3+ Tregs [180]. Vitamin D restrains Th1 and Th17 activation and inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines in the gut, which helps prevent pathological inflammation and control the microbiome to maintain tissue tolerance [178]. Interestingly, the vitamin D receptor was found to be highly expressed in the distal portion of the small intestine, where vitamin D signaling promotes innate immunity [181]. Furthermore, the effect of VD3 on the cDC profile may differ according to each subtype of cell. This has been demonstrated by ex vivo studies using cDCs extracted from human MLN, in which CD103− but not CD103+ cDCs acquired a high level of RALDH activity in response to GM-CSF, RA and VD3, indicating that vitamin D contributes to the induction of RA in human intestinal DCs [182]. Thus, vitamin D appears to selectively affect DC subpopulations in specific tissues and VDR engagement drives signaling that can affect maturation, migration, cytokine and chemokine production by these cells and may serve as a natural inhibitory mechanism that confers immunoregulatory properties to both cDCs and pDCs [183,184].

Other physiological factors may also promote tolerance. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) may contribute to the anti-inflammatory status of monocyte-derived DCs in vitro by downregulating costimulatory molecules, decreasing the production of TNF-α and IL-6 and by increasing the production of IL-10 after LPS stimulation, which favor Treg cell differentiation both in vitro and following in vivo injection in mice [185]. Another hormone (and its receptor) that is present in the gut is the oxytocin [186]. Increased levels of oxytocin have been detected in the serum and colonic tissue of mice subjected to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis and in the plasma of patients with ulcerative colitis. LP cDCs express the oxytocin receptor and depletion of this receptor in CD11c+ cells worsened colitis in mice. Furthermore, transferring of oxytocin-treated CD11c+ cells to mice with DSS-induced colitis ameliorated the wasting disease likely by preventing cDC maturation and by modulating cytokine production [187].

The basal intestinal DC program for most, if not all cDCs populations, appears to promote tolerance to intestinal commensal bacteria and innocuous antigens, which is associated with the ability of these cells to produce RA and drive de novo Foxp3+ Treg and regulatory Th17 cell differentiation in the MLN, in addition to promoting anti-commensal IgA responses in PPs and ILFs. However, besides their role in maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis, cDCs are also important to initiate effector responses. Particularly, the presence of intestinal inflammation, which is mostly studied in IBD models in mice, can shift cDC function to a more pro-inflammatory professional antigen-presenting cells, which drives effector T cell responses [188] and influences the early differentiation of pre-cDCs that are exposed to an inflammatory rather than a homeostatic environment. The efficient T cell priming by specific DC subtypes requires additional cues from the pro-inflammatory milieu that can stimulate multiple innate receptors and further increase the expression of danger recognition machinery [161–163], which can enhance DC ability to drive effector T cell responses. Consistent with this, it has been shown that CD11b+CD103+ DCs exposed to bacterial flagellin, a TLR5 agonist, in the LP induced IL-23 production and Th17 differentiation. These cells in turn induced IL-22 secretion by ILC3 and promoted antimicrobial peptide production by IECs [189]. Additional pathogen and inflammatory cytokines, for example S. mansoni egg antigen, fungal β-glucans, and microbial nucleic acids, as well as type 1 and II interferons, TSLP, IL-1, and TNF-α produced during infection or abnormal intestinal inflammation have direct influence on cDC phenotypes, which contributes to an appropriate Th1, Th2 or Th17 immunity [190].

In conclusion, the distinctive properties of intestinal DCs are shaped by the integration of host systemic signals as well as local cues from the diet and gut microbiome and can be altered during infection or inflammation to induce appropriate and sometimes inappropriate immune responses.

5. Concluding remarks

Intestinal macrophage and DC populations form an intricate cellular network with distinct but complementary functions that guarantee mucosal immunity and tolerance. Both macrophage and DC subtypes are present in lymphoid and non-lymphoid intestinal tissues. However, regional specializations and a division of labor between these cells can be detected. Anatomical and physiological distinctions along the intestine, and variations in the concentrations of dietary and microbial components are related to higher frequencies of most DC subpopulations in the small intestine niches, while macrophage abundance increases in distal parts of the gut, particularly in colon. The variety of intestinal microenvironments in the small intestine and colon and throughout the crypt–lumen axis, generate specific conditions for the differentiation of macrophage and DC populations with specialized functions to attend to local functional requirements. In fact, cytokines, efferocytosis, diet and microbiota-derived components play a role in modulating macrophages and DCs in the different layers of the gut. Besides their discrete functional duties, macrophages and DCs collaborate to improve antigen presentation and T cell activation. For example, LpMs sample luminal antigens and then transfer them to RA-producing-CD103+ DCs, which then migrate to the MLN to induce antigen-specific Foxp3+ Treg cells, which favor the induction of oral tolerance [25]. Furthermore, intestinal macrophages secrete DC modulating factors such as IL-10 and GM-CSF. IL-10 can inhibit DC activation in several aspects, including the expression of MHC and CD80/CD86 co-stimulatory molecules and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 [191]. GM-CSF induces the activation of the RA producing machinery in DCs, which correlates with Foxp3+ Treg induction [168]. Macrophage-DC crosstalk is also important to control immunopathology in mice infected with Citrobacter rodentium. IL-23 released by macrophages negatively controls deleterious IL-12 production by DCs in colon [192]. Intestinal conditioned DCs and macrophages fulfill a fundamental role in balancing immune activity and thus create homeostatic conditions to prevent detrimental inflammation. A better understanding of factors driving physiological functions of intestinal immune cells may enable novel therapies to IBD and even systemic immune mediated diseases.

Highlights.

Different intestinal niches harbor distinct macrophage and DC subpopulations

Macrophages and DCs induce tolerance and immunity in the gut

Local microenvironments imprint tissue-specific macrophage functions

DC profile can be affected by several conditioners in the intestinal ecosystem

Funding

This work was supported by the Rio de Janeiro State Science Foundation (Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, FAPERJ), Brazilian National Research Council (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, CNPq), and Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH, Bethesda, MD USA. A.A.F. is research fellow at CNPq, and Young Scientist of the State of Rio de Janeiro at FAPERJ, Brazil.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Mowat AM, Agace WW, Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system, Nat Rev Immunol. 14 (2014) 667–685. 10.1038/nri3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Faria AM, Weiner HL, Oral tolerance, Immunol Rev. 206 (2005) 232–259. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Magnusson MK, Brynjolfsson SF, Dige A, Uronen-Hansson H, Borjesson LG, Bengtsson JL, Gudjonsson S, Ohman L, Agnholt J, Sjovall H, Agace WW, Wick MJ, Macrophage and dendritic cell subsets in IBD: ALDH+ cells are reduced in colon tissue of patients with ulcerative colitis regardless of inflammation, Mucosal Immunol. 9 (2016) 171–182. 10.1038/mi.2015.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Meresse B, Malamut G, Cerf-Bensussan N, Celiac disease: an immunological jigsaw, Immunity. 36 (2012) 907–919. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Amit I, Winter DR, Jung S, The role of the local environment and epigenetics in shaping macrophage identity and their effect on tissue homeostasis, Nat Immunol. 17 (2016) 18–25. 10.1038/ni.3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lavin Y, Winter D, Blecher-Gonen R, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Merad M, Jung S, Amit I, Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment, Cell. 159 (2014) 1312–1326. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zeng R, Bscheider M, Lahl K, Lee M, Butcher EC, Generation and transcriptional programming of intestinal dendritic cells: essential role of retinoic acid, Mucosal Immunol 9 (2016) 183–193. 10.1038/mi.2015.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Brandtzaeg P, Development and basic mechanisms of human gut immunity, Nutr Rev 56 (1998) S5–18. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R, Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body, PLoS Biol. 14 (2016) e1002533. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gross M, Salame TM, Jung S, Guardians of the Gut - Murine Intestinal Macrophages and Dendritic Cells, Front Immunol. 6 (2015) 254. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Brandtzaeg P, Kiyono H, Pabst R, Russell MW, Terminology: nomenclature of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, Mucosal Immunol. 1 (2008) 31–37. 10.1038/MI.2007.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moghaddami M, Cummins A, Mayrhofer G, Lymphocyte-filled villi: comparison with other lymphoid aggregations in the mucosa of the human small intestine, Gastroenterology. 115 (1998) 1414–1425. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bain CC, Mowat AM, Macrophages in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation, Immunol Rev. 260 (2014) 102–117. 10.1111/imr.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bujko A, Atlasy N, Landsverk OJB, Richter L, Yaqub S, Horneland R, Oyen O, Aandahl EM, Aabakken L, Stunnenberg HG, Baekkevold ES, Jahnsen FL, Transcriptional and functional profiling defines human small intestinal macrophage subsets, J Exp Med. 215 (2018) 441–458. 10.1084/jem.20170057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].De Schepper S, Stakenborg N, Matteoli G, Verheijden S, Boeckxstaens GE, Muscularis macrophages: Key players in intestinal homeostasis and disease, Cell Immunol. 330 (2018) 142–150. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gabanyi I, Muller PA, Feighery L, Oliveira TY, Costa-Pinto FA, Mucida D, Neuro-immune Interactions Drive Tissue Programming in Intestinal Macrophages, Cell. 164 (2016) 378–391. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bonnardel J, Da Silva C, Henri S, Tamoutounour S, Chasson L, Montanana-Sanchis F, Gorvel JP, Lelouard H, Innate and adaptive immune functions of peyer’s patch monocyte-derived cells, Cell Rep. 11 (2015) 770–784. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cerovic V, Bain CC, Mowat AM, Milling SW, Intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells: what’s the difference?, Trends Immunol. 35 (2014) 270–277. 10.1016/j.it.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Honda M, Surewaard BGJ, Watanabe M, Hedrick CC, Lee WY, Brown K, McCoy KD, Kubes P, Perivascular localization of macrophages in the intestinal mucosa is regulated by Nr4a1 and the microbiome, Nat Commun. 11 (2020) 1329. 10.1038/s41467-020-15068-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Koscso B, Gowda K, Schell TD, Bogunovic M, Purification of dendritic cell and macrophage subsets from the normal mouse small intestine, J Immunol Methods. 421 (2015) 1–13. 10.1016/j.jim.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rivollier A, He J, Kole A, Valatas V, Kelsall BL, Inflammation switches the differentiation program of Ly6Chi monocytes from antiinflammatory macrophages to inflammatory dendritic cells in the colon, J Exp Med. 209 (2012) 139–155. 10.1084/jem.20101387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zigmond E, Jung S, Intestinal macrophages: well educated exceptions from the rule, Trends Immunol. 34 (2013) 162–168. 10.1016/j.it.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].A-Gonzalez N, Quintana JA, García-Silva S, Mazariegos M, de la Aleja AG, Nicolás-ávila JA, Walter W, Adrover JM, Crainiciuc G, Kuchroo VK, Rothlin CV, Peinado H, Castrillo A, Ricote M, Hidalgo A, Phagocytosis imprints heterogeneity in tissue-resident macrophages, J. Exp. Med. 214 (2017) 1281–1296. 10.1084/jem.20161375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H, Gudjonsson S, Jansson O, Grip O, Guilliams M, Malissen B, Agace WW, Mowat AM, Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors, Mucosal Immunol. 6 (2013) 498–510. 10.1038/mi.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mazzini E, Massimiliano L, Penna G, Rescigno M, Oral tolerance can be established via gap junction transfer of fed antigens from CX3CR1(+) macrophages to CD103(+) dendritic cells, Immunity. 40 (2014) 248–261. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sehgal A, Donaldson DS, Pridans C, Sauter KA, Hume DA, Mabbott NA, The role of CSF1R-dependent macrophages in control of the intestinal stem-cell niche, Nat Commun. 9 (2018) 1272. 10.1038/s41467-018-03638-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Smythies LE, Sellers M, Clements RH, Mosteller-Barnum M, Meng G, Benjamin WH, Orenstein JM, Smith PD, Human intestinal macrophages display profound inflammatory anergy despite avid phagocytic and bacteriocidal activity, J Clin Invest. 115 (2005) 66–75. 10.1172/JCI19229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vallon-Eberhard A, Landsman L, Yogev N, Verrier B, Jung S, Transepithelial pathogen uptake into the small intestinal lamina propria, J. Immunol. 176 (2006) 2465–2469. 10.4049/JIMMUNOL.176.4.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chieppa M, Rescigno M, Huang AYC, Germain RN, Dynamic imaging of dendritic cell extension into the small bowel lumen in response to epithelial cell TLR engagement, J. Exp. Med. 203 (2006) 2841–2852. 10.1084/JEM.20061884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Knoop KA, Miller MJ, Newberry RD, Transepithelial antigen delivery in the small intestine: different paths, different outcomes, Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 29 (2013) 112–118. 10.1097/MOG.0B013E32835CF1CD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chikina AS, Nadalin F, Maurin M, San-Roman M, Thomas-Bonafos T, Li XV, Lameiras S, Baulande S, Henri S, Malissen B, Lacerda Mariano L, Barbazan J, Blander JM, Iliev ID, Matic Vignjevic D, Lennon-Duménil AM, Macrophages Maintain Epithelium Integrity by Limiting Fungal Product Absorption, Cell. 183 (2020) 411–428.e16. 10.1016/J.CELL.2020.08.048/ATTACHMENT/CEFF5DB5-F6B3-41D5-9A34-EC6B7BFAA3EB/MMC3.XLSX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Filardy AA, He J, Bennink J, Yewdell J, Kelsall BL, Posttranscriptional control of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in colonic macrophages, Mucosal Immunol. 9 (2016) 850–858. 10.1038/mi.2015.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Roberts PJ, Riley GP, Morgan K, Miller R, Hunter JO, Middleton SJ, The physiological expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the human colon, J Clin Pathol. 54 (2001) 293–297. 10.1136/jcp.54.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Denning TL, Wang YC, Patel SR, Williams IR, Pulendran B, Lamina propria macrophages and dendritic cells differentially induce regulatory and interleukin 17-producing T cell responses, Nat Immunol. 8 (2007) 1086–1094. 10.1038/ni1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cassani B, Villablanca EJ, Quintana FJ, Love PE, Lacy-Hulbert A, Blaner WS, Sparwasser T, Snapper SB, Weiner HL, Mora JR, Gut-tropic T cells that express integrin alpha4beta7 and CCR9 are required for induction of oral immune tolerance in mice, Gastroenterology. 141 (2011) 2109–2118. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hadis U, Wahl B, Schulz O, Hardtke-Wolenski M, Schippers A, Wagner N, Muller W, Sparwasser T, Forster R, Pabst O, Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria, Immunity. 34 (2011) 237–246. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kim M, Galan C, Hill AA, Wu WJ, Fehlner-Peach H, Song HW, Schady D, Bettini ML, Simpson KW, Longman RS, Littman DR, Diehl GE, Critical Role for the Microbiota in CX3CR1(+) Intestinal Mononuclear Phagocyte Regulation of Intestinal T Cell Responses, Immunity. 49 (2018) 151–163 e5. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zigmond E, Bernshtein B, Friedlander G, Walker CR, Yona S, Kim KW, Brenner O, Krauthgamer R, Varol C, Muller W, Jung S, Macrophage-restricted interleukin-10 receptor deficiency, but not IL-10 deficiency, causes severe spontaneous colitis, Immunity. 40 (2014) 720–733. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, Gertz EM, Schaffer AA, Noyan F, Perro M, Diestelhorst J, Allroth A, Murugan D, Hatscher N, Pfeifer D, Sykora KW, Sauer M, Kreipe H, Lacher M, Nustede R, Woellner C, Baumann U, Salzer U, Koletzko S, Shah N, Segal AW, Sauerbrey A, Buderus S, Snapper SB, Grimbacher B, Klein C, Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor, N Engl J Med. 361 (2009) 2033–2045. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Shouval DS, Biswas A, Goettel JA, McCann K, Conaway E, Redhu NS, Mascanfroni ID, Al Adham Z, Lavoie S, Ibourk M, Nguyen DD, Samsom JN, Escher JC, Somech R, Weiss B, Beier R, Conklin LS, Ebens CL, Santos FG, Ferreira AR, Sherlock M, Bhan AK, Muller W, Mora JR, Quintana FJ, Klein C, Muise AM, Horwitz BH, Snapper SB, Interleukin-10 receptor signaling in innate immune cells regulates mucosal immune tolerance and anti-inflammatory macrophage function, Immunity. 40 (2014) 706–719. 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Farache J, Koren I, Milo I, Gurevich I, Kim KW, Zigmond E, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Shakhar G, Luminal bacteria recruit CD103+ dendritic cells into the intestinal epithelium to sample bacterial antigens for presentation, Immunity. 38 (2013) 581–595. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schulz O, Jaensson E, Persson EK, Liu X, Worbs T, Agace WW, Pabst O, Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions, J Exp Med. 206 (2009) 3101–3114. 10.1084/jem.20091925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Worbs T, Bode U, Yan S, Hoffmann MW, Hintzen G, Bernhardt G, Forster R, Pabst O, Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells, J Exp Med. 203 (2006) 519–527. 10.1084/jem.20052016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].De Schepper S, Verheijden S, Aguilera-Lizarraga J, Viola MF, Boesmans W, Stakenborg N, Voytyuk I, Schmidt I, Boeckx B, Dierckx de Casterle I, Baekelandt V, Gonzalez Dominguez E, Mack M, Depoortere I, De Strooper B, Sprangers B, Himmelreich U, Soenen S, Guilliams M, Vanden Berghe P, Jones E, Lambrechts D, Boeckxstaens G, Self-Maintaining Gut Macrophages Are Essential for Intestinal Homeostasis, Cell. 175 (2018) 400–415 e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Domanska D, Majid U, Karlsen VT, Merok MA, Beitnes ACR, Yaqub S, Bækkevold ES, Jahnsen FL, Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human colonic macrophages reveals niche-specific subsets, J. Exp. Med. 219 (2022). 10.1084/JEM.20211846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Da Silva C, Wagner C, Bonnardel J, Gorvel JP, Lelouard H, The Peyer’s Patch Mononuclear Phagocyte System at Steady State and during Infection, Front Immunol. 8 (2017) 1254. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bonnardel J, Da Silva C, Masse M, Montañana-Sanchis F, Gorvel JP, Lelouard H, Gene expression profiling of the Peyer’s patch mononuclear phagocyte system, Genomics Data. 5 (2015) 21–24. 10.1016/J.GDATA.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cerovic V, Bain CC, Mowat AM, Milling SWF, Intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells: what’s the difference?, Trends Immunol. 35 (2014) 270–277. 10.1016/J.IT.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lelouard H, Henri S, De Bovis B, Mugnier B, Chollat-Namy A, Malissen B, Méresse S, Gorvel JP, Pathogenic bacteria and dead cells are internalized by a unique subset of Peyer’s patch dendritic cells that express lysozyme, Gastroenterology. 138 (2010). 10.1053/J.GASTRO.2009.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bonnardel J, Da Silva C, Wagner C, Bonifay R, Chasson L, Masse M, Pollet E, Dalod M, Gorvel JP, Lelouard H, Distribution, location, and transcriptional profile of Peyer’s patch conventional DC subsets at steady state and under TLR7 ligand stimulation, Mucosal Immunol. 10 (2017) 1412–1430. 10.1038/MI.2017.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sakhony OS, Rossy B, Gusti V, Pham AJ, Vu K, Lo DD, M cell-derived vesicles suggest a unique pathway for trans-epithelial antigen delivery, Tissue Barriers. 3 (2015). 10.1080/21688370.2015.1004975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Rochereau N, Drocourt D, Perouzel E, Pavot V, Redelinghuys P, Brown GD, Tiraby G, Roblin X, Verrier B, Genin C, Corthésy B, Paul S, Dectin-1 is essential for reverse transcytosis of glycosylated SIgA-antigen complexes by intestinal M cells, PLoS Biol. 11 (2013). 10.1371/JOURNAL.PBIO.1001658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rahman ZSM, Shao W-H, Khan TN, Zhen Y, Cohen PL, Impaired apoptotic cell clearance in the germinal center by Mer-deficient tingible body macrophages leads to enhanced antibody-forming cell and germinal center responses, J. Immunol. 185 (2010) 5859–5868. 10.4049/JIMMUNOL.1001187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Muller PA, Koscso B, Rajani GM, Stevanovic K, Berres ML, Hashimoto D, Mortha A, Leboeuf M, Li XM, Mucida D, Stanley ER, Dahan S, Margolis KG, Gershon MD, Merad M, Bogunovic M, Crosstalk between muscularis macrophages and enteric neurons regulates gastrointestinal motility, Cell. 158 (2014) 300–313. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Ge X, Ding C, Zhao W, Xu L, Tian H, Gong J, Zhu M, Li J, Li N, Antibiotics-induced depletion of mice microbiota induces changes in host serotonin biosynthesis and intestinal motility, J Transl Med. 15 (2017) 13. 10.1186/s12967-016-1105-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Stakenborg N, Labeeuw E, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, De Schepper S, Aerts R, Goverse G, Farro G, Appeltans I, Meroni E, Stakenborg M, Viola MF, Gonzalez-Dominguez E, Bosmans G, Alpizar YA, Wolthuis A, D’Hoore A, Van Beek K, Verheijden S, Verhaegen M, Derua R, Waelkens E, Moretti M, Gotti C, Augustijns P, Talavera K, Vanden Berghe P, Matteoli G, Boeckxstaens GE, Preoperative administration of the 5-HT4 receptor agonist prucalopride reduces intestinal inflammation and shortens postoperative ileus via cholinergic enteric neurons, Gut. 68 (2019) 1406–1416. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Veiga-Fernandes H, Artis D, Neuronal-immune system cross-talk in homeostasis, Science (80-. ). 359 (2018) 1465–1466. 10.1126/science.aap9598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Matheis F, Muller PA, Graves CL, Gabanyi I, Kerner ZJ, Costa-Borges D, Ahrends T, Rosenstiel P, Mucida D, Adrenergic Signaling in Muscularis Macrophages Limits Infection-Induced Neuronal Loss, Cell. 180 (2020) 64–78 e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ahrends T, Aydin B, Matheis F, Classon CH, Marchildon F, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Mucida D, Enteric pathogens induce tissue tolerance and prevent neuronal loss from subsequent infections, Cell. 184 (2021) 5715–5727 e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Desalegn G, Pabst O, Inflammation triggers immediate rather than progressive changes in monocyte differentiation in the small intestine, Nat Commun. 10 (2019) 3229. 10.1038/s41467-019-11148-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Bain CC, Hawley CA, Garner H, Scott CL, Schridde A, Steers NJ, Mack M, Joshi A, Guilliams M, Mowat AM, Geissmann F, Jenkins SJ, Long-lived self-renewing bone marrow-derived macrophages displace embryo-derived cells to inhabit adult serous cavities, Nat Commun. 7 (2016) ncomms11852. 10.1038/ncomms11852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hashimoto D, Chow A, Noizat C, Teo P, Beasley MB, Leboeuf M, Becker CD, See P, Price J, Lucas D, Greter M, Mortha A, Boyer SW, Forsberg EC, Tanaka M, van Rooijen N, Garcia-Sastre A, Stanley ER, Ginhoux F, Frenette PS, Merad M, Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes, Immunity. 38 (2013) 792–804. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Shaw TN, Houston SA, Wemyss K, Bridgeman HM, Barbera TA, Zangerle-Murray T, Strangward P, Ridley AJL, Wang P, Tamoutounour S, Allen JE, Konkel JE, Grainger JR, Tissue-resident macrophages in the intestine are long lived and defined by Tim-4 and CD4 expression, J Exp Med. 215 (2018) 1507–1518. 10.1084/jem.20180019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, Hume DA, Perlman H, Malissen B, Zelzer E, Jung S, Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis, Immunity. 38 (2013) 79–91. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Gautier EL, Shay T, Miller J, Greter M, Jakubzick C, Ivanov S, Helft J, Chow A, Elpek KG, Gordonov S, Mazloom AR, Ma’ayan A, Chua W-J, Hansen TH, Turley SJ, Merad M, Randolph GJ, Gene-expression profiles and transcriptional regulatory pathways that underlie the identity and diversity of mouse tissue macrophages, Nat. Immunol. 2012 1311. 13 (2012) 1118–1128. 10.1038/ni.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Guilliams M, Scott CL, Does niche competition determine the origin of tissue-resident macrophages?, Nat Rev Immunol. 17 (2017) 451–460. 10.1038/nri.2017.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].van de Laar L, Saelens W, De Prijck S, Martens L, Scott CL, Van Isterdael G, Hoffmann E, Beyaert R, Saeys Y, Lambrecht BN, Guilliams M, Yolk Sac Macrophages, Fetal Liver, and Adult Monocytes Can Colonize an Empty Niche and Develop into Functional Tissue-Resident Macrophages, Immunity. 44 (2016) 755–768. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK, Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota, Nat Rev Microbiol. 14 (2016) 20–32. 10.1038/nrmicro3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bernshtein B, Curato C, Ioannou M, Thaiss CA, Gross-Vered M, Kolesnikov M, Wang Q, David E, Chappell-Maor L, Harmelin A, Elinav E, Thakker P, Papayannopoulos V, Jung S, IL-23-producing IL-10Ralpha-deficient gut macrophages elicit an IL-22-driven proinflammatory epithelial cell response, Sci Immunol. 4 (2019). 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau6571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Schenk M, Bouchon A, Birrer S, Colonna M, Mueller C, Macrophages expressing triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1 are underrepresented in the human intestine, J Immunol. 174 (2005) 517–524. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Shouval DS, Biswas A, Goettel JA, McCann K, Conaway E, Redhu NS, Mascanfroni ID, AlAdham Z, Lavoie S, Ibourk M, Nguyen DD, Samsom JN, Escher JC, Somech R, Weiss B, Beier R, Conklin LS, Ebens CL, Santos FGMS, Ferreira AR, Sherlock M, Bhan AK, Müller W, Mora JR, Quintana FJ, Klein C, Muise AM, Horwitz BH, Snapper SB, Interleukin-10 receptor signaling in innate immune cells regulates mucosal immune tolerance and anti-inflammatory macrophage function, Immunity. 40 (2014) 706–719. 10.1016/J.IMMUNI.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Schridde A, Bain CC, Mayer JU, Montgomery J, Pollet E, Denecke B, Milling SWF, Jenkins SJ, Dalod M, Henri S, Malissen B, Pabst O, McL Mowat A, Tissue-specific differentiation of colonic macrophages requires TGFbeta receptor-mediated signaling, Mucosal Immunol. 10 (2017) 1387–1399. 10.1038/mi.2016.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]