Significance

As a hallmark of heterochromatin in eukaryotes, dimethylated histone H3 Lys9 (H3K9me2) is mainly catalyzed by SUVH family methyltransferases in plants. However, how histone methyltransferases are recruited to specific loci remains largely unknown. The present study demonstrated that a previously uncharacterized N-terminal motif of SUVH6 can be recognized by RNA- and chromatin-binding protein ASI1 to confer H3K9 methylation at most SUVH6-bound loci, giving rise to transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulation depending on the position of target loci. More importantly, SUVH6-ASI1 module-mediated H3K9me2 deposition is evolutionarily conserved in different plant species, suggesting a general mechanism in the delicate regulation of the homeostasis of H3K9 methylation in plants.

Keywords: H3K9me2, SUVH6, ASI1, histone methyltransferase, DNA methylation

Abstract

Dimethylated histone H3 Lys9 (H3K9me2) is a conserved heterochromatic mark catalyzed by SUPPRESSOR OF VARIEGATION 3-9 HOMOLOG (SUVH) methyltransferases in plants. However, the mechanism underlying the locus specificity of SUVH enzymes has long been elusive. Here, we show that a conserved N-terminal motif is essential for SUVH6-mediated H3K9me2 deposition in planta. The SUVH6 N-terminal peptide can be recognized by the bromo-adjacent homology (BAH) domain of the RNA- and chromatin-binding protein ANTI-SILENCING 1 (ASI1), which has been shown to function in a complex to confer gene expression regulation. Structural data indicate that a classic aromatic cage of ASI1-BAH domain specifically recognizes an arginine residue of SUVH6 through extensive hydrogen bonding interactions. A classic aromatic cage of ASI1 specifically recognizes an arginine residue of SUVH6 through extensive cation-π interactions, playing a key role in recognition. The SUVH6-ASI1 module confers locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition at most SUVH6 target loci and gives rise to distinct regulation of gene expression depending on the target loci, either conferring transcriptional silencing or posttranscriptional processing of mRNA. More importantly, such mechanism is conserved in multiple plant species, indicating a coordinated evolutionary process between SUVH6 and ASI1. In summary, our findings uncover a conserved mechanism for the locus specificity of H3K9 methylation in planta. These findings provide mechanistic insights into the delicate regulation of H3K9 methylation homeostasis in plants.

As a hallmark of heterochromatin in eukaryotes, dimethylated or trimethylated histone H3 Lys9 (H3K9me2/3) also has a role in transcriptional gene silencing in euchromatic regions to suppress transposable elements (TEs) and repetitive sequences (1, 2). In plants, H3K9 methylation is mainly catalyzed by plant-specific SUVH family histone methyltransferases (MTases) (3). In the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, a self-reinforcing loop is present in the crosstalk between non-CG DNA methylation and H3K9me2 (4, 5). In this mechanism, H3K9me2 MTases bind to methylated DNA (mDNA) via the SET and RING-associated (SRA) domain to catalyze H3K9 methylation through the pre-SET/SET/post-SET cassette (6, 7), and methylated H3K9 can be targeted by the BAH and chromo domains of the DNA MTases CHROMOMETHYLASE 2 (CMT2) and CHROMOMETHYLASE 3 (CMT3) in turn to catalyze non-CG methylation (7, 8). Therefore, SUVH family H3K9 MTases SUVH4 (also known as KRYPTONITE), SUVH5, and SUVH6 are required for not only H3K9 methylation but also the maintenance of non-CG DNA methylation (4). A recent study further revealed that different SUVH family MTases exhibit distinct DNA-binding preferences and are responsible for H3K9 methylation at different loci (9). For instance, SUVH4 exhibits a strong preference for methylated CAG/CTG, and SUVH5 displays a binding preference for CG methylation-containing CCG-mDNA (9). In contrast, SUVH6 exhibits almost identical binding to all kinds of mDNA (9). The same study also demonstrated that average H3K9me2 levels were largely eliminated in the suvh4 single mutant but were largely unaffected in the suvh5 and suvh6 mutants (9), suggesting that SUVH5 and SUVH6 act redundantly to maintain H3K9me2 levels.

However, apart from the specificity determined by SRA domain-mediated binding of mDNA, whether there are other mechanisms guiding the specificity of SUVH MTases has long been a mystery. A previous report demonstrated that SUVH4 and SUVH5 prefer to target TEs, whereas SUVH4 and SUVH6 tend to control transcribed repeat sources of dsRNA (10), implying that other factors may also take part in governing the activities of different H3K9 MTases in Arabidopsis. Recently, Padeken et al. systematically discussed the distinct mechanisms that regulate each H3K9 MTases family and summarized current knowledge regarding the cofactors and interacting proteins that enable site-specific H3K9 MTases recruitment in mammal (11). The H3K9 MTase SUV39H1 can interact with histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2), and transcriptional silencing by SUV39H1 is abolished by treatment with an HDAC inhibitor (12), suggesting that removal of H3K9 acetylation facilitates H3K9me deposition. In Arabidopsis, histone deacetylase HDA6 physically interacts with H3K9 MTases SUVH4, SUVH5, and SUVH6 to promote the silencing of a subset of TEs and repetitive sequences (13), paralleling the same system in mammals.

H3K9me2, as well as mDNA, is known to have an important effect on the expression of associated genes depending on the chromatin position. Compared to the repressive effect exerted by promoter heterochromatic elements, intragenic heterochromatic elements, usually caused by the extensive insertion events of transposable and repetitive element (TRE), are required for proper gene expression. In this mechanism, the protein complex composed of three proteins, namely ASI1, ASI1 IMMUNOPRECIPITATION PROTEIN 1 (AIPP1), and ENHANCED DOWNY MILDEW 2 (EDM2), the ASI1-AIPP1-EDM2 (AAE) complex, can recognize intronic heterochromatic elements to implement alternative polyadenylation (APA) regulation, leading to proper processing of the full-length transcript (14–16). In this complex, the plant homeodomain protein EDM2 is able to bind H3K9me2 (17–19), and two RNA recognition motif (RRM) domain-containing proteins, ASI1 and AIPP1, possess RNA-binding activity. ASI1 also contains a BAH domain which is a known domain that mediates protein–protein interactions. However, the molecular function of the ASI1-BAH domain is unclear.

In this study, we demonstrate that a previously uncharacterized N-terminal motif of SUVH6 MTase is responsible for locus-specific deposition of H3K9me2 via direct interaction with the ASI1-BAH domain. Structural and biochemical data indicate that the ASI1-BAH domain recognizes the SUVH6 N-terminal peptide via extensive hydrogen bonding interactions. A conserved arginine residue of SUVH6 is specifically recognized by ASI1-BAH by a classic aromatic cage through cation-π interactions. The N-terminal peptide-mediated interaction with ASI1 is indispensable for the chromatin targeting of SUVH6. The SUVH6-ASI1 module confers H3K9me2 deposition at most SUVH6 target loci, giving rise to transcriptional or posttranscriptional regulation depending on the chromatin position. More importantly, SUVH6-ASI1 interaction module-dependent epigenetic regulation exists in different plant species, suggesting the conservation of the SUVH6-ASI1 regulatory pathway. These findings provide mechanistic insights into the locus specificity of H3K9 methylation in planta.

Results

SUVH6 Associates with ASI1 to Form a Conserved Interaction Module in Plants.

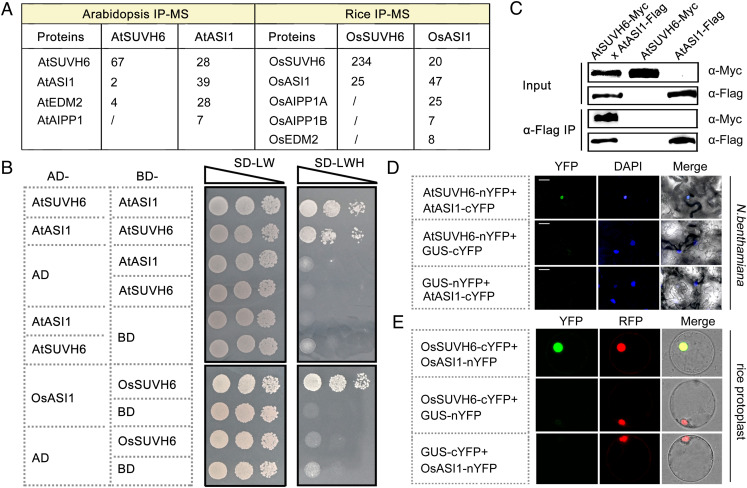

The three SUVH family histone MTases in Arabidopsis, SUVH4, SUVH5, and SUVH6, are responsible for H3K9 methylation and are recruited to target loci through recognition of mDNA by their SRA domains (3, 6, 7). In addition to the current model, whether alternative mechanisms exist to guide locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition is not well understood. To answer this question, SUVH6 immunoprecipitation assay followed by mass spectrometry (IP-MS) was performed with native promoter-driven SUVH6-Myc transgenic Arabidopsis (Col-0 ecotype). The results demonstrated that two chromatin regulators, ASI1 (also named IBM2, INCREASE IN BONSAI METHYLATION 2) (20) and EDM2, were copurified with SUVH6 (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). ASI1 and EDM2 have been shown to form a complex, the AAE complex, with an RRM domain possessing protein AIPP1 [also named ENHANCED DOWNY MILDEW 2 (EDM3)] and function in a conserved manner to implement epigenetic regulation and intragenic heterochromatin-dependent RNA processing in different plant species (14–18, 20–22). Consistently, SUVH6 peptides were also detected in the ASI1 IP-MS assay (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), suggesting that SUVH6 associates with the AAE complex in vivo. Supporting this notion, evidence from a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay indicated that SUVH6 is able to directly interact with ASI1 (Fig. 1B). The interaction was further verified by a coimmunoprecipitation assay performed in transgenic SUVH6-Myc and ASI1-Flag plants (14), and by a biomolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay performed in N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

SUVH6 associates with ASI1 to form a conserved interaction module in plants. (A) IP-MS analysis in Arabidopsis and rice plants showing that SUVH6 and ASI1 associate together in vivo. Numbers represent the identified peptides. One representative result of two biological replicates is shown. (B) Y2H assay showing the direct interactions between SUVH6 and ASI1 proteins from Arabidopsis and rice. (C) α-Flag Co-IP results showing that SUVH6-Myc could be pulled-down by ASI1-Flag in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. (D and E) BiFC assays in N. benthamiana leaves (D) and rice protoplasts (E) showing the interaction of SUVH6 and ASI1 from Arabidopsis and rice plants, respectively. GUS protein served as a negative control. The nuclei were indicated by DAPI staining (D) and red fluorescence of a nuclear protein (E), respectively.

Recent studies have indicated that ASI1-mediated epigenetic regulation is conserved in the monocot rice (22, 23). To test whether the SUVH6-ASI1 interaction is conserved in different plant species, IP-MS assays were also performed in transgenic OsSUVH6-Flag and OsASI1-Myc rice plants (22). OsSUVH6 (also named OsSDG727), a homologous protein of Arabidopsis SUVH6 (AtSUVH6), is a histone H3K9 methyltransferase in rice (24). As expected, OsSUVH6 and OsASI1 could be mutually copurified by each other in IP-MS assays (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), and the interaction was confirmed by Y2H and BiFC data (Fig. 1 B and E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that SUVH6 and ASI1 associate together in vivo to form a conserved interaction module in planta.

The N-Terminal Region of SUVH6 Is Responsible for the Interaction with ASI1.

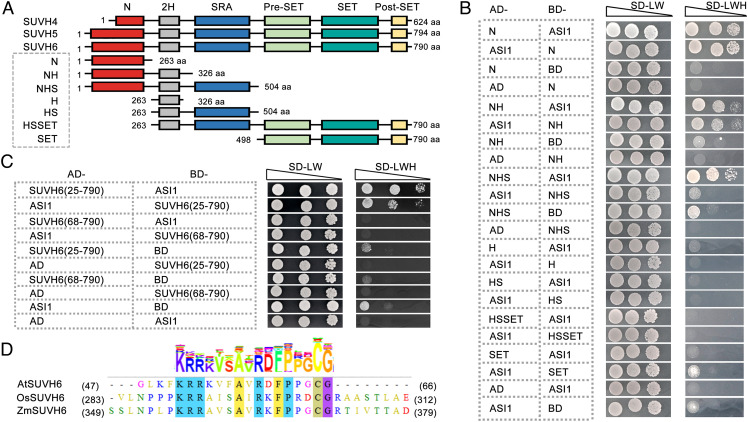

In Arabidopsis, the H3K9 MTases SUVH4, SUVH5, and SUVH6 all contain two helicase domains, an SRA domain that recognizes mDNA, and a pre-SET/SET/post-SET cassette that is responsible for the catalytic activity of H3K9 methylation (Fig. 2A). In addition to these characterized domains, there is an unstructured N-terminal region (N) in these enzymes (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The similar domain arrangement between the three SUVH MTases and the interaction of SUVH6 and ASI1 prompted us to ask whether SUVH4 and SUVH5 also interact with ASI1 in vivo. Unexpectedly, Y2H data demonstrated that neither SUVH4 nor SUVH5 interacted with ASI1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). To decipher the specific region required for the interaction with ASI1, a series of truncated SUVH6 proteins were generated, and the interactions with ASI1 were tested via Y2H. Surprisingly, the sole N-terminal region is sufficient for SUVH6 interaction with ASI1 (Fig. 2B). All the N-terminal region-containing truncated SUVH6 proteins can interact with ASI1 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, all the N-terminal deletion proteins failed to interact with ASI1. To further dissect the sequence required for the SUVH6-ASI1 interaction, the N-terminal region was subdivided. The Y2H results indicated that depletion of the peptide comprising residues 25 to 68 failed to interact with ASI1 (Fig. 2C), suggesting that this peptide may be indispensable for the SUVH6-ASI1 interaction. Intriguingly, this peptide is absent in the N-terminal region of SUVH4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). More importantly, the sequence of this peptide displays a high similarity in SUVH6 homologous proteins but exhibits obvious variation in SUVH5 (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

A conserved N-terminal region of SUVH6 is sufficient for the interaction with ASI1. (A) Diagrammatic sketches showing the protein domain structures of Arabidopsis SUVH4, SUVH5, and SUVH6, and the different truncated proteins of SUVH6. (B) Y2H data showing the requirement of different SUVH6 domains for the interaction with ASI1. (C) Y2H data showing the requirement of different sequences within the N-terminal regions of SUVH6 responsible for the interaction with ASI1. (D) Amino acid sequence alignment showing the conserved sequence motif between SUVH6 homologous proteins in different plant species. The UniProt IDs for the sequences used in the alignment are AtSUVH6 (Q8VZ17), OsSUVH6 (Q6K4E6), and ZmASI1 (A0A1D6EPB3).

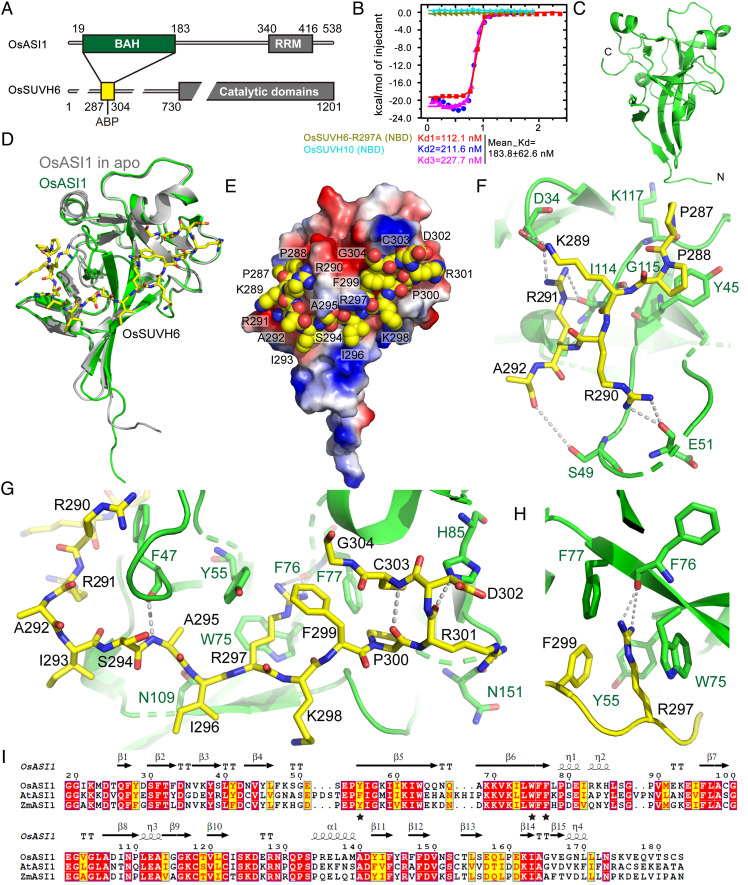

Structure of the OsASI1-BAH Domain in Complex with an OsSUVH6 Peptide.

To explore the molecular basis for the recognition of SUVH6 by ASI1, we carried out biochemical and structural studies. We tried to purify the recombinant AtASI1-BAH domain expressed in Escherichia coli to test its binding toward the AtSUVH6 N-terminal peptides. However, the recombinant AtASI1-BAH protein was unstable and degraded easily, although protease inhibitors were added during protein purification. Considering that SUVH6 and ASI1 in Arabidopsis and rice are conserved and that OsASI1 showed similar binding to OsSUVH6 in our assay (Fig. 1), we used rice proteins in the following biochemical and structural assays (Fig. 3A). The binding between OsASI1-BAH (residues 19 to 183) and an OsSUVH6 N-terminal peptide (OsSUVH6N, residues 287 to 304) was measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), yielding a strong binding (Kd = 183.8 ± 62.6 nM from three repeats) (Fig. 3 A and B). We next determined the crystal structure of the rice ASI1-BAH domain at 2.3 Å resolution (Fig. 3 A and C and SI Appendix, Table S1). There is one molecule in the asymmetric unit. The OsASI1-BAH adopts a classic BAH domain fold, which is composed of a central twisted b-barrel flanked by several a-helices (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Structural basis for the recognition of SUVH6 by the ASI1 BAH domain. (A) The domain architectures of OsASI1 (Upper) and OsSUVH6 (Lower). The BAH domain of OsASI1 and the ASI1-binding peptide (ABP) of OsSUVH6 constructs are marked in green and yellow, respectively. (B) The ITC measurement of the interaction between the OsASI1-BAH domain and OsSUVH6 ABP showed a strong binding affinity of 183.8 ± 62.6 nM (n = 3, mean ± SD). Three replicates were performed for the measured of OsASI1-BAH and OsSUVH6-N. The binding of OsASI1-BAH with OsSUVH6-R297A mutated peptide and OsSUVH10 N-terminal peptide were also tested for controls. (C) Overall structure of the OsASI1-BAH domain with the N- and C-termini marked. (D) Overall structure of OsASI1-BAH in complex with an OsSUVH6 peptide with OsASI1 and OsSUVH6 shown in ribbon and stick representations, respectively. The structure of the apo form of OsASI1-BAH is superimposed in silver. (E) An electrostatistic surface view of OsASI1-BAH with OsSUVH6 shown in a space-filling representation. (F and G) The detailed interactions between OsASI1 and the OsSUVH6 N- (F) and C-terminal (G) regions. The OsSUVH6 and interacting residues in OsASI1 are shown as stick representations, while the hydrogen bonds are highlighted with dashed lines. (H) An enlarged view of the recognition of OsSUVH6 Arg297 by an aromatic cage through cation-p and hydrogen bonding interactions. (I) A structure-based sequence alignment of ASI1 proteins from rice, arabidopsis, and maize showing conserved aromatic residues (marked by stars) for arginine binding. The UniProt IDs for the sequences used in the sequence alignment are OsASI1 (Q5ZE12), AtASI1 (Q9LYE3), and ZmASI1 (B4F9Z3).

Molecular Basis for the Recognition of SUVH6 by ASI1.

Next, we further determined the crystal structure of OsASI1-BAH in complex with the OsSUVH6 N-terminal peptide at 1.8 Å resolution (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Table S1). There are two OsASI1-BAH-OsSUVH6N complexes in the asymmetric unit, possessing very similar conformation with an RMSD of 0.5 Å for 176 aligned Cas upon superimposition of the two complexes. The OsASI1-BAH domain in the apo form and in the OsSUVH6 peptide-bound form possess almost identical conformations, having an RMSD of 1.1 Å for 158 aligned Cas upon superimposition (Fig. 3D). OsASI1-BAH possesses a long extended negatively charged surface cleft to accommodate the peptide (Fig. 3E). All the peptide residues from Pro287 to Gly304 can be traced with clear electron density (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). The peptide adopts an “L”-shaped structure with Ile293 as the vertex to divide the peptide into an N-terminal part (Pro287 to Ile293) and a C-terminal part (Ser294 to Gly304) (Fig. 3 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). The “L”-shaped OsSUVH6 peptide docks into the OsASI1-BAH cleft and wraps around the central region of OsASI1-BAH possessing a large interacting interface, that buries surface areas of 1,091 Å2 on OsASI1-BAH and 1,317 Å2 on OsSUVH6 peptide, consistent with the strong binding affinity of 183.8 nM (Fig. 3 B and E).

The recognition of the “L”-shaped OsSUVH6 peptide can be divided into two parts: the N-terminal part and the C-terminal part (Fig. 3 F and G). In the N-terminal region, the Pro288 forms hydrophobic and CH-π stacking interactions with OsASI1 Tyr45 (Fig. 3F). The OsSUVH6 residues Lys289, Arg290, and Arg291 form salt bridges and hydrogen bonding interactions with OsASI1 Asp34 and Glu51 (Fig. 3F), highlighting the electrostatic interactions between the two molecules. In addition, the main chains of OsASI1 Lys117, Gly115, Ile114, and Ser49 were involved in hydrogen bonding interactions with the peptide (Fig. 3F). In the C-terminal region, OsSUVH6 Ala295, Ile296, Arg297, and Arg301 form an extensive hydrogen bonding interaction network with OsASI1-BAH residues Phe47, Asn109, Phe76, His 85, and Asn151 (Fig. 3 G and H). Moreover, OsASI1-BAH residues Tyr55, Trp75, and Phe77, together with OsSUVH6 residue Phe299, form a deep compact aromatic cage to specifically accommodate OsSUVH6 Arg297 with extensive cation-π interactions (Fig. 3H). In addition, the main chain carbonyl group of OsASI1 Phe76 forms two hydrogen bonds with protons of the guanidine group of OsSUVH6 Arg297 (Fig. 3H), suggesting that OsSUVH6 Arg297 plays a key role in recognition. Consistently, the R297A mutation of OsSUVH6N lost the ability to bind OsASI1-BAH (Fig. 3B). Meanwhile, the OsSUVH10, possessing several conserved flanking residues but lacking the R297 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), displayed no detectable interaction with OsASI1-BAH (Fig. 3B). While Arg297 and Phe299 of OsSUVH6 are strictly conserved in plants (Fig. 2D), the aromatic residues of ASI1 that form the Arg-binding aromatic cage are also conserved (Fig. 3I), suggesting a conserved interaction between ASI1 and SUVH6. Along the peptide, Ala292, Asp302, and part of Arg290 involved in the crystal packing, while most of the key residues of peptide specifically interact with the OsASI1-BAH, suggesting that the complex is not formed by crystal packing.

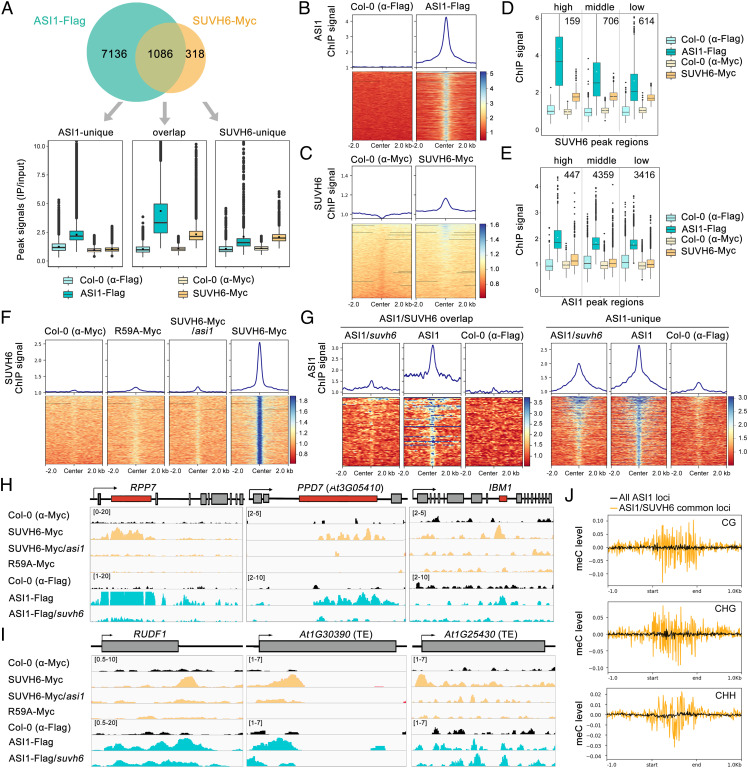

Most SUVH6-Binding Loci Are Targeted by ASI1.

The unique recognition of the SUVH6 N-terminal motif by the ASI1-BAH domain inspired us to explore their interaction in chromatin targeting. To this end, SUVH6 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) assays were performed in Col-0 and transgenic Arabidopsis SUVH6-Myc plants, and the SUVH6-binding peaks were compared with recently published ASI1 ChIP-seq data (16), which was performed with SUVH6-Myc ChIP-seq assay in the same batch. The results indicated that approximately 77% (1086/1404) of SUVH6-bound loci overlapped with ASI1 ChIP-seq peaks and that the ASI1 distribution was enriched in the center of SUVH6 peaks (Fig. 4 A and B). In contrast, the distribution of SUVH6 was not well correlated with ASI1 occupancy and there was weak SUVH6 enrichment at the ASI1-unique loci (Fig. 4 A and C). Similar patterns were also observed when measuring ASI1/SUVH6 ChIP signals at classified (according to the ChIP signals) peak regions, and the strength of the ASI1 ChIP signals was proportional to that of SUVH6 ChIP signals (Fig. 4 D and E). Based on this evidence, we can conclude that ASI1 and SUVH6 commonly target a substantial subset of genomic loci and that most SUVH6-binding loci are targeted by ASI1.

Fig. 4.

ASI1 and SUVH6 commonly bind to a subset of genomic loci. (A) Upper panel: Venn diagram showing the overlap of ASI1 and SUVH6 ChIP-seq peaks. Lower panel: Boxplot diagrams showing ASI1 and SUVH6 ChIP signals of corresponding peak regions according to Venn diagram. ASI1 ChIP-seq peaks were calculated from published data (16). Col-0 samples were used as negative controls. (B) Distribution of ASI1 ChIP–seq tags around the center of SUVH6 ChIP peaks. (C) Distribution of SUVH6 ChIP–seq tags around the center of ASI1 ChIP peaks. (D) ChIP signals of ASI1 and SUVH6 in SUVH6 peak regions. High, middle, and low ChIP signal groups were clustered according to SUVH6-binding strength by kmean. (E) ChIP signals of ASI1 and SUVH6 in ASI1 peak regions. ChIP signal groups were clustered according to ASI1-binding strength by kmean. (F) SUVH6-binding strength in Col-0, SUVH6-R59A-Myc, SUVH6-Myc/asi1, and SUVH6-Myc. (G) ChIP signal of overlapping ASI1/SUVH6 targets or unique ASI1 targets in Col-0, ASI1-Flag/suvh6, and ASI-Flag. (H and I) Snapshots of ChIP-seq showing the binding of ASI1 and SUVH6 at known intronic heterochromatin-containing genes (H) and other genes (I) in different genotypes. Grey and orange boxes represent exons and TREs, respectively. One representative replicate is shown for each ChIP-seq assay. (J) DNA methylation levels at all ASI1 target loci and ASI1/SUVH6 common target loci. The methylation levels were plotted by deepTools with bin size = 10bp.

The Chromatin Targeting of SUVH6 Mainly Depends on Its Interaction with ASI1.

Next, we asked whether the ASI1-SUVH6 interaction is indispensable for SUVH6-binding at target loci and vice versa. To this end, SUVH6 ChIP-seq assays were performed in SUVH6-Myc/suvh6 asi1 plants by crossing SUVH6-Myc/suvh6 plants into asi1 mutants. Arg59 of AtSUVH6, which is equivalent to Arg297 of OsSUVH6 and plays a key role in recognition by the ASI1 aromatic cage (Figs. 2D and 3H), was mutated to alanine (R59A), and native promoter-driven R59A-Myc was expressed in the suvh6 mutant in a genetic complementation assay. ChIP-seq was also performed in R59A-Myc/suvh6 plants to investigate the effect of Arg59 mutation on AtSUVH6 binding. The SUVH6 ChIP-seq data in SUVH6-Myc/suvh6, SUVH6-Myc/suvh6 asi1, and R59A-Myc/suvh6 plants clearly showed that the chromatin targeting of SUVH6 was almost abolished in the asi1 mutant background or by the R59A mutation compared with that in SUVH6-Myc plants (Fig. 4F), suggesting that the existence of ASI1 and the conserved Arg59 are indispensable for SUVH6 binding at target chromatin. Supporting this notion, the SUVH6 R59A protein failed to interact with ASI1 in the Y2H assay (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). To test whether ASI1 binding is also affected by the absence of SUVH6, additional ASI1 ChIP-seq assays were performed in ASI1-Flag and ASI1-Flag/suvh6 plants. Intriguingly, ASI1 binding at ASI1/SUVH6 cotargeting regions was greatly reduced in the absence of SUVH6, but displayed only moderate reductions at the regions uniquely targeted by ASI1 (Fig. 4G). To confirm the above findings, we examined the representative loci commonly targeted by ASI1 and SUVH6, including the known intronic TRE-containing APA genes (Fig. 4H) and nonAPA genes (Fig. 4I). In line with the above genome-wide patterns, SUVH6 binding was also abolished in the asi1 mutant and R59A-Myc/suvh6 transgenic plant at all the tested target loci, and ASI1 binding exhibited a moderate reduction in the absence of SUVH6. Nevertheless, for the loci specifically targeted by ASI1, ASI1 binding was not significantly affected by the absence of SUVH6 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). Considering the mDNA-binding activity possessed by SUVH6-SRA domain, we analyzed DNA methylation levels across all ASI1 target loci and ASI1/SUVH6 common target loci using published DNA methylome data in Col-0 (15). It clearly indicated that ASI1/SUVH6 common target loci display much higher DNA methylation level in comparison with all ASI1 target loci (Fig. 4J and SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). We speculate that in hypomethylated regions targeted by ASI1, SUVH6 failed to bind chromatin and cannot form stably interaction loop with ASI1. This is also consistent with our results in Fig. 4A that ASI1 ChIP signal at ASI1-unique peaks was much lower than at ASI1/SUVH6 common target loci. Combined with the above data, the chromatin targeting of SUVH6 mainly depends on its interaction with ASI1.

SUVH6-ASI Interaction Confers Locus-Specific H3K9me2 Deposition and Gene Expression Regulation.

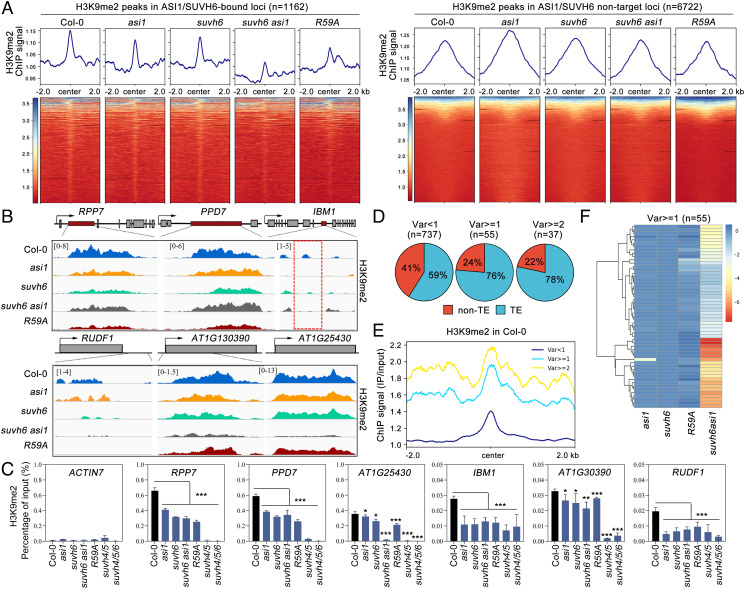

Next, the specific recognition of the SUVH6 N-terminal motif by the ASI1-BAH domain and chromatin cotargeting inspired us to propose that ASI1 may contribute to the locus-specific deposition of H3K9me2 catalyzed by SUVH6. To test this hypothesis, H3K9me2 levels were examined by performing ChIP-seq in Col-0, asi1, suvh6, R59A, and suvh6 asi1 double mutants. The results indicated that H3K9me2 levels at the common target loci of ASI1 and SUVH6 were obviously downregulated in asi1, suvh6, and R59A plants compared with Col-0, and the reduction was more pronounced in the suvh6 asi1 mutant (Fig. 5 A, Left). In contrast, H3K9me2 peaks in non-target loci were visibly increased in the asi1 mutant but no significant changes in other plants (Fig. 5 A, Right). This is in line with the knowledge that dysfunction of the ASI1-containing AAE complex leads to a great reduction in the expression of the histone H3K9me2 demethylase gene IBM1 through the APA mechanism in Arabidopsis (15, 16), which in turn increases global H3K9me2 levels. Taking this factor into account, the actual reduction of H3K9me2 level at ASI1/SUVH6 common target loci caused by the absence of ASI1 and SUVH6 will be more pronounced than what is shown in Fig. 5A. Indeed, obvious H3K9me2 downregulation was observed at the representative ASI1/SUVH6 common target genes, including the intronic TRE-containing APA genes and other target genes, in asi1 and suvh6 mutants (Fig. 5 B and C).

Fig. 5.

Interaction with ASI1 promotes locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition by SUVH6 and dependent gene expression regulation. (A) Left: H3K9me2 profiles around the centre of ASI1/SUVH6-bound loci (Left) and ASI1-SUVH6 non-target loci (Right). (B and C) Snapshots of ChIP-seq (B) and ChIP-qPCR results (C) showing H3K9me2 levels in Col-0, asi1suvh6suvh6 asi1suvh4/5suvh4/5/6, and R59A plants at known intronic TRE-containing genes (Upper) and other genes (Lower) commonly targeted by ASI1 and SUVH6. One representative replicate is shown for each ChIP-seq data. The data are the means ± SD of three technical repeats. One representative result of three biological replicates is shown. Unpaired one-tailed t test was performed, and ***, **, and * represent P values < 0.01, 0.1, and 0.5, respectively. (D) The distribution pattern of SUVH6/ASI1 common target loci in diverse variation (Var) levels. Log2 fold changes of H3K9me2 level of suvh6 and asi1/suvh6 were calculated by comparing to Col-0. Then, the value of Var equal to suvh6 minus asi1/suvh6. The larger the var value, the lower the reduction of the asi1/suvh6 double mutant relative to the suvh6 mutant. Clusters were assigned according to the Var level. Annotation of TE according to araport11. (E) H3K9me2 levels (in Col-0) among different types of ASI1-SUVH6 target regions. Center indicates the summit point of ASI1-SUVH6 target peak. (F) H3K9me2 level of mutant compared with Col-0 in all var>=1 (n = 55) sites. Log2 fold changes of H3K9me2 level of asi1suvh6R59A, and asi1/suvh6 were calculated by comparing to Col-0 and were shown in the heatmap.

We next examined how many ASI1/SUVH6 peaks display H3K9me2 enrichment. Among all ASI1/SUVH6 peaks, 323 peaks overlap with H3K9me2 peaks (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). However, we found that half of target loci presented in this study was not included in the 323 loci, including IBM1, RUDF1, and AT1G30390, probably due to lower H3K9me2 level at these loci compared with others (Fig. 5 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). Based on these data, we concluded that H3K9me2 level of substantial loci is under the common control of ASI1-SUVH6 module.

Meanwhile, we noticed that AT1G25430 displayed stronger reduction in suvh6 asi1 double mutant in comparison with single mutants (Fig. 5 B and C). To figure out the underlying mechanism, we screened out similar loci according to Log2 fold changes of H3K9me2 level in suvh6 and suvh6 asi1 mutant and the chromatin features of these loci were investigated. We found a close relationship between the presence of TE, H3K9me2 level, and the reduction in double mutant. Although such loci are very few relative to those loci without additive effect, it is clear that the higher the proportion of TE genes (Fig. 5D) and H3K9me2 level (Fig. 5E), the greater the H3K9me2 reduction between double mutant and single mutants (Fig. 5F). This is consistent with the known knowledge that most TEs are epigenetically silenced by heterochromatic marks including H3K9me2. Although these sites are a small fraction (n = 55) of the total number of SUVH6-ASI1-bound loci, higher H3K9me level on these sites may have a great impact on the whole H3K9me2 level (Fig. 5A). More detail will be addressed in the discussion section.

SUVH6-ASI1 Module Confers Transcriptional and Posttrans criptional Regulation on Target Genes.

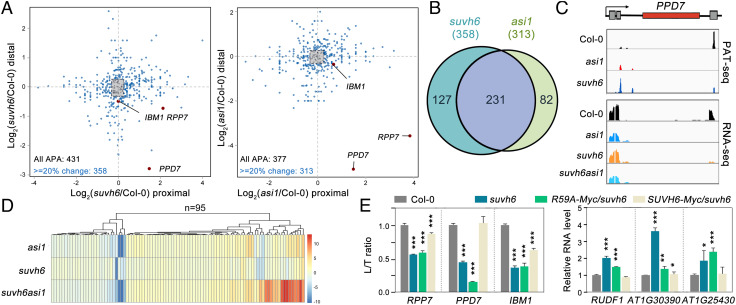

To test whether ASI1-SUVH6 interaction-dependent H3K9me2 deposition has a direct role in the expression of associated genes, transcriptome and poly(A) usage were measured by performing RNA-seq and poly (A)-tag sequencing (PAT-seq) in Col-0, asi1, and suvh6 mutants as previously reported (16). As shown in Fig. 6A, 431 and 377 loci showed diverse selection of poly(A) site in suvh6 and asi1 mutants, respectively. When more than 20% change cutoff was used, the numbers are 358 and 313 in suvh6 and asi1 mutants. Among these loci, 231 loci were commonly present in suvh6 and asi1 mutants (Fig. 6B), suggesting that SUVH6 and ASI1 commonly target a substantial subset of loci for polyadenylation regulation. For the known APA genes IBM1, AT3G05410, and RPP7, similar to the asi1 mutant, PAT-seq data demonstrated that the usage of distal poly(A) sites, which are located downstream of the intronic TRE regions bound by ASI1 and SUVH6 (Fig. 6C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9), was greatly reduced in suvh6 compared with Col-0, whereas the upstream proximal poly(A) sites were selected (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9), giving rise to a reduction in full-length transcripts and an increase in short transcripts in the suvh6 mutant (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10). In these sites, suvh6 asi1 double mutant shows similar phenotype with asi1 mutant while suvh6 performs weakly. This is consistent with that ASI1 playing a decisive role in APA regulation. Therefore, in this case, the ASI1-SUVH6 module serves as a guarder of the proper processing for these intronic TRE-containing genes by promoting H3K9me2 deposition at the intronic TRE region. In addition, RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analyses indicated that a subset of genes was commonly regulated in asi1 and suvh6 mutants, including the nonAPA genes targeted by ASI1 and SUVH6 (Fig. 6 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Among them, 95 genes targeted by ASI1 and SUVH6 were mis-regulated in suvh6 asi1 mutants (Fig. 6D), further supporting the functional interdependence of ASI1 and SUVH6 in chromatin targeting, H3K9me2 deposition, and gene expression. Intriguingly, different from the downregulation of intronic TRE-containing genes, most genes were upregulated in asi1 and suvh6 mutants (Fig. 6D), including the representative target genes RUDF1, AT1G30390, and AT1G25430 commonly targeted by ASI1 and SUVH6. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the upregulation is due to transcriptional derepression caused by the downregulation of H3K9me2 levels in asi1 and suvh6 mutants. Meanwhile, SUVH6-Myc transgenic line, but not the R59A-Myc transgene, complemented the APA and gene expression phenotype at the representative genes, indicating the significance of the key Arg (Fig. 6E). Therefore, in the case of these non-APA targets, the ASI1-SUVH6 interaction confers transcriptional repression by promoting H3K9me2 deposition at the noncoding regions. In general, the ASI1-SUVH6 interaction confers locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition at common target loci, giving rise to transcriptional repression or proper RNA processing at the posttranscriptional level depending on the chromatin position.

Fig. 6.

SUVH6-ASI1 module-mediated regulation on polyadenylation and gene expression. (A) The effect of suvh6 and asi1 mutations on the polyadenylation patterns of the genes commonly bound by ASI1 and SUVH6. Top2 expressed poly(A) sites were extracted for the analyses. Gray rectangles indicate sites with expression variation <20% when comparing to the site in Col-0. Three representative APA genes targeted by ASI1 and SUVH6 were labeled with red dots. (B) Venn diagram shows that the polyadenylation of 231 genes were corporately regulated by ASI1 and SUVH6 in all SUVH6/ASI1 common target loci. (C) Snapshots of PAT-seq and RNA-seq showing the poly(A) usage and RNA-seq read distribution at one representative APA gene AT3G05410. (D) Heatmap shows that among ASI1/SUVH6-bound genes, 95 genes were differentially expressed in suvh6 asi1 double mutant compared with Col-0. The differential expressed genes (DEGs) were determined with absolute log2 fold change (suvh6 asi1/Col-0) ≥±0.6 and P value <0.05. Log2 fold changes of gene expression level of suvh6, asi1, and suvh6 asi1 were calculated by comparing to Col-0 and subjected for heatmap plot. (E) The ratio of long/total (L/T) transcripts of APA genes (Upper) and the relative RNA levels of nonAPA genes in Col-0, suvh6R59A-Myc/suvh6, and SUVH6-Myc/suvh6 plants. The mRNA levels were first normalized to ACT2 and then to Col-0. The data are the means ± SD of three biological repeats. Unpaired one-tailed t test was performed, and ***, **, and * represent P values < 0.01, 0.1, and 0.5, respectively.

SUVH6-ASI1 Module-Dependent H3K9me2 Deposition Is Conserved in Plants.

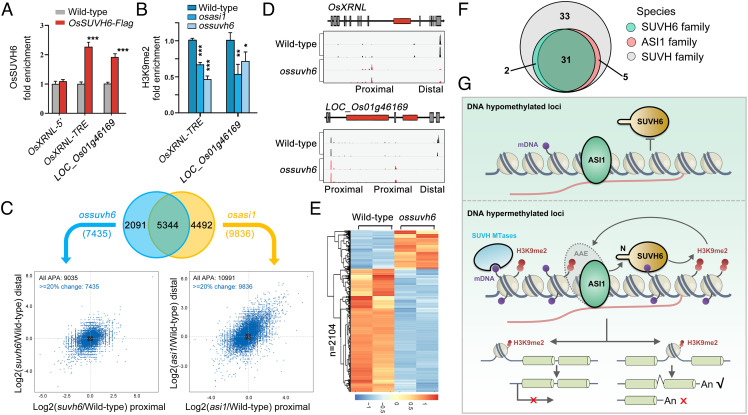

Next, the conserved recognition of the OsSUVH6 N-terminal motif by OsASI1 in rice prompted us to investigate whether the OsSUVH6-OsASI1 module, like its Arabidopsis counterpart, acts similarly in chromatin targeting and locus-specific deposition of H3K9me2. To address this issue, we examined the binding of OsSUVH6 at two intronic TRE-containing genes that have been shown to be subjected to OsASI1-mediated APA regulation, including the GDSL-like lipase gene LOC_Os01g46169 and the exonuclease gene OsXRNL which functions in microRNA biosynthesis (22). OsSUVH6 ChIP-qPCR results demonstrated that specific binding of OsSUVH6 at the intronic TRE regions was observed in OsSUVH6-Flag transgenic plants compared with the wild-type control (Fig. 7A). To assess the effect of OsSUVH6 dysfunction on H3K9me2 deposition and gene expression, an ossuvh6 mutant was generated using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), and an H3K9me2 ChIP-qPCR assay was performed in wild-type, ossuvh6 and a previously reported osasi1 mutant (22). The result showed that H3K9me2 levels at the TRE regions were significantly reduced in both osasi1 and ossuvh6 mutants compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 7B). Then we performed PAT-seq in the ossuvh6 mutant to test whether SUVH6 dysfunction has an effect on the polyadenylation of these intronic TRE-containing genes, as observed in the osasi1 mutant (22). As shown in Fig. 7C, 7435 and 9836 loci showed diverse selection of poly(A) site in ossuvh6 and osasi1 mutants under 20% change cutoff, respectively, including the known intronic TRE-containing genes OsXRNL and LOC_Os01g46169 (Fig. 7D). This number is far larger than in Arabidopsis. It’s probably because over 10% of rice genes contain intronic heterochromatin, and is tenfold more abundant than in Arabidopsis (23). Among these loci, 5344 loci (72%) regulated by OsSUVH6 were also present in osasi1 mutants (Fig. 7C), suggesting that OsSUVH6 and OsASI1 commonly target a substantial subset of loci for polyadenylation regulation. Meanwhile, mRNA-seq of ossuvh6 mutant showed that 2,104 genes were mis-regulated in mutant (Fig. 7E), and most genes were upregulated, consistent with the transcriptional repression function of OsSUVH6. These data strongly support the notion that SUVH6-ASI1 module-dependent locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition and gene expression regulation are conserved in rice.

Fig. 7.

SUVH6-ASI1 module-dependent locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition is conserved in plants. (A and B) ChIP-qPCR showing the fold enrichment of OsSUVH6 (A) and H3K9me2 (B) at the intronic TRE regions of two representative APA genes. OsSUVH6 ChIP assays were performed in wild-type and OsSUVH6-Flag transgenic rice plants. H3K9me2 ChIP assays were performed in wild-type, osasi1 and ossuvh6 plants. ChIP–qPCR data were normalized to internal inputs, and then a control gene (Osactin) was used to calculate relative ChIP signals. The data are the means ± SD of three biological repeats. An unpaired one-tailed t test was performed. ***, **, and * represent P values < 0.01, 0.1, and 0.5, respectively. (C) The effect of ossuvh6 and osasi1 mutations on the global polyadenylation patterns in rice. Top2 expressed poly(A) sites were extracted for the analyses. Venn diagram shows that the genes were corporately regulated by OsASI1 and OsSUVH6 (Upper panel). Black rectangles indicate sites with expression variation < 20% when comparing to the site in wild-type (Lower panel). (D) Snapshots of PAT-seq showing the usage of poly(A) sites at two intronic TRE-containing genes. (E) Heatmap showing the expression pattern of differentially expressed genes in ossuvh6 mutant and wild-type plants. (F) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the species encoding the homologous proteins of ASI1, SUVH6, and SUVH family histone MTases. Species analyses were conducted using an online tool (http://www.pantherdb.org/). (G) A working model of SUVH6-ASI1 module-dependent H3K9me2 deposition and dependent gene expression regulation. The cylinder diagrams represent exons.

The above findings inspired us to ask whether the unique ASI1-SUVH6 interacting module is coevolved and widespread in the plant kingdom. We used Arabidopsis ASI1 and SUVH MTases as bait to search the species encoding their homologous proteins. Intriguingly, all the retrieved homologous proteins were from plant species (Fig. 7F and SI Appendix, Table S2). More importantly, the species encoding ASI1 homologous proteins highly overlapped with SUVH6 species, implying that ASI1 and SUVH6 may undergo a coordinated regulation during evolution. Taken together, these data addressed a working model of ASI1-SUVH6 module-dependent H3K9me2 deposition and gene expression regulation. In DNA hypomethylated regions with ASI1 binding, SUVH6 fails to bind chromatin and form a stable self-reinforcing feedback loop with ASI1 (Fig. 7 G, Upper). In DNA-hypermethylated regions, SUVH6 is recruited by ASI1 through conserved N-terminal and binds mDNA via the SRA domain to confer H3K9me2 deposition at ASI1-SUVH6 target loci. In turn, additional ASI bind here through AAE complex and form a stable self-reinforcing feedback loop with SUVH6 (Fig. 7 G, Lower). SUVH6-ASI1 module-dependent H3K9me2 deposition results in differential gene expression depending on the position, either conferring transcriptional repression at the promoter region or promoting distal polyadenylation at intronic TRE regions.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated an SRA domain-dependent mDNA recognition mechanism underlying the substrate specificity of H3K9me2 deposition in plants. In this study, our data support an H3K9me2 self-reinforcing feedback loop mediated by a previously uncharacterized N-terminal motif of SUVH MTases in plants. In this model, the N-terminal peptide of SUVH6 family MTases can be recognized by ASI1 family chromatin regulators via unique interaction with the BAH domain, giving rise to H3K9me2 deposition and dependent gene expression regulation at specific loci.

The ASI1-BAH Domain Is an Unmethylated Arginine Reader.

The BAH domain is a conserved domain that mainly functions in mediating protein–protein interactions (25). Recently, several histone mark-reading BAH domains, including Arabidopsis AIPP3, EBS, SHL, and mouse BAHCC1 BAH domains, which read H3K27me3 (26–29), mouse-ORC1 and bovine DNMT1 BAH domains, which read H4K20me2 (30, 31), and maize-ZMET2-BAH, which reads H3K9me2 (8), were reported. Although the methylation of either OsSUVH6 R297 or AtSUVH6 R59 has never been reported, biochemically, the OsASI1-BAH domain specifically reads the unmodified Arg297 of OsSUVH6 by an aromatic cage. The reading of unmethylated arginine by OsASI1-BAH highlighted contribution by an aromatic cage by cation-π interaction and is totally different from the reported unmethylated arginine reader Ubiquitin Like With PHD And Ring Finger Domains 1 (UHRF1), that solely depends on hydrogen bonding and salt–bridge interaction between negatively charged residues of UHRF1 and arginine to achieve unmodified arginine-specific binding (32). The aromatic cage of OsASI1-BAH is conserved among all those methyllysine-binding BAH domains in structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A). More importantly, the aromatic cage residues are conserved in both structure and sequence (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 A and B), suggesting that the BAH domains possess this evolutionarily conserved binding pocket, which is diversified into different subgroups to fit with different ligands. We further tested the biochemical influence of binding by arginine methylation on Arg297 of OsSUVH6. Our ITC data suggested that the methylation of OsSUVH6 Arg297, including monomethylation, symmetric dimethylation, and asymmetric dimethylation, did not enhance but rather decreased the binding between OsSUVH6 and OsASI1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S12C), suggesting that OsASI1 is solely an unmodified arginine reader. The aromatic cage of OsASI1-BAH is similar in size to other methyllysine-reading BAH domains (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 B, Right). Considering unmethylated arginine has similar size as methylated lysine but that methylated arginine is much larger than methyllysine, we conclude that the pocket size of OsASI1-BAH restricts the reading of unmodified Arg297 but not methylated forms. Consequently, monomethylated R297me1 showed slightly decreased binding, but dimethylated R297sym2 and R297asym2 showed significantly decreased binding, reflecting a methylation level-dependent decrease in binding. As the aromatic cage of ASI1-BAH resembles the methyllysine reading ones, we cannot rule out the possibility of its reading of methyllysine of histone or non-histone proteins, which requires further investigation.

The Conserved N-Terminal Domain and Chromatin Targeting of SUVH6.

Considering the fact that some SUVH MTases lack the N-terminal peptide which can be recognized by ASI1-BAH, such as SUVH4 in Arabidopsis, the presence of this N-terminal peptide definitely contributes to the mechanism diversity underlying locus-specific H3K9me2 deposition in plants. For chromatin targeting, it should be pointed out that distinct mechanisms may be adopted by a given methylase. SUVH6 is not only recognized by the chromatin regulator ASI1 but also able to bind mDNA via the SRA domain, although SUVH6 has been reported to exhibit almost identical binding to all kinds of mDNA (9). Considering that interacting with ASI1 is indispensable for the chromatin targeting of SUVH6 at most target loci (Fig. 4 A and F), we speculate that the mDNA-binding capacity may impart a basal activity upon SUVH6 to catalyze H3K9me2 at mDNA regions but contributes little to the locus-specific deposition compared with ASI1. In addition, ASI1 is known to display a binding preference for TRE-containing genes, which is consistent with a previous report that SUVH6 tends to target transcribed regions in Arabidopsis (10). Intriguingly, AtSUVH5 also possesses a long N-terminal region but lacks the conserved peptide present in SUVH6 homologous proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the AtSUVH5 N-terminus may also be recognized by other unknown chromatin regulators. More importantly, in the AAE complex, both ASI1 and AIPP1 contain an RRM domain that has been shown to possess RNA-binding activity (14, 21). Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that specific binding to nascent RNA by ASI1 and AIPP1 may also contribute to locus-specific H3K9me2 catalysis by SUVH6 family proteins, which deserves further clarification in future studies. In addition, the finding that ASI1 binding at a large number of unique loci is not significantly affected by SUVH6 (Fig. 4 A and G) implies that ASI1 possesses other functions independent of its interaction with SUVH6.

SUVH6-ASI1 Interaction and H3K9me2 Homeostasis Regulation.

In AAE complex-mediated epigenetic regulation, the AAE complex resides in the target loci via EDM2-mediated recognition of H3K9me2 and possibly RNA-binding capacity mediated by ASI1 and AIIPP1 (14, 17, 18, 21). The anchorage of ASI1 at target loci makes the recruitment of SUVH6 possible, further promoting the deposition of H3K9me2. Therefore, the SUVH6-ASI1 interaction forms a self-reinforcing loop for the accumulation of H3K9me2 at target loci. To initiate such a regulatory loop, basal DNA methylation will be needed. We propose that other H3K9me2 MTases, including SUVH4, SUVH5, and even SUVH6 itself, act in the initiation step by facilitating CMT3 and CMT2 function to methylate DNA. Supporting this hypothesis, such regulatory loop cannot be stably formed at the DNA-hypomethylated regions targeted by ASI1 but not SUVH6 (Fig. 4 A and G).

We also noticed that some ASI1 and SUVH6 target loci display a stronger H3K9me2 reduction in suvh6 asi1 double mutant in comparison with single mutants, although such loci are very few relative to those loci without additive effect. Chromatin feature analyses indicated a positive correlation between the proportion of TE, H3K9me2 levels, and the reduction in double mutant (Fig. 5 D–F). This is consistent with the known knowledge that most TEs are epigenetically silenced by heterochromatic marks including H3K9me2. Meanwhile, we found that H3K9me2 level was reduced to very low level in suvh6 asi1 double mutant at these loci. This is conflict with the known concept that SUVH6 works redundantly with SUVH4 and SUVH5 at most H3K9me2 loci. We suspect that, at most SUVH6/ASI1 target loci (Fig. 5D, Var < 1), other SUVHs provide a basal H3K9me2 deposition and DNA methylation, which facilitates the recruitment of SUVH6-ASI1 module for additional H3K9me2 deposition. But at the few loci showing additive effect in suvh6 asi1 mutant, SUVH6 and ASI1 may possess partially independent functions. Meanwhile, SUVH6-ASI1 module may function equally or independently with other SUVHs to promote H3K9me2 deposition. This notion is supported by the H3K9me2 ChIP qPCR results, in which H3K9me2 level was reduced to the similarly low level in suvh6 asi1 and suvh4/5 mutants (Fig. 5C, AT1G25430) and H3K9me2 level was further reduced in the suvh4/5/6 mutant. For the latter case, more evidence from SUVH4/5 ChIP-seq in suvh6 asi1 double mutant and SUVH6-ASI1 ChIP-seq in suvh4/5 double mutant will be required in the future study.

Methods

Details are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods, including plant materials and growth conditions, immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry and co-immunoprecipitation assay, protein interaction assays, ChIP-seq assays and data processing, mRNA-seq and gene expression analysis, protein expression and purification, crystallization, data collection, and structure determination, ITC, and PAT-seq assay.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs at beamline BL19U1 of the National Center for Protein Sciences Shanghai (NCPSS) at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for data collection. C.-G.D. was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB27040203). J.D. was supported by this project and was supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20200109110403829 and KQTD20190929173906742) and the Key Laboratory of Molecular Design for Plant Cell Factory of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes (2019KSYS006).

Author contributions

J.Z., J.D., and C.-G.D. designed research; J.Z., J.Y., L.C., L.-Y.Y., and S.C. performed research; J.Z., J.Y., J.L., L.C., L.P., C.-H.W., J.D., and C.-G.D. analyzed data; and J.D. and C.-G.D. wrote the paper.

Competing interest

The authors declare competing interest. The authors have research support to disclose, Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB27040203).

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Contributor Information

Jiamu Du, Email: dujm@sustech.edu.cn.

Cheng-Guo Duan, Email: cgduan@cemps.ac.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with the accession code: 7XPJ and 7XPK. The ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, and PAT-seq data have been deposited in NCBI SRA with the bioproject number PRJNA841386 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA841386?reviewer=cijqqhm9ma9039ciokbs3gn066). The PAT-seq data of Col-0 and asi1 mutant were adopted from our published data deposited in NCBI SRA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA526574/) with the bioproject number PRJNA526574. The PAT-seq data of osasi1 mutant were adopted from our published data which have been submitted to the NCBI BioProject database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) with accession no. PRJNA673072. All other data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Barski A., et al. , High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129, 823–837 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozzetta C., Boyarchuk E., Pontis J., Ait-Si-Ali S., Sound of silence: The properties and functions of repressive Lys methyltransferases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 499–513 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu H., Du J., Structure and mechanism of histone methylation dynamics in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 67, 102211 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du J., Johnson L. M., Jacobsen S. E., Patel D. J., DNA methylation pathways and their crosstalk with histone methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 519–532 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao L., et al. , DNA methylation underpins the epigenomic landscape regulating genome transcription in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 23, 1–21 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du J., et al. , Mechanism of DNA methylation-directed histone methylation by KRYPTONITE. Mol. Cell 55, 495–504 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson L. M., et al. , The SRA methyl-cytosine-binding domain links DNA and histone methylation. Curr. Biol. 17, 379–384 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du J., et al. , Dual binding of chromomethylase domains to H3K9me2-containing nucleosomes directs DNA methylation in plants. Cell 151, 167–180 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., et al. , Mechanistic insights into plant SUVH family H3K9 methyltransferases and their binding to context-biased non-CG DNA methylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E8793–E8802 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.M. L. Ebbs, Bender J., Locus-specific control of DNA methylation by the Arabidopsis SUVH5 histone methyltransferase. Plant Cell 18, 1166–1176 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padeken J., Methot S. P., Gasser S. M., Establishment of H3K9-methylated heterochromatin and its functions in tissue differentiation and maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 623–640 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaute O., Nicolas E., Vandel L., Trouche D., Functional and physical interaction between the histone methyl transferase Suv39H1 and histone deacetylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 475–481 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu C.-W., et al. , HISTONE DEACETYLASE6 acts in concert with histone methyltransferases SUVH4, SUVH5, and SUVH6 to regulate transposon silencing. Plant Cell 29, 1970–1983 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X., et al. , RNA-binding protein regulates plant DNA methylation by controlling mRNA processing at the intronic heterochromatin-containing gene IBM1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15467–15472 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duan C.-G., et al. , A protein complex regulates RNA processing of intronic heterochromatin-containing genes in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E7377–E7384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y. Z., et al. , Genome-wide distribution and functions of the AAE complex in epigenetic regulation in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 707–722 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lei M., et al. , Arabidopsis EDM2 promotes IBM1 distal polyadenylation and regulates genome DNA methylation patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 527–532 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsuchiya T., Eulgem T., An alternative polyadenylation mechanism coopted to the Arabidopsis RPP7 gene through intronic retrotransposon domestication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E3535–E3543 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuchiya T., Eulgem T., The PHD-finger module of the Arabidopsis thalianadefense regulator EDM2 can recognize triplymodified histone H3 peptides. Plant Signal. Behav. 9, e29202 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saze H., et al. , Mechanism for full-length RNA processing of Arabidopsis genes containing intragenic heterochromatin. Nat. Commun. 4, 2301 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai Y., et al. , The Arabidopsis RRM domain protein EDM3 mediates race-specific disease resistance by controlling H3K9me2-dependent alternative polyadenylation of RPP7 immune receptor transcripts. Plant J. 97, 646–660 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You L., et al. , Intragenic heterochromatin-mediated alternative polyadenylation modulates MiRNA and pollen development in rice. New Phytol. 232, 835–852 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espinas N. A., et al. , Transcriptional regulation of genes bearing intronic heterochromatin in the rice genome. PLOS Genet. 16, e1008637 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qin F. J., Sun Q. W., Huang L. M., Chen X. S., Zhou D. X., Rice SUVH histone methyltransferase genes display specific functions in chromatin modification and retrotransposon repression. Mol. Plant 3, 773–782 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang N., Xu R. M., Structure and function of the BAH domain in chromatin biology. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48, 211–221 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian S., et al. , Dual recognition of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 by a plant histone reader SHL. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Z., et al. , EBS is a bivalent histone reader that regulates floral phase transition in Arabidopsis. Nat. Genet. 50, 1247–1253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y. Z., et al. , Coupling of H3K27me3 recognition with transcriptional repression through the BAH-PHD-CPL2 complex in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 11, 6212 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan H., et al. , BAHCC1 binds H3K27me3 via a conserved BAH module to mediate gene silencing and oncogenesis. Nat. Genet. 52, 1384–1396 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuo A. J., et al. , The BAH domain of ORC1 links H4K20me2 to DNA replication licensing and Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Nature 484, 115–119 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ren W., et al. , DNMT1 reads heterochromatic H4K20me3 to reinforce LINE-1 DNA methylation. Nat. Commun. 12, 2490 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajakumara E., et al. , PHD finger recognition of unmodified histone H3R2 links UHRF1 to regulation of Euchromatic gene expression. Mol. Cell 43, 275–284 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with the accession code: 7XPJ and 7XPK. The ChIP-seq, RNA-seq, and PAT-seq data have been deposited in NCBI SRA with the bioproject number PRJNA841386 (https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA841386?reviewer=cijqqhm9ma9039ciokbs3gn066). The PAT-seq data of Col-0 and asi1 mutant were adopted from our published data deposited in NCBI SRA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA526574/) with the bioproject number PRJNA526574. The PAT-seq data of osasi1 mutant were adopted from our published data which have been submitted to the NCBI BioProject database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/) with accession no. PRJNA673072. All other data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.