Abstract

Infections with enteric pathogens have a high mortality and morbidity burden, as well as significant social and economic costs. Poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions are the leading risk factors for enteric infections, and prevention in low-income countries is still primarily focused on initiatives to improve access to improved WASH facilities. Rural communities in developing countries, on the other hand, have limited access to improved WASH services, which may result in a high burden of enteric infections. Limited information also exists about the prevalence of enteric infections and management practices among rural communities. Accordingly, this study was conducted to assess enteric infections and management practices among communities in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia. A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 1190 randomly selected households in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia. Data were collected using structured and pretested interviewers-administered questionnaire and spot-check observations. We used self-reports and medication history audit to assess the occurrence of enteric infections among one or more of the family members in the rural households. Multivariable binary logistic regression model was used to identify factors associated with enteric infections. Statistically significant association was declared on the basis of adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval and p value < 0.05. Out of a total of 1190 households, 17.4% (95% CI: 15.1, 19.7%) of the households reported that one or more of the family members acquired one or more enteric infections in 12 months period prior to the survey and 470 of 6089 (7.7%) surveyed individuals had one or more enteric infections. The common enteric infections reported at household-level were diarrhea (8.2%), amoebiasis (4.1%), and ascariasis (3.9%). Visiting healthcare facilities (71.7%), taking medications without prescriptions (21.1%), and herbal medicine (4.5%) are the common disease management practices among rural households in the studied region. The occurrence of one or more enteric infections among one or more of the family members in rural households in 12 months period prior to the survey was statistically associated with presence of livestock (AOR: 2.24, 95% CI:1.06, 4.75) and households headed by uneducated mothers (AOR: 1.62, 95% CI: (1.18, 2.23). About one-fifth of the rural households in the studied region reported that one or more of the family members had one or more enteric infections. Households in the study area might acquire enteric infections from different risk factors, mainly poor WASH conditions and insufficient separation of animals including their feces from human domestic environments. It is therefore important to implement community-level interventions such as utilization of improved latrine, protecting water sources from contamination, source-based water treatment, containment of domestic animals including their waste, community-driven sanitation, and community health champion.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Diseases, Gastroenterology, Risk factors

Introduction

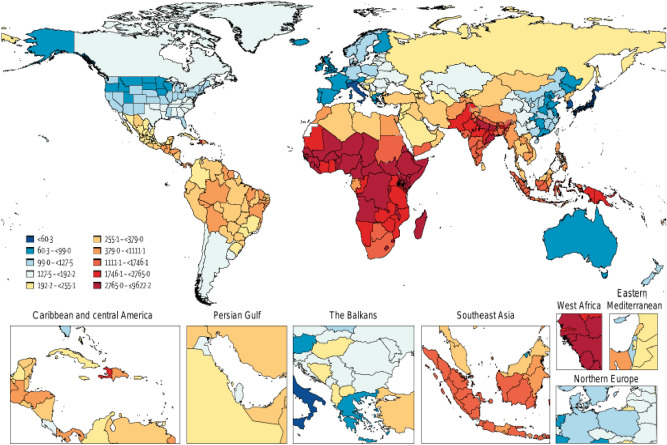

Enteric diseases are caused by micro-organisms such as viruses, bacteria and parasites that cause intestinal illness. The illnesses most frequently result from consuming contaminated food or water, and some can spread from person to person 1. Infections with enteric pathogens have a high mortality and morbidity burden, as well as significant social and economic costs. In 2019, there were 6.60 billion incident cases and 98.8 million prevalent cases of enteric infections, resulting in 1.75 million deaths, and 96.8 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), where the problem is disproportionately high in the global south (low to middle-income countries)2. Figure 1 illustrates age-standardized DALY rates (per 100 000) by location.

Figure 1.

Age-standardized DALY rates (per 100 000) by location, both sexes combined, 2019 (source: https://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/enteric-infections-level-2-cause)2.

Environmental factors such as poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions are among the leading risk factors for enteric infections. Poor WASH conditions are likely to lead to contamination of hands, water, foods, and the environment, resulting in the spread of fecal organisms3,4. When pathogens are transmitted via environmental media, a dynamic interaction between pathogen, host, and environment determines whether the host becomes infected or develops symptoms. Pathogen phenotypes, host physiology, and environmental factors can all lead to an increase or decrease in infection risk. Furthermore, people differ in terms of physiologic or immune factors and likelihood of exposure that alter the likelihood of infection5–8.

Obviously, different strategies are recommended to prevent and reduce enteric infections and their consequences in various parts of the world. Prevention in low-income countries remains primarily focused on initiatives to ensure (i) access to safe drinking water and sanitation, (ii) food safety, and (iii) environmental protection9. Sanitation aims to prevent contamination of the environment by excreta and, therefore, to prevent transmission of pathogens that originate in feces of an infected person10,11. There are numerous technologies and methods available to accomplish this, including sophisticated and high-cost methods such as waterborne sewage systems and simple low-cost methods such as the cat method, which involves digging a hole and covering feces with soil after defecation11,12. Water supply aims to provide the community with safe or clean and adequate water from accessible and affordable improved water sources13. Furthermore, because universal safe and reliable water supply remains an elusive goal for the vast majority of the world’s population, household-level water treatment (HWT) has been proposed as a stopgap solution to provide safer drinking water at the point of use14,15. Food hygiene interventions, such as the promotion of reheating foods, preventing contact with flies and hand washing before feeding intends to keep food from becoming contaminated16,17. To this end, awareness programs will continue to play an important role in preventing the spread of infections. Furthermore, empowering society to play a more active role in the prevention of infections such as water and food-borne illnesses is critical18,19. However, rural communities in developing countries have limited access to improved WASH services which may lead to high burden of enteric infections20. Limited information also exists about the prevalence of enteric infections and management practices among rural communities. Accordingly, this study was conducted to assess enteric infections and management practices among communities in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study with structured observation was conducted among rural households in Central and North Gondar administrative zones of the Amhara national regional state, Ethiopia in May 2016. Central Gondar zone covers thirteen districts and North Gondar zone covers seven districts. The total population residing in Central Gondar is estimated to be 2,896,928 and it is estimated to be 912,112 in North Gondar zone21.

Sample size calculation and sampling procedures

The sample size (i.e., 1210 rural households) was calculated using single population proportion formula and the target households were included in the study using systematic random sampling technique. The sample size calculation and sampling procedures are described in more detail elsewhere22.

Data collection tools and procedures

Data were collected using a structured and pretested interviewers-administered questionnaire and spot-check observations (supplementary file 1). The questionnaire and observation checklists were prepared based on a review of relevant literature. The questionnaire was first prepared in English language and translated to the local Amharic language by two native Amharic speakers fluent in English, and back-translated into English by two independent English language experts fluent in Amharic to check consistency. The questionnaire was organized in to three parts: (i) socio-demographic information; (ii) WASH conditions; and (iii) enteric infections, management practices, and associated deaths. Data were collected by public health experts and the data collection was closely supervised by field supervisors.

Measurement of variables

The primary outcome variable for this study was prevalence of enteric infections among one or more of the family members in rural households of northwest Ethiopia. Prevalence of enteric infections was defined as the occurrence of one or more gastrointestinal health problems (such as cholera, typhoid fever, salmonellosis, diarrhea, amoebiasis, giardiasis, ascariasis, hookworm, and schistosomiasis) in 12 months period prior to the survey. The household head was asked about the occurrence of the aforementioned health problems among any of the family members. To make it clear to the participants, we used the local names for each disease. Furthermore, we checked the medication history of individuals who visited health facilities to identify the specific diseases confirmed by the physicians.

Latrine facilities (one of the predictors) were taken as “improved” if the household used clean, well-maintained, and unshared latrine facilities such as pit latrines (including ventilated pit latrines) which are accessible at night use and has functional handwashing facilities23. Drinking water sources (the other predictor) were taken as “improved” if the sources have the potential to deliver safe water by nature of their design and construction, and include pipeline, public taps, protected wells, protected springs, and protected rain catchments24.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered using EPI-INFO version 3.5.3 statistical package and exported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for further analysis. Descriptive statistics, such as frequency and percentage were used to present the data. We included predictors to the multivariable binary logistic regression model from the literature regardless of their bivariate p value to identify factors associated with enteric infections among rural households. Statistically significant association was declared on the basis of adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and p values < 0.05. Model fitness was check using Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Gondar (reference number: V/P/RCS/05/1520/2016). There were no risks due to participation and the collected data were used only for this research purpose with complete confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained from household heads. All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Of a total of 1210 rural households, 1190 households participated in the current study, with a response rate of 98.3%. A total of 6089 individuals (3187 males and 2902 females) were surveyed in 1190 households and 513 (43.1%) of the households had more than five family members. Over three quarter, 888 (75.3%) of the female heads did not receive formal education and 643 (59.3%) of the male heads did not attend formal education. The vast majority, 1123 (95.2%) of the female heads were farmers by their occupation and 1045 (96.3%) of the male heads were also farmers. Majority of the households, 1113 (85.1%) had one or more children, out of which 467 (39.2%) had children under the age of six years. One hundred and forty-seven (12.4%) of the households reported that one or more of the family members had vision impairment and 52 (4.4%) of the households reported that one or more of their family members had difficulty of mobility. One thousand and eighty-one (90.8%) of the households had one or more domestic animals in which their excrement is not contained from the living environment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of households (n = 1190) in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia, May 2016.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Family size of households (n = 1190) | ||

| < 5 | 677 | 56.9 |

| > 5 | 513 | 43.1 |

| Number of individuals surveyed in 1190 households (n = 6089) | ||

| Male | 3187 | 52.3 |

| Female | 2902 | 47.7 |

| Maternal education (n = 1180) | ||

| No formal education | 888 | 75.3 |

| Attend formal education | 292 | 24.7 |

| Paternal education (n = 1085) | ||

| No formal education | 643 | 59.3 |

| Attend formal education | 442 | 40.7 |

| Maternal occupation (n = 1180) | ||

| Farmer | 1123 | 95.2 |

| Merchant | 35 | 3.0 |

| Government employee | 8 | 0.7 |

| Student | 3 | 0.3 |

| Daily Laborer | 11 | 0.9 |

| Paternal occupation | ||

| Farmer | 1045 | 96.3 |

| Merchant | 22 | 2.0 |

| Government employee | 9 | 0.8 |

| Daily Laborer | 9 | 0.8 |

| The household has a child/child (n = 1190) | ||

| < 1 year old children | 75 | 6.3 |

| 1–5 years old children | 392 | 32.9 |

| 6–10 years old children | 228 | 19.2 |

| 11–14 years old children | 318 | 26.7 |

| The household has no children | 177 | 14.9 |

| One or more of the family members have vision impairment | ||

| Yes | 147 | 12.4 |

| No | 1043 | 87.6 |

| One or more of the family members have difficulty of mobility | ||

| Yes | 52 | 4.4 |

| No | 1138 | 95.6 |

| Th household has livestock* | ||

| No | 109 | 9.2 |

| Ox | 839 | 70.5 |

| Cow | 858 | 72.1 |

| Sheep | 567 | 47.6 |

| Goat | 128 | 10.8 |

| Horse | 355 | 29.8 |

| Mule | 90 | 7.6 |

| Donkey | 326 | 27.4 |

| Hen | 47 | 3.9 |

*Households had two or more livestock.

WASH conditions

Five hundred and sixty-five (47.5%) of the households reported that they received WASH education and 967 (81.3%) of the households reported that they have been regularly supervised by health professionals. The vast majority, 1100 (92.4%) of the households had no access to improved sanitation facilities. About one-fifth, 233 (19.6%) of the households collected drinking water from unimproved sources. Moreover, food items in 312 (26.2%) of the households were not protected from pets and mechanical vectors such as common house flies had been observed in food storage areas among 238 (20.0%) of the households (Table 2).

Table 2.

Water, sanitation and hygiene conditions of households (n = 1190) in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia, May 2016.

| WASH conditions | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| WASH education | ||

| Yes | 565 | 47.5 |

| No | 625 | 52.5 |

| Health professionals’ regular supervision | ||

| Yes | 967 | 81.3 |

| No | 223 | 18.7 |

| Access to improved latrine | ||

| No | 1100 | 92.4 |

| Yes | 90 | 7.6 |

| Drinking water sources | ||

| Unimproved | 233 | 19.6 |

| Improved | 957 | 80.4 |

| Food items are protected from pets | ||

| Yes | 878 | 73.8 |

| No | 312 | 26.2 |

| Presence of mechanical vectors in food storage areas | ||

| Yes | 238 | 20.0 |

| No | 952 | 80.0 |

Enteric infections and management practices

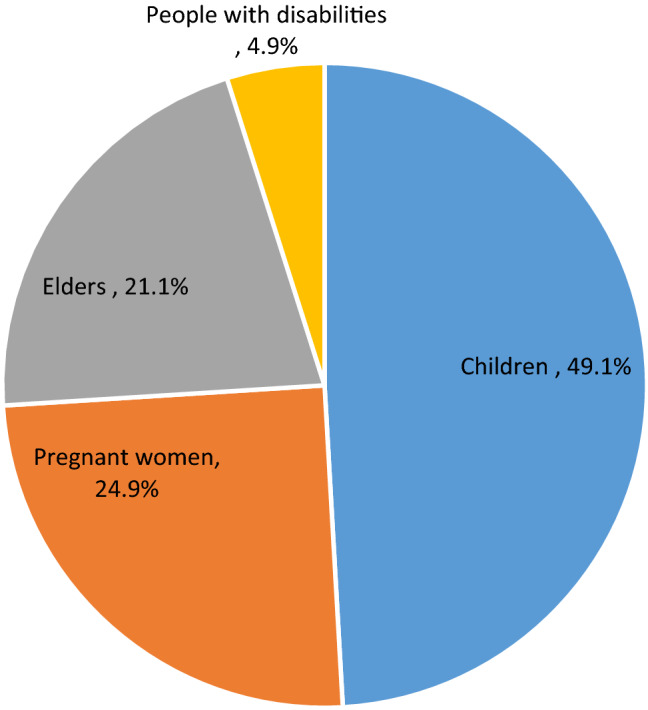

Out of a total of 1190 households, 207 (17.4%) (95% CI: 15.1, 19.7%) of the households reported that one or more of the family members acquired one or more enteric infections in 12 months period prior to the survey and 470 of 6089 (7.7%) individuals had one or more enteric infections, of which 231 of 470 (49.1%) were children under the age of 14 years (Fig. 2). The common enteric infections reported at household-level were diarrhea [97 (8.2%)], amoebiasis [49 (4.1%)], and ascariasis [46 (3.9%)]. In the current study 337 of 470 (71.7%) and 98 of 470 (21.1%) individuals who had one or more enteric infections visited healthcare facilities and took medications without prescriptions, respectively to manage the infection/s. Out of 470 individuals who acquired one or more enteric infections, 7 (1.5%) of them died due to the infection/s (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of enteric infections among vulnerable groups of the community in a rural northwest Ethiopia, May 2016 (note: elders were family members aged above 64 years).

Table 3.

Enteric infections, management practice, and associated deaths among communities in a rural northwest Ethiopia, May 2016.

| Enteric infections reported | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Common enteric infections reported at household level (n = 1190) * | ||

| Diarrhea† | 97 | 8.2 |

| Amoebiasis‡ | 49 | 4.1 |

| Ascariasis‡ | 46 | 3.9 |

| Tapeworm‡ | 26 | 2.2 |

| Cholera‡ | 22 | 1.8 |

| Typhoid fever‡ | 18 | 1.5 |

| Salmonellosis‡ | 17 | 1.4 |

| Giardiasis‡ | 10 | 0.8 |

| Hookworm‡ | 3 | 0.3 |

| Schistosomiasis‡ | 2 | 0.2 |

| Management of enteric infections (n = 470) | ||

| Visit healthcare facilities | 337 | 71.7 |

| Taking medication without prescription | 98 | 21.1 |

| Use traditional medicine | 21 | 4.5 |

| No action | 16 | 3.4 |

| Number of deaths reported due to above disease/s (n = 470) | ||

| Male | 5 | 1.1 |

| Female | 2 | 0.4 |

| No death | 463 | 98.5 |

*There were households who reported two or more enteric infections.

†Self-reported.

‡Checked from medication history.

Factors associated with enteric infections

Access to improved latrine facilities, drinking water sources, mechanical vectors seen in food storage area, protection of food items from pets, presence of livestock, health education, regular health supervision, maternal education, and paternal education were the variables entered in to the adjusted model. The occurrence of one or more enteric infections among one or more of the family members in rural households in 12 months period prior to the survey was statistically associated with presence of livestock and maternal education. The odds of acquiring one or more enteric infections among one or more of the family members in rural households was 2.24 times higher among households who owned one or more livestock compared with households with no live stock (AOR: 2.24, 95% CI:1.06, 4.75). Similarly the odds of enteric infections among rural households was 1.62 times higher among households headed by mothers who did not attend formal education compared with their counterparts (AOR: 1.62, 95% CI: (1.18, 2.23) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with enteric infections among households (n = 1190) in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia, May 2016.

| Variables | Enteric infections | COR with 95% CI | AOR with 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Access to improved latrine facilities | ||||

| No | 193 | 907 | 1.16 (0.64, 2.09) | 1.30 (0.70, 2.44) |

| Yes | 14 | 76 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Drinking water sources | ||||

| Unimproved | 38 | 195 | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) | 0.89 (0.60,1.33) |

| Improved | 169 | 788 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Vectors seen in food storage area | ||||

| Yes | 43 | 195 | 1.06 (0.73, 1.54) | 1.09 (0.74, 1.60) |

| No | 164 | 788 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Food items protected from pets | ||||

| Yes | 155 | 723 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 52 | 260 | 0.93 (0.66, 1.32) | 0.87 (0.60, 1.25) |

| Presence of livestock | ||||

| No | 9 | 100 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Yes | 198 | 883 | 2.49 (1.24, 5.01) | 2.24 (1.06, 4.75)* |

| Health education | ||||

| Yes | 99 | 466 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 108 | 517 | 0.98 (0.73, 1.33) | 1.10 (0.79, 1.55) |

| Regular supervision | ||||

| Yes | 173 | 794 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| No | 34 | 189 | 0.83 (0.55, 1.23) | 0.85 (0.55, 1.33) |

| Maternal education | ||||

| No formal education | 161 | 727 | 1.18 (0.83, 1.69) | 1.62 (1.18, 2.23)** |

| Attend formal education | 46 | 246 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Paternal education | ||||

| No formal education | 112 | 531 | 0.89 (0.65, 1.21) | 0.79 (0.56, 1.10) |

| Attend formal education | 85 | 357 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

*statistically significant at p < 0.05,** statistically significant at p < 0.01, Hosmer and Lemeshow test: 0.238, AOR Adjusted odds ratio, CI Confidence interval, and COR Crude odds ratio.

Discussion

This is a community-based cross-sectional study conducted to assess enteric infections among households in a rural setting of northwest Ethiopia and found that 17.4% (95% CI: 15.1, 19.7%) of the households reported that one or more of the family members acquired one or more enteric infections in 12 months period prior to the survey. Out of 6089 individuals surveyed in all the households, 7.7% individuals had one or more enteric infections. The prevalence of enteric infections reported in the current study is lower than findings of studies in rural Lao, 98.3%3 and in a rural area and urban slum of Vellore, India, 31%25. This low prevalence is due to limitations of the methods we used, i.e., self-report and medication history audit. The self-reported data may not be reliable since the study subjects may make the more socially acceptable answer rather than being truthful and they may not be able to assess themselves accurately. Moreover, we checked the medication history to identify the specific diseases and we asked the household heads to tell us the name of the diseases confirmed by the physicians for individuals who visited health facilities. These methods may underestimate the prevalence of enteric infections since the health seeking behavior of the rural communities in the study areas is very low.

According to this study, the most common disease management practices among rural households in the studied region are visiting healthcare facilities, taking medications without a prescription, and using herbal medicine. Since Ethiopia has notable progress in expanding healthcare facilities at all levels, access to healthcare services for the rural communities is rapidly increasing over the past decades. This results in an increase in the use of healthcare services26,27. Moreover, there is credible community health promotion and public involvement through the health extension program28,29. All these help the rural communities to use modern medicine for disease management in the area. On the other hand, there is still healthcare disparities in the rural communities, which lead the communities to use herbal medicines30,31. Moreover, since there is no strong regulatory system in Ethiopia, over the counter or non-prescription sale of antibiotics is a common practice in the country32,33. Unless this practice is resolved, it may create critical public health problems, such as drug resistance34,35.

The occurrence of one or more enteric infections among one or more of the family members in rural households in 12 months period prior to the survey was statistically associated with presence of livestock. This finding is in agreement with findings of other studies36–40. The association between enteric infections and domestic animals can be due to the fact that animal husbandry and keeping practices in the rural communities could result human contact with animals or animal feces and contamination of the living environment. Pathogens from animal excreta could reach to humans via fecally contaminated water, soil, foods, and hands41–43. Animal excreta from contaminated living environment could reach to water sources via the help of flooding and could result fecal contamination of water sources which leads exposure to enteric pathogens through drinking of contaminated water or ingestion of foods prepared by fecally contaminated water41,44. Hands could also be contaminated while the rural communities performed their day-to-day tasks in the fecally contaminated living environment which help pathogens to reach to humans via a direct hand-to-mouth contact or via food contamination from unwashed hands41,45,46. Presence of animal excreta in the living environment on the other hand creates favorable conditions for mechanical vectors which may carry diseases causing pathogens from animal excreta to food items41,47,48. Moreover, food items could be contaminated with pathogens when animals get entered in to the living quarter and accessed prepared and stored foods via their saliva, hairs or fissures, and feet49.

This study also found that enteric infections among one or more of the family members in rural households in 12 months period prior to the survey was statistically associated with maternal education which is in line with findings of other studies50,51. The association between education and enteric infection can be justified that educated mothers may have increased awareness about the transmission and prevention methods of infections, whereas uneducated mothers may not have awareness about diseases transmission and prevention methods. Education is likely to enhance household health and sanitation practices and encourages healthy behavior changes52–54.

As limitations, we couldn’t identify predictors of enteric infections at the individual-level because we have no individual-level data for most of the variables. The self-reported data may not be reliable since the study subjects may make the more socially acceptable answers rather than being truthful and they may not be able to assess themselves accurately, which might result reporting bias. Moreover, a larger study is required to ensure generalizability.

Conclusion

About one-fifth of the rural households in the studied region reported that one or more of the family members had one or more enteric infections in 12 months period prior to the survey and about half of the infected individuals were children under the age of 14 years. Households in the study area might acquire enteric infections from different risk factors, mainly poor WASH conditions and insufficient separation of animals including their feces from human domestic environments. Moreover, more than one-fifth of the individuals who acquired one or more enteric infections took medications without prescription, which may create critical public health problems, such as drug resistance unless regulated. Community-driven sanitation interventions such as promotion of improved latrine construction and utilization, containment of domestic animals including their waste, and controlled disposal of domestic wastewater and rubbish should be critically implemented in the area. Preventing contamination of drinking water at its source (such as water source protection and source-based water treatment) and at point of use (such as safe water storage and home-based water treatment) is very important. Furthermore, community health champion, health and sanitation education, and proper use of medications should be in placed to improve health, sanitation, and health seeking behaviors of the community.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are pleased to acknowledge study participants, data collectors, and field supervisors for participation. Authors also acknowledged the University of Gondar for funding the field work and questionnaire duplication.

Author contributions

The study was designed by Z.G. All the authors participated during data collection, data processing and coding, and analysis and interpretation of findings. Z.G. prepared the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript. This manuscript does not contain any individual person's data.

Funding

The research project was funded by the University of Gondar (Grand number: R/T/T/C/Eng./250/08/2016).

Data availability

Data will be made available upon requesting the primary author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-29556-2.

References

- 1.Kolling G, Wu M, Guerrant RL. Enteric pathogens through life stages. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012;2:114. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IHME. Enteric infections-Level 2 cause. Global Health Metrics. Available at https://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/enteric-infections-level-2-cause. Accessed on 27 September 2022. .

- 3.Chard AN, Levy K, Baker KK, Tsai K, Chang HH, Thongpaseuth V, Sistrunk JR, Freeman MC. Environmental and spatial determinants of enteric pathogen infection in rural Lao People’s Democratic Republic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020;14(4):e0008180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker KK, O’Reilly CE, Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Ayers TL, Farag TH, Nasrin D, Blackwelder WC, Wu Y. Sanitation and hygiene-specific risk factors for moderate-to-severe diarrhea in young children in the global enteric multicenter study, 2007–2011: Case-control study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balbus JM, Embrey MA. Risk factors for waterborne enteric infections. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2002;18(1):46–50. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engering A, Hogerwerf L, Slingenbergh J. Pathogen–host–environment interplay and disease emergence. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2013;2(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/emi.2013.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alizon S, Hurford A, Mideo N, Van Baalen M. Virulence evolution and the trade-off hypothesis: History, current state of affairs and the future. J. Evol. Biol. 2009;22(2):245–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Méthot P-O, Alizon S. What is a pathogen? Toward a process view of host-parasite interactions. Virulence. 2014;5(8):775–785. doi: 10.4161/21505594.2014.960726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WDHD. Enteric Infections: Prevention & Management. World Digestive Health Day | May 29, 2011. Available at https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/UserFiles/file/wdhd-2011-supplement.pdf. Accessed on 28 September 2022.

- 10.Freeman MC, Garn JV, Sclar GD, Boisson S, Medlicott K, Alexander KT, Penakalapati G, Anderson D, Mahtani AG, Grimes JE. The impact of sanitation on infectious disease and nutritional status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2017;220(6):928–949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown J, Cairncross S, Ensink JH. Water, sanitation, hygiene and enteric infections in children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013;98(8):629–634. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-301528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson KL, Murray A. Sanitation for unserved populations: technologies, implementation challenges, and opportunities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008;33:119–151. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter PR, MacDonald AM, Carter RC. Water supply and health. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1000361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mintz ED, Reiff FM, Tauxe RV. Safe water treatment and storage in the home: A practical new strategy to prevent waterborne disease. JAMA. 1995;273(12):948–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO). Combating waterborne disease at the household level. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/51808/retrieve. Accessed on 28 September 2022.

- 16.Simiyu S, Czerniewska A, Aseyo ER, Baker KK, Cumming O, Mumma JAO, Dreibelbis R. Designing a food hygiene intervention in low-income, peri-urban context of Kisumu, Kenya: Application of the trials of improved practices methodology. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;102(5):1116. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.19-0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gautam O. Food hygiene intervention to improve food hygiene behaviours, and reduce food contamination in Nepal: an exploratory trial. London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (2015).

- 18.Tsioutis C, Birgand G, Bathoorn E, Deptula A, Ten Horn L, Castro-Sánchez E, Săndulescu O, Widmer AF, Tsakris A, Pieve G. Education and training programmes for infection prevention and control professionals: Mapping the current opportunities and local needs in European countries. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2020;9(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Questa K, Das M, King R, Everitt M, Rassi C, Cartwright C, Ferdous T, Barua D, Putnis N, Snell A. Community engagement interventions for communicable disease control in low-and lower-middle-income countries: evidence from a review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01169-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prüss-Ustün A, Bartram J, Clasen T, Colford JM, Jr, Cumming O, Curtis V, Bonjour S, Dangour AD, De France J, Fewtrell L. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low-and middle-income settings: A retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries. Tropical Med. Int. Health. 2014;19(8):894–905. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lankir D, Solomon S, Gize A. A five-year trend analysis of malaria surveillance data in selected zones of Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gizaw Z, Engdaw GT, Nigusie A, Gebrehiwot M, Destaw B. Human ectoparasites are highly prevalent in the rural communities of Northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Insights. 2021;15:11786302211034463. doi: 10.1177/11786302211034463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Exley JL, Liseka B, Cumming O, Ensink JHJ. The sanitation ladder, what constitutes an improved form of sanitation? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49(2):1086–1094. doi: 10.1021/es503945x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The JMP service ladder for drinking water. Available at https://washdata.org/monitoring/drinking-water. Accessed on 26 September 2022.

- 25.Collinet-Adler, S., & Naumova, E. Environmental indicators of enteric infections in a rural area and urban slum of Vellore, India (2010).

- 26.Croke K. The origins of Ethiopia's primary health care expansion: the politics of state building and health system strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(10):1318–1327. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Misganaw A, Naghavi M, Walker A, Mirkuzie AH, Giref AZ, Berheto TM, Waktola EA, Kempen JH, Eticha GT, Wolde TK. Progress in health among regions of Ethiopia, 1990–2019: A subnational country analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1322–1335. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02868-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banteyerga H. Ethiopia's health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC Rev. 2011;13:46–49. doi: 10.37757/MR2011V13.N3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Assefa Y, Gelaw YA, Hill PS, Taye BW, Van Damme W. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: Successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Glob. Health. 2019;15(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0470-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mbali H, Sithole JJK, Nyondo-Mipando AL. Prevalence and correlates of herbal medicine use among Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) clients at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Blantyre Malawi: A cross-sectional study. Malawi Med. J. 2021;33(3):153–158. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v33i3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014;4:177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suleman S, Woliyi A, Woldemichael K, Tushune K, Duchateau L, Degroote A, Vancauwenberghe R, Bracke N, De Spiegeleer B. Pharmaceutical regulatory framework in Ethiopia: A critical evaluation of its legal basis and implementation. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2016;26(3):259–276. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v26i3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gebretekle GB, Serbessa MK. Exploration of over the counter sales of antibiotics in community pharmacies of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Pharmacy professionals’ perspective. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2016;5(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0101-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adhikari B, Pokharel S, Raut S, Adhikari J, Thapa S, Paudel K, Narayan G, Neupane S, Neupane SR, Yadav R. Why do people purchase antibiotics over-the-counter? A qualitative study with patients, clinicians and dispensers in central, eastern and western Nepal. BMJ Glob. Health. 2021;6(5):e005829. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koji EM, Gebretekle GB, Tekle TA. Practice of over-the-counter dispensary of antibiotics for childhood illnesses in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A simulated patient encounter study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2019;8(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0571-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zambrano LD, Levy K, Menezes NP, Freeman MC. Human diarrhea infections associated with domestic animal husbandry: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014;108(6):313–325. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/tru056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnes AN, Anderson JD, Mumma J, Mahmud ZH, Cumming O. The association between domestic animal presence and ownership and household drinking water contamination among peri-urban communities of Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(6):e0197587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belongia EA, Chyou P-H, Greenlee RT, Perez-Perez G, Bibb WF, DeVries EO. Diarrhea incidence and farm-related risk factors for Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Campylobacter jejuni antibodies among rural children. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187(9):1460–1468. doi: 10.1086/374622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conan A, O’Reilly CE, Ogola E, Ochieng JB, Blackstock AJ, Omore R, Ochieng L, Moke F, Parsons MB, Xiao L. Animal-related factors associated with moderate-to-severe diarrhea in children younger than five years in western Kenya: a matched case-control study. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11(8):e0005795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gizaw Z, Addisu A, Guadie D. Common gastrointestinal symptoms and associated factors among Under-5 children in rural Dembiya, Northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Insights. 2020;14:1178630220927361. doi: 10.1177/1178630220927361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gizaw Z, Yalew AW, Bitew BD, Lee J, Bisesi M. Fecal indicator bacteria along multiple environmental exposure pathways (water, food, and soil) and intestinal parasites among children in the rural northwest Ethiopia. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schriewer A, Odagiri M, Wuertz S, Misra PR, Panigrahi P, Clasen T, Jenkins MW. Human and animal fecal contamination of community water sources, stored drinking water and hands in rural India measured with validated microbial source tracking assays. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015;93(3):509. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandey PK, Kass PH, Soupir ML, Biswas S, Singh VP. Contamination of water resources by pathogenic bacteria. AMB Express. 2014;4(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13568-014-0051-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerba C. P. Environmentally transmitted pathogens. In Environmental Microbiology. Elsevier edn, 445–484 (2009).

- 45.Pickering AJ, Davis J, Walters SP, Horak HM, Keymer DP, Mushi D, Strickfaden R, Chynoweth JS, Liu J, Blum A. Hands, water, and health: Fecal contamination in Tanzanian communities with improved, non-networked water supplies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44(9):3267–3272. doi: 10.1021/es903524m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloomfield SF, Aiello AE, Cookson B, O'Boyle C, Larson EL. The effectiveness of hand hygiene procedures in reducing the risks of infections in home and community settings including handwashing and alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2007;35(10):S27–S64. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cocciolo G, Circella E, Pugliese N, Lupini C, Mescolini G, Catelli E, Borchert-Stuhlträger M, Zoller H, Thomas E, Camarda A. Evidence of vector borne transmission of Salmonella enterica enterica serovar Gallinarum and fowl typhoid disease mediated by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae (De Geer, 1778) Parasit. Vectors. 2020;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04393-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graczyk Z, Graczyk T, Naprawska A. A role of some food arthropods as vectors of human enteric infections. Open Life Sci. 2011;6(2):145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gautam OP, Curtis V. Food hygiene practices of rural women and microbial risk for children: Formative research in Nepal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021;105(5):1383. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Júlio C, Vilares A, Oleastro M, Ferreira I, Gomes S, Monteiro L, Nunes B, Tenreiro R, Ângelo H. Prevalence and risk factors for Giardia duodenalis infection among children: A case study in Portugal. Parasit. Vectors. 2012;5(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haque MA, Platts-Mills JA, Mduma E, Bodhidatta L, Bessong P, Shakoor S, Kang G, Kosek MN, Lima AA, Shrestha SK. Determinants of Campylobacter infection and association with growth and enteric inflammation in children under 2 years of age in low-resource settings. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-53533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arlinghaus KR, Johnston CA. Advocating for behavior change with education. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2018;12(2):113–116. doi: 10.1177/1559827617745479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raghupathi V, Raghupathi W. The influence of education on health: An empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Arch. Public Health. 2020;78(1):1–18. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Viinikainen J, Bryson A, Böckerman P, Kari JT, Lehtimäki T, Raitakari O, Viikari J, Pehkonen J. Does better education mitigate risky health behavior? A mendelian randomization study. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2022;46:101134. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2022.101134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon requesting the primary author.