Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This report describes the development of a practice pathway for the identification, evaluation, and management of insomnia in children and adolescents who have autism spectrum disorders (ASDs).

METHODS

The Sleep Committee of the Autism Treatment Network (ATN) developed a practice pathway, based on expert consensus, to capture best practices for an overarching approach to insomnia by a general pediatrician, primary care provider, or autism medical specialist, including identification, evaluation, and management. A field test at 4 ATN sites was used to evaluate the pathway. In addition, a systematic literature review and grading of evidence provided data regarding treatments of insomnia in children who have neurodevelopmental disabilities.

RESULTS

The literature review revealed that current treatments for insomnia in children who have ASD show promise for behavioral/educational interventions and melatonin trials. However, there is a paucity of evidence, supporting the need for additional research. Consensus among the ATN sleep medicine committee experts included: (1) all children who have ASD should be screened for insomnia; (2) screening should be done for potential contributing factors, including other medical problems; (3) the need for therapeutic intervention should be determined; (4) therapeutic interventions should begin with parent education in the use of behavioral approaches as a first-line approach; (5) pharmacologic therapy may be indicated in certain situations; and (6) there should be follow-up after any intervention to evaluate effectiveness and tolerance of the therapy. Field testing of the practice pathway by autism medical specialists allowed for refinement of the practice pathway.

CONCLUSIONS

The insomnia practice pathway may help health care providers to identify and manage insomnia symptoms in children and adolescents who have ASD. It may also provide a framework to evaluate the impact of contributing factors on insomnia and to test the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment strategies for the nighttime symptoms and daytime functioning and quality of life in ASD.

Keywords: actigraphy, education, sleep, sleep latency

Approximately 1 in 110 children fulfills the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) as defined by delayed or abnormal social interaction, language as used in social communication, and/or restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. 1 Children who have ASD are at greater risk for developing sleep problems than typically developing children. Research has documented that the prevalence of sleep disturbances ranges from 53% to 78% for children who have ASD compared with 26% to 32% for typically developing children. 2 , 3

The key components of pediatric insomnia are repeated episodes of difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep, including premature awakenings, leading to insufficient or poor-quality sleep. These episodes result in functional impairment for the child or other family members. 4 In typically developing children, the primary cause of insomnia is behaviorally based. 5 In the ASD population, however, insomnia is multifactorial. It includes not only behavioral issues but also medical, neurologic, and psychiatric comorbidities; it is also an adverse effect of the medications used to treat symptoms of autism and these comorbidities. 6

Typically developing children who have insomnia are at increased risk for neurobehavioral problems such as impairments in cognition, mood, attention, and behavior. 5 , 7 – 9 Similar to the behavioral morbidity associated with pediatric insomnia that is observed in the general population, children who have ASD and sleep problems are prone to more severe comorbid behavioral disturbances compared with children without sleep disturbances. 10 In addition, treating insomnia in children who have neurodevelopmental disorders may improve problematic daytime behaviors. 11

Despite the prevalence of and morbidity associated with pediatric insomnia, there is evidence that sleep disorders in children often go undetected and untreated. 12 – 14 Medical practitioners often do not ask about sleep concerns or parents do not seek assistance. 15 Many parents have poor knowledge about sleep development and sleep problems. 16 This is particularly relevant to children who have ASD, in that parents may present to the pediatrician with concerns regarding aggression, impulsivity, inattention/hyperactivity, or other behavioral issues that may be secondary to a sleep disorder. The contribution of the sleep disorder may be undetected due to emphasis on treating the behavioral issue as opposed to identifying and treating the underlying factors. This deemphasis of underlying factors may be due to the absence of a standardized approach for recognition and treatment of insomnia in children who have ASD.

Guidelines exist for sleep screening and intervention in typically developing children. 17 , 18 Guidelines and empirical support also exist for the effectiveness of behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in children. 18 – 21 Specific behavioral treatments supported include the following: unmodified extinction: leaving the child’s bedroom after putting the child to bed and not returning until morning unless the child is ill or at risk for injury; extinction with parent presence: parent is present in the room with the child but does not interact with him or her; graduated extinction: parent returns to child’s bedroom to attend to child on request or agitation but increases the time in between requests by the child for the parent to return; preventive parent education: providing education to parent on sleep habits and bedtime routine; bedtime fading: delaying bedtime to promote sleep and then “fading” or advancing bedtime once child is falling asleep easier; and scheduled awakenings: awakening the child before a spontaneous awakening. Extinction and parent education have strong empirical support whereas the other interventions are less confidently supported. 18 To our knowledge, however, there are no published guidelines related to management of insomnia in children who have ASD, including screening and treatment. The evidence that children who have ASD are at greater risk for insomnia and its morbidity suggests that sleep screening in this population of children is extremely important. The ideal evaluation of insomnia in children who have ASD involves a comprehensive sleep assessment, as outlined in a recent review. 22

To facilitate the evaluation of children with ASD for insomnia, the Autism Treatment Network (ATN) in association with the National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) worked collaboratively to develop the clinical practice pathway presented in this article. The intention of this clinical practice pathway is to emphasize the need for screening of sleep problems in ASD and to provide a framework for decision-making related to best practices in the care of children and adolescents with ASD in primary care settings, when seen by a general pediatrician, primary care provider, or autism medical specialist. The pathway is not intended to serve as the sole source of guidance in the evaluation of insomnia in children who have ASD or to replace clinical judgment, and it may not provide the only appropriate approach to this challenge.

METHODS

Guideline Development

The ATN Sleep Committee consists of pediatric sleep medicine specialists as well as developmental pediatricians, neurologists, and psychiatrists. The clinical practice pathway was designed to assist primary care providers and others working directly with families affected by ASD in addressing the challenge of insomnia with regard to identification, assessment, and management.

Insomnia was defined as “repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite age-appropriate time and opportunity for sleep that results in daytime functional impairment for the child and/or family.” 18 The responses of the parents to selected questions on the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) 23 identified those patients who have insomnia.

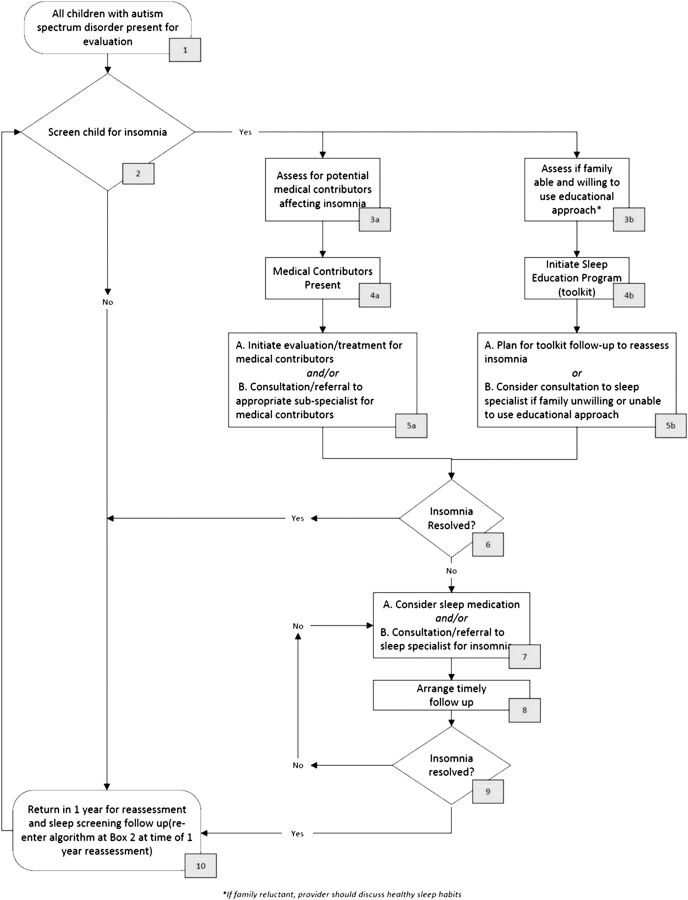

After performing a systemic review of the literature, expert opinion and consensus was used to form the basis of the practice pathway (Fig 1). The ATN Sleep Committee’s knowledge of the literature and applicability to clinical practice informed best practices, which in turn created an overarching approach to insomnia within ATN sites by the autism medical specialist.

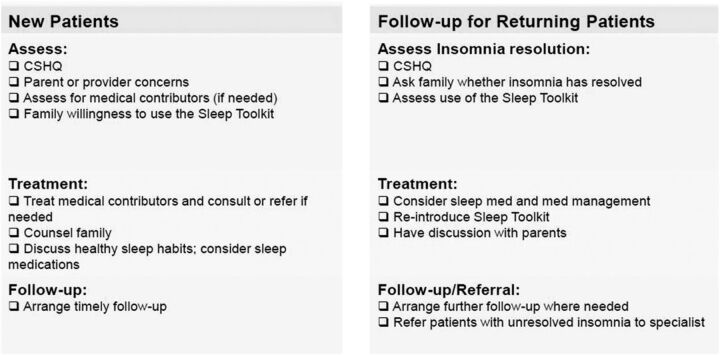

FIGURE 1.

Checklist for carrying out the practice pathway in children who have ASD and insomnia. CSHQ, Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire.

Systematic Review of the Literature

We conducted a systematic literature review to find evidence regarding the treatment of insomnia in children diagnosed with ASD (questions and search terms available on request from the authors). We searched OVID, CINAHL, Embase, Database of Abstracts and Review Database of Abstracts of Reviews and Effects, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews databases, with searches limited to primary and secondary research conducted with humans, published in the English language, involving children aged 0 to 18 years, and published between January 1995 and July 2010. Individual studies were graded by using an adaptation of the GRADE system 24 by 2 primary reviewers and then reviewed by content experts for consensus. Discrepancies were resolved by a third party.

Pilot Testing of the Pathway

The ATN selected 4 pilot sites (Baylor University, Houston, Texas; Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon; Kaiser Permanente Northern, San Jose, California; University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri) to test the feasibility of the practice pathway and provide information regarding needed modifications. The pilot sites collected data to document adherence to the practice pathway and participated in monthly conference calls to provide updates, understand variance, and recommend changes. Working with the NICHQ, members of the ATN Sleep Committee refined and finalized the practice pathway on the basis of feedback from the pilot sites. In response to recommendations from the pilot sites to increase feasibility, the NICHQ also developed a 1-page checklist designed to guide providers through the practice pathway (Fig 2).

FIGURE 2.

Practice pathway for insomnia in children who have ASD.

RESULTS

Results of the Literature Review

The search identified 1528 articles. After removing review articles, commentaries, case studies with fewer than 10 subjects, studies that included children who did not have ASD, nonintervention trials, and articles that did not address our target questions, 20 articles remained (Table 1). We reviewed the literature for studies related to other aspects of the practice pathway (eg, screening for insomnia, identifying comorbidities, importance of follow-up) in the ASD population and were unable to identify evidence-based reports for aspects other than treatment. A comprehensive review 25 and consensus statement 26 related to the pharmacologic management of insomnia in children (not specific to ASD) were identified.

TABLE 1.

Results of Systematic Literature Review

| Study and Grade | Sample | Intervention and Duration | Measures Used to Arrive at Conclusion | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacologic interventions | |||||

| Aman et al, 2005 41 | Included: 101 children aged 5 to 17 y from Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Network with ASD | 16 wk (nonresponders) to 6 mo (responders) given placebo or risperidone | Parent report sleep log | Sleep problems and anxiety less common in risperidone group (P = .02; P = .05). Average sleep duration increased short-term (17 min; 40 min) but not beyond 6 mo (29 min). Adverse events scored as moderate (placebo versus risperidone, respectively): somnolence (12% vs 37%), enuresis (29% vs 33%), excessive appetite (10% vs 33%), rhinitis (8% vs 16%), difficulty waking (8% vs 12%), and constipation (12% vs 10%) | Risperidone improves sleep latency in children with ASD but not sleep duration; high rates of adverse outcomes |

| RCT, level II | Excluded: Mental age <18 mo, positive β-human chorionic gonadotropin test result for girls, significant medical condition, previous trial with risperidone, history of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and/or weight <15 kg | 20 to 44.9 kg = 0.5 mg up to maximum of 2.5 mg/day | Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale | ||

| < 20 kg = similar, except slower dosing ≥45 kg started at 0.5 mg nightly then titrated to a maximum of 3.5 mg/day in divided doses | Adverse events scored as mild or moderate/severe (parent report) | ||||

| Honomichl et al, 2002 42 | Included: 17 children aged 3 to 8 y with autism recruited as subset of larger study (California) | 4 wk placebo and 4 wk intervention 2 CU/kg porcine secretin intravenously; no washout | CSHQ | Secretin did not significantly affect CSHQ scores: Bedtime resistance (Pre, mean: 9 [range: 6–17]; Post, mean: 8 [range: 6–13]) | Secretin does not significantly improve sleep-onset delay, duration, bedtime resistance, and night wakings in children with ASD |

| RCT, level III | Excluded: not specified | Sleep diary (bedtime, sleep onset, time/duration night waking, morning rise) | Sleep-onset delay (Pre, mean: 2.1 [range: 1–3]; Post, mean: 1.6 [range: 1–3]) | ||

| Night wakings (Pre, mean: 4.1 [range: 3–7]; Post, mean: 3.6 [range: 3–5]) | |||||

| Sleep duration (Pre, mean: 4.7 [range: 3–7]; post, mean: 4.3 [range: 3–8]) | |||||

| Ellaway et al, 2001 43 | Included: experimental group consisted of 21 females aged 7 to 41 y; recruited from previous 8-wk trial; control group included 62 females aged 4 to 30 y recruited from Australian Rett Syndrome Register | 100 mg/kg liquid l-carnitine twice a day for 6 mo | Rett syndrome Symptoms Severity Index | Compared with Rett syndrome controls, l-carnitine significantly improved sleep efficiency (P < .03) but not duration (P = .57), latency (P = .15), daytime sleep (P = .55), or night wakings (P = .25) | l-carnitine supplementation improves sleep efficiency but not duration, latency, daytime sleep, or number of night wakings in children with Rett syndrome |

| Pre/post-control, level III | Excluded: Not specified | SF-36 Health Survey | |||

| Hand apraxia scale | |||||

| 7-d sleep diary | |||||

| TriTrac-R3D Ergometer (Hemokinetics, Inc, Madison Wisconsin) | |||||

| Posey et al, 2001 44 | Included: 26 children and young adults, aged 3 to 23 y with ASD (Indiana); 20 had comorbid intellectual disability. Mirtazapine was prescribed to target symptoms of aggression, self-injury, irritability, anxiety, depression, insomnia, and interfering repetitive behavior | Mirtazapine starting dose of 7.5 mg daily with dosage increases made in 7.5-mg increments up to a maximum of 45 mg daily in divided doses, based on response of target symptoms and side effects (range: 7.5–45 mg). Treatment duration ranged from 11 to 368 d (mean duration: 150 ± 103 d) | Clinicians used the CGI scale to rate severity and improvement. A modified CGI improvement item assessing sleep quality was also included | Nine participants responded (defined according to a CGI score of much improved or very much improved). Five of 9 responders showed improved sleep. Of 17 nonresponders, 3 showed improved sleep. Statistically significant improvement was seen on the CGI severity ratings of sleep (P = .002) | Mirtazapine is effective in improving sleep quality in children with ASD |

| Pre/post-no control, level III | Excluded: Not specified | ||||

| Rossi et al, 1999 45 | Included: 25 children aged 2 to 20 y with ASD (University of Bologna) with continuous presence (≥1 y) of severe mood disorders, aggressiveness, and hyperkinesia | Niaprazine 1 mg/kg per day TID for 60 d | Behavioral Summarized Evaluation (included sleep disorders; difficulty falling asleep, night wakings, and early waking. Scored 0 to 4 (absent to very severe) | Compared with start of the treatment, Behavioral Summarized Evaluation showed improvement in sleep disorders by the end of the trial (P < .001) | Niaprazine is effective in improving sleep latency and night wakings in children with ASD |

| Pre/post-no control, level III | Excluded: children nosographically defined congenital or acquired encephalopathy | ||||

| Ming et al, 2008 46 | Included: 19 children aged 4 to 16 y with ASD (New Jersey) and sleep and behavioral disorders | Clonidine 1 time per day, initial dose 0.05 mg and gradually advanced to 0.1 mg; oral tablet. Duration for 6 mo to 2 y | Caregiver report (average bedtime, latency, number of wakings) before and during treatment | Sixteen of 17 children experienced improved sleep initiation (2–5 h before treatment, 0.5–2 h during treatment); 16 of 17 with sleep maintenance disorders experienced improvements; 5 still experienced night wakings | Clonidine improves sleep latency and wakings in children with developmental disorders |

| Retrospective case control, level III | Excluded: not specified | ||||

| Other biologic agents | |||||

| Adams and Holloway, 2004 47 | Included: 25 children aged 3 to 8 y with ASD with no changes in treatment therapies in previous 2 mo, and no previous use of multivitamin supplements other than standard children’s multivitamin (Arizona) | Days 0 to 24: 1/8 dose of SS-II (standard multivitamin), increased linearly to maximum | CGI | Sleep and gastrointestinal symptoms as evidenced by CGI score improved compared with placebo (P = .03) | Moderate-dose multivitamin (including vitamin B6 and vitamin C) may have a positive impact on CGI sleep score in children with ASD |

| RCT level II | Excluded: not specified | Days 25 to 34: held maximum dose of SS-II | Blood and urine sample (plasma B6, pyridoxine, pyridoxal, pyridoxamine, α−lipoic acid, vitamin C) | ||

| Days 35 to 50: gradual transition to SS-III | |||||

| Days 50 to 90: continued SS-III; full dose 1 ml/5 lb TID with food for a total daily intake of 3 ml/5 lb body weight | |||||

| Dosman et al, 2007 48 | Included: 33 children aged 2 to 5 y diagnosed with autism with ferritin measured previously (Toronto) | 6 mg elemental iron/kg per day for 8 wk | Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children | Per the sleep disturbance scale scores, restless sleep improved significantly (29%; P = .04) and 35% had improved sleep latency; no relation was found with ferritin (P = .61), irritability (P = .83), or Periodic Leg Movements During Sleep Scale (P = .82) | Oral iron supplementation improves restless sleep in children with ASD but does not affect irritability, sleep latency, or periodic leg movements |

| Pre/post-control, level II | Excluded: currently taking iron supplementation | If not tolerated, received 60 mg/day of microencapsulated powdered elemental iron | Periodic Leg Movements During Sleep Scale | Mean ferritin and MCV increased significantly (16 to 29 μg/L) | |

| Blood sample (MCV, mercury, albumin, vitamin B12, serum ferritin, transferrin) | |||||

| Wright et al, 2011 49 | Included: 20 children, aged 4 to 16 y with ASD and prolonged sleep latency, excessive night waking, and/or reduced total sleep time. Children had undergone behavior management that was not successful and were free of psychotropic medications | Melatonin 2 mg, 30 to 40 min before planned sleep, or placebo and then crossed over to the other agent. The dose was increased by the parent every 3 nights by 2 mg to a maximum dose of 10 mg until “good” sleep was achieved, defined as an improvement of ≥50%. Treatment phase lasted 3 mo for each agent with a 1 mo washout | Daily sleep diaries (time melatonin taken, bedtime, sleep time, night wakings, time awake) were collected every month for 9 mo | Mean sleep latency was lower (P = .004) and total sleep time was longer (P = .002) during melatonin treatment compared with placebo. Night wakings did not improve (P = .2) | Melatonin improves sleep latency and total sleep time in children with ASD but not night wakings |

| RCT, level III | Excluded: children previously or currently on melatonin, those currently on psychotropic medications, and those with other neurodevelopmental disorders such as Fragile X or Rett syndrome | Sleep difficulties questionnaire | Dyssomnia subscale improved with treatment (P = .04) but not parasomnia, sleep apnea, or other sleep disorders | ||

| Garstang and Wallis, 2006 27 | Included: 7 children aged 4 to 16 y with autism and sleeping difficulty (at least 1 h sleep latency and/or night waking 4 times per week for the last 6 mo) (United Kingdom) | Placebo or 5 mg melatonin for 4 wk, washout 1 wk, then reversed for 4 wk | Parental sleep charts (total sleep time, sleep latency, night wakings, morning awakening) | Baseline, placebo, and melatonin values respectively: Sleep latency improved 1.54 h versus baseline (2.6 h [CI: 2.28–2.93]; 1.91 h [CI: 1.78–2.03]; 1.06 h [CI: 0.98–1.13]) | Melatonin is an effective treatment to improve sleep latency number of night wakings and sleep duration |

| RCT, level II | Excluded: children previously/currently using melatonin and/or taking sedative medications for <4 wk | Wakings per night decreased by 0.27 per night versus baseline (0.35 [CI: 0.18–0.53]; 0.26 [CI: 0.20–0.34]; 0.08 [CI: 0.04–0.12]) | |||

| Duration increased by 1.79 h versus baseline (8.05 h [CI: 7.65–8.44]; 8.75 h [CI: 8.56–8.98]; 9.84 h [CI: 9.68–9.99]) | |||||

| Wirojanan et al, 2009 28 | Included: 18 children aged 2 to 15 y with autism and/or Fragile X syndrome who reported sleep problems (California) | Placebo or 3 mg melatonin given 30 min before bedtime for 2 wk, then reversed for 2 wk (no washout) | Sleep diary (sleep latency, duration, sleep onset, number of night wakings) | Compared with placebo, sleep duration improved in 9 of 12 participants by 21 min (P = .057; effect size: 2.12), sleep latency improved in 11 of 12 participants by 28 min (P = .10; effect size: 1.79), sleep onset improved by 42 min (P = .017; effect size: 2.80), and awakenings were improved by 0.07 but were insignificant (P = .73; effect size: 0.3540) | Melatonin is an effective treatment to improve sleep duration, sleep latency, and sleep onset time but not night wakings |

| RCT level II | Excluded: not specified | Actiwatch (Philips Respironics, Bend, Oregon) | |||

| Paavonen et al, 2003 50 | Included: 15 children 5 to 17 y diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome and severe sleep problems in last 3 mo (Helsinki) | Received 3 mg of melatonin 30 min before bed for 14 d | Children's Self-Report for Sleep Problems | Melatonin improved nocturnal activity (31.39 ± 7.86 to 18.74 ± 4.99; P = .041) and sleep latency (from 40.02 ± 24.09 to 21.82 ± 9.64; P = .002) but increased number of wakings (from 15.14 ± 6.12 to 17.85 ± 6.25; P = .048). No significant changes were found in sleep efficiency (85.13 ± 5.57 to 86.03 ± 4.62; P = .331) or duration (477.40 ± 55.56 to 480.48 ± 50.71; P = .572). | Melatonin is an effective treatment to improve nocturnal activity and sleep latency but not night wakings, sleep efficiency, or duration in children with Asperger’s syndrome |

| Pre/post-control, Level II | Excluded: children taking psychotropic medications or with major psychiatric comorbidity | Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children | |||

| CBCL | |||||

| Karolinska Sleepiness Scale | |||||

| Teacher’s Daytime Sleepiness Questionnaire | |||||

| Actigraphy | |||||

| Giannotti et al, 2006 51 | Included: 25 children aged 2.6 to 9.6 y with autism and CARS score <29.5 with sleep disorder (>45 min sleep latency, >3 times per week night wakings, and waking before 5 am >3 times per week) (Italy) | 6- to 24-mo (n = 25 and n = 16, respectively) study | CSHQ | CSHQ values from baseline to 6 mo were significantly improved (65 vs 43; P < .001). CSHQ values regarding latency, duration, resistance, anxiety, night wakings, and daytime sleepiness were significantly improved (P < .001). Sleep-disordered breathing also improved (P < .01). Sleep diaries showed improvements in duration by 2.6 h (P < .001), awake time after sleep onset by from 70 to 10 min (P < .001), cosleeping in 55% (P < .001), parental presence at bedtime in 63% (P < .001), and bedtime irregularity in 61% (P < .001). Those who continued 24 mo showed significant improvement in CSHQ scores in years 1 and 2 (63 vs 44 vs 44; P < .001) | Melatonin is an effective treatment to improve sleep duration, latency, number of night wakings, and bedtime resistance in children with ASD |

| Pre/post-control, level II | Excluded: children with autism diagnosis but with CARS score below cutoff, coexisting conditions, and/or taking medications for 6 mo previously | 3 mg controlled-release melatonin 30 to 40 min before bedtime (1 mg FR and 2 mg CR) | Sleep diary (bed time, rise time, duration, night wakings and duration, day naps) | ||

| Children advised to give 2 mg FR is children awoke for >15 min during the night | |||||

| Physician could increase dose to maximum of 4 mg in children aged <4 y and up to 6 mg in children aged >4 y | |||||

| Malow et al, 2011 52 | Included: 24 children aged 3 to 9 y with ASD and sleep-onset delay of ≥30 min on ≥3 nights per week | Two-week acclimation phase: inert liquid 30 min before bedtime | Actigraphy; CSHQ | With melatonin treatment (compared with acclimation phase), statistically significant improvements were seen in sleep latency (42.9 to 21.6 min; P < .0001) but not total sleep time or wake time after sleep onset | Melatonin is an effective treatment of sleep latency, and improves aspects of daytime behavior and parenting stress in children with ASD. It is safe and well tolerated |

| Pre/post-control, Level II | Excluded: children with epilepsy or taking psychotropic medications. Before melatonin treatment, medical comorbidities were addressed, and parents received sleep education training | Optional escalating dose protocol based on 3-wk periods. Dose was escalated from 1 mg to 3 mg to 6 mg based on response (if a satisfactory response occurred, defined as falling asleep within 30 min on ≥5 nights per week by actigraphy, the dose was not escalated) | CBCL, RBS, PSI. Laboratory findings (CBC, metabolic profile including liver and renal function, corticotropin, cortisol, estrogen, testosterone, FSH, LH, and prolactin). Hague Side Effects Scale | Significantly significant improvements were also noted in CSHQ subscales of sleep-onset delay and sleep duration, CBCL subscales of withdrawn, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, and affective, RBS stereotyped and compulsive, and the Difficult Child subscale on the PSI. No change in laboratory findings. Loose stools in 1 child; no other adverse effects | |

| Andersen et al, 2008 30 | Included: 107 children aged 2 to 18 y diagnosed with autism previously recommended to take melatonin sleep disorder (Tennessee) | Aged <6 y, .75-1 mg melatonin 30 to 60 min before bed. After 2 wk, if no response, increased by 1 mg every 2 wk up to 3 mg | Chart review of clinic notes (including sleep hygiene, other psychiatric conditions, severity of ASD, use of medications) | After initiation, 25% with sleep problems no longer a concern; 60% had improved sleep but still had concerns; for 13% sleep problems remained a major concern, and 1% reported worse sleep after treatment. Three children had adverse effects (morning sleepiness and/or increased enuresis) | Melatonin is a safe, effective treatment to reduce sleep problems in children with ASD |

| Pre/post-No control, level III | Excluded: children with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder | Aged ≥6 y, 1.5 mg melatonin 30 to 60 min before bed time If no response, increased dose to 3 mg after 2 wk | Sleep diary | ||

| All children: if no response after 4 wk, increase dose to 6 mg | |||||

| Behavioral/educational interventions | |||||

| Reed et al, 2009 31 | Included: 20 families of children aged 3 to 10 y with clinical diagnosis of ASD with sleep concerns (Tennessee) | • Three 2-h sessions for 3 consecutive weeks; follow-up 1 mo after end | CSHQ | Educational intervention showed improved CSHQ scores for bedtime resistance (P = .001), latency (P = .004), duration (P = .003), and sleep anxiety (P = .022) but not night wakings (P = .508), parasomnia (P = .607), sleep-disordered breathing (P = .625), and daytime sleepiness (P = .096) | Educational intervention with parents improves bedtime resistance, latency, duration, and sleep anxiety but not night wakings, early morning waking, parasomnias, sleep disordered breathing, or daytime sleepiness in children with autism |

| Pre/post-no control, level II | Excluded: children with primary sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and neurologic/medical conditions that may contribute to disordered sleep | Session 1: established daytime and night time habits and a bedtime routine based on FISH and CSHQ | Actigraphy | Actigraphy showed improved sleep latency (62.2 ± 33.33 min vs 45.6 ± 27.6; P = .039) but not waking after sleep onset (24.5± 9.8 vs 32.2 ± 24.7 min; P = 1.0) | |

| Session 2: Strategies to minimize night waking and early morning waking | Latency, duration, night wakings | 71% of parents reported fewer nights cosleeping; 33% reported improvement in early morning waking | |||

| Session 3: address individual sleep concerns | |||||

| Weiskop et al, 2005 32 | Included: 13 children (across 13 families) aged 5 y with either Fragile X syndrome (n = 7) or ASD (n = 6) with perceived sleep difficulty (Australia) | Five sessions over 7 wk with weekly telephone calls; follow-up at 3 and 12 mo | Sleep Diary (behavior, lights out, sleep onset, waking, cosleeping, morning wake time) | Baseline compared with intervention: 4.6% moderate deterioration of sleep behaviors, 25% no change, 29.7% moderate improvement, and 40.6% substantial improvements | Educational intervention with parents improved sleep latency and night wakings but not duration in children with developmental disabilities |

| Case series, level III | Excluded: excluded if diagnosed with epilepsy and/or if diagnosed with ASD, were not to be taking medication | Session 1: goal setting | Baseline compared with 3 mo: 1.6% substantial deterioration, 4.8% moderate deterioration, 27% no change, 23.8% moderate improvement, and 41.3% substantial improvement | ||

| Session 2: learning theory; antecedents and consequences. Created intervention with reinforcement and visual representation | Baseline compared with 12 mo: 7.7% moderate deterioration, 19.2% no change, 26.9% moderate improvement, and 46.2% substantial improvement | ||||

| Session 3: effective instructions and partner support strategies | Sleep latency improved in 6 of 10 (60%) | ||||

| Session 4: extinction techniques | Night waking improved for 7 of 10 (70%) | ||||

| Session 5: review session | Duration was variable and unchanged | ||||

| Cosleeping was also addressed | 100% of parents reported improved sleep but 50% still considered sleep an issue | ||||

| Complementary and alternative medicine | |||||

| Piravej et al, 2009 33 | Included: 60 children aged 3 to 10 y diagnosed with autism; 30 were put into control group (SI) and 30 were experimental (SI + TTM) (Thailand) | Two 60-min standard SI or Two 60-min TTM and SI for 8 wk | Sleep diary | Massage improved sleep scores (11.5 vs 5.3; P < .001). Standard SI improved sleep behavior (13.9 vs 8.2; P < .001). The difference between pre- and post-sleep behavior scores of the control and massage groups were not statistically significant (5.7 vs 6.3 respectively; P = .85) | TT, before bedtime improves sleep in children with ASD but not more than compared with standard SI |

| RCT, level II | Excluded: those with contraindications for TTM and those unable to complete 80% of treatment (13 massages) | Two 60-min TTM and SI for 8 wk | |||

| Williams, 2006 34 | Included: 12 children aged 12 to 15 y diagnosed with ASD from a residential school for children with autism (United Kingdom) | Three administrations of aroma therapy (2% lavender oil in grape seed oil) over 24 d via massage of foot and leg ∼2 hours before bed | Sleep diary recorded by staff on 30-min interval rounds (sleep onset, duration, wakings) | Participants did not demonstrate statistically significant sleep-onset time (F = 1.27; df = 4.15, 41.5; P = .30). Night wakings did not differ with and without aromatherapy (χ2 = 20.19; df = 16; P = .21). Sleep duration was not affected by aromatherapy (F = 0.59; df = 16, 160; P < .89) | Aroma therapy is not an effective treatment to affect sleep onset, duration, and night wakings |

| Case series level II | Excluded: none specified | ||||

| Escalona et al, 2001 35 | Included: 20 children aged 3 to 6 y recruited from school for children with autism (Florida) | For 1 mo, received 15-min massage therapy by parents (trained by therapist) or 15 min of reading before bedtime | Sleep diaries (fussing, restlessness, crying, self-stimulating behavior, and number of times child left the bed) | Greater declines for the massage therapy group with regard to fussing/restlessness, crying, self-stimulating behavior, and getting out of bed (actual numbers not provided; only provided statistics for day-time behavior) | Massage before bed decreases fussing/restlessness, crying, self-stimulating behavior, and getting out of bed in children with ASD more than reading |

| RCT, level IV | Excluded: not specified | ||||

CARS, Childhood Autism Rating Scale; CBC, complete blood cell count; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; CI, confidence interval; CR, controlled release; FISH, Family Inventory of Sleep Habits; FR, fast release; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; PSI, Parental Stress Index; RBS, Repetitive Behavior Scale; SI, Sensory Integration; SS, Spectrum Support; TTM, Thai Traditional Massage.

The results of the systematic literature review demonstrate that treatment trials are limited in the ASD population. There are 3 categories of treatment: pharmacologic/biologic treatments, behavioral/educational interventions, and complementary and alternative medicine.

The evidence base to date shows limited evidence for the use of medications to treat insomnia in children who have ASD. The most evidence exists for the use of supplemental melatonin, an indoleamine with sleep-promoting and chronobiotic (sleep phase shifting) properties considered a nutritional supplement by the US Food and Drug Administration. Several small, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated the efficacy of supplemental melatonin in treating insomnia in children who have ASD, 27 – 29 although larger studies are needed. Melatonin seems to be relatively safe based on these trials and on other series. 30 Other pharmacologic interventions such as risperidone, secretin, l-carnitine, niaprazine, mirtazapine, and clonidine, as well as multivitamins and iron, have limited evidence supporting their use in treating insomnia in ASD. The research evidence to date does not support the efficacy of other supplements or vitamins.

Behavioral interventions are clearly beneficial for typically developing children experiencing significant insomnia. 21 However, few treatment trials found that behavioral treatments provide consistent success rates in children who have ASD, particularly those experiencing sleep-onset insomnia. The systematic review of the literature identified 2 studies examining the efficacy of behavioral treatment of insomnia in children who have ASD. 31 , 32 Each of these studies demonstrated statistically significant improvements in sleep posttreatment. Both studies used multicomponent treatments, although they varied with respect to the specific components of treatment. However, they were representative of treatments commonly used in clinical practice as well as supported as effective in the general pediatric population. Both studies used extinction and positive reinforcement as treatments. Both studies provided parent training, as follows: (1) identifying a treatment goal/treatment target for therapy; (2) discussion of how the sleep problem is maintained by conditioning/learning; and (3) emphasis on establishing a developmentally appropriate bedtime and a consistent bedtime routine. Other treatment components addressed in a single study included sleep hygiene instructions, use of effective instructions/directions to shape appropriate sleep behavior, and use of the bedtime pass protocol. 23 The studies did not address relative efficacy of these individual treatment components.

Complementary and alternative medicine therapies addressed in the literature review include massage therapy and aromatherapy. 33 – 35 The systematic review found no evidence to support these therapies for insomnia in children who have ASD. Neither of the graded studies examining the efficacy of massage therapy or aromatherapy for insomnia in children who have ASD led to statistically significant improvements in sleep posttreatment. 33 – 35

Results of the Guideline Development

Based on the feasibility testing, a number of observations resulted in the development of resources to assist clinicians in the application of the practice pathway. After reviewing the literature and conducting pilot testing, the ATN Sleep Committee developed and refined the insomnia practice pathway and made the following consensus recommendations:

General pediatricians, family care providers, and autism medical specialists should screen all children who have ASD for insomnia.

This screening is best done by asking a short series of questions targeting insomnia, such as those from the CSHQ, and asking if the parent considers these a problem. These questions are: (1) child falls asleep within 20 minutes after going to bed; (2) child falls asleep in parent's or sibling's bed; (3) child sleeps too little; and (4) child awakens once during the night. These questions were selected on the basis of review of the CSHQ and expert consensus. The ATN database was also reviewed (n = 4887), and we found that 81% of parents who reported that their child awakening more than once during the night was a problem also answered affirmatively to the question “Does your child awaken once during the night?” Therefore, to limit the questions asked, we did not include “Does your child awaken more than once during the night?” Asking specific questions is essential because parents may not volunteer concerns about insomnia given their concerns with behavioral issues (although these issues may be secondary to the insomnia). Identifying significant insomnia is paramount given its impact on daytime functioning, not only for the child with ASD but also the family. Table 2 lists available questionnaires.

TABLE 2.

Sleep Questionnaire Options

| Questionnaire | Description | Format | Respondent |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSHQ (Owens et al, 2000) 36 | Assesses sleep behaviors across a range of behavioral and medical dimensions in children aged 4 to 10 y | Forty-five items that roll into 8 subscales: bedtime resistance, sleep onset delay, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, night wakings, parasomnias, sleep-disordered breathing, and daytime sleepiness | Parent |

| Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire in Toddlers and Preschool Children (Goodlin-Jones et al, 2008) 23 | Assesses the CSHQ (see above) in children aged 2 to 5.5 y with autism, developmental delay without autism, and typically developing children | Same as the CSHQ (above) | Parent |

| Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children 37 | Characterizes sleep disorders over the past 6 mo in children aged 5 to 15 y | Twenty-six items that role into 6 subscales: sleep initiation and maintenance, daytime sleepiness, sleep arousal, and sleep-disordered breathing | Parent |

| Family Inventory of Sleep Habits 38 | Autism specific questionnaire assessing sleep hygiene in children aged 3 to 10 y | Twelve items, including daytime and prebedtime habits, bedtime routine, and sleep environment | Parent |

| Behavioral Evaluation of Disorders of Sleep Scale 39 | Assesses sleep behaviors in children aged 5 to 12 y | Five types of sleep problems: expressive sleep disturbances; sensitivity to the environment; disoriented awakening; sleep facilitators; and apnea/bruxism | Parent |

| BEARS 17 | Assesses 5 sleep domains in children aged 5 to 18 y | Five sleep domains: bedtime problems (difficulty going to bed and falling asleep); excessive daytime sleepiness (includes behaviors typically associated with daytime somnolence in children); awakenings during the night; regularity of sleep/wake cycles (bedtime, wake time) and average sleep duration; and snoring | Parent |

| Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale 40 | Assesses sleep quality in adolescents aged 11 to 21 y | Twenty-eight items role into 5 subscales: going to bed, falling asleep, awakening, reinitiating sleep, and wakefulness | Adolescent |

BEARS, B = Bedtime problems, E = Excessive Daytime Sleepiness, A = Awakenings During the Night, R = Regularity and Duration of Sleep, S = Snoring.

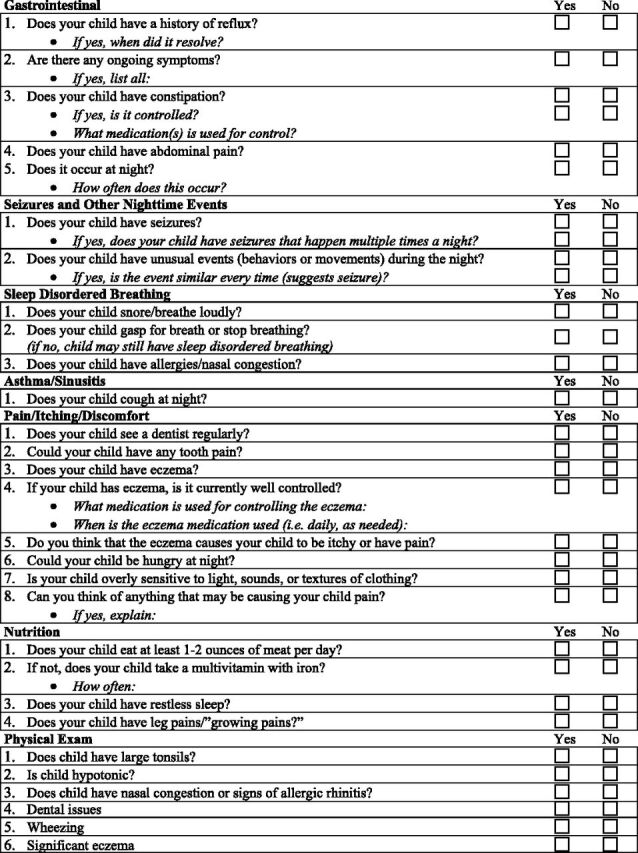

The evaluation of insomnia should include attention to medical contributors that can affect sleep (including neurologic conditions and other sleep disorders that contribute to insomnia).

These contributors should be addressed because their treatment may improve insomnia. Within the ATN, we have developed a list of questions for medical contributors, including gastrointestinal disorders, epilepsy, pain, nutritional issues, and other underlying sleep disorders responsible for insomnia, including sleep-disodered breathing and restless legs symptoms (Table 3) that pediatricians can incorporate within their review of systems. Psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder, should be considered because these may contribute to insomnia. Finally, because many medications contribute to insomnia, a careful review of medications should be performed.

TABLE 3.

Questionnaire to Help Identify Underlying Medical Conditions

Educational/behavioral interventions are the first line of treatment, after excluding medical contributors. However, if an educational (behavioral) approach does not seem feasible, or the intensity of symptoms has reached a crisis point, the use of pharmacologic treatment is considered.

Educational/behavioral approaches to the treatment of insomnia are advocated as a first-line treatment in typically developing children. 21 In children who have ASD, educational/behavioral approaches are also recommended, especially because these children may not be capable of expressing adverse effects caused by the medications. The core behavioral deficits associated with ASD may impede the establishment of sound bedtime behaviors and routines. These include: (1) difficulty with emotional regulation (eg, ability to calm self); (2) difficulty transitioning from preferred or stimulating activities to sleep; and (3) deficits in communication skills affecting a child’s understanding of the expectations of parents related to going to bed and falling asleep. Conversely, given preferences for sameness and routine, children who have ASD may adapt well to establishment of bedtime routines, especially if visual schedules are implemented.

The ATN has developed an educational toolkit for parents that consists of pamphlets to promote good sleep habits; a survey to assess for habits that may interfere with sleep; sample bedtime routines, including a visual supports library, tip sheets for implementing the bedtime routine, and managing night wakings; and a sleep diary. The toolkit is being tested for feasibility in an ongoing research project funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration of parent sleep education at 4 ATN sites and is also being used in clinical practice throughout the network. As with other educational/behavioral approaches, the success of this toolkit depends on appropriate implementation by parents, with the guidance provided by practitioners an essential element for many families. Families can often be encouraged to implement educational/behavioral strategies when presented with these tools, especially if they receive hands-on instruction in the tools and are provided with an explanation of why a behavioral approach is recommended. However, some families may be in a state of crisis or may not be willing or able to use the behavioral tools. These families may be challenged by difficult daytime behaviors in their child or by financial concerns. These children might require pharmacologic treatment. In addition, practitioners may not be able to provide sufficient instruction in the tools for a family to be successful with their implementation. Therefore, there is the option in the practice pathway (Fig 2, Box 5b) of medication or consultation to a sleep specialist if the family is unwilling or unable to use an educational approach, depending on the comfort level of the pediatrician.

Behavioral Treatments for Insomnia

The behavioral treatments most commonly used to treat insomnia in children who have ASD include behavioral modification strategies such as extinction (eg, withdrawal of reinforcement for inappropriate bedtime behaviors) and positive reinforcement of adaptive sleep behavior. Sleep hygiene instructions (eg, appropriate sleep schedules and routines) often accompany behavioral modification protocols. Behavioral interventions are effective in the treatment of insomnia in typically developing children. 21 However, the evidence base for effectiveness of such interventions in children who have ASD is limited. The data from the literature review provide preliminary support for the use of behavioral modification to treat insomnia in children who have ASD. These data were the basis for the development of an educational toolkit used to guide behavioral management of insomnia in the insomnia practice pathway.

Alternative Treatments for Insomnia

The most common alternative therapy with a presence in the literature is massage therapy. 33 , 35 However, the results do not demonstrate consistent, statistically significant improvements in sleep.

Pharmacologic Treatments for Insomnia

Although medications and supplements are often used to treat insomnia experienced by children and adolescents who have ASD, the evidence base for pharmacologic treatment is limited. At this time, there are no medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for pediatric insomnia. The most evidence exists for the use of melatonin.

Clinicians should assure timely follow-up to monitor progress and resolution of insomnia.

Assuring adequate follow-up is crucial when treating children who have ASD and significant insomnia. Follow-up should occur within 2 weeks to 1 month after beginning treatment. The provider and family should expect to see some benefits and improvements within 4 weeks. Follow-up may be conducted by telephone or in person. Timely follow-up allows for fine-tuning of treatment interventions, support of parents, and provision of referrals if needed. In addition to short-term follow-up (eg, 1–2 months), at long-term follow-up (eg, 1-year visit) the steps from the beginning of the practice pathway should be repeated.

As outlined in the practice pathway, treatment of insomnia can be initiated by the general pediatrician, primary care provider, or autism medical specialist. Many children will improve with these initial interventions. Consultation with a sleep specialist is indicated if insomnia is not improving with these initial interventions or when the insomnia is particularly severe, causing significant daytime impairment or placing the child at risk for harm while awake during the night. For those children who have ASD and are taking multiple medications for sleep when initially assessed by the health care provider, consultation with a sleep specialist may be indicated, depending on the comfort level of the provider. Other indications for consultation with a pediatric sleep specialist may include when underlying sleep disorders are responsible for the sleeplessness symptoms (including sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and unusual nighttime behaviors [parasomnias] such as sleepwalking or sleep terrors).

Results of the Field Testing

Results of the pilot phase indicated challenges in implementing the practice pathway due to a number of conflicts, including: (1) competing demands on the pediatric provider in a busy clinical practice; (2) knowledge level of the pediatric provider; and (3) when consultation to the sleep specialist occurs, ensuring communication back to the pediatric provider.

In response to these barriers, we developed the following resources: (1) a short set of screening questions for insomnia as well as a checklist for medical conditions contributing to insomnia (Table 3); and (2) a sleep education toolkit, available in hard copy as well as on the internal ATN Web site (www.autismspeaks.org/atn) that will facilitate parent teaching.

Additional issues were identified related to provider comfort level in the following areas: (1) assessing for medical or sleep contributors themselves rather than referring to a specialist, which led us to modify the practice pathway to allow for both options; (2) providing education to families in use of the toolkit, which affected the length at which follow-up occurred (eg, a second visit with a nurse educator might be needed for toolkit implementation if the provider was too busy to educate families at the time of the initial clinic visit); and (3) treating insomnia with medications on their own versus referring to a sleep specialist. When a child was referred to the sleep specialist, ensuring that the sleep specialist communicated back to the provider regarding recommendations was also an issue related to applying the practice pathway in our field testing, particularly as related to follow-up care.

We modified the flow of the practice pathway in response to feedback during the field testing. Initially, the practice pathway prioritized evaluation and treatment of medical contributors before implementing educational measures, such as the toolkit. However, based on the feedback of clinicians, the evaluation/treatment of medical contributors and the implementation of educational measures became a parallel process as opposed to a sequential “first–then” approach.

DISCUSSION

We report here on the development of a practice pathway for the evaluation and management of insomnia in children who have ASD. There are several key points of this practice pathway. First, general pediatricians, primary care providers, and autism medical specialists should screen all children who have ASD for insomnia because parents may not volunteer sleep concerns despite these concerns being contributors to medical comorbidities and behavioral issues. Second, the evaluation of insomnia should include attention to medical contributors that can affect sleep, including other medical problems that encompass gastrointestinal disorders, epilepsy, psychiatric comorbidities, medications, and sleep disorders including sleep-disordered breathing, restless legs syndrome (unpleasant sensations in the legs associated with an urge to move), periodic limb movements of sleep (rhythmic leg kicks during sleep), and parasomnias (undesirable movements or behaviors during sleep, such as sleepwalking, sleep terrors, or confusional arousals). In parallel with this screening, the need for therapeutic intervention should be determined. We also determined that educational/behavioral interventions are the first line of treatment, after excluding medical contributors. If an educational (behavioral) approach does not seem feasible, or the intensity of symptoms has reached a crisis point, the use of pharmacologic treatment is considered. Finally, clinicians should assure timely follow-up to monitor progress and resolution of insomnia.

This practice pathway expands the literature that currently exists for typically developing children related to screening and management. 5 , 7 – 9 The rationale for developing a practice pathway that uniquely addresses this population is because children who have ASD, and their families, have unique needs. For example, medical, neurologic, and psychiatric comorbidities are common in children who have ASD, as is the use of medications that influence sleep. In addition, parents of children who have ASD, struggling with the stressors related to their child’s disability and the often accompanying behavioral challenges, may not volunteer sleep to be of concern. In turn, pediatric providers may not ask about sleep due to competing medical and behavioral issues. Furthermore, sleep problems are more common in children who have ASD than in children of typical development, 2 , 3 and their treatment may impact favorably on daytime behavior and family functioning. Given these factors, we do recognize that children who have other disorders of neurodevelopment could also benefit from this practice pathway, as they share common features with children who have ASD, including comorbid conditions, parental stressors, and prevalent sleep problems.

The systematic review of the available treatment literature allowed for the recognition that evidence-based standards for the behavioral, pharmacologic, and other treatments of insomnia in ASD are not yet available. Thus, much of these guidelines reflect expert opinion given the absence of data. Additional studies are needed to establish the efficacy and safety of supplemental melatonin, as well as other pharmacologic agents, in large RCTs. Similar studies are needed to address the efficacy of parent-based sleep educational programs to address insomnia, as well as the combination of these educational programs with pharmacologic strategies. Finally, the role of nonpharmacologic methods (apart from educational therapies) warrants study as well. As additional research studies are performed, the clinical pathway will likely require modification. However, it is expected that the overarching approach to insomnia in the child who has ASD will not change. Although the practice pathway was piloted at 4 ATN sites, the next steps involve the wide dissemination of the practice pathway into pediatric practices. We would also like to develop a practice pathway for nonmedical health professionals who are likely to provide behavioral interventions, including psychologists.

Strengths of the study include the gathering of the following groups: experts in sleep medicine from a variety of disciplines, including neurology, psychiatry, pulmonary medicine, and psychology; engaged pediatricians specializing in ASD; and parents of children who have ASD. Weaknesses include limited evidence-based studies on which to base the practice pathway, making it necessary to rely on expert opinion.

CONCLUSIONS

The practice pathway regarding the identification of insomnia in children who have ASD requires future field testing in clinical settings but represents a starting point to managing insomnia in a growing population of children with the most common neurodevelopmental disability.

Acknowledgment

The valuable assistance of the members of the ATN Sleep Committee in reviewing this document is gratefully acknowledged.

Glossary

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- ATN

Autism Treatment Network

- CSHQ

Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire

- NICHQ

National Initiative for Children’s Healthcare Quality

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

This manuscript has been read and approved by all authors. This paper is unique and not under consideration by any other publication and has not been published elsewhere.

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Couturier JL , Speechley KN , Steele M , Norman R , Stringer B , Nicolson R . Parental perception of sleep problems in children of normal intelligence with pervasive developmental disorders: prevalence, severity, and pattern. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):815–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krakowiak P , Goodlin-Jones B , Hertz-Picciotto I , Croen LA , Hansen RL . Sleep problems in children with autism spectrum disorders, developmental delays, and typical development: a population-based study. J Sleep Res. 2008;17(2):197–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Diagnostic and Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Armstrong KL , Quinn RA , Dadds MR . The sleep patterns of normal children. Med J Aust. 1994;161(3):202–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson KP , Malow BA . Assessment and pharmacologic treatment of sleep disturbance in autism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(4):773–785, viii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kataria S , Swanson MS , Trevathan GE . Persistence of sleep disturbances in preschool children. J Pediatr. 1987;110(4):642–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pollock JI . Night-waking at five years of age: predictors and prognosis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994;35(4):699–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zuckerman B , Stevenson J , Bailey V . Sleep problems in early childhood: continuities, predictive factors, and behavioral correlates. Pediatrics. 1987;80(5):664–671 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wiggs L , Stores G . Severe sleep disturbance and daytime challenging behaviour in children with severe learning disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1996;40(pt 6):518–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiggs L , Stores G . Behavioural treatment for sleep problems in children with severe learning disabilities and challenging daytime behaviour: effect on daytime behaviour. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):627–635 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meltzer LJ , Johnson C , Crosette J , Ramos M , Mindell JA . Prevalence of diagnosed sleep disorders in pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/125/6/e1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Meissner HH , Riemer A , Santiago SM , Stein M , Goldman MD , Williams AJ . Failure of physician documentation of sleep complaints in hospitalized patients. West J Med. 1998;169(3):146–149 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Owens JA . The practice of pediatric sleep medicine: results of a community survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/108/3/E51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blunden S , Lushington K , Lorenzen B , Ooi T , Fung F , Kennedy D . Are sleep problems under-recognised in general practice? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(8):708–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schreck KA , Richdale AL . Knowledge of childhood sleep: a possible variable in under or misdiagnosis of childhood sleep problems. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(4):589–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Owens JA , Dalzell V . Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2005;6(1):63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mindell JA , Kuhn B , Lewin DS , Meltzer LJ , Sadeh A American Academy of Sleep Medicine . Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1263–1276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mindell JA . Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: bedtime refusal and night wakings in young children. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24(6):465–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuhn BR , Elliott AJ . Treatment efficacy in behavioral pediatric sleep medicine. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(6):587–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morgenthaler TI , Owens J , Alessi C , et al. American Academy of Sleep Medicine . Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29(10):1277–1281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reynolds AM , Malow BA . Sleep and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(3):685–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goodlin-Jones BL , Sitnick SL , Tang K , Liu J , Anders TF . The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire in toddlers and preschool children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(2):82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guyatt GH , Oxman AD , Vist GE , et al. GRADE Working Group . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Owens JA , Moturi S . Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric insomnia. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(4):1001–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mindell JA , Emslie G , Blumer J , et al. Pharmacologic management of insomnia in children and adolescents: consensus statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/6/e1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garstang J , Wallis M . Randomized controlled trial of melatonin for children with autistic spectrum disorders and sleep problems. Child Care Health Dev. 2006;32(5):585–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wirojanan J , Jacquemont S , Diaz R , et al. The efficacy of melatonin for sleep problems in children with autism, fragile X syndrome, or autism and fragile X syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(2):145–150 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wasdell MB , Jan JE , Bomben MM , et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of controlled release melatonin treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome and impaired sleep maintenance in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. J Pineal Res. 2008;44(1):57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andersen IM , Kaczmarska J , McGrew SG , Malow BA . Melatonin for insomnia in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Neurol. 2008;23(5):482–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reed HE , McGrew SG , Artibee K , et al. Parent-based sleep education workshops in autism. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(8):936–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weiskop S , Richdale A , Matthews J . Behavioural treatment to reduce sleep problems in children with autism or fragile X syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47(2):94–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piravej K , Tangtrongchitr P , Chandarasiri P , Paothong L , Sukprasong S . Effects of Thai traditional massage on autistic children’s behavior. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(12):1355–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Williams TI . Evaluating effects of aromatherapy massage on sleep in children with autism: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3(3):373–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Escalona A , Field T , Singer-Strunck R , Cullen C , Hartshorn K . Brief report: improvements in the behavior of children with autism following massage therapy. J Autism Dev Disord. 2001;31(5):513–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Owens JA , Spirito A , McGuinn M . The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep. 2000;23(8):1043–1051 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bruni O , Ottaviano S , Guidetti V , et al. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res. 1996;5(4):251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Malow BA , Crowe C , Henderson L , et al. A sleep habits questionnaire for children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Neurol. 2009;24(1):19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schreck KA , Mulick JA , Rojahn J . Development of the behavioral evaluation of disorders of sleep scale. J Child Fam Stud. 2003;12(3):349–359 10.1023/A:1023995912428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. LeBourgeois MK , Giannotti F , Cortesi F , Wolfson AR , Harsh J . The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(suppl 1):257–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aman MG , Arnold LE , McDougle CJ , et al. Acute and long-term safety and tolerability of risperidone in children with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(6):869–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Honomichl RD , Goodlin-Jones BL , Burnham MM , Hansen RL , Anders TF . Secretin and sleep in children with autism. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(2):107–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ellaway CJ , Peat J , Williams K , Leonard H , Christodoulou J . Medium-term open label trial of L-carnitine in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 2001;23(suppl 1):S85–S89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Posey DJ , Guenin KD , Kohn AE , Swiezy NB , McDougle CJ . A naturalistic open-label study of mirtazapine in autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2001;11(3):267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rossi PG , Posar A , Parmeggiani A , Pipitone E , D’Agata M . Niaprazine in the treatment of autistic disorder. J Child Neurol. 1999;14(8):547–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ming X , Gordon E , Kang N , Wagner GC . Use of clonidine in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev. 2008;30(7):454–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Adams JB , Holloway C . Pilot study of a moderate dose multivitamin/mineral supplement for children with autistic spectrum disorder. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(6):1033–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dosman CF , Brian JA , Drmic IE , et al. Children with autism: effect of iron supplementation on sleep and ferritin. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36(3):152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wright B , Sims D , Smart S , et al. Melatonin versus placebo in children with autism spectrum conditions and severe sleep problems not amenable to behaviour management strategies: a randomised controlled crossover trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(2):175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Paavonen EJ , Nieminen-von Wendt T , Vanhala R , Aronen ET , von Wendt L . Effectiveness of melatonin in the treatment of sleep disturbances in children with Asperger disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(1):83–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Giannotti F , Cortesi F , Cerquiglini A , Bernabei P . An open-label study of controlled-release melatonin in treatment of sleep disorders in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36(6):741–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Malow B , Adkins KW , McGrew SG , et al. Melatonin for sleep in children with autism: a controlled trial examining dose, tolerability, and outcomes [published correction appears in J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(8):1738]. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(8):1729–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]