Abstract

Rationale: The gut microbiota plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, the role of Blastocystis infection and Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota in the development of inflammatory diseases and their underlying mechanisms are not well understood.

Methods: We investigated the effect of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection on the intestinal microbiota, metabolism, and host immune responses, and then explored the role of Blastocystis-altered gut microbiome in the development of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice.

Results: This study showed that prior colonization with ST4 conferred protection from DSS-induced colitis through elevating the abundance of beneficial bacteria, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production and the proportion of Foxp3+ and IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells. Conversely, prior ST7 infection exacerbated the severity of colitis by increasing the proportion of pathogenic bacteria and inducing pro-inflammatory IL-17A and TNF-α-producing CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, transplantation of ST4- and ST7-altered microbiota resulted in similar phenotypes.

Conclusions: Our data showed that ST4 and ST7 infection exert strikingly differential effects on the gut microbiota, and these could influence the susceptibility to colitis. ST4 colonization prevented DSS-induced colitis in mice and may be considered as a novel therapeutic strategy against immunological diseases in the future, while ST7 infection is a potential risk factor for the development of experimentally induced colitis that warrants attention.

Keywords: Blastocystis, Gut microbiota, IBD, DSS-induced colitis, Short-chain fatty acids

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorder, including Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) 1. Numerous factors are thought to play important roles in the pathogenesis of IBD, including the gut microbiome and immune dysregulation 2, 3. The gut microbiome is composed of trillions of indigenous bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, and protists 4. Studies have primarily focused on associations between bacteria and IBD, while the influence of gut protists on this disease is largely unexplored 5. Several protists are typically known for causing dysenteric infections, such as Entamoeba histolytica, and Cryptosporidium spp. 6, 7. However, the impact of other protists on host health remains debated, particularly for Blastocystis. Blastocystis is the most common gut protist found in humans and animals, and harbors extensive genetic heterogeneity 8. The relationship between Blastocystis and IBD is controversial. Several studies have shown that Blastocystis prevalence was higher in IBD patients than in healthy individuals 9, 10, while Blastocystis was also considered to be an enteric commensal as it was found to be more abundant in asymptomatic individuals and associated with increased gut bacterial diversity 11.

Blastocystis colonization or infection could modulate the gut microbial composition and may influence the progression of IBD 12. Experimental colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in rodents is a common animal model of human IBD research 13. Our previous study showed that infection with Blastocystis ST7 exacerbated the severity of DSS-induced colitis in a mouse model. This was accompanied with decreased proportions of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus 14. However, our recent study showed that colonization with Blastocystis ST4 can reduce the severity of colitis through modulating the gut microbiota and activation of T helper-2 (Th2) and regulatory T cell (Treg) immune responses 15. These earlier studies involved inoculation of Blastocystis after DSS treatment and investigated the effects of Blastocystis infection or colonization in promoting recovery or exacerbating DSS-induced colitis. However, whether prior Blastocystis infection has an impact on subsequent experimentally induced colitis and whether Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota is also able to influence the development of IBD remains unexplored.

Although several studies have shown the associations between Blastocystis colonization and host health, most studies do not demonstrate whether the effect of Blastocystis on host health is a direct result of immune regulation or an indirect effect of microbiome modulation. On another hand, studies looking at the effect of Blastocystis on the gut microbiota employed the use of one subtype, although it has been reported that distinct subtypes interact differently with bacteria. In this study, we compared the effects of colonization by two Blastocystis subtypes, ST4 and ST7, available as axenic cultures (pure cultures grown in the absence of bacteria) that have shown distinct effects on gut epithelial barrier function and immune responses in several in vitro studies 16, 17. ST4 and ST7 were originally identified in a Wistar rat and a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms, respectively 18, 19. We observed that prior ST4 colonization can prevent induced colitis when mice were later challenged with DSS, through elevating the proportion of beneficial bacteria, SCFAs, and protective immune responses. In contrast, prior infection with ST7 exacerbated colitis through inducing pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 immune responses. These results provide evidence that distinct modifications of gut microbial composition are triggered by specific Blastocystis subtypes, and that Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota play roles in the development of experimental colitis.

Materials and methods

Blastocystis cultures

Axenized cultures of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 were used in this study. ST4-WR1 was first identified in a healthy Wistar rat in National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore 19. ST7-B was originally isolated from a diarrheal patient at the Singapore General Hospital in the early 1990s before the Institutional Review Board was established at the NUS 18. Blastocystis was maintained in 10 ml of pre-reduced Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) (Gibco) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% horse serum (Gibco), and NaHCO3. Blastocystis cells were cultured in an Anaerojar (Oxoid) with Oxoid CO2 Gen Sachet (Thermo Scientific) at 37 °C. A hemocytometer (Kova International) was used to calculate the number of Blastocystis cells.

Mice and treatment

C57BL/6 mice, aged 8-12 weeks and bred in-house, were maintained in the animal facility of the National University of Singapore (NUS). Littermates of the same sex and age were randomly assigned to the different experimental groups. All animal experiments were performed under the Singapore National Advisory Committee for Laboratory Animal Research guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of NUS (protocol no. R19-1259).

Oral infection of Blastocystis. Mice (n = 6 per group) were orally gavaged with 5 × 107 live Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 cells suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The control mice (n = 6) were orally gavaged with equal amounts of PBS at the same time. The mice used in all the experiments were age and sex matched. Each treatment was housed together in two cages (n = 3).

DSS-induced colitis. Mice were exposed to 2% DSS (molecular mass = 36,000-50,000 Da; MP Biomedicals) w/v in drinking water for 7 days. The weight, stool consistency, and presence of fecal blood were recorded each day. The disease activity index (DAI) was used to determine the severity of colitis as previously described 20.

Antibiotic administration. Mice were administrated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail ampicillin (1 g/L), vancomycin (500 mg/L), neomycin sulfate (1 g/L), and metronidazole (1 g/L) in drinking water for 14 days 21, before the microbiota transplant experiments.

Microbiota transfer

To exclude the effect of Blastocystis on the severity of colitis, feces collected from ST4 and ST7 infected mice and non-infected control mice were frozen at -80°C, and then thawed in pre-reduced PBS. This procedure ruptures Blastocystis cells, and the absence of live Blastocystis cells was confirmed by culturing the feces in Jones' medium. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was performed as described 22. In brief, frozen feces were pooled from control, ST4-colonized, and ST7-infected mice, respectively, diluted with pre-reduced PBS (50 mg/ml), and administered to recipient mice by oral gavage (10 mg/mice) three times a week for one week.

Scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed as previously described 23. In brief, the cecum/colon tissues were collected and then processed by opening the gut longitudinally without disturbing the intestinal contents. The opened tissues were pinned down to a silicone mat in four corners and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C overnight, and then washed twice with PBS. The washed tissues were kept at 4°C until further processing. The tissues were processed by post-fixing in 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h, and then dehydrated first in 25% ethanol for 5 minutes followed by 50%,75% and 95% ethanol for 10 minutes each. After which, the sample was fixed in 100% ethanol for 10 minutes (3 changes). The dried samples were coated with 25 nm of gold and imaged on a field emission JSM-6701F SEM at a voltage of 10 kV.

DNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Total genomic DNA from feces of control, ST4-colonized, and ST7-infected mice at day 0 (before Blastocystis inoculation), and day 14 (end of experiment) was extracted using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was used to estimate the number of Blastocystis cells in fecal samples at the end point as described 24.

Colon histology

Colonic tissues were collected at the end of each experiment and fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin, and then processed and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4.5 μm were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histology scoring was performed in a blinded fashion, whereby changes in intestinal crypt architecture, degree of inflammation, and epithelium damage were scored as previously described 25. A combined score of crypt architecture, tissue damage, goblet cell loss, and inflammatory cell infiltration was determined as follows: crypt architecture: score 0, normal; 1, irregular; 2, moderate crypt loss (10-50%); 3, severe crypt loss (50-90%); 4, small/medium sized ulcers (<10 crypt widths); 5, large ulcers (>10 crypt widths). Tissue damage: score 0, no damage; 1, discrete lesions; 2, mucosal erosions; 3, extensive mucosal damage. Goblet cell loss: score 0, normal; 1, 10-25% loss; 2, 25-50% loss; 3, = >50% loss. Inflammatory cell infiltration: score 0, occasional infiltration; 1, increasing leukocytes in lamina propria; 2, confluence of leukocytes extending to submucosa; 3, transmural extension of inflammatory infiltrates.

16S rRNA gene sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from fecal samples. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing library was constructed using a MetaVX Library Preparation Kit (South Plainfield, NJ). Briefly, 20-30 ng of DNA was used to generate amplicons that cover V3 and V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria. The forward primer contains the sequence 'CCTACGGRRBGCASCAGKVRVGAAT', and the reverse primers contain the sequence 'GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAATCC'. The 25 µl PCR mixture was prepared with 2.5 µl of TransStart buffer, 2 µl of dNTPs, 1 µl of each primer, 0.5 µl of TransStart Taq DNA polymerase, and 20 ng template DNA. PCR was performed by the following program: 3 min of denaturation at 94℃, 24 cycles of 5 s at 95℃, 90 s of annealing at 57℃, 10 s of elongation at 72℃, and a final extension at 72℃ for 5 min. Indexed adapters were added to the ends of the amplicons by limited cycle PCR. Finally, the library was purified using magnetic beads. DNA concentration was determined with a microplate reader (Tecan, Infinite 200 Pro) and the expected ~600 bp fragment size was determined by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Next generation sequencing was conducted on an Illumina Novaseq Platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA) at Azenta Inc (USA). Automated cluster generation and 250 paired-end sequencing with dual reads were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Paired-end sequences of positive and negative reads were filtered, denoised, and had chimeras removed to obtain amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) through DADA2 using Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2 (Qiime2) plugin 26. The ribosomal database program (RDP) Classifier Bayes algorithm was trained using Silva 138 database to perform a taxonomic analysis 27. Shannon and Chao1 were used to estimate the bacterial diversity and richness respectively. Beta diversity was assessed by permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plots were constructed based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity to illustrate the differences in community structure between different groups. Heatmaps were used to show the different taxa between groups. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis was performed to detect bacterial taxa with significantly different abundance among different groups with P-value <0.05 and LDA score >4 (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/).

RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

Colon tissues were collected and washed with PBS to discard the luminal contents, and then dissected into 1 cm pieces for RNA extraction. RNA was extracted using RNAzol RT (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol. One μg total RNA was used for the library preparation. Poly(A) mRNA isolation was performed using Oligo (dT) beads. The mRNA fragmentation was performed using divalent cations and high temperatures. Priming was performed using Random Primers (Invitrogen). First-strand cDNA and the second-strand cDNA were synthesized. The purified double-stranded cDNA was then treated to repair both ends and a dA-tailing in one reaction, followed by a T-A ligation to add adaptors to both ends was performed. Size selection of Adaptor-ligated DNA was then performed using MagMAX™ DNA Multi-Sample Ultra Kit (Applied Biosystems). Each sample was then amplified by PCR using P5 ('AATGATACGGCGACCACCGA') and P7 ('CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT') primers and the PCR products were validated using Agilent 2100. Then libraries with different indexes were multiplexed and loaded on an Illumina Novaseq6000 instrument at Azenta Inc (USA).

To remove adapters, primers, or fragments thereof, and quality of bases lower than 20, pass filter data of fastq format were processed by Cutadapt (V4.1, phred cutoff: 20, error rate: 0.1, adapter overlap: 1bp, min. length: 75, proportion of N: 0.1) to give high-quality clean data. Reference genome sequences and gene model annotation files were downloaded from ENSEMBL (https://asia.ensembl.org/index.html). Hisat2 (v2.1.0) was used to index reference genome sequences 28. Principal component analysis (PCA) was generated by corrplot package in R language. Differential expression analysis was done using the Limma Bioconductor package 29. Padj of genes was set at < 0.05 to detect differential expressed genes (DEGs). GOSeq (v1.34.1) was used to identify GO terms that annotate a list of enriched genes with a significant padj less than 0.05. KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) is a collection of databases dealing with genomes, biological pathways, diseases, drugs, and chemical substances (http://en. wikipedia.org/wiki/KEGG). We used in-house scripts to enrich significant differential expression genes in KEGG pathways. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was generated in GSEABase package in R 30, 31.

LC/MS/MS assay

Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) was carried out for analysis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in derivatized stool extracts as previously described 32. Briefly, 500 μl of ice-cold extraction solvent containing 10 μM of d5-benzoic acid as internal standard (IS) was added to 250 mg of fecal sample and subjected to vortex mixing for 5 min at ambient temperature. The suspension was then centrifuged at 18,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was carefully removed and centrifuged again at 18,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. An aliquot of 100 μl was subsequently derivatized using a final concentration of 10 mM aniline and 5 mM EDC for 2 h at 4 °C. The derivatization reaction was quenched using a final concentration of 18 mM succinic acid and 4.6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol for 2 h at 4 °C. All samples were stored at 4 °C until analysis on the same day. Analysis was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC system (Agilent Technologies) interfaced with an AB Sciex QTRAP 5500 hybrid linear ion-trap quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a TurboIonSpray source (Applied Biosystems).

Isolation of colon lamina propria cells

To analyze colonic lymphocytes, the colon tissues were longitudinally opened and washed with ice-cold PBS to remove luminal contents. The tissues were cut into 1 cm pieces and incubated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1 mM EDTA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mM DTT (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 20 min under slow rotation and spun down to remove the supernatant. The remaining tissue pieces were incubated in RPMI containing 25% HEPES, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT at 37 ℃ for 1 h under slow rotation and then washed by PBS to remove epithelial cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes. Tissue pieces were digested with Liberase (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 ℃ for 30 min under slow rotation. The digested tissue pieces and supernatants were filtered by 70 μm cell strainer and glass wool separately. After centrifugation, pellets containing the LP lymphocytes were harvested.

Flow cytometry analysis

Lymphocytes were stimulated for 6 h with a cell stimulation cocktail of PMA (50 ng/ml), ionomycin (750 ng/ml), and GolgiStop (monensin, BD Biosciences). Live/dead stain was used to evaluate the viability of the cells using live/dead fixable viability stain kits. For surface staining, stimulated cells were stained with TCR beta monoclonal antibody (BUV510, eBioscience), and anti-CD4 (BUV395; Biolegend). Fixation and permeabilization buffers from Biolegend were used for intracellular cytokine staining. Fixed and permeabilized cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies against interleukin (IL)-4 (BUV421; Biolegend), IL-10 (PE; Biolegend), IL-17A (APC; eBioscience), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) (BUV711; Biolegend), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) (APC; eBioscience) at 4 ℃ for 10 h. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on Fortessa X-20 (BD biosciences) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo_V10 software.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 (Graphpad Software Inc.). Two independent experiments were performed. For comparisons of two groups, Student's two-tailed t-test was used. When three or more groups were analyzed, one-way or two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons test was used. Error bars on graphs display the mean and SEM. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant; the following symbols were used to indicate significance levels: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; and ****, P < 0.0001.

Results

Effects of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection on bacterial compositions

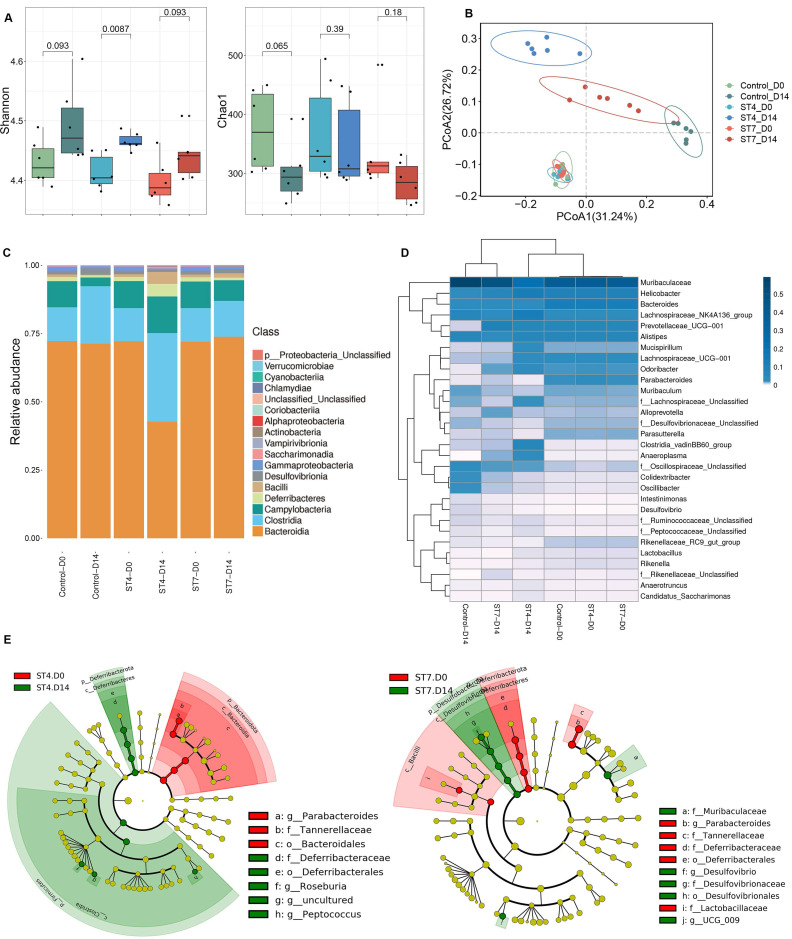

C57BL/6 mice were orally gavaged with Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 three times a week for two weeks (Figure S1A). The number of Blastocystis cells and colonization status was confirmed by qPCR and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure S1B-C). Although the bacterial richness reflected by Chao1 did not show significant differences among the three groups, the Shannon index, reflecting the bacterial diversity, was significantly increased in the ST4-colonized mice (Figure 1A). ST7 effects on bacterial diversity were comparable to those in fecal samples at day 0 (Figure 1A). We next performed PCoA analysis based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities to investigate the effect of Blastocystis colonization on microbial community structure (β-diversity). At baseline (day 0), the ST4, ST7, and control mice showed similar microbiota profiles (PERMANOVA p > 0.05; Figure 1B and Table S1), suggesting those group mice showed similar gut microbiota compositions before Blastocystis inoculation. After infection for two weeks, all these three groups showed significant differences compared to the baseline (PERMANOVA p < 0.05; Figure 1B and Table S1). ST4-colonized mice showed increase in the abundance of Clostridia and decrease in the proportion of Bacteroidia (Figure 1C and Figure S1E). At the genus level, the Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, and Clostridia vadinBB60 group were enriched in ST4-clonized mice (Figure 1D and Figure S1F). Bacteria from these genera are known to be beneficial bacteria, which can produce SCFAs that are a carbon source for intestinal epithelial cells and induction of Treg cells 33, 34. In contrast, ST7 infection caused the reduction in beneficial bacteria Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, and Lactobacillus, and increased the sulfate-producing bacteria Desulfovibrio (Figure 1D and Figure S1F). The enrichment of Desulfovibrio was observed in UC patients, suggesting the species of Desulfovibrio genus can be involved in colitis development 35, 36. Similarly, the proportion of Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, and Lactobacillus declined, and Desulfovibrio was enriched in control mice (Figure S1F).

Figure 1.

Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection caused differential gut microbial signatures. (A) Alpha diversity was measured by Shannon and Chao1 indices (n = 6). (B) Principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities of fecal gut microbiota derived from control (green dots), ST4 (blue dots), and ST7 (red dots) mice at day 0 and day 14. (C) Relative abundance of the different taxa at the class level. (D) Heatmap showing Blastocystis ST4 and ST7-associated taxonomic markers at day 14. (E) LefSe analysis showed the differentially abundant bacterial taxa between ST4 and ST7 groups relative to the baseline. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM.

Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis revealed that the Deferribacterales, Deferribacteraceae, Roseburia, and Peptococcus were significantly more abundant in ST4-colonized group compared to the baseline. In contrast, significant increases of Desulfovibrionales, Desulfovibrionaceae, Muribaculaceae, and Desulfovibrio were observed in ST7-infected groups (Figure 1E). In general, ST4 colonization was associated with higher proportion of beneficial bacteria, while ST7 infection decreased the abundance of beneficial bacteria and increased sulfate-producing bacteria, which may predispose the host to colitis.

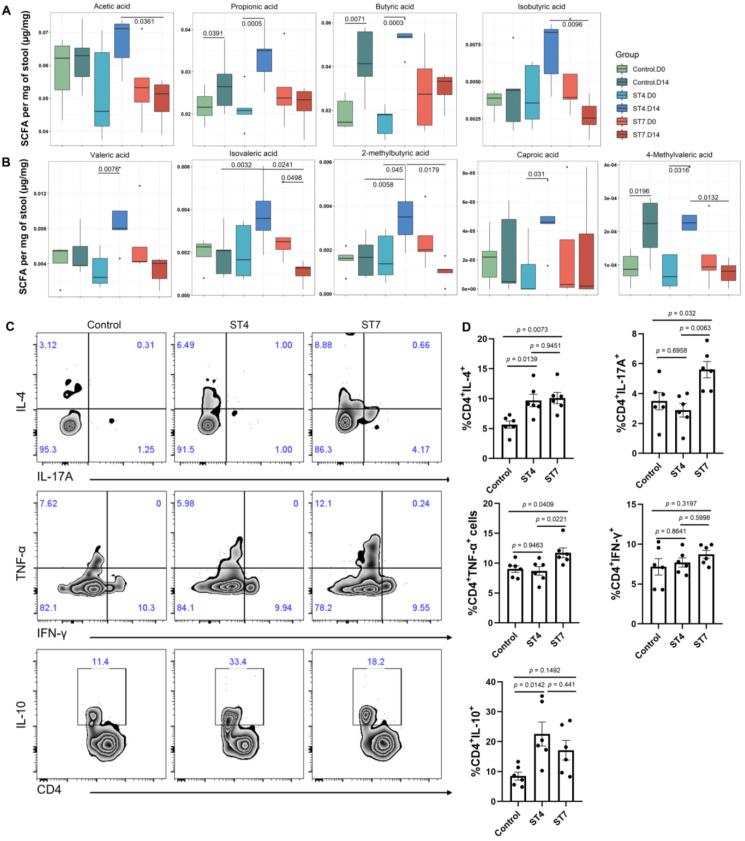

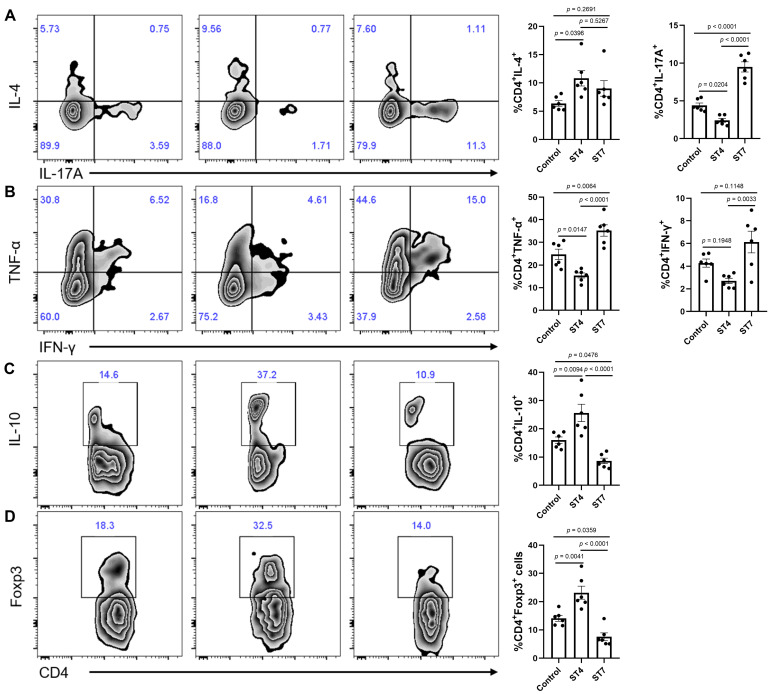

Effects of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection on SCFA production and colonic T helper cells

We next investigated whether Blastocystis infection affected the production of SCFAs, which constitute the primary energy sources for colon epithelium and play a role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis 37. Interestingly, ST4-colonized mice showed a significant increase in the majority of SCFAs (Figure 2A-B). However, ST7 did not and instead was associated with reduced isovaleric acid. (Figure 2A-B). As microbiota-derived SCFAs can regulate the adaptive immune response 38, we next investigated whether ST4 and ST7 infection could also influence host immunity (Figure S2A). ST4-colonized mice showed a substantial increase in IL-4 and IL-10-producing CD4+ T cells (Figure 2C-D), which is consistent with our previous data 15. Interestingly, the Th1 compartment (expressing TNF-α) and the Th17 subset (expressing IL-17A) were mildly but significantly increased in ST7-infected mice (Figure 2C-D). The effects of ST4 and ST7 infection on host overall health were also investigated. We observed that both ST4 and ST7-infected mice showed comparable effects on body weight change, DAI, colon length, and histopathology scores when compared to control mice (Figure S2B-C). These data suggest that ST4 and ST7 infection did not cause obvious pathological changes, but elicited different immune responses, which may affect the outcome of the host's response to other stimuli.

Figure 2.

Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection influence SCFAs production and colonic T helper cells. (A) The concentration of acetic, propionic, butyric, and isobutyric in control, ST4, and ST7 infected mice. (B) The concentration of valeric acid, isovaleric, 2-methylbutyric, and caproic acid, and 4-methylvaleric acid. (C) Zebra plots show staining for IL-4, IL-17A, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 within CD4+ T cells. (D) Bar charts show the percentage of IL-4, IL-17A, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 expressing CD4+ T cells. One-way ANOVA p-values adjusted for Tukey's multiple comparisons are shown. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM.

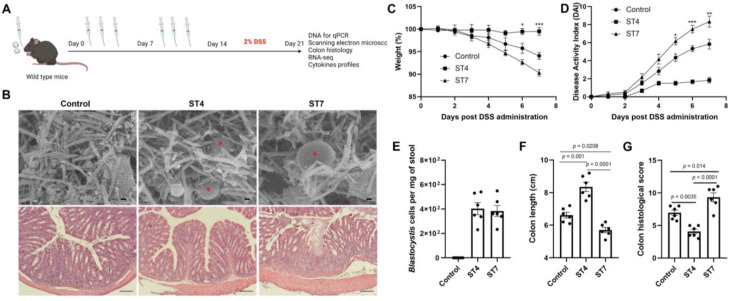

Effects of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection on the severity of experimental colitis

The gut microbiota is implicated in pathogenesis of IBD 39. Next, we explored the effects of altered gut microbiota caused by Blastocystis in the development of experimentally induced colitis. Mice were infected with Blastocystis and then subjected to induced colitis through oral DSS administration for 7 days (Figure 3A). The Blastocystis colonization status and the number of Blastocystis cells was examined (Figure 3B and 3E). We observed that ST7-infected mice treated with 2% DSS showed progressive weight loss and DAI from day 5 to day 7 (Figure 3C-D). In contrast, mice colonized with ST4 did not develop these symptoms (Figure 3C-D). Additionally, ST7 infected mice exhibited shorter colon lengths when compared to non-infected and ST4 colonized mice (Figure 3F). Histological analysis of colon tissues showed severe inflammation with loss of crypts and infiltration of inflammatory cells in ST7 infected mice, whereas ST4 colonized mice were protected from DSS-induced damage to the colon (Figure 3B and 3G). Altogether, priming mice with ST4 and ST7 showed distinct effects on the severity of DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 3.

The effects of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 colonization on subsequent DSS challenge. (A) Study design. (B) SEM of colonic and cecum tissues from control, ST4, and ST7 infected mice (upper panel), and Blastocystis are indicated with red asterisk (Scale bar = 1 μm). H&E-stained colon sections (lower panel) from the three groups (Scale bar = 100 μm). Weight changes (C), and DAI (D) in control, ST4, and ST7 infected mice. (E) The number of Blastocystis cells in ST4 and ST7 infected mice. Colon length (F) and histological scores (G) in the three groups. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison testing were used for multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

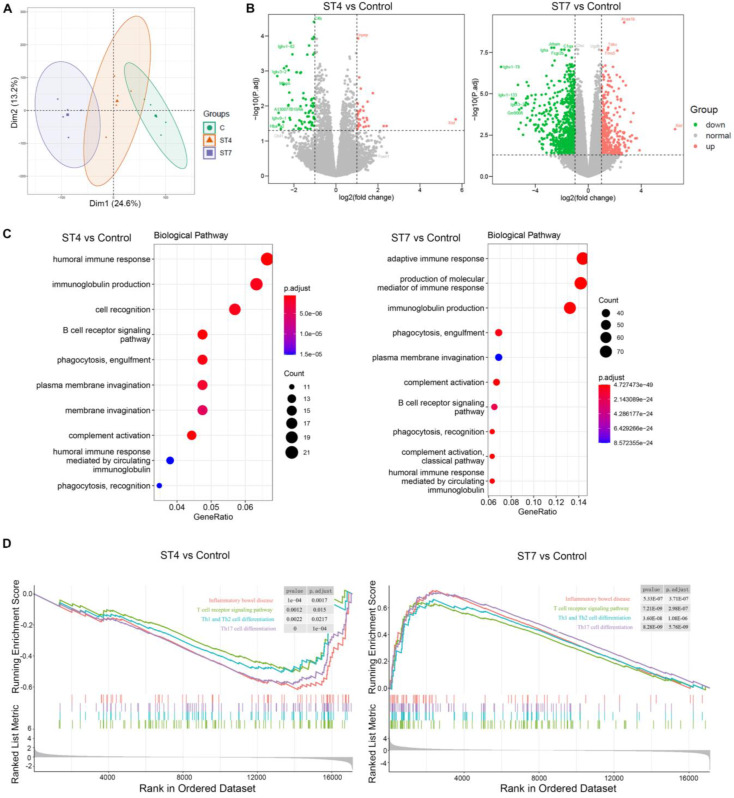

Effects of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection on mucosal gene expression in DSS-induced colitis mice

To assess the impact of Blastocystis infection on the intestinal epithelium, we analyzed the transcriptional profile of colon tissues from DSS-induced colitis mice. PCA plot showed samples from the same group clustered together (Figure 4A). Pairwise comparisons between the different groups revealed that ST4 colonized mice had 109 differential expressed genes (DEGs) (33 up-regulated and 76 down-regulated) when compared to control mice (Figure 4B). ST7 colonized mice have a far greater number of DEGs with control group than ST4, with 1,142 (391 up-regulated and 751 down-regulated) (Figure 4B). We next analyzed Gene Ontology (GO) terms, which provides a framework and set of concepts for describing the functions of gene products. Interestingly, colonization with ST4 mostly activated humoral immune response and immunoglobulin production pathways (Figure 4C). We observed that ST7 infection was related to the adaptive immune response (Figure 4C). KEGG pathway analysis showed both ST4 and ST7 infection were related to cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions (Figure S3). In addition, other categories of immune-related pathways, such as Th17 cell differentiation and inflammatory bowel diseases, were associated with ST7 infection (Figure S3). To better understand the molecular mechanisms of complex biochemical reactions, we then applied GSEA on the DEGs. We found that ST4 colonization caused a marked reduction in normalized enrichment scores (NESs) for inflammatory bowel disease, T cell receptor signaling pathway, Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation, and Th17 cell differentiation (Figure 4D). In contrast, increased scores for each of these gene sets were found in ST7 infected groups (Figure 4D). In general, the induction seems to be higher for ST7 from the gene ratio which induced more gene profile responses. Mice with prior ST4 colonization are refractory to colitis, associated with protective immune responses, while ST7 infection caused worsening of colitis, related to pro-inflammatory immune responses.

Figure 4.

Gene expression in ST4 and ST7-infected colon tissues after DSS treatment. (A) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot comparing mouse transcriptomes among control, ST4, and ST7 infected mice. (B) Volcano plots showing log2 fold change plotted against log of mean normalized expression counts. (C) The top 10 most enriched GO terms found in the analysis of DEGs in ST4 vs. Control group, and ST7 vs. Control group. GO terms were ranked by their significance. (D) GSEA analysis showed the gene sets of inflammatory bowel disease, T cell receptor signaling pathway, Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation, and Th17 cell differentiation. Graphs depict the enrichment score (y axis) with negative values where gene sets are inhibited, and positive values where they are induced. Each vertical bar on the x axis represents an individual gene within the gene set, and its relative ranking against all genes analyzed. P and Padj value is indicated on the graph.

Effects of Blastocystis ST4 and ST7 infection on colonic T helper cells in DSS-induced colitis mice

T helper cells are thought to play a crucial role in the development of IBD 40. To further investigate whether ST4 and ST7 infection caused changes related to T helper cells, we measured the distribution of Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells within T cells isolated from colonic mucosa. In contrast to ST4 colonized mice, infection with ST7 markedly increased the percentage of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-17A and TNF-α-producing T cells in the colonic lamina propria (LP) (Figure 5A-B). Concomitantly, the percentage of T cells expressing anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was significantly reduced (Figure 5C). Forkhead box protein 3 (Foxp3) is essential in the development, maintenance, and function of Treg cells, which play a critical role in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis 41. ST4 colonized mice showed a substantial accumulation of Foxp3+ Tregs (Figure 5D). Together, these results suggest that increased susceptibility to colitis after ST7 infection is associated with the induction of pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 responses, while ST4 colonization confers resistance to colitis related to protective immune responses.

Figure 5.

Colonic immune profiles in control, ST4, and ST7 infected mice after treatment with DSS. (A) Zebra plots and bar charts show staining and the percentage of IL-4, and IL-17A within CD4+ T cells. (B) Zebra plots and bar charts show staining and the percentage of TNF-α, and IFN-γ within CD4+ T cells. Zebra plots and bar charts show staining and the percentage of IL-10 (C) and Foxp3 (D) within CD4+ T cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA p-values adjusted for Tukey's multiple comparisons are shown.

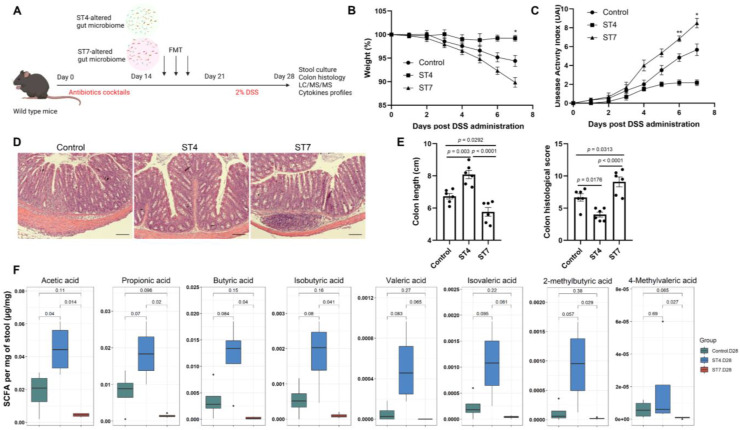

Effects of Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota on the severity of experimental colitis

We next sought to determine whether the Blastocystis-altered microbiota played a direct role in the worsening of, or protection against, DSS colitis. To exclude the effects of Blastocystis on the severity of colitis, feces from Blastocystis infected mice were frozen at -80°C at least one week before starting the FMT. This treatment ruptures and destroys Blastocystis organisms (Figure S4). Recipient mice were treated with antibiotic cocktails to deplete the gut microbiota and then gavaged with ST4 and ST7-altered gut microbiota (Figure 6A). The recipient mice that received FMT from ST4 donor mice had less severe colitis when challenged with DSS, reflected by weight changes and DAI (Figure 6B-C). In contrast, body weight decreased significantly, and DAI tended to be higher in recipients of the ST7-altered microbiota (Figure 6B-C). Additionally, recipients of the ST7-altered microbiota had significantly shorter colon lengths than control recipients, whereas recipients of the ST4-altered microbiota had significantly longer colon lengths (Figure 6E). Histology analysis showed that recipients of the ST4-altered microbiota had significantly lower histological scores than control and ST7-altered microbiota recipients (Figure 6D-E). These findings provide evidence that the Blastocystis-altered microbiota, even without Blastocystis present, was sufficient to worsen or protect the mice from the DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 6.

Effects of Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota on the severity of experimental colitis. (A) Study design. Weight changes (B) and DAI (C) in control, ST4, and ST7 altered microbiota recipient mice. (D) H&E-stained colon sections from the three groups (Scale bar = 100 μm). (E) colon length and histological scores in the three groups. (F) The concentration of acetic, propionic, butyric, and isobutyric, valeric acid, isovaleric, 2-methylbutyric, and caproic acid, and 4-methylvaleric acid in the recipient mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA p-values adjusted for Tukey's multiple comparisons are shown (E, F). Two-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison testing were used for multiple comparisons (B, C). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

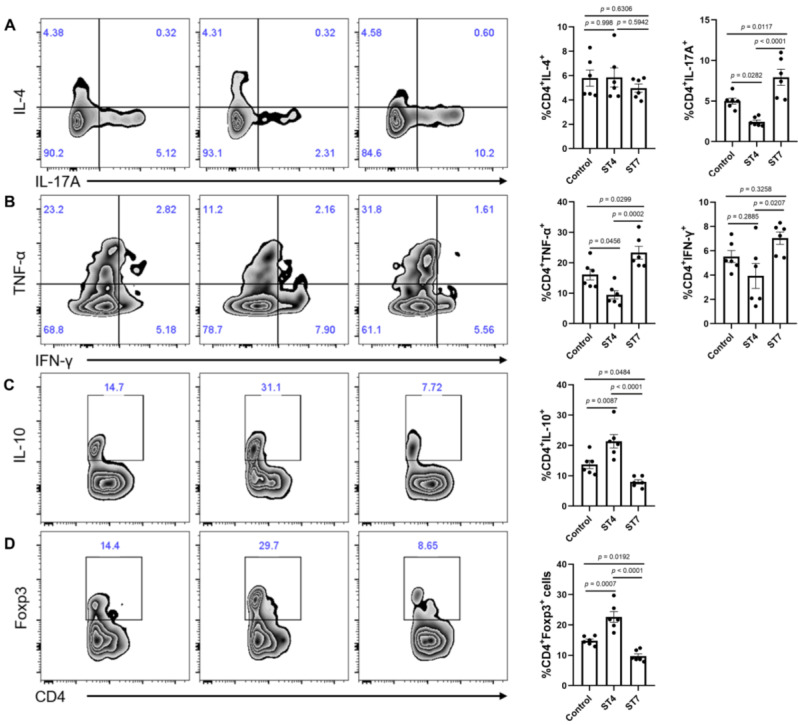

Effects of Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota on SCFA production and colonic T helper cells

To understand mechanistically how ST4 and ST7-altered gut microbiota differentially impact DSS-induced colitis, we measured the concentration of SCFAs among the three groups to determine whether these were associated with the development of colitis. The concentrations of acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, 2-methylbutyric acid, and 4-methylvaleric acid in fecal samples of ST4-colonized mice were significantly higher than in ST7-infected mice (Figure 6F). We next sought to investigate whether the Blastocystis altered microbiota can modulate the colonic adaptive immune responses. Although there was no significant difference in the percentage of IL-4-producing Th2 cells among the three groups, we observed a substantial increase in IL-10+ and Foxp3+ Treg cells in the colonic mucosa of ST4-altered microbiota recipients (Figure 7A, C-D). Similarly, we also detected a significant expansion of TNF-α-producing CD4+ Th1 cells and IL-17A-producing CD4+ Th17 cells after receipt of the ST7-altered microbiota (Figure 7A-B). These data showed that Blastocystis-altered gut microbiota play a significant role in the regulation of the pathogenesis of DSS-induced colitis by affecting adaptive immune responses.

Figure 7.

Colonic immune profiles from recipient mice. (A) Zebra plots and bar charts show staining and the percentage of IL-4, and IL-17A within CD4+ T cells. (B) Zebra plots and bar charts show staining and the percentage of TNF-α, and IFN-γ within CD4+ T cells. Zebra plots and bar charts show staining and the percentage of IL-10 (C) and Foxp3 (D) within CD4+ T cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments and shown as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA p-values adjusted for Tukey's multiple comparisons are shown.

Discussion

Growing evidence suggests that parasitic infections can influence the severity of colitis in a mouse model of IBD 42, 43. Infection with the tapeworm Hymenolepis diminuta suppressed experimentally-induced colitis in mice dependent on gut microbiota, suggesting the gut microbiota may influence the outcome of infection and disease 44. In this study, two subtypes were used to investigate the effects of Blastocystis on host health. ST4 is more often found in rodents than ST7 which is commonly found in birds 45, suggesting that subtype specificity may play a role in the clinical outcome of Blastocystis infection. We demonstrated that mice colonized with Blastocystis ST4 showed an increase in the beneficial bacteria Lachnospiraceae and Clostridia vadinBB60 group, which protected the mice when challenged with DSS-induced colitis. However, Blastocystis ST7 infection decreased the abundance of beneficial bacteria Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, Lactobacillus, and Roseburia, and increased the level of sulfate-producing bacteria Desulfovibrio, which may have exacerbated the severity of the experimental colitis. These findings suggested that Blastocystis may serve as a critical component of the anti-colitic or pro-colitic effects in an animal model of colitis through regulating the gut microbiota.

The associations between Blastocystis and gut microbiota have been explored in several studies in recent years 46, 47. Although most studies showed Blastocystis-carriers are asymptomatic and have healthy gut microbiota, other studies revealed that Blastocystis infection was associated with decreased executive functions in humans 48, and fecal dysbiosis in a mouse model 49. It has been suggested that different subtypes exhibited differential effects on the development of the experimental colitis 14, 15, 50. For example, long-term Blastocystis ST3 colonization promotes a faster recovery from dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (DNBS) induced colitis through stabilization of the gut microbiota 50. In contrast, severe colonic damage and ulceration were observed in Blastocystis ST7 infected mice when exposed to DSS accompanied by disrupted gut microbiota 14.

In this study, we observed that Blastocystis ST4 not only increased the well-known SCFA-producing bacteria but increased the concentration of SCFAs, while Blastocystis ST7 did not show such effects, and, to some extent, decreased the level of some SCFAs. SCFAs are the main metabolites produced by the gut microbiota through the anaerobic fermentation of substrates, such as fibers and resistant starch, which play a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homoeostasis 51. Decreased numbers of SCFA-producing bacteria and lower concentrations of fecal SCFAs were also observed in IBD patients 52, 53. SCFAs also regulate immune cells, especially Tregs, by inhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity or through GPRC receptors, exerting anti-inflammatory effects 54.

High Th1 and Th17 cytokine production in colonic mucosa was related to clinical manifestation of colitis 55. Th2 immune responses can antagonize the production of Th1 cytokines to alleviate colitis 56. Besides, IL-10-producing Treg cells also can suppress pathogenic Th17 cell responses 57. Our data support a mechanism whereby colonization with Blastocystis ST4 causes an increased abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria and concentration of SCFAs, which mediates the suppression of colitis by the expansion of Tregs in the colonic mucosa. In contrast, ST7 infection decreased the proportion of beneficial bacteria and SCFAs and increased the sulfate-reducing bacteria, which worsened the severity of colitis through the induction of pro-inflammatory Th1 and Th17 cytokines.

It has been demonstrated that the excretory or secretory products from helminths can inhibit tuft and goblet cells to block the effects of IL-4 and IL-13 in mice 58. On the other hand, secreted products can induce Foxp3+ Tregs by activating TGF-β signaling 59. Although live Blastocystis cells were excluded from the Blastocystis-altered microbiota FMT experiments, we could not exclude the influence of excretory/secretory products on the severity of colitis through FMT. Future directions will explore whether Blastocystis can affect gut microbiota composition through secreted products or extracellular vesicles, and whether Blastocystis can also modulate the development and progression of inflammatory diseases through excretory/secretory products and other small molecules, such as bile acids and tryptophan metabolites.

FMT is a common therapeutic strategy for restoring disrupted microbiota 60. It has been used as an ordinary standard therapy for recurrent C. difficile infection (rCDI) 61, and some trials have reported its potential to alleviate or treat IBD 62. The present consensus for FMT is to exclude Blastocystis-positive donor samples 61, 63, though the pathogenicity of Blastocystis remains controversial 64. The presence of Blastocystis-positive (ST1 and ST3) donor samples for FMT in treatment rCDI did not cause any adverse gastrointestinal symptoms 65, suggesting that certain subtypes can be used for FMT. Since ST1, ST2, and ST3 are very common in humans, donors colonized by one of these 3 subtypes are probably acceptable. Our data show that transplantation of ST4-altered gut microbiota protected mice from later DSS-induced colitis, while ST7 caused converse effects, suggesting the necessity for differentiation of Blastocystis-positive donors at the subtype level. Besides, it should be noted that the effects of different strains from the same subtype may also impact intestinal health. For example, the extensive intra-ST7 variability in inducing intestinal barrier dysfunction was observed in our previous study 16, suggesting intra-subtype variability may explain the discrepancy of pathogenicity in Blastocystis.

Conclusions

We report, for the first time, that colonization with Blastocystis ST4 exerted a protective effect against the onset of intestinal inflammation by increasing the proportion of beneficial bacteria and SCFAs, and the regulation of colonic CD4 T cells. ST7 infection caused opposite effects on DSS-induced acute colitis. Moreover, transplantation of ST4 and ST7-altered gut microbiota was sufficient to transfer the protective and inflammatory phenotypes respectively. As the murine model is not exactly reflective of the human gut in the case of Blastocystis infection, it is necessary to perform, in future studies, human gut microbiome studies to reveal the precise roles of ST4 and ST7 on intestinal inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and table.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chua Yen Leong for assistance in animal work, and Dr. Zhiyuan Lu for the help in histology experiments. We also would like to thank Ms. Geok Choo Ng and Dr. Paul Edward Hutchinson for providing technical support.

Funding

This work was supported by NUHS Seed Grant R-571-000-061-114 to NRJG, R-148-000-277-114 to ECYC and R-571-000-037-114 to KSWT. KSWT also acknowledges the Blastocystis Under One Health Grant (A-8000685-00-00) for supporting this study.

Author contributions

L.D. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data; L.W. and L.D. performed immunological experiments; C.W.P. and Y.Z. performed and interpreted histological analyses; K.Y.Q.D., Y.G. and E.C.Y.C. performed and interpreted LC/MS/MS assays; T.T.A. and B.M. performed the scanning electron microscopy experiments; G.P. and N.R.J.G. provided scientific insights and critically reviewed the manuscript. K.S.W.T. designed, conceived, and supervised the study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database at NCBI under BioProject ID PRJNA856792 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA856792).

Abbreviations

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- CD

Crohn's disease

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- Th

T helper

- Treg

T regulatory

- DSS

Dextran sulfate sodium

- IMDM

Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- DAI

Disease activity index

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- QIIME

Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology

- PERMANOVA

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance

- PCoA

Principal co-ordinates analysis

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- FCS

Fetal calf serum

- FBS

Fetal Bovine Serum

- IL

Interleukin

- IFN-γ

Interferon gamma

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- LP

Lamina propria

- FMT

Fecal microbiota transplantation

- SCFAs

Short-chain fatty acids

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

References

- 1.Ananthakrishnan AN. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:205–17. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plichta DR, Graham DB, Subramanian S, Xavier RJ. Therapeutic opportunities in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanistic dissection of host-microbiome relationships. Cell. 2019;178:1041–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:13–27. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016;8:51. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzzo GL, Andrews JM, Weyrich LS. The neglected gut microbiome: fungi, protozoa, and bacteriophages in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022. 1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Moonah SN, Jiang NM, Petri WA Jr. Host immune response to intestinal amebiasis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003489. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotloff KL. The burden and etiology of diarrheal illness in developing countries. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;64:799–814. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan KSW. New insights on classification, identification, and clinical relevance of Blastocystis spp. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:639–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cekin AH, Cekin Y, Adakan Y, Tasdemir E, Koclar FG, Yolcular BO. Blastocystosis in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms: a case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirvani G, Fasihi-Harandi M, Raiesi O, Bazargan N, Zahedi MJ, Sharifi I. et al. Prevalence and molecular subtyping of Blastocystis from patients with irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease and chronic urticaria in iran. Acta Parasitol. 2020;65:90–6. doi: 10.2478/s11686-019-00131-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stensvold CR, van der Giezen M. Associations between gut microbiota and common luminal intestinal parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34:369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng L, Wojciech L, Gascoigne NRJ, Peng G, Tan KSW. New insights into the interactions between Blastocystis, the gut microbiota, and host immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009253. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon L, Mansor S, Mallon P, Donnelly E, Hoper M, Loughrey M, Kirk S, Gardiner K. The dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) model of colitis: an overview. Comparative Clin Pathol. 2010;19:235–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yason JA, Liang YR, Png CW, Zhang Y, Tan KSW. Interactions between a pathogenic Blastocystis subtype and gut microbiota: in vitro and in vivo studies. Microbiome. 2019;7:30. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0644-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng L, Wojciech L, Png CW, Koh EY, Aung TT, Kioh DYQ. et al. Experimental colonization with Blastocystis ST4 is associated with protective immune responses and modulation of gut microbiome in a DSS-induced colitis mouse model. Cellul Mol Life Sci. 2022;79:245. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z, Mirza H, Tan KS. Intra-subtype variation in enteroadhesion accounts for differences in epithelial barrier disruption and is associated with metronidazole resistance in Blastocystis subtype-7. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim MX, Png CW, Tay CY, Teo JD, Jiao H, Lehming N, Tan KS, Zhang Y. Differential regulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression by mitogen-activated protein kinases in macrophages in response to intestinal parasite infection. Infect Immun. 2014;82:4789–801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02279-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho LC, Singh M, Suresh G, Ng GC, Yap EH. Axenic culture of Blastocystis hominis in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium. Parasitology research. 1993;79:614–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00932249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen XQ, Singh M, Ho LC, Moe KT, Tan SW, Yap EH. A survey of Blastocystis sp. in rodents. Lab Ani Sci. 1997;47:91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest. 1993;69:238–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belda E, Voland L, Tremaroli V, Falony G, Adriouch S, Assmann KE. et al. Impairment of gut microbial biotin metabolism and host biotin status in severe obesity: effect of biotin and prebiotic supplementation on improved metabolism. Gut. 2022;71:2463–80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burrello C, Garavaglia F, Cribiù FM, Ercoli G, Lopez G, Troisi J. et al. Therapeutic faecal microbiota transplantation controls intestinal inflammation through IL10 secretion by immune cells. Nat Comm. 2018;9:5184. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07359-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra A, Lai GC, Yao LJ, Aung TT, Shental N, Rotter-Maskowitz A. et al. Microbial exposure during early human development primes fetal immune cells. Cell. 2021;184:3394–409.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poirier P, Wawrzyniak I, Albert A, El Alaoui H, Delbac F, Livrelli V. Development and evaluation of a real-time PCR assay for detection and quantification of Blastocystis parasites in human stool samples: prospective study of patients with hematological malignancies. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:975–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01392-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melgar S, Karlsson L, Rehnström E, Karlsson A, Utkovic H, Jansson L, Michaëlsson E. Validation of murine dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis using four therapeutic agents for human inflammatory bowel disease. Intern Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:836–44. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:590–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucl Aacids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha Vamsi K, Mukherjee S, Ebert Benjamin L, Gillette Michael A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Nal Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson K-F, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J. et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan JC, Kioh DY, Yap GC, Lee BW, Chan EC. A novel LCMSMS method for quantitative measurement of short-chain fatty acids in human stool derivatized with (12)C- and (13)C-labelled aniline. J Pharmaceutical Biomedical Anal. 2017;138:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vital M, Karch A, Pieper DH. Colonic butyrate-producing communities in humans: an overview using omics data. mSystems. 2017;2:e00130–17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00130-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushkevych I, Dordević D, Vítězová M. Possible synergy effect of hydrogen sulfide and acetate produced by sulfate-reducing bacteria on inflammatory bowel disease development. J Adv Res. 2021;27:71–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowan F, Docherty NG, Murphy M, Murphy B, Coffey JC, O'Connell PR. Desulfovibrio bacterial species are increased in ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1530–6. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f1e620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Hee B, Wells JM. Microbial Regulation of Host Physiology by Short-chain Fatty Acids. Trends Microbiol. 2021;29:700–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang W, Yu T, Huang X, Bilotta AJ, Xu L, Lu Y. et al. Intestinal microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulation of immune cell IL-22 production and gut immunity. Nat Comm. 2020;11:4457. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18262-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishida A, Inoue R, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Naito Y, Andoh A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0813-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Imam T, Park S, Kaplan MH, Olson MR. Effector T Helper Cell Subsets in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1212. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopes F, Matisz C, Reyes JL, Jijon H, Al-Darmaki A, Kaplan GG, McKay DM. Helminth regulation of immunity: a three-pronged approach to treat colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2499–512. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith P, Mangan NE, Walsh CM, Fallon RE, McKenzie ANJ, van Rooijen N, Fallon PG. Infection with a Helminth Parasite Prevents Experimental Colitis via a Macrophage-Mediated Mechanism. J Immunol. 2007;178:4557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shute A, Callejas BE, Li S, Wang A, Jayme TS, Ohland C, Lewis IA, Layden BT, Buret AG, McKay DM. Cooperation between host immunity and the gut bacteria is essential for helminth-evoked suppression of colitis. Microbiome. 2021;9:186. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hublin JSY, Maloney JG, Santin M. Blastocystis in domesticated and wild mammals and birds. Research in veterinary science. 2021;135:260–282. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Even G, Lokmer A, Rodrigues J, Audebert C, Viscogliosi E, Ségurel L, Chabé M. changes in the human gut microbiota associated with colonization by Blastocystis sp. and Entamoeba spp. in non-industrialized populations. Front Cell Infecti Microbiol. 2021;11:533528. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.533528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stensvold CR, Sørland BA, Berg R, Andersen LO, van der Giezen M, Bowtell JL, El-Badry AA, Belkessa S, Kurt Ö, Nielsen HV. Stool microbiota diversity analysis of Blastocystis-positive and Blastocystis-negative individuals. Microorganisms. 2022;10:326. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mayneris-Perxachs J, Arnoriaga-Rodríguez M, Garre-Olmo J, Puig J, Ramos R, Trelis M. et al. Presence of Blastocystis in gut microbiota is associated with cognitive traits and decreased executive function. ISME J. 2022;16:2181–97. doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01262-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Defaye M, Nourrisson C, Baudu E, Lashermes A, Meynier M, Meleine M. et al. Fecal dysbiosis associated with colonic hypersensitivity and behavioral alterations in chronically Blastocystis-infected rats. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9146. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66156-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Billy V, Lhotská Z, Jirků M, Kadlecová O, Frgelecová L, Parfrey LW, Pomajbíková KJ. Blastocystis colonization alters the gut microbiome and, in some cases, promotes faster recovery from induced colitis. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:641483. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.641483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russo E, Giudici F, Fiorindi C, Ficari F, Scaringi S, Amedei A. Immunomodulating activity and therapeutic effects of short chain fatty acids and tryptophan post-biotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2754. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrer-Picón E, Dotti I, Corraliza AM, Mayorgas A, Esteller M, Perales JC. et al. intestinal inflammation modulates the epithelial response to butyrate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. se. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:43–55. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiu P, Ishimoto T, Fu L, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Liu Y. The gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:733992. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.733992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park J, Kim M, Kang SG, Jannasch AH, Cooper B, Patterson J, Kim CH. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR-S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:80–93. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harbour Stacey N, Maynard Craig L, Zindl Carlene L, Schoeb Trenton R, Weaver Casey T. Th17 cells give rise to Th1 cells that are required for the pathogenesis of colitis. Proc Nal Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:7061–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415675112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Motomura Y, Wang H, Deng Y, El-Sharkawy RT, Verdu EF, Khan WI. Helminth antigen-based strategy to ameliorate inflammation in an experimental model of colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaudhry A, Samstein RM, Treuting P, Liang Y, Pils MC, Heinrich J-M. et al. Interleukin-10 signaling in regulatory T cells is required for suppression of Th17 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity. 2011;34:566–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drurey C, Lindholm HT, Coakley G, Poveda MC, Löser S, Doolan R. et al. Intestinal epithelial tuft cell induction is negated by a murine helminth and its secreted products. J Exp Medi. 2022;219:e20211140. doi: 10.1084/jem.20211140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnston CJC, Smyth DJ, Kodali RB, White MPJ, Harcus Y, Filbey KJ. et al. A structurally distinct TGF-β mimic from an intestinal helminth parasite potently induces regulatory T cells. Nat Comm. 2017;8:1741. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01886-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang F, Cui B, He X, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D. Microbiota transplantation: concept, methodology and strategy for its modernization. Protein Cell. 2018;9:462–73. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0541-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Terveer EM, van Beurden YH, Goorhuis A, Mulder CJJ, Kuijper EJ, Keller JJ. Faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2018;67:196. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Groot PF, Frissen MN, de Clercq NC, Nieuwdorp M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in metabolic syndrome: History, present and future. Gut Microbes. 2017;8:253–67. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2017.1293224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, Rajilić-Stojanović M, Kump P, Satokari R. et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2017;66:569–80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andersen LO, Stensvold CR. Blastocystis in health and disease: are we moving from a clinical to a public health perspective? J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:524–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02520-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Terveer EM, van Gool T, Ooijevaar RE, Sanders I, Boeije-Koppenol E, Keller JJ. et al. Human transmission of Blastocystis by Fecal Microbiota Transplantation without development of gastrointestinal symptoms in recipients. Clin Infect Dise. 2019;71:2630–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and table.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database at NCBI under BioProject ID PRJNA856792 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA856792).