ABSTRACT

New strategies are urgently needed to address the public health threat of antimicrobial resistance. Synergistic agent combinations provide one possible pathway toward addressing this need and are also of fundamental mechanistic interest. Effective methods for comprehensively identifying synergistic agent combinations are required for such efforts. In this study, an FDA-approved drug library was screened against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (ATCC 43300) in the absence and presence of sub-MIC levels of ceftobiprole, a PBP2a-targeted anti-MRSA β-lactam. This screening identified numerous potential synergistic agent combinations, which were then confirmed and characterized for synergy using checkerboard analyses. The initial group of synergistic agents (sum of the minimum fractional inhibitory concentration ∑FICmin ≤0.5) were all β-lactamase-resistant β-lactams (cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, flucloxacillin, oxacillin, nafcillin, and cefotaxime). Cloxacillin—the agent with the greatest synergy with ceftobiprole—is also highly synergistic with ceftaroline, another PBP2a-targeted β-lactam. Further follow-up studies revealed a range of ceftobiprole synergies with other β-lactams, including with imipenem, meropenem, piperacillin, tazobactam, and cefoxitin. Interestingly, given that essentially all other ceftobiprole-β-lactam combinations showed synergy, ceftaroline and ceftobiprole showed no synergy. Modest to no synergy (0.5 < ∑FICmin ≤ 1.0) was observed for several non-β-lactam agents, including vancomycin, daptomycin, balofloxacin, and floxuridine. Mupirocin had antagonistic activity with ceftobiprole. Flucloxacillin appeared particularly promising, with both a low intrinsic MIC and good synergy with ceftobiprole. That so many β-lactam combinations with ceftobiprole show synergy suggests that β-lactam combinations can generally increase β-lactam effectiveness and may also be useful in reducing resistance emergence and spread in MRSA.

IMPORTANCE Antimicrobial resistance represents a serious threat to public health. Antibacterial agent combinations provide a potential approach to combating this problem, and synergistic agent combinations—in which each agent enhances the antimicrobial activity of the other—are particularly valuable in this regard. Ceftobiprole is a late-generation β-lactam antibiotic developed for MRSA infections. Resistance has emerged to ceftobiprole, jeopardizing this agent’s effectiveness. To identify synergistic agent combinations with ceftobiprole, an FDA-approved drug library was screened for potential synergistic combinations with ceftobiprole. This screening and follow-up studies identified numerous β-lactams with ceftobiprole synergy.

KEYWORDS: library screening, drug repurposing, Staphylococcus aureus, synergy, antibiotic drug resistance, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, ceftobiprole, ceftaroline, cloxacillin

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenic bacteria are becoming increasingly drug resistant, with some now virtually untreatable (1–4). There has concurrently been a lack of new antibacterial agents to counter this threat (5–8). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the ESKAPE (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species) pathogens and a common cause of both nosocomial and community-acquired infections (9–12). It is characterized by resistance to most commonly used β-lactam antibiotics and to many other antibiotic classes and agents (13). High-level resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in MRSA is due to its acquisition of a novel β-lactam-resistant penicillin-binding protein (PBP), PBP2a (14, 15). PBP2a has substantially reduced affinity for classical β-lactamase-resistant β-lactams, such as methicillin (14, 16), due to a restricted active site (17). While MRSA has remained susceptible to vancomycin, resistance to vancomycin in MRSA is slowly increasing (18). Relatively recently, two new cephalosporin β-lactam antibiotics have been developed which are active against MRSA due to their ability to inhibit PBP2a: ceftobiprole (19, 20) and ceftaroline (21, 22). Resistance to ceftobiprole and ceftaroline has, however, also emerged (23–27).

There is a well-recognized need for new agents and approaches to combat the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance (3, 7). Drug combination-based approaches offer the prospect of improving treatment efficacy and reducing the emergence of resistance to currently effective agents (28–32). Synergistic and antagonistic agent combinations are also of high value as probes of bacterial physiology (28, 33, 34). Methods for identifying synergistic agent combinations range from testing one to several antibiotic combinations for synergy to the screening of substantial chemical compound libraries (28, 33, 35, 36).

In a prior study (37), an FDA library screen was performed against MRSA for agents which could act synergistically with cefoxitin—a β-lactam antibiotic to which MRSA is highly but not completely resistant. This screen identified several FDA-approved agents that act synergistically with cefoxitin, including the interesting finding of strong synergy with floxuridine. However, none of the cefoxitin synergistic agents could return cefoxitin’s MIC to a therapeutic level. In this study, a similar screen was performed of an FDA-approved drug library against MRSA in the absence and presence of ceftobiprole—a newer β-lactam designed to circumvent PBP2a-based β-lactam resistance. The goal of this effort was to comprehensively identify FDA-approved drugs that can act synergistically with ceftobiprole. These results are interesting from a mechanistic perspective and suggest several ceftobiprole combinations which may have clinical potential.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This study used the same FDA-approved drug library, target MRSA strain (ATCC 43300; F-182), and screening approach previously reported for a −/+cefoxitin screen (37). Library screening was performed using 25 μM of each library compound, one set in the absence of ceftobiprole and one set in the presence of sub-MIC (0.25 μg mL−1 = 1/8×MIC) ceftobiprole. Any FDA compound which showed activity in the absence or presence of ceftobiprole was added to a merged hit list, and MICs were determined for the agents on this list in both the absence and presence of 0.25 μg mL−1 ceftobiprole. The MICs for compounds with a minimum MIC of ≤3.1 μM under any tested condition (−/+ceftobiprole) are listed in Table 1. The degree of the effect of the added ceftobiprole on the test agent MIC is indicated by the L2(−/+ceftobiprole) values:

| (1) |

TABLE 1.

FDA library anti-MRSA hit MICs sorted by the greatest apparent decrease in MICs with the addition of 0.25 μg mL−1 ceftobiprole

| Compound | MIC (μM) |

Min_MIC (μM) | L2(–/+BPR)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| –BPRa | +BPR | |||

| Cloxacillin | 25 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 4 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.78 | 9.8E–2 | 9.8E–2 | 3 |

| Gemcitabine | 2.4E–2 | 3.1E–3 | 3.1E–3 | 3 |

| Daptomycin | 0.39 | 9.8E–2 | 9.8E–2 | 2 |

| Doxycycline | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 2 |

| Floxuridine | 2.4E–2 | 6.1E–3 | 6.1E–3 | 2 |

| Methacycline | 1.6 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 2 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.20 | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 2 |

| Sitafloxacin | 4.9E–2 | 1.2E–2 | 1.2E–2 | 2 |

| Tetracycline | 3.1 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 2 |

| Vancomycin | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1 |

| Difloxacin | 0.78 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 1 |

| Doxifluridine | 1.6 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 1 |

| Marbofloxacin | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1 |

| Nadifloxacin | 9.8E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 1 |

| Novobiocin | 9.8E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 1 |

| Pefloxacin | 1.6 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1 |

| Rifapentine | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1 |

| Sparfloxacin | 1.6 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1 |

| Balofloxacin | 2.4E–2 | 1.2E–2 | 1.2E–2 | 1 |

| 5-Fluorouracil | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 0 |

| Retapamulin | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 0 |

| Rifabutin | 9.8E–2 | 9.8E–2 | 9.8E–2 | 0 |

| Rifampin | 1.2E–2 | 1.2E–2 | 1.2E–2 | 0 |

| Valnemulin | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 0 |

| Rifaximin | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 4.9E–2 | 0 |

| Mupirocin | 0.39 | 3.1 | 0.39 | −3 |

BPR, ceftobiprole.

.

Checkerboard assays were then used to confirm and characterize prospective ceftobiprole synergistic agents (L2(−/+ceftobiprole) ≥ 2) and for the one prospective ceftobiprole antagonistic agent (mupirocin; L2(−/+ceftobiprole) ≤ 2). Cloxacillin demonstrated particularly strong synergy with ceftobiprole (sum of the minimum fractional inhibitory concentration (∑FICmin = 0.21) (Fig. 1a), and several other β-lactamase-resistant β-lactams not in the original library were then added to the checkerboard analysis (cefotaxime, ceftaroline, oxacillin, nafcillin, cloxacillin, dicloxacillin, and flucloxacillin) to evaluate the scope of this synergy (Fig. 1; Table 2). The most synergistic agent combinations for ceftobiprole are with β-lactamase-resistant β-lactams. Cloxacillin was the most synergistic of these, followed by cefotaxime, oxacillin, flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin, and nafcillin (Fig. 1a to f). Dicloxacillin and flucloxacillin also had relatively low intrinsic (without ceftobiprole) MICs (2.2 μM or 1.0 μg mL−1 each) (Table 2), consistent with prior observations for dicloxacillin against MRSA (38).

FIG 1.

Checkerboard assay results for combinations of ceftobiprole with the best synergistic agents listed in the top section of Table 2. Isobolograms for combinations of ceftobiprole (x axes) with (y axes) cloxacillin (a), cefotaxime (b), oxacillin(c), flucloxacillin (d), nafcillin (e), dicloxacillin (f), vancomycin (g), balofloxacin (h), and floxuridine (i). ∑FICmin values are shown in the insets.

TABLE 2.

Checkerboard assay results for potentially synergistic and antagonistic agentsa

| Reference | Agent | MIC (μM) | MIC (μg/mL) | ∑FICminb | ∑FICmaxc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Table 1; Fig. 1 | Cloxacillin | 35 | 15 | 0.21 | 1 |

| Cefotaxime | 71 | 32 | 0.30 | 1 | |

| Oxacillin | 71 | 28 | 0.30 | 1 | |

| Flucloxacillin | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.30 | 1 | |

| Dicloxacillin | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.38 | 1 | |

| Nafcillin | 71 | 29 | 0.43 | 1 | |

| Vancomycin | 0.78 | 1.1 | 0.60 | 1 | |

| Balofloxacin | 0.02 | 6.7E–3 | 0.75 | 1 | |

| Floxuridine | 0.024 | 5.9E–3 | 0.75 | 1 | |

| Rifaximin | 0.049 | 3.9E–2 | 0.80 | 1 | |

| Daptomycin | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.83 | 1.1 | |

| Gemcitabine | 0.024 | 6.3E–3 | 0.96 | 1.1 | |

| Tetracycline | 8.8 | 3.9 | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Doxycycline | 0.28 | 0.12 | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.14 | 5.6E–2 | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Sitafloxacin | 0.035 | 1.4E–2 | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.39 | 0.15 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Rifabutin | 0.086 | 7.3E–2 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Mupirocin | 0.78 | 0.39 | 1 | 2.7 | |

| Fig. 2 | Imipenem | 17 | 5.3 | 0.26 | 1 |

| Meropenem | 31 | 12 | 0.38 | 1 | |

| Ceftaroline fosamil | 8.8 | 6.6 | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Cefoxitin sodium | 55 | 25 | 0.48 | 1 | |

| Tazobactam | 500 | 150 | 0.385 | 1 | |

| Piperacillin Sodium | 35 | 19 | 0.43 | 1 | |

| Tazobactam/piperacillin (1:1 wt:wt) | 58:32 | 18:18 | 0.50 | 1 | |

| Fig. 2e | Cloxacillin | 0.54 | 0.23d | 0.50 | 1 |

The upper section lists agents identified in Table 1 and several additional β-lactamase-resistant β-lactams (Fig. 1) against MRSA (ATCC 43300). The middle section lists additional follow-up agents (Fig. 2) against MRSA. The bottom row shows the results of a test of the best MRSA synergistic agent (cloxacillin) against an MSSA strain (ATCC 25923) (Fig. 2e). The MIC for ceftobiprole was 2 μg mL−1.

Lower ∑FICmin values indicate greater degrees of synergy, with values closer to 1 indicative of agent additivity (no synergy).

Higher ∑FICmax values indicate greater degrees of antagonism, with values closer to 1 indicative of additivity (no antagonism).

MIC versus ceftobiprole = 0.25 μg mL−1.

Vancomycin demonstrated only weak synergy with ceftobiprole (Fig. 1g; ∑FICmin = 0.6). Ceftobiprole-vancomycin synergy has previously been observed (39), and several clinical studies of β-lactam combinations with vancomycin have been reported and recently reviewed (40). Floxuridine, which demonstrated strong synergy with cefoxitin in a prior study (37), demonstrated effectively no synergy with ceftobiprole (Fig. 1i). Daptomycin also showed effectively no synergy with ceftobiprole in this study (Table 2) but has demonstrated synergy in prior studies (41, 42). Mupirocin demonstrated significant antagonism (∑FICmax = 2.7; ∑FICmin = 1.0). Mupirocin is a topical antibiotic used for skin infections and to clear MRSA from nasal passages (43) that targets isoleucine tRNA synthetase (44). Antagonism of β-lactam activity in S. aureus via modulation of the stringent stress response by mutations or mupirocin has been observed previously (45–47).

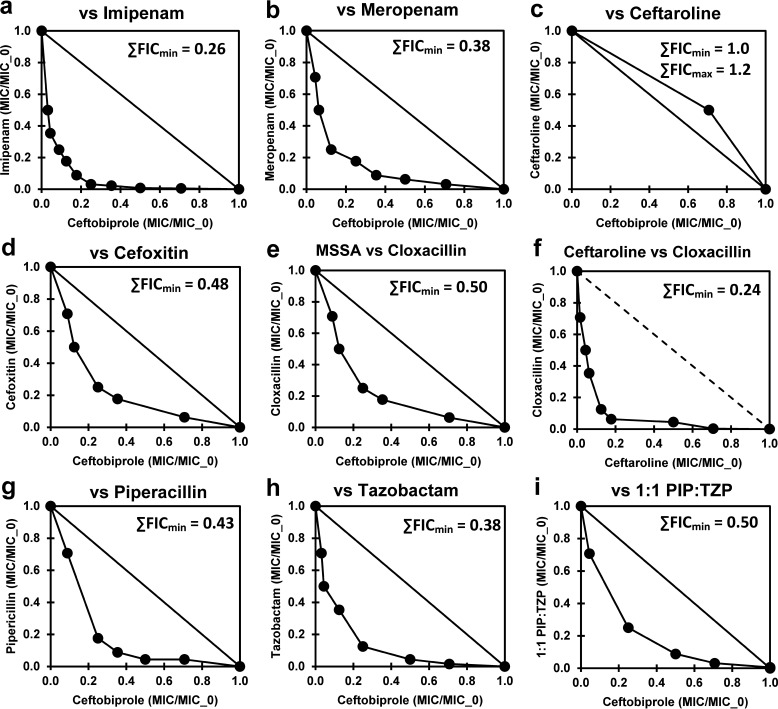

Following these observations, several additional potentially synergistic β-lactams were investigated (Table 2; Fig. 2). Among these, imipenem showed good synergy with ceftobiprole (Fig. 2a, ∑FICmin = 0.26). Ceftobiprole showed no synergy with ceftaroline, its PBP2a-inhibiting cognate (Fig. 2c), perhaps indicative of similar essential PBP selectivity patterns (20, 22). Cefoxitin, which has a much different PBP selectivity pattern (PBP4 selective) than imipenem or cloxacillin (PBP1 selective) (48–50), also demonstrated modest synergy with ceftobiprole. Cloxacillin demonstrated significant but substantially less synergy with ceftobiprole against a methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strain (Table 2, bottom; Fig. 2e). This observation indicates that some of the observed synergy between cloxacillin and ceftobiprole in MRSA is likely due to ceftobiprole interactions with PBPs other than PBP2a. A combination of ceftobiprole with piperacillin-tazobactam has also been reported to show synergy (51). Modest MIC synergy was observed in this study for ceftobiprole with tazobactam and piperacillin, singly and in combination (Table 2; Fig. 2g to i). The isobologram of ceftobiprole with piperacillin was noticeably asymmetric, with low piperacillin concentrations substantially enhancing the ceftobiprole activity (Fig. 2g). A similar asymmetry was also apparent with imipenem (Fig. 2a) and cloxacillin (Fig. 1a.), whereas dicloxacillin seemed to show a reversed asymmetry (Fig. 1e).

FIG 2.

Checkerboard assay results for combinations of ceftobiprole with the additional synergistic agents and MSSA listed in the middle and bottom sections of Table 2. Isobolograms for combinations of ceftobiprole versus imipenem (a), meropenem (b), ceftaroline (c), cefoxitin (d), cloxacillin in MSSA (e), cloxacillin (f), piperacillin (g), tazobactam (h), and a 1:1 (wt/wt) piperacillin (PIP)-tazobactam (TZP) mixture (i). ∑FICmin values are shown in the insets.

It is somewhat tempting to interpret these ceftobiprole synergies in terms of which PBP or PBPs must be targeted to account for the observed effects. However, such a conclusion cannot be reliably deduced from the present information, given that these β-lactams (i) have substantially different selectivities (20, 22, 48, 49, 52, 53); (ii) can all effectively inhibit more than one PBP in S. aureus; and (iii) generally have high intrinsic MICs against MRSA (Table 2), meaning that each agent at their respective MICs will effectively inhibit multiple PBPs. Additional study of the molecular basis of these synergies is required. From a clinical perspective, the good synergies with and low intrinsic MICs of flucloxacillin and dicloxacillin demonstrate that effective combinations of β-lactams with ceftobiprole are possible.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General.

The FDA-approved drug library of 978 compounds was obtained from Selleckchem. Sterile 384-well microtiter plates were purchased from Corning (catalog number 3680), 96-well U-bottom polypropylene storage plates were acquired from Becton, Dickinson (catalog number 351190), and sterile 96-well microtiter plates were obtained from MidSci (catalog number TP92096). Other reagents were purchased from standard sources and were reagent grade or better. The main bacterial strain used in this study was methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain F-182 (ATCC 43300). The methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strain used in this study was Seattle 1945 (ATCC 25923).

MRSA versus FDA −/+ceftobiprole library screen.

The FDA-approved drug library was delivered in columns 1 to 11 in 96-deep well plates, 12 plates total, with each sample well containing 100 μL of a 10-mM solution of a compound dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). A diluted working library at 100 μM in 96-well plates was prepared by serial dilution in DMSO as described previously (37). Two sets of library screening plates were then prepared for the −ceftobiprole and +ceftobiprole screens by transferring 5 μL from the working library plates into the wells of 384-well plates (3 plates in each of two sets) using a Biomek 3000 liquid handling workstation. The plates were frozen at −80°C and dried under a strong vacuum (<50 μmHg) in a Genevac Quattro centrifugal concentrator.

To each well in each set was added 20 μL cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (CAMH) broth containing 4,000 CFU of MRSA (ATCC 43300) and either no ceftobiprole for the −ceftobiprole screens or 0.25 μg mL−1 ceftobiprole (equal to ~1/8× MIC) for the +ceftobiprole screens. These additions were performed using an Integra Viaflo Assist automated multichannel pipettor in a Labconco biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) cabinet. FDA-approved drug library compounds were present at 25 μM in these two plate sets (−ceftobiprole and +ceftobiprole). The plates were incubated for 48 h at 35°C. Fresh CAMH broth (10 μL) was added to the wells of these four sets of plates, followed by incubation for 2 h at 35°C to restart active cell growth. To the wells of these plates was then added 6 μL of 100 μg mL−1 resazurin (sodium salt) (54–56). The plates were incubated for another 2 h at 35°C, and the fluorescence excitation at 570 nm and emission at 600 nm (Ex570/Em600) (Promega Technical Bulletin TB317) of the wells was measured using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 multimode microplate reader. Library screening data were processed and analyzed using Matlab scripts (MathWorks). Based on the values for known active and inactive antibacterial agent controls, a cutoff value between the active and inactive compounds was selected, and lists of active wells in each screening set (−ceftobiprole, +ceftobiprole) were generated. These lists were merged to give a pooled hit list, as described previously (37).

MIC determination.

MICs were determined by hit picking 5-μL samples from the working library plates (100 μM) into the first columns of 384-well plates (two sets, one set for the −ceftobiprole MICs and one for +ceftobiprole MICs). These samples were then serially diluted in steps of two across the plates with DMSO using an Integra Viaflo Assist automated multichannel pipettor. The last column was left blank (DMSO only). These plates were frozen at −80°C and dried under a strong vacuum as described above. To each well in each set was added 20 μL cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton (CAMH) broth containing 4,000 CFU of MRSA (ATCC 43300) and either no ceftobiprole for the –ceftobiprole MICs or 0.25 μg mL−1 ceftobiprole for the +ceftobiprole MICs (the MIC for ceftobiprole was 2 μg mL−1). This provided the MIC plates with 12.5 μM as the highest FDA-tested agent concentration. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 35°C. Fresh CAMH broth (10 μL) was added to the wells of these four sets of plates, followed by incubation for 2 h at 35°C to restart active cell growth. To the wells of these plates was then added 6 μL of 100 μg mL−1 resazurin. The plates were incubated for another 2 h at 35°C, and the Ex570/Em600 fluorescence of the wells was measured as described above. The MICs were determined using a cutoff midway between the known active and inactive samples. All MICs were determined at least in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. The results from these MIC determinations are shown in Table 1.

Checkerboard assays to confirm synergy or antagonism with ceftobiprole.

Several agents demonstrated apparent synergistic activity with ceftobiprole (L2 values of ≥2 in Table 1). Checkerboard assays to confirm synergy (57, 58) were performed using individually purchased compounds in 384-well plates using serial dilution steps of √2 (1.41) in CAMH, starting with a ceftobiprole concentration of 4 μg mL−1 (2× MIC) diluted in the top to bottom dimension and a concentration of the FDA agent starting at 2× to 8× MIC diluted in the left to right dimension. The last row (row 16) and column (column 23) in each dimension had a zero concentration of the respective agent. The last column (column 24) was used as a blank control with no ceftobiprole or FDA test agent. After the dilutions were completed, each well contained ceftobiprole and FDA test agents in 10 μL medium at 2× the experimental concentration. To each well in these plates was then added 10 μL CAMH broth containing 4,000 CFU MRSA, which diluted these agents to 1× their experimental concentrations, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 35°C. Fresh CAMH broth (10 μL) was then added to each well; the plates were incubated at 35°C for 2 h to restart the bacterial metabolism, 6 μL of 100 μg mL−1 resazurin was added, and the plates were incubated for an additional 2 h. The Ex570/Em600 fluorescence of the wells was measured as described above. All checkerboard assays were performed at least in triplicate and the data averaged. Checkerboards were also performed using serial dilutions in DMSO to ensure consistency with the dilutions performed in CAMH, but the dilutions in CAMH gave more precise (less variable) results, likely due to the fewer plate manipulations required for the CAMH dilution experiments.

∑FICmin and ∑FICmax calculations.

Fractional inhibitory values were calculated using the following formula (58–60):

| (2) |

MICA/0 is the MIC of A alone, and MICB/0 is the MIC of B alone. For each data point in an isobologram, MICA/B is the MIC of A in the presence of some (MIC) concentration of B, and MICB/A is the MIC of B in the presence of some (MIC) concentration of A. FICA (the fractional inhibitory concentration of A) corresponds to the fractional MIC for A, and FICB corresponds to the fractional MIC for B. The sum of these values for each individual data point is the ∑FIC, which is at a minimum near the origin of the isobologram. The minimum ∑FIC value over all the isobologram data points is the ∑FICmin. Similarly, the highest value over all the isobologram data points is the ∑FICmax (Table 2). ∑FICmin values of ≤0.5 are indicative of synergy, ∑FICmax values of ≥4 are indicative of antagonism, and values between 0.5 and 4 are indicative of additive effects (57).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge support by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R21-AI121903 and R15-GM126502) to W.G.G.

W.G.G. designed and guided this study. A.D.S. optimized and performed the experimental procedures. Both authors contributed to writing the manuscript. Neither author has any competing interests. Both authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

William G. Gutheil, Email: gutheilw@umkc.edu.

Rosemary C. She, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ventola CL. 2015. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T 40:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. 2019. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Oliveira DMP, Forde BM, Kidd TJ, Harris PNA, Schembri MA, Beatson SA, Paterson DL, Walker MJ. 2020. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 33:e00181-19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00181-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver LL. 2011. Challenges of antibacterial discovery. Clin Microbiol Rev 24:71–109. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00030-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown ED, Wright GD. 2016. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature 529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler MS, Blaskovich MA, Cooper MA. 2017. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline at the end of 2015. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 70:3–24. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santajit S, Indrawattana N. 2016. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Biomed Res Int 2016:2475067. doi: 10.1155/2016/2475067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein EY, Jiang W, Mojica N, Tseng KK, McNeill R, Cosgrove SE, Perl TM. 2019. National costs associated with methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus hospitalizations in the United States, 2010–2014. Clin Infect Dis 68:22–28. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhen X, Lundborg CS, Sun X, Hu X, Dong H. 2019. Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in ESKAPE organisms: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8:137. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0590-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mancuso G, Midiri A, Gerace E, Biondo C. 2021. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: the most critical pathogens. Pathogens 10:1310. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10101310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner NA, Sharma-Kuinkel BK, Maskarinec SA, Eichenberger EM, Shah PP, Carugati M, Holland TL, Fowler VG, Jr.. 2019. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:203–218. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0147-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartman BJ, Tomasz A. 1984. Low-affinity penicillin-binding protein associated with beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol 158:513–516. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.513-516.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shalaby MW, Dokla EME, Serya RAT, Abouzid KAM. 2020. Penicillin binding protein 2a: an overview and a medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur J Med Chem 199:112312. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graves-Woodward K, Pratt RF. 1998. Reaction of soluble penicillin-binding protein 2a of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with beta-lactams and acyclic substrates: kinetics in homogeneous solution. Biochem J 332:755–761. doi: 10.1042/bj3320755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim D, Strynadka NC. 2002. Structural basis for the beta lactam resistance of PBP2a from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Struct Biol 9:870–876. doi: 10.1038/nsb858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh Y-C, Lin Y-C, Huang Y-C. 2016. Vancomycin, teicoplanin, daptomycin, and linezolid MIC creep in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is associated with clonality. Medicine (Baltimore) 95:e5060. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hebeisen P, Heinze-Krauss I, Angehrn P, Hohl P, Page MG, Then RL. 2001. In vitro and in vivo properties of Ro 63-9141, a novel broad-spectrum cephalosporin with activity against methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:825–836. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.825-836.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davies TA, Page MG, Shang W, Andrew T, Kania M, Bush K. 2007. Binding of ceftobiprole and comparators to the penicillin-binding proteins of Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2621–2624. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00029-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sader HS, Fritsche TR, Kaniga K, Ge Y, Jones RN. 2005. Antimicrobial activity and spectrum of PPI-0903M (T-91825), a novel cephalosporin, tested against a worldwide collection of clinical strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:3501–3512. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3501-3512.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moisan H, Pruneau M, Malouin F. 2010. Binding of ceftaroline to penicillin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:713–716. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan LC, Basuino L, Diep B, Hamilton S, Chatterjee SS, Chambers HF. 2015. Ceftobiprole- and ceftaroline-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2960–2963. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05004-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greninger AL, Chatterjee SS, Chan LC, Hamilton SM, Chambers HF, Chiu CY. 2016. Whole-genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to fifth-generation cephalosporins reveals potential non-mecA mechanisms of resistance. PLoS One 11:e0149541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton SM, Alexander JAN, Choo EJ, Basuino L, da Costa TM, Severin A, Chung M, Aedo S, Strynadka NCJ, Tomasz A, Chatterjee SS, Chambers HF. 2017. High-level resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to β-lactam antibiotics mediated by penicillin-binding protein 4 (PBP4). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02727-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02727-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bongiorno D, Mongelli G, Stefani S, Campanile F. 2019. Genotypic analysis of Italian MRSA strains exhibiting low-level ceftaroline and ceftobiprole resistance. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 95:114852. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morroni G, Brenciani A, Brescini L, Fioriti S, Simoni S, Pocognoli A, Mingoia M, Giovanetti E, Barchiesi F, Giacometti A, Cirioni O. 2018. High rate of ceftobiprole resistance among clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a hospital in central Italy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e01663-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01663-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmermann GR, Lehar J, Keith CT. 2007. Multi-target therapeutics: when the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Drug Discov Today 12:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ejim L, Farha MA, Falconer SB, Wildenhain J, Coombes BK, Tyers M, Brown ED, Wright GD. 2011. Combinations of antibiotics and nonantibiotic drugs enhance antimicrobial efficacy. Nat Chem Biol 7:348–350. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu X, Xu L, Yuan G, Wang Y, Qu Y, Zhou M. 2018. Synergistic combination of two antimicrobial agents closing each other's mutant selection windows to prevent antimicrobial resistance. Sci Rep 8:7237. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25714-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyers M, Wright GD. 2019. Drug combinations: a strategy to extend the life of antibiotics in the 21st century. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:141–155. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roemhild R, Bollenbach T, Andersson DI. 2022. The physiology and genetics of bacterial responses to antibiotic combinations. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:478–490. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00700-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farha MA, Brown ED. 2010. Chemical probes of Escherichia coli uncovered through chemical-chemical interaction profiling with compounds of known biological activity. Chem Biol 17:852–862. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farha MA, Czarny TL, Myers CL, Worrall LJ, French S, Conrady DG, Wang Y, Oldfield E, Strynadka NC, Brown ED. 2015. Antagonism screen for inhibitors of bacterial cell wall biogenesis uncovers an inhibitor of undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:11048–11053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511751112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farha MA, Brown ED. 2015. Unconventional screening approaches for antibiotic discovery. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1354:54–66. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hind CK, Dowson CG, Sutton JM, Jackson T, Clifford M, Garner RC, Czaplewski L. 2019. Evaluation of a library of FDA-approved drugs for their ability to potentiate antibiotics against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00769-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00769-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayon NJ, Gutheil WG. 2019. Dimensionally enhanced antibacterial library screening. ACS Chem Biol 14:2887–2894. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.9b00745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosdahl VT, Frimodt-Møller N, Bentzon MW. 1989. Resistance to dicloxacillin, methicillin and oxacillin in methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus detected by dilution and diffusion methods. APMIS 97:715–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1989.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandez J, Abbanat D, Shang W, He W, Amsler K, Hastings J, Queenan AM, Melton JL, Barron AM, Flamm RK, Lynch AS. 2012. Synergistic activity of ceftobiprole and vancomycin in a rat model of infective endocarditis caused by methicillin-resistant and glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1476–1484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06057-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.García Aragonés L, Blanch Sancho JJ, Segura Luque JC, Mateos Rodriguez F, Martínez Alfaro E, Solís García Del Pozo J. 2022. What do beta-lactams add to vancomycin or daptomycin in the treatment of patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia? A review. Postgrad Med J 98:48–56. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhand A, Bayer AS, Pogliano J, Yang S-J, Bolaris M, Nizet V, Wang G, Sakoulas G. 2011. Use of antistaphylococcal beta-lactams to increase daptomycin activity in eradicating persistent bacteremia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: role of enhanced daptomycin binding. Clin Infect Dis 53:158–163. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barber KE, Werth BJ, Ireland CE, Stone NE, Nonejuie P, Sakoulas G, Pogliano J, Rybak MJ. 2014. Potent synergy of ceftobiprole plus daptomycin against multiple strains of Staphylococcus aureus with various resistance phenotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:3006–3010. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tucaliuc A, Blaga AC, Galaction AI, Cascaval D. 2019. Mupirocin: applications and production. Biotechnol Lett 41:495–502. doi: 10.1007/s10529-019-02670-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes J, Mellows G. 1978. Inhibition of isoleucyl-transfer ribonucleic acid synthetase in Escherichia coli by pseudomonic acid. Biochem J 176:305–318. doi: 10.1042/bj1760305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aedo S, Tomasz A. 2016. Role of the stringent stress response in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2311–2317. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02697-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim CK, Milheiriço C, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. 2017. Antibiotic resistance as a stress response: recovery of high-level oxacillin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus “auxiliary” (fem) mutants by induction of the stringent stress response. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00313-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00313-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhawini A, Pandey P, Dubey AP, Zehra A, Nath G, Mishra MN. 2019. RelQ mediates the expression of β-lactam resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol 10:339. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chambers HF, Sachdeva M. 1990. Binding of beta-lactam antibiotics to penicillin-binding proteins in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 161:1170–1176. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.6.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okonog K, Noji Y, Nakao M, Imada A. 1995. The possible physiological roles of penicillin-binding proteins of methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Chemother 1:50–58. doi: 10.1007/BF02347729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Banerjee R, Fernandez MG, Enthaler N, Graml C, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Patel R. 2013. Combinations of cefoxitin plus other β-lactams are synergistic in vitro against community associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 32:827–833. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Campanile F, Bongiorno D, Mongelli G, Zanghì G, Stefani S. 2019. Bactericidal activity of ceftobiprole combined with different antibiotics against selected Gram-positive isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 93:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Georgopapadakou NH, Dix BA, Mauriz YR. 1986. Possible physiological functions of penicillin-binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 29:333–336. doi: 10.1128/AAC.29.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y, Bhachech N, Bush K. 1995. Biochemical comparison of imipenem, meropenem and biapenem: permeability, binding to penicillin-binding proteins, and stability to hydrolysis by beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother 35:75–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baker CN, Tenover FC. 1996. Evaluation of Alamar colorimetric broth microdilution susceptibility testing method for staphylococci and enterococci. J Clin Microbiol 34:2654–2659. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2654-2659.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rampersad SN. 2012. Multiple applications of Alamar blue as an indicator of metabolic function and cellular health in cell viability bioassays. Sensors (Basel) 12:12347–12360. doi: 10.3390/s120912347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyc O, Tomás-Menor L, Garbeva P, Barrajón-Catalán E, Micol V. 2016. Validation of the alamarBlue assay as a fast screening method to determine the antimicrobial activity of botanical extracts. PLoS One 11:e0169090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Odds FC. 2003. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:1. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pillai SK, Moellering RCJ, Eliopoulos GM. 2005. Antimicrobial combinations, p 365–440. In Lorian V (ed), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Wolters Kluwer Health, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Elion GB, Singer S, Hitchings GH. 1954. Antagonists of nucleic acid derivatives. VIII. Synergism in combinations of biochemically related antimetabolites. J Biol Chem 208:477–488. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)65573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hallander HO, Dornbusch K, Gezelius L, Jacobson K, Karlsson I. 1982. Synergism between aminoglycosides and cephalosporins with antipseudomonal activity: interaction index and killing curve method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 22:743–752. doi: 10.1128/AAC.22.5.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]