Abstract

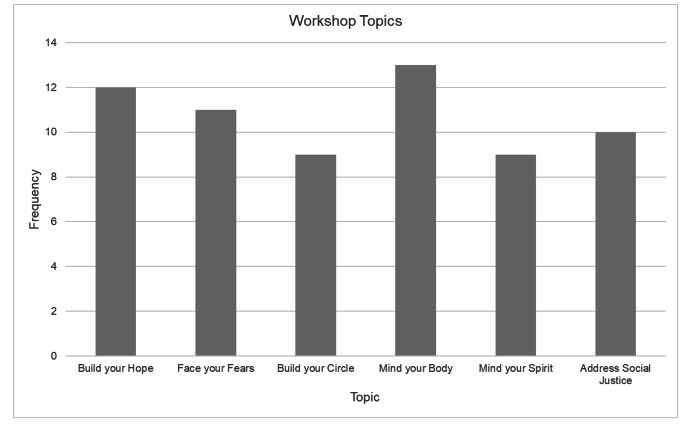

The COVID-19 pandemic brought widespread and notable effects to the physical and mental health of communities across New York City with disproportionate suffering Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino communities alongside additional stressors such as racism and economic hardship. This report describes the adaptation of a previously successful evidence-based community engagement health education program for the deployment of resilience promoting workshop program in faith-based organizations in BIPOC communities in New York City. From June 2021 to June 2022, nine faith-based organizations implemented 58 workshops to 1,101 non-unique workshop participants. Most of the workshops were delivered online with more women (N = 803) than men (N = 298) participating. All organizations completed the full curriculum; the workshop focused on self-care and physical fitness was repeated most frequently (N = 13). Participants in the workshops ranged from 4 to 73 per meeting and were largely female. The Building Community Resilience Project is an easy and effective way to modify an existing, evidence-based community health education program to address new and relevant health needs such as resilience and stress amidst the COVID-19 pandemic among faith communities serving BIPOC populations. More research is needed regarding the impact of the workshops as well as adaptability for other faith traditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10900-023-01193-w.

Keywords: Faith-based organizations, Resilience, Under-resourced communities, Community engagement

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to all communities throughout the world. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the physical and mental health disparities that many members of marginalized communities already experienced [1–4]. Illness and mortality statistics from states throughout the U.S. show that members of racial and ethnic minority groups were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 [5]. Public and mental health experts suggested that clinical practitioners prioritize and address the mental health ramification of the COVID-19 pandemic when working with communities that are more vulnerable to COVID-19-related stressors [2, 3].

The physical and social distancing guidelines imposed to slow the spread of COVID-19 also disrupted the daily routines and social networks that many people rely on to navigate crises. Members of marginalized groups may have experienced additional pandemic-related stressors, including race-based discrimination and economic hardship, and it is likely that members of these groups may have experienced increased feelings of anxiety about the potential that they or their loved ones could contract COVID-19 [2].

Having a religious or spiritual practice can be a protective factor against negative physical and mental health outcomes, even after a potentially traumatic experience. For example, studies have found that having a regular religious or spiritual practice is associated with lower all-cause mortality, a lower risk for developing depression, and a lower risk for suicidality [6, 7]. Research has also shown that engaging in religious and/or spiritual practices can help promote resilience after experiencing a potentially traumatic event [8].

Churches and other faith-based organizations are an accessible and effective setting to deliver health-promoting programs, and many churches have long been essential community-based partners for delivering health and wellness programs to communities that are in high need of support, are harder to reach, or historically distrust various healthcare channels [9–11]. Churches that serve Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino communities have historically been sites that host programs to reduce health disparities [12–14]. Additionally, access to a social support network, like the network offered by many religious congregations, can foster one’s resilience [15].

In response to the growing need to support communities who were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 and the changing needs of these communities due to the pandemic, the Center for Stress, Resilience, and Personal Growth at Mount Sinai (CSRPG), a program developed during the height of the pandemic in 2020 to address stress-related and mental health needs of hospital staff, developed a community-based resilience training program called the Building Community Resilience Project (BCRP) to provide spiritually grounded psychoeducation and resilience training to church congregations.

Method

BCRP built upon two successful initiatives within the Mount Sinai Health System (MSHS). First, as has been described elsewhere [16, 17], CSRPG developed and implemented workshops focused on building resilience in June 2020 to support the psychosocial needs of the system’s health care workers. Content for these resilience workshops was adapted from Southwick and Charney’s work on research-supported factors that support human resilience [8, 18]. Mirroring this curriculum, BCRP content addressed five factors: (1) realistic optimism (“Build Your Hope”); (2) active coping and facing fears (“Face Your Fears”); (3) self-care (“Mind Your Body”); (4) social support (“Mind Your Circle”); and (5) embracing faith and spirituality (“Mind Your Spirit”). For this program, a sixth module, “Address Social Justice” was added in consideration of the nationwide attention to racial inequity advanced by the Black Lives Matter movement starting in 2020, and health care disparities in service delivery and outcomes that were apparent to our communities during the initial waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. BCRP also builds on our prior success educating community health advisors to provide medical and mental health-oriented workshops to congregants in faith-and community-based organizations. This program, Multi-Faith Initiative on Community and Health (M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL™) has been ongoing since 2017 [19, 20]. Like M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL™, the BCRP trained Community Health Advisors (CHAs), members and leaders of the congregations and faith-based communities to deliver workshop content.

Recruitment and Implementation

Congregations and faith-based organizations already participating in M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL™ were invited to participate in the BCRP. In total 10 faith-based organizations who are engaged in M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL™ agreed to participate. The congregations involved in the BCRP are primarily Christian churches that serve African American and Hispanic LatinX communities throughout Harlem and the Bronx, New York. Like MICAH Project HEAL, the participating organizations received financial compensation for every workshop they completed; and had a modest stipend to purchase any equipment they needed to deliver the workshops. Additionally, organizations that facilitated all six workshops in the BCRP series were given a bonus payment and a completion certificate.

CHAs were trained to deliver the workshops over three meetings totaling 5.5 h. Training was led by a psychologist (JD), psychiatrist (DM), masters-level research coordinator (SS), and doctoral-level health care chaplain (ZC). In addition to reviewing the context, and opportunities to practice teaching, CHAs received specific training in how to handle challenging situations that may arise in a group meeting involving mental health topics. In total, 35 CHAs were trained from eight faith-based organizations and one community-based organization, with 2–8 CHAs trained per organization. CHAs had to complete all training meetings to be able to deliver the workshops. CHAs were provided with a standardized slide deck and facilitator manual containing the workshop curriculum. The manual included standardized text meant to be read out loud and follow-up prompts that could be used to further discussion. The general structure of each workshop comprised a Bible passage, quotes from secular authors, a brief lay description of the scientific evidence supporting each resilience factor, and then a discussion of practices shown to support resilience. Consistent with MICAH Project HEAL, congregations were also invited to open and close meetings with prayer. Additionally, CHAs were given a pre/post learning outcome survey at the beginning of the first training session and the end of the last training session, using Zoom’s polling feature. The pre/post learning outcome survey included 12 statements about the resilience factors covered in the BCRP curriculum (e.g., “How people think about the challenges they face in their lives can impact how they feel.” and “Having friends or family to rely on during stressful times may impact one’s resilience.”), and respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

Workshops were designed to be delivered virtually via Zoom as well as in-person if social distancing regulations allowed [21]. Prior studies have shown successful implementation of modules and training delivered through a virtual format, including the M.I.C.A.H. Project Heal™ [21]. A Mount Sinai staff member attended workshops to provide support to the CHAs.

Following the workshop, each CHA completed a form providing basic information about the meeting, which is described below. These data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai [22, 23]. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

Results

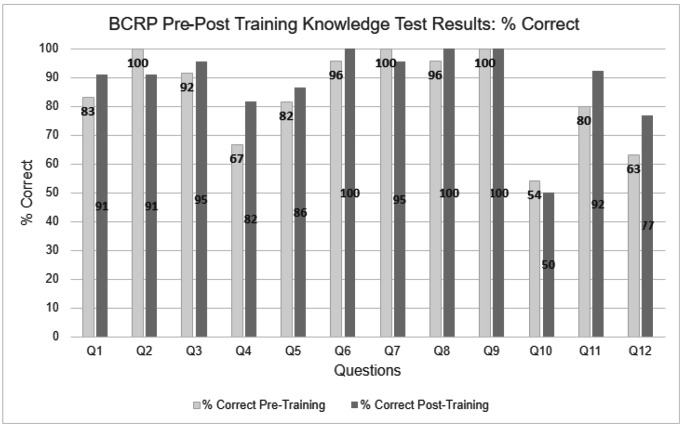

The pre/post learning outcome survey highlighted important changes in CHAs understanding of resilience after learning the BCRP curriculum. Overall, CHAs had better knowledge about facets of resilience after the training. Specifically, there was a 15% increase in knowledge that people who identify as religious manage stress better than those who do not and a 14% increase in knowledge that spirituality does not only refer to believing in God. There was also a 12% increase in knowledge that having a strong role model helps people to manage stress (see Fig. 1). Information regarding the workshops was derived from REDCap records completed by CHAs after each workshop. Overall, 9 faith-based and community organizations completed 58 workshops from June 2021 to June 2022. Over 90% of workshops began with an opening prayer and all workshops ended with a closing prayer. Most workshops were delivered through an online format with approximately 75% of the workshops delivered virtually via Zoom, 9% in person, and 16% in a hybrid format. Approximately 70% of workshops were delivered in the evening and lasted just over an hour (M = 66; SD = 23.54). The vast majority (94.7%) of workshops were delivered in English, but 3 workshops were delivered in English and Spanish. The workshops had an average of 18 participants per session, with a range of 4–73 participants. There were 1,101 non-unique workshop participants with a greater number of women (N = 803) than men (N = 298) in attendance.

Fig. 1.

Number of Workshops Delivered by Topic

All faith-based organizations completed the 6 workshop session topics at least once, and one faith-based organization repeated four of the workshop topics. The number of conducted workshop sessions by topic can be found in Fig. 2. The majority (N = 39) of workshops were facilitated by more than one CHA.

Fig. 2.

BCRP Pre-Post Training Knowledge Test Results

Note. Q1 = People cannot be taught to be more resilient. Q2 = How people think about the challenges they face in their lives can impact how they feel. Q3 = Injustices including racism can negatively impact resilience. Q4 = Research shows that people who identify as religious manage stress better than those who do not. Q5 = Realistic optimism means denying all the negative or unpleasant things that are happening in your life. Q6 = Having friends or family to rely on during stressful times may impact one’s resilience. Q7 = All communities have the same resources to build resilience in tough times. Q8 = The best way to deal with something you fear is to avoid it. Q9 = If people have lost interest in hobbies or things they used to enjoy, its best to not even try to do them again. Q10 = Accepting that things are out of your control is not a helpful strategy in managing stress. Q11 = Having strong role models does not really make much of a difference in how people manage stress. Q12 = Spirituality refers only to believing in God

Discussion

The Building Community Resilience Project (BCRP) was developed to address new and relevant health needs of BIPOC communities during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic in the New York Metro area. The BCRP curriculum focused on factors that have been empirically supported to foster psychological resilience. Using the M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL™ model for curriculum delivery and community partnership, the BCRP uniquely delivered well-being and resilience-focused psychoeducation to faith- and community-based organizations using a train-the-trainer model. To our knowledge, the BCRP initiative is one of the first resilience-focused initiatives developed specifically for faith-based organizations using lay trained personnel as program facilitators. Implementation relied both on internal expertise on psychological resilience and pre-existing trusted relationships with faith and community-based organizations, established prior to the COVID-19 pandemic by the MSHS M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL™ team. Due to these factors, the MSHS BCRP team was able to develop and deploy the BCRP initiative relatively quickly and at a low cost. Additionally, the faith- and community-based organizations that participated in BCRP were enthusiastic partners in the initiative, which contributed to the program’s success.

Given the historical atrocities, current health disparities, and medical mistrust within BIPOC communities, providing culturally congruent messaging and developing a trusting relationship is critical to successful public health initiatives [9]. This initiative builds upon the understanding that church-partnered interventions have a significant impact on the health of African American and Hispanic/Latino communities [10, 20] due to the incorporation of spiritual and cultural contextualization and the trusted relationships between the CHAs and the community, among other features [10, 20]. Specifically, health interventions have been found to be successful in increasing smoking cessation [24], mammography [25], weight-loss [26], and healthy eating [27, 28]. Churches are invested in the health of the congregation and are active partners in health-focused initiatives.

Mental health initiatives with CHAs have also been impactful, although less often present in church settings. Barnett and colleagues [29] conducted a systematic review of efforts incorporating CHAs in mental health interventions. This review found that CHA-delivered interventions contributed to improved mental health outcomes across a range of concerns (e.g., depression, trauma, anxiety, substance use, etc.) and is a promising avenue through which mental health disparities can be targeted. Further, the methods outlined in this report is consistent with prominent implementation supports in the literature [29]. The training protocol ranged three meetings, including didactics and role-playing, and included supervision in the form of live observation. The BCRP has the potential to compound the effectiveness of such interventions given the consistency with previous works and additional incorporation of faith into the intervention itself.

Future Directions

While anecdotal feedback from participating faith leaders spoke to the effectiveness and positive impact of the BCRP on the participants involved, further studies are needed to determine the overall effectiveness of the curriculum and retention of the skills and concepts learned in the workshops for attendees and CHAs. Future studies could examine the use of various resilience strategies before and after intervention. The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) may be used to examine self-evaluation of changes in resilience traits before and after the intervention [30]. Alternatively, emerging measures, such as the Mount Sinai Resilience Rating Scale (MSRS) can be used to document changes in different types of resilience [31]; this scale examines emotions, thoughts, and behaviors linked to resilience across seven domains. Such an examination would allow for important information regarding what facets of resilience are best targeted by this intervention and the overall effect on behavioral changes. Regarding long-term effects, studies may wish to examine the effects of the BCRP in protecting participants from psychological distress following economic hardship, discrimination, or major pandemic related difficulties.

In addition, future initiatives may consider incorporating linkage to care and examining the effects of the BCRP on treatment engagement. Hankerson and colleagues [32] have added connections with mental health professionals to their church-partnered programs to create a bridge between community resources and professional mental health treatment. This bridge is purported to overcome barriers caused by stigma and increase access to care [32]. Overcoming stigma through connecting participants with care through a CHA may greatly benefit underserved communities, given help-seeking stigma is a major barrier to mental health treatment and a driver of population health inequities [33].

With respect to reach the BCRP was deployed in primarily Christian churches and has not yet been utilized in other faith communities. More research and adaptations to the curriculum are needed in order to assess the program’s impact on non-Christian faith traditions. One study implementing a community health program across faith settings used the Ecological Validity Model to adapt their intervention to each faith-based organization by making changes based on language, engaged persons, use of metaphors, integrating salient values into content and goals, and adapting program activities [34]. A similar approach may be taken in partnership with non-Christian faith leaders to create a BCRP that is culturally relevant and congruent. Further, Jewish and Muslim communities specifically report more frequent experiences marginalization and discrimination [35], and are more often victims of religion-motivated hate crimes [36]. The BCRP may help to further strengthen individual resilience in the face of discrimination.

Overall, the BCRP appears to be an easy, effective model to potentially promote resilience and well-being in resource-limited settings among faith communities serving BIPOC populations. This model is especially effective when previous, trusted partnerships with faith communities already exist. The BCRP model can be incorporated into a range of faith settings and is a sustainable intervention which can be maintained by the faith organization itself.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author’s Contributions

Study conception, design, and data collection were performed by M.G., S.S., D.M., Z.C., J.D. Data analysis was performed by M.G. and S.S. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation and read and reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Robin Hood COVID-19 Relief Fund.

Availability of Data and Material

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

J.D. receives book royalties from Cambridge University Press. The remaining authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in the study followed the ethical standards of the institutional research board of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (STUDY# 21–00356 and STUDY# 22-01082).

Consent to Participate

The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Program for Protection of Human Subjects approved a waiver of consent. Participants who completed surveys were provided with an information sheet describing the purpose of the research and expectations of participation.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. In the information sheet provided to participants, they were informed that their identity would be protected through removal of identifying information in data storage and in publication.

Financial Interests

D.M and J.D. are partially supported by HRSA grant (U3NHP45398); J.D. also is supported by NIH/NCATS grant (1UL1TR004419-01).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gauthier GR, Smith JA, García C, Garcia MA, Thomas PA. Exacerbating inequalities: Social networks, racial/ethnic disparities, and the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2021;76(3):e88–e92. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lund EM. Even more to handle: additional sources of stress and trauma for clients from marginalized racial and ethnic groups in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2020;34(3–4):321–330. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2020.1766420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loeb TB, Ebor MT, Smith AM, et al. How mental health professionals can address disparities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Traumatology. 2021;27(1):60–69. doi: 10.1037/trm0000292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novacek DM, Hampton-Anderson JN, Ebor MT, Loeb TB, Wyatt GE. Mental health ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Black Americans: clinical and research recommendations. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy. 2020;12(5):449–451. doi: 10.1037/tra0000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcendor DJ. Racial disparities-associated COVID-19 mortality among minority populations in the US. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(8):2442. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh HK, Coles E. Body and soul: Health collaborations with faith-based organizations. American Journal of Public Health. 2019;109(3):369–370. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA, Koh HK. Health and spirituality. Journal Of The American Medical Association. 2017;318(6):519–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.8136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (2018). Resilience: the science of mastering life’s greatest challenges (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- 9.Bajaj SS, Stanford FC. Beyond Tuskegee - Vaccine distrust and everyday racism. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(5):e12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMpv2035827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, Blakeney N, Paxton A, Baskin M. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28(1):213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eng E, Hatch J, Callan A. Institutionalizing social support through the church and into the community. Health Education Quarterly. 1985;12(1):81–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818501200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braithwaite, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Treadwell, H. M. (2009). Health issues in the black community. John Wiley & Sons.

- 13.Lincoln, C. E., & Mamiya, L. H. (1990). The black church in the african american experience. Duke University Press.

- 14.Welsh, A. L., Sauaia, A., Jacobellis, J., Min, S., & Byers, T. (2005). The effect of two church-based interventions on breast cancer screening rates among Medicaid-insured Latinas.Preventing Chronic Disease, 2(4). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1435704/ [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Rodriguez-Llanes JM, Vos F, Guha-Sapir D. Measuring psychological resilience to disasters: are evidence-based indicators an achievable goal? Environmental Health. 2013;12(1):115. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DePierro J, Katz CL, Marin D, et al. Mount Sinai’s Center for stress, resilience and personal growth as a model for responding to the impact of COVID-19 on health care workers. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293:113426. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DePierro J, Marin DB, Sharma V, et al. Developments in the first year of a resilience-focused program for health care workers. Psychiatry Research. 2021;306:114280. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience for frontline health care workers: evidence-based recommendations. The American Journal of Medicine. 2021;134(7):829–830. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marin DB, Costello Z, Sharma V, Knott CL, Lam D, Jandorf L. Adapting Health through Early Awareness and Learning Program into a new faith-based organization context. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2019;13(3):321–329. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2019.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marin DB, Karol AB, Sharma V, Project H. Sustainability of a faith-based community health advisor training program in urban underserved communities in the USA. J Relig Health. 2022;61(3):2527–2538. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01453-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holt CL, Tagai EK, Scheirer MA, et al. Translating evidence-based interventions for implementation: experiences from Project HEAL in African American churches. Implementation Science. 2014;9(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal Of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. Journal Of Biomedical Informatics. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voorhees CC, Stillman FA, Swank RT, Heagerty PJ, Levine DM, Becker DM. Heart, body, and soul: impact of church-based smoking cessation interventions on readiness to quit. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25(3):277–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Stotts RC, Hollenberg JA. Increasing mammography practice by african american women. Cancer Practice. 1999;7(2):78–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1999.07204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNabb W, Quinn M, Kerver J, Cook S, Karrison T. The PATHWAYS church-based weight loss program for urban african-american women at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(10):1518–1523. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1390–1396. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resnicow K, Campbell M, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, Rahotep S, Doyle C, Williams A, Stables G. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through african-american churches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnett ML, Gonzalez A, Miranda J, Chavira DA, Lau AS. Mobilizing Community Health Workers to address Mental Health Disparities for Underserved populations: a systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2018;45(2):195–211. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0815-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC) Depression and Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DePierro, J., Marin, D. B., Sharma, V., et al. (2022). Development and initial validation of the Mount Sinai Resilience Scale (MSRS) [Manuscript in preparation]. Department of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

- 32.Hankerson SH, Shelton R, Weissman M, et al. Study protocol for comparing screening, brief intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) to referral as usual for depression in african american churches. Trials. 2022;23(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05767-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal Of Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwon SC, Patel S, Choy C, et al. Implementing health promotion activities using community-engaged approaches in asian american faith-based organizations in New York City and New Jersey. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(3):444–466. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheitle, C. P., & Howard Ecklund, E. (2020). Individuals’ experiences with religious hostility, discrimination, and violence: Findings from a new national survey. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6. 10.1177/2378023120967815

- 36.Federal Bureau of Investigation (2020). Hate crime statistics, 2019. https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2019/topic-pages/tables/table-1.xls

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.