Abstract

Background

Prior research has solely focused on the association between handgrip strength and risk of depression in single countries or general populations, but more knowledge is required from wider-spread cohorts and target populations.

Aims

This study aimed to investigate the association between handgrip strength and risk of depression using repeated measures in adults aged 50 years and over.

Method

Data on handgrip strength and risk of depression were retrieved from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) waves 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7, using a hand dynamometer (Smedley, S Dynamometer, TTM) and the EURO-D 12-item scale, respectively. Time-varying exposure and covariates were modelled using both Cox regression and restricted cubic splines.

Results

A total of 115 601 participants (mean age 64.3 years (s.d. = 9.9), 54.3% women) were followed-up for a median of 7.3 years (interquartile range: 3.9–11.8) and 792 459 person-years. During this period, 30 208 (26.1%) participants experienced a risk of depression. When modelled as a continuous variable, we observed an inverse significant association for each kg increase of handgrip strength and depression up to 40 kg in men and up to 27 kg in women.

Conclusions

Being physically strong may serve as a preventive factor for depression in older adults, but this is limited up to a maximum specific threshold for men and women.

Keywords: Muscle, mental disorder, epidemiology, prevention, burden of disease

Background

Depression is considered a contemporary chronic condition that can impair normal mental and physical functioning; the manifestation of depression varies among individuals, but often involves lack of energy, low mood, sadness, insomnia and an inability to enjoy life.1 The incidence of depression disorders increased by 50% over the period from 1990 to 2017 worldwide, and the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the prevalence of depression compared with pre-pandemic levels.2,3

Importantly, depression has been observed to increase the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged and older adults.4,5 It has also been associated with significantly increased risks for hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, physical impairment and suicidal attempts, and is one of the leading causes of global disease burden in terms of disability-adjusted life-years, years lived with disability and years of life lost.6,7 Thus, because depression represents a major public health concern, studies aiming at examining preventive factors to tackle the increase in depression are required. In fact, early prevention is estimated to reduce 20% to 25% incident depression in high-income countries, which warrants the implementation of preventive measures.8

In this regard, there is a growing body of research examining the association between muscle strength, using handgrip as an estimator, and depression in healthy middle-aged and older adults.9,10 Handgrip strength is an easy-to-use, fast and reliable indicator of both sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle mass) and dynapenia (age-related loss of muscle strength). As both have been associated with depression, the plausibility of a regulatory role of skeletal muscle on brain function affecting this condition exists.11–14 Interestingly, exercise also seems to play a key role in the aforementioned relationships, as it can improve muscle strength and muscle mass, downregulates systemic inflammation and improves neuroplasticity, neuroendocrine and oxidative stress responses.15–17 Furthermore, handgrip strength has also been observed as a more useful single marker of frailty (a clinical syndrome in older adults characterised by an increased risk for poor health outcomes such as falls, disability, hospital admissions and mortality) for older people of similar age than using chronological age alone.18

Aims

Nevertheless, study designs of previous evidence rely on either cross-sectional or prospective cohort studies (i.e. one-single base level of handgrip strength) mostly focused on a specific country, and not accounting for time-varying changes of both handgrip strength and relevant covariates.10,19–21 Furthermore, there is mixed evidence on the extent to which handgrip strength levels may associate with lower risk of depression, with study results ranging from weak to strong associations.9,21,22 Thus, higher-quality research with representative samples from different countries is required to better clarify the strength of such an association and to confirm directionality. Therefore, to circumvent limitations from prior research, we aimed to investigate the association between levels of handgrip strength and risk of depression among a large and representative sample of adults from 24 countries using repeated measures.

Method

Study design and population

The present study included data from waves 1, 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a survey recruiting individuals aged 50 years or older residing in European countries and Israel using a panel methodology.23,24 Wave 3 was discarded because it did not include data on handgrip strength.

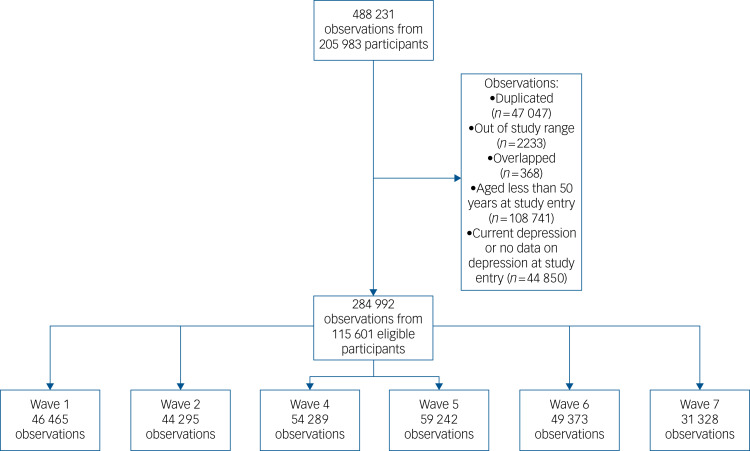

SHARE uses a multistage stratified sampling design in which involved countries are divided into different strata in relation to geographical area, and municipalities or zip codes within these strata served as primary sampling units.25 Data collection for each SHARE wave was carried out biannually through home computer-assisted personal interviews from February 2004 to January 2019. SHARE uses ex-ante harmonised interviews, and new respondents were added in each wave to compensate for losses.25 Only participants aged 50 years and over at study entry with no depression at study entry were included in the present study (n = 115 601). Figure 1 shows more descriptive details of the study sample.

Fig. 1.

Study profile.

The present study was reported according to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).26 The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of Research in Humans of the University of Valencia (registered code 1510464). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Handgrip strength (exposure)

Using a handheld dynamometer (Smedley, S Dynamometer, TTM, Tokio, 100 kg), each hand was measured two times by trained interviewers. Participants were instructed to set their elbow in a 90° angle flexion while either standing or sitting, with a neutral wrist position, and upper arm set vertically against the trunk. Trained interviewers provided standardised instructions to squeeze the dynamometer with maximum effort for 2 s. Handgrip strength was considered as the maximum value of either hand. To account for gender differences and meaningful results, handgrip strength was categorised into gender-stratified tertiles. Additional analyses also accounted for handgrip strength as a continuous variable.

Risk of depression (outcome)

Participants were followed throughout the study period to determine whether they were at risk of depression using the EURO-D 12-item scale. Both description and validation of the scale have been described previously.27 For the purpose of this study, we used an optimal cut-off point of ≥4 depression symptoms, which has been identified as a clinically significant case of depression.27,28

Covariates

Based on a literature review on the topic,29,30 we explored potential causal and confounding pathways between handgrip strength and risk of depression using a directed acyclic graph (Supplementary Figure 1; available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.178). Self-reported gender, age, education, country, body mass index, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol consumption, status regarding whether living with a partner, wave of inclusion, chronic diseases, prescribed drugs consumption, and fruits and vegetables consumption were identified as potential confounders.

Education was self-reported by participants and thereafter coded using the 1997 version of the International Standard Classification of Education.

Body mass index was calculated from self-reported height and weight and grouped into four categories according to standards proposed by the World Health Organization.

Physical inactivity was assessed through two questions: ‘How often do you engage in vigorous physical activity such as sports, heavy housework, or a job that involves physical labour’, and ‘How often do you engage in activities that require a moderate level of energy such as gardening, cleaning the car or going for a walk?’. Participants selecting the option of ‘Hardly ever, or never’ to the two questions were considered physically inactive.

Smoking habits were assessed through the question ‘Have you ever smoked cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos or a pipe daily for a period of at least 1 year?’, whereas alcohol consumption was estimated through the following question: ‘How many days a week did you consume alcohol during the last 6 months?’, and answers comprised the following possible options: ‘Almost every day’, ‘Five or six days a week’, ‘Three or four days a week’, ‘Once or twice a week’, ‘Once or twice a month’, ‘Less than once a month’, ‘Not at all in the last 6 months’, ‘Refusal to answer’, or ‘Don't know’.

Living with a partner was estimated through asking if the surveyed individual was living with any partner/spouse and responses included ‘yes’, ‘no, or ‘refused’ as options.

The number of chronic diseases was provided by the surveyed individuals from a list comprising 14 common chronic diseases.

Drug consumption (i.e. medicines for treating chronic conditions) was assessed through the following question: ‘Do you currently use drugs at least once a week for problems mentioned on this card?’ This variable was re-coded into the categories ‘None’ for those who answered such option in the survey, and ‘Any’ for those who took one or more of a list of drugs.

Fruits and vegetables consumption were measured using a scale of 1 (less than once a week) to 5 (every day).

Details on these covariates are provided elsewhere.25

Statistical analyses

We conducted all statistical analyses with Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, Texas, USA). We used Cox regression to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) for first experienced risk of depression within the examined period using repeated measures of handgrip strength. Months from study entry were set as the timescale and the follow-up continued until either a first depression onset or the end of follow-up occurred. Two models were tested: a model with both gender and age at the time of the interview as time-invariant confounders (model A) and a fully adjusted model (model B) including model A confounders along with other time-invariant confounders (age at the time of interview, gender, country, wave of inclusion, and education) and time-variant confounders (body mass index, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol consumption, living with a partner, wave, chronic diseases, prescribed drugs consumption and fruits and vegetables consumption).

Imputations for missing values (24.7%) were calculated using multiple imputation including the outcome as well as all the covariates without missing values in the equation. After assessing interactions between handgrip strength and all the covariates, no significant interaction was detected. All the analyses were weighted according to each country population (Supplementary Table 1). We provided the results using random forest plots. Additionally, we assessed the dose–response associations of handgrip strength (modelled as a continuous exposure) with depression using restricted cubic splines to allow for potential non-linearity; we trimmed observations less than 5% and greater than 95% of the distribution and pre-specified knots placed at the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 95th percentiles of the exposure distribution.

Departure from linearity was checked with a Wald test assessing the null hypothesis that the coefficient of the fifth spline was equal to zero. We assumed linearity for values below the 5th percentile and for values above the 95th percentile. Multiple imputation of missing values was conducted using a chained equation including all the covariates and the outcome variable. We assumed that data were missing at random. Overall, we imputed five data-sets using the Stata native command (mi impute). No auxiliary variables were used for this purpose.

Results of the study are reported as HRs with 95% CIs and levels of significance were set at P < 0.05.

Sensitivity analyses

To check the robustness of the estimates, we conducted complete-case analyses (Supplementary Figure 2). Moreover, to minimise the potential influence of reverse causality, we conducted analyses excluding participants who experienced depression within 2 years of follow-up (Supplementary Figure 3). Finally, we additionally accounted for mortality and attrition as competing risk in our estimations through Fine–Gray models (Supplementary Figure 4). We also accounted for the Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimate for the survival time in the imputation model (Supplementary Figure 5).31

Results

Demographics

The final sample included 115 601 participants with a mean age of 64.3 (s.d. = 9.9) years at study entry (Table 1) of which 54.3% were women. During a median of 7.3 years of follow-up (interquartile range, 3.9–11.8) and 792 459 person-years, 30 208 (26.1%) participants experienced a risk of depression.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants at study entry (n = 115 601)a

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (s.d.) | 64.3 (9.9) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Men | 52 858 (45.7) |

| Women | 62 743 (54.3) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, n (%) | |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 1239 (1.1) |

| Normal (18.5–<25 kg/m2) | 40 602 (35.1) |

| Overweight (25–<30 kg/m2) | 47 683 (41.3) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 23 396 (20.2) |

| Missing | 2681 (2.3) |

| Education,b n (%) | |

| None | 4781 (4.1) |

| Primary | 21 374 (18.5) |

| Lower secondary | 20 889 (18.1) |

| Upper secondary | 38 699 (33.5) |

| Post-secondary non-tertiary | 4905 (4.2) |

| First stage of tertiary | 23 437 (20.3) |

| Second stage of tertiary | 839 (0.7) |

| Other | 475 (0.4) |

| Missing | 202 (0.2) |

| Current smoking habit, n (%) | |

| No | 65 913 (57.0) |

| Yes | 31 890 (27.6) |

| Missing | 17 798 (15.4) |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | |

| Almost every day | 18429 (15.9) |

| Five or six days a week | 2973 (2.6) |

| Three or four days a week | 7423 (6.4) |

| Once or twice a week | 20 771 (18.0) |

| Once or twice a month | 14 492 (12.5) |

| Less than once a month | 10 722 (9.3) |

| Not at all in the last 6 months | 36 369 (31.5) |

| Missing | 4422 (3.8) |

| Living with a partner/spouse, n (%) | |

| No | 28 171 (24.4) |

| Yes | 87 430 (75.6) |

| Number of chronic diseases, mean (s.d.) | 1.6 (1.5) |

| Missing | 143 (0.1) |

| Prescribed drug consumption, n (%) | |

| No | 81 140 (70.2) |

| Yes | 34 294 (29.7) |

| Missing | 167 (0.1) |

| Fruits and vegetables consumption, n (%) | |

| Every day | 64 529 (55.8) |

| 3–6 times a week | 15756 (13.6) |

| Twice a week | 3625 (3.1) |

| Once a week | 1239 (1.1) |

| Less than once a week | 820 (0.7) |

| Missing | 29 632 (25.6) |

| Physical inactivity, n (%) | |

| No | 92 937 (80.4) |

| Yes | 10 009 (8.7) |

| Missing | 12 655 (11.0) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| Austria | 5947 (5.1) |

| Belgium | 8811 (7.6) |

| Bulgaria | 1944 (1.7) |

| Croatia | 2562 (2.2) |

| Czech Republic | 7676 (6.6) |

| Denmark | 5421 (4.7) |

| Estonia | 7158 (6.2) |

| Finland | 1975 (1.7) |

| France | 7238 (6.3) |

| Germany | 7912 (6.8) |

| Greece | 5550 (4.8) |

| Hungary | 2417 (2.1) |

| Ireland | 825 (0.7) |

| Israel | 3412 (3.0) |

| Italy | 7525 (6.5) |

| Luxembourg | 1897 (1.6) |

| Netherlands | 5618 (4.9) |

| Poland | 4261 (3.7) |

| Portugal | 1901 (1.6) |

| Romania | 2055 (1.8) |

| Slovenia | 5089 (4.4) |

| Spain | 7937 (6.9) |

| Switzerland | 4307 (3.7) |

| Sweden | 6163 (5.3) |

| Handgrip strength (kg), mean (s.d.) | 34.3 (12.1) |

| Handgrip strength (kg), n (%) | |

| Third 1 | 39 787 (34.4) |

| Third 2 | 39 079 (33.8) |

| Third 3 | 34 602 (29.9) |

| Missing | 2133 (1.9) |

Missing values were imputed.

Based on International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 1997.

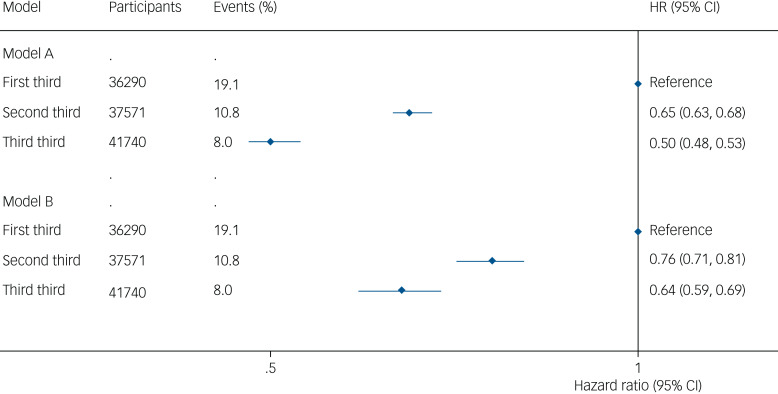

Results from the model adjusted for gender and age only (model A) showed that handgrip strength significantly reduced the risk of depression among participants in the second-third (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.63–0.68) and the final third (HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.48–0.53) (reference first-third) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Prospective associations between handgrip strength (kg) and risk of depression model A, adjusted for age and gender. Model B, adjusted for age, gender, education, country, body mass index, wave, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol, partner, chronic diseases, prescribed drugs consumption and fruits and vegetables consumption. HR, hazard ratio.

The observed associations were consistent in the fully adjusted model (model B), which slightly attenuated the risk of depression in the second-third (HR 0.76, 95% CI, 0.71–0.81) and the final third (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.59–0.69) (reference: first-third) (Figure 2).

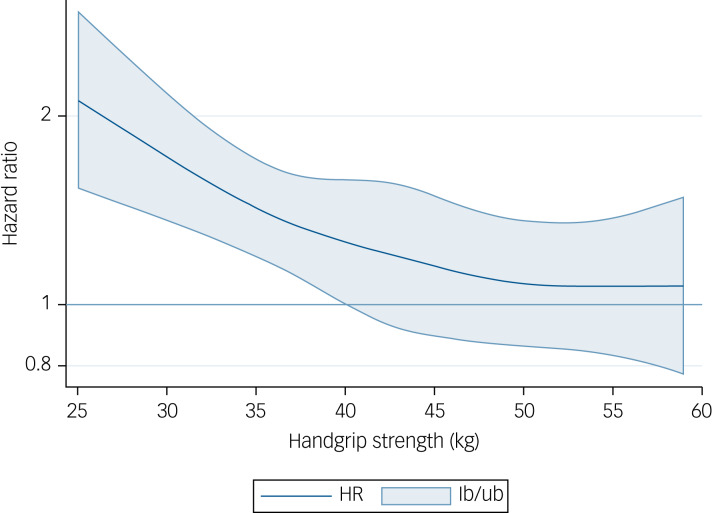

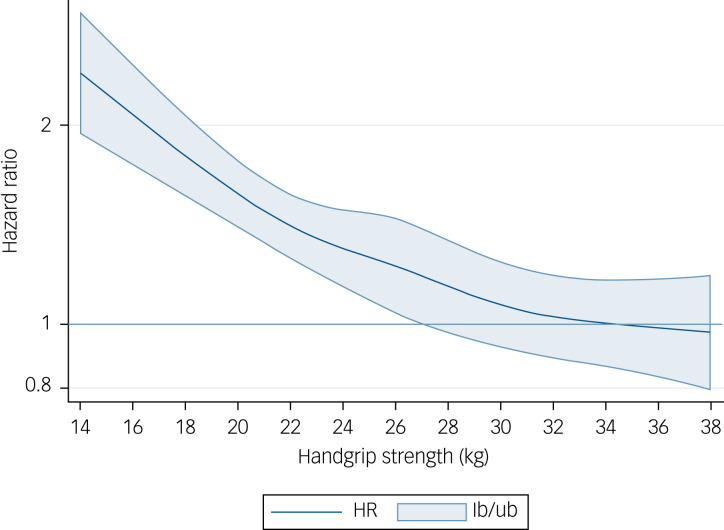

Analyses using restricted cubic spline modelling showed a significant association for each kg increase of handgrip strength and risk of depression up to 40 kg in men (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.08–1.71) (Figure 3) and up to 27 kg in women (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.05–1.55) (Figure 4), values from which no significant risk reduction for depression was observed.

Fig. 3.

Dose–response association (adjusted hazard ratios and associated 95% confidence interval band) between handgrip strength (kg) and risk of depression in men aged 50 years or over. Adjusted for model B (age, education, country, body mass index, wave, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol, partner, chronic diseases, prescribed drugs consumption and fruits and vegetables consumption). HR, hazard ratio; lb, lower boundary; ub, upper boundary.

Fig. 4.

Dose–response association (adjusted hazard ratios and associated 95% confidence interval band) between handgrip strength (kg) and risk of depression in women aged 50 years or over. Adjusted for Model B (age, education, country, body mass index, wave, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol, partner, chronic diseases, prescribed drugs consumption and fruits and vegetables consumption). HR, hazard ratio; lb, lower boundary; ub, upper boundary.

Sensitivity analyses

Results of sensitivity analyses using complete-case analyses did not substantially differ from those of the main analysis. Similarly, analyses removing participants with cases of depression within the first 2 years of follow-up or accounting for mortality and attrition as competing risk provided similar estimates. Additional analyses including the Nelson–Aalen cumulative hazard estimate for the survival time in the imputation model scarcely differed from those displayed in Figure 2.

Discussion

Main findings

In a large sample of older adults from 24 countries, higher levels of handgrip strength were associated with lower risk of depression. When categorised, handgrip strength exhibited an inverse association with risk of depression. Moreover, continuous handgrip strength also displayed an inverse association with risk of depression and an upper boundary for significant depression reduction risk among both men and women. To date, this is the first longitudinal study investigating the association between handgrip strength and risk of depression in older adults using repeated measurements in a large number of countries.

Comparison with findings from other studies

In line with our findings, low muscle strength at baseline was associated with a higher 7-year incident depression among 5228 middle-aged and older Chinese participants.19 Likewise, a study among 17 713 ageing Americans found that every 5 kg of reduced handgrip strength was associated with a 6% higher depression risk.10 Interestingly, we observed an inverse curvilinear significant association for each kg increase of handgrip strength and depression up to 40 kg in men and up to 27 kg in women. This indicates that handgrip strength gains might be particularly beneficial when initial values are low, with a wider range of improvement for men.

Notably, prior research conducted with middle-aged and older European adults observed that handgrip strength may serve as a predictor of depression for specific age and gender subgroups experiencing musculoskeletal conditions.32 Furthermore, an identified reciprocal interaction between depression and frailty in older adults may indicate that a decline in neuromuscular function leads to a higher risk for depression.33 Our results support prior research observing substantial depression reduction with higher handgrip strength for both genders,9 although there is also evidence suggesting differences; for instance, a previous study among community dwelling adults from Ireland reported stronger associations between handgrip strength and depression in women than men.21

Finally, and supporting our findings, a study with 34 129 adults from six non-European countries found that those with weak handgrip strength had a higher prevalence of depression than those with stronger handgrip strength.22

Interpretation of our findings

There may be several underlying explanations – biological as well as psychological – for the present findings. First, handgrip strength has been used as an overall indicator of health status, including sarcopenia.34 A meta-analysis by Chen et al showed that studies incorporating handgrip strength in the diagnosis of sarcopenia tended to show a stronger association between sarcopenia and depression.11 This is in line with a recent study reporting that depression was associated with sarcopenia mainly because of its association with reduced muscle strength.12 Neurotrophins such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 are produced by skeletal muscle among other tissues, and are associated with mood improvements.13

Another plausible mechanism linking handgrip strength with depression is low-grade inflammation, which is present in about a quarter of patients with depression, and over half of patients with this inflammatory condition have showed mildly elevated C-reactive protein levels.35 Interestingly, previous literature suggested that loss of skeletal muscle is associated with high levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein.36 Moreover, other lifestyle factors such as dietary habits may partly explain our results. For instance, low handgrip strength has been related to vitamin D deficiency,37 which has been associated with depression.38 In addition, other dietary habits such as intakes of antioxidants or proteins could also play a role.13

Third, being physically strong may lead to a sensation of psychological well-being. Besides physical decline, ageing per se also results in a reduction in cognitive abilities; being physically active across the lifespan also promotes structural and functional changes in the brain, benefiting cognitive functioning and reducing the risk of neurodegeneration.39 This can be important as ageing adults with cognitive impairment can also experience neuromuscular impairments such as reduced motor unit recruitment or motor neuron firing,40 which presumably will contribute to becoming weaker.

Notably, several psychosocial factors can influence depression, although these have been seldom investigated.17 For instance, different studies found that being stronger was associated with different factors that could influence depression such as good self-rated health,41 less psychological distress (i.e. stress and negative affect) and psychological well-being (i.e. optimism and self-esteem).42 Furthermore, those participating in exercise interventions with greater access to supportive social relationships have greater reductions in depression severity, compared with those with lower access.43 Future longitudinal studies with robust designs and large sample size are needed to understand how psychosocial factors mediate relationship between handgrip strength and depression.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of the present study are the use of a large and representative sample from 24 countries and the use of an objective measure of handgrip strength. Moreover, we also accounted for time-varying handgrip strength and relevant time-varying covariate measurements in our modelling strategy, which reduces the possibility of obtaining biased estimates. Furthermore, we also took measures to minimise the chance of reverse causality by removing data for participants with depression onset that occurred within the first 2 years of follow-up.

On the other hand, interpretations of the present findings should consider several limitations. Importantly, because a substantial number of values was imputed for the main analyses, there is still a chance of biased estimates, although additional analyses accounting for participants with complete values solely showed similar results to those found in the main analyses, which reduces this possibility. Moreover, the plausibility of some degree of residual confounding concerning individual characteristics, life events and occupational hazards exists, although it is unlikely that those can importantly vary the results. Also, the participation rate at baseline was moderate (56%), which might increase the risk of selection bias. Nevertheless, such losses are compensated through refresher samples.23

In addition, the chance of some attrition bias affecting the accuracy of our estimations is plausible, but the average retention rate in SHARE (81%) importantly reduces such a possibility.23 As a result of this, we included a weight variable in the analyses in order to compensate for both non-response and attrition. Moreover, there is still a chance of a certain degree of residual confounding because of lack of controlling for psychological variables such as dysfunctional attitudes and negative emotionality that have been observed to influence the onset of depression.44 Finally, we only accounted for the first onset of depression as the outcome, but future studies might also consider variations of handgrip strength in relation to different depression recurrence.

Implications

These results show higher levels of handgrip strength associated with lower risk of depression in older adults. However, such benefits may be limited up to specific handgrip strength values for both men and women. These findings warrant strength training programmes aimed at older adults to reduce depression risk. Healthcare practitioners may consider using the observed handgrip strength thresholds to screen for potential depression risk in older adults.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.178.

click here to view supplementary material

Author contributions

Concept and design (R.L.-B., B.d.P.C., A.K., L.S.), acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data (R.L.-B., B.d.P.C., A.K., L.S., L.L.A., J.Cal., J.Cas.), drafting of the manuscript (R.L.-B., B.d.P.C., L.L.A., L.S.), critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (R.L.-B., B.d.P.C., A.K., L.S., L.L.A., J.Cal., J.Cas.), statistical analysis (R.L.-B.), obtaining funding (J.Cal., J.Cas.), supervision (R.L.-B., B.d.P.C., A.K., L.S.).

Data availability

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w4.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w7.711, see Börsch-Supan et al (2013) for methodological details.24

Funding

The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001–00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006–062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982, DASISH: GA N°283646) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SHARE-COHESION: GA N°870628, SERISS: GA N°654221, SSHOC: GA N°823782) and by DG Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C) and from various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org). R.L.-B. is supported by the European Union – Next Generation EU.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cui R. A systematic review of depression. Curr Neuropharmacol 2015; 13: 480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santomauro DF, Mantilla Herrera AM, Shadid J, Zheng P, Ashbaugh C, Pigott DM, et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021; 398: 1700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Q, He H, Yang J, Feng X, Zhao F, Lyu J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J Psychiatr Res 2020; 126: 134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng R, Yu C, Liu N, He M, Lv J, Guo Y, et al. Association of depression with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among adults in China. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wei J, Hou R, Zhang X, Xu H, Xie L, Chandrasekar EK, et al. The association of late-life depression with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among community-dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2019; 215: 449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin KA. The public health impact of major depression: a call for interdisciplinary prevention efforts. Prev Sci 2011; 12: 361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.Lancet Psychiatry 2022; 9: 137–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds CF, Cuijpers P, Patel V, Cohen A, Dias A, Chowdhary N, et al. Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annu Rev Public Health 2012; 33: 123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zasadzka E, Pieczyńska A, Trzmiel T, Kleka P, Pawlaczyk M. Correlation between handgrip strength and depression in older adults—a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18; 4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo J, Yao W, Zhang T, Ge H, Zhang D. Exploring the bidirectional associations between handgrip strength and depression in middle and older Americans. J Psychosom Res 2022; 152: 110678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L-K, Liu L-K, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung T-W, Bahyah KS, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the asian working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szlejf C, Suemoto CK, Brunoni AR, Viana MC, Moreno AB, Matos SMA, et al. Depression is associated with sarcopenia due to low muscle strength: results from the ELSA-Brasil Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019; 20: 1641–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasco JA, Williams LJ, Jacka FN, Stupka N, Brennan-Olsen SL, Holloway KL, et al. Sarcopenia and the common mental disorders: a potential regulatory role of skeletal muscle on brain function? Curr Osteoporos Rep 2015; 13: 351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho AF, Maes M, Solmi M, Brunoni AR, Lange S, Husain MI, et al. Is dynapenia associated with the onset and persistence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among older adults? Findings from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. Aging Ment Health 2021; 25: 468–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aagaard P, Suetta C, Caserotti P, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M. Role of the nervous system in sarcopenia and muscle atrophy with aging: strength training as a countermeasure. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010; 20: 49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metsios GS, Moe RH, Kitas GD. Exercise and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2020; 34: 101504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kandola A, Ashdown-Franks G, Hendrikse J, Sabiston CM, Stubbs B. Physical activity and depression: towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019; 107: 525–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syddall H, Cooper C, Martin F, Briggs R, Sayer AA. Is grip strength a useful single marker of frailty? Age Ageing 2003; 32: 650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bao M, Chao J, Sheng M, Cai R, Zhang N, Chen H. Longitudinal association between muscle strength and depression in middle-aged and older adults: a 7-year prospective cohort study in China. J Affect Disord 2022; 301: 81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang XM, Jiao J, Cao J, Guo N, Zhu C, Li Z, et al. Handgrip strength and depression among older Chinese inpatients: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2021; 17: 1267–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDowell CP, Gordon BR, Herring MP. Sex-related differences in the association between grip strength and depression: results from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Exp Gerontol 2018; 104: 147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashdown-Franks G, Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Schuch F, Firth J, Veronese N, et al. Handgrip strength and depression among 34,129 adults aged 50 years and older in six low- and middle-income countries. J Affect Disord 2019; 243: 448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergmann M, Scherpenzeel A, Börsch-Supan A. SHARE Wave 7 Methodology: Panel Innovations and Life Histories. Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy, 2019. (http://www.share-project.org/fileadmin/pdf_questionnaire_wave_7/w7_7.4.3.001_paper_questionnaire_main.pdf).

- 24.Börsch-Supan A, Brandt M, Hunkler C, Kneip T, Korbmacher J, Malter F, et al. data resource profile: the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42: 992–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Börsch-Supan A. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 7. Release version: 7.1.1. SHARE-ERIC, 2020. (http://www.share-project.org/data-documentation/waves-overview/wave-7.html).

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 2007; 18: 800–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prince MJ, Reischies F, Beekman ATF, Fuhrer R, Jonker C, Kivela S-L, et al. Development of the EURO–D scale – a European Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. Br J Psychiatry 1999; 174: 330–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher D, Savva GM, Kenny R, Lawlor BA. What predicts persistent depression in older adults across Europe? Utility of clinical and neuropsychological predictors from the SHARE study. J Affect Disord 2013; 147: 192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng X, Brunet A, Turecki G, Liu A, D'Arcy C, Caron J. Risk factor modifications and depression incidence: a 4-year longitudinal Canadian cohort of the Montreal Catchment Area Study. BMJ Open 2017; 7: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim CR, Jeon YJ, Jeong T. Risk factors associated with low handgrip strength in the older Korean population. PLoS One 2019; 14: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White IR, Royston P. Imputing missing covariate values for the Cox model. Stat Med 2009; 28: 1982–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marconcin P, Marques A, Henriques-Neto D, Gouveia ÉR, Ferrari G, Peralta M, et al. Grip strength as a predictor of depressive symptoms among vulnerable elderly Europeans with musculoskeletal conditions. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soysal P, Veronese N, Thompson T, Kahl KG, Fernandes BS, Prina AM, et al. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2017; 36: 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohannon RW. Grip strength: an indispensable biomarker for older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019; 14: 1681–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osimo EF, Baxter LJ, Lewis G, Jones PB, Khandaker GM. Prevalence of low-grade inflammation in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of CRP levels. Psychol Med 2019; 49: 1958–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunutsor SK, Isiozor NM, Voutilainen A, Laukkanen JA. Handgrip strength and risk of cognitive outcomes: new prospective study and meta - analysis of 16 observational cohort studies. GeroScience 2022; 44: 2007–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendoza-Garcés L, Velázquez-Alva MC, Cabrer-Rosales MF, Arrieta-Cruz I, Gutiérrez-Juárez R, Irigoyen-Camacho ME. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with handgrip strength, nutritional status and T2DM in community-dwelling older Mexican women: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2021; 13: 736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anglin RES, Samaan Z, Walter SD, Sarah DM. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 202: 100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandolesi L, Polverino A, Montuori S, Foti F, Ferraioli G, Sorrentino P, et al. Effects of physical exercise on cognitive functioning and wellbeing: biological and psychological benefits. Front Psychol 2018; 9; 509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon YN, Yoon SS. Sarcopenia: neurological point of view. J Bone Metab 2017; 24: 83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen AW, Beyer N, Flensborg-Madsen T, Grønbæk M, Helge JW. Muscle strength and physical activity are associated with self-rated health in an adult Danish population. Prev Med (Baltim) 2013; 57: 792–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Esteban-Cornejo I, Migueles JH, Mora-Gonzalez J, Henriksson P, et al. Physical fitness and psychological health in overweight/obese children: a cross-sectional study from the ActiveBrains project. J Sci Med Sport 2018; 21: 179–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hallgren M, Lundin A, Tee FY, Burström B, Forsell Y. Somebody to lean on: social relationships predict post-treatment depression severity in adults. Psychiatry Res 2017; 249: 261–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fu Z, Brouwer M, Kennis M, Williams A, Cuijpers P, Bockting C. Psychological factors for the onset of depression: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Open 2021; 11: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2022.178.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w4.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.710, 10.6103/SHARE.w7.711, see Börsch-Supan et al (2013) for methodological details.24