Abstract

Patients with COVID-19 have been reported to have a greater prevalence of hyperglycemia. Cytokine release as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection may precipitate the onset of metabolic alterations by affecting glucose homeostasis. Here we describe abnormalities in glycometabolic control, insulin resistance and β-cell function in patients with COVID-19 without any pre-existing history or diagnosis of diabetes, and document glycaemic abnormalities in recovered patients two months after onset of disease. In a cohort of 551 patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in Italy, we found 46% of patients to be hyperglycemic whereas 27% are normoglycemic. Using clinical assays and continuous glucose monitoring in a subset of patients, we detected altered glycometabolic control, with insulin resistance and an abnormal cytokine profile, even in normoglycaemic patients. Glycaemic abnormalities can be detected in patients, who recovered from COVID-19, for at least two months. Our data demonstrate that COVID-19 is associated with aberrant glycometabolic control, which can persist even after recovery, suggesting that further investigation of metabolic abnormalities in the context of Long COVID is warranted.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, β-cells, COVID-19, type 2 diabetes, type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the more frequent comorbidities of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which can cause lethal respiratory disease1–4. Preliminary studies reported greater prevalence of hyperglycemia in a cohort of patients affected by COVID-195,6; similar data was previously reported in patients affected by SARS-CoV-1, which has been shown to increase the levels of fasting glucose as compared to glucose levels observed in patients with pneumonia unrelated to SARS-CoV-1 infection7–9. Currently, little evidence exists as to whether the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on β-cell function is direct or indirect10,11. It is theoretically possible that SARS-CoV-2 may localize to the endocrine pancreas; indeed, mRNA levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is the primary SARS-CoV-2 receptor, were found to be high in both exocrine and endocrine pancreas8,12, and immunohistochemistry as well as in situ hybridization studies have identified SARS-CoV-1-related antigen in the pancreas of patients who died of SARS-CoV-113,14. Recently evidences of the presence of SARS-CoV2 antigen in the post-mortem pancreases of patients who died of COVID-19 have been reported as well15. Moreover, studies using primary human islets demonstrated that pancreatic β-cells are highly permissive to SARSCoV-2 infection through ACE216,17. Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 also induces a cytokine storm, an exaggerated immune response with a broad spectrum of cytokine production that establishes a systemic proinflammatory milieu, which may play a role in facilitating insulin resistance and β-cell hyperstimulation, leading eventually to altered β-cell function and death16,18–20. SARS-CoV-2 may also enhance the pre-existing proinflammatory status observed in type 2 diabetes21–24 (T2D), thus worsening patient survival and complications. The aim of this study is to examine whether abnormalities in glycometabolic control, insulin resistance and β-cell function are associated with COVID-19 in patients (Acute COVID-19) without any pre-existing history or diagnosis of diabetes. We also evaluated the persistence of these abnormalities over time in patients who recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19). Our study demonstrates the manner in which COVID-19-related hyperglycemia develops and thus may aid in determining the mechanism of disease.

Results

Increased rate of new-onset hyperglycemia in COVID-19

We first evaluated alterations in glycometabolic control in a cohort of 551 patients with COVID-19 admitted to our Academic Center (ASST FBF-Sacco Milan, Presidio Sacco). 151 patients (27%) were affected by T2D with clearly abnormal levels of glycated hemoglobin at hospital admission (Figure 1a, 1c). Among these 151 patients, 86 had a previous history of diabetes, while a diabetes diagnosis was made for the remaining 65 patients according to the ADA criteria25 during their in-hospital stay (Figure 1a). Surprisingly, in 253 out of 551 patients (46%), overt hyperglycemia was measured during hospitalization, while the remaining 147 patients (27%) displayed normal blood glucose levels (Figure 1a). Among patients who exhibited new-onset hyperglycemia at hospital admission for COVID-19, persistent hyperglycemia continued to be observed in the following 6 months in nearly 35% of cases, overt diabetes was diagnosed in ~2% of patients, and the remaining 63% of patients remitted and became normoglycemic (Figure 1b). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1. Importantly, the mean time to clinical improvement from COVID-19 was 14.9±0.5 days for all patients, though it was extended to 20.2±1.3 days in the previously diabetic group (Table 1). As expected, mean HbA1c levels were significantly higher in established/newly diagnosed diabetic patients as compared to new-onset hyperglycemic and normoglycemic patients, and HbA1c levels did not differ between normoglycemic patients and patients with new-onset hyperglycemia (Figure 1c), thus confirming the recent onset of hyperglycemia. Conversely, mean peak blood glucose levels measured during the hospital stay were significantly different among the 3 groups, with blood glucose of patients with established diabetes determined to be highest (Figure 1d). A time to endpoint analysis showed increased mortality in established/newly diagnosed diabetic patients, with an increase in the hazard ratio as compared to normoglycemic (HR: 2.16 CI: 1.27–3.67, p=0.009) and new-onset hyperglycemic (HR: 2.05 CI: 1.28–3.29, p=0.002) patients (Figure 1e). Interestingly, new-onset hyperglycemic patients required a longer in-hospital stay (Figure 1f) and displayed a higher clinical score at hospital admission (Figure 1g), which was also associated with a higher proportion of new-onset hyperglycemic patients requiring oxygen support and ventilation as compared to normoglycemic patients, while no difference in the need for intensive care was reported among groups (Figure 1h–j). An increased odds ratio observed in hyperglycemic patients, after adjusting for age and sex (Figure 1k), further confirmed the association between new-onset hyperglycemia and poor clinical outcomes. Additionally, patients with established T2D required a longer hospitalization stay and displayed worse clinical scores and respiratory parameters as compared to the 2 other groups (Figure 1f–j). Taken together, our data suggest that COVID-19-associated new-onset hyperglycemia may predispose patients to long-term hyperglycemia, worse clinical outcomes and clinical score, prolonged hospital stays and higher demand for oxygen support or positive pressure ventilation.

Figure 1. Increased rate of new-onset hyperglycemia in patients with COVID-19.

(a) Glycometabolic abnormalities in a cohort of 551 patients with COVID-19 (Acute COVID-19) at hospital admission, and (b) glycemic alterations for the hyperglycemic group at 6 months follow-up from their hospital discharge (Post COVID-19). (c-d) Mean HbA1c levels and mean peak blood glucose level were evaluated in diabetic, new-onset hyperglycemic and normoglycemic patients. (e) Survival rates of the 3 groups of patients (diabetic, new-onset hyperglycemic and normoglycemic) represented as time to clinical endpoint analysis, showing an increase in mortality in the diabetic group as compared to the hyperglycemic and normoglycemic groups. (f-g) Time to hospital discharge and clinical score at hospital admission in the 3 patient groups. (h-j) Rate of oxygen requirement, ventilatory support and need for intensive care were also reported and compared in the diabetic, hyperglycemic and normoglycemic groups; dark grey rectangles: diabetic individuals, light grey rectangles: hyperglycemic individuals and white rectangles: normoglycemic individuals. (k) Forest plots comparing the odds ratio of the clinical outcomes (oxygen support, ventilatory support and need for intensive care) between the hyperglycemic and the normoglycemic groups, after adjusting for age and sex. Bar plots in (a-b) represent the proportion of Diabetic, Hyperglycemic and Normoglycemic individuals. Scatter dot plots in (c-d) represent the mean±SEM the error bars represent the SEM, and each dot represent an individual sample (Diabetic (black, n=146), Hyperglycemic (dark grey, n=249), Normoglycemic (light grey, n=140). Survival curve in (e) represents the proportions of individuals at risk who are still alive at regular intervals, up to 30 days from admission and stratified by their glycemic status [(Diabetic (grey lines), Hyperglycemic (blue lines) and Normoglycemic (green lines)]. Bar graphs shown in (f-g) represent respectively the mean±SEM with the error bars represent the SEM. In (f) Diabetic (black, n=151), Hyperglycemic (dark grey, n=253) and Normoglycemic (light grey, n=147) individuals and in (g) Diabetic (dark grey bars, n=144), Hyperglycemic (light grey bars, n=247) and Normoglycemic (white bars, n=140) individuals. Stacked bar graphs in (h-j) represent proportions of patients requiring or not oxygen support (Diabetic n=146, Hyperglycemic n=221 and Normoglycemic n=126), ventilatory support (Diabetic n=146, Hyperglycemic n=219 and Normoglycemic n=149), intensive care need (Diabetic n=143, Hyperglycemic n=218 and Normoglycemic n=128). Log-rank (Mantel Cox) test (e), one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak correction (c, d, f) or Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s correction (g), two-sided Fisher’s/Chi square test (h, i, j) and logistic multivariable regression (k) were used for statistical analysis.

Abbreviations. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; O2, oxygen; VS, ventilatory support; ICU, intensive care unit; CI, confidence interval.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristic of the study population.

| P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 551 | 151 | 253 | 147 | |

| M/F - n (%) | 344/207 (62/38) | 103/48 (67/33) | 159/94 (65/35) | 82/65 (51/49) | |

| 0.17# | |||||

| Age (years) | 61±0.7 | 67±1.1 | 61±0.9 | 55±1.5 | |

| <0.001# | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27±0.5 | 29±1.4 | 27±0.7 | 27±1.1 | |

| 0.009# | |||||

| Hypertension - n | 164 | 66 | 68 | 30 | |

| 0.18# | |||||

| ACE/ARB - n | 119 | 47 | 47 | 25 | |

| 0.67# | |||||

| Time to clinical improvement (days) | 14.9±0.5 | 20.2±1.3 | 13.6±0.6 | 12.8±0.8 | |

| 0.88# | |||||

| Death - n (%) | 85 (15) | 42 (28) | 29 (11) | 14 (9) | |

| 0.86# | |||||

| Time to Death (days) | 11.4±1.4 | 10.5±2.1 | 11.7±1.8 | 12.0±1.9 | |

| 0.009# | |||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 79.1±7.4 | 108.2±18.7 | 74.6±8.0 | 45.5±9.5 | |

| 0.38# |

Abbreviations: M, males; F, females; n, number of patients; BMI, body mass index; kg, kilogram; m2, square meter; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; IL-6, interleukin-6; pg, picogram; mL, milliliter; SEM, standard error of mean; ns, not significant. Data are expressed as mean±SEM unless otherwise reported.

P Diabetes vs. Hyperglycemic;

P Diabetes vs. Normoglycemic;

P Hyperglycemic vs. Normoglycemic.

Continuous glucose monitoring demonstrated glycemic abnormalities in COVID-19

In order to evaluate alterations in glycemic control not detected by fasting glycemia, professional continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) was performed in patients with COVID-19 (n=10) or in patients who eventually recovered from COVID-19 (n=10) and with normal fasting glucose, in healthy controls (n=15) and in patients with T2D (n=10) (Figure 2a–h). CGM was performed during the acute phase of COVID-19 and at 62.0±6.5 days after disease onset (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S1). Demographic and clinical characteristics of the aforementioned subgroups are reported in Table 2. Analysis of CGM reports collected from subgroups showed that in normoglycemic patients, COVID-19 is associated with an overall impaired glycemic profile, as demonstrated by a significantly longer duration of glycemia above 140 mg/dL (Figure 2a), significantly higher glycemic AUC above 140 mg/dL (Figure 2b) and higher mean postprandial glycemia at 60 minutes (Figure 2c). COVID-19 is also associated with higher glycemic variability, as shown by higher coefficient of variability (Figure 2e) and higher standard deviation (Figure 2f) as compared to healthy controls. Surprisingly, glycemic alterations persist in some patients who have recovered from COVID-19. Indeed, compared to healthy controls, Post COVID-19 patients showed a greater duration of glycemia above 140 mg/dL (Figure 2a), higher mean postprandial glycemia at 120 minutes (Figure 2d), higher mean blood glucose (Figure 2g), and higher nadir blood glucose (Figure 2h). For other parameters such as coefficient of variability and standard deviation, patients who recovered from COVID-19 are similar to healthy controls but different from patients with Acute COVID-19 (Figure 2e and 2f). Collectively, our findings suggest that abnormal glycometabolic control occurs in patients with COVID-19, although to a lower extent as compared to glycemic alterations observed in patients with T2D, and that this effect persists even after recovery from the disease.

Figure 2. Continuous glucose monitoring demonstrated glycemic abnormalities in patients with COVID-19.

(a) Duration of glycemia measured above 140 mg/dL, (b) AUC of glycemia levels above 140 mg/dL; (c) mean postprandial glycemia at 60 minutes, (d) mean postprandial glycemia at 120 minutes, (e) coefficient of variability, (f) standard deviation, (g) mean glycemia values and (h) nadir blood glucose in healthy controls, in patients with COVID-19 (Acute COVID-19), in patients who recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19) and in patients with T2D. Data are depicted using box plots and whiskers where the upper and lower bounds of the boxes represent the interquartile ranges. The horizontal line inside each box reflect the median and the whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. Each dot represents an individual sample (Controls (blue), COVID-19 (maroon) and post-COVID-19 (moss)). Ordinary one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction was used when applicable for calculating statistical significance between all groups. Data are representative of n=12 samples analyzed for controls, n=8 (except for e, n=7) for Acute COVID-19, n=8 for Post COVID-19 and n=10 for patients with T2D. T2D group (shown in grey) is included for visual comparison only, ie it was not included in the statistical analysis.

Abbreviations. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; AUC, area under the curve; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristic of subgroups analyzed for the CGM and arginine tests.

| P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 35 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| M/F - n | 21/14 | 10/5 | 4/6 | 7/3 | 6/4 | 0.24† |

| 0.9§ | ||||||

| 0.9# | ||||||

| 0.36* | ||||||

| 0.65ξ | ||||||

| 0.9ψ | ||||||

| Age (mean±SEM) | 45.9±2.1 | 47.2±3.1 | 43.0±4.7 | 46.9±3.8 | 50.7±3.9 | 0.84† |

| 0.99§ | ||||||

| 0.90# | ||||||

| 0.80* | ||||||

| 0.53ξ | ||||||

| 0.96ψ | ||||||

| Smoking - n | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.12† |

| 0.12§ | ||||||

| 0.61# | ||||||

| 0.9* | ||||||

| 0.9ξ | ||||||

| 0.9ψ | ||||||

| Familiality T2D - n | 13 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0.21† |

| 0.41§ | ||||||

| 0.68# | ||||||

| 0.9* | ||||||

| 0.62ξ | ||||||

| 0.9ψ | ||||||

| BMI (mean±SEM) | 23.4±0.6 | 23.3±0.6 | 24.8±2.1 | 22.4±1.5 | 27.2±0.3 | 0.72† |

| 0.94§ | ||||||

| 0.014# | ||||||

| 0.53* | ||||||

| 0.40ξ | ||||||

| 0.020ψ | ||||||

| Hypertension (%) | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.9† |

| 0.9§ | ||||||

| 0.022# | ||||||

| 0.9* | ||||||

| 0.032ξ | ||||||

| 0.032ψ | ||||||

| Time after first symptom - days (mean±SEM) | 34.0±5.7 | - | 22.9±4.1 | 62.0±3.2 | - | <0.001* |

| Baseline clinical score (mean±SEM) | 3.1±0.3 | - | 3.7±0.3 | 2.0±0.0 | - | <0.001* |

| Therapies - n | ||||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.55* |

| Antiviral | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.06* |

| Monoclonal Ab | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9* |

| Steroids | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.33* |

| LMWH | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0.001* |

| Antibiotics | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.9* |

| Diabetes-associated therapies - n | ||||||

| Metformin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | - |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| No therapies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | - |

Abbreviations. CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; SEM, standard error of mean; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; T2D, type 2 diabetes; n, number of patients; M, males; F, females; BMI, body mass index; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; Ab, antibody; ns, not significant.

P Controls vs. Acute COVID-19;

P Controls vs. Post COVID-19;

P Controls vs. T2D;

Acute COVID-19 vs. Post COVID-19;

Acute COVID-19 vs. T2D;

Post COVID-19 vs. T2D.

Insulin resistance and β-cell hyperstimulation post COVID-19

In order to evaluate the extent of insulin resistance and improper β-cell function, we performed serum hormone sampling under fasting conditions and after an arginine stimulation test in the subgroup of patients who underwent CGM. Although the arginine stimulation test is not considered to be the standard methodology for assessing β-cell function, several clinical trials have confirmed its reliability and reproducibility when compared to standardized tests26. Mean fasting insulin, proinsulin, C-peptide levels, HOMA-B and HOMA-IR but not insulin to proinsulin ratio were significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 as compared to healthy controls (Figure 3a–f). Interestingly, patients with COVID-19 showed significantly higher acute insulin responses to arginine (AIRmax) (Figure 3g) and higher area under the curve for insulin and C-peptide in response to the arginine test as compared to healthy controls (Figure 3h and 3i). Furthermore, patients who recovered from COVID-19 also showed significantly higher fasting insulin levels, C-peptide levels, HOMA-B and HOMA-IR as compared to healthy controls, with no differences observed in the insulin:proinsulin ratio (Figure 3a–f). Similarly, acute insulin responses to arginine (AIRmax) were significantly higher in patients who recovered from COVID-19 as compared to healthy controls (Figure 3g). Significantly higher area under the curve for insulin, but not for C-peptide, was found in patients who recovered from COVID-19 as compared to healthy controls (Figure 3h and 3i). Taken together, our data suggest that in patients with COVID-19 and in patients who have recovered from COVID-19, the hormone profile is altered both under fasting conditions and after an arginine stimulation test, which demonstrates persistent insulin resistance, and that patients with COVID-19 display a similar hormonal profile to T2D patients (Figure 3a–i). Collectively, signs of β-cell hyperstimulation, and aberrant functioning were evident in patients with COVID-19, which may eventually exhaust β-cells and lead to their demise27,28.

Figure 3. Persistent insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction are evident in patients with COVID-19.

(a) Mean fasting insulin, (b) mean fasting proinsulin, (c) fasting insulin to proinsulin ratio, (d) fasting C-peptide levels, (e) HOMA-B and (f) HOMA-IR are shown for healthy controls, for patients with COVID-19 (Acute COVID-19), for patients who recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19) and for patients with T2D. (g) AIRmax, (h-i) mean AUC of insulin and C-peptide after arginine test are shown for healthy controls, for Acute COVID-19, or for Post COVID-19 and for patients with T2D. Data are depicted using box plots and whiskers where the upper and lower bounds of the boxes represent the interquartile ranges. The horizontal line inside each box reflect the median and the whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values. Each dot represents an individual sample (Controls (blue), COVID-19 (maroon) and Post COVID-19 (moss). Ordinary one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction was used when applicable for calculating statistical significance between all groups. Data are representative of n=15 (except for e, n=10) samples analyzed for controls, n=10 (except for e, n=8) for Acute COVID-19, n=10 (except fore, n=7) for Post COVID-19 and n=10 (except for g, n=7) for patients with T2D. T2D group (shown in grey) is included for visual comparison only, ie it was not included in the statistical analysis.

Abbreviations. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; T2D, type 2 diabetes; AU, arbitrary unit; HOMA-B, homeostasis model assessment of β-cell dysfunction; HOMA-IR; homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; AIR-max, maximal acute insulin response; AUC, area under the curve.

Changes in the secretome are detected in Post COVID-19

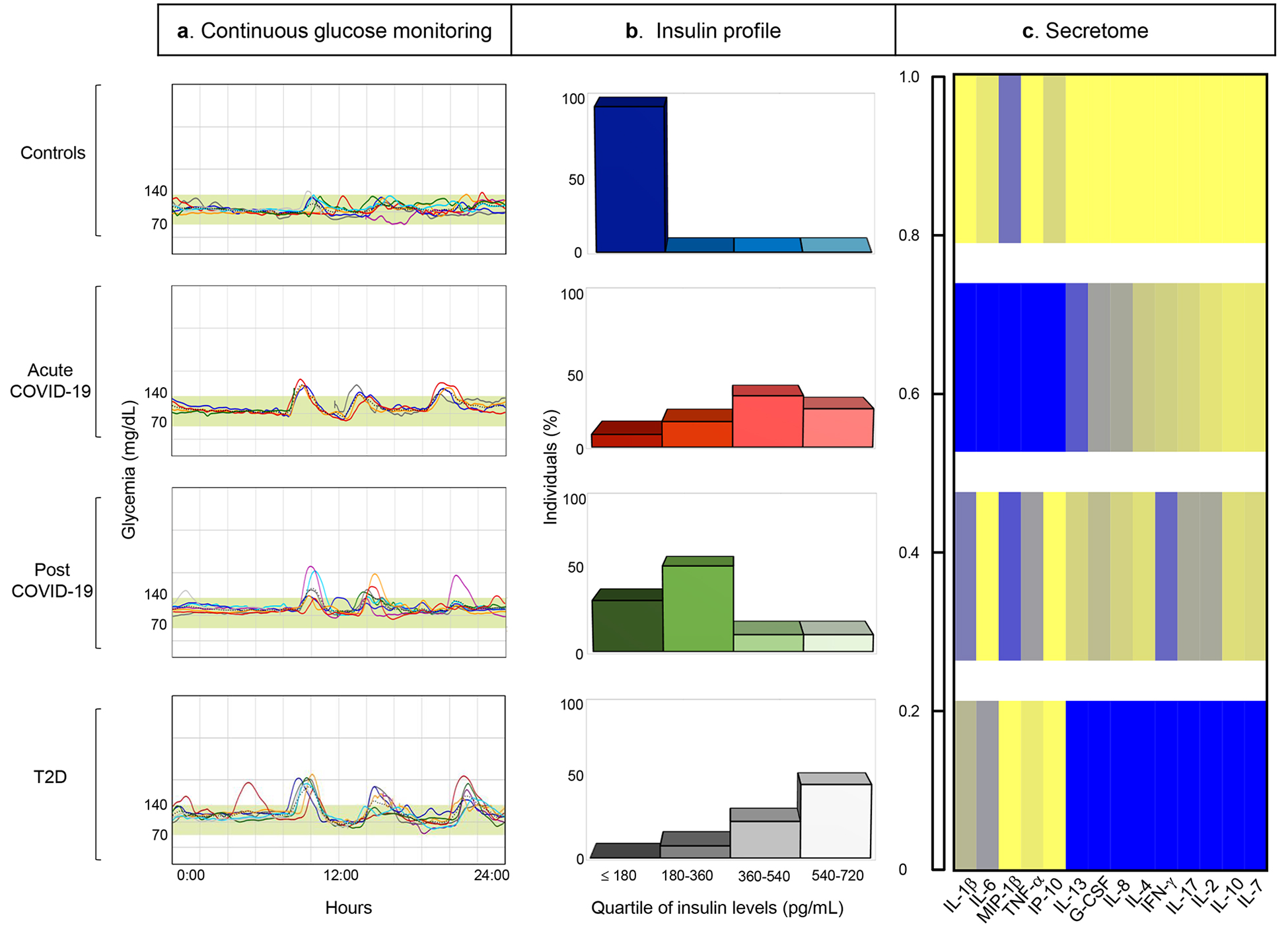

Given reported higher cytokine levels in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients29–32, we evaluated the cytokine profile (i.e. secretome) in the serum of patients with COVID-19 or in those who recovered from COVID-19 who had also undergone CGM and an arginine stimulation test. To this end, we performed a multiplexed immunoassay analysis using a Luminex reader, which measures 17 distinct analytes including cytokines and other secreted proteins. Of the 17 analytes assessed, 10 cytokines (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, G-CSF, MIP-1β and TNF-α) were found to be significantly upregulated in the serum of patients with COVID-19 as compared to healthy controls (Figure 4a–n and Supplemental Table S2). Notably, 10 out of 17 analytes examined (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, G-CSF and IFN-γ) were also increased in the serum of patients who recovered from COVID-19 (Figure 4a–n). Similar to the pattern observed in patients with COVID-19, several analytes were found to be upregulated in the sera of patients with T2D (Figure 4a–n). A reduction in IL-6 and IP-10 levels was observed in the serum of patients who recovered from COVID-19 as compared to healthy controls (for IP-10) and compared to those who had active COVID-19 (for IL-6 and IP-10) (Figure 4d and 4n). Some of the aforementioned cytokines (i.e. IL-2, IL-17 and IFN-γ) appeared exclusively upregulated in patients who recovered from COVID-19 as compared to healthy controls (Figure 4b, 4i and 4l). Moreover, an overall inflammatory score appeared increased in patients with COVID-19 and in those who recovered from COVID-19 (Supplemental Figure S1a). Inflammatory score correlates with the HOMA-IR, confirming the inflammatory origin of COVID-19-associated insulin resistance (Supplemental Figure S1b). Altogether, our data demonstrate an altered secretome in patients with COVID-19 and in patients who have recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19), with an overall increase in many serum cytokine levels but with a different profile from that which is observed in patients with T2D. Overall, CGM, the hormonal profile and the secretome showed many differences in patients with COVID-19, in those who recovered from COVID-19 and in patients with T2D as compared to controls (Figure 5a–5c).

Figure 4. Changes in the secretome are detected long after recovery from COVID-19.

(a-n) The peripheral levels of 14 circulating cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, IL-17, G-CSF, MIP-1β, , IFN-γ, TNF-α and IP-10) were assessed by a Luminex assay using the serum of healthy controls, patients with COVID-19 (Acute COVID-19) and, patients who recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19) and patients with T2D. Data are represented as scatter dot plots showing the mean±SEM. Each dot represents an individual sample (Controls (blue), COVID-19 (maroon) and Post COVID-19 (moss). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Kruskal-Wallis test. Data are representative of n=14 (except for n, n=4) samples analyzed for controls, n=9 (except for n, n=5) for patients with Acute COVID-19, n=10 (except for n, n=8) for patients with Post COVID-19 and n=10 for patients with T2D. T2D group (shown in grey) is included for visual comparison only, ie it was not included in the statistical analysis.

Abbreviations. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; T2D, type 2 diabetes; IL-, Interleukin; G-CSF, Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; MIP-1β, Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta; IFN-γ, Interferon gamma; TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor; IP-10, Interferon gamma-induced protein 10.

Figure 5. Evidence of glycometabolic, hormonal and secretome abnormalities in patients with COVID-19.

Comparative schematic/analysis showing abnormalities in (a) continuous glucose monitoring, (b) insulin levels and (c) secretome profile in patients with COVID-19 (Acute COVID-19), in those who recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19) and in patients with T2D, demonstrating similarities with those found in patients with T2D. Data in (c) are represented as color-coded values showing the average of serum cytokine mean-normalized levels in each group, normalized across groups.

Abbreviations. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; T2D; type 2 diabetes; IL-, Interleukin; G-CSF, Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; MIP-1β, Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta; IFN-γ, Interferon gamma; TNF-α, Tumor Necrosis Factor; IP-10, Interferon gamma-induced protein 10.

In order to mechanistically understand whether elevated peripheral levels of cytokines have a clinical impact on glycometabolic control, we evaluated data retrieved from our patient database and observed that patients with preexisting diabetes had higher peripheral levels of IL-6 at hospital admission as compared to normoglycemic patients, but not compared to new-onset hyperglycemic patients (Table 1). In new-onset hyperglycemic patients with COVID-19, peripheral IL-6 levels correlated with fasting glucose levels (Supplemental Figure S2a). Interestingly, among new-onset hyperglycemic patients, 39 showed particularly elevated peripheral IL-6 levels, and thus received Tocilizumab as adjuvant therapy to reduce the COVID-19-associated inflammation. Tocilizumab-treated new-onset hyperglycemic patients with COVID-19 showed a greater reduction in glycemic levels at the time of hospital discharge compared to patients who did not receive Tocilizumab (Supplemental Figure S2b). This exploratory study requires further investigation to confirm a link between cytokine levels and glycometabolic abnormalities.

Discussion

It has recently become evident that a mutual interplay between COVID-19 and diabetes exists, involving a complex pathophysiological feature underlying hyperglycemia and overall glycometabolic distress16,33–36. Indeed, clinical evidence has suggested that COVID-19 may severely reduce life expectancy in patients with T2D34,37–39. In our study, we demonstrated the presence of new-onset hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and β-cell hyperstimulation in patients with COVID-19 without a prior history of diabetes. This effect appears to be mediated by the abnormal secretome, which remained altered long after remission of the disease. While metabolic alterations have been described as consequences of other viral infections40,41, COVID-19 may induce an inflammatory state resembling that which is observed in T2D33,35,36 but which is more exacerbated; in the long-term, these effects may lead to β-cell exhaustion and worsening of diabetes caused by islet hyperstimulation and glucose toxicity42–50. Indeed, newly hyperglycemic patients treated with Tocilizumab showed a significant reduction in glycemic levels at the time of their discharge from the hospital as compared to patients who did not receive Tocilizumab. The negative results of the latest placebo-controlled trial with Tocilizumab, which enrolled moderately ill hospitalized patients, suggest that our results are possibly metabolic/endocrine rather than disease-related51. The percentage of patients with hyperglycemia is surprisingly high among patients admitted to the hospital for COVID-19related pneumonia. Patients without a previous history or diagnosis of diabetes and admitted to the hospital with normal glycated hemoglobin showed varying degrees of glycometabolic impairment and β-cell dysfunction. This is notable in view of the elevated mortality rates that we and others have observed in patients with COVID-19 who presented with hyperglycemia9,38,52,53.

In this study, we observed glycemic alterations not only in the acute phase of COVID-19 but also long after remission of the disease. We acknowledge that our study has limitations: firstly, we recognize the potentially inadequate sample size, which may limit the conclusions that can be drawn from these data. A sample of 551 patients may allow for reasonable power for the study, but the subgroup analysis may be under-powered because of the small sample size. We further acknowledge that the participants included in this subgroup analysis displayed lower age and BMI as compared to patients included in the entire study. Participant recruitment into study groups was performed consecutively as patients were admitted to the hospital, and recruitment was thus devoid of any bias; indeed, no statistical differences were evident when comparing demographic parameters within the subgroups. Furthermore, due to increased morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19 in older patients, the average age of patients eligible for and included in this study was lower than that of the general population. Lastly, patients were recruited from a single large academic hospital (ASST FBF-Sacco Milan, Presidio Sacco), such that the study results may be subject to hospital selection bias.

Interestingly, one of the major findings of our work is that CGM allowed for detection of alterations in glucose homeostasis not otherwise detectable by self-measurement of fasting blood glucose54. In accordance with this observation, we also reported alterations in the hormone profile, both at basal and after stimulation testing, with higher insulin, proinsulin and C-peptide levels in patients with COVID-19 (Acute COVID-19) and in patients who recovered from COVID-19 (Post COVID-19) as compared to healthy controls. Our observations further indicate that COVID-19 disrupts insulin signaling and β-cell function, in addition to the previously reported long term effects on cardiovascular, neurological and renal function55,56.

Our data suggests that a proinflammatory milieu initiated by cytokine storm, in which IL-6 plays a primary albeit not exclusive role, induces insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction as shown for T2D57,58. Any bias associated with pharmacologic therapy can likely be excluded, based on the fact that very few patients received steroids and hydroxychloroquine during the course of the disease. In conclusion, in the present study we showed that the cytokine profile in the serum of patients with COVID-19 and survivors is markedly different from control subjects and that the observed hyperglycemia, insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction might be due to the proinflammatory milieu initiated by a cytokine storm. This study is the first to demonstrate that SARS-CoV-2 induces insulin resistance and disrupts proper β-cell function, which can result in clinically evident hyperglycemia detectable even in the post-acute phase. Our findings suggest the persistence of aberrant glycometabolic control long after the recovery from the disease. This persistence should be investigated in larger cohort and its effect on clinical symptoms and sequalae should be carefully addressed.

Materials and Methods

Study design and outcomes

All research studies and analysis performed in this paper were done in accordance with the local Ethical Research Committee of Milan (Comitato Etico Milano Area 1) which granted the approval of the present study (approval no. 2020/ST/167). The written informed consent and ethical committee approval covered all experimental analysis performed and reported in this study.

Data from patients admitted for SARS-CoV-2 acute infection at ASST FBF-Sacco Milan, Presidio Sacco, from February 1, 2020 to May 15, 2020 were collected. Confirmed COVID-19 was defined as detection of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR in respiratory samples. Patient baseline clinical score was defined on the basis of a modified ordinal score comprising 7 major points as follows and as previously reported34: 1, not hospitalized with resumption of normal activities; 2, not hospitalized, but unable to resume normal activities; 3, hospitalized, not requiring supplemental oxygen; 4, hospitalized, requiring supplemental oxygen; 5, hospitalized, requiring noninvasive mechanical ventilation; 6, hospitalized, requiring invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO); and 7, death. All clinical data were extracted from patient electronic medical reports with regard to baseline demographic distributions, clinical data, laboratory data, management, and outcome data (Table 1). Glycemia levels were evaluated for each patient at 3 different time points: admission to the emergency room, in-hospital stay and discharge from hospital. HbA1c levels during in-hospital stays were also recorded where available. Patients were classified as previously known diabetic based on a known history of diabetes or based on an anti-diabetic drug regimen. Patients were classified as having newly diagnosed diabetes based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria25. Patients were classified as hyperglycemic based on a blood glucose measurement recorded between 100 and 199 mg/dL or 2 blood glucose measurements >100 mg/dL and <126 mg/dL. Patients were classified as normoglycemic in the absence of a previously known history of diabetes or hyperglycemia, as well as if they displayed normal levels of glycemia and HbA1c according to the ADA criteria2. Groups of consecutive patients with COVID-19 or patients who recovered from COVID-19 infection, based on the clinical evaluation by the Infectious Disease and Respiratory Division of ASST FBF-Sacco Milan and based on a prior positive COVID-19 test, and who were normoglycemic with no previous history of diabetes or IFG (impaired fasting glucose) or IGT (impaired glucose tolerance), were enrolled within the original group of 551 patients and compared with a paired group of healthy control subjects. We also included a small group of patients with T2D as a further control. Patients with T2D were treated with Metformin and/or were following dietary restrictions. Patients underwent glucose monitoring using a retrospective professional continuous glucose monitoring device (please see Continuous Glucose Monitoring) and an i.v. arginine acute stimulation insulin secretion test26 (please see Hormone Level Assessment). Inclusion criteria were defined by recruitment of male and female participants, participant age (>18 years and <80 years with normoglycemia), no previous history of diabetes or IFG/IGT, and no use of drugs with known effects on glucose metabolism. Exclusion criteria were age <18, previous history of diabetes or impaired fasting glycemia (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), use of drugs with known effects on glucose metabolism, and pregnancy.

Continuous glucose monitoring

A group of participants among normoglycemic individuals including healthy controls (n=12), patients with COVID-19 (n=8) and patients who recovered from COVID-19 (n=8) enrolled within the original group of 551 patients, underwent complete glycemic profiling via 7-day professional retrospective continuous glucose monitoring (Medtronic Envision™ Pro CGM, Medtronic Minimed, Northridge, CA). The system consists of a fully calibrated device composed of an EC-approved Envision Sensor, Envision Recorder, Envision™ Pro Application and CareLink™ Pro Software. Both patients and clinical site staff were blinded to CGM results during the study. Patient informed consent on CareLink Software for Professional CGM Systems was obtained for each registration. Mean blood glucose, estimated HbA1c, peak and nadir blood glucose, time above 140 mg/dL, AUC above 140 mg/dL limit, mean postprandial glycemia values at 60 and 120 minutes, standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variability (CV) were evaluated during the registration period.

Hormone level assessment

Insulin and C-peptide secretion was determined using an intravenous arginine stimulation test as previously described14. An intravenous catheter was inserted into the antecubital vein of the patient’s arm. The sampling catheter was kept patent by slow infusion of 0.9% saline when not used. Baseline samples were taken at 0 min. A maximal stimulating dose of arginine hydrochloride (5 gr) was then injected intravenously for 45 s. Samples were taken at +2, +5 min, +10 and +30 min. For fasting glucose, the insulin secretory response to arginine (AIRmax) was determined as the mean of the three highest insulin values from minutes 2, 5 and 10 subtracted from the baseline insulin. The fasting insulin to proinsulin ratio was calculated as an index of β-cell function as previously described59. Insulin resistance was calculated using the Homeostasis Model Assessment (HOMA-IR) formula: fasting insulin [mIU/mL] fasting glucose [mmol/L]/22.5)60. HOMA-B index was calculated using the following formula: 20 × fasting insulin (μIU/ml)/fasting glucose (mmol/ml) - 3.5. (Diabetes Care. 2007 Jul; 30(7): 1747–1752.).

Inflammatory score

Each plasma cytokine value was stratified into quintiles to determine cutoff points and assign a score ranging from 0, which was assigned to the lowest quintile, to 4, which was assigned to the highest quintiles58.

Biochemical analyses

Fasting serum samples of patients and controls were collected at the designated time points, and frozen at −80°C for biochemical evaluation. Baseline levels of the analytes G-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17A, MCP-1, MIP-1β, TNF-α and IP-10 were assessed in the serum of patients and controls by a magnetic microsphere-based Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 17-plex immunoassay (catalogue number: M5000031YV) on a Bio-Plex 200 system (both from Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum proinsulin (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden, catalogue number 10–1118-01) and HbA1c (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA, USA, catalogue number OKEH00660) levels at baseline were assessed by ELISA using commercial kits according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. Basal glycemia was assessed using a colorimetric assay (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA, catalogue number EIAGLUC) on serum samples collected in potassium oxalate/sodium fluoride-containing tubes. Finally, serum samples obtained from subjects who underwent an arginine stimulation test were collected at each arginine test time point (T0-T4) and were evaluated for insulin, C-peptide and glucagon concentrations using the Bio-Plex Pro Human Diabetes 10Plex Assay kit (catalogue number 171A7001M) and a Bio-Plex 200 reader (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard errors, and categorical variables are presented as proportions. We used independent sample t-tests to compare continuous variables and chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test to compare categorical variables. For multiple comparisons, one-way or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test between the group of interest and all other groups was used, when applicable. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to assess relation among mortality and other population characteristics. Log-Rank Test was used to compare survival curves. Two-tailed P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multivariable logistic regression was used to model the relationships between risk factors and clinical outcomes (Stata version 12; StataCorp, College Station, TX). Age and sex were included in the multivariable logistic regression analysis performed for each clinical outcome. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used in the time to clinical endpoint analysis among groups (GraphPad Prism version 8.4.3; GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Spearman’s correlation was to examine association between glycemia and peripheral IL-6 levels. Two-tailed p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Microsoft Excel version 16.30 was used to generate graph related to panel b of Figure 5.

Power analysis

Sample size was set at 15 in the control group and 10 in the other subgroups, as it would provide the study with 80% power to detect a difference of at least 15% in the mean AUC insulin response to 5 g intravenous Arginine between the groups, with a significance level of α=0.05, given that the mean AUC insulin response observed in subjects with normal glucose tolerance undergoing an Arginine test is 1,083±132 pmol/l61.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Fondazione Romeo and Enrica Invernizzi for outstanding support. P.F. and F.D are supported by the Italian Ministry of Health grant RF-2016-02362512. F.D. is supported by a SID Lombardia Grant and by the EFSD/JDRF/Lilly Programme on Type 1 Diabetes Research 2019. R.A. is supported by K24 AI116925. V.U. is supported by the Fondazione Diabete Ricerca (FO.DI.RI) Società Italiana di Diabetologia (SID) fellowship. We thank Mollie Jurewicz for technical editing of this work.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this manuscript.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data files are provided with this paper.

References

- 1.Xu B, Kraemer MUG & Open, C.-D. C. G. Open access epidemiological data from the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Infect Dis 20, 534, doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30119-5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tay MZ, Poh CM, Renia L, MacAry PA & Ng LFP The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 363–374, doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-03118 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P & Shi ZL Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol, doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng SQ & Peng HJ Characteristics of and Public Health Responses to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak in China. J Clin Med 9, doi: 10.3390/jcm9020575 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513, doi: 10.1016/S01406736(20)30211-7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadini GP, Morieri ML, Longato E & Avogaro A Prevalence and impact of diabetes among people infected with SARS-CoV-2. J Endocrinol Invest 43, 867–869, doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01236-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang JK et al. Plasma glucose levels and diabetes are independent predictors for mortality and morbidity in patients with SARS. Diabet Med 23, 623–628, doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01861.x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang JK, Lin SS, Ji XJ & Guo LM Binding of SARS coronavirus to its receptor damages islets and causes acute diabetes. Acta Diabetol 47, 193–199, doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0109-4 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apicella M et al. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8, 782–792, doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steenblock C, et al. Beta-cells from patients with COVID-19 and from isolated human islets exhibit ACE2, DPP4, and TMPRSS2 expression, viral infiltration and necroptotic cell death. Research Square [preprint], doi:DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-88524/v1 (Oct 2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusmartseva I et al. Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Entry Factors in the Pancreas of Normal Organ Donors and Individuals with COVID-19. Cell Metab 32, 1041–1051 e1046, doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.11.005 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L et al. A Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-based Platform to Study SARS-CoV-2 Tropism and Model Virus Infection in Human Cells and Organoids. Cell Stem Cell 27, 125–136 e127, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.06.015 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu F et al. ACE2 Expression in Pancreas May Cause Pancreatic Damage After SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 18, 2128–2130 e2122, doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.040 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding Y et al. Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J Pathol 203, 622–630, doi: 10.1002/path.1560 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller JA et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects and replicates in cells of the human endocrine and exocrine pancreas. Nat Metab 3, 149–165, doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00347-1 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bornstein SR et al. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 8, 546–550, doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30152-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dungan KM, Braithwaite SS & Preiser JC Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 373, 1798–1807, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60553-5 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dave GS & Kalia K Hyperglycemia induced oxidative stress in type-1 and type-2 diabetic patients with and without nephropathy. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 53, 68–78 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Carvalho Vidigal F, Guedes Cocate P, Goncalves Pereira L & de Cassia Goncalves Alfenas R The role of hyperglycemia in the induction of oxidative stress and inflammatory process. Nutr Hosp 27, 1391–1398, doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.5.5917 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabbri A et al. Stress Hyperglycemia and Mortality in Subjects With Diabetes and Sepsis. Crit Care Explor 2, e0152, doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000152 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niewczas MA et al. A signature of circulating inflammatory proteins and development of endstage renal disease in diabetes. Nat Med 25, 805–813, doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0415-5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folli F et al. Proteomics reveals novel oxidative and glycolytic mechanisms in type 1 diabetic patients’ skin which are normalized by kidney-pancreas transplantation. PLoS One 5, e9923, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009923 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bassi R & Fiorina P Impact of islet transplantation on diabetes complications and quality of life. Curr Diab Rep 11, 355–363, doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0211-1 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.La Rocca E et al. Patient survival and cardiovascular events after kidney-pancreas transplantation: comparison with kidney transplantation alone in uremic IDDM patients. Cell Transplant 9, 929–932, doi: 10.1177/096368970000900621 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 43, S1–S2, doi: 10.2337/dc20-Sint (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shankar SS et al. Standardized Mixed-Meal Tolerance and Arginine Stimulation Tests Provide Reproducible and Complementary Measures of beta-Cell Function: Results From the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health Biomarkers Consortium Investigative Series. Diabetes Care 39, 1602–1613, doi: 10.2337/dc15-0931 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erion K & Corkey BE beta-Cell Failure or beta-Cell Abuse? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9, 532, doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00532 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weir GC & Bonner-Weir S Five stages of evolving beta-cell dysfunction during progression to diabetes. Diabetes 53 Suppl 3, S16–21, doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s16 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Jiang M, Chen X & Montaner LJ Cytokine storm and leukocyte changes in mild versus severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: Review of 3939 COVID-19 patients in China and emerging pathogenesis and therapy concepts. J Leukoc Biol 108, 17–41, doi: 10.1002/JLB.3COVR0520-272R (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L & Song J Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 46, 846–848, doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaninov N In the eye of the COVID-19 cytokine storm. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 277, doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0305-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta P et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 395, 1033–1034, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solerte SB, Di Sabatino A, Galli M & Fiorina P Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) inhibition in COVID-19. Acta Diabetol 57, 779–783, doi: 10.1007/s00592-020-01539-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solerte SB et al. Sitagliptin Treatment at the Time of Hospitalization Was Associated With Reduced Mortality in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and COVID-19: A Multicenter, Case-Control, Retrospective, Observational Study. Diabetes Care, doi: 10.2337/dc20-1521 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hollstein T et al. Autoantibody-negative insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus after SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case report. Nat Metab 2, 1021–1024, doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-00281-8 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naguib MN, et al. New onset diabetes with diabetic ketoacidosis in a child with multisystem inflammatory syndrome due to COVID-19. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab, doi: 10.1515/jpem-2020-0426 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obukhov AG et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infections and ACE2: Clinical Outcomes Linked With Increased Morbidity and Mortality in Individuals With Diabetes. Diabetes 69, 1875–1886, doi: 10.2337/dbi20-0019 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sardu C et al. Outcomes in Patients With Hyperglycemia Affected by COVID-19: Can We Do More on Glycemic Control? Diabetes Care 43, 1408–1415, doi: 10.2337/dc20-0723 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cole SA, Laviada-Molina HA, Serres-Perales JM, Rodriguez-Ayala E & Bastarrachea RA The COVID-19 Pandemic during the Time of the Diabetes Pandemic: Likely Fraternal Twins? Pathogens 9, doi: 10.3390/pathogens9050389 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krogvold L et al. Detection of a low-grade enteroviral infection in the islets of langerhans of living patients newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 64, 1682–1687, doi: 10.2337/db14-1370 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laitinen OH et al. Coxsackievirus B1 is associated with induction of beta-cell autoimmunity that portends type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 63, 446–455, doi: 10.2337/db13-0619 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hotamisligil GS Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature 542, 177–185, doi: 10.1038/nature21363 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monroy A et al. Impaired regulation of the TNF-alpha converting enzyme/tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 proteolytic system in skeletal muscle of obese type 2 diabetic patients: a new mechanism of insulin resistance in humans. Diabetologia 52, 2169–2181, doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1451-3 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joya-Galeana J et al. Effects of insulin and oral anti-diabetic agents on glucose metabolism, vascular dysfunction and skeletal muscle inflammation in type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 27, 373–382, doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1185 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeFronzo RA Pathogenesis of type 2 (non-insulin dependent) diabetes mellitus: a balanced overview. Diabetologia 35, 389–397, doi: 10.1007/BF00401208 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mauvais-Jarvis F et al. A model to explore the interaction between muscle insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 49, 2126–2134, doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2126 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marzban L New insights into the mechanisms of islet inflammation in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 64, 1094–1096, doi: 10.2337/db14-1903 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donath MY, Boni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Halban PA & Ehses JA Cytokine production by islets in health and diabetes: cellular origin, regulation and function. Trends Endocrinol Metab 21, 261–267, doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.12.010 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butcher MJ et al. Association of proinflammatory cytokines and islet resident leucocytes with islet dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 57, 491–501, doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3116-5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eguchi K & Nagai R Islet inflammation in type 2 diabetes and physiology. J Clin Invest 127, 14–23, doi: 10.1172/JCI88877 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stone JH et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D’Addio F et al. Islet transplantation stabilizes hemostatic abnormalities and cerebral metabolism in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 37, 267–276, doi: 10.2337/dc13-1663 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Astorri E, Fiorina P, Gavaruzzi G, Astorri A & Magnati G Left ventricular function in insulin-dependent and in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients: radionuclide assessment. Cardiology 88, 152–155, doi: 10.1159/000177322 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lind M et al. Continuous Glucose Monitoring vs Conventional Therapy for Glycemic Control in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes Treated With Multiple Daily Insulin Injections: The GOLD Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 317, 379–387, doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19976 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta S et al. Factors Associated With Death in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson S et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 323, 2052–2059, doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fiorentino TV et al. Exenatide regulates pancreatic islet integrity and insulin sensitivity in the nonhuman primate baboon Papio hamadryas. JCI Insight 4, doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93091 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daniele G et al. The inflammatory status score including IL-6, TNF-alpha, osteopontin, fractalkine, MCP-1 and adiponectin underlies whole-body insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Diabetol 51, 123–131, doi: 10.1007/s00592-013-0543-1 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roder ME et al. Intact proinsulin and beta-cell function in lean and obese subjects with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 22, 609–614, doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.4.609 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matthews DR et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419, doi: 10.1007/BF00280883 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brandle M, Lehmann R, Maly FE, Schmid C & Spinas GA Diminished insulin secretory response to glucose but normal insulin and glucagon secretory responses to arginine in a family with maternally inherited diabetes and deafness caused by mitochondrial tRNA(LEU(UUR)) gene mutation. Diabetes Care 24, 1253–1258, doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1253 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data files are provided with this paper.