Abstract

Background

Myopia is a common refractive error, where elongation of the eyeball causes distant objects to appear blurred. The increasing prevalence of myopia is a growing global public health problem, in terms of rates of uncorrected refractive error and significantly, an increased risk of visual impairment due to myopia‐related ocular morbidity. Since myopia is usually detected in children before 10 years of age and can progress rapidly, interventions to slow its progression need to be delivered in childhood.

Objectives

To assess the comparative efficacy of optical, pharmacological and environmental interventions for slowing myopia progression in children using network meta‐analysis (NMA). To generate a relative ranking of myopia control interventions according to their efficacy. To produce a brief economic commentary, summarising the economic evaluations assessing myopia control interventions in children. To maintain the currency of the evidence using a living systematic review approach.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register), MEDLINE; Embase; and three trials registers. The search date was 26 February 2022.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of optical, pharmacological and environmental interventions for slowing myopia progression in children aged 18 years or younger. Critical outcomes were progression of myopia (defined as the difference in the change in spherical equivalent refraction (SER, dioptres (D)) and axial length (mm) in the intervention and control groups at one year or longer) and difference in the change in SER and axial length following cessation of treatment ('rebound').

Data collection and analysis

We followed standard Cochrane methods. We assessed bias using RoB 2 for parallel RCTs. We rated the certainty of evidence using the GRADE approach for the outcomes: change in SER and axial length at one and two years. Most comparisons were with inactive controls.

Main results

We included 64 studies that randomised 11,617 children, aged 4 to 18 years. Studies were mostly conducted in China or other Asian countries (39 studies, 60.9%) and North America (13 studies, 20.3%). Fifty‐seven studies (89%) compared myopia control interventions (multifocal spectacles, peripheral plus spectacles (PPSL), undercorrected single vision spectacles (SVLs), multifocal soft contact lenses (MFSCL), orthokeratology, rigid gas‐permeable contact lenses (RGP); or pharmacological interventions (including high‐ (HDA), moderate‐ (MDA) and low‐dose (LDA) atropine, pirenzipine or 7‐methylxanthine) against an inactive control. Study duration was 12 to 36 months. The overall certainty of the evidence ranged from very low to moderate.

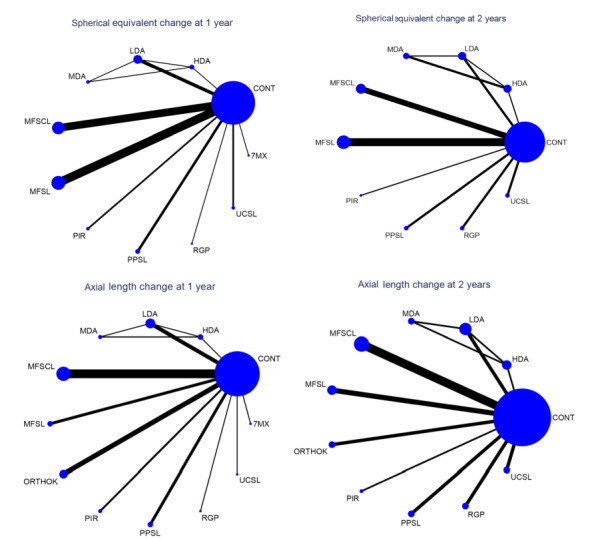

Since the networks in the NMA were poorly connected, most estimates versus control were as, or more, imprecise than the corresponding direct estimates. Consequently, we mostly report estimates based on direct (pairwise) comparisons below.

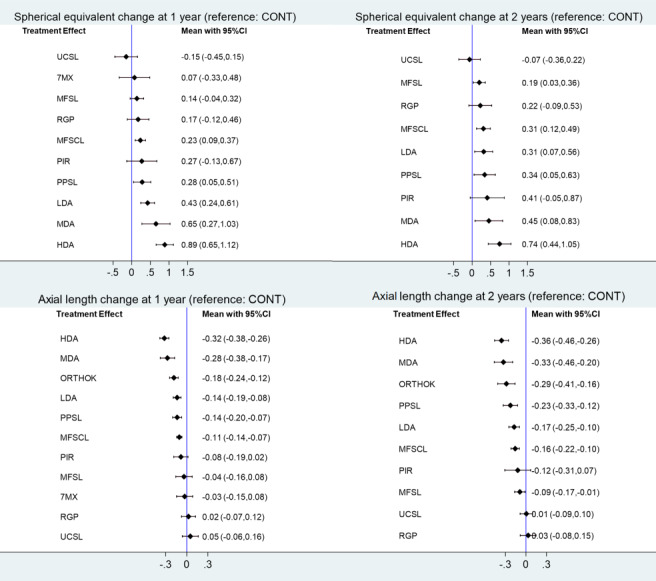

At one year, in 38 studies (6525 participants analysed), the median change in SER for controls was −0.65 D. The following interventions may reduce SER progression compared to controls: HDA (mean difference (MD) 0.90 D, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.62 to 1.18), MDA (MD 0.65 D, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.03), LDA (MD 0.38 D, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.66), pirenzipine (MD 0.32 D, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.49), MFSCL (MD 0.26 D, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.35), PPSLs (MD 0.51 D, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.82), and multifocal spectacles (MD 0.14 D, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.21). By contrast, there was little or no evidence that RGP (MD 0.02 D, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.10), 7‐methylxanthine (MD 0.07 D, 95% CI −0.09 to 0.24) or undercorrected SVLs (MD −0.15 D, 95% CI −0.29 to 0.00) reduce progression.

At two years, in 26 studies (4949 participants), the median change in SER for controls was −1.02 D. The following interventions may reduce SER progression compared to controls: HDA (MD 1.26 D, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.36), MDA (MD 0.45 D, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.83), LDA (MD 0.24 D, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.31), pirenzipine (MD 0.41 D, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.69), MFSCL (MD 0.30 D, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.41), and multifocal spectacles (MD 0.19 D, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.30). PPSLs (MD 0.34 D, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.76) may also reduce progression, but the results were inconsistent. For RGP, one study found a benefit and another found no difference with control. We found no difference in SER change for undercorrected SVLs (MD 0.02 D, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.09).

At one year, in 36 studies (6263 participants), the median change in axial length for controls was 0.31 mm. The following interventions may reduce axial elongation compared to controls: HDA (MD −0.33 mm, 95% CI −0.35 to 0.30), MDA (MD −0.28 mm, 95% CI −0.38 to −0.17), LDA (MD −0.13 mm, 95% CI −0.21 to −0.05), orthokeratology (MD −0.19 mm, 95% CI −0.23 to −0.15), MFSCL (MD −0.11 mm, 95% CI −0.13 to −0.09), pirenzipine (MD −0.10 mm, 95% CI −0.18 to −0.02), PPSLs (MD −0.13 mm, 95% CI −0.24 to −0.03), and multifocal spectacles (MD −0.06 mm, 95% CI −0.09 to −0.04). We found little or no evidence that RGP (MD 0.02 mm, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.10), 7‐methylxanthine (MD 0.03 mm, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.03) or undercorrected SVLs (MD 0.05 mm, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.11) reduce axial length.

At two years, in 21 studies (4169 participants), the median change in axial length for controls was 0.56 mm. The following interventions may reduce axial elongation compared to controls: HDA (MD −0.47mm, 95% CI −0.61 to −0.34), MDA (MD −0.33 mm, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.20), orthokeratology (MD −0.28 mm, (95% CI −0.38 to −0.19), LDA (MD −0.16 mm, 95% CI −0.20 to −0.12), MFSCL (MD −0.15 mm, 95% CI −0.19 to −0.12), and multifocal spectacles (MD −0.07 mm, 95% CI −0.12 to −0.03). PPSL may reduce progression (MD −0.20 mm, 95% CI −0.45 to 0.05) but results were inconsistent. We found little or no evidence that undercorrected SVLs (MD ‐0.01 mm, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.03) or RGP (MD 0.03 mm, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.12) reduce axial length.

There was inconclusive evidence on whether treatment cessation increases myopia progression. Adverse events and treatment adherence were not consistently reported, and only one study reported quality of life.

No studies reported environmental interventions reporting progression in children with myopia, and no economic evaluations assessed interventions for myopia control in children.

Authors' conclusions

Studies mostly compared pharmacological and optical treatments to slow the progression of myopia with an inactive comparator. Effects at one year provided evidence that these interventions may slow refractive change and reduce axial elongation, although results were often heterogeneous. A smaller body of evidence is available at two or three years, and uncertainty remains about the sustained effect of these interventions. Longer‐term and better‐quality studies comparing myopia control interventions used alone or in combination are needed, and improved methods for monitoring and reporting adverse effects.

Keywords: Child; Humans; Atropine; Atropine/therapeutic use; Myopia; Network Meta-Analysis; Refraction, Ocular; Refractive Errors

Plain language summary

Interventions to slow the progression of short‐sightedness in children

Key messages

• Medications such as atropine, given as eye drops, can slow the progression of short‐ or near‐sightedness (myopia) in children, and also reduce elongation of the eyeball due to myopia. Higher doses of atropine are most effective. We are uncertain about the effects of lower doses of atropine.

• Several treatments, including special types of lenses in eye glasses as well as contact lenses, may slow the progression of short‐sightedness, but their effect is still uncertain and there is insufficient information on the risk of unwanted effects.

• It is also unclear whether the reported benefit of medications or lenses on myopia progression is maintained over the years.

What is short‐sightedness?

Short‐sightedness (or near‐sightedness or myopia) means people struggle to see objects that are far away clearly, while objects that are near remain clear. It is very common worldwide, and affects more than half of children in China and South‐East Asia. Short‐sightedness may impair many aspects of life, including educational and occupational activities. Moreover, short‐sighted people have longer eyes, which means that the retina is stretched. This puts the eye at greater risk of eye diseases such as glaucoma, maculopathy and retinal detachment later in life.

How is short‐sightedness treated?

Although conventional eyeglasses or contact lenses are able to correct short sight, they do not slow its progression. A number of optical treatments (glasses and contact lenses) and medications are available that aim to slow the progression of short‐sightedness. But they need to be given in childhood, when short‐sightedness progresses most quickly. Medications such as atropine eye drops may be effective, but can cause increased sensitivity to glare and cause problems when reading, especially at higher doses. Special eyeglasses are also available, that include more than one focus power within the lens (multifocal or peripheral‐plus lenses). These can also be provided as soft contact lenses. Other contact lenses, called orthokeratology, aim to temporarily change the shape of the eye surface and are worn during sleep and removed during the day. Both soft contact lenses and orthokeratology may increase the risk of infections to the eye surface

What did we want to find out?

We aimed to find out whether medications used as eye drops, and special lenses in eyeglasses or contact lenses, can slow the progression of myopia, as well as the elongation of the eyeball. We also documented the risk of unwanted effects of such interventions.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that tested medications and lenses aiming to slow progression of short‐sightedness in children, compared with a control group or with other medications and lenses. The control group generally received a placebo (sham) treatment or single vision eye glasses or contact lenses.

What did we find?

• Higher doses of atropine may reduce the progression of short‐sightedness, but the effect of low‐dose atropine could be small and is uncertain.

• Based on short‐term studies, orthokeratology is the most effective of the optical treatments in slowing elongation of the eyeball. These lenses were often difficult to tolerate, however, with more than half of children not completing the treatment in some studies.

• Other types of contact lenses, known as multifocal soft contact lenses, may also reduce the progression of short‐sightedness, but, again, we remain uncertain about their beneficial effects.

• Unwanted effects associated with myopia control interventions were not consistently reported. Eye discomfort in bright light and blurred near vision were the most common treatment‐related unwanted effects in studies using atropine. Lower doses of atropine appear to have fewer unwanted effects.

• Although studies that tested contact lenses did not report any serious unwanted effects, it is unclear what the true rate of unwanted effects would be for children outside a research study or when wearing contact lenses for longer periods.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Most of the evidence came from studies conducted in ways that may have introduced errors into their results, and potential unwanted effects were not well reported. The majority of the studies followed participants up for 2 years or less and therefore there is insufficient evidence on whether incremental benefits are found over the years and whether the effects are sustained.

How up to date is the evidence?

This review is up‐to‐date to February 2022.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings 1: change in refractive error at 1 year .

| Interventions for myopia control in children: a living systematic review and network meta‐analysis | ||||

|

Population: children with progressive myopia (38 studies, 6525 participants in analyses) Interventions: optical and pharmacological Comparator: control (36 studies, 2846 participants). Control arms for optical interventions are either single vision spectacles or contact lenses. Placebo eyedrops were the usual comparator for pharmacological interventions Outcome: progression of myopia (difference in change in spherical equivalent refraction (SER)) at 1 year (dioptres) Setting: primary eye care Assumed control risk: median change in SER in control arms at 1 year −0.65D Equivalence criterion: difference in change in spherical equivalent less than 0.25 D | ||||

| Treatment (vs control) | Number of studies in the treatment arm (participants) | Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI). Direct estimates from pairwise MA | Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI). Estimates from NMA | Certainty of evidence |

| High‐dose atropine (≥ 0.5%) | 3 (512) | 0.90 (0.62 to 1.18) | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.12) | Moderatea |

| Moderate‐dose atropine (0.1% to < 0.5%) | 2 (254) | ‐ | 0.65 (0.27 to 1.03) | Moderatea |

| Low‐dose atropine (< 0.1%) | 4 (497) | 0.38 (0.10 to 0.66) | 0.43 (0.24 to 0.61) | Very lowb |

| Pirenzepine | 2 (210) | 0.32 (0.15 to 0.49) | 0.27 (−0.13 to 0.67) | Very lowb |

| 7‐methyxanthine | 1 (77) | 0.07 (−0.09 to 0.24) | 0.07 (−0.33 to 0.48) | Lowc |

| Multifocal soft contact lenses | 8 (712) | 0.26 (0.17 to 0.35) | 0.23 (0.09 to 0.37) | Very lowb |

| Rigid gas‐permeable contact lenses | 2 (178) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.10) | 0.17 (−0.12 to 0.46) | Very lowb |

| Peripheral plus spectacle lenses | 5 (480) | 0.51 (0.19 to 0.82) | 0.28 (0.05 to 0.51) | Very lowb |

| Multifocal spectacle lenses | 9 (729) | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.21) | 0.14 (−0.04 to 0.32) | Lowc |

| Undercorrected single vision spectacles | 2 (72) | −0.15 (−0.29 to 0.00) | −0.15 (−0.45 to 0.15) | Lowc |

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

|

Explanation Negative mean differences for changes in refractive error represent faster progression of myopia in the intervention group compared to progression in the control group. Measurement of refractive error is not an appropriate outcome in orthokeratology (ortho‐K) studies. Overnight wear of ortho‐K lenses flattens the central cornea and temporally reduces refractive error. It is therefore not possible to assess the true progression of refractive error without ceasing lens wear for a period of time to allow the cornea to return to its pre‐treatment state CI: confidence interval; MA: meta‐analysis; MD: mean difference; NMA: network meta‐analysis | ||||

Reasons for downgrade

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias, not downgraded for inconsistency since all studies show clinically important effects. b.Downgraded one level for risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency. cDowngraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision

In each case, downgrading due to risk of bias was due to concerns arising from the randomisation process and in the selection of the reporting of the results; downgrading for imprecision was due to a confidence interval that included small and clinically unimportant effects or optimal information size not met (using fewer than 400 participants as a 'rule of thumb'); downgrading for inconsistency was due to substantial heterogeneity.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings 2: change in refractive error at 2 years.

| Interventions for myopia control in children: a living systematic review and network meta‐analysis | ||||

|

Population: children with progressive myopia (26 studies, 4949 participants in the analysis) Interventions: optical and pharmacological Comparator: control (24 studies, 2282 participants). Control arms for optical interventions are either single vision spectacles or contact lenses. Placebo eyedrops were the usual comparator for pharmacological interventions Outcome: progression of myopia (difference in change in spherical equivalent refraction (SER)) at 2 years (dioptres) Setting: primary eye care Assumed control risk: median change in SER in control arms at 2 years −1.02 D Equivalence criterion: difference in change in spherical equivalent less than 0.25 D | ||||

| Treatment (vs control) | Number of studies in the treatment arm (participants) | Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI) Direct estimates from pairwise MA | Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI) Estimates from NMA | Certainty of evidence |

| High‐dose atropine (≥ 0.5%) | 2 (428) | 1.26 (1.17 to 1.36) | 0.74 (0.44 to 1.05) | Moderatea |

| Moderate‐dose atropine (0.1% to < 0.5%) | 2 (247) | ‐ | 0.45 (0.08 to 0.83) | Lowb |

| Low‐dose atropine (< 0.1%) | 2 (249) | 0.24 (0.17 to 0.31) | 0.31 (0.07 to 0.56) | Lowb |

| Pirenzepine | 1 (53) | 0.41 (0.13 to 0.69) | 0.41 (−0.05 to 0.87) | Lowb |

| Multifocal soft contact lenses | 5 (540) | 0.30 (0.19 to 0.41) | 0.31 (0.12 to 0.49) | Lowb |

| Rigid gas‐permeable contact lenses | 2 (154) | One study showed no difference and the other a beneficial effect | 0.22 (−0.09 to 0.53) | Very lowc |

| Peripheral plus spectacle lenses | 2 (188) | 0.34 (−0.08 to 0.76) | 0.34 (0.05 to 0.63) | Very lowc |

| Multifocal spectacle lenses | 8 (696) | 0.19 (0.08 to 0.30) | 0.19 (0.03 to 0.36) | Lowb |

| Undercorrected single vision spectacles | 2 (122) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.09) | −0.07 (−0.36 to 0.22) | Very lowc |

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

|

Explanation Negative mean differences (MDs) for changes in refractive error represent faster progression of myopia in the intervention group compared to progression in the control group. Measurement of refractive error is not an appropriate outcome in orthokeratology (ortho‐K) studies. Overnight wear of ortho‐K lenses flattens the central cornea and temporally reduces refractive error. It is therefore not possible to assess the true progression of refractive error without ceasing lens wear for a period of time to allow the cornea to return to its pre‐treatment state CI: confidence interval; MA: meta‐analysis; MD: mean difference; NMA: network meta‐analysis | ||||

Reasons for downgrade

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias, not downgraded for inconsistency since all studies show clinically important effects. bDowngraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision. cDowngraded one level for risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency

In each case, downgrading due to risk of bias was due to concerns arising from the randomisation process and in the selection of the reporting of the results; downgrading for imprecision was due to a confidence interval that included small and clinically unimportant effects or optimal information size not met (using fewer than 400 participants as a 'rule of thumb'); downgrading for inconsistency was due to substantial heterogeneity.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings 3: change in axial length at 1 year.

| Interventions for myopia control in children: a living systematic review and network meta‐analysis | ||||

|

Population: children with progressive myopia (36 studies, 6263 participants) in the analysis Interventions: optical and pharmacological Comparator: control (35 studies, 2732 participants). Control arms for optical interventions are either single vision spectacles or contact lenses. Placebo eyedrops were the usual comparator for pharmacological interventions Setting: primary eye care Outcome: difference in change in axial length at 1 year (mm) Assumed control risk: median change in axial length in control arms at 1 year 0.31 mm Equivalence criterion: difference in change in axial length less than 0.1 mm | ||||

| Treatment (vs control) |

Number of studies in the treatment arm (participants) |

Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI) Direct estimates from pairwise MA | Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI) Estimates from NMA | Certainty of evidence |

| High‐dose atropine (≥ 0.5%) | 3 (512) | −0.33 (−0.35 to −0.30) | −0.32 (−0.38 to −0.26) | Moderatea |

| Moderate‐dose atropine (0.1% to < 0.5%) | 1 (155) | ‐ | −0.28 (−0.38 to −0.17) | Moderatea |

| Low‐dose atropine (< 0.1%) | 4 (497) | −0.13 (−0.21 to −0.05) | −0.14 (−0.19 to −0.08) | Very lowb |

| Pirenzepine | 2 (210) | −0.10 (−0.18 to −0.02) | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.02) | Very lowb |

| 7‐methylxanthine | 1 (35) | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.03) | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.08) | Lowc |

| Orthokeratology | 7 (402) | −0.19 (−0.23 to −0.15) | −0.18 (−0.24 to −0.12) | Moderatea |

| Multifocal soft contact lenses | 8 (712) | −0.11 (−0.13 to −0.09) | −0.11 (−0.14 to −0.07) | Lowc |

| Rigid gas‐permeable contact lenses | 2 (176) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.10) | 0.02 (−0.07 to 0.12) | Lowc |

| Peripheral plus spectacle lenses | 3 (340) | −0.13 (−0.24 to −0.03) | −0.14 (−0.20 to −0.07) | Very lowb |

| Multifocal spectacle lenses | 4 (445) | −0.06 (−0.09 to −0.04) | −0.04 (−0.16 to 0.08) | Lowc |

| Undercorrected single vision spectacles | 1 (47) | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.11) | 0.05 (−0.06 to 0.16) | Lowc |

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

|

Explanation For the measurement of changes in axial length, negative mean differencess for changes in axial length represent faster axial elongation in the control group compared to the intervention group. CI: confidence interval; MA: meta‐analysis; MD: mean difference; NMA: network meta‐analysis | ||||

Reasons for downgrade

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias. bDowngraded one level for risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency. cDowngraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision.

In each case, downgrading due to risk of bias was due to concerns arising from the randomisation process and in the selection of the reporting of the results; downgrading for imprecision was due to a confidence interval that included small and clinically unimportant effects or optimal information size not met (using fewer than than 400 participants as a 'rule of thumb'); downgrading for inconsistency was due to substantial heterogeneity

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings 4: change in axial length at 2 years.

| Interventions for myopia control in children: a living systematic review and network meta‐analysis | ||||

|

Population: children with progressive myopia (21 studies, 4169 participants in the analysis) Interventions: optical and pharmacological Comparator: control (20 studies, 1894 participants). Control arms for optical interventions are either single vision spectacles or contact lenses. Placebo eyedrops are the usual comparator for pharmacological interventions. Outcome: median change in axial length in control arms at 2 years Setting: primary eye care Assumed control risk: change in axial length at 2 years 0.56 mm Equivalence criterion: difference in change in axial length less than 0.1 mm | ||||

| Treatment (vs control) |

Number of studies in the treatment arm (participants) |

Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI) Direct estimates from pairwise MA | Corresponding intervention risk MD (95%CI) Estimates from NMA | Certainty of evidence |

| High‐dose atropine (≥ 0.5%) | 2 (428) | −0.47 (−0.61 to −0.34) | −0.36 (−0.46 to −0.26) | Moderatea |

| Moderate‐dose atropine (0.1% to < 0.5%) | 1 (144) | ‐ | −0.33 (−0.46 to −0.20) | Moderatea |

| Low‐dose atropine (< 0.1%) | 2 (249) | −0.16 (−0.20 to −0.12) | −0.17 (−0.25 to −0.10) | Lowb |

| Orthokeratology | 2 (49) | −0.28 (−0.38 to −0.19) | −0.29 (−0.41 to −0.16) | Moderatea |

| Multifocal soft contact lenses | 5 (540) | −0.15 (−0.19 to −0.12) | −0.16 (−0.22 to −0.10) | Moderatea |

| Rigid gas‐permeable contact lenses | 2 (154) | 0.03 (−0.05 to 0.12) | 0.03 (−0.08 to 0.15) | Lowb |

| Peripheral plus spectacle lenses | 2 (188) | −0.20 (−0.45 to 0.05) | −0.23 (−0.33 to −0.12) | Very lowc |

| Multifocal spectacle lenses | 3 (404) | −0.07 (−0.12 to −0.03) | −0.09 (−0.17 to −0.01) | Lowb |

| Undercorrected single vision spectacles | 2 (122) | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.09 to 0.10) | Lowb |

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High‐certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate‐certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low‐certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low‐certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||

|

Explanation For the measurement of changes in axial length, negative MDs for changes in axial length represent faster axial elongation in the control group compared to the intervention group CI: confidence interval; MA: meta‐analysis; MD: mean difference; NMA: network meta‐analysis | ||||

Reasons for downgrade

aDowngraded one level for risk of bias. bDowngraded one level for risk of bias and imprecision. cDowngraded one level for risk of bias, imprecision and inconsistency.

In each case, downgrading due to risk of bias was due to concerns arising from the randomisation process and in the selection of the reporting of the results; downgrading for imprecision was due to a confidence interval that included small and clinically unimportant effects or optimal information size not met (using fewer than 400 participants as a 'rule of thumb'); downgrading for inconsistency was due to substantial heterogeneity.

Background

Description of the condition

Myopia, or short‐ or near‐sightedness, is a common refractive anomaly of the eye that occurs when parallel rays of light are brought to a focus in front of the retina with accommodation at rest, causing distant objects to appear blurred and near objects to remain clear (Morgan 2012). Myopia most often results from the eyeball being too long (i.e. there is excessive axial elongation), but can also occur when the image‐forming structures of the eye are too strong (Flitcroft 2019).

The prevalence of myopia shows significant age, ethnic and regional variation (Rudnicka 2016). Currently, 30% to 50% of adults in the USA and Europe have myopia (Dolgin 2015). Myopia is already reaching 'epidemic' proportions in children and young adults in urban areas of East and South East Asia, with over 80% of children being myopic by the time they complete their high school education (Dolgin 2015). If current trends continue, it is estimated that by 2050 there will be approximately 5 billion (5000 million) people with myopia (i.e. about 50% of the world's population), with around 10% having high myopia (when defined as a spherical equivalent of −5.00 dioptres (D) or worse) (Holden 2016).

The aetiology of myopia involves a complex interaction between environmental and genetic factors. Although genetic inheritance is a well‐established predisposing factor for myopia, genetic factors cannot explain the rapidly rising prevalence of the condition (Williams 2019). A Mendelian randomisation study, using the UK Biobank cohort, provided strong evidence for the cumulative effect of additional years in education on myopia development (Mountjoy 2018). Mendelian randomisation is a statistical approach that uses genetics to provide information about the relationship between an exposure and outcome. This study estimated that for each additional year in education, myopic spherical equivalent increased by −0.27 D. Evidence from a number of observational studies further supports the causal association between environmental and social factors and myopia development (Morgan 2018).

Epidemiological studies have shown that myopia is an established risk factor for a number of ocular pathologies, including cataract, glaucoma and retinal detachment (Flitcroft 2012). Although myopia‐related complications can occur irrespective of age and degree of myopia (Dhakal 2018), the excessive axial elongation associated with higher degrees of myopia causes biomechanical stretching of the outer coat of the eye, increasing the risk of sight‐threatening pathologies such as posterior staphyloma and myopic maculopathy (Saw 2005; Verkicharla 2015). A meta‐analysis of population studies reporting blindness and visual impairment due to myopic maculopathy (Fricke 2018), estimated that in 2015, approximately 10 million people had visual impairment due to myopic macular degeneration, of whom three million were blind. Although the sight‐threatening pathologies associated with myopia usually occur later in life, the underlying myopia develops during childhood and therefore interventions to reduce the progression of myopia have the potential to reduce future visual impairment.

Description of the intervention

Most cases of myopia develop during childhood and the prevalence of myopia begins to increase noticeably after the age of six years (McCullough 2016). Progression rates vary significantly, with rates in Asian children being approximately 0.20 D per year faster than their age‐matched European counterparts (Donovan 2012). Since myopia tends to stabilise in late adolescence, interventions to slow myopia progression need to be delivered in childhood.

Interventions to slow progression of myopia can be grouped into three broad categories: optical, pharmacological and environmental (Wildsoet 2019). Optical interventions include a variety of spectacle and contact lens designs. Spectacles are the least invasive and most accessible method for potentially slowing myopia progression. Spectacle options include refractive under‐correction, bifocal and progressive addition lenses and, more recently, specialised 'myopia control' designs. Soft multifocal and approved myopia control contact lenses are increasingly being used for myopia management in children (Efron 2020). Centre‐distance soft multifocal lens designs incorporate a central zone that contains the distance refractive correction, with peripheral regions of the lens having relatively increased positive power (myopic defocus). This is achieved by either a gradual increase in power towards the periphery or using concentric peripheral zones of alternating myopic defocus and distance correction. Orthokeratology involves the use of specialised rigid contact lenses that are worn during sleep to change the topography of the cornea to reduce myopic refractive error and also manipulate peripheral retinal defocus. Safety remains a concern because of the greater risk of sight‐threatening microbial keratitis with overnight wear compared with daily contact lens wear modalities (Dart 2008).

The most commonly used topical pharmacological intervention for myopia control is atropine, a non‐selective muscarinic antagonist, which has been widely used in clinical trials in concentrations ranging from 0.01% to 1.0%. Although higher atropine concentrations have been shown to be effective in retarding myopia progression in children, the higher incidence of side effects with higher doses, including cycloplegia (inhibition of accommodation) and pupil dilation (which causes blur for near vision and photophobia) limits its use. Furthermore, a rebound effect (involving more rapid myopia progression) after discontinuation of therapy is more pronounced with higher concentrations of atropine (Chia 2014). More recent studies have evaluated the efficacy of lower concentrations to reduce side effects and lessen the likelihood of rebound. The results of these studies have led to a renewed interest in the clinical application of low‐dose atropine (i.e. 0.01% to 0.05%) for myopia control (Wu 2019). Other pharmacological agents that have been evaluated for myopia control include topical tropicamide, cyclopentolate and pirenzipine (a selective M1 muscarinic antagonist) and the oral adenosine antagonist, 7‐methylxanthine.

Evidence that more time spent on near work activities is associated with higher odds of developing myopia (Huang 2015), and the observation that increased time spent outdoors is protective against myopia, after adjusting for near work, parental myopia and ethnicity (Rose 2008), have raised the possibility that environmental or behavioural interventions could be effective for myopia control. Trials of school‐based programmes that promote outdoor activities, conducted in East Asia, have reported a lower incidence of myopia onset but have limited impact on progression following onset of myopia (Dhakal 2022).

How the intervention might work

Animal studies have shown that optically‐induced changes to the effective refractive status of the eye can regulate eye growth and influence refractive development (Troilo 2019). Specifically, the observation that imposed relative myopic defocus (image focused in front of the retina) can slow axial elongation has been the impetus for the development of novel multifocal spectacles and contact lenses that provide clear central vision, whilst at the same time presenting myopic defocus over a large proportion of the visual field. The critical area ratio required for these simultaneous competing defocus signals to dominate eye growth is currently unclear. However, the relative treatment effects reported for different optical treatment regimens suggest that there appears to be an eccentricity‐dependent decrease in the efficacy of myopic defocus beyond the near periphery (Smith 2014; Smith 2020).

Orthokeratology involves corneal reshaping lenses that are worn overnight to flatten the central cornea and reduce its dioptric power. The geometry of these lenses also creates a corneal profile that produces relative myopic defocus.

The precise mechanism by which anti‐muscarinic agents reduce myopic progression is not fully understood. A non‐accommodative mechanism is thought to be the most likely, and alternative targets have been proposed, including eye growth regulatory pathways that arise in the retina and are relayed to the sclera via the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid (McBrien 2013; Upadhyay 2020).

The protective effect of increased time outdoors on myopia development is thought to be related to the higher light intensity of sunlight and possibly its spectral composition (French 2013). Light levels have been shown to influence refractive development in animal models (Smith 2012). Higher light intensities stimulate retinal dopamine production, which is thought to inhibit axial elongation (Feldkaemper 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

As a result of its increasing global prevalence and association with sight‐threatening pathologies, myopia is emerging as a major public health concern. Myopia is predicted to affect almost half of the world’s population by 2050, and the pathologic consequences of high myopia increase the risk of irreversible visual impairment and blindness. There has been considerable interest in the development of strategies to delay the onset of myopia and slow its progression. Myopia control interventions are increasingly being used in routine clinical practice (Efron 2020; Wolffsohn 2016). Evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) indicates that the progression of myopia can be slowed by different interventions, although treatment efficacy is highly variable.

There is a broad consensus that the primary endpoints for judging efficacy in clinical trials of myopia control interventions should include change in axial length, in addition to change in refractive error (Brennan 2020; Walline 2018; Wolffsohn 2019). Myopia development and progression usually occur due to abnormal axial elongation. Therefore, axial length may be a better predictor of future progression and consequent risk of posterior pole complications (Brennan 2020). In terms of a minimal clinically important difference of the key efficacy outcomes in myopia control studies, an expert panel concluded that a mean difference between intervention groups of 0.25 D per year would be regarded as clinically significant (i.e. 0.75 D over the course of a three‐year study) (Walline 2018). This would correspond to a difference in axial length of approximately 0.3 mm.

An updated Cochrane systematic review, published in January 2020 (Walline 2020), evaluated the efficacy of a number of interventions, including spectacles, contact lenses and pharmaceutical agents, for slowing the progression of myopia in children. Walline 2020 concluded that topical anti‐muscarinic medication was effective in slowing myopia progression. Multifocal lenses, either spectacles or contact lenses, also conferred a small benefit. Although the update was published in 2020, the review only included evidence published up to the end of 2018. In this rapidly moving field, the results of additional important trials have subsequently been reported.

Eye care professionals often find it difficult to assimilate potentially conflicting evidence to inform their clinical decision‐making (Douglass 2020). It is therefore important that practitioners can access high‐quality and up‐to‐date evidence to inform practice. Moreover, parents of myopic children also need reliable information to help them to understand and interpret research findings. Given the large number of different interventions available for myopia control and the large number of completed and ongoing RCTs on this topic, there is an urgent need to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of different interventions. A network meta‐analysis (NMA) offers an advantage over a standard pairwise meta‐analysis in that it provides both direct comparisons of individual trials and indirect comparisons not directly evaluated in trials across a network of studies, thus generating the comparativeness of all interventions in a coherent manner. A NMA can also provide relative rankings of interventions to inform clinical decision‐making.

There are significant resource implications associated with myopia for both individuals and healthcare systems. This includes both corrected and uncorrected myopic refractive error. Lim 2009 estimated the mean direct costs of managing myopia in school‐aged children in Singapore. These costs included optometrist visits, spectacles, contact lenses and travel costs. The mean cost was estimated as USD 148 (median SGD 83.33) per year in 2006. In addition, Zheng 2013 estimated the lifetime costs for a person with myopia over an 80‐year lifespan to be USD 17,020 in 2011. There are also associated costs and quality‐of‐life impacts associated with uncorrected refractive error. Tahhan 2013 found a significant reduction in health state utility (a preference‐based quality‐of‐life measure) associated with uncorrected refractive error. Fricke 2012 estimated that the direct costs of correcting all cases of uncorrected refractive error globally would be approximately USD 28 billion (USD 28,000 million; price year not stated). Given these cost estimates, understanding the current evidence base for myopia control is key for both individuals and healthcare decision‐makers.

We plan to maintain this review as a living systematic review. This will involve searching the literature every six months and incorporating new evidence as it becomes available. This approach is appropriate for this review since it addresses an important clinical topic and there is currently significant uncertainty as to the most effective intervention. It is therefore important that consumers and healthcare providers have access to the most up‐to‐date evidence to make informed decisions. The review authors are aware of several relevant ongoing trials that will be important to incorporate in a timely manner.

Objectives

To assess the comparative efficacy of optical, pharmacological and environmental interventions for slowing myopia progression in children using network meta‐analysis (NMA). To generate a relative ranking of myopia control interventions according to their efficacy. To produce a brief economic commentary, summarising the economic evaluations assessing interventions for myopia control in children. To maintain the currency of the evidence using a living systematic review approach.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of optical, pharmacological and environmental interventions used alone or in combination for slowing the progression of myopia in children.

Types of participants

This review considered studies that included children 18 years old and younger. We excluded studies in which the majority of participants were older than 18 years at the start of the study. We also excluded studies that included participants with spherical equivalent myopia less than −0.50 D at baseline. The spherical equivalent is calculated by the sum of the spherical power plus half the cylindrical power of the refractive error.

We included studies that compared interventions of interest and reported having measured the relevant outcomes, irrespective of whether data for the outcomes were available.

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared any of the interventions listed below with a control group, or with each other. For the purposes of the analysis, we defined a control group as a placebo intervention or single vision spectacles or contact lenses.

Undercorrection of myopia with single vision spectacle lenses

Multifocal (bifocal or progressive addition) spectacle lenses, peripheral defocus spectacle lenses

Multifocal soft contact lenses (MFSCL; concentric ring or progressive designs), rigid gas‐permeable contact lenses or corneal reshaping (orthokeratology) contact lenses

Atropine (stratified according to dosing regime as high (≥ 0.5%), moderate (0.1% to < 0.5%) and low (< 0.1%)

Other pharmaceutical agents (e.g. pirenzepine, 7‐methylxanthine)

Environmental interventions (e.g. time spent outdoors, modifications to the performance of near work)

Types of outcome measures

Critical outcomes

Progression of myopia

Progression of myopia was assessed by:

mean change in refractive error (spherical equivalent in D) from baseline for each year of follow‐up and measured by any method (e.g. objective or subjective refraction); and

mean change in axial length for each year of follow‐up in millimetres (mm) from baseline for each year of follow‐up and measured by any method (e.g. ultrasound or optical biometry).

Change in refractive error and axial length following cessation of treatment ('rebound')

Rebound was evaluated when children in the treatment group were switched to the control treatment and then followed for a minimum period of one year.

Important outcomes

Risk of adverse events

We described adverse events relating to the interventions as reported in the included studies, irrespective of severity. These included but were not limited to blurred vision, photophobia, hypersensitivity reactions, corneal infiltrative events and infections. In studies that graded clinical signs using standard anterior eye grading scales from normal to severe, we recorded the number of clinically significant signs (grade 3 or 4) that would usually require a clinical action.

Where data were available we documented withdrawals due to adverse events and number of 'serious' events.

Quality of life

We documented vision‐related or health‐related quality of life when reported, measured by any validated questionnaire (e.g. National Eye Institute (NEI) Visual Function Questionnaire 25 (NEI VFQ‐25), or EuroQol questionnaire, EQ‐5D).

Treatment adherence

Studies evaluated adherence with the prescribed treatment regimen using a variety of compliance measures, including daily wearing time with contact lenses and spectacle interventions as reported by parents or children, or both, or the proportion of participants in pharmacological studies following the required dosing regime.

Follow‐up

We have reported outcomes at one year, two years and as available for the duration of the study. We imposed no restrictions based on the length of follow‐up.

Brief economic commentary

We present evidence regarding relevant economic evaluations, as a brief economic commentary.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist searched the electronic databases below for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no restrictions to language or date of publication. Given the similarity in the PICO and corresponding search strategies between the current review and a previous Cochrane Review on interventions for myopia control in children (Walline 2020), and the likelihood that studies included in Walline 2020 would meet the inclusion criteria for this review, we ran the search for the current review in parallel with the search strategy used by Walline 2020 up to the search date for the earlier review (26 February 2019) and removed duplicates. We combined the search results with all records identified up to 4 February 2022.

We did not perform the generic search described in Electronic searches for adverse events, however we added a filter to the search strategy to identify systematic reviews of adverse events associated with myopia control interventions. We compared the findings of these reviews to the adverse events reported in the studies included in the current review.

In addition to these searches we carried out a MEDLINE and Embase search using economic search filters to specifically identify economic studies.

We have developed this review as a living systematic review, and we will re‐run the searches on a six‐monthly basis.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register; 2022, Issue 2) in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 1)

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 26 February 2022; Appendix 2)

MEDLINE Ovid ‐ economic search (1946 to 26 February 2022; Appendix 3)

MEDLINE Ovid ‐ adverse events (1946 to 26 February 2022; Appendix 4)

Embase Ovid (1980 to 26 February 2022; Appendix 5)

Embase Ovid ‐ economic search (1980 to 4 February 2022; Appendix 6)

Embase Ovid ‐ adverse events (1980 to 26 February 2022; Appendix 7)

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch) (Appendix 8)

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; Appendix 9)

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp; Appendix 10)

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of identified study reports to identify additional studies. We also contacted the principal investigators of included studies for details of other potentially relevant studies not identified by the electronic searches, and of recently completed or ongoing studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The Information Specialist at Cochrane Eyes and Vision downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved from the electronic searches to EndNote (Endnote X9 2013) and removed duplicates before uploading to Covidence. Two review authors (from JGL, RS, BH, RD, PV) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the search results based on the eligibility criteria stated above. We categorised Abstracts for inclusion as 'Yes', 'Maybe' or 'No'. We obtained the full text of articles for the studies categorised as 'Maybe' and 'Yes', and reassessed them for final eligibility. After examining the full text, we labelled studies as 'include' or 'exclude'. Studies selected as 'exclude' by both authors were excluded from the review. We documented the reasons for exclusion. We resolved any screening discrepancies through discussion and, if necessary, through consultation with a third review author. One review author (AK) screened the economic search results.

Living systematic review considerations

We plan to screen any new citations retrieved by the six‐monthly searches immediately.

Data extraction and management

For eligible studies, two review authors independently extracted the data. We contacted the authors of the original reports to obtain further details if the data reported were unclear or incomplete. We exported the collected data into Review Manager Web (RevMan Web) (RevMan Web 2022). We extracted the following study characteristics.

Methods: study design, number and location of study centre(s), date of study and total duration

Participants: inclusion and exclusion criteria, number randomised, number lost to follow‐up or withdrawn, number analysed, mean age and standard deviation (SD), age range, gender

Interventions: description of intervention and comparator

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported. Unit of analysis

Notes: funding for study and conflicts of interest of study authors

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Pairs of review authors (from JGL, BH, RS, RD, PV, SM, DL) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies for all outcomes using the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) 22 August 2019 version, described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022a). RoB 2 covers five domains of bias:

bias arising from the randomisation process;

bias due to deviations from intended interventions;

bias due to missing outcome data;

bias in measurement of the outcome; and

bias in selection of the reported result.

These domain‐level judgements provide the basis for an overall risk of bias judgement for the specific outcome being assessed. The response options for an overall risk of bias judgement in RoB 2 are the same as for individual domains (i.e. 'low risk of bias'; 'some concerns'; 'high risk of bias'). The following criteria were adopted:

Low risk of bias: low risk of bias for all domains;

Some concerns: 'some concerns' in at least one domain, but not at high risk of bias for any domain;

High risk of bias: high risk of bias in at least one domain or the study is judged to have some concerns for multiple domains in a way that substantially lowers confidence in the result.

To implement RoB 2 assessments we used the Excel tool available at https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2.

We did not include cluster‐randomised trials. In the case of cross‐over trials, we only used data from the first phase prior to the cross over and therefore used the version of the tool for parallel trials. Should cluster‐randomised and cross‐over trials be included in future updates of the review, we will use the versions of RoB 2 with additional considerations for these designs.

For all outcomes we assessed the effect of assignment to intervention (the intention‐to‐treat effect).

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to this published protocol and have reported any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of the review.

Measures of treatment effect

We used mean differences (MDs) as the measure of treatment effect for the critical outcome 'progression of myopia', that is, difference in mean change in refractive error (SER) and axial length from baseline at each year of follow‐up.

Unit of analysis issues

When studies randomised only one eye per participant, the unit of analysis was the individual eye (participant). When studies randomised both eyes from the same participant (either to the same or different interventions), we analysed data adjusted for clustering or paired‐eye design. In the NMA, we accounted for the correlation between the effect sizes derived from the same study.

In multiple‐arm trials, to overcome a unit‐of‐analysis error for a study that could contribute multiple, correlated data, we combined groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison.

If we identify cluster‐RCTs in future updates, we will include them in meta‐analyses directly, where the sample size has been adjusted for clustering. We will combine them with the results from individual studies if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of the intervention and the unit of randomisation is considered to be unlikely. If studies present outcomes at individual level (i.e. a unit of analysis error), we will use established methods to adjust for clustering by calculating an effective sample size by dividing the original sample size by the design effect. This can be calculated from the average cluster size and the intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC). Where the ICC is unknown, we will use an estimation from similar trials (Higgins 2022b).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing outcome data. If we did not receive a response within eight weeks, we analysed the studies based on available data. We used the RevMan calculator to calculate missing standard deviations using other data from the study (e.g. confidence intervals) based on methods outlined in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2022).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity for each pairwise meta‐analysis by comparing the characteristics of included studies and by visual inspection of forest plots. We assessed statistical heterogeneity quantitatively for pairwise comparisons using the values of the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We interpreted I2 statistic values according to Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2022), as follows:

0% to 40% may not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% represents considerable heterogeneity.

For the NMA, we assumed a common estimate for the heterogeneity variance across the different comparisons. The assessment of statistical heterogeneity was based on the magnitude of the heterogeneity variance parameter (Tau2) estimated from the NMA models.

Assessment of statistical inconsistency

Local approaches for evaluating inconsistency

To evaluate the presence of inconsistency locally, we used the node splitting approach (Dias 2010), which assesses the agreement between direct and indirect evidence for each treatment comparison.

Global approaches for evaluating inconsistency

To check the assumption of consistency across the entire network, we used the 'design by treatment' interaction model (White 2015). This method accounts for different sources of inconsistency that can occur when studies with different designs are incorporated into the network (e.g. two‐arm trials versus multi‐arm trials), as well as inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence.

Assessment of reporting biases

If there are sufficient studies in future updates, we plan to run network meta‐regression models to detect associations between study size and effect size.

Data synthesis

We initially carried out standard pairwise meta‐analyses to combine outcome data using random‐effects models in RevMan Web. For comparisons with three or fewer trials, we used a fixed‐effect model. We combined change from baseline data in meta‐analyses with mean outcome data using the generic inverse variance (unstandardised) MD method, as outlined in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Interventions (Deeks 2022). In the case of substantial clinical, methodological or statistical heterogeneity, we generally did not attempt to combine data from individual trials but reported study results separately, however, subtotals were included in some analyses when presenting subgroups with varying degrees of heterogeneity.

For cross‐over trials we only extracted data from the first phase prior to cross over.

We conducted a NMA using the network suite of programs available in STATA (http://www.stata.com) for myopia progression, as defined by difference in change in SER and axial length at 12 and 24 months, using random‐effects multivariate models (Chaimani 2013; Chaimani 2015; White 2015). An important concept in NMA is 'transitivity', which implies that the distribution of effect modifiers is similar across all sources of direct evidence. The statistical manifestation of transitivity is consistency, which refers to the statistical agreement between the direct and indirect sources of evidence. We checked for consistency in the network both locally (node‐splitting approach) and globally (design by treatment model).

We assumed a common heterogeneity across all comparisons in the network. We used te surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) to rank the interventions for all available outcomes. SUCRA values range from 0% to 100%. The higher the SUCRA value (i.e. the closer to 100%), the greater the probability of an intervention ranking best. (Chaimani 2015; Salanti 2012).

In the primary NMA, we considered MFSCL, rigid gas‐permeable lenses and orthokeratology lenses as separate nodes. For spectacle lens interventions, there were separate nodes for undercorrected single vision spectacle lenses, multifocal spectacle lenses and peripheral plus spectacle lenses. We considered each pharmacological intervention as a separate node regardless of the dose. We did not anticipate a strong dose‐response effect except for atropine. We grouped atropine according to dosing regime as high (≥ 0.5%), moderate (0.1 % to < 0.5%) and low (< 0.1%). We grouped all control arms (single vision spectacle lenses, single vision contact lenses, placebo eyedrops or no treatment) into a single node.

When we were unable to perform a meta‐analysis, we undertook a narrative synthesis following guidance in Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (McKenzie 2022b). Specifically, we presented the effect estimates in structured tables and provided a descriptive summary of the range and distribution of the observed effects. In particular, we noted the direction of effects and whether these were consistent in the individual studies.

Brief economic commentary

Following the search outlined in the Search methods for identification of studies, we developed a brief economic commentary to summarise the availability and principal findings of the full economic evaluations assessing interventions for myopia control in children as outlined in Chapter 20 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Aluko 2022). This brief economic commentary was planned to encompass full economic evaluations (i.e. cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses and cost‐benefit analyses) conducted as part of a single empirical study, such as a RCT, a model based on a single such study or a model based on several such studies.

Living systematic review considerations

Whenever we identify new evidence in future updates (i.e. new studies, data, or other information) that is relevant to the review, we will extract the data and assess risk of bias, as appropriate. We will wait until the accumulating evidence changes one or more of the following components of the review before incorporating it and re‐publishing the review.

The findings of one or more outcomes (e.g. clinically important change in size or direction of effect)

Credibility (e.g. change in the overall confidence in the effect estimates for critical outcomes)

We will not use formal sequential meta‐analysis approaches for updated meta‐analyses.

Methods for future updates

We will review the scope and methods of this review annually in light of potential changes in the topic area or in evidence available for inclusion in the review. Each year, we will consider the necessity for the review to be a living systematic review by assessing ongoing relevance of the question to decision‐makers and by determining whether uncertainty is ongoing in the evidence and whether further relevant research is likely.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed predefined subgroup analyses for types of intervention modalities (i.e. spectacle and contact lens designs, and dose of particular pharmaceutical interventions (e.g. low‐, moderate‐ and high‐dose atropine)). There were insufficient data to carry out other proposed subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned a sensitivity analysis on the exclusion of studies that we judged to be at high risk of bias or to raise some concerns in at least one domain of RoB 2. However, since we judged almost all the included studies at high risk of bias or with some concerns we did not seek to conduct a sensitivity analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We planned to follow methods presented in Yepes‐Nunez 2019 to prepare summary of findings tables for the NMA, however because the network was not well‐connected, we primarily based our comparisons on direct evidence from classical pairwise meta‐analyses, except for moderate‐dose atropine. We prepared summary of findings tables for progression of myopia at one and two years, with separate tables for change in spherical equivalent and change in axial length.

Evaluating confidence in the evidence

Instead of the planned CINeMA framework for evaluating confidence in the domains (Nikolakopoulou 2020; Salanti 2014) we summarised four levels of confidence for each relative treatment effect, corresponding to the usual GRADE approach: very low, low, moderate, or high (Schünemann 2022). In fact, because most evidence was direct versus control in NMAs, we used NMA estimates only when direct evidence was not available.

Results

Description of studies

We considered that all studies that met the inclusion criteria for Walline 2020 would potentially meet the inclusion criteria for the current review.

Results of the search

The searches performed by Walline 2020 to 26 February 2020 identified 41 studies with 74 ongoing studies and 25 studies awaiting classification. Updated electronic searches for the current review identified a further 1473 potentially eligible studies after removal of duplicates. We independently screened these studies for inclusion. We discarded 1290 citations and examined the full texts of the remaining 183 records. In total, we included 64 studies (reported in 225 records) and two studies published as conference abstracts are awaiting classification (for a full description see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

The economic search was carried out on 4 February 2022 and yielded 80 studies that were screened by AK. No studies met the inclusion criteria.

A search for systematic reviews of adverse events was carried out on 8 July 2022 and yielded 79 studies. These were screened, and we discuss relevant reviews in Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews.

For a summary of the screening process, see the study flow diagram (Figure 1; Liberati 2009).

1.

Study design

Sixty‐one studies used a parallel‐group design and three studies used a cross‐over design (Anstice 2011; Fujikado 2014; Hasebe 2008). The median sample size was 150 (range 24 to 660). Most participants were recruited from academic clinic settings, hospitals and in a few cases from private optometry or ophthalmology practices. The studies took place in China or other Asian countries (39 studies, 60.9%), North America (13 studies, 20.3%), Europe (7 studies, 10.9%), Australasia (2 studies, 3.1%), Israel (1 study, 1.6%) and Ghana (1 study, 1.6%); one multicentre study recruited participants in both Europe and Asia (1 study, 1.6%).

Fifty‐seven studies (89%) compared one or more myopia control interventions against a placebo intervention (generally single vision spectacles or contact lenses for optical interventions, and placebo or no treatment for pharmacological interventions). Four studies included a combined intervention group compared with control (Han 2019; MIT Study 2001; Schwartz 1981), and eight studies compared single or combined interventions with each other (ATOM 2 Study 2012; Cui 2021; Guo 2021; Kinoshita 2020; Shih 1999; Swarbrick 2015; Tan 2020; Zhao 2021).

Twenty‐two (34.4%) of the studies were of 12‐month duration, five studies(7.8%) had a duration of 18 to 20 months, 25 (39.1%) studies were 24 months, 11 (17.2%) up to 36 months and only one reported data over 36 months (Zhu 2021).

Seven studies were conducted before the year 2000 (Fulk 1996; Houston Study 1987; Jensen 1991; Pärssinen 1989; Schwartz 1981; Shih 1999; Yen 1989). Of the 49 studies that declared a source of funding, 19 (38.8%) were funded by the optical or pharmaceutical industry.

Characteristics of the participants

The review included 64 studies that randomised a total of 11,617 children, aged between 4 and 18 years, with a pooled mean age of 10.35 (range 7.6 to 14.0) years and 48% of participants were male. In the 58 studies that documented the level of myopia for inclusion, all but five studies recruited low to moderate myopes of −6.00 D or less; the other five studies included participants with higher levels of myopia up to −8.75 D (Charm 2013; Garcia‐del Valle 2021; Lyu 2020; Shih 1999; Zhu 2021). Most studies adopted an upper astigmatism limit of 1.00 D or 1.50 D. Three studies specifically recruited myopes with both myopia and near esophoria (Fulk 1996; Fulk 2002; STAMP Study 2012). One study selectively recruited participants with anisomyopia with an interocular difference of 1.00 D or greater (Zhang 2021). Eight studies restricted recruitment to those demonstrating a minimum myopic progression rate of at least 0.50 D in the year prior to enrolment (ATOM 2 Study 2012; Anstice 2011; Cheng 2010; CONTROL Study 2016; Lu 2015; Swarbrick 2015; LAMP Study 2019; Zhu 2021). Participants were sufficiently similar to satisfy the transitivity assumption for the NMA, that is, that there were no systematic differences between the available comparisons other than the treatments being compared.

Characteristics of the comparisons

Myopia control intervention versus control or placebo

Optical interventions

Spectacles

Undercorrection versus fully corrected single vision spectacle lenses (SVLs) (3 studies; Adler 2006; Chung 2002; Koomson 2016). These studies, conducted in Israel, China and Ghana, compared the effect of under correcting myopia by either 0.50 D or 0.75 D versus fully corrected SVL. The follow‐up periods were 18 months for Adler 2006 and 24 months for Chung 2002 and Koomson 2016.

Multifocal spectacle lenses (MFSLs) versus single vision spectacle lenses (SVLs) (13 studies; Cheng 2010; COMET Study 2003: COMET2 Study 2011; Edwards 2002; Fulk 1996; Fulk 2002; Hasebe 2008; Houston Study 1987; Jensen 1991; MIT Study 2001; Pärssinen 1989; STAMP Study 2012; Yang 2009). These studies were conducted in North America (7 studies), Asia (4 studies) and Europe (2 studies). All studies enroled children aged 8 to 15 years. MFSLs were either bifocal (6 studies) or progressive addition lenses (7 studies) with near additions between +1.00 D and +2.00 D. The study durations were between 18 and 36 months. Eight studies had two arms and five studies had three arms. Hasebe 2008 compared bifocals with two add powers (+1.00 D and +2.00 D) to SVLs. Jensen 1991 randomised children to one of three groups, bifocals, SVLs or timolol maleate eye drops, and Pärssinen 1989 compared a group wearing bifocals (+1.75 D add) to a group wearing SVLs for distance vision only and a reference group wearing SVLs continuously.

Peripheral plus spectacle lenses (PPSL) versus single vision spectacle lenses (SVLs) (6 studies; Bao 2021; Hasebe 2014; Han 2018; Lam 2020: Lu 2015: Sankaridurg 2010). Novel spectacle lens designs have been developed that aim to reduce peripheral hyperopic defocus. These lenses, designated PPSLs, were compared to SVLs in Chinese and Japanese myopic children aged 6 to 16 years. Study durations were 1 to 2 years. Sankaridurg 2010 tested three lens designs (designated types I, II and III) that provided different relative peripheral power against SVLs in children aged 6 to 16 years. Hasebe 2014 compared two positively aspherised progressive addition lens designs, with +1.00 D or +2.00 D near add powers and a relative plus power in the upper portion of the lens, to SVLs. Lu 2015 randomised children to receive either PPSLs with up to a +2.50 D near addition or SVLs. Han 2018 conducted a three‐arm study in which children were randomised to PPSLs, SVLs, or orthokeratology lenses. Lam 2020 adapted a design that had previously been used in contact lenses (DISC Study 2011), to develop a spectacle lens with a clear central zone for distance correction and an annular peripheral zone consisting of a multiple array of segments approximately 1 mm in diameter, providing +3.50 D of myopic defocus. The lens, which is termed the ‘Defocus Incorporated Multiple Segments' (DIMS) lens, was tested in a two‐year study involving Chinese children aged 9 to 13 years, who were randomised to wear either DIMS lenses or SVLs. Finally, Bao 2021 tested a lens design based on the same principal that consisted of concentric rings of aspheric lenslets to provide myopic defocus. Children aged 8 to 13 years were randomised in a three‐arm study to receive either a lens with highly aspherical lenslets, a lens with slightly aspherical lenslets, or SVLs. The study reported interim results on myopia progression at one year.

Contact lenses

Multifocal soft contact lenses (MFSCL) versus single vision soft contact lenses (SVSCLs) (9 studies; Anstice 2011; BLINK Study 2020; Chamberlain 2019; CONTROL Study 2016; DISC Study 2011; Fujikado 2014; Garcia‐del Valle 2021: Ruiz‐Pomeda 2018; Sankaridurg 2019). Nine studies investigated the efficacy of a variety of MFSCL designs compared to SVSCL. The MFSCLs incorporated a central zone to provide clear distance vision with relatively more positive peripheral lens power, which either increased gradually towards the periphery (progressive design) or presented as discrete peripheral annular zones (concentric ring design). Three studies followed participants for 12 months, four provided data to 20 to 24 months, and two had a duration of 36 months (BLINK Study 2020; Chamberlain 2019). Seven studies used a parallel‐group design, comparing MFSCLs with SVSCLs, and two studies used a cross‐over design (Anstice 2011; Fujikado 2014). Six studies adopted similar eligibility criteria and randomised children, aged 6 to 18 years with low to moderate myopia up to −6.00 D; Garcia‐del Valle 2021 included myopes to −8.75 D. Anstice 2011 and CONTROL Study 2016) only included children with documented myopia progression of −0.50 D or greater in the previous year, and the CONTROL Study 2016 additionally restricted inclusion to myopic children with near esophoria. Three studies used a similar centre distance dual focus concentric ring design with alternating distance correction zones and peripheral zones providing +2.00 D of defocus (Anstice 2011; Chamberlain 2019; Ruiz‐Pomeda 2018). These studies were conducted in New Zealand (Anstice 2011), Spain (Ruiz‐Pomeda 2018) and at sites in Europe, Asia and Canada (Chamberlain 2019). Garcia‐del Valle 2021 tested a MFSCL with a progressive design (+2.00 D addition) compared to SVSCL in Spanish schoolchildren age 7 to 15 years. Two studies, conducted in the USA (CONTROL Study 2016; BLINK Study 2020), used commercially available MFSCLs. The CONTROL Study 2016 evaluated children aged 8 to 18 years with progressive myopia, randomised to wear either a concentric bifocal soft contact lens or SVSCLs. The near add was selected based on the add power to neutralise the associated esophoria. The ‘Bifocal Lenses in Near‐sighted Kids' (BLINK) study (BLINK Study 2020), tested the efficacy of bifocal soft contact lenses with a central correcting zone for myopia and either a medium add (+1.50 D) or high add (+2.50 D) compared to SVSCLs. Three studies, conducted in China and Japan, used novel custom MFSCL designs (DISC Study 2011; Fujikado 2014; Sankaridurg 2019). The DISC Study 2011 tested the ‘Defocus Incorporated Soft Contact (DISC) lens’, a custom‐made bifocal soft contact lens of concentric ring design with a +2.50 D addition alternating with the normal distance correction. The DISC lens was compared to SVSCL in Chinese school children aged 8 to13 years, who were followed for two years. Fujikado 2014 used a cross‐over study design, in which Japanese children aged 6 to 16 years were randomised to wear a progressive MFSCL with a peripheral power of +0.50 D or SVSCLs in both eyes for 1 year and then were switched to the other type of lens for the second year. Sankaridurg 2019 randomised Chinese children aged 8 to 13 years to one of five groups: two groups wore MFSCLs that imposed peripheral myopic defocus of +1.50 D or +2.50 D with a stepped, relative positive power centrally of up to +1.00 D; and two groups wore extended depth of focus soft lens designs to optimise focus in front of and on the retina and degrade focus behind the retina. The control lens was a SVSCL.

Spherical aberration soft contact lenses versus single vision soft contact lenses (SVSCLs) (1 study; Cheng 2016). This study randomised children aged 8 to 11 years to receive soft contact lenses with or without positive spherical aberration. Although the study was conducted in the USA, it enroled mostly Asian children (91%). The study was planned for two years, but was stopped early and reported only one‐year data.

Rigid gas‐permeable (RGP) contact lenses versus single vision soft contact lenses (SVSCLs) or single vision spectacle lenses (SVLs) (2 studies; CLAMP Study 2004; Katz 2003). Two studies investigated the impact of RGP lenses on myopia progression compared to SVLs. Katz 2003 randomised Singaporean children aged 6 to 12 years to SVLs or RGP lenses. Myopia progression was evaluated at 1 and 2 years. The Contact Lens and Myopia Progression (CLAMP) Study (CLAMP Study 2004), was conducted in the USA and randomised children to RGP or soft single vision contact lenses. Annual myopia progression was reported based on change in SER and axial length, for the three‐year duration of the study.

Orthokeratology lenses versus single vision spectacle lenses (SVLs) or contact lenses (9 studies; Bian 2020; Charm 2013; Han 2018; Jakobsen 2022; Lyu 2020; Ren 2017; ROMIO Study 2012; Tang 2021; Zhang 2021). Eight parallel‐group studies compared overnight orthokeratology contact lenses or SVLs, and in one study SVSCLs (Tang 2021). Participants were followed for 1 to 2 years. Seven studies enroled children with low to moderate degrees of myopia (up to −6.00 D), and two studies selectively recruited children with myopia 5.00 D or greater (Charm 2013; Lyu 2020). Zhang 2021 included participants with anisomyopia with a difference in myopia between eyes of 1.00 D or greater. Eight of the nine studies were conducted in China and one in Denmark (Jakobsen 2022). Axial length was the primary outcome in all studies. The 'Retardation of Myopia in Orthokeratology' (ROMIO) Study (ROMIO Study 2012), randomised 102 Chinese children aged 6 to 12 years to overnight orthokeratology lenses or SVLs, who were followed for two years. Charm 2013 randomised 52 highly myopic children (aged 8 to 11 years), with a SER of at least −5.75 D to partial reduction overnight orthokeratology lenses and daily SVLs for residual myopia, or a control group who were fully corrected with SVLs. Axial length was measured at six‐monthly intervals for two years. Lyu 2020 similarly investigated partial reduction orthokeratology lenses in participants with myopia up to −8.75 D. They randomised 102 children aged 8 to12 years into three groups: (1) orthokeratology lenses with a target reduction of 6.00 D; (2) orthokeratology lenses with a 4.00 D target reduction; or (3) SVLs. Axial length was measured at baseline and at 12 months. Jakobsen 2022 randomised 60 Danish children aged 6 to 12 years to orthokeratology lenses or SVLs, and followed them for 18 months. Four studies compared orthokeratology lenses to SVLs in Chinese children aged 8 to 15 years with myopia (Bian 2020; Han 2018; Ren 2017; Tang 2021). Ren 2017 also included a group that was treated with 0.01% atropine, and Han 2018 included a group wearing PPSLs.

Pharmacological

Anti‐muscarinic agents

-