Video

Xxx.

Abbreviations: LAMS, lumen-apposing metallic stent; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Introduction

Accessing the bypassed portion of the stomach and small bowel for endoscopic interventions in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is challenging. In the case of bowel obstruction distal to the Roux-en-Y limb, decompression of the gastric pouch and bypassed stomach can be achieved with percutaneous enterostomy/gastrostomy tube placement by interventional radiology, deep enteroscopy, or surgery.1,2 The venting tube is usually placed within the alimentary limb of the jejunum in these approaches. However, in certain patients with obstruction distal to the jejunojejunal anastomosis or within the biliopancreatic limb, decompression of the excluded stomach is required.

Accessing excluded parts of the GI tract via lumen-apposing metallic stents (LAMSs) has created new possibilities for biliary and luminal interventions in patients with altered anatomy.1,3 Studies have shown LAMSs can be used to form gastrogastrostomy to the bypassed stomach to help relieve bowel obstructions in patients with RYGB.1,3 For patients with obstruction within the distal parts of the small bowel beyond the level of jejunojejunal anastomosis, creation of gastrogastrostomy alone may not be optimal. Currently, no study has demonstrated the feasibility of using LAMSs to access the bypassed stomach specifically for the purpose of performing a percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement.1,3 Here, we present a case of a palliative venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement using LAMSs in a woman with RYGB (Video 1, available online at www.giejournal.org).

Case Description

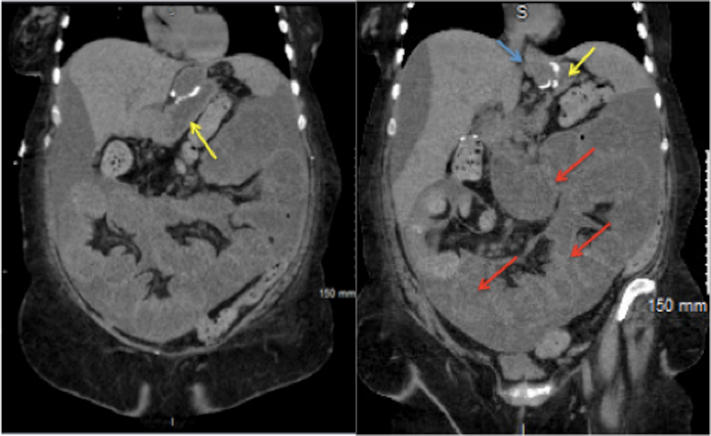

A 63-year-old woman with a history of a lap band converted to RYGB and metastatic small-bowel adenocarcinoma on palliative chemotherapy presented with recurrent small-bowel obstruction. Multiple CT scans were remarkable fordistended gastric pouch and bypassed stomach with multiple layers of obstruction distal to the jejunojejunal anastomosis (Fig. 1). Because of extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis and malignant ascites, she was a poor candidate for surgical or radiological enterostomy tube placement. Endoscopically, we considered less invasive approaches such as gastrogastrostomy stent alone; however, we were concerned about being unable to adequately drain the patient’s multiple levels of small-bowel obstruction. In addition, given her overall prognosis and short life expectancy, we wanted to avoid repeat procedures such as waiting for a gastrogastrostomy tract to mature prior to a follow-up procedure. For these reasons, the decision was made to proceed with placement of a palliative venting PEG tube through a LAMS-assisted approach.

Figure 1.

Dilated bypassed stomach (yellow arrow) with multiple dilated loops of small bowel. Dilated gastric pouch (blue arrow), dilated bypassed stomach (yellow arrow), and multiple dilated distal loops of small bowel (red arrows).

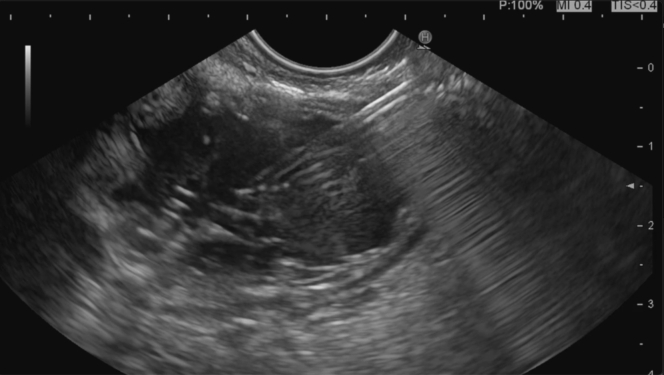

She received prophylactic cefazolin prior to the procedure and was placed under general anesthesia. Under EUS guidance, the distended bypassed stomach was identified (Fig. 2) and punctured with a 19-gauge FNA needle (Expect; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Mass, USA). A mixture of half-strength ionic contrast with normal saline was injected, resulting in further expansion of the bypassed stomach under fluoroscopic and endosonographic guidance (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Initial EUS view of the bypassed stomach (distended and fluid-filled).

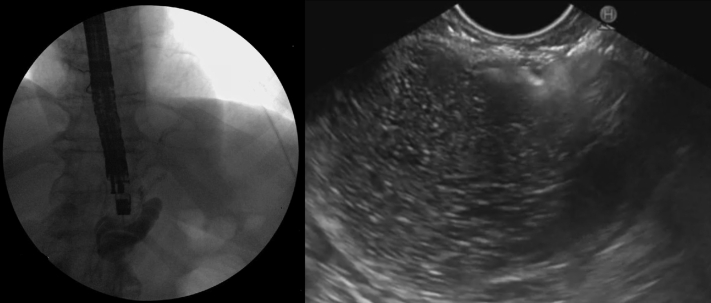

Figure 3.

Expansion of the excluded stomach with a mixture of saline and ionic contrast in preparation for lumen-apposing metallic stent placement under fluoroscopic (left) and echoendoscopic (right) guidance.

Following this, an electrocautery-enhanced LAMS delivery catheter (AXIOS; Boston Scientific) was used to puncture and deploy a 20- × 10-mm LAMS into the excluded stomach (Fig. 4). The LAMS was then dilated with a through-the-scope balloon dilator (CRE; Boston Scientific) to a maximum diameter of 18 mm under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 5). The endoscope was passed through the stent, and the bypassed stomach was insufflated with carbon dioxide to appose the gastric and abdominal walls. A 20F gastrostomy tube (EndoVive; Boston Scientific) was then placed using the “pull guidewire” technique after identifying an ideal location within the distal gastric body. A 25-mm snare was used to minimize the bumper surface size for ease of passage through the coaxial stent and prevent LAMS dislodgement during the maneuver (Fig. 6). The venting PEG was successfully placed within the excluded stomach (Fig. 7). There was no immediate adverse event. Using an endoscopic approach, we were able to drain the most proximal points in the patient’s anatomy. The patient was successfully discharged 1 day postprocedure after clinical resolution of her obstructive symptoms. Despite several months of recurrent admissions for obstructive symptoms, she was able to spend the last 3 weeks of her life with her family at home before she unfortunately passed away while in hospice care.

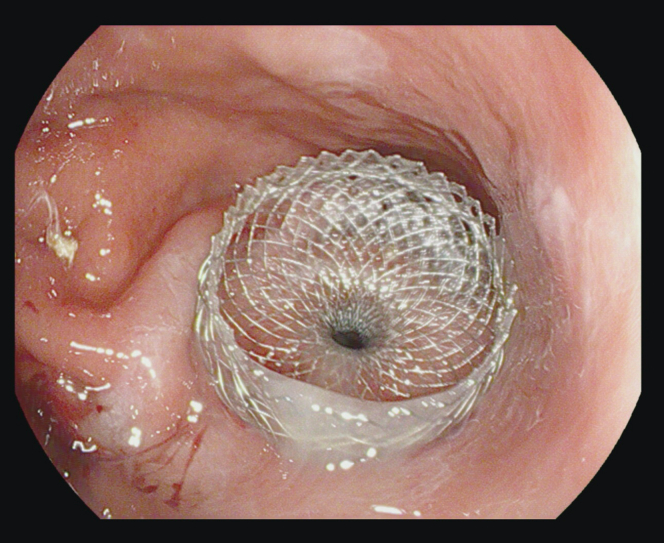

Figure 4.

Successful placement of a 20- × 10-mm lumen-apposing metallic stent connecting the bypassed stomach to the gastric pouch.

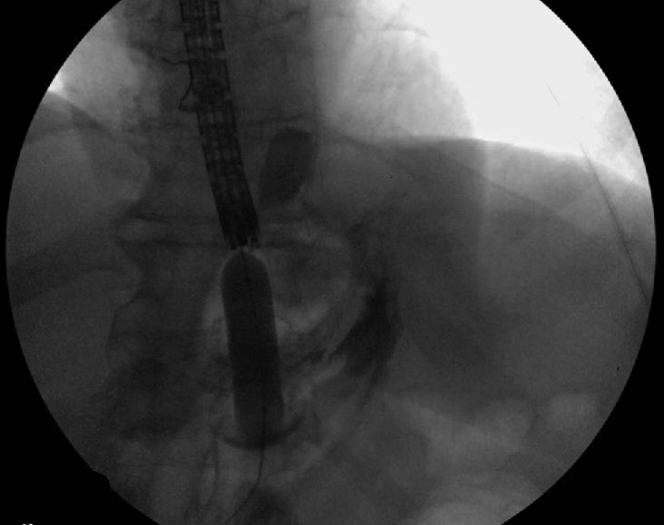

Figure 5.

Dilation of the AXIOS (Boston Scientific) stent with 18-mm through-the-scope CRE (Boston Scientific) balloon under fluoroscopic guidance over a guidewire.

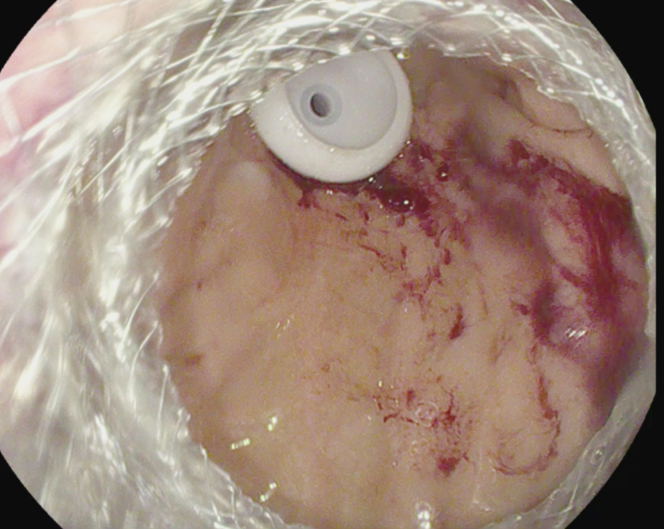

Figure 6.

Minimizing bumper surface size with a snare for ease of passage through the AXIOS (Boston Scientific) stent.

Figure 7.

Successful placement of percutaneous gastronomy through the lumen-apposing metallic stent.

Discussion

Decompression of the excluded stomach after RYGB can be a challenge. Shaikh et al4 described 95% technical success with CT scan–assisted gastrostomy tube placement for 41 cases of patients with RYGB. Four major adverse events including tube dislodgement were reported in their cohort. Attam et al1 described using endoscopic ultrasound to insufflate the remnant stomach, followed by fluoroscopically guided PG placement. The technical success was 90% with no major adverse events reported in any of the 10 cases. The feasibility of these techniques is limited in certain circumstances such as those with peritoneal carcinomatosis and poor surgical candidates. It is important to recognize patients with malignant ascites have a higher risk of leaks with PEG placements.5,6 These risks can be limited if preprocedural paracentesis is performed and should be discussed with patients prior to placement. Our case illustrates the utility of gastrogastrostomy-assisted venting PEG tube in patients with gastric bypass anatomy.

Disclosure

Dr Abidi is a consultant for Apollo Endosurgery, Ambu USA, and ConMed. Dr Patel is a consultant for Boston Scientific. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Supplementary data

EUS guided LAMS-assisted percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

References

- 1.Attam R., Leslie D., Freeman M., et al. EUS-assisted, fluoroscopically guided gastrostomy tube placement in patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a novel technique for access to the gastric remnant. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rueth N., Ikramuddin S., Andrade R. Endoscopic gastrostomy after bariatric surgery: a unique approach. Obes Surg. 2010;20:509–511. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein E.G., Cynamon J., Katzman M.J., et al. Percutaneous gastrostomy of the excluded gastric segment after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:914–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaikh S.H., Stenz J.J., McVinnie D.W., et al. Percutaneous gastric remnant gastrostomy following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a single tertiary center's 13-year experience. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018;43:1464–1471. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Issaka R.B., Shapiro D.M., Parikh N.D., et al. Palliative venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube is safe and effective in patients with malignant obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1668–1673. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pothuri B., Montemarano M., Gerardi M., et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in patients with malignant bowel obstruction due to ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Xxx.

EUS guided LAMS-assisted percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.