Significance

BAP1 modulates crucial cellular pathways that regulate genomic stability and cell death. BAP1 mutations on the one hand favor malignant transformation and mesothelioma development; on the other hand, they reduce mesothelioma aggressiveness. Investigating this apparent paradox, we discovered that BAP1 deubiquitylates and stabilizes HIF-1α in hypoxia; thus, BAP1 inactivating mutations significantly reduce HIF-1α. Given the critical role of HIF-1α in promoting tumor invasion, we propose that: 1) Reduced BAP1 in the tumor cells and tumor microenvironment of individuals carrying germline BAP1 mutations may contribute to the reduced invasion and the significantly improved prognosis of mesothelioma; 2) targeting wild-type BAP1 after tumor development could be a novel effective strategy to reduce HIF-1α protein levels in hypoxic tissues and impair tumor growth.

Keywords: BAP1, HIF-1α, hypoxia, mesothelioma, cancer syndrome

Abstract

BAP1 is a powerful tumor suppressor gene characterized by haplo insufficiency. Individuals carrying germline BAP1 mutations often develop mesothelioma, an aggressive malignancy of the serosal layers covering the lungs, pericardium, and abdominal cavity. Intriguingly, mesotheliomas developing in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations are less aggressive, and these patients have significantly improved survival. We investigated the apparent paradox of a tumor suppressor gene that, when mutated, causes less aggressive mesotheliomas. We discovered that mesothelioma biopsies with biallelic BAP1 mutations showed loss of nuclear HIF-1α staining. We demonstrated that during hypoxia, BAP1 binds, deubiquitylates, and stabilizes HIF-1α, the master regulator of the hypoxia response and tumor cell invasion. Moreover, primary cells from individuals carrying germline BAP1 mutations and primary cells in which BAP1 was silenced using siRNA had reduced HIF-1α protein levels in hypoxia. Computational modeling and co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that mutations of BAP1 residues I675, F678, I679, and L691 -encompassing the C-terminal domain-nuclear localization signal- to A, abolished the interaction with HIF-1α. We found that BAP1 binds to the N-terminal region of HIF-1α, where HIF-1α binds DNA and dimerizes with HIF-1β forming the heterodimeric transactivating complex HIF. Our data identify BAP1 as a key positive regulator of HIF-1α in hypoxia. We propose that the significant reduction of HIF-1α activity in mesothelioma cells carrying biallelic BAP1 mutations, accompanied by the significant reduction of HIF-1α activity in hypoxic tissues containing germline BAP1 mutations, contributes to the reduced aggressiveness and improved survival of mesotheliomas developing in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations.

BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1) is a deubiquitylase that modulates DNA repair by homologous recombination, chromatin assembly, transcription, intracellular calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis, different mechanisms of cell death, and mitochondrial metabolism (1–3). The cells of carriers of heterozygous germline BAP1 mutations (BAP1+/−) contain about 50% of the amount of BAP1 found in BAP1 wild-type (BAP1WT) individuals, levels that are insufficient for the normal biological activities of BAP1 (4, 5). BAP1+/− carriers are therefore affected by the BAP1 cancer syndrome, and close to 100% of them develop one or more cancers during their lifetime (1–3, 6). About 30% of BAP1+/− carriers developed diffuse malignant mesothelioma, a malignancy of the pleura, peritoneum, and/or, rarely, pericardium (1). Germline BAP1 mutations are transmitted in a Mendelian fashion; hence, multiple cases of mesothelioma are seen in affected families (1, 6–9). The critical causative role of BAP1 mutations in mesothelioma is underscored by the finding that acquired (somatic) mutations are found in ~ 60% of sporadic mesotheliomas (1, 10). Although mesothelioma can develop in patients affected by other tumor predisposition syndromes caused by inactivating heterozygous germline mutations of TP53, BRCA2, BLM, etc., mesotheliomas in these syndromes are rare (1, 11–14). Instead, 30% of carriers of germline BAP1 mutations have developed mesothelioma, underscoring the key role of BAP1 in preventing the malignant transformation of mesothelial cells (1, 6). In addition to mesothelioma, carriers of germline BAP1 mutations develop other malignancies, among them uveal and cutaneous melanomas, and clear cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC) are the most frequent. Indeed, several patients develop multiple malignancies during their life. For a detailed description of the BAP1 cancer syndrome as well as of the molecular pathways altered by BAP1 mutations, please see ref. 1. Sporadic mesotheliomas are polyclonal malignancies (15) not linked to germline mutations, mostly caused by exposure to asbestos, and have a dismal median survival of 6 to 24 mo from diagnosis (1, 16–18). Asbestos-induced signature mutations have not been demonstrated in mesothelioma. Mesothelioma is largely resistant to current therapies (16–18). Therapies based on promising experiments in rodents have not been successfully translated to patients (19–23). Therefore, there is an urgent need to identify novel effective therapies (16). Intriguingly, patients with sporadic mesothelioma whose cancer cells carry somatic biallelic BAP1 mutations may have improved survival of about 1 y compared to mesotheliomas with BAP1WT (24–26). Moreover, when carriers of germline BAP1 mutations develop mesothelioma, they have a significantly improved median survival of 6 to 7 y; some of them have survived mesothelioma and died of other causes 20+ y later (1, 6, 12, 13, 16, 27, 28). In summary, germline BAP1 mutations predispose carriers to developing mesothelioma; however, these same mutations, especially when present in both the tumor cells (biallelic mutations) and in the non-malignant cells that include the tumor microenvironment (heterozygous mutations), render mesotheliomas less aggressive and possibly more sensitive to chemotherapy (26). Why? The answer to this question is critical to design novel effective targeted therapies for all mesothelioma patients.

Mesothelioma causes patient demise largely by invading nearby tissues and organs and compromising vital functions; metastases occur late in the course of the disease and are rarely the cause of death (16, 29). Mesotheliomas developing in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations characteristically grow over the surface of the lungs and nearby organs: invasion is limited and occurs late in the course of the disease (6). Tumor invasion requires that malignant cells acquire the ability to grow in conditions of hypoxia, a process mainly regulated by the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). The activity of HIF-1 is dependent on a heterodimer formed by an oxygen-dependent α (HIF-1α) subunit, and an oxygen-independent constitutively expressed β subunit (HIF-1β). In normoxia, HIF-1α is targeted by prolyl hydroxylases; once hydroxylated, HIF-1α is recognized by the von-Hippel Lindau E3 ligase (VHL), ubiquitinylated, and targeted for proteasomal degradation. VHL modulates the rapid (~5 min) clearance of HIF-1α in normoxia, while an oxygen-independent slower degradation of HIF-1α further regulates HIF-1α, mainly in hypoxia (30). Hypoxia stabilizes HIF-1α resulting in its nuclear translocation where it forms an active heterodimer with HIF-1β (31). The HIF-1α/HIF-1β dimer (HIF-1) modulates transcription of over 1,000 genes, including anti-apoptotic and pro-angiogenic factors (31) that promote mesothelioma growth (32). As a result of HIF-1 transcriptional activity, cells undergo metabolic reprogramming from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis (Warburg effect) and produce biosynthetic intermediates required for the synthesis of NADPH, nucleotides, lipids, and ATP that support tumor cell growth (33, 34). In summary, HIF-1α activity facilitates the invasion of nearby tissues and metastases by allowing cancer cells to grow and survive in a hypoxic environment (34). The oxygen-dependent mechanisms that cause HIF-1α degradation and the genes that suppress HIF-1α in hypoxia have been studied in detail (10, 34), while the gene products that by facilitating HIF-1α expression and activity in hypoxia influence tumor invasion and metastases, remain largely unknown.

We reported that reduced BAP1 levels increase aerobic glycolysis (5). Because aerobic glycolysis is strongly linked to HIF-1α activation (33, 34), we investigated whether BAP1 inactivating mutations might induce HIF-1α activity, which in turn promotes glycolysis and tumor cell growth. We found the opposite to be true: BAP1+/− primary cells had reduced HIF-1α levels in hypoxia, and mesothelioma cells carrying biallelic BAP1 mutations almost constantly lost nuclear HIF-1α. We discovered that BAP1 binds, deubiquitylates, and stabilizes HIF-1α, an effect best seen in hypoxia. In summary, we discovered that BAP1 is a critical positive regulator of HIF-1α activity in hypoxia; therefore, when BAP1 is mutated the levels of HIF-1α are significantly reduced. Our results suggest that the improved prognosis observed in mesotheliomas carrying biallelic BAP1 mutations, and particularly in those developing in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations, may be linked to reduced HIF-1α levels in the tumor cells and in the microenvironment.

Results

Reduced BAP1 Activity Causes Decreased HIF-1α Protein Levels.

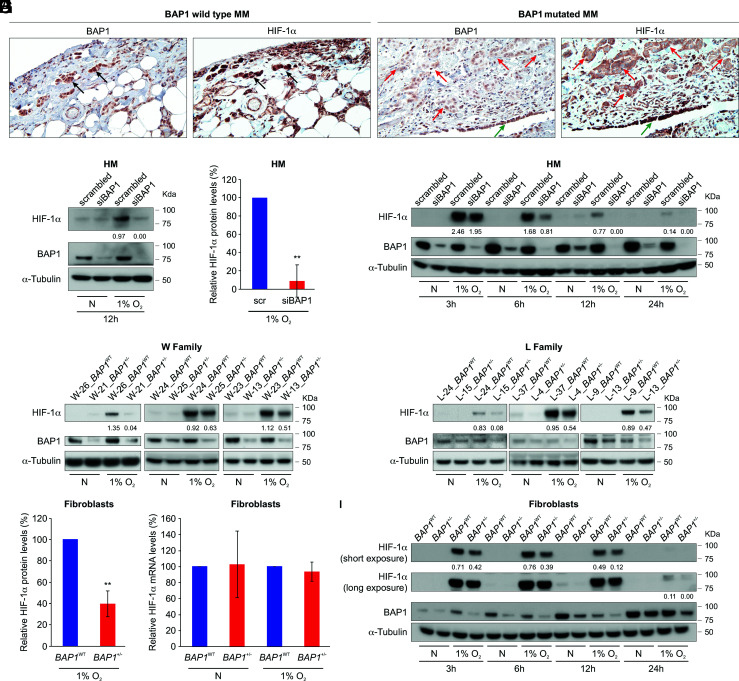

Immunostaining is considered the most sensitive and specific methodology to detect biallelic BAP1 mutations, and it is widely used in the differential diagnosis of mesothelioma (10). Nuclear staining is evidence of BAP1WT, while the absence of nuclear staining is evidence of mutated, inactive BAP1 (1, 6, 16, 24, 35). We analyzed BAP1 and HIF-1α using immunohistochemistry in 49 human mesothelioma biopsies obtained from the National Mesothelioma Virtual Bank (NMVB) (Fig. 1A). BAP1 nuclear staining was present in 14 BAP1WT biopsies and absent in 35 mutated biopsies. HIF-1α nuclear staining was present in 12 (86%) WT biopsies and absent in 26 (74%) mutated biopsies [χ2(1) = 14.7, P = 0.0001] (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). In the same biopsies negative for BAP1 and HIF-1α nuclear staining, the non-malignant nearby mesothelial cells, forming the single cell layer known as “pleura,” showed positive nuclear staining for both BAP1 and HIF-1α (internal positive control) (Fig. 1A). These findings suggested that loss of BAP1 might result in loss of HIF-1α nuclear functions. Additional staining of the only two available mesothelioma biopsies from patients carrying germline BAP1 mutations revealed the absence of nuclear staining for both BAP1 and HIF-1α and also reduced to undetectable expression of HIF-1α in the tumor microenvironment compared to tumors with BAP1WT (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Because IHC is not a precise test to quantify differences in protein expression, these findings will need to be validated by Western blot analyses of frozen biopsies of mesotheliomas developing in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations, which were not available to us.

Fig. 1.

Reduced BAP1 protein levels correlate with reduced HIF-1α protein levels. (A) Representative HIF-1α immunostaining in human pleural mesothelioma (MM) biopsies. Left: Note the nuclear staining for HIF-1α and BAP1 in BAP1 WT MM cells infiltrating the chest wall, black arrows. Right: Note the absence of HIF-1α and BAP1 nuclear staining in infiltrating BAP1-mutated MM cells, red arrows. Note that the normal nearby mesothelial cells (pleura) retain BAP1 and HIF-1α nuclear staining, green arrows. Magnification 400×; (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (B) Immunoblot, showing that BAP1 silencing in primary HM cells leads to reduced HIF-1α protein levels after 12 h incubation in 1% O2. Primary human mesothelial (HM) cells were transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siBAP1 (a pool of four different siRNAs targeting BAP1 mRNA: siBAP1#1, siBAP1#2, siBAP1#3 and siBAP1#5) and incubated in normoxia (N) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 12 h. (C) Densitometric analysis of HIF-1α protein levels normalized to α-tubulin in BAP1-silenced HM relative to scrambled (scr) control (100%); data shown as mean ± SD of n = 4 biological replicates, from four independent experiments. (D) Immunoblot: time course showing reduced HIF-1α protein levels in BAP1-silenced primary HM incubated in 1% O2 for the indicated time. (E and F): Immunoblot: reduced amounts of HIF-1α protein in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations. Total cell lysates of primary fibroblasts from 6 W (E) and 6 L (F) family members with or without BAP1 mutations, matched by gender and age. The W and L families are two families carrying BAP1+/− that we have been studying for ~20 y (8) (G) Densitometric analysis of HIF-1α protein levels normalized to α-tubulin from (E and F); densitometry of bands in BAP1+/− fibroblasts is expressed relative to BAP1WT fibroblasts (100%), matched by gender and age; data shown as mean ± SEM of n = 6 biological replicates per condition, representative of six independent experiments. (H) Quantitative PCR analysis of HIF1A mRNA expression levels normalized using the geometrical mean of 18S and ACTB reference genes, in BAP1WT and BAP1+/− fibroblasts. mRNA expression levels in BAP1+/− fibroblasts are expressed relative to BAP1WT. Data shown as mean ± SD of n = 6 biological replicates per condition, representative of six independent experiments. (I) Immunoblot: time course analysis showing reduced HIF-1α levels in BAP1+/− compared to BAP1WT fibroblasts incubated in 1% O2 for the indicated amount of time. In B, D, E, F, and I, decimals indicate the amounts of HIF-1α relative to α-tubulin as per densitometry. P value calculated using two-tailed unpaired Welch's t test, **P < 0.01.

Because mesothelioma cells carry many gene mutations and gene rearrangements (36) that could influence these results, we studied the possible link between BAP1 and HIF-1α in primary human mesothelial cells (HM). We incubated primary human mesothelial (HM) cells in 1% oxygen (O2) for 12 h, which is the hypoxic conditions to induce HIF-1α and found that HM cells transfected with siRNA targeting BAP1 mRNA (siBAP1) contained a significantly reduced amount of HIF-1α protein compared with control HM transfected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 1 B and C). Reduced HIF-1α protein levels in BAP1 silenced HM were reproducibly observed at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation in 1% O2 (Fig. 1D).

In addition, we observed a direct correlation between reduced BAP1 and HIF-1α protein levels in primary fibroblast cells we established from skin biopsies from six individuals carrying inherited heterozygous germline BAP1-inactivating mutations (BAP1+/−), compared to six age- and sex-matched wild-type BAP1 (BAP1WT) control family members, from two separate families: the Wisconsin (W) family and the Louisiana (L) family (4). When incubated in 1% O2 for 12 h, fibroblasts from BAP1+/− carriers from the W family (Fig. 1E) and the L family (Fig. 1F) contained significantly less HIF-1α protein compared with their age- and sex-matched BAP1WT controls from the same families, respectively (Fig. 1G). This mechanism was not regulated transcriptionally (Fig. 1H). Time course experiments in which total cell homogenates and RNAs were collected in parallel after 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation in 1% O2 confirmed that HIF-1α protein levels were always reduced in fibroblasts from BAP1+/− carriers incubated in 1% O2 compared to the BAP1WT controls (Fig. 1I), while no significant changes were detected in HIF1A mRNA levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). Reduced HIF-1α protein levels in BAP1+/− carriers were also observed in fibroblasts incubated in 0.1% O2 for 24 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S1D). To confirm that BAP1 regulates HIF-1α, we transduced BAP1+/− fibroblasts with human adenoviruses expressing GFP and BAP1WT for 24 h and cultured these cells in normoxia and in hypoxia for 6 h. Compared to the BAP1+/− fibroblasts transduced with the Ad-GFP control, which maintain about 50% of BAP1 activity, BAP1+/− fibroblasts transduced with Ad-BAP1 restored fully functional BAP1 and these cells displayed similar levels of HIF-1α as those observed in BAP1WT fibroblasts in hypoxia (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). Therefore, BAP1 modulates HIF-1α expression in hypoxia.

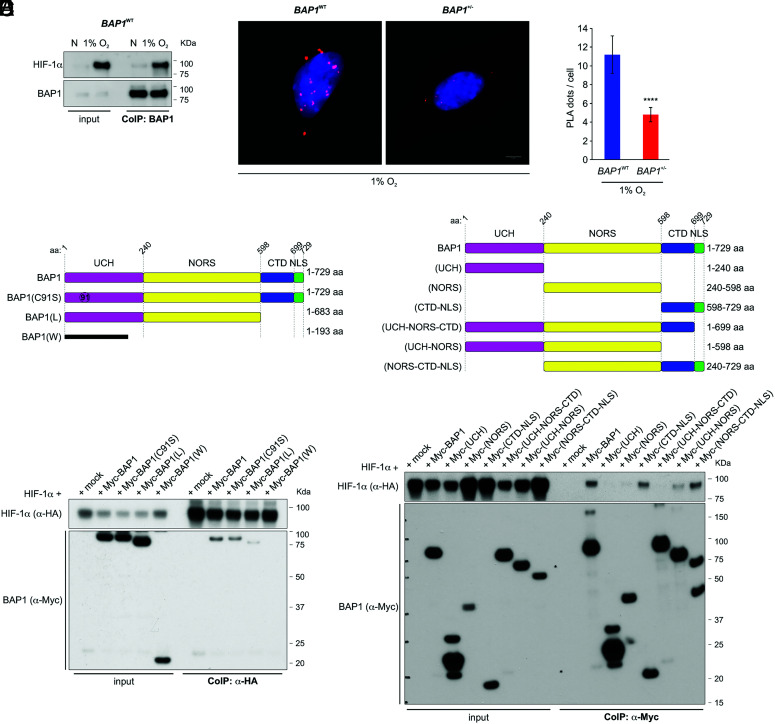

BAP1 Interacts with HIF-1α.

Co-immunoprecipitation (CoIP) and proximity ligation assay (PLA) experiments revealed that 1) HIF-1α and BAP1 bind to each other and co-precipitate (Fig. 2A), and 2) the nuclei of BAP1WT cells contained significantly more PLA positive signals—evidence of BAP1 and HIF-1α interaction—than BAP1+/− cells (Fig. 2 B and C).

Fig. 2.

BAP1 binds HIF-1α. (A) HIF-1α and BAP1 co-precipitate. CoIP of endogenous HIF-1α and BAP1, in BAP1WT fibroblasts grown in normoxia (N) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 4 h, using BAP1 as a bait. (B and C) PLA: red dots demonstrate the BAP1–HIF-1α interaction in the nuclei of BAP1WT and BAP1+/− fibroblasts incubated in 1% O2 for 6 h. Nuclei stained blue with DAPI (B); (Scale bar: 5 μm.) Bar graph: quantification of PLA red dots per cell showing reduced BAP1–HIF-1α interaction in BAP1+/− fibroblasts. Data shown as mean ± SD (n = 20 cells per condition) (C). (D and E) Mapping of the BAP1–HIF-1α interaction. The deletion of the CTD-NLS BAP1 domain –as observed in individuals of the W and L families, greatly reduces the interaction with HIF-1α. (D) CoIP of HIF-1α and BAP1 in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with HA-tagged HIF-1α and Myc-tagged [displayed on top (4)], BAP1, catalytic inactive (C91S), L family truncated mutant, W family truncated mutant, using anti-HA resin (E) The CTD-NLS domain of BAP1 is the major contributor to the interaction with HIF-1α, while the fragment consisting of the UCH together with the NORS domains binds to a minor extent. CoIP of HIF-1α and BAP1 in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with HA-tagged HIF-1α and Myc-tagged BAP1, and the Myc-tagged BAP1 fragments displayed on top (4) using anti-Myc resin.

We further investigated the specificity of the BAP1 interaction with HIF-1α in HEK-293 cells expressing Myc-BAP1 and HA-HIF-1α, using HA-Tag as bait. We found that the Myc-tagged truncated mutant proteins BAP1(W) and BAP1(L) (8) lose the ability to bind HIF-1α completely (W) or almost completely (L), while the full-length BAP1 and the catalytically inactive BAP1 mutant (C91S) (37) interact with HIF-1α (Fig. 2D). Deletion fragments of BAP1 (4) revealed that its C-terminal portion, consisting of the C-terminal domain (CTD) and nuclear localization signal (NLS), is key to the interaction with HIF-1α (Fig. 2E). The fragment consisting of the ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCH) with the non-regular secondary structure (NORS) domains binds to a minor extent (Fig. 2E), explaining why the BAP1(L) and BAP1(W) truncated mutants have lost or have reduced ability to bind HIF-1α, respectively.

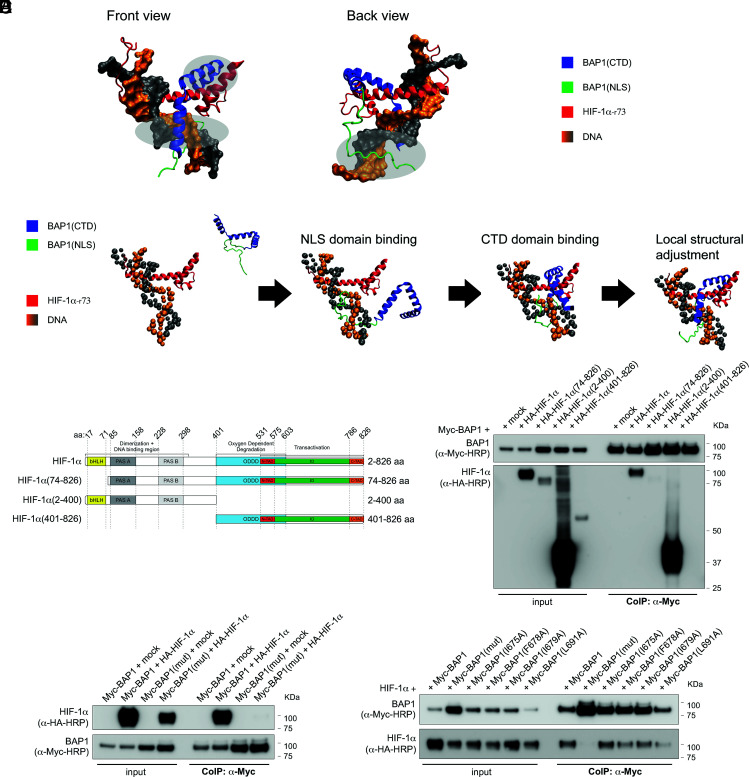

We established a computational model of the binding complex of BAP1 and HIF-1α. The structural predictions of the BAP1(CTD-NLS) are highly converged with three different methods: coarse-grained molecular dynamic simulations (38), the I-TASSER web server (39–41) and the RaptorX web server (42) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). For all models, residues 637 to 698 in the CTD form three consecutive helical fragments; in contrast, the full NLS domain is highly disordered (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). To study the binding between BAP1 and HIF-1α, first, a rigid docking protocol was applied to model the binding complex of the CTD of BAP1 (the NLS domain is removed due to its flexibility) and HIF-1α by using the ClusPro server (43–45) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). We identified residues 1 to 73 of HIF-1α as the main binding interface for BAP1. Consistently, RaptorX, a server utilizing co-evolutional information of proteins and deep learning techniques (46), also predicts that residue 1 to 73 of HIF-1α can form contacts with BAP1 with high probability (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Therefore, we focused on this region (noted as HIF-1α-r73). We used coarse-grained molecular dynamic simulations to model the binding complex of BAP1 (CTD-NLS) and HIF-1α-r73 (Fig. 3A), as well as understanding the binding kinetics (Fig. 3B). The NLS domain of BAP1 binds to HIF-1α-r73 and the thermodynamic stability of the binding complex increases through electrostatic interactions with DNA. Because the NLS domain is highly disordered, it appears as an extended structure and thus greatly increases the searching range of BAP1 during the binding process. For all simulated trajectories that successfully lead to the correct binding complex, the NLS domain of BAP1 binds to HIF-1α-r73-DNA ahead of the CTD. This suggests that the binding between BAP1 and HIF-1α is facilitated by the “fly-casting” mechanism (47, 48). Once the NLS domain of BAP1 binds to the DNA, it serves as an anchor to increase the local concentration of the CTD of BAP1 near HIF-1α, which helps the CTD bind sequentially (Fig. 3B). Notably, BAP1 binding to HIF-1α-r73-DNA does not require HIF-1β for the interaction. The critical role of the NLS domain of BAP1 is supported by the experimental fact that removing this domain greatly decreases the binding to HIF-1α (Fig. 2 D and E).

Fig. 3.

The CDT-NLS domain of BAP1 interacts with residues 1 to 73 of HIF-1α. (A) Structural modeling for the binding complex of BAP1(CTD-NLS) and HIF-1α (1-73) (residues 1 to 73 of HIF-1α) in the presence of DNA. The CTD of BAP1 is colored in blue, the NLS domain of BAP1 is colored in green, HIF-1α is colored in red, DNA is colored in orange and grey; three interacting regions are marked by light silver circles. (B) Coarse-grained molecular dynamic simulations to model the binding complex of BAP1(CTD-NLS) and HIF-1(1-73). The NLS domain (colored in green) is extended to increase the searching range of BAP1 to bind to HIF-1α. The NLS domain of BAP1 binds to HIF-1α first. Then the CTD binds sequentially. (C) HA-tagged HIF-1α fragments and HIF-1α domains: basic-helix-loop-helix motif (bHLH) protein, two Per and Sim (PAS) domain (A and B), oxygen-dependent degradation domain (ODDD), two transactivation domains (TAD): NH2-terminal (N-TAD) and COOH-terminal (C-TAD), intervening inhibitory domain (ID). (D) BAP1 binds to the N terminus region of HIF-1α [HIF-1α(2-400)]. Residues 1 to 73 of HIF-1α are essential for the interaction because HIF-1α(74-826) did not bind BAP1. CoIP of BAP1 and HIF-1α in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with Myc-BAP1 and HA-tagged HIF-1α or the HA-tagged HIF-1α fragments displayed in (C), or the empty vector (mock); anti-Myc resin was used as bait. (E) Point Mutations of residues I675, F678, I679, and L691 of BAP1 abolish the interaction with HIF-1α. CoIP of BAP1 and HIF-1α in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with Myc-BAP1 or Myc-BAP1(mut) (in which residues I675, F678, I679, L691 of BAP1 are mutated to Alanine), and HA-tagged HIF-1α or empty vector (mock); anti-Myc resin was used as bait. (F) The simultaneous mutation of residues I675, F678, I679, L691 of BAP1 abolish the interaction with HIF-1α, while single-point mutations decrease but do not abolish this interaction. CoIP of BAP1 and HIF-1α in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with HA-tagged HIF-1α and Myc-BAP1, or Myc-BAP1(mut) (in which residues I675, F678, I679, L691 of BAP1 are mutated to Alanine), or Myc-BAP1 mutants carrying each individual point mutation; anti-Myc resin was used as bait.

CoIP experiments in cells co-transfected with full-length Myc-tagged BAP1 (Myc-BAP1) and HA-tagged full-length HIF-1α, or HIF-1α fragments covering residues 74 to 826 [HIF-1α(74-826)], 2-400 [HIF-1α(2-400)], 401-826 [HIF-1α(401-826)] (Fig. 3C), confirmed that BAP1 binds to the N terminus region of HIF-1α [HIF-1α(2-400)] (Fig. 3D). As predicted by our computational model, residues 1 to 73 of HIF-1α are essential for the interaction because HIF-1α(74-826) did not bind BAP1 (Fig. 3D). The binding interfaces between BAP1(CTD-NLS) and HIF-1α-r73 in the presence of DNA include three parts: 1) residues K656, R657, K658 and K659 of BAP1(CTD-NLS) insert into the major groove of DNA through electrostatic interactions; 2) residues I675, F678, I679 and L691 of BAP1(CTD-NLS) form the hydrophobic core with residues F37, L40, Q43, L44 of HIF-1α-r73; 3) the NLS domain of BAP1 inserts into the major groove of DNA through electrostatic interactions. Among those residues, we found that the ones in BAP1 are more critical. Mutating those residues to A [BAP1(mut)] significantly decreases the binding stability; in contrast, mutating F37, L40, Q43, L44 of HIF1α-r73 to A [HIF1α(mut)] only has a minor effect (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D).

The accuracy of this model is supported by CoIP experiments revealing that mutations of residues I675, F678, I679, and L691 of BAP1 (CTD-NLS) to A abolish the interaction with HIF-1α (Fig. 3E), while point mutations of residues F37, L40, Q43, L44 of HIF-1α-(r73) to A did not affect the binding with BAP1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2E). All four residues forming the hydrophobic core of BAP1 must be mutated to completely abolish the binding of HIF-1α, while in the presence of single point mutations BAP1 interaction with HIF-1α is decreased but not entirely abolished (Fig. 3F). We verified that mutating four residues will not significantly change the structure of BAP1 (CTD-NLS) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). We concluded that the hydrophobic core formed by I675, F678, I679, L691 of BAP1 and F37, L40, Q43, L44 of HIF1α is sufficient to maintain the binding between the two proteins.

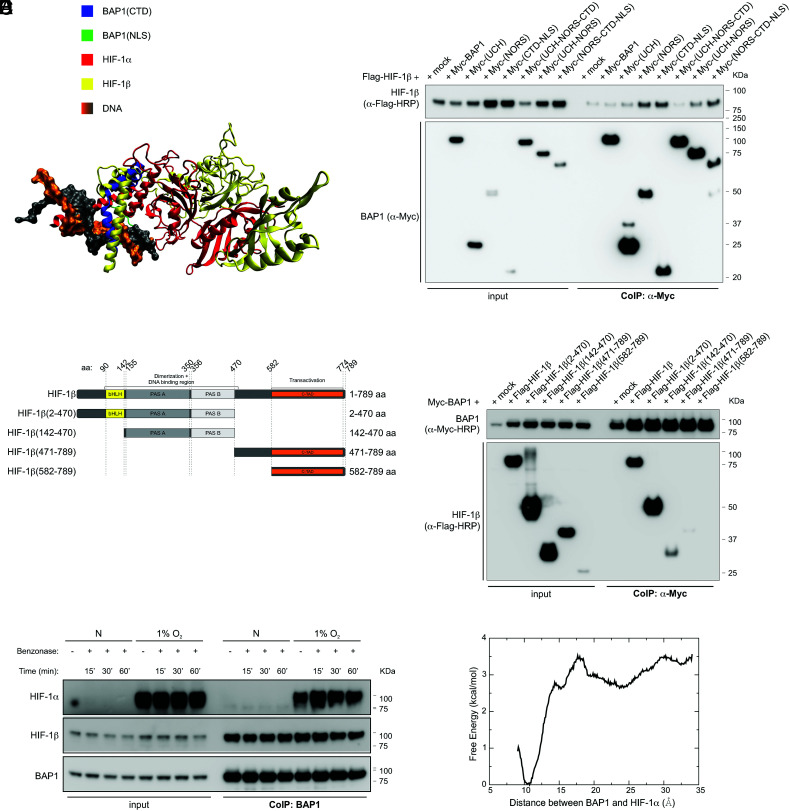

BAP1 Interacts with HIF-1α and HIF-1β Independently of DNA.

Aligning the crystal structure of HIF-1α-HIF-1β complex (PDB ID: 4zpr) (49) to our structural model for the binding complex of BAP1-HIF-1α reveals the significance of residue 1 to 73 of HIF-1α, as this region binds to both BAP1 and HIF-1β (Fig. 4A). Therefore, we checked whether BAP1 could also bind to HIF-1β. The deletion fragments of BAP1 (4) revealed that its NORS and CDT-NLS domains are the major contributors to the interaction with HIF-1β (Fig. 4B). CoIP experiments in cells co-transfected with full length Myc-tagged BAP1 (Myc-BAP1) and Flag-tagged full-length HIF-1β, or HIF-1β fragments covering residues 2 to 470 [HIF-1β(2-470)], 142-470 [HIF-1β(142-470)], 471-789 [HIF-1β(471-789)], 582-789 [HIF-1β(592-789)] (Fig. 4C), showed that BAP1 binds to the N terminus region of HIF-1β, specifically to the DNA binding and dimerization region [HIF-1β(2-470) and HIF-1β (142-470)] (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

BAP1 binding to HIF-1α and HIF-1β does not require DNA. (A) Shared binding region among BAP1, HIF-1α, and HIF-1β. The CTD of BAP1 is colored in blue, the NLS domain of BAP1 is colored in green, HIF-1α is colored in red, DNA is colored in orange and grey, and HIF-1β (colored in yellow) is docked onto the binding complex of BAP1 and HIF-1α by utilizing the crystal structure of HIF-1α–HIF-1β (PDB ID: 4zpr) (49). Missing residues of the crystal structure are added by the SWISS-MODEL server (50). (B) HIF-1β interacts with the NORS and CTD-NLS domain of BAP1. CoIP of HIF-1β and BAP1 in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with Flag-tagged HIF-1β and Myc-tagged BAP1 and the Myc-tagged BAP1 fragments displayed in Fig. 2E (4), using anti-Myc resin. (C) Flag-tagged HIF-1β fragments and HIF-1β domains: basic-helix-loop-helix motif (bHLH) protein, two Per and Sim (PAS) domain (A and B), and COOH-terminal transactivation domain (C-TAD). (D) CoIP of BAP1 and HIF-1β in homogenates from HEK-293 co-transfected with Myc-BAP1 and Flag-HIF-1β or the Flag-HIF-1β fragments displayed in (C), or the empty vector (mock); anti-Myc resin was used as bait. (E) HEK-293 cells were grown in normoxia (N) or hypoxia (1% O2) for 4 h. Cell homogenates were collected, treated with benzonase for 15, 30 or 60 min (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), and then used to co-immunoprecipitate endogenous HIF-1α and HIF-1β using BAP1 as bait. (F) Computational binding free energy profile between BAP1 and HIF-1α in the absence of DNA; the result indicates that the binding complex formed by BAP1 and HIF-1α can still hold when DNA is absent (the binding free energy ~ 3 kcal/mol).

We tested the hypothesis that although DNA facilitates the binding between BAP1 and HIF-1α, this binding complex still holds in the absence of DNA. Total cell homogenates of cells grown in normoxic or 1% O2 (hypoxic) conditions were incubated with benzonase for 15, 30, or 60 min, to achieve complete DNA degradation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Subsequently, endogenous BAP1 was used as bait to co-immunoprecipitate endogenous HIF-1α and HIF-1β (Fig. 4E). These results show that BAP1 can interact with HIF-1α and HIF-1β even without DNA. The computational analysis of the binding free energy profile between BAP1 and HIF-1α in the absence of DNA confirmed that the complex of BAP1-HIF-1α holds even without DNA, with a binding free energy of ~ 3 kcal/mol (Fig. 4F).

Identification of HIF-1α as a Substrate of BAP1.

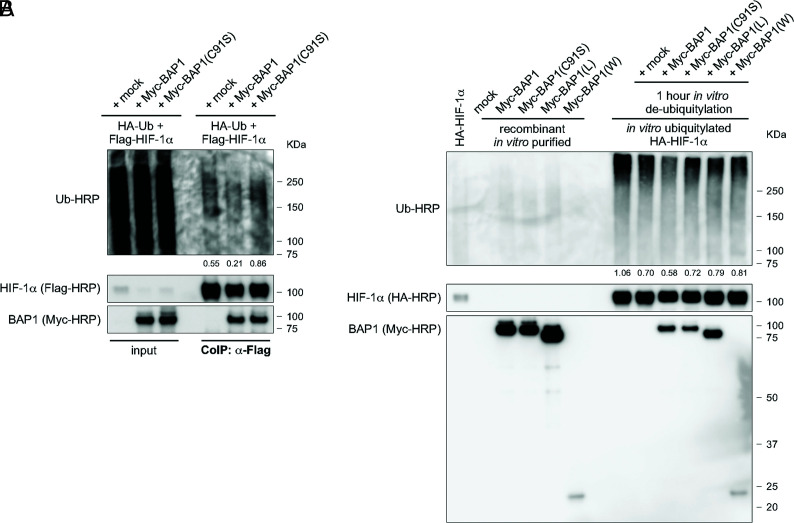

It has been reported that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway regulates the degradation of HIF-1α (51, 52). Since BAP1 is a member of the UCH subfamily of deubiquitylating enzymes (1), we investigated whether BAP1 deubiquitylates and stabilizes HIF-1α. We measured the ubiquitylation levels of exogenously expressed HIF-1α in cells co-transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ub), Flag-HIF-1α and Myc-BAP1. CoIP of Flag-HIF-1α showed reduced ubiquitin levels when cells overexpressed BAP1, but not in cells overexpressing the catalytic inactive BAP1(C91S), compared to mock control (Fig. 5A). In vitro de-ubiquitylation assays using purified recombinant proteins confirmed increased deubiquitylation of HIF-1α in the presence of BAP1, while in the presence of BAP1(C91S), BAP1(L), and BAP1(W) HIF-1α deubiquitylation was comparable to mock control (Fig. 5B). Together, these results demonstrated that BAP1 deubiquitylates and thus stabilizes HIF-1α.

Fig. 5.

BAP1 Deubiquitylates HIF-1α. (A) Reduced endogenous ubiquitylation of HIF-1α in HEK-293 cells co-transfected with Flag-tagged HIF-1α and Myc-tagged BAP1, catalytic inactive (C91S), or mock. Cells were treated with 10 µM MG-132 for 3 h, then total cell homogenates were collected and HIF-1α immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag resin. Ubiquitylation levels of the immunocomplexes were detected using an anti-Ub-HRP antibody and normalized on the total amount of Flag-HIF-1α immunoprecipitated (decimals indicate the ratio as per densitometric analysis). (B) Western blot analysis of in vitro ubiquitylation/de-ubiquitylation assay. HA-HIF-1α ubiquitylated in vitro, and subsequently incubated with immunopurified Myc-BAP1, Myc-BAP1(C91S), Myc-BAP1(L), Myc-BAP1(W), or mock, for 1 h. Ubiquitylation levels were detected using an anti-Ub-HRP antibody and normalized on the total amount of HA-HIF-1α (decimals indicate the ratio as per densitometric analysis).

Discussion

We discovered that BAP1 binds and deubiquitylates HIF-1α, contributing to the high levels of HIF-1α in hypoxia (Figs. 1–5). Accordingly, primary cells we derived from carriers of germline heterozygous BAP1 mutations, as well as cells in which we downregulated BAP1 using siRNA, and mesothelioma biopsies containing tumor cells with biallelic BAP1 inactivation, displayed significantly reduced levels of HIF-1α and loss of nuclear HIF-1α compared to normal cells or tumor cells with BAP1WT (Fig. 1). Therefore, our data suggest that BAP1 is a key regulator of HIF-1α and its tumor-promoting activities. In previous studies performed in normoxic conditions, we demonstrated that BAP1 regulates intracellular Ca2+ flux by binding and deubiquitylating, and thus stabilizing the IP3R3 receptor (4). Therefore, BAP1 deubiquitylating activity appears to remain active in both conditions, normoxia and hypoxia.

We found that BAP1 also binds to the N terminus region of HIF-1β, specifically to the DNA binding and dimerization region (Fig. 4). The crystal structure of HIF-1α-HIF-1β complex (PDB ID: 4zpr) (49) shows that without BAP1, HIF-1α, and HIF-1β bind to DNA (49), thus BAP1 is not required for HIF-1α-HIF-1β complex formation. Aligning the crystal structure of HIF-1α-HIF-1β complex (PDB ID: 4zpr) (49) to our structural model for the binding complex of BAP1-HIF-1α showed that both BAP1 and HIF-1β bind to the same residues of HIF-1α (1-73) on the DNA; however, in Fig. 3B, we demonstrate that BAP1, HIF-1α and the DNA form a complex without HIF-1β. In addition, we show that after total degradation of DNA, BAP1 remains bound to both HIF-1α and HIF-1β (Fig. 4A). Therefore, our data indicate that BAP1 is not required for HIF-1α-HIF-1β complex formation to functionally bind to DNA, that HIF-1β is not required for BAP1-HIF-1α complex formation to functional binding to DNA, and that although DNA facilitates the binding of BAP1 and HIF-1α, it is not required to maintain the binding of both BAP1-HIF-1α and BAP1-HIF-1β.

In summary, our data suggest that BAP1 directly binds and stabilizes both HIF-1α and HIF-1β increasing their intra-nuclear availability for dimer formation, thus fine-tuning HIF activities required to support malignant cell growth. So far, the pathogenic variants reported in ClinVar for both HIF-1α and HIF-1β are not located among the crucial residues of HIF-1α-r73 where HIF-1α can bind to BAP1, HIF-1β and DNA, or of HIF-1β (2-470) where HIF-1β can bind to BAP1, HIF-1α, and DNA. This finding suggests that tumor cell clones that may acquire HIF-1α and/or HIF-1β mutations that impair their binding to BAP1 may be negatively selected compared to tumor cell clones expressing HIF-1α and HIF-1β that maintain the capacity to bind to BAP1.

HIF-1α is the master regulator of cell growth in hypoxia (33, 34). HIF1 activity is regulated by the interaction of HIF-1α with >100 other proteins (53). Among them, VHL plays a key role by recruiting an E3-ubiquitin ligase complex to mediate HIF-1α protein degradation in normoxia. Biallelic BAP1 mutations occur in several human cancers (1); their tumor cells, based on our data studying mesothelioma, should contain reduced HIF-1α levels. However, this might not remain true in malignancies in which the VHL gene (34)—or other genes that suppress HIF-1α (10)—are also mutated and thus display constitutively high levels of HIF-1α, which may overrun the fine-tuning BAP1 deubiquitylating activity.

In addition to VHL, which is active in normoxia, other proteins mediate the ubiquitylation of HIF-1α in hypoxia. The UCH-L1 (UCHL1) is a deubiquitylase that has been shown to positively modulate HIF-1α levels (54). Our data identified BAP1 as a deubiquitylase that binds and inhibits the degradation of HIF-1α, an effect best observed in hypoxia. BAP1 shares 23% sequence homology with UCHL1 (55). UCHL1 hydrolyzes the C-terminal peptide tails of small ubiquitin derivatives but cannot hydrolyze large ubiquitin chains because of short active site crossover loops. BAP1 instead has long crossover loops and thus can process polyubiquitin chains (55, 56). Thus, UCHL1 and BAP1 are both independently required for HIF-1α stabilization and activities. UCHL1 and BAP1 were both identified as deubiquitylases for γ-tubulin through screening a siRNA library of deubiquitylases; however, when both UCHL1 and BAP1 were depleted using siRNA, the degradation of γ-tubulin was comparable to the γ-tubulin levels after either BAP1 or UCHL1 silencing alone (57). Future studies shall address whether these two ubiquitin hydrolases interact in modulating HIF-1α levels in hypoxia and whether their effects are cell type specific.

It has been proposed that targeting UCHL1 might reduce HIF-1α stabilization and impair tumor growth (54). Our data point to BAP1 as a novel target to reduce HIF-1α tumor-promoting activity in malignancies with elevated HIF-1α levels and intact VHL. We identified the nucleotides responsible for the binding between BAP1 and HIF-1α and BAP1 and HIF-1β. Previous studies using the HIF-1α inhibitor YC-1 (58) or siRNAs targeting HIF-1α in mesothelioma cells in tissue culture (59), revealed increased apoptosis; however, the authors suggested that an additional blockade was required to inhibit growth signals completely. We are designing small molecules to test the hypothesis that their intra-pleural administration alone or together with HIF-1α inhibitors, will interfere with the binding among BAP1 and HIF-1α and cause HIF-1α degradation. It is hoped that reduced HIF-1α activity will impair mesothelioma growth and increase susceptibility to therapy, as observed in patients carrying germline BAP1 mutations and tumors with biallelic BAP1 inactivating mutations (6).

Mesotheliomas have large areas of hypoxia (60). The activity of HIF-1α-induced metabolic reprogramming provides malignant cells with maximal growth support in a hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Therefore, the reduced levels of HIF-1α in BAP1-mutated tumor cells may contribute to the reduced tumor aggressiveness of BAP1-mutant mesotheliomas, compared to mesotheliomas with BAP1WT (6, 12, 13, 27, 28). Mesotheliomas developing in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations invariably carry biallelic inactivating BAP1 mutations (BAP1−/−), easily detectable by the absence of nuclear BAP1 staining, while the cells forming the tumor microenvironment carry heterozygous germline BAP1 mutations (BAP1+/−) (1, 8, 14). About ~60% of sporadic mesotheliomas carry somatic (acquired) biallelic inactivating BAP1−/−; however, the cells forming the tumor microenvironment are BAP1WT (1, 8, 14). Our hypothesis is that in sporadic BAP1−/− mesotheliomas, BAP1 loss results in reduced HIF-1α in the malignant cells; however, the surrounding hypoxic tumor cell microenvironment comprised of BAP1WT cells will maintain stable HIF-1α levels that sustain tumor cell invasion. Conversely, the hypoxic tumor microenvironment of mesotheliomas developing in patients carrying germline BAP1 mutations express reduced HIF-1α. Accordingly, these patients have less invasive tumors. This hypothesis, based on our in vitro experiments (Fig. 1 E–I), was supported by IHC analyses in which we studied mesothelioma biopsies from patients carrying germline BAP1 mutations. In their mesothelioma biopsies, IHC showed undetectable HIF-1α expression in the tumor cells and reduced HIF-1α expression in the cells forming the tumor microenvironment (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), compared to sporadic BAP1−/− mesothelioma biopsies which maintained HIF-1α expression in the surround BAP1WT cells (Fig. 1A). Altogether, these data suggest that reduced HIF-1α levels may contribute to the reduced aggressiveness of mesothelioma in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations (6, 12, 13, 27, 28). Reduced HIF-1α levels may also render mesothelioma cells more susceptible to cell death in hypoxia and this could contribute to the reported increased response to chemotherapy of BAP1 mutated mesotheliomas (26), and in those that develop among carriers of germline BAP1 mutations, in particular (6).

BAP1 mutations are not associated with an improved prognosis in uveal melanoma (UVM) and ccRCC, the other two malignancies that, together with mesothelioma, most often carry BAP1 mutations (1). Moreover, the loss of BAP1 expression has been detected together with increased expression of HIF-1α in UVM (61) and ccRCC (62, 63). These results appear to contradict our findings. However, in about 90% of ccRCC, the initiating event is the inactivation of the VHL gene located on chromosome 3 (64). Physiologically, VHL binds to HIF-1α targeting it for ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation, therefore, once VHL is lost, HIF-1α ubiquitylation is markedly reduced, and its levels are significantly increased (33, 34) an effect that should render the reduced deubiquitylation of HIF-1α by BAP1 in BAP1 deficient cells physiologically less relevant. The study in UVM (61) measured HIF1A mRNA levels and their relationship to BAP1 transcription. Here we report that BAP1 modulates the stability of the HIF-1α protein and that it does not regulate HIF-1α gene transcription. Moreover, similarly to ccRCC, deletions of chromosome 3 are frequent in UVM (65) with subsequent loss of VHL. In mesothelioma, instead, nucleotide level deletions as well as minute deletions of 100 to 300 bp are frequent throughout the BAP1 gene located on chromosome 3p, and nearby SETD2, SMARCC1, PBRM1 genes, but deletions extending to the VHL gene are very rare (66). Therefore, the effects of reduced deubiquitylating activity of BAP1 mutations on the HIF-1α protein may be more relevant in mesothelioma compared to ccRCC and UVM in which the very frequent inactivation of VHL may result in elevated levels of HIF-1α independently from BAP1 deubiquitylating activity. Overall, our findings may help explain the opposite effects on survival in BAP1-mutated mesothelioma compared to BAP1-mutated ccRCC and UVM. Further studies in renal cell carcinomas and UVMs, compared to mesothelioma, are necessary to fully address the mechanisms and the possible relationship with HIF-1α expression in these malignancies.

In summary, we report that BAP1 deubiquitylates and thus stabilizes HIF-1α in hypoxia, and, therefore, BAP1 mutations significantly reduce HIF-1α protein levels. Given the well-established role of HIF-1α in promoting tumor growth in hypoxia, we propose that the reduced aggressiveness and improved prognosis of mesothelioma in carriers of germline BAP1 mutations may result, at least in part, from the combined reduced HIF-1 activity caused by biallelic BAP1 mutations in mesothelioma cells and the presence of heterozygous BAP1 mutations in the cells that form the tumor microenvironment.

Materials and Methods

Subjects.

BAP1+/− mutant carriers and unaffected controls were recruited from the L and W families and provided informed written consent allowing their specimens to be used for this project. The collection and use of patient information and samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Hawaii (IRB no. CHS14406).

Technical Procedures.

Cell cultures, immunohistochemistry, gene silencing, qPCR, western blot (WB), Co-IP, in vitro ubiquitylation and de-ubiquitylation assays, Duolink PLA, and computational modeling were performed according to standard techniques and are described in SI Appendix.

Statistics and Reproducibility.

P values were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Welch’s t test, unless otherwise specified. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and marked with asterisks (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001), as indicated in the figure legends. All data collected met the normal distributions assumption of the test. Data are represented as mean ± SD, unless otherwise specified.in the figure legends. The exact sample size (n) for experimental groups/conditions and whether samples represent technical or cell culture replicates are indicated in the figure legends. The results shown are representative of experiments independently conducted three times that produced similar results.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We are in debt to the patients who donated their specimens for research. We would like to acknowledge the UH Cancer Center Microscopy, Imaging, and Flow Cytometry Core and the Leica Thunder Live Cell 3D microscope SIG: NIH S10ODO028515-01 for supporting this work. We acknowledge the NMVB for providing the mesothelioma biopsies. M.C. and H.Y. have a patent issued for “Using Anti-HMGB1 Monoclonal Antibody or other HMGB1 Antibodies as a Novel Mesothelioma Therapeutic Strategy” and a patent issued for “HMGB1 As a Biomarker for Asbestos Exposure and Mesothelioma Early Detection.” M.C. and H.Y. report funding from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) 1R01ES030948-01 (M.C. and H.Y.), the National Cancer Institute (NCI) 1R01CA237235-01A1 (M.C. and H.Y.) and 1R01CA198138 (M.C.), the US Department of Defense (DoD) W81XWH-16-1-0440 (H.Y., M.C., and H.I.P.), and from the UH Foundation through donations from the Riviera United-4-a Cure (M.C. and H.Y.), the Melohn Family Endowment, the Honeywell International Inc., the Germaine Hope Brennan Foundation, and the Maurice and Joanna Sullivan Family Foundation (M.C.). H.I.P. and H.Y. report funding from the Early Detection Research Network NCI 5U01CA214195-04. H.I.P. reports funding from Genentech, Belluck, and Fox LLP. J.N.O., F.B., and Q.W. work was supported by NSF (Grants PHY-2019745 and PHY-2019745) and by the Welch Foundation (Grant C-1792). J.N.O. is a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research sponsored by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

Author contributions

J.N.O., H.Y., and M.C. designed research; A.B., Q.W., A.A.Z., F.B., M.S-T., J.S.S., S.P., A.S., V.S., A.F., F.N., J.-H.K., M.M., Y.T., L.P., A.N., R.X., C.F., C.G., G.S., G.G., and H.I.P. performed research; C.B., M.N., and I.P. analyzed data; G.S. and H.I.P. contributed surgical specimens; and A.B. and M.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interest

The authors have organizational affiliations to disclose. M.C. is a board-certified pathologist who provides consultation for pleural pathology, including medical-legal. The authors have patent filings to disclose. M.C. has a patent issued for “Methods for Diagnosing a Predisposition to Develop Cancer”.

Footnotes

Reviewers: P.P.P., Renown Institute for Cancer; and I.L.P., Northwestern University.

Contributor Information

José N. Onuchic, Email: jose.onuchic@rice.edu.

Haining Yang, Email: haining@hawaii.edu.

Michele Carbone, Email: mcarbone@cc.hawaii.edu.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Carbone M., et al. , Biological mechanisms and clinical significance of BAP1 mutations in human cancer. Cancer Discov. 10, 1103–1120 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conway E., et al. , BAP1 enhances polycomb repression by counteracting widespread H2AK119ub1 deposition and chromatin condensation. Mol. Cell 81, 3526–3541.e8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masclef L., et al. , Roles and mechanisms of BAP1 deubiquitinase in tumor suppression. Cell Death Differ. 28, 606–625 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bononi A., et al. , BAP1 regulates IP3R3-mediated Ca(2+) flux to mitochondria suppressing cell transformation. Nature 546, 549–553 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bononi A., et al. , Germline BAP1 mutations induce a Warburg effect. Cell Death Differ. 24, 1694–1704 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbone M., et al. , Medical and surgical care of patients with mesothelioma and their relatives carrying germline BAP1 mutations. J. Thorac. Oncol. 17, 873–889 (2022), 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbone M., et al. , Combined genetic and genealogic studies uncover a large BAP1 cancer syndrome kindred tracing back nine generations to a common ancestor from the 1700s. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005633 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Testa J. R., et al. , Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to malignant mesothelioma. Nature Genet. 43, 1022–1025 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walpole S., et al. , Comprehensive study of the clinical phenotype of germline BAP1 variant-carrying families Worldwide. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 110, 1328–1341 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernardi R., et al. , PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR. Nature 442, 779–785 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bononi A., et al. , Heterozygous germline BLM mutations increase susceptibility to asbestos and mesothelioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 33466–33473 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pastorino S., et al. , A subset of mesotheliomas with improved survival occurring in carriers of BAP1 and other germline mutations. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, JCO2018790352 (2018), 10.1200/JCO.2018.79.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panou V., et al. , Frequency of germline mutations in cancer susceptibility genes in malignant mesothelioma. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 2863–2871 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbone M., et al. , Tumour predisposition and cancer syndromes as models to study gene-environment interactions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 533–549 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comertpay S., et al. , Evaluation of clonal origin of malignant mesothelioma. J. Translat. Med. 12, 301 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carbone M., et al. , Mesothelioma: Scientific clues for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 69, 402–429 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsao A. S., et al. , Current and future management of malignant mesothelioma: A consensus report from the national cancer institute thoracic malignancy steering committee, international association for the study of lung cancer, and mesothelioma applied research foundation. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13, 1655–1667 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mutti L., et al. , Scientific advances and new frontiers in mesothelioma therapeutics. J. Thorac. Oncol. 13, 1269–1283 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H., et al. , Aspirin delays mesothelioma growth by inhibiting HMGB1-mediated tumor progression. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1786 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivera Z., et al. , CSPG4 as a target of antibody-based immunotherapy for malignant mesothelioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 5352–5363 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goparaju C. M., et al. , Onconase mediated NFKβ downregulation in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Oncogene 30, 2767–2777 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nasu M., et al. , Ranpirnase interferes with NF-κB pathway and MMP9 activity, inhibiting malignant mesothelioma cell invasiveness and xenograft growth. Genes Cancer 2, 576–584 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pass H. I., et al. , Inhibition of hamster mesothelioma tumorigenesis by an antisense expression plasmid to the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Cancer Res. 56, 4044–4048 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapel D. B., Schulte J. J., Husain A. N., Krausz T., Application of immunohistochemistry in diagnosis and management of malignant mesothelioma. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 9, S3–S27 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farzin M., et al. , Loss of expression of BAP1 predicts longer survival in mesothelioma. Pathology 47, 302–307 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louw A., et al. , BAP1 loss by immunohistochemistry predicts improved survival to first-line platinum and pemetrexed chemotherapy for patients with pleural mesothelioma: A validation study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 17, 921–930 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumann F., et al. , Mesothelioma patients with germline BAP1 mutations have 7-fold improved long-term survival. Carcinogenesis 36, 76–81 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassan R., et al. , Inherited predisposition to malignant mesothelioma and overall survival following platinum chemotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 9008–9013 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores R. M., et al. , Extrapleural pneumonectomy versus pleurectomy/decortication in the surgical management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: Results in 663 patients. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 135, 620–626 (2008), 626.e1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moroz E., et al. , Real-time imaging of HIF-1alpha stabilization and degradation. PLoS One 4, e5077 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferrara N., Davis-Smyth T., The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr. Rev. 18, 4–25 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cacciotti P., et al. , SV40 replication in human mesothelial cells induces HGF/Met receptor activation: A model for viral-related carcinogenesis of human malignant mesothelioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12032–12037 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakazawa M. S., Keith B., Simon M. C., Oxygen availability and metabolic adaptations. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 663–673 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semenza G. L., HIF-1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 3664–3671 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nasu M., et al. , High incidence of somatic BAP1 alterations in sporadic malignant mesothelioma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 10, 565–576 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bueno R., et al. , Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat. Genet. 48, 407–416 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen D. E., et al. , BAP1: A novel ubiquitin hydrolase which binds to the BRCA1 RING finger and enhances BRCA1-mediated cell growth suppression. Oncogene 16, 1097–1112 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davtyan A., et al. , AWSEM-MD: Protein structure prediction using coarse-grained physical potentials and bioinformatically based local structure biasing. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 8494–8503 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy A., Kucukural A., Zhang Y., I-TASSER: A unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc. 5, 725–738 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J., et al. , The I-TASSER Suite: Protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Methods 12, 7–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J., Zhang Y., I-TASSER server: New development for protein structure and function predictions. Nucleic Acids Re.s 43, W174–W181 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kallberg M., et al. , Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat. Protoc. 7, 1511–1522 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vajda S., et al. , New additions to the ClusPro server motivated by CAPRI. Proteins 85, 435–444 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozakov D., et al. , The ClusPro web server for protein-protein docking. Nat. Protoc. 12, 255–278 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kozakov D., et al. , How good is automated protein docking? Proteins 81, 2159–2166 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S., Sun S., Li Z., Zhang R., Xu J., Accurate de novo prediction of protein contact map by ultra-deep learning model. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005324 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shoemaker B. A., Portman J. J., Wolynes P. G., Speeding molecular recognition by using the folding funnel: The fly-casting mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8868–8873 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trizac E., Levy Y., Wolynes P. G., Capillarity theory for the fly-casting mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2746–2750 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu D., Potluri N., Lu J., Kim Y., Rastinejad F., Structural integration in hypoxia-inducible factors. Nature 524, 303–308 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waterhouse A., et al. , SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang L. E., Gu J., Schau M., Bunn H. F., Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha is mediated by an O2-dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7987–7992 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Semenza G. L., HIF-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 167–171 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Semenza G. L., A compendium of proteins that interact with HIF-1alpha. Exp. Cell Res. 356, 128–135 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goto Y., et al. , UCHL1 provides diagnostic and antimetastatic strategies due to its deubiquitinating effect on HIF-1alpha. Nat. Commun. 6, 6153 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hanpude P., Bhattacharya S., Kumar Singh A., Kanti Maiti T., Ubiquitin recognition of BAP1: Understanding its enzymatic function. Biosci. Rep. 37, BSR20171099 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scheuermann J. C., et al. , Histone H2A deubiquitinase activity of the polycomb repressive complex PR-DUB. Nature 465, 243–247 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zarrizi R., Menard J. A., Belting M., Massoumi R., Deubiquitination of gamma-tubulin by BAP1 prevents chromosome instability in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 74, 6499–6508 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeo E. J., et al. , YC-1: A potential anticancer drug targeting hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95, 516–525 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shukuya T., et al. , Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha Inhibition in Von Hippel Lindau-mutant malignant pleural mesothelioma cells. Anticancer Res. 40, 1867–1874 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Francis R. J., et al. , Characterization of hypoxia in malignant pleural mesothelioma with FMISO PET-CT. Lung Cancer 90, 55–60 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brouwer N. J., et al. , Ischemia is related to tumour genetics in uveal melanoma. Cancers (Basel) 11, 1004 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang S. S., et al. , Bap1 is essential for kidney function and cooperates with Vhl in renal tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 16538–16543 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gu Y. F., et al. , Modeling renal cell carcinoma in mice: Bap1 and Pbrm1 inactivation drive tumor grade. Cancer Discov. 7, 900–917 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitchell T. J., et al. , Timing the landmark events in the evolution of clear cell renal cell cancer: TRACERx renal. Cell 173, 611–623.e17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harbour J. W., et al. , Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas. Science. 330, 1410–1413 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshikawa Y., et al. , High-density array-CGH with targeted NGS unmask multiple noncontiguous minute deletions on chromosome 3p21 in mesothelioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 13432–13437 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.