Abstract

Objectives

To synthesise empirical findings on the role of family in end-of-life (EOL) communication and to identify the communicative practices that are essential for EOL decision-making in family-oriented cultures.

Setting

The EOL communication settings.

Participants

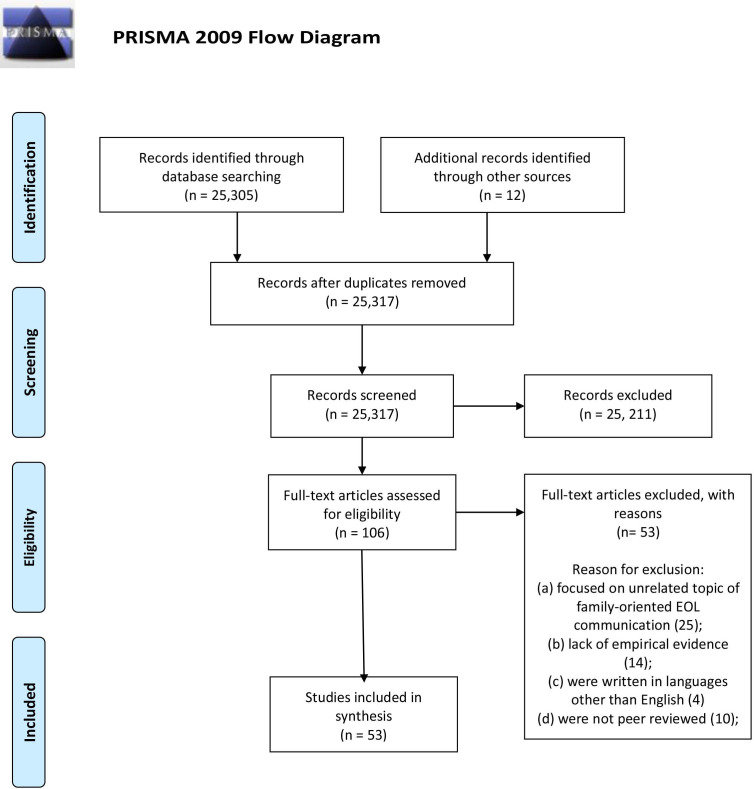

This integrative review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting guideline. Relevant studies published between 1 January 1991 and 31 December 2021 were retrieved from four databases, including the PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE and Ovid nursing databases, using keywords with meanings of ‘end-of-life’, ‘communication’ and ‘family’. Data were then extracted and coded into themes for analysis. The search strategy yielded 53 eligible studies; all 53 included studies underwent quality assessment. Quantitative studies were evaluated using the Quality Assessment Tool, and Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist was used for qualitative research.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Research evidence on EOL communication with a focus on family.

Results

Four themes emerged from these studies: (1) conflicts in family decision-making in EOL communication, (2) the significance of timing of EOL communication, (3) difficulty in identification of a ‘key person’ who is responsible for decisions regarding EOL care and (4) different cultural perspectives on EOL communication.

Conclusions

The current review pointed towards the importance of family in EOL communication and illustrated that family participation likely leads to improved quality of life and death in patients. Future research should develop a family-oriented communication framework which is designed for the Chinese and Eastern contexts that targets on managing family expectations during prognosis disclosure and facilitating patients’ fulfilment of familial roles while making EOL decision-making. Clinicians should also be aware of the significance of the role of family in EOL care and manage family members’ expectations according to cultural contexts.

Keywords: palliative care, oncology, medical education & training

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This review offers a timely synthesis of research evidence of the role of family in end-of-life (EOL) communication.

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with frontline clinicians, academics and librarians to offer a diversified view towards a holistic understanding of the topic, study methodologies and study settings.

This review includes different research designs and methods including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies within the topic of family role in EOL communication.

As an integrative review, the themes emerged from the included studies can inform future research on developing a family-oriented communication framework that targets on managing family expectations when making EOL decision-making.

Findings have to be interpreted cautiously due to a number of studies included in this review are emerged from Chinese context.

Introduction

End-of-life (EOL) communication has a crucial influence on medical decision-making and the quality of care at the final stage of a patient journey. It informs patients and their families on the current medical conditions; explores unanswered concerns and health needs; provides emotional support and practical advice; reveals what lies ahead and allows care providers to understand how they can improve the care for the patients during their final days. EOL communication during palliative care removes the stigma around death and help the patients set out their final wishes to the family.1 In general, effective communication regarding prognoses and optimal treatment has multidimensional benefits, for instance, promoting the quality of EOL care and decreasing the stress of the carers.2 In contrast, poorly conducted medical conversations may lead to negative treatment outcomes such as aggressive life-sustaining treatments,3 4 unsatisfactory hospital experiences,5 poor well-being6 and unnecessary healthcare costs.2 7 Thorough EOL communication among clinicians, patients and carers help to alleviate anxiety and enable patients to be cared for in desired ways.2 8

However, empirical evidence shows that the EOL communication practice is not always performed effectively.9 10 Many patients and carers are reported to be poorly informed about their patients’ situations and that the patients were often unaware of their own risks of imminent deaths.11 Similarly, clinicians’ unawareness of patients’ wishes may hinder the provision of the most appropriate healthcare options for patients. Healthcare professionals also find it challenging to directly discuss deaths with patients and caregivers, as patients and caregivers are often being ill informed and tend to be overoptimistic on the prognoses.12 There are different expectations for palliative care in Chinese and Western cultures. Most Chinese patients rely on doctors to make the final decision regarding EOL treatments,13 14 the wishes of close family members are also considered. Research results show that in the broader Asian context, family members and religious beliefs heavily influence patients’ decisions on EOL and palliative care.15–17

Nowadays, many developed regions such as the USA, Europe and Australia adopt the shared decision-making approach to family–clinician EOL communication.18 However, patients who are admitted to general wards or intensive care units (ICUs) which are aggressively managed have no prior opportunities for effective discussions with their families or clinicians about their desires and goals.19 There is a lack of clear communication framework that sets the standard for essential information that family caregivers should receive, which will likely include patients’ current medical condition and prognosis estimates, additional options of treatment and support measures available and their risks and benefits, and the preferences of patients and family to guide clinicians to reach realistic care goals.20 21 When family members receive insufficient information, difficulties may arise during EOL communication. This occurs especially in the ICU settings, where urgent decisions about whether to pursue aggressive life-sustaining treatments for patients are required. In a study by Azoulay et al,22 54% of the family members of ICU patients did not have a clear understanding of the patients’ diagnoses, prognoses and treatments and the physician–family meetings lasted for no more than 10 min. As a result, family members have poor understandings of the situations they were facing, which led to suboptimal decision-making. In addition to time constraints, the lack of communication skills is also an important factor. Clinicians tended to discuss EOL life-sustaining treatments in a scripted, depersonalised and procedure-focused manner. Clinicians also tended not to initiate EOL conversation directly and in a timely manner.18

Among the factors affecting EOL communication as well as the engagement of patients and their family caregivers, the factor most discussed is cultural differences between the Eastern and Western countries. Chinese culture values collectivism, wherein patients prefer to make joint decisions with their family members or sometimes even rely completely on them.14 Rooted in Confucian morality, filial piety is a very important moral tenet in Chinese culture that has been advocated and practiced for thousands of years. People of the Chinese culture are required to provide care to their parents in return for the care they received from their parents in their childhood years. Therefore, many Chinese elderly patients believe that their children may naturally understand their preferences and are able to make decisions for them in their final days.14 23 24 For example, family members of elderly patients would request the doctors to discuss with them first, before the doctors consult the elder patient. In some cases, family members will also choose not to disclose the bad news to the patients.25 Collusion, a scenario wherein the family wishes to hide the diagnosis from the patient, is common in Asian cultures. In a study conducted in Singapore by Low et al26 found that 96% of family members expressed reluctance in disclosing the prognosis to the patient. This situation is also prevalent in Hong Kong, in which its culture is heavily influenced by both Chinese and Western beliefs. In research conducted with Chinese patients, maintaining a strong connection with the family during palliative care has been reported to be one of the most important components of a ‘good death’ for elderly patients.27 This interdependent relationship between family caregivers and patients opposes the ideology of autonomy and self-determination that predominate in Western culture, and is to a certain extent, culturally understood and accepted by patients in the Chinese context.

Regardless of the effects of different cultural norms, recent reports have shown that healthcare professionals widely agree that EOL communication should involve both the patient and family members.28 29 In one international survey of palliative care professionals, more than 80% of the participants agreed that more practical instructions during communication with patients’ family members would enhance EOL decision-making.29 30 Recently, the English Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman31 found that the main area of health professionals’ complaints about EOL care was communication failure with terminally ill patients and their family members. Without adequate family involvement, promoting the holistic care of patients during their EOL is difficult.

In response to such dissatisfaction with EOL communication, several guidelines have been established for practitioners with focus on individuals’ rights and autonomy in the medical context. Guidelines such as the COMFORT model (an acronym for Communication, Orientation, Mindfulness, Family, Ongoing, Reiterative messages and Team) and SPIKES protocol (an acronym for Setting, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Empathetic Response, Summary) provides a framework for clinicians to engage in palliative care discussion with patients.5 32 Meanwhile, existing recommendations mostly focus on the patient–clinician conversation rather than a family-oriented conversation. Many close family members are eager to thoroughly understand the dying process and the importance of understanding medical jargon, inclusivity, and full transparency33 is lost in the existing recommendations.

Due to the aforementioned factors, the development of an EOL communication strategy that considers active family involvement is necessary. While previous systematic reviews on family decision-making and involvement,34 nurse to family support during withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment and imminent death35 36 and EOL communication to patients and caregivers during the advanced stages of related illnesses37 are present, an integrative review is lacking. As such, in this integrative review, the researchers aimed to contribute to the current literature by systematically reviewing research findings that highlight the roles of patients’ families in EOL decision-making. The aim of the review was to answer the following question: What is the existing research evidence regarding the role of family in EOL communication, and what themes can be derived from their synthesis?

The summarised information sheds light on the role of family in EOL communication and decision-making and contributes to future research and policymaking regarding EOL communication. Although culture and its related elements regarding EOL communication and care have been heavily foregrounded thus far, it is not saliently marked in the research question because it is a prominent theme elicited after, rather than prior, the systematic review search (see also Pun et al38).

Methods

This integrative review aimed to provide integrated information on the role of family in EOL communication using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline as reporting system (see figure 1). The review included relevant studies published between 1 January 1991 and 31 December 2021. The purpose behind the proposed date is the majority of related studies and articles regarding familial roles in EOL communication were published since the specified date.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Moher et al.90 EOL, end-of-life; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Search strategy

PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE and the Ovid nursing databases were searched in the initial screening process to identify relevant articles using the following keywords and synonyms, such as ‘end of life’, ‘communication’ and ‘family’. The search restriction on the publication date was from 1991 to 2021. Search logic is also used to assist the search by using Boolean operators such as OR, AND, NOT, the search logic allows different combinations to access the most relevant studies (see online supplemental appendix 1 for the details on our search strategies). Specifically, the search strings of the four employed databases are presented as follows (see box 1)

Box 1. Search strings.

PsycINFO: abstract((family) OR (parent*) OR (caregiver*)) AND abstract((communicat*) OR (communication skill*)) AND abstract((“end of life”) OR (end-of-life) OR (EOL) OR (terminal) OR (terminally ill)) AND pd(19910101–20211231))

Embase: ((‘family’/exp) OR (parent*) OR (caregiver*)) AND ((communicat*) OR (communication skill*)) AND ((end of life) OR (end-of-life) OR (EOL) OR ((terminal) OR (terminally ill))

MEDLINE: ((“family”) OR (“parent*” OR “parent+”) OR (“caregiver*” OR “caregiver+”)) AND ((“communicat*” OR “communication+”) OR (“communication skill*”)) AND ((“end of life”) OR (“end-of-life”) OR ((“terminal”) OR (“terminally ill”))

Ovid nursing database: ((family) OR (parent*) OR (caregiver*)) AND abstract((communicat*) OR (communication skill*)) AND ((“end of life”) OR (end-of-life) OR (EOL) OR (terminal) OR (terminally ill))

bmjopen-2022-067304supp001.pdf (116.2KB, pdf)

In addition, a manual search was made of relevant journals, and the bibliographies of relevant articles and reviews were also cross-checked for potential eligible studies. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were included for further review and duplicated articles were removed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

An initial search was carried out to identify relevant articles on EOL communication that were published between 1 January 1991 and 31 December 2021. Studies were included if they were peer reviewed and concerned EOL communication and family. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (a) having a focus on topics that were unrelated to EOL communication (eg, religious studies of EOL care); (b) not being original research based on empirical findings (eg, literature reviews, opinion pieces); (c) being non-English-language articles; (d) being non-peer-reviewed studies.

Our investigation encompasses a broad scope. The various aspects of EOL care include EOL communication studies in general (ie, not limited to diagnosis, prognosis etc) (To avoid conflating EOL and palliative care, we mainly include studies that are primary focus on EOL topic but we note that some EOL studies may contain topic such as palliative care.) and focus on the involvement and roles of and between family, clinicians and relatives. Peer-reviewed full-text journal articles such as original studies and reviews were included. Furthermore, those relating to the Chinese context were especially retrieved and included as a subset of articles considering the effects of confucianism-influenced family culture in the Chinese context on EOL. The initially shortlisted articles were cross-checked by the three authors for final review and data extraction. Articles that were not peer-reviewed or written in English were excluded. Although we have a bilingual research team, EOL care articles that were written in Chinese were not included in the research due to insufficient peer-reviewed articles and the paucity of EOL communicative aspect-oriented research.

Data extraction

Three authors were involved throughout the entire title screening, data collection and text review process. Before data extraction, the authors independently screened the titles and read the whole abstract of each paper to exclude irrelevant articles according to the inclusion criteria. The full papers were retrieved if their abstracts were considered potentially relevant. The full texts of the chosen articles were subjected to in-depth data extraction. The objectives, research design, participant characteristics and key findings were examined and recorded and appraised for quality by oncologists and palliative care practitioners to ensure that all relevant journals were included in the search. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion to reach a consensus among all the authors.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Quality assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies39 was used to assess quantitative (n=14) and mixed-method studies (n=2). Each article was given ratings on a three-level ordinal scale: ‘weak’, ‘moderate’ or ‘strong’ in eight areas such as research design and selection of study population. Qualitative (n=37) and mixed-method studies (n=2) were evaluated with the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research,40 which is a 10-item checklist covering components such as congruity and reflexivity, scored as ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’ or ‘not applicable’. The quality of the included studies was evaluated independently by the first and second authors. Any disagreements in ratings were discussed and resolved with the third author.

Weight of evidence measure

To ensure the quality of the included studies, the papers’ ‘weight of evidence’ was measured according to three criteria: the relevance of each paper to the current review; the appropriateness of the research; the validity of the study and the overall contribution of the research to this review. These variables are specified in table 1.

Table 1.

Weight of evidence of the current review

| Relevance | Appropriateness | Validity | Overall contribution | |

| High | 46% | 28% | 38% | 30% |

| Medium | 40% | 38% | 45% | 43% |

| Low | 13% | 33% | 16% | 26% |

Regarding the relevance aspect of the included studies, that is, to which the degree of the topic(s) examined align with our review questions, 86% of the 53 reviewed articles were considered as either high or medium level of relevance. Appropriateness is evaluated based on whether the research designs were appropriately employed. The authors judged that 28% and 38% were deemed to be highly appropriate and fairly appropriate, respectively. Eighty-three per cent of the included studies were considered to have a medium-to-high level validity, where the scorings were based on the preciseness and consistency of data analysis. These ratings, therefore, draw an overall conclusion that 30% of the included studies were able to make a strong contribution in answering the review questions while 43% made a fairly significant contribution.

Included articles

The initial search identified 25 305 eligible studies, 25 318 of which were excluded after abstract screening. The search includes keywords and synonyms of ‘end of life’, ‘communication’ and ‘family’. Search logic are also used to assist the search through using Boolean operators such as OR, AND, NOT, the search logic allows different combinations to access the most relevant studies, for example, ‘end of life AND communication AND family’.

The full-text screening of the remaining 109 studies was then subjected to in-depth review (see figure 1). This led to the further exclusion of 56 articles because they: (a) focused on unrelated topics of family-oriented EOL communication; (b) lacked empirical evidence; (c) were written in other languages rather than English or (d) were not peer reviewed. Finally, 53 studies were included in this review.

The characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the 53 studies that met the inclusion criteria are summarised in table 2 (see online supplemental appendix 2 for a summary of each included study). The number of studies on the role of family in EOL communication increased significantly after 2010. Most of the studies were from the USA (24), closely followed by Hong Kong (7), Canada (4), the UK (3), China (2), South Korea (2), Netherlands (2), France (2) and other countries (7). Of the 53 included studies, 37 were qualitative studies, 14 were quantitative and 2 were mixed-method.

Table 2.

Main ideas of the themes emerged from the reviewed studies

| Theme | Main ideas | Studies |

| 1. Conflicts in family decision-making in EOL communication | There existed a certain degree of discrepancies in decision-making between the patient and family caregivers; to optimise EOL communication among the relevant stakeholders, physicians should be able to gauge and respond to the patient’s psychosocial needs and to also take the family’s perspective into account when having EOL conversations. | 9 20 23 29 44–54 |

| 2. The significance of timing of EOL communication | There is typically a delay in initiating EOL communication; it is often due to the avoidance of having open physician-patient discussion about the illness. Patients were generally worried about making EOL decisions once informed about the diagnosis, while physicians were concerned that the negative prognostic information would impact the patients and hence, leading to a late timing of EOL communication. | 22 26 49 50 55–61 |

| 3. Difficulty in identification of a ‘key person’ responsible for decisions regarding EOL care | Some patients were found to not wish to be involved in making their own palliative care decision out of the fear and uncertainty of their EOL stage, family members or even the physicians themselves might in turn have to be responsible for decision-making; this likely leads to an unclear division of responsibility regarding EOL decision-making. | 14 62–67 |

| 4. Different cultural perspectives on EOL communication | Individualism is of value in the West where most patients preferred having the autonomy to make EOL decision for themselves, while collectivism and filial piety are the main values typically found in Eastern society; patients tended to rely on their children or discussing within the family when making palliative care decisions. | 14 25 68–76 |

EOL, end-of-life.

Identified themes

Thematic analysis was conducted to capture any reoccurring topics in the included studies41 42. The coding process is inductive without referring to any existing coding framework. To do this, all the authors will first read through the transcripts carefully and give an initial free coding to all segments relevant to the role of family in EOL communication. We then conducted several review rounds to compare, sort and recode, as we look for connections among the coded segments and compared analyses from the other included papers. In this way, the authors identified and coded issues from each of the included studies, which were then synthesised into a set of broad reoccurring themes about the role of family in EOL communication.43 Four themes were identified: (1) conflict in family decision-making in EOL communication; (2) the significance of timing of EOL communication; (3) difficulty in identification of a ‘key person’ responsible for decisions regarding EOL care and (4) different cultural perspectives on EOL communication.

Conflicts in family decision-making in EOL communication

Internationally, the involvement of family members in EOL communication has often been discussed in the context of provision of support, but very few studies have directly explored how important the role of family is and in what way the family must be involved.

Family caregivers traditionally play their own unique roles in providing emotional and financial support to contribute to a ‘good death’— a pain-free situation during the last phase of life and not on exhausting possible treatments to prolong life unnecessarily— for the dying patients.20 44 In fact, the patients expect to receive family support more than the support from healthcare workers. Furthermore, the social support from family members serves as the fulfilment of their own familial obligations and is a foundation providing quality EOL care.45–47

Many clinicians nowadays have come to realise that the patients’ and families’ views and beliefs have to be considered in the decision-making process.20 29 In circumstances where disagreement about the medical advice arises between the doctor and the family, establishing a care plan could become difficult, and this could cause the withholding or withdrawal of treatment implementation. Family members have also noticed that healthcare staff would avoid EOL conversations. However, it is important for healthcare staff to initiate EOL conversations, so that patient’s needs and their family’s preferences are properly addressed.29 It was also found that some doctors have to follow the family’s wishes, even if it was against the professional judgement of what was appropriate for the patient.48–50 For instance, against the doctors’ recommendations, some family might still desire more unnecessary treatments just to sustain a dying patient’s life when he or she could not make an EOL decision.

Disagreements about decisions on EOL treatments could also occur between terminally ill patients and their family members. There are contradictions between family members who wish to hold onto their loved ones for as long as possible and the patients who wish to let go and reject life-sustaining treatments.51–53 Fan et al23 and Shin et al54 used standardised questionnaires to examine the preference and concordance among the patients with cancer, family members and clinicians regarding EOL communication. This includes the disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis, family involvement in such processes and EOL decision-making. Findings revealed that family members’ preferences did not always align with that of the patients in some cultural contexts such as China and Korea,23 54 for example, Shin et al54 found that discussions between patients and their family regarding treatment preferences might not always end in agreement, since patients’ family tended to opt for life-sustaining treatments when the patients desired otherwise. Fan et al23 suggested that mainland Chinese patients depended largely on their families and doctors tended to substitute patients’ consents with that of their families. Additionally, there are discrepancies between clinicians’ medical practice and the preferences of the patients and their family caregivers. For instance, rigid protocols and guidelines that inform the healthcare of the young patients created tension among family caregivers and clinicians as they did not take into account the patients’ individual needs.9

The significance of timing of EOL communication

Owing to the complexity of EOL communication, that is, the constitution of delivering exhaustive information from doctors, the complicated emotions derived from relevant stakeholders and the dynamics of family involvement in the patient’s healthcare, there typically appears a delay in conducting EOL communication.49 50 55 Cherlin et al55 found that the communication between family caregivers and clinicians about the terminal illness and possible use of hospice care occurs late in the course of the illness. Some patients consistently wrestled with the thought of knowing that they were ill and trying to defer EOL decisions.56–58 From the perspective of clinicians, there seems to be a tendency for clinicians to initiate the communication of negative prognostic information until they reach a perceived ‘threshold’ of certainty in the accuracy of a prognosis.56 This observation corroborates with those of Lind et al,58 who discovered that the doctor’s directive to ‘wait and see’ may cause miscommunication between the doctor and family members. One possible reason for the delayed initiation of EOL conversations from doctors might be due to their lack of incompetent communication skills, in which many of them were unable to discuss EOL issues with the patients and the families in an effective and timely manner.59 Yet, this directive to further delay diagnosis could potentially give the family a sense of false hope that the patient’s situation can be improved. When miscommunication occurs, it would appear to be too late to conduct proper EOL communication or for family members to provide input in the decision-making process about terminating treatment.

Another potential reason why EOL communication may not be implemented in a timely fashion is the presence of physician–family collusion, a situation where family members choose to hide the diagnosis and prognosis from the patients; and it is not uncommon in the palliative care context. Notwithstanding the fact that collusion goes against medical ethics and can potentially cause various complications in EOL treatment, admittedly, collusion is widely seen across Europe and Asia.26 This is because of the fear of disappointing the patients by informing them of their deteriorating health condition, and more prevailing in Asian countries that the social norm of holding family members to be responsible for the main body of communication about EOL care.

The failure to have patients engage in timely EOL conversations can lead to aggressive life-sustaining treatments, underutilisation of palliative care and negative outcomes for both patients and their families. Patients’ psychological conditions, including depression scores and quality of life metrics, will be compromised without good palliative care. Moreover, introducing palliative care relieves caregiver stress and improves caregiver depression scores.22 57 As a result of these side effects, clinical prediction models to provide estimated remaining survival time of the patient have started to gain popularity in medical practices to aid the EOL discussion pacing of clinicians.

Proper and prompt palliative care referrals are also important. Frameworks for effective EOL communication could also encourage clinicians to identify an optimal time to refer the patient to palliative care.60 61

Difficulty in identification of a ‘key person’ who is responsible for decisions regarding EOL care

Communication required to negotiate EOL care extends beyond the patients and the doctors. It also includes the patients’ families, especially in the context of Asia, which family-oriented practices prevail.14 Families may wish to take up the responsibility for the patient’s EOL care. The involvement of multiple parties often leads to difficulty in identifying a main person to hold responsibility for making palliative care decisions.

Failure to identify a key person among family members in EOL care and conversations can cause confusion and misunderstanding, undermining decision-making and contributing to a confused process which is already fraught with uncertainty.62 63 Unclear responsibilities and responses can create contradictory expectations between the family members and the patient. Discrepancies have been observed between the last wishes of patients to follow the natural course comfortably and the desire of their family members to hold on to their loved ones for as long as possible.64 65 Even when the decision-making responsibility is delegated to one family member, their decisions may be affected by contradicting opinions within the family.66 To further complicate the matter, McDarby et al67 showed that elderly parents’ EOL preferences may not be understood by their children. Consequently, misunderstanding and a lack of communication between the patients and their families emerge, resulting in confusion and disagreements in the EOL decision-making process.

Different cultural perspectives on EOL communication

Sociocultural factors play a significant role in EOL communication. In the West, individualism and autonomy are emphasised. EOL communication usually occurs between the doctor and the patient. Depending on the patient’s wishes, family members may also be involved.25 Although there are significant cultural differences between Chinese and Western regions, clinicians of Chinese contexts undertake the same EOL communication models adopted by clinicians from the West.25 They would look for social cues such as the nonverbal communication behaviour including tone of voice, manner and attitude, to determine the readiness of patients to engage in EOL conversations. However, the implications of these social cues may differ by cultures. Heavy reliance on social cues leads to miscommunication. In certain cultural contexts, understanding the non-verbal cues from patients is essential to perceiving their readiness with EOL communication and to help (re)calibrate the conversation flow; thus, potentially making non-verbal communication even more crucial than the verbal content (see also McElroy et al and Schonfeld et al68 69). These factors influence the agencies manifested across the multiple parties, which potentially contribute further to the EOL decision-making conflicts. Meanwhile, in Chinese contexts, EOL communication is largely affected by sociocultural factors. Decisions are made as a collective family rather than between the individual patient and doctor.70 Studies have shown that some patients do not wish to be involved in the decision-making process of their treatments even if it concerns their own life. This belief is prevalent among Chinese patients. Due to the Chinese cultural beliefs, dying Chinese patients prefer to let their children make the EOL decisions. Bowman and Singer14 reported that the role of family in the Chinese culture emphasises interdependency, obligation and responsibility to others. Family members in a Chinese family are expected to be responsible for protecting the patient’s health, safety and general well-being. Chinese patients believe in their children’s ability to make decisions on their behalf and see no need for advance directives about treatment or communication on EOL needs, resulting to increased miscommunication and misunderstanding about the patient’ s needs.

Similar findings were observed in Eastern countries, where Asian family members typically preferred to be involved in making EOL decisions together with, or sometimes, on behalf of the elderly patients.25 71–74 In China and nations of proximity such as Korea, where Chinese culture poses significant impact, EOL decision-making tends to be a family-centred practice rather than an individual decision.73 75 76 Alternatively, Kato and Tamura74 offered relational authority as another dynamic found within East Asian cultures, where family members will leave medical decisions to the clinicians. Kato and Tamura’s74 study also stresses that family members felt a great responsibility to care for their parents and that failure to continue the care, such as admitting their parents to a nursing home, led to feelings of guilt and abandonment among the family members. This is because the ideology behind it, which is constructed from traditional Confucianist and Buddhist beliefs, largely focuses on collectivism and familial responsibility. Filial piety is a key value to maintain social stability and familial harmony. Based on this premise, parents become the recipients of their adult children’s care, and children of dying patients are highly trusted in making treatment plans and EOL decisions for their parents.71 73–75 In addition, in the East Asian context, immediate family members generally possess the power to decide whether to inform the patient of their current medical situations,25 creating a common phenomenon where the doctors would have consultations with the family caregivers prior to speaking with the patients.

Discussion

This review identified the significance of family members in EOL communication and how their engagement in EOL discussions can improve the quality of patients’ EOL and death. Moreover, this review found that there is a need for Chinese and East Asian-specific EOL communication model to address cultural needs of elderly patients. An important trend identified in the included studies is the accumulating body of knowledge on the significance of family on care, support as well as communication with the patients. Open discussions initiated by clinicians are key to decreasing psychological side effects in patients and family members such as anxiety, psychological stress and pressure.77

Referencing to the research question, existing research about familial roles in EOL communication can be categorised into four different themes. As discussed, family can be a prominent source of decision-making conflict in EOL communication. For instance, family caregivers may have to perform the role of the patient’s ‘doctor’ in home-based care by assessing the patient’s symptoms, administering drugs and providing hands-on care. With little to no support from professional healthcare staff, home care becomes the very source of anxiety and stress for the carer.78 Decision-making conflicts could also occur between the family and clinicians, and the family and the patient, particularly if resources for support from professionals were limited. It goes without saying that these conflicts do affect the provision of holistic and effective care for the patient.78 Not only that, the lack of identifying a key person responsible for EOL decision-making results in decision-making conflict. These conflicts could result in significant delays of exercising EOL treatments.

Despite the associated challenges and issues of involving family in the decision-making process, families are an important source of support for patients who are undergoing EOL care. Family support could be manifested through providing the basic needs of the patient (ie, helping to make the patient more comfortable, offering food and drinks, etc), monitoring the patient’s emotional status and offering immediate support and assistance.45 49 Family participation in EOL matters is also found to be negatively correlated with the level of psychological distress in bereaved family caregivers, implying that the more the family members engage in the patient’s EOL journey, the lesser extent they experienced psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression since the patient’s departure.77–80 Chui and Chan’s81 research echoes this finding, demonstrating that longer EOL discussions could significantly reduce the incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression of the families of patients who died in the ICU. On the other hand, Mitchell et al’s9 findings noted that there was insufficient time for family caregivers to consider the possibility of death, as avoiding the possibility served as a coping mechanism for the caregiver and the life-threatening aspect of the patient’s condition was only acknowledged after an episode was resolved. As for the impact on the patients, Byock’s82 clinical observation revealed that despite the typical suffering at the EOL, the quality of family input during EOL discussions, such as careful, relationship-appropriate and goal-directed EOL communications, was important for the patient’s emotional well-being and the overall experience towards the EOL stage. Thus, quality communication between the patients and their family members is vital in improving the quality of life of dying patients during their EOL stage.44 46 51

Considering the value that familial support could have, healthcare workers must learn what is important to the patients and their families and ensure that their preferences are adequately explored, adhered to and respected even in cases where their preferences contradict the clinician’s decision. From the clinician’s point of view, EOL communication is most effective when family members participate and engage in the joint decision-making discussion.20 83 Fostering positivity in EOL communication as a clinician was also viewed to be important.29 When family members and patients clearly understand one another’s EOL preferences, decisions on treatments and palliative care could effectively address patients’ needs.79

There is also plenty of material to discuss with the significance of timing in EOL communication. With regards to physician–family discussions, clinicians should be equipped with the competency to explain its negative effects on the patient and family members in an empathetic and compassionate way as well as encourage communication between family members and the patients, so that family members could understand the patients’ wishes and explain their diagnoses.26 Clinicians should also be educated to take on a bridging role between family members and the patients, acting as a facilitator of communication and exploring any unspoken issues that either side are intentionally avoiding. As such, with continual training and education, healthcare professionals could develop effective communication skills for palliative care and collaborate with the patients’ families to provide quality EOL care. Furthermore, healthcare providers should act as mediators and advisors to assist both parties in making appropriate treatment decisions and thus enable the patients to have a ‘good death’.14 The barriers and uncertainties among the patients, family members and the clinicians should be moderated to build trust and facilitate open EOL communication.64 84

Moreover, healthcare providers may be capable of initiating EOL conversations at optimal timing with widespread adoption of prognostic tools. When EOL discussions are conducted at optimal timing, patients’ comfort and dignity during EOL could be immensely improved.55 The Palliative Care Chart developed by Bailey et al51 is a tool for clinicians to assists in generating effective EOL communication, aiming to facilitate continuity and co-ordination of care and sense of partnership between patients and their families. The chart serves as a checklist for clinicians. Together with the training on use of the tool, results showed that clinicians were able to resolve ongoing concerns occurred between the patients and family members during palliative discussions. Another means to educate healthcare professionals to provide better palliative care is the development of quality indicators as suggested by Raijmakers et al.30 Clinicians can be trained to monitor different aspects of the patient according to the quality indicators, for instance, limited need for pain control, providing palliative care accordingly and improving the patients’ quality of life towards the last stages of their lives. Educational interventions may be one way to raise the awareness and significance of patient participation in EOL planning. As suggested in this review, family participation in the process of EOL discussions should also be considered. Family participation in EOL communication was shown to have positive effects on the patients’ quality of EOL treatment receptions.21 61 However, the degree of involvement varies between Eastern and Western countries given cultural differences, requiring a Chinese and Eastern-specific communication model to address the cultural implications of different regions. Chinese patients and families commonly avoid EOL communication due to Buddhism and Confucianism beliefs, which accepts that talking about death brings death closer.14 These beliefs also emphasise a balance of physical, emotional and social harmony, which provides a culturally sound reason for them to evade such conversations regarding palliative care and EOL decisions.14 61 Also, in China, specifically, filial piety plays an important role in the conduct of children. In cases of medical care, the burden of making treatment decisions and EOL choices is usually delegated to the children of elderly patients.14 24 57 85 Some elderly patients may even choose to exclude themselves from the EOL communication between clinicians and family caregivers and family members would become the first and main persons to contact during the discussion about their conditions and EOL decisions.11

In Western countries, contrarily, patients and elderly people are generally familiar with palliative care. The awareness of setting up wills and arranging palliative care enable them to be relatively prepared to engage in early EOL conversations.65 Furthermore, autonomy and self-determination are prevailing concepts, and patient’s self-exclusion during medical consultation is rarely observed. Given the prevalence of individualism, most patients of the Western contexts wish to make EOL decisions for themselves.69 86 In occasional circumstances, patients prefer to withhold information on diagnosis and treatments to their family members, this would lead to a lack of communication87 as well as insufficient understanding of the illness among family members and, hence, compromised preparedness in dealing with their beloved’s EOL issues.81

Prior research also addressed potential solutions to improve the quality and communicative environment of EOL care. Effective EOL communication is essential in creating a fulfilling EOL experience for the patients and their family members, while advance preparation could help achieve successful EOL conversations. As the majority of patients trust that their healthcare providers are capable of providing quality treatment, diagnosis and other information regarding their illness. Clinicians could build good rapport over time and establish trust with patients.57 This promotes patient-centred care, which is vital for effective EOL communication in both Eastern and Western contexts as the patients’ needs are always top priority when the doctors are developing medical plans. To attain such patient-oriented practices, clinicians must address the elements of (1) sensitivity to the patients’ needs, personal experiences and perspectives, (2) self-participation of the patients’ own recovery journey and (3) enhancement of doctor–patient relationships.

It is also critical to keep the patients informed about their diseases. In a previous study,62 half of the respondents reported that neither were they notified about the diagnosis and prognoses nor did they fully understand the information provided by doctors. Clinicians should have regular meetings with the patients and family members to keep them up to date on the disease progress and prognoses. Advance notification of the nature of the meeting as well as the provision of a quiet and calm atmosphere could help decrease the anxiety of family members. Issues regarding the manner of delivery are present as well; when delivering bad news, clinicians were typically found not to have a specific goal or did not consider ahead how would the news impact the receiver.69 All these can become obstacles in conducting effective consultation as well as disclosing the unpleasant news to the patients. To balance both medical and interpersonal needs in such difficult EOL discussions, there are developed protocols to help clinicians to better approach the conversation. One example being ‘COMFORT model, which is a step-by-step guide on breaking bad news in a humane manner and at the same time, providing comfort to the recipient.32 87 ‘SPIKES’ protocol, which is a six-step framework, assists doctors with proper preparation in delivering bad news while ensuring the patients’ comfort and understanding of the discussion.5 88 While these protocols were developed and validated in the Western context; since sociocultural factors play a significant role in doctor–patient communication, they may not be applicable in non-Western nations due to the different traditional beliefs in the East.89 More specifically, the Chinese philosophy of death being a taboo subject has wide influences across many Asian countries, resulting in hesitation of prognosis disclosure to dying patients. Having communication frameworks as a guideline for clinicians to navigate around EOL conversations is plausible; yet, a formulaic approach without cultural considerations of the patients could reduce patient satisfaction. Clinicians, therefore, need to adapt to families on a case-by-case basis while considering the nuances of patient perspective, context of the discussion and content of the conversation, so that they can adjust the communication accordingly.11

Finally, clinicians should attend to the family caregivers’ expectations according to the cultural context. They need to understand and respect the expectations of the patient and their family regarding the treatment. Differences in preferences and the lack of communication between medical professionals and patients are known to create conflicts. Careful listening and understanding the patients’ preferences enhance the quality of patients’ dying process.23 In addition, a one-size-fits-all approaches do not work in EOL communication due to the variety of factors.24 It is essential to improvise discussions according to each patient and family needs. Moreover, keeping the general cultural guidelines in mind enables clinicians to connect with their patients more precisely in respect of different scenarios regardless of the cultural backgrounds of both parties. More research is warranted to investigate how clinicians could and should communicate with different patients, by looking for the best model to assess the need and preference in communication. Medical staff must be trained to be prepared for providing a smooth EOL communication experience to patients based on their cultural backgrounds and practice.24

Strengths and limitations of the study

This review has synthesised the research findings from a range of diversified data sources in order to produce a comprehensive view towards the understanding of family role in EOL communication. To our best of knowledge, there is limited research on exploring the role of family in EOL communication, this review fills in the gap by highlighting the importance of culture and how it can affect the beliefs and roles of families in EOL decision-making. Better family-oriented EOL communication suggests that family participation will likely lead to improved quality of life and death in patients, managing family expectations during prognosis disclosure and facilitating patients’ fulfilment of familial roles while making EOL decision-making. While patients from the East depend on their family members to make EOL decisions, this paper urges for a family-oriented framework, which helps patients to fulfil their social role in the family.

There are several limitations in this review. First, the literature search only includes four databases, with only 53 eligible included articles and many are quantitative studies, leading to a possible bias of the literature representation. Second, studies written in other languages were not included. Only those fully published in English were reviewed and included in this study, which may have skewed our findings and interpretations. The included articles were not be able to cover all aspects of family in EOL communication, which may have affected the generalisability of the findings. Third, in our analysis, we use the signposting of ‘the East and the West’ which is beneficial in distinguishing EOL communicative practices across different cultural contexts, we also acknowledge the generalisability of such labelling; there are many additional factors which contribute to the complexity of EOL communication. Readers are reminded to interpret the findings cautiously due to a number of studies included in this review are emerged from Chinese context.

Conclusion

This review identified the important and unique roles of family caregivers in EOL communication and the pressing need to develop an EOL communication framework designed for the Chinese and Eastern contexts. The reviewed studies indicated that family engagement in EOL discussions is beneficial for both patients and their family members. Knowledge about the patient’s diagnosis and prognosis information factoring in EOL decisions will facilitate fruitful communication among healthcare providers, patients and family members. Clinicians should identify and remove barriers to enable sufficient understanding of the information desired by each party, tackle collusions tactfully and bridge the gap between the parties if direct communication is difficult and distressing. The timing of EOL communication and communicative content is important, especially in circumstances where clinical deterioration is inevitable. Existing palliative care communication frameworks, such as the COMFORT model and SPIKES protocol, could be modified according to the implications of this review to fit the family-oriented cultures in Chinese and Eastern contexts. With such guiding principles, clinicians will be able to engage and discuss EOL issues with patients confidently, thus performing a well-rounded EOL communication practice.

The current review identified four significant themes that presented the roles of family caregivers in EOL communication. Many of the articles in the review search in the results and discussion show the involvement of family members in EOL decision-making. Clinicians should acknowledge the significance of families’ views during the decision-making process. It is paramount to respect and understand the decisions of the patient and the family, while also acting as a bridge to mediate between them and facilitate open discussions. Clinicians can also use prediction models or prognostic tools to predict the patients’ survival time to ensure a timely EOL conversation to prepare for the end of their life.

Previous studies showed that programmes introducing advance care planning and acculturation could successfully encourage patients to participate in EOL communication with their palliative care team and family caregivers.24 57 However, while previous palliative care tools have shown to improve doctor–patient interaction, a lot of them do not focus on further factors that contextualise and complicate EOL communication, such as sociocultural factors, patient-centred care and patient autonomy. Palliative care tools can be designed to be inclusive of family involvement in EOL communication, reflecting both the role of family members and patients’ individual role with respect to their families. Regarding clinicians and practitioners’ EOL communication praxis, our recommendations are twofold. The first is to be continually aware of the cultural implications. The second is for clinicians to be trained, so that they can help the patient negotiate personal and familial obligations while undergoing EOL treatments.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JP contributed to the conception and design of the study. KMC, LF and JCHC revised the study protocol. JP, KMC, LF and CHJC contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. JP evaluated the risk of bias of the included studies. JP and KMC interpreted the data. JP, LF and KMC drafted the manuscript. All the authors critically revised the manuscript and gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Buckman R. Communication in palliative care: a practical guide. In: Death, dying and bereavement. 2nd edn. London: Sage, 2000: 146–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force . Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clayton JM, Hancock KM, Butow PN, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness, and their caregivers. Med J Aust 2007;186:S77–105. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odgers J, Fitzpatrick D, Penney W, et al. No one said he was dying: families’ experiences of end-of-life care in an acute setting. Aust J Adv Nurs 2018;35:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5:302–11. 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson N, Knott CI. Stress and burnout in intensive care medicine: an Australian perspective. Med J Aust 2017;206:107–8. 10.5694/mja16.00626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:480–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maubach N, Batten M, Jones S, et al. End-of-life care in an australian acute hospital: a retrospective observational study. Intern Med J 2019;49:1400–5. 10.1111/imj.14305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell S, Slowther AM, Coad J, et al. Experiences of healthcare, including palliative care, of children with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions and their families: a longitudinal qualitative investigation. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:570–6. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng GWY, Pun JKH, So EHK, et al. Speak-up culture in an intensive care unit in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional survey exploring the communication openness perceptions of Chinese doctors and nurses. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015721. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pun JKH, Cheung KM, Chow JCH, et al. Chinese perspective on end-of-life communication: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020:bmjspcare-2019-002166. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-002166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawryluck L. Communication with patients and families. In: Ian Anderson continuing education program in end-of-life care. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Food and Health Bureau . End-of-life care: legislative proposals on advanced directives and dying in place - consultation document. 2019. Available: https://www.fhb.gov.hk/download/press_and_publications/consultation/190900_eolcare/e_EOL_care_legisiative_proposals.pdf

- 14.Bowman KW, Singer PA. Chinese seniors’ perspectives on end-of-life decisions. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:455–64. 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00348-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Huang Y, Radha Krishna L, et al. Role of the nasogastric tube and lingzhi (ganoderma lucidum) in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:794–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng NH, Liu HL, Chen CH, et al. Cultural practices and end-of-life decision making in the neonatal intensive care unit in Taiwan. J Transcult Nurs 2012;23:320–6. 10.1177/1043659612441019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miljeteig I, Johansson KA, Sayeed SA, et al. End-Of-Life decisions as bedside rationing. An ethical analysis of life support restrictions in an Indian neonatal unit. J Med Ethics 2010;36:473–8. 10.1136/jme.2010.035535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin TT, Moreno B, Silvester W, et al. End-Of-Life communication in the intensive care unit. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:433–42. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung DYP, Chan HYL, Yau SZM, et al. A video-supported nurse-led advance care planning on end-of-life decision-making among frail older patients: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:1360–9. 10.1111/jan.13959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohs JE, Trees AR, Gibson C. Holding on and letting go: making sense of end-of-life care decisions in families. Southern Communication Journal 2015;80:353–64. 10.1080/1041794X.2015.1081979 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keeley MP. Family communication at the end of life. Behav Sci (Basel) 2017;7:45. 10.3390/bs7030045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3044–9. 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan Z, Chen L, Meng L, et al. Preference of cancer patients and family members regarding delivery of bad news and differences in clinical practice among medical staff. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:583–9. 10.1007/s00520-018-4348-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwak J, Haley WE. Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. Gerontologist 2005;45:634–41. 10.1093/geront/45.5.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q. Doctor-patient communication and patient satisfaction: A cross-cultural comparative study between china and the US. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low JA, Kiow SL, Main N, et al. Reducing collusion between family members and clinicians of patients referred to the palliative care team. Perm J 2009;13:11–5. 10.7812/TPP/09-058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo RS, Woo J, Zhoc KC, et al. Cross-Cultural validation of the McGill quality of life questionnaire in Hong Kong Chinese. Palliat Med 2001;15:387–97. 10.1191/026921601680419438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almack K, Cox K, Moghaddam N, et al. After you: conversations between patients and healthcare professionals in planning for end of life care. BMC Palliat Care 2012;11:15. 10.1186/1472-684X-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kastbom L, Karlsson M, Falk M, et al. Elephant in the room-family members’ perspectives on advance care planning. Scand J Prim Health Care 2020;38:421–9. 10.1080/02813432.2020.1842966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raijmakers N, Galushko M, Domeisen F, et al. Quality indicators for care of cancer patients in their last days of life: literature update and experts’ evaluation. J Palliat Med 2012;15:308–16. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The English Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman . The ombudsman’s annual report and accounts 2015-16 (rep). 2016. Available: https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/sites/default/files/PHSO_Annual_Report_2015-16.pdf

- 32.Wittenberg E, Goldsmith JV, Ragan SL, et al. Communication in palliative nursing: the COMFORT model. Oxford University Press, 2019. 10.1093/med/9780190061326.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paré K, Grudziak J, Lavin K, et al. Family perceptions of palliative care and communication in the surgical intensive care unit. J Patient Exp 2021;8:23743735211033095. 10.1177/23743735211033095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson RJ, Bloch S, Armstrong M, et al. Communication between healthcare professionals and relatives of patients approaching the end-of-life: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Palliat Med 2019;33:926–41. 10.1177/0269216319852007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coombs MA, Parker R, Ranse K, et al. An integrative review of how families are prepared for, and supported during withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in intensive care. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:39–55. 10.1111/jan.13097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowey SE. Communication between the nurse and family caregiver in end-of-life care. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2008;10:35–45. 10.1097/01.NJH.0000306712.65786.ae [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker SM, Clayton JM, Hancock K, et al. A systematic review of prognostic/end-of-life communication with adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness: patient/caregiver preferences for the content, style, and timing of information. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:81–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pun JKH, Chan EA, Wang S. Health professional-patient communication practices in east asia: an integrative review of an emerging field of research and practice in hong kong, south korea, japan, taiwan, and mainland china. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:1193–206. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas H, Ciliska D, Dobbins M. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. toronto: effective public health practice project mcmaster university. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joanna Briggs . JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research. 2017. Available: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/criticalappraisal-tools/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017.pdf

- 41.Bryman A. Social research methods. Oxford university press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:1–0. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters MDJ. Managing and coding references for systematic reviews and scoping reviews in endnote. Med Ref Serv Q 2017;36:19–31. 10.1080/02763869.2017.1259891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Githaiga JN, Swartz L. Socio-cultural contexts of end- of- life conversations and decisions: bereaved family cancer caregivers’ retrospective co-constructions. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:1–8. 10.1186/s12904-017-0222-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee MK, Yun YH. Family functioning predicts end-of-life care quality in patients with cancer: multicenter prospective cohort study. Cancer Nurs 2018;41:E1–10. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Royak-Schaler R, Gadalla S, Lemkau J, et al. Family perspectives on communication with healthcare providers during end-of-life cancer care. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006;33:753–60. 10.1188/06.ONF.753-760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Towsley GL, Hirschman KB, Madden C. Conversations about end of life: perspectives of nursing home residents, family, and staff. J Palliat Med 2015;18:421–8. 10.1089/jpm.2014.0316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaunfield SL. It’s a very tricky communication situation: acomprehensive investigation of end-of-life family caregiver communicationburden. Theses and Dissertations-Communication 2015;43. Available: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/comm_etds/43 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong MY-F, Chan SW-C. The qualitative experience of Chinese parents with children diagnosed of cancer. J Clin Nurs 2006;15:710–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. Silence and cancer: why do families and patients fail to communicate? Health Commun 2003;15:415–29. 10.1207/S15327027HC1504_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bailey S, Sellick SM, Setliff AE, et al. Communication at life’s end [A patient held palliative care chart facilitates communication]. Can Nurse 1999;95:41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kramer BJ, Kavanaugh M, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Predictors of family conflict at the end of life: the experience of spouses and adult children of persons with lung cancer. Gerontologist 2010;50:215–25. 10.1093/geront/gnp121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kotecho M, Adamek ME. GENDER differences in quality of life of urban elders in ethiopia. Innovation in Aging 2017;1:879–80. 10.1093/geroni/igx004.3159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin DW, Cho J, Kim SY, et al. Discordance among patient preferences, caregiver preferences, and caregiver predictions of patient preferences regarding disclosure of terminal status and end-of-life choices. Psychooncology 2015;24:212–9. 10.1002/pon.3631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, et al. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: when do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med 2005;8:1176–85. 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carrese JA, Rhodes LA. Western bioethics on the Navajo reservation. benefit or harm? JAMA 1995;274:826–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang HL, Chiu TY, Lee LT, et al. Family experience with difficult decisions in end-of-life care. Psychooncology 2012;21:785–91. 10.1002/pon.3107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lind R, Lorem GF, Nortvedt P, et al. Family members’ experiences of “ wait and see ” as a communication strategy in end-of-life decisions. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:1143–50. 10.1007/s00134-011-2253-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Pirl WF, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care on caregivers of patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Oncologist 2017;22:1528–34. 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014;120:1743–9. 10.1002/cncr.28628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rhoads S, Amass T. Communication at the end-of-life in the intensive care unit: A review of evidence-based best practices. R I Med J 2019;102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Biola H, Sloane PD, Williams CS, et al. Physician communication with family caregivers of long-term care residents at the end of life. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:846–56. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan WCH. Being aware of the prognosis: how does it relate to palliative care patients’ anxiety and communication difficulty with family members in the Hong Kong Chinese context? J Palliat Med 2011;14:997–1003. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Im J, Mak S, Upshur R, et al. Patient and family related barriers of integrating end-of-life communication into advanced illness management. J Pain Sympt Manage 2018;56:e58–9. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Im J, Mak S, Upshur R, et al. “Whatever happens, happens” challenges of end-of-life communication from the perspective of older adults and family caregivers: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18:113. 10.1186/s12904-019-0493-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trees AR, Ohs JE, Murray MC. Family communication about end-of-life decisions and the enactment of the decision-maker role. Behav Sci (Basel) 2017;7:36. 10.3390/bs7020036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McDarby M, Picchiello M, Kozlov EK, et al. ADULT children’S understanding of parents’ care and living preferences at end of life. Innovation in Aging 2019;3:S668–9. 10.1093/geroni/igz038.2473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McElroy JA, Proulx CM, Johnson L, et al. Breaking bad news of a breast cancer diagnosis over the telephone: an emerging trend. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:943–50. 10.1007/s00520-018-4383-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schonfeld TL, Stevens EA, Lampman MA, et al. Assessing challenges in end-of-life conversations with elderly patients with multiple morbidities. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:260–7. 10.1177/1049909111418778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ayers NE, Vydelingum V, Arber A. An ethnography of managing emotions when talking about life-threatening illness. Int Nurs Rev 2017;64:486–93. 10.1111/inr.12356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan WCH, Epstein I, Reese D, et al. Family predictors of psychosocial outcomes among hong kong chinese cancer patients in palliative care: living and dying with the “support paradox.” Soc Work Health Care 2009;48:519–32. 10.1080/00981380902765824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ho AHY, Chan CLW, Leung PPY, et al. Living and dying with dignity in Chinese Society: perspectives of older palliative care patients in Hong Kong. Age Ageing 2013;42:455–61. 10.1093/ageing/aft003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tse CY, Chong A, Fok SY. Breaking bad news: a Chinese perspective. Palliat Med 2003;17:339–43. 10.1191/0269216303pm751oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kato H, Tamura K. Family members’ experience of discussions on end-of-life care in nursing homes in Japan: a qualitative descriptive study of family members’ narratives. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2020;22:401–6. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ko E, Roh S, Higgins D. Do older korean immigrants engage in end-of-life communication? Educat Gerontol 2013;39:613–22. 10.1080/03601277.2012.706471 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zheng R-S, Guo Q-H, Dong F-Q, et al. Chinese oncology nurses’ experience on caring for dying patients who are on their final days: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:288–96. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abbey JG. Communication about end-of-life topics between terminally ill cancer patients and their family members. 2008.

- 78.Salifu Y, Almack K, Caswell G. “My wife is my doctor at home”: A qualitative study exploring the challenges of home-based palliative care in A resource-poor setting. Palliat Med 2021;35:97–108. 10.1177/0269216320951107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-of-life care? opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1339–44. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scott AM. Family conversations about end-of-life health decisions. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chui WY-Y, Chan SW-C. Stress and coping of hong kong chinese family members during a critical illness. J Clin Nurs 2007;16:372–81. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01461.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Byock IR. The nature of suffering and the nature of opportunity at the end of life. Clin Geriatr Med 1996;12:237–52. 10.1016/S0749-0690(18)30224-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ohs JE, Trees AR, Kurian N. Problematic integration and family communication about decisions at the end of life. Journal of Family Communication 2017;17:356–71. 10.1080/15267431.2017.1348947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Van den Heuvel LA, Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life communication in advanced chronic organ failure. Int J Palliat Nurs 2016;22:222–9. 10.12968/ijpn.2016.22.5.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peterson LJ, Hyer K, Meng H, et al. FACTORS associated with whether older adults discuss their EOL care preferences with family members. Innov Aging 2018;2:843. 10.1093/geroni/igy023.3141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colletti L, Gruppen L, Barclay M, et al. Teaching students to break bad news. Am J Surg 2001;182:20–3. 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00651-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Villagran M, Goldsmith J, Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al. Creating comfort: a communication-based model for breaking bad news. Communication Education 2010;59:220–34. 10.1080/03634521003624031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schapira L. Delivering bad news to patients and their families. In: Tumors of the chest 2006. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, n.d.: 597–605. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Labaf A, Jahanshir A, Shahvaraninasab A. Difficulties in using western guidelines for breaking bad news in the emergency department: the necessity of indigenizing guidelines for non-western countries. J Med Ethic History Med 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-067304supp001.pdf (116.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.