Abstract

A new strategy is described for the Lewis base-catalyzed bromochlorination of unsaturated systems that is mechanistically distinct from prior methodologies. The novelty of this method hinges on the utilization of thionyl chloride as a latent chloride source in combination with as little as 1 mol % of triphenylphosphine or triphenylphosphine oxide as Lewis basic activators. This metal-free, catalytic chemo-, regio-, and diastereoselective bromochlorination of alkenes and alkynes exhibits excellent site selectivity in polyunsaturated systems and provides access to a wide variety of vicinal bromochlorides with up to >20:1 regio- and diastereoselectivity. The precision installation of Br, Cl, and I in various combinations is also demonstrated by simply varying the commercial halogenating reagents employed. Notably, when a chiral Lewis base promoter is employed, an enantioselective bromochlorination of chalcones is possible with up to a 92:8 enantiomeric ratio when utilizing only 1–3 mol % of (DHQD)2PHAL.

Organic halides represent a valuable class of compounds, pervasive among commodity chemicals, pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and over 5000 natural products.1,2 More so, organohalides find routine use as versatile synthetic intermediates capable of participating in nucleophilic displacement, radical-mediated exchange, and various cross-coupling reactions.3 These chemical transformations enable halogen-bearing carbons to serve as handles for the precision forging of new C–C and C–heteroatom bonds. Chlorine- and bromine-containing compounds represent the two most widely employed classes of organohalides used in industrial manufacturing.1f

The intra- or intermolecular capture of transient halonium intermediates with nucleophilic heteroatoms represents a reliable strategy for the introduction of new carbon-halogen bonds.4 More specifically, when the nucleophile is a halide, the stereospecific vicinal dihalogenation of alkenes is achieved, of which dibromination and dichlorination have been extensively studied.5 Comparatively, the selective bromochlorination of unsaturated hydrocarbons has recently experienced renewed attention as a result of recent interest in biologically active polyhalogenated natural products (Figure 1a).6,7 However, in addition to the challenge of site selectivity, the unified bromochlorination of (poly)unsaturated systems poses a multitude of stereo- and chemoselectivity challenges that must be circumvented to provide products of reasonable purity in synthetically useful yields (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a–c) Bromochlorination of alkenes.

Traditionally, the bromochlorination of alkenes and alkynes has predominantly relied upon the use of highly reactive halogen sources (e.g., dihalogens, organic hypohalites, and polyhalide-carrier reagents), thereby limiting substrate generality and requiring particular care during their preparation and handling.8 Alternatively, electrophilic brominating reagents, such as N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) or 1,3-dibromo-5,5-dimethylhydantoin (DBDMH), have been successfully applied in combination with a separate nucleophilic chloride source, thus enabling interhalogenation processes with improved selectivity and broader scope.9,10 However, the majority of these reactions are limited to the use of alkali metal chlorides, necessitating the use of super-stoichiometric quantities of a poorly soluble reagent (e.g., LiCl). Herein, we report a novel Lewis base-catalyzed bromochlorination of alkenes, alkynes, and dienes utilizing thionyl chloride and the first catalytic chemo-, regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective bromochlorination of chalcones.

We sought to identify a mild catalyst-controlled bromochlorination strategy that takes advantage of the inherent selectivity exacted by the nucleophilic interception of halonium intermediates (Figure 1c).11 Despite the number of thionyl chloride (SOCl2)-Lewis base adducts reported in the literature, there are currently no reports detailing the use of SOCl2 in combination with N-halosuccinimide reagents for the interhalogenation of π-systems.12 Thionyl chloride is easily handled and inexpensive (particularly when substoichiometric quantities are employed) and results in minimal byproduct formation. We surmised that a selective metal-free bromochlorination of alkenes and alkynes could be carried out via Lewis base activation of thionyl chloride, thereby ensuring the catalyst-controlled availability of soluble chloride in the presence of a bromonium source.13

Our initial studies confirmed that NBS and SOCl2 together remain largely inactive toward 1,5-cyclooctadiene (1a) in the absence of a catalyst (Table 1, entry 1). After an initial assessment of various Lewis base catalysts (see the Supporting Information), we settled on triphenylphosphine oxide (TPPO) due to its low cost, ease of handling, and superior yields. In the presence of only 1 mol % of TPPO, 73% yield of the desired vicinal anti-bromochlorinated product 2a was observed as a single diastereomer (entry 2). Notably, over-halogenation of 1a was not observed under these conditions and only 0.6 equiv of SOCl2 was necessary. Triphenylphosphine, which is reported to undergo rapid oxidation to TPPO in the presence of SOCl2, also proved to be a competent catalyst for this transformation (entry 3).14

Table 1. Reaction Optimizationa.

The effect of varying the halogenating reagents was also explored. Utilizing an excess of NBS proved detrimental to the yield of bromochloride 2a as over-halogenation was observed (entry 4). However, excess SOCl2 had little effect on the overall transformation (entry 5). When a proportional amount of DBDMH, NBP, or TBCO was surveyed in place of NBS, the reaction proceeded with varying yields (entries 6–8). While NBP provided product 2a in slightly higher yields, NBS was chosen as the optimal brominating reagent for this process due to the comparatively lower cost and wider availability of this reagent. Alternatively, when a slight excess of lithium chloride was used in place of SOCl2, only trace product was observed (entry 9).15 Oxalyl chloride, on the other hand, which is known to promote the formation of triphenylphosphine dichloride in the presence of TPPO, failed to promote the vicinal dihalogenation (entry 10).16 Finally, alternative solvents were found to be compatible with this method, including toluene (entry 11).

Having established optimal reaction conditions for the phosphine-promoted bromochlorination of alkenes, we surveyed the substrate scope and limitations. In the absence of a catalyst, styrenyl substrates generally underwent unselective halogenation, providing complex product mixtures. However, in the presence of 1 mol % triphenylphosphine or TPPO, the desired products were afforded in up to >20:1 regio- and diastereomeric ratios (Table 2b–f), with the site selectivity of chloride attack reinforced by the benzylic nature of the putative bromonium species. The observed high levels of selectivity demonstrate that the catalyst-controlled interhalogenation process is able to overcome the intrinsic high reactivity of this class of substrates. Notably, trans- and cis-styrenes 1b and 1c produced the expected diastereomeric products 2b and 2c in 91 and 98% 1H NMR yield, respectively, consistent with a stereospecific anti-addition of chloride ion on a bromiranium ion intermediate. Due to the instability and volatility of these and other vicinal dihalides synthesized in this study, isolated yields were generally lower than 1H NMR yields as determined through the use of an internal standard.

Table 2. Scope of the Catalytic Bromochlorinationa.

Unless specified otherwise, reactions were carried out under a N2 atmosphere using 0.5–1.0 mmol of the starting material in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (0.5 M) with 1 mol % of either OPPh3 or PPh3 (see the Supporting Information). Diastereomeric ratios (dr), regiomeric ratios (rr), and E/Z ratios were determined by analysis of the 1H NMR spectra of the purified products. Parenthetical values reflect the corresponding 1H NMR yields using mesitylene as an internal standard.

Reaction was run with 2 mol% catalyst.

Reaction was carried out with 1.2 equiv SOCl2.

Reaction was carried out on a 3 mmol scale.

Reaction was carried out with 1.2 equiv NBS.

Reaction was run with 10 mol % catalyst and 3 equiv SOCl2 over 18 h.

Reaction was run on a 5 mmol scale at 0–23 °C instead.

Reaction was carried out with 3 mol % catalyst instead.

As SOCl2 is commonly employed for the conversion of carboxylic acids to the corresponding acyl chlorides, carboxylic acid 1f required the use of 1.2 equiv of the chlorinating reagent to achieve 93% yield of dihalide 2f after aqueous acidic workup. Electron-deficient alkenes generally exhibited reduced rates of reaction or failed to undergo dihalogenation altogether (see the Supporting Information). However, chalcone 1g furnished benzylic chloride 2g in 92% yield as a single regio- and diastereomer.

Comparatively, unactivated monosubstituted alkenes suffered from poor site selectivity in the catalytic bromochlorination, unless inductively biased (2h–2m). Regardless, monosubstituted alkenes bearing ether, chloroformate, and cyanoacetate functionality were viable substrates under the optimal reaction conditions, favoring anti-Markovnikov delivery of chloride ion instead (2j–2l). Enyne 1m underwent dihalogenation to furnish propargylic chloride 2m, as expected. However, this reaction proved to be low yielding as a result of competitive dihalogenation of the adjacent alkyne, resulting in only 48% isolated yield of the desired product.

Disubstituted alkenes bearing allylic sulfonyl, halide, and carbonate functionality were also compatible with the dihalogenation protocol, providing halides 2n–2p with good diastereoselectivity. Analogous to cis-alkenes 1c and 1d, acyclic cis-1o produced polyhalide 2o in reduced yield. Alkene 1q, possessing 1,1-disubstitution, and trisubstituted alkenes generally underwent regioselective halogenation to the corresponding tertiary chloride products 2q–2u. Enal 1v, however, exhibited a switch in selectivity, yielding tertiary bromide 2v as a result of the inductive bias afforded by the adjacent aldehyde substituent. Of note, substrates bearing Lewis basic functionality did not require the addition of an exogenous Lewis base catalyst.17

As the non-directed bromochlorination of conjugated π-systems remains largely unexplored, with only a handful of examples reported using poly-halide carrier reagents or bromochloride directly, we were interested in measuring the inherent selectivity of this newly developed halogenation protocol.18,10a The dihalogenation of isoprene, for example, can afford up to six possible constitutional isomers. Under the optimized conditions, vicinal bromochloride 2w was the major product alongside minor amounts of 2w′ and a separate fraction containing 2w″, with a combined yield of 74%. 1,4-Disubstituted dienamide 1x underwent bromochlorination with pronounced reactivity at the distal alkene, affording 2x in 60% yield.

We were also interested to see whether this Lewis base-catalyzed interhalogenation strategy would be applicable to alkyne dihalogenation.19 This strategy would provide efficient access to stereo-defined vicinal, vinylic bromochlorides amenable to further stereospecific diversification. Symmetrical alkyne 3a yielded trans-4a in 87% yield. Terminal alkynes 3b and 3c also underwent trans-selective and regioselective dihalogenation to the corresponding terminal vinylic bromides (4b and 4c).

Finally, the scalability of the catalytic bromochlorination was examined. Both alkene 1a and alkyne 3a were subjected to the catalytic bromochlorination protocol, each on a 20 mmol scale. Not only did these reactions display similar efficiency irrespective of the 40-fold increase in scale, but the resulting products were also isolated in improved yields of 81 and 95%, respectively. Moreover, product 4a could be isolated in high purity without the need for chromatographic purification.

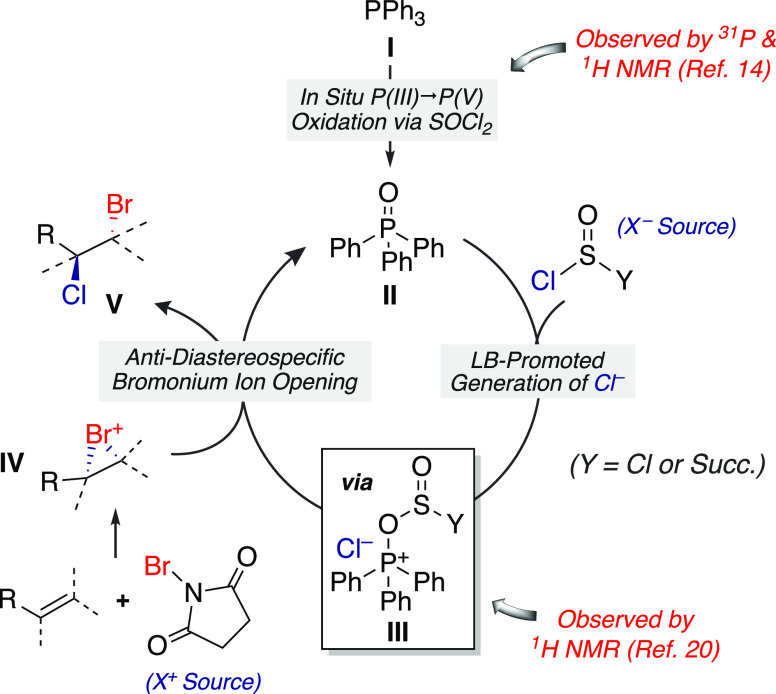

Based on the perceived trends in product selectivity and additional experimental mechanistic studies (see the Supporting Information), we propose the following mechanistic hypothesis (Figure 2). Both triphenylphosphine (I) and TPPO (II) are competent catalysts for this reaction. The rapid oxidation of I to II by action of thionyl chloride is well known and was observed via in situ1H and 31P NMR.14 Phosphine oxide II may then act as a Lewis base toward thionyl chloride, with nucleophilic addition to the sulfur atom resulting in ionization (III).20 Subsequent reaction between salt III and putative bromiranium complex IV via anti-selective nucleophilic trapping yields bromochloride product V in a diastereoselective manner.21 The positional selectivity exhibited by this reaction suggests that chloride attack takes place at the position where the developing electropositive character is better stabilized.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism for the Lewis base-catalyzed bromochlorination.

Considering this mechanistic hypothesis, one could envision alternative dihalogenation reactions upon substitution of one or both halogenating reagents (Table 3). When commercial grade SOBr2 was used in place of SOCl2, the catalytic dibromination of alkenes and alkynes was accomplished, with up to 84% yield (2y, 2z, and 4d). The complementary dichlorination reaction was also feasible; however, no reaction was observed when NBS was exchanged for NCS in the presence of SOCl2. Thus, we opted to survey more potent chlorenium sources.22 Under the optimized reaction conditions, using substoichiometric quantities of DCDMH or TCCA instead, the dichlorination of alkenes was observed in synthetically useful yields (2aa–2ac).23 Finally, highly selective chloroiodination and bromoiodination reactions were carried out using NIS in combination with either SOCl2 or SOBr2 with up to 96% yield (2ad–2af and 4f–4g). Of note, all of these reactions proceeded with comparably high regio-, diastereo-, and E/Z selectivity, demonstrating the flexibility and precision of this catalytic protocol.

Table 3. Alternative Dihalogenation Reactionsa.

Unless specified otherwise, reactions were carried out under a N2 atmosphere using 0.5 mmol of the starting material in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (0.5 M). Diastereomeric ratios (dr), regiomeric ratios (rr), and E/Z ratios were determined by analysis of the 1H NMR spectra of the purified products.

Reaction was carried out using 0.52 equiv of DCDMH instead.

Reaction was carried out using 0.34 equiv of TCCA instead.

Naturally, we were curious to see whether this strategy for bromochlorination could be rendered enantioselective when employing a chiral Lewis base.13 Strategies for the catalytic enantioselective alkene bromochlorination remain exceedingly rare, with two pioneering strategies reported to date, both of which require the use of tethered protonated directing groups and (alkali) metal chloride reagents (Figure 3a).5b,5d,10 We hypothesized that this alternative method of chloride generation might offer a new strategy for enantioselective bromochlorination, providing access to other classes of enantioenriched vicinal bromochlorides via Lewis base-controlled chloride delivery.24 For example, the catalytic enantioselective bromochlorination of enones and enoates remains unreported in the literature.

Figure 3.

(a, b) Catalytic enantioselective bromochlorination of alkenes and inspiration for an alternative strategy.

Finding no success with chiral phosphine catalysts (see the Supporting Information), we turned our attention to other classes of chiral Lewis bases. Inspired by prior work on enantioselective transfer sulfinylation chemistry, wherein sulfinyl chlorides were proposed to undergo dynamic kinetic resolution via chiral sulfinylammonium salts, we opted to explore cinchona alkaloids as Lewis base catalysts for enantioselective bromochlorination (Figure 3b).25,26 As the key step of this interhalogenation hinges on the activation of thionyl chloride, we postulated that a chiral chloride salt, analogous to those proposed by Toru and Ellman may participate in the enantiodetermining step, namely, chloride addition to a configurationally labile bromiranium intermediate.25a,25b,27−29

Preliminary findings indicated that commercially available alkaloid-derived (DHQD)2PHAL can indeed promote a regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective bromochlorination of chalcone 1g (Table 4). Utilizing just 1 mol % of this Lewis base catalyst, 2g was obtained in up to 67% yield with a 92:08 enantiomeric ratio (er). However, increased catalyst loading or decreased reaction temperature failed to improve the enantioselectivity of this process (see the Supporting Information). Of note, this reaction proceeded in a highly regio- and diastereoselective fashion, delivering predominantly one of eight possible isomers. The relative and absolute stereochemistry of 2g was confirmed by X-ray crystallography.

Table 4. Catalytic Enantioselective Bromochlorinationa.

Unless specified otherwise, reactions were carried out at −50 °C under a N2 atmosphere using 0.23–0.5 mmol of the starting material in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (0.5 M) with 1 mol % of (DHQD)2PHAL. Diastereomeric ratios (dr) and regiomeric ratios (rr) were determined by analysis of the 1H NMR spectra of the purified products. Enantiomeric ratios (er) were determined by HLPC analysis.

Reaction was carried out using 3 mol % of the catalyst.

Reaction was carried out with 1.44 equiv NBS and 2.4 equiv SOCl2 instead.

Reaction was carried out in anhydrous CHCl3 instead.

Reaction was carried out using 2 mol % catalyst instead.

Reaction was carried out at 23 °C

Alternative enones were surveyed to delineate trends in reactivity and selectivity.30 Enoate 1ag exhibited poor reactivity and stereoselectivity in comparison to analogous chalcone substrates, necessitating increased catalyst and reagent loadings to reach full conversion. Dienone 1ah, however, reacted smoothly to preference the formation of dihalide 2ah with 77% yield and 83:17 er. Chalcones 1ai and 1aj exhibited similar levels of stereoselectivity to 1g, yielding bromochlorides 2ai and 2aj in high yields and selectivity. Although electron withdrawing substituents on 1ak–1am hampered the reactivity of these substrates, we found that this effect was counterbalanced by the enhanced stereoselectivity of these processes, even at room temperature. Using only 1 mol % of the catalyst, chlorobromide 2ak was afforded in 90:10 er, while 3 mol % of the catalyst was necessary to achieve 76% yield of 2al in 90:10 er. These results represent a significant departure from existing organocatalytic methods for enantioselective dihalogenation, which customarily require extremely low reaction temperatures and/or catalyst loadings of 10–30 mol % to achieve similar levels of enantioselectivity.31

In conclusion, we have developed a new strategy for the highly selective bromochlorination of alkenes and alkynes. The key feature of this method is the utilization of thionyl chloride, which serves as a latent chloride source until acted upon by a Lewis base catalyst or Lewis basic substituent. We have demonstrated the utility of this catalytic, regio-, and diastereoselective interhalogenation utilizing as little as 1 mol % of triphenylphosphine or TPPO as an inexpensive catalyst. The extension of this method toward various other dihalogenation reactions was also accomplished, necessitating simply a change in the halogenating reagents employed. Moreover, this strategy was adapted to demonstrate a novel method for the catalytic enantioselective bromochlorination of enones, utilizing just 1–3 mol % of a commercially available organocatalyst, (DHQD)2PHAL. This study represents a major advance in the area of catalytic asymmetric interhalogenation that is distinct from prior approaches and does not require the pre-installation of a directing group. The mechanism and mode of stereoinduction for this method remain the subject of continued investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. X. Xu (the Center for NMR Spectroscopy, Baylor University, Texas) for technical support, A. Bernal-Tent for supplying substrate 2m, and J. Tidwell and Prof. K. Klausmeyer for assistance with X-ray crystallography. We thank Profs. U. Tambar and D. Romo for insightful discussions regarding this work and Profs. D. Romo and J.L. Wood for access to chemicals and equipment.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c04588.

General procedural information, additional optimization data, mechanistic studies, characterization data and X-ray crystallographic data, and NMR spectra of characterized products (PDF)

The authors are grateful for financial support from the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT, RR200039) and the Welch Foundation (AA-2077-20210327) and for startup funds provided by Baylor University.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For selected references on the utility of halogen-containing molecules, see; a Gribble G. W. Natural Organohalogens: A New Frontier for Medicinal Agents?. J. Chem. Educ. 2004, 81, 1441. 10.1021/ed081p1441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Jeschke P. The Unique Role of Halogen Substituents in the Design of Modern Agrochemicals. Pest Manage. Sci. 2010, 66, 10–27. 10.1002/ps.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Smith B. R.; Eastman C. M.; Njardarson J. T. Beyond C, H, O, and N! Analysis of the Elemental Composition of U.S. FDA Approved Drug Architectures. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9764–9773. 10.1021/jm501105n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gál B.; Bucher C.; Burns N. Z. Chiral Alkyl Halides: Underexplored Motifs in Medicine. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 206. 10.3390/md14110206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Jeschke P. Latest Generation of Halogen-Containing Pesticides. Pest Manage. Sci. 2017, 73, 1053–1066. 10.1002/ps.4540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Lin R.; Amrute A. P.; Pérez-Ramírez J. Halogen-Mediated Conversion of Hydrocarbons to Commodities. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 4182–4247. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Pak B. S.; Supantanapong N.; Vanderwal C. D. The Recurring Roles of Chlorine in Synthetic and Biological Studies of the Lissoclimides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1131–1142. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected references on halogenated natural products, see; a Gribble G. W. Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998, 31, 141–152. 10.1021/ar9701777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Gribble G. W. A Recent Survey of Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 396–405. 10.1071/EN15002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gribble G. W. Newly Discovered Naturally Occurring Organohalogens. ARKIVOC 2019, 2018, 372–410. [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews on reactions of organohalides, see; (a) Beller M.; Zapf A.; Riermeier T. H.. Palladium-Catalyzed Olefinations of Aryl Halides (Heck Reaction) and Related Transformations. In Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis, Beller M., Bolm C. Eds.; Wiley Online Books, WILEY-VCH, 2004; pp. 271–305. [Google Scholar]; b Rudolph A.; Lautens M. Secondary Alkyl Halides in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 2656–2670. 10.1002/anie.200803611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kambe N.; Iwasaki T.; Terao J. Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Alkyl Halides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 4937–4947. 10.1039/c1cs15129k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ye S.; Xiang T.; Li X.; Wu J. Metal-Catalyzed Radical-Type Transformation of Unactivated Alkyl Halides with C–C Bond Formation under Photoinduced Conditions. Org. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2183–2199. 10.1039/C9QO00272C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Cheng L.-J.; Mankad N. P. C–C and C–X Coupling Reactions of Unactivated Alkyl Electrophiles Using Copper Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8036–8064. 10.1039/D0CS00316F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Nelson J. D. Aliphatic Nucleophilic Substitution. Pract. Synth. Org. Chem. 2020, 1–63. 10.1002/9781119448914.ch1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Ripin D. H. B.; Brown A. R. Synthesis of “Nucleophilic” Organometallic Reagents. Pract. Synth. Org. Chem. 2020, 591–620. 10.1002/9781119448914.ch12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Juliá F.; Constantin T.; Leonori D. Applications of Halogen-Atom Transfer (XAT) for the Generation of Carbon Radicals in Synthetic Photochemistry and Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 2292–2352. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Bolton R.Chapter 1 Electrophilic Additions to Unsaturated Systems. In Comprehensive Chemical Kinetics; Bamford C. H., Tipper C. F. H. Eds.; Vol. 9; Elsevier, 1973; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schmid G. H.; Garratt D. G.. Electrophilic Additions to Carbon–Carbon Double Bonds. In Double-Bonded Functional Groups (1977); S P. Ed.; Patai’s Chemistry of Functional Groups: Vol. 2; 1977; pp. 725–912. [Google Scholar]; c Castellanos A.; Fletcher S. P. Current Methods for Asymmetric Halogenation of Olefins. Chem. – Eur. J. 2011, 17, 5766–5776. 10.1002/chem.201100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Denmark S. E.; Kuester W. E.; Burk M. T. Catalytic, Asymmetric Halofunctionalization of Alkenes—a Critical Perspective. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10938–10953. 10.1002/anie.201204347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Hennecke U. New Catalytic Approaches Towards the Enantioselective Halogenation of Alkenes. Chem. – Asian J. 2012, 7, 456–465. 10.1002/asia.201100856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Cheng Y. A.; Yu W. Z.; Yeung Y.-Y. Recent Advances in Asymmetric Intra- and Intermolecular Halofunctionalizations of Alkenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 2333–2343. 10.1039/C3OB42335B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hennecke U.; Rösner C.; Wald T.; Robert T.; Oestreich, M. 7.21 Addition Reactions with Formation of Carbonhalogen Bonds. In Comprehensive Organic Synthesis (Second Edition), Knochel P. Ed.; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 638–691. [Google Scholar]

- For selected reviews, see; a Nilewski C.; Carreira E. M. Recent Advances in the Total Synthesis of Chlorosulfolipids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 1685–1698. 10.1002/ejoc.201101525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Cresswell A. J.; Eey S. T. C.; Denmark S. E. Catalytic, Stereoselective Dihalogenation of Alkenes: Challenges and Opportunities. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15642–15682. 10.1002/anie.201507152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Saikia I.; Borah A. J.; Phukan P. Use of Bromine and Bromo-Organic Compounds in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 6837–7042. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Bock J.; Guria S.; Wedek V.; Hennecke U. Enantioselective Dihalogenation of Alkenes. Chem. – Eur. J. 2021, 27, 4517–4530. 10.1002/chem.202003176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chung W.-j.; Vanderwal C. D. Stereoselective Halogenation in Natural Product Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4396–4434. 10.1002/anie.201506388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Landry M. L.; Burns N. Z. Catalytic Enantioselective Dihalogenation in Total Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1260–1271. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For references pertaining to the selected examples of vicinal bromochlorides included in Figure 1a, see; a Faulkner D. J. 3β-Bromo-8-Epicaparrapi Oxide, the Major Metabolite of Laurencia Obtusa. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 1992–1993. 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)88870-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Suzuki M.; Matsuo Y.; Takeda S.; Suzuki T. Intricatetraol, a Halogenated Triterpene Alcohol from the Red Alga Laurencia Intricata. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 651–656. 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85467-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Schlama T.; Baati R.; Gouverneur V.; Valleix A.; Falck J. R.; Mioskowski C. Total Synthesis of (±)-Halomon by a Johnson–Claisen Rearrangement. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2085–2087. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sotokawa T.; Noda T.; Pi S.; Hirama M. A Three-Step Synthesis of Halomon. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3430–3432. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Morimoto Y.; Okita T.; Takaishi M.; Tanaka T. Total Synthesis and Determination of the Absolute Configuration of (+)-Intricatetraol. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1132–1135. 10.1002/anie.200603806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Bucher C.; Deans R. M.; Burns N. Z. Highly Selective Synthesis of Halomon, Plocamenone, and Isoplocamenone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 12784–12787. 10.1021/jacs.5b08398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Lorente A.; Gil A.; Fernández R.; Cuevas C.; Albericio F.; Álvarez M. Phormidolides B and C, Cytotoxic Agents from the Sea: Enantioselective Synthesis of the Macrocyclic Core. Chem. – Eur. J. 2015, 21, 150–156. 10.1002/chem.201404341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Burckle A. J.; Gál B.; Seidl F. J.; Vasilev V. H.; Burns N. Z. Enantiospecific Solvolytic Functionalization of Bromochlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13562–13569. 10.1021/jacs.7b07792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Gil A.; Giarrusso M.; Lamariano-Merketegi J.; Lorente A.; Albericio F.; Álvarez M. Toward the Synthesis of Phormidolides. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2351–2362. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples, see; a Buckles R. E.; Long J. W. The Addition of Bromine Chloride to Carbon—Carbon Double Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 998–1000. 10.1021/ja01147a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Negoro T.; Ikeda Y. Bromochlorination of Alkenes with Dichlorobromate (1−) Ion. Iv. Regiochemistry of Bromochlorinations of Alkenes with Molecular Bromine Chloride and Dichlorobromate (1−) Ion. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1986, 59, 2547–2551. 10.1246/bcsj.59.2547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Chiappe C.; Capraro D.; Conte V.; Pieraccini D. Stereoselective Halogenations of Alkenes and Alkynes in Ionic Liquids. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1061–1063. 10.1021/ol015631s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Chiappe C.; Del Moro F.; Raugi M. Equilibria and Uv-Spectral Characteristics of BrCl, BrCl2–, and Br2Cl– Species in 1,2-Dichloroethane – Stereoselectivity and Kinetics of the Electrophilic Addition of These Species to Alkenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 2001, 3501–3510. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Cristiano R.; Ma K.; Pottanat G.; Weiss R. G. Tetraalkylphosphonium Trihalides. Room Temperature Ionic Liquids as Halogenation Reagents. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 9027–9033. 10.1021/jo901735h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Schmidt B.; Ponath S.; Hannemann J.; Voßnacker P.; Sonnenberg K.; Christmann M.; Riedel S. In Situ Synthesis and Applications for Polyinterhalides Based on BrCl. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 15183–15189. 10.1002/chem.202001267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a recent example, seeRubio-Presa R.; García-Pedrero O.; López-Matanza P.; Barrio P.; Rodríguez F. Dihalogenation of Alkenes Using Combinations of N-Halosuccinimides and Alkali Metal Halides. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 4762–4766. 10.1002/ejoc.202100811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of catalytic enantioselective bromochlorination of alkenes, see; a Hu D. X.; Seidl F. J.; Bucher C.; Burns N. Z. Catalytic Chemo-, Regio-, and Enantioselective Bromochlorination of Allylic Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3795–3798. 10.1021/jacs.5b01384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huang W.-S.; Chen L.; Zheng Z.-J.; Yang K.-F.; Xu Z.; Cui Y.-M.; Xu L.-W. Catalytic Asymmetric Bromochlorination of Aromatic Allylic Alcohols Promoted by Multifunctional Schiff Base Ligands. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 7927–7932. 10.1039/C6OB01306F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Seidl F. J.; Burns N. Z. Selective Bromochlorination of a Homoallylic Alcohol for the Total Synthesis of (−)-Anverene. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1361–1365. 10.3762/bjoc.12.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Soltanzadeh B.; Jaganathan A.; Yi Y.; Yi H.; Staples R. J.; Borhan B. Highly Regio- and Enantioselective Vicinal Dihalogenation of Allyl Amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 2132–2135. 10.1021/jacs.6b09203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wu S.; Xiang S.-H.; Li S.; Ding W.-Y.; Zhang L.; Jiang P.-Y.; Zhou Z.-A.; Tan B. Urea Group-Directed Organocatalytic Asymmetric Versatile Dihalogenation of Alkenes and Alkynes. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 692–702. 10.1038/s41929-021-00660-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For discussions regarding the reactivity and stability of bromonium ions, see; a Roberts I.; Kimball G. E. The Halogenation of Ethylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937, 59, 947–948. 10.1021/ja01284a507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Brown R. S.; Nagorski R. W.; Bennet A. J.; McClung R. E. D.; Aarts G. H. M.; Klobukowski M.; McDonald R.; Santarsiero B. D. Stable Bromonium and Iodonium Ions of the Hindered Olefins Adamantylideneadamantane and Bicyclo[3.3.1]Nonylidenebicyclo [3.3.1]Nonane. X-Ray Structure, Transfer of Positive Halogens to Acceptor Olefins, and Ab Initio Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 2448–2456. 10.1021/ja00085a027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Neverov A. A.; Brown R. S. Br+ and I+ Transfer from the Halonium Ions of Adamantylideneadamantane to Acceptor Olefins. Halocyclization of 1, ω-Alkenols and Alkenoic Acids Proceeds Via Reversibly Formed Intermediates. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 962–968. 10.1021/jo951703f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Brown R. S. Investigation of the Early Steps in Electrophilic Bromination through the Study of the Reaction with Sterically Encumbered Olefins. Acc. Chem. Res. 1997, 30, 131–137. 10.1021/ar960088e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Lenoir D.; Chiappe C. What Is the Nature of the First-Formed Intermediates in the Electrophilic Halogenation of Alkenes, Alkynes, and Allenes?. Chem. – Eur. J. 2003, 9, 1036–1044. 10.1002/chem.200390097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Denmark S. E.; Burk M. T.; Hoover A. J. On the Absolute Configurational Stability of Bromonium and Chloronium Ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1232–1233. 10.1021/ja909965h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a El-Sakka I. A.; Hassan N. A. Synthetic Uses of Thionyl Chloride. J. Sulfur Chem. 2005, 26, 33–97. 10.1080/17415990500031187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wirth D. D.; Vikas S.; Jagadish P. Thionyl Chloride. e-EROS Encycl. Reagents Org. Synth. 2017, 1–6. 10.1002/047084289X.rt099.pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denmark S. E.; Beutner G. L. Lewis Base Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 1560–1638. 10.1002/anie.200604943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H.-F.; Kuhn A.; Kuhn N.; Laufer S.; Ströbele M. Zur Reaktion Von Triphenylphosphan Mit Thionylchlorid. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2012, 638, 1784–1786. 10.1002/zaac.201200287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Based on our observations, the lack of appreciable reactivity with lithium chloride may be due to the insolubility of this reagent in the selected solvent.

- a Denton R. M.; An J.; Adeniran B. Phosphine Oxide-Catalysed Chlorination Reactions of Alcohols under Appel Conditions. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 3025–3027. 10.1039/c002825h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Denton R. M.; An J.; Adeniran B.; Blake A. J.; Lewis W.; Poulton A. M. Catalytic Phosphorus(V)-Mediated Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions: Development of a Catalytic Appel Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6749–6767. 10.1021/jo201085r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Jia M.; Jiang L.; Niu F.; Zhang Y.; Sun X. A Novel and Highly Efficient Esterification Process Using Triphenylphosphine Oxide with Oxalyl Chloride. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171988. 10.1098/rsos.171988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In the absence of a catalyst, substrates 1t and 1u yielded bromochlorides 2t and 2u in 47 and 67% 1H NMR yield, respectively (see the Supporting Information)

- a Heasley G. E.; Bundy J. M.; Heasley V. L.; Arnold S.; Gipe A.; McKee D.; Orr R.; Rodgers S. L.; Shellhamer D. F. Electrophilic Additions to Dienes and the 1-Phenylpropenes with Pyridine-Halogen Complexes and Tribromides. Effects on Stereochemistry and Product Ratios. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 2793–2799. 10.1021/jo00408a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Negoro T.; Ikeda Y. Bromochlorination of Conjugated Dienes with Dichlorobromate(1-) Ion. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1985, 58, 3655–3656. 10.1246/bcsj.58.3655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For recent examples regarding alkyne bromochlorination, see; a Zeng X.; Liu S.; Yang Y.; Yang Y.; Hammond G. B.; Xu B. Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of 1,2-Dihaloalkenes Using in-Situ-Generated Icl, Ibr, Brcl, I2, and Br2. Chem 2020, 6, 1018–1031. 10.1016/j.chempr.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kong Y.; Cao T.; Zhu S. Tempo-Regulated Regio- and Stereoselective Cross-Dihalogenation with Dual Electrophilic X+ Reagents. Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 3004–3010. 10.1002/cjoc.202100472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y.; Kim K. T.; Jeon H. B. Deoxygenation of Sulfoxides to Sulfides with Thionyl Chloride and Triphenylphosphine: Competition with the Pummerer Reaction. J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 6328–6331. 10.1021/jo4008157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an example of the use of SOCl2 for the conversion of bromohydrins to vicinal bromochlorides via bromonium intermediates, seeBraddock D. C.; Hermitage S. A.; Kwok L.; Pouwer R.; Redmond J. M.; White A. J. P. The Generation and Trapping of Enantiopure Bromonium Ions. Chem. Commun. 2009, 1082–1084. 10.1039/b816914d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashtekar K. D.; Marzijarani N. S.; Jaganathan A.; Holmes D.; Jackson J. E.; Borhan B. A New Tool To Guide Halofunctionalization Reactions: The Halenium Affinity (HalA) Scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13355–13362. 10.1021/ja506889c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- When either DCDMH or TCCA was utilized in combination with SOBr2, we failed to observe the expected bromochlorinated products with opposite positional selectivity to those of Table 2.

- For analogous strategies utilizing silicon chlorides, see; a Andrews G. C.; Crawford T. C.; Contillo L. G. Nucleophilic Catalysis in the Insertion of Silicon Halides into Oxiranes: A Synthesis of O-Protected Vicinal Halohydrins. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 3803–3806. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)91312-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Denmark S. E.; Barsanti P. A.; Wong K.-T.; Stavenger R. A. Enantioselective Ring Opening of Epoxides with Silicon Tetrachloride in the Presence of a Chiral Lewis Base. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2428–2429. 10.1021/jo9801420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tao B.; Lo M. M. C.; Fu G. C. Planar-Chiral Pyridine N-Oxides, a New Family of Asymmetric Catalysts: Exploiting an η5-C5Ar5 Ligand to Achieve High Enantioselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 353–354. 10.1021/ja003573k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Nakajima M.; Saito M.; Uemura M.; Hashimoto S. Enantioselective Ring Opening of Meso-Epoxides with Tetrachlorosilane Catalyzed by Chiral Bipyridine N,N′-Dioxide Derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 8827–8829. 10.1016/S0040-4039(02)02229-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Denmark S. E.; Barsanti P. A.; Beutner G. L.; Wilson T. W. Enantioselective Ring Opening of Epoxides with Silicon Tetrachloride in the Presence of a Chiral Lewis Base: Mechanism Studies. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349, 567–582. 10.1002/adsc.200600551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For examples of catalytic enantioselective dichlorination of alkenes using cinchona alkaloid-based catalysts, see; a Juliá S.; Ginebreda A. Asymmetric Induction by Phase-Transfer Catalysis Using Chiral Catalysts. Synthesis of 1,2-Dichloroalkanes and Acetylcyanohydrins. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 2171–2174. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)86293-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Nicolaou K. C.; Simmons N. L.; Ying Y.; Heretsch P. M.; Chen J. S. Enantioselective Dichlorination of Allylic Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 8134–8137. 10.1021/ja202555m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wedek V.; Van Lommel R.; Daniliuc C. G.; De Proft F.; Hennecke U. Organocatalytic, Enantioselective Dichlorination of Unfunctionalized Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9239–9243. 10.1002/anie.201901777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples and discussion on enantioselective transfer sulfinylation, see; a Shibata N.; Matsunaga M.; Nakagawa M.; Fukuzumi T.; Nakamura S.; Toru T. Cinchona Alkaloid/Sulfinyl Chloride Combinations: Enantioselective Sulfinylating Agents of Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1374–1375. 10.1021/ja0430189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peltier H. M.; Evans J. W.; Ellman J. A. Catalytic Enantioselective Sulfinyl Transfer Using Cinchona Alkaloid Catalysts. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1733–1736. 10.1021/ol050275p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cheong P. H.-Y.; Legault C. Y.; Um J. M.; Çelebi-Ölçüm N.; Houk K. N. Quantum Mechanical Investigations of Organocatalysis: Mechanisms, Reactivities, and Selectivities. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5042–5137. 10.1021/cr100212h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wojaczyńska E.; Wojaczyński J. Modern Stereoselective Synthesis of Chiral Sulfinyl Compounds. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 4578–4611. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brak K.; Jacobsen E. N. Asymmetric Ion-Pairing Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 534–561. 10.1002/anie.201205449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For 1H NMR comparison of (DHQD)2PHAL with and without SOCl2, see the Supporting Information.

- It is also possible that the chiral catalyst is playing a dual role in this reaction by associating with both NBS and SOCl2 concurrently. For discussion regarding an alternative associative complex between NBS and (DHQD)2PHAL, see; a Wilking M.; Mück-Lichtenfeld C.; Daniliuc C. G.; Hennecke U. Enantioselective, Desymmetrizing Bromolactonization of Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8133–8136. 10.1021/ja402910d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yousefi R.; Sarkar A.; Ashtekar K. D.; Whitehead D. C.; Kakeshpour T.; Holmes D.; Reed P.; Jackson J. E.; Borhan B. Mechanistic Insights into the Origin of Stereoselectivity in an Asymmetric Chlorolactonization Catalyzed by (DHQD)2PHAL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 7179–7189. 10.1021/jacs.0c01830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For a listing of substrates that failed to undergo bromochlorination with appreciable enantioiselectivity, see the Supporting Information.

- For additional examples regarding catalytic enantioiselective dihalogenations of alkenes, see; a Hu D. X.; Shibuya G. M.; Burns N. Z. Catalytic Enantioselective Dibromination of Allylic Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12960–12963. 10.1021/ja4083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Landry M. L.; Hu D. X.; McKenna G. M.; Burns N. Z. Catalytic Enantioselective Dihalogenation and the Selective Synthesis of (−)-Deschloromytilipin a and (−)-Danicalipin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5150–5158. 10.1021/jacs.6b01643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Scheidt F.; Schäfer M.; Sarie J. C.; Daniliuc C. G.; Molloy J. J.; Gilmour R. Enantioselective, Catalytic Vicinal Difluorination of Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16431–16435. 10.1002/anie.201810328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gilbert B. B.; Eey S. T. C.; Ryabchuk P.; Garry O.; Denmark S. E. Organoselenium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Syn-Dichlorination of Unbiased Alkenes. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 4086–4098. 10.1016/j.tet.2019.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Haj M. K.; Banik S. M.; Jacobsen E. N. Catalytic, Enantioselective 1,2-Difluorination of Cinnamamides. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 4919–4923. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.