Abstract

State-of-the-art liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS)-based proteomic technologies, using microliter amounts of patient plasma, can detect and quantify several hundred plasma proteins in a high throughput fashion, allowing for the discovery of clinically relevant protein biomarkers and insights into the underlying pathobiological processes. Using such an in-house developed high throughput plasma proteomics allowed us to identify and quantify > 400 plasmas proteins in 15 minutes per samples, i.e., a throughput of 100 samples/day. We demonstrated the clinical applicability of our method in this pilot study by mapping the plasma proteomes from patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or herpes virus, both groups with involvement of the central nervous system (CNS). We found significant disease-specific differences in the plasma proteomes. The most notable difference was a decrease in the levels of several coagulation-associated proteins in HIV vs. herpes virus, amongst other dysregulated biological pathways providing insight into the differential pathophysiology of HIV compared to herpes virus infection. In a subsequent analysis, we found several plasma proteins associated with immunity and metabolism to differentiate patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) compared to cognitively normal people with HIV (PWH), suggesting the presence of plasma-based biomarkers to distinguishing HAND from cognitively normal PWH. Overall, our high-throughput plasma proteomics pipeline enables identification of distinct proteomic signatures of HIV and herpes virus, which may help illuminate divergent pathophysiology behind virus-associated neurological disorders.

Keywords: Mass spectrometry, Plasma Proteomics, HIV, HAND, herpes virus, Biomarkers, CNS

Introduction

Recent technological advances in the field of LC/MS-based proteomics have enhanced proteomics’ clinical applicability. The ability to process easily and rapidly 10s to 100s of patient samples in a high throughput manner has become standard in proteomic biomarker discovery workflows (Berger, Ahmed et al. 2015, Bennike and Steen 2017). The proteomes of a wide range of different human body fluid specimens have been successfully characterized using LC/MS-based proteomics (Bennike, Barnaby et al. 2015, Muntel, Xuan et al. 2015, Bennike, Bellin et al. 2018, Lee, Shannon et al. 2019). While characterization of neurological diseases has historically relied on access to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), blood biomarker discovery for such conditions has become more a more attractive pursuit given the relative ease with which blood samples can be collected (Zetterberg and Burnham 2019). The easy availability and accessibility of blood makes it the preferred body fluid for the discovery of protein biomarkers and for studying the pathophysiological mechanisms of disease.

Despite the advancement and increased potency of combined antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), an increased prevalence of non-AIDS-associated comorbidities persist, including neurocognitive deficits, disturbed coagulation, and immune perturbation (Graham, Mwilu et al. 2013, Funderburg and Lederman 2014, Montoya, Iudicello et al. 2017). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), consisting of asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI), mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) and HIV-associated dementia (HAD), affect 20–50% of HIV-positive individuals (Eggers, Arendt et al. 2017). Despite viral suppression, the underlying neuropathophysiology of HAND is not fully understood and remains a clinical diagnosis without diagnostic biomarkers (Lu, Surkan et al. 2019, Rubin and Maki 2019).

Our in-house developed, robust, high throughput plasma proteomics pipeline involves exploiting the speed and resolution of a trapped ion mobility/time-of-flight mass spectrometer (timsTOF Pro) with the newly developed data independent acquisition – parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation (dia-PASEF) (Meier, Brunner et al. 2020) method to identify and quantify over 400 plasmas proteins in 15 minutes per samples, i.e., a throughput of 100 samples/day. Newer hardware has allowed us to double this throughput in the meanwhile. This quick turnaround surpasses traditional LC/MS-based proteomics methods that alone require days of MS acquisition time.

Our overarching aim of this pilot study was to demonstrate feasibility of our unique method to investigate the plasma proteome using clinical blood samples from patients infected with HIV, herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, or herpes zoster virus (with the latter three collectively referred to as ‘herpes virus’), with concern for central nervous system (CNS) involvement. Here, we demonstrate the applicability of our high throughput proteomics pipeline to investigate novel blood biomarkers and biological processes which provide insight into the pathophysiology of HIV and herpes infection, and may represent novel therapeutic targets.

Materials and Methods

Patient Samples

Patient samples were obtained as part of a prospective cohort study enrolling adults who present to Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) with neurological symptoms. Only PWH on ART were included with ages ≥18 years with at least one of the following criteria were eligible for enrollment: 1) altered level of consciousness; 2) fever; 3) seizure; 4) focal neurological finding; 5) electroencephalographic or neuroimaging findings consistent with encephalitis or meningitis; 6) refractory headaches, 7) cognitive symptoms or 8) clinical concern for a CNS infection. Additionally, enrollment was only offered to patients who had undergone, or were planned to undergo, lumbar puncture. This study was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board under protocol 2015P001388.

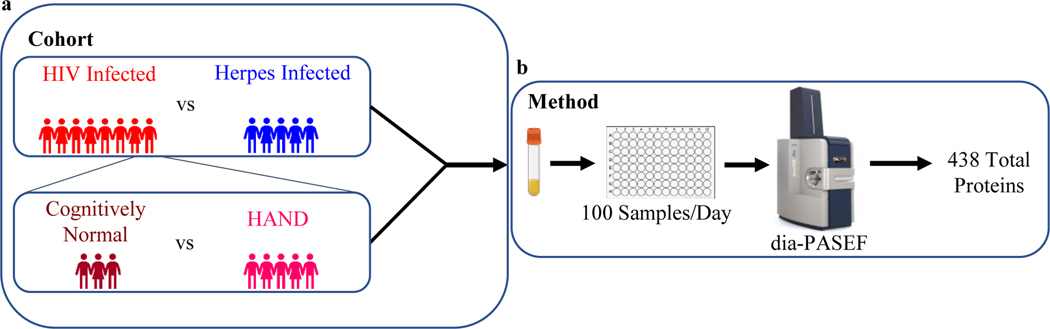

For our study, we mapped the proteomes of plasma samples collected from virally suppressed PWH, or CNS infections due to herpes simplex 1 (HSV1), herpes simplex 2 (HSV2), or varicella zoster virus (VZV), which we combined into the herpes infection group. PWH were classified as MND or HAD based on clinical neuropsychological profiles obtained within the prior 2 years and the Frascati criteria (Antinori, Arendt et al. 2007) (Fig. 1a, Table 1). Three PWH were presumed cognitively normal based on review of clinical providers’ records documenting a mental status examination; these individuals did not have clinical neuropsychological testing prior to lumbar puncture. The reasons for lumbar puncture and past medical history are documented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the plasma proteomics platform including LC MS/MS acquisition and data analysis which was used to process as little as 50 μL of plasma from patients with HIV, herpes, with or HAND. (a) Cohort schematic of comparing 5 herpes viruses infected patients vs 8 HIV infected patients. Second cohort schematic of sub cluster of HIV infected patients comparing 5 HAND to 3 cognitively normal patients. (b) Method schematic of our in house developed high throughput plasma proteomics pipeline which can identify a total of 438 plasma proteins in a single day using dia-PASEF

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cohort

| Pathology | Age | Sex | Race | PMH | Plasma HIV Viral Load | Reason for Lumbar Puncture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitively Normal* | 51 | M | white | Untreated Hepatitis C, Cluster headaches | <20 cp/mL | Latent syphilis infection. Testing for neurosyphilis negative |

| Cognitively Normal* | 52 | M | white | Treated Depressive Disorder | <20 cp/mL | Acute neuropathy in hands and feet. No evidence of cytoalbuminergic dissociation |

| Cognitively Normal* | 29 | M | white | No relevant PMH | 41 | New syphilis infection. Testing for neurosyphilis negative |

| MND | 53 | M | white | History of methamphetamine dependence | <20 cp/mL | Worsening cognitive function. Testing for CSF HIV viral load negative |

| MND | 67 | M | other | Treated Depressive Disorder | <20 cp/mL | Worsening cognitive function. Testing for CSF HIV viral load negative |

| MND | 64 | M | white | Diabetes | <20 cp/mL | Worsening cognitive function and weakness. Testing for CSF HIV viral load negative |

| HAD | 78 | M | white | Treated Depressive Disoder, Heart Failure, Chronic Kidney Disease |

<20 cp/mL | Rapidly worsening dementia on baseline HAD. Testing for CSF HIV viral load negative |

| HAD | 61 | M | other | Treated Bipolar Disorder | <20 cp/mL | Progressive weakness with dementia. Testing for CSF HIV viral load negative |

| HSV-1 | 25 | M | white | No relevant PMH | N/A | Fever and seizure |

| HSV-2 | 39 | F | white | Migraine history | N/A | New worsening headache |

| HSV-2 | 54 | F | white | History of HSV-2 meningitis | N/A | New worsening headache and neck pain |

| VZV | 85 | M | not reported | Dementia, atrial fibrillation, hypertension | N/A | Worsening cognitive function and seizure |

| VZV | 33 | M | white | No relevant PMH | N/A | Double vision |

Based on Provider Notes on the Clinical Examination Prior to Lumbar Puncture; all people listed as cognitively normal, MND or HAD have virally suppressed HIV infection on antiretroviral therapy; only past medical history relevant to cognitive function is reported for people with HIV. CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PMH, past medical history

Sample Processing Method

Our cost-effective method includes addition of 5% (final concentration) perchloric acid, which results in protein precipitation and separation of soluble and insoluble protein fractions. The vast majority of the highly abundant proteins remain in the insoluble fraction and is removed from the sample used for the subsequent analysis, which comprises the soluble fraction(Makszin, Kustan et al. 2019). Perchloric acid sample preparation method is as follows. After dilution of 50 μL plasma samples with 450 μL water, 5 % of perchloric acid (25 μL) is added and after vigorous agitation, the suspension is allowed to stand on ice for 15 min. Then samples are centrifuge for 15 min (4° C, 16 000×g). The supernatant is transferred and then mix with 50 μL of 1% trifluoroacetic acid and loaded onto a μSPE HLB plate, previously conditioned with 300 μL methanol and 500 μL of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid twice, for desalting and removal of perchloric acid. Elution of the proteins is done with 100 μL 90 % acetonitrile 0.1% TFA. Samples are dried with a Speedvac. The samples are then resuspended in 40 μL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and digested with sequencing grade trypsin (Promega) overnight at 37° C. Digestion was stopped by the addition of 10% formic acid (final volume of 50 μL). Without any further desalting strategy, 2 μL was injected into the LC-MS instrument.

LC/MS-based Plasma Proteome Mapping

All data were acquired using the same LC conditions. Samples were analyzed with a nano Elute liquid Chromatography (Bruker) coupled to a timsTOF Pro (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). Two microliters of tryptic digest of the supernatant were loaded onto a C18 UHPLC column 50 mm x 150 μm (1.6 μm particle size) from IonOpticks (Fitzroy, Australia). Mobile phase consisted of 0.1 % formic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase B). Peptides were separated by a 7 min gradient from 2% B to 34% B at 2 μL/min (total run time approx.15 min). For the Data Dependent Analysis (DDA), the parameters were set as follow: m/z range 100–1700, the mobility (1/K0) range was set to 0.7–1.45 Vs/cm2 and the accumulation time was 100 ms. Data Independent Analysis (DIA), we devised a diaPASEF (Meier, Brunner et al. 2020) method with four windows in each 75 ms diaPASEF scan with a 40 m/z window width, leading to 5 scans per cycle. The cycle time of our method is 450 ms. The other mass spectrometer parameters were set as follow: m/z range 400–1700, the mobility (1/K0) range was set to 0.7–1.45 Vs/cm2 and the accumulation time was of 75 ms.

LC/MS Data Analysis

The DDA runs were used to generate a spectral library in Spectronaut version 13.12.200217 (Biognosys). The DIA runs were also analyzed in Spectronaut version 13.12.200217 (Biognosys). Default BGS Factory settings were employed for both library generation with Pulsar and DIA analysis. Only DIA data were used for identification and quantification of proteins, and the subsequent statistical analysis. Results were filtered with a 1% FDR at both the precursor and protein level. All statistical analysis was performed using Perseus v 1.6.10.43 and GraphPad Prism 9. Protein-Protein Interaction Network was performed using string-db.org (Szklarczyk, Gable et al. 2019).

Results

Characteristics of Plasma Proteomics Study Population

A total of 13 plasma samples (11 male:2 female; median age (interquartile range): 53 years (39–64)) were processed in a single batch (Fig. 1b). Our plasma proteomic analysis identified a total of 438 proteins with an average of 355±18 proteins per sample. Initially, we compared 8 patients with virally suppressed HIV infection to 5 patients with CNS disease due to herpes infection. Subsequently, we also analyzed HAND patients by comparing 5 patients with HAND, which included 3 mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) and 2 HIV-associated dementia (HAD) patients, compared to 3 cognitively normal PWH (Table 1).

Distinguishing the Plasma Proteomes of Patients with HIV vs. Herpes Virus

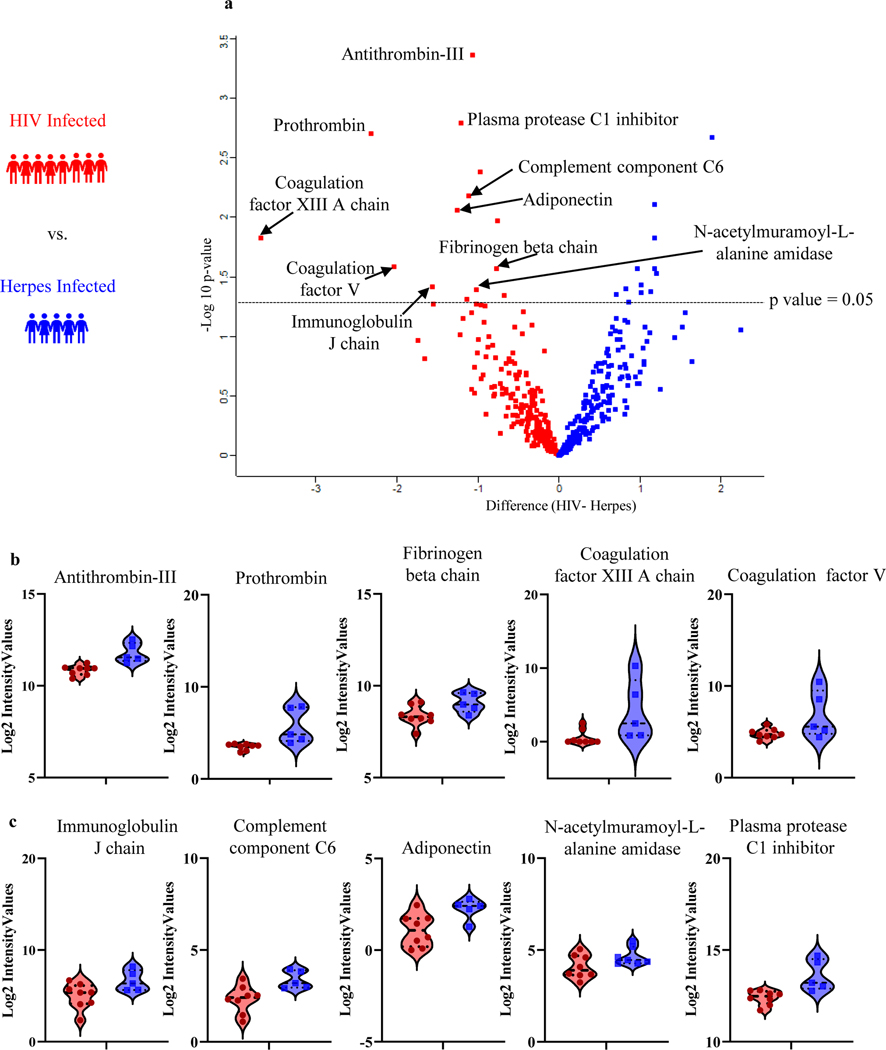

We investigated the plasma proteome, by first determining if proteins show differential abundance in the plasma of 8 PWH compared to 5 herpes virus infected patients, with both groups having undergone a clinically indicated lumbar puncture. From here onwards, we will refer to these two groups as “HIV” and/or “herpes virus”. Applying a p-value cutoff of 0.05 (i.e., equivalent to -log10 of 1.3), we identified 25 proteins that showed significant difference in abundance between HIV vs. herpes virus (Fig. 2a): 11 proteins were up- and 14 proteins were down-regulated in HIV (Table 2). We then performed a more detailed bioinformatic analysis of the differentially regulated proteins using the STRING Protein-Protein Interaction Network database (string-db.org) (Szklarczyk, Gable et al. 2019). While the 11 proteins upregulated in HIV did not significantly enrich in any pathways, the 14 proteins downregulated in HIV revealed biological pathways of interest such as blood coagulation (FDR 1.6e-06), inflammatory response (FDR 8.8e-05), antimicrobial humoral response (FDR 9.4e-05), and complement activation (FDR 1.7e-04). In our unique plasma proteomics comparison of HIV vs. herpes virus, in particular the proteins associated with blood coagulation stood out. Dysregulated coagulation is a hallmark of both HIV and herpes infections (Sutherland, Raynor et al. 1997, Funderburg 2014), though we believe this is the first quantitative comparison of coagulation proteins between HIV vs. herpes virus. We found the following 5 coagulation proteins significantly HIV vs. herpes virus: Antithrombin-III (SERPINC1), Prothrombin (F2), Coagulation factor XIII A (F13A1), Coagulation factor V (F5) and Fibrinogen beta chain (FGB) (Fig. 2b). Apart from the blood coagulation-associated proteins, Complement component C6 (C6), Plasma protease C1 inhibitor (SERPING1), N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (PGLYRP2), Immunoglobulin J chain (JCHAIN), and Adiponectin (ADIPOQ) (Fig. 2c) were amongst the 14 proteins significant downregulated in HIV vs. herpes virus.

Fig. 2.

Plasma proteome changes in HIV vs herpes viruses. (a)Volcano plot analysis of 8 HIV (red) and 5 herpes infected (blue) with p value cut off of 0.05 (i.e., equivalent to -log 10 of 1.3). (b) Violin plots of significantly different coagulation proteins downregulated in HIV. (c) Violin plots of significantly different proteins downregulated in HIV already described in literature

Table 2.

List of 25 significant proteins distinguishing HIV vs herpes

| Gene | UniProt ID | p-value | Fold Change | -Log10 p value | Log2 Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERPINC1 | P01008 | 0.0004 | 1.14 | 3.36 | −1.07 |

| SERPING1 | P05155 | 0.0016 | 1.46 | 2.79 | −1.21 |

| F2 | P00734 | 0.002 | 5.4 | 2.7 | −2.32 |

| IGKV3–20 | P01619 | 0.0021 | 3.55 | 2.67 | 1.88 |

| BTD | P43251 | 0.0042 | 0.95 | 2.38 | −0.98 |

| C6 | P13671 | 0.0066 | 1.23 | 2.18 | −1.11 |

| IGLV1–40 | P01703 | 0.0078 | 1.4 | 2.11 | 1.19 |

| ADIPOQ | Q15848 | 0.0088 | 1.57 | 2.06 | −1.25 |

| A1BG | P04217 | 0.0106 | 0.58 | 1.97 | −0.76 |

| CCDC80 | Q76M96 | 0.0149 | 1.39 | 1.83 | 1.18 |

| F13A1 | P00488 | 0.0149 | 13.53 | 1.83 | −3.68 |

| F5 | P12259 | 0.0262 | 4.15 | 1.58 | −2.04 |

| EMILIN2 | Q9BXX0 | 0.027 | 1.39 | 1.57 | 1.18 |

| FGB | P02675 | 0.0271 | 0.59 | 1.57 | −0.77 |

| SLC8A1 | P32418–5 | 0.0272 | 0.93 | 1.57 | 0.97 |

| IGHV1–69D | A0A0B4J2H0 | 0.0295 | 1.45 | 1.53 | 1.2 |

| CDH13 | P55290 | 0.0368 | 1.02 | 1.43 | 1.01 |

| JCHAIN | P01591 | 0.0383 | 2.43 | 1.42 | −1.56 |

| ENSA | O43768 | 0.0397 | 0.68 | 1.4 | 0.82 |

| IGFBP3 | P17936 | 0.0402 | 1.05 | 1.4 | −1.02 |

| AHNAK | Q09666 | 0.0424 | 1.29 | 1.37 | 1.14 |

| PI16 | Q6UXB8 | 0.0427 | 1.02 | 1.37 | 1.01 |

| REG1A | P05451 | 0.0447 | 0.5 | 1.35 | 0.71 |

| PGLYRP2 | Q96PD5 | 0.0452 | 0.45 | 1.35 | −0.67 |

| IGLV8-61 | A0A075B6I0 | 0.0484 | 1.28 | 1.32 | −1.13 |

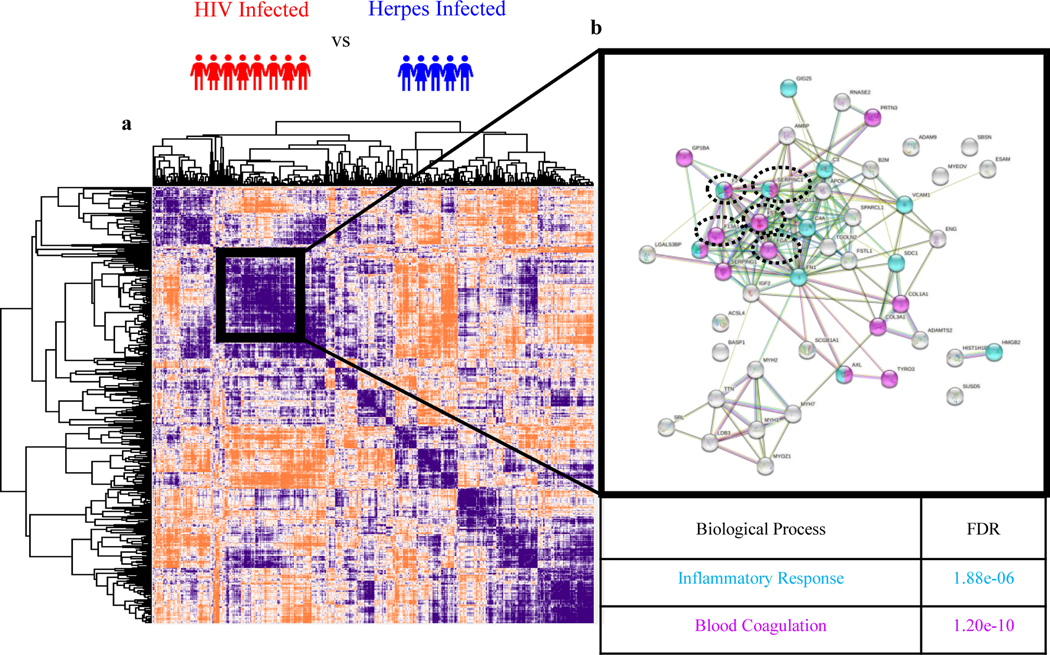

Given the limited statistical power of this small set of convenience samples, and to cast a wider net, we performed a Pearson’s protein-protein correlation to find additional proteins clustering together with the 5 significantly dysregulated coagulation proteins. A subcluster comprising all 5 coagulation proteins is apparent black square in (Fig.3a). This analysis identified 8 additional coagulation-associated proteins (marked by magenta coloring), making ‘blood coagulation’ the most significantly enriched pathway (FDR = 1.20 e-10) (Fig. 3b) in this subcluster (Table 3). The second most enriched pathway within this subcluster is inflammatory response with 11 proteins (FDR = 1.88 e-6) (Fig. 3b, light blue), with several proteins including two of our significantly dysregulated coagulation proteins Antithrombin-III (SERPINC1) and Prothrombin (F2) being assigned to both pathways (Table 3). This analysis highlights the cross-talk between blood coagulation and inflammation.

Fig. 3.

(a) Global map of all protein-protein interactions using Pearson correlation for HIV vs herpes viruses. (b) STRING Protein-Protein Interaction Network database (string-db.org) indicating which proteins coregulate in blood coagulation (magenta) and inflammatory response (blue) pathway. Five significantly dysregulated coagulation proteins are circled

Table 3.

List of 13 coagulation proteins and 11 inflammatory proteins coregulating with 5 significantly dysregulated coagulation proteins in HIV vs herpes

| Inflammatory Response | |

|---|---|

| Gene | UniProt ID |

| SERPINA3 | P01011 |

| C3 | P01024 |

| HMGB2 | P26583 |

| SDC1 | P18827 |

| VCAM1 | P19320 |

| C4A | P0C0L4 |

| FN1 | P02751 |

| Inflammatory Response and Blood Coagulation | |

|---|---|

| Gene | UniProt ID |

| F2 | P00734 |

| SERPINC1 | P01008 |

| F8 | P00451 |

| AXL | P30530 |

Plasma Proteomics Analysis Discovers Novel Biological Pathways and Plasma Biomarkers of HAND

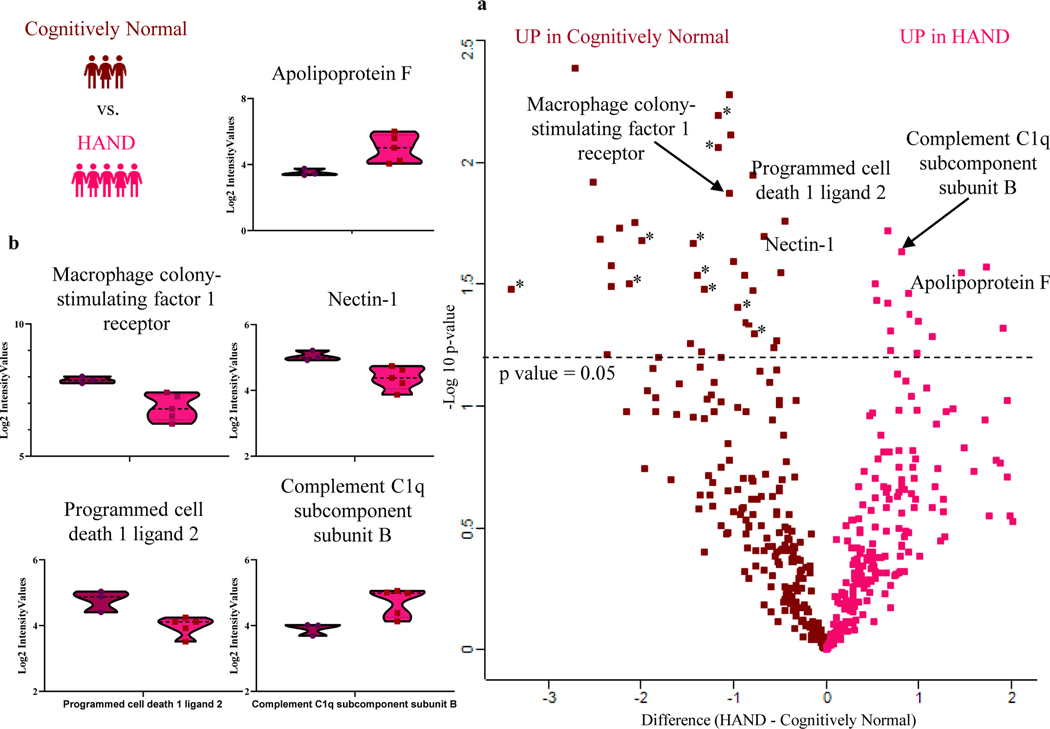

While we successfully distinguished the plasma proteome of HIV vs herpes virus infections in the context of CNS disease supporting the notion that our plasma proteomic platform is well suited to tackle the problems of interest. However, proteomic differences between HIV and herpes viruses may not have direct clinical applications. Given the high burden of cognitive impairment in PWH, we hypothesized the ability to distinguish the plasma proteome with known stages of HAND. Our proof-of-concept analysis of HAND included 5 HAND patients (2 HAD and 3 MND) compared to 3 cognitively normal PWH controls. Our volcano plot analysis using a p-value cut off of 0.05 (i.e. equivalent to -log10 of 1.3) showed 44 proteins with significant difference in abundance between HAND and cognitively normal PWH controls (Fig. 4a). We found 12 upregulated and 32 downregulated proteins in HAND vs. cognitively normal PWH controls (Table 4).

Fig. 4.

Plasma proteome changes in HAND vs cognitive normal PWH. (a) Volcano plot analysis of 5 HAND (red) and 3 cognitively normal (maroon) with p value cut off of 0.05 (i.e., equivalent to -log10 of 1.3). (b) Violin plots of significantly different proteins in HAND patients. * Indicates the various immunoglobulin constant and variable chains significantly downregulated in HAND

Table 4.

List of 44 significant proteins distinguishing HAND and cognitively normal

| Gene | UniProt ID | p-value | Fold Change | -Log10 p value | Log2 Fold Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITIH1 | P19827 | 0.0316 | 0.28 | 1.5 | 0.53 |

| KRTAP13-4 | Q3LI77 | 0.0323 | 5.39 | 1.49 | −2.32 |

| N/A | P0DOX2 | 0.0333 | 11.55 | 1.48 | −3.4 |

| IGKV1D-33 | P01593 | 0.0333 | 1.72 | 1.48 | −1.31 |

| PTPRJ | Q12913 | 0.0337 | 0.62 | 1.47 | −0.79 |

| APCS | P02743 | 0.0347 | 0.8 | 1.46 | 0.89 |

| PON1 | P27169 | 0.0367 | 0.29 | 1.44 | 0.54 |

| ALCAM | Q13740 | 0.037 | 0.39 | 1.43 | −0.62 |

| C1S | P09871 | 0.0378 | 0.44 | 1.42 | 0.67 |

| IGKV1-8 | A0A0C4DH67 | 0.0393 | 0.91 | 1.41 | −0.95 |

| CRACD | Q6ZU35 | 0.0419 | 2.77 | 1.38 | −1.67 |

| TTN | Q8WZ42 | 0.0421 | 0.81 | 1.38 | 0.9 |

| LAMP2 | P13473 | 0.0429 | 0.48 | 1.37 | −0.69 |

| GP6 | Q9HCN6 | 0.0447 | 0.98 | 1.35 | 0.99 |

| ADGRF5 | Q8IZF2 | 0.0455 | 3.33 | 1.34 | −1.82 |

| LAMP1 | P11279 | 0.0457 | 0.76 | 1.34 | −0.87 |

| CD58 | P19256 | 0.0462 | 0.7 | 1.34 | −0.84 |

| APOC2 | P02655 | 0.0479 | 3.62 | 1.32 | 1.9 |

| IGFBP5 | P24593 | 0.0495 | 0.49 | 1.31 | 0.7 |

| KIAA2012 | Q0VF49 | 0.0041 | 7.35 | 2.39 | −2.71 |

| EGFR | P00533 | 0.0053 | 1.1 | 2.28 | −1.05 |

| IGKV1D-13 | A0A0B4J2D9 | 0.0065 | 1.34 | 2.19 | −1.16 |

| SERPINE2 | P07093 | 0.0078 | 1.05 | 2.11 | −1.03 |

| IGLV6-57 | P01721 | 0.0087 | 1.35 | 2.06 | −1.16 |

| PDCD1LG2 | Q9BQ51 | 0.0112 | 0.63 | 1.95 | −0.79 |

| KIAA1210 | Q9ULL0 | 0.012 | 6.35 | 1.92 | −2.52 |

| CSF1R | P07333 | 0.0134 | 1.08 | 1.87 | −1.04 |

| PLTP | P55058 | 0.0175 | 0.2 | 1.76 | −0.44 |

| HRNR | Q86YZ3 | 0.0177 | 4.28 | 1.75 | −2.07 |

| PRB4 | P10163 | 0.0185 | 4.95 | 1.73 | −2.22 |

| AZGP1 | P25311 | 0.019 | 0.44 | 1.72 | 0.66 |

| NECTIN1 | Q15223 | 0.0202 | 0.46 | 1.7 | −0.68 |

| KIAA1958 | Q8N8K9 | 0.0207 | 5.92 | 1.68 | −2.43 |

| IGHV3-15 | A0A0B4J1V0 | 0.021 | 3.96 | 1.68 | −1.99 |

| IGHV3-21 | A0A0B4J1V1 | 0.0215 | 2.08 | 1.67 | -1.44 |

| C1QB | P02746 | 0.0232 | 0.65 | 1.63 | 0.81 |

| ICAM1 | P05362 | 0.0254 | 0.99 | 1.6 | −1 |

| KIAA2026 | Q5HYC2 | 0.0266 | 5.37 | 1.57 | −2.32 |

| ACSL4 | O60488 | 0.0269 | 3.01 | 1.57 | 1.73 |

| APOF | Q13790 | 0.0283 | 2.14 | 1.55 | 1.46 |

| LSAMP | Q13449 | 0.0285 | 0.24 | 1.54 | −0.49 |

| DPEP2 | Q9H4A9 | 0.029 | 0.79 | 1.54 | −0.89 |

| IGHV3–53 | P01767 | 0.029 | 1.93 | 1.54 | −1.39 |

| IGLV3–27 | P01718 | 0.0314 | 4.53 | 1.5 | −2.13 |

A more in-depth bioinformatic analysis of the 44 significant proteins using STRING Protein-Protein Interaction Network database (Szklarczyk, Gable et al. 2019) revealed significant enrichment of several pathways: the 12 proteins upregulated in HAND were associated with acute inflammatory response (FDR = 0.03), classical complement activation (FDR = 0.03), and lipid transport (FDR = 0.03) and the 32 proteins downregulated in HAND revealed immune response pathways (FDR=0.001) (Table 4).

The proteins significantly upregulated in HAND associated with inflammation and the classical complement system included Serum amyloid P-component (APCS), Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B (C1QB) and Complement C1s subcomponent (C1S). The proteins significantly downregulated in HAND related to immune response pathway included Programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 (PDCD1LG2), Nectin-1 (NECTIN1), Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) and CD166 antigen (ALCAM). The significantly downregulated lipid transport pathway proteins were Apolipoprotein F (APOF), Apolipoprotein C-II (APOC2) and Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 4 (ACSL4). Violin plots of a subset of these proteins are shown in (Fig. 4b).

The notion of a dysregulated immune system in the context of HAND was underscored by the observation that various immunoglobulin constant and variable chains were consistently downregulated in HAND vs cognitively normal PWH controls with p-values ranging from 0.0087 to 0.031 and fold changes ranging from 0.45 to 0.23.

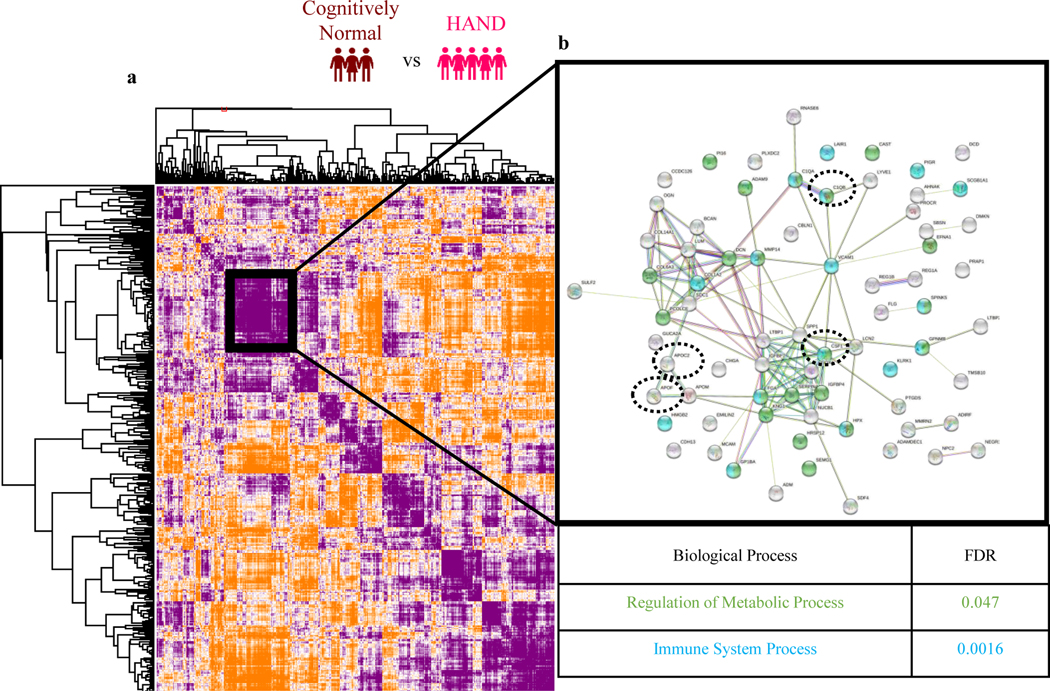

Being particularly interested in the complement pathway proteins, we performed a Pearson’s protein-protein correlation to cast a wider net and to identify those proteins sharing similar trajectories with the following significant proteins (Fig.5a): Macrophage colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B (C1QB), Apolipoprotein F (APOF) and Apolipoprotein C-II (APOC2) (Fig. 5a). STRING Protein-Protein Interaction Network database (Szklarczyk, Gable et al. 2019) on this protein subcluster with similar trajectories identified a total of 35 proteins associated with metabolic processes (FDR=0.047) (Fig. 5b, green) and 22 proteins associated with immune system processes (FDR=0.0016) (Fig. 5b, blue, and Table 5).

Fig. 5.

(a) Global map of all protein-protein interactions using Pearson correlation for HAND vs cognitively normal. STRING Protein-Protein Interaction Network database (string-db.org) indicating which proteins coregulate in regulation of metabolic process pathway (green) and immune system process (blue) pathway. Significant proteins from our dataset are circled

Table 5.

List of 35 metabolic process proteins and 22 immune system process proteins coregulating with 4 significantly dysregulated proteins in HAND vs cognitively normal PWH

| Immune System | |

|---|---|

| Gene | UniProt ID |

| DCD | P81605 |

| PIGR | P01833 |

| RNASE6 | Q93091 |

| LAIR1 | Q6GTX8 |

| VCAM1 | P19320 |

| COL1A2 | P08123 |

| LCN2 | P80188 |

| SDC1 | P18827 |

| ADAMDEC1 | O15204 |

| CHGA | P10645 |

| ADM | P35318 |

| Immune System and Metabolic Process | |

|---|---|

| Gene | UniProt ID |

| C1QB | P02746 |

| C1QA | P02745 |

| NPC2 | P61916 |

| ADAM9 | Q13443 |

| KLRK1 | P26718 |

| CSF1 | P09603 |

| QSOX1 | O00391 |

| FGA | P02671 |

| KNG1 | P01042 |

| HMGB2 | P26583 |

| SEMG1 | P04279 |

| Metabolic Process | |

|---|---|

| Gene | UniProt ID |

| GP1BA | P07359 |

| SCGB1A1 | P11684 |

| AHNAK | Q09666 |

| CAST | P20810 |

| PI16 | Q6UXB8 |

| EFNA1 | P20827 |

| PRAP1 | Q96NZ9 |

| MMP14 | P50281 |

| LUM | P51884 |

| SPINK5 | Q9NQ38 |

| COL6A3 | P12111 |

| PCOLCE | Q15113 |

| HRSP12 | P52758 |

| GUCA2A | Q02747 |

| APOC2 | P02655 |

| GPNMB | Q14956 |

| SERPINA10 | Q9UK55 |

| CDH13 | P55290 |

| SPP1 | P10451 |

| HPX | P02790 |

| ADIRF | Q15847 |

| IGFBP7 | Q16270 |

| IGFBP4 | P22692 |

| DCN | P07585 |

Biological Significance and Study Limitations

In our study, we sought to investigate differences in the plasma proteomes of patients infected with HIV vs. herpes virus. All patients enrolled in this study were evaluated for neurological symptoms. The PWH were virally suppressed by ART therapy and were clinically assessed and stratified as either cognitively normal, MND, or HAD as result of the neurological evaluation. No attempts were made to detect viral proteins, also because the PWH were virally suppressed, i.e., the detection of HIV-derived proteins was considered unlikely.

Our high throughput plasma proteomics method identified and quantified over 400 plasmas proteins in 15 minutes per samples, i.e., a throughput ranging of 100 samples/day. The set-up used for the experiment has an overhead time for loading and washing the sample, and washing and regenerating the column resulting in an overall run time of ~15 minutes. The actual acquisition time of 7 minutes allows for a theoretical throughput of up to 200 samples/day, which has been realized in the meantime with the upgrade of our hardware to include an Evosep ONE system (Bache, Geyer et al. 2018) to replace the conventional nanoflow UPLC system.

By applying our state-of-the-art high throughput-compatible plasma proteomics pipeline, we found several significantly altered proteins and associated biological pathways comparing HIV vs. herpes virus. The reason for using the herpes controls (instead of healthy, i.e., non-virally infected controls), was to remove any general viral infection-associated changes. As such, identifying differences between the different types of infections provide interesting insights. While comparisons between the two viruses are not routinely performed, both viruses result in chronic infections and are neuroinvasive. As such, proteomic analyses could further our understanding regarding biological pathways involved in acute reactivation and chronic infection. We also compared HAND patients at two stages, MND and HAD, to cognitively normal PWH controls. Our results were consistent with literature and revealed novel functional insight and disease-related changes in the plasma proteome.

Pathway analysis of all 14 significantly downregulated proteins in HIV revealed biological pathways related to blood coagulation, complement activation, antimicrobial humoral response and inflammation. Coagulation activation during viral infection is an important host response to limit the spread of disease (Antoniak and Mackman 2014). However, an imbalance in coagulation activation leads to detrimental consequences of vascular disease and organ failure (Antoniak and Mackman 2014). Dysregulated coagulation and resulting inflammation in PWH have been well described (Graham, Mwilu et al. 2013, Funderburg and Lederman 2014, Montoya, Iudicello et al. 2017). Dysregulated levels of von Willebrand factor (vWf), D-dimer, fibrinogen, thrombin and Factor VIII have been found in plasma of HIV infected patients even with ART therapy (Graham, Mwilu et al. 2013, Funderburg and Lederman 2014). Similarly, dysregulated coagulation has also been described in herpes infection (Gershom, Sutherland et al. 2010, Gershom, Vanden Hoek et al. 2012) (Sutherland, Raynor et al. 1997, Lin, Sutherland et al. 2020). Coagulation factors FVIIa, FVII and FVa are known to be activated with HSV-1, HSV-2 and CMV virus infection (Sutherland, Raynor et al. 1997, Lin, Sutherland et al. 2020). Thrombin was found dysregulated in VZV plasma compared to healthy controls (Wang, Shen et al. 2020). The significantly changed coagulation proteins from our data set are not only consistent with literature, but also provided virus specific pathological differences for dysregulated coagulation in HIV vs. herpes virus.

The following proteins from the 14 proteins that showed significant downregulation in HIV vs. herpes virus have previously been described in the HIV and herpes virus literature: Complement component C6 (C6), Plasma protease C1 inhibitor (SERPING1), N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (PGLYRP2), Immunoglobulin J chain (JCHAIN), and Adiponectin (ADIPOQ). The complement system plays an important role in both herpes and HIV infection (Brockman and Knipe 2008, Liu, Dai et al. 2014). The differential abundance of Complement component C6 (C6) and Plasma protease C1 inhibitor (SERPING1) in HIV vs. herpes virus underscored our ability to identify possible neuropathological induced and virus specific differences. N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (PGLYRP2) and Immunoglobulin J chain (JCHAIN) are associated with antimicrobial humoral response. Immunoglobulins have been described as novel biomarkers to monitor viral reservoirs (Das, Devadhasan et al. 2020). Adiponectin (ADIPOQ) is an adipocyte-specific cytokine that has important roles in anti-inflammatory functions and metabolic effects including enhancing insulin sensitivity with potential cardioprotective effects. Adiponectin is abnormal in the setting of HIV and lipodystrophy and recently associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease in HIV (Donnell, Baeten et al. 2014, Funderburg 2014, Godfrey, Bremer et al. 2019). Our bioinformatic analysis of the downregulated proteins in HIV infection accurately reflects many known proteins and pathways related to HIV pathophysiology (Boasso, Shearer et al. 2009) underscoring the value of plasma proteomics to readily discover proteins of viral infection in general but also in virus specific neurological complications and its neuropathophysiology.

Our limited understanding of the neuropathological mechanisms of HAND and lack of molecularly defined biomarkers makes diagnosing and stratification difficult (Clifford and Ances 2013). Previous proteomic biomarker studies have attempted to stratify disease and few have explored biomarkers of HAND in blood, but to the best of our knowledge none in plasma (Williams, Naude et al. 2021). According to this review, two studies from Wiederin et al. and Rozek et al. attempted to investigate the serum proteome of patients of HIV-1 infected cognitive normal vs. HIV-associated dementia patients. When comparing these serum proteomic studies to our plasma proteomics, we found stark differences as our plasma proteomics study used a more appropriate proteomic technology resulting in better quantitative and in depth bioinformatic analysis. First, our proteomic technology includes a high throughput sample processing method unlike the gel electrophoresis approach used in the other 2 serum studies, we eliminate numerous sample handling steps, which can introduce contaminations and technical variability, and increases the risk of sample losses. Second, our state of the art mass spectrometer provides three dimensional separation of ions reaching far superior resolution and more confident spectra and hence more confident protein identifications. This technology was unfathomable at the time of the two serum studies and only consisted of slow and laborious 2-dimensional separation and much lower resolution. Wiederin et al. used a qualitative identification approach which does not reveal directionality or abundance. Our in-depth quantitative analysis identified 44 significant proteins, 12 upregulated in HAND and 32 downregulated in HAND, included downstream more advanced bioinformatic pathway and co regulation analysis. Our results not only confirmed HAND literature but also revealed potential disease state specific markers of HAND which could be used to stratify HAND patients since our cohort, unlike the serum studies, included 2 stages of HAND, MND and HAD.. We would like to also point out that as far as we know, the patients used in both serum studies (Wiederin et al. and Rozek et al.) were not virally suppressed, hence it is difficult to determine if the difference in their cognitively normal vs HAD results is a result of HIV infection or resulting neurological complications. In contrast, all our patients were virally suppressed and seen in the clinic due to neurological complications.

Our state-of-the-art plasma proteomics technology discovered in 44 significant proteins which allowed us to discriminate between HAD/MND patients from cognitively normal PWH controls. To our knowledge, few of these proteins have been described before in the context of HAND. However, the biological pathways associated with these proteins of significantly differential abundance are well known providing credibility to the detected differences in the plasma proteome composition.

Neuroinflammation is considered a key driver of neurodegeneration in HAND patients. The Strategies for the Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) study found increased C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 to be markers of inflammation in HAND patients (Baker, Sharma et al. 2017) highlighting the involvement of the acute inflammatory response in the development and progression of HAND (Xu, Zhang et al. 2009, Liu, Dai et al. 2014, Hong and Banks 2015, Swanta, Aryal et al. 2020). This is in concordance with our study, which identified three proteins associated with the acute inflammatory response and classical complement activation: i) Serum amyloid P-component (APCS), ii) Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B (C1QB), iii) Complement C1s subcomponent (C1S), which could potentially be used for an improved blood-based diagnosis and/or stratification. Our findings related to inflammation confirmed existing HIV and HAND literature. (Gannon, Khan et al. 2011, Mahajan, Ordain et al. 2021).

Neuroinflammation in HAND is also associated with dysregulated metabolic homeostasis in the brain (Cotto, Natarajanseenivasan et al. 2019). Our data further underscored this notion as 9 out of the 12 proteins significantly upregulated in HAND were associated with metabolic processes. Some metabolic proteins to note are: Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 (ITIH1), Serum paraoxonase/arylesterase 1 (PON1), Apolipoproteins C-II (APOC2) and F (APOF), Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 5 (IGFBP5) and Zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein (AZGP1). Elevated levels of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitory protein families have been found before in serum from patients with HAND (Wiederin, Rozek et al. 2009) confirming our findings. Our analysis also revealed 2 apolipoproteins (Apolipoprotein C-II (APOC2) and Apolipoprotein F (APOF)) upregulated in HAND. While Apolipoprotein E is a well-established risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease (Michaelson 2014), there is debate regarding the implication of the various apolipoproteins in HAND (Geffin and McCarthy 2018). Dysregulated levels of insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins have been described in CSF and plasma to be associated with HIV infection and possibly HAND (Suh, Lo et al. 2015). Furthermore, our more inclusive co-regulation analysis found a total of 35 proteins associated with metabolic pathways strongly supporting the notion known in literature that dysregulated metabolism is associated with HAND (McCutchan, Marquie-Beck et al. 2012, Mukerji, Locascio et al. 2016, Rubin, Gustafson et al. 2019). Proteins that showed significant downregulation in HAND and were associated with immune responses included Programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 (PDCD1LG2), Nectin-1 (NECTIN1) and Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R). Programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 (PDCD1LG2) plays a major role in cancer and serves as an immunological checkpoint marker (Li, Chen et al. 2019). Nectin-1 (NECTIN1) plays a role in viral entry (Deschamps, Dogrammatzis et al. 2017), and Macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) has been described as being associated with HIV CNS disease in human and macaque (Knight, Brill et al. 2018, Irons, Meinhardt et al. 2019). This concordance between our findings and the literature on these proteins suggests that our method may prove robust for the discovery of novel plasma markers to distinguish HAND from cognitively normal PWH.

Our study had limitations: Foremost, as this study is intended as a proof of concept, we employed a small sample size with the goal of demonstrating feasibility of plasma as body fluid that can be used for identifying potential drivers and novel functional and mechanistic insight into viral pathogens and HAND pathologies. We would like to reiterate due to the lack of validation and small sample size, our findings do not focus as much on the novel biomarker aspect, instead we highlighted our method recapitulating known proteins and pathways from HIV and HAND literature as more relevant, as it confirmed out approach. As this was a clinical convenience cohort, it is possible that our presumed cognitively normal PWH may have asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI) when tested formally on a neuropsychological battery in a research setting. Leveraging larger studies from virally suppressed PWH with longitudinal neuropsychological testing and timed blood collections, we can validate findings and determine whether plasma markers within inflammatory and coagulation networks predict future cognitive impairment. Furthermore, we lack non-CNS involved control samples for the herpes cohort. This will be an important addition to the next iteration as predictive blood-based biomarkers that can differentiate between limited mucocutaneous disease versus disease with CNS involvement in herpes could assist in clinical decision-making regarding diagnostic procedures and initiating empiric oral or intravenous therapy. While our results were congruent with prior findings from literature supporting the validity of our proof-of-concept study, an independent and much larger validation cohort study is still required to determine if our findings can be used for diagnosis, stratification and/or prognosis and how these findings compare to other biofluid compartments including the CSF.

In conclusion, our study does show that disease-associated changes in the plasma proteome closely resemble the molecular changes that have been described HIV, herpes virus, and HAND. As such, this study supports the notion that our high throughput plasma proteomics method is an appropriate source for the measurement of disease-modifying therapeutics for neurological complications associated with viral infection. Our methodology of characterizing plasma proteome in less than 10 minutes can reduce a critical barrier in identifying potential proteins involved in disease states in a variety of viral infections. In the future, plasma proteomics can be employed to 1) uncover new proteins and biological pathways underlying HIV, herpes virus, and HAND, 2) identify disease-stage-specific signatures of HAND using these data and thus create a biomarker-based stratification system for HAND patients, and 3) to tailor novel precision medicine approaches for the treatment of serious infection and diseases with life-long consequences.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael J. Leone and Kiana Keller for their contributions to the design and oversight of the PEMS study, and Emily Rudmann for her help editing the manuscript. The purchase of the timsTOF Pro mass spectrometer was made possible by the administrative supplement 3R01GM112007-04S1 to J.S. S.M. is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health at the National Institutes of Health (grant number K23MH115812), James S. McDonnell Foundation and is a 2021-2022 Rappaport Scholar. The work is in part funded by 5U24AI152179-02 to H.S.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V and Wojna VE (2007). “Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.” Neurology 69(18): 1789–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniak S and Mackman N (2014). “Multiple roles of the coagulation protease cascade during virus infection.” Blood 123(17): 2605–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache N, Geyer PE, Bekker-Jensen DB, Hoerning O, Falkenby L, Treit PV, Doll S, Paron I, Muller JB, Meier F, Olsen JV, Vorm O and Mann M (2018). “A Novel LC System Embeds Analytes in Preformed Gradients for Rapid, Ultra-robust Proteomics.” Mol Cell Proteomics 17(11): 2284–2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JV, Sharma S, Grund B, Rupert A, Metcalf JA, Schechter M, Munderi P, Aho I, Emery S, Babiker A, Phillips A, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD, Lane HC and Group ISS (2017). “Systemic Inflammation, Coagulation, and Clinical Risk in the START Trial.” Open Forum Infect Dis 4(4): ofx262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennike TB, Barnaby O, Steen H and Stensballe A (2015). “Characterization of the porcine synovial fluid proteome and a comparison to the plasma proteome.” Data Brief 5: 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennike TB, Bellin MD, Xuan Y, Stensballe A, Moller FT, Beilman GJ, Levy O, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Andersen V, Steen J, Conwell DL and Steen H (2018). “A Cost-Effective High-Throughput Plasma and Serum Proteomics Workflow Enables Mapping of the Molecular Impact of Total Pancreatectomy with Islet Autotransplantation.” J Proteome Res 17(5): 1983–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennike TB and Steen H (2017). “High-Throughput Parallel Proteomic Sample Preparation Using 96-Well Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Membranes and C18 Purification Plates.” Methods Mol Biol 1619: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger ST, Ahmed S, Muntel J, Cuevas Polo N, Bachur R, Kentsis A, Steen J and Steen H (2015). “MStern Blotting-High Throughput Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Membrane-Based Proteomic Sample Preparation for 96-Well Plates.” Mol Cell Proteomics 14(10): 2814–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boasso A, Shearer GM and Chougnet C (2009). “Immune dysregulation in human immunodeficiency virus infection: know it, fix it, prevent it?” J Intern Med 265(1): 78–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockman MA and Knipe DM (2008). “Herpes simplex virus as a tool to define the role of complement in the immune response to peripheral infection.” Vaccine 26 Suppl 8: I94–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford DB and Ances BM (2013). “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder.” Lancet Infect Dis 13(11): 976–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotto B, Natarajanseenivasan K and Langford D (2019). “HIV-1 infection alters energy metabolism in the brain: Contributions to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.” Prog Neurobiol 181: 101616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Devadhasan A, Linde C, Broge T, Sassic J, Mangano M, O’Keefe S, Suscovich T, Streeck H, Irrinki A, Pohlmeyer C, Min-Oo G, Lin S, Weiner JA, Cihlar T, Ackerman ME, Julg B, Deeks S, Lauffenburger DA and Alter G (2020). “Mining for humoral correlates of HIV control and latent reservoir size.” PLoS Pathog 16(10): e1008868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps T, Dogrammatzis C, Mullick R and Kalamvoki M (2017). “Cbl E3 Ligase Mediates the Removal of Nectin-1 from the Surface of Herpes Simplex Virus 1-Infected Cells.” J Virol 91(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, Brantley J, Bangsberg DR, Haberer JE, Mujugira A, Mugo N, Ndase P, Hendrix C and Celum C (2014). “HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention.” J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 66(3): 340–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers C, Arendt G, Hahn K, Husstedt IW, Maschke M, Neuen-Jacob E, Obermann M, Rosenkranz T, Schielke E, Straube E and A. u. N.-I. German Association of Neuro (2017). “HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorder: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment.” J Neurol 264(8): 1715–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburg NT (2014). “Markers of coagulation and inflammation often remain elevated in ARTtreated HIV-infected patients.” Curr Opin HIV AIDS 9(1): 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburg NT and Lederman MM (2014). “Coagulation and morbidity in treated HIV infection.” Thromb Res 133 Suppl 1: S21–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon P, Khan MZ and Kolson DL (2011). “Current understanding of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders pathogenesis.” Curr Opin Neurol 24(3): 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geffin R and McCarthy M (2018). “Aging and Apolipoprotein E in HIV Infection.” J Neurovirol 24(5): 529–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershom ES, Sutherland MR, Lollar P and Pryzdial EL (2010). “Involvement of the contact phase and intrinsic pathway in herpes simplex virus-initiated plasma coagulation.” J Thromb Haemost 8(5): 1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershom ES, Vanden Hoek AL, Meixner SC, Sutherland MR and Pryzdial EL (2012). “Herpesviruses enhance fibrin clot lysis.” Thromb Haemost 107(4): 760–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey C, Bremer A, Alba D, Apovian C, Koethe JR, Koliwad S, Lewis D, Lo J, McComsey GA, Eckard A, Srinivasa S, Trevillyan J, Palmer C and Grinspoon S (2019). “Obesity and Fat Metabolism in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Individuals: Immunopathogenic Mechanisms and Clinical Implications.” J Infect Dis 220(3): 420–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham SM, Mwilu R and Liles WC (2013). “Clinical utility of biomarkers of endothelial activation and coagulation for prognosis in HIV infection: a systematic review.” Virulence 4(6): 564–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S and Banks WA (2015). “Role of the immune system in HIV-associated neuroinflammation and neurocognitive implications.” Brain Behav Immun 45: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irons DL, Meinhardt T, Allers C, Kuroda MJ and Kim WK (2019). “Overexpression and activation of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor in the SIV/macaque model of HIV infection and neuroHIV.” Brain Pathol 29(6): 826–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight AC, Brill SA, Queen SE, Tarwater PM and Mankowski JL (2018). “Increased Microglial CSF1R Expression in the SIV/Macaque Model of HIV CNS Disease.” J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 77(3): 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AH, Shannon CP, Amenyogbe N, Bennike TB, Diray-Arce J, Idoko OT, Gill EE, BenOthman R, Pomat WS, van Haren SD, Cao KL, Cox M, Darboe A, Falsafi R, Ferrari D, Harbeson DJ, He D, Bing C, Hinshaw SJ, Ndure J, Njie-Jobe J, Pettengill MA, Richmond PC, Ford R, Saleu G, Masiria G, Matlam JP, Kirarock W, Roberts E, Malek M, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Singh A, Angelidou A, Smolen KK, Consortium E, Brinkman RR, Ozonoff A, Hancock REW, van den Biggelaar AHJ, Steen H, Tebbutt SJ, Kampmann B, Levy O and Kollmann TR (2019). “Dynamic molecular changes during the first week of human life follow a robust developmental trajectory.” Nat Commun 10(1): 1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Chen L and Jiang J (2019). “Role of programmed cell death ligand-1 expression on prognostic and overall survival of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Medicine (Baltimore) 98(16): e15201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin BH, Sutherland MR, Rosell FI, Morrissey JH and Pryzdial ELG (2020). “Coagulation factor VIIa binds to herpes simplex virus 1-encoded glycoprotein C forming a factor X-enhanced tenase complex oriented on membranes.” J Thromb Haemost 18(6): 1370–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Dai S, Gordon J and Qin X (2014). “Complement and HIV-I infection/HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.” J Neurovirol 20(2): 184–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Surkan PJ, Irwin MR, Treisman GJ, Breen EC, Sacktor N, Stall R, Wolinsky SM, Jacobson LP and Abraham AG (2019). “Inflammation and Risk of Depression in HIV: Prospective Findings From the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.” Am J Epidemiol 188(11): 1994–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan SD, Ordain NS, Kutscher H, Karki S and Reynolds JL (2021). “HIV Neuroinflammation: The Role of Exosomes in Cell Signaling, Prognostic and Diagnostic Biomarkers and Drug Delivery.” Front Cell Dev Biol 9: 637192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makszin L, Kustan P, Szirmay B, Pager C, Mezo E, Kalacs KI, Paszthy V, Gyorgyi E, Kilar F, Ludany A and Koszegi T (2019). “Microchip gel electrophoretic analysis of perchloric acid-soluble serum proteins in systemic inflammatory disorders.” Electrophoresis 40(3): 447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan JA, Marquie-Beck JA, Fitzsimons CA, Letendre SL, Ellis RJ, Heaton RK, Wolfson T, Rosario D, Alexander TJ, Marra C, Ances BM, Grant I and Group C (2012). “Role of obesity, metabolic variables, and diabetes in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder.” Neurology 78(7): 485–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier F, Brunner AD, Frank M, Ha A, Bludau I, Voytik E, Kaspar-Schoenefeld S, Lubeck M, Raether O, Bache N, Aebersold R, Collins BC, Rost HL and Mann M (2020). “diaPASEF: parallel accumulation-serial fragmentation combined with data-independent acquisition.” Nat Methods 17(12): 1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson DM (2014). “APOE epsilon4: the most prevalent yet understudied risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.” Alzheimers Dement 10(6): 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JL, Iudicello J, Oppenheim HA, Fazeli PL, Potter M, Ma Q, Mills PJ, Ellis RJ, Grant I, Letendre SL, Moore DJ and Group HIVNRP (2017). “Coagulation imbalance and neurocognitive functioning in older HIV-positive adults on suppressive antiretroviral therapy.” AIDS 31(6): 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji SS, Locascio JJ, Misra V, Lorenz DR, Holman A, Dutta A, Penugonda S, Wolinsky SM and Gabuzda D (2016). “Lipid Profiles and APOE4 Allele Impact Midlife Cognitive Decline in HIV-Infected Men on Antiretroviral Therapy.” Clin Infect Dis 63(8): 1130–1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntel J, Xuan Y, Berger ST, Reiter L, Bachur R, Kentsis A and Steen H (2015). “Advancing Urinary Protein Biomarker Discovery by Data-Independent Acquisition on a Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer.” J Proteome Res 14(11): 4752–4762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH, Gustafson D, Hawkins KL, Zhang L, Jacobson LP, Becker JT, Munro CA, Lake JE, Martin E, Levine A, Brown TT, Sacktor N and Erlandson KM (2019). “Midlife adiposity predicts cognitive decline in the prospective Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.” Neurology 93(3): e261–e271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LH and Maki PM (2019). “HIV, Depression, and Cognitive Impairment in the Era of Effective Antiretroviral Therapy.” Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 16(1): 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh HS, Lo Y, Choi N, Letendre S and Lee SC (2015). “Insulin-like growth factors and related proteins in plasma and cerebrospinal fluids of HIV-positive individuals.” J Neuroinflammation 12: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland MR, Raynor CM, Leenknegt H, Wright JF and Pryzdial EL (1997). “Coagulation initiated on herpesviruses.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94(25): 13510–13514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanta N, Aryal S, Nejtek V, Shenoy S, Ghorpade A and Borgmann K (2020). “Blood-based inflammation biomarkers of neurocognitive impairment in people living with HIV.” J Neurovirol 26(3): 358–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, Jensen LJ and Mering CV (2019). “STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets.” Nucleic Acids Res 47(D1): D607–D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Shen H, Deng H, Pan H, He Q, Ni H, Tao J, Liu S, Xu L and Yao M (2020). “Quantitative proteomic analysis of human plasma using tandem mass tags to identify novel biomarkers for herpes zoster.” J Proteomics 225: 103879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederin J, Rozek W, Duan F and Ciborowski P (2009). “Biomarkers of HIV-1 associated dementia: proteomic investigation of sera.” Proteome Sci 7: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ME, Naude PJW and van der Westhuizen FH (2021). “Proteomics and metabolomics of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: A systematic review.” J Neurochem. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang C, Jia L, Wen C, Liu H, Wang Y, Sun Y, Huang L, Zhou Y and Song H (2009). “A novel approach to inhibit HIV-1 infection and enhance lysis of HIV by a targeted activator of complement.” Virol J 6: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterberg H and Burnham SC (2019). “Blood-based molecular biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease.” Mol Brain 12(1): 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]