Abstract

Plant products are widely used for health and disease management. However, besides their therapeutic effects, some plants also have potential toxic activity. Calotropis procera is a well-known laticifer plant having pharmacologically active proteins playing a therapeutically significant role in curing diseases like inflammatory disorders, respiratory diseases, infectious diseases, and cancers. The present study was aimed to investigate the antiviral activity and toxicity profile of the soluble laticifer proteins (SLPs) obtained from C. procera. Different doses of rubber free latex (RFL) and soluble laticifer protein (ranging from 0.019 to 10 mg/mL) were tested. RFL and SLPs were found to be active in a dose-dependent manner against NDV (Newcastle disease virus) in chicken embryos. Embryotoxicity, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and mutagenicity of RFL and SLP were examined on chicken embryos, BHK-21 cell lines, human lymphocytes, and Salmonella typhimurium, respectively. It was revealed that RFL and SLP possess embryotoxic, cytotoxic, genotoxic, and mutagenic activity at higher doses (i.e., 1.25–10 mg/mL), while low doses were found to be safe. It was also observed that SLP showed a rather safer profile as compared to RFL. This might be due to the filtration of some small molecular weight compounds at the time of purification of SLPs through a dialyzing membrane. We suggest that SLPs could be used therapeutically against viral disorders but the dose should be critically monitored.

1. Introduction

Plants with potential therapeutic effects are being widely used around the world especially in poorly resourced areas because of their safe and less toxic profile as compared to synthetic medicinal products. These phytochemicals are active against a number of diseases including inflammatory disorders, infectious diseases, and even cancers. However, besides their potential benefits, some plants have been reported to possess toxicity.1

Calotropis procera (family Asclepiadaceae) has been known for the medicinal characteristics of its different parts, i.e., leaves, roots, and bark, for various human and animal ailments.2C. procera is enriched with a range of biologically active phytoconstituents including alkaloids, tannins,3 resins, cardiac glycosides, lipids, terpenes, steroids, and flavonoids.4 These phytoconstituents result in significant remedial properties of C. procera as analgesic, antiulcer,5 anthelmintic,6 antitumor,7 antidiarrheal, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective agents.8

Among various constituents of C. procera, laticifer proteins have been found to be very popular for their pharmacologically active nature because they are anti-inflammatory9 and they have been proven to address coagulative abnormalities10 and used to cure tumors as they are cytotoxic to various human cancerous cell lines.11 Pharmacologically active proteins of latex could be separated by a number of techniques such as the acid precipitation method,12 acetone precipitation method,13 ion-exchange chromatography,11a,14 and gel filtration chromatography15 (GFC). GFC is a well-known technique to separate out proteins obtained from plants based on their molecular weights.16

It is found that soluble laticifer proteins (SLPs) probably modulate the immune system of animals by various mechanisms like controlling histamine release, modifying nitric oxide synthesis, and controlling the release of cytokines.17 Researchers have found that laticifer proteins act on DNA and alter the topology of DNA.11a SLPs cause reduction in the bacterial cell number by enhancing apoptotic processes, i.e., nucleus fragmentation, condensation of chromatin material, and abundancy in vacuole formation that may result in cell death. The underlying mechanism was the alteration in cell morphology after treatment with SLPs.11b

Considering the cytotoxic potency of laticifer proteins, it was investigated for the first time in our study that these proteases may play a vital role in the inhibition of viral proteins. In the current study, laticifer proteins, isolated from C. procera, were eventually tested against Newcastle disease virus (NDV). Second, these proteins were also analyzed for their toxicity effects. The objective of this study was to assess the toxicity profile of SLPs at a genetic level. According to the literature, laticifer proteins are pharmacologically active against cancerous diseases and also involved in controlling inflammatory disorders while there is a minimum set of data available for their genetic safety, i.e., oxidative DNA damage and mutagenicity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

All chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). A dialysis tube (Amicon Ultra-15 10K centrifugal filter device) was used for separating substances of smaller molecular weights. Chemicals for SDS–PAGE analysis include acrylamide, Bis-Acrylamide, 1.5 M Tris–HCl, Tris base, SDS, ammonium per sulfate solution, Coomassie Blue stain (R250), and glycine and glacial acetic acid. For antiviral activity, the following chemicals and reagents were used as antibiotic mixtures: LaSota vaccine (as virus source), amphotericin B, gentamycin, benzyl penicillin, and streptomycin. For cytotoxicity the following chemicals were employed: cell culture medium M-199, glass filtration assembly, trypsin, DMSO, fetal bovine serum, bicarbonate buffer, BHK-21 cell line, 0.22 μm syringe filter, MTT dye, and DMSO. For genotoxicity by Comet Assay, chemicals utilized were sodium chloride (NaCl), ethidium bromide, trizma base, methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), normal melting agarose, low melting agarose, disodium EDTA, phosphate buffer saline (PBS), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Triton X-100, lymphocyte separating medium, boric acid, and RPMI-1640. Chemicals required for AMES assay were nutrient broth, yeast extract, K2Cr2O7, sodium azide (NaN3), glucose, histidine, and histopaque.

2.2. Latex Collection and Protein Extraction

Healthy plants of C. procera, located in the vicinity of District Bahawal Nagar, Punjab, were used for collecting latex. The plant parts of C. procera were identified, and voucher no. 3658 was deposited at the Herbarium of Department of Botany, Government College University, Lahore, Pakistan. Latex was collected on 10 August 2019 from aerial parts of the plant in falcon tubes containing distilled water to give a dilution rate of 1:1 (v/v) and the mixture was gently agitated during collection in order to avoid the natural coagulation effects of latex. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C for each sample, and the supernatant was further processed in two ways; one portion of the supernatant was labeled with the name of RFL and another portion was further dialyzed so that small metabolites other than protein were exhaustively dialyzed in distilled water and it was labeled as SLP. Samples were prepared by centrifugation and lyophilization. The method was followed as described by various studies.18

2.3. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE)

Protein content in SLPs was evaluated by the nanodrop method at 280 nm in a UV visible spectrophotometer.19 Denaturing SDS-PAGE was executed according to previous studies for separating laticifer proteins.20 Samples of laticifer proteins were added into 4× sample buffer (3:1), and the mixture was incubated for 5 min at 95 °C to denature the proteins. Gels were prepared with 12% of acrylamide in Tris–HCl buffer (1.5 M, pH 8.8) and then run at 100 V for 2 h at room temperature. Coomassie brilliant blue staining was used in order to acquire a good definition of bands. Molecular weight was identified by comparing protein bands obtained after electrophoresis of the sample with known molecular weight prestained marker HiMark HMW protein standard (Invitrogen).

The relative molecular weight of the polypeptides of samples were calculated by plotting a standard curve between log molecular weight and Rf of known samples (ladder) for finding the molecular weight of laticifer proteins of the sample.

2.4. Newcastle Disease Virus

Newcastle disease virus was obtained after confirmation by Hem-agglutination inhibition test from Department of Microbiology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore. The protocol of the test was followed as given by previous studies.21 In Hem-agglutination assay (HA), 4HA activity of the test virus was determined (data is given in the Supporting Information).

2.5. Antiviral Activity

Two-fold serial dilutions starting from 10 mg/mL up to 0.019 mg/mL of both RFL and SLP incubated for 30 min at 37 °C after mixing with standard concentration of the virus in order to observe antiviral activity.22 The mixture was injected through an allantoic cavity route under sterilized conditions in 9 day old chicken embryos purchased from Big Bird Laboratories, Lahore. The positive control was set by injecting the virus alone in embryos while the negative control was prepared by injecting only PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) in the embryo. All embryos were incubated at 37 °C and 60% humidity. The livability of embryos was examined daily using an egg candler. Chorioallantoic fluid was collected in sterilized test tubes, and the presence of virus was examined by the spot hem-agglutination method.

2.6. Embryotoxicity

To observe embryotoxicity, the same concentrations of both extracts without virus were inoculated into chicken embryos as studied previously.23 The mortality of embryos caused by test samples was then recorded for the period of 72 h.

2.7. Cytotoxicity by MTT Assay

MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay developed by Mosmann was used to check the cytotoxic potential of RFL and SLP on the same test concentrations analyzed in previous assays.24 96-well cell cultured plates were used for seeding of BHK-21 cell lines in the form of a monolayer. Each test sample of 100 μL was poured in triplicate over the BHK-21 monolayer followed by incubation for 96 h at 37 °C. After incubation, MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, 0.5% solution (100 μL), was poured into each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. MTT dye was then replaced with 10% DMSO (100 μL) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The optical density (OD) was measured at 570 nm by a multiwell RT-2100C Microplate Reader (Rayto China).25 Cytotoxic potential of laticifer proteins was carefully estimated by the cell survival percentage (CSP) which was calculated as follows:

2.8. Genotoxicity

The alkaline comet assay was used to find the genotoxicity of RFL and SLP. Viable lymphocytes from human blood were separated with the help of Histopaque as described earlier.26 A pellet of lymphocytes was resuspended in RPMI-1640. 1 mL of test sample and 100 μL of cell suspension mixture were incubated in an inverted position for a period of 3 h and then centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 rpm. The lymphocyte pellet was again resuspended in RPMI-1640.

Cavity slides were coated with normal melting agarose. A mixture of treated lymphocytes and low melting point agarose (LMPA) were applied to cavity slides and placed in the refrigerator. Subsequently, a third layer of LMPA (90 μL) was applied on the slides and placed in the refrigerator for 5–10 min. Lysing solution was poured on the slides and placed in the refrigerator for 2–12 h. Then slides were passed through alkaline buffer solution for 20 min to unwind the damaged part of DNA. Electrophoresis was run on slides for 30 min at 24 V and the current was set at 300 mA. After electrophoresis, slides were exposed to neutralizing buffer for 5–10 min. The process was repeated 2–3 times. For staining purpose, the slides were exposed to ethidium bromide and immediately visualized under a fluorescent microscope for scoring them at 40× objective lenses. 1% DMSO was used as the negative control and 20% served as the positive control. The results were interpreted on the basis of tail length by applying formula given below.

2.9. Mutagenicity

Evaluation of the mutagenic properties of laticifer proteins of C. procera was completed by an AMES Salmonella/microsome mutagenicity assay.27 The histidine dependence of Salmonella strains was tested by exposing them to various doses of laticifer proteins, and the number of revertant colonies were counted. TA100 and TA98 strains of Salmonella typhimurium were used to carry out the AMES assay that was developed by Prof. B. N. Ames. Both bacterial strains (S. typhimurium) were kindly provided by Prof. B. N. Ames, Biochemistry Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA. Glycerol stocks of TA100 and TA98 strains of S. typhimurium were preserved at −80 °C. Bacteria were refreshed in nutrient broth, and pellets were obtained after centrifugation. Bacterial strains were checked for the presence of various genetic characters (Supplementary Table 1).

2-fold serial dilutions of each sample were prepared and tested individually. Mixtures of 1 mL of test samples of specific concentration, fresh culture (100 μL) of test strain (containing approximately 3 × 107 cells/mL), and 200 μL of histidine–biotin solution were taken in test tubes having top agar. These test tubes ware mixed on a vortex mixer for 3 s and poured onto VB minimal medium plates. Plates were set in an incubator at 37 °C for 72 h. Distilled water (100 μL) was used as the negative control, while sodium azide (10 μg per plate) for TA100 and potassium dichromate (10 μg per plate) for TA98 were used as the positive control (Supplementary Figure 1). The number of revertant colonies were counted, and if the revertant colonies were found to be 2-fold higher than the negative plate then the substance would be considered as mutagenic.28 The mutagenic index was calculated as follows:

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The raw data obtained for all experiments were analyzed by IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20, Inc., Chicago, IL) and expressed in terms of means ± SD where n was at least 3–5. If necessary, the data were transformed to log2, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) along with POST HOC Duncan’s test was applied to find statistical differences.

3. Results

3.1. Soluble Laticifer Protein from C. procera Showed Significant Antiviral Activity

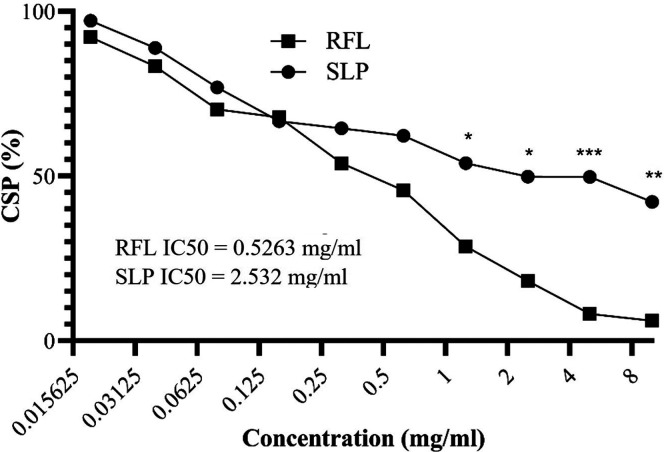

Rubber-free latex (RFL) was passed through the dialyzing membranes (10 kDa cut point) to obtain a more pure fraction of laticifer proteins which was named as soluble laticifer proteins (SLP). The SDS–PAGE analysis of RFL and SLP showed that it might consist of different proteins and most of them lie in the range of 20–30 kDa molecular weight (Figure 1). Subsequently, the antiviral activity of SLP of C. procera was examined against NDV using hemagglutination assay (HA). The chorioallantoic fluid from the chicken embryo was harvested to investigate the viral concentration. We found that the RFL obtained from the plant was significantly active against the virus. We have analyzed 10 different concentrations of RFL where most of them showed antiviral activity except for the low concentrations, i.e., 0.0195 and 0.39 mg/mL (Table 1). Likewise, SLP also showed the same results as were obtained for RFL (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

SDS–PAGE analysis of C. procera laticifer proteins (RFL and SLP).

Table 1. NDV Titer after Treatment with RFL and SLPa.

| RFL | SLP | |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/mL) | HA titer (mean ± SD) | HA titer (mean ± SD) |

| 10 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 5 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 2.5 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 1.25 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 0.625 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 0.312 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 0.156 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 0.078 | 0 ± 0.0c | 0 ± 0.0c |

| 0.039 | 3.6 ± 0.577b | 3.9 ± 0.547b |

| 0.019 | 4.6 ± 0.577b | 2.7 ± 0.257b |

| Positive control | 9 ± 0.0 | 9 ± 0.0 |

| Negative control | 0 ± 0.0 | 0 ± 0.0 |

The data are shown as mean ± SD and representative of 3–4 independent experiments. Comparison is made between positive control and concentrations where.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Antiviral activity of RFL and SLP obtained from C. procera.

RFL and SLP were analyzed by SDS–PAGE, and a few protein bands were visible after Coomassie blue staining. In the SLP lane most of the bands were visible at the range of 20–30 kDa while in the RFL lane mixed bands with low intensity were observed. A representative gel image is shown where M is the marker.

Ten different concentrations of RFL and SLP were examined for antiviral activity by the HA test that showed positive antiviral effects for both RFL and SLP except for the low concentrations, i.e., 0.0195 and 0.39 mg/mL, where they just reduced the titer.

3.2. Higher Doses of RFL and SLP Were Toxic to the Chicken Embryo

Some studies have shown that the laticifer proteins might be harmful to other organisms such as insect pests.29 Therefore, next we decided to investigate if our protein is toxic to the embryo or not. The toxicity profile of RFL and SLP was determined on the chicken embryo for different dose concentrations. It was found that on higher doses of RFL (10, 5, and 2.5 mg/mL) embryos died before completion of the assay (72 h) while in the case of SLP the two higher doses (10 and 5 mg/mL) were found to be lethal to the embryos (Table 2). So, it was observed that SLP is comparatively safer than RFL of C. procera as some of the toxic compounds might be sieved during the purification of soluble protein.

Table 2. Embryo Toxicity in Chicken Embryos after Treatment with RFL and SLP.

| Concentration (mg/mL) | RFL | SLP |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | dead | dead |

| 5 | dead | dead |

| 2.5 | dead | alive |

| 1.25 | alive | alive |

| 0.625 | alive | alive |

| 0.312 | alive | alive |

| 0.156 | alive | alive |

| 0.078 | alive | alive |

| 0.039 | alive | alive |

| 0.019 | alive | alive |

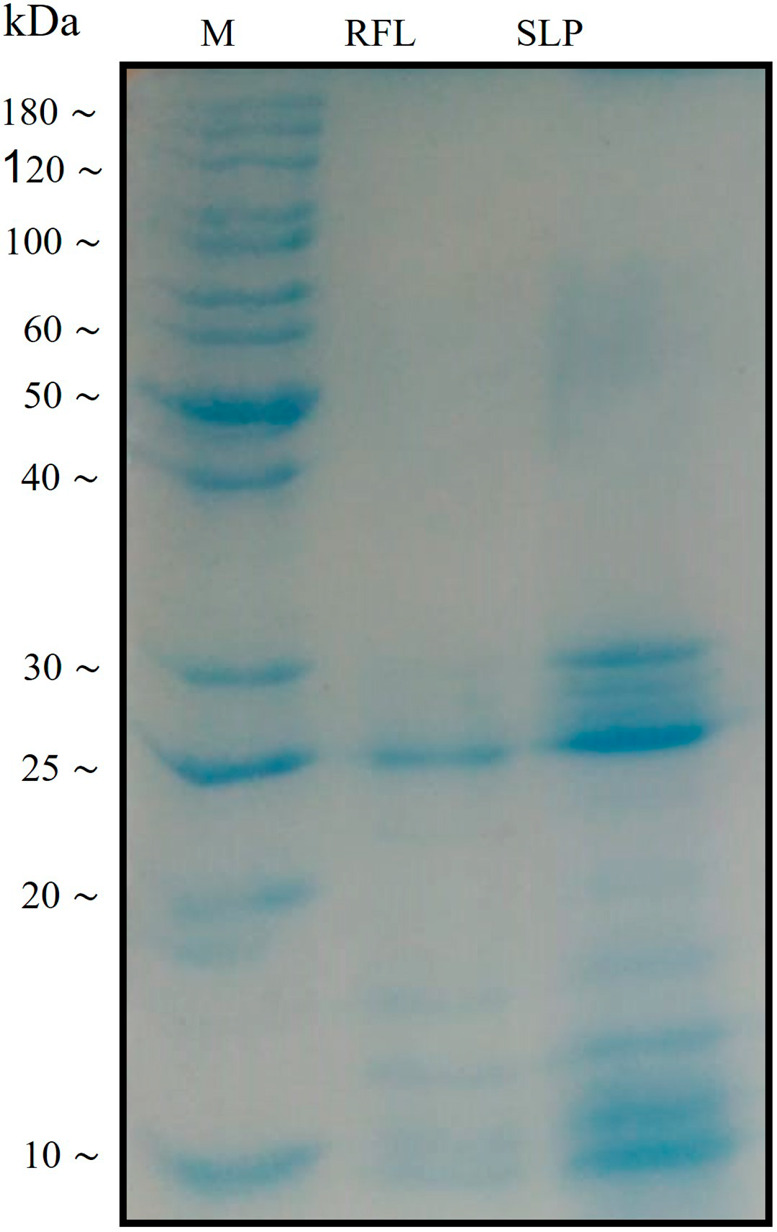

3.3. Higher Doses of RFL and SLP Decreased the Cell Survival Percentage

After determination of the embryo toxic effect of the RFL and SLP, we were interested in investigating the cytotoxic effects of these compounds. The cytotoxicity study was performed on the BHK-21 cell line (hamster kidney fibroblasts) by using an MTT assay. The results were interpreted by cell survival percentage (CSP) on the basis of optical density (OD) values. The results showed that RFL has significantly decreased the CSP (less than 50%) even at a 0.625 mg/mL dose (Figure 3). On the other hand, SLP showed a rather safe dose profile where only higher doses (10, 5, and 2.5 mg/mL) attenuated the CSP (less than 50%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cell survival percentage (CSP) of C. procera laticifer proteins on BHK-21 cell line.

It was confirmed after the cytotoxic analysis that SLP is quite safe as compared to RFL. However, the dose concentration should be critically monitored. SLP has a potential antiviral activity even at low doses; therefore, it can be used as an effective therapeutic agent against viral infections.

The MTT assay was performed to analyze the cell survival percentage of BHK-21 cells on various concentrations (10–0.019 mg/mL) of RFL and SLP. The concentration scale was taken as log2 of the original values. A statistical comparison is made between RFL and SLP’s CSP values at each concentration where * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

3.4. High Concentration of RFL and SLP Resulted in Genotoxicity

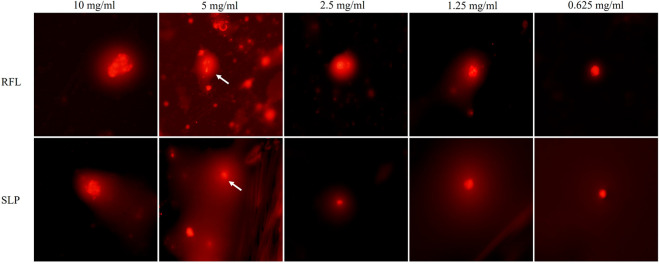

The above outcomes prompted us to investigate whether SLP also causes damage to the DNA of the target organism. Therefore, a genotoxic effect was observed on the freshly isolated human lymphocytes by using comet assay (single-cell gel electrophoresis). The genetic damage index (GDI) of RFL recorded at all doses fell almost in the same range (1.48–1.0) as shown in Table 3. By contrast, the GDI recorded for SLP at the highest concentration (i.e., 10 mg/mL) was 1.1 ± 0.25 μm and for the positive control (20% DMSO) it was 2.12 ± 0.34 μm. There was a gradual rise in the GDI values as the dose concentration increased from 0.019 to 0.625 mg/mL but from 0.625 to 10 mg/mL the GDI values remained constant (Table 4) indicating the genotoxicity is produced at higher doses. Moreover, in the case of SLP most of the cells were classified in class I damage and none was in class III damage, hence proving that SLP was found to be comparatively safe (Figure 4, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3. Mean Head and Tail Length of Damaged DNA and Genetic Damage index (GDI) after Treatment with RFLa.

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Mean head length of DNA (μm) | Mean tail length of DNA (μm) | Damage index | Genetic damage index (GDI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1.97 ± 0.54d | 1.53 ± 0.53d | 37 | 1.48 |

| 5 | 2.14 ± 0.64d | 1.24 ± 0.27d | 33 | 1.32 |

| 2.5 | 2.5 ± 0.30c | 0.98 ± 0.63c | 33 | 1.26 |

| 1.25 | 2.52 ± 0.63c | 0.51 ± 0.45c | 28 | 1.12 |

| 0.625 | 2.9 ± 0.42c | 0.5 ± 0.32c | 27 | 1.08 |

| 0.312 | 3.3 ± 0.41c | 0.48 ± 0.78c | 27 | 1.08 |

| 0.156 | 3.56 ± 0.58b | 0.38 ± 0.12b | 25 | 1 |

| 0.078 | 4.6 ± 0.85ns | 0.21 ± 0.27ns | 25 | 1 |

| 0.039 | 4.9 ± 0.26ns | 0.090 ± 0.75ns | 25 | 1 |

| 0.019 | 5.1 ± 0.56ns | 0. 09 ± 0.45ns | 25 | 1 |

| 20% DMSO (Positive control) | 0.76 ± 0.58 | 12 ± 0.34 | 55 | 2.2 |

| RPMI (Negative control) | 5.12 ± 0.23 | 0.18 ± 0.14 | 2 | 0.08 |

The data are shown as mean ± SD and representative of 3–5 independent experiments. Comparison is made between negative control and concentrations where.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001, ns = nonsignificant.

Table 4. Mean Head and Tail Length of Damaged DNA and Genetic Damage Index (GDI) after Treatment with SLPa.

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Mean head length of DNA (μm) | Mean tail length of DNA (μm) | Damage Index | Genetic Damage Index (GDI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2.4 ± 0.89c | 1.1 ± 0.25c | 26 | 1.04 |

| 5 | 2.1 ± 0.63c | 0.81 ± 0.51c | 25 | 1 |

| 2.5 | 2.3 ± 0.47c | 0. 67 ± 0.47c | 25 | 1 |

| 1.25 | 2.3 ± 0.29c | 0.45 ± 0.42c | 20 | 0.8 |

| 0.625 | 2.6 ± 0.56c | 0.42 ± 0.27c | 16 | 0.64 |

| 0.312 | 3.1 ± 0.95c | 0.40 ± 0.75c | 14 | 0.56 |

| 0.156 | 2.9 ± 0.79c | 0.38 ± 0.57c | 11 | 0.44 |

| 0.078 | 3.1 ± 0.53c | 0.09 ± 0.49ns | 9 | 0.36 |

| 0.039 | 3.3 ± 0.87b | 0.120 ± 39ns | 10 | 0.4 |

| 0.019 | 3.7 ± 0.23b | 0. 06 ± 0.71ns | 7 | 0.28 |

| 20%DMSO (Positive control) | 0.76 ± 0.58 | 12 ± 0.34 | 53 | 2.12 |

| RPMI (Negative control) | 5.12 ± 0.23 | 0.18 ± 0.14 | 2 | 0.08 |

The data are shown as mean ± SD and representative of 3–5 independent experiments. Comparison is made between negative control and concentrations where.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01, ns = nonsignificant.

Figure 4.

Genotoxicity evaluation by comet assay for C. procera laticifer proteins.

Freshly isolated human lymphocytes were used for the evaluation of genotoxicity by performing comet assay. The results are given in form of representative fluorescent microscope images of comet assay for different doses (10–0.019 mg/mL) of RFL and SLP.

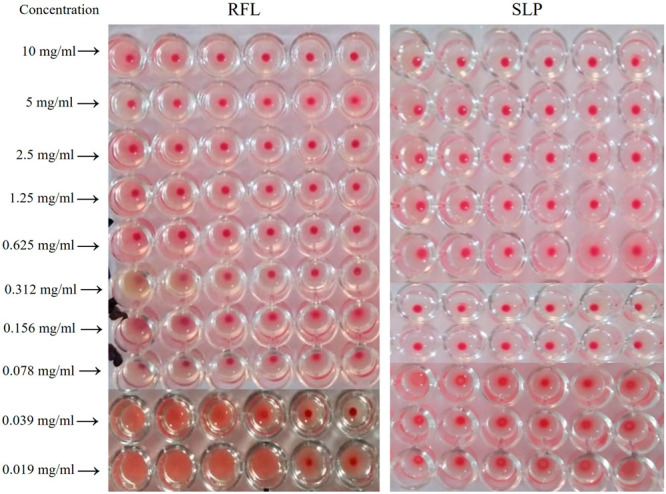

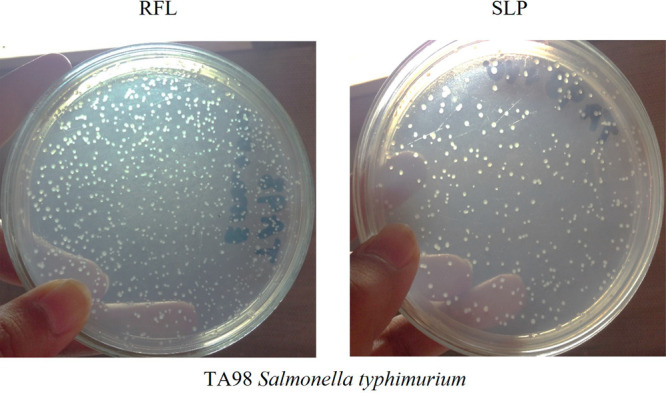

3.5. Higher Doses of RFL and SLP Caused Mutagenesis

Previously, some studies have reported the mutagenic effect of latex of C. procera.30 This impelled us to also investigate the mutagenic potential of our extracted protein from the latex of C. procera, SLP. Both RFL and SLP were analyzed for their mutagenic effect on Salmonella typhimurium TA98 and TA100. It was observed that both were highly mutagenic predominantly at high doses (Tables 5 and 6). However, SLP showed a little less mutagenic effect as compared to RFL (Figure 5)

Table 5. Mutagenicity for Different Concentrations of RFLa.

| TA98 |

TA100 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Revertant colonies (Mean ± SD) | Mutagenic Index (M.I) | Revertant colonies (Mean ± SD) | Mutagenic Index (M.I) |

| 5 | 579 ± 7c | 2.93 | 595 ± 5c | 2.97 |

| 2.5 | 558 ± 5c | 2.83 | 592 ± 7c | 2.93 |

| 1.25 | 501 ± 9.5c | 2.54 | 580 ± 10b | 2.6 |

| 0.625 | 387 ± 5b | 1.95 | 289 ± 9.5b | 1.43 |

| 0.312 | 223 ± 8ns | 1.96 | 283 ± 8b | 1.43 |

| 0.156 | 190 ± 15ns | 0.96 | 194 ± 8.5ns | 0.98 |

| Positive control | 520 ± 5 | 2.63 | 500 ± 5 | 2.53 |

| Negative Control | 197 ± 7 | 197 ± 7 | ||

Ames mutagenicity test, showed as number of revertant colonies per plate and mutagenic index. Mutagenicity was tested on two strains of Salmonella typhimurium (TA98 & TA100). The data are shown as mean ± SD and representative of 3–5 independent experiments. Comparison is made between negative control and concentrations where.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001, ns = nonsignificant.

Table 6. Mutagenicity for Different Concentrations of SLPa.

| TA98 |

TA100 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/mL) | Revertant colonies (Mean ± SD) | Mutagenic index (M.I) | Revertant colonies (Mean ± SD) | Mutagenic index (MI) |

| 5 | 447 ± 7b | 2.26 | 501 ± 8ns | 2.45 |

| 2.5 | 422 ± 5b | 2.14 | 456 ± 10ns | 2.23 |

| 1.25 | 409 ± 9c | 2.07 | 437 ± 12ns | 2.14 |

| 0.625 | 385 ± 5c | 1.95 | 168 ± 5c | 0.82 |

| 0.312 | 290 ± 8c | 1.47 | 189 ± 5c | 0.92 |

| 0.156 | 198 ± 5c | 1.005 | 298 ± 8c | 1.46 |

| Positive control | 520 ± 5 | 2.63 | 457 ± 6 | 2.24 |

| Negative Control | 197 ± 7 | 204 ± 6 | ||

Ames mutagenicity test, showed as number of revertant colonies per plate and mutagenic index. Mutagenicity was tested on two strains of Salmonella typhimurium (TA98 and TA100). The data are shown as mean ± SD and representative of 3–5 independent experiments. Comparison is made between negative control and concentrations of SLP where

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01, ns = nonsignificant.

Figure 5.

Revertant colonies of Salmonella typhimurium TA98 with C. procera laticifer proteins (RFL and SLP).

S. typhimurium TA98 revertant colonies were visible at doses 10, 5, and 2.5 mg/mL. Representative images are shown for SLP and RFL at 10 mg/mL dose.

4. Discussion

Most of the human population all around the world is consuming traditional herbal medicinal products for the cure of a number of ailments. Herbal medicines are preferred over synthetic drugs as they have fewer side effects. However, the toxicity analysis of the herbal medicinal products is still an under-researched area. We demonstrated here not only the antiviral activity of the soluble laticifer proteins (SLP), obtained from C. procera, but also the toxicity effects of SLP. To our knowledge, this study has provided the evidence for the first time that SLPs are toxic at higher doses.

The RFL and SLP were collected and purified from C. procera, a plant commonly found in the south Punjab part of Pakistan. RFL was obtained by removal of the toxic rubber part through centrifugation, and SLP was obtained by further passing it through the dialyzing membrane where the small molecular weight proteins/metabolites were washed out. Hence, SLP was a purified protein content of C. procera, which was confirmed by SDS–PAGE analysis. Subsequently, the RFL and SLP analyses against Newcastle disease virus showed a significant reduction in the virus titer in a dose-dependent manner. The Newcastle disease is a highly endemic and lethal viral disease of birds especially in developing countries.31 There is no specific treatment available for NDV; the only option is vaccination which just reduces the chances of occurrence but does not cure the disease completely.32 We have analyzed RFL and SLP on chicken embryos for antiviral activity, and both were found active even at the lowest tested doses. The antiviral activity of SLP was determined on all its dilutions starting from 10 mg/mL but on 0.039 and 0.0195 mg/mL reduction in the virus titer was confirmed by the HA test.

The latex of C. procera has been reported to possess toxic potential which might be due to the presence of a number of alkaloids.1 Latex also contains cysteine rich proteases that are active in the plant’s own defense mechanism against herbivorous insects. These cysteine proteases might also cause toxicity to the mammalian hosts.33 Besides the antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor activities, latex proteins also showed the toxicity to the host organism. Therefore, as a next step, RFL and SLP were analyzed for their toxic effects on chicken embryos, where they have been shown to possess the embryo toxic effect at higher tested doses, i.e., 2.5 mg/mL and above. Moreover, it was determined that SLP have less toxic effect as compared to the RFL. SLP was found embryotoxic at 10 and 5 mg/mL while on all other doses embryos were found alive.

As RFL and SLP were found to be toxic on embryos, we further explored toxicity profile of these laticifer proteins including cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and mutagenesis. Cytotoxic potential of both RFL and SLP were evaluated on the BHK-21 cell line for the same set of concentrations using 20% DMSO as negative control. RFL was found cytotoxic at highest concentration (i.e., 10 mg/mL) but as the dose was reduced, CSP was gradually increased. These results were in line with another study conducted on dried latex and flower extract of C. procera on MCF-7 and HeLa cell lines.34 Of note, the CSP at highest concentration of SLP (i.e., 10 mg/mL) was 42.18 that was much safer than RFL at the same dose. CSP was gradually elevated as dose was reduced and it was more than 50% at 2.5 mg/mL. Similarly in another study, CSP of laticifer proteins were determined on peripheral blood mononuclear cells and laticifer proteins showed no obvious effects on the viability of cells at 0.01 mg/mL for 72 h.11a

Although the dialyzing process has recued the number of toxic metabolites in SLP, but the dose concentration needs to be properly adjusted. Similar results were obtained when the genotoxic activity of laticifer proteins was elucidated. It has been previously reported that laticifer proteins may involve genotoxicity by changing the topology of DNA.11a In line with these reports, RFL and SLP in our study indicated DNA damage at higher doses. The DNA damage was identified by comet assay performed on freshly isolated human lymphocytes. Comet assay is a well-established, sensitive and rapid test to determine genotoxicity which displays the breakage in any of the DNA strand in a shape similar to comet.35 However, to complete and confirm the information established in these in vitro analyses, the in vivo studies will further help to assess the toxicity level of these laticifer proteins.

Genetic mutation, another type of DNA damage32,36 was also observed in case of RFL and SLP. Some studies have determined that latex of the plants can cause irreversible damage to the cells.37 Genetic mutation was determined by performing the Ames test, which is a bacterial reverse mutation assay.38 The two bacterial strains TA98 and TA100 of Salmonella typhimurium were used to analyze the mutation caused by these laticifer proteins. RFL and SLP displayed the similar pattern of mutagenic activity as they have shown for other toxicity tests.

Keeping in view the rise in resistance among currently available chemotherapeutic agents, we have analyzed the bioactive compounds (laticifer proteins) for their antiviral activity. We found that RFL and SLP obtained from C. procera have a potential antiviral activity, but on the other hand they also possess significant toxicity including embryotoxicity, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and mutagenicity, which were observed at high doses of both RFL and SLP. However, lower concentrations were found to be safe and significantly effective against virus. Therefore, we suggest that SLP can be used against infectious diseases because it is rather safe, more therapeutically active, and less toxic as compared to RFL. However, while using these proteins as antiviral agents the dose should be critically monitored. Moreover, designing in vivo experiments against other viral diseases is suggested for testing the antiviral potential of SLP.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SLPs

soluble laticifer proteins

- RFL

rubber free latex

- NDV

Newcastle disease virus

- BHK-21

cell lines baby hamster kidney cell lines

- HA

hem-agglutination assay

- Rf

relative flow

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- CSP

cell survival percentage

- OD

optical density

- LMPA

low melting point agarose

- GDI

genetic damage index

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- GFC

gel filtration chromatography

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c08102.

Materials and methods including 4HA virus determination; materials and chemicals for cell culture for BHK-21 cells; collection of lymphocytes for genotoxicity assay; identification of genetic characteristics of bacterial strains in AMES assay; Table S1, genetic characteristics of test strains TA98 and TA100; Table S2, genetic damage index of DNA in comet assay after treatment with RFL; Table S3, genetic damage index of DNA in comet assay after treatment with SLP; Figure S1, salmonella/microsome mutagenicity test (Ames test) (PDF)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.S. and M.O.O.; methodology, U.S., M.O.O., A.J., A.A.A., A.M., and G.S.; formal analysis, U.S.; writing—original draft preparation, U.S., K.R., and T.A.; writing—review and editing M.O.O., and K.R. All authors have thoroughly read and reviewed the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Basak S. K.; Bhaumik A.; Mohanta A.; Singhal P. Ocular toxicity by latex of Calotropis procera (Sodom apple). Indian J. Ophthalmol 2009, 57 (3), 232. 10.4103/0301-4738.49402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanzada S. K.; Shaikh W.; Kazi T.; Sofia S.; Kabir A.; Usmanghani K.; Kandhro A. A. Analysis of fatty acid, elemental and total protein of Calotropis procera medicinal plant from Sindh, Pakistan. Pak J. Bot 2008, 40 (5), 1913–1921. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed A. E.-D. H.; Mohamed N. H.; Ismail M. A.; Abdel-Mageed W. M.; Shoreit A. A.M. Antioxidant and antiapoptotic activities of Calotropis procera latex on Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) exposed to toxic 4-nonylphenol. Ecotoxicol Environ. Saf 2016, 128, 189–94. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed M. A.; Hamed M. M.; Ahmed W. S.; Abdou A. M. Antioxidant and cytotoxic flavonols from Calotropis procera. Z. Naturforsch C J. Biosci 2011, 66 (11–12), 547–54. 10.1515/znc-2011-11-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awaad A. A.; Alkanhal H. F.; El-Meligy R. M.; Zain G. M.; Sesh Adri V. D.; Hassan D. A.; Alqasoumi S. I. Anti-ulcerative colitis activity of Calotropis procera Linn. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26 (1), 75–78. 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z.; Lateef M.; Jabbar A.; Muhammad G.; Khan M. N. Anthelmintic activity of Calotropis procera (Ait.) Ait. F. flowers in sheep. J. Ethnopharmacol 2005, 102 (2), 256–61. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani H. S.; Mutwakil M. H. Z.; Sabir J. S. M.; Saini K. S.; Alarif W. M.; Rizgallah M. R. Anticancer and Antibacterial Activity of Calotropis procera Leaf Extract. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2017, 7 (12), 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed N. H.; Liu M.; Abdel-Mageed W. M.; Alwahibi L. H.; Dai H.; Ismail M. A.; Badr G.; Quinn R. J.; Liu X.; Zhang L.; Shoreit A. A. M. Cytotoxic cardenolides from the latex of Calotropis procera. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25 (20), 4615–4620. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alencar N.; Oliveira J.; Mesquita R.; Lima M.; Vale M.; Etchells J.; Freitas C.; Ramos M. Pro-and anti-inflammatory activities of the latex from Calotropis procera (Ait.) R., Br. are triggered by compounds fractionated by dialysis. Inflamm Res. 2006, 55 (12), 559–564. 10.1007/s00011-006-6025-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M. V.; Viana C. A.; Silva A. F.; Freitas C. D.; Figueiredo I. S.; Oliveira R. S.; Alencar N. M.; Lima-Filho J. V.; Kumar V. L. Proteins derived from latex of C. procera maintain coagulation homeostasis in septic mice and exhibit thrombin- and plasmin-like activities. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2012, 385 (5), 455–63. 10.1007/s00210-012-0733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Soares de Oliveira J.; Pereira Bezerra D.; Teixeira de Freitas C. D.; Delano Barreto Marinho Filho J.; Odorico de Moraes M.; Pessoa C.; Costa-Lotufo L. V.; Ramos M. V. In vitro cytotoxicity against different human cancer cell lines of laticifer proteins of Calotropis procera (Ait.) R. Br. Toxicol In Vitro 2007, 21 (8), 1563–1573. 10.1016/j.tiv.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Oliveira J. S.; Costa-Lotufo L. V.; Bezerra D. P.; Alencar N. M.; Marinho-Filho J. D.; Figueiredo I. S.; Moraes M. O.; Pessoa C.; Alves A. P.; Ramos M. V. In vivo growth inhibition of sarcoma 180 by latex proteins from Calotropis procera. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2010, 382 (2), 139–49. 10.1007/s00210-010-0525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-H. - A Simple Outline of Methods for Protein Isolation and Purification. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2017, 32 (1), 18–22. 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdulkadir A.; Umar I. A.; Ibrahim S.; Onyike E.; Kabiru A. Y. Cysteine Protease Inhibitors from Calotropis procera with Antiplasmodial Potential in Mice. J. Adv. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 1–13. 10.9734/JAMPS/2016/22866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares L. S.; Ralph M. T.; Batista J. E. C.; Sales A. C.; Ferreira L. C. A.; Usman U. A.; da Silva Júnior V. A.; Ramos M. V.; Lima-Filho J. V. Perspectives for the use of latex peptidases from Calotropis procera for control of inflammation derived from Salmonella infections. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 171, 37–43. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.12.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas C. D. T.; Oliveira J. S.; Miranda M. R. A.; Macedo N. M. R.; Sales M. P.; Villas-Boas L. A.; Ramos M. V. Enzymatic activities and protein profile of latex from Calotropis procera. Plant Physiol Biochem 2007, 45 (10–11), 781–789. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska E.; Baraniak B.; Karaś M. Identification of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory peptides obtained by simulated gastrointestinal digestion of three edible insects species (Gryllodes sigillatus, Tenebrio molitor, Schistocerca gragaria). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53 (11), 2542–2551. 10.1111/ijfs.13848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa B. F.; Silva A.; Lima-Filho J. V.; Agostinho A. G.; Oliveira D. N.; de Alencar N. M. N.; de Freitas C. D. T.; Ramos M. V. Latex proteins downregulate inflammation and restores blood-coagulation homeostasis in acute Salmonella infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200458 10.1590/0074-02760200458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a de Oliveira K. A.; Gomes M. D. M.; Vasconcelos R. P.; de Abreu E. S.; Fortunato R. S.; Loureiro A. C. C.; Coelho-de-Souza A. N.; de Oliveira R. S. B.; de Freitas C. D. T.; Ramos M. V. Phytomodulatory proteins promote inhibition of hepatic glucose production and favor glycemic control via the AMPK pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 109, 2342–2347. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ruqaya Mohammed Al-ezzy; Asmaa Sabah Ahmaed; Nidhal Mohammed Saleh; Shaymaa Hameed Al-Obaidy Assessing the antiumer and anti-inflammatory potentials of Calotropis procera latex. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2021, 4, 086–091. 10.30574/ijsra.2021.4.1.0183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins P.; Hansen J. B.; Allen M. Microvolume protein concentration determination using the NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer. J. Vis Exp 2009, (33), 1610. 10.3791/1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizani D.; Motta A. S.; Morrissy J. A.; Terra R.; Souto A. A.; Brandelli A. Antibacterial activity of cerein 8A, a bacteriocin-like peptide produced by Bacillus cereus. Int. Microbiol 2005, 8 (2), 125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. C. Hemagglutination-inhibition test for avian influenza virus subtype identification and the detection and quantitation of serum antibodies to the avian influenza virus. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1161, 11–25. 10.1007/978-1-4939-0758-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.-H.; Kwon B.-E.; Jang H.; Kang H.; Cho S.; Park K.; Ko H.-J.; Kim H. Antiviral activity of chrysin derivatives against coxsackievirus B3 in vitro and in vivo. Biomol Ther 2015, 23 (5), 465. 10.4062/biomolther.2015.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M.; Li S.; Tan H. Y.; Wang N.; Tsao S.-W.; Feng Y. Current status of herbal medicines in chronic liver disease therapy: the biological effects, molecular targets and future prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16 (12), 28705–28745. 10.3390/ijms161226126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge M.; Zhang W.; Shi G.; Xiao C.; Zhao X.; Zhang R. Astragalus polysaccharide perseveres Cytomembrane capacity against Newcastle disease virus infection. Pak Vet J. 2015, 35 (3), 382–4. [Google Scholar]

- Harne S.; Sharma A.; Dhaygude M.; Joglekar S.; Kodam K.; Hudlikar M. Novel route for rapid biosynthesis of copper nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Calotropis procera L. latex and their cytotoxicity on tumor cells. Colloids Surf., B 2012, 95, 284–288. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar M. F.; Ashraf M.; Anjum A. A.; Javeed A.; Sharif A.; Saleem A.; Akhtar B. Textile industrial effluent induces mutagenicity and oxidative DNA damage and exploits oxidative stress biomarkers in rats. Environ. Toxicol Pharmacol 2016, 41, 180–186. 10.1016/j.etap.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay U.; Gupta S.; Mathur P.; Suravajhala P.; Bhatnagar P. Microbial Mutagenicity Assay: Ames Test. Bio Protoc 2018, 8 (6), 20. 10.21769/BioProtoc.2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames B. N.; McCann J.; Yamasaki E. Methods for detecting carcinogens and mutagens with the Salmonella/mammalian-microsome mutagenicity test. Mutat. Res. 1975, 31 (6), 347–64. 10.1016/0165-1161(75)90046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M. V.; Freitas C. D. T.; Stanisçuaski F.; Macedo L. L. P.; Sales M. P.; Sousa D. P.; Carlini C. R. Performance of distinct crop pests reared on diets enriched with latex proteins from Calotropis procera: Role of laticifer proteins in plant defense. Plant Science 2007, 173 (3), 349–357. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qari S. H. Molecular and biochemical evaluation of genetic effect of Calotropis procera (Ait.) latex on Aspergillus terreus (Thom). Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 46 (10), 725–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganar K.; Das M.; Sinha S.; Kumar S. Newcastle disease virus: current status and our understanding. Virus Res. 2014, 184, 71–81. 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo M.; Baudoux T.; Stévigny C.; Nortier J.; Colet J.-M.; Efferth T.; Qu F.; Zhou J.; Chan K.; Shaw D.; Pelkonen O.; Duez P. Review of current and “omics” methods for assessing the toxicity (genotoxicity, teratogenicity and nephrotoxicity) of herbal medicines and mushrooms. J. Ethnopharmacol 2012, 140 (3), 492–512. 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Musidlak O.; Bałdysz S.; Krakowiak M.; Nawrot R., Chapter Three - Plant latex proteins and their functions. In Advances in Botanical Research; Nawrot R., Ed.; Academic Press: 2020; Vol. 93, pp 55–97;. [Google Scholar]; b Konno K.; Hirayama C.; Nakamura M.; Tateishi K.; Tamura Y.; Hattori M.; Kohno K. Papain protects papaya trees from herbivorous insects: role of cysteine proteases in latex. Plant J. 2004, 37 (3), 370–8. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit P. M.; Krishna M.; Silpa P.; Nagalakshmi V.; Anjali M.; Girish K.; Chowdary Y. In vitro cytotoxic activities of Calotropis procera latex and flower extracts against MCF-7 and HeLa cell line cultures. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- a Verschaeve L.; Juutilainen J.; Lagroye I.; Miyakoshi J.; Saunders R.; de Seze R.; Tenforde T.; van Rongen E.; Veyret B.; Xu Z. In vitro and in vivo genotoxicity of radiofrequency fields. Mutat. Res. 2010, 705 (3), 252–68. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Santos D. B.; Schiar V. P.; Ribeiro M. C.; Schwab R. S.; Meinerz D. F.; Allebrandt J.; Rocha J. B.; Nogueira C. W.; Aschner M.; Barbosa N. B. Genotoxicity of organoselenium compounds in human leukocytes in vitro. Mutat. Res. 2009, 676 (1–2), 21–6. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakarov S.; Petkova R.; Russev G.; Zhelev N. DNA damage and mutation. Types of DNA damage. Biodiscovery 2014, 11, 1. 10.7750/BioDiscovery.2014.12.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Moura D. F.; Rocha T. A.; Barros D. M.; da Silva M. M.; de Lira M.; Dos Santos Souza T. G.; da Silva C. J. A.; de Aguiar Júnior F. C. A.; Chagas C. A.; da Silva Santos N. P.; de Souza I. A.; Araújo R. M.; Ximenes R. M.; Martins R. D.; da Silva M. V. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity, oral toxicity, genotoxicity, and mutagenicity of the latex extracted from Himatanthus drasticus (Mart.) Plumel (Apocynaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol 2020, 253, 112567. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames B. N.; Knudsen I.. Genetic Toxicology of the Diet. Proceedings of a satellite symposium of the Fourth International Conference on Environmental Mutagens; A. R. Liss, 1986; p 3. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.