SUMMARY

Gene regulatory divergence between species can result from cis-acting local changes to regulatory element DNA sequences or global trans-acting changes to the regulatory environment. Understanding how these mechanisms drive regulatory evolution has been limited by challenges in identifying trans-acting changes. We present a comprehensive approach to directly identify cis- and trans-divergent regulatory elements between human and rhesus macaque lymphoblastoid cells using ATAC-STARR-seq. In addition to thousands of cis changes, we discover an unexpected number (~10,000) of trans changes and show that cis and trans elements exhibit distinct patterns of sequence divergence and function. We further identify differentially expressed transcription factors that underlie >50% of trans differences and trace how cis changes can produce cascades of trans changes. Overall, we find that most divergent elements (67%) experienced changes in both cis and trans, revealing a substantial role for trans divergence—alone and together with cis changes—to regulatory differences between species.

Keywords: Gene Regulation, DNA Regulatory Elements, Human Evolution, Comparative Genomics, Functional Genomics, Massively Parallel Reporter Assays, Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines

INTRODUCTION

Phenotypic divergence between closely related species is driven primarily by non-coding mutations that alter gene expression, rather than protein structure or function.1–7 Gene expression changes can result from divergence in 1) cis, where DNA mutations alter local regulatory element activity, or 2) trans, where changes alter the abundance or activity of transcriptional regulators.8,9 These two modes of change have different mechanisms and scopes of effects on gene expression outputs. Each cis change influences a single regulatory element and its immediate local targets, while a trans change globally influences many regulatory elements and their gene targets. Thus, determining the respective contributions of cis versus trans changes to between-species gene expression differences is key to understanding the mechanisms that generate phenotypic divergence. Furthermore, because gene regulatory variants in humans are often associated with disease phenotypes, understanding these mechanisms will facilitate interpretation of genetic variation on disease.

Cis and trans changes are difficult to study independently because cellular environment and genomic sequence are inherently linked within endogenous settings. Previous studies have developed different approaches largely focused on gene expression levels to attempt to disentangle cis and trans mechanisms of gene regulatory evolution.8,10–28 Overall, these studies have yielded a complex picture of the roles of cis and trans changes in different settings, but they generally argue that cis changes drive most divergence in gene expression between closely-related species.

Gene expression is driven by regulatory element activity; thus, to gain a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying gene regulatory evolution, it is necessary to investigate cis and trans changes at the regulatory element level. To directly identify cis differences, several recent studies have compared the regulatory activity of homologous sequences between closely related species within a common cellular environment.29–32 By controlling the cellular environment, the regulatory element activity differences identified by these studies must be the result of changes in cis (i.e., sequence).

In contrast, only a handful of studies have directly tested the contributions of trans changes to regulatory element activity between species by comparing regulatory activity of the same sequences across species-specific cellular environments.33–35 Collectively, these studies conclude that trans changes to regulatory element function occur less frequently than cis changes and suggest that cis-variation primarily drives divergent regulatory element activity between closely related species.36 One recent study comparing regulatory element activity in human and mouse embryonic stem cells reported ~70% of activity differences were due to changes in cis.34 However, this study considered small (~1,600), pre-selected subsets of regulatory elements, and as a result, a comprehensive and unbiased survey of cis and trans contributions to global gene regulatory divergence remains a key gap in understanding mechanisms of gene regulatory evolution.

In this study, we develop a comparative ATAC-STARR-seq framework to comprehensively dissect cis and trans contributions to regulatory element divergence between species. ATAC-STARR-seq captures almost all chromatin accessible DNA fragments and assays them for regulatory activity. Because we create a reporter plasmid library separate from performing the reporter assay, our approach decouples sequence from cellular environment. Thus, sequences from a species of interest can be tested for activity within any chosen cellular environment. This allows us to systematically measure the effect of homologous sequence differences while controlling the cellular environment and vice versa.

Our approach expands the scope of analysis from a few thousand regulatory elements to ~100,000 regulatory elements genome-wide without the need for prior knowledge of regulatory potential.37,38 Applying ATAC-STARR-seq to human and rhesus macaque lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs), we discover that cis and trans changes contribute to regulatory elements with divergent activity at similar frequencies, which contrasts with previous smaller studies that found cis changes drive most gene regulatory variation between species. We show that cis divergent elements are enriched for accelerated substitution rates and variants that influence gene expression in human populations, while trans divergent elements are enriched for footprints of differentially expressed transcription factors (TFs) that affect multiple gene regulatory loci. Furthermore, we find that the activity of most species-specific regulatory elements diverged in both cis and trans between human and macaque LCLs. These cis & trans regions are characterized by enrichment for specific transposable element sub-families harboring distinct TF binding footprints in humans. Finally, we illustrate how knowledge of mechanisms of regulatory divergence enriches interpretation of human variation and gene regulatory networks. By leveraging new technology to evaluate mechanisms of regulatory element divergence genome-wide, our study highlights the interplay between cis and trans changes on gene regulation and reveals a central role for trans-regulatory divergence in driving gene regulatory evolution.

RESULTS

Comparative ATAC-STARR-seq produces a multi-layered view of human and macaque gene regulatory divergence

We applied ATAC-STARR-seq37 to assay the regulatory landscape of LCLs between humans and macaques39–41 (GM12878 vs. LCL8664; Figure 1A,B). ATAC-STARR-seq enables genome-wide measurement of chromatin accessibility, TF occupancy, and regulatory element activity, which is the ability of a DNA sequence to drive transcription (Figure 1, S1). For each experimental condition, we performed three replicates and obtained both reporter RNA and successfully transfected plasmid DNA samples for each replicate. In all conditions, DNA input libraries were highly complex with estimated sizes ranging between 31–54 million DNA sequences (Figure S1A). Both reporter RNA and plasmid DNA sequencing data were reproducible across the three replicates (Figure S1B; Pearson r2: 0.97–0.99).

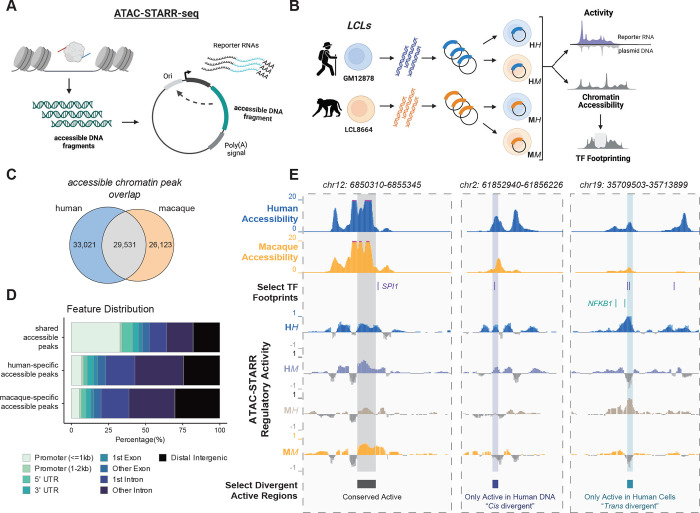

Figure 1: Comparative ATAC-STARR-seq produces a multi-layered view of human and macaque gene regulatory divergence.

(A) A schematic of the ATAC-STARR-seq methodology. Accessible DNA fragments are isolated from cells and subsequently cloned into a self-transcribing reporter vector plasmid, which are then electroporated into cells and assayed for regulatory activity by harvesting and sequencing Reporter RNAs and input plasmid DNA. (B) Our comparative ATAC-STARR-seq strategy to assay human and macaque genomes in both cellular environments. ATAC-STARR-seq plasmid libraries were independently generated for GM12878 and LCL8664 cell lines and then assayed separately in either cellular context. Our comparative approach provides measures in chromatin accessibility and transcription factor (TF) footprinting for both genomes as well as regulatory activity for the four experimental conditions: human DNA in human cells (HH), human DNA in macaque cells (HM), macaque DNA in human cells (MH) and macaque DNA in macaque cells (MM). (C) Euler plot representing the number of species-specific and shared accessibility peaks identified from ATAC-STARR-seq data. (D) Distribution of genomic annotations for species-specific and shared accessibility peaks based on the distance to nearest transcription start site. (E) Select genomic loci at hg38 coordinates representing conserved or differentially active regions of the two genomes. Tracks represent human and rhesus macaque accessibility, TF footprints for SPI1 and NFKB1, and regulatory activity measures for HH, HM, MH, MM. See also Figure S1.

We first determined accessibility peaks using the sequence reads obtained from the input DNA libraries, as previously described.37 Previous studies have investigated regions of differential chromatin accessibility in primate LCLs and other tissues,42–45 and consistent with these results, most chromatin accessibility peaks identified between the human and macaque genomes (59,144, 67%) is species-specific, while 29,531 (33%) peaks had shared accessibility between species (Figure 1C). As expected, we find that divergent accessibility peaks are distally located and enriched for cell-type relevant functions (Figure 1D, S1C–G).

Pinpointing the mechanisms underlying divergent activity requires that regulatory element DNA be captured from and tested in both species. Therefore, we analyzed shared accessible chromatin peaks so that both the human and macaque homologs were assayed. We quantified regulatory activity in four conditions: human DNA in human cells (HH), human DNA in macaque cells (HM), macaque DNA in human cells (MH), and macaque DNA in macaque cells (MM) (Figure 1B). By comparing activity levels of orthologous sequences in these four settings, we can dissect whether cis changes, trans changes, or both have occurred in every single element tested. Altogether, this produces an integrated, high-resolution quantification of accessibility, TF occupancy, and regulatory activity at both conserved and divergent regulatory elements between human and macaque LCLs (Figure 1E).

Unlike in differential RNA expression analysis, it was necessary to both identify regions of interest and estimate their activity prior to any condition-specific comparison. To do this, we divided the 29,531 shared accessible peaks into sliding bins and retained bins with 1:1 orthology between human and macaque. We called activity for each bin using replicates to determine p-values for activity in each condition and collapsed overlapping bins with consistent activity. This yielded a set of robust active regions for each condition (Figure S2A,B, Methods). Next, we directly compared active regions between the four conditions. We used a rank-based comparison scheme to account for power differences that would affect significance thresholds, assuming that each condition has similar numbers of active regions within shared accessible chromatin. We compared results at several rank thresholds corresponding to different false discovery rate (FDR) thresholds and we observed similar patterns in the divergent activity calls between conditions at all thresholds considered (Figure S2C,D). Thus, we focus in the main text on a rank threshold of 10,000 active regions per condition corresponding to an FDR range of 0.026–0.11. The condition-specific regions were similarly distributed across the genome, with marginal differences in genomic feature content (Figure 2A).

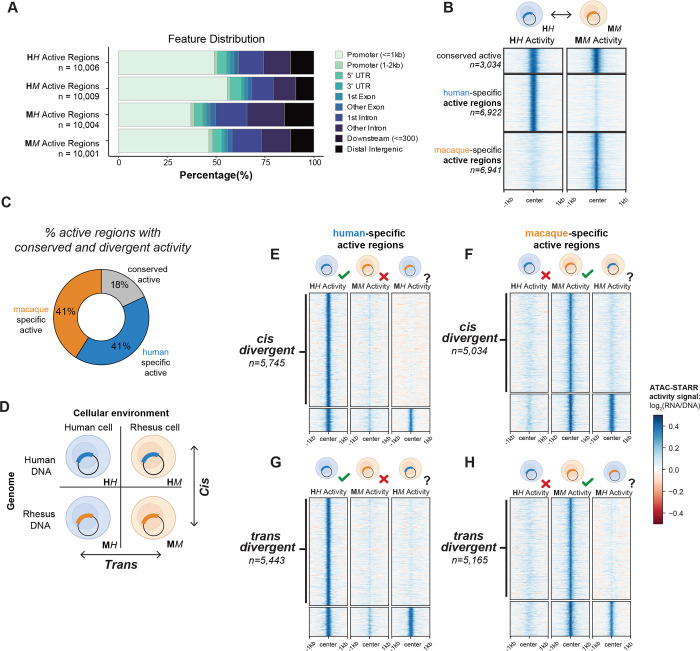

Figure 2: Cis and trans gene regulatory divergence occur at similar frequencies.

(A) Distribution of genomic annotations for the ~10,000 active regions called in each condition based on the distance to nearest transcription start site. (B) Comparison between the human and macaque native states to reveal conserved and species-specific active regions. (C) The percentage of active regions with conserved and divergent activity. (D) Cartoon depicting the four conditions tested and how they are compared to identify cis and trans divergent regions. (E) Human-specific cis divergent regions determined by comparing human-specific active regions with the MH condition. Regions without MH activity were called cis divergent regions. (F) Macaque-specific cis divergent regions determined by comparing human-specific active regions with the HM condition. (G) Human-specific trans divergent regions determined by comparing human-specific active regions with the HM condition. (H) Macaque-specific trans divergent regions determined by comparing human-specific active regions with the HM condition. The heatmaps display ATAC-STARR-seq activity values for the specified region sets and experimental conditions. See also Figure S2.

Cis and trans gene regulatory divergence occur at similar frequencies

We first tested the conservation of regulatory activity between “native states” by comparing human DNA in human cells (HH) and macaque DNA in macaque cells (MM) (Figure 2B). Of the top ~10,000 regions considered, 3,034 (18%) regions have conserved activity, 6,922 (41%) regions were active only in the HH state and 6,941 (41%) were active only in the MM state (Figure 2B,C). The overlap between HH and MM active regions was significantly greater than expected (Figure S2E; p < 2.2e-16), and the divergent activity calls are supported by clear differences in ATAC-STARR-seq regulatory activity signal between HH and MM (Figure 2B). This indicates that many active regulatory sequences with shared accessibility have divergent activity, challenging the widely held assumption that conserved chromatin accessibility signifies conserved regulatory activity.

To determine the contribution of cis and trans changes to the differentially active regulatory regions, we compared their native activity to the corresponding non-native contexts—i.e., human DNA in the rhesus cellular environment (HM) and rhesus DNA in the human cellular environment (MH) (Figure 2D). We define cis changes as cases when sequence orthologs are tested in the same cellular environment but result in activity differences, implying that DNA variation contributes to regulatory activity differences. Conversely, we define trans changes as cases when a single sequence tested in different cellular environments results in activity differences, suggesting cellular environment changes contribute to the activity difference.

As expected, cis changes contributed to a large proportion of human-specific active regions (83%; 5,745). For these regulatory elements, the human DNA sequence was active in the human cellular environment, but the macaque sequence was inactive in both the macaque and human cells (Figure 2E). Likewise, 73% of macaque-specific active regions (5,034) diverged due to changes in cis (Figure 2F).

Surprisingly, similar proportions of human-specific active regions (79%; 5,443) were differentially active due to changes in trans, i.e., their DNA sequences were not active when assayed in the macaque cellular environment (Figure 2G). Likewise, 74% of macaque-specific active regions (5,165) were differentially active due to trans changes (Figure 2H). This was unexpected based on findings from previous smaller-scale studies that cis changes contribute to a greater number of differentially active regions than trans changes.33–35

Collectively, these data demonstrate that trans changes to regulatory element activity occur as frequently as cis changes between human and macaque LCLs, indicating that trans changes in cellular environments have widespread impact on species-specific gene regulatory activity. These classifications are supported by clear qualitative differences in ATAC-STARR-seq regulatory activity signal between conditions (Figure 2E–H). We also observe equivalent proportions of cis and trans differences in activity when we vary our threshold for calling activity, indicating the relative abundance of cis and trans divergence is not sensitive to the threshold used (Figure S2C,D).

Most species-specific regulatory differences are driven by changes in both cis and trans

Because cis changes and trans changes each contribute to the differential activity of many divergent active regulatory regions, we quantified how often they occur together in the same DNA regulatory element. Unexpectedly, we found that 70% of the human specific active regions (4,631) and 64% of the macaque specific active regions (3,994) displayed both cis and trans divergence (Figure 3A–D). Accordingly, we classified these regulatory regions as cis & trans, and regions only divergent in cis or trans as cis only and trans only, respectively. With these definitions, the cis & trans class accounts for 67.5% of all divergent active regions (human and macaque combined), whereas cis only and trans only represent about 17% and 15.5%, respectively. Thus, the regions with divergent regulatory activity between humans and macaques predominantly exhibit functional changes in both sequence and cellular environment, suggesting that cis and trans mechanisms jointly contributed to the evolution of individual gene regulatory elements.

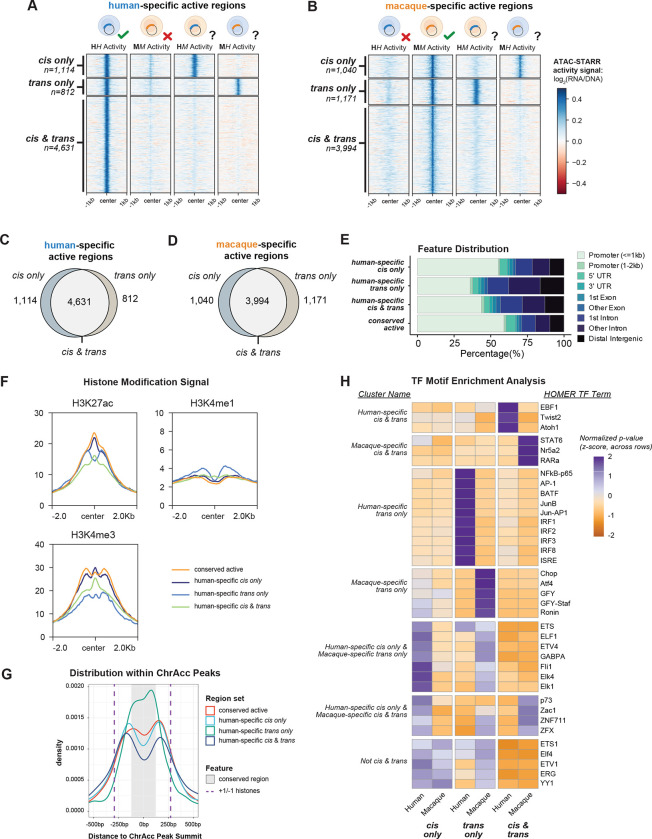

Figure 3: Most species-specific regulatory differences are driven by changes in both cis and trans.

(A,B) Comparison of ATAC-STARR-seq activity values across all conditions for (A) human-specific and (B) macaque-specific cis and trans divergent regions. Cis only, trans only, and cis & trans regions display activity signals consistent with their calls. (C,D) Euler plots of the cis only, trans only, and cis & trans classifications for (C) human-specific and (D) macaque-specific active regions. (E) Distribution of genomic annotations for human-specific cis only, trans only, cis & trans, and conserved active regions. (F) Profile plots of ENCODE GM12878 ChIP-seq signal for H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me3 histone modifications for the human-specific region classes. (G) Density plot of the distances between region center and accessible chromatin (ChrAcc) peak summits for human-specific cis only, trans only, cis & trans, and conserved active regions. The +1 and −1 histones are estimated with purple dashed lines by the ENCODE GM12878 H3K27ac signal summits and the conserved portion of the ChrAcc peaks is estimated with a grey box by the 17-way PhyloP score, see Figure S3C,D. (H) Clustered heatmap of TF motif enrichments for the combined or species separated cis only, trans only, cis & trans regions. Values are the z-score distributions of p-values, normalized across rows. Only the top 15 motifs for each region set were chosen for plotting. See also Figure S3.

Different mechanisms of regulatory divergence exhibit different TF motifs and locations within nucleosome-free regions

Given the prevalence of these distinct modes of regulatory divergence, we investigated the genomic context and functional annotations of the divergent region classes (cis only, trans only, cis & trans, and conserved active). Functional genomic data for the human GM12878 cell line is readily available, so we focused on the human-specific active regions unless otherwise specified. While all three divergent classes consisted of more promoter-distal regions than the conserved active class, a substantially higher proportion of trans only regions overlapped promoter-distal annotations than either cis only or cis & trans regions (Figure 3E), consistent with recent results on trans changes between human and mouse.34 Gene ontology annotations of genes near each region class revealed that all three cis/trans region classes were enriched for genes involved in cell-type specific pathways such as immune effector process and regulation of immune response. However, several terms distinguished the three divergent region classes, such as type I interferon signaling for the trans only regions and chromatin silencing for the cis only regions (Figure S3A). Conserved active regions were enriched for nearby genes involved in housekeeping pathways, such as RNA processing and translation. Together, this indicates that genes involved in different functional pathways may be prone to different kinds of regulatory divergence.

Human-specific cis only, trans only, and cis & trans regions also displayed different patterns of histone modifications, including histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac), histone H3 lysine 4 monomethylation (H3K4me1), and histone H3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) (Figure 3F, S3B). Trans only regions showed greater H3K4me1 signal and less H3K4me3 signal than the other classes, and this is likely explained by the human-specific region class annotations, since the trans only class is more enriched for promoter-distal annotations than the cis only or cis & trans classes (Figure 3E). We also observed a bimodal distribution of histone signal for trans only regions but not the others. This suggests that trans only elements are generally located within the center of the nucleosome free region (NFR), while the others are more common on the NFR periphery. To test this, we plotted the distance between region centers and the NFR center—the summit of the accessible chromatin peak (Figure 3G). We used GM12878 H3K27ac ChIP-seq signal to map the −1 and +1 nucleosomes (Figure S3C) and phyloP signal to identify the most conserved portion of the NFR (Figure S3D). As predicted, trans only regions are more often at the center of the NFR, while the cis only and cis & trans regions are more frequently located at the edges of the NFR. This means that trans only changes are more likely to occur at the center of NFRs, where there is stronger evolutionary constraint. Thus, evolutionary constraint at NFR centers may prevent cis changes, so trans changes could be required to drive differential activity of these elements.

TF binding differences likely drive activity differences between cis, trans, and cis & trans region classes. TF motif enrichment analysis revealed distinct TF motifs that distinguish regulatory regions both by the mechanism of gene regulatory divergence and species-specificity (Figure 3H). For example, human-specific trans only regions are enriched for IRF family TFs while macaque-specific trans only regions are enriched for the ATF4 TF, among others. Furthermore, IRF TFs are not enriched in human-specific cis & trans regions, suggesting the TFs that drive trans divergence for trans only regions are different from those that drive the cis & trans regions.

Key immune-related transcriptional regulators are differentially expressed between human and macaque LCLs

Trans regulatory divergence results from differences in the cellular environment, including differences in gene expression. To explore the mechanisms underlying the striking number of trans divergent regions (10,611 trans only and cis & trans combined), we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on both GM12878 and LCL8664 cell lines. The human and macaque LCL expression profiles cluster together and away from other human and macaque tissues (Figure S4A). Both LCLs also cluster closely with expression profiles from bulk, naïve, and memory B cells to the exclusion of other hematopoietic lineages (Figure S4B), suggesting they are transcriptionally similar to one another and to primary B cells.46 We also confirmed that waiting 24 hours after transfection to collect data resulted in minimal, if any, detection of plasmid-induced interferon-stimulated gene expression (Figure S4C–E). Thus, the human and macaque LCLs closely reflect primary B cells, and their transcriptional differences are likely the result of regulatory divergence between human and macaque.

We identified 2,975 differentially expressed genes with 1,505 upregulated in human and 1,470 upregulated in macaque (Figure 4A; human-specific log2(fold-change) > 2; macaque-specific log2(fold-change) < −2; both padj < 0.001). The human-specific genes were enriched for immune pathways, like interferon signaling and interleukin-10 signaling; while macaque-specific genes were enriched for extracellular matrix pathways, like collagen formation (Figure 4B). This indicates that, although these cell lines have broadly similar expression profiles (Spearman’s ρ = 0.85; Figure S4F), they display specific expression differences that could drive the trans-regulatory environment effects we observe. Moreover, these gene expression differences are likely due to species differences, and not cell line immortalization (Figure S4B) or plasmid-induced interferon-stimulated gene expression (Figure S4C–E) artifacts.

Figure 4: Trans only regions are bound by differentially expressed TFs.

(A) Volcano plot of differential expression analysis between GM12878 (human) and LCL8664 (macaque) cell lines. Point color represents genes upregulated in human (blue) or macaque (orange). Thresholds were log2 fold-change > | 2 | and padj < 0.001. (B) Enrichments of differentially expressed gene sets for Reactome pathways. Only the top 5 terms in each were plotted. (C) Enrichment of human-specific trans only regions for TF footprints stratified by the differential expression of the TF. Text is only shown for the most differentially expressed and enriched TFs. See Figure S4G for macaque trans only results. (D) Percentage of human-specific trans only regions that overlap a given footprint. TFs within the same motif archetype were merged before determining the number of overlaps. See Figure S4H for macaque trans only results. See also Figure S4.

Trans only regions are bound by differentially expressed TFs

The differential enrichment of IRF family motifs in human-specific trans only regions (Figure 3H) as well as the enrichment of interferon signaling genes in human-specific differentially expressed genes (Figure 4B) suggests a potential link between these differentially expressed TFs and the observed trans-divergent regions. To explore this hypothesis, we used TF footprints determined from ATAC-STARR-seq (Figure S1C) to test for TF footprint enrichment in the human-specific trans only and macaque-specific trans only regions. Indeed, we identified many TFs that are both significantly differentially expressed and enriched for binding in species-specific trans only regions; we define these TFs as “putative trans regulators” (Figure 4C, S4G). These putative trans regulators include several members of the IRF family (IRF4/7/8) that are markedly upregulated in human compared to macaque cells and are enriched for footprints in human-specific trans only regions (Figure 4C,D). Moreover, 18.7% of human-specific trans only regions were found to contain a TF footprint for one of these IRF family members that are canonically involved in innate immune responses47 (Figure 4D).

In total, the putative trans regulators we identified bind 37.1% of human specific trans only regions and 11.5% of macaque specific trans only regions. This highlights how changes to the expression of a few TFs can affect activity at a substantial number of the divergent DNA regulatory elements in a cell (Figure 4D,S4H). The remaining trans only regions may be explained by TFs that did not meet our putative trans regulator criteria, which included stringent significance thresholds and a 1:1 ortholog requirement in the comparative RNA-seq workflow. It is also likely that other mechanisms contribute to differences in the trans-regulatory environment, such as previously described species-specific differences in post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation of TFs.48,49 Notwithstanding, this data argues that the differential expression of only a handful of transcription factors drives a substantial amount of the trans-regulatory divergence observed.

Trans only regions are more conserved than cis only regions

Because trans changes result from differences in the cellular environment, while cis changes result from functional sequence differences, we hypothesized that DNA sequences in trans only regions would be more conserved than sequences in cis only regions. Supporting this hypothesis, both trans only and cis only regions are enriched for primate PhastCons conserved elements compared to expected background distributions (p = 1.4e-11 and 9.1e-4, respectively), but trans only regions are more enriched than cis only regions (Figure 5A; trans only odds ratio (OR) = 1.5; cis only OR = 1.2). In contrast, cis & trans regions are significantly depleted of conserved elements (Figure 5A; OR = 0.67, p = 1.1e-30). As expected, regulatory sequences with conserved activity between human and macaque had the strongest enrichment for conserved elements (Figure S5A; p = 8.1e-157, OR = 3.1).

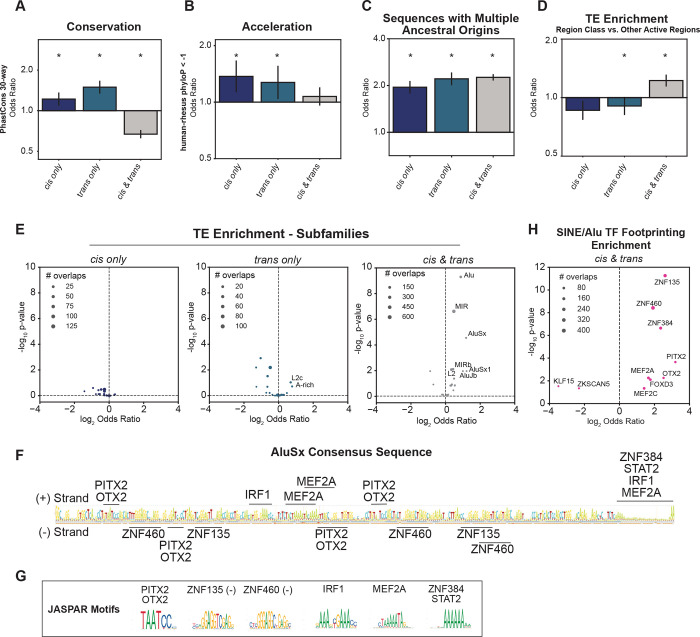

Figure 5: Cis only, trans only, and cis & trans regions have different degrees of conservation, acceleration, and transposable element enrichment.

(A-C) Enrichments of cis only, trans only, and cis & trans regions for (A) 30-way PhastCons elements, (B) human accelerated elements (defined as human-rhesus PhyloP < −1), and (C) sequences with multiple ancestral origins compared to an expected background. (D) Enrichment of divergent regions for transposable element (TE) overlap compared to other active regions. For all bar charts, the Fisher’s Exact Test odds ratio (OR) is plotted with 95% confidence intervals, which were estimated from 10,000 bootstraps. Windows were log2-scaled. Asterisks indicate a 5% FDR p-value < 0.05. (E) Enrichments of cis only, trans only, and cis & trans regions for subfamilies of TEs compared to an expected background. (F) The AluSx consensus sequence with TF binding sites for the TFs with enriched footprints. (G) Jaspar motifs of the relevant TFs. (H) Enrichments of SINE/Alu overlapping cis & trans regions for human TF footprints compared to an expected background. For the scatter plots, text is only shown for the most enriched subfamilies/TFs and point size represents the number of overlaps observed. See also Figure S5.

Accelerated substitution rates compared to neutral expectations can indicate shifts in sequence constraint, possibly resulting from positive selection.50–52 Both cis only and trans only elements are significantly enriched for elements with higher-than-expected substitution rates (Figure 5B; S5B; cis only p=4.9e-3; trans only p=4.7e-2), but as expected from their sequence-based mechanism of divergence, cis only regions are more enriched than trans only regions (cis only OR=1.4; trans only OR=1.3). Cis & trans elements showed no significant difference in substitution rates compared to background expectation (p=0.3). Overall sequence identity was similar across cis/trans groups, ruling out the possibility of systematic differences in the substitution rates of these regions underlying activity differences (Figure S5C).

Next, we investigated evolutionary origins of the regions in the divergent classes.53,54 All region sets are enriched for ancient sequences—from the placental common ancestor and older—so it is unlikely that differences in conservation are due to differences in sequence age (Figure S5D–E). Each region set is enriched for sequences with multiple ancestral origins, and cis & trans regions are the most significantly enriched (Figure 5C; conserved active p =3.6e-27; cis only p =7.9e-43; trans only p = 1.3e-56; cis & trans p = 4.6e-233).

Altogether, cis only and trans only regions both exhibit extremes of sequence conservation, divergence, and origin, as expected for sets of functional sequences in which some are experiencing negative selection and others positive selection. However, the sequences with cis only changes have more evidence of high substitution rates while trans only sequences are more enriched for conservation. This is consistent with their respective modes of divergence—sequence vs. cell environment. The fact that elements with cis & trans changes show substantially less evidence for selection suggests that they may arise from alternative mechanisms and have different functional roles.

Cis & trans regions are enriched for SINE/Alu transposable elements

Transposable element-derived sequence (TEDS) insertions are a source of raw sequence that often develops novel, species-specific regulatory functions.55–59 Thus, we investigated whether TEDS contribute to the divergent regulatory region classes, specifically in the less-conserved cis & trans elements. Overall, each class is depleted of TEDSs compared with genome-wide expectation (Figure S5F), consistent with previous findings that all gene regulatory sequences are depleted of TEDS.53,60 However, comparing within the regulatory element classes, cis & trans regions were enriched for TEDS compared to the other categories (Figure 5D; cis & trans OR = 1.14, p =9.7e-4; trans only OR = 0.86, p= 0.02; cis only OR = 0.91, p=0.08) suggesting that cis & trans elements more frequently originate from TEDS. Several TEDS families were uniquely enriched in cis & trans regions, most notably SINE/Alu and MIR derived sequences (Figure 5E, S5G–I). Additionally, SINE/Alu elements were more enriched in human-specific cis & trans regions compared to macaque-specific cis & trans regions (Figure S5H–I), suggesting that SINE/Alu derived sequence activity is more favorable in the human cellular environment.

SINE/Alu elements are a common source for new DNA regulatory elements.61–63 These sequences might have provided proto-enhancers in the last common ancestor of humans and rhesus macaques, developing over time into species-specific regulatory elements that experienced both cis & trans changes to obtain activity. The consensus AluSx sequence contains several sequences with high similarity to known TF binding sites (Figure 5F,G). Furthermore, TF footprinting analysis of cis & trans SINE/Alu elements (Figure 5H) provides strong evidence for the presence of TF binding, including the zinc-finger TFs, ZNF135, ZNF460, ZNF384, and PITX2, FOXD2, OTX2, RARG, and MEF2A. This demonstrates cis & trans regions are enriched for sequences derived from SINE/Alu elements and identifies several TFs that likely contributed to species-specific regulatory divergence.

Cis only regions are enriched for human variants associated with gene expression

Next, we explored the effects of genetic variation within human populations in the different regulatory divergence classes. First, we quantified enrichment for expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) in regions with divergent activity, hypothesizing that variation in cis only and cis & trans regions would be more likely to associate with variable gene expression within humans.

Cis only elements were significantly enriched for cis-eQTLs in EBV-transformed B cells from the GTEx consortium, while the other classes were not enriched for cis-eQTLs (Figure 6A; 1.6x fold-change, empirical p-value = 1e-4). Focusing on human-specific active elements, the difference between cis only and trans only regions is even more extreme (Figure 6A inset). This suggests that regulatory elements that experienced sequence-based evolutionary divergence between human and macaques are more likely to harbor variants that modulate gene expression among humans, while trans only regions are less likely to tolerate functional variants.

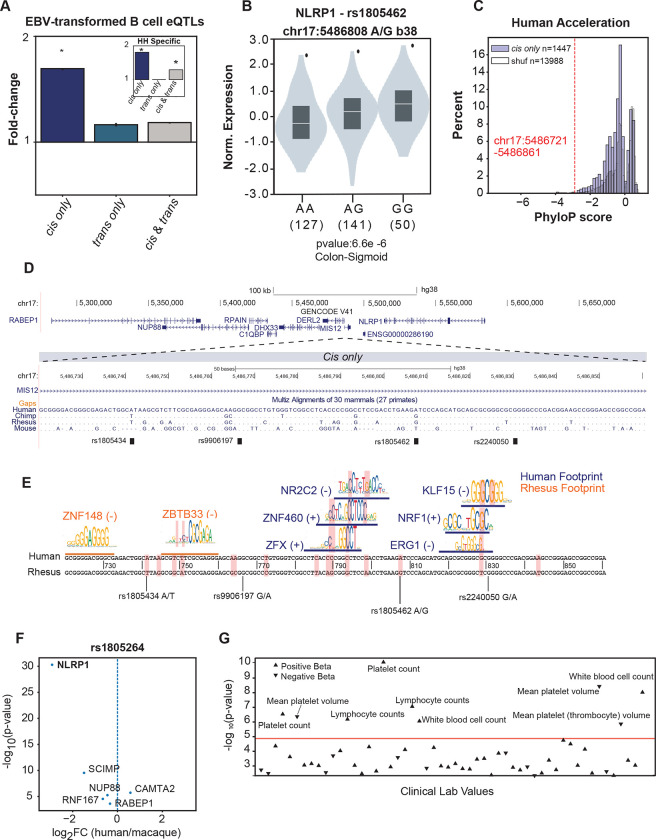

Figure 6: A human accelerated cis only element regulates NLRP1 expression.

(A) Enrichments of cis only, trans only, and cis & trans regions for EBV-transformed B cell eQTLs. The median fold-change compared to the expected background is plotted with 95% confidence intervals, which were estimated from 10,000 bootstraps. The inset in represents EBV-transformed B cell eQTLs enrichments for human-specific cis only, trans only, cis & trans regions. (B) Normalized expression scores of NLRP1 for the three possible genotypes of rs1805264. (C) PhyloP score distribution for cis only and expected shuffled regions compared to the PhyloP score of the chr17: 5,486,721–5,486,861 locus (red dotted line). (D) Genomic locus on Chr17 with a zoomed-in view of a multi-way sequence alignment for a highly accelerated human-specific cis only element. (E) Differential TF footprints between human and macaque coincide with human-accelerated substitutions. (F) Differential expression of rs1805462-associated eQTL genes between human and macaque LCLs. (G) PheWAS associations for rs1805462 with variation in quantitative blood traits. See also Figure S6.

We also evaluated enrichment for human genome-wide association study (GWAS) variants in divergent region classes. We selected immune and inflammatory traits from the UK Biobank (UKBB) where heritability had previously been observed in B cell gene regulatory loci.46 After removing HLA-overlapping peaks, we observed modest enrichment in all region classes for GWAS variants across 17 inflammatory and autoimmune traits with few differences between the classes (Figure S6A,B; empirical p-value <0.05).

We were particularly interested to explore variants associated with viral hepatitis C, because humans and chimpanzees, but not macaques or other Old-World Monkeys, are susceptible.64 Human-specific trans only regions are significantly and specifically enriched for viral hepatitis C GWAS variants, while macaque-specific regions are not (Figure S6B). This suggests that trans-regulatory changes contributed to the ape-specific susceptibility to hepatitis C and that human genetic variants in the regions bound by these trans factors modulate susceptibility to infection.

A human accelerated cis only element regulates NLRP1 expression and downstream trans changes

Our approach can identify the causes of evolutionary divergence at regulatory elements and quantify the resulting phenotypic outcomes at both the molecular and organismal levels. To illustrate this, we analyzed a GTEx cis-eQTL (rs1805264) associated with NLRP1, MIS12, SCIMP, RABEP1, RPAIN, DERL2 expression variation across multiple tissues (Figure 6B, S6C).26 This locus overlaps a cis only region on chromosome 17 in the MIS12 promoter that shows accelerated evolution between human and macaque (99th percentile of human acceleration scores; phyloP = −2.89) suggesting the locus experienced positive selection (Figure 6C,D). To understand how variation in this cis only region evolved to produce human-specific regulation, we evaluated differential TF footprinting between the human and rhesus macaque homologs. Human substitutions influenced binding site affinities for ZFX, ZNF460, NR2C2, EGR1, NRF1, and KLF15 transcription factors, which exclusively bind in human LCLs, as evidenced by differential footprinting (Figure 6E). Together, this indicates that human substitutions at this element created human-specific TF binding sites and human-specific cis only regulatory activity. This human-specific regulatory activity is then modulated by the cis-eQTL.

Of the genes influenced by genetic variation in this locus, NLRP1 shows the highest human-specific differential expression between the two LCLs (Figure 6F). NLRP1 is a viral sensor, including for SARS-CoV-2,65 and a core component of the pro-inflammatory signaling pathway. Thus, we hypothesize that variable NLRP1 expression may have substantial downstream effects on pro-inflammatory signaling that affects the trans-regulatory cellular environment.66–69 Indeed, the eQTL (rs1805264) is associated with human immune traits including higher platelet count and lymphocyte blood counts (Figure 6G). Together, this locus provides a key example of how a positively selected cis only region can affect expression of a target gene with potential to create substantial trans changes downstream, and, in turn, influence human-specific trait variation.

A single substitution may drive differential expression of ETS1 by perturbing RUNX3 binding in macaques

We demonstrate that differential expression of a small number of TFs can explain a substantial portion of the human-specific trans only regions observed (Figure 4), and that cis only regions can be a potent source of gene expression variation (Figure 6). These observations suggest that a small number of cis changes may ultimately lead to substantial trans changes if they act on genes, like TFs, that alter the cellular environment.8,9 To illustrate the ability of our approach to enable inference of these regulatory cascades, we identified a human-specific cis only region at a putative enhancer for ETS1, a trans regulator that is substantially more expressed in human LCLs and binds to >13% of human-specific trans only regions (Figure 4C,E and Figure 7A–C). The activity of this putative enhancer is supported by GM12878 H3K27ac signal and human B cell DNA hypomethylation.70,71 Furthermore, ETS1 is the closet gene to the DNA regulatory element and is contained within the same topologically associated domain (TAD) according to GM12878 Hi-C data (Figure 7C),72 so ETS1 is the likely target gene. Within this human-specific cis only region, we identified a macaque-specific substitution (T→C) that disrupts a RUNX3 motif, which is corroborated by the presence of a RUNX3 footprint detected in human but not macaque (Figure 7A). A GM12878 RUNX3 ChIP-seq peak also supports human TF binding at this locus.71 Furthermore, the functional relevance of this element is supported by two nearby SNPs, rs4262739 and rs4245080, which are eQTLs for ETS1 and have been associated with human trait variation including lymphocyte percentage.73,74 The ETS1 enhancer provides a powerful example of how a nucleotide substitution impacting the function of a single regulatory element leads to widespread changes in the activity of hundreds of regulatory elements across the genome. Altogether, these examples lead us to a model of how individual cis changes can ultimately generate substantial trans-divergent regulatory activity between species (Figure 7D).

Figure 7: A single substitution may drive differential expression of ETS1 by perturbing RUNX3 binding in macaques.

(A) Genomic locus of a human-specific cis only regions within a putative ETS1 enhancer. Public tracks for GM12878 H3K27ac and Human B cell DNA methylation corroborate this region as a putative enhancer. The first zoomed-in view of the locus shows a RUNX3 footprint present in human cells but not macaque cells. Nearby SNPs, rs4262739 and rs4245080, are associated with human trait variation. A further zoomed-in view of the footprint with a multi-species sequence alignment between human, chimpanzee, and macaque to reveal a macaque-specific substitution that perturbs an important nucleotide of the RUNX3 binding motif. (B) ETS1 and RUNX3 transcript per million (TPM) values for each replicate in human and macaque cells. (C) Hi-C data browser view of the ETS1 locus in GM12878 cells. Vertical dashed line represents the relative location of the putative ETS1 enhancer. (D) Model of how cis changes can become trans changes for other loci via TF expression/activity changes. First, cis changes alter the DNA sequence of a regulatory element to alter the affinity of TFs to the locus. This causes either enhancer activity loss or gain, based on the ancestral activity state of the enhancer. Alteration of enhancer activity, in turn, modifies the expression of target genes. If the target gene is a transcriptional regulator, the cis change would, therefore, also alter the cellular environment and become a trans change for other regulatory regions. (E) Model of how regions divergent in both cis & trans jointly drive differential regulatory element activity.

DISCUSSION

Here, we used a comparative ATAC-STARR-seq framework to directly identify differentially active DNA regulatory elements between human and rhesus macaque and to characterize their mechanisms of divergence—changes in cis, in trans, or in both cis & trans. We observe that trans-regulatory divergence is common, despite previous work suggesting that cis changes drive most gene regulatory divergence between species. Moreover, we find that most divergent elements have both cis and trans differences in activity, indicating that divergent gene regulatory elements are often shaped by changes in both the homologous DNA sequence and the cellular environment.

Cis only, trans only, and cis & trans region classes display unique characteristics

We identify three classes of regulatory elements based on their mode of divergence: cis & trans, cis only, and trans only. We discovered unique functional and evolutionary characteristics that define these region classes. In summary, cis only regions are more enriched for high substitution rates than trans only regions, while trans only regions are more enriched for evolutionarily conserved sequences, which is consistent with the fact that mutations within the regulatory regions are necessary for divergent activity in cis, but not in trans. In contrast, cis & trans regions show less sequence constraint, but are enriched for complex genomic rearrangements and transposable element derived sequences (SINE/Alu elements, in particular) compared to cis only and trans only regions, indicating that many arose from mutations to transposable element sequences that were present in the last common ancestor of humans and rhesus macaques. We also identified distinct TF motif enrichments for each region class, which highlights how differential activity, and its mode of divergence depends on unique TFs. Altogether our characterization of the divergent region classes provides insight into the relationship between mode of regulatory divergence and the gene regulatory networks they act on, which remains a key gap in the field.8

Trans-regulatory divergence is more extensive than previously recognized

In this study, we discovered more trans-regulatory divergence than previously reported.8,9,33–36 Several differences in study design, experimental system, and scale may explain this apparent discordance. First previous work largely focused on gene expression rather than regulatory element activity as the functional output. Second, many previous studies have not been able to directly test for trans changes, and thus assumed that elements without cis changes were driven by trans changes. Thus, they would miss a large number of elements with evidence of both types of change. Third, the two recent studies that did directly evaluate cis and trans changes on regulatory element activity focused on more limited, pre-selected sets of regions.34,35 Whalen et al. reported that nearly all of 159 tested human accelerated regions (HARs) diverged in cis. This is concordant with our findings that many cis divergent elements have accelerated substitution rates and are more likely to have accelerated substitution rates than other elements. Furthermore, they focus on HARs, rare elements with extreme evolutionary pressures that do not represent most regulatory loci. Mattioli et al. compared human and mouse regulatory element homologs and discovered that more regions were divergent due to changes in cis (n=660) than changes in trans (n=293). The difference in the cis:trans ratio may be due to different sampling of the elements tested, but the longer evolutionary divergence between human and mouse compared to human and macaque may also contribute. As previously mentioned, cis changes have been proposed to increase with evolutionary divergence,8,13,21 so we would expect to detect more cis changes at further evolutionary distances. More work is needed to determine the modes of gene regulatory divergence over both longer and shorter evolutionary distances, as well as different cellular contexts.

Putative trans regulators drive a substantial amount of trans-regulatory divergence in our system

To identify potential drivers of the trans regulatory divergence we observe, we defined “putative trans regulators” as a TF class that both display expression differences between species and bind to trans only regions as determined by TF footprinting. This revealed that a small number of key immune regulators, including ETS1, drive a substantial fraction of the human trans divergence we observed. This suggests that the differential expression of only a handful of transcription factors can drive a substantial amount of the trans-regulatory divergence.

We further showed that one of the putative trans regulators, ETS1, is likely regulated by a human-specific cis only region and discovered a key substitution in macaques that perturbs a RUNX3 TF motif. This is evidence of how a single substitution might influence the differential activity of a whole network of gene regulatory elements and species-specific immune-related traits, like Hepatitis C susceptibility in humans but not rhesus macaques. Indeed, we observed that only the human-specific trans only regions were highly enriched for Viral Hepatitis C associated variants. Altogether, our data will enable further characterization of putative trans regulators and identification of specific loci like the ETS1 regulatory element that may contribute to human-specific phenotypes.

A model of how cis and trans changes jointly drive divergent regulatory element activity

Cis & trans divergent regions acquired a change in cis and a change in trans during their evolution from the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) between humans and rhesus macaques (Figure 7E). We speculate that perturbations in trans are often likely to occur prior to cis. Once the relevant trans factors no longer bind, some elements will accumulate enough sequence variation to result in cis changes as well. Several lines of evidence from previous reports and our study support this hypothesis. For example, cis changes have been proposed to accumulate with greater evolutionary divergence whereas trans changes are favored short-term.8,13,21 This is likely because trans changes can change many regulatory region activities at once but may be more deleterious than cis changes.75 In this way, more significant phenotypic changes may be driven by changes to the trans-regulatory environment, but with a long-term fitness cost that can be ameliorated by local and precise cis changes to DNA regulatory elements.

Limitations of the Study

Several limitations of our study must be considered when interpreting our results. First, we only directly assay one genotype per species and infer evolutionary divergence from these models. While it would be ideal to evaluate additional genotypes for each species,76 this approach was necessary for several reasons. First, there are few non-human primate cell lines available to assay. Second, the comprehensive design of our comparative ATAC-STARR-seq approach is prohibitive for testing and interpreting activity variation across multiple genotypes and across multiple cellular environments.

Second, for experimental reasons, we leverage immortalized cell lines, whose cellular biology may not completely mirror the biology of primary B cells. The immortalization strategies differ for human and rhesus B cells. Specifically, the human B cell line was immortalized using Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV);40,41 whereas the rhesus cell line was immortalized in vivo by a rhesus lymphocryptovirus (rhLCV) related to EBV—so-called Rhesus Epstein-Barr Virus (RheEBV). 39,77,78 Although the viral EBNA2 gene, which drives transcription of many gene targets in EBV-infected cells,79 is homologous between EBV and rhLCV, host-restriction and co-evolutionary pressures may exaggerate many of our results. We envision that this could be avoided in future studies by using primate induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) lines.80 Beyond these possible confounders, our analysis of publicly available RNA-seq datasets shows that, at least transcriptionally, the two cell lines are highly similar both to each other and to human primary B cells (Figure S4A,B).

Despite the greater scale of the assay, ATAC-STARR-seq lacks the within-sample reproducibility of synthetic MPRA approaches that take dozens of measurements for each sequence assayed.81 For this reason, we cannot reliably compare effect sizes of activity. Instead, we binarize activity measures by applying significance thresholds to call active regions, which we then compare between conditions. Future analytical approaches may incorporate strategies that enable direct comparisons of activity. This would allow investigation of additional hypotheses, including proposed cis/trans compensation mechanisms on regulatory elements.34 In this way, we interpret cis & trans regions as individual regulatory regions where both species-specific DNA and species-specific environment are necessary to observe regulatory activity. We caution against interpreting compensatory or directional mechanisms on individual regulatory element activity from our data. However, while we did not explore how multiple regulatory elements control gene expression in a directional or compensatory fashion, this would be possible with our data, but validation studies that place gene regulatory elements in their endogenous context would be needed.

Concluding Remarks

We find that trans changes contribute to DNA regulatory element activity divergence between human and macaque nearly as often as cis changes. Moreover, we observed that both cis and trans changes affect most divergent regulatory elements. These findings enabled by our comparative ATAC-STARR-seq framework highlight an underappreciated role for the cellular environment in driving gene regulatory changes. We envision that our comparative strategy will be useful in future studies for mapping gene regulatory divergence between different species and across different cell types within the same species to agnostically determine the locations and roles of cis and trans divergence on gene regulatory function.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILIBILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Emily Hodges (emily.hodges@vanderbilt.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

ATAC-STARR-seq and RNA-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

All code has been deposited in a publicly available GitHub Repository. A link to the repository is listed in the key resources table.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell Lines

One human lymphoblastoid cell line (GM12878) and one rhesus macaque lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL8664) were used in this study.39–41 GM12878 is female, while LCL8664 is male. GM12878 and LCL8664 were purchased directly from Coriell and ATCC (CRL-1805), respectively. We cultured both cell lines with RPMI 1640 Media containing 15% fetal bovine serum, 2mM GlutaMAX, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were cultured at 37°C, 80% relative humidity, and 5% CO2. Cell density was maintained between 0.2×106 and 1.5×106 cells/mL with a 50% media change every 2–4 days. All cell lines were regularly screened for mycoplasma contamination.

ATAC-STARR-seq

We performed four ATAC-STARR-seq experiments following the method as described in Hansen & Hodges 2022.37 We created two ATAC-STARR-seq plasmid libraries, one for the GM12878 accessible genome and another for the LCL8664 accessible genome. For a total of four experiments, we electroporated each ATAC-STARR-seq plasmid library into both GM12878 and LCL8664 cells, resulting in the following conditions: GM12878 Library in GM12878 Cells (referred to as HH in text), GM12878 Library in LCL8664 Cells (HM), LCL8664 Library in GM12878 Cells (MH), and LCL8664 Library in LCL8664 Cells (MM). For HH and MH, we used Buffer R, whereas, for HM and MM, we used Buffer T from the Neon™ Transfection System 100 μL Kit (Invitrogen, #MPK10025). Both plasmid DNA and reporter RNAs were harvested from the same flask of cells and processed into llumina sequencing libraries. We repeated the electroporation, harvest, and sequencing library preparation steps for a total for three replicates; replicates were performed on separate days. The plasmid DNA and reporter RNA sequencing libraries for each replicate of each condition was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 machine, PE150, at a requested read depth of 50 or 75 million reads, for DNA and RNA samples, respectively, through the Vanderbilt Technology for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE) sequencing core. The GM12878 Library in GM12878 Cells was previously analyzed,37 but in a different manner (GEO accession: GSE181317).

RNA-sequencing

Before RNA isolation, we electroporated hSTARR-seq_ORI plasmid (Addgene #99296) into GM12878 and LCL8664 and matched the experimental conditions performed for the ATAC-STARR-seq plasmid library transfections, but on a smaller scale. Instead of twenty 100μL electroporation reactions, we performed a single 100μL reaction for each replicate and kept the cell count:DNA ratio (3×106 cells and 3μg plasmid DNA per reaction) and electroporation conditions the same. We performed two replicates each for GM12878 and LCL8664 cell lines.

24 hours later, we harvested total RNA using the TRIzol™ Reagent and Phasemaker™ Tubes Complete System (Invitrogen™, #A33251) and prepared Illumina-ready RNA-sequencing libraries using the SMARTer® Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit - HI Mammalian (Takara Bio, #634874). Libraries were analyzed for quality and submitted for sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 machine, PE150, at a requested read depth of 50 million reads through the Vanderbilt Technology for Advanced Genomics (VANTAGE) sequencing core.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS ATAC-STARR-seq Read Processing

FASTQ files were trimmed and analyzed for quality with Trim Galore! (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore) using the --fastqc and --paired parameters. Trimmed reads were mapped to hg38 with bowtie2 using the following parameters: -X 500 --sensitive --no-discordant --no-mixed.82 Mapped reads were filtered to remove reads with MAPQ < 30, reads mapping to mitochondrial DNA, and reads mapping to ENCODE blacklist regions using a variety of functions from the Samtools software package.83 When desired, duplicates were removed with the markDuplicates function from Picard (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Read count was determined using the flagstat function from Samtools. Library complexity was measured using the EstimateLibraryComplexity function from Picard and plotted with ggplot2 in R.84 Correlation plots were generated with the deepTools package85. Read counts for 1kb genomic windows were compared between the filtered, with-duplicates bam files using the multiBamSummary bins function and the following parameters: -e and --binSize 1000. Plots were generated using the plotCorrelation function and the following parameters: --skipZeros --corMethod pearson.

Chromatin Accessibility Peak Calling and Filtering

Accessible chromatin (ChrAcc) peaks were called in all four conditions (GM12878inGM12878, LCL8664inLCL8664, GM12878inLCL8664, LCL8664inGM12878) using Genrich with the -j parameter, which specifies ATAC-seq mode (https://github.com/jsh58/Genrich). For each condition, de-duplicated bam files for the three plasmid DNA replicates were provided to the peak caller; as part of peak calling, Genrich collapses replicates to yield one peak set for the given condition and uses variance between replicates to assign q-values. Peaks were filtered by q-value so that the genomic coverage of the entire peak set for a given condition was ~1.8% (q-value thresholds ranged between 1.1e-7 and 4.3e-6). The purpose of filtering for genomic coverage of each peak set was to account for data quality differences between the samples. This allows us to compare the most accessible 1.8% of the respective genomes rather than regions defined by a significance threshold. We compared several different genome coverages but qualitatively determined 1.8% best reflected true accessible peaks when looking at read pileup in a genome browser. We subsequently removed XY chromosomes since LCL8664 is male and GM12878 is female. Together, this yielded between 58,000–63,000 peaks for each of the four experiments. Peaks called in rheMac10 coordinates (LCL8664inGM12878 and LCL8664inLCL8664) were converted to hg38 coordinates using liftOver with -minMatch set to 0.9.

Differential Accessibility Analysis

We intersected the filtered ChrAcc peaks from each experiment using the default parameters of BEDTools intersect86 to isolate ChrAcc regions shared across all four contexts—this resulted in 29,531 shared ChrAcc peaks (Figure 1D). To obtain specific-specific accessible regions, we intersected only the GM12878inGM12878 and LCL8664inLCL8664 ChrAcc peaksets and wrote non-overlaps using the -v parameter. We performed motif enrichment using the findMotiftsGenome.pl script from the HOMER package (http://homer.ucsd.edu/)87 using the following parameters: -size given -mset vertebrates. We used ChIPSeeker to annotate differential accessible regions based on their distance to the nearest TSS (annotatePeak, level = gene & tssRegion = −2000/+1000), assign nearest neighbor genes, and perform Reactome pathway enrichment analysis using the assigned genes.88,89 For the annotation plotting, we removed the Downstream (<=300) term from the legend to simplify, since we did not observe assignments to that term.

Genome Browser

The respective genome browser tracks in Figure 1E, 6D, and 7A were viewed in the hg38 build using the UCSC genome browser90 and a combination of custom and public tracks. PDFs of these views were downloaded and further annotated in illustrator; positions of the tracks did not change during illustrator editing.

Active Region Calling Within Shared Accessible Peaks

Generation of Sliding Window Bins

We first merged all four ChrAcc peak sets (hg38 coordinates) into a single file with the UNIX cat function followed by BEDTools merge to generate a merged set of all peaks. Since ChrAcc peaks contain both active and silencing regulatory elements, it is important to divide peaks into smaller windows to best identify the element driving activity.37 To do this, we tiled the merged peak set with sliding windows usingBEDTools makewindows and the -s 10 -w 50 parameters; bins smaller than 50 bp were removed. This generated 7.65 million bins for analysis.

Filtering Bins for Alignability and Shared Accessibility

To perform comparative analyses between human and macaque genomes, we required that all bins were mappable between hg38 and rheMac10 in a 1:1 orthologous fashion and with at least 90% alignability. To do this, we used liftOver with -minMatch=0.9 to convert our bins from hg38 coordinates to rheMac10 and bins that did not map from hg38 to rheMac10 were removed from the hg38 file. Furthermore, bins that changed size by more than +/− 2bp in the liftOver were excluded from the analysis. Altogether, this removed ~552,000 bins (~7.3%).

Because differentially accessible regions would be only assayed in one ATAC-STARR-seq plasmid library, they would confound differential activity measures when comparing the respective genomes. For this reason, we also required that our bins overlap shared ChrAcc accessible peaks by intersecting the alignability-filtered bins with the 29,531 shared ChrAcc peaks described above; we used BEDTools intersect with the -u option set. This resulted in 2,028,304 (26.5%) sliding window bins for further analysis.

Active Region Calling

We called active regions for each of the four experimental conditions using the 2,028,304 filtered sliding window bins as input. To control against sample-to-sample variability, we called the top 10,000 most significantly active regulatory regions in each condition. By comparing the same number of DNA regulatory elements across conditions, we assume that a similar number of regions are active in each of the four experiments. This is a more conservative assumption than comparing regions called with the same q-value threshold across experiments, which can be greatly influenced by data quality differences and may not accurately reflect biology in a comparative analysis. We compared the results of calling different active region thresholds including the top 5,000, 10,000, 25,000, and 50,000 (Figure S2C,D).

To call active regulatory regions, we first assigned reads to the filtered sliding window bins using the featureCounts function from the Subread package with the following parameters: -p -B -O --minOverlap 1;91 for rheMac10 mapping reads, we used bins in rheMac10 coordinates (linked to hg38 coordinates by a unique bin ID). To avoid negative data interpretations, we next removed bins with a count of zero for any RNA or DNA replicate; between 8,775 and 70,819 bins were removed in each condition. We then quantified the activity of each bin by comparing RNA and DNA counts using DESeq2 (fitType=“local”).92 To obtain the top 10,000 most significantly active regions in each condition, we adjusted Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value thresholds to yield active bins that when merged in genomic space resulted in about 10,000 active regions for each condition–padj thresholds ranged between 0.026 and 0.11. To ensure our active regions were robust regulatory elements, we required that each region be made up of at least 5 bins by using BEDTools merge with the -c option and a custom awk script. For the supplemental analysis investigating threshold effects on cis and trans divergent regions calls, we followed the same process of adjusted padj thresholds to yield the desired active region count and then performed the same methods as described above to identify cis and trans divergent regions. We used ChIPSeeker to annotate the active regions in each condition based on their distance to the nearest TSS (annotatePeak, level = gene & tssRegion = −2000/+1000). For the annotation plotting, we removed the Downstream (<=300) term from the legend to simplify, since we did not observe any assignments to that term.

Generation of ATAC-STARR-seq Activity bigWigs

We generated ATAC-STARR-seq activity signal files with the deepTools package; to streamline this, we created a custom python script, which is available on the ATAC-STARR-seq method GitHub (github link; generate_ATAC-STARR_bigwig.py). We compared the log2 ratio of cpm-normalized RNA and cpm-normalized files using the bigwigCompare function and the following parameters: --operation log2 --pseudocount 1 –skipZeroOverZero; the cpm-normalized bedGraph files for RNA and DNA were generated using the bamCoverage function and the following parameters: -bs 10 --normalizeUsing CPM. MH and MM activity signal files were converted from bigwig to bedGraph (with the bigWigToBedGraph function from UCSC), lifted over to hg38 coordinates from rheMac10 coordinates with Crossmap,93 and then converted back to bigwig files using the bedGraphToBigWig function from UCSC. We generated bigwigs for individual replicates, as well as for merged replicate bam files.

Heatmaps of ATAC-STARR-seq Activity at Active and Inactive Bins

We first subsampled the inactive bins for each condition using the Unix shuf command (-n 150000) to reduce the number of regions plotted. ATAC-STARR-seq activity signal files for each replicate were plotted at their respective active and randomly subsampled inactive bins using the computeMatrix function (parameters: -a 500 -b 500 --referencePoint center -bs 25 --missingDataAsZero) and the plotHeatmap function (parameters: --sortRegions no --zMin −0.5 --zMax 0.5), both from deepTools.

Differential Activity Analysis

HH vs MM Activity Comparison

To identify conserved and species-specific active regions, we intersected the HH active regions with the MM active regions using BEDTools intersect. We called regions with at least a 50% reciprocal overlap as conserved active regions, whereas HH active regions that did not reciprocally overlap by at least 50% were classified as human-specific active regions and MM active regions that did not reciprocally overlap by at least 50% were classified as macaque-specific active regions. For all intersections, we used the following parameters: -f 0.5 -F 0.5 -e. This turns the 50% reciprocal into an “or” operation where either regions A&B are considered conserved active if either A or B overlaps the other by greater than 50%. This avoids mislabeling nested overlaps as differentially active where A could overlap B with 100% but B could be two times larger than A and therefore not overlap A by 50%. For the conserved active regions, we wrote the entire interval of the two overlapping regions using a combination of BEDTools intersect and merge in a custom script. We used the -v option in addition to the parameters listed above to write differentially active.

Identification of Cis Divergent Regions and Trans Divergent Regions

We determined if divergent active regions were a result of a change in the DNA sequence (cis) or a change in the cellular environment (trans) by intersecting species-specific active regions with the active region set from the relevant condition. For example, human-specific cis divergent regions were determined by intersecting the human-specific active regions with the MH active region set using BEDTools intersect. Human-specific active regions that did not reciprocally overlap by at least 50% were determined to be Human-specific cis divergent regions (parameters: -v -f 0.5 -F 0.5 -e). The other comparisons are indicated in Figure 2 and were performed in the same way as described above.

Identification of Cis & Trans Regions

To identify regions that were divergent in both cis & trans, we asked if the exact same region was contained in both the cis and trans divergent region sets using BEDTools intersect and the -f 1.0 -r parameters; we maintained species-specificity by only comparing human-specific cis with human-specific trans and macaque-specific cis with macaque-specific trans. Regions that were unique to the cis region set were classified as cis only, while regions that were unique to the trans region set were classified as trans only.

Observed vs. Expected Analysis of Active Region Overlaps

We calculated the expected overlap assuming random distribution in shared accessible chromatin for all differential activity comparisons. To do this, we first randomly shuffled the MM, HM, and MH active region sets within shared accessible chromatin with BEDTools shuffle (1000 iterations with the noOverlapping parameter). This yielded 1000 sets of randomly positioned active region sets for MM, HM, and MH within the analytical space of shared accessible chromatin. For each of the 1000 shuffled region sets per condition, we determined the expected number overlaps by intersecting them with either the HH active, the human-specific active, or the macaque-specific active regions using BEDTools intersect in the same manner done for the observed value. We then compared the expected overlap distribution with the observed value and performed Grubb’s Test in R to test if the observed value was a statistical outlier.

Heatmaps Comparing ATAC-STARR-seq Activity Between Conditions

ATAC-STARR-seq activity signal files were plotted at the respective regions using the computeMatrix function (parameters: -a 1000 -b 1000 --referencePoint center -bs 10 --missingDataAsZero) and the plotHeatmap function (parameters: --sortRegions no --zMin −0.5 --zMax 0.5), both from deepTools.

Functional Characterization of Cis and Trans Divergent Regions

Annotation

We used ChIPSeeker to annotate cis only, trans only, cis & trans, and conserved active regions based on their distance to the nearest TSS (annotatePeak, level = gene & tssRegion = −2000/+1000). For the annotation plotting, we removed the Downstream (<=300) term from the legend to simplify, since we did not observe assignments to that term.

TF Motif Enrichment

We first generated background regions for each region set by shuffling the respective regions within shared accessible chromatin 10 times using bedtools shuffle and the -chrom -noOverlapping -maxTries 5000 parameters. We then performed motif enrichment using the findMotiftsGenome.pl script from the HOMER package using the respective background and the -size given and -mset vertebrates parameters. The top 15 motifs for each region set were selected for plotting using pheatmap and the following parameters: scale=“row”, cluster_cols = FALSE, cluster_rows = TRUE, cutree_rows = 7, cellheight = 15, cellwidth = 30, method = “ward.D2”. Motifs within the same motif archetype94 were collapsed so that only one motif of that archetype was displayed on the heatmap in the main figure.

Gene Ontology

We performed gene ontology on the putative target genes for cis only, trans only, cis & trans, and conserved active regions using GREAT95 (http://great.stanford.edu/public/html/). We used the whole genome as background and assigned genes with the default Basal plus extension option. The top 10 terms were plotted in R.

Histone Modification Heatmaps

GM12878 ChIP-seq bigwig files for H3K27ac (ENCFF469WVA), H3K4me3 (ENCFF564KBE), and H3K4me1 (ENCFF280PUF) were downloaded from the ENCODE consortium71 and plotted at conserved active, human-specific cis only, human-specific trans only, and human-specific cis & trans regions with deepTools. Specifically, we used the computeMatrix function, with the following parameters: -a 2000 -b 2000 --referencePoint center -bs 10 –missingDataAsZero and the plotHeatmap function with the following key parameters: --sortUsing mean –sortUsingSamples 1 (the H3K27ac file).

Distance to ChrAcc Peak Summits

We first extracted region centers in R using the following operation: center = ((End-Start)/2)+start; decimals were rounded up to integers. The ChrAcc peak summits are provided in the original narrowPeak file for GM12878 ChrAcc peaks, so we obtained peak summits for the shared accessible peaks by intersecting shared peaks with the human-active peak file. The distance between region center and peak summit was calculated using the bedtools closest function and the -D ref parameter. This distance was then plotted as a density plot with ggplot2 in R.

To generate the H3K27ac profile plot, we plotted the GM12878 H3K27ac bigwig from ENCODE at ChrAcc peak summits using deepTools with the computeMatrix function (parameters: -a 500 -b 500 --referencePoint center -bs 10 –missingDataAsZero) and the plotProfile function. We repeated for the 17-way PhyloP bigwig after downloading from the UCSC genome browser (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenpath/hg38/phyloP17way/hg38.phyloP17way.bw).

Generating expected background datasets from shared accessible, inactive regions

We identified all shared accessible peaks from any of the four (HH, HM, MH, MM) experiments. We then used BEDTools to subtract active, shared accessible peaks, leaving a set of shared accessible, but inactive peaks. Then, we shuffled active regions with BEDTools (-noOverlapping -maxTries 5000) in this shared accessible, inactive genomic background 10x to produce length-matched expectation datasets. We used these elements as our background to interpret evolutionary and genomic features of active and divergent elements.

TF Footprinting

Transcription factor footprinting was performed using the TOBIAS software package.96 For both the GM12878inGM12878 and LCL8664inLCL8664 samples, we used ATACorrect to generate Tn5-bias corrected cut count signal files from deduplicated bam files. We then used the corrected cut-counts files to calculate TF binding in the respective genomes using the ScoreBigWig function. We then paired all core non-redundant vertebrate JASPAR motifs97 with the GM12878 and LCL8664 TF binding profiles to call individual transcription factor footprints in the two genomes using the BINDetect function and the --bound-pvalue parameter set to 0.05 . Motifs with a footprint were classified as bound, while motifs without a footprint were classified as unbound. Aggregate plots were generated using the deepTools package. Tn5-corrected signal was measured at bound and unbound sites for each respective TF using the computeMatrix reference-point function with the following key parameters: -a 75 -b 75 --referencePoint center --missingDataAsZero -bs 1. The resulting matrix was plotted using the plotProfile function.

To determine differential footprinting at specific loci, we compared the TF motifs that footprinted in human and rhesus. We mapped the position of rhesus TF footprints in hg38 by lifting those footprint coordinates from rheMac10 using LiftOver software from UC Santa Cruz.

Trans only TF footprint enrichment vs. differential expression

We evaluated footprints for each TF for enrichment in human-specific and macaque-specific trans only regions compared to 10x length-matched expected regions. Enrichment scores were computed using Fisher’s Exact Test with a BH adjusted p-value < 0.05. We intersected the enrichment score with the differential expression values of the specified TF. We removed footprints associated with TF multimers, for example the SMAD2-SMAD3-SMAD4 motif, so that only individual TFs, such as SMAD3, were assigned differential expression values. We also removed TFs that were not analyzed in the differential expression analysis, likely because they did not meet the 1:1 orthology requirement. Altogether, 386 TFs were retained for plotting. Scatterplots were made with ggplot2 and text was plotted for TFs with a footprint enrichment log2OR > 0, footprint enrichment padj < 1×10−10, differential expression log2FC > 0 (log2FC < 0 for macaque-specific), and a differential expression padj < 1×10−50 (padj < 1×10−20 for macaque-specific). For the TFs that met these criteria, which we defined as putative trans regulators, we intersected their footprints (BEDTools intersect: default parameters) with the respective trans only regions to determine the percentage with the given footprint. In a few cases we merged TF footprints, because some of the TFs shared the same motif archetype,94 for example IRF4, IRF7, and IRF8.

Evolutionary Characterization of Cis and Trans Divergent Regions

PhastCons Enrichment Analysis