Abstract

The ubiquitous species Pseudomonas stutzeri has type IV pili, and these are essential for the natural transformation of the cells. An absolute transformation-deficient mutant obtained after transposon mutagenesis had an insertion in a gene which was termed pilT. The deduced amino acid sequence has identity with PilT of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (94%), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (67%), and other gram-negative species and it contains a nucleotide-binding motif. The mutant was hyperpiliated but defective for further pilus-associated properties, such as twitching motility and plating of pilus-specific phage PO4. [3H]thymidine-labeled DNA was bound by the mutant but not taken up. Downstream of pilT a gene, termed pilU, coding for a putative protein with 88% amino acid identity with PilU of P. aeruginosa was identified. Insertional inactivation did not affect piliation, twitching motility, or PO4 infection but reduced transformation to about 10%. The defect was fully complemented by PilU of nontransformable P. aeruginosa. When the pilAI gene (coding for the type IV pilus prepilin) was manipulated to code for a protein in which the six C-terminal amino acids were replaced by six histidine residues and then expressed from a plasmid, it gave a nonpiliated and twitching motility-defective phenotype in pilAI::Gmr cells but allowed transformability. Moreover, the mutant allele suppressed the absolute transformation deficiency caused by the pilT mutation. Considering the hypothesized role of pilT+ in pilus retraction and the presumed requirement of retraction for DNA uptake, it is proposed that the pilT-independent transformation is promoted by PilA mutant protein either as single molecules or as minimal pilin assembly structures in the periplasm which may resemble depolymerized pili and that these cause the outer membrane pores to open for DNA entry.

Pseudomonas stutzeri is a gram-negative ubiquitous soil bacterium that is naturally transformable by chromosomal and plasmid DNA (1, 9, 11). The physiological state in which cells are transformable is termed competence and is reached in the late log phase of broth-grown cultures of P. stutzeri (26). P. stutzeri responds to limitations of single nutrients, such as C, N, or P, by a strong stimulation of transformation (27, 28). Also, the transformation of P. stutzeri in nonsterile soil by added DNA or by DNA released from bacteria in the soil has been demonstrated (37). Recently, following transposon mutagenesis of P. stutzeri, several dozen transformation-deficient mutants were isolated (16). During the characterization of these mutants it was discovered that the P. stutzeri cells have type IV pili and that these are essential for several properties of the cells, including the flagellum-independent movement of cells over the agar surface (termed twitching motility) (21), the ability to be infected by the type IV pilus-specific phage PO4 (6), the capacity to take up extracellular DNA into a DNase I-resistant state during competence, and the potential for natural genetic transformation. Pilus formation and all four pilus-associated properties were abolished by insertional inactivation of the structural gene for the pilus-forming protein subunit, pilAI or of pilC, an accessory protein for type IV pilus biogenesis (16, 18). Other mutants affected in transformation but normal in pilus formation, twitching motility, PO4 infection, and DNA uptake were found to be defective in comA or exbB (19). The ComA proteins and their homologs of naturally transformable gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria presumably form a pore in the cytoplasmic membrane through which taken-up DNA enters the cytoplasm (for a review, see reference 14). ExbB protein is a member of the TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex, which is thought to mediate the energy transfer of the electrochemical potential from the cytoplasm to the periplasm space (25) and in this way could energize the DNA translocation into the cytoplasm (19). From the above findings it was concluded that in P. stutzeri the type IV pili specifically act in the uptake of DNA into the periplasm and that the translocation of DNA into the cytoplasm is an independent process mediated by a separate set of proteins.

Type IV pili required for twitching motility and other movements over surfaces are widespread among gram-negative bacteria (21, 39). In pathogenic bacteria these organelles are also thought to act as colonization factors by mediating the adherence of bacteria to mammalian epithelial cells (41, 44). However, mutants unable to move over surfaces but having pili visible in the electron microscope have been isolated from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7, 41), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (43), Neisseria meningitidis (32), Escherichia coli (4), Myxococcus xanthus (45), and Synechocystis species (3). These mutants have a defect in the conserved pilT gene. On the basis of electron microscopic studies with phages adsorbing to type IV pili of P. aeruginosa, Bradley (6, 7) proposed that pili can be retracted and suggested that pilus retraction causes twitching motility. Recently it was found that the pilT mutants of N. gonorrhoeae were no longer competent for natural transformation, which was explained by assuming that pilus retraction mediates the transport of DNA into the cell (15, 43).

Here we show that a pilT mutant isolated as a transformation-deficient strain of P. stutzeri is defective for DNA uptake, twitching motility, and PO4 infection. A pilU gene detected downstream of pilT also contributes to natural transformability. We further observed that a PilA with a hexahistidine tag does not form pili but supports transformability and that this transformability is no longer dependent on functional pilT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The E. coli and P. stutzeri strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. They were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar. If required, LB media were supplemented with ampicillin (1 g liter−1 for P. stutzeri; 100 mg liter−1 for E. coli), gentamicin (10 mg liter−1), kanamycin (60 mg liter−1), or streptomycin (1 g liter−1). The minimal medium for P. stutzeri was minimal pyruvate agar medium (27).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli K-12 SF8 recA | recA56 | 17 |

| P. stutzeri | ||

| JM375 | Rifr Smrhis+ | 11 |

| JM302 | hisX1 | 11, 37 |

| LO15 | JM302 Rifr Nalr | 16 |

| Tf59 | LO15 pilT::Kmr (pSUP102GmTn5B20) | This study |

| Tf591 | LO15 pilU::lacZGmr | This study |

| Tf700 | LO15 ΔpilTU::Gmr | This study |

| Tf300 | pilAI::Gmr | 16 |

| Tf590 | pilAI::GmrpilT::Kmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRSF1010d | pRSF1010 with a 800-bp PstI deletion inactivating the Sur gene | 16 |

| pCOM59 | pKT210 carrying 6.2 kb of chromosomal JM375 DNA | This study |

| pCOM59d | pRSF1010d carrying a 3.44-kb PstI fragment of pCOM59 | This study |

| pBluescript II KS(+) | Apr | Stratagene |

| pKS59 | pBluescript II KS(+) carrying a 3.44-kb PstI fragment of pCOM59d | This study |

| pST59 | About 30 kb religated chromosomal DNA of Tf59 including the inserted pSUP102GmTn5B20 | This study |

| pUCP19 | oricolE1 oripRO1600 Apr | 35 |

| pUCPpilT+ | pUCP19 carrying the pilT+ gene of P. stutzeri | This study |

| pAB2001 | AprlacZGmr | 2 |

| pKSpilU+ | pBluescript II KS(+) carrying the pilU+ gene of P. stutzeri | This study |

| pKSpilU::lacZGmr | pKS59 carrying a lacZGmr cassette in the NcoI site of pilU | This study |

| pKS59::Gmr | pKS59 carrying an 1.5-kb BstBI/EcoNI deletion of parts of pilT and pilU; insertion of a Gmr cassette | This study |

| pUCPpilU+ | pUCP19 carrying the pilU+ gene of P. stutzeri | This study |

| pKT240 | Smr oriRSF1010 | 42 |

| pKTpilU | pKT240 carrying the pilU+ gene of P. aeruginosa PAK | 42 |

| pUCPpilT+U+ | pUCP19 carrying the pilT+U+ genes of P. stutzeri | This study |

| pUCPSK | pUCP19-based Pseudomonas-Escherichia shuttle vector with multiple cloning site and promoter sequence of pBluescript II SK(+) | 40 |

| pUCPA1Ha | pUCPSK carrying the pilAI gene with six histidine codons added on the C terminus | This study |

| pUCPA1Hs | pUCPSK carrying the pilAI gene in which the six C-terminal amino acid codons were replaced by six histidine codons | This study |

Quantitative plate transformation.

In this test cells of a fresh overnight culture are mixed with his+ DNA, incubated on the surface of a fresh LB agar plate, resuspended, and then analyzed for transformants by plating on LB agar (total viable counts) and minimal pyruvate agar (his+ clones). The assay was performed as previously described (27) using chromosomal DNA from strain JM375 at various concentrations. The DNA-cell mixture was incubated on LB agar for 16 h before cells were resuspended for determination of the transformation frequency. The frequency of transformation is the number of his+ clones per viable count.

DNA manipulations and plasmid and strain construction.

Preparation of plasmid DNA, DNA restriction, DNA ligation, and DNA sequencing were performed according to standard procedures (34). Plasmid DNA and chromosomal DNA were purified with Qiagen columns according to the instruction of the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilgen, Germany). PCR products were purified with the QIAquick spin kit (Qiagen, Hilgen, Germany). Electroporation of E. coli and P. stutzeri cells using a gene pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.) was performed as previously described (16). The insertion site of the plasmid pSUP102GmTn5B20 (38) in pilT of Tf59 (which was indicated by the Gmr of the insertion mutant) was identified as follows. Chromosomal DNA of the insertion strain was digested with KpnI, religated, and electroporated into E. coli SF8 recA. Selection was on plates containing 50 mg of kanamycin liter−1. One transformant contained a plasmid (pST59) with about a 30-kb chromosomal insert which replicated due to the pACYC origin present in pSUP102Gm. The nucleotide sequences neighboring the Tn5 insertion site were identified by sequencing from IS50R and IS50L into the chromosomal P. stutzeri DNA using primers IS1 (5′-GGAGGTCACATGGAAGATCAGATCC-3′) and IS2 (5′-GGCCAGTGAATCCGTAATCATGG-3′). The pilT gene was amplified from chromosomal DNA by PCR using the primers PilT1 (5′-ATAGTTCTCGCCGAAATCGCTCAG-3′) and PilT2 (5′-TTAAAAATTTTCCGGCTGCTTGGCCTTTTCCTTGGCGCTG-3′), and the product was cloned into the SmaI site of pUCP19. The pilU gene was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA using primers PilU1 (5′- AAGAACGAGATATATAATGGAATTCGAGAAACTGTTGCGCCTGA TG-3′) and PilU2 (5′-TCAGCGGAAACTGCGCCCCGGGTCGTCATC-3′), and the product was cloned into the SmaI site of pUCP19. The pilT pilU deletion mutation was constructed as follows. Plasmid pKS59 was digested with BstBI and EcoNI for deletion of most parts of pilT+ and pilU+, blunted and ligated to a gentamicin cassette amplified by PCR from pUCGm (36) using the primers Gm1 (5′-CAGCGGTGGTAACGGCGCCAG-3′) and Gm2 (5′-TTTACCGAACAACTCCGCGG-3′). In vitro-constructed deletion and insertion mutations were transferred into the chromosome by natural transformation with linearized DNA of plasmids carrying the mutant alleles. The allelic exchange was verified by PCR analysis of the transformants.

PCR amplification of pilAI for C-terminal fusion of six histidine residues included forward primer PilAI-F2 (5′-TTTAACGGAATTCAaggagACAAAAAATGAAAGCCCAAATGCAG-3′; The EcoRI site is in italics, the ribosome binding sequence is in lowercase, and the start codon is in bold) and the reverse primer for terminal addition of six histidine residues PilAI-R1 (5′-CCTAACCGCTCGAGCGGTTAatgatgatgatgatgatgGGAGCACTTGCCTGGCTTGTAC-3′; the XhoI site is in italics, the six histidine codons are in lowercase, and the stop codon is in bold) or primer PilAI-R2 for the substitution of the terminal six amino acids of PilAI by six histidine residues (5′-CCTAACCGCTCGAGCGGTTAatgatgatgatgatgatgGTACTTGGCGTCCAAGGTGCTGCTGGCGC-3′; the XhoI site is in italics, the six histidine codons are in lowercase, and the stop codon is in bold). The purified PCR products were treated with EcoRI and XhoI and ligated to the EcoRI- and XhoI-treated pUCPSK vector (40).

Binding and uptake of DNA by competent cells.

Chromosomal DNA of P. stutzeri JM375 was purified by chromatography on Qiagen columns (Qiagen, Hilgen, Germany) and labeled with [3H]deoxythymidine triphosphate by nick translation using the kit from Promega (Madison, Wis.) as previously reported (16). The specific radioactivity of the preparations ranged between 5 × 106 and 8 × 106 cpm μg−1. Preparation of competent cells and measurements of binding and uptake in a DNase I-resistant state were performed as previously described (16).

Plating of phage PO4 and determination of twitching motility.

Plating of PO4 on a lawn of P. stutzeri cells was performed in a spot test as described by Bradley (6). Twitching motility was determined by inspecting single colonies for spreading zones on fresh LB agar plates after incubation in a humid atmosphere at 37°C for 10 days.

Electron microscopy.

Sample grids with Formvar film were touched to microcolonies grown at 37°C on fresh LB agar plates for 12 to 15 h. The grids were floated for 2 to 10 min on a drop of 1% uranylacetate for staining. After removal of excess uranylacetate solution with filter paper and 15 min of air drying, transmission electron microscopy was performed with a Zeiss JM109A electron microscope.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the pilT pilU region has been deposited in the EMBL database under the accession no. AJ249385.

RESULTS

Characterization of the transformation-defective mutant Tf59.

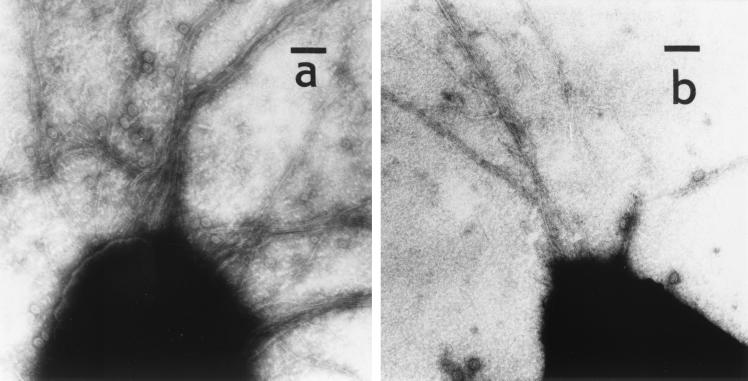

Among the transformation-deficient mutants of LO15 obtained after transposon mutagenesis with plasmid pSUP102GmTn5B20 (38) and identified as previously described (16), the mutant Tf59 gave an undetectable transformation frequency, i.e., ≤0.0003 relative to the parental strain (Table 2). The mutant was no longer sensitive to the pilus-specific phage PO4 (6) and did not show twitching motility (Table 2), a phenotype mostly associated with the loss of type IV pili. However, electron microscopic examination of the mutant cells revealed that they have pili. The number of pili was much higher than that of the parental strain, which has only few polar pili (Fig. 1). The many pili on the Tf59 cells form mostly bundles. Hyperpiliation associated with the loss of PO4 sensitivity and twitching motility has previously been described for pilT and pilU mutants of P. aeruginosa (41, 42).

TABLE 2.

Relative transformation frequencies, PO4 sensitivity, and twitching motility of P. stutzeri wild-type and pilT and pilU mutants

| Straina | Plasmid |

pil allele on chromosome

|

Presence of pil gene on plasmid

|

Relative transformation frequencyb | PO4 platingc | Twitching motilityd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pilT+ | pilU+ | pilT+ | pilU+ | |||||

| LO15 | None | + | + | − | − | 1 | + | + |

| pUCPpilT+ | + | + | + | − | 1.1 ± 0.3 | + | + | |

| pUCPpilU+ | + | + | − | + | 1.3 ± 0.2 | + | + | |

| pUCPpilT+U+ | + | + | + | + | 1.3 ± 0.3 | + | + | |

| Tf59 | None | − | + | − | − | ≤0.0003 | − | − |

| pUCPpilT+ | − | + | + | − | 0.8 ± 0.1 | + | + | |

| pUCPpilU+ | − | + | − | + | ≤0.0008 | − | − | |

| pUCPpilT+U+ | − | + | + | + | 0.9 ± 0.2 | + | + | |

| Tf591 | None | + | − | − | − | 0.1 ± 0.02 | + | + |

| pUCPpilU+ | + | − | − | + | 1.4 ± 0.3 | + | + | |

| pUCPpilT+ | + | − | + | − | 0.1 ± 0.01 | + | + | |

| pUCPpilT+U+ | + | − | + | + | 1.6 ± 0.2 | + | + | |

| pKTpilU | + | − | − | +e | 1.3 ± 0.2 | + | + | |

| Tf700 | None | − | − | − | − | ≤0.0003 | − | − |

| pUCPpilT+ | − | − | + | − | 0.06 ± 0.02 | + | + | |

| pUCPpilU+ | − | − | − | + | ≤0.0005 | − | − | |

| pUCPpilT+U+ | − | − | + | + | 0.9 ± 0.2 | + | + | |

As controls, the vectors pUCP19 and pKT240, corresponding to the plasmids with pilT or pilU genes, were electroporated into LO15, Tf59, Tf91, and Tf700. These strains gave transformation frequencies, PO4 plating results, and twitching motility similar to those of the corresponding strains without vector plasmid.

Transformation frequencies were obtained by plate transformation and are expressed relative to the frequency in LO15 [(2 ± 0.2) × 10−5] using 1.5 μg of DNA per assay. Values are means of three experiments with standard deviations.

Phage titer was 108 ml−1; 0.02 ml was spotted. +, confluent lysis of cells; −, no visible plaques.

−, no twitching zones after 10 days at 37°C.

pilU+ of P. aeruginosa (42).

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of P. stutzeri pil mutants. (a) pilT mutant Tf59; (b) pilU mutant TF591, which is similar to the wild type (16). Bar, 100 nm.

Identification of the pilT gene.

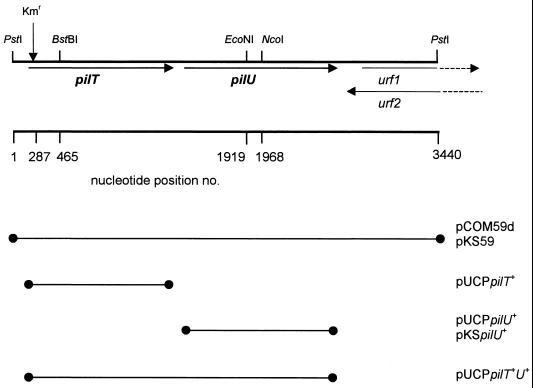

To identify the gene(s) complementing the transformation defect of strain Tf59, the cells were transformed by electroporation with gene bank plasmids consisting of vector pKT210 (1) with chromosomal inserts of P. stutzeri DNA as previously described (16). One gene bank plasmid, termed pCOM59, with an insert of about 6.2 kb (Table 1) restored the transformability of Tf59. Subcloning of insert fragments into vector pRSF1010d indicated that a 3.44-kb PstI DNA fragment (in pCOM59d) complemented the transformation deficiency, PO4 resistance, and defective twitching motility of the Tf59 strain. Sequencing of the 3.44-kb DNA fragment revealed the presence of two complete and two partial open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 2). The deduced protein of the first ORF from nucleotide positions 248 to 1282 had a molecular mass of 38 kDa (344 amino acids). The transposon insertion site was determined on the chromosome of Tf59 (see Materials and Methods) between nucleotide positions 286 and 287. The deduced amino acid sequence had identity with PilT proteins of P. aeruginosa (94%) (41) and N. gonorrhoeae (67%) (8), which are located in the cytoplasmic membrane fraction. The gene of P. stutzeri was termed pilT+. A typical nucleotide binding site (positions 635 to 658) and a hydrophobic domain are present. The PCR-amplified pilT+ gene was cloned into pUCP19, giving pUCPpilT+. When this plasmid was electroporated into strain Tf59, the defects in PO4 plating, twitching motility, and transformation were fully restored (Table 2), as well as the normal piliation seen in the electron microscope (data not shown), indicating that the phenotype of the pilT insertion mutation was not the result of a polar effect.

FIG. 2.

Schematic presentation of the 3.44-kb PstI fragment of the P. stutzeri chromosome covering the pilT and pilU genes (arrows indicate direction of transcription). The insertion site of pSUPTn5B20 is indicated by an arrow (Kmr). The lines with a dot on each end are the cloned DNA segments present in the different plasmids indicated. urf1 and urf2 are possible unknown ORFs.

Identification of pilU+ and its requirement for transformation.

Downstream of pilT+ an ORF was identified at positions 1340 to 2485 (Fig. 2). The deduced sequence of 381 amino acids predicted a molecular mass of 42 kDa. The sequence had an identity of 88% with PilU of P. aeruginosa (42). A nucleotide binding motif was identified (positions 1727 to 1750), and the gene was termed pilU. Downstream of pilU+ are two putative partial ORFs with opposite orientations and covering the same DNA segment (urf1 and urf2) (Fig. 2). The deduced amino acid sequences had no similarities to any other protein in the databases.

To find out whether pilU+ was involved in natural transformation of P. stutzeri, the lacZGmr cassette contained on a SmaI fragment in pAB2001 (2) was ligated to NcoI-digested and blunted pKSpilU+ (Table 1; Fig. 2), and the pilU::lacZGmr allele was inserted into the chromosome of LO15 (giving mutant Tf591) by allelic exchange through natural transformation as previously described (16). The correct insertion of the lacZGmr cassette in the chromosomal pilU gene of Tf591 was confirmed by PCR. Strain Tf591 was only 10% naturally transformable compared to LO15, while PO4 plating and twitching motility were normal (Table 2), and the piliation seen in the electron microscope (Fig. 1) was like that of the wild type. This suggested that pilU+ was required for full transformability but not for pilus biogenesis. In P. aeruginosa the pilU+ gene is not necessary for PO4 plating, either (42). However, pilU+ in P. aeruginosa is essential for twitching motility and pilU mutants are hyperpiliated (42).

Complementation of a pilU insertion mutation by autologous and heterologous pilU+ genes.

The pilU+ gene was amplified by PCR and cloned in pUCP19 to give pUCPpilU+, in which the correct orientation of pilU under the control of the lac promoter was verified by PCR. This plasmid electroporated into strain Tf591 fully restored the transformability of the strain, which was not the case with pUCPpilT+ (Table 2). Since pilU+ in trans sufficed for complementation, the lacZGmr cassette in pilU of Tf591 does not have a polar effect that would cause the low transformability. As expected, the plasmid pUCPpilT+U+ with both pilT+ and pilU+ also complemented Tf591 (Table 2). Remarkably, the plasmid pKTpilU (42) which carries the pilU+ gene of P. aeruginosa PAK also complemented Tf591 (Table 2), indicating that the pilU+ gene from a nontransformable species could provide the function necessary for efficient natural transformation of the P. stutzeri pilU mutant.

Characterization of a pilT pilU double-deletion mutant.

To examine the effect of combined pilT and pilU mutations, we constructed a double-deletion strain. A Gmr cassette was cloned between the BstBI and EcoNI sites of the pilT pilU region in pKS59 (Table 1), giving pKS59::Gmr, which deletes most of both genes (Fig. 2). With selection for Gmr, the deletion mutation in the plasmid was transferred to the chromosome of LO15 by natural transformation. The correct chromosomal insertion of the double deletion was verified by PCR in the transformant Tf700 using primers PilT1 and PilU2. Tf700 had the same phenotype as Tf59 in being defective for PO4 plating, twitching motility, and natural transformation (Table 2), and the cells were hyperpiliated (data not shown). The transformation defect of Tf700 was complemented by pUCPpilT+ to 6% compared to LO15 (Table 2). The low level is due to the inactivated chromosomal pilU gene in the strain (Table 2). PO4 plating and twitching motility were completely restored in Tf700 by pUCPpilT+ (Table 2). The pilU+ gene provided by pUCPpilU+ did not complement the defects of Tf700 in PO4 plating, twitching motility, and transformation (Table 2), whereas the plasmid pUCPpilT+U+ restored a wild-type phenotype to Tf700 (Table 2). These results confirm that pilT+ is essential for transformability, PO4 plating, and twitching motility, while pilU is necessary to bring transformation up to the wild-type level.

DNA binding and uptake.

Competence-specific binding of [3H]thymidine-labeled P. stutzeri DNA to cells of LO15 was previously demonstrated (16). About one-third of the bound DNA was taken up within 90 min at 37°C (measured as the fraction of DNA becoming DNase I resistant). P. stutzeri cells having no pili due to insertional inactivation of pilAI or pilC were reduced in competence-specific binding and uptake of DNA about eightfold and fourfold, respectively, giving a certain background level of DNA becoming DNase I resistant (16). As shown in Table 3, the pilT strain Tf59 bound at least as much [3H]thymidine-labeled chromosomal P. stutzeri DNA as LO15, but the amount of DNA taken up was significantly lower than that in LO15 (about one-third), resulting in only about 9% uptake of the bound DNA. Similarly, in the pilT pilU double mutant Tf700, there was full binding of DNA but significantly little (6%) or no uptake (considering a background level of 10 to 20 pg of DNase I-resistant DNA per 5 × 108 cells) (16). These observations suggest that the transformation deficiency of the pilT mutants results from a defect in DNA uptake (Table 3). In contrast, the pilU mutant Tf591 bound almost as much DNA as LO15 and took up a little less DNA. The presence of the heterologous pilU+ from P. aeruginosa in Tf591(pKTpilU) gave a (non significant) increase of uptake, so that the value came close to that of LO15 cells (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Binding and uptake of [3H]thymidine-labeled chromosomal P. stutzeri DNA by cells of various P. stutzeri strainsa

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Amt (pg) of DNA/5 × 108 cells (n)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Bound | Taken up | ||

| LO15 | Wild type | 144 ± 42 (11) | 55 ± 20 (10) |

| Tf59 | pilT | 210 ± 36 (3) | 20 ± 2 (3)c |

| Tf591 | pilU | 135 ± 26 (4) | 36 ± 10 (4) |

| Tf700 | pilT pilU | 228 ± 59 (5) | 14 ± 9 (4)c |

| Tf591(pKTpilU)d | pilU/pilU+Pa | 119 ± 33 (6) | 43 ± 13 (6) |

The cells were from the late logarithmic growth phase, in which LO15 cells (wild type) are at the competence maximum (0.5 × 109 to 1 × 109 cells per ml).

n, number of experiments. Data are averages with standard deviations.

The DNA uptake by Tf59 and Tf700 was found by t test to be significantly lower than that of LO15 (P = 0.015 and 0.002, respectively).

The plasmid pKTpilU expresses the pilU+ gene of P. aeruginosa (Pa) (42).

A PilAI protein with a hexahistidine tag supports transformation.

For the purification of PilAI by immobilized-metal affinity chromatography on nickel-nitriloacetic acid columns, pilAI-derived genes with terminal six-histidine tags were generated. Since the N terminus of PilAI is cleaved during transmembrane transport, only the C terminus of the mature protein can be tagged by histidine residues. This was achieved by PCR amplification of pilAI using a reverse primer having six histidine codons at the 5′ terminus followed by the stop codon TAA. The PCR product was cloned into vector pUCP19. To determine whether the tagged protein was functional in vivo, the corresponding plasmid was electroporated into the pilAI mutant Tf300 and the phenotype of the transformant was characterized. Plasmid pUCPA1Ha coding for PilAI with a C-terminal addition of six histidine residues did not restore natural transformation, twitching motility, or PO4 sensitivity to the pilAI mutant (Table 4), indicating that the tag interfered with the transport or function of the modified pilin. However, when the C-terminal six amino acids of PilAI were replaced by six histidine residues, the allele (present in pUCPA1Hs) restored the transformability of Tf300 to the level that was provided by the cloned pilAI+ gene (Table 4, compare line 6 with line 3). Sequencing verified the correct sequence of the pilAI gene with its amino acid substitution. In contrast to transformability, twitching motility was not restored (Table 4). The efficiency of plating of PO4 was about 0.006 compared to that on LO15(pUCP19) or Tf300(pUCPA1), and the plaques were rather diffuse. Electron microscopy did not reveal pili on the Tf300(pUCPA1Hs) cells (data not shown). The phenotype of these cells is novel in that they are transformable despite the absence of pili. So far, nonpiliated mutants of P. stutzeri, including pilAI and pilC mutants (16) and pilR, pilS, and rpoN mutants (S. Tippelt, K. Shah-Hosseini, S. Graupner, and W. Wackernagel, unpublished data), have all been transformation deficient.

TABLE 4.

Transformation, PO4 infection, and twitching motility of P. stutzeri strains with plasmids expressing wild-type and C-terminally hexahistidine-tagged PilA proteins

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Plasmida | Transformation frequency with chromosomal his+ DNAb | n | PO4 infectionc | Twitching motilityd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LO15 | pUCP19 | 1.82 × 10−6 (1) | 4 | + | + | |

| Tf300 | pilAI::Gmr | pUCP19 | ≤2 × 10−9 (≤0.001) | 4 | − | − |

| Tf300 | pilAI::Gmr | pUCPA1 | 1.55 × 10−6 (0.85) | 2 | + | + |

| LO15 | pUCPA1 | 1.60 × 10−6 (0.88) | 2 | + | + | |

| Tf300 | pilAI::Gmr | pUCPA1Ha | ≤1 × 10−9 (≤0.0005) | 2 | ND | ND |

| Tf300 | pilAI::Gmr | pUCPA1Hs | 1.87 × 10−6 (1.03) | 3 | (+) | − |

| Tf590 | pilT::KmrpilAI::Gmr | pUCPA1Hs | 1.11 × 10−6 (0.61) | 3 | − | − |

| Tf59 | pilT::Kmr | pUCP19 | ≤1 × 10−9 (≤0.0005) | 4 | − | − |

| Tf59 | pilT::Kmr | pUCPA1 | ≤1 × 10−9 (≤0.0005) | 2 | ND | − |

The pUCP19 vector contains the pilAI+ gene in pUCPA1, the pilAI allele encoding six additional C-terminal histidine residues in pUCPA1Ha, or the pilAI allele encoding six histidine residues substituting for the six C-terminal amino acids in pUCPA1Hs.

Plate transformation of the hisX1 strains was performed with 0.5 μg of chromosomal his+ DNA per assay. The experiments were performed in the presence of 1 mg of ampicillin ml−1 to select for maintenance of the pUCP-derived plasmids. The high ampicillin concentration decreased the transformability of LO15(pUCP19) about fivefold. The numbers in parentheses are transformation relative to that with LO15(pUCP19).

+, confluent lysis; −, no plaque; (+), single plaques.

−, no twitching zones after 10 days at 37°C.

Suppression of the transformation defect of a pilT mutant.

In piliated P. stutzeri cells, transformation is strictly dependent on pilT+. Since the strain Tf300(pUCPA1Hs) is transformable but does not have pili, we asked whether the transformability of this strain is still dependent on pilT. To examine this, the mutant pilT allele of strain Tf59 containing a Kmr insertion was crossed into Tf300(pUCPA1Hs) by natural transformation using Kmr for selection. In one of the transformants [Tf590 pilT::Kmr pilAI::Gmr(pUCPA1Hs)] the presence of the defective pilT allele in the chromosome was verified by PCR using primers IS50L and PilT-Pro2 (see Materials and Methods). The strain was almost as transformable as Tf300(pUCPA1Hs) and the wild-type (Table 4, compare line 7 with lines 6 and 1) and at least 1,000-fold more transformable than the pilT single mutant Tf59 (Table 4). In contrast to pUCPA1Hs, the plasmid pUCPA1, overexpressing the normal pilAI gene, did not compensate for the pilT defect (Table 4). Thus, transformation of a strain expressing the modified PilAI protein had become independent of the pilT function. Twitching motility and PO4 infection were not restored under these conditions (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

After insertional inactivation, we identified the pilT gene of P. stutzeri and showed that it is required for twitching motility, infection of cells by phage PO4, and natural transformation. The latter phenotype was attributed to the inability of the hyperpiliated cells to take up transforming DNA, although binding of DNA to the cells was not impaired. Orthologs of pilT have been found in several gram-negative bacteria, and mutations in these genes were always associated with a piliated phenotype, but with nonfunctional pili in the sense that twitching motility and social gliding were abolished. Similar to the gene order in P. aeruginosa, we found downstream of pilT the pilU gene, which is required for full transformability of P. stutzeri but is not necessary for pilus formation, twitching motility, or PO4 infection. This is in contrast to the pilU mutants of P. aeruginosa, which were still infected by PO4 but were hyperpiliated and defective for twitching motility (42). The phenotype of the pilU strain of P. aeruginosa provided evidence that twitching motility is not obligately associated with phage sensitivity and thus phage infection is not dependent on pilus function (42). PilT and PilU are homologous to components of a specialized protein assembly system widely found in eubacteria. They share a nucleotide binding domain and may be associated with the cytoplasmic membrane, although they are largely hydrophilic (8, 23, 31). The observation that the pilU gene of the nontransformable P. aeruginosa complemented the transformation defect of the pilU strain of P. stutzeri and perhaps also improved its DNA uptake (the increase was not significant) suggests that the PilU proteins in these two organisms support a pilus function that is important for DNA uptake in P. stutzeri. Previously it was found that the pilus structure proteins from nontransformable P. aeruginosa and Dichelobacter nodosus fully substituted for the pilus protein of P. stutzeri in natural transformation, twitching motility, and sensitivity to phage PO4 (16) and also supported a hypertransformation phenotype in pilAII mutants (18). It is not yet clear why the hyperpiliated pilT mutants bind DNA similarly to the wild type but do not take it up while the nonpiliated pilA and pilC strains hardly bind and do not take up DNA. Currently our hypothesis is that pilus formation is required to effectively expose a competence-specific DNA-binding protein at the cell surface and that pilus function is required for the transport of the DNA or DNA-protein complex into the periplasm (see below). In pilA and pilC mutants the specific DNA-binding protein is not exposed because of the absence of pili.

The idea of pilus extension and retraction being the basis of twitching motility was put forward by Bradley (7). The hypothesis was recently discussed by Wall and Kaiser (39), who summarized arguments for PilB (having a nucleotide binding site) along with other components of the pilus biogenesis apparatus to function in pilus extension and PilT (also having a nucleotide binding site) being a motor for retraction, perhaps along with PilU by destabilizing the pilus assembly. All of these pilus assembly factors are associated with the cytoplasm membrane or located in the cytoplasm so that both extension and retraction processes are possibly organized at the cytoplasmic membrane (15). The dynamic balance between extension and retraction could provide the force for bacterial movement (39). A role of PilT in destabilizing the pilus could also explain the hyperpiliation of pilT mutants of P. aeruginosa (7), of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 (3), and of P. stutzeri, if one assumes that in the pilT strains the balance shift towards assembly would result in the biogenesis of extra pili. In the nonhyperpiliated pilT mutants of N. gonorrhoeae, the lack of depolymerization may lead not to extra pili but only to a continual persistence of the same pili on the surface (as is presumably also the case for the other pilT mutants mentioned). Unfortunately, methods for measuring pilus turnover on the cell surface are not yet available. Other pilT mutant phenotypes described recently are compatible with a role of pilT in pilus destabilization. The pilT+ gene of N. meningitidis is necessary for the loss of pili during a late stage of epithelial cell infection, leading to an intimate attachment of bacteria (32). In N. gonorrhoeae a role of pilT in antagonizing the pilus biogenesis process was identified by showing that a loss of function mutation in pilT suppressed a defect of pilus formation caused by a pilC mutation (44). PilC is regarded as a pilus biogenesis factor and can associate with the pilus fiber tip (33, 44). Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 has two different pilT genes which are both required for phototaxis, and the loss of pilT1 rendered cells hyperpiliated and nonmobile while pilT2 mutants were mobile but negatively phototactic (3). The mechanism by which PilT controls pilus stability or dynamics remains unclear.

The involvement of pilT in DNA uptake was discovered when Wolfgang et al. (43) showed that in N. gonorrhoeae a defect in pilT abolished natural transformation and decreased the sequence-specific uptake of DNA at least 20-fold. As in N. gonorrhoeae, a pilT defect in P. stutzeri abolished transformation and strongly decreased DNA uptake. The coordinated loss of twitching motility and DNA uptake in the pilT mutants suggests a possible relationship between DNA uptake into the cell and the presumably dynamic action of pili in the surface translocation of cells. Clearly, the nontransformability of the piliated pilT strains of N. gonorrhoeae and P. stutzeri indicates that the role of pili in DNA uptake is not limited to their penetration through the outer cell wall, which could provide a gap between the pilus and the outer membrane through which DNA may reach the periplasm, as previously suggested (15). Rather, the pilT-dependent dynamic behavior of pili may be required perhaps by providing the movement towards the periplasm that could bring DNA into the cell (43). An alternative explanation for the dynamic behavior of pili effecting DNA uptake would be that pili could cause DNA influx in those moments when the pilus retraction would reach the point at which the filament disappears under the outer membrane, thereby temporarily leaving an open pore in the outer membrane which could provide the entry site for DNA. The pores through which pili extend into the exterior are formed in N. gonorrhoeae and P. aeruginosa by PilQ secretins possibly together with other proteins and are required for pilus biogenesis and in N. gonorrhoeae also for transformation (5, 13, 29). Open pores providing a free channel would not occur in pilT mutants due to the permanent presence of the pilus structure in the pore and would not exist at any time in strains deficient for pilus biogenesis (like pilAI or pilC mutants), either. These mutants are transformation deficient.

Could single pilin molecules or minimal pilin assembly structures also elicit DNA uptake? The phenotype of the P. stutzeri pilAI mutant expressing a hexahistidine substitution-tagged PilAI protein is compatible with this possibility. The strain does not form pili visible in the electron microscope and is defective for twitching motility. The strain shows, however, a marked although low plating of PO4 and a level of transformability almost as high as that of the wild-type. Several specific pilus protein mutants of N. gonorrhoeae which do not express intact pili also maintain transformability (20, 22, 46). It is possible that the histidine substitution-tagged PilAI protein can form minimal structures within the periplasm which may extend through the murein layer to the pore complex in the outer membrane. Similarly, it is possible that single pilin molecules reach the pore complex and cause the channel to be opened. The residual plating of PO4 which adsorbs to pili (6) would be more compatible with the formation of a minimal pilin assembly structure. Remarkably, the absolute transformation deficiency imposed on wild-type cells by a pilT defect is fully suppressed by the histidine tag mutation of pilAI. In the framework of the retraction hypothesis this could mean that the pilT-independent transformation results from the instability of the minimal pilin assembly structure which makes the depolymerizing activity of pilT dispensable. Alternatively, the pilT-dependent depolymerization of normal pili necessary for the outer membrane channel to be opened is not required in the mutant strain, because the minimal pilin assembly structures or single pilin molecules cause the channel to be opened without PilT action. Taken together, our observations attribute different roles to pilT+ and the pilus protein in pilus-associated functions, including twitching motility, PO4 infection, and natural transformation. The data indicate that (i) twitching motility requires normal pili plus pilT+, (ii) PO4 infection at a level of about 1% is possible in nonpiliated strains expressing a specific mutant pilus protein but then still depends on pilT+, and (iii) transformation can occur without pili in cells with a specific mutant pilus protein and then no longer requires pilT+. The minimal pilin assembly structure in the periplasm assumed here may be similar to intermediates in pilT-dependent depolymerization of pili and also to hypothetical structures formed by pilin-like proteins which do not lead to pilus formation but are essential for transformation of the gram-negative organisms Haemophilus influenzae and Acinetobacter (10, 12, 30). It is tempting to speculate that transformation of these species is not dependent on a pilT function. An ortholog of pilT was not detected in the genome sequence of H. influenzae (unpublished data) despite the presence of the type IV pilin-like biogenesis operon necessary for transformation (12). It is likely that the minimal pilin assembly structure additionally functions in other transformation-associated steps, such as the formation of a complex with the DNA receptor or the passage of DNA across the cell wall and periplasm. Structures within the cell wall formed by pilin-like proteins are also considered to have such roles in the natural transformation of gram-positive bacteria (14, 24).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. S. Mattick for providing plasmids.

This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bagdasarian M, Lurz R, Rückert B, Franklin F C H, Bagdasarian M M, Frey J, Timmis K N. Specific-purpose cloning vectors. II. Broad host range, high copy number, RSF1010-derived vectors, and a host-vector system for gene cloning in Pseudomonas. Gene. 1981;16:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker A, Schmidt M, Jager W, Pühler A. New gentamicin-resistance and lacZ promoter-probe cassettes suitable for insertion mutagenesis and generation of transcriptional fusions. Gene. 1995;162:37–39. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00313-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhaya D, Bianco N R, Bryant D, Grossman A. Type IV pilus biogenesis and motility in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:941–951. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bieber D, Ramer S W, Wu C Y, Murray W J, Tobe T, Fernandez R, Schoolnik G K. Type IV pili, transient bacterial aggregates, and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science. 1998;280:2114–2118. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bitter W, Koster M, Latijnhouwers M, de Cock H, Tommassen J. Formation of oligomeric rings by XcpQ and PilQ, which are involved in protein transport across the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:209–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradley D E. A pilus-dependent Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage with a long noncontractile tail. Virology. 1973;51:489–492. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley D E. A function of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO polar pili: twitching motility. Can J Microbiol. 1980;26:146–154. doi: 10.1139/m80-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brossay L, Paradis G, Fox R, Koomey M, Hébert J. Identification, localization, and distribution of the PilT protein in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2302–2308. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2302-2308.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruns S, Reipschläger K, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Characterization of natural transformation of the soil bacteria Pseudomonas stutzeri and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus by chromosomal and plasmid DNA. In: Gauthier M J, editor. Gene transfers and environment. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1992. pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busch S, Rosenplänter C, Averhoff B. Identification and characterization of ComE and ComF, two novel pilin-like competence factors involved in natural transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4568–4574. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4568-4574.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson C A, Pierson L S, Rosen J J, Ingraham J L. Pseudomonas stutzeri and related species undergo natural transformation. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:93–99. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.93-99.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dougherty B A, Smith H O. Identification of Haemophilus influenzae Rd transformation genes using cassette mutagenesis. Microbiology. 1999;145:401–409. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drake S L, Koomey M. The product of the pilQ gene is essential for the biogenesis of type IV pili in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:975–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.18050975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubnau D. DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999;53:217–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fussenegger M, Rudel T, Barten R, Ryll R, Meyer T F. Transformation competence and type IV pilus biogenesis in Neisseria gonorrhoeae—a review. Gene. 1997;192:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graupner S, Frey V, Hashemi R, Lorenz M G, Brandes G, Wackernagel W. Type IV pilus genes pilA and pilC of Pseudomonas stutzeri are required for natural genetic transformation, and pilA can be replaced by corresponding genes from nontransformable species. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2184–2190. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.8.2184-2190.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graupner S, Wackernagel W. Identification of multiple plasmids released from recombinant genomes of Hansenula polymorpha by transformation of Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1839–1841. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1839-1841.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graupner S, Wackernagel W. Pseudomonas stutzeri has two closely related pilA genes (type IV pilus structural protein) with opposite influences on natural genetic transformation. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:2359–2366. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.7.2359-2366.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graupner, S., and W. Wackernagel. Identification and characterization of novel competence genes comA and exbB involved in natural genetic transformation of Pseudomonas stutzeri. Res. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Haas R, Schwarz H, Meyer T F. Release of soluble pilin antigen coupled with gene conversion in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:9079–9083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrichson J. Twitching motility. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1983;37:81–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill S A, Morrison S G, Swanson J. The role of direct oligonucleotide repeats in gonococcal pilin gene variation. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1341–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobbs M, Mattick J S. Common components in the assembly of type IV fimbriae, DNA transfer systems, filamentous phage and protein secretion apparatus: a general system for the formation of surface-associated protein complexes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:233–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacks S A. DNA uptake by transformable bacteria. In: Broome-Smith J K, Baumberg S, Stirling C J, Ward F B, editors. Transport of molecules across microbial membranes. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 138–168. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazzaroni J C, Germon P, Ray M-C, Vianney A. The Tol proteins of Escherichia coli and their involvement in the uptake of biomolecules and outer membrane stability. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Natural genetic transformation of Pseudomonas stutzeri by sand-adsorbed DNA. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:380–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00276535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. High frequency of natural genetic transformation of Pseudomonas stutzeri in soil extract supplemented with a carbon/energy and phosphorus source. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1246–1251. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1246-1251.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Stimulation of natural genetic transformation of Pseudomonas stutzeri in extracts of various soils by nitrogen or phosphorus limitation and influence of temperature and pH. Microb Releases. 1992;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin P R, Hobbs M, Free P D, Yeske Y, Mattick J S. Characterization of pilQ, a new gene required for the biogenesis of type-4 fimbriae in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:857–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Porstendörfer D, Drotschmann U, Averhoff B. A novel competence gene, comP, is essential for natural transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4150–4157. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4150-4157.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pugsley A P. Superfamilies of bacterial transport systems with nucleotide binding components. In: Mohan S, Dow C, Coles J A, editors. Prokaryotic structure and function: a new perspective. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pujol C, Eugène E, Marceau M, Nassif X. The meningococcal PilT protein is required for induction of intimate attachment to epithelial cells following pilus-mediated adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4017–4022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudel T, Scheuerpflug I, Meyer T F. Neisseria PilC protein identified as type-4 pilus tip-located adhesin. Nature. 1995;373:357–359. doi: 10.1038/373357a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, manual. 2nd ed. N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schweizer H P. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene. 1991;97:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schweizer H P. Small broad-host-range gentamicin resistance gene cassettes for site-specific insertion and deletion mutagenesis. BioTechniques. 1993;15:831–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sikorski J, Graupner S, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Natural transformation of Pseudomonas stutzeri in non-sterile soil. Microbiology. 1998;144:569–576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon R, Quandt J, Klipp W. New derivatives of transposon Tn5 suitable for mobilization of replicons, generation of operon fusions and induction of genes in gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1989;80:161–169. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wall D, Kaiser D. Type IV pili and cell motility. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watson A A, Alm R A, Mattick J S. Construction of improved vectors for protein production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1996;172:163–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitchurch C B, Hobbs M, Livingston S P, Krishnapillai V, Mattick J S. Characterization of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa twitching motility gene and evidence for a specialized protein export system widespread in eubacteria. Gene. 1991;101:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90221-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitchurch C B, Mattick J S. Characterization of a gene, pilU, required for twitching motility but not phage sensitivity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1079–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfgang M, Lauer P, Park H-S, Brossay L, Hébert J, Koomey M. PilT mutations lead to simultaneous defects in competence for natural transformation and twitching motility in piliated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:321–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolfgang M, Park H-S, Hayes A F, van Putten J P M, Koomey M. Suppression of an absolute defect in type IV pilus biogenesis by loss-of-function mutations in pilT, a twitching motility gene in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14973–14978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu S S, Wu J, Kaiser D. The Myxococcus xanthus pilT locus is required for social gliding motility although pili are still produced. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:109–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1791550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Q Y, DeRyckere D, Lauer P, Koomey M. Gene conversion in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evidence for its role in pilus antigen variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5366–5370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]