Abstract

The licC gene product of Streptococcus pneumoniae was expressed and characterized. LicC is a nucleoside triphosphate transferase family member and possesses CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase activity. Phosphoethanolamine is a poor substrate. The LicC protein plays a role in the biosynthesis of the phosphocholine-derivatized cell wall constituents that are critical for cell separation and pathogenesis.

Streptococcus pneumoniae requires choline for growth, and it decorates the teichoic and lipoteichoic acids of the cell wall with this essential nutrient (5). It is established that choline metabolism plays an indispensable role in cell separation, transformation, autoloysis, and pathogenicity of S. pneumoniae. For example, the cell surface phosphocholine (P-Cho) participates in the interaction with the host surface and induces attachment and invasion (4, 15). The importance of choline in pathogenesis is not confined to S. pneumoniae but is also found in Haemophilus influenzae (9, 10, 18, 19), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (12, 17). In addition, extracellular P-Cho serves as the scaffold for a group of choline-binding proteins that are secreted from the cells and are subsequently attached to the cell surface by their homologous choline-binding domains (see reference 11 and references therein).

The pathway for choline metabolism in S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae has been hypothesized to consist of a choline transport system, choline kinase, CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (CCT), and a choline phosphotransferase that transfers P-Cho to lipoteichoic acid or lipopolysaccaride (18). The existence of this pathway is supported by the detection of choline kinase and CCT activity in crude extracts of S. pneumoniae (1, 20). Genetic elements required for choline incorporation into the lipopolysaccharide of H. influenzae are found in the lic1 locus, which contains four open reading frames. The hypothesis drawn from the bioinformatic analysis of the lic1 locus (19) is that licA corresponds to choline kinase based on a 31% identity to the choline kinase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae over the short span of 40 amino acids between residues 222 and 262. The licB gene has several predicted transmembrane domains and is thus postulated to be a choline transporter. The hydrophilic licC gene product is a candidate for the CCT due to the resemblance of its amino terminus to the amino-terminal 60 residues of nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) transferase family members, leaving the licD gene as a candidate for the choline phosphotransferase. A homologous licC gene exists in S. pneumoniae (21), and the predicted LicC proteins of H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae are 37% identical and 60% similar. There are no examples of bacterial CCTs, and both of the predicted LicC proteins lack homology to either the prototypical metazoan CCTs (7, 14) or the CTP:glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase from Bacillus subtilis (16). Rather, licC is related to members of the NTP transferase superfamily that primarily activate phosphosugars, such as galU of Escherichia coli and rmlA of P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1), opening the possibility that licC is involved in carbohydrate metabolism. The goal of this study was to determine if the licC gene encodes a novel CCT.

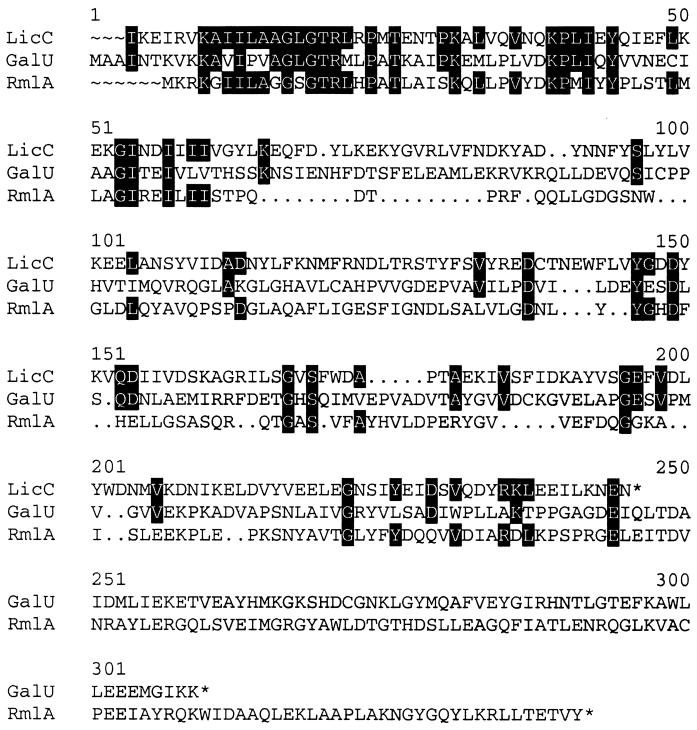

FIG. 1.

Similarity of LicC to NTP transferases. The predicted amino acid sequence of the licC gene of S. pneumoniae is aligned with the predicted amino acid sequences of the E. coli galU and P. aeruginosa rmlA genes, two nucleotidyltransferases involved in the activation of phosphosugars for the biosynthesis of cell wall polysaccharides. Identical amino acids between LicC and either of the two NTP transferases are highlighted. Members of the NTP transferase family contain the KAX5GXGTRX8PK amino-terminal motif.

Similarity of LicC to NTP transferases.

LicC is classified as a member of the NTP transferase (nucleotidyltransferase) superfamily of proteins based on the presence of the signature sequence (KAX5GXGTRX8PK) for this group of enzymes at its amino terminus. Figure 1 shows the relationship of the primary sequence of LicC to two representative members of this family, a phosphosugar uridylyltransferase (GalU) and thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) from gram-negative bacteria. LicC possessed a high degree of similarity with these two nucleotidyltransferases in the amino-terminal domain (Fig. 1). The crystal structures of members of the NTP transferase family verify that this amino-terminal sequence motif is involved in nucleotide binding (2, 3).

Expression, purification, and activity of LicC.

The licC gene was amplified using primers designed to introduce an NdeI site at the initiator codon and a BamHI site after the stop codon. The fragment was sequenced and cloned into pET-15b for expression as a His-tagged protein. The construct began at Ile1 and ended at Asn234 (Fig. 1). The construct was sequenced to verify the absence of PCR artifacts.

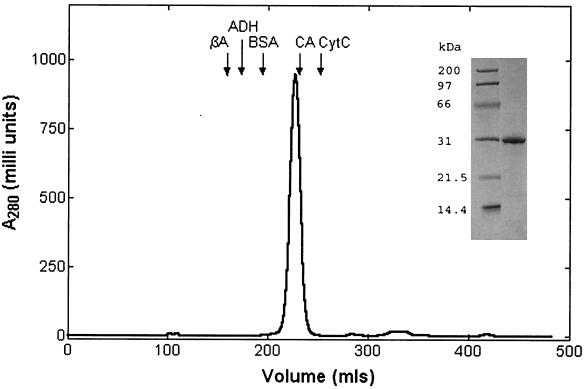

The protein was purified on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose followed by gel filtration on Superdex-200 26/60 (Fig. 2). The enzyme was homogeneous as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The apparent molecular mass calculated from the gel filtration column was 30 kDa, which agreed with the predicted molecular mass of LicC plus the His tag based on the amino acid sequence (Fig. 1). This result indicates that LicC exists as a monomer (Fig. 2). The protein was stored in 50% glycerol–20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, at −20°C and retained full activity for several months.

FIG. 2.

Purification of LicC. The His-tagged LicC protein was purified by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography as described previously (6). The protein was immediately applied to a Superdex-200 26/60 column (Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 1 mM EDTA and was eluted at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min. LicC was monitored at 280 nm and eluted at 226 ml. The molecular mass was estimated to be 30 kDa by graphic analysis of a standard curve based on the elution volumes (arrows) of protein molecular mass standards (Sigma). βA, β-amylase (200 kDa); ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa); BSA, bovine serum albumin (66 kDa); CA, carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa); CytC, cytochrome c (12.4 kDa). LicC was pure, based on analysis with a sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel followed by Coomassie blue staining (inset).

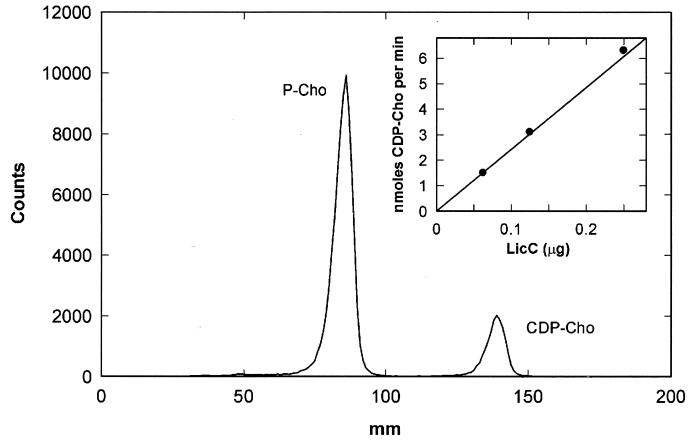

LicC catalyzed the formation of CDP-Cho as identified by thin-layer chromatography (Fig. 3). LicC cytidylyltransferase activity was linear with time and protein and exhibited a specific activity of 2.5 μmol/min/mg of protein in the standard assay conditions (Fig. 3, inset).

FIG. 3.

LicC is a CCT. The LicC assay contained 2 mM CTP, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phospho[methyl-14C]choline (specific activity of 3.68 mCi/mmol), 150 mM bis-Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and 62.5 ng of LicC in a final volume of 50 μl. LicC was added last to initiate the reaction, and after 10 min at 37°C, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 5 μl of 0.5 M EDTA. A 40-μl aliquot of the reaction mixture was applied to a preabsorbent silica gel G plate that was developed with 95% ethanol–2% ammonium hydroxide (1:1, vol/vol) (8). The single product was visualized with a Bioscan Imaging detector and migrated with authentic CDP-Cho. The formation of CDP-Cho per assay was linear with LicC (inset).

Biochemical properties.

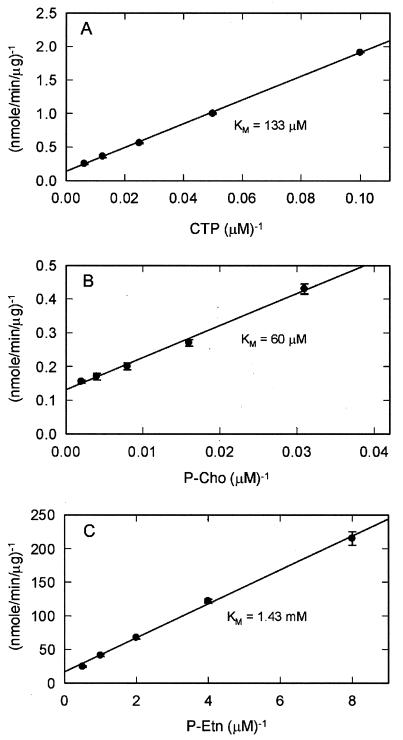

We compared the activity of LicC using either ATP, TTP, UTP, or GTP in place of CTP, all at 2 mM concentration. No activity was detected with TTP, UTP, or GTP. The activity with ATP was 0.25% of that with CTP (data not shown). The high degree of nucleotide selectivity was consistent with the identification of LicC as a cytidylyltransferase rather than another nucleotidyltransferase. The Km for CTP was 133 μM (Fig. 4A) and for P-Cho was 83 μM (Fig. 4B). In both cases, the Vmax was 7.7 ± 0.2 μmol/min/mg. There was no indication of cooperativity in the binding of either substrate consistent with LicC existing as a monomer.

FIG. 4.

Kinetic constants for LicC. The kinetic constants for the two LicC substrates are shown. Double reciprocal plots were used to calculate the apparent Km for CTP (A), P-Cho (B), and P-Etn (C) by employing the radiochemical assay described in the legend to Fig. 3. (A) The CTP Km was 133 μM measured in the presence of 1 mM P-Cho. (B) The P-Cho Km was 83 μM measured in the presence of 2 mM CTP. (C) The Km for P-Etn of 1.43 mM was determined in the presence of 2 mM CTP. Assays for CDP-Etn formation were the same as the standard assay, except that P-Etn (specific activity of 3.68 mCi/mol) was substituted for P-Cho and that the LicC concentration was 10 μg/assay. The error bars represent the range of data.

We assessed the ability of LicC to use phosphoethanolamine (P-Etn) as a substrate by substituting 1 mM P-[14C]Etn (specific activity of 3.68 mCi/mmol) for P-[14C]Cho in the standard assay described for Fig. 3 and raising the LicC concentration to 10 μg/assay. LicC was capable of utilizing P-Etn as the substrate but was much less efficient. The protein exhibited a Km of 1.43 mM for P-Etn and a Vmax with this substrate of 0.06 μmol/min/mg. Thus, LicC was able to convert P-Etn to CDP-Etn, but it used P-Etn much less efficiently as a substrate.

Conclusions. Our study establishes that the third gene in the lic1 cluster, licC, encodes a functional CCT responsible for the formation of CDP-Cho. LicC does not have similarity in primary sequence to the known metazoan CCTs and thus represents a unique member of this functional enzyme class. However, LicC is a member of the NTP transferase (nucleotidyltransferase) superfamily of enzymes that transfer the nucleoside monophosphate moiety to a phosphorylated acceptor substrate concomitant with the release of pyrophosphate (National Center for Biotechnology Information Conserved Domain Database, protein family no. 00483). The inclusion of LicC in this family is illustrated by its similarity to the amino termini of GalU and RmlA, two nucleotidyltransferases that are involved in the formation of nucleoside diphosphate-hexose derivatives that are used in the biosynthesis of cell wall components (Fig. 1). The less conserved regions in the middle of these proteins represent the substrate-binding regions. Many family members are dimers or tetramers; however, LicC appears to be a monomer, based on the results of gel filtration chromatography (Fig. 2). The structure of RmlA (2) shows that the subunit interaction surface is encoded by the carboxy-terminal domain. Interestingly, LicC is smaller than typical NTP transferases due to the lack of a carboxy-terminal tail (Fig. 1), consistent with its monomeric behavior in solution.

The biochemical properties of LicC are consistent with its proposed role in the pathway for the decoration of teichoic acids with P-Cho. Etn does replace Cho as a nutritional requirement and is incorporated to approximately the same extent into the cell wall (13). However, the replacement of Cho with Etn results in several severe phenotypic changes, including the lack of daughter cell dissociation and autolysis, resistance to deoxycholate-induced lysis, and the inability to undergo genetic transformation. Significantly, the presence of Cho in the medium completely blocks the incorporation of Etn into cell walls, illustrating that the pathway is highly selective for Cho. This physiological observation suggests that the Cho incorporation pathway is highly selective for Cho but is capable of using Etn. This conclusion is reflected in the substrate specificity of LicC, and we suggest that the other enzymes in the pathway will have the same dual specificity and Cho selectivity. The importance of choline metabolism to viability and virulence suggests that LicC would be a excellent target for the development of antibacterial therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM34496 and GM45737, Cancer Center (CORE) Support Grant CA21765, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

We thank Pam Jackson and Matthew Frank for their expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bean B, Tomasz A. Choline metabolism in pneumococci. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:571–574. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.571-574.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blankenfeldt W, Asuncion M, Lam J S, Naismith J H. The structural basis of the catalytic mechanism and regulation of glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase (RmlA) EMBO J. 2000;19:6652–6663. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown K, Pompeo F, Dixon S, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Cambillau C, Bourne Y. Crystal structure of the bifunctional N-acetylglucosamine 1-phosphate uridyltransferase from Escherichia coli: a paradigm for the related pyrophosphorylase superfamily. EMBO J. 1999;18:4096–4107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cundell D R, Gerard C, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Tuomanen E I, Gerard N P. PAF receptor anchors Streptococcus pneumoniae to activated human endothelial cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1996;416:89–94. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0179-8_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer W, Behr T, Hartmann R, Peter-Katalinic J, Egge H. Teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus pneumoniae possess identical chain structures. A reinvestigation of teichoic acid (C polysaccharide) Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:851–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath R J, Rock C O. Enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase (fabI) plays a determinant role in completing cycles of fatty acid elongation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26538–26542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalmar G B, Kay R J, Lachance A, Aebersold R, Cornell R B. Cloning and expression of rat liver CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase: an amphipathic protein that controls phosphatidylcholine synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6029–6033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lykidis A, Jackson P, Jackowski S. Lipid activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase α: characterization and identification of a second activation domain. Biochemistry. 2001;40:494–503. doi: 10.1021/bi002140r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lysenko E, Richards J C, Cox A D, Stewart A, Martin A, Kapoor M, Weiser J N. The position of phosphorylcholine on the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae affects binding and sensitivity to C-reactive protein-mediated killing. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:234–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lysenko E S, Gould J, Bals R, Wilson J M, Weiser J N. Bacterial phosphorylcholine decreases susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37/hCAP18 expressed in the upper respiratory tract. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1664–1671. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1664-1671.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novak R, Charpentier E, Braum J S, Park E, Murti S, Tuomanen E, Masure R. Extracellular targeting of choline-binding proteins in Streptococcus pneumoniae by a zinc metalloprotease. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:366–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serino L, Virji M. Phosphorylcholine decoration of lipopolysaccharide differentiates commensal Neisseriae from pathogenic strains: identification of licA-type genes in commensal Neisseriae. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1550–1559. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomasz A. Biological consequences of the replacement of choline by ethanolamine in the cell wall of Pneumococcus: chain formation, loss of transformability, and loss of autolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:86–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsukagoski Y, Nikawa J, Yamashita S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the gene encoding cholinephosphate cytidylyltransferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1987;169:477–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuomanen E I, Masure H R. Molecular and cellular biology of pneumococcal infection. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:297–308. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber C H, Park Y S, Sanker S, Kent C, Ludwig M L. A prototypical cytidylyltransferase: CTP:glycerol-3-phosphate cytidylyltransferase from Bacillus subtilis. Structure Fold Des. 1999;7:1113–1124. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiser J N, Goldberg J B, Pan N, Wilson L, Virji M. The phosphorylcholine epitope undergoes phase variation on a 43-kilodalton protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and on pili of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4263–4267. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4263-4267.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiser J N, Pan N, McGowan K L, Musher D, Martin A, Richards J. Phosphorylcholine on the lipopolysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae contributes to persistence in the respiratory tract and sensitivity to serum killing mediated by C-reactive protein. J Exp Med. 1998;187:631–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiser J N, Shchepetov M, Chong S T. Decoration of lipopolysaccharide with phosphorylcholine: a phase-variable characteristic of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1997;65:943–950. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.943-950.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whiting G C, Gillespie S H. Investigation of a choline phosphate synthesis pathway in Streptococcus pneumoniae: evidence for choline phosphate cytidylyltransferase activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;143:279–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J-R, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Fischer W, Tuomanen E I. Pneumococcal licD2 gene is involved in phosphorylcholine metabolism. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1477–1488. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]