Abstract

For young women, the power imbalance in favor of males in dating relationships has been related to dating violence (DV) victimization. In addition, the use of rumination to cope with DV may increase their psychological distress. The purpose of the current study was to examine whether experiences of DV and rumination mediate the association between power imbalance and suicide risk (SR). The sample comprised 1,216 young women aged between 18 and 28 years from Colombia (n = 461) and Spain (n = 755), in a heterosexual dating relationship, not married or cohabiting with a partner and without children. The following scales were applied: The Sexual Relationship Power Scale-Modified, The Dating Violence Questionnaire–-R (DVQ-R); Cyberdating Abuse Questionnaire, Measure of Affect Regulation Scale (MARS), and The Spanish Suicide Risk Scale. A sequential mediation paths model was tested. Results indicated that power imbalance was associated with DV victimization. Furthermore, DV was associated with more rumination, which was also linked to a greater SR in both countries. Rumination may be a mechanism through which experiences of DV victimization negatively influence mental health in young women and is an important variable related cross-culturally to SR. The findings suggest an equality approach, addressing the power imbalance in dating relationships, empowering girls to prevent DV, and teaching coping strategies for dealing with victimization and its consequences.

Keywords: power imbalance, suicide risk, dating violence victimization, rumination, cross-cultural

Introduction

Dating violence (DV) has been recognized as an important social problem in young women. DV can occur cross-modally: in-person (face to face) or via online. DV in-person refers to any type of psychological, physical, or sexual aggression by one partner toward the other, in a romantic relationship involving young people not living together who have no children in common or legal ties (Jennings et al., 2017; Shorey et al., 2008). Online DV is defined as the control, harassment, stalking, and abuse of one’s dating partner via technology, Internet, and social media (Stonard, 2021; Zweig et al., 2013). It includes control/monitoring and direct aggression behaviors (e.g., misuse of passwords and dissemination of personal information without consent) (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2018). Online DV studies are still scarce in comparison with those focusing on in-person DV (Caridade et al., 2019) and little research has examined how both type of DV victimization (in-person and online) affect young women’s health.

There is a large degree of variability in the DV rates reported in previous research, most likely due to the different methodological approaches and measures used to detect the phenomenon (Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., 2020). A literature review found that the prevalence of in-person DV victimization among young women was 41.2% for physical, 64.6% for sexual, and 95.5% for psychological violence (Rubio-Garay et al., 2017), whereas the prevalence of online DV victimization ranged from 5.8% to 92% (Caridade et al., 2019). However, evidence on the prevalence of online DV victimization is limited for non-Anglo countries, especially Colombia.

Moreover, studies have also shown that, during adolescence, women tend to suffer more severe forms of violence than men (Tutty, 2021), primarily physical DV (Smith et al., 2003) and sexual online DV victimization (Stonard, 2021), and to show severe consequences associated with suffer DV such as suicide attempt (Miranda-Mendizábal et al., 2019). For these reasons, this study will analyze the prevalence of DV victimization in-person and online in heterosexual young women from two Spanish-speaking countries.

Power Imbalance in a Relationship, DV Victimization, and Suicide Risk

One of the factors associated with suffering more DV victimization among women is a lack of power in romantic relationships. When women have lower power in a relationship, the power imbalance favors the male partner. Here, power imbalance is defined as interpersonal dominance in a romantic relationship that might be expressed in decision-making dominance and the capacity to adjust behaviors against one’s partner’s wishes to control one’s actions (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). The classical theories of power (Straus, 1976, 2006), the feminist perspectives (Dobash & Dobash, 1979) and resources (Atkinson et al., 2005), gender and power theory (Connell, 1987), and theoretical framework of social domination (Pratto & Walker, 2004) consider that power imbalances within the relationship are a cause of aggression by the intimate partner. Greater power imbalance in favor of male partner has been associated with moderate (r = .40) (e.g., slapping) and severe (r = .46) (e.g., strangling) physical DV victimization among young Chilean women (Viejo et al., 2018), as well as with psychological violence among Mexican youth (Martín-Lanas et al., 2019). Nevertheless, among African American and Hispanic girls in the United States (15–19 years), power imbalance was not related to physical DV victimization (Teitelman et al., 2008). These differences support the idea that cultural values and norms (e.g., gender inequality) may shape the way in which interpersonal power influences romantic relationships (i.e., power imbalance) (Caridade & Braga, 2020; Connolly et al., 2010).

On the other hand, DV victimization has been found to produce adverse effects such as suicide risk (SR; Roberts et al., 2003). In this sense, a meta-analytical review with seven primary studies found that SR was related to in-person DV victimization among women (Castellví et al., 2017). However, we only found one study analyzing the association between online DV and suicidal ideation among college students in the United States (Caridade et al., 2019; Gracia-Leiva et al., 2019) and few studies have explored the process that associates in-person and online DV victimization with SR in young women. In this vein, the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010) has been applied to explain SR and DV (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016). This theory postulates that frustrated interpersonal needs, such as belongingness, feeling of perceived burden, and acquired capacity to take one’s own life (induced by physical and painful experiences), would be antecedents of SR.

Therefore, this study will examine whether the relationship between power imbalance and SR is mediated by DV victimization (in-person and online) in young women from two culturally different Hispanic countries (Colombia and Spain).

DV Victimization, Rumination, and SR

The consequences of DV such as SR can vary depending on how women face the violence suffered. Previous studies have shown that young women use multiple strategies to regulate their emotions and cope with DV (Lee & Lee, 2012). Emotion regulation is the process of managing emotions (positive and negative) as how they are experienced (Gross, 2015; Puente-Martínez et al., 2018). Coping strategies are the measures taken by individuals to control and manage situations that appear to be dangerous and stressful, and include cognitive and behavioral efforts to lessen the impact of stressors (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Rumination has been defined as an emotional coping strategy that involves maintaining self-centered attention and repeatedly dwelling upon distressing experiences (Xie et al., 2019). This study focuses on an intrusive and past-oriented cognition about negative experiences (Papageorgiou & Siegle, 2003) that has been associated with perpetration DV among female students (Aracı-İyiaydın et al., 2020; Toplu-Demirtaş & Fincham, 2020) and with SR among adolescent girls (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007). Suffering DV from romantic partner is a stressful, risky, and sometimes traumatic experience (Callahan et al., 2003) that is associated with rumination. Although many studies have analyzed trauma-related rumination and its consequences on post-traumatic stress (Bishop et al., 2018; García et al., 2015), few studies have examined the use of rumination to cope with DV victimization in females’ students. In consequence, in this study, we focus on the rumination coping strategy, since it may exacerbate the distress caused by DV victimization, thereby increasing young women’s vulnerability to SR. Maybe women with more power imbalance in dating relationship (i.e., low power in the relationship), when to suffer in-person or online DV from the partner (e.g., denigration, coercion, control) may increase ruminate about: partner violent behavior, ideas of ending the relationship, the secrecy of DV victimization (Øverlien et al., 2020), whether or not to ask for help, fear of isolation and retaliation from the partner, and further violence and shame (Bundock et al., 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies linking DV victimization with rumination and mental health. Only one previous study finding that rumination may mediate between online victimization by peers and mental health problems among young women (Feinstein et al., 2014). In this study, we will explore the associations between DV victimization and SR by accounting for other factors such as rumination.

Cultural Differences in DV Victimization and Associated Factors

Research analyzing cultural influences in DV is limited, making cross-cultural comparisons difficult, especially in relation to online DV. Two systematic reviews found that more than half of the extant research into DV was conducted in the United States, with a much smaller percentage being carried out in Europe and Latin America (Caridade & Braga, 2020; Gracia-Leiva et al., 2019).

The study analyzes differences between Colombia and Spain, based on theoretical considerations, differences in gender inequality and cultural values. Latin America is one of the most unequal regions worldwide (National Institute of Forensic Medicine and Forensic Sciences, 2015) with higher levels of violence against women (United Nations Development Program, 2014), and intimate partner violence (IPV) prevalence rates (7.8%) that surpass those reported in European countries (7.1%) (Women, Peace, and Security Index, 2019–2020). Specifically, official reports state that, in Colombia, 43.3% of all victims are young (from 18 to 28 years of age) (National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, 2019), and the prevalence of DV victimization ranges between 16.9% (physical) and 50% (psychological) (Gallego et al., 2019; Pinilla et al., 2016). In Spain, DV victimization rates among young women are between 14.2% (physical) and 44% (psychological) (Ministry of Equality, 2019).

Although we will not empirically analyze both countries’ cultural values here, we will include an analysis based on theoretical considerations regarding Hofstede’s (2011) classification of cultural values (http://www.geerthofstede.nl/). This author raised four cultural values (masculinity, power distance, individualism, and uncertainly avoidance) that are expressed on a scale of 0 (small) to 100 (large). Masculinity differs men and women into distinct roles where women and their social concerns have inferior status. Power distance refers to a level of acceptance that power is distributed unequally by the members of society. High-power distance implies the acceptance of the inequality of power in society. Individualism describes the extent to which people feel independent instead of being interdependent on others. Uncertainty avoidance means people’s preference for norms and rules, stability, predictability, and low tolerance to ambiguity.

Previous research indicates certain differences between Colombia and Spain in these cultural values. Spanish people report lower power distance (57 Spain/67 Colombia) and masculinity values (42 Spain/64 Colombia), higher levels of individualism (51 Spain/13 Colombia), and more uncertainty avoidance (86 Spain/80 Colombia) than people from Colombia (Hofstede, 2011). It is worth noting that, in cultures with high power distance and high masculinity (e.g., Colombia compared to Spain), society tends to be hierarchical, stressing status, and gender differences (Arrindell et al., 2013). The belief that the distribution of male social power is inherently unequal and needs no justification may result in women believing that their partner’s behavior, even if it is abusive, is justified due to his higher status. Indeed, power may be an instrument for achieving culturally nurtured goals. Social equality (i.e., a smaller structural gender power imbalance) has been related to lower rates of IPV (Puente-Martínez et al., 2016). In contrast, in feminine societies (e.g., Spain compared to Colombia), more role equality is expected and “macho behavior” is less accepted (Arrindell et al., 2013). Moreover, in collectivist cultures, “face-saving” is essential, and people go to greater lengths to maintain a favorable judgment by others (e.g., Colombia compared to Spain). In the context of IPV, for example, this value may result in abused women being less likely to acknowledge the problem publicly or to seek help for abuse from their partners (Do et al., 2013).

Cross-cultural evidence also indicates that violence against women is one of the main precipitants of suicide attempts in developed (e.g., Spain) and low- and middle-income countries (e.g., Colombia) (Devries et al., 2011; Vijayakumar, 2015). Webster Rudmin et al. (2003) found that culture played a relevant role in causing or inhibiting suicidal thinking and behavior. These authors concluded that young women living in societies with a higher power distance value had a higher average incidence of suicide per 100,000 population (Spain with a lower power distance shows 2.3 SR rate; and Colombia with a greater power distance:2.9 SR rate). However, uncertainty avoidance was unrelated to suicide incidence, except in young women cases, in which uncertainly avoidance was a negative correlate of suicide (Webster Rudmin et al., 2003). Furthermore, high individualistic contexts that emphasize the “I” versus the “we” (i.e., the loyalty to extended family that characterizes collectivism) and high uncertainty avoidance cultures empower women. Indeed, they found that individualistic, normative (greater regulation of the rules in favor of women’s equality due to greater uncertainty avoidance) and Catholic cultures, such as Spain may reduce and protect young women from a higher SR (Webster Rudmin et al., 2003). This study suggests that even though DV may correlate positively with SR in both countries, since Colombian women live in a less egalitarian and individualistic society with more power distance and less uncertainty avoidance, their SR may be slightly higher than that of young Spanish women.

Cultural values also influence individual preferences regarding the strategies used to regulate emotions and the associated psychological outcomes (Ford & Mauss, 2015). Knyazev et al. (2017) found that rumination tended to be less commonly used in collectivistic Eastern cultures than in individualistic Western ones, since it is more centered on the inner self. However, Chang et al. (2010) found higher levels of rumination among people from collectivistic East Asian cultures than among individualistic Euro Americans, attributing this finding to the self-critical ethos of Confucian collectivism and arguing, moreover, that North American individualism stresses self-enhancement and blocks negative self-reflection. Given that the specific psychological mechanisms that explain cultural differences in the association between DV, rumination and SR are still unclear; in this study, we compare Spain and Colombia with a view to exploring this relationship.

The Current Study

The present study examines the associations between power in relationships, DV victimization (in-person and online), rumination, and SR among young women in two Ibero American cultural countries (Spain and Colombia). In this study, a number of hypotheses are put forward that apply specifically to DV because, although it shares some common risk factors and consequences with IPV (Shorey et al., 2008), it is possible to distinguish three characteristics that differentiate them. The process of power negotiation could be a more significant challenge for young couples than older ones (Ustunel, 2020). Second, no cohabitation or children in common may affect coping with violence and its consequences in DV. The attributable risk for any intimate violence exposure as a risk factor for suicide attempts was higher than the attributable risk for DV (1.99/ 1.64) (Castellví et al., 2017). Three differences have been found in coping strategies and emotional regulation according to age (Puente-Martínez et al., 2021). For these reasons, DV can be considered partially different from IPV, and this study may add new potential insights on DV victimization in young women because there is a gap in the scientific literature on how power imbalance may be related to SR through DV and rumination.

First hypothesis is proposed based on sociocultural differences between the two countries on the study variables:

Hypothesis 1a. We expect woman in countries with higher rates of inequality and violence against women, such as Colombia, to report more DV victimization (in-person and online) than woman in more egalitarian countries, such as Spain.

Hypothesis 1b. We expect young women in Colombia to report less power in their relationships and a greater SR than Spanish women, since Colombian society has stronger collectivist values and more masculinity, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance than Spanish society.

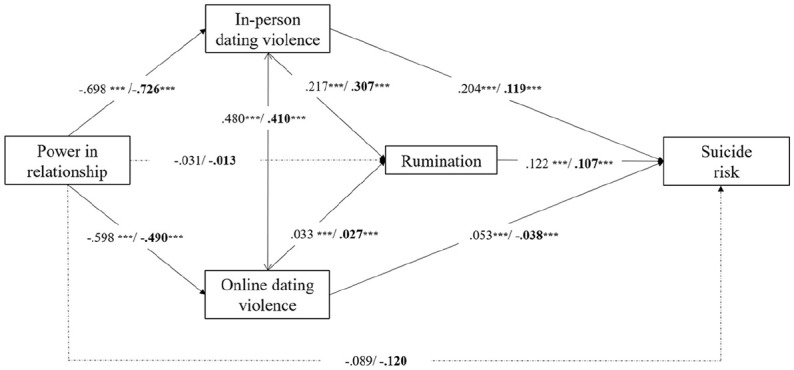

The second set of hypothesis analyzes the associations between the study variables, that is, the direct effects proposed in the relationship model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The hypothesized path models.

One-headed arrows represent paths. Hypotheses relating to indirect effect are written in bold. Hypotheses in bold represent expected indirect effects.

We expect to find a direct effect of power in relationships on in-person and online DV victimization (Hypothesis 2a), SR (Hypothesis 2b), and rumination (Hypothesis 2c). We also expect to find a direct effect of in-person and online DV on rumination (Hypothesis 2d), and SR (Hypothesis 2e), as well as a direct effect of rumination on SR (Hypothesis 2f).

The third hypothesis analyzes indirect effects of power in relationships on SR and cross-cultural differences.

Hypothesis 2g. We expect to find an indirect effect of power in relationships on SR through in-person and online DV victimization. Based on a study reporting that in-person DV has a more significant negative impact than online DV on mental health (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2020), we expect the indirect effect of in-person DV to be greater than that of online DV. Also, because physical violence may be more normalized in the Colombian context than in Spain (Martínez-Dorado et al., 2020), we expect the indirect effect of power in relationships through DV to be greater in Spain than in Colombia.

Hypothesis 2h. We expect to find an indirect effect of power in relationships on SR through in-person and online DV victimization and the use of rumination. Specifically, we expect the association between low power in relationships and SR to be stronger when young women suffer in-person and online DV and use more rumination. We expect the indirect effect of in-person DV and rumination to be greater than that of online DV. For the same reasons as stated above, we also expect this indirect effect to be greater in Spain than in Colombia.

Hypothesis 2i. We do not expect differences in the association between low relationship power and SR among women from Colombia and Spain who use rumination to cope with DV in person or online (invariance model trajectory analysis). There is a growing literature indicates that when rumination is used to cope with interpersonal violence increases adverse mental health outcomes in college students (Feinstein et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2020; Mozley et al., 2021) and women victims of domestic violence (Brown et al., 2021; Galego Carrillo et al., 2016; Ogińska-Bulik, 2016) regardless of cultural context. Thus, we expect the mechanism by which power imbalance predicts greater SR through DV and rumination to be similar in Spanish and Colombian women.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

All people who participated in the study were either in a current relationship or had been in a relationship. Participants were 1,216 young women aged between 18 and 28 years (M = 20.64, standard deviation [SD] = 2.65) from Colombia (N = 461, M = 20.82, SD = 2.55) and Spain (N = 755, M = 20.53, SD = 2.03), who are or have been in a heterosexual dating relationship, do not live with their boyfriend, and do not have children or legal ties with him. All participants were university students. Convenience samples were recruited between May 2018 and March 2020. Over 90% of participants were born in their country of residence.

In Colombia, data were collected by the Catholic University of Pereira (UCP) in collaboration with the “Higher Education Network for Gender Equity,” as part of the project entitled “Gender violence in university contexts. Study on Dating Violence.” The UCP coordinated the fieldwork at the universities. Each university determined the classes and schedules for the administration of the questionnaire. Trained research staff administered paper-and-pencil questionnaires during class hours (35–40 minutes) and the online questionnaire was disseminated through Qualtrics, with the link being sent to students’ email addresses. The Ethics Committee of the UCP approved the study (No° 2018).

In Spain, the research team contacted university professors to describe the study and ask for their collaboration. After arranging a time with participating professors, a member of the research team went to the university during class time and invited students to participate voluntarily. The questionnaires were administered at 12 universities by trained research staff. In some classes, students answered the questionnaire in paper-and-pencil format. In other cases, students who agreed to participate provided their email addresses and were then sent a link through which they could respond to the online questionnaire (30–40 minutes). In both countries, participation in the study was voluntary, and no compensation was provided. The survey link was also disseminated using the snowball procedure via the Qualtrics platform. In all cases, participants signed a consent form. The Ethics Committee of University of Burgos approved the study (IR 20/2019). OSF preregistration (osf.io/bevsu).

Measures

Sociodemographic questionnaire

Personal information was collected, including participants’ age, occupation, whether they lived with their boyfriend, and whether or not they had children or legal ties to him. These were anonymized and associated with a code to prevent the identification of cases in the data matrix. Before answering the scales, participants were instructed to answer the entire questionnaire thinking about their current or past intimate relationship.

Power in relationships

The Sexual Relationship Power Scale-Modified (Pulerwitz et al., 2000) was used to measure relational power in intimate and sexual relationships. The original scale was created in English and Spanish. The Spanish version was used here. The instrument consists of 19 items and two dimensions: Relation Control (12 items) (e.g., Most of the time, we do what my partner wants to do) is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = totally agree to 4 = totally disagree) and Decision-Making Dominance (7 items) (e.g., Who usually has more say about whether you have sex?) is rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = Your partner, 2 = Both, 3 = You). Total scores were calculated following the formula proposed by the scale’s original authors (Pulerwitz et al., 2000). Higher scores indicate greater power in relationships for women, that is, less power imbalance in favor of their male partners. Cronbach’s alphas were .90 (Colombia) and .92 (Spain).

In-person DV

The Dating Violence Questionnaire–R (DVQ-R) (Rodríguez-Díaz et al., 2017) assesses victimization and perpetration in dating relationships. We used only the victimization scale, which comprises 20 items rated on a Likert-type scale from 0 (Never) to 4 (Almost always) and grouped into five factors: detachment (e.g., stops talking to you or disappears for several days, without any explanation, to show their annoyance), humiliation (e.g., criticizes you, underestimates the way you are, or humiliates your self-esteem), coercion (e.g., talks to you about relationships he imagines you have), physical violence (e.g., has slapped your face, pushed or shaken you), and sexual violence (e.g., insists on touching you in ways and places that you don’t want). The mean was calculated by adding up all scores and dividing the total by the number of scores. Higher scores indicate greater DV victimization. Outcomes were coded as either 0: non-abusive behavior (non-victims) or 1: one or more abusive behaviors (victims) to create the prevalence scores. We used the zero-tolerance criterion (a positive response to any question on the scale is considered violence); Cronbach’s alphas were .92 (Colombia) and .90 (Spain).

Online DV

This variable was measured using the Cyberdating Abuse Questionnaire (Borrajo et al., 2015), which comprises 20 items that measure victimization in cybernetic DV. The questionnaire includes two dimensions: control and monitoring (e.g., checking social networks, WhatsApp or email without permission) and direct aggression (e.g., sending and/or uploading photos, images and/or videos with intimate or sexual content without permission). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = never to 5 = always. Total scores were calculated by adding the mean for each of the two dimensions. Higher scores indicate a greater frequency of online DV experiences. Outcomes on the CDAQ were coded as either 0: non-abusive behavior (non-victims) or 1: one or more abusive behaviors (victims) to create the prevalence scores (zero-tolerance criterion); Cronbach’s alphas were .92 in both countries (Colombia and Spain).

Suicide risk

The Spanish Suicide Risk Scale (Valladolid et al., 1998) comprises 15 items with dichotomous responses (0 = No and 1 = Yes) focusing on the symptoms of depression and hopelessness, previous autolytic attempts, suicidal ideation, and other aspects related to the risk of suicide attempts. In relation to the specific concept under study, only three items of the scale are related to suicidal ideation/ attempts: 13. Have you ever thought about suicide? 14. Have you ever told anyone that you would take your own life? and 15. Have you ever tried to take your own life? (Gracia-Leiva et al., 2020). Total SR scores were calculated by adding the scores for these three items, with higher scores indicating more SR ideation/attempts; Cronbach’s alphas were .79 (Colombia) and .78 (Spain).

Rumination

We used the Measure of Affect Regulation Scale (MARS) (Larsen & Prizmic, 2004; Puente-Martínez et al., 2018) to measure the mood or emotional intensity of experiences and how participants coped with them. Specifically, we used two items on rumination that describe a negative form of attentional and cognitive coping (“I tried to understand my feelings by thinking about and analyzing them” and “I thought about how I could have done things differently”). Response options range from 0 = never to 6 = always. High scores indicate a greater use of this coping strategy. The inter-item correlation in both countries was .40.

Data Analysis Plan

Participants’ demographic data were summarized by country using descriptive statistics. Cronbach’s alpha was used to report the reliability of all scales, with the exception of that measuring rumination (two-item scale). The reason for this was that, since the alpha coefficient is sensitive to the number of items in the scale, in this case it was deemed more appropriate to report the mean inter-item correlation. In accordance with Pallant’s (2011) recommendation, the optimal range for inter-item correlation is between .2 and .4.

Power levels in relationships, in-person and online DV, rumination, and SR in Spain and Colombia were compared using analyses of variance (H1a, H1b) (see Table 1). The relationship between variables was tested using partial Pearson correlations in each country. We also controlled for variables (procedure: paper or online) that were significantly associated with our dependent variable (SR) (see Table 2). r values of around .10 are considered small, .30 medium, and .50 or higher large (Cohen, 1988). All significance tests were two-sided with a 5% level of significance. These analyses were conducted using the SPSS v.26.

Table 1.

Means (SD) for Power in Relationships, DV (In-Person, Online), Psychological Rumination, and SR.

| Total N = 1,216 |

Colombia n = 461 |

Spain n = 755 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | F | Sig. | d | 95% CI | |

| Power | 2.92 (0.59) | 2.82 (.58) | 2.98 (0.59) | 18.832 | .0001 | 0.25 | 0.140–0.372 |

| In-person DV | 2.35 (2.74) | 2.91 (3.08) | 2.01 (2.46) | 31.849 | .0001 | 0.33 | 0.217–0.450 |

| Online DV | 0.78 (1.17) | 0.83 (3.08) | 0.76 (1.16) | 0.922 | .337 | 0.05 | −0.059–0.172 |

| Rumination | 3.49 (1.38) | 3.49 (1.51) | 3.50 (1.30) | 0.003 | .958 | 0.06 | −0.058–0.173 |

| SR | 0.53 (0.84) | 0.79 (1.08) | 0.36 (0.81) | 60.968 | .0001 | 0.46 | 0.344–0.578 |

Note: DV = dating violence; CI = confidence interval; SD = standard deviation; SR = suicide risk (3 items). Bold values represent statistically significant p ≤ .05.

Table 2.

Partial Correlations Between Power in Relationships, DV (In-Person and Online), Rumination, and SR in Colombia and Spain.

| Colombia/Spain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Power in Relationships | −.716*** | −.642*** | −.209*** | −.295*** | |

| 2. In-person DV | −.690*** | .683*** | .262*** | .355*** | |

| 3. Online DV | −.469*** | .660*** | .228*** | .221*** | |

| 4. Rumination | −.227*** | .346*** | .256*** | .121** | |

| 5. SR | −.249*** | .269*** | .140* | .181*** |

Note. Control variable: procedure. Coefficients above the diagonal are for Spain, coefficients below the diagonal are for Colombia. DV = dating violence; SR = suicide risk.

p ≤ .0001, **p ≤ .001, *p ≤ .05.

Path analysis was used to examine the pathways from power in relationships to SR in both countries. This technique allows a series of structural regression equations to be analyzed simultaneously while evaluating how well the overall model fits the data. We developed models to assess H2 (2a, 2b, 2c, 2d, 2e, 2f, 2g, and 2h). All models were developed for both types of procedure (online and paper). Next, as described by MacKinnon et al., (2004), bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) were used to provide more accurate weightings between type I and type II errors and a more precise assessment of indirect effects than those offered by traditional tests (BOOTSTRAP). Consequently, 10,000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected CIs were used to determine the significance of indirect effects. An indirect effect is deemed statistically significant if the value of 0 is not included in the bias-corrected CI. Figure 1 shows the multigroup model (1 = Spain, 2 = Colombia) pertaining to the effect of power in relationships on SR. The full model includes power in relationships as an independent variable and SR as an outcome variable. The complete mediation effect is indicated, along with the indirect paths to dependent variables through the mediators (i.e., in-person and online DV, rumination), which are represented in the form of lines charting direct paths from independent to dependent variables. The goodness of fit of the path models was assessed by examining the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) (close to or smaller than 0.08), the comparative fit index (CFI) (close to or larger than 0.95), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) (close to or larger than 0.90). These analyses were conducted using Mplus (Version 8.2, Muthén & Muthén, 2017). We then compared the indirect effects of the model, using Macro excel (Giner-Sorolla, 2020) to calculate the beta contrast (H2g and H2h).

We used a multiple group analysis to explore whether the path coefficients of the model were equivalent across countries (H2i). First, we tested the overall model and the model for each group (country) separately. Second, we tested the configural invariance model, which implies that the relations of fixed and free parameters were equivalent across subsamples (e.g., Kline, 2005), using a sequential constraint imposition model (Mann et al., 2009). This analysis involved three steps: (1) we imposed the constraint that all parameters had to be equal across the groups. If the χ2 is significant, results indicate non-invariance between groups or that path coefficients are different across countries; (2) next, we imposed a constraint on each parameter (k) of theoretical interest and then released them one at a time (k − 1); and (3) we analyzed whether any variations existed in the sequential constraint model in comparison with an unconstrained model. A variation in the sequential constraint release model enables the actual decrease in the model χ2 to be used to determine the degree of model improvement due to each individual constraint’s release. Significant comparisons using the corrected chi-square difference test indicate that this constraint increases chi-square values significantly, and therefore, a path coefficient is moderated or not equal across countries.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Means Differences by Country

The mean age of participants in Colombia (M = 20.82, SD = 2.55) was higher than in Spain (M = 20.53, SD = 2.03) (F(1,1214) = 4.923, p = .027), with a small effect size d = .13 (95% CI: 0.015, 0.247). None reported having children or legal ties to their boyfriend. 69.9% (n = 813) had a current dating relationship, and 32.7% (n = 395) had a dating relationship in the past (n = 8 missing values). No differences were found in “current partner” versus “past partner” in the study variables. Descriptive information pertaining to the study variables is presented in Table 1. Significant differences between countries were found in relationship power, in-person DV, and SR. Women in Spain reported greater power in relationships (i.e., less power imbalance), less in-person DV, and a lower SR than their counterparts in Colombia, with small effect sizes (.25 to .46) (H1a and H1b).

Overall, 78.4% of participants reported having suffered in-person DV in Spain compared to 87% in Colombia (χ2 = 16.626, p = .0001). Also, results revealed differences in SR between the two countries, with 20.3% of participants in Spain versus 39.5% in Colombia (χ2 = 54.458, p = .0001) reporting suicidal ideation; 10.2% versus 23%, respectively (χ2 = 37.292, p = .0001) having talked to someone about suicide, and 6.5% versus 7%, respectively, reporting a suicide attempt (χ2 = 31.458, p = .0001).

Correlations Between Variables

The correlation matrix among variables for each country is presented in Table 2. Power in relationships was negatively associated with DV (in-person and online), with a large effect size in both countries, with the exception of online DV in Colombia, which had a medium effect size. Power in relationships was also negatively associated with rumination and SR in both countries, with a small effect size.

In-person and online DV were found to positively correlate with each other in both countries, with a large effect size. DV was positively associated with rumination, with a small effect size, with the exception of in-person DV in Colombia, which had a medium effect size. SR was positively associated with rumination and DV (both types), with a small effect size in both countries; however, the association between SR and in-person DV in Spain was found to have a medium effect size.

Path Model

First, we tested the overall path analysis model combining both samples (Colombia and Spain). The fit of the data was good: CFI = .99, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI [.034, .075]), and SRMR = 0.023. Second, we tested the model fit for each sample separately, with both models being found to have good values: Spain: CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .036 (95% CI [.000, .069]), and SRMR = .017; and Colombia: CFI = .98, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .072 (95% CI [.036, .111]), and SRMR = .033.

Third, we explored whether the path coefficients of the model were equivalent across countries, using a multiple group analysis. The hypothesized multigroup model was found to have a good fit, with CFI = .98, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .066 (95% CI [.046, .086]), and SRMR = .033. In both countries, direct effects revealed that low power in relationships increased in-person and online DV (H2a), although it did not increase either SR (H2b) or rumination (H2c). For its part, DV significantly increased rumination (H2d) and SR (H2e). However, the association between in-person DV and SR was significant only in Spain, not in Colombia. Rumination was associated with an increase in SR (H2f).

Finally, we examined the indirect effects of power in relationships on SR. Online DV was found to mediate the relationship between power in relationships and SR in both countries, although in-person DV was only significant in the case of Spain (H2g). After incorporating rumination into our model, the sequential indirect effects (through in-person and online DV and rumination) of power in relationships on SR were also significant (H2h) (See Table 3). This indicates that the association between power in relationships and SR increased when young women experienced more in-person and online DV and used more rumination (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Summary of Indirect Effects of Power in Relationships on SR (n = 1,216).

| Indirect Effects | Estimate | Coefficients | p Value | BC 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | Z | ||||

| Indirect Effects of Power in Relationships on SR: Spain | |||||

| Power → Inp DV → SR | −0.142 | 0.045 | −3.152 | 0.002 | −0.219, −0.067 |

| Power → On DV → SR | −0.031 | 0.005 | −6.642 | 0.000 | −0.041, −0.025 |

| Power → Rum → SR | −0.004 | 0.007 | −0.546 | 0.585 | −0.014, 0.009 |

| Power → Inp DV → Rum → SR | −0.018 | 0.005 | −3.699 | 0.000 | −0.026, −0.009 |

| Power → On DV → Rum → SR | −0.002 | 0.001 | −3.890 | 0.000 | −0.004, −0.001 |

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.198 | 0.045 | −4.419 | 0.000 | −0.267, −0.122 |

| Indirect Effects of Power in Relationships on SR: Colombia | |||||

| Power → Inp DV → SR | −0.086 | 0.050 | −1.731 | 0.084 | −0.160, 0.010 |

| Power → On DV → SR | −0.018 | 0.003 | −5.340 | 0.000 | −0.024, −0.013 |

| Power → Rum→ SR | −0.001 | 0.007 | −0.196 | 0.845 | −0.011, 0.011 |

| Power → Inp DV→ Rum→ SR | −0.024 | 0.006 | −4.291 | 0.000 | −0.035, −0.014 |

| Power → On DV → Rum→ SR | −0.001 | 0.000 | −3.465 | 0.001 | −0.002, −0.001 |

| Total Indirect Effect | −0.131 | 0.049 | −2.686 | 0.007 | −0.215, −0.050 |

| Contrast of Indirect Effects of Power in Relationships on SR | |||||

| Spain: Power → Inp DV vs. On DV→ SR | −2.451 | 0.014 | |||

| Spain: Power → Inp DV vs. On DV→ Rum → SR | −3.137 | 0.001 | |||

| Colombia: Power → Inp DV vs. On DV → SR | −1.357 | 0.174 | |||

| Colombia: Power → Inp DV vs. On DV →Rum → SR | −3.833 | 0.0001 | |||

| Spain vs. Colombia | |||||

| Power → Inp DV→ SR | −0.832 | 0.405 | |||

| Power → On DV→ SR | −2.229 | 0.025 | |||

| Power → Inp DV → Rum → SR | 0.768 | 0.442 | |||

| Power → On DV→ Rum → SR | −1.00 | 0.317 | |||

| Total Indirect Effect | −1.00 | 0.313 | |||

Note. BC = bias corrected by bootstrapping; CI = confidence interval; DV = dating violence; Power = power in relationships; Inp DV = in-person DV; On DV = online DV; Rum = rumination; SE = standard error; SR = suicide risk. Significant coefficients are written in bold (p ≤ .05).

Figure 2.

Path diagram of associations tested.

One-headed arrows represent tested paths. Numbers are listed as standardized coefficients for participants in Spain/Colombia. Coefficients for Colombia are written in bold. The symbol for each parameter estimate presented is given beside the relevant arrow. ***p ≤ .0001, **p ≤ .001, *p ≤ .05.

We also compared the indirect effects of the model, with the results revealing that, in Spain, the indirect effect of power in relationships on SR through in-person DV was greater than through online DV. The indirect effect of power in relationships on SR through online DV was greater in Spain than in Colombia (H2g). Finally, in both countries, the indirect effect of power in relationships on SR through in-person DV and rumination was greater than through online DV and rumination (H2h).

Path Analysis Invariance Testing

The results of the path analysis invariance testing (H2i) are presented below: (1) We tested the configural invariance of the model. The configural invariance was significant (Colombia: χ2 = 29.918; Spain: χ2 = 17.288, χ2(13) = 47.206, p = .0001), thereby indicating that the structures of the paths or patterns of fixed and free parameters were not equivalent across subsamples. (2) Next, we tested the invariance of paths coefficients (Spain: χ2 = 21.979, Colombia: 54.517, χ2 = 76.496, df. 16, p = .0001). The imposition of this constriction increased the chi-square value significantly (Satorra Bentler Scaled, Δχ2 Difference = 29.29, df. 3, p = .0001), suggesting that path coefficients are not equal across countries. (3) Finally, to understand which path coefficients differ across countries, we analyzed the sequential constraint imposition and release model. The chi-square difference test revealed significant differences between Spain and Colombia when the effect of power in relationships on online DV (Δχ2 = 23.40, degree of freedom [df] . 1, p = .0001) and in-person DV (Δχ2 = 23.28, df. 1, p = .0001) was released (see also Figure 1), as well as in the path coefficients between in-person and online DV (Δχ2 = 19.37, df. 1, p = .0001). These results suggest that the coefficient of power imbalance on in-person DV is higher in Colombia than in Spain, and the coefficient of power imbalance on online DV is higher in Spain than in Colombia. The association between in-person and online DV is stronger in Spain than in Colombia.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the influence of power imbalance in young women’s dating relationships on DV victimization, rumination, and SR in Colombia and Spain. We found that DV experiences and the use of rumination to cope with DV mediate the relationship between power imbalance and SR among young women. Given the consequences of DV and young women’s lower power level in relationships on mental health, our findings suggest the need to intervene early with adolescents to prevent both in-person and online DV victimization.

The results of our study partially confirmed our first hypothesis (H1a and H1b), revealing that young women in Colombia perceived more loss of power (i.e., more power imbalance in favor male partners), reported higher levels of in-person DV, and had a higher SR than their counterparts in Spain. Nevertheless, online violence and rumination levels did not differ between the two countries. Regarding H1a, our results for in-person DV are consistent with those reported previously in the literature, which indicate that mid-level income countries, such as Colombia, have high rates of DV victimization and aggression (Spriggs et al., 2009). Moreover, Colombia is a country that has gone through an armed conflict and is currently in a period of post-conflict in which, in general, violence against women is legitimized (Kreft, 2020). This situation is further compounded by the polarization of gender roles that frequently occurs during armed conflicts, in which the image of masculinity is reinforced, encouraging aggressive and misogynistic behavior (Wright, 2014). In this sense, a study by Stark et al. (2017) found that intimate relationships may be the primary risk factor for violent experiences among adolescents in conflict settings. Indeed, having a boyfriend was a consistent predictor of sexual violence, even adjusting for risk factors and violence in other situations.

In relation to H1b, Colombian women perceived a lower power in their dating relationship, more fear and insecurity in making decisions and a stronger sense of both lack of freedom and entrapment within the romantic relationship than Spanish women. The difference between the two countries may be due to the fact that, during adolescence, the environment, social institutions, value systems, and social norms all have a crucial influence on romantic relationships. Colombia has a high gender gap, and this society is characterized by having a culture with a greater power distance. In general, women socially accept an unequal power distribution in the society between men and women and stronger masculinity values. These aspects may contribute to diminish the personal power held by women in romantic relationships and increase violence against women. Moreover, in the region in which data were collected, drug trafficking (Truth Commission, Colombia, 2020) and narcoculture (i.e., men being hypermasculine and exalting their power) may also foster and promote more disempowerment among women and more DV victimization (Miranda Yanes & Valdes Salas, 2019).

Regarding this same hypothesis, our findings also indicate that women in Spain had a lower SR than their counterparts in Colombia. According to Webster-Rudmin et al. (2003), while power distance is a risk factor for suicide among young women, individualism may act as a protective factor. Congruently, values in Spain tend to prioritize the growth of women’s autonomy and to reaffirm them as more independent and capable. Indeed, women who take themselves as a reference and prioritize their own goals and interests over the needs of the group (extended family) may have a lower SR. Also, individualism is contrary to some of the hegemonic values that have been established in Latin America for women, where the female identity is strongly Marianist, that is, mainly associated with modesty and submissiveness. According to Lagarde (2016), women in Latin America have built their female identity on the basis of being there for others, which in turn leads to women having less autonomy and less power over themselves and their lives than men. Moreover, endorsement of Marianist beliefs has been associated with DV victimization among Latino girls (Boyce et al., 2020). In short, these findings imply that cultural aspects, such as greater social inequality and gender power imbalance, impact negatively on romantic relationships and the prevalence and psychological consequences of DV. This cultural pattern is similar to that found among adult women who suffer IPV (Puente-Martínez et al., 2016).

The results of the path analysis extend previous correlational results, revealing that the associations between the two types of DV victimization are strong in both countries. As previous literature indicates, young women who experience one form of IPV are at risk of experiencing other types of aggression (Marganski & Melander, 2018). Also, the results of the path analysis confirm that loss of power in relationships increases the risk of suffering in-person and online DV in both countries (H2a). However, power in relationships was not found to have a direct effect on either SR (H2b) or rumination (H2c), despite the presence of a significant correlation. Moreover, results confirmed that women who experienced in-person and online DV used more rumination (H2d) and reported a greater SR (H2e) (Cava et al., 2020; Husin & Khairunnizam, 2020), the only exception being the association between in-person DV and SR in Colombia, which was not significant. Our results also confirmed that rumination increased SR in both countries (H2f). This is consistent with the results of the meta-analysis carried out by Schäfer et al. (2017), which confirmed the relationship between rumination and anxiety and depressive symptoms. These results seem to indicate that the negative consequences of DV extend beyond mental health problems through a greater use of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (i.e., ruminative coping strategies).

Furthermore, as hypothesized, online DV was a significant mediator between loss of power in relationships and a greater SR in both countries. However, in-person DV was only found to mediate significantly between these variables in Spain (H2g). These results may be partially explained by a stronger tendency among Colombian youths than among Spanish ones to normalize in-person DV (explicit violence such physical violence) (Martínez-Dorado et al., 2020). The ingrained nature of gender violence in Colombian society, legitimized by prevailing sociocultural norms, encourages victims to accept it as irremediable (Butler, 2011). It may be that suffering in-person DV does not necessarily strengthen the association between power imbalance and SR among young Colombian women. When we compared the indirect effects, we found that, in Spain only, in-person DV had a stronger influence on SR than online DV (when women experienced a loss of control in their relationships). Unlike online DV, in-person DV includes physical and sexual violence dimensions. According to the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010), all types of DV may increase feelings of perceived burden (feelings of responsibility and self-hatred) and the frustrated need to belong (feelings of loneliness and low mutual attention), both of which are antecedents to suicidal ideation; however, acquired suicidality may simply be increased by suffering physical and sexual in-person DV. Physical and sexual abuse can result in women getting used to fear of self-harm and developing a greater tolerance for pain. This may explain why SR increases more in Spain than in Colombia when there is an imbalance of power, and more in the case of in-person than online DV. However, the indirect effects of power imbalance on SR through online DV were stronger in Spain than in Colombia. One possible explanation is that in Colombian culture, power imbalance (control and domination of the female partner) is consubstantial to dating relationships. Dating relationships are more serious in that country than in Spain; boyfriends involve their families in their relationships and couples spend most of their free time together, with few independent spaces. It may be that, in Colombia, male partners are expected to control and monitor their female partners online, and this behavior is not necessarily viewed as violence and does not generate discomfort. In Spain, on the other hand, online control and monitoring by boyfriends is becoming increasingly less normalized and socially reproved. Indeed, it is a behavior that can be reported to the government organizations for women and to the police and which generates more discomfort and stress, and increased SR.

When rumination was added to the model, the results confirmed that it is a coping strategy through which negative experiences of DV influence mental health problems in both countries (more strongly in the case of in-person DV than online DV) (H2h). Lower levels of power in relationships may therefore be associated with DV and feeling more trapped in romantic relationships. Lack of hope and perceptions of entrapment have been found to intensify the association between rumination and increased suicidal ideation/suicide attempts (Law & Tucker, 2018). Given that DV is associated with rumination, and that this strategy has consistently been linked to depressive symptoms (Schäfer et al., 2017; Takano & Tanno, 2009), our results suggest that rumination may act as a mechanism through which powerlessness in relationships exacerbates SR among young female victims of DV. Similarly, other studies have confirmed that rumination acts as a mediator between negative affect and suicide attempts (Rubio et al., 2020). In this study, in-person DV was also the most common form of DV experienced in both countries; thus, these results may also be explained by the differential effect of in-person and online victimization rates.

Hypothesis H2i (invariance model) was also partially confirmed. Although the proposed model and path coefficient revealed similar effects in both countries, some differences were observed. For example, the invariance model revealed that the effect of power imbalance on in-person DV is greater in Colombia than in Spain, whereas its effect on online DV is greater in Spain than in Colombia. This may suggest that loss of power in a relationship has a greater negative impact on online DV in more egalitarian and individualistic societies. In the Colombian context, greater power imbalance may reinforce men’s dominance in romantic relationships, thereby rendering it unnecessary for them to resort to online DV. Alternatively, it may be that, in Colombian culture, control and monitoring are exercised in a more direct and implicit manner. Also, online violence (through the Internet or cell phones) may be more socially acceptable for women than for “masculine” men.

The present study has some limitations which should be taken into consideration. First, although an alternative model has been evaluated to postulate causal relations (e.g., power imbalance → rumination → DV in person and online → risk of suicide: CFI = .88, TLI = .775, RMSEA = .137, SRMR = 0.074), the study cannot test the directionality of the association between variables. In the path model, it is assumed that there is only one-way causal flow (a variable cannot be both a cause and an effect of another variable), but the assumption of causal inference in these models may not be valid. Second, data were gathered using retrospective self-reports, and both social desirability and bias recall may have affected the results. Third, suicide attempts were assessed retrospectively. Consequently, although the present data allow us to draw conclusions about the relationship between rumination and SR in Colombia and Spain, we cannot draw conclusions about the risk of future suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Fourth, our measure of SR was very restrictive and included only three items, so it is only to be expected that the ratios and coefficient values found were low. Fifth, in Colombia, the procedure to collect data (paper vs. online application of the questionnaire) was found to influence SR reports, and the effect of this variable on SR was therefore controlled. Nevertheless, it is possible that the procedure may have affected the results of the model. Sixth, participants’ exposure to other forms of violence against women outside DV was not explored. Foshee et al. (2001) argue that exposure to other forms of interpersonal violence can increase SR. Neither did we inquire about history of mental disorders which has also been associated with SR (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016). Seventh participants in Colombia could show lower socioeconomic status and find more barriers to access to formal resources than in Spain, increasing SR rates. Future studies could address these related factors. Eighth, our findings may also be influenced by the fact that, in Spain, governmental and educational institutions have developed diverse support resources for the primary and secondary prevention of DV (both in-person and online), whereas DV prevention programs at early ages are scarce in Colombia (Garzón Segura & Carcedo González, 2020), and an online DV review found that online DV prevention programs targeted at young and adolescent couples are still limited (Galende et al., 2020). Finally, although the scales included in the study have scientific guarantees of being valid and reliable, it would be necessary to examine the invariance of the instruments across cultures in future studies.

Despite these limitations, the present findings have potentially implications to prevent DV victimization. Our research helps clarify that a lack of power in the relationship may impede the ability to avoid DV, and how certain aspects of emotion regulation may lead to SR through specific cognitive mechanisms such as rumination among female victims of DV. During adolescence, gender role differentiation intensifies (Moolman et al., 2020). This life stage is an opportunity to promote power balance adjustment in dating relationships and prevent DV behaviors. However, that power loss does not have a direct effect on rumination could mean that women are not reflecting on the power difference per se. It appears that women do not identify the loss of power within the relationship as a problem. Therefore, first, interventions should address the identification of inequality and power imbalance in relationships as a risk factor for DV. Second, our findings suggest that in couples where the power imbalance (in favor of men) is high, it would be appropriate to promote women’s self-empowerment. Nevertheless, sometimes when women change and adopt more egalitarian attitudes in their relationships and have dominant males’ partner, violence toward them could appear or may increase (Karakurt & Cumbie, 2012). Thus, the development of gender-transformative programs (aiming to rework harmful gender roles) that promote non-hegemonic masculinity, non-violent values, and equality norms in dating relationships can be helpful. Likewise, educational programs with a critical view on unequal romantic love models may, promote a change in attitudes or on traditional gender roles and reduce DV. We suggest including men in the solution to this problem and offering a space for adolescents and young men who seek guidance about DV. Third, when DV appears, the use of rumination about feelings of fear, shame, and guilt associated with DV that inhibit help-seeking intentions should be reduced (Padilla-Medina et al., 2021). Women should be provided with other cognitive strategies more useful for coping with DV experiences such as, for example, cognitive reappraisal or seeking social support. It is important to show them the benefits of seeking social support among peers and trusted adults in their mental health, especially if they decide to break or end the relationship. At a community level, interventions focused on the power imbalance, through women’s sexual empowerment, have effectively increased women’s control over their sexuality with positive effects on their sexual health (Semahegn et al., 2019; Wingood & DiClemente, 2000). Empowering young women is “a matter of safety to avoid harm in intimate relationships during this life stage, and developing knowledge, attitudes, and behavior for safety throughout their entire life span” (Moolman et al., 2020). Education and healthcare professionals, social welfare workers, and counselors could provide young women with the tools they need to prevent power imbalances in their romantic relationships and DV.

All these measures would be more effective if integrated approaches are taken so that the protection, assistance, and empowerment of women are also promoted at the political and legal levels. In fact, the provision of resources for the prevention of DV and its consequences depends to a large extent on the potential impact of specific measures and resources derived from the rules established by the existing policy and legal framework. At the policy level, it is suggested to invest resources in preventing DV offline and online in educational spaces. It is advisable to develop policies that help improve the actions of the legal system and cultural awareness to promote women’s empowerment. In addition, to advance in legal protection of young women victims of DV and provide adequate and accessible therapeutic programs for young men who assault.

Author Biographies

Marcela Gracia Leiva is a Ph.D. in Social Psychology, University of the Basque Country, Spain. Her research focuses on social psychology, dating violence, and gender-based violence prevention.

Silvia Ubillos Landa, Ph.D., is a Tenured Associate Professor at the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Burgos, Spain. Her research focuses on gender-based violence, addressing the use of coping strategies and emotion regulation mechanisms as protection and risk factors for women’s mental health. Her interest is to guide political decision-making to transfer research results to the applied field.

Alicia Puente Martínez, Ph.D., is a Professor at the Faculty of Psychology, University of Salamanca, Spain. Her research focuses on social psychology, culture, emotion regulation, and well-being, particularly coping and emotion regulation among victims of gender violence.

Gina M. Arias-Rodríguez, Ph.D., is a Professor at the Catholic University of Pereira, Colombia. Her research focuses on victimization and coping among women in the Colombian armed conflict and Gender-Based Violence at university. She is interested in helping to shape public policies on Gender Equity, Human Rights, and Peace.

Lucy Nieto Betancurt is a Professor at the Catholic University of Pereira and a Ph.D. student studying Health at the University of Valle, Colombia. Her research focuses on community strategies and critical approaches to interventions in mental health, life, and gender.

Mª José Toba Lasso has a Master’s degree in Social Sciences (University of Caldas, Colombia). Her interests focus on gender violence, armed conflict, and peacebuilding. She is working with Ruta Pacífica de las Mujeres and Feminist School Guadalupe Zapata.

Darío Páez Rovira, Ph.D., is a Full Professor of Social Psychology at the University of the Basque Country, Spain. He is currently working on the impact of collective violence on culture, as well as on collective processes of coping with traumatic political events.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This research was funded by CONICYT, Chile/2017, grant number 72180394, awarded to Marcela Gracia Leiva. This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Innovation and Science, Spain (MCIN/ AEI/10.13039/501100011033/) [PID2020-116658GB-I00PSI], and is part of the I+D+i project PSI2017-84145-P; by grant 2019/00184/001, awarded by the Regional Government of Castilla y León (Spain) to the Social Inclusion and Quality of Life research group; by grant awarded by the Basque Government Ref. GIC12/91 IT–666–13 and Ref. IT1187-19 to the Culture, Cognition and Emotion research group.

ORCID iD: Marcela Gracia-Leiva  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5336-5407

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5336-5407

References

- Aracı-İyiaydın A., Toplu-Demirtaş E., Akçabozan-Kayabol N. B., Fincham F. D. (2020). I ruminate therefore I violate: The tainted love of anxiously attached and jealous partners. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10), NP7128–NP7155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrindell W. A., van Well S., Kolk A. M., Barelds D. P., Oei T. P., Lau P. Y. & Cultural Clinical Psychology Study Group. (2013). Higher levels of masculine gender role stress in masculine than in feminine nations: A thirteen-nations study. Cross-Cultural Research, 47(1), 51–67. 10.1177/1069397112470366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson M. P., Greenstein T. N., Lang M. M. (2005). For women, breadwinning can be dangerous: Gendered resource theory and wife abuse. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(5), 1137–1148. https://doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00206. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop L. S., Ameral V. E., Palm Reed K. M. (2018). The impact of experiential avoidance and event centrality in trauma-related rumination and posttraumatic stress. Behavior Modification, 42(6), 815–837. 10.1177/0145445517747287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrajo E., Gámez-Guadix M., Calvete E. (2015). Cyber dating abuse: Prevalence, context, and relationship with offline dating aggression. Psychological Reports, 116, 565–585. 10.2466/21.16.PR0.116k22w4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce S. C., Deardorff J., Minnis A. M. (2020). Relationship factors associated with early adolescent dating violence victimization and perpetration among Latinx youth in an agricultural community. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11–12), NP9214–NP9248. 10.1177/0886260520980396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown W. J., Hetzel-Riggin M. D., Mitchell M. A., Bruce S. E. (2021). Rumination mediates the relationship between negative affect and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in female interpersonal trauma survivors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(13–14), 6418–6439. 10.1177/0886260518818434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bundock K., Chan C., Hewitt O. (2020). Adolescents’ help-seeking behavior and intentions following adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(2), 350–366. 10.1177/1524838018770412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. (2011). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of sex. Routledge Classics [Google Scholar]

- Callahan M. R., Tolman R. M., Saunders D. G. (2003). Adolescent dating violence victimization and psychological well-being. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18(6), 664–681. 10.1177/0743558403254784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caridade S., Braga T., Borrajo E. (2019). Cyber dating abuse (CDA): Evidence from a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48, 152–168. 10.1016/j.avb.2019.08.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caridade S. M. M., Braga T. (2020). Youth cyber dating abuse: A meta-analysis of risk and protective factors. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(3), 2. 10.5817/CP2020-3-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castellví P., Miranda-Mendizábal A., Parés-Badell O., Almenara J., Alonso I., Blasco M. J., Cebrià A., Gabilondo A., Gili M., Lagares C., Piqueras J. A., Roca M., Rodríguez-Marín J., Rodríguez-Jimenez T., Soto-Sanz V., Alonso J. (2017). Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(3), 195–211. 10.1111/acps.12679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cava M. J., Tomás I., Buelga S., Carrascosa L. (2020). Loneliness, depressive mood and cyberbullying victimization in adolescent victims of cyber dating violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4269. 10.3390/ijerph17124269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E. C., Tsai W., Sanna L. J. (2010). Examining the relations between rumination and adjustment: Do ethnic differences exist between Asian and European Americans? Asian American Journal of Psychology, 1(1), 46–56. 10.1037/a0018821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. University Press [Google Scholar]

- Connolly J., Nocentini A., Menesini E., Pepler D., Craig W., Williams T. S. (2010). Adolescent dating aggression in Canada and Italy: A cross-national comparison. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(2), 98–105. 10.1177/0165025409360291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devries K., Watts C., Yoshihama M., Kiss L., Schraiber L. B., Deyessa N., Heise L., Durand J., Mbwambo J., Jansen H., Berhane Y., Ellsberg M., Garcia-Moreno C. & WHO Multi-Country Study Team. (2011). Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: Evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Social Science & Medicine, 73(1), 79–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do K. N., Weiss B., Pollack A. (2013). Cultural beliefs, intimate partner violence, and mental health functioning among Vietnamese women. International Perspectives in Psychology, 2(3), 149–163. 10.1037/ipp0000004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobash R. E., Dobash R. (1979). Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein B. A., Bhatia V., Davila J. (2014). Rumination mediates the association between cyber-victimization and depressive symptoms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(9), 1732–1746. 10.1177/0886260513511534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford B. Q., Mauss I. B. (2015). Culture and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 1–5. https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~eerlab/pdf/papers/Ford_Mauss_2015_Culture_ER.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee V. A., Linder F., MacDougall J. E., Bangdiwala S. (2001). Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Preventive Medicine, 32(2), 128–141. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galego Carrillo V., Santibáñez Gruber R. M., Iraurgi Castillo I. (2016). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies in women abuse. Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 28, 115–122. 10.7179/PSRI_2016.29.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galende N., Ozamiz-Etxebarria N., Jaureguizar J., Redondo I. (2020). Cyber dating violence prevention programs in universal populations: A systematic review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 1089–1099. 10.2147/PRBM.S275414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego G. G., Vasco J. F., y Melo J. A. (2019). Noviazgos Violentos en estudiantes de colegios públicos del municipio de Manizales: hallazgos y recomendaciones de Política. 10.13140/RG.2.2.15264.20484 [DOI]

- Gámez-Guadix M., Borrajo E., Zumalde E. C. (2018). Abuso, control y violencia en la pareja a través de internet y los smartphones: características, evaluación y prevención. Papeles del psicólogo, 39(3), 218–227. 10.23923/pap.psicol2018.2874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García F., Cova F., Rincón P., Vázquez C. (2015). Trauma or growth after a natural disaster? The mediating role of rumination processes. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 26557. 10.3402/ejpt.v6.26557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzón Segura A. M., Carcedo González R. J. (2020). Effectiveness of a prevention program for gender-based intimate partner violence at a Colombian primary school. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3012. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giner-Sorolla R. (2020). Powering your interaction [blog post]. A methodology blog for social psychology. https://approachingblog.wordpress.com/author/rogerginersorolla/

- Gracia-Leiva M., Puente-Martínez A., Ubillos-Landa S., González-Castro J. L., Páez-Rovira D. (2020). Off-and online heterosexual dating violence, perceived attachment to parents and peers and suicide risk in young women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3174. 10.3390/ijerph17093174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Leiva M., Puente-Martínez A., Ubillos-Landa S., Páez-Rovira D. (2019). Dating violence (DV): A systematic meta-analysis review. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 35(2), 300–313. 10.6018/analesps.35.2.333101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. 10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26. 10.9707/2307-0919.1014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. (2022, January 10) The 6-D model of national culture. Hofstede public access resource. http://www.geerthofstede.nl/

- Husin W. N. I. W., Khairunnizam N. A. (2020). The meeting link between emotional intelligence, rumination and suicidal ideation. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 5(12), 1092–1095[VcgTIC1]. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings W. G., Okeem C., Piquero A. R., Sellers C. S., Theobald D., Farrington D. P. (2017). Dating and intimate partner violence among young persons ages 15–30: Evidence from a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 107–125. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karakurt G., Cumbie T. (2012). The relationship between egalitarianism, dominance, and violence in intimate relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 27(2), 115–122. 10.1007/s10896-011-9408-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Knyazev G. G., Kuznetsova V. B., Savostyanov A. N., Dorosheva E. A. (2017). Does collectivism act as a protective factor for depression in Russia? Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 26–31. 10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft A. (2020). Perspectivas de la sociedad civil sobre la violencia sexual en los conflictos: patriarcado y estrategia de guerra en Colombia, Asuntos internacionales, 96(2), 457–478. 10.1093/ia/iiz257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde M. (2016). Los cautiverios de las mujeres: madres esposas, monjas, putas, presas y locas. Siglo XXI Editores México. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen R. J., Prizmic Z. (2004). Affect regulation. In Baumeister R. F., Vohs K. D. (Ed.). Handbook of self-regulation. Research, theory, and applications (pp. 40–61). The Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law K. C., Tucker R. P. (2018). Repetitive negative thinking and suicide: A burgeoning literature with need for further exploration. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 68–72. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Lee J. H. (2012). Attentional bias to violent images in survivors of dating violence. Cognition & Emotion, 26(6), 1124–1133. 10.1080/02699931.2011.638906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Liu Z., Yuan G. (2020). The longitudinal influence of cyberbullying victimization on depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms: The mediation role of rumination. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 34(4), 206–210. 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., Williams J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann H. M., Rutstein D. W., Hancock G. R. (2009). The potential for differential findings among invariance testing strategies for multisample measured variable path models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(4), 603–612. 10.1177/0013164408324470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marganski A., Melander L. (2018). Intimate partner violence victimization in the cyber and real world: Examining the extent of cyber aggression experiences and its association with in-person dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(7), 1071–1095. 10.1177/0886260515614283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Dorado A., Privado J., Useche S. A., Velasco L., García-Dauder D., Alfaro E. (2020). Perception of dating violence in teenage couples: A cross validation study in Spain and Colombia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6769. 10.3390/ijerph17186769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Lanas R., Osorio A., Anaya-Hamue E., Cano-Prous A., de Irala J. (2019). Relationship power imbalance and known predictors of intimate partner violence in couples planning to get married: A baseline analysis of the AMAR cohort study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), 10338–10360. 10.1177/0886260519884681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Equality. (2019). Macro Survey on Violence Against Women Retrieved from https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/macroencuesta2015/pdf/RE__Macroencuesta2019__EN.pdf

- Miranda-Mendizábal A., Castellví P., Parés-Badell O., Alayo I., Almenara J., Alonso I., Blasco M. J., Cebrià A., Gabilondo A., Gili M., Lagares C., Piqueras J. A., Rodríguez-Jiménez T., Rodríguez-Marín J., Roca M., Soto-Sanz V., Vilagut G., Alonso J. (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Public Health, 64(2), 265–283. 10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda Yanes M., Valdes Salas V. (2019). Narco-culture as a distortion of gender stereotypes: An aggravating factor in the situation of violence and conflict in society. Revista Adgnosis, 8(8), 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moolman B., Essop R., Tolla T. (2020). Navigating agency: Adolescents’ challenging dating violence towards gender equitable relationships in a South African township. South African Journal of Psychology, 50(4), 540–552. 10.1177/0081246320934363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mozley M. M., Modrowski C. A., Kerig P. K. (2021). Intimate partner violence in adolescence: Associations with perpetration trauma, rumination, and posttraumatic stress. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), 7940–7961. 10.1177/0886260519848782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Forensic Medicine and Forensic Sciences (INMLCF) (2015). Masatugó 2009-2014. Mujer que recibe lo malo, para entregar lo bueno. Bogotá. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (2019). Forensis, 2018. Imprenta Nacional. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S., Stice E., Wade E., Bohon C. (2007). Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(1), 198–207. 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogińska-Bulik N. (2016) Ruminations and effects of trauma in women experiencing domestic violence. Annals of Psychology, 19(4), 643–658. 10.18290/rpsych.2016.19.4-1en [DOI] [Google Scholar]