Summary

Background:

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection is the most aggressive form of chronic viral hepatitis. Response rates to therapy with 1- to 2-year courses of pegylated interferon alpha (peginterferon) treatment are suboptimal.

Aims:

To evaluate the long-term outcomes of patients with chronic hepatitis D after an extended course of peginterferon.

Methods:

Patients were followed after completion of trial NCT00023322 and classified based on virological response defined as loss of detectable serum HDV RNA at last follow-up. During extended follow-up, survival and liver-related events were recorded.

Results:

All 12 patients who received more than 6 months of peginterferon in the original study were included in this analysis. The cohort was mostly white (83%) and male (92%) and ranged in age from 18 to 58 years (mean = 42.6). Most patients had advanced but compensated liver disease at baseline, a median HBV DNA level of 536 IU per mL and median HDV RNA level of 6.86 log10 genome equivalents per mL. The treatment duration averaged 6.1 years (range 0.8–14.3) with a total follow-up of 8.8 years (range 1.7–17.6). At last follow-up, seven (58%) patients had durable undetectable HDV RNA in serum, and four (33%) cleared HBsAg. Overall, one of seven (14%) responders died or had a liver-related event vs four of five (80%) non-responders.

Conclusions:

With further follow-up, an extended course of peginterferon therapy was found to result in sustained clearance of HDV RNA and favourable clinical outcomes in more than half of patients and loss of HBsAg in a third.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection represents the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis and has an estimated worldwide prevalence of 12–20 million persons.1,2 HDV is a small, incomplete RNA virus which requires hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection for sustained replication and transmissibility.1 Patients with chronic HDV-HBV co-infection have a more aggressive hepatitis, progress to cirrhosis faster, and are at higher risk for HCC than patients with HBV alone. Unfortunately, therapies for chronic hepatitis D are suboptimal and the agents that are effective in chronic hepatitis B have little effect on disease progression in HDV-HBV co-infection. The only widely available therapy for chronic HDV infection is interferon alpha and its pegylated form, pegylated interferon alpha (peginterferon), but interferon is poorly tolerated, and response rates are low even with extended courses of 1–2 years. Non-response to treatment is common and patients with an on-treatment response usually relapse when therapy is stopped. An open label trial evaluating response rates to extended (3–5 years) therapy of peginterferon was conducted at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NCT00023322). In that study, 39% of patients achieved an endpoint of histological improvement or viral response at 3 years.3 In this report, we present the long-term follow-up of these patients 10 years after completion of the original protocol.

2|. MATERIALS AND METHODS

All patients with chronic HDV infection having completed more than 6 months of peginterferon therapy under the original protocol from 2001 to 2009 were considered in this analysis. Initial inclusion criteria were: documented chronic HDV infection based on chronic elevations in serum aminotransferase levels, the presence of HDV antigen in liver (by immunoperoxidase staining) and biopsy findings of necroinflammation with a histology activity index (HAI) score of at least 5 and Ishak fibrosis stage of at least 1. Exclusion criteria included decompensated liver disease, co-existing liver disease (other than hepatitis B) and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients were treated with pegylated interferon alpha-2a (Pegasys, Roche) 180 μg subcutaneously once weekly with a possible dose escalation to a maximum of 360 μg weekly after the initial 24 weeks. Per-protocol, treatment could be extended, initially for a duration of up to 5 years. Entry liver biopsy and hepatic venous pressure gradient were obtained and repeated during the course of the protocol. Results of this study were previously published.3 After completion of the study, patients were followed under a liver disease natural history protocol at the Clinical Center, NIH (NCT00001971). Peginterferon treatment was extended on a case-by-case basis. The criteria for discontinuation were (a) intolerable side effects, or (b) lack of biochemical or virological response after the initial 6 months of therapy, or (c) sustained loss of HBsAg. After stopping therapy regular prospective follow-up was offered with clinical evaluation yearly.

Virological response was defined as lack of detectable HDV RNA using a polymerase chain reaction-based assay (PCR) at the time of evaluation. Loss of HBsAg was defined as undetectable serum HBsAg on two consecutive tests at least 6 months apart. Liver-related outcomes were defined as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma or liver transplantation. Death from liver related as well as all causes was recorded.

During the original study, measurement of HDV RNA was performed by quantitative PCR on stored samples with a lower limit of detection of 100 genome equivalents (GE) per mL (National Genetics Institute). Afterwards the serum HDV RNA levels were measured on stored serum samples by a PCR assay with a lower limit of detection of 120 IU/mL (ARUP Laboratories). HBV DNA was detected using Roche COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan® HBV Test, version 2.0 with a lower limit of detection of 20 IU/mL. The IL28B-associated rs12989760 SNP was genotyped in genomic DNA by Taqman Custom SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems) as previously described.3

Liver biopsies were obtained before initiation of peginterferon therapy and after 3 years but were not repeated during or after long-term therapy. Biopsies were scored for disease activity using the histology activity index (HAI: 0–18) and for fibrosis using the Ishak fibrosis score (0–6). Fib4 was calculated as (Age × AST (U/L))/(Platelet Count (109/L) × √ALT (U/L)),4 and the AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) as ((AST (U/L)/(AST Upper limit of normal))/Platelet Count (109/L).5

Continuous variables are reported as means and ranges and were evaluated using non-parametric tests. All statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 8.4.1. (GraphPad Software).

The protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the NIH Clinical Center. All patients provided written informed consent. These studies conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

3 |. RESULTS

Twelve patients, from the original protocol of thirteen patients, completed at least 6 months of peginterferon therapy and were included in this analysis. Baseline characteristics at enrolment are summarised in Table 1. Patients were mostly Caucasian and male, with a mean age of 42.6 years at treatment initiation. All patients had fairly advanced but compensated liver disease at baseline with a mean Ishak fibrosis score of 3.8 (range 3–6) and HAI scores of 10.5 (range 7–14). Measurement of hepatic vein pressure gradient was performed in all 12 patients and averaged 9.7 mm Hg (range 4–25). Routine liver tests showed mean total bilirubin of 0.9 mg/dL, ALT 150 U/L, AST 122 U/L and alkaline phosphatase 102 U/L. Serum albumin averaged 3.6 g/dL and platelet count 149 K/μL. The median HDV RNA was 7 300 000 GE/mL (6.86 log10 GE/mL). Five patients (42%) had undetectable or below the lower limit of quantification HBV DNA, and the median HBV viral load in those with quantifiable levels was 536 (range 103–85 000) IU/mL. HBeAg was detected in three patients and anti-HBe without HBeAg in nine patients. All patients were positive for HBsAg and levels averaged 3.7 log10 IU/mL (range 2.6–4.3).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the overall patient population

| N = 12 | |

|---|---|

| Age—years | 42.6 (18–58) |

| Male gender—% (n) | 92% (11) |

| Ethnicity—% (n) | 83% (10) Caucasian 17% (2) African-American |

| ALT—U/L | 150 (41–506) |

| AST—U/L | 122 (34–348) |

| ALP—U/L | 102 (48–227) |

| Total bilirubin—mg/dL | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) |

| Direct bilirubin—mg/dL | 0.2 (0.1–0;8) |

| Albumin—g/dL | 3.6 (2.9–4.1) |

| Platelet count—K/μL | 149 (78–237) |

| HDV RNA—log10 genome equivalents/mL | 6.73 (4.50–8.49) |

| HBsAg—log 10 IU/mL | 3.67 (2.64–4.33) |

| HBV DNA undetectable—% (n) | 31% (5) |

| HBV DNA—IU/mLa | 536 (103–85 000) |

| Fib4 | 3.6 (0.5–11.6) |

| APRI | 2.3 (0.4–7.4) |

| Ishak fibrosis score | 3.8 (3–6) |

| HAI inflammation score | 10.5 (7–14) |

| HVPG—mm Hg | 9.7 (4–25) |

| IL28B-associated Rs12979860 genotype (n = 10) | 50% CC 50% CT |

Note: Mean (range).

Abbreviations: APRI, AST to platelet ratio index; HAI, histology activity index; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient.

Median (range)—restricted to seven patients with detectable HBV DNA.

Overall, the mean duration of therapy was 6.1 years (range 0.8–14.3) and follow-up after stopping therapy 5.5 years (0–15.3). Thus, the average total duration of treatment and follow-up was 8.8 years (range 1.7–17.6). Following the end of the clinical trial, five patients were treated for longer than the protocol defined duration of 5 years, under compassionate use for up to nine additional years.

3.1 |. Treatment response

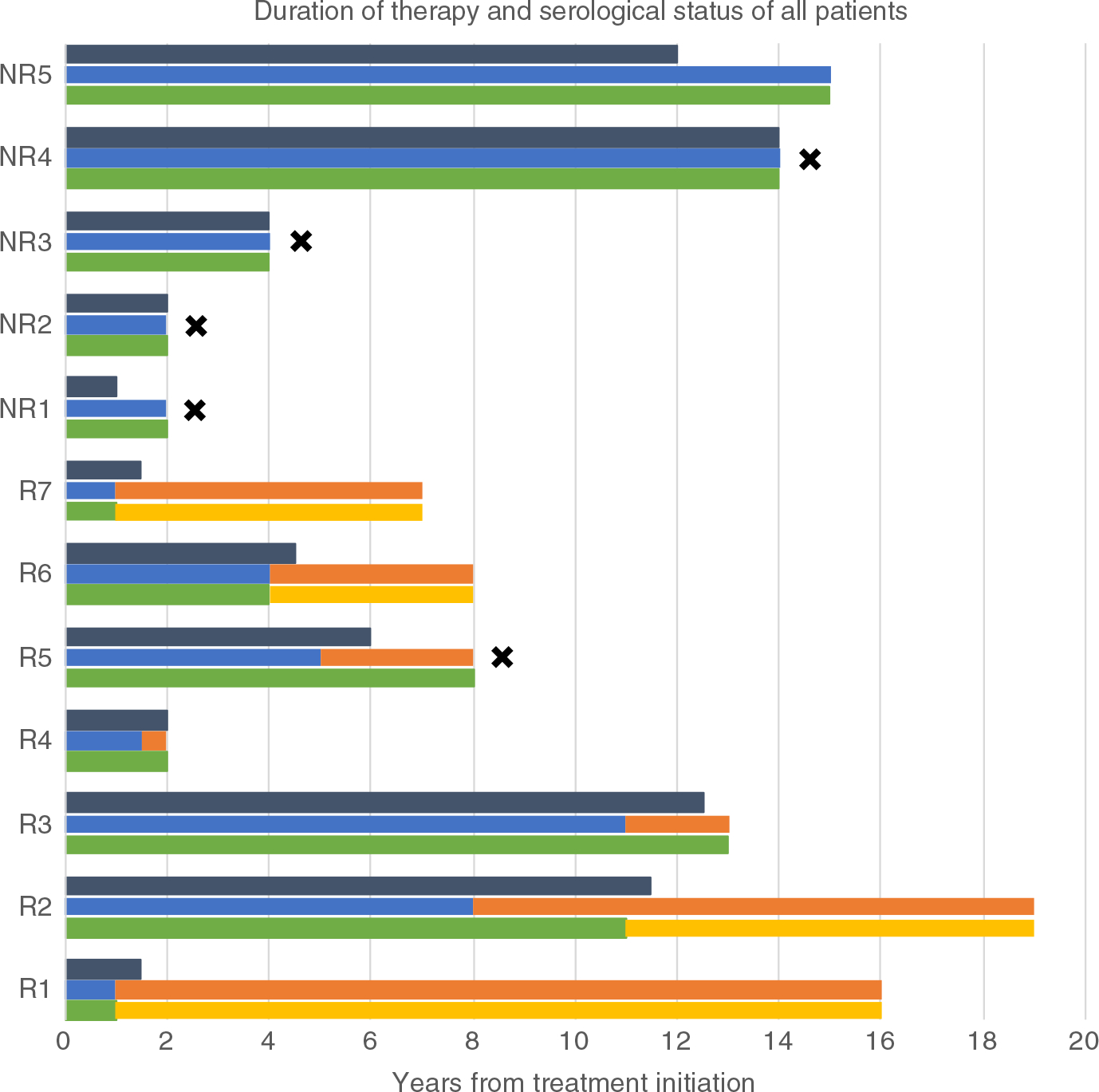

The timing of therapy, HDV RNA results and HBsAg status of the seven responders (R) and the five non-responders (NR) are shown graphically in Figure 1. At last available follow-up, seven (58%) patients had no detectable HDV RNA in serum. While this endpoint was achieved in five patients during the original protocol, two patients benefited from extension of treatment beyond 5 years and did not achieve a full virological response until after 8 and 11 years of therapy. No patients required a resumption of therapy once it was discontinued. Patients with virological response were followed for 54 months on average after treatment discontinuation (range 0–198).

FIGURE 1.

Duration of therapy and serological status of all patients. Grey bar: peginterferon treatment duration; Blue bar: HDV RNA positive; Orange bar: HDV RNA negative; Green bar: HBsAg positive; Yellow bar: HBsAg negative; Black star: death; NR: non-responder; R: responder

Four patients (33%) cleared serum HBsAg during therapy at year 1 (R1 and R7), year 4 (R6) and year 11 (R2). The loss of HBsAg was sustained after stopping therapy in all four patients. All four patients who lost HBsAg subsequently developed anti-HBs, which however was not sustained in one case (R2). The three responders who remained HBsAg positive included one who was lost to follow-up while still on therapy (R4) and two who discontinued peginterferon but remained HDV RNA negative during follow-up of 6 months (R3) and 3.5 years (R5). One of the three subjects who was initially HBeAg positive had HBeAg loss after 1 year of peginterferon, but without development of anti-HBe over the course of the follow-up.

Two patients, both HBeAg positive non-responders, were started on anti-HBV therapy due to active HBV replication before initiation of peginterferon and were maintained on this therapy throughout follow-up. Two responders were started on anti-HBV therapy during peginterferon treatment due to an increase in HBV viral loads at the time of peginterferon discontinuation in one case and during peginterferon therapy in another. Both of these patients were maintained on treatment due to the occurrence of clinical events during follow-up. HBV viral replication was suppressed in all four patients on HBV therapy, as well as in all other patients who did not require therapy but were closely monitored. Only one non-responder had a transient HBV DNA increase at peginterferon discontinuation which did not require therapy and five patients remained with undetectable HBV DNA throughout follow-up.

3.2 |. Comparison of responders to non-responders

Baseline characteristics were similar between responders and non-responders, although the sample size may well have underestimated differences in markers of fibrosis and advanced disease between the two groups (Table 2). HBV and HDV markers and mutations in IL28B rs12989760 genotype (associated with response to interferon in chronic hepatitis C) were also not different in the two groups. Available laboratory markers from last follow-up are presented in Table 3. Compared to baseline, ALT and AST levels decreased in both groups, but the changes were only significant among responders. Serum total bilirubin as well as platelet counts did not change significantly in either group. The non-invasive markers of hepatic fibrosis, APRI and Fib4, changed slightly (one decreased and one increased), but the differences were not significant.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of responders compared to non-responders

| Responders (n = 7) | Non-responders (n = 5) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT—U/L | 119 (41–296) | 193 (42–506) | 0.64 |

| AST—U/L | 101 (34–240) | 152 (38–191) | 0.46 |

| ALP—U/L | 82 (55–127) | 129 (48–227) | 0.53 |

| Total bilirubin—mg/dL | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.8) | 0.21 |

| Platelet count—K/μL | 153 (78–228) | 144 (81–237) | 0.99 |

| HDV RNA—log10 GE/mL | 6.48 (4.78–7.34) | 7.02 (4.50–8.49) | 0.43 |

| HBsAg—log10 IU/mL | 3.69 (2.86–4.32) | 3.65 (2.64–4.33) | 0.99 |

| HBV DNA—IU/mLa | 536 (126–3232) | 582 (103–85 000) | 0.99 |

| Fib4 | 3.1 (0.8–5.7) | 4.3 (0.5–11.6) | 0.99 |

| APRI | 1.8 (0.4–4.0) | 3.0 (0.9–7.4) | 0.76 |

| Ishak fibrosis score | 3.6 (3–6) | 4.2 (3–6) | 0.20 |

| HAI score | 10.7 (7–14) | 10.2 (7–14) | 0.72 |

| HVPG—mm Hg | 8.0 (5–13) | 12.2 (4–25) | 0.56 |

| IL28B-associated Rs12979860 genotype (n = 10) %(n) | 60% CC (3) | 40% CC (2) | 0.99b |

| 40% CT (2) | 60% CT (3) |

Notes: All results reported as means (range) unless specified otherwise.

Groups compared with Mann-Whitney test.

Median (range).

Fisher’s exact test.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of laboratory values at last available follow-up

| Responders | Non-responders | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALT—U/L | 35 (21–50) | 78 (31–155) | 0.4520 |

| AST—U/L | 37 (10–79) | 89 (42–191) | 0.0278 |

| Total bilirubin—mg/dL | 1.1 (0.4–1.9) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.3636 |

| ALP—U/L | 77 (58–98) | 123 (83–187) | 0.0303 |

| Platelet count—K/μL | 131 (60–208) | 121 (53–215) | 0.8763 |

| APRI | 0.91 (0.14–1.87) | 1.92 (1.11–2.81) | 0.0481 |

| Fib4 | 3.23 (0.49–7.96) | 5.08 (2.29–8.77) | 0.1490 |

Notes: All results reported as means (range).

Groups compared with Mann-Whitney test.

3.3 |. Management of peginterferon therapy

Five patients were maintained on a constant dose of peginterferon of 180 μg/week, four tolerated an increased dose (up to 270 μg/ week), while the remaining three patients required at least one dose reduction. Decrease in peginterferon dose was required within the first year on treatment in one responder due to anaemia, in one non-responder due to cytopenias and in one non-responder due to combined thrombopenia and anaemia. Temporary discontinuation was also required in the latter patient due to sepsis and in one responder due to neutropenic fever; however, re-increase was tolerated afterwards.

All patients were monitored for psychiatric and psychological effects prior and during therapy. Eight patients were evaluated by psychiatry and received pharmaceutical intervention; Five patients received antidepressants at the time of peginterferon initiation, with prophylactic pharmacological therapy in four of them. Out of this group, treatment was discontinued within a year in two cases. A single patient was treated with anti-psychotics and remained stable during the clinical trial but his psychiatric condition led to compliance issues on long-term follow-up. Two patients had antidepressant medications initiated while on therapy at 3 and 4 years into treatment, with eventual discontinuation of antidepressant while remaining on peginterferon in one case.

3.4 |. Clinical events

On long-term follow-up, only one of seven (14%) responders died compared to four of five (80%) non-responders (Figure 1). The death of the responder (R5) occurred 2 years after stopping peginterferon and was attributed to sepsis and pulmonary hypertension which was considered unrelated to the liver disease or to the therapy. In the non-responder group, one patient developed hepatocellular carcinoma (NR1) and one cholangiocarcinoma (NR4), both of whom ultimately died due to complications of the cancer. A third patient died of herpes simplex colitis in the context of underlying Crohn’s disease (NR2).6 The fourth patient was lost to follow-up and died from an unknown cause (NR3).

A second responder developed transient hepatic decompensation when treated with adoptive T-cell therapy for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy but recovered hepatic function thereafter.

4 |. DISCUSSION

The search for a cure for delta hepatitis remains elusive, with unsatisfactory response to current available and experimental therapies. In this prospective follow-up of a series of patients treated with long-term peginterferon, treatment response occurred and was sustained with the use of HBsAg status to guide continuation or discontinuation of treatment. This study builds on previous findings of treatment response to long-term therapy and demonstrates benefits from tailored extension of treatment.

Response rates, whether for year-long peginterferon treatment (21%-24% in the largest studies)7,8 or 2-year-long treatment (40%) are underwhelming.9,10 One of the major issues remains sustained response after treatment, which is only achieved in one quarter of treated patients.7,11 Patients who achieve negative HDV RNA at the end of therapy often relapse and require additional treatment. Long-term follow-up of previous peginterferon studies has demonstrated that late relapse is unfortunately common.11 Encouragingly, a proportion of patients respond to peginterferon; however, identifying which patients will respond to treatment remains a challenge. In this study, patients who tolerated peginterferon were maintained on treatment as long as a response was sustained (based on ALT levels) and tolerated. The decision to discontinue peginterferon treatment was made on an individualised basis. Once HDV virological response occurred, treatment was extended for a consolidation period of 6 months to ensure the outcome was sustained and in order to maximise potential of HBsAg seroconversion. We demonstrate that in a selected group of patients and with close dose monitoring and adjustment, therapy can be tolerated and a durable virological response can be maintained for more than 4 years on average without relapse.

In previous reports, treatment response was associated with fewer liver-related events11 and decreased mortality as well as stabilisation of fibrosis.7,12 Our findings add to the body of evidence that virological response in HDV provides durable benefits and significantly less major clinical events.13 No liver-related deaths occurred in responders, even though their baseline characteristics and severity of liver disease were similar to non-responders. Thus, a durable response to treatment in HDV appears to change the natural history of the disease. Furthermore, non-response to peginterferon was associated with increased overall non-liver-related mortality. This finding is in line with previous reports on overall mortality in chronic hepatitis C virus infection treated with peginterferon.14 Achieving treatment response with peginterferon in viral hepatitis can potentially influence chronic inflammatory states and therefore reduce all-cause mortality.15

Achieving HBsAg loss, or functional cure, in HDV on treatment has been associated with a favourable prognosis. This outcome has been shown to be the best indicator of remaining HDV RNA negative.3,11 In addition, seroconversion is the ultimate goal (albeit infrequently reached) in HBV and remains the ultimate goal in HDV therapy. Patients who develop HBsAg loss remain protected from relapse in the future. Extending therapy with the use of HBsAg titres in order to achieve functional cure has previously been suggested.16,17 In this same group of subjects, the slope of decline in HBsAg titres paralleled the slope of the second phase of HDV RNA decline and responders demonstrated a faster HBsAg titre decline.17 In the future, the use of novel markers, such as HBV RNA, can potentially be useful in the assessment of viral kinetics and response to therapy.

The major shortcoming of this study was the limited number of subjects in this case series, but the small scale of study was partially compensated by the rigorous and long-term follow-up. The duration of follow-up allowed for documentation of the persistence of the virological responses and the absence of hard, clinically important, adverse endpoints in patients with a durable virological response, with or without an accompanying loss of HBsAg. Liver biopsies were not obtained during non-protocolised long-term follow-up, however, serological markers of fibrosis remained stable. An improvement in non-invasive markers could have potentially been expected due to reduction of inflammatory activity with treatment, however, the performance of these markers in chronic hepatitis delta is suboptimal.18,19 While we were unable to determine predictive factors of virological response, a case-by-case approach and tailoring of therapy proved beneficial in over half of patients. Overall, even though patients presented with advanced compensated liver disease at baseline, a low number of liver-related events occurred during follow-up and these occurred largely in the non-responder group. The non-liver-related deaths occurring due to sepsis and herpes simplex colitis were precipitated by other underlying conditions and cannot be attributed to peginterferon therapy itself. While the role of peginterferon in the onset of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in one patient remains uncertain, treatment-induced bone marrow suppression and underlying cirrhosis can be considered predisposing factors.20

Peginterferon remains the only form of therapy available outside of clinical trials, without formal approval for chronic HDV in the United States, and promising new treatment options are currently being studied.21–23 Nonetheless, our results support the ongoing attempts to identify novel direct-acting anti-viral agents that better suppress HDV RNA levels chronically by showing that durable virological response is associated with a lower rate of adverse clinical outcomes. Thus, peginterferon therapy for chronic hepatitis D has a similar status as did peginterferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C before the advent of direct-acting anti-viral agents for that disease.

Virological responses after an extended course of peginterferon were durable in a portion of patients with chronic hepatitis D with advanced but compensated liver disease. Judicious tailoring of treatment duration based on response and tolerance allowed for an individualised approach to treatment. Besides improvement in serum enzymes, overall liver-related events and mortality were improved with sustained treatment responses. Achievement of sustained absence of detectable HDV RNA, durable virological response, should remain the goal of therapy with the ultimate objective of a sustained loss of HBsAg and functional cure of the infection. While these results are encouraging, there remains a critical need for additional treatment options for chronic hepatitis D.

Funding information

NIDDK Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Declaration of personal interests: None.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hercun J, Koh C, Heller T. Hepatitis delta: prevalence, natural history, and treatment options. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49:239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stockdale AJ, Kreuels B, Henrion MYR, et al. The global prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heller T, Rotman Y, Koh C, et al. Long-term therapy of chronic delta hepatitis with peginterferon alfa. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith JO, Sterling RK, Mills AS, et al. Herpes simplex virus colitis in a patient with Crohn’s disease and hepatitis B and D cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;6:120–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wedemeyer H, Yurdaydìn C, Dalekos GN, et al. Peginterferon plus adefovir versus either drug alone for hepatitis delta. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niro GA, Ciancio A, Gaeta GB, et al. Pegylated interferon alpha-2b as monotherapy or in combination with ribavirin in chronic hepatitis delta. Hepatology. 2006;44:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wedemeyer H, Yurdaydin C, Hardtke S, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis D (HIDIT-II): a randomised, placebo controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yurdaydin C, Bozkaya H, Karaaslan H, et al. A pilot study of 2 years of interferon treatment in patients with chronic delta hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidrich B, Yurdaydın C, Kabaçam G, et al. Late HDV RNA relapse after peginterferon alpha-based therapy of chronic hepatitis delta. Hepatology. 2014;60:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farci P, Roskams T, Chessa L, et al. Long-term benefit of interferon alpha therapy of chronic hepatitis D: regression of advanced hepatic fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1740–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yurdaydin C, Keskin O, Kalkan Ç, et al. Interferon treatment duration in patients with chronic delta hepatitis and its effect on the natural course of the disease. J Infect Dis. 2018;217:1184–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Bisceglie AM, Stoddard AM, Dienstag JL, et al. Excess mortality in patients with advanced chronic hepatitis C treated with long-term peginterferon. Hepatology. 2011;53:1100–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Belperio P, Halloran J, Mole LA. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:509–516.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ouzan D, Pénaranda G, Joly H, Halfon P. Optimized HBsAg titer monitoring improves interferon therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis delta. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1258–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guedj J, Rotman Y, Cotler SJ, et al. Understanding early serum hepatitis D virus and hepatitis B surface antigen kinetics during pegylated interferon-alpha therapy via mathematical modeling. Hepatology. 2014;60:1902–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takyar V, Surana P, Kleiner DE, et al. Noninvasive markers for staging fibrosis in chronic delta hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:127–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da BL, Surana P, Kleiner DE, Heller T, Koh C. The Delta-4 fibrosis score (D4FS): a novel fibrosis score in chronic hepatitis D. Antiviral Res. 2020;174:104691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gheuens S, Pierone G, Peeters P, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in individuals with minimal or occult immunosuppression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koh C, Canini L, Dahari H, et al. Oral prenylation inhibition with lonafarnib in chronic hepatitis D infection: a proof-of-concept randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2A trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bogomolov P, Alexandrov A, Voronkova N, et al. Treatment of chronic hepatitis D with the entry inhibitor myrcludex B: first results of a phase Ib/IIa study. J Hepatol. 2016;65: 490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bazinet M, Pântea V, Cebotarescu V, et al. Safety and efficacy of REP 2139 and pegylated interferon alfa-2a for treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B virus and hepatitis D virus co-infection (REP 301 and REP 301-LTF): a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:877–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.