Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to describe the association between patient ethnicity/race and desire to continue using a pessary for the treatment of pelvic floor disorders.

Methods:

We performed a secondary analysis of a randomized trial among women presenting for pessary fitting. The primary outcome was the desire to continue using a pessary at 3 months. Bacterial vaginosis by Nugent score and vaginal symptoms (discharge, itching, pain, sores) were also evaluated. Logistic or multiple linear regression was performed with correction for body mass index, education level, parity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and randomization to TrimoSan gel.

Results:

One hundred fourteen women (41 Hispanic and 73 non-Hispanic) were eligible for this analysis. Women self-identified as white (65/114; 57%), Hispanic (41/114, 36%), Asian (3/114; 2.6%), Native American (4/114; 3.5%), and “other” (1/114, 0.9%) race, with no self-identified African American women (0/114) meeting the inclusion criteria. No significant difference in desire to continue pessary use was found between Hispanic and non-Hispanic women (58.5% vs 63%; P = 0.69; corrected odds ratio [cOR], 1.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.43–2.90) or across races (P = 0.89). Hispanic women had significantly higher risk of bacterial vaginosis (34% vs 16%; P = 0.04; cOR, 2.91; 95% CI, 1.01–8.39), higher Nugent scores (5.4 ± 2.3 vs 4.3 ± 2.3; P = 0.02; corrected coefficient, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.10–2.10), and more vaginal pain (17.1% vs 2.8%; P = 0.01; cOR, 9.14; 95% CI, 1.37–61.17) at 3 months.

Conclusions:

Despite increased vaginal pain and vaginal microbiome disturbances in Hispanic women using a pessary, no significant differences in the desire to continue using the pessary existed.

Keywords: pessary, ethnicity, race, prolapse, Hispanic

Pelvic floor disorders, including urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), afflict almost 25% of women in the United States.1,2 Pessaries provide a treatment option for women who either cannot undergo surgery or prefer a nonsurgical option for POP.3–5 Pessaries are low cost, accessible treatments that provide many users immediate relief of their symptoms with high short-term satisfaction,6,7 but more than half of women discontinue pessary use in longer term8,9 and bothersome adverse effects are common.10 Therefore, pessary satisfaction, continuation, and success are difficult to predict for individual patients.10,11

Race, ethnicity, and cultural attitudes are thought to affect how patients understand and perceive their disease experience, including differences associated with race and ethnicity for pelvic floor disorders.12 A cohort study on symptom bother in stage II POP reported that Native American and Hispanic women had higher distress for the same stage of prolapse when compared with non-Hispanic white women.13

Despite these data on the relationship of race and bother from pelvic floor dysfunction, a gap exists in our understanding of the relationship between race or ethnicity and pessary satisfaction.8,14 Most of the available literature on pessary success investigates clinical characteristics (such as vaginal length or a prior hysterectomy) as opposed to disparities that may exist between races. Given the overwhelming data demonstrating differences in health care and outcomes between minority and white women in a variety of fields,15–17 it is vital to explore if such disparities exist in pelvic floor dysfunction treatment.

The aims of this study were to investigate associations between ethnicity/race and patient desire to continue pessary treatment in a population of women recently fitted with a pessary and to investigate variation in other outcomes such as microbiological factors and vaginal symptoms between ethnic and racial populations. Because of prior data suggesting that Hispanic women have a higher symptom bother with POP,13 we hypothesized that more Hispanic women would opt to continue using their pessary 3 months after pessary initiation as compared with non-Hispanic women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective secondary analysis of a randomized, controlled trial that investigated the role of an acidic vaginal gel on the rate of pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis (BV). Study design was previously described in detail.18 Participating women completed baseline questionnaires on self-identified race/ethnicity, medical history, vaginal medication use, and baseline vaginal symptoms (vaginal itching, vaginal discharge, vaginal sores, and vaginal pain). If a woman was found to have BVon the color-changing enzyme test before pessary fitting, she was treated with antibiotic therapy. The subjects returned for follow-up pelvic examinations and outcome questionnaires at 2 weeks and at 3 months.

Subjects rated their desire to continue pessary use on a 4-point Likert scale in response to the question: “How much do you want to keep wearing your pessary in the future?” Possible responses included the following: “1, not at all—I have no interested in continuing my pessary and want to stop wearing it now or have stopped wearing it”; “2, somewhat—using the pessary is not perfect, but I can be convinced to keep using it”; “3, moderately—I want to keep using the pessary”; or “4, quite a bit—I need to keep using the pessary and it is very important to me”. The primary outcome in this secondary analysis was the desire to continue pessary use at 3 months after fitting, defined as a patient rating of 3 or 4 on this Likert scale. Women were included in this analysis if they answered the question on self-identified ethnicity/race upon recruitment into the randomized trial, followed up at 3 months, and responded to this Likert scale question on desire to continue a pessary. Only patients recruited from 1 of 2 sites participating in the original trial (University of New Mexico) were queried regarding their desire to continue pessary use and therefore eligible for this secondary analysis.

The parent study was powered for the effects of the hydroxyquinoline (TrimoSan) gel on BV by Nugent criteria at 3 months. In this secondary study, we performed a post hoc power analysis on the number of eligible women. We had a cohort of 114 women, including 73 non-Hispanic and 41 Hispanic subjects, which resulted in 80% power to detect an odds ratio (OR) of 3.2 or greater between Hispanic ethnicity and non-Hispanic ethnicity for the desire to continue using a pessary after 3 months of use.

Our secondary outcomes included the prevalence of BV as measured by a Nugent score at 3 months (total Nugent score ≥7) and the presence of vaginal symptoms reported at 3 months (vaginal itching, vaginal discharge, vaginal sores, and vaginal pain). Outcomes were compared by both ethnicity (non-Hispanic vs Hispanic) and by racial categories self-identified by patients (African American or “black,” non-Hispanic white or “white,” Asian, Hispanic, and “other,” which included both Native American as well as true “other”). Hispanic was included as a racial category because many women in study region (New Mexico) consider both their ethnicity and their race to be Hispanic.

Descriptive statistics, such as percentages, means, and SDs, were calculated for each variable and compared between groups. Fisher exact test was used to compare the desire for continued pessary use between non-Hispanic and Hispanic subjects. To compare other categorical variables, χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests were used where appropriate. t Tests were used for continuous variable comparison between groups. When dealing with missing entries in the data set, all analyses were performed using an all available cases approach. Univariate regression testing was done to determine significant variables as related to study outcomes including pessary satisfaction, BV by Nugent criteria, and total Nugent score. Multiple linear regression and logistic regression tests were used to correct the relationship between ethnicity (Hispanic and non-Hispanic) and outcomes for significant variables in the univariate analysis, which included body mass index (BMI), parity, education, Charlson Comorbidity Index,19 and randomization to TrimoSan gel, and corrected ORs were generated where relevant. Statistical significance for all tests were set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

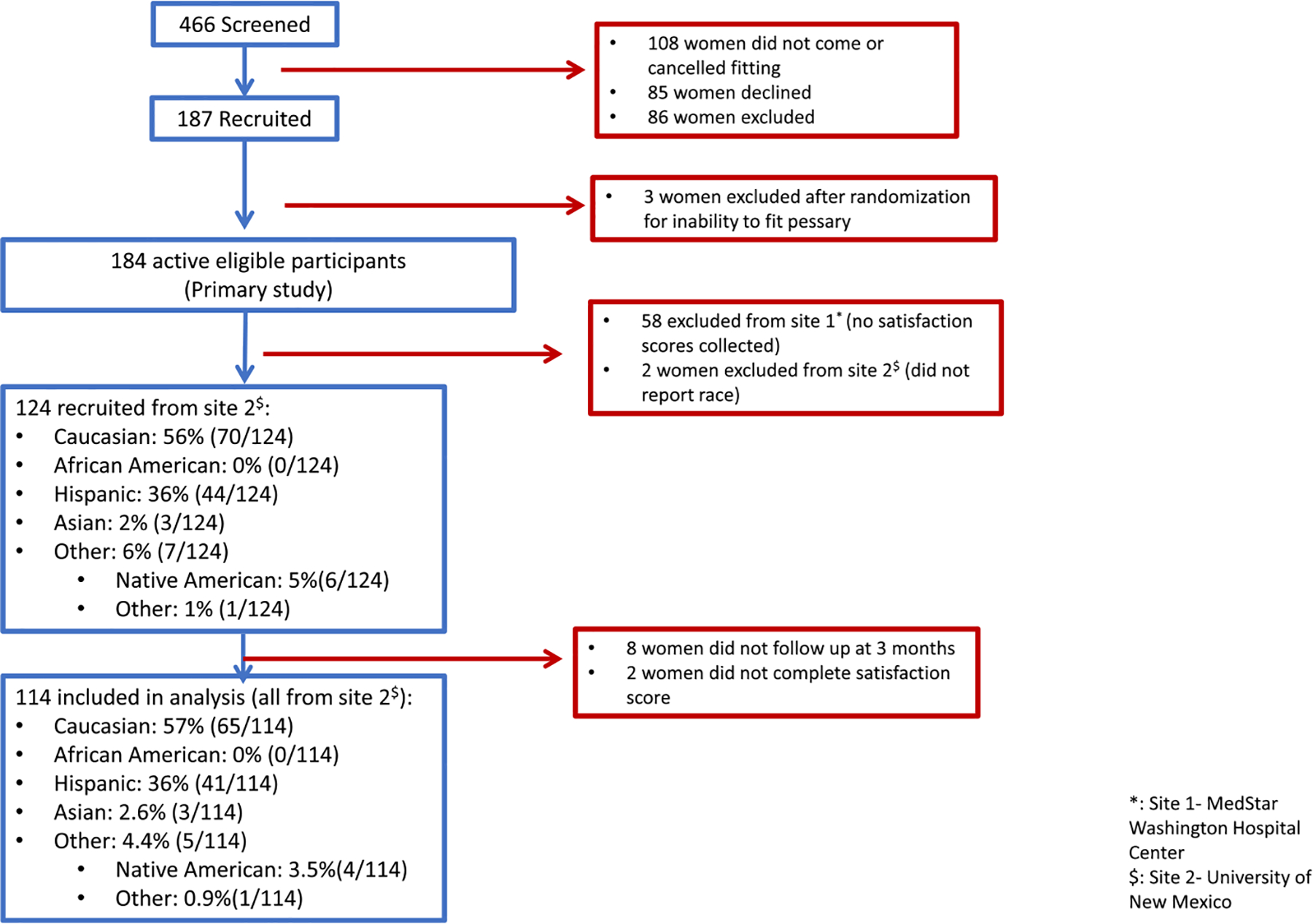

There were 184 women randomized in the parent study.18,20 Of this group, 124 women were recruited at the New Mexico site, self-identified with an ethnicity and/or race, and were eligible for secondary analysis. Of these, 114 women (41 Hispanic, 73 non-Hispanic) returned for follow-up at 3 months and completed the continuation of pessary questionnaire (Fig. 1). There was no difference in follow-up at 3 months between Hispanic and non-Hispanic women (41/44 [93%] vs 75/80 [94%], P = 0.59). Women in this analysis had a mean age of 55.5 ± 14 years and a mean BMI of 28.4 ± 7.5 kg/m2. The women in this cohort most frequently identified their race as non-Hispanic white (65/114 [57%]) or Hispanic (41/114 [36%]), with less women reporting Asian (3/114 [2.6%]), Native American (4/114 [3.5%]), or “other” (1/114 [0.9%]) race. No women in this study cohort self-identified as African American.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of subject enrollment and inclusion in analysis.

Patient characteristics were similar between self-reported races and ethnicities (Table 1). Hispanic women had higher BMI (30.6 ± 8.1 kg/m2 vs 27.2 ± 6.9 kg/m2, P = 0.03) and parity (median, 3 vs 2; P = 0.01) than did non-Hispanic women. Fewer Hispanic women had completed college or graduate school (19/41 [46%] vs 54/73 [74%], P < 0.01), and Hispanic women had worsened health as indicated by scores on the Charlson Comorbidity Index (median, 0 [0–0] vs 0 [0–1]; P = 0.04). Age, number of vaginal deliveries, prior pessary use, smoking status, insurance type, job activity level, history or prior pelvic surgery, indications for pessary use, the use of hormone therapy, frequency of pessary removal, baseline vaginal symptoms, and mean Nugent scores as well as rates of BV were all similar between the 2 ethnic groups. No other significant differences were noted in patient characteristics between individual racial groups.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics Compared Between Different Self-identified Ethnicities (Hispanic and Non-Hispanic) and Races Within This Study Cohort

| All Patients (n = 114), Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) or n (%) | Hispanic (n = 41), Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) or n (%) | Non–Hispanic (n – 73), Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) or n (%) | P Value by Ethnicity (Hispanic, Non–Hispanic) | White (n – 65), Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) or n (%) | Asian (n = 3), Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) or n (%) | Other (n – 5), Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) or n(%) | P Value for Face (White, Hispanic, Asian, Other*) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 55.5 ± 14.0 | 56.8 ± 13.9 | 53.2 ± 14.1 | 0.20 | 58 ± 13.8 | 39.7 ± 6.8 | 51.8 ± 10.9 | 0.06 |

| BML kg/m2 | 24.5 ± 7.5 | 30.6 ± 8.1 | 27.2 ± 6.9 | 0.03 | 27.7 ± 6.7 | 19.2 ± 13 | 26.1 ± 4.4 | 0.03 |

| Parity | 3 (2–3.2) | 3 (2–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.01 | 2 (1.8–3) | 1 (1–2) | 3.5 (2.5–4.5) | 0.03 |

| Vaginal deliveries | 2 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 2 (1.8–3) | 0.12 | 2 (2–3) | 1 (1–2) | 3 (3–4) | 0.13 |

| Education | <0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Less than high school diploma | 4 (3.7) | 4 (10.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| High school | 32 (29.4) | 16 (41) | 16 (22.9) | 15 (24.2) | 0 | 1 (20) | ||

| College | 41 (37.6) | 12 (30.8) | 29 (41.4) | 23 (37.1) | 2 (66.7) | 4 (80) | ||

| Graduate school | 32 (29.4) | 7 (17.9) | 25 (35.7) | 24 (38.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | ||

| Insurance type | 0.29 | 0.48 | ||||||

| Private | 46 (48.4) | 17 (50) | 29 (47.5) | 26 (46.4) | 2 (100) | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Public | 38 (40) | 11 (32.4) | 27 (44.3) | 26 (46.6) | 0 | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Uninsured | 11 (11.6) | 6 (17.6) | 5 (8.2) | 4 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (33.3) | ||

| Job activity level | 0.92 | 0.41 | ||||||

| Sedentary | 15 (14) | 7 (17.9) | 8 (11.8) | 7 (11.7) | 0 | 1 (20) | ||

| Light | 38 (35.5) | 13 (33.3) | 25 (36.8) | 23 (38.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (20) | ||

| Heavy | 7 (6.5) | 2 (5.1) | 5 (7.4) | 3 (5) | 0 | 2 (40) | ||

| Homemaker | 21 (19.6) | 8 (20.5) | 13 (19.1) | 11 (18.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–1) | 0.03 | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.03 |

| Smoking status | 0.70 | |||||||

| Never | 68 (60.2) | 26 (63.4) | 42 (58.3) | 35 (54.7) | 2 (66.7) | 5 (100) | ||

| Previous | 33 (29.2) | 11 (26.8) | 22 (30.6) | 21 (32.8) | 1 (33.3) | 0 | ||

| Current | 12 (10.6) | 4 (9.8) | 8 (11.1) | 8 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Prior pessary use | 5 (4.4) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (4.1) | 1.0 | 3 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Indication for pessary use | 0.77 | 0.73 | ||||||

| Prolapse | 36 (33.3) | 12 (30) | 24 (35.3) | 21 (32.3) | 0 | 3 (60) | ||

| Incontinence | 52 (48.1) | 21 (52.5) | 31 (45.6) | 26 (40) | 3 (100) | 2 (40) | ||

| Both prolapse and incontinence | 17 (15.7) | 6 (15) | 11 (16.2) | 11 (16.9) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Other | 9 (7.9) | 2 (4.9) | 7 (9.6) | 7 (10.8) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Surgical history | ||||||||

| Any prior pelvic surgery | 47 (41.6) | 15 (37.5) | 32 (43.8) | 0.55 | 30 (46.2) | 0 | 2 (40) | 0.46 |

| Prior hysterectomy | 25 (21.9) | 8 (19.5) | 21 (23.3) | 0.81 | 16 (24.6) | 0 | 1 (20) | 0.90 |

| Hormone use | ||||||||

| Any hormone use | 25 (21.9) | 7 (17.1) | 18 (24.7) | 0.48 | 17 (26.2) | 0 | 1 (20) | 0.67 |

| Vaginal hormone use | 18 (15.8) | 5 (12.2) | 13 (17.8) | 0.59 | 12 (18.5) | 0 | 1 (20) | 0.72 |

| Hormone prescribed at recruitment† | 9 (8.1) | 4 (10.3) | 5 (6.9) | 0.72 | 5 (7.8) | 0 | 0 | 0.86 |

| Frequency of pessary removal, n (%) | 0.72 | 0.44 | ||||||

| At least daily | 19 (16.7) | 7 (17.1) | 12 (16.4) | 10 (15.4) | 2 (66.7) | 0 | ||

| At least weekly | 74 (64.9) | 25 (61) | 49 (67.1) | 44 (67.7) | 1 (33.3) | 4 (80) | ||

| Less often than weekly | 17 (15.5) | 7 (17.9) | 10 (14.1) | 10 (15.6) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pessary required refitting or removal | ||||||||

| 2 wk | 17 (21.8) | 5 (19.7) | 12 (24) | 0.58 | 11 (22.7) | 1 (50) | 1 (25) | 0.61 |

| 3 mo | 21 (23.3) | 11 (34.4) | 10 (17.2) | 0.07 | 9 (17.3) | 0 | 1 (25) | 0.23 |

| Vaginal infection within last year | 6 (5.3) | 3 (7.3) | 3 (4.1) | 0.67 | 3 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 0.79 |

| Baseline vaginal symptoms | ||||||||

| Itching | 23 (21.3) | 11 (28.9) | 12 (17.1) | 0.22 | 11 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0.52 |

| Pain | 6 (5.6) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (7.1) | 0.42 | 4 (6.3) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0.15 |

| Discharge | 9 (7.9) | 2 (4.9) | 7 (9.6) | 0.49 | 6 (9.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0.45 |

| Vaginal sores | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.8) | 1.00 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Total Nugent score | 4.8 ± 2.1 | 5.1 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 2 | 0.23 | 4.6 ± 2 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 2.7 | 0.44 |

| BV by Nugent criteria | 30 (26.3) | 12 (29.3) | 18 (24.7) | 0.66 | 16 (24.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 0.68 |

| Randomized to TrimoSan gel | 58 (50.9) | 22 (53.7) | 36 (49.3) | 0.70 | 31 (47.7) | 3 (100) | 2 (40) | 0.37 |

No patients in this analysis identified as “black” or “African American” race because of changes in methodology from one study site to another and no person of this self-identified race/ethnicity was recruited at the study site where pessary satisfaction question was asked.

Indicates that patients were not previously using any oral or vaginal hormone therapy when recruited into the study but were prescribed hormone therapy (in all cases, vaginal therapy) at the time of pessary fitting. IQR, interquartile range.

For our primary outcome, we found that 61.4% (70/114) of all subjects in this analysis reported desire to continue pessary use at 3 months, with no significant difference seen between Hispanic and non-Hispanic women (24/41 [58.5%] vs 46/73 [63%], P = 0.69; OR, 0.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.38–1.81). This primary outcome analysis was corrected for BMI, education level, parity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and Trimosan gel randomization and again found to be nonsignificant (corrected OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.43–2.90; P = 0.82) (Table 2). However, Hispanic women had higher total Nugent scores (5.4 ± 2.3 vs 4.3 ± 2.1; coefficient, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.25–1.92; P = 0.02), higher prevalence of BV (34.1% vs 15.9%; OR, 2.73; 95% CI, 1.10–6.81; P = 0.04), and more vaginal pain (17.1% vs 2.8%; OR, 6.97; 95% CI, 1.24–72.2; P = 0.01) compared with non-Hispanic women after 3 months of pessary use (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Outcomes 3 Months After Pessary Fitting as Compared Between Self-Identified Ethnicities and Races

| Hispanic (n = 41), Mean ± SD or n (%) | Non-Hispanic (n = 73), Mean ± SD or n (%) | P Value by Ethnicity; Corrected P Value if Relevant | OR (95% CI); Corrected OR if Relevant | White (n = 65), Mean ± SD or n (%) | Hispanic (n = 41), Mean ± SD or n (%) | Asian (n = 4), Mean ± SD or n (%) | Other (n = 5), Mean ± SD or n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pessary satisfaction (Likert scale 3 or 4) | 24 (58.5) | 46 (63) | 0.69; corrected 0.82 | 0.83 (0.38–1.81); corrected 1.11 (0.43–2.90)* | 40 (61.5) | 24 (58.5) | 2 (66.7) | 4 (80) | 0.89 |

| Vaginal symptoms | |||||||||

| Itching | 7 (17.7) | 9 (12.5) | 0.58 | 1.44 (0.42–4.78) | 8 (12.5) | 7 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0.73 |

| Pain | 7 (17.1) | 2 (2.8) | 0.01; corrected 0.02 | 6.97 (1.24–72.2); corrected OR, 9.14 (1.37–61.17)* | 1 (1.6) | 7 (17.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0.02 |

| Discharge | 9 (22) | 12 (17.1) | 0.61 | 1.36 (0s.45–3.95) | 11 (17.1) | 9 (22) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0.92 |

| Vaginal sores | 3 (11.1) | 2 (4.8) | 0:37 | 2.47 (0.26–31.5) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0.23 |

| Total Nugent score | 5.4 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ±2.1 | 0.02; corrected 0.03 | Coefficient 1.09 (0.25–1.92); corrected 1.10 (0.10–2.10)† | 4.3 ± 2 | 5.4 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | 0.05 |

| BV by Nugent criteria | 14 (34.1) | 11 (15.9) | 0.04; corrected 0.049 | 2.73 (1.10–6.81); corrected 2.91 (1.01–8.39)* | 9 (14.5) | 14 (34.1) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (25) | 0.07 |

Values in bold indicates significant of P < 0.05.

Corrected OR by logistic regression, incorporating the covariates of BMI, parity, education level, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and TrimoSan gel treatment.

Corrected group difference by multiple linear regression, incorporating the covariates of BMI, parity, education level, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and TrimoSan gel treatment.

Significant variables identified on the univariate analysis for the outcome of pessary satisfaction were BMI, parity, education, and Charlson Comorbidity Index scores, so these were incorporated into the regression analyses for outcomes. Although nonsignificant on the univariate analysis, the randomization to TrimoSan gel was also incorporated into the regression analyses. Outcomes in the regression model included the primary outcome (desire to continue pessary use), BV prevalence, total Nugent score, and vaginal pain at 3 months, and none of these cofactors significantly altered the relationship between ethnicity and these outcomes (Table 2).

Comparison among individual races revealed no outcomes with significant differences (Table 2). Most notably, the desire to continue pessary use was similar across ethnicities for pessary use at 3 months after fitting (white, 40/65 [62%]; Hispanic, 24/41 [56%]; Asian, 2/4 [50%]; other, 4/5 [80%]; P = 0.89; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective secondary analysis of a prospective data set of women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders, we found that ethnicity and race had no significant effect on the desire to continue the pessary after 3 months. We did find that Hispanic women reported more vaginal pain, had higher prevalence of BV, and higher total Nugent scores at 3 months of pessary use as compared with non-Hispanic women. Despite a growing body of data demonstrating varying prevalence and care access for pelvic floor disorders based on ethnicity or race,12,21,22 women of various racial/ethnic backgrounds may consider pessaries for treatment of these disorders with similar patient-centered outcomes.

Although our study did not find differences in pessary outcomes between ethnic groups, other studies indicate that Hispanic women may view pelvic floor treatment differently.22 A large study found that women of Hispanic ethnicity were more likely than their white or African American counterparts to undergo surgery for POP despite similar socioeconomic status and treatment-seeking behavior.22 In past investigations of African American and white women, race was found to be a significant predictor for urinary incontinence, but not a factor in the prevalence or severity of POP.12,23 Although ethnic and racial differences in POP prevalence and treatment seeking may affect pessary indication, we found that pessary indication did not differ among women of various ethnicities. Our population may also consist of women who are very symptomatic, which eliminates differences between races that could exist in milder disease.13 These findings suggest that race/ethnicity may interact with other cofactors that affect POP bother and treatment choice but does not itself affect pessary continuation.

Our study is limited by the exclusion of women without English proficiency as well as unmeasured differences in care-seeking between races or ethnicities. It is well known that most women tend to experience lack of care access and poorer health outcomes even in disease states with similar prevalence between races.15–17 Lack of care access in women of Spanish-speaking Hispanic or non-white races may have biased patients included in our study. We were unable to correct for disease severity because of a mix of pessary use indications and because of the use of a post hoc power analysis. Our study cannot be powered to evaluate smaller differences, particularly between races with a small number of participants. In fact, this analysis included no African American or self-identifying black women.18 Studies confirm that African American women have worse health care disparities than do other populations,24,25 and we would have liked to report pessary outcomes in these women.

Strengths of this study include data from a randomized trial with prospective outcomes, allowing us to analyze and correct for possible confounders such as pessary indication, measures of socioeconomic status, and surrogates for health care access. Furthermore, this cohort was drawn from a population where the Hispanic patients are as prevalent as non-Hispanic women, were recruited from the same region, and get care at the same tertiary medical center, reducing some of the selection bias that plagues cohort studies on this topic. This study also provides a novel way to investigate patient desire to continue using pessary by direct query after use for a reasonable period, as opposed to limiting outcomes to care access and treatment choice and failing to explore treatment success.

In conclusion, this secondary analysis of a randomized trial found that Hispanic and non-Hispanic women report similar desire to continue pessary use 3 months after fitting. Although we found higher levels of microbiome disturbance and self-reported vaginal pain in Hispanic women, this was not associated with any differences in other vaginal symptoms or the desire for continued pessary use. Therefore, our study provides further evidence for providers that women of varied cultural and ethnic backgrounds are satisfied with pessaries for treatment of their pelvic floor disorder and are expected to continue use at the same rate as non-Hispanic, white women.

Acknowledgments

Gena Dunivan receives research support from Pelvalon and travel fees from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Rebecca Rogers receives royalties from UptoDate, travel fees and stipend from the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, travel fees from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to attend the Editorial Board Meeting for Obstetrics and Gynecology, travel fees and stipend from International Urogynecological Association for being the Editor in Chief of the International Urogynecology Journal, honorarium for being the Data and Safety Monitoring Board chair of the TRANSFORM trial sponsored by American Medical Systems.

The parent study was funded by a grant through the University of New Mexico Clinical Translational Science Center (Pilot Award 3A302A) and by the MedStar Washington Hospital Center funding for trainee investigator research.

Footnotes

The parent study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov under ID No. NCT01471457.

This abstract has been accepted for presentation at Pelvic Floor Disorders week 2018 to be held on October 9–13, 2018, in Chicago, IL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(1):141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA 2008;300(11):1311–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel M, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Impact of pessary use on prolapse symptoms, quality of life, and body image. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010; 202(5):499.e491–499.e494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung RY, Lee JH, Lee LL, et al. Vaginal pessary in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128(1):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, et al. A survey of pessary use by members of the American urogynecologic society. Obstet Gynecol 2000; 95(6 Pt 1):931–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, et al. Patient satisfaction and changes in prolapse and urinary symptoms in women who were fitted successfully with a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190(4):1025–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai SW, Yoon BS, Kwon JY, et al. Survey of the characteristics and satisfaction degree of the patients using a pessary. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2005;16(3):182–186; discussion 186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamers BH, Broekman BM, Milani AL. Pessary treatment for pelvic organ prolapse and health-related quality of life: a review. Int Urogynecol J 2011; 22(6):637–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenfelde S, Tell D, Thomas TN, et al. Quality of life in women who use pessaries for longer than 12 months. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2015;21(3):146–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Albuquerque Coelho SC, de Castro EB, Juliato CR. Female pelvic organ prolapse using pessaries: systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 2016;27(12): 1797–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaffer J, Nager CW, Xiang F, et al. Predictors of success and satisfaction of nonsurgical therapy for stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(1):91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graham CA, Mallett VT. Race as a predictor of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;185(1):116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunivan GC, Cichowski SB, Komesu YM, et al. Ethnicity and variations of pelvic organ prolapse bother. Int Urogynecol J 2014;25(1):53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver R, Thakar R, Sultan AH. The history and usage of the vaginal pessary: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;156(2): 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulley SP, Rasch EK, Chan L. Difference, disparity, and disability: a comparison of health, insurance coverage, and health service use on the basis of race/ethnicity among US adults with disabilities, 2006–2008. Med Care 2014;52(10 Suppl 3):S9–S16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HY, Ju E, Vang PD, et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparity among Asian American women: does race/ethnicity matter [corrected]? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(10):1877–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dehlendorf C, Anderson N, Vittinghoff E, et al. Quality and content of patient-provider communication about contraception: differences by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Womens Health Issues 2017; 27(5):530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meriwether KV, Rogers RG, Craig E, et al. The effect of hydroxyquinoline-based gel on pessary-associated bacterial vaginosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213(5):729.e721–729.e729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47(11):1245–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meriwether KV, Komesu YM, Craig E, et al. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med 2015;12(12):2339–2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitcomb EL, Rortveit G, Brown JS, et al. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(6):1271–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brazell HD, O’Sullivan DM, Tulikangas PK. Socioeconomic status and race as predictors of treatment-seeking behavior for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209(5):476.e471–476.e475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bump RC. Racial comparisons and contrasts in urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol 1993;81(3):421–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenthal L, Lobel M. Explaining racial disparities in adverse birth outcomes: unique sources of stress for black American women. Soc Sci Med 2011;72(6):977–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Hagiwara N, et al. An analysis of race-related attitudes and beliefs in black cancer patients: implications for health care disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016;27(3): 1503–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]