Key Points

Question

Can a multicomponent implementation intervention, including prompts in electronic health records, feedback on performance, and 6 months of practice facilitation, improve alcohol-related prevention and treatment in primary care?

Findings

In this stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial of 333 596 patients in primary care, the intervention increased alcohol screening, brief preventive alcohol counseling, new diagnosis of alcohol use disorders, and alcohol treatment initiation, but did not increase engagement in alcohol treatment compared with usual primary care.

Meaning

Medical care often neglects unhealthy alcohol use despite its effect on morbidity and mortality; this multicomponent implementation intervention increased preventive care, diagnosis, and treatment initiation for alcohol use disorders but not treatment engagement.

Abstract

Importance

Unhealthy alcohol use is common and affects morbidity and mortality but is often neglected in medical settings, despite guidelines for both prevention and treatment.

Objective

To test an implementation intervention to increase (1) population-based alcohol-related prevention with brief interventions and (2) treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD) in primary care implemented with a broader program of behavioral health integration.

Design, Setting, and Participants

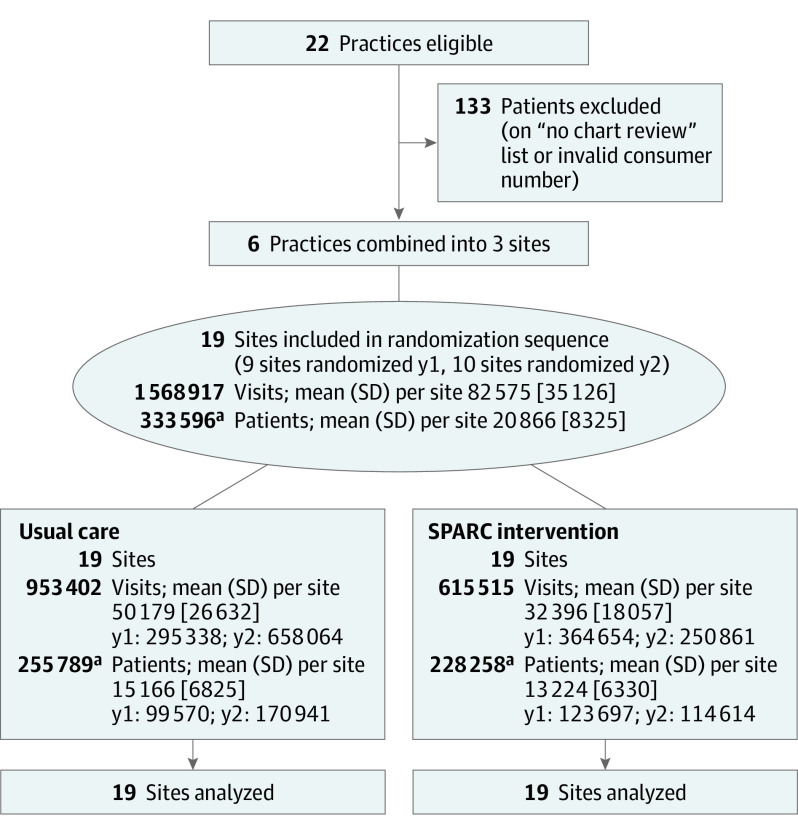

The Sustained Patient-Centered Alcohol-Related Care (SPARC) trial was a stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial, including 22 primary care practices in an integrated health system in Washington state. Participants consisted of all adult patients (aged ≥18 years) with primary care visits from January 2015 to July 2018. Data were analyzed from August 2018 to March 2021.

Interventions

The implementation intervention included 3 strategies: practice facilitation; electronic health record decision support; and performance feedback. Practices were randomly assigned launch dates, which placed them in 1 of 7 waves and defined the start of the practice’s intervention period.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Coprimary outcomes for prevention and AUD treatment were (1) the proportion of patients who had unhealthy alcohol use and brief intervention documented in the electronic health record (brief intervention) for prevention and (2) the proportion of patients who had newly diagnosed AUD and engaged in AUD treatment (AUD treatment engagement). Analyses compared monthly rates of primary and intermediate outcomes (eg, screening, diagnosis, treatment initiation) among all patients who visited primary care during usual care and intervention periods using mixed-effects regression.

Results

A total of 333 596 patients visited primary care (mean [SD] age, 48 [18] years; 193 583 [58%] female; 234 764 [70%] White individuals). The proportion with brief intervention was higher during SPARC intervention than usual care periods (57 vs 11 per 10 000 patients per month; P < .001). The proportion with AUD treatment engagement did not differ during intervention and usual care (1.4 vs 1.8 per 10 000 patients; P = .30). The intervention increased intermediate outcomes: screening (83.2% vs 20.8%; P < .001), new AUD diagnosis (33.8 vs 28.8 per 10 000; P = .003), and treatment initiation (7.8 vs 6.2 per 10 000; P = .04).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial, the SPARC intervention resulted in modest increases in prevention (brief intervention) but not AUD treatment engagement in primary care, despite important increases in screening, new diagnoses, and treatment initiation.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02675777

This stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial investigates an intervention to increase population-based alcohol-related prevention with brief interventions and treatment of alcohol use disorder in primary care.

Introduction

Unhealthy alcohol use—the spectrum from drinking above recommended limits to alcohol use disorder (AUD)—is neglected in medical settings despite its effect on morbidity and mortality.1,2,3,4 Of US adults, 20% to 25% drink at unhealthy levels,5 and 14% have a current AUD.6

Evidence-based prevention of unhealthy alcohol use includes population-based screening and brief counseling for unhealthy alcohol use (brief intervention) aimed at reducing drinking.1,7 Brief interventions are recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force1 and are ranked one of the highest prevention priorities based on potential improvement in population health.8 Evidence-based AUD treatment includes counseling9,10,11 and medications,11,12,13 and observational research supports the effectiveness of Alcoholics Anonymous.14 The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) recommends treatment initiation within 14 days of diagnosing AUD and treatment engagement within the following month.15 Despite the evidence for prevention and AUD treatment, most patients (approximately 90%) with unhealthy alcohol use do not receive recommended care.7,16,17,18,19

The Sustained Patient-Centered Alcohol-Related Care (SPARC) trial was a stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial with data collected from 2015 to 2018 and that was designed to improve (1) population-based alcohol-related prevention and (2) AUD treatment across 22 primary care practices (NCT02675777).20,21 The prevention objective was to test whether—compared with usual care—the SPARC intervention increased the proportion of primary care patients who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use and had documented brief intervention. The treatment objective was to test whether the intervention increased the proportion of primary care patients who were newly diagnosed with AUD and engaged in AUD treatment. This report presents the main trial results.

Methods

Study Setting, Design, and Sample

This stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial was conducted in Kaiser Permanente (KP) Washington, an integrated health system with 25 practices in Washington state where, prior to SPARC, no population-based systems supported routine alcohol screening and brief intervention or AUD diagnosis and treatment (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1).20,21 The trial included all 22 primary care practices not in the 3-practice SPARC pilot.20 The stepped-wedge design22,23,24 was chosen so that all practices would receive the intervention.21 Implementation of the intervention was led by KP Washington clinical leaders as a quality improvement initiative in partnership with researchers. Clinical leaders requested that the study simultaneously implement a broader program of behavioral health integration: screening and addressing depression, suicidality, and other drug use.20,21,25,26 Costs of implementation were reported earlier.27 All data were extracted from KP Washington electronic health records (EHRs) and insurance claims (data extraction dates: December 2018; pharmacy data, June 2019). The study protocol21 was approved by KP Washington’s institutional review board with a waiver of consent in accordance with 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Subtitle A § 46.116 and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization (Supplement 2). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for stepped wedge cluster randomized trials reporting guideline was followed.

The study sample included all patients who were at least 18 years old with a visit(s) to trial primary care practice(s) between January 1, 2015, and July 31, 2018. Each practice had a randomly assigned intervention launch date which placed the practice into 1 of 7 waves, with waves staggered by 4-month intervals.21 The months before and after the launch date are referred to as usual care and SPARC intervention periods, respectively.21 Patients could contribute data to usual care and/or SPARC intervention periods depending on when they visited primary care.

Intervention

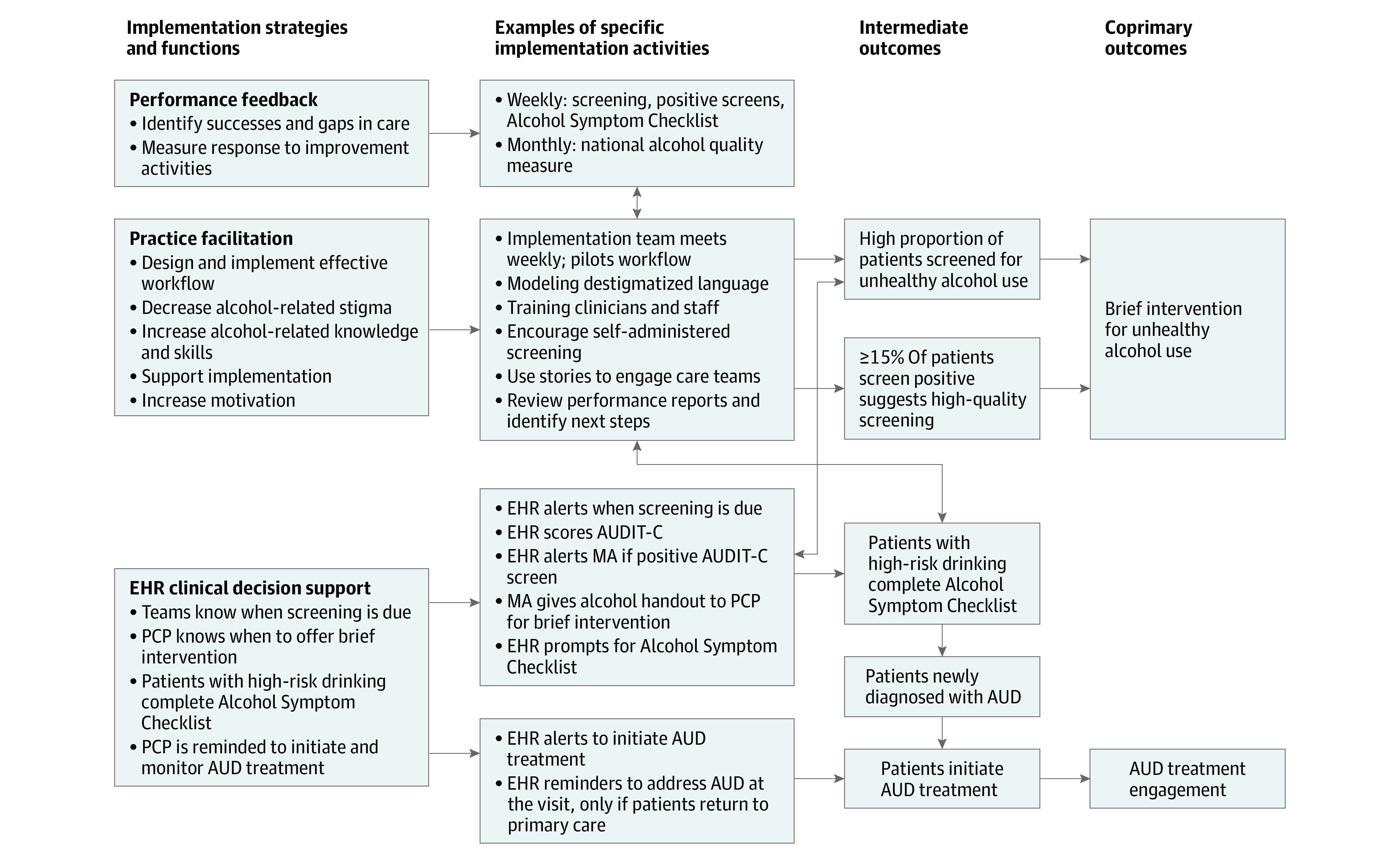

The SPARC intervention was designed to implement the following clinical care: population-based annual alcohol screening with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C),28 brief intervention for patients who screened positive (AUDIT-C ≥ 3 for women; AUDIT-C ≥ 4 for men),1 assessment with an Alcohol Symptom Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) (DSM-5) AUD if high-risk drinking (AUDIT-C ≥ 7),25,29,30 shared decision-making about AUD treatment options31 with a primary care practitioner or integrated licensed social worker,21 and support for initiation and engagement in AUD treatment (Figure 1; eAppendix 232 in Supplement 1). The intervention included 3 evidence-based implementation strategies (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1).20,21 Two strategies—EHR clinical decision support and performance feedback—were used previously in the Veterans Health Administration for implementing alcohol-related prevention,33 and the third—practice facilitation34—was added to address limitations of those prior Veterans Affairs implementation efforts.35 Practice facilitation supported local implementation teams at each practice for approximately 6 months—2 months before randomly assigned launch dates (preparation phase) and 4 months after launch (active support phase). Local implementation teams, including leaders, clinicians, and staff, had weekly meetings with a practice facilitator using Plan-Do-Check-Adjust (PDCA) cycles. Practice facilitators offered expertise in alcohol-related care, addressed stigma, encouraged patient-centered shared decision-making for AUD,31 and provided and/or arranged trainings to address all elements of behavioral health integration: a 1-hour orientation for all primary care staff, and separate 1-hour trainings for primary care practitioners and nurses, and medical assistants and front desk staff. The EHR clinical decision support included EHR prompts for screening, assessment of AUD symptoms, and treatment initiation; there was inadequate leadership support to include prompts for practitioners to document brief intervention or engage patients in treatment. The target date for activating EHR prompts was the randomized launch date. Performance feedback reported on the prevalence of screening and assessment of AUD symptoms, calculated weekly by study programmers starting after intervention launch,20,21 and NCQA treatment initiation metrics starting 2 months after intervention launch. Throughout the trial, formative evaluation meetings with practice facilitators identified barriers and facilitators leading to refinements of implementation activities.20,21 After practice facilitation ended (sustainment phase), health system leaders conducted monthly PDCA cycle meetings with each practice.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Function and Format of SPARC Intervention and Hypothesized Effect With Intermediate and Coprimary Outcomes.

This figure describes the 3 implementation strategies and functions (performance feedback, practice facilitation, and EHR clinical decision support), examples of specific implementation activities for the implementation strategies, and hypothesized effects with intermediate outcomes as well as the 2 coprimary outcomes (1) brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use and (2) AUD treatment engagement. Arrows represent connected strategies/functions, activities, and intermediate and coprimary outcomes. AUD indicates alcohol use disorder; EHR, electronic health record; MA, medical assistant; PCP, primary care practitioner; SPARC, Sustained Patient-Centered Alcohol-Related Care.

Randomization

The 22 practices were randomized as 19 sites because clinical leaders requested that 3 pairs of nearby practices be randomized together as 3 sites. Randomization was stratified by year: year 1 (y1) sites were randomized into 3 waves; year 2-3 (y2) sites were randomized later (after study start) into 4 waves. The study biostatistician completed stratified random assignment using a computer-generated list of random numbers; within each year (y1 vs y2), each site had equal probability of assignment to each wave. (Blinding clinics was not possible.)21

Measures

The SPARC trial had coprimary implementation outcomes reflecting processes of care, one for prevention and one for AUD treatment, and multiple secondary explanatory outcomes. All outcomes were defined using a denominator of all patients with an in-person primary care visit each month (consecutive 28-day periods) to avoid identification bias.20,21,36,37

Primary Outcome Measures

Brief Intervention

The numerator for the primary outcome for prevention (hereafter referred to as brief intervention) was the presence of both a positive alcohol screen (defined previously) on the day of a primary care visit or in the prior year and EHR-documented brief intervention within the next 14 days. Brief intervention was identified by 1 or more of 3 EHR data elements available in usual care and SPARC intervention periods (eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1): International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or Tenth Revision (ICD-9/ICD-10) diagnostic or procedure codes for brief intervention; clinical documentation of brief intervention templates identified by natural language processing and confirmed by manual review; and orders for a booklet about unhealthy alcohol use.38

Treatment Engagement for AUD

The numerator for the primary outcome for AUD treatment was the presence of both a new AUD diagnosis on the day of a primary care visit (with no AUD diagnosis in the prior 365 days) and subsequent in-person treatment initiation and engagement. Initiation required an ICD-9/ICD-10 code from NCQA’s alcohol or drug quality measure15 within 14 days after the new AUD diagnosis; engagement required 2 more visits with alcohol or drug ICD-9/ICD-10 codes within 30 days following initiation.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Secondary intermediate outcomes identified a priori included AUDIT-C screening; positive screens; high positive screens that prompted assessment with an Alcohol Symptom Checklist; completion of an Alcohol Symptom Checklist; new AUD diagnoses, and AUD treatment initiation.21 In addition, alternative measures of brief intervention and AUD treatment (including medications) were evaluated (eAppendix 4 in Supplement 1).15,20,21,39

Covariates

Patient-level covariates were defined on the day of the first visit during usual care or SPARC intervention period(s). These covariates included age; sex; race and ethnicity; insurance type and ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnosis codes in the prior year; and the visit date. We describe race and ethnicity, along with other patient characteristics in Table 1, to allow readers to understand the generalizability of our findings to other samples with different demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1. Comparison of Patients With Visits in Usual Care and SPARC Intervention Periods.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Usual care | SPARC intervention | |

| Total No. of patientsa | 255 789 (100) | 228 258 (100) |

| No. of visits, mean (SD) | 3.73 (3.75) | 2.70 (2.62) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 49.30 (18.10) | 50.20 (18.09) |

| Sexb | ||

| Female | 149 557 (58.5) | 135 426 (59.3) |

| Male | 106 231 (41.5) | 92 830 (40.7) |

| Hispanic or Latinx/e | 15 086 (5.9) | 13 362 (5.9) |

| Unknown | 9883 (3.9) | 11 695 (5.1) |

| Racec | ||

| Asian | 24 806 (9.7) | 24 866 (10.9) |

| Black or African American | 14 679 (5.7) | 12 525 (5.5) |

| Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2783 (1.1) | 2346 (1.0) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 2042 (0.8) | 1635 (0.7) |

| White | 184 654 (72.2) | 160 764 (70.4) |

| Multiracial | 7932 (3.1) | 6749 (3.0) |

| Otherd | 9212 (3.6) | 8619 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 9681 (3.8) | 10 754 (4.7) |

| Needs interpreter at medical visits | 7694 (3.0) | 7600 (3.3) |

| Insurance type | ||

| Commercial | 156 019 (61.0) | 128 711 (56.4) |

| Medicaid | 9267 (3.6) | 7054 (3.1) |

| Medicare | 58 093 (22.7) | 54 559 (23.9) |

| Other | 8350 (3.3) | 7085 (3.1) |

| Private pay | 24 060 (9.4) | 30 849 (13.5) |

| Tobacco usee | 28 021 (11.0) | 22 578 (9.9) |

| Conditions, symptoms, or behaviors, past yearf | ||

| Alcohol use disorder | 3364 (1.3) | 2902 (1.3) |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1293 (0.5) | 1019 (0.4) |

| Drug use disorder | 937 (0.4) | 610 (0.3) |

| Opioid use disorder | 1391 (0.5) | 1315 (0.6) |

| Stimulant use disorder | 382 (0.1) | 385 (0.2) |

| Depression | 43 358 (17.0) | 40 087 (17.6) |

| Anxiety | 32 666 (12.8) | 32 420 (14.2) |

| Eating disorder | 570 (0.2) | 611 (0.3) |

| Serious mental illness | 5707 (2.2) | 4265 (1.9) |

| Attention deficit disorder | 5292 (2.1) | 4492 (2.0) |

| Insomnia | 14 404 (5.6) | 10 300 (4.5) |

| Other mental health conditions | 1540 (0.6) | 454 (0.2) |

| Cardiovascular conditionsg | 66 218 (25.9) | 65 330 (28.6) |

| Gastrointestinal conditionsh | 3313 (1.3) | 2909 (1.3) |

| Diabetes | 25 097 (9.8) | 22 958 (10.1) |

| Kidney disease | 14 062 (5.5) | 10 015 (4.4) |

| Canceri | 7395 (2.9) | 7200 (3.2) |

| Pain conditions | 127 020 (49.7) | 130 567 (57.2) |

Abbreviation: SPARC, Sustained Patient-Centered Alcohol-Related Care.

Patients could have a visit in both periods (total No. of patients with a visit = 333 596; No. of patients with visits in both periods = 150 451).

Unknown sex: 1 patient in usual care period and 2 patients in SPARC intervention period.

Race and ethnicity were described to allow readers to understand the generalizability of these findings to other samples with different demographic and clinical characteristics.

Patient self-identified by choosing “other” from a list of options.

Unknown tobacco use: 23 996 (9.4%) in usual care period and 21 771 (9.5%) in SPARC intervention period.

All conditions, symptoms, or behaviors were in the year prior to each patient’s initial primary care visit, including the day of the visit, except for alcohol, cannabis, drug, opioid, and stimulant use disorders which include only active use disorders (excluding remission) in the year prior to each patient’s initial primary care visit.

Cardiovascular conditions include hypertension, myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, and cardiovascular disease.

Gastrointestinal conditions include liver disease, peptic ulcer disease and hepatitis C, and pancreatitis.

Cancer includes any malignant neoplasm.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described in the SPARC intervention and usual care periods, and by allocated sequence (ie, wave; eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Crossover of patients from SPARC to usual care periods was described.

Following prespecified analysis plans,21 primary analyses compared outcome rates during 1-month intervals in usual care and SPARC periods across all 19 sites. Specifically, binary indicators for whether a patient seen in primary care at a site during a particular month had an outcome in that month were modeled using mixed-effects logistic regression models.21 The models included an indicator for whether the site was in the usual care or SPARC intervention period in that month, and adjusted for stratification (y2 vs y1) and calendar time (indicator variable for each 4 months). Additionally, person-level and site-level random effects accounted for correlation of repeated outcomes from the same patient (eg, in multiple months) and the same site (eAppendix 5 in Supplement 1). The marginal predicted probability of each outcome during usual care and SPARC intervention periods was estimated by applying marginal standardization40 to average over the observed covariate distribution and the estimated random effects.41 Monthly outcome rates are reported as percentages or values per 10 000 patients. A 2-sided significance threshold of P < .05 was used. Statistical analyses were conducted in R statistical software, version 3.5.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing). Data were analyzed from August 2018 to March 2021.

Statistical Power

Estimated power, with 19 sites across 7 study waves staggered at 4-month intervals, was 80% to detect an absolute increase in brief intervention rates of 7.1 per 10 000 patients seen and an increase in treatment engagement of 2.6 per 10 000 patients seen (Supplement 2).

Results

During the study period, 333 596 patients (mean [SD] age, 48 [18] years; 193 583 female [58%]; 234 764 White individuals [70%]) made 1 568 917 visits to participating primary care practices (Table 1). Overall, 255 789 and 228 258 patients were seen during usual care and SPARC intervention periods, respectively (Figure 2). The majority of patient visits during the SPARC intervention period were during the sustainment phase after active implementation ended (78% of patients-months). Crossover was minimal; among 7456 patients with a visit to a site during the SPARC intervention, 2.2% had a later visit to a different site still in the usual care period.

Figure 2. CONSORT Diagram of Sites.

The figure is the CONSORT flow diagram for the SPARC trial, a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial, depicting enrollment/eligible sites, randomized number of clusters, allocation, and data analysis.

aPatients could have a visit in both usual care and SPARC periods (number of patients in both periods = 150 451).

Prevention

The proportion of primary care patients with brief intervention documented in the EHR was greater for patients during the SPARC intervention period compared with usual care (Table 2): 57 vs 11 per 10 000 patients (P < .001). Sensitivity analyses using alternative specifications for brief intervention (eTable 2 in Supplement 1) and varying assumptions in statistical modeling (eTable 4 in Supplement 1) did not change findings meaningfully. All secondary intermediate prevention outcomes were higher in patients seen during the intervention period compared with usual care (Table 2), notably: 83.2% vs 20.8% of patients had alcohol screening documented (P < .001), and 18.0% vs 5.0% of patients had a positive alcohol screen (P < .001).

Table 2. Comparison of Prevention for Unhealthy Alcohol Use During the Usual Care and SPARC Intervention Periods.

| Variable | Usual carea | SPARC interventiona | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of patients | |||

| Screening for unhealthy alcohol use documentedc | 20.8 | 83.2 | <.001d |

| Screened positive most recent visite | 5.0 | 18.0 | <.001 |

| No. of patients per 10 000 | |||

| High positive screen most recent visitf | 54 | 148 | <.001 |

| Coprimary outcome: brief intervention within 14 dg | 11 | 57 | <.001 |

Abbreviation: SPARC, Sustained Patient-Centered Alcohol-Related Care.

Marginal predicted probabilities were estimated from the primary logistic mixed-effects model using marginal standardization, and then multiplied by 10 000 to obtain monthly outcome rates per 10 000 patients seen in the site.

P values were obtained from a 2-sided Wald test of the adjusted odds ratio comparing monthly rates during the SPARC intervention (78% during sustainment) vs usual care periods obtained from the primary logistic mixed-effects model.

Screening for unhealthy alcohol use documented meant that patients had an alcohol screen (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption [AUDIT-C]) at the visit or in prior year.

Estimates and P values for screening are reported from the corresponding logistic regression model that did not include any random effects, as the mixed-effects model did not converge (details in eAppendix 5 in Supplement 1).

Screened positive most recent visit meant that patients had an AUDIT-C score of at least 3 in women or at least 4 in men on the most recent screen at the visit or in the prior year.

High positive screen most recent visit meant that patients had an AUDIT-C score of at least 7 on the most recent screen at the visit or in the prior year.

Brief intervention within 14 days (main outcome) meant that patients screened positive and had documented brief intervention (see article text and eAppendix 3 in Supplement 1 for definition of brief intervention) at the visit or within 14 days after the visit.

AUD Treatment

The proportion of primary care patients with AUD treatment engagement did not differ during the SPARC intervention and usual care periods (Table 3): 1.4 vs 1.8 per 10 000 patients, respectively (P = .30). Sensitivity analyses using alternative definitions of treatment engagement, including medications (eTable 3 in Supplement 1), and varying statistical assumptions (eTable 4 in Supplement 1) did not change findings meaningfully. However, all secondary intermediate treatment outcomes were significantly higher during the SPARC intervention period compared with usual care (Table 3): 80.9 vs 4.1 per 10 000 patients were assessed with a DSM-5 Alcohol Symptom Checklist (P < .001); 33.8 vs 28.8 per 10 000 patients had new AUD diagnoses documented (P = .003); and 7.8 vs 6.2 patients per 10 000 initiated AUD treatment (P = .04).

Table 3. Comparison of Treatment for Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) During the Usual Care and SPARC Intervention Periods.

| Variable, No. of patients per 10 000 | Usual carea | SPARC interventiona | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-5 alcohol symptom checklist documentedc | 4.1 | 80.9 | <.001 |

| New AUD diagnosisd | 28.8 | 33.8 | .003 |

| AUD treatment initiatione | 6.2 | 7.8 | .04 |

| Coprimary outcome: AUD treatment engagementf | 1.8 | 1.4 | .30 |

Abbreviation: DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition); SPARC, Sustained Patient-Centered Alcohol-Related Care.

Marginal predicted probabilities were estimated from the primary logistic mixed-effects model using marginal standardization, and then multiplied by 10 000 to obtain monthly outcome rates per 10 000 patients seen in a site, which are the numbers reported here.

P values are obtained from a 2-sided Wald test of the adjusted odds ratio comparing monthly rates during the SPARC Intervention (78% during sustainment) vs usual care periods obtained from the primary logistic mixed-effects model.

DSM-5 Alcohol Symptom Checklist documented meant that patients had a high positive alcohol screen (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption [AUDIT-C] score of at least 7) at the visit or in the prior year and a DSM-5 Alcohol Symptom Checklist documented at the visit or in the prior year.

New AUD diagnosis meant that International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or Tenth Revision (ICD-9/ICD-10) code for an AUD documented at the visit and no AUD diagnosis in prior year.

AUD treatment initiation meant that a new AUD diagnosis was documented at a visit and treatment was documented in a separate visit on the day of diagnosis or within 14 days after the visit (see article text for definition of treatment).

AUD treatment engagement (main outcome) meant that AUD treatment was initiated with 2 more treatment visits in the 30 days following initiation.

Discussion

This stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial tested whether a practical, affordable27 implementation intervention—compared with usual primary care—could increase alcohol-related preventive care and AUD treatment engagement. The SPARC intervention increased brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use—the primary outcome for prevention. The intervention did not increase the proportion of patients who engaged in 3 visits addressing AUD, the primary treatment outcome, but it did increase new AUD diagnoses and AUD treatment initiation—important prespecified intermediate outcomes on the pathway to AUD treatment engagement (Figure 1). The SPARC trial is the first implementation trial, to our knowledge, to increase brief intervention, AUD diagnosis, and initiation of AUD treatment in primary care settings without the addition of research-supported clinicians.42,43,44,45,46 However, the absolute magnitudes of increases were relatively small.

Population-based alcohol screening is foundational to alcohol-related prevention and treatment in primary care, and the success of SPARC is notable.47,48 Even successful implementation trials in primary care settings have often resulted in low screening rates (eg, less than 10%).49,50 Although systematic reviews,49 observational studies,33 and 1 prior trial of implementation strategies51 suggest EHR clinical decision support and performance feedback may result in high rates of alcohol screening (51%-93%), this can also result in poor-quality screening35 with nonstandard administration of screens and stigma leading to a low prevalence of positive screens.33,52,53 To address these challenges,20,21 SPARC added practice facilitation to EHR clinical decision support and performance feedback to support standardized integration of screening into workflow, address stigma and gaps in knowledge, and ensure iterative quality improvement by local implementation teams. The SPARC trial also implemented alcohol screening along with other behavioral health screening. This practical,33,54,55,56,57,58,59 affordable27 approach achieved high screening rates (83.2%), as well as expected prevalence of positive screens (18.0%), indicating sustained high-quality screening.

Implementation of brief intervention has been even more challenging than screening, despite its recognized efficacy.1,60 The SPARC trial significantly increased brief interventions, but the proportion of primary care patients with documented brief intervention was still relatively low (0.57%). However, this was comparable to the study group in the ADVISe trial that increased brief intervention (0.63%), the only other US randomized clinical implementation trial of brief intervention in a broad, naturalistic primary care population, to our knowledge.51 Importantly, ADVISe’s population-based brief intervention rate reflects a low screening rate (9.2% of 218 667 patients) combined with a higher rate of brief intervention among patients with positive alcohol screens (44%), whereas SPARC had a high screening rate (83.2% of 228 258 patients) and a brief intervention rate of 3.2%. The higher brief intervention rate likely reflected EHR prompts and performance feedback for brief intervention in ADVISe combined with 6.5 hours of alcohol-focused training for primary care practitioners,51 strategies supported by prior research.60,61,62,63,64,65,66 The SPARC trial did not have EHR prompts facilitating documentation or performance feedback of brief intervention due to concerns that practitioners might focus on documentation, not counseling.67 The SPARC trial also had limited primary care practitioner training time. The EHR prompts, performance feedback, and added training in brief intervention will likely be critical as health systems seek to meet new national performance measures for brief intervention.39,68

The SPARC trial significantly increased newly documented AUD diagnoses and treatment initiation. This is important because of the low rates of treatment of AUD in the US.19 While care managers can increase AUD treatment,42,43,44,45,46 no prior randomized clinical trial, to our knowledge, has tested a primary care implementation intervention designed to increase AUD treatment without adding specialized staff. Further, SPARC took a novel approach. Often, experts recommend second alcohol screens for AUD after an initial brief screen indicates unhealthy alcohol use69,70 followed by referral.11 However, many patients do not accept referral,45,46 and this approach has not been shown to increase AUD treatment.71,72,73 Systematic assessment, diagnosis, and initiation of treatment in primary care may be more effective. Therefore, in SPARC, when patients reported high-risk drinking, the EHR prompted medical assistants to administer an Alcohol Symptom Checklist.25,29,30 Patient responses on the Alcohol Symptom Checklist provided clinicians with timely information on the presence and severity of 11 DSM-5 AUD symptoms to aid engagement (for example, “you indicated you tried to cut down but been unable, can you tell me about that?”)25 and patient-centered shared decision-making.31 Social workers trained in shared decision-making for AUD also supported primary care and provided proactive outreach to patients with new AUD.21 Increases in AUD diagnosis and treatment initiation in SPARC suggest this is a promising approach.

Despite these achievements, increases in AUD diagnosis and treatment initiation were small, and SPARC did not improve treatment engagement. Several elements likely contributed. First, as with brief intervention, many practitioners likely need targeted training to comfortably discuss and manage AUD.51,74,75 In SPARC, primary care practitioners were only available for 2 hours of training that covered all of behavioral health integration. Second, while the EHR prompted practitioners to initiate treatment when making new AUD diagnoses, there were no prompts to schedule subsequent AUD treatment engagement. Third, at the time of the trial, NCQA measures for AUD15 were not a major focus of primary care quality improvement in the study’s health system. Finally, it is likely easier to initiate a single follow-up visit than engage patients in ongoing AUD treatment, especially if patients are hesitant about treatment or have other barriers or competing demands.76

Taken as a whole, the SPARC trial showed that EHR prompts and performance feedback for alcohol screening, assessment, and AUD treatment initiation, combined with practice facilitation that addressed stigma and knowledge gaps while guiding local teams in weekly PDCA cycle meetings, markedly and sustainably increased screening and assessment, a critical first step toward improving alcohol-related care.47,48 However, relatively small gains in brief intervention and treatment initiation were achieved, and no increase in treatment engagement was demonstrated. Further improvements will likely require additional EHR support77 and iterative quality improvement processes focused specifically on brief intervention and AUD treatment engagement.

Limitations

The SPARC trial had several limitations. Measures relied on EHR documentation and insurance claims. Patient self-report measures are likely more valid than EHR measures,67,78 and EHR measures and claims likely missed undocumented brief intervention as well as AUD treatment (eg, if patients self-paid or used employee assistance programs). The SPARC trial only measured processes of care; the effect on patient outcomes is unknown. In addition, stepped-wedge trials can be confounded by temporal changes.79,80 Practice facilitators in SPARC had alcohol-related expertise,21 and SPARC was conducted in a single regional integrated health plan and delivery system with a shared EHR and a predominantly White insured population. These and other factors potentially limited SPARC’s generalizability. At the same time, SPARC had important strengths. The trial was designed to avoid identification bias81,82 and also used efficient, affordable27 evidence-based implementation strategies20,21 in a health system with no integrated behavioral health care and limited primary care support for alcohol-related care at trial start.

Conclusions

This stepped-wedge cluster randomized implementation trial succeeded in increasing several important elements of evidence-based alcohol-related preventive care—systematic screening and brief intervention—as well as increasing assessment of DSM-5 symptoms of AUD, new AUD diagnoses, and treatment initiation. However, the magnitude of increases in brief intervention and AUD treatment initiation were modest, and AUD treatment engagement was not increased. Given the extent of the gaps in the quality of alcohol-related care, iterative quality improvement efforts will likely be needed.

eAppendix 1. Usual Care Condition

eAppendix 2. Detailed conceptual model of function and format of SPARC intervention and hypothesized effect with intermediate and co-primary outcomes

eAppendix 3. Alcohol Brief Intervention Sources and Natural Language Processing Identification of Brief Intervention

eAppendix 4. Definitions on Sensitivity Outcome Measures

eTable 1. Characteristics of patients with visits to sites randomized to different study waves within each stratum (Year 1 vs. Years 2-3 sites)

eTable 2. Prevention outcomes: parameter estimates under primary, secondary, explanatory, and sensitivity analysis measures

eTable 3. Treatment outcomes: parameter estimates under primary, secondary, explanatory, and sensitivity analysis measures

eTable 4. Parameter estimates for prevention and treatment outcomes under sensitivity analyses fitting generalized linear models

eReferences

Trial protocol

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. ; US Preventive Services Task Force . Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1899-1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General . Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. HHS; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators . The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(12):987-1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer MR, Curtin SC, Garnett MF. Alcohol-induced death rates in the United States, 2019-2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;(448):1-8. doi: 10.15620/cdc:121795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saitz R. Clinical practice: unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596-607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donroe JH, Edelman EJ. Alcohol use. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(10):ITC145-ITC160. doi: 10.7326/AITC202210180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maciosek MV, LaFrance AB, Dehmer SP, et al. Updated priorities among effective clinical preventive services. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(1):14-22. doi: 10.1370/afm.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCrady BS. Health-care reform provides an opportunity for evidence-based alcohol treatment in the USA: the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline as a model. Addiction. 2013;108(2):231-232. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll KM. Dissemination of evidence-based practices: how far we’ve come, and how much further we’ve got to go. Addiction. 2012;107(6):1031-1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03755.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry C, Liberto J, Milliken C, et al. ; VA/DoD Guideline Development Group . The management of substance use disorders: synopsis of the 2021 US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(5):720-731. doi: 10.7326/M21-4011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(8):815-824. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3(3):CD012880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Quality Assurance . Initiation and engagement of alcohol and other drug abuse or dependence treatment (IET). Accessed December 4, 2018. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/initiation-and-engagement-of-alcohol-and-other-drug-abuse-or-dependence-treatment/

- 16.Weisner C, Campbell CI, Altschuler A, et al. Factors associated with Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) alcohol and other drug measure performance in 2014-2015. Subst Abus. 2019;40(3):318-327. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2018.1545728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders . Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park-Lee E, Lipari RN, Hedden SL, Kroutil LA, Porter JD. Receipt of services for substance use and mental health issues among adults: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. 2017. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DR-FFR2-2016/NSDUH-DR-FFR2-2016.htm [PubMed]

- 19.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635-2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bobb JF, Lee AK, Lapham GT, et al. Evaluation of a pilot implementation to integrate alcohol-related care within primary care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(9):1030. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14091030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glass JE, Bobb JF, Lee AK, et al. Study protocol: a cluster-randomized trial implementing Sustained Patient-centered Alcohol-related Care (SPARC trial). Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0795-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemming K, Carroll K, Thompson J, Forbes A, Taljaard M; SW-CRT Review Group . Quality of stepped-wedge trial reporting can be reliably assessed using an updated CONSORT: crowd-sourcing systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;107:77-88. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemming K, Taljaard M, Forbes A. Modeling clustering and treatment effect heterogeneity in parallel and stepped-wedge cluster randomized trials. Stat Med. 2018;37(6):883-898. doi: 10.1002/sim.7553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemming K, Taljaard M, McKenzie JE, et al. Reporting of stepped wedge cluster randomised trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement with explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2018;363:k1614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayre M, Lapham GT, Lee AK, et al. Routine assessment of symptoms of substance use disorders in primary care: prevalence and severity of reported symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1111-1119. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05650-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards JE, Bobb JF, Lee AK, et al. Integration of screening, assessment, and treatment for cannabis and other drug use disorders in primary care: an evaluation in three pilot sites. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:134-141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung K, Richards J, Goemer E, et al. Costs of using evidence-based implementation strategies for behavioral health integration in a large primary care system. Health Serv Res. 2020;55(6):913-923. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208-1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hallgren KA, Matson TE, Oliver M, Caldeiro RM, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Practical assessment of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder criteria in routine care: high test-retest reliability of an Alcohol Symptom Checklist. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(3):458-467. doi: 10.1111/acer.14778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallgren KA, Matson TE, Oliver M, et al. Practical assessment of alcohol use disorder in routine primary care: performance of an Alcohol Symptom Checklist. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):1885-1893. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradley KA, Kivlahan DR. Bringing patient-centered care to patients with alcohol use disorders. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1861-1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esmail LC, Barasky R, Mittman BS, Hickam DH. Improving comparative effectiveness research of complex health interventions: standards from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(Suppl 2)(suppl 2):875-881. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06093-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Volpp B, Collins BJ, Kivlahan DR. Implementation of evidence-based alcohol screening in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(10):597-606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63-74. doi: 10.1370/afm.1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradley KA, Lapham GT, Hawkins EJ, et al. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):299-306. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1509-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eldridge S, Kerry S, Torgerson DJ. Bias in identifying and recruiting participants in cluster randomised trials: what can be done? BMJ. 2009;339:b4006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldridge S, Campbell M, Campbell M, et al. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2): additional considerations for cluster-randomized trials (RoB 2 CRT). March 2021. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yDQtDkrp68_8kJiIUdbongK99sx7RFI-/view

- 38.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Rethinking drinking: alcohol and your health. 2009. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://permanent.fdlp.gov/lps115216/Rethinking-Drinking.pdf

- 39.National Committee for Quality Assurance . Unhealthy alcohol use screening and follow-up. Accessed June 2022. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/unhealthy-alcohol-use-screening-and-follow-up/

- 40.Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):962-970. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlou M, Ambler G, Seaman S, Omar RZ. A note on obtaining correct marginal predictions from a random intercepts model for binary outcomes. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:59. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0046-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1156-1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1480-1488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradley KA, Bobb JF, Ludman EJ, et al. Alcohol-related nurse care management in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):613-621. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto SA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):162-168. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2625-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willenbring ML, Olson DH. A randomized trial of integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(16):1946-1952. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.16.1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chatterton B, Agnoli A, Schwarz EB, Fenton JJ. Alcohol screening during US primary care visits, 2014-2016. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(15):3848-3852. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07369-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Denny CH, Hungerford DW, McKnight-Eily LR, et al. Self-reported prevalence of alcohol screening among US adults. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(3):380-383. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams EC, Johnson ML, Lapham GT, et al. Strategies to implement alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: a structured literature review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25(2):206-214. doi: 10.1037/a0022102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson P, Coulton S, Kaner E, et al. Delivery of brief interventions for heavy drinking in primary care: outcomes of the ODHIN 5-country cluster randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):335-340. doi: 10.1370/afm.2051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mertens JR, Chi FW, Weisner CM, et al. Physician versus non-physician delivery of alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment in adult primary care: the ADVISe cluster randomized controlled implementation trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13722-015-0047-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Thomas RM, et al. Factors underlying quality problems with alcohol screening prompted by a clinical reminder in primary care: a multi-site qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1125-1132. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3248-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Local implementation of alcohol screening and brief intervention at five veterans health administration primary care clinics: perspectives of clinical and administrative staff. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:27-35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lapham GT, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Med Care. 2012;50(2):179-187. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, Lehmann L. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):83-90. doi: 10.1037/a0020130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Szymanski BR, et al. Initiation of Primary Care–Mental Health Integration programs in the VA Health System: associations with psychiatric diagnoses in primary care. Med Care. 2010;48(9):843-851. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e5792b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kirchner J, Edlund CN, Henderson K, Daily L, Parker LE, Fortney JC. Using a multi-level approach to implement a primary care mental health (PCMH) program. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28(2):161-174. doi: 10.1037/a0020250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, Fortney JC. Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(Suppl 4)(suppl 4):904-912. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3027-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krist AH, Glasgow RE, Heurtin-Roberts S, et al. ; MOHR Study Group . The impact of behavioral and mental health risk assessments on goal setting in primary care. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(2):212-219. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0384-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers: a randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1039-1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540370029032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bray JW, Del Boca FK, McRee BG, Hayashi SW, Babor TF. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT): rationale, program overview and cross-site evaluation. Addiction. 2017;112(suppl 2):3-11. doi: 10.1111/add.13676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McNeely J, Adam A, Rotrosen J, et al. Comparison of methods for alcohol and drug screening in primary care clinics. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110721-e2110721. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dzidowska M, Lee KSK, Wylie C, et al. A systematic review of approaches to improve practice, detection and treatment of unhealthy alcohol use in primary health care: a role for continuous quality improvement. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-1101-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rose HL, Miller PM, Nemeth LS, et al. Alcohol screening and brief counseling in a primary care hypertensive population: a quality improvement intervention. Addiction. 2008;103(8):1271-1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ornstein SM, Miller PM, Wessell AM, Jenkins RG, Nemeth LS, Nietert PJ. Integration and sustainability of alcohol screening, brief intervention, and pharmacotherapy in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(4):598-604. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saitz R, Horton NJ, Sullivan LM, Moskowitz MA, Samet JH. Addressing alcohol problems in primary care: a cluster randomized, controlled trial of a systems intervention—the screening and intervention in primary care (SIP) study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(5):372-382. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-5-200303040-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berger D, Lapham GT, Shortreed SM, et al. Increased rates of documented alcohol counseling in primary care: more counseling or just more documentation? J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):268-274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4163-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Quality Forum . Preventive care and screening: unhealthy alcohol use: screening & brief counseling. 2019. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_quality_measure_specifications/CQM-Measures/2019_Measure_431_MIPSCQM.pdf

- 69.Vinson DC, Kruse RL, Seale JP. Simplifying alcohol assessment: two questions to identify alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(8):1392-1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00440.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide (updated 2005 edition). 2005. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/clinicianGuide/guide/intro/data/resources/Clinicians%20Guide.pdf

- 71.Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Specialty substance use disorder services following brief alcohol intervention: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Addiction. 2015;110(9):1404-1415. doi: 10.1111/add.12950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glass JE, Hamilton AM, Powell BJ, Perron BE, Brown RT, Ilgen MA. Revisiting our review of Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): meta-analytical results still point to no efficacy in increasing the use of substance use disorder services. Addiction. 2016;111(1):181-183. doi: 10.1111/add.13146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frost MC, Glass JE, Bradley KA, Williams EC. Documented brief intervention associated with reduced linkage to specialty addictions treatment in a national sample of VA patients with unhealthy alcohol use with and without alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2020;115(4):668-678. doi: 10.1111/add.14836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McCormick KA, Cochran NE, Back AL, Merrill JO, Williams EC, Bradley KA. How primary care providers talk to patients about alcohol: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):966-972. doi: 10.1007/BF02743146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen IQ, Chokron Garneau H, Seay-Morrison T, Mahoney MR, Filipowicz H, McGovern MP. What constitutes “behavioral health:” perceptions of substance-related problems and their treatment in primary care. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2020;15(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13722-020-00202-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Brien PCE, Fullerton C, Hughey L. Best practices and barriers to engaging people with substance use disorders in treatment. March 2019. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/migrated_legacy_files//187391/BestSUD.pdf

- 77.Huffstetler AN, Epling J, Krist AH. The need for electronic health records to support delivery of behavioral health preventive services. JAMA. 2022;328(8):707-708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.13391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chavez LJ, Williams EC, Lapham GT, Rubinsky AD, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Changes in patient-reported alcohol-related advice following Veterans Health Administration implementation of brief alcohol interventions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77(3):500-508. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(2):182-191. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hughes JP, Granston TS, Heagerty PJ. Current issues in the design and analysis of stepped wedge trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45(Pt A):55-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bobb JF, Qiu H, Matthews AG, McCormack J, Bradley KA. Addressing identification bias in the design and analysis of cluster-randomized pragmatic trials: a case study. Trials. 2020;21(1):289. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4148-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bobb JF, Cook AJ, Shortreed SM, Glass JE, Vollmer WM; NIH Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory Biostatistics and Study Design Core . Experimental designs and randomization schemes: designing to avoid identification bias. rethinking clinical trials: a living textbook of pragmatic clinical trials. 2019. Accessed January 19, 2023. https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/chapters/design/experimental-designs-randomization-schemes-top/designing-to-avoid-identification-bias/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Usual Care Condition

eAppendix 2. Detailed conceptual model of function and format of SPARC intervention and hypothesized effect with intermediate and co-primary outcomes

eAppendix 3. Alcohol Brief Intervention Sources and Natural Language Processing Identification of Brief Intervention

eAppendix 4. Definitions on Sensitivity Outcome Measures

eTable 1. Characteristics of patients with visits to sites randomized to different study waves within each stratum (Year 1 vs. Years 2-3 sites)

eTable 2. Prevention outcomes: parameter estimates under primary, secondary, explanatory, and sensitivity analysis measures

eTable 3. Treatment outcomes: parameter estimates under primary, secondary, explanatory, and sensitivity analysis measures

eTable 4. Parameter estimates for prevention and treatment outcomes under sensitivity analyses fitting generalized linear models

eReferences

Trial protocol

Data sharing statement