Abstract

Biogenesis of the large ribosomal (60S) subunit involves the assembly of three rRNAs and 46 proteins, a process requiring approximately 70 ribosome biogenesis factors (RBFs) that bind and release the pre-60S at specific steps along the assembly pathway. The methyltransferase Spb1 and the K-loop GTPase Nog2 are essential RBFs that engage the rRNA A-loop during sequential steps in 60S maturation. Spb1 methylates the A-loop nucleotide G2922 and a catalytically deficient mutant strain (spb1D52A) has a severe 60S biogenesis defect. However, the assembly function of this modification is currently unknown. Here, we present cryo-EM reconstructions that reveal that unmethylated G2922 leads to the premature activation of Nog2 GTPase activity and capture a Nog2-GDP-AlF4− transition state structure that implicates the direct involvement of unmodified G2922 in Nog2 GTPase activation. Genetic suppressors and in vivo imaging indicate that premature GTP hydrolysis prevents the efficient binding of Nog2 to early nucleoplasmic 60S intermediates. We propose that G2922 methylation levels regulate Nog2 recruitment to the pre-60S near the nucleolar/nucleoplasmic phase boundary, forming a kinetic checkpoint to regulate 60S production. Our approach and findings provide a template to study the GTPase cycles and regulatory factor interactions of the other K-loop GTPases involved in ribosome assembly.

Subject terms: Cryoelectron microscopy, Enzyme mechanisms, GTP-binding protein regulators, Ribosome, RNA modification

Regulation of 60S biogenesis remains poorly understood. Using cryo-EM, the authors show that failure of Spb1 to methylate the A-loop nucleotide G2922 prematurely activates the GTPase Nog2, suggesting that Spb1 and Nog2 form a kinetic checkpoint during ribosome maturation.

Introduction

Ribosomal RNA maturation includes the extensive post-transcriptional modification of nucleotides that cluster in functionally important regions of the ribosome1,2. In S.cerevisiae, snoRNPs methylate 54 nucleotides at the 2´-OH position to create 2´-O-methyl-riboses and isomerize 47 uridine bases to form pseudouridines, while dedicated enzymes catalyze the remaining 15 alterations3. Although their individual roles are not well defined, these nucleotide modifications collectively expand the rRNA chemical repertoire to modulate the assembly, stability and function of ribosomes1, 4–6. Among these rRNA-directed catalytic activities, a subset are carried out during late steps of ribosome maturation rather than co-transcriptionally when rRNA access is most unencumbered. These modifications in particular have been proposed to affect assembly events rather than the stability or function of mature ribosomes7–10.

One such late modification is the 2´-OH methylation of G2922 (mG2922) within the A-site loop of rRNA helix 92 (H92) by the S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase Spb1 (Fig. 1a, b)7,8,11. Notably, mG2922 is the only eukaryotic ribose methylation carried out in a snRNP-independent manner by a dedicated enzyme. Spb1 is an essential structural component of nucleolar pre-60S intermediates11,12 and strains carrying a mutation (spb1D52A) that abolishes G2922 methylation activity display a severe growth defect and impaired 60S biogenesis7,8. After Spb1 release and L1 stalk rearrangement13, the K+-dependent GTPase Nog2 engages the A-loop during nucleoplasmic 60S maturation steps (Fig. 1c, d)14–17. Nog2 is an essential hub enzyme that acts as a key quality control element during the nucleoplasmic maturation of 60S, anchoring both the pre- and post-rotation states of the 5S rRNP (Nog2pre and Nog2post) via extensive rRNA and RBF interactions13,14. GTP hydrolysis by Nog2 is required for its dissociation and for the subsequent recruitment of the export factor Nmd3, which enables the nuclear export of pre-60S particles18–21.

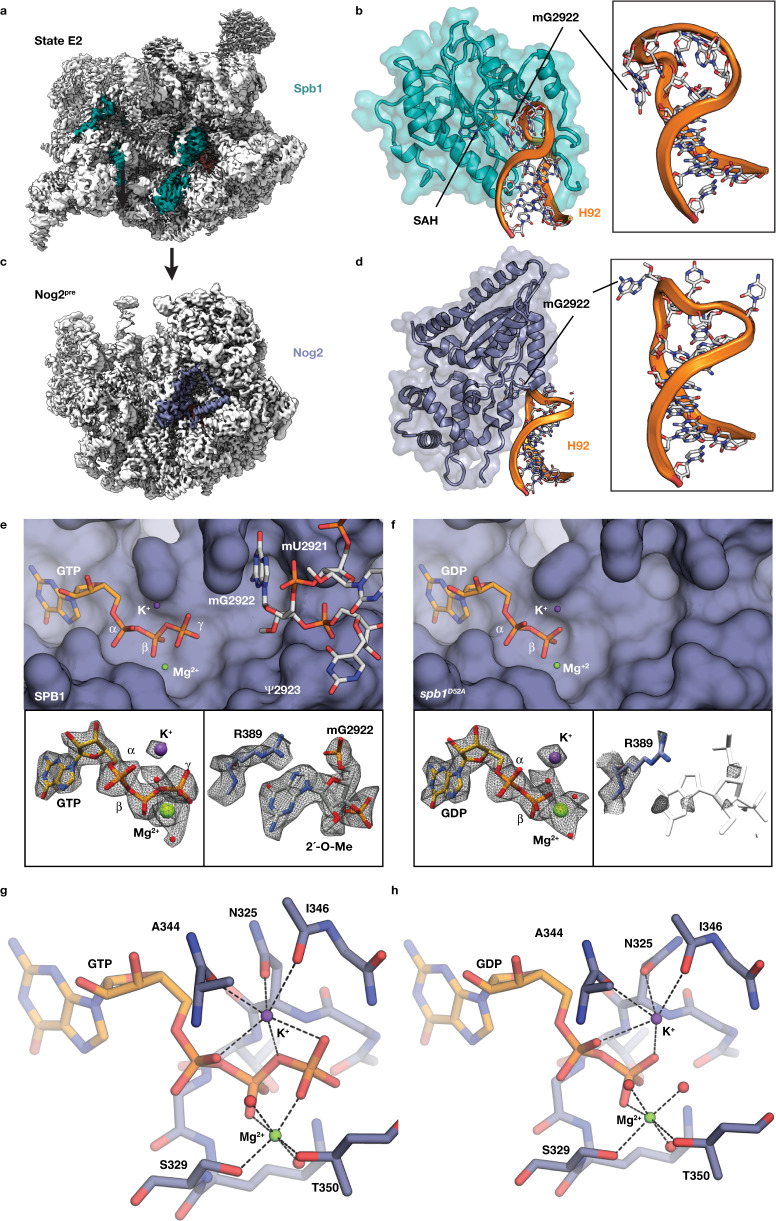

Fig. 1. Disruption of Spb1 methylation of G2922 results in premature Nog2 GTP hydrolysis.

a Position of the methyltransferase Spb1 in the State E2 (pdb-7NAC) cryo-EM reconstruction11. b detail of the interaction between the methyltransferase domain of Spb1 (teal cartoon) and helix 92 (orange). mG2922 is located within the A-loop at the apex of H92 (boxed inset). c Location of the Nog2 GTPase in the cryo-EM reconstruction of the Nog2pre state. d Detail of the interaction between the GTPase domain of Nog2 and H92. mG2922 is intercalated near the active site of Nog2, protruding away from the A-loop (boxed inset). e Top – Surface rendition of the Nog2 GTPase active site from the SPB1 strain (K-loop residues are omitted for clarity), showing stick models of GTP and the A-loop with intercalated nucleotide mG2922 as well as the position of catalytic ions. Bottom – Experimental maps from Nog2pre (SPB1) carved around GTP (left) and mG2922 (right), showing clear density for the γ-phosphate and the 2´-O-methyl group. f Top – Surface rendition of the Nog2 GTPase active site derived from the spb1D52A strain (K-loop residues are omitted for clarity), showing stick models of GDP and catalytic ions. Bottom – Map density carved around GDP (left) and the area normally occupied by the A-loop (right), showing that GTP hydrolysis has taken place and that the A-loop (reference position shown as a transparent outline) is no longer intercalated into the active site. g Mg2+ and K+ coordination network in the GTP-bound bound active site (SPB1 strain). Nog2 residues involved in metal coordination are shown as sticks and labeled. h Mg2+ and K+ coordination network in the GDP-bound bound active site (spb1D52A strain). Nog2 residues involved in metal coordination are shown as sticks and labeled.

Here, we present cryo-EM reconstructions showing that failure to methylate G2922 causes the premature activation of Nog2 GTPase activity. A structure of the Nog2-GDP-AlF4− transition state is consistent with a direct role for G2922 in the activation of Nog2. Genetic suppressors and in vivo imaging of the ribosomal protein uL23-GFP indicate that premature GTP hydrolysis prevents the efficient binding of Nog2 to early nucleoplasmic 60S intermediates, resulting in a 60S biogenesis defect. Based on these results, we propose a model in which G2922 methylation levels regulate Nog2 recruitment to the pre-60S near the nucleolar/nucleoplasmic phase boundary, forming a kinetic checkpoint to regulate 60S production.

Results

G2922 methylation modulates Nog2 GTP hydrolysis

Because of the proximity of mG2922 to the active site of Nog2 (Fig. 1d), we investigated the effect of G2922 methylation status on Nog2 engagement of pre-60S intermediates by obtaining high-resolution cryo-EM reconstructions of Nog2pre intermediates from SPB1 (2.3 Å) and spb1D52A (2.4 Å) strains using dual affinity tags on Nog2 and the biogenesis factor Tif6 (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). While there are no major differences in RBF composition compared to earlier structures, the ~0.7 Å improvement in the overall resolution of our maps compared to previous reconstructions of Nog2pre enabled us to build an improved atomic model that includes all observable rRNA nucleotide modifications, ordered Mg2+ ions and their coordinated waters as well as three ordered Bis-Tris-Propane molecules (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Our model corrects a number of register shifts and mis-paired rRNA bases as well as improving the completeness of individual RBF and RP models. In the active site of Nog2 reconstructed from the SPB1 strain, we were able to precisely model GTP, Mg2+ and K+ ions, correcting the GTP orientation from earlier Nog2pre models (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 6a–d)14. There is clear density for the methyl group of mG2922 intercalated in near proximity (~7.2 Å) to the γ-phosphate of the GTP (Fig. 1e). In Nog2pre intermediates purified from the spb1D52A strain, Nog2 occupies an identical position and maintains all of its RBF, RP and rRNA interactions, but the Nog2 active site is strikingly different (Fig. 1f): There is no density corresponding to the GTP γ-phosphate, indicating that GTP hydrolysis has taken place and that GDP occupies the Nog2 active site. Additionally, unmethylated G2922 is no longer intercalated near the Nog2 active site and the A-loop is only weakly ordered (Fig. 1f). The high resolution of our maps allowed us to infer the coordination network in the active sites of the GDP and GTP-bound states (Fig. 1g, h) and to define the ~1 Å shift in the orientation of the K-loop that occurs after GTP hydrolysis (Supplementary Fig. 6e). These structures indicate that the methyl group of mG2922 acts as an inhibitor of Nog2 GTP hydrolysis in the SPB1 wild-type strain. This inhibition could be either direct, if the absence of the methyl group allows G2922 to directly trigger hydrolysis, or indirect, if the intercalated mG2922 nucleotide blocks active site access by a different cis or trans-activating element.

G2922 is positioned to directly activate Nog2

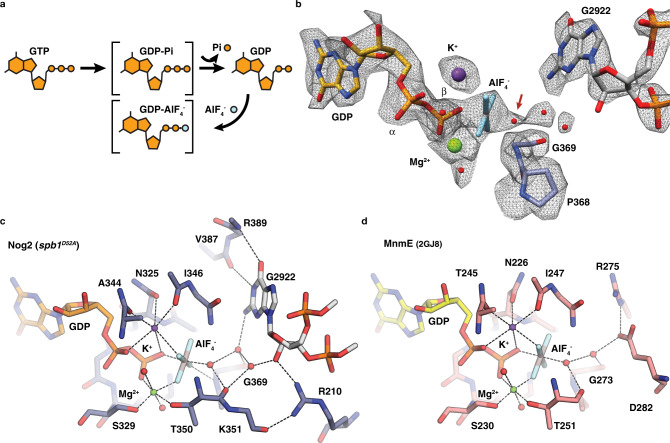

To address this question, we set out to capture the transition state of Nog2 GTPase activation by adding AlF4− to Nog2pre intermediates purified from the spb1D52A strain. Because the disordered A-loop remains in the vicinity of the active site after premature GTP hydrolysis, we hypothesized that addition of AlF4− could recapitulate a GTP hydrolysis transition state in these particles (Fig. 2a). A 2.4 Å cryo-EM reconstruction of this sample (Supplementary Figs. 3, 7) shows additional planar density consistent with AlF4− in the active site of Nog2 as well as the reappearance of density for G2922 and the rest of the A-loop near the Nog2 active site (Fig. 2b). As expected, the 2´-OH of G2922 is now unmethylated and helps co-ordinates a triad of water molecules linking G2922 and AlF4− (Fig. 2b, c) The water closest to the AlF4− moiety is at a distance of ~2.0 Å, consistent with the predicted position of the attacking nucleophilic water. This catalytic water is coordinated by the backbone carboxyl group of residue T350 as well as a bridging water that forms a hydrogen bond with the C2 amino group of the G2922 base and the backbone carbonyl of G369 within sensor II. The third water is H-bonded to the 2´OH of the G2922 ribose, assuming a position similar to that occupied by the methyl group of mG2922 in the WT SPB1 structure (Figs. 1e, 2c, Supplementary Movie 1). The Nog2 transition state shows a remarkable structural similarity to the high-resolution crystal structure of the bacterial K-loop GTPase MnmE22, with near identical positioning of GDP, AlF4− and the catalytic water network (Fig. 2c, d). We therefore propose that unmethylated G2922 acts as a trans-activating factor, organizing and activating a water network to trigger the nucleophilic attack on the GTP γ-phosphate. We believe this represents the first evidence of direct activation of a GTPase by an RNA nucleotide.

Fig. 2. G2922 is directly involved in Nog2 GTPase activation.

a Schematic of the transition state trapping strategy. AlF4- was added back to Nog2pre intermediates purified from the spb1D52A strain to mimic the transition state of GTP hydrolysis. b Map density in the active site of Nog2 after AlF4- addition, showing extra density consistent with the presence of tetragonal AlF4- and unmethylated G2922. c Active site coordination in the reconstituted transition state structure showing the organized water triad. Nog2 residues participating in the coordination network are shown as sticks. d The active site of the archetypal K-loop GTPase MnmE22, solved at 1.7 Å resolution in the presence of GDP-AlF4-, showing a near-identical coordination structure to that observed in the Nog2 transition state. The coordination of the attacking water, which is carried out by protein side chains in MnmE, is also highly similar. MnmE residues participating in the coordination network are shown as sticks.

Effect of early GTP hydrolysis on Nog2 pre-60S intermediates

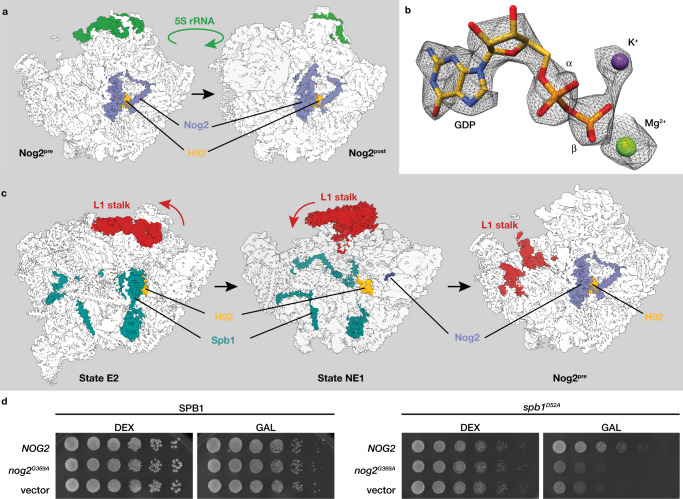

The overall structure of the Nog2pre intermediate is not affected by early Nog2 GTP hydrolysis, indicating the γ-phosphate is not required to maintain Nog2 binding. Further, we were also able to reconstruct the Nog2post intermediate state, both with and without the Rix1 complex13, from a subclass of particles purified from the spb1D52A strain (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Figs. 3, 4). Refinement of the Rix1-containing subset to 2.9 Å resolution shows that GDP-bound Nog2 remains associated with the 60S during 5S rotation and Rix1 complex binding, as the Nog2 active site in this reconstruction also contains GDP (Fig. 3b) and lacks clear density for the A-loop. Just like Nog2pre, Nog2post is not destabilized by the presence of Nog2-GDP, indicating that 5S rotation, Rix1-complex binding and Rea1 recruitment can proceed normally in the context of Nog2-GDP. Because the presence of Nog2-GDP did not cause any structural defects or instabilities in late nucleoplasmic intermediates, we instead hypothesized that the 60S biogenesis defect of the spb1D52A strain arises during the nucleolar/nucleoplasmic transition of pre-60S particles. This transition is initiated by the removal of a set of RBFs by the AAA + ATPase Rea1, triggering a rearrangement of the L1 stalk that allows it to dock onto the pre-60S core11,13 (Fig. 3c). These conformational changes expose the Nog2 docking site and permit its peripheral tail interactions. The presence of weak density for the Nog1-interaction loop of Nog2 in the NE1 structure11 suggests that Nog2 is initially loosely tethered to the pre-60S until the GTPase domain can dock. X-ray structures of isolated RbgA23,24, the bacterial homolog of Nog2 that engages an analogous position in pre-50S bacterial ribosomes, reveal that the K-loop of these enzymes does not adopt an ion-coordinating, mature conformation before pre-ribosome binding (Supplementary Fig. 8a). In the Nog2pre structure, the K-loop is stabilized by a conserved interaction with H64 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). H64 and H92 therefore promote the initial binding of Nog2 and combine to organize its active site. We hypothesize that premature activation of Nog2 disrupts this process. Stable Nog2pre intermediates can nevertheless still form if secondary binding interactions involving the Nog2 N-terminal tail can form to compensate for the loss of the A-loop interaction by Nog2-GDP. Reasoning that the reduced formation of Nog2pre particles during that nucleolar/nucleoplasmic transition could be overcome by increasing the concentration of Nog2 in vivo, we overexpressed NOG2 in the spb1D52A strain background, partially rescuing the growth defect (Fig. 3d). GTP hydrolysis is still required for growth rescue, since overexpression of nog2G369A, which binds but cannot hydrolyze GTP19, fails to rescue spb1D52A growth (Fig. 3d). This rescue was also specific to NOG2, since overexpression of SPB1-MTDNOLS or NMD3 failed to rescue growth (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). Unlike previous studies19, overexpression of nog2G369A in the SPB1 strain is not dominant negative (Fig. 3d), likely due to differences in strain backgrounds and overexpression systems.

Fig. 3. Premature GTP hydrolysis does not affect late nucleoplasmic 60S maturation but prevents the efficient formation of early nucleoplasmic intermediates.

a Low-pass-filtered maps (4.5 Å) of Nog2pre and Nog2post, purified from the spb1D52A strain highlighting the position of Nog2 (blue) and 5S rRNA (green) in its pre- and post-rotation states. b Map density in the Nog2 active site from Nog2post particles purified from the spb1D52A strain, showing clear occupancy by GDP. c Low pass filtered maps (4.5 Å) of pre-60S structures showing the transition between Spb1 and Nog2-containing intermediates near the nucleolar/nucleoplasmic boundary. The transition is precipitated by the catalytic activity of the ATPase Rea1 and is marked by the movement and docking of the L1 stalk (shown in red) and the formation of an organized 5S rRNP. In the NE1 state (pdb-7U0H), the C-terminal portion of Spb1 (teal) is still bound, blocking L1 rearrangement. Initial engagement of Nog2 also occurs at this juncture, as density for the Nog2 helix (blue) near the RBF Nog1 is also observed. d Overexpression of NOG2 partially rescues the slow growth phenotype of the spb1D52A strain. Plasmids containing Gal-inducible NOG2, nog2G369A or empty vector were transformed into SPB1 or spb1D52A strains and plated on selective synthetic media containing glucose (DEX) or galactose (GAL). Overexpression of NOG2, but not the catalytic mutant nog2G369A partially rescued the growth defect of spb1D52A cells.

Intragenic suppressors bypass the growth defect of spb1D52A

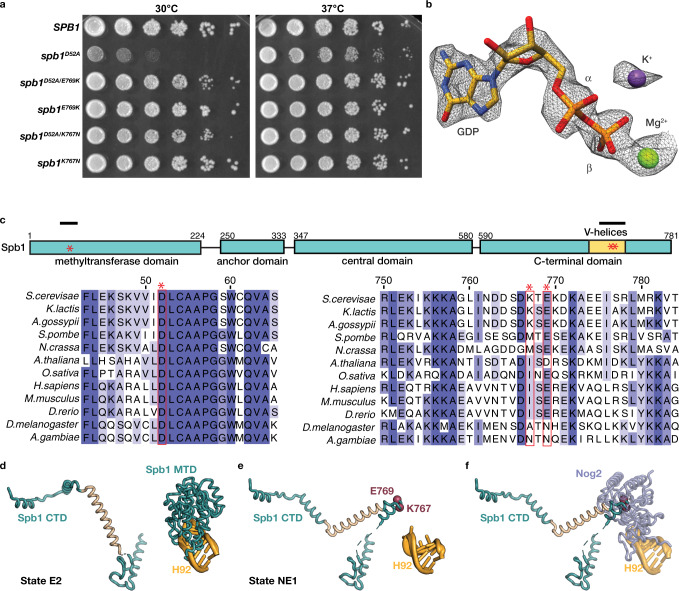

Additional evidence for this model comes from two spontaneous intragenic suppressors of spb1D52A (spb1K767N and spb1E769K), isolated during our genetic studies. Both mutations lead to a near-complete rescue of the growth defect of spb1D52A cells (Fig. 4a). To ensure that the mutations do not simply rescue the catalytic activity of Spb1, we obtained a cryo-EM reconstruction of Nog2pre purified from the spb1D52A/E769K double-mutant strain to 2.4 Å resolution (Supplementary Figs. 2, 7). Although these cells grow nearly as well as SPB1 wild-type cells, Nog2 is GDP-bound (Fig. 4b), showing that the suppressor mutations rescue the growth defect of spb1D52A despite the premature activation of Nog2 GTP hydrolysis. The suppressor mutations map to the structural, C-terminal portion of Spb1 (Fig. 4c) and insights into how these mutations affect the binding kinetics of Nog2 can be obtained from our recent structure of the NE1 pre-60S intermediate that captures the Spb1-Nog2 transition intermediate state (Fig. 3c)11. We were able to dock a structural model for the helical structure containing the suppressors using low-pass filtered maps and information from Alphafold25 models for this segment of Spb1 (Fig. 4d, e and Supplementary Fig. 8d, e). Both suppressors map to the turn at the apex of two V-shaped helices that extend into the region surrounding the disengaged H92 helix of state NE1)11. Modeling of the Nog2 GTPase domain onto this structure shows that it sterically clashes with the helical structure containing the suppressors (Fig. 4f). Thus, binding of the Nog2 GTPase domain cannot occur until the Spb1 helical element vacates the region around H92. We hypothesize that the suppressor mutants destabilize the helical structure in the C-terminal portion of Spb1, vacating the region around h92 to allow early, unfettered A-loop access, improving the overall binding kinetics of the Nog2 GTPase domain. The suppressors may facilitate the formation of secondary Nog2 binding interactions by modulating the kinetics of the L1 stalk docking. A kinetic basis for the defect observed in the spb1D52A strain is also suggested by the fact that the growth defect is partially rescued at 37 °C (Fig. 4a)7.

Fig. 4. Suppressor mutations in the C-terminal domain of Spb1 restore growth of spb1D52A in the absence of G2922 methylation.

a Spontaneous intragenic suppressors of spb1D52A rescue the slow growth phenotype of spb1D52A cells at 30 °C but do not influence cell growth on their own. As previously reported, growth of spb1D52A is restored at 37 °C. b Map density in the Nog2 active site from Nog2pre particles purified from the spb1D52A/E769K strain, showing clear occupancy by GDP and indicating that normal 60S nucleoplasmic maturation occurs in the presence of Nog2-GDP. c Domain schematic (top) of Spb1 showing the major segments of the protein as well as the position of D52 and of the suppressor mutations (red stars). The position of the V-helices is colored in yellow and the segments shown as sequence alignments are highlighted by black bars. (Bottom) Sequence alignments of the regions flanking the suppressor mutations are colored by the level of conservation per residue. d Cartoon depiction of the Spb1-CTD in the E2 and e NE1 states, showing the structural rearrangement of the central helical element (cream) and the release of the Spb1-MTD from H92. The position of the suppressor mutants at the apex of the v-shaped helices is shown as red spheres. f The helical element extends into the vicinity of H92, sterically blocking the Nog2 GTPase binding site.

Nucleolar/nuclear accumulation of pre-60S in spb1D52A cells

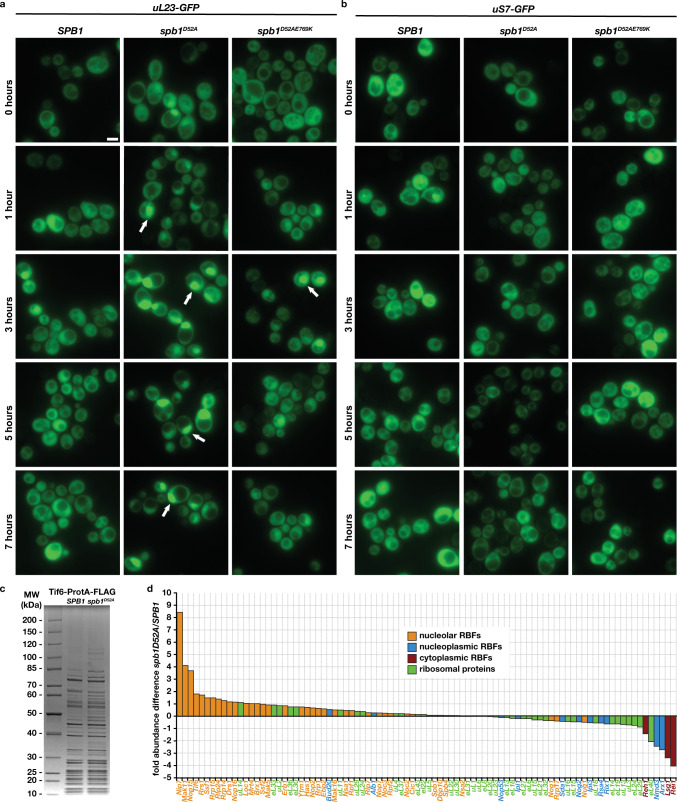

Both the suppressor mutants and the temperature-dependence of the spb1D52A phenotype suggest that modulation of Nog2 binding affects pre-60S assembly kinetics. Therefore, we visualized ribosome biogenesis in vivo by expressing GFP-tagged ribosomal proteins to monitor the assembly of large (uL23-GFP) or small (uS7-GFP) ribosomal subunits26–28. Saturated overnight cultures of SPB1, spb1D52A or spb1D52A/E769K all show an even cytoplasmic distribution of ribosomal subunits (Fig. 5a, b), but upon resumption of ribosome biogenesis after dilution into fresh media, nuclear accumulation of pre-60S intermediates, but not pre-40S, is observed in ~2/3 of cells of the spb1D52A strain (Fig. 5a, b). Some accumulation (~15% of cells) is also observed in the spb1D52A/E769K strain, especially at the 1 and 3 hour post-dilution timepoints, consistent with our hypothesis that the reduced binding of prematurely activated Nog2 represents a kinetic defect in the spb1D52A strain that can be partially overcome in the suppressor background. To confirm that the GFP signal reflects the accumulation of pre-60S particles and not free uL23-GFP, we carried out semi-quantitative mass spectrometry analysis of Tif6-containing pre-60S intermediates purified from either SPB1 and spb1D52A strains (Fig. 5c, Source data). Tif6 binds the pre-60S in the nucleoplasm and remains bound until final maturation in the cytoplasm, allowing for global changes in pre-60S distribution to be monitored10,20. A comparison of normalized abundances of RBFs and RPs shows an accumulation of RBFs that first engage the pre-60S in the nucleolus and a reduction of RBFs that engage the pre-60S during late nucleoplasmic and cytoplasmic maturation (Fig. 5d). Our structural, genetic, and localization data are in agreement with a recently published study on the function of G2922 methylation during 60S assembly29.

Fig. 5. Nuclear accumulation of pre-60S intermediates.

Time course of the in vivo distribution of GFP-tagged large (a) and small (b) ribosomal proteins in SPB1, spb1D52A, and spb1D52A/E769K cells after dilution of a saturated culture into fresh media (at t = 0 hours). White arrows indicate representative cells with nuclear accumulation of GFP signal. Images are pseudo-colored and scale bars represent 5 µm. c Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of tandem-purified Tif6-containing pre-60S intermediates from SPB1 and spb1D52A cells. Identical samples were analyzed by semi-quantitative mass spectrometry. d Visualization of semi-quantitative mass-spectrometry data sorted by differences in abundance between spb1D52A and SPB1 strains using representative RBFs and RPs between the two samples. RBFs are colored according to the subcellular compartment where they first bind pre-60S intermediates, showing a clear trend of nucleolar RBFs enrichment and late nucleoplasmic and cytoplasmic RBFs reduction. RP abundances are shown in green.

Discussion

Activation of Nog2 GTPase activity promotes its release from the pre-60S and allows the efficient recruitment of the export factor Nmd3. Our finding that the spb1D52A suppressor mutations sustain near wild-type growth even though Nog2 is GDP-bound throughout the nucleoplasmic maturation of the large subunit shows that although hydrolysis is necessary for Nog2 release, these events can be uncoupled without affecting the timing of Nog2 release and Nmd3 binding. This suggests that at a specific point in late nucleoplasmic maturation, after Rix1-Rea1 mediated removal of Rsa4, Nog2 binding to the pre-60S depends on the presence of the GTP γ-phosphate. How the GTPase activity of Nog2 is activated during normal maturation remains undefined, but potential mechanisms include a conformational change at the Nog2/H92 interface that pivots mG2922 in a way that cancels the inhibitory effect of the methyl group without affecting the ability of the C2-amine of mG2922 to coordinate the catalytic water network. Alternatively, Rsa4 removal could trigger the release of H92, allowing catalytic pocket access to a different Nog2 trans-activating element.

The direct link between Spb1 methylation and Nog2 GTPase activation raises the question about possible biological functions of premature Nog2 activation and the circumstances under which it is triggered in cells. One intriguing possibility is that Spb1 acts as a sensor to reduce the rate of 60S biogenesis in response to limiting intracellular concentrations of SAM. The concept of methyltransferases acting as SAM-sensors is well established in numerous regulatory pathways30,31. This model explains why G2922 methylation is carried out by a specialized enzyme rather than a snoRNP. Intriguingly, the E.coli homolog of Spb1, RlmE, is the only bacterial rRNA-directed methyltransferase that displays reduced catalytic activity in vivo when intracellular SAM levels are reduced32. We propose that under conditions of limiting SAM, Spb1 is outcompeted for the reduced intracellular SAM pool by other cellular methyltransferases, notably Nop1, the highly abundant catalytic component of the box C/D snoRNP complex. Failure to bind SAM does not affect the essential structural functions of Spb1 in nucleolar 60S maturation, but the subsequent intercalation of unmodified G2922 in the active site of Nog2 triggers premature GTP hydrolysis, resulting in the kinetic trapping of pre-60S intermediates at the nucleolar/nucleoplasmic boundary. Such a mechanism would allow an immediate and proportional reduction of 60S biogenesis in response to reduced cellular levels of SAM.

Methods

Yeast strains

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2, plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Genomic knockout strains in yeast were performed using standard PCR-mediated gene disruptions33.

Microscopy

For localization of uL18-GFP and uS5-GFP, strains were grown overnight in synthetic complete -uracil (SC-URA) medium with 2% Raffinose, and diluted 10x in SC-URA + 2% Raffinose and 1% Galactose. At each time point, cells were mounted in 1% low melt agarose and imaged immediately. Fluorescence micrographs were recorded on an inverted Nikon EclipseTi microscope fitted with a 100X Plan Apo objective and a Andor Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera. Images were processed after acquisition by contracting signal ranges and pseudo-coloring. For localization of Spb1-MTD variants, grown overnight in synthetic complete -uracil (SC-URA) medium with 2% Raffinose, and diluted to OD600 of 0.1 in SC-URA + 2% Raffinose and 1% Galactose to an OD of 0.5, mounted in 1% low melt agarose and imaged immediately. Images were taken on a Nikon Ti2-E inverted microscope equipped with a Yokogawa CSU-X1 spinning disk and a 100x NA = 1.49 oil objective. Samples were illuminated with a 488 nm solid state laser light source and images collected on an ORCA-FLASH 4.0 sCMOS camera. A z-series of confocal images was acquired for two fields of view in a single biological replicate. Image processing was performed using ImageJ.

Isolation and identification of a spb1D52A suppressors

Fast growing colonies that spontaneously arose from the spb1D52A strain were isolated and back-crossed to spb1D52A to confirm the presence of a single mutation. Sequencing of candidate genes revealed the single point mutations (spb1K767N and spb1E769K).

Overexpression and purification of Nog2 containing pre-ribosomes

For yeast overexpression, full length wild-type NOG2 was cloned into a modified pRS406 plasmid that introduced a C-terminal MYC–TEV–2xStrep tag under the control of a β-estradiol inducible system34. Tif6 was tagged at the genomic locus with a C-terminal 3xFLAG–3C–2xProteinA. Starter cultures for each strain were grown overnight in YPD to saturation. The following morning 12 L of YPD were inoculated from the starters to an OD600 of 0.1 and grown at 30 °C to an OD600 of 0.8. Overexpression was induced for 1 hour by the addition of β -estradiol to a final concentration of 2 µm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 20 min at 4000 g, the pellets were washed in Ribo-buffer A (50 mM Bis-Tris-Propane HCl pH 8.0, 125 mM NaCl, 25 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP and 0.1% (w/v) NP-40) and centrifuged again for 10 min at 4000 g. Cell pellets were harvested and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryogenic lysis was done using a grinding ball mill (Fritsch Pulverisette 6). For purification of pre-ribosomes, 30 g of lysate are warmed to 4 °C before addition of Ribo-buffer A supplemented with E64, pepstatin, PMSF and RNAse-free DNase I. Lysate was cleared by centrifuging at 100,000 g for 30 min and loaded onto IgG Sepharose resin (Cytiva). Samples were washed with 10 column volumes of Ribo-buffer A followed by 10 column volumes of Ribo-buffer B (50 mM Bis-Tris-Propane HCl pH 8.0, 125 mM NaCl, 25 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM TCEP and 0.01% (w/v) NP-40). Protein-A tags were cleaved on-column using 3 C protease and eluates were applied to a Strep-Tactin column (Cytiva), washed with 5 column volumes of Ribo-buffer B and eluted using Ribo-buffer B supplemented with 10 mM desthiobiotin. Eluted pre-ribosomes were concentrated on Amicon Ultra 0.5 ml spin columns with a 100 kDa cutoff (Merck Millipore). Starter strains carrying spb1D52A were grown for 36 h to reach saturation and 12 L cultures were grown to 12 – 16 hours to reach an OD600 of 0.8. A fraction of the Nog2 ∙ Tif6 intermediates obtained from the spb1D52A strain were incubated with 50 µM AlF4− for 30 minutes before preparation of cryo-EM grids.

Cryo-EM grid preparation and Data Collection

Cryo-EM grids were prepared using a Mark IV Vitrobot (FEI) set at 4 °C and 100% humidity by applying 3 µL of Nog2 ∙ Tif6 samples at a concentration of 8 A260ml−1 (260 nM) to the carbon side of glow-discharged continuous carbon coated Quantifoil R2/1 300-mesh grids. After sample application a wait time of 10 s was used, followed by grid blotting with a blot force of 13 and blot time of 4.5 s. After blotting, grids were quickly plunged and frozen in liquid ethane. Nog2 ∙ Tif6 from the spb1D52A strain with and without AlF4− were prepared at a concentration of 3 A260ml−1 (100 nM). The Nog2 ∙ Tif6 sample from the suppressor strain spb1D52A/ E769K was prepared at a concentration of 8 A260ml−1 (260 nM). Micrographs were acquired on a Titan Krios (FEI) operated at 300 kV equipped with a Gatan K3 direct electron detector using a slit width of 30 eV on a GIF-Quantum energy filter. Automated data collection was performed using SerialEM35 with a defocus range of −0.9 to −2.2 µm and a pixel size of 1.08 Å. Each micrograph was dose fractionated into 40 frames of 0.05 s each under a dose rate of 26.2 e−/pixel/s with a total exposure time of 2 seconds and a dosage of approximately 56.4 e−/pixel. 5580 movies were collected for the Nog2 ∙ Tif6 sample from the SPB1 strain, 5434 movies for the Nog2 ∙ Tif6 sample from the spb1D52A strain and 4349 movies were collected for Nog2 ∙ Tif6 sample from the spb1D52A,E769K strain. The Nog2 ∙ Tif6 ∙ AlF4− sample from the spb1D52A strain was collected at the PNCC using a Titan Krios operated at 300 kV with a pixel size of 1.0688 Å. 7614 movies were collected for this dataset.

Cryo-EM image processing

Motion correction was performed using MotionCorr236, and CTF parameters were estimated using GCTF37. Movie selection was based on the quality of Thon rings and on the absence of artifacts that arise from poor ice, for the Nog2∙Tif6 (SPB1) dataset 4910 movies were retained out of 5580 that were collected, for Nog2∙Tif6 (spb1D52A) dataset 5327 movies were retained from an original 5434, for the Nog2∙Tif6∙AlF4- (spb1D52A) dataset 7590 movies were selected from 7614, and for the Nog2∙Tif6 (spb1D52A, E769K) dataset 3774 movies were used from the original 4349. All subsequent image processing was performed using RELION38.

Nog2∙Tif6 (SPB1) dataset

About 300 particles were picked from 3 micrographs to generate initial 2D classes to use as templates for automated particle picking from the 4910 micrographs. 1,680,783 particles were extracted, binned 4 times and used for 2D classification, from these 1,639,317 particles were selected for 3D classification. Four identical Nog2pre classes were combined and re-extracted at the original pixel size of 1.08 Å, resulting in the total of 1,358,921 particles. 3D refinement was performed with an imposed symmetry of C1 and resulted in a reconstruction with a resolution of 2.84 Å. A mask surrounding H68 was used to subtract core density followed by a local 3D classification without re-alignment in order to select particles with strong density for H68. From this, 1,159,206 particles were selected for the final reconstruction. After another cycle of 3D refinement and postprocessing the overall resolution improved to 2.34 Å. Using a similar procedure, another local classification was performed from the initially picked 3D classes that focused on the 5S rRNP and resulting in a 2.63 Å resolution map, notably improving the map quality for that region. For model building, the local 5S rRNP map was aligned and resampled onto the overall map grid using the VOP command in UCSF Chimera, the 5S was built into this aligned local 5S rRNP map. The final resolution in each case was estimated by applying a soft mask over the maps and was calculated using the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) = 0.14339. Local resolution maps were generated using the ResMap40 wrapper within Relion 3.1.

Nog2∙Tif6 (spb1D52A) dataset

Initial 2D classes were obtained the same way as for Nog2∙Tif6 dataset. 925,065 particles were extracted after automated particle picking, binned 4 times and used for 2D classification. 905,023 particles were selected for subsequent 3D classification. Two Nog2pre classes were combined and re-extracted at the original pixel size of 1.08 Å, resulting in the total of 328,470 particles, the excluded pre-rotation class had much weaker density for various regions within the core and foot region. 3D refinement was performed with an imposed symmetry of C1 and resulted in an initial reconstruction with a resolution of 2.95 Å. After CTF refinement, another cycle of 3D refinement the overall resolution improved to 2.44 Å after postprocessing. From the initial 3D classification a single class of Nog2post that contained 102,436 particles was also used for further processing. A mask was made surrounding the Rix-complex to subtract core density, this was followed by local 3D classification without re-alignment to select Rix-complex-containing particles and resulted in a single class with 50,091 particles and a final resolution of 2.90 Å after 3D refinement and postprocessing. Only Nog2 was modeled in this map and the GTP was modified to GDP, the reference model that should be used for this map is PDB 6YLH13.

Nog2∙Tif6∙AlF4− (spb1D52A) dataset

Initial 2D classes were obtained the same way as for the Nog2∙Tif6 (SPB1) dataset. 790,530 particles were extracted after automated particle picking, binned 4 times and used for 2D classification, selecting 716,018 particles for subsequent 3D classification. Three classes corresponding to Nog2pre were combined and re-extracted at the original pixel size of 1.08 Å, resulting in the total of 417,994 particles. 3D refinement was performed with an imposed symmetry of C1 and resulted in an initial reconstruction with a resolution of 2.78 Å. CTF refinement followed by another cycle of 3D refinement and postprocessing improved the overall resolution to 2.38 Å.

Nog2∙Tif6 (spb1D52A, E769K) dataset

Initial data processing was performed as for the Nog2∙Tif6 (SPB1) dataset. 1,207,583 particles were selected from 2D classification, binned 4 times, and extracted for subsequent 3D classification. Five Nog2pre classes attained the theoretical resolution limit and looked identical (923,524 particles). However, to expedite data processing only one class containing 330,196 particles was selected for further processing. CTF refinement and 3D refinement followed by selection of particles with strong H68-containing density resulted in a total of 320,145 particles. After subsequent polishing, 3D refinement and postprocessing a final map with a resolution of 2.36 Å was obtained.

Cryo-EM model building and refinement

PDB 3JCT14 was used as a starting model for the Nog2pre (SPB1) map and the refined rebuilt model was used for building and refining into the other Nog2pre maps generated in this study. PDB 2GJA22 was used as to validate the placement of both the waters and GDP ∙ AlF4− in the Nog2 active site in the Nog2pre-AlF4− (spb1D52A) dataset. Nog2 from PDB 6YLH13 was used as a starting model for Nog2post (spb1D52A). All models were built in Coot41 and refined in PHENIX using phenix.real_space_refine42. Figures were generated with UCSF Chimera43, Chimera X44, and the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Version 2.0 Schödinger, LLC.).

Time course microscopy methods

Strains YJE001, YJE944 and YJE869 were transformed with pRS316-uL18-GFP or pRS316-uS5-GFP26,28. Strains were grown in SCD-URA at 30 °C or 37 °C to saturation and then diluted 1:10 into SCD-URA and grown at 30 °C. At each time point, cells were mounted in 1% low melt agarose and imaged immediately. Fluorescence micrographs were recorded on an inverted Nikon EclipseTi microscope fitted with a 100X Plan Apo objective and an Andor Zyla 5.5 sCMOS camera.

Purification of Tif6 containing pre-ribosomes

Starters of YJE608 (SPB1) and YJE735 (spb1D52A) harboring a genomic C-terminal 3xFLAG–3C–2xProteinA tag on Tif6 were grown overnight in YPD to saturation. The following morning 12 L of YPD were inoculated from the starters to an OD600 of 0.2 and grown at 30 °C to an OD600 of 1.2. Cells were harvested and lysed identically to samples used for cryo-EM, described above. Lysate was cleared in the same way and loaded onto an IgG Sepharose resin (Cytiva). Samples were washed with 10 column volumes of Ribo-buffer A followed by 10 column volumes of Ribo-buffer B. Protein-A tags were cleaved on-column using 3 C protease and eluates were added to 2.0 ml Eppendorf tubes with FLAG resin (Sigma) equilibrated in Ribo-buffer B and incubated on a rocker at 4 °C for 2 h. The slurry was transferred into MicroSpin G-25 Columns (GE Healthcare), washed with 2 ml of Ribo-buffer B, then mixed with 100 µL of Ribo-buffer B enriched with 0.5 mg/ml FLAG peptide and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. Samples were eluted by gravity flow and concentrated to an A260ml−1 of 3 (100 nM) using an Amicon Ultra 0.5 ml spin column with a 100 kDa cutoff (Merck Millipore).

Semi-quantitative mass-spectrometry analysis

3.3 µM of Tif6 containing pre-ribosomes were run on a 4–20% denaturing Gel (BioRad) at 160 V for 7 min and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Thermo Fisher). The portion of the gel with protein bands was excised and used for subsequent analysis. Semi-quantitative mass-spectrometry data was obtained by the UTSW Proteomics core, analyzed using Proteome Discoverer 2.4 and searched against the yeast protein database from UniProt. Only high-confidence spectra (FDR ≤ 1%) were considered and are listed in Source Data. Selection of RBFs for our plot was based on their presence in known intermediate structures or well-established presences in specific pre-60S intermediates.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Stoddard and Jose Martinez at the UTSW Cryo-Electron Microscopy Facility, funded in part by the CPRIT Core Facility Support Award RP170644, James Chen at the UTSW Structural Biology Lab and Matthew Parker for help with light microscopy. A portion of this research was supported by NIH grant U24GM129547 and performed at the PNCC at OHSU and accessed through EMSL (grid.436923.9), a DOE Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research, with the assistance of Theo Humphreys. We thank V. Panse for sharing plasmids pRS316-uL18-GFP and pRS316-uS5-GFP. The authors would also like to acknowledge the Quantitative Light Microscopy Core, a shared resource of the Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center, supported in part by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant, 1P30 CA142543-01 and the UTSW Proteomics Core. J.P.E. was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR150074), the Welch Foundation (I-1897), the UTSW Endowed Scholars Fund and the National Institutes of Health (GM135617-01).

Source data

Author contributions

K.S., V.E.C., C.S.W and J.P.E. conceived the project. K.S., V.E.C., and C.S.W. constructed strains. K.S. and C.S.W. conducted all growth and microscopy assays. V.E.C. and K.S. carried out sample preparations and collected cryo-EM data. V.E.C., K.S. and J.P.E. processed the cryo-EM data. J.P.E., K.S., V.E.C. and C.S.W. wrote the paper. J.P.E. supervised the work.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The cryo-EM density maps and models have been deposited in EMDB and PDB databases under accession codes: EMD-26651 /pdb-7UOO (Nog2pre from the SPB1 strain), EMD-26689 (Nog2pre 5S rRNP local map), EMD-26703/pdb-7UQZ (Nog2pre from spb1D52A strain), EMD-26799 /pdb-7UUI (Nog2post from spb1D52A strain), EMD-26686 /pdb-7UQB (Nog2pre with AlF4− from spb1D52A strain), EMD-26941 /pdb-7V08 (Nog2pre from spb1D52A/E769K strain). Strain and plasmid information, cryo-EM micrographs, 2D classes, FSC curves, ResMap plots, and data processing 3D-classification and particle sorting schemes generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.P.E. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Kamil Sekulski, Victor Emmanuel Cruz.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-36867-5.

References

- 1.Sloan KE, et al. Tuning the ribosome: The influence of rRNA modification on eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis and function. RNA Biol. 2017;14:1138–1152. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1259781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taoka M, et al. Landscape of the complete RNA chemical modifications in the human 80S ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:9289–9298. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang J, et al. Mapping of Complete Set of Ribose and Base Modifications of Yeast rRNA by RP-HPLC and Mung Bean Nuclease Assay. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0168873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helm M. Post-transcriptional nucleotide modification and alternative folding of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:721–733. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baxter-Roshek JL, Petrov AN, Dinman JD. Optimization of ribosome structure and function by rRNA base modification. PLoS One. 2007;2:e174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofler S, Carlomagno T. Structural and functional roles of 2’-O-ribose methylations and their enzymatic machinery across multiple classes of RNAs. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020;65:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lapeyre B, Purushothaman SK. Spb1p-directed formation of Gm2922 in the ribosome catalytic center occurs at a late processing stage. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:663–669. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnerot C, Pintard L, Lutfalla G. Functional redundancy of Spb1p and a snR52-dependent mechanism for the 2’-O-ribose methylation of a conserved rRNA position in yeast. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1309–1315. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Yang J, Watzinger P, Kotter P, Entian KD. Yeast Nop2 and Rcm1 methylate C2870 and C2278 of the 25S rRNA, respectively. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:9062–9076. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sailer C, et al. A comprehensive landscape of 60S ribosome biogenesis factors. Cell Rep. 2022;38:110353. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruz VE, et al. Sequence-directed RNA remodeling within a topologically complex RNP substrate. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2022;29:1228–1238. doi: 10.1038/s41594-022-00874-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kater L, et al. Visualizing the Assembly Pathway of Nucleolar Pre-60S Ribosomes. Cell. 2017;171:1599–1610 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kater L, et al. Construction of the Central Protuberance and L1 Stalk during 60S Subunit Biogenesis. Mol. Cell. 2020;79:615–628.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu S, et al. Diverse roles of assembly factors revealed by structures of late nuclear pre-60S ribosomes. Nature. 2016;534:133–137. doi: 10.1038/nature17942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kargas V, et al. Mechanism of completion of peptidyltransferase centre assembly in eukaryotes. Elife. 2019;8:e44904. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Y, Musalgaonkar S, Johnson AW, Taylor DW. Tightly-orchestrated rearrangements govern catalytic center assembly of the ribosome. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:958. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08880-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang X, et al. Structural snapshots of human pre-60S ribosomal particles before and after nuclear export. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3542. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17237-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saveanu C, et al. Nog2p, a putative GTPase associated with pre-60S subunits and required for late 60S maturation steps. EMBO J. 2001;20:6475–6484. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo Y, et al. Coupled GTPase and remodelling ATPase activities form a checkpoint for ribosome export. Nature. 2014;505:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klinge S, Woolford JL., Jr. Ribosome assembly coming into focus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:116–131. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kressler D, Hurt E, Bassler J. A Puzzle of Life: Crafting Ribosomal Subunits. Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:640–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scrima A, Wittinghofer A. Dimerisation-dependent GTPase reaction of MnmE: how potassium acts as GTPase-activating element. EMBO J. 2006;25:2940–2951. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim DJ, Jang JY, Yoon HJ, Suh SW. Crystal structure of YlqF, a circularly permuted GTPase: implications for its GTPase activation in 50 S ribosomal subunit assembly. Proteins. 2008;72:1363–1370. doi: 10.1002/prot.22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pausch P, et al. Structural basis for (p)ppGpp-mediated inhibition of the GTPase RbgA. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:19699–19709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jumper J, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021;596:583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurt E, et al. A novel in vivo assay reveals inhibition of ribosomal nuclear export in ran-cycle and nucleoporin mutants. J. Cell Biol. 1999;144:389–401. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stage-Zimmermann T, Schmidt U, Silver PA. Factors affecting nuclear export of the 60S ribosomal subunit in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:3777–3789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.11.3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altvater M, Schutz S, Chang Y, Panse VG. Dissecting ribosome assembly and transport in budding yeast. Methods Cell Biol. 2014;122:437–461. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417160-2.00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yelland, J. N. et al. A single 2′-O-methylation of ribosomal RNA gates assembly of a functional ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 91–98 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Pendleton KE, et al. The U6 snRNA m(6)A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell. 2017;169:824–835.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu X, et al. SAMTOR is an S-adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science. 2017;358:813–818. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ishiguro K, Arai T, Suzuki T. Depletion of S-adenosylmethionine impacts on ribosome biogenesis through hypomodification of a single rRNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:4226–4239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petracek ME, Longtine MS. PCR-based engineering of yeast genome. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:445–469. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)50978-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ottoz DS, Rudolf F, Stelling J. Inducible, tightly regulated and growth condition-independent transcription factor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e130. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang K. Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J. Struct. Biol. 2016;193:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheres SH, Chen S. Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:853–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The cryo-EM density maps and models have been deposited in EMDB and PDB databases under accession codes: EMD-26651 /pdb-7UOO (Nog2pre from the SPB1 strain), EMD-26689 (Nog2pre 5S rRNP local map), EMD-26703/pdb-7UQZ (Nog2pre from spb1D52A strain), EMD-26799 /pdb-7UUI (Nog2post from spb1D52A strain), EMD-26686 /pdb-7UQB (Nog2pre with AlF4− from spb1D52A strain), EMD-26941 /pdb-7V08 (Nog2pre from spb1D52A/E769K strain). Strain and plasmid information, cryo-EM micrographs, 2D classes, FSC curves, ResMap plots, and data processing 3D-classification and particle sorting schemes generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.P.E. Source data are provided with this paper.