Abstract

Background

Evidence-based programs (EBPs) are used across disciplines to integrate research into practice and improve outcomes at the individual and/or community level. Despite widespread development and implementation of EBPs, many programs are not sustained beyond the initial implementation period due to many factors, including workforce turnover. This scoping review summarizes research on the impact of workforce turnover on the sustainability of EBPs and recommendations for mitigating these impacts.

Methods

We searched 10 databases for articles that focused on an EBP and described an association between workforce turnover and the sustainment or sustainability of the program. We created a data abstraction tool to extract relevant information from each article and applied the data abstraction tool to all included articles to create the dataset. Data were mapped and analyzed using the program sustainability framework (PSF).

Results and Discussion

A total of 30 articles were included in this scoping review and mapped to the PSF. Twenty-nine articles described impacts of workforce turnover and 18 articles proposed recommendations to address the impacts. The most frequent impacts of workforce turnover included increased need for training, loss of organizational knowledge, lack of EBP fidelity, and financial stress. Recommendations to address the impact of workforce turnover included affordable and alternative training modalities, the use of champions or volunteers, increasing program alignment with organizational goals, and generating diverse funding portfolios.

Conclusion

The sustainment of EBPs is critical to ensure and maintain the short- and long-term benefits of the EBP for all participants and communities. Understanding the impacts of workforce turnover, a determinant of sustainability, can create awareness among EBP-implementing organizations and allow for proactive planning to increase the likelihood of program sustainability.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice, evidence-based program, implementation, sustainment, scoping review, workforce turnover, retention, determinant of sustainability

Evidence-based programs (EBPs) are used across disciplines to integrate research and expertise into practice, facilitating positive outcomes at the individual or community level. Prior research has revealed an estimated 17-year delay between EBP development and widespread implementation, a phenomenon called the “research-to-practice” gap (Bauer et al., 2015). The field of dissemination and implementation (D&I) science has grown in response, with a primary focus on effectively and efficiently translating research into real-world practice through EBPs (Eccles & Mittman, 2006). Alongside program adoption (uptake) and implementation (delivery), sustainability (program maintenance over time) has been acknowledged as a key goal for EBPs (Proctor et al., 2015; Scheirer & Dearing, 2011). Aside from the direct impact on program participants, discontinuing programs may also negatively impact funders, policymakers, delivery organizations, and the implementation community through a loss of investments, resources, or time (Shelton et al., 2018). This can lead to strained future relationships, negative perceptions, and reduced support for EBPs.

Sustainability definitions vary in the D&I field from understanding sustainability as an outcome (long-term implementation or institutionalization) to understanding sustainability as a process (allowing for dynamic adaptation in response to internal and external environmental factors while maintaining core program elements (Shelton et al., 2018). Several sustainability frameworks and assessment tools have been developed, including the program sustainability framework (PSF) and the dynamic sustainability framework (Chambers et al., 2013; Luke et al., 2014; Shelton et al., 2018). Researchers have also identified several determinants of sustainability, including funding, organizational resources, external policy environments, program adaptability, and leadership and workforce turnover (Proctor et al., 2015; Scheirer & Dearing, 2011; Stirman et al., 2012). However, few studies have explored the relationship between these determinants and EBP sustainability (Stirman et al., 2012).

Workforce turnover, defined as an employee voluntarily or involuntarily leaving an agency or program (Garner et al., 2012) is a critical determinant of EBP sustainability because EBPs cannot be implemented or sustained without adequate staffing. Workforce turnover has been measured through various organizational metrics including the number of employees leaving in a calendar year (Aarons et al., 2009; Chisholm et al., 2011; Garner et al., 2012). Previous research exploring workforce turnover and EBPs has either examined associations between turnover and program implementation (Aarons et al., 2009; Brabson et al., 2020; Woltmann et al., 2008), explored the predictors of turnover within EBP settings (Brabson et al., 2019; Quetsch et al., 2020), or focused within a single discipline, like mental health services or early education (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006; Brabson et al., 2020; Gill et al., 2017; Woltmann et al., 2008). Recent work has begun to incorporate sustainability into the exploration of workforce turnover impact on EBPs (McKay et al., 2018). However, there is still a lack of understanding of the impact of workforce turnover on EBP sustainability.

This scoping review summarizes the evidence regarding the impact of workforce turnover on the sustainability of EBPs and identifies recommendations proposed in the literature for mitigating this impact. Our results may benefit EBP use by shedding light on this key barrier to sustainability.

Methods

We decided to conduct a scoping review, as opposed to a systematic review or meta-analysis, because this is a relatively new, underdeveloped area of inquiry, and we surveyed a body of literature that included a wide range of study designs across multiple disciplines (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010; Tricco et al., 2018). The variability in study design makes it challenging to complete an assessment of study quality, which would be necessary in a systematic review or meta-analysis (Levac et al., 2010). This scoping review was conducted in consultation with an expert panel of researchers in the field and met the evidence-based PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) methodological and reporting guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018).

For the purposes of this project, we treat the terms “sustainability” and “sustainment” as synonymous and use the sustainability definition proposed by Scheirer and Dearing (2011): “the continued use of program components and activities for the continued achievement of desirable program and population outcomes.” This definition is increasingly used in the literature and using it here meets Shelton et al.’s (2018) recommendation for consistent use of sustainability definitions. As a review, this study was exempt from Institutional Review Board oversight.

Search strategy

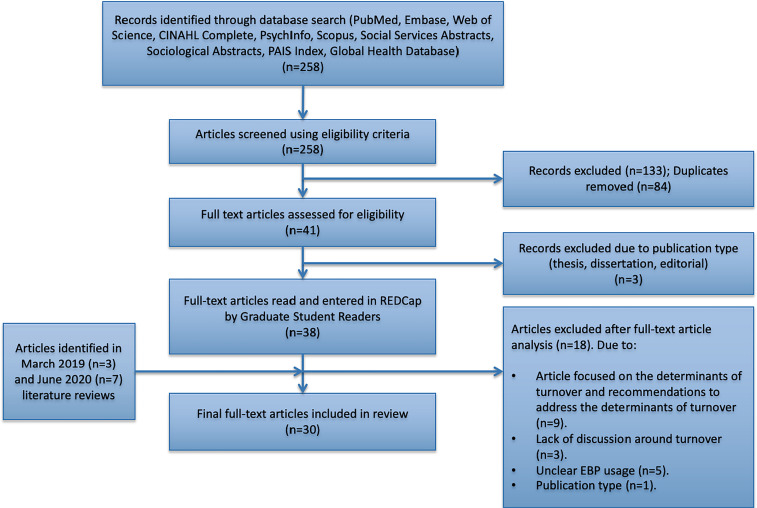

We searched 10 bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, CINAHL Complete, PsychINFO, Scopus, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, PAIS Index, and the Global Health Database) for articles with titles, abstracts, or keywords containing all of the following key terms: (a) “sustainability” or “sustainment”; (b) “retention” or “turnover”; and (c) “evidence based” or “evidence-based.” The initial search was conducted October 2017–February 2018. We performed identical searches in March 2019 and June 2020 due to an extended project timeline. A flow chart of the search strategy is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scoping review search strategy flow diagram.

Inclusion criteria

English-language studies were included if they: (a) had a title, abstract, or keyword(s) that mentioned the key terms detailed above; (b) described an empirical association between staff or workforce turnover or retention and sustainment or sustainability; (c) focused primarily on sustainment or sustainability or the authors mentioned that the program was not sustained; (d) focused on an EBP within health or education-related disciplines or that was a community-based intervention; and (e) referenced retention/turnover in relation to organization staff, volunteers, or EBP facilitators, as opposed to program participants or clinical intervention patients.

Expert panel

A panel of four professors and a research scientist from the University of Washington provided guidance and expertise to the first author. Panelists had expertise in conducting scoping reviews, D&I research (B.W., J.B., B.B., M.P.P, and L.S.) and EBP implementation and sustainability (L.S., B.B., and M.P.P.). The expert panel was convened for four in-person meetings between April 2018 and January 2019. They continued to provide guidance through email and videoconferences through November 2020. Expert panelists provided guidance on the development and application of the data abstraction tool (DAT), screening and validation process, mapping process, interpretation of results, and writing this manuscript.

Screening and validation

We conducted one screening phase (S1) and two validation phases (V1 and V2). During S1, the titles, keywords, and abstracts of 258 unique articles were reviewed by the first author utilizing the inclusion criteria. This resulted in 125 articles. During the literature search we found three articles that did not meet the first criterion, but whose full text included a discussion of the relationship between turnover and sustainability. We discussed this issue with the expert panel, who advised us to include the articles in the review. Adding three articles and removing duplicates across databases resulted in 41 articles for S1.

During V1, one coauthor (S.M.) performed an article validation screen by applying the inclusion criteria to 5% (n = 14) of the original 258 articles and assessing for interrater reliability. This validation screen yielded a 72% agreement rate. To address this, a second validation screen (V2) was conducted by S.M. In V2, 5% (n = 9) of the excluded articles from S1 were reviewed. V2 yielded a 94% agreement rate. A 100% agreement rate was achieved after discussion. After screening and validation, the number of articles was still 41.

Data abstraction

K.P. and S.M. created a DAT to extract relevant information from articles. The tool was developed after a full text review of 10% (n = 5) of included articles. K.P. and S.M. piloted the DAT on two articles and revised it based on recommendations from the expert panel. We did not calculate a reliability rate for the DAT; however, K.P. and S.M. applied the DAT to two included articles and compared results. Discrepancies were noted and discussed until consensus was reached. The final DAT had 28 items (see Appendix).

The data abstraction was completed by four readers: K.P., S.M., and two graduate students (L.H. and D.L.). Study data collected using the DAT were entered into REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Washington Institute of Translational Health Sciences1 (Harris et al., 2009). All readers attended a data abstraction and REDCap training with K.P. prior to data abstraction. Readers were randomly paired with either S.M. or K.P. (Pair 1: L.H. and S.M.; Pair 2: D.L. and K.P.). Reader pairs abstracted four articles, noting areas of disagreement. Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached and remaining articles were divided between readers to abstract individually. Final interrater reliability was completed by K.P., who randomly spot-checked nine articles (two from each reader and three double-abstracted articles) by reapplying the DAT and assessing for discrepancies. Differences were discussed with the original reader until consensus was reached.

An additional 21 articles were removed from the initial count of 41 after the data abstraction process, when a full-text assessment revealed a poor fit between the articles and review aims. Twenty articles were included for analysis.

March 2019 and June 2020 scoping review additions

Due to an extended project timeline, the expert panel recommended revisiting the literature to capture additional articles published after the initial search to ensure rigor. Identical database searches were conducted in March 2019 and June 2020, yielding in an additional 60 and 88 articles, respectively. Since K.P. had already been deemed reliable through the validation process described above, she applied identical inclusion criteria from S1 to the titles, keywords, and abstracts of the additional articles. Articles were removed if duplicative or if full-text assessment revealed poor fit with our aims. These additional searches resulted in three and seven additional articles, respectively, bringing the final included article total to 30. The DAT was applied to all 10 identified articles by first author K.P. and results were discussed with coauthor M.P.P.

Data analysis and synthesis

Our analysis and synthesis was guided by the PSF (Schell et al., 2013). We chose the PSF because it was developed for a wide variety of programs, is applicable across local, state, and national levels, and has been translated into a sustainability-measurement tool (Schell et al., 2013). The PSF describes program capacity for sustainability across eight domains (defined in Table 1): environmental support, funding stability, partnerships, organizational capacity, program evaluation, program adaptation, communications, and strategic planning (Schell et al., 2013; Washington University, n.d.).

Table 1.

Program sustainability framework (PSF)a definitions and operationalization.

| PSF domain | Definition | Operationalized definition |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental support | Having a supportive internal and external climate for your program | Impacts or recommendations that pertained to the organization or larger environment outside of the evidence-based program (EBP) |

| Funding stability | Establishing a consistent financial base for your program | Impacts or recommendations pertained to the financial state of the EBP or organization |

| Partnerships | Cultivating connections between your program and its stakeholders | Impacts or recommendations that pertained to EBP relationships with stakeholders or the community |

| Organizational capacity | Having the internal support and resources needed to effectively manage your program | Impacts or recommendations that pertain to existing or lacking organizational resources |

| Program evaluation | Assessing your program to inform planning and document results | Impacts or recommendations that pertained to assessment or evaluation of the EBP or larger implementing organization |

| Program adaptation | Taking actions that adapt your program to ensure its ongoing effectiveness | Impacts or recommendations that pertained to either EBP adaptation or fidelity |

| Communication | Strategic communication with stakeholders and the public about your program | Impacts or recommendations that pertained to communication between the organization and any involved collaborators or stakeholders, including EBP participants |

| Strategic planning | Using processes that guide your program's directions, goals, and strategies | Impacts or recommendations that pertained to long-term planning for the EBP or organization |

Schell, S. F., Luke, D. A., Schooley, M. W., Elliott, M. B., Herbers, S. H., Mueller, N. B., & Bunger, A. C. (2013). Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. In Implementation Science (Vol. 8). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15.

The first author mapped turnover impacts and recommendations to address turnover impact identified in the included articles onto the PSF domains. During the mapping process, the first author discussed intermediary results frequently with coauthors M.P.P. and L.S., and made changes based on the consensus reached during these discussions. Final mapping results were then discussed with the expert panel. This discussion led to the identification of emergent impacts of workforce turnover or recommendations to address workforce turnover that did not correspond with any PSF domains and therefore complemented the results of the deductive analysis using the eight PSF domains (Ravitch & Carl, 2016).

Results

Description of included studies

Table 2 provides an overview of all 30 articles. Articles were published between 2006 and 2020, and represent a variety of research designs: qualitative (43%, n = 13), mixed methods (30%, n = 9), observational (3%, n = 1), synthesis (7%, n = 2), experimental (3%, n = 1), quasi-experimental (3%, n = 1), and other (10%, n = 3). Study designs classified as “other” included program evaluation, workshop reports, and agent-based modeling. Seventeen articles focused primarily on sustainability. Fourteen articles provided a definition of sustainability: 64% cited outside sources and 36% provided their own definition. The definition of sustainability provided by Scheirer and Dearing (2011) was the most frequently cited by articles that referenced outside sources (n = 2). Cited and provided definitions are presented in Table 2. Articles described EBPs spanning fields of behavioral (13%, n = 4), physical (40%, n = 12) and mental health (20%, n = 6), and EBPs addressing chronic condition management (7%, n = 2), aging (3%, n = 1), substance abuse (7%, n = 2), homelessness (3%, n = 1), and education (7%, n = 2). Four articles examined more than one EBP.

Table 2.

Overview of studies included in scoping review (listed alphabetically).

| Authors and year | Study design | Stated study purpose | EBP | Type of EBP | Informative frameworks or theories used | Definition of sustainability/sustainment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August et al. (2006) | Experimentala | The present advanced-stage effectiveness trial sought to determine whether this same family service agency could sustain practice infrastructure and reproduce program effects with a new cohort of participants allowing supervision, implementation, and levels of participation to vary on the basis of ‘real-world’ conditions. Within the context of this advanced-stage effectiveness paradigm, the ET2 study assessed whether previously documented program benefits would be replicated with a new cohort of program recipients. (p.152) | Early risers “Skills for Success” | Early-age behavioral | Model of community-based program sustainability | (1) At the individual level, sustainability has been defined as the long-term effects of a program as assessed after 6 or more months following the most recent intervention contact (Glasgow et al., 1999). (2) At the setting or organizational level, sustainability refers to the extent to which an intervention becomes institutionalized or part of routine organizational policies and practices of an agency (Shediac-Rizkallah & Bone, 1998) |

| Bargmann and Brundrett (2020) | Mixed methods | This article describes the development, implementation, outcomes, and challenges of implementing an enhanced evidence-based fall prevention safety program on a medical-surgical unit. (p. 29) | Multifactorial fall prevention bundle | Health (fall prevention) | Iowa model | None provided |

| Bender et al. (2015) | Other | The purpose of this Workshop Report is to define the key concepts in IR as discussed during the workshop, provide examples of IR from experienced investigators, and describe the challenges, recommendations, and priorities for IR in respiratory, critical care, and sleep medicine that emerged from the meeting. (p. S214) | Multiple EBPs | Health | None | None provided |

| Bjorklund et al. (2009) | Other (Workshop Report) | This column describes Washington State's historic statewide initiative to implement ten high-fidelity assertive community treatment teams. (abstract) | High-fidelity Program of Assertive Community Treatment (WA-PACT) | N/A | None | None provided |

| Blaine, et al. (2017) | Mixed methodsa | This study describes the implementation of a school-based obesity prevention intervention within the Massachusetts CORD project (MA-CORD) in 2 low-income school districts. Using a mixed methods design, we assessed facilitators and barriers to achieving implementation outcomes adapted from the taxonomy of Proctor et al. (p. 2) | MA-CORD which contained the EBIs ‘Eat Well and Keep Moving’ and ‘Planet Health’ | Health (childhood obesity) | Outcomes for implementation research (Proctor et al., 2015) | Not directly, however they do provide an example: “sustainability (e.g., plans to continue offering the lessons in the following year)” |

| Bonham et al. (2014) | Mixed Methodsa | Our mixed-method study clarifies how [leadership, resources, and access to knowledge and information] influence delivery of EBPs for integrated treatment in community agencies and identifies agency profiles that can facilitate or hinder these changes. (p. 2) | Multiple EBPs related to mental health treatment | Mental health | CFIR | None provided |

| Boyle et al. (2017) | Mixed methodsa | The aim of this study was to conduct a process evaluation of the development and operation of the PCOS clinic after the first 12 months to assess (i) the consistency in applying the guidelines, (ii) barriers and enablers to using the service and (iii) its ability to meet the health needs of women and the community. (p.176) | Evidence-based polycystic ovary syndrome clinic | Health | None | None provided |

| Buller et al. (2015) | Mixed Methodsa | This paper reports the results of a long-term follow-up examining the sustainability of GSS 5 to 7 years after a trial in which it was disseminated throughout North America. (p. 2) | Under the Go Sun Smart brand (GSS) | Health Intervention (skin cancer) | None | Sustainability refers to the continuation of a program, its activities, and structures, when financial, organizational, and technical support from external organizations has ended |

| Conway et al. (2017) | Qualitativea | The aim of this study is therefore to describe the barriers and facilitators that indigenous healthcare worker's experience in providing SMS to indigenous Australians, as well as their perception of the appropriateness and effectiveness of the FCTGP in aiding self-management support (SMS), in order to inform and support chronic care management strategies in this population from these crucial stakeholders. (p. 3) | The Flinders Closing the Gap Program (FCTGP) | Chronic conditions and self-management | None | None provided |

| Dattalo et al. (2017) b | Mixed methodsa | The objective of this mixed methods study was to compare organizational readiness and implementation strategies used by rural communities that achieved varying levels of success in sustaining evidence-based health promotion programs over a 3-year time period. (…) This study examines the varying abilities of intervention sites from the randomized trial to implement and sustain SO and CDSMP workshop delivery over 3 years and compares different approaches to preparing for workshop implementation by level of sustainability. (p.359) | 1) Stepping On (SO) 2) Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) | Falls Prevention and Chronic Condition Self-Management | None | We defined successful sustainability as delivering ≥1 target workshop in both of the post-intervention years (years 2 and 3) |

| Forman et al. (2009) | Qualitativea | The purpose of this study was to determine the factors that are important to successful implementation and sustainability of evidence-based interventions in school settings and to identify directions for strengthening the connection between research and practice in the delivery of interventions in schools’ by interviewing those who have developed such interventions. (p.27) | 29 different EBPs | Educational | None | Continuing to carry out the intervention after initial implementation |

| Glisson et al. (2008) b | Qualitativea | The goal of this paper is to better understand organizational-based phenomena associated with the implementation of services in community-based mental health systems. The present study examines two issues likely to be necessary but not sufficient conditions for effective services-low therapist turnover and new program sustainability-and identifies organizational characteristics associated with each. The paper examines specific organizational social context and structural characteristics that could be important to the design of strategies to improve the services provided by mental health service organizations through the introduction of evidence-based practices and other innovations. (p.125, 128) | Multiple EBPs | N/A | Organizational theory, human relations theory, structural and socio-technical theory, open systems theory and organizational power and conflict theory | None provided |

| Gore et al. (2019) | Qualitative | Our study generates knowledge about how organizational and social contextual factors, such as features of the sites’ missions, resources, and relations with the communities they serve, influence the implementation of hypertension prevention and control programs in racial/ ethnic community sites. (p.3) | Racial and ethnic approaches to community health for Asian Americans (REACH FAR) project | Health | Consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) | Perceived sustainability, meaning actors’ perceptions about whether and how the intervention can be maintained or institutionalized in ongoing operations |

| Herlitz et al. (2020) | Synthesis | To understand the sustainability of school-based health interventions. (p. 2) | None specifically; literature review of health interventions in school settings | Educational | General theory of implementation | None provided |

| Herschell et al. (2009) b | Qualitativea | To enhance our understanding of mental health administrators’ perspectives on opportunities and challenges in implementing an evidence-based treatment, we conducted semi structured interviews with administrators of community mental health agencies. (p. 989) | Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) | Mental health, behavioral | None | None provided |

| Hunter et al. (2017) | Mixed Methodsa | In sum, the purpose of this study was to examine the extent of A-CRA sustainment following loss of federal funding among community-based organizations and identify what hypothesized implementation factors were empirically related to sustainment. (p.3) | Adolescent-community reinforcement approach (A-CRA) | Substance abuse | EPIS and CFIR | We operationalized sustainment by assessing the extent to which core treatment elements were maintained following the end of the implementation support period and adequate organizational capacity to continue maintenance of these core elements was demonstrated |

| Hunter et al. (2020) | Qualitativea | Identifying key factors that facilitated or hindered delivery of A-CRA following the end of the three-year, federally funded implementation support to community-based organizations. We aimed to examine whether these factors differed depending on the sustainment status of the organization. We also set out to examine whether the reported facilitators and barriers differed across staff from SOs and non-SOs and to provide illustrative examples from a clinical perspective. Finally, we examined how these reported factors aligned with the CFIR. (p. 2) | The adolescent community reinforcement approach (A-CRA) | Substance abuse | Consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) | Sustainment was assessed using a self-reported binary variable whereby the interviewee specified whether their organization had continued to offer A-CRA since completion of the implementation funding support phase |

| Kenny and Goodman (2010) | Quasi-experimental | The primary purpose of this project was (a) to conceptualize the evidence base for management of enteral tube feedings in adult patients, (b) to develop an EBP protocol based on review of the literature, (c) to implement the new protocol, and (d) to evaluate its impact. (p. S22) | The researchers developed and implemented their own EBP using the Iowa model (p. S23). | N/A | The Iowa model for EBPs | None provided |

| King et al. (2018) | Mixed Methoda | The aims of the present study are threefold: 1) to investigate whether early and late adopters of DBT have differential sustainability, 2) to investigate whether change in training method delivery impacts the sustain- ability of DBT programmes, and 3) to examine factors that act as a barrier or facilitator to implementation by using a theoretical implementation framework to guide assessment. (p. 3) | Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) | Mental health and behavioral health | Two. The first relates to factors considered to be relevant to practice sustainability and is adapted from Swain and colleagues’ study on the sustainability of EBPs in routine mental health agencies. The second is based on the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) | None provided |

| Lyons (2010) | Qualitativea | This study explored the impact of human relations dimensions of organizational culture on continence care practices of interdisciplinary teams in two nursing homes. (p. 328) | Multiple EBPs | Health (continence care) | Theory of organizational culture | None provided |

| McKay et al. (2018) | Other (agent-based modeling) | We use agent-based modeling, a computational systems science approach, in conjunction with existing EBI implementation frameworks and empirical data, to examine the relationships between staffing, sustainability, and population health. explore the relationship among human resources, EBI sustainability, and population outcomes to inform theoretical models of organizational capacity and demonstrate the use of ABM to address pressing EBI sustainability research questions. (p. 3) | Hypothetical EBP for HIV—data based on RESPECT | Health (HIV/STI risk behavior and prevention) | The organizational capacity model developed by Meyer, Davis, & Mays and Scheirer and Dearing's conceptual framework of EBI sustainability. | None provided |

| McKay et al. (2017) | Qualitativea | The current qualitative study draws on the concepts of individual and organizational capacity, as described in the Interactive Systems Framework, to examine the influence of human resources fluctuations on the implementation of RESPECT, an EBI widely disseminated and implemented through the Diffusion of Evidence-Based Intervention program (DEBI)’ (p. 1396) | RESPECT | Health (HIV/STI risk behavior and prevention) | Interactive systems framework | EBI maintenance/sustainability, or the extent which EBIs are provided consistently over time |

| Morgan et al. (2019) | Qualitativea | This paper reports the findings of a process evaluation conducted over two and half years, to inform the development and implementation of a rural PHC intervention, and identify barriers and facilitators to developing, implementing, and sustaining the intervention in a rural PHC team. (p. 2) | One day interdisciplinary primary health care memory clinic | Health | Consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) and rural primary health care model | None provided |

| Nelson et al. (2017) | Mixed Methodsa | The purpose of this paper is to examine the sustainment of the Housing First (HF) programs of Canada's At Home/ChezSoi research demonstration project for homeless persons with mental illness. (p.1) | At Home/Chez Soi Housing First | Homelessness and mental health | Wandersman et al.'s (2008) ecological model of factors that influence program implementation, interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation, sustainability outcomes framework, implementation program life cycle | (1) By sustainability, or sustainment, we mean program continuation, fidelity, integration into existing systems, and program expansion. (2) The most widespread definition of sustainability is that it is “…the continued use of program components and activities for the continued achievement of desirable program and population outcomes” (Scheirer et al.) |

| Peterson et al. (2014) | Observationala | The current study tests the hypothesis that the long-term sustainability of EBPs can be predicted by site characteristics, implementation characteristics, program reinforcement activities, and sustainability factors. (p.338) | Multiple EBPs | N/A | None | We defined a practice as sustained if it was continuously staffed and providing services to clients beyond the end of the implementation period, as confirmed by the site program leader. A program was discontinued when a practice was no longer provided. We excluded sites that restarted during the follow-up period of interest, as they did not fit into either category (sustained or discontinued) |

| Ploeg et al. (2014) | Qualitativea | To develop a research-based model of the process of spread of best practices related to older adults within home care settings. In this paper, the literature on spread will be briefly summarized, the rationale for focusing on the context of home care will be described, and the results of a grounded theory study of the process of spread of best practices in home care will be explained. (p. 1–2) | None specifically; “best practices related to caring for older adults” (p. 3). | Aging and elderly | Two frameworks for spread (grounded theory for spread) | Authors use the term “spread” to describe sustainability. Spread: “the process through which new working methods developed in one setting are adopted, perhaps with appropriate modifications, in other organizational contexts” (p. 2). “We considered spread to have occurred if the tools that were implemented on a small scale in a few sites or branches of an organization were then moved to and adopted (perhaps with revisions) in additional organizational sites. This was assessed through constant comparative analysis of all interviews conducted in each organization” |

| Quetsch et al. (2020) | Qualitativea | The objective of the current project was to assess agency administrators’ perspectives on DBT sustainability efforts and to understand how the process may be improved in future implementation efforts at CBBH agencies. Aims of the study included determining what agency administrators would find challenging about DBT implementation even after significant efforts by trainers were made to prepare agency staff, and themes on both DBT and sustainability as they related to agency resources, staff turnover, staff responsibilities, and benefits and difficulties of implementing DBT (p. 3) | Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) | Mental health and behavioral health | None | None provided |

| Skale et al. (2020) | Qualitativea | The study aim was to document and analyze the procedures used by a range of mental health agencies who are implementing and sustaining CPP and PCIT and the rationale for those approaches. (p. 3) | Parent–child interaction therapy and child–parent psychotherapy | Mental health and behavioral health | None | None provided |

| Tsai et al. (2017) b | Synthesis | Our aim was to better understand how to design effective oral health programmes to improve the oral health of Indigenous populations worldwide. To this end, we used systematic review methodology and qualitative analyses as the latter enables us to see the broader narrative and to uncover the interactions of multiple influences on programme design and implementation. (p. 390) | Multiple EBPs | Health (dental) | None | None provided |

| Xiang et al. (2018) | Qualitativea | The purpose of this study is to identify the facilitators and barriers associated with implementing and sustaining the Bridge Model at Community Based Organizations. (p.282) | The bridge model | Psychosocial | Promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework | None provided |

Note. ABM = agent-based modeling; A-CRA = adolescent-community reinforcement approach; CBBH = community-based behavioral health; CCP = child–parent psychotherapy; CDSMP = chronic disease self-management program; CFIR = consolidated framework for implementation research; DBT = dialectical behavior therapy; DEBI = diffusion of evidence-based intervention program; EBI = evidence-based intervention; EBP = evidence-based program; EPIS = exploration, preparation, implementation, and sustainment framework; IR = implementation research; GSS = go sun smart; HF = housing first; PCIT = parent–child interaction therapy; PHC = primary health care; REACH FAR = racial and ethnic approaches to community health for Asian Americans.

Collected qualitative, quantitative, or both to measure workforce turnover or intention. We are not including the data here as this is a scoping review and all methods of data collection and analysis, as well as definition of workforce turnover are too heterogeneous.

These articles did not meet all five inclusion criteria; however, based on the information provided in the title and/or abstract were selected for full-text review and discussion with authors M.P.P. and L.S. Upon review of the full text, the articles were included as they were deemed relevant to questions guiding this literature review.

Although all included articles mentioned workforce turnover, only 22 articles reported collecting workforce turnover data, as noted in Table 2. Of the remaining articles, five did not specify collection or analysis of turnover data, one used agent-based modeling to explore workforce turnover, and two were literature reviews. Of the 22 articles that collected turnover data, 17 collected turnover data qualitatively through focus groups, interviews, or open-ended survey questions, three collected data through agency reports or census rolls, and two gathered a combination of agency and qualitative data. One article provided a definition of turnover.

While the included studies did not empirically evaluate the causal relationship between turnover and sustainability, 29 articles discussed an impact of workforce turnover, and 18 shared recommendations to address turnover impacts. Therefore, in the next section we summarize impacts of turnover (Table 3) and recommendations for addressing them (Table 4) as reported by the included articles. We organize the remainder of this section according to the eight PSF domains, in the order they are presented in the original framework.

Table 3.

Impact of workforce turnover by program sustainability framework (PSF)a domain.

| PSF domain | Impact of workforce turnover |

|---|---|

| Environmental support | An evidence-based program (EBP) may become a lower organizational priority under new leadership |

| Funding stability | Training replacement staff drains organizational funding resources |

| Partnerships | Participants and respective communities may lose trust in the EBP staff if organizational changes are not communicated well |

| Critical professional relationships are lost | |

| Organizational capacity | Daily operations may suffer if there is a loss in organizational knowledge |

| Program delivery is delayed due to continuing staff priorities shifting to training new staff | |

| Remaining employee workload fluctuates to compensate for turnover gap | |

| Program evaluation | None identified in this review |

| Program adaptation | Organizational direction and focus can change, which can hinder EBP fidelity |

| Communication | Participants become vulnerable again as they form relationships with newly hired staff |

| Participant progress, reviews, and goals can be lost in staff transition, which can hinder individual progress in the EBP | |

| Strategic planning | Interim leadership focuses on daily rather than long-term tasks |

Schell, S. F., Luke, D. A., Schooley, M. W., Elliott, M. B., Herbers, S. H., Mueller, N. B., & Bunger, A. C. (2013). Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. In Implementation Science (Vol. 8). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15.

Table 4.

Recommendations to address impacts of workforce turnover by program sustainability framework (PSF)a domain.

| PSF domain | Recommendation to address workforce turnover impact |

|---|---|

| Environmental support | Diversify external support network as a broad safety net for unexpected funding, staffing or location conflicts |

| Incorporate evidence-based program (EBP) into daily tasks and routine to minimize gap in EBP responsibility and coverage in the event of turnover | |

| Focus on retaining and supporting organizational leadership to maintain steady organizational policies and a positive organizational climate | |

| Foster a positive organizational climate to retain remaining employees | |

| Funding stability | Increase and diversify funding portfolio |

| Examine both current and potential financial practices in order to best utilize resources available | |

| Utilize lower cost employee training alternatives such as online training | |

| Partnerships | Begin or increase the use of champions and volunteers to fill in gaps in EBP coverage and boost remaining staff morale |

| Create a community support network of stakeholders such as families, health providers, and health organizations to ensure program continuity | |

| Hire staff and use practices that reflect the communities served | |

| Organizational capacity | Increase training modalities utilized to maintain a willing and trained workforce |

| Increase the internal organizational capacity through additional interventions and shared work responsibilities | |

| Program evaluation | Assess organizational readiness among leadership and staff prior to program implementation to ensure adequate staffing and training for EBP sustainment |

| Incorporate the EBP evaluation into established organizational evaluations | |

| Program adaptation | Align EBPs with the internal and external context of the organization |

| Supplement in-person EBP delivery using alternative technology formats | |

| Communication | Increase culturally appropriate communication |

| Hold continuous conversations about the EBP throughout the organization to create cohesive teams of new and existing staff | |

| Strategic planning | Utilize a sustainability plan prior to EBP implementation and continue to monitor sustainability throughout implementation |

| Seek EBP developer support for implementation and sustainability | |

| Utilize a career advancement track and succession strategy to increase staff retention |

Schell, S. F., Luke, D. A., Schooley, M. W., Elliott, M. B., Herbers, S. H., Mueller, N. B., & Bunger, A. C. (2013). Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. In Implementation Science (Vol. 8). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-15.

Environmental support: impacts of turnover (four articles) and recommendations (three articles)

The impact of turnover on the internal support environment was observed in changes in organizational climate, priorities, or policies. Organizational climate had a bidirectional relationship with turnover: the resulting inconsistent workforce led to an increasingly poor organizational climate, negatively impacting EBP uptake and delivery (Bonham et al., 2014). In a study examining best home care practices for older adults, supervisor turnover resulted in changes in organizational priorities and policies. Inconsistent organizational policies and a lack of ongoing education on new priorities and policies made it difficult for remaining staff to learn new practice standards and internally support the EBP (Buller et al., 2015; Lyons, 2010; Ploeg et al., 2014).

Internal environmental support recommendations included: (a) support for agency leadership to secure key internal resources such as staff time, funding, and training (Dattalo et al., 2017); (b) incorporation of the EBP into larger organizational practices, for example, integrating school-based curriculum into lesson plans and recognizing the EBP's importance in the larger school environment (Blaine et al., 2017); and (c) building a positive organizational culture, associated with a reduction in turnover, and a positive organizational climate, associated with program sustainment, both of which help increase functionality and engagement while also decreasing workplace stress (Glisson et al., 2008).

Funding stability: impacts of turnover (eight articles) and recommendations (five articles)

Workforce turnover resulted in substantial financial impacts due to an increased need for hiring and training new personnel (Blaine et al., 2017; King et al., 2018; McKay et al., 2017, 2018; Skale et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2018). This was further exacerbated in multisite EBPs, where new employee training took place across multiple locations, requiring additional expenditures (Blaine et al., 2017). Furthermore, the financial burden of training new employees was amplified if the EBP was implemented in a resource-constrained organization unable to support training costs (Tsai et al., 2017) or continued programming (Hunter et al., 2020).

Funding recommendations focused on the need to generate consistent program funding: (a) securing adequate resources for training new staff (Bender et al., 2015; Bjorklund et al., 2009); (b) diversifying the organizational funding portfolio to include external financial resources, especially in preparation for or at the end of implementation funding (Hunter et al., 2017); (c) engaging stakeholders to establish best practices and examine overhead-to-direct care costs within programs (Herschell et al., 2009); (d) delivering online training, especially across multisite EBPs, to reduce training costs (Blaine et al., 2017); and (e) using incentives to promote and maintain staff engagement, bolstering program implementation and sustainment (Blaine et al., 2017).

Partnerships: impacts of turnover (four articles) and recommendations (four articles)

Workforce turnover impacted partnerships at individual, community, and professional levels. Turnover resulted in a loss of continuity of care and client trust, and fostered a larger sense of community mistrust as the organization was seen as incapable of retaining staff (Conway et al., 2017). It also resulted in a weakening or loss of community partnerships previously maintained by one or two key individuals (Xiang et al., 2018), which may have been essential to program success (Nelson et al., 2017). Further, turnover within community-based organizations weakened professional partnerships, decreasing the number of participant referrals (Xiang et al., 2018). Management turnover specifically impacted partnerships, as new leaders were often unaware of organizational norms and consequently did not engage the optimal partners in decision-making or initiatives (Lyons, 2010).

General partnership recommendations called for external partnerships, which would provide resources including workshop sites, recruitment of workshop participants, access to volunteers, and sharing staff to assist (with EBP), allowing more workshops to be implemented and sustained (Dattalo et al., 2017). Specific recommendations focused on (a) engaging volunteers or champions, who could maintain or boost staff morale in the face of turnover, and cover for staffing shortages (Bender et al., 2015; Blaine et al., 2017); (b) using a multilevel support and partnership strategy by involving participant families, health providers, health organizations settings, local communities, and state and national policymakers (Tsai et al., 2017); and (c) intentionally focusing on recruiting and involving members of target communities, such as tribal leaders (Tsai et al., 2017).

Organizational capacity: impacts of turnover (16 articles) and recommendations (nine articles)

Reported impacts on organizational capacity were loss of organizational knowledge, increased workloads, discontinued programming, and need for increased training. Loss of organizational knowledge was observed as a direct impact of turnover (Herlitz et al., 2020) and also as a consequence of the loss of professional relationships and the understanding of collaborating systems necessary to continue EBP services (Nelson et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2018).

Turnover of trained program staff resulted in program discontinuation (Bargmann & Brundrett, 2020; Bonham et al., 2014; Buller et al., 2015; Gore et al., 2019; Herlitz et al., 2020; Hunter et al., 2017; Kenny & Goodman, 2010; Morgan et al., 2019). Turnover also resulted in changing workloads, leaving remaining staff to cover additional responsibilities or unfamiliar EBP participants, decreasing the quality and timeliness of EBP delivery (August et al., 2006; King et al., 2018; Lyons, 2010; McKay et al., 2017, 2018; Nelson et al., 2017). The impact was particularly acute for supervisors who took on additional EBP responsibilities and had increased supervisory responsibility for new employees (McKay et al., 2017). Turnover, and the subsequent loss of organizational knowledge and capacity, also led to the need for increased training. Increased workloads and responsibilities (Morgan et al., 2019), as well as training facilitator shortages, further increased the difficulty of delivering training to newly-hired or reassigned staff (Dattalo et al., 2017).

Recommendations emphasized the importance of continuous training to maintain a willing and adequately-trained workforce in the event of turnover (Dattalo et al., 2017; Forman et al., 2009; McKay et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2017). Suggestions included (a) a “learning period” for EBP facilitators and clinicians, which allowed them to understand that evidence-based treatments are “easy and compatible” with current practices (Herschell et al., 2009); (b) online trainings as a low-cost way to keep staff trained (Blaine et al., 2017); (c) increased EBP training in formal educational settings to better prepare clinicians prior to workforce entry (Morgan et al., 2019; Skale et al., 2020); and (d) selecting clinicians who demonstrate commitment to and interest in the program or agency (Quetsch et al., 2020).

Recommendations also included increasing internal organizational capacity in response to the impact of turnover (Dattalo et al., 2017; McKay et al., 2017), such as through interventions focused on the cultivation of positive work environments and employee retention (McKay et al., 2017).

Program evaluation: program evaluation recommendations (two articles)

None of the included articles described an impact of turnover for this PSF domain. Several studies recommended focusing on organizational readiness, fitting the program-evaluation definition that includes assessment for planning purposes. These included evaluating (a) the need for employee training before EBP implementation; (b) the compatibility of the EBP with the organization (Herschell et al., 2009); and (c) readiness for change of both leadership and staff (Blaine et al., 2017). Such assessments are important because lower perceived readiness was associated with low EBP training engagement and higher rates of administrative and staff turnover (Blaine et al., 2017). An additional recommendation was the incorporation of yearly EBP performance evaluations within annual school evaluations (for a school-based EBP) as part of a larger institutionalization effort (Blaine et al., 2017).

Program adaptation: impacts of turnover (three articles) and recommendations (two articles)

Included articles did not explicitly reference effects of staff turnover on EBP adaptation. Rather, turnover, and especially repetitive or chronic turnover, was observed to hinder the organization's ability to adhere to the original EBP model, thereby hindering EBP fidelity (Bjorklund et al., 2009; McKay et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2017). The severity of the impact depended on the role of, and organizational knowledge held by, the staff turning over. Organizational leadership turnover had larger impacts on program fidelity as leaders were often responsible for organizational direction and focus, both of which determined EBP fidelity (Nelson et al., 2017). If staff turnover led to a concurrent loss in skills or EBP-specific knowledge, then the EBP was also likely to experience a decrease in fidelity (Bjorklund et al., 2009; McKay et al., 2017).

A specific recommendation related to program adaptation was provided in a study detailing a clinical EBP. Telehealth was proposed as an alternative staffing technique and form of program delivery in the event of turnover, especially in rural or remote locations (Boyle et al., 2017).

Communication: impacts of turnover (two articles) and recommendations (two articles)

High levels of staff turnover impacted communication at the participant level, as programs struggled to effectively “hand off” participants to new providers (August et al., 2006; Conway et al., 2017). Participant frustrations centered on having to communicate their story again with new providers and receiving inconsistent messaging from providers, leading to negative impacts on participant follow-up and progress (Conway et al., 2017). With frequent turnover, these impacts were cumulative and negatively affected participant engagement with the EBP (August et al., 2006).

Communication-domain recommendations varied in specificity, ranging from encouraging general communication to incorporating booster meetings. Culturally-appropriate communication with program participants was emphasized as a way to facilitate trust since miscommunication and poor health education feed into a cycle of suspicion, blame, and distrust (Conway et al., 2017). Communication was also viewed as a tool to engage current and new staff into a cohesive team (Bender et al., 2015).

Strategic planning: impacts of turnover (one article) and recommendations (four articles)

In a study examining different incontinence EBPs, frequent management turnover led to administrators taking on temporary roles as interim directors (Lyons, 2010). Strategic planning was impacted as interim directors focused on day-to-day management rather than long-term program development (Lyons, 2010).

Strategic planning recommendations included a call for a sustainability plan in addition to increased proactive short- and long-term planning from program developers and providers (August et al., 2006). Specifically, short-term activities should focus on key factors of sustainability, while long-term activities should focus on sustainability surveillance (August et al., 2006). Influential sustainability factors included stakeholder collaboration, the inclusion and participation of qualified staff, organizational stability, and fiscal oversight of the EBP (August et al., 2006). A similar recommendation called for the provision of a developer-created framework to guide program implementation and sustainability (Forman et al., 2009). A framework would help the organization assess program fit, foster stakeholder relationships, provide training and consultation, identify funding sources and mechanisms, and develop an EBP monitoring and evaluation system (Forman et al., 2009). Recommendations also included the use of formal documentation to record leadership commitment and encourage staff accountability to the intervention (Herlitz et al., 2020). Finally, planning for and utilizing a clear advancement track and succession strategy was recommended to mitigate the impacts of leadership turnover (Peterson et al., 2014).

Emergent crosscutting themes

We found two crosscutting themes did not fit within an a priori PSF domain, and instead emerged across domains during analysis of both impacts and recommendations: (a) leadership versus staff turnover, which explores the differences in turnover impact associated with organizational position, and (b) EBP participant stakeholder, which captures the role of the targeted EBP participant as an active stakeholder within the EBP as well as the organization delivering it.

Leadership versus staff turnover

The turnover of organizational leadership was observed to impact the PSF domains of environmental support, program adaptation, and organizational capacity while general staff turnover largely impacted the domain of partnerships. Organizational leaders were seen as responsible for maintaining organizational direction and focus. Consequently, leadership turnover was observed to result in changing organizational priorities and policies (Lyons, 2010; Ploeg et al., 2014), decreased EBP fidelity (Nelson et al., 2017), and altered EBP oversight and quality assurance (McKay et al., 2017). Conversely, general staff turnover was seen to impact community partnerships and relationships with EBP participants (August et al., 2006; Boyle et al., 2017; Conway et al., 2017; Lyons, 2010; Nelson et al., 2017; Xiang et al., 2018).

Recommendations to address the impacts of turnover specified by staff classification appeared in five of the included articles and represented five domains: environmental support, organizational capacity, partnerships, program evaluation, and strategic planning. Recommendations addressing impacts of leadership turnover focused on supporting current leaders through the use of advancement tracks or buffering the loss of a leader through preemptive succession strategies (Dattalo et al., 2017; Peterson et al., 2014). Recommendations addressing general staff turnover focused on assessing staff readiness prior to EBP implementation (Blaine et al., 2017), and training a large workforce and spreading EBP responsibilities to a wider range of staff and community members (Forman et al., 2009).

Participant stakeholders

Several articles within this review shared impacts of turnover or recommendations that were centered on the EBP participant, rather than the program itself, which is the focus of the PSF. Staff turnover was observed to erode participant trust (August et al., 2006) and quality of care (McKay et al., 2018) and, if cumulative, was found to decrease both participant and participant family engagement (August et al., 2006).

Recommendations to address the impact of workforce turnover focused on the EBP participant were minimal, found in only two articles (7%). Recommendations suggested using effective and culturally appropriate communication, language, and honest disclosures to foster participant trust (Conway et al., 2017) and proposed that implementing organizations should hire community members, building on an existing foundation of trust (Tsai et al., 2017).

Discussion

This scoping review summarized the evidence regarding the impact of workforce turnover on the sustainability of EBPs, and the recommendations for mitigating this impact shared by the included articles. The study was guided by the PSF (Washington University, n.d.), which includes eight domains related to an organization's ability to sustain an EBP. Our analysis shows that studies most frequently suggested three areas in which organizations could promote resiliency to workforce turnover: organizational capacity, fidelity, and funding. We identified two additional issues that organizations need to be aware of as they work toward EBP sustainability: the impact of leadership versus staff turnover, and the role of EBP participant stakeholders.

Workforce turnover decreases an organization's capacity to deliver an EBP, which can be mitigated by reassigning existing staff to serve in an interim role or hiring new staff. Additionally, organizations could proactively provide EBP training to staff across the organization, creating a level of redundancy that would prevent a lapse in EBP delivery. However, increased training can add financial burden to the organization (Brabson et al., 2020). This review found recommendations for organizations to invest in online training as a relatively cheap, reusable, and remote staff training option, especially in cases when in-person training is not feasible, such as the current pandemic. This is in agreement with previous work which found online trainings to be more cost-effective compared to in-person trainings for teachers and corporate training programs (Jung, 2005; Strother, 2002).

The loss of organizational capacity for EBP delivery can also be addressed by engaging volunteers and champions. Moreover, volunteers or champions who are community members can often act as a trusted liaison and enthusiastically speak to their EBP experience (Miyawaki et al., 2018).

Turnover that resulted in an inability to deliver EBPs as intended, due to loss of skills or new organizational priorities, was observed to reduce EBP fidelity. Recommendations called for increased integration of the EBP into daily organizational activities as well as increased assessment of long-term EBP alignment. This recommendation reinforces previous work exploring the implementation of a group exercise program for older adults, which highlighted the positive impact of alignment between the EBP and organization's mission on overall program success (Petrescu-Prahova et al., 2016).

In this review, the financial impacts of turnover were linked to hiring replacement staff and the funding of the EBP itself. The cost of turnover is in addition to the original implementation expense, a cost that is already considered a significant barrier to EBP sustainability (Bond et al., 2014; Roundfield & Lang, 2017). Recommendations called for diversified funding, adopting online trainings, creating new partnerships, and leveraging existing stakeholder relationships. These recommendations highlight the variety of financial strategies applied to support and sustain EBPs, as well as reinforce the call for future research and development of reliable EBP financial strategies (Dopp et al., 2020).

Several articles drew distinctions between staff and leadership turnover. Leadership turnover was observed to impact the larger workplace environment as replacement leadership was likely to enact different priorities or policies. This finding reinforces previous research showing that altered workplace environment, culture, and climate in response to leadership turnover can influence work attitudes of the remaining staff and predict 1-year staff turnover rates (Aarons et al., 2009), potentially leading to increased turnover rates among subsequent staff. Negative organizational climate has also been found to predict supervisor or administrator turnover (Brabson et al., 2019), potentially leading to cyclical leadership turnover.

Alternatively, EBP staff turnover resulted in participant frustration, lack of progress, and drop-out. Participant frustration and lack of progress can lead to disengagement. Previous work shows that participant disengagement can further weaken the provider–participant relationship, leading to diminished program outcomes (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006; Woltmann et al., 2008). Additionally, participant attrition can threaten the ability to deliver the EBP itself. This can be exacerbated if participant distrust spreads to the community, which may contain prospective or current EBP participants. Conversely, active EBP participant engagement has been observed to expand the applicability of research for hard-to-reach populations, increase the translation, dissemination and uptake of results, and increase the accountability and transparency of research within a community (Esmail et al., 2015). These findings emphasize the importance of the EBP participant as a stakeholder, as their progress and continued program engagement can impact long-term EBP sustainability.

This review had several limitations. Search terms may have been underinclusive, missing relevant articles due to the lack of truncated or wildcard searches. Additionally, the database search could have been expanded by increasing the use of antonym and synonym searches such as searching “attrition” in addition to “turnover OR retention,” capturing a larger subset of articles. This scoping review did not assess the quality of included studies, making it difficult to judge the validity of their results and to assess results across studies. While this limitation makes the comparison of study rigor difficult, it also allows for a broader incorporation of study designs and methodologies, allowing for increased understanding of the topic to inform further research. In addition, none of the included studies empirically examined the causal relationship between turnover and sustainability. Despite these limitations, this review advances the understudied field of sustainability (Wagenaar et al., 2020) in two important ways: (a) it highlights some actions that may help mitigate the impact of workforce turnover; and (b) it highlights the need for more rigorous research that clearly defines and measures workforce turnover and EBP sustainability, and that explicitly examines the causal relationship between workforce turnover and EBP sustainability. Quantitative analysis would complement the current qualitative work by building a credible evidence base on the relationship between turnover and sustainability, thus helping to inform the development and testing of strategies to address the impact of turnover on sustainability.

Future research should also explore the determinants of turnover and recommendations to address those determinants. This will allow for a better understanding of how turnover can be prevented rather than mitigating its effects. Additionally, research is needed on other sustainability determinants, like the larger policy environment or organizational resources. In doing so, future work could highlight more influential determinants, informing EBP organizations of the best place to spend limited time and resources while still sustaining the EBP. Finally, future research should examine when EBP sustainment is appropriate. While sustainment is considered a critical goal of EBPs, programs that are harmful or ineffective should not be continued, necessitating an understanding of the appropriateness of sustainability for each program.

Conclusion

EBPs are research-tested effective programs designed to result in positive outcomes for target populations. The sustainment of EBPs is critical to ensure and maintain the short- and long-term EBP benefits. Workforce turnover is one organizational-level factor that can threaten EBP sustainability. Better understanding of the impacts of workforce turnover on EBP sustainability can help organizations plan for mitigating its effects.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful for the contributions from Ms. Laura Harrington and Ms. Danielle Lucero, both concurrent graduate students at the University of Washington School of Social Work and School of Public Health during the completion of this project. Ms. Harrington and Ms. Lucero were both members of the graduate student review team and helped to extract data from the included articles. We also extend our gratitude to Ms. Clara Hill for her constructive comments and suggestions as we prepared this manuscript. For this project the use of REDCap electronic data capture software was supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1 TR002319. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix: Data abstraction tool items

The data abstraction tool collected the following information: first author's last name; year of publication; study type; purpose; research questions; provided definition of sustainability; source of sustainability definition; informative frameworks used; EBP; description of the EBP; EBP population; whether sustainability was the main focus of the article; the organization implementing the EBP; the workforce implementing the EBP; whether the status of staff employment was linked to turnover; whether turnover was linked to a specific subset of staff; whether turnover was an independent variable; how turnover was measured; turnover causes; strategies to prevent turnover; recommendations to address causes of turnover; impacts of staff turnover; strategies to prevent the impacts of turnover; recommendations to address the impacts of turnover; limitations of the article; future directions for research; additional graduate reader thoughts; additional graduate reader reflection.

REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: (a) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (b) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (c) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (d) procedures for importing data from external sources. REDCap at ITHS is supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1 TR002319.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Kelley M Pascoe https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0356-5464

References

- Aarons G. A., Sawitzky A. C. (2006). Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(3), 289–301. 10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons G. A., Sommerfeld D. H., Hecht D. B., Silovsky J. F., Chaffin M. J. (2009). The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 270–280. 10.1037/a0013223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- August G. J., Bloomquist M. L., Lee S. S., Realmuto G. M., Hektner J. M. (2006). Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community practice settings? The early Risers’ advanced-stage effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 7(2), 151–165. 10.1007/s11121-005-0024-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann A. L., Brundrett S. M. (2020). Implementation of a multicomponent fall prevention program: Contracting With patients for fall safety. Military Medicine, 185(2), 28–34. 10.1093/milmed/usz411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M. S., Damschroder L., Hagedorn H., Smith J., Kilbourne A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 32. 10.1186/S40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender B. G., Krishnan J. A., Chambers D. A., Cloutier M. M., Riekert K. A., Rand C. S., Schatz M., Thomson C. C., Wilson S. R., Apter A., Carson S. S., George M., Gerald J. K., Gerald L., Goss C. H., Okelo S. O., Mularski R. A., Nguyen H. Q., Patel M. R., … Freemer M. (2015). American Thoracic Society and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute implementation research workshop report. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 12(12), S213–S221. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201506-367OT [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund R. W., Monroe-DeVita M., Reed D., Toulon A., Morse G. (2009). State mental health policy: Washington state’s initiative to disseminate and implement high-fidelity ACT teams. Psychiatric Services, 60(1), 24–27. 10.1176/appi.ps.60.1.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine R. E., Franckle R. L., Ganter C., Falbe J., Giles C., Criss S., Kwass J. A., Land T., Gortmaker S. L., Chuang E., Davison K. K. (2017). Using school staff members to implement a childhood obesity prevention intervention in low-income school districts: The Massachusetts Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (MA-CORD project), 2012–2014. Preventing Chronic Disease, 14(1), E03. 10.5888/pcd14.160381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond G. R., Drake R. E., McHugo G. J., Peterson A. E., Jones A. M., Williams J. (2014). Long-term sustainability of evidence-based practices in community mental health agencies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(2), 228–236. 10.1007/s10488-012-0461-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham C. A., Sommerfeld D., Willging C., Aarons G. A. (2014). Organizational factors influencing implementation of evidence-based practices for integrated treatment in behavioral health agencies. Psychiatry Journal, 2014, 802983. 10.1155/2014/802983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle J., Hollands G., Beck S., Hampel G., Wapau H., Arnot M., Browne L., Teede H. J., Moran L. J. (2017). Process evaluation of a pilot evidence-based polycystic ovary syndrome clinic in the Torres Strait. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 25(3), 175–181. 10.1111/ajr.12288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabson L. A., Harris J. L., Lindhiem O., Herschell A. D. (2020). Workforce turnover in community behavioral health agencies in the USA: A systematic review with recommendations. In Clinical child and family psychology review (Vol. 23, Issue 3, pp. 297–315). Springer. 10.1007/s10567-020-00313-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabson L. A., Herschell A. D., Kolko D. J., Mrozowski S. J. (2019). Associations among job role, training type, and staff turnover in a large-scale implementation initiative. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 46(3), 399–414. 10.1007/s11414-018-09645-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller D. B., Walkosz B. J., Andersen P. A., Scott M. D., Cutter G. R. (2015). Sustained use of an occupational sun safety program in a recreation industry: Follow-up to a randomized trial on dissemination strategies. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 5(4), 361–371. 10.1007/s13142-015-0321-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D. A., Glasgow R. E., Stange K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8(1), 117–117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm M., Russell D., Humphreys J. (2011). Measuring rural allied health workforce turnover and retention: What are the patterns, determinants and costs? Australian Journal of Rural Health, 19(2), 81–88. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J., Tsourtos G., Lawn S. (2017). The barriers and facilitators that indigenous health workers experience in their workplace and communities in providing self-management support: A multiple case study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 319. 10.1186/s12913-017-2265-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dattalo M., Wise M., Ford J. H., II, Abramson B., Mahoney J. (2017). Essential resources for implementation and sustainability of evidence-based health promotion programs: A mixed methods multi-site case study. Journal of Community Health, 42, 358–368. 10.1007/s10900-016-0263-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp A. R., Narcisse M.-R., Mundey P., Silovsky J. F., Smith A. B., Mandell D., Funderburk B. W., Powell B. J., Schmidt S., Edwards D., Luke D., Mendel P. (2020). A scoping review of strategies for financing the implementation of evidence-based practices in behavioral health systems: State of the literature and future directions. Implementation Research and Practice, 1. 10.1177/2633489520939980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M. P., Mittman B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esmail L., Moore E., Rein A. (2015). Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: Moving from theory to practice. Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research, 4(2), 133–145. 10.2217/CER.14.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman S. G., Olin S. S., Hoagwood K. E., Crowe M., Saka N. (2009). Evidence-based interventions in schools: Developers’ views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health, 1(1), 26–36. 10.1007/s12310-008-9002-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garner B. R., Hunter B. D., Modisette K. C., Ihnes P. C., Godley S. H. (2012). Treatment staff turnover in organizations implementing evidence-based practices: Turnover rates and their association with client outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 42(2), 134–142. 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S., Nathans L. L., Seidel A. J., Greenberg M. T. (2017). Early head start start-up planning: Implications for staff support, job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(4), 443–458. 10.1002/jcop.21857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Vogt T. M. Boles S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C., Schoenwald S. K., Kelleher K., Landsverk J., Hoagwood K. E., Mayberg S., Green P., Weisz J., Chorpita B., Gibbons R., Green E. P., Hoagwood K., Jensen P. S., Miranda J., Palinkas L., Schoenwald S. (2008). Therapist turnover and new program sustainability in mental health clinics as a function of organizational culture, climate, and service structure. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1–2), 124–133. 10.1007/s10488-007-0152-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore R., Patel S., Choy C., Taher M., Garcia-Dia M. J., Singh H., Kim S., Mohaimin S., Dhar R., Naeem A., Kwon S. C., Islam N. (2019). Influence of organizational and social contexts on the implementation of culturally adapted hypertension control programs in Asian American-serving grocery stores, restaurants, and faith-based community sites: A qualitative study. Translational Behavioral Medicine, July. 10.1093/tbm/ibz106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]