Abstract

The ubiquity of C–H bonds presents an attractive opportunity to elaborate and build complexity in organic molecules. Methods for selective functionalization, however, often must differentiate among multiple chemically similar and, in some cases indistinguishable, C–H bonds. An advantage of enzymes is that they can be finely tuned using directed evolution to achieve control over divergent C–H functionalization pathways. Here, we demonstrate engineered enzymes that effect a new-to-nature C–H alkylation with unparalleled selectivity: two complementary carbene C–H transferases derived from a cytochrome P450 from Bacillus megaterium deliver an α-cyanocarbene into the α-amino C(sp3)–H bonds or the ortho-arene C(sp2)–H bonds of N-substituted arenes. These two transformations proceed via different mechanisms, yet only minimal changes to the protein scaffold (nine mutations, less than 2% of the sequence) were needed to adjust the enzyme’s control over the site-selectivity of cyanomethylation. The X-ray crystal structure of the selective C(sp3)–H alkylase, P411-PFA, reveals an unprecedented helical disruption which alters the shape and electrostatics in the enzyme active site. Overall, this work demonstrates the advantages of enzymes as C–H functionalization catalysts for divergent molecular derivatization.

1. Introduction

Given the ubiquity of C–H bonds in organic molecules, advancing selective C–H functionalization methodology can fundamentally simplify chemical synthesis.1–5 Ideally, precise and divergent alterations to a molecular scaffold would be achieved by using a panel of highly selective catalysts that can functionalize each C–H bond in a molecule, including both C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H bonds.6 Methods of this kind are promising in many settings, such as late-stage derivatizations of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and materials.4,7–9 Notwithstanding the appeal of this approach, design principles and methodologies featuring small-molecule catalysts with complementary selectivity are scarce. Successful examples have exploited directing groups to guide the functionalization of the desired C–H bonds.10–12 Divergent, highly selective methods that act on desired substrates absent of guiding functional groups are desired.3

Enzymes are ideal candidates to address unmet selectivity challenges in C–H functionalization reactions: catalyst-controlled selectivity can be achieved and reprogrammed in enzyme active sites through fine-tuned substrate alignments that enable complementary reaction outcomes. C–H hydroxylases and halogenases exemplify this impressive capability, with divergent chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity either found in nature or engineered using directed evolution (Fig. 1a).13–20 Over the past decade, our group and others have broadened the scope of enzymatic C–H functionalization reactions by introducing new transformations originally developed by synthetic chemists.21 Examples include repurposing haem proteins and non-haem Fe enzymes to selectively alkylate or aminate C–H bonds via carbene- or nitrene-transfer reactions22–25 and exploiting non-haem Fe enzymes for radical-mediated selective C–H azidation and nitration reactions.19,26,27 However, the vast majority of these efforts have focused on targeting a specific sp3-hybridized C–H bond (Fig. 1b); chemodivergent approaches to functionalizing C(sp3)–H bonds and arene C(sp2)–H bonds present in the same molecule are lacking.

Fig. 1 |. Reaction design.

a, Enzymatic C–H functionalization reactions can be highly selective and divergent; b, Previous work on abiological enzymatic C–H functionalization has mainly focused on modifying C(sp3)–H bonds; c, The goal of this study is to demonstrate that closely related C–H alkylases can enable divergent functionalization of arene C(sp2)–H bonds and nearby C(sp3)–H bonds; d, Model reaction for the initial activity discovery.

Here, we describe two complementary P450-based carbene transferases which can selectively introduce a cyanomethyl group into a C(sp3)–H bond or a nearby arene C(sp2)–H bond (Fig. 1c). Whereas enzymatic and transition-metal catalyzed C(sp3)–H carbene insertion are well documented,1,28–34 examples of highly selective intermolecular carbene transfer to an arene C(sp2)–H bond remain rare.35,36 In small-molecule catalysis, high regioselectivity is challenging to achieve via the postulated Friedel-Crafts-like electrophilic aromatic substitution mechanism.37,38 Site-selective transformations often occur at the least sterically demanding para-position.39–41 Meanwhile, state-of-the-art biocatalytic systems have been limited to electron-rich heteroaromatics.42,43 Inspired by these precedents, we set out to engineer carbene transferases that favor arene C–H functionalization, in order to complement reported “C(sp3)–H alkylases”. This complementary, chemodivergent enzymatic platform can enable straightforward generation of constitutional isomers, which are otherwise laborious to prepare and would require wholly different strategies and starting materials to access. Additionally, nitriles and their derivatives (e.g. amides) are well-established functional groups in medicinal chemistry that can be diversified readily in complexity-building transformations.44,45 We see this enzymatic platform as a proof of principle and starting point from which to generate new “C–H cyanomethylases” for functionalization of targeted C–H bonds in complex bioactive molecules.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Initial activity screening and reaction discovery

We commenced by evaluating the biocatalytic C–H carbene transfer reaction with N-phenyl morpholine 1a and diazoacetonitrile 2, which has multiple C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H bonds where cyanomethylation could occur (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Table 1). This transformation relies on the generation and transfer of an α-cyanocarbene intermediate,46 which has been reported in both chemocatalytic and biocatalytic systems for cyclopropanation, N–H and S–H insertion, and indole alkylation reactions.46–48 C–H cyanomethylation via catalytic carbene transfer has not been reported. In initial studies, we examined the enzymatic C(sp3)–H cyanomethylation reaction with a panel of 82 different variants of axial serine-ligated cytochromes P450 (P411s, previously engineered for abiological carbene transfer reactions) (Supplementary Table 1). The haem cofactor alone is not an active catalyst for this reaction. Many of the P411 variants, however, catalyzed the carbene insertion into the α-amino C(sp3)–H bond of 1a, affording 3a with moderate yields. Notably, P411-PFA, a carbene transferase previously engineered to catalyze α-amino C(sp3)–H fluoroalkylation,30 afforded the α-amino C(sp3)–H cyanomethylation product with 11% yield.

We were fascinated to observe that a small number of P411 variants also exhibited basal-level ortho-arene C–H functionalization activity when diazoacetonitrile 2 was used as the carbene precursor (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 1) in a small number of P411 variants (Supplementary Table 1). This activity was not seen in previous studies using diazoesters (e.g. ethyl diazoacetate, EDA) or perfluorinated diazo compounds (e.g. 2,2,2-triflurodiazoethane).29,30 The formation of 4a is not catalyzed by the haem cofactor, nor is it produced by the cellular background. Notably, whereas P411-PFA is a selective C(sp3)–H alkylase (3a/4a ratio = 4:1), variant P411-FA-E3, which differs by only a single mutation (P401L) to P411-PFA, exhibits the highest 4a/3a ratio (1:2) among the enzymes tested. Even though P411-FA-E3’s carbene transfer selectivity towards the arene C–H bond is still poor, this result encouraged us to explore the extent to which arene C–H functionalization selectivity could be improved by directed evolution, and whether we could develop a set of chemodivergent C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H carbene transferases.

2.2. Structural studies of P411-PFA

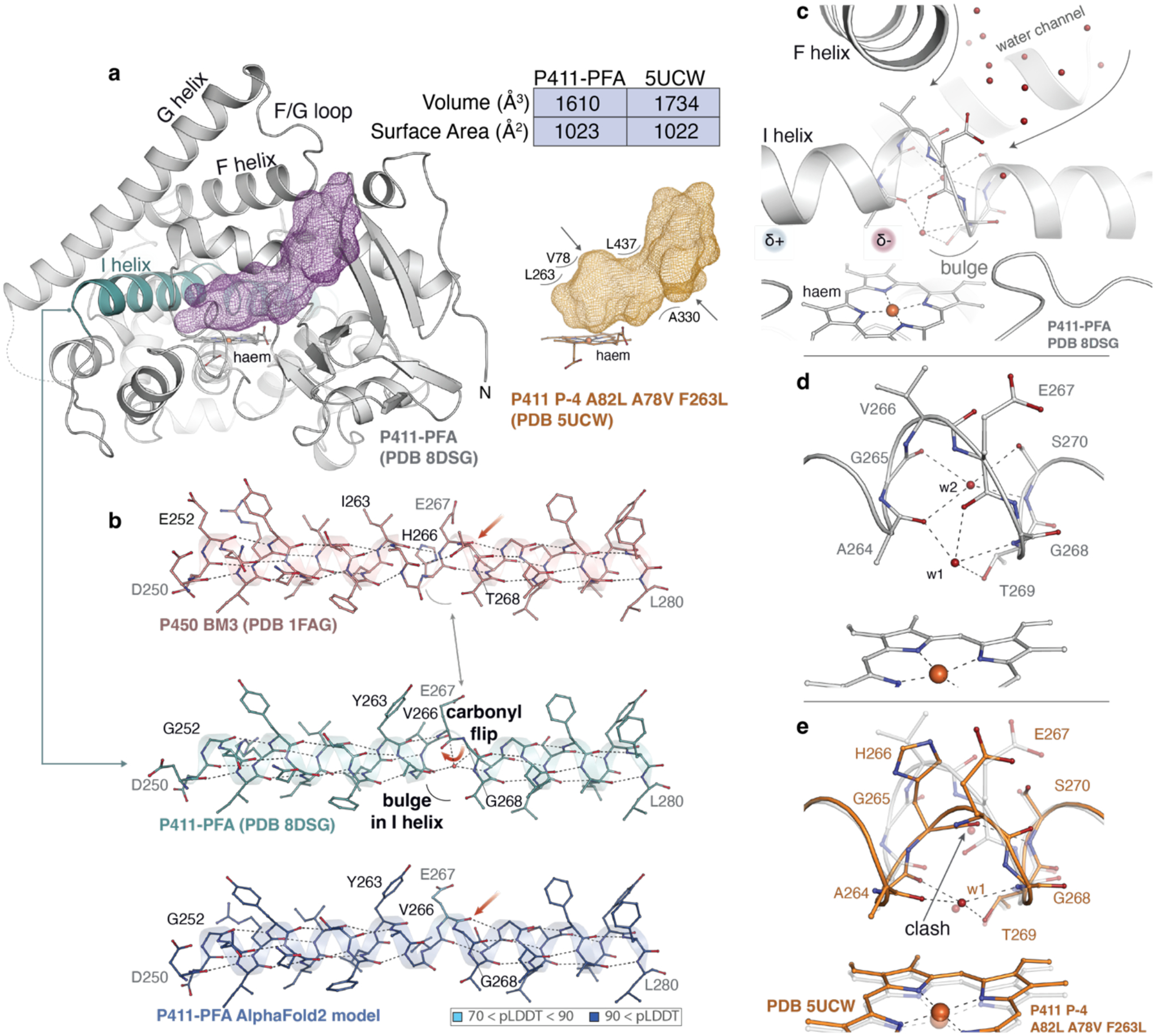

To gain structural insight into the α-amino C(sp3)–H cyanomethylase and help guide the directed evolution of a highly selective arene C–H cyanomethylase, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of P411-PFA’s haem domain to 1.87 Å resolution (PDB 8DSG). P411-PFA adopts an overall architecture similar to previously solved structures of cytochromes P450 and P411.49–51 Compared to variant P-4 A82L A78V F263L, an intermolecular C–H aminase which functionalizes benzylic C–H bonds using tosyl azide as a nitrene precursor,51 and the closest P411 variant to P411-PFA, whose structure has been reported (PDB 5UCW), P411-PFA contains 13 additional mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2), most of which are near the active site. Relative to the aminating P411, the total substrate pocket volume of P411-PFA shrank by ~7%, affording a shallower cavity directly above the haem (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 3). This likely better accommodates the smaller carbene precursors used for its directed evolution and the precise requirement of steric interactions to orient the substrate for carbene insertion at the selected position.

Fig. 2 |. Crystallographic studies of P411-PFA (PDB 8DSG).

a, Overall fold (white cartoon) and active site cavity of P411-PFA (left, purple mesh) compared to a closely related C–H aminase, P-4 A82L A78V F263L (PDB 5UCW) (right, orange mesh); b, An unusual backbone carbonyl flip is observed in the I helix (teal) of P411-PFA at residue position E267. The E267 carbonyl is indicated by a red arrow. Mutations on the I helix from wild type P450BM3 to P411-PFA are indicated as black residue labels. The AlphaFold2-predicted model of P411-PFA successfully templated the bulged helix, but (unsurprisingly) failed to capture the rearrangement of the I helix and carbonyl flip; c, Close-up view of the helical bulge which resides at the bottom of a water channel. The disruption of the I helix generates a partial dipole near the active site, which may make the local electronic environment more favorable for diazo binding and activation. Waters stabilizing the bulged helix in d, P411-PFA (white) and e, P411-PFA are overlaid on P-4 A82L A78V F263L (orange).

Beyond these similarities, an unusual helical backbone conformation is observed in the structure of P411-PFA, which alters the shape of the active site. (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 4). In the I helix of wild-type P450 BM3, there is a distortion over a single turn of the helix between residues 263 and 268. This breaks the standard hydrogen bonding pattern of this α-helix, leading to a bulge in the center of the helix and a conformation reminiscent of the i + 5 → i hydrogen bonding pattern present in a π-helix.52 In the P-4 A82L A78V F263L aminase structure, this helical bulge is stabilized by a water molecule (w1) likely present but not modeled in P450 BM3 (PDB 1FAG), indicating a feature that has persisted over many generations of directed evolution of this enzyme (Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, this distortion is expanded in the structure of P411-PFA; a backbone carbonyl flip present at position 267, which fully disrupts the helical hydrogen bonding network, traps a second water molecule (w2) within an expanded coil and breaks the standard I helix into two distinct helices. This breakage results in the accumulation of complementary dipoles on either side of this expanded coil, altering the electrostatics in the active site (Fig. 2c–e, Supplementary Fig. 5). Intriguingly, whereas P411-PFA contains 26 haem-domain mutations compared to wild-type P450 BM3, E267 had not been changed (Supplementary Fig. 6). Instead, mutations flanking the helical bulge around E267, L263Y and H266V, which have been introduced to enhance carbene and nitrene C–H insertion activities,29,50 likely stabilize the otherwise unfavorable flipped conformation of the E267 carbonyl.

2.3. Directed evolution of a selective arene C(sp2)–H carbene transferase

To develop highly active and selective arene C(sp2)–H carbene transferases, we used P411-FA-E3 as the starting enzyme for directed evolution by sequential rounds of site-saturation mutagenesis and error-prone PCR mutagenesis and screening (by GC-FID) (Fig. 3a). To preserve the novel structural feature (helical disruption) found in P411-PFA, which might be beneficial for carbene-transfer activity, we targeted amino acid residues for site-saturation mutagenesis on the opposite side of the active site from the disrupted I helix and those previously found to affect abiological carbene- and nitrene-transfer activities (Fig. 3b, c). We found beneficial mutations within the proximal active site pocket (A87V, M177Y, W325C, V330C, and M354V) as well as distal ones that affect the chemoselectivity of the protein catalysts (S118Q, G252L).

Fig. 3 |. Reaction discovery and directed evolution of a C(sp2)–H cyanomethylase.

Reaction conditions: anaerobic; 5 mM 1a or 1b; 48 mM 2 (9.63 equiv.); E. coli whole cell harboring P411 variants (OD600 = 30) suspended in M9-N aqueous buffer (pH 7.4); 10% v/v EtOH (co-solvent); room temperature; 18–20 h. a, Initial activity screening revealed the formation of C(sp3)–H insertion product 3a and ortho-arene C–H alkylation product 4a; b, Locations of beneficial mutations are highlighted in the P411-PFA structure; c, Directed evolution of a highly selective arene C(sp2)–H cyanomethylase; d, Observed product distribution with 1b includes ring-expanded Buchner products. Basic pH suppresses Buchner product formation (5b, *inseparable mixture of tautomers).

Meanwhile, in comparison to P411-FA-E3, α-amino C(sp3)–H cyanomethylase P411-PFA contains an additional L401P mutation in the axial “Cys pocket” (L401P), which disrupts the hydrogen bond between the amide proton of residue 402 and axial serine ligand (Supplementary Fig. 7); mutations in this pocket are known to tune the electronic property of haem.49,53,54 The different selectivities of these two variants encouraged us to investigate whether mutations at other residues in the Cys pocket improve arene C(sp2)–H functionalization selectivity. F393W was identified as a beneficial mutation from site-saturation mutagenesis of this region. In summary, a total of seven rounds of mutagenesis and screening yielded the final variant P411-ACHF (arene C–H functionalization enzyme, Supplementary Table 2), which contains eight additional mutations relative to P411-PFA (Fig. 3b). Under yield-optimized reaction conditions (Supplementary Table 3), arene C(sp2)–H cyanomethylase P411-ACHF delivers 4a in 51% yield and excellent chemoselectivity (4a:3a = 17:1).

2.4. Enzymatic Buchner ring expansion reaction

Like many small-molecule arene C–H carbene-transfer catalysts,37,55–57 P411-ACHF also exhibits (low) Buchner ring expansion activities. We observed the highest level of Buchner product when the enzyme was challenged with 1b and 2 (Fig. 3d). In that case, P411-ACHF cyclopropanates 1b, and due to the electron-withdrawing effect of the nitrile group, the α-proton in the cycloheptatriene is highly acidic. Therefore, the product can readily tautomerize to 5b (Supplementary Fig. 7). Interestingly, the enzymatic Buchner ring expansion reaction is sensitive to the pH of the reaction buffer (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Table 4). We found that mildly basic conditions (pH 7.4–8.0) minimize the ring expansion side product.

2.5. Substrate scope studies of P411-PFA and P411-ACHF

We investigated the substrate scope of the reaction under yield-optimized conditions with the two highly selective but distinct cyanomethylases, P411-PFA and P411-ACHF. As shown in Fig. 4, these enzymes are capable of alkylating N-substituted arenes with complementary chemoselectivity (Fig. 4a). Without any additional protein engineering, the previously engineered C(sp3)–H fluoroalkylase P411-PFA efficiently installs cyanomethyl groups to secondary, α-amino C(sp3)–H bonds with high chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity. Whereas P411-PFA functionalizes the C(sp3)–H bonds of these N-substituted arenes (3a–e, Fig. 4a), P411-ACHF alkylates their arene ortho-C–H bonds (4a–e). Notably, even though introduction of the cyanomethyl group to an arene C(sp2)–H bond does not establish a new stereocenter, when a racemic mixture of 1j is used as the substrate, P411-ACHF preferentially converts the (R)-enantiomer into the ortho-cyanomethylation product (4j) with 81:19 e.r. via a kinetic resolution (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Table 6).

Fig. 4 |. Substrate scope study.

a, Substrate scope of P411-PFA and P411-ACHF. Analytical yields of desired products were determined by using their GC calibration curves (See Supplementary Information, Section VII). Reaction conditions: anaerobic; 2.5 mM 1; 51.6 mM 2 (20.63 equiv.); E. coli whole cells harboring P411 variants (OD600 = 30) M9-N aqueous buffer (pH 7.4); 10% v/v EtOH (co-solvent); room temperature; 18–20 h. Yields and total turnovers (TTNs) are reported as the averages of the triplicate experiments (See Supplementary Table 5); b, The arene C(sp2)–H functionalization activity and selectivity can be further optimized on individual target molecules; c, Chemodivergent, preparative-scale syntheses using P411-PFA and P411-ACHF. Reaction conditions: anaerobic; 5 mM 1d; 48 mM 2 (9.63 equiv.); E. coli whole cells harboring P411 variants (OD600 = 30) M9-N aqueous buffer (pH 7.4); 10% v/v EtOH (co-solvent); room temperature; 18–20 h.

Substrate recognition in the enzyme active site is key to carbene-transfer selectivity. P411-PFA preferentially functionalizes the secondary α-amino C(sp3)–H bonds in the presence of other C–H bonds with similar bond-dissociation energies (e.g. benzylic C–H bonds in 1d and 1e). Meanwhile, P411-ACHF exhibits exclusive selectivity toward ortho-C–H bonds (to nitrogen) over other activated positions (positions ortho to –OMe in 4m). Transition metal-catalyzed carbene transfer to C(sp2)–H bonds of N-substituted arenes, in contrast, favors the kinetically more accessible para-positions.40,41 The para-positions are likely sterically occluded by the enzyme, leading to the observed ortho-selectivity. Overall, the substrate scope studies reveal that the multiple potential non-covalent interactions between the enzymes and the substrate are key to determining carbene transfer selectivity, and a small number of mutations can cause these new-to-nature enzymes to discriminate nearby C–H bonds.

Although chemoselectivity of P411-ACHF is not yet excellent with some substrates, directed evolution should be able to improve activity and selectivity on any specific substrate. As proof-of-concept, we performed an additional round of directed evolution using 1b as the new model substrate and identified Y263W as a beneficial mutation. The optimized variant, P411-ACHF Y263W, with decreased active site volume, delivers 4b with 54% yield and >10:1 4b:3b ratio (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 7). To demonstrate the synthetic utilities of these enzymes, we performed chemodivergent derivatization of 1d using P411-PFA and P411-ACHF on preparative scale, where the enzymes yielded constitutional isomers 3d and 4d with 30% (1-mmol scale, 56 mg) and 37% (2-mmol scale, 136 mg) isolated yield, respectively (Fig. 4c).

3. Conclusion

We have demonstrated that complementary, closely related P450-based carbene transferases can selectively functionalize either a C(sp3)–H bond or an arene C(sp2)–H bond present in the same molecule. These results support our proposal that the divergent, native C–H hydroxylating selectivity widely exhibited by P450s can be re-established in a non-native enzymatic reaction. Given these results, it is reasonable to expect that these enzymes can serve as starting points from which to evolve C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H alkylases to functionalize any targeted C–H bond with high selectivity, provided some promiscuous activity for that targeted position can be found. In fact, as we have shown here, ‘generalist’ enzymes that are less selective are excellent starting points from which to evolve catalysts that are highly selective for a desired transformation.

Furthermore, we have obtained an enzyme for unprecedented C(sp2)–H carbene transfer to arenes which are not activated heteroaromatics (indole, pyrrole, etc.). Structural studies revealed an unusual helical disruption in the active site of these cyanomethylases that is neither observed in reported P450 structures nor captured by computational structure predictions (AlphaFold2). This underscores the advantages of using directed evolution to establish new-to-nature functions in engineered enzymes, which often calls for new structural features that differ from the native protein and may be challenging to predict or design. In summary, we hope that these complementary carbene C–H functionalization enzymes promote the use of biocatalysts to perform challenging, divergent C–H alkylation reactions with selectivity unmatched by chemical catalysts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by the National Institute of General Medical Science of the NIH (R01GM138740). E.A. is supported by a Ruth Kirschstein NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship (F32GM143799), R.M. is supported by Swiss National Science Foundation (P2ELP2_195118). N.J.P. acknowledges support from Merck and the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation through the Merck-HHWF Fellowship. We thank Prof. Douglas C. Rees for providing space and resources to carry out the crystallography studies, Dr. Scott C. Virgil, Dr. Jens T. Kaiser, and Dr. Mona Shahgholi for analytical assistance. We also thank Dr. Sabine Brinkman-Chen, Dr. Jennifer L. Kennemur, Dr. Zhen Liu, and Dr. David C. Miller for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Beckman Institute at Caltech for their generous support of the Molecular Observatory at Caltech. We thank the staff at Beamline 12-2, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) operations which are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (DE-AC02-76SF00515). The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41GM103393).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

All data necessary to support the paper’s conclusions are available in the main text and the Supplementary Information. The haem domain structure of P411-PFA is available through the Protein Data Bank ID 8DSG. Plasmids encoding the enzymes reported in this study are available for research purposes from F.H.A. under a material transfer agreement with the California Institute of Technology.

References

- 1.Davies HML & Manning JR Catalytic C–H functionalization by metal carbenoid and nitrenoid insertion. Nature 451, 417–424 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies HML, Bois JD & Yu J-Q C–H functionalization in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 40, 1855–1856 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartwig JF & Larsen MA Undirected, homogeneous C–H bond functionalization: Challenges and opportunities. ACS Cent. Sci 2, 281–292 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaguchi J, Yamaguchi AD & Itami K C–H bond functionalization: Emerging synthetic tools for natural products and pharmaceuticals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 51, 8960–9009 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalton T, Faber T & Glorius F C–H activation: Toward sustainability and applications. ACS Cent. Sci 7, 245–261 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Börgel J & Ritter T Late-stage functionalization. Chem 6, 1877–1887 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cernak T, Dykstra KD, Tyagarajan S, Vachal P & Krska SW The medicinal chemist’s toolbox for late stage functionalization of drug-like molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev 45, 546–576 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillemard L, Kaplaneris N, Ackermann L & Johansson MJ Late-stage C–H functionalization offers new opportunities in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Chem 5, 522–545 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fazekas TJ et al. Diversification of aliphatic C–H bonds in small molecules and polyolefins through radical chain transfer. Science 375, 545–550 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neufeldt SR & Sanford MS Controlling site selectivity in palladium-catalyzed C–H bond functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res 45, 936–946 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai H-X, Stepan AF, Plummer MS, Zhang Y-H & Yu J-Q Divergent C–H functionalizations directed by sulfonamide pharmacophores: Late-stage diversification as a tool for drug discovery. J. Am. Chem. Soc 133, 7222–7228 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sambiagio C et al. A comprehensive overview of directing groups applied in metal-catalysed C–H functionalisation chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 47, 6603–6743 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greule A, Stok JE, Voss JJD & Cryle MJ Unrivalled diversity: The many roles and reactions of bacterial cytochromes P450 in secondary metabolism. Nat. Prod. Rep 35, 757–791 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kille S, Zilly FE, Acevedo JP & Reetz MT Regio- and stereoselectivity of P450-catalysed hydroxylation of steroids controlled by laboratory evolution. Nat. Chem 3, 738–743 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang K, Shafer BM, Demars MD, Stern HA & Fasan R Controlled oxidation of remote sp3 C–H bonds in artemisinin via P450 catalysts with fine-tuned regio- and stereoselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 18695–18704 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukowski AL et al. C–H hydroxylation in paralytic shellfish toxin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 11863–11869 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X et al. Divergent synthesis of complex diterpenes through a hybrid oxidative approach. Science 369, 799–806 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andorfer MC, Park HJ, Vergara-Coll J & Lewis JC Directed evolution of RebH for catalyst-controlled halogenation of indole C–H bonds. Chem. Sci 7, 3720–3729 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neugebauer ME et al. A family of radical halogenases for the engineering of amino-acid-based products. Nat. Chem. Biol 15, 1009–1016 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi T et al. Evolved aliphatic halogenases enable regiocomplementary C−H functionalization of a pharmaceutically relevant compound. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 18535–18539 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen K & Arnold FH Engineering new catalytic activities in enzymes. Nat. Catal 3, 203–213 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y & Arnold FH Navigating the unnatural reaction space: Directed evolution of heme proteins for selective carbene and nitrene transfer. Acc. Chem. Res 54, 1209–1225 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang RK, Huang X & Arnold FH Selective C–H bond functionalization with engineered heme proteins: New tools to generate complexity. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 49, 67–75 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandenberg OF, Fasan R & Arnold FH Exploiting and engineering hemoproteins for abiological carbene and nitrene transfer reactions. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 47, 102–111 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Natoli SN & Hartwig JF Noble-metal substitution in hemoproteins: An emerging strategy for abiological catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res 52, 326–335 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews ML et al. Direct nitration and azidation of aliphatic carbons by an iron-dependent halogenase. Nat. Chem. Biol 10, 209–215 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rui J et al. Directed evolution of nonheme iron enzymes to access abiological radical-relay C(sp3)−H azidation. Science 376, 869–874 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle MP, Duffy R, Ratnikov M & Zhou L Catalytic carbene insertion into C−H bonds. Chem. Rev 110, 704–724 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang RK et al. Enzymatic assembly of carbon–carbon bonds via iron-catalysed sp3 C–H functionalization. Nature 565, 67–72 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Huang X, Zhang RK & Arnold FH Enantiodivergent α-amino C–H fluoroalkylation catalyzed by engineered cytochrome P450s. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 9798–9802 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou AZ, Chen K & Arnold FH Enzymatic lactone-carbene C–H insertion to build contiguous chiral centers. ACS Catal 10, 5393–5398 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Key HM, Dydio P, Clark DS & Hartwig JF Abiological catalysis by artificial haem proteins containing noble metals in place of iron. Nature 534, 534–537 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dydio P et al. An artificial metalloenzyme with the kinetics of native enzymes. Science 354, 102–106 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu Y, Natoli SN, Liu Z, Clark DS & Hartwig JF Site-selective functionalization of (sp3)C−H bonds catalyzed by artificial metalloenzymes containing an iridium-porphyrin cofactor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 13954–13960 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caballero A et al. Catalytic functionalization of low reactive C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H bonds of alkanes and arenes by carbene transfer from diazo compounds. Dalton Trans 44, 20295–20307 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z & Wang J Cross-coupling reactions involving metal carbene: From C═C/C–C bond formation to C–H bond functionalization. J. Org. Chem 78, 10024–10030 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fructos MR et al. A gold catalyst for carbene-transfer reactions from ethyl diazoacetate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 44, 5284–5288 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conde A et al. Iron and manganese catalysts for the selective functionalization of arene C(sp2)−H bonds by carbene insertion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 55, 6530–6534 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu Z et al. Highly site-selective direct C–H bond functionalization of phenols with α-aryl-α-diazoacetates and diazooxindoles via gold catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 6904–6907 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu B, Li M-L, Zuo X-D, Zhu S-F & Zhou Q-L Catalytic asymmetric arylation of α-aryl-α-diazoacetates with aniline derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 8700–8703 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmberg-Douglas N, Onuska NPR & Nicewicz DA Regioselective arene C−H alkylation enabled by organic photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 59, 7425–7429 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vargas DA, Tinoco A, Tyagi V & Fasan R Myoglobin-catalyzed C−H functionalization of unprotected indoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 9911–9915 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brandenberg OF, Chen K & Arnold FH Directed evolution of a cytochrome P450 carbene transferase for selective functionalization of cyclic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 8989–8995 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang W et al. Enantioselective cyanation of benzylic C–H bonds via copper-catalyzed radical relay. Science 353, 1014–1018 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lennox AJJ et al. Electrochemical aminoxyl-mediated α-cyanation of secondary piperidines for pharmaceutical building block diversification. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 11227–11231 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mykhailiuk PK & Koenigs RM Diazoacetonitrile (N2CHCN): A long forgotten but valuable reagent for organic synthesis. Chem. – Eur. J 26, 89–101 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chandgude AL & Fasan R Highly diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of nitrile-substituted cyclopropanes by myoglobin-mediated carbene transfer catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 15852–15856 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hock KJ et al. Tryptamine synthesis by iron porphyrin catalyzed C−H functionalization of indoles with diazoacetonitrile. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 58, 3630–3634 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coelho PS et al. A serine-substituted P450 catalyzes highly efficient carbene transfer to olefins in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol 9, 485–487 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hyster TK, Farwell CC, Buller AR, McIntosh JA & Arnold FH Enzyme-controlled nitrogen-atom transfer enables regiodivergent C–H amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 15505–15508 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prier CK, Zhang RK, Buller AR, Brinkmann-Chen S & Arnold FH Enantioselective, intermolecular benzylic C–H amination catalysed by an engineered iron-haem enzyme. Nat. Chem 9, 629–634 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooley RB, Arp DJ & Karplus PA Evolutionary origin of a secondary structure: π-Helices as cryptic but widespread insertional variations of α-helices that enhance protein functionality. J. Mol. Biol 404, 232–246 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ost TWB et al. Structural and spectroscopic analysis of the F393H mutant of flavocytochrome P450 BM3. Biochemistry 40, 13430–13438 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krest CM et al. Significantly shorter Fe–S bond in cytochrome P450-I is consistent with greater reactivity relative to chloroperoxidase. Nat. Chem 7, 696–702 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ford A et al. Modern organic synthesis with α-diazocarbonyl compounds. Chem. Rev 115, 9981–10080 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reisman SE, Nani RR & Levin S Buchner and beyond: Arene cyclopropanation as applied to natural product total synthesis. Synlett 2011, 2437–2442 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fleming GS & Beeler AB Regioselective and enantioselective intermolecular Buchner ring expansion in flow. Org. Lett 2017, 5268–5271 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data necessary to support the paper’s conclusions are available in the main text and the Supplementary Information. The haem domain structure of P411-PFA is available through the Protein Data Bank ID 8DSG. Plasmids encoding the enzymes reported in this study are available for research purposes from F.H.A. under a material transfer agreement with the California Institute of Technology.