Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with photosensitization using 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) [including a nanoemulsion (BF-200 ALA)] is approved in the USA for the treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs); another derivative, methyl aminolevulinate, is not approved in the USA but is used in Europe. For AK treatment, the photosensitizer may be applied to individual AK lesions or, depending on treatment regimen, to broader areas of sun-damaged skin to manage field cancerization, although not all products are approved for field treatment. ALA-PDT and photosensitizers have also been used off-label for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancers, primarily basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (cSCC). Advantages of PDT include potentially improved cosmesis and patient satisfaction; disadvantages include pain and duration of treatment. Alternative illumination approaches, including intense pulsed light as well as pulsed-dye lasers, have also been used successfully. Pretreating the affected tissue or warming during incubation can help to increase photosensitizer absorption and improve therapeutic efficacy. Combinations of multiple treatments are also under exploration. Reducing incubation time between photosensitizer application and illumination may significantly reduce pain scores without affecting treatment efficacy. Substituting daylight PDT for a conventional illumination source can also reduce pain without compromising efficacy. The objective of this narrative review is to describe current and ongoing research in the use of topical photosensitizers and modified light delivery regimens to achieve improved therapeutic outcomes with less toxicity in patients with AK, cSCC, BCC, and field cancerization.

Keywords: Actinic keratosis, Basal cell carcinoma, Field cancerization, Photodynamic therapy, Squamous cell carcinoma

Key Summary Points

| Photodynamic therapy using aminolevulinic acid and derivatives as a photosensitizer is approved in the USA for the treatment of actinic keratosis, but many off-label uses have been investigated. |

| Photodynamic therapy has been used successfully to treat field cancerization and basal cell carcinoma. |

| Innovations in photodynamic therapy protocols include alternative light sources, mechanical skin pretreatment or warming to increase photosensitizer absorption, and combination therapy. |

| Variations to improve tolerability and convenience include shortened preincubation times and daylight photodynamic therapy. |

| Further study is needed to explore the benefits of these innovations across larger and more diverse patient populations. |

Introduction

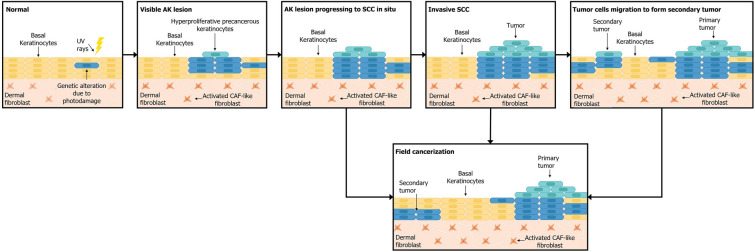

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) are a heterogeneous group of cutaneous malignancies originating from epidermal keratinocytes [1–3]. The two most common types of NMSCs, which constitute 99% of NMSC cases, are basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) [1, 3–5]. Actinic keratoses (AKs) are a precancerous form of cSCC, with a highly variable risk of malignant transformation (Fig. 1) estimated to be between 0.025% and 16% [6].

Fig. 1.

Chronic ultraviolet (UV) radiation damages the epidermal layer leading to atypical keratinocytes, including AK. When left untreated, the lesions can develop into SCC in situ that further progresses to invasive SCC. Subclinical genetic alterations may progress and form field cancerization underneath normal-appearing skin [16]. AK actinic keratosis, CAF cancer-associated fibroblast, SCC squamous cell carcinoma, UV ultraviolet

Risk factors for NMSC include but are not limited to age, skin phototype (lighter), occupational exposure, climate, and lifetime exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation [7–11]. One major modifiable risk factor for NMSC is chronic exposure to ultraviolet radiation, which may induce actinic and DNA damage to any anatomic area with insufficient sun protection (classically, the scalp, head, neck, and dorsal extremities) [6, 12, 13]. As a result of diffuse, cumulative actinic damage, even clinically normal-appearing skin in areas adjacent to NMSC and AKs may harbor deleterious genetic alterations, termed field cancerization (Fig. 1) [14–16]. In a longitudinal cohort study conducted between 2009 and 2020 that included 220,236 patients with AK and matched healthy individuals, the mean incidence of cSCC was 1.92 per 100 person-years [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.89–1.95] in patients with AK versus 0.83 per 100 person-years in healthy individuals without AK [95% CI 0.81–0.85; subdistribution hazard ratio (95% CI) 1.90 (1.85–1.95)] [12]. Furthermore, younger patients (< 49 years of age) with AKs are seven times more likely to develop cSCC compared with the general population [12]. Hence, early detection and treatment of AKs and anatomic areas with AKs are of utmost importance for long-term NMSC management.

A nonsurgical treatment option is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which involves application of a topical photosensitizer that is then activated with visible light [2, 4]. Topical photosensitizers are precursors of protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) that, when activated, catalyze formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to induce apoptosis and necrosis of the atypical keratinocytes [2, 4, 17]. Three topical agents are commonly used as photosensitizers for PDT: aminolevulinic acid (ALA); an esterified formulation, methyl aminolevulinate (MAL); and a nanoemulsion-based gel formulation containing 7.8% 5-ALA (10% ALA hydrochloride) (BF-200 ALA) [2, 4, 18, 19]. In the USA, 20% 5-ALA solution with blue light illumination is indicated for the treatment of minimally to moderately thick AK of the face, scalp, or upper extremities [20], while BF-200 ALA with red light illumination is approved for both lesion-based and field-based treatment of mild-to-moderate AKs of the face and scalp [21]. In Europe, while specific approvals vary across countries, MAL and BF-200 ALA with red light are approved to treat mild-to-moderate AKs on the face and bald scalp, cSCC in situ, and superficial and nodular BCCs [19, 22]. PDT is not recommended for BCCs > 2 mm in thickness or for more aggressive forms such as basisquamous, morpheaform, or infiltrating subtypes [2, 23]; for lesions > 2 mm thick, debulking the lesions gently before initiating PDT is suggested [24].

PDT is relatively effective for the treatment of AK. In a meta-analysis comparing 25 European studies with ten different treatment modalities for mild-to-moderate AKs of the face and scalp including ALA applied as a gel (BF-200 ALA-PDT) or patch, MAL-PDT, imiquimod (in three different combinations of concentration and treatment duration), cryotherapy, 3% diclofenac, 0.5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and ingenol mebutate, BF-200 ALA-PDT was the most effective based on total patient clearance 12 weeks after treatment (estimated odds ratio, 45.9; 95% CI 13.9–151.8) [25]. Other advantages of PDT include potentially improved cosmesis and patient satisfaction, while drawbacks include pain and duration of treatment [2, 4].

The purpose of this review is to synthesize and highlight recent and ongoing research on the use of PDT for the management of AK, field cancerization, and NMSC (off-label), as well as developments that may improve PDT efficacy, tolerability, and cosmesis. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. PubMed was searched from inception to February 2022 using the search terms [(aminolevulinic acid OR aminolevulinate) AND photodynamic therapy] with (broad area OR field-directed), (squamous cell carcinoma OR basal cell carcinoma), and (efficacy OR pain OR tolerability). The most relevant findings, as well as other recent publications of interest, are summarized with respect to advances in clinical application, innovations in PDT protocols, and use in organ transplant recipients.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Advances in Clinical Application

In addition to AKs, physicians have successfully explored PDT treatment for field cancerization as well as for individual superficial and nodular BCC, SCC in situ, and cSCC lesions [4, 18].

PDT in Field Cancerization Treatment

As there is no reliable way to identify subclinical lesions or AKs with malignant potential in areas with actinic damage, it is desirable to treat the entire cancerized field in addition to individual lesions. Large body surface areas with multiple subclinical lesions are difficult to treat with surgery, and topical therapy can be compromised by nonadherence as a result of brisk local skin reactions or prolonged treatment regimens [26]. In these cases, PDT may be useful as an alternative or adjunctive therapy to help maximize quality of life and minimize morbidity and mortality.

Clinical trials have shown ALA-PDT to be safe and highly effective in the treatment of minimally to moderately thick AKs and field cancerization (Table 1) [27, 28]. In a 52-week trial, 166 high-risk patients with facial AKs previously treated with cryotherapy and biopsy-confirmed photodamaged “clinically normal” skin were randomized to undergo two (baseline and week 4) or three (baseline, week 4, and week 24) sessions of field-directed therapy with broadly applied 20% ALA (or vehicle) to the entire face with a 1-h incubation time followed by blue light illumination [27]. At week 52, compared with the vehicle-PDT arm, patients who received three treatments with ALA-PDT had significantly fewer AKs (least squares mean, 2.1 versus 4.7; P = 0.0166), greater probability of having no AKs (37.5% versus 18.9%, P = 0.0089), and numerically longer duration of response [mean (95% CI), 33.3 (28.0–38.5) weeks versus 25.9 (20.2–31.6) weeks]; they also developed fewer new NMSCs (five new NMSCs in 5/56 patients versus 12 new NMSCs in 7/53 patients; P = 0.0014) [27]. No clinically significant differences in efficacy or safety were noted between two and three ALA-PDT sessions [27]. A phase 3 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study evaluated field-directed treatment with 10% BF-200 ALA gel and red light PDT in 87 adult patients with mild-to-moderate AKs of the face and/or scalp [28]. At the 12-week follow-up after the last PDT treatment, field-directed PDT achieved complete AK clearance in 91% of BF-200 ALA-treated patients compared with 22% of vehicle-treated patients (P < 0.0001) [28].

Table 1.

Interventional studies of PDT for field cancerization summarized

| References | Study type | Patient pop | Patient char | Lesions | Anatomical location | PDT treatment | Light source | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piacquadio et al. [27] | RCT | 166 patients; 135 M, 31 F |

Mean ± SD age, years: ALA 2×, 67.9 ± 9.7 ALA 3×, 66.7 ± 9.4 VEH, 65.8 ± 9.5 |

Multiple AK and diagnosis of NMSC on sun-exposed areas | Head and neck | 20% 5-ALA for 1 h | Blue light illumination for 16 min 40 s, 2× or 3× | Broad-area PDT in patients with high risk of developing new lesions |

Week 52 recurrence rates ALA 2×: 7.7% (P = 0.0004) ALA 3×: 6.1% (P < 0.0001); LS mean number of AKs ALA 2×: 3.0 ALA 3×: 2.1 (P = 0.0166) |

| Reinhold et al. [28] | RCT | 87 patients; 79 M, 8 F | Mean ± SD age, 71.6 ± 6.4 years | Mild-to-moderate AKs | Face and/or scalp | 10% BF-200 ALA gel for 3 h ± 10 min or vehicle | BF-RhodoLED red light PDT | 10% BF-200 ALA with red light PDT with vehicle |

Complete AK clearance BF-200 ALA: 91% Vehicle: 22% (P < 0.0001) |

AK actinic keratosis, ALA aminolevulinic acid, char characteristics, F female, LED light-emitting diode, LS least squares, M male, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PDT photodynamic therapy, pop population, RCT randomized controlled trial, SD standard deviation, VEH vehicle

PDT for Basal Cell Carcinoma Management

PDT has shown therapeutic efficacy as an off-label treatment for BCC in clinical practice [4]. Because PDT cannot penetrate lesions beyond 2 mm deep, the use of surgical curettage to reduce tumor depth to less than 2 mm followed by subsequent PDT may be beneficial in the treatment of BCC [23, 29]. Data suggest that debulking thicker tumors prior to PDT treatment increases complete response rate after 3 years of follow-up relative to older studies where pretreatment debulking may not have been performed [29, 30].

Studies utilizing 5-ALA or MAL have demonstrated promising results for the treatment of BCC (Table 2) [29, 31–33]. In a 3-year, prospective, open-label trial of 174 adult patients with dermoscopically/histologically confirmed superficial BCC and nodular BCC, combining curettage of visible tumor (sparing dermis and adjacent normal skin) with 16% MAL cream and photoactivation with red light-emitting diode (LED) light for 23 min resulted in overall 3-year clearance rates of 96.1% after a mean of 2.6 sessions for superficial BCC and 95.2% after a mean of 2.7 sessions for nodular BCC [29]. An open-label trial assessing 12% 5-ALA-PDT gel with a 3-h incubation period and photoactivation with red light for the treatment of superficial BCCs on the head and neck, trunk, and extremities achieved a complete response rate of 95.8% at 3 months after the second treatment session and a 3-year recurrence-free survival rate of 88.3% [31]. In another interventional cohort study of histologically confirmed BCCs < 2 mm deep in adult patients, 20% 5-ALA ointment with a 4-h incubation time under occlusion and red light illumination resulted in complete response for 47/54 lesions (87%) after only one session and for an additional 5/54 lesions after two sessions [32]. In a small pilot interventional study [33], three patients with basal cell nevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome) underwent six ALA-PDT treatments in three biweekly (day 1 and day 7) sessions spaced 2 months apart. Each tumor was treated with 20% ALA, and matching contralateral treatment zones were illuminated with red light and blue light after a 4-h incubation. Blue light treatment was noninferior to red light treatment for BCC complete response rate (98% versus 93%; P < 0.001 for noninferiority with a 5% margin), and greater pain was anecdotally reported following red versus blue light treatment (no statistical analysis) [33].

Table 2.

Interventional studies with PDT in BCC summarized

| References | Study type | Patient pop | Patient char | BCC type | Anatomical location | PDT treatment | Light source | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gómez et al. [29] | Retrospective | 174 patients; 89 M and 85 F | sBCC: 76 lesions, mean age 71.1 ± 12.9 years; nBCC: 144 lesions, mean age 73.8 ± 12.7 years | sBCC and nBCC | Face, scalp, neck, trunk, arms, and legs | 16% MAL for 3 h | Red LED lamp (23 min exposure) | 2–3 MAL-PDT sessions |

Overall clearance rates at 3-year follow-up sBCC: 96.1% [95% (CI) 92–100%] nBCC: 95.2% [95% (CI) 92–99%] |

| Filonenko et al. [31] | Prospective | 82 patients; 15 M, 67F | Mean age: N/A | sBCC | Face, head, neck, trunk, and extremities | 12% 5-ALA gel for 3 h | 630 nm laser, energy density 350 J/cm2 | Two 5-ALA-PDT treatments on face, head, neck, trunk, and extremities of patients with sBCC |

RFS 1 year: −92.1% 3 year: −88.3% |

| Woźniak et al. [32] | RCT | 50 patients; 27 M, 23 F | Mean age (M) 71.8 years and (F) 63.5 years | sBCC, nBCC, infiltrating, and sclerosing | Trunk and head | 20% ointment 5-ALA for 4 h | Two different wavelengths: 405 nm violet diode and 638 nm red diode | Novel laser light source in PDD and PDT in patients with BCC |

CR sBCC: 97.2% nBCC: 66.7% Infilt: 50% Scl: 0% |

| Maytin et al. [33] | Prospective | Three patients; 2 M, 1 F | 33, 39, and 54 years of age | BCC | Scalp, face, neck, arms, legs, and back | 20% solution of 5-ALA for 4 h | Half tumors illuminated with red light and half with blue light | Head-to-head comparison of blue light versus red light in Gorlin syndrome |

Lesion clearance rates Blue light: 98% Red light: 93% |

5-ALA-PDT aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy, BCC basal cell carcinoma, char characteristics, CI confidence interval, CR complete response, F female, Infilt infiltrating, LED light-emitting diode, M male, MAL methyl aminolevulinic acid, N/A not applicable, nBCC nodular BCC, PDD photodynamic diagnosis, PDT photodynamic therapy, pop population, RCT randomized clinical trial, RFS relapse-free survival, sBCC superficial BCC, Scl sclerosing

Safety and efficacy of PDT for BCC has also been reported in numerous case studies (Table 3) [34–38]. Successful treatment and/or reduced growth of treated tumors after use of 20% ALA with red light illumination or 20% 5-ALA-PDT with blue light illumination have been observed in histologically confirmed superficial BCC, nevoid BCC syndrome, and multiple pigmented BCCs [35, 36, 38].

Table 3.

Case reports with PDT in BCC

| References | Patient pop | BCC subtype | Anatomical location | Photosensitizer treatment | Light source | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salvio et al. [34] |

Two patients; 56-year-old F, 52-year-old F |

Multiple pigmented BCC | Upper limb and trunk | 20% MAL for 3 h for first session and 1.5 h for second | Red LED lamp (20 min exposure) | Two sessions of MAL-PDT | No recurrence of all lesions after 24 months of follow-up |

| Trafalski et al. [35] | 82-year-old M | Histopathologically confirmed BCC | Face | 20% 5-ALA for 2 h | Red light illumination | PDT at 2-week intervals for 3 months | No recurrence after 12 months of follow-up |

| Chapas et al. [36] | 73-year-old M | Multiple sBCC and nBCC (nevoid BCC syndrome) | Face and chest | 20% 5-ALA for 1 h | Blue light source | Broad-area PDT | Reduced size and number of existing BCC |

| Itkin et al. [37] | Two patients; 21-year-old F, 47-year-old F | sBCC and nBCC (nevoid BCC syndrome) | 21-year-old: right upper lip, left mastoid prominence, right biceps and left triceps area; 47-year-old: face, lower extremities | Delta-ALA for 1–5 h | Blue light source | Broad-area PDT, two courses 2–4 months apart |

Complete clinical resolution: sBCC, face: 89% sBCC, lower extremities: 67% nBCC, face: 31% |

| Lane et al. [38] | 56-year-old M | Unilateral localized BCC | Left scapular back and left posterior arm | 5-ALA | Blue light illuminator | PDT | “Excellent therapeutic response” with no new clinically visible BCC for 18 months |

5-ALA-PDT aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy, BCC basal cell carcinoma, F female, LED light-emitting diode, MAL methyl aminolevulinic acid, nBCC nodular BCC, PDT photodynamic therapy, pop population, sBCC superficial BCC

Innovations in PDT

Alternative approaches have been investigated to advance efficacy (Table 4 [39–58]), tolerability (Table 5 [59–66]), and convenience of PDT.

Table 4.

Summary of studies on innovations in PDT to improve effectiveness

| References | Study type | Patient pop | Patient char | Lesions | Anatomical location | PDT treatment | Light exposure | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light source | |||||||||

| Ruiz-Rodriguez et al. [49] | Case series | 17 patients; 4 M, 13 F | N/A | AKs and chronic actinic damage | Face and scalp | 20% 5-ALA in oil-in-water emulsion incubated 4 h with occlusion | Epilight IPL device with 615 nm cutoff filter, total fluence 40 J/cm2, double pulse mode of 4.0 ms with a delay time of 20 ms between pulses; repeated after 1 month | IPL PDT |

1 month after first treatment: Resolution of 29/38 (76.3%) AKs 1-month and 3-month follow-ups: No visible AKs in 15/17 patients; resolution of 33/38 (91%) AKs |

| Avram and Goldman [40] | Retrospective | 17 patients; 5 M, 12 F | Mean age 52 years (range 38–78 years) | AKs and signs of photoaging | Face | 20% ALA solution incubated for 1 h | Vasculite Elite IPL device with 560 nm filter, 28–32 J/cm2 with a double pulse of 3.0 and 6.0 ms with a 10-ms delay | IPL PDT | 68% of AKs resolved after one treatment; one nBCC did not respond after three treatments |

| Piccolo et al. [48] | Observational | 25 patients; 15 M, 10 F | Mean age, 71.3 years; range 54–93 years | AK, sBCC, and BD | Face | MAL for 3 h | Activation with IPL device (Photosilk plus, DEKA M.E.L.A. S.r.l.) with cutoff wavelength 550 nm; fluence 18 J/cm2; triple pulse mode 3.3, 3.9, and 4.6 ms; interpulse delay, 100 ms with epidermal cooling | MAL-treated patients with IPL in NMSC |

AKs: CR: 90% PR: 10% sBCC: CR: 80% PR: 20% BD: CR: 100% PR: 0 |

| Kessels et al. [43] | Long-term follow-up | 61 patients (M) | Mean age ± SD, 73.7 ± 7.5 years | Multiple AKs | Scalp and forehead | MAL for 3 h | PDL illumination on left side (595 nm, Vbeam, Candela Corporation®, 7 mm spot size, fluence 7 J/cm2, pulse duration 10 ms, epidermal cooling 30/10 ms, 50% overlap) and LED-PDT on right side of the face (Aktilite®, Galderma Benelux, 37 J/cm2, 635 ± 18 nm) | Compared efficacy of LED-PDT with PDL-PDT, and a long-term follow-up |

Mean decrease in number of lesions from baseline to 12-month follow-up LED-PDT: −4.25 (95% CI −5.07; −3.43) PDL-PDT: −3.88 (95% CI −4.76; −2.99) |

| Abrouk et al. [39] | Prospective | 220 patients; sex N/A | 88 received treatment for AK and 126 for photodamage | AKs | Face | 20% 5-ALA for 2 h | Illuminated with one of the following: (PDL, PDL + blue light, IPL, or IPL + blue light); all fluences 6–12 J/cm2, pulse width of 5–20 ms with contact cooling | IPL versus PDL with or without blue light for activation of PDT | IPL + blue light demonstrated increased efficacy when compared with IPL, PDL, or PDL + blue light |

| Pretreatment | |||||||||

| Torezan et al. [52] | Prospective split-face trial | Ten patients; 1 M, 9 F | Mean age 65.2 years | ≥ 3 AKs | Face | MAL cream incubated 90 min with occlusion | Red LED light, 50 mW/cm2, 37 J/cm2 | Microneedle pretreatment (1.5 mm long × 0.1 mm wide, roller device) versus gentle curettage |

Average AK clearance after 90 days: Microneedle-assisted PDT: 90.5% Conventional PDT: 86% |

| Lev-Tov et al. [44] | Prospective split-face trial | 48 patients completed study endpoints for pain; 40 M, 8 F | Mean age 67.7 years; range 49–86 years | AKs | Forehead | 20% 5-ALA solution incubated for 20, 40, or 60 min (microneedle side) or 60 min (sham side) | Blue light exposure for 8 min, total fluence 4.8 J/cm2 | Microneedle pretreatment (690 micron length) versus sham treatment |

Complete AK response rate after 1 month (microneedle versus sham): 20 min: 71.4% versus 68.3% 40 min: 81.1% versus 79.9% 60 min: 72.1% versus 74.2% |

| Petukhova et al. [47] | Split-face RCT | 32 patients; 22 M, 10 F |

Mean ± SD age: 20-min arm: 62.8 ± 2.1 years 10-min arm: 65.4 ± 2.5 years |

≥ 3 Grade II AKs | Face | 20% 5-ALA solution incubated for 10 or 20 min | Blue light illumination for 1000 s, total fluence 10 J/cm2 | Microneedle pretreatment (200 μm length, roller device) versus sham treatment |

AK clearance at 1-month follow-up, microneedle versus sham: 20-min arm: 76% versus 58% (P < 0.01) 10-min arm: 43% versus 38% (P = 0.66) |

| Spencer and Freeman [51] | Prospective split-face | 19 patients; sex N/A | N/A | ≥ 4 nonhyperkeratotic AKs per side | Face | 20% 5-ALA solution incubated for 1 h | Blue light illumination for 1000 s | Microneedle pretreatment (0.5 mm length, stamp-style device) versus no pretreatment |

Mean percentage reduction in AKs after 2 and 4 months: Microneedle side: 89.3% Control side: 69.5% (P < 0.05) |

| Miller et al. [45] | Proof of concept | 19 patients; sex N/A | N/A | BCC, cSCC, and multiple AKs | Face, lip, scalp, forehead, temple, hand, and leg | 20% 5-ALA for 1 h | Blue light exposure for 16 min and 40 s | CO2 laser AFR | Pretreatment with AFR provided superior clearance of AKs and thin NMSCs at 6 months compared with 5-ALA-PDT alone |

| Jang et al. [57] | Prospective, single-arm | 29 patients; 7 M, 22 F | Mean age 68.4 years (standard deviation, 11.1 years) | AK | Face (majority), back, leg | 20% 5-ALA for 90 min (17 lesions); MAL cream for 70 min (17 lesions) | Red light at 100 J/cm2 for ALA; red light at 37 J/cm2 for MAL | CO2 laser AFR | Complete response in 70.6% of lesions after three treatment sessions |

| Falkenberg et al. [56] | Prospective, single-arm | 28 patients; 22 M, 6 F | Mean age 74 ± 8.9 years | AK | Scalp and/or face | 5-ALA nanoemulsion for 1 h | Artificial DL-PDT for 1 h at 20 J/cm2 | CO2 laser AFR | 91.3% reduction in lesion count after 3 months (P < 0.0001) |

| Togsverd-Bo et al. [58] | Prospective, within-patient control | 16 patients; 10 M, 6 F | Mean age 63 years (range, 54–76 years) | ≥ 2 Grade II or III AK in each site | Scalp, chest, and extremities | MAL for 2.5 h (DL-PDT) or 3 h (red light PDT) | DL-PDT or red light at 37 J/cm2 | 2940-nm Er:YAG laser AFR |

Complete response (3 months) AFR pretreatment with DL-PDT: 74% DL-PDT alone: 46% (P = 0.026) |

| Wenande et al. [53] | RCT | 18 patients; 2:1 M:F ratio | Mean age 72.5 years (range 52–85 years) | AK and photodamaged fields | Scalp, face, and chest | Fractional 2940-nm Er: YAG laser with debulking followed by 16% MAL or MD | DL-PDT for 2 h | Fractional 2940-nm Er: YAG laser versus MD |

AK clearance rate AFL–DL-PDT: 81% MD–DL-PDT: 60% (P < 0.001) |

| Foged et al. [41] | RCT | 12 healthy volunteers; 6 M, 6 F, | Median age of 22.5 years (range 18–25 years) | Not applicable | N/A | 20% 5-ALA in cream or gel formulation for 3 h | N/A | Pretreatment with TMFI followed by 5-ALA treatment |

Skin surface PpIX: TMFI ALA cream increased over ALA cream (P < 0.001) TMFI ALA gel increased over ALA gel (P < 0.001) |

| Shavit et al. [50] | Proof of concept | Five healthy volunteers | 35–65 years | Not applicable | Forearms |

(1) 20% 5-ALA gel (2) 10% 5-ALA-microemulsion gel (3) 16.8% MAL cream (4) 20% 5-ALA solution |

N/A | Compared the effect of TMFI on 5-ALA permeation into the skin | TMFI pretreatment significantly increased the percutaneous permeation of 5-ALA and MAL |

| Thermal PDT | |||||||||

| Willey et al. [55] | Single-center study | 20 patients; 15 M, 5 F | Median age 70 years (range 57–90 years) | AKs | Distal extremities | 20% 5-ALA with 1 h heat-assisted incubation | Blue light illumination | Heated PDT versus not heated PDT |

Median percent change from baseline at 6 months Heated PDT: 88.0% (P < 0.0001) |

| Willey et al. [54] | Prospective pilot | Ten M patients | Median age, 68 years (range 58–82 years) | AKs | Face | 20% 5-ALA with 20 min heat-assisted incubation | Blue light illumination | PpIX production with heated PDT versus not heated PDT | Increased PpIX production with heated PDT than control |

| Topical combination therapy | |||||||||

| Nissen et al. [46] | RCT | 24 patients; 16 M, 8 F | Mean age 73.3 years (range 52–87 years) | Grade I–III AKs | Dorsal hands | BID 5-fluorouracil for 1 wk then 16% MAL for 30 min | DL-PDT for 2 h | Pretreatment with 5-FU |

Mean lesion response at 3 months follow-up 5-FU: 62.7% DL-PDT: 51.8% (P = 0.0011) |

| Galimberti et al. [42] | RCT | 11 patients; 10 M, 1 F | Mean age 55 years (range 40–70 years) | Grade I–III AKs | Face and scalp | QD calcipotriol 50 mcg/g 15 days prior to 16% MAL cream | DL-PDT for 2 h | Pretreatment with calcipotriol |

Complete clinical remission Calcipotriol: 85% DL-PDT: 70% |

5-ALA aminolevulinic acid, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil, AFL ablative fractional laser, AFR ablative fractional resurfacing, AK actinic keratosis, BCC basal cell carcinoma, BD Bowen’s disease, BID twice daily, CI confidence interval, char characteristics, CO2 carbon dioxide, CR complete response, cSCC cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, DL-PDT daylight-photodynamic therapy, Er: YAG erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser, F female, IPL intense pulse light, LED light-emitting diode, M male, MAL methyl aminolevulinic acid, MD microdermabrasion, N/A not available, nBCC nodular BCC, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PDL pulsed-dye laser, PDT photodynamic therapy, pop population, PpIX protoporphyrin IX, PR partial response, QD once daily, RCT randomized controlled trial, sBCC superficial BCC, SD standard deviation, TMFI thermo‐mechanical fractional injury

Table 5.

Summary of studies on innovations in PDT to improve tolerability

| References | Study type | Patient pop | Patient char | Lesions | Anatomical location | PDT treatment | Light exposure | Intervention | Key message |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation | |||||||||

| Kaw et al. [62] | Bilaterally controlled trial | 23 patients; 21 M, 2 F |

Mean age M: 69.7 years (range 58–88 years) F: 50 and 75 years |

AKs | Face and scalp | 20% 5-ALA without incubation |

Cohort 1: 30 min of blue light Cohort 2: 45 min of blue light Cohort 3: 60 min of blue light |

Simultaneous versus conventional illumination in PDT | A modified PDT regimen had similar clinical response of AK lesions as cPDT (57.7%, 59.1% on face; 43.8%, 41.9% on scalp, respectively) and was essentially painless |

| Pariser et al. [66] | RCT | 234 patients; 211 M, 23 F | Mean age 68 years (range 40–88 years) | 6–20 Grade I–II AKs | Face and scalp | 20% 5-ALA solution incubated for 1, 2, or 3 h | Blue light illumination for 16 min 40 s (10 J/cm2) | ALA-PDT versus vehicle-PDT with short incubation |

AKCR at week 12, median ± SD, P versus vehicle: Broad area, 1 h incubation: 71.4 ± 34.8% (P < 0.001) Broad area, 2 h incubation: 73.6 ± 31.1% (P < 0.001) Broad area, 3 h incubation: 78.6 ± 30.5% (P < 0.001) Spot application, 2 h incubation: 68.3 ± 39.4% (P < 0.001) Vehicle: 7.1 ± 44.3% |

| Gandy et al. [61] | Case report | 56-year-old male | Fitzpatrick skin type II | AKs | Face and scalp | 5-ALA without incubation | Two cycles of blue light; 33 min 20 s each | PDT without incubation time: Two back-to-back cycles of 16 min 40 s | Treatment was noninferior to conventional protocol and nearly painless |

| Daylight PDT | |||||||||

| Mei et al. [63] | Meta-analysis of six RCT | 369 patients; majority male | Mean age ranged from 63 to 78 years | Multiple AKs | Predominantly face and scalp; chest and extremities in one study only | N/A | N/A | Compared efficacy and safety of DL-PDT with cPDT | DL-PDT is noninferior to cPDT with red light and MAL and highly painless |

| Dirschka et al. [60] | RCT | 49 patients; 47 M, 2 F | Mean age 72.6 ± 7.1 years | Multiple AKs | Face and scalp | BF-200 ALA or 16% MAL cream for 30 min and during illumination | DL illumination for 2 h | BF-200 ALA versus 16% MAL |

Clearance rate BF-200 ALA: 79.8 ± 23.6% MAL: 76.5 ± 26.5%; Median of differences 0.0 (P < 0.0001) |

| Neittaanmäki‐Perttu et al. [64] | Prospective split-face trial | 13 patients; 7 M, 6 F | Mean age 79.8 (66–80) years | AKs | Face | BF-200 ALA or 16% MAL cream | DL illumination for 2 h | DL-PDT with MAL versus BF-200 ALA |

Complete clearance rates BF-200 ALA: 84.5% (95% CI 75.2–90.9%) MAL: 74.2% (95% CI 64.4–82.1%) |

| Paasch et al. [65] | Retrospective | 46 patients; 42 M, 4 F | Mean age 68.7 ± 9.4 years | > 5 AKs | Predominantly face; also included scalp, forehead, and dorsal hands | BF-200 ALA for 45–60 min | IDL for 35 min | AFL treatment with IDL DL-PDT | Complete clearance rate 71.7% |

| Bai-Habelski et al. [59] | Prospective | 12 patients; 11 M, 1 F | Mean age 72.7 ± 10.7 years | Mild-to-moderate AK | Face and scalp | BF-200 ALA for 30 min | 2 h illumination with the IndoorLux® System | IDL-PDT and BF-200 ALA |

Clearance rate Individual: 83.75% (66.7−100.0%) Patients: 33.3% Lesions: 84.9% |

5-ALA aminolevulinic acid, AFL ablative fractional laser, AK actinic keratosis, AKCR actinic keratosis clearance rate, char characteristics, CI confidence interval, cPDT conventional PDT, DL-PDT daylight PDT, F female, IDL indoor daylight, M male, MAL methyl aminolevulinic acid, N/A not available, PDT photodynamic therapy, pop population, RCT randomized controlled trial, SD standard deviation

Innovations to Improve Efficacy: Alternative Light Sources, Pretreatment, Thermal PDT, and Combination Therapy

Variations in ALA-PDT protocols to improve efficacy include use of alternative light sources, mechanical pretreatment or thermal conditioning during incubation to increase photosensitizer absorption, and combination therapy.

Alternative Light Sources

Optimal outcomes from PDT treatment depend upon the light source and absorption spectrum of photosensitizer used. In the past decade, both coherent (photons in phase with each other and focused) and noncoherent (photons not in phase with each other and usually diffuse) light sources have been used to improve tissue penetration and reduce the pain associated with PDT treatment.

Intense pulsed light (IPL) devices have been investigated as an alternative light source for PDT in the treatment of NMSC, including AK, superficial BCC, and SCC in situ [48, 49]. IPL uses high-intensity, non-laser light and produces broad-spectrum wavelength pulses on a broader skin area. The use of 20% 5-ALA or MAL in combination with IPL-based PDT activation resulted in upwards of 68–90% clearance within 3 months after 1–2 treatments [40, 48, 49].

Pulsed-dye lasers (PDL) have also demonstrated usefulness in the management of AKs. In a split-face prospective study, patients with multiple AKs on the scalp or forehead were pretreated with curettage and MAL with a 3-h incubation and then received either PDL illumination or conventional LED light treatment on the contralateral side. At the 12-month follow-up, efficacy of PDL-PDT was similar to conventional PDT, with a mean difference in the change from baseline in number of AKs of −0.46 (95% CI −1.28 to 0.35; P = 0.258). Notably, the pain score was lower with PDL-PDT compared with LED-PDT (visual analog score mean difference, −4.55; P < 0.01) [43].

In a prospective four-arm study, 220 patients with photodamaged skin (n = 126) or multiple AKs (n = 88) received either IPL, PDL, or IPL or PDL in combination with blue LED illumination to activate 20% 5-ALA after a 2-h incubation period. Reduction of AK lesions at the 1-month follow-up was materially superior following treatment with IPL and blue LED (84.4%) relative to other light combinations (PDL, 70.5%; PDL with blue LED, 69.3%; IPL, 70.8%) [39].

Pretreatment

Various approaches have been tested to prepare the skin to increase photosensitizer absorption. The most straightforward of these is microneedle-assisted incubation, in which the skin is perforated with a microneedling device before application of the photosensitizer. Several prospective trials utilizing split-face designs in which one side is pretreated with microneedling before photosensitizer application and PDT have yielded mixed results. In a pilot study (n = 10), there was no reported difference in AK clearance assessed 90 days after treatment between the sides pretreated with microneedling (90.5%) versus gentle curettage (86%) before MAL-PDT with red light illumination [52]. Similarly, there was no effect of microneedle pretreatment on AK complete response rate at the 4-week follow-up after PDT with 20% ALA solution preincubated for 20, 40, or 60 min on the microneedle-treated side versus 60 min on the sham-treated side before blue light illumination (71.4% versus 68.3%, 81.1% versus 79.9%, and 72.1% versus 74.2%, respectively, for microneedle-treated versus control sides; n = 15–17) [44]. However, in two additional studies without curettage on the control side (n = 16–19 per treatment arm), microneedle treatment before application of 20% ALA solution and blue light PDT resulted in significant reduction in AKs relative to the side without pretreatment (76–89.3% versus 58–69.5% after 1–4 months) [47, 51]. Given these mixed results, additional studies are needed to clarify the usefulness of microneedle pretreatment with ALA-PDT.

Ablative fractional resurfacing (AFR) using CO2 and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er: YAG) lasers is proposed to create microscopic vertical channels that facilitate deeper penetration and uptake of photosensitizing agents such as 5-ALA [45]. These ablated vertical channels are surrounded by a coagulation zone that may serve as a reservoir to allow slow release of the photosensitizer. Several clinicians have investigated pretreatment with AFR before ALA-PDT. In a prospective single-arm study (n = 29), pretreatment with CO2 laser AFR (single pass, 50 mJ pulse with spot density of 100 spots/cm2, power of 30 W, and 120-μm beam size) before ALA-PDT of AK with 20% 5-ALA solution or MAL cream resulted in complete response of 70.6% of lesions after three treatment sessions despite MAL incubation for only 70–90 min before illumination [57]. A similar study (n = 28) found a 91.3% reduction in lesion count 3 months after a single treatment with CO2 laser AFR (8 mJ pulse, 50 spots/cm2, power of 30 W, and 4–18 mm beam size depending on diameter) followed by ALA-PDT with ALA nanoemulsion and illumination with an artificial daylight lamp [56]. A prospective within-patient trial compared daylight (DL)-PDT with and without Er: YAG laser AFR pretreatment in organ transplant recipients (OTRs) with four comparable skin areas with field cancerization and ≥ 2 AKs (Grade II or III) per site [58]. Treatment areas were randomized to a single field-directed treatment with AFR-DL-PDT, DL-PDT without AFR, or conventional PDT, all with MAL cream, or AFR without ALA-PDT. The AFR was performed with a 2940-nm Er: YAG laser using two stacked pulses at 2.3 mJ per pulse, power of 1.15 W, a 50-μs pulse duration, and density of 2.4%. Three months after treatment, the median complete response rate was significantly higher at 74% for AFR-DL-PDT compared with 46% for DL-PDT without AFR (P = 0.026). A side-by-side, blinded, randomized control trial (n = 18) found the addition of AFR resulted in a significantly higher AK clearance rate at the 3-month follow-up after DL-PDT compared with microdermabrasion pretreatment and also reduced the development of new AKs [53]. A recent proof-of-concept randomized split-side study compared the efficacy and durability of response of ALA-PDT with and without CO2 laser AFR pretreatment for treatment of AK and NMSC [45]. Nineteen participants with symmetrically comparable photodamage (at least one AK/cm2) to the face, scalp, and/or distal extremities and with clinically identifiable biopsy-proven NMSC (BCC or cSCC) were enrolled. Patients received topical/regional anesthesia followed by AFR treatment to one randomly selected side with the SmartXide DOT laser for one pass of 25 W, 1200 ms duration at 500 μm spacing, and a 200 μm spot size, achieving 12% surface area ablation; hyperkeratotic areas received a second pass after saline debridement. Both sides were then treated with 20% ALA solution and incubated for 1 h, followed by blue light illumination for 16 min 40 s. At the 6-month follow-up, the pretreated sides had superior AK reduction with no AK recurrences in most participants compared with 13 cases of noted AK persistence on the contralateral conventional PDT-treated side. Notably, the results were not consistent for NMSC outcomes, with persistent NMSC in both treatment arms; however, this may have been confounded by lack of cSCC at baseline on the conventional PDT-treated sides. Lesions on the scalp and face were healed an average of 7 days post-treatment, while lesions on the forearm and hand healed within 14 days and lower extremity lesions required up to 21 days for resolution of weeping/scabbing. Despite topical/regional anesthesia, mild-to-moderate pain during treatment was reported [45].

Physical pretreatment using thermo-mechanical fractional injury (TMFI) prior to photosensitizer application has also been explored to increase uptake. TMFI creates a fractional injury using thermal energy within 5–18 ms to create micropores by vaporizing the tissue water and creates a dry zone in the dermis and epidermis, theoretically enhancing percutaneous permeation of photosensitizers [50]. Two studies conducted in healthy individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type I–III demonstrated significantly enhanced PpIX fluorescence absorption and permeation of 5-ALA treatment into TMFI pretreated tissue compared with control sites (P < 0.001) [41, 50]. TMFI treatment was well tolerated with only mild local skin reactions and low pain intensity noted. TMFI pretreatment has not yet been studied in combination with ALA-PDT for clinical management of AKs or NMSCs [41, 50].

Thermal PDT

Another potential way to increase photosensitizer absorption is to warm the skin within a physiologically tolerable range following topical drug application, particularly anatomic areas with low natural biological temperatures. In a small (n = 20) split-sided study investigating the efficacy of blue light PDT following 1-h temperature-modulated (38.8 °C versus 29.4 °C) incubation with 20% ALA on patients with multiple AKs on the distal extremities, the median clearance was significantly higher on the heat-treated versus control sides at both the 2-month (median percentage difference from baseline, 88.0% versus 70.5%) and 6-month (88.0% versus 67.5%) follow-ups (both P < 0.0001). However, adverse effects (erythema, stinging/burning, and oozing/crusting) were materially higher on the heated side when compared with the control side [55]. Another small (n = 10; 363 lesions) proof-of-concept study for facial AKs using 20% 5-ALA incubated for 20 min at a mean temperature of 41 °C (range 38–42 °C) followed by blue light illumination resulted in an average lesion clearance rate of 91.5%, with 5/10 patients achieving total clearance at the 2-month follow-up [54]. Notably, although the porphyrin intensity was significantly higher after heat treatment (P < 0.001), 8/10 patients reported no pain during incubation, two patients reported only 3/10 mild discomfort during incubation, the mean pain score during light treatment was 5 (range 3–9), and no patients reported pain at day 1 or week 1 [54].

Combination Therapy

PDT efficacy may be enhanced by combining it with topical treatments. In a randomized, controlled, split-side study in patients with multiple Grade I–III AKs on the dorsal hands, pretreatment of the skin twice daily with 5-FU for 1 week coupled with 2 h of DL-PDT resulted in significantly greater overall mean lesion response at 3 months follow-up compared with DL-PDT alone. Notably, patients did not report pain or discomfort during DL-PDT; adverse events during the 5-FU pretreatment phase consisted of erythema and were materially, but slightly, increased in the 5-FU arm 1 day post-DL-PDT [46]. Similarly, a small, split-face, randomized, controlled trial found calcipotriol pretreatment followed by application of 16% MAL cream and 2 h of DL-PDT increased complete clinical remission among patients with multiple Grade I–III AKs on the face and scalp compared with DL-PDT alone [42]. Again, erythema was subjectively noted to be more severe among patients who received calcipotriol. The authors also note patients favored conventional PDT due to increased convenience (which may have long-term implications for adherence) [42].

Innovations to Improve Tolerability and Convenience: Incubation Time, Interventions, and Daylight PDT

Improving tolerability and post-procedural downtime due to local skin reactions are desirable both to improve the patients’ experience and also to increase likelihood of adherence to repeated future treatments. Pain reduction can be achieved through invasive and noninvasive interventions including nerve blocks, intravenous analgesia, cold air analgesia, or inhalational analgesia, as reviewed in Ang et al. [67]. Topical analgesia for pain reduction (e.g., morphine gel, tetracaine gel, or lidocaine and prilocaine eutectic mixtures) has also been studied, but no significant pain reduction was observed [68–70]. Several studies have investigated the efficacy of nerve blocks to reduce pain from PDT, including a study by Klein et al. comparing nerve blocks to intravenous analgesia plus cold air analgesia, and cold air analgesia alone during scalp PDT [67, 71]. Klein et al. found that pain intervention via nerve block had the lowest pain rating score on the visual analog scale, followed by intravenous analgesia and cold air analgesia [71]. Inhalation analgesia using a 1:1 mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen was reported to significantly decrease pain compared with controls [72]. However, since there is no standard protocol for PDT, the varying designs of these studies contributed to the observed heterogeneity of the results, and further study for different pain management practices is warranted [67]. Given that interventions for analgesia may be considered insufficient or unacceptably invasive, clinicians have also explored variations in ALA-PDT protocols, including shorter incubation time and DL-PDT, to improve tolerability.

Incubation Time

While ALA-PDT–associated pain correlates with the length of incubation time on the skin, it is unclear what length of incubation optimizes photosensitizer penetration [62]. An observational kinetics study of relative changes in PpIX accumulation following application of 20% 5-ALA on multiple AKs and adjacent tissue of the face and scalp demonstrated that PpIX accumulated linearly and was statistically higher over background levels in half of lesions after 20 min and in all lesions by 2 h after application [73].

However, over the last two decades, physicians have gradually reduced the 5-ALA incubation time in clinical practice with minimal effect on therapeutic efficacy [66, 74, 75]. A randomized, vehicle-controlled study investigated broad-area application of 20% 5-ALA with various incubation times (1, 2, and 3 h) followed by blue light PDT for AKs of the face or scalp on 234 patients. Treatment with 1 h or 3 h of incubation resulted in comparable 100% lesion clearance rates (week 12, 29.8% versus 27.7%; week 24, 23.4% versus 25.5%), and both were significantly more efficacious relative to vehicle-PDT; however, patients who underwent 1-h incubation reported materially lower rates of moderate–severe stinging/burning immediately post-PDT and at the 2-week follow-up (post-PDT, 63.8% versus 78.7%; week 2, 21.3% versus 57.4%) and erythema (post-PDT, 38.3% versus 61.7%; week 2, 2.1% versus 6.4%) compared with 3-h incubation patients [66]. In a split-face trial comparing the efficacy of blue light illumination either immediately after 20% 5-ALA application or following a 1-h incubation in patients with multiple AKs on the face and scalp, clinical efficacy at the 3-month follow-up was nearly identical between the two treated sides; however, pain was markedly reduced on the side with immediate illumination [62]. Similar results were reported in a case study in which a patient was treated with 5-ALA immediately followed by blue light PDT. The treatment was painless, and the patient’s face and scalp showed near clearance of AKs at the 4-month follow-up [61]. While the mechanism behind the preservation of efficacy and mitigation of pain is unclear, it may be a result of continuous photon-driven degradation of intralesional PpIX, which prevents excessive accumulation and diffusion of PpIX into neighboring nerves [62, 76]. Notably, a randomized, vehicle-controlled trial of broad-area PDT with 20% 5-ALA with blue light illumination for the management of field cancerization in high-risk patients also demonstrated success with a short incubation time (1 h) [27].

DL-PDT

Another approach to reduce pain associated with PDT is illumination using naturally occurring ultraviolet (UV) radiation in sunlight. In a meta-analysis of six randomized, controlled trials comparing MAL with either DL-PDT (2–2.5-h sunlight exposure) or conventional red light PDT for the treatment of AKs, the pooled results showed no statistically significant difference in treatment response rates for lower-grade AKs (i.e., Grade I–II) [risk ratio (RR), 0.97; 95% CI 0.91–1.04; P = 0.41; I2 = 78%]; notably, when including studies with higher-grade (i.e., Grade III) AKs, DL-PDT had significantly less efficacy compared with conventional red light PDT (RR, 0.87; 95% CI 0.81–0.94; P < 0.001, I2 = 0). These findings were not affected by the duration of the follow-up period. Patient-reported maximal pain scores were significantly lower for DL-PDT (mean difference, −4.51; P < 0.001) compared with conventional PDT [63]. Adverse events associated with DL-PDT include mild local skin reactions such as erythema, blistering, itching, and crusting, with scarring being a rare occurrence [77]; these are common local skin reactions experienced by > 90% of patients treated with ALA-PDT [78]. These findings suggest DL-PDT may serve as a less painful alternative for lower-grade AK treatment.

Head-to-head, randomized split-side studies have found DL-PDT may also be efficacious in conjunction with multiple photosensitizers. In a randomized, split-side, noninferiority study comparing DL-PDT with either BF‐200 ALA or MAL for the treatment of Grade I–II AKs, clearance rates after 12 weeks were comparable following one treatment session (79.8 ± 23.6% and 76.5 ± 26.5%, respectively; P < 0.0001 for noninferiority) [60]. The sides treated with BF‐200 ALA gel also had lower 1‐year recurrence rates (19.9%) compared with sides treated with MAL cream (31.6%, P = 0.01) [60]. Another randomized split-face trial of 13 patients with a total of 177 Grade I–III AKs compared treatments using either BF-200 ALA or 16% MAL cream followed by DL-PDT and found both regimens effectively cleared AKs (by 85% with BF-200 ALA and 74% with MAL; P = 0.099), suggesting that DL-PDT activation is not limited to only one group of photosensitizers [64].

A potential limitation of DL-PDT is its reliance on natural sunlight, which is affected by seasonal variations, ambient temperature fluctuations, and UVB emission. A small, retrospective, proof-of-concept pilot study overcame this limitation by using 35-min exposure to an indoor DL-PDT multilight lamp device emitting 415 nm (blue), 585 nm (yellow), and 635 nm (red) wavelengths sequentially to mimic the solar radiation spectrum after CO2 AFR pretreatment and a 45–60-min incubation with BF-200 ALA [65]. An average of 3.5 months after one session, 72% of patients with field cancerization of the scalp, face, neck, and/or dorsal hand (defined as > 5 AKs) were noted to be in complete remission, but the maximal pain intensity reported was severe (mean ± SD, 9.0 ± 2.0 out of 10.0). Because less pain was reported in other studies using either BF-200 ALA [28, 60] or ablative fractional laser (AFL) [53] in conjunction with ALA, the authors attributed this finding to potential free radical byproducts from AFL-irradiated PpIX [65]. Interestingly, treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate AK on the face and scalp with BF-200 ALA photosensitizer and indoor simulated daylight resulted in an individual AK clearance rate of 67–100% and an overall lesion clearance rate of 85%, with half of participants reporting no pain at all in a small (n = 12) prospective open-label trial [59].

Organ Transplant Recipients

Patients who have received organ transplants are usually on immunosuppressive drugs and are at increased risk of developing NMSC, especially cSCC [58, 79, 80]. In OTR, cSCCs tend to be more aggressive and more highly metastatic than in the general population, highlighting the need for prevention in these patients [58].

Data suggest the efficacy of conventional PDT is lower in OTR patients, with complete response rate at 48 weeks after 20% 5-ALA solution for 5 h followed by visible light illumination of 0.55 (95% CI 0.38–0.71) versus 0.72 (95% CI 0.54–0.86) in immunocompetent controls [81]. While there is limited evidence for the treatment of NMSCs in OTR candidates [82], systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials have found that complete clearance rates are superior following MAL-PDT (40–76.4%) versus imiquimod (27.5–62.1%), diclofenac (41%), and 5-FU (11%) [82], and support use of PDT for preventing additional AKs/SCCs at least 3 months after treatment as well as achieving complete clearance of AK/SCC [80].

Advantages of PDT compared with surgery in OTRs include potential for treating larger affected areas and no documented reports of infection after PDT treatment. In recipients with lower pain thresholds, alternative modalities such as DL-PDT or AFL-assisted PDT can be employed to minimize treatment-associated pain [58]. Similar to other patients with AKs, transplant recipients with cancerized fields may benefit from AFL pretreatment followed by MAL–DL-PDT [58]. In a study comparing several modalities in 16 OTR patients with multiple AKs (10 males, mean age 63 years), the median complete response after 3 months of follow-up was 74% for AFL-assisted MAL–DL-PDT, significantly higher compared with MAL–DL-PDT without AFL (46%; P = 0.026), MAL-conventional PDT with red light LED (50%; P = 0.042), or AFL alone (5%; P = 0.004) [58].

Perhaps more so than in immunocompetent patients, early intervention to treat photodamaged skin might be considered prudent in OTR patients due to their increased risk for (aggressive) NMSC. A retrospective survey of patient-reported data from 2013 to 2018 revealed that field treatment initiation is most likely to be provided to transplant recipients with more advanced stages of cSCC (> 10 AKs or > 6 cSCCs) compared with those with AKs or early-stage cSCCs [79]. In the 57-point questionnaire collected from 295 patients (193 males, mean age 56 years), only 31 (11%) patients reported receiving field therapy, of which the majority were high-risk patients (defined as > 10 AKs and ≥ 6 cSCCs). The authors noted that this may be a missed opportunity for early intervention in a high-risk population, as early intervention with field therapy could decrease future skin cancer development [79].

Discussion and Future Directions

Additional treatment strategies are needed to address the growing incidence of NMSC. The studies described here will provide direction for future large-scale clinical trials to define the role of PDT in field cancerization, BCC, and cSCC and to further improve ALA-PDT protocols. Although PDT has been effectively used as a nonsurgical modality in patients with NMSC for decades, 10% 5-ALA gel with red light illumination is the only treatment approved in the USA for field-directed treatment of AKs, while treatment for NMSC remains off-label. Multiple interventional studies and case reports have found mounting evidence for the effectiveness of PDT to mitigate field cancerization and treat patients with superficial or nodular BCC and cSCC. Although no studies on SCC are currently recruiting, there are several ongoing clinical trials evaluating efficacy and efficiency of ALA-PDT in patients with BCC (Table 6).

Table 6.

Ongoing clinical trials

| Trial number | Intervention | Patient population | Primary outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04936932a | To examine nonablative laser treatment in sBCC | 20 adult participants (Phase N/A) | Complete clearance of BCC |

| NCT05020912a | To understand the immune response to BCC treated with PDT to develop new methods of treating BCC | 28 patients with biopsy-proven BCC (Phase 2) |

(1) Time to maximum expression of immune checkpoint molecules (2) Altered expression of immune checkpoint molecules (3) Altered recruitment of different immune cell subtypes in BCC tumor specimens |

| NCT03573401a | To compare the safety and efficacy of BF-200 ALA and PDT-lamp BF-RhodoLED® to placebo in sBCC | 186 adult patients with sBCC (Phase 3) | Composite clinical and histological response main target lesion at 12 weeks from baselinec |

| NCT04552990a | Safety assessment of injecting 5-ALA into the skin with a jet-injection device and activating the drug with light | 17 adult patients with mixed sBCC and nBCC or only nBCCs (Phase 2) | Clinical evaluation of local skin responses up to 3 months |

| NCT02367547b | To compare three photosensitizers: HAL, BF-200 ALA, and MAL | 117 adult patients with sBCC (Phase 1 and 2) | Histological lesion clearance up to 5 years |

| NCT03110159a | Comparative study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the cyclic PDT for the prevention of AK and NMSC in solid OTRs | 20 patients (OTR) (Phase 1 and 2) | Prevention of AKs and NMSC in recently transplanted OTR; time to occurrence of AKs and NMSC in OTR |

AK actinic keratosis, ALA aminolevulinic acid, BCC basal cell carcinoma, HAL hexyl aminolevulinate, MAL methyl aminolevulinic acid, N/A not available, nBCC nodular BCC, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, OTR organ transplant recipient, PDT photodynamic therapy, sBCC superficial BCC

aRecruiting

bActive not recruiting

cBaseline defined as the start of the last PDT cycle that included treatment of the main target lesion

There is also a great deal of interest to develop methods to minimize PDT-associated pain and discomfort both by using alternative light sources (such as daylight, PDL, or IPL) instead of conventional light as well as by modifying how photosensitizers are administered. Field cancerization treatments, including PDT, require frequent administration, and patients with decades of ultraviolet damage need repeated treatments to obtain complete clearance. Therefore, aspects of treatment that maximize future adherence—such as minimizing pain and other adverse events, covering larger surfaces in a single treatment, decreasing incubation times, and decreasing the frequency at which treatment is needed—may be as important as the efficacy of a single treatment. Occlusion of the treatment area during incubation might allow further reduction of incubation time, but the effects of such occlusion on both efficacy and PDT-associated pain should be explored. Research is also active in novel ways to improve photosensitizer penetration, including pretreating the lesions with AFR or TMFI, with the clinical efficacy and safety of the latter remaining to be explored. Finally, combination of PDT with other topical and physical modalities used for the treatment of AK and NMSC seems to hold potential and is an area for future research.

Although PDT is a commonly used modality, there is a striking paucity of clinical and real-world studies in the published literature. Additional research is needed to evaluate combination therapies using different light sources, photosensitizing agents, pretreatments, and different incubation times, as well as how PDT may complement prescription topical and potentially systemic regimens. Furthermore, clinical studies should include a greater diversity of patients with respect to Fitzpatrick skin types, age groups, and anatomic locations to appropriately evaluate PDT efficacy across populations. Finally, advances in our understanding of tumor biology may assist in the identification of early-stage BCC, cSCC, and even cancerized fields that may respond more robustly to PDT.

Conclusion

Various forms of PDT are being used successfully for treatment of BCC, cSCC, and field cancerization, as well as individual AKs. Clearance rates higher than 90% have been reported in patients with multiple mild-to-moderate AKs and BCC. Improvements in terms of illumination technologies and photosensitizer application and delivery have been investigated and demonstrated to have potential for success. Further studies are warranted to determine how protocols may be optimized to improve efficacy and duration of lesion clearance, as well as patient experience, thereby potentially improving long-term adherence for a chronic condition, especially among high-risk individuals.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Medical writing assistance and funding for the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by Prachi Patil, MS, and Hilary Durbano, PhD, of AlphaBioCom, LLC, and funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

Author Contributions

Aaron S. Farberg, Justin W. Marson, and Teo Soleymani were involved in the conception of the review article, provided critical intellectual feedback on content for all drafts, and approved the final version for submission.

Disclosures

Aaron S. Farberg is a consultant for Castle Biosciences Inc., and an advisory board member for Regeneron, Sanofi, UCB, BMS, Eli Lilly, Sun Pharma, Ortho Dermatologics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Incyte, Galderma, Novartis, and Pfizer, and is currently affiliated with Baylor Scott & White Health System. Justin W. Marson and Teo Soleymani have no relevant disclosures.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Josiah AJ, Twilley D, Pillai SK, Ray SS, Lall N. Pathogenesis of keratinocyte carcinomas and the therapeutic potential of medicinal plants and phytochemicals. Molecules. 2021;26(7):1979. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin LL, Lear JT. Photodynamic therapy and non-melanoma skin cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(10):98. doi: 10.3390/cancers8100098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samarasinghe V, Madan V. Nonmelanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5(1):3–10. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.94323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen DK, Lee PK. Photodynamic therapy for non-melanoma skin cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(10):90. doi: 10.3390/cancers8100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciazynska M, Kaminska-Winciorek G, Lange D, et al. Author correction: the incidence and clinical analysis of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15705. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94435-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratushny V, Gober MD, Hick R, Ridky TW, Seykora JT. From keratinocyte to cancer: the pathogenesis and modeling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(2):464–472. doi: 10.1172/JCI57415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lomas A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(5):1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muntyanu A, Ghazawi FM, Nedjar H, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer distribution in the Russian Federation. Dermatology. 2021;237(6):1007–1015. doi: 10.1159/000512454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz RA, Bridges TM, Butani AK, Ehrlich A. Actinic keratosis: an occupational and environmental disorder. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(5):606–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilaberte Y, Casanova JM, Garcia-Malinis AJ, et al. Skin cancer prevalence in outdoor workers of ski resorts. J Skin Cancer. 2020;2020:8128717. doi: 10.1155/2020/8128717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heltoft KN, Slagor RM, Agner T, Bonde JP. Metal arc welding and the risk of skin cancer. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2017;90(8):873–881. doi: 10.1007/s00420-017-1248-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madani S, Marwaha S, Dusendang JR, et al. Ten-year follow-up of persons with sun-damaged skin associated with subsequent development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(5):559–565. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalid A, van Essen P, Crittenden TA, Dean NR. The anatomical distribution of non-melanoma skin cancer: a retrospective cohort study of 22 303 Australian cases. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91(12):2750–2756. doi: 10.1111/ans.17030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6(5):963–968. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::AID-CNCR2820060515>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, Goldenberg G, Brian B. Comprehensive management of actinic keratoses: practical integration of available therapies with a review of a newer treatment approach. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7(9 Supp):S2–S12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanharanta S, Massague J. Field cancerization: something new under the sun. Cell. 2012;149(6):1179–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen SR. Recent advances in field cancerization and management of multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. F1000Res. 2018;7:690. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12837.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong T, Morton C, Collier N, et al. British Association of Dermatologists and British Photodermatology Group guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2018;180(4):730–739. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meierhofer C, Silic K, Urban MV, Tanew A, Radakovic S. The impact of occlusive vs non-occlusive application of 5-aminolevulinic acid (BF-200 ALA) on the efficacy and tolerability of photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis on the scalp and face: a prospective within-patient comparison trial. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2021;37(1):56–62. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LEVULAN KERASTICK (aminolevulinic acid HCl) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration. 2017.

- 21.AMELUZ (aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride) gel, 10% [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration. 2016.

- 22.Morton CA, Szeimies RM, Basset-Seguin N, et al. European Dermatology Forum guidelines on topical photodynamic therapy 2019 part 1: treatment delivery and established indications—actinic keratoses, Bowen's disease and basal cell carcinomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):2225–2238. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christensen E, Mjones P, Foss OA, Rordam OM, Skogvoll E. Pre-treatment evaluation of basal cell carcinoma for photodynamic therapy: comparative measurement of tumour thickness in punch biopsy and excision specimens. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91(6):651–654. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morton CA, Szeimies RM, Sidoroff A, Braathen LR. European guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy part 2: emerging indications—field cancerization, photorejuvenation and inflammatory/infective dermatoses. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(6):672–679. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vegter S, Tolley K. A network meta-analysis of the relative efficacy of treatments for actinic keratosis of the face or scalp in Europe. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6):e96829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Del Rosso JQ, Armstrong AW, Berman B, et al. Advances and considerations in the management of actinic keratosis: an expert consensus panel report. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20(8):888–893. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piacquadio D, Houlihan A, Ferdon MB, Berg JE, Marcus SL. A randomized trial of broad area ALA-PDT for field cancerization mitigation in high-risk patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(5):452–458. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinhold U, Dirschka T, Ostendorf R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase III, multicentre study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of BF-200 ALA (Ameluz((R))) vs. placebo in the field-directed treatment of mild-to-moderate actinic keratosis with photodynamic therapy (PDT) when using the BF-RhodoLED((R)) lamp. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(4):696–705. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomez C, Cobos P, Alberdi E. Methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy after partial debulking in the treatment of superficial and nodular basal cell carcinoma: 3-years follow-up. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2021;33:102176. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roozeboom MH, Arits A, Mosterd K, et al. Three-year follow-up results of photodynamic therapy vs imiquimod vs fluorouracil for treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: a single-blind, noninferiority, randomized controlled trial. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(8):1568–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filonenko E, Kaprin A, Urlova A, Grigorievykh N, Ivanova-Radkevich V. Topical 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy for basal cell carcinoma. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2020;30:101644. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.101644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wozniak Z, Trzeciakowski W, Chlebicka I, Ziolkowski P. Photodynamic diagnosis and photodynamic therapy in basal cell carcinoma using a novel laser light source. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2020;31:101883. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maytin EV, Kaw U, Ilyas M, Mack JA, Hu B. Blue light versus red light for photodynamic therapy of basal cell carcinoma in patients with Gorlin syndrome: a bilaterally controlled comparison study. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2018;22:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salvio AG, Requena MB, Stringasci MD, Bagnato VS. Photodynamic therapy as a treatment option for multiple pigmented basal cell carcinoma: long-term follow-up results. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2021;33:102154. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.102154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trafalski M, Kazubowska K, Jurczyszyn K. Treatment of the facial basal cell carcinoma with the use of photodynamic therapy: a case report. Dent Med Probl. 2019;56(1):105–110. doi: 10.17219/dmp/100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapas AM, Gilchrest BA. Broad area photodynamic therapy for treatment of multiple basal cell carcinomas in a patient with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5(2 Suppl):3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Itkin A, Gilchrest BA. Delta-aminolevulinic acid and blue light photodynamic therapy for treatment of multiple basal cell carcinomas in two patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30(7):1054–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lane JE, Allen JH, Lane TN, Lesher JL., Jr Unilateral basal cell carcinomas: an unusual entity treated with photodynamic therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;9(6):336–340. doi: 10.1177/120347540500900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abrouk M, Gianatasio C, Li Y, Waibel JS. Prospective study of intense pulsed light versus pulsed dye laser with or without blue light in the activation of PDT for the treatment of actinic keratosis and photodamage. Lasers Surg Med. 2022;54(1):66–73. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avram DK, Goldman MP. Effectiveness and safety of ALA-IPL in treating actinic keratoses and photodamage. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3(1 Suppl):S36–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foged C, Haedersdal M, Bik L, Dierickx C, Phillipsen PA, Togsverd-Bo K. Thermo-mechanical fractional injury enhances skin surface- and epidermis- protoporphyrin IX fluorescence: comparison of 5-aminolevulinic acid in cream and gel vehicles. Lasers Surg Med. 2021;53(5):622–629. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galimberti GN. Calcipotriol as pretreatment prior to daylight-mediated photodynamic therapy in patients with actinic keratosis: a case series. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2018;21:172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessels JP, Nelemans PJ, Mosterd K, Kelleners-Smeets NW, Krekels GA, Ostertag JU. Laser-mediated photodynamic therapy: an alternative treatment for actinic keratosis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96(3):351–354. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lev-Tov H, Larsen L, Zackria R, Chahal H, Eisen DB, Sivamani RK. Microneedle-assisted incubation during aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy of actinic keratoses: a randomized controlled evaluator-blind trial. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(2):543–545. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller MB, Padilla A. CO2 laser ablative fractional resurfacing photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancer: a randomized split-side study. Cutis. 2020;105(5):251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nissen CV, Heerfordt IM, Wiegell SR, Mikkelsen CS, Wulf HC. Pretreatment with 5-fluorouracil cream enhances the efficacy of daylight-mediated photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(5):617–621. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petukhova TA, Hassoun LA, Foolad N, Barath M, Sivamani RK. Effect of expedited microneedle-assisted photodynamic therapy for field treatment of actinic keratoses: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(7):637–643. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piccolo D, Kostaki D. Photodynamic therapy activated by intense pulsed light in the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Biomedicines. 2018;6(1):18. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiz-Rodriguez R, Sanz-Sanchez T, Cordoba S. Photodynamic photorejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(8):742–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shavit R, Dierickx C. A new method for percutaneous drug delivery by thermo-mechanical fractional injury. Lasers Surg Med. 2020;52(1):61–69. doi: 10.1002/lsm.23125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spencer JM, Freeman SA. Microneedling prior to Levulan PDT for the treatment of actinic keratoses: a split-face, blinded trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(9):1072–1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torezan L, Chaves Y, Niwa A, Sanches JA, Jr, Festa-Neto C, Szeimies RM. A pilot split-face study comparing conventional methyl aminolevulinate-photodynamic therapy (PDT) with microneedling-assisted PDT on actinically damaged skin. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39(8):1197–1201. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wenande E, Phothong W, Bay C, Karmisholt KE, Haedersdal M, Togsverd-Bo K. Efficacy and safety of daylight photodynamic therapy after tailored pretreatment with ablative fractional laser or microdermabrasion: a randomized, side-by-side, single-blind trial in patients with actinic keratosis and large-area field cancerization. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(4):756–764. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willey A. Thermal photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses on facial skin: a proof-of-concept study. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45(3):404–410. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40(10):1094–1102. doi: 10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Falkenberg C, Schmitz L, Dicke K, Dervenis V, Szeimies RM, Dirschka T. Pretreatment with ablative fractional carbon dioxide laser improves treatment efficacy in a synergistic PDT protocol for actinic keratoses on the head. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2021;34:102249. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jang YH, Lee DJ, Shin J, Kang HY, Lee ES, Kim YC. Photodynamic therapy with ablative carbon dioxide fractional laser in treatment of actinic keratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(4):417–422. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Togsverd-Bo K, Lei U, Erlendsson AM, et al. Combination of ablative fractional laser and daylight-mediated photodynamic therapy for actinic keratosis in organ transplant recipients—a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(2):467–474. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bai-Habelski JC, Medrano K, Palacio A, Reinhold U. No room for pain: a prospective study showing effective and nearly pain-free treatment of actinic keratosis with simulated daylight photodynamic therapy (SDL-PDT) using the IndoorLux(R) System in combination with BF-200 ALA (Ameluz(R)) Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2021;37:102692. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2021.102692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dirschka T, Ekanayake-Bohlig S, Dominicus R, et al. A randomized, intraindividual, non-inferiority, phase III study comparing daylight photodynamic therapy with BF-200 ALA gel and MAL cream for the treatment of actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(2):288–297. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gandy J, Labadie B, Bierman D, Zachary C. Photodynamic therapy effectively treats actinic keratoses without pre-illumination incubation time. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(3):275–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaw U, Ilyas M, Bullock T, et al. A regimen to minimize pain during blue light photodynamic therapy of actinic keratoses: bilaterally controlled, randomized trial of simultaneous versus conventional illumination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(4):862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mei X, Wang L, Zhang R, Zhong S. Daylight versus conventional photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2019;25:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neittaanmaki-Perttu N, Karppinen TT, Gronroos M, Tani TT, Snellman E. Daylight photodynamic therapy for actinic keratoses: a randomized double-blinded nonsponsored prospective study comparing 5-aminolaevulinic acid nanoemulsion (BF-200) with methyl-5-aminolaevulinate. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(5):1172–1180. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Paasch U, Said T. Treating field cancerization by ablative fractional laser and indoor daylight: assessment of efficacy and tolerability. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19(4):425–427. doi: 10.36849/JDD.2020.4589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]